PREAMBLE

The American College of Cardiology (ACC) and the American Heart Association (AHA) performance measurement sets serve as vehicles to accelerate translation of scientific evidence into clinical practice. Measure sets developed by the ACC and AHA are intended to provide practitioners and institutions that deliver cardiovascular services with tools to measure the quality of care provided and identify opportunities for improvement.

Writing committees are instructed to consider the methodology of performance measure development (1,2) and to ensure that the measures developed are aligned with ACC/AHA clinical guidelines. The writing committees also are charged with constructing measures that maximally capture important aspects of quality of care, including timeliness, safety, effectiveness, efficiency, equity, and patient-centeredness, while minimizing, when possible, the reporting burden imposed on hospitals, practices, and practitioners.

Potential challenges from measure implementation may lead to unintended consequences. The manner in which challenges are addressed is dependent on several factors, including the measure design, data collection method, performance attribution, baseline performance rates, reporting methods, and incentives linked to these reports.

The ACC/AHA Task Force on Performance Measures (Task Force) distinguishes quality measures from performance measures. Quality measures are those metrics that may be useful for local quality improvement but are not yet appropriate for public reporting or pay-for-performance programs (uses of performance measures). New measures are initially evaluated for potential inclusion as performance measures. In some cases, a measure is insufficiently supported by the guidelines. In other instances, when the guidelines support a measure, the writing committee may feel it is necessary to have the measure tested to identify the consequences of measure implementation. Quality measures may then be promoted to the status of performance measures as supporting evidence becomes available.

Gregg C. Fonarow, MD, FACC, FAHA

Chair, ACC/AHA Task Force on Performance Measures

1. INTRODUCTION

In 2018, the Task Force convened the writing committee to begin the process of revising the existing performance measures set for hypertension that had been released in 2011 (3). The writing committee also was charged with the task of developing new measures to evaluate the care of patients in accordance with the 2017 Hypertension Clinical Practice Guidelines (4).

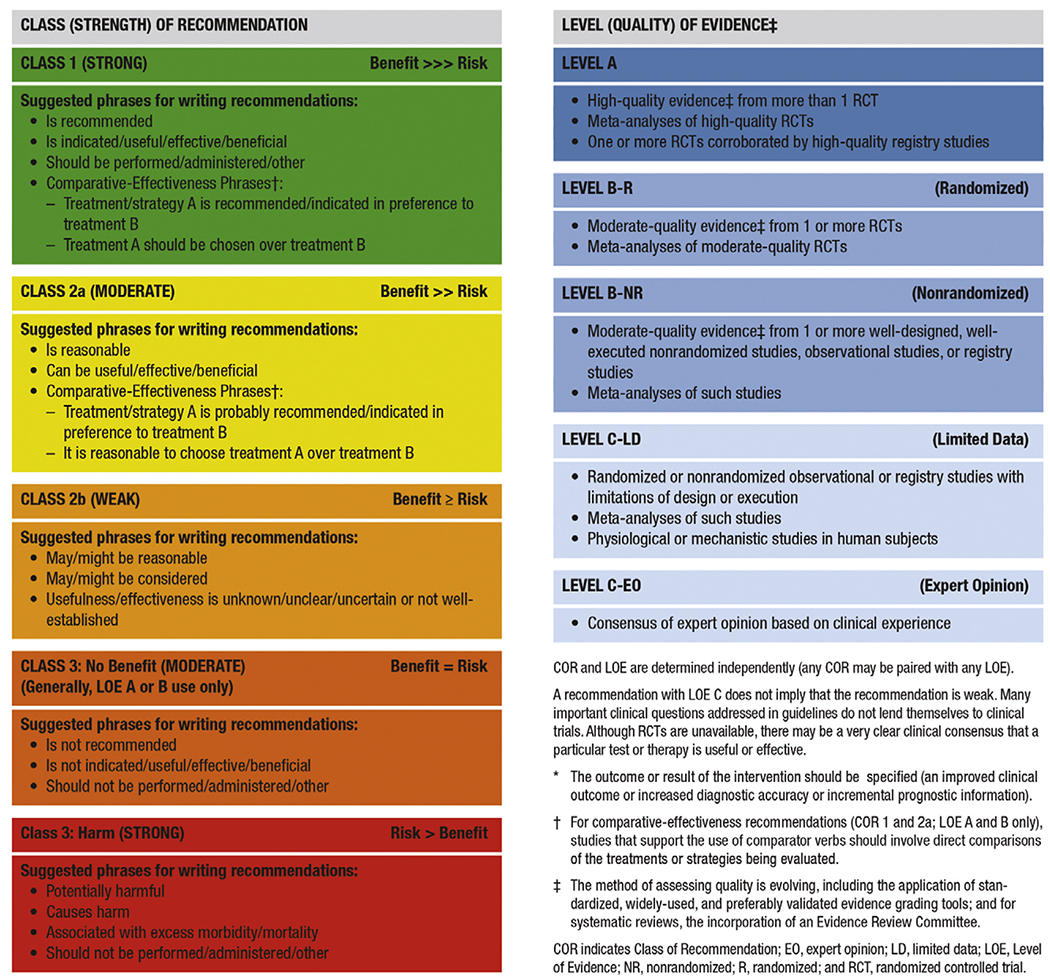

The writing committee developed a comprehensive measure set for the diagnosis and treatment of high blood pressure (HBP) that includes 22 new measures: 6 performance measures, 6 process quality measures, and 10 structural quality measures. In conceptualizing these measures, the writing committee paid very close attention to the current Class of Recommendation (COR) and Level of Evidence (LOE) guideline classification scheme used by ACC and AHA in all of its guidelines, as shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Applying Class of Recommendation and Level of Evidence to Clinical Strategies, Interventions, Treatments, or Diagnostic Testing in Patient Care (Updated August 2015)*

|

Generally, performance measures are developed from Class 1 CORs and Level A and B LOEs (i.e., strong recommendations based on the highest quality of evidence), but quality measures are generally based on lower ranges of CORs and LOEs. This distinction is important to remember throughout the present document, given that performance measures are most commonly designed to be considered for use in national quality payment and reporting programs by entities such as the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA), whereas quality measures are typically designed to support quality improvement initiatives and activities at the national or microsystem levels.

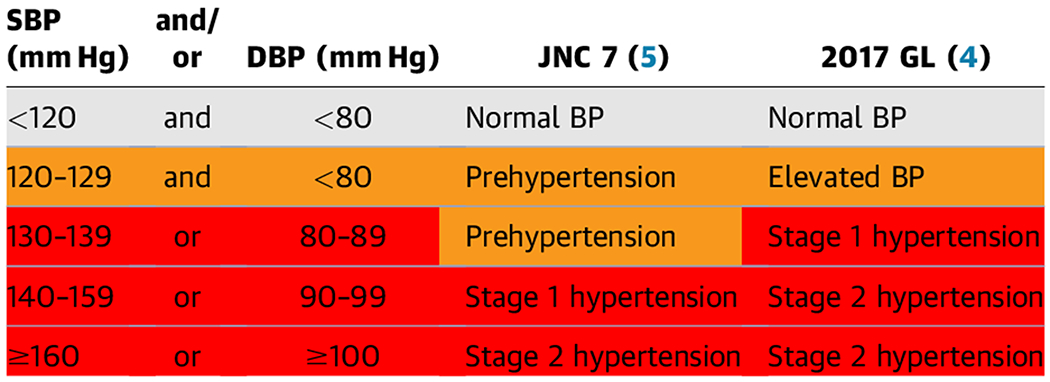

The effective implementation of this measure set by clinicians, care teams, and health systems will lead to significant improvements in effective detection and treatment of HBP for millions of people across the United States. Specifications for these new measures take into full account the revised classification taxonomy of HBP from the 2017 Hypertension Clinical Practice Guidelines (4), as noted in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

BP Classification (JNC 7 and the 2017 Hypertension Clinical Practice Guidelines)

|

BP should be based on an average of ≥2 careful readings on ≥2 occasions. Adults with SBP or DBP in 2 categories should be designated to the higher BP category.

BP indicates blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; GL, guideline; JNC, Joint National Committee; and SBP, systolic blood pressure.

The writing committee felt that it was critically important to incorporate this revised classification into the construction of each of the new performance and quality measures presented in this document. The writing committee believed that the former HBP classification scheme previously published by the Joint National Committee (5) was now out of date and needed replacement with that of the 2017 Hypertension Clinical Practice Guidelines (4), described in Table 2, to reduce confusion in the field. The current International Classification of Diseases, 10th edition, codes have not yet been modified to reflect the new classification from the 2017 Hypertension Clinical Practice Guidelines (4), which may create some initial challenges with implementation. The writing committee is sensitive to the fact that the current version (2019 at the time of this writing) of the performance measures for controlling HBP developed by the NCQA for the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (6) and currently in use in 2019 by CMS (7) also does not incorporate the 2017 Hypertension Clinical Practice Guidelines classification scheme. It is well understood that these measures are already in widespread use, especially for quality-related payment programs promulgated by CMS, such as the Medicare Advantage “Stars” ratings, the Medicare Shared Savings Program, and the Physician Quality Payment Program, as well as many other programs promoted by commercial health insurers. In particular, the widespread use of the 2017 Hypertension Clinical Practice Guidelines (4) classification scheme will also help to guide decision-making about when to prescribe antihypertensive medications in accordance with its current recommendations for the ACC/AHA stages of HBP (i.e., stage 2, stage 1, and elevated blood pressure [BP]), as outlined in Table 3.

TABLE 3.

Guideline Recommendation for BP-Lowering Medications: ACC/AHA COR/LOE

| ASCVD Risk | Stage 2 High BP (≥140 mm Hg) | Stage 1 High BP (139-130 mm Hg) | Elevated BP (129-120 mm Hg) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ASCVD Risk ≥10% | COR: 1, LOE: A | COR: 1, LOE: A | Not recommended |

| ASCVD Risk <10% | COR: 1, LOE: C-LD | Not recommended | Not recommended |

All require intensive lifestyle modification (COR: 1, LOE: A) (applies to the entire table). For older adults (≥65 years of age) with hypertension and a high burden of comorbidity and limited life expectancy, clinical judgment, patient preference, and a team-based approach to assess risk/benefit are reasonable for decisions about intensity of BP lowering and choice of antihypertensive drugs (COR: 2a, LOE: C-EO).

ACC indicates American College of Cardiology; AHA, American Heart Association; ASCVD, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; BP, blood pressure; COR, Class of Recommendation; and LOE, Level of Evidence.

In the 2017 Hypertension Clinical Practice Guidelines (4), the authors emphasized the critical importance of measuring atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk for all patients with HBP, regardless of stage. Therefore, it will be important for the end users of the new ACC/AHA performance measure set to incorporate this risk assessment process in order to achieve successful implementation as a key component of quality improvement for patients with HBP.

Because the current NCQA and CMS performance measures for controlling HBP assess only the population with ACC/AHA stage 2 HBP (6), the writing committee also felt that it was important to emphasize the 2017 Hypertension Clinical Practice Guidelines (4) recommendations to lower BP below the 130/80-mm Hg threshold for both ACC/AHA stage 2 and stage 1 patients. In formulating these new performance measures, the writing committee was sensitive to the fact that there is currently not complete consensus among other guidelines from the American College of Physicians (ACP) and the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) (8) and also the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) (9). Nonetheless, despite this ongoing debate, the writing committee felt strongly that it is now time to move the US healthcare system ahead to reflect these differing points of view and expects that widespread use of this new measure set will help to achieve this goal.

In addition, the writing committee was concerned that NCQA and CMS would be less likely to consider testing and adopting performance measures with denominator specifications different from those of the “Controlling High Blood Pressure” measure currently in widespread use (and recently revised in 2019) (10). Therefore, the writing committee chose to promote flexible denominator congruity and harmonization (as defined by the National Quality Forum [NQF]) with both NCQA and CMS measure specifications in the new ACC/AHA performance measure set to promote its initial widespread use by clinicians and entities who support the treatment recommendations for ACC/AHA stage 1 HBP as emphasized in the 2017 Hypertension Clinical Practice Guidelines (4). This new performance measure set also includes a new composite measure for control of HBP for both ACC/AHA stage 2 and ACC/AHA stage 1 to a systolic goal of <130 mm Hg. Furthermore, the new Process Quality Measures are intended for use in quality improvement initiatives that are designed to take into account management and control for all ACC/AHA stages of HBP without creating controversy or conflict with CMS, NCQA, NQF, and professional societies with differing recommendations and points of view about treatment of ACC/AHA stage 2 and stage 1 HBP. CMS recently determined that the evidence is sufficient to cover ambulatory BP monitoring for the diagnosis of hypertension in Medicare beneficiaries with suspected white coat or masked hypertension (11,12). Annals of Internal Medicine also published an “In the Clinic” section for screening, prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of hypertension, citing the 2017 Hypertension Clinical Practice Guidelines (13).

The writing committee was also interested in translating some of the 2017 Hypertension Clinical Practice Guidelines recommendations for systematic strategies that support the consistent and accurate diagnosis and treatment of populations of patients with HBP (4). In its deliberations on this challenge, the writing committee felt that it would be cumbersome and challenging to collect data at the patient and individual clinician levels, thereby limiting the use and utility of measures specified at these levels. With these potential constraints in mind, the writing committee created 10 new structural quality measures designed to evaluate the capability and capacity of various levels of the US healthcare system to implement 2017 Hypertension Clinical Practice Guidelines recommended strategies, such as standardized BP measurement protocols, electronic health record surveillance, telehealth, team-based care, a single plan of care, and performance measurement (4). These new measures are intended for qualitative evaluation of process and infrastructure for these strategies at the care delivery unit (CDU) level (including solo/small physician offices, group practices, health systems, public health sites, accountable care organizations, and clinically integrated networks).

Summaries for these measures are displayed in Tables 4 and 5, which provide information on each measure. Tables 4 and 5 also list each of the new measures and which ACC/AHA classes of HBP are addressed for each. More detailed descriptive and technical specifications for each measure are listed in Appendix A, which provides additional details for each measure description, numerator, denominator (including denominator exclusions and exceptions), rationale for the measure, guideline recommendations that support the measure, measurement period, source of data, and attribution.

TABLE 4.

Summary of 2019 ACC/AHA Performance and Quality Measures for the Diagnosis and Management of HBP

| Measure No. | Measure Title/Description | ACC/AHA Stage 2 HBP | ACC/AHA Stage 1 HBP | ACC/AHA Elevated BP | COR/LOE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Performance Measures* | |||||

| PM-1a | ACC/AHA stage 2 HBP control SBP <140 mm Hg | + | − | − | COR: 1, LOE: A |

| PM-1b | ACC/AHA stage 2 HBP control SBP <130 mm Hg | + | − | − | COR: 1, LOE: A / COR: 2a, LOE: C-EO |

| PM-2 | ACC/AHA stage 1 HBP control SBP <130 mm Hg | − | + | − | COR: 1, LOE: A |

| PM-3 | ACC/AHA stage 2 and stage 1 HBP control SBP <130 mm Hg (composite measure combining PM-1b and PM-2) | + | + | − | COR: 1, LOE: A / COR: 2a, LOE: C-EO |

| PM-4 | Nonpharmacological interventions for ACC/AHA stage 2 HBP | + | − | − | COR: 1, LOE: A |

| PM-5 | Use of HBPM for management of ACC/AHA stage 2 HBP | + | − | − | COR: 1, LOE: A |

| Process Quality Measures* | |||||

| QM-1 | Nonpharmacological interventions for ACC/AHA stage elevated BP | − | − | + | COR: 1, LOE: A |

| QM-2 | Nonpharmacological interventions for ACC/AHA stage 1 HBP | − | + | − | COR: 1, LOE: A |

| QM-3 | Nonpharmacological interventions for all ACC/AHA stages of HBP (composite measure combining PM-4, QM-1, and QM-2) | + | + | + | COR: 1, LOE: A |

| QM-4 | Medication adherence to drug therapy for ACC/AHA stage 1 with ASCVD risk ≥10% or ACC/AHA stage 2 HBP | + | + | − | COR: 1, LOE: A |

| QM-5 | Use of HBPM for management of ACC/AHA stage 1 HBP | − | + | − | COR: 1, LOE: A |

| QM-6 | Use of HBPM for management of ACC/AHA stage 1 or ACC/AHA stage 2 (composite measure combining PM-5 and QM-5) | + | + | − | COR: 1, LOE: A |

Performance measures are used in national quality payment and reporting programs, whereas process quality measures support quality improvement initiatives and activities at the national or microsystem levels.

+Indicates the corresponding ACC/AHA stage for the measure. −Indicates that the ACC/AHA stage does not correspond to the measure.

ACC indicates American College of Cardiology; AHA, American Heart Association; ASCVD, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; BP, blood pressure; COR, Class of Recommendation; HBP, high blood pressure; HBPM, home blood pressure monitoring; LOE, Level of Evidence; PM, performance measure; QM, quality measure; and SBP, systolic blood pressure.

TABLE 5.

Summary of 2019 ACC/AHA Structural Measures for the Diagnosis and Management of HBP

| Measure No. | Measure Title/Description | ACC/AHA Stage 2 HBP | ACC/AHA Stage 1 HBP | ACC/AHA Elevated BP | COR/LOE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis, Assessment, and Accurate Measurement | |||||

| SM-1 | Use of a standard protocol to consistently and correctly measure BP in the ambulatory setting | + | + | + | COR: 1, LOE: C-EO |

| SM-2 | Use of a standard process for assessing ASCVD risk (2019 Prevention Guideline [14]) | + | + | + | COR: 1, LOE: B-NR |

| SM-3 | Use of a standard process for properly screening all adults ≥18 years of age for HBP (USPSTF [15]) | + | + | + | Grade A (USPSTF) |

| SM-4 | Use of an EHR to accurately diagnose and assess HBP control | + | + | + | COR: 1, LOE: B-NR |

| Patient-Centered Approach for Controlling HBP | |||||

| SM-5 | Use of a standard process to engage patients in shared decision-making, tailored to their personal benefits, goals, and values for evidence-based interventions to improve control of HBP (2019 Prevention Guideline [14]) | + | + | + | COR: 1, LOE: B-R |

| SM-6 | Demonstration of infrastructure and personnel that assess and address social determinants of health of patients with HBP (2019 Prevention Guideline [14]) | + | + | + | COR: 1, LOE: B-NR |

| Implementation of a System of Care for Patients With HBP | |||||

| SM-7 | Use of team-based care to better manage HBP | + | + | + | COR: 1, LOE: A |

| SM-8 | Use of telehealth, m-health, e-health, and other digital technologies to better diagnose and manage HBP | + | + | + | COR: 2a, LOE: A / COR: 1, LOE: A |

| SM-9 | Use of a single, standardized plan of care for all patients with HBP | + | + | + | COR: 1, LOE: C-EO |

| Use of Performance Measures to Improve Care for HBP | |||||

| SM-10 | Use of performance and quality measures to improve quality of care for patients with HBP | + | + | − | COR: 2a, LOE: B-NR |

+Indicates the corresponding ACC/AHA stage for the measure. −Indicates that the ACC/AHA stage does not correspond to the measure.

ACC indicates American College of Cardiology; AHA, American Heart Association; ASCVD, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; BP, blood pressure; COR, Class of Recommendation; e-health, healthcare services provided electronically via the Internet; EHR, electronic health record; HBP, high blood pressure; LOE, Level of Evidence; m-health, practice of medicine and public health supported by mobile devices; SM, structural measure; and USPSTF, US Preventive Services Task Force.

1.1. Scope of the Problem

Failing to correctly diagnose and control HBP can put people at increased risk for cardiovascular disease, stroke, and renal failure. Recent analyses suggest that >100 million Americans currently have HBP, and the 2011-2014 US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey estimated that 46% of US adults have HBP (16). An additional 12% of US adults have elevated BP and are at high risk of developing HBP. Among US adults taking antihypertensive medication, 53% have uncontrolled BP (16). Of US adults with hypertension, 20% were unaware they had the condition (17). In a large cohort study of US adults ≥45 years of age, the incidences of ASCVD and all-cause death were 20.5 and 29.6 per 1,000 person-years, respectively, among participants with ACC/AHA stage 1 HBP who had been recommended to initiate antihypertensive medication, and 22.7 and 32.9 per 1,000 person-years, respectively, among participants with ACC/AHA stage 2 HBP. Among participants taking antihypertensive medication with above-goal BP (i.e., systolic BP ≥130 mm Hg or diastolic BP ≥80 mm Hg), the incidences of ASCVD and all-cause death were 33.6 and 42.5 events per 1000 person-years, respectively (18). In addition, individuals with HBP face on average nearly $2000 more in annual healthcare expenses than those without HBP (19).

Two studies have projected large reductions in ASCVD and all-cause death among US adults through the achievement of the BP goals in the 2017 Hypertension Clinical Practice Guidelines (20,21). In 1 study, it was estimated that 3 million ASCVD events could be averted over the next 10 years through achievement and maintenance of the 2017 ACC/AHA BP goals (systolic/diastolic BP <130/80 mm Hg; <130 mm Hg for adults ≥65 years of age with low ASCVD risk), as compared with maintaining current BP and treatment and control levels (20). Overall, 33% of all ASCVD events prevented would be in those initiating antihypertensive treatment, and 67% would be in those intensifying current antihypertensive treatment (20).

Despite the evidence-based recommendations for lower BP goals (<130/80 mm Hg) in the 2017 Hypertension Clinical Practice Guidelines (4), existing quality measures from the NCQA for controlling HBP (for hypertensive adults 18-59 years of age whose BP was <140/90 mm Hg) (6) have not changed substantially over the past several years for various insured populations, including commercial, Medicaid, Medicare Fee for Service, and Medicare Advantage (10). Re-examining both the targets and processes of managing HBP are thus warranted to help support the use of the latest evidence in optimizing the quality of care and outcomes for patients with HBP.

1.2. Disclosure of Relationships With Industry and Other Entities

The Task Force makes every effort to avoid actual, potential, or perceived conflicts of interest that could arise as a result of relationships with industry or other entities (RWI). Detailed information on the ACC/AHA policy on RWI can be found online. All members of the writing committee, as well as those selected to serve as peer reviewers of this document, were required to disclose all current relationships and those existing within the 12 months before the initiation of this writing effort. ACC/AHA policy also requires that the writing committee chair and at least 50% of the writing committee have no relevant RWI.

Any writing committee member who develops new RWI during his or her tenure on the writing committee is required to notify staff in writing. These statements are reviewed periodically by the Task Force and by members of the writing committee. Author and peer reviewer RWI that are pertinent to the document are included in the appendixes: Appendix B for relevant writing committee RWI and Appendix C for comprehensive peer reviewer RWI. Additionally, to ensure complete transparency, the writing committee members’ comprehensive disclosure information, including RWI not relevant to the present document, is available online. Disclosure information for the Task Force is also available online.

The work of the writing committee was supported exclusively by the ACC and the AHA without commercial support. Members of the writing committee volunteered their time for this effort. Meetings of the writing committee were confidential and attended only by writing committee members, staff from the ACC and AHA, and representatives of the American Medical Association (AMA) and Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association (PCNA), which served as collaborators on this project.

1.3. Abbreviations and Acronyms

| Abbreviation/Acronym | Meaning/Phrase |

|---|---|

| ASCVD | atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease |

| BP | blood pressure |

| CDU | care delivery unit |

| CMS | Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services |

| COR | Class of Recommendation |

| HBP | high blood pressure |

| LOE | Level of Evidence |

| NCQA | National Committee for Quality Assurance |

| NQF | National Quality Forum |

2. METHODOLOGY

2.1. Literature Review

In developing the updated HBP measure set, the writing committee reviewed evidence-based guidelines and statements that would potentially impact the construction of the measures. The clinical practice guidelines and scientific statements that most directly contributed to the development of these measures are shown in Table 6.

TABLE 6.

Associated Clinical Practice Guidelines and Other Clinical Guidance Documents

| Clinical Practice Guidelines | |

| 1 | 2017 Hypertension Clinical Practice Guidelines (4) |

| 2 | 2019 Cardiovascular Disease Prevention Guideline (14) |

| 3 | 2017 USPSTF High Blood Pressure Guideline (15) |

| Performance Measures and Scientific Statements | |

| 1 | 2011 Hypertension Performance Measures (3) |

| 2 | NQF Measure 0018 Controlling High Blood Pressure (NCQA) (22) |

| 3 | ACC/AHA Performance Measures Methodology (1) |

ACC indicates American College of Cardiology; AHA, American Heart Association; NCQA, National Committee for Quality Assurance; NQF, National Quality Forum; and USPSTF, US Preventive Services Task Force.

2.2. Definition and Selection of Measures

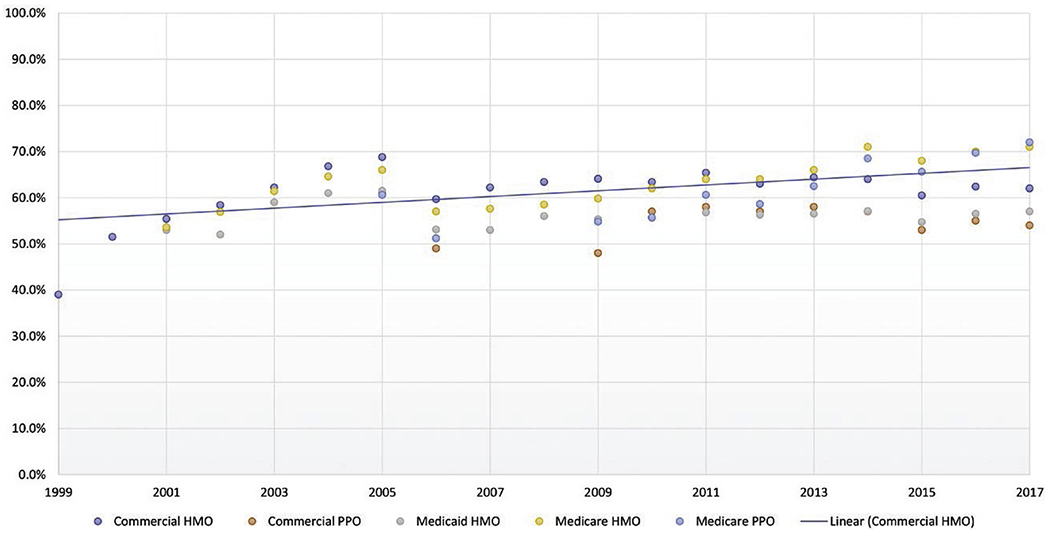

In constructing the measure set, the writing committee recognized that other organizations (e.g., CMS, NCQA) have developed or are continuing to develop HBP performance measures in response to the release of the 2017 Hypertension Clinical Practice Guidelines (4). Hence, the committee created performance measures for ACC/AHA stage 2 HBP that are aligned with these other groups, called harmonizing measures. In addition, the committee created enhancing measures that incorporate emerging evidence showing improved outcomes with more aggressive BP control (i.e., for ACC/AHA stage 1 HBP). When defining harmonization, the writing committee followed the NQF Guidance for Measure Harmonization report, which states “measure harmonization should be considered when measures are intended to address either the same measure focus—the target process, condition, event, outcome (e.g., numerator)—or the same target population (e.g., denominator).” (23); The enhancing performance and quality measures are intended to promote the widespread application in clinical practice of the current recommendations from the 2017 Hypertension Clinical Practice Guidelines (4) to improve care and outcomes for all patients with HBP, including those with ACC/AHA stage 1 HBP and elevated BP. The writing committee acknowledges that adding new performance measures may not be initially feasible in the current regulatory environment, in which many healthcare entities already have a high burden to collect and report existing quality measures. Nonetheless, it is imperative that national quality improvement efforts urgently incorporate high-quality, evidence-based recommendations into practice, especially given the recent lack of significant progress in controlling HBP with national measures in current use by CMS, NCQA, state Medicaid agencies, NQF, and other entities (Figure 1) (6).

FIGURE 1. Performance of HEDIS Controlling HBP Measure 1999-2017 (Percent of Patients With Hypertension Treated in Accordance With the HEDIS Controlling HBP Measure).

The HEDIS Hypertension Measure (6) assesses adults 18-85 years of age who had a diagnosis of hypertension and whose blood pressure was adequately controlled according to the following criteria: 1) Adults 18-59 years of age whose blood pressure was <140/90 mm Hg. 2) Adults 60-85 years of age, with a diagnosis of diabetes mellitus, whose blood pressure was <140/90 mm Hg. 3) Adults 60-85 years of age, without a diagnosis of diabetes mellitus, whose blood pressure was <150/90 mm Hg (likely to be lowered in 2018 to <140/90 mm Hg). Data in graph from National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) (6). HBP indicates high blood pressure; HEDIS, Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set; HMO, health maintenance organization; and PPO, preferred provider organization.

The writing committee reviewed clinical practice guidelines and other clinical guidance documents recently published by other entities, in addition to ACC/AHA documents. The writing committee also examined available information on gaps in care to address which new measures might be appropriate as performance measures or quality measures for this measure set update, based on the attributes for performance measures outlined in Table 7.

TABLE 7.

ACC/AHA Task Force on Performance Measures: Attributes for Performance Measures (24)

| 1. Evidence Based | |

| High-impact area that is useful in improving patient outcomes | a. For structural measures, the structure should be closely linked to a meaningful process of care that in turn is linked to a meaningful patient outcome. b. For process measures, the scientific basis for the measure should be well established, and the process should be closely linked to a meaningful patient outcome. c. For outcome measures, the outcome should be clinically meaningful. If appropriate, performance measures based on outcomes should adjust for relevant clinical characteristics through the use of appropriate methodology and high-quality data sources. |

| 2. Measure Selection | |

| Measure definition | a. The patient group to whom the measure applies (denominator) and the patient group for whom conformance is achieved (numerator) are clearly defined and clinically meaningful. |

| Measure exceptions and exclusions | b. Exceptions and exclusions are supported by evidence. |

| Reliability | c. The measure is reproducible across organizations and delivery settings. |

| Face validity | d. The measure appears to assess what it is intended to. |

| Content validity | e. The measure captures most meaningful aspects of care. |

| Construct validity | f. The measure correlates well with other measures of the same aspect of care. |

| 3. Measure Feasibility | |

| Reasonable effort and cost | a. The data required for the measure can be obtained with reasonable effort and cost. |

| Reasonable time period | b. The data required for the measure can be obtained within the period allowed for data collection. |

| 4. Accountability | |

| Actionable | a. Those held accountable can affect the care process or outcome. |

| Unintended consequences avoided | b. The likelihood of negative unintended consequences with the measure is low. |

Reproduced with permission from Thomas et al. (25) Copyright © 2018, American Heart Association, Inc., and American College of Cardiology Foundation. ACC indicates American College of Cardiology; and AHA, American Heart Association.

3. AHA/ACC HBP MEASURE SET PERFORMANCE MEASURES

3.1. Discussion of Changes to 2011 Hypertension Measure Set

After reviewing the existing guidelines and the 2011 hypertension measure set (3), the writing committee discussed which measures required revision to reflect updated science related to HBP and identified which guideline recommendations could serve as the basis for new performance or quality measures. The writing committee also reviewed existing publicly available measure sets.

These subsections serve as a synopsis of the revisions that were made to previous measures and a description of why the new measures were created for both the inpatient and outpatient settings.

3.1.1. Retired Measures

The writing committee decided to retire the BP Control Measure because it was not concordant with the 2017 Hypertension Clinical Practice Guidelines (4).

3.1.2. New Measures

On the basis of the 2017 Hypertension Clinical Practice Guidelines (4) and the 2019 Prevention Guideline (14), the writing committee created a comprehensive list of measures intended to be used to improve important gaps in the quality of care for patients with HBP (4,14). This set includes 22 new measures: 6 performance measures, 6 process quality measures, and 10 structural quality measures. Table 8 includes a list of the measures with information on the attribution and a brief rationale. Performance measures are typically outcome measures that target meaningful gaps in the quality of care, are based on Class 1 clinical practice guideline recommendations, and are appropriately designed for use in accountability in programs that rely on public reporting and pay-for-value initiatives promoted by organizations such as CMS, commercial payers, the NCQA, and the NQF. The writing committee believes that it is important to confirm its full support of the performance measure for BP control in current widespread use by CMS and NCQA for HBP (i.e., the proportion of stage 2 patients with HBP with control below the Joint National Committee (5) traditional target of 140/90 mm Hg). In addition, the writing committee unanimously feels it important to include new harmonizing measures for stage 1 HBP and a composite measure (i.e., for ACC/AHA stage 2 and ACC/AHA stage 1 combined) that emphasize the importance of controlling HBP below the new ACC/AHA target of 130/80 mm Hg, as recommended by the 2017 Hypertension Clinical Practice Guidelines (4). Because of the importance of the promotion of intensive nonpharmacological “healthy lifestyle” modifications and home BP monitoring for patients with stage 2 HBP (as emphasized in the 2017 Hypertension Clinical Practice Guidelines (4), new performance measures to assess quality of care in this regard have been included. These new performance measures are also intended to harmonize with the performance measure for stage 2 HBP currently in use by CMS and NCQA.

TABLE 8.

New Performance, Quality, and Structural Measures for the Diagnosis and Management of HBP in the Outpatient Care Setting*

| Measure No. | Measure Title | Attribution | Rationale for Creating New Measure |

|---|---|---|---|

| PM-1a | ACC/AHA stage 2 HBP control. SBP <140 mm Hg (harmonizing measure) | Healthcare provider (healthcare provider, physician group practice, accountable care organization, clinically integrated network, health plan, integrated delivery system) | Harmonizes with current performance measure “Controlling High Blood Pressure” for ACC/AHA stage 2 HBP currently in widespread use. |

| PM-1b | ACC/AHA stage 2 HBP control SBP <130 mm Hg (enhancing measure) | Healthcare provider (healthcare provider, physician group practice, accountable care organization, clinically integrated network, health plan, integrated delivery system) | Harmonizes with current performance measure “Controlling High Blood Pressure” for ACC/AHA stage 2 HBP currently in widespread use and adds lower target for further risk reduction. |

| PM-2 | ACC/AHA stage 1 HBP control SBP <130 mm Hg (harmonizing measure) | Healthcare provider (healthcare provider, physician group practice, accountable care organization, clinically integrated network, health plan, integrated delivery system) | Harmonizes with current performance measure “Controlling High Blood Pressure” for ACC/AHA stage 2 HBP currently in widespread use. Adds emphasis on including the ACC/AHA stage 1 HBP population. |

| PM-3 | ACC/AHA stage 2 and stage 1 HBP control SBP <130 mm Hg (composite measure combining PM-1b and PM-2) | Healthcare provider (healthcare provider, physician group practice, accountable care organization, clinically integrated network, health plan, integrated delivery system) | Harmonizes with current performance measure “Controlling High Blood Pressure” for ACC/AHA stage 2 HBP currently in widespread use. Adds emphasis on including the ACC/AHA stage 1 HBP population and combines both ACC/AHA stage 2 and stage 1 HBP populations. |

| PM-4 | Nonpharmacological interventions for ACC/AHA stage 2 HBP | Physician group practice, accountable care organization, clinically integrated network, health plan, integrated delivery system | Harmonizes with current performance measure “Controlling High Blood Pressure” for ACC/AHA stage 2 HBP currently in widespread use. Adds new emphasis on high-quality evidence and strong recommendation for promoting lifestyle modification, as recommended in the 2017 Hypertension Clinical Practice Guidelines for this population as an important strategy for controlling HBP. |

| PM-5 | Use of HBPM for management of ACC/AHA stage 2 HBP | Healthcare provider (healthcare provider, physician group practice, accountable care organization, clinically integrated network, health plan, integrated delivery system) | Harmonizes with current performance measure “Controlling High Blood Pressure” for ACC/AHA stage 2 HBP currently in widespread use. Adds new emphasis on correct measurement of BP by individuals at home or elsewhere outside the clinic setting, as recommended in the 2017 Hypertension Clinical Practice Guidelines for this population as an important strategy for evaluating control of HBP. |

| QM-1 | Nonpharmacological interventions for ACC/AHA stage elevated BP | Physician group practice, accountable care organization, clinically integrated network, health plan, integrated delivery system | Adds new emphasis on high-quality evidence and strong recommendation for promoting lifestyle modification, as recommended in the 2017 Hypertension Clinical Practice Guidelines for ACC/AHA elevated BP population as an important strategy for controlling HBP. |

| QM-2 | Nonpharmacological interventions for ACC/AHA stage 1 HBP | Physician group practice, accountable care organization, clinically integrated network, health plan, integrated delivery system | Adds new emphasis high-quality evidence and strong recommendation for promoting lifestyle modification, as recommended in the 2017 Hypertension Clinical Practice Guidelines for ACC/AHA stage 1 population as an important strategy for controlling HBP. |

| QM-3 | Nonpharmacological interventions for all ACC/AHA stages of HBP (composite measure combining PM-4, QM-1, and QM-2) | Physician group practice, accountable care organization, clinically integrated network, health plan, integrated delivery system | Adds new emphasis on high-quality evidence and strong recommendation for promoting lifestyle modification, as recommended in the 2017 Hypertension Clinical Practice Guidelines for all 3 ACC/AHA stages of HBP population as an important strategy for controlling HBP. Composite measure permits assessment of effectiveness for all stages combined. |

| QM-4 | Medication adherence to drug therapy for ACC/AHA stage 1 with ASCVD risk ≥10% or ACC/AHA stage 2 HBP | Physician group practice, accountable care organization, clinically integrated network, health plan, integrated delivery system | Adds new emphasis on high-quality evidence and strong recommendation for assessing and promoting medication adherence, as recommended in the 2017 Hypertension Clinical Practice Guidelines for the combined ACC/AHA stage 1 with ASCVD risk ≥10% and ACC/AHA stage 2 HBP population as an important strategy for controlling HBP. |

| QM-5 | Use of HBPM for management of ACC/AHA stage 1 HBP | Physician group practice, accountable care organization, clinically integrated network, health plan, integrated delivery system | Harmonizes with new performance measure PM-5 for ACC/AHA stage 2 HBP. Adds new emphasis on correct measurement of BP by individuals at home or elsewhere outside the clinic setting, as recommended in the 2017 Hypertension Clinical Practice Guidelines for this population as an important strategy for evaluating control of ACC/AHA stage 1 HBP and ASCVD risk ≥10%. |

| QM-6 | Use of HBPM for management of ACC/AHA stage 1 or ACC/AHA stage 2 (composite measure combining PM-5 and QM-5) | Healthcare provider (healthcare provider, physician group practice, accountable care organization, clinically integrated network, health plan, integrated delivery system) | Harmonizes with new measures PM-5 and QM-5 and adds new emphasis on correct measurement of BP by individuals at home or elsewhere outside the clinic setting, as recommended in the 2017 Hypertension Clinical Practice Guidelines for this population as an important strategy for evaluating control of ACC/AHA stage 2 and stage 1 HBP and ASCVD risk ≥10%. Composite measure permits assessment of effectiveness for these 2 stages combined. |

| SM-1 | Use of a standard protocol to consistently and correctly measure BP in the ambulatory setting | CDU† | Accurate measurement and recording of BP are essential to categorize level of BP, ascertain BP-related CVD risk, and guide management of high BP. Office BP measurement is often unstandardized, despite the well-known consequences of inaccurate measurement. Errors are common and can result in a misleading estimation of an individual’s true level of BP if staff are not trained and a protocol is not followed. |

| SM-2 | Use of a standard process for assessing ASCVD risk | CDU† | To facilitate decisions about preventive interventions, it is recommended to screen for traditional ASCVD risk factors and apply the race- and sex-specific PCE (ASCVD Risk Estimator) to estimate 10-year ASCVD risk for asymptomatic adults 40-79 years of age. |

| SM-3 | Use of a standard process for properly screening all adults ≥18 y of age for HBP | CDU† | The evidence on the benefits of screening for HBP is well established. In 2007, the USPSTF reaffirmed its 2003 recommendation to screen for HBP in adults ≥18 y of age |

| SM-4 | Use of an EHR to accurately diagnose and assess HBP control | CDU† | A growing number of health systems are developing or using registries and EHRs that permit large-scale queries to support population health management strategies to identify undiagnosed or undertreated HBP. |

| SM-5 | Use of a standard process to engage patients in shared decision-making, tailored to their personal benefits, goals, and values for evidence-based interventions to improve control of HBP | CDUf | Decisions about primary prevention should be collaborative decisions made between a clinician and a patient. |

| SM-6 | Demonstration of infrastructure and personnel that assess and address social determinants of health of patients with HBP | CDU† | It is important to tailor advice to an individual’s socioeconomic and educational status, as well as cultural, work, and home environments. |

| SM-7 | Use of team-based care to better manage HBP | CDU† | RCTs and meta-analyses of RCTs of team-based HBP care involving nurse or pharmacist intervention demonstrated reductions in SBP and DBP and/or greater achievement of BP goals when compared with usual care. |

| SM-8 | Use of telehealth, m-health, e-health, and other digital technologies to better diagnose and manage HBP | CDU† | Meta-analyses of RCTs of different telehealth interventions have demonstrated greater SBP and DBP reductions and a larger proportion of patients achieving BP control than those achieved with usual care without telehealth. |

| SM-9 | Use of a single, standardized plan of care for all patients with HBP | CDU† | Studies demonstrate that implementation of a plan of care for HBP can lead to sustained reduction of BP and attainment of BP targets over several years. |

| SM-10 | Use of performance and quality measures to improve quality of care for patients with HBP | CDU† | A large observational study showed that a systematic approach to HBP control, including the use of performance measures, was associated with significant improvement in HBP control compared with historical control groups. |

Including office, clinic, home, or ambulatory.

Including, but not limited to, solo/small physician offices, group practices, ambulatory care centers, health systems, public health sites, accountable care organizations, and clinically integrated networks that diagnose and treat patients with HBP.

ACC indicates American College of Cardiology; AHA, American Heart Association; ASCVD, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; BP, blood pressure; CDU, care delivery unit; CVD, cardiovascular disease; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; e-health, healthcare services provided electronically via the Internet; EHR, electronic health record; HBP, high blood pressure; HBPM, home blood pressure monitoring; m-health, practice of medicine and public health supported by mobile devices; PCE, pooled cohort equations; PM, performance measure; QM, quality measure; RCT, randomized controlled trial; SBP, systolic blood pressure; SM, structural measure; and USPSTF, US Preventive Services Task Force.

Quality measures, on the other hand, are intended to be deployed in collaborative quality improvement initiatives (such as those promoted by the ACC and AHA) that do not require the degrees of technical rigor required for performance measures. The writing committee decided to include 6 new process quality measures based on Class 1 recommendations from the 2017 Hypertension Clinical Practice Guidelines (4) recommendations that address important gaps in care for patients with HBP. If additional evidence evolves that demonstrates significant impact on the quality of care and meets NQF requirements for reliability, feasibility, usability, validity, and acceptable burden of data collection for these measures, then they may be considered as potential future performance measures by the writing committee and other entities, such as CMS, NCQA, state Medicaid agencies, and NQF.

Given the extensive emphasis on developing more effective systems of care for patients with HBP, the writing committee also feels it is important to present a new concept of structural measures, which are designed to improve these systems. This category of quality measure is intended to evaluate care at the aggregate care delivery unit (CDU) level, as opposed to the performance and quality measures, which are designed to summarize the evaluation of care of prespecified populations with HBP at the individual, group clinician, or health plan levels. A CDU represents the organizational structure of the clinicians who are delivering care to these patients. This measurement includes a hierarchical scale of the health delivery infrastructure for optimal management of patients with HBP that is available to organizations such as a small medical practice, a multispecialty clinic, a community-based health center (e.g., a Federally Qualified Health Center), a hospital-owned ambulatory care site, or even a large, geographically dispersed health system (e.g., the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs).

The writing committee developed this new category of 10 structural measures in hopes that they could be implemented within a CDU at any level of the health system to assess strengths and weaknesses of available infrastructure designed to improve accurate diagnosis and management of patients with HBP, again in accordance with relevant recommendations from the 2017 Hypertension Clinical Practice Guidelines (4). The writing committee emphasizes that expecting the structural measures to be interpreted as rigid requirements for CDUs would not permit the high level of flexibility these diverse entities need to use these measures for their own self-assessment and collaborative quality improvement implementation initiatives. Hence, these new measures are currently not designed or intended to be used for accountability “standards” but rather to be used as a roadmap for solo/small physician offices, group practices, health systems, public health sites, accountable care organizations, and clinically integrated networks, etc., in their collective journeys to establish better and more standardized guideline-based systems of care for the many millions of patients with HBP across the United States.

More detailed information on the specifications for these new performance, quality, and structural measures for care of patients with HBP is presented in Appendix A.

4. AREAS FOR FURTHER RESEARCH

Several additional areas of research will potentially have an impact on HBP performance and quality measures:

Further research is needed on devices for measuring BP for diagnosis and control, including continuous measurements from digital devices and entering BP measurements into electronic health records.

Further research is needed on improving the accuracy of office BP measurements, including appropriate technique, number of measurements, and training of healthcare providers in measuring BP to help standardize care and improve utilization of performance measures.

Technology for measurement of BP continues to evolve. Several ambulatory BP monitoring and home BP monitoring devices, including cuffless devices that incorporate optical BP monitoring algorithms, are available, although out-of-office BP measurements using validated upper-arm devices with appropriately sized cuffs are recommended to confirm the diagnosis of HBP and for titration of BP-lowering medications. Additional data on accuracy, reproducibility, costs, and device comparisons are needed.

The field would benefit from further research on how improvement in HBP measurement, such as the use of home BP monitoring and use of a standard protocol to measure BP accurately, as incorporated into guideline-based clinical interventions (e.g., AHA and AMA Target: BP), translates into improvement in BP care (26).

Field testing is needed to determine the utilization of new process and structural quality measures for the future development of new performance measures. This is especially true for lifestyle modifications, shared decision making, and implementation of a standardized protocol to consistently and correctly measure BP.

Efforts to standardize BP data entry into electronic health records are needed to improve diagnosis and management of HBP. These include entering multiple readings and averages of readings, with electronic health record systems having the ability to perform the averaging function automatically for multiple BP readings within a visit and across ≥2 visits. Future HBP patient registries should include a broader range of races/ethnicities and incorporate data on other socioeconomic determinants of health, as well as patient engagement and activation, to better understand the impact of these variables on medication adherence and BP control.

Continued research to examine temporal trends and disparities (with respect to sex, race/ethnicity, and socioeconomic status) in the achievement of performance and quality measures is critical for future revisions of these measure sets. Before adoption of behavioral and motivational strategies as new performance measures, prospective studies evaluating their efficacy in achieving a healthy lifestyle and a standardized process for patient-centered shared decision making for BP control are needed.

Utilization of new performance measures in public accountability and payment programs is needed. The impact of inclusion of HBP performance measures in pay-for-performance strategies on HBP diagnosis, management, and outcomes should be prospectively evaluated. The impact of compliance with some or all performance measures on hospital quality of care and short- and long-term clinical outcomes should be assessed.

The HBP performance measures may further evolve on the basis of additional evidence, along with future focused updates and revisions to the 2017 Hypertension Clinical Practice Guidelines.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Developed in Collaboration With the American Medical Association and the Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association

Endorsed by the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation, American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, American Nurses Association, American Society for Preventive Cardiology, American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, and Association of Black Cardiologists

This Physician Performance Measurement Set (PPMS) and related data specifications were developed by the Physician Consortium for Performance Improvement (the Consortium), including the American College of Cardiology (ACC), the American Heart Association (AHA), and the American Medical Association (AMA), to facilitate quality-improvement activities by physicians. The performance measures contained in this PPMS are not clinical guidelines, do not establish a standard of medical care, and have not been tested for all potential applications. Although copyrighted, they can be reproduced and distributed, without modification, for noncommercial purposes for example, use by health care providers in connection with their practices. Commercial use is defined as the sale, license, or distribution of the performance measures for commercial gain, or incorporation of the performance measures into a product or service that is sold, licensed, or distributed for commercial gain. Commercial uses of the PPMS require a license agreement between the user and the AMA (on behalf of the Consortium) or the ACC or the AHA. Neither the AMA, ACC, AHA, the Consortium, nor its members shall be responsible for any use of this PPMS.

The measures and specifications are provided “as is” without warranty of any kind.

Limited proprietary coding is contained in the measure specifications for convenience. Users of the proprietary code sets should obtain all necessary licenses from the owners of the code sets. The AMA, the ACC, the AHA, the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA), and the Physician Consortium for Performance Improvement (PCPI) and its members disclaim all liability for use or accuracy of any Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) or other coding contained in the specifications.

CPT contained in the measures specifications is copyright 2004-2012 American Medical Association. LOINC copyright 2004-2012 Regenstrief Institute, Inc. This material contains SNOMED CLINICAL TERMS (SNOMED CT) copyright 2004-2012 International Health Terminology Standards Development Organization. All rights reserved.

This document underwent a 14-day peer review between March 18, 2019, and April 1, 2019, and a 30-day public comment period between March 18, 2019, and April 16, 2019.

The American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology make every effort to avoid any actual or potential conflicts of interest that may arise as a result of an outside relationship or a personal, professional, or business interest of a member of the writing panel. Specifically, all members of the writing group are required to complete and submit a Disclosure Questionnaire showing all such relationships that might be perceived as real or potential conflicts of interest.

This document was approved by the American College of Cardiology Clinical Policy Approval Committee and the American Heart Association Science Advisory and Coordinating Committee in June 2019; by the American Heart Association Executive Committee on August 9, 2019; and by the American Medical Association and the Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association on July 25, 2019.

This article has been copublished in Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes..

Copies: This document is available on the websites of the American College of Cardiology (www.acc.org) and the American Heart Association (professional.heart.org). A copy of the document is also available at https://professional.heart.org/statements by selecting the “Guidelines & Statements” button. To purchase additional reprints, call 843-216-2533 or kelle.ramsay@wolterskluwer.com.

The expert peer review of AHA-commissioned documents (eg, scientific statements, clinical practice guidelines, systematic reviews) is conducted by the AHA Office of Science Operations. For more on AHA statements and guidelines development, visit https://professional.heart.org/statements. Select the “Guidelines & Statements” drop-down menu near the top of the webpage, then click “Publication Development.”

Permissions: Multiple copies, modification, alteration, enhancement, and/or distribution of this document are not permitted without the express permission of the American College of Cardiology. Requests may be completed online via the Elsevier site (https://www.elsevier.com/about/our-business/policies/copyright/permissions).

REFERENCES

- 1.Spertus JA, Eagle KA, Krumholz HM, et al. American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association methodology for the selection and creation of performance measures for quantifying the quality of cardiovascular care. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:1147–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spertus JA, Bonow RO, Chan P, et al. ACCF/AHA new insights into the methodology of performance measurement: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on performance measures. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:1767–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Drozda J, Messer JV, Spertus J, et al. ACCF/AHA/AMA-PCPI 2011 performance measures for adults with coronary artery disease and hypertension: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Performance Measures and the American Medical Association-Physician Consortium for Performance Improvement. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:316–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71:e127–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure. Hypertension. 2003;42:1206–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA). Controlling high blood pressure (CPB). Available at: https://www.ncqa.org/hedis/measures/controlling-high-blood-pressure/. Accessed July 15, 2019.

- 7.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. HTN-2 (NQF 0018): controlling high blood pressure. Available at: https://qpp.cms.gov/docs/QPP_quality_measure_specifications/Web-Interface-Measures/2019_Measure_HTN2_CMSWebInterface.pdf. Accessed July 15, 2019.

- 8.Crawford C AAFP decides to not endorse AHA/ACC hypertension guideline. Available at: https://www.aafp.org/news/health-of-the-public/20171212notendorseaha-accgdlne.html. Accessed July 15, 2019.

- 9.Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W, et al. 2018 ESC/ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology and the European Society of Hypertension. J Hypertens. 2018;36:1953–2041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Committee for Quality Assurance. NCQA updates quality measures for HEDIS® 2019. Available at: https://www.ncqa.org/news/ncqa-updates-quality-measures-for-hedis-2019/. Accessed July 15, 2019.

- 11.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. CMS expands coverage of ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM). Available at: https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/cms-expands-coverage-ambulatory-blood-pressure-monitoring-abpm11. Accessed July 22, 2019.

- 12.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Decision memo for ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM) (CAG-00067R2). Available at: https://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/details/nca-decision-memo.aspx?NCAId=294. Accessed July 22, 2019.

- 13.Byrd JB, Brook RD. Hypertension. Ann Intern Med. 2019;170:ITC65–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, et al. 2019 ACC/AHA guideline on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019; 74:e177–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.US Preventive Services Task Force. Final recommendation statement: high blood pressure in adults: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/high-blood-pressure-in-adults-screening. Accessed July 15, 2019.

- 16.Muntner P, Carey RM, Gidding S, et al. Potential US population impact of the 2017 ACC/AHA high blood pressure guideline. Circulation. 2018;137:109–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chow CK, Teo KK, Rangarajan S, et al. Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in rural and urban communities in high-, middle-, and low-income countries. JAMA. 2013;310:959–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Colantonio LD, Booth JN, Bress AP, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA blood pressure treatment guideline recommendations and cardiovascular risk. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72:1187–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kirkland EB, Heincelman M, Bishu KG, et al. Trends in healthcare expenditures among US adults with hypertension: national estimates, 2003–2014. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7:e008731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bress AP, Colantonio LD, Cooper RS, et al. Potential cardiovascular disease events prevented with adoption of the 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association blood pressure guideline. Circulation. 2019;139:24–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bundy JD, Mills KT, Chen J, et al. Estimating the association of the 2017 and 2014 hypertension guidelines with cardiovascular events and deaths in US adults: an analysis of national data. JAMA Cardiol. 2018;3:572–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Quality Forum. Controlling high blood pressure: NQF measure 0018. Available at: http://www.qualityforum.org/QPS/MeasureDetails.aspx?standardID=1236&print=0&entityTypeID=1. Accessed July 15, 2019.

- 23.National Quality Forum. Guidance for measure harmonization. Available at: https://www.qualityforum.org/Publications/2011/05/Guidance_for_Measure_Harmonization.aspx. Accessed July15, 2019.

- 24.Normand SL, McNeil BJ, Peterson LE, et al. Eliciting expert opinion using the Delphi technique: identifying performance indicators for cardiovascular disease. Int J Qual Health Care. 1998;10:247–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thomas RJ, Balady G, Banka G, et al. 2018 ACC/AHA clinical performance and quality measures for cardiac rehabilitation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Performance Measures. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71: 1814–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Egan BM, Sutherland SE, Rakotz M, et al. Improving hypertension control in primary care with the Measure Accurately, Act Rapidly, and Partner With Patients protocol. Hypertension. 2018;72:1320–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cushman WC, Ford CE, Cutler JA, et al. Success and predictors of blood pressure control in diverse North American settings: the antihypertensive and lipid-lowering treatment to prevent heart attack trial (ALLHAT). J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2002;4:393–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dahlof B, Devereux RB, Kjeldsen SE, et al. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in the Losartan Intervention For Endpoint reduction in hypertension study (LIFE): a randomised trial against atenolol. Lancet. 2002;359:995–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ettehad D, Emdin CA, Kiran A, et al. Blood pressure lowering for prevention of cardiovascular disease and death: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2016;387:957–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guo X, Zhang X, Guo L, et al. Association between pre-hypertension and cardiovascular outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2013;15:703–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guo X, Zhang X, Zheng L, et al. Prehypertension is not associated with all-cause mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e61796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huang Y, Cai X, Li Y, et al. Prehypertension and the risk of stroke: a meta-analysis. Neurology. 2014;82: 1153–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huang Y, Cai X, Liu C, et al. Prehypertension and the risk of coronary heart disease in Asian and Western populations: a meta-analysis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2015; 4:e001519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huang Y, Cai X, Zhang J, et al. Prehypertension and incidence of ESRD: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;63:76–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huang Y, Su L, Cai X, et al. Association of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality with prehypertension: a meta-analysis. Am Heart J. 2014;167:160–8. e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huang Y, Wang S, Cai X, et al. Prehypertension and incidence of cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysis. BMC Med. 2013;11:177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Law MR, Morris JK, Wald NJ. Use of blood pressure lowering drugs in the prevention of cardiovascular disease: meta-analysis of 147 randomised trials in the context of expectations from prospective epidemiological studies. BMJ. 2009;338:b1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee M, Saver JL, Chang B, et al. Presence of baseline prehypertension and risk of incident stroke: a meta-analysis. Neurology. 2011;77:1330–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lewington S, Clarke R, Qizilbash N, et al. Age-specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: a meta-analysis of individual data for one million adults in 61 prospective studies. Lancet. 2002; 360:1903–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rapsomaniki E, Timmis A, George J, et al. Blood pressure and incidence of twelve cardiovascular diseases: lifetime risks, healthy life-years lost, and age-specific associations in 1.25 million people. Lancet. 2014;383:1899–911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shen L, Ma H, Xiang M-X, et al. Meta-analysis of cohort studies of baseline prehypertension and risk of coronary heart disease. Am J Cardiol. 2013;112:266–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sundstrom J, Arima H, Jackson R, et al. Effects of blood pressure reduction in mild hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162:184–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thomopoulos C, Parati G, Zanchetti A. Effects of blood pressure lowering on outcome incidence in hypertension: 2. Effects at different baseline and achieved blood pressure levels-overview and meta-analyses of randomized trials. J Hypertens. 2014;32: 2296–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wald DS, Law M, Morris JK, et al. Combination therapy versus monotherapy in reducing blood pressure: meta-analysis on 11,000 participants from 42 trials. Am J Med. 2009;122:290–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang S, Wu H, Zhang Q, et al. Impact of baseline prehypertension on cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality in the general population: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168:4857–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xie X, Atkins E, Lv J, et al. Effects of intensive blood pressure lowering on cardiovascular and renal outcomes: updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2016;387:435–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Margolis KL, Asche SE, Bergdall AR, et al. Effect of home blood pressure telemonitoring and pharmacist management on blood pressure control: a cluster randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2013;310:46–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McManus RJ, Mant J, Haque MS, et al. Effect of self-monitoring and medication self-titration on systolic blood pressure in hypertensive patients at high risk of cardiovascular disease: the TASMIN-SR randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;312:799–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Siu AL, on behalf of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for high blood pressure in adults: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163:778–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Uhlig K, Balk EM, Patel K, et al. Self-Measured Blood Pressure Monitoring: Comparative Effectiveness Prepared by the Tufts Evidence-based Practice Center under Contract No. HHSA 290–2007-10055-I. AHRQ Publication No. 12-EHC002-EF. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US), 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bangalore S, Toklu B, Gianos E, et al. Optimal systolic blood pressure target after SPRINT: insights from a network meta-analysis of randomized trials. Am J Med. 2017;130:707–19. e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bundy JD, Li C, Stuchlik P, et al. Systolic blood pressure reduction and risk of cardiovascular disease and mortality: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. JAMA Cardiol. 2017;2:775–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Thomopoulos C, Parati G, Zanchetti A. Effects of blood pressure lowering on outcome incidence in hypertension: 7. Effects of more vs. less intensive blood pressure lowering and different achieved blood pressure levels - updated overview and meta-analyses of randomized trials. J Hypertens. 2016;34:613–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Verdecchia P, Angeli F, Gentile G, et al. More versus less intensive blood pressure-lowering strategy: cumulative evidence and trial sequential analysis. Hypertension. 2016;68:642–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Borden WB, Maddox TM, Tang F, et al. Impact of the 2014 expert panel recommendations for management of high blood pressure on contemporary cardiovascular practice: insights from the NCDR PINNACLE registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:2196–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jaffe MG, Lee GA, Young JD, et al. Improved blood pressure control associated with a large-scale hypertension program. JAMA. 2013;310:699–705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rakotz MK, Ewigman BG, Sarav M, et al. A technology-based quality innovation to identify undiagnosed hypertension among active primary care patients. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12:352–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Williamson JD, Supiano MA, Applegate WB, et al. Intensive vs standard blood pressure control and cardiovascular disease outcomes in adults aged ≥75 years: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;315: 2673–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ambrosius WT, Sink KM, Foy CG, et al. The design and rationale of a multicenter clinical trial comparing two strategies for control of systolic blood pressure: the Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT). Clin Trials. 2014;11:532–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cushman WC, Grimm RH, Cutler JA, et al. Rationale and design for the blood pressure intervention of the Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes (ACCORD) trial. Am J Cardiol. 2007;99:44i–55i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Asayama K, Thijs L, Li Y, et al. Setting thresholds to varying blood pressure monitoring intervals differentially affects risk estimates associated with white-coat and masked hypertension in the population. Hypertension. 2014;64:935–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fagard RH, Cornelissen VA. Incidence of cardiovascular events in white-coat, masked and sustained hypertension versus true normotension: a meta-analysis. J Hypertens. 2007;25:2193–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mancia G, Bombelli M, Brambilla G, et al. Long-term prognostic value of white coat hypertension: an insight from diagnostic use of both ambulatory and home blood pressure measurements. Hypertension. 2013;62:168–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.National Clinical Guideline Centre (UK). Hypertension in adults: diagnosis and management. NICE Clinical Guidelines, No. 127. London, UK: Royal College of Physicians (UK), 2011. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg127. Accessed July 15, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ohkubo T, Kikuya M, Metoki H, et al. Prognosis of “masked” hypertension and “white-coat” hypertension detected by 24-h ambulatory blood pressure monitoring 10-year follow-up from the Ohasama study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:508–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pickering TG, James GD, Boddie C, et al. How common is white coat hypertension? JAMA. 1988;259: 225–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pierdomenico SD, Cuccurullo F. Prognostic value of white-coat and masked hypertension diagnosed by ambulatory monitoring in initially untreated subjects: an updated meta analysis. Am J Hypertens. 2011;24: 52–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Piper MA, Evans CV, Burda BU, et al. Diagnostic and predictive accuracy of blood pressure screening methods with consideration of rescreening intervals: a systematic review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162:192–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Qualified Electronic Health Record Law and Legal Definition. Available at: https://definitions.uslegal.com/q/qualified-electronic-health-record/. Accessed July 15, 2019.

- 70.NQRN. PCPI’s Registry Community. Available at: https://www.thepcpi.org/page/NQRNresources. Accessed July 15, 2019.

- 71.Svetkey LP, Simons-Morton D, Vollmer WM, et al. Effects of dietary patterns on blood pressure: subgroup analysis of the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) randomized clinical trial. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:285–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Howard G, Cushman M, Moy CS, et al. Association of clinical and social factors with excess hypertension risk in black compared with white US adults. JAMA. 2018;320:1338–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Nordmann AJ, Suter-Zimmermann K, Bucher HC, et al. Meta-analysis comparing Mediterranean to low-fat diets for modification of cardiovascular risk factors. Am J Med. 2011;124:841–51. e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Estruch R, Ros E, Salas-Salvado J, et al. Retraction and republication: primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with a Mediterranean diet. N Engl J Med 2013;368:1279–90. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:2441–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bazzano LA, Hu T, Reynolds K, et al. Effects of low-carbohydrate and low-fat diets: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161:309–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.He J, Wofford MR, Reynolds K, et al. Effect of dietary protein supplementation on blood pressure: a randomized, controlled trial. Circulation. 2011;124: 589–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yokoyama Y, Nishimura K, Barnard ND, et al. Vegetarian diets and blood pressure: a meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:577–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sepucha KR, Scholl I. Measuring shared decision making: a review of constructs, measures, and opportunities for cardiovascular care. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2014;7:620–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Elwyn G, Frosch D, Thomson R, et al. Shared decision making: a model for clinical practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27:1361–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Appel LJ, Champagne CM, Harsha DW, et al. Effects of comprehensive lifestyle modification on blood pressure control: main results of the PREMIER clinical trial. JAMA. 2003;289:2083–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Appel LJ, Moore TJ, Obarzanek E, et al. A clinical trial of the effects of dietary patterns on blood pressure. DASH Collaborative Research Group. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:1117–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sacks FM, Svetkey LP, Vollmer WM, et al. Effects on blood pressure of reduced dietary sodium and the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet. DASH-Sodium Collaborative Research Group. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:3–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Aburto NJ, Ziolkovska A, Hooper L, et al. Effect of lower sodium intake on health: systematic review and meta-analyses. BMJ. 2013;346:f1326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Graudal NA, Hubeck-Graudal T, JGrgens G. Effects of low-sodium diet vs. high-sodium diet on blood pressure, renin, aldosterone, catecholamines, cholesterol, and triglyceride (Cochrane Review). Am J Hypertens. 2012;25:1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.He FJ, Li J, Macgregor GA. Effect of longer term modest salt reduction on blood pressure: Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials. BMJ. 2013;346:f1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Mozaffarian D, Fahimi S, Singh GM, et al. Global sodium consumption and death from cardiovascular causes. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:624–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Whelton PK, Appel LJ, Espeland MA, et al. Sodium reduction and weight loss in the treatment of hypertension in older persons: a randomized controlled trial of nonpharmacologic interventions in the elderly (TONE). TONE Collaborative Research Group. JAMA. 1998;279:839–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Aburto NJ, Hanson S, Gutierrez H, et al. Effect of increased potassium intake on cardiovascular risk factors and disease: systematic review and meta-analyses. BMJ. 2013;346:f1378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Geleijnse JM, Kok FJ, Grobbee DE. Blood pressure response to changes in sodium and potassium intake: a metaregression analysis of randomised trials. J Hum Hypertens. 2003;17:471–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Whelton PK, He J. Health effects of sodium and potassium in humans. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2014;25:75–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Whelton PK, He J, Cutler JA, et al. Effects of oral potassium on blood pressure. Meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials. JAMA. 1997;277: 1624–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.World Health Organization. Potassium intake for adults and children: guideline. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2012. Available at: https://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/guidelines/potassium_intake/en/. Accessed July 15, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Dickinson HO, Mason JM, Nicolson DJ, et al. Lifestyle interventions to reduce raised blood pressure: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Hypertens. 2006;24:215–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Lang T, Nicaud V, Darne B, et al. Improving hypertension control among excessive alcohol drinkers: a randomised controlled trial in France. The WALPA Group. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1995;49:610–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Roerecke M, Kaczorowski J, Tobe SW, et al. The effect of a reduction in alcohol consumption on blood pressure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health. 2017;2:e108–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Stewart SH, Latham PK, Miller PM, et al. Blood pressure reduction during treatment for alcohol dependence: results from the Combining Medications and Behavioral Interventions for Alcoholism (COMBINE) study. Addiction. 2008;103:1622–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Wallace P, Cutler S, Haines A. Randomised controlled trial of general practitioner intervention in patients with excessive alcohol consumption. BMJ. 1988;297:663–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Xin X, He J, Frontini MG, et al. Effects of alcohol reduction on blood pressure: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Hypertension. 2001;38:1112–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.The effects of nonpharmacologic interventions on blood pressure of persons with high normal levels. Results of the Trials of Hypertension Prevention, Phase I. JAMA. 1992;267:1213–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]