Abstract

Introduction:

Increasing the knowledgebase of anopheline larval ecology could enable targeted deployment of malaria control efforts and consequently reduce costs of implementation. In Malawi, there exists a knowledge gap in anopheline larval ecology and, therefore, basis for targeted deployment of larval source management (LSM) for malaria control, specifically larvicides. We set out to characterize anopheline larval habitats in the Majete area of Malawi on the basis of habitat ecology and anopheline larval productivity to create a basis for larval control initiatives in the country.

Methods:

Longitudinal surveys were conducted in randomly selected larval habitats over a period of fifteen months in Chikwawa district, southern Malawi. Biotic and abiotic parameters of the habitats were modelled to determine their effect on the occurrence and densities of anopheline larvae.

Results:

Seventy aquatic habitats were individually visited between 1–7 times over the study period. A total of 5,123 immature mosquitoes (3,359 anophelines, 1,497 culicines and 267 pupae) were collected. Anopheline and culicine larvae were observed in sympatry in aquatic habitats. Of the nine habitat types followed, dams, swamps, ponds, borehole runoffs and drainage channels were the five most productive habitat types for anopheline mosquitoes. Anopheline densities were higher in aquatic habitats with bare soil making up part of the surrounding land cover (p<0.01) and in aquatic habitats with culicine larvae (p<0.01) than in those surrounded by vegetation and not occupied by culicine larvae. Anopheline densities were significantly lower in highly turbid habitats than in clearer habitats (p<0.01). Presence of predators in the aquatic habitats significantly reduced the probability of anopheline larvae being present (p=0.04).

Conclusions:

Anopheline larval habitats are widespread in the study area. Presence of bare soil, culicine larvae, predators and the level of turbidity of water are the main determinants of anopheline larval densities in aquatic habitats in Majete, Malawi. While the most productive aquatic habitats should be prioritised, for the most effective control of vectors in the area all available aquatic habitats should be targeted, even those that are not characterized by the identified predictors. Further research is needed to determine whether targeted LSM would be cost-effective when habitat characterisation is included in cost analyses and to establish what methods would make the characterisation of habitats easier.

Keywords: Malaria mosquito, Larval ecology, Habitat characterization

Introduction

Larval source management (LSM) is designed to control mosquito densities by targeting the immature, aquatic stages of the mosquito (WHO 2013). It is thus considered a viable complimentary tool for malaria control next to long-lasting insecticidal nets (LLINs) and indoor residual spraying (IRS) (WHO 2013). Implementation of LSM has shown to reduce adult vector populations (Tusting et al. 2013) and hence reduce malaria burden in communities already using LLINs (Fillinger, Ndenga, et al. 2009). However, LSM is most likely to be successful in settings where potential mosquito larval habitats are few, fixed and findable (WHO 2013). Implementation of LSM could, thus, be operationally challenging in many parts of rural Malawi where these sites are extensive, numerous and difficult to access. In such cases, knowing which sites are most productive could enable targeted deployment of LSM in these selected sites.

The presence of mosquito larvae is dependent on unique ecological factors prevalent in each aquatic habitat. These factors should be thoroughly understood before LSM is executed. For example, smaller habitats typically have lower species diversity and may support lower densities of some mosquito species than larger habitats due to their transient nature (Sunahara et al. 2002, Koenraadt et al. 2004, Minakawa, et al. 2005, Mala and Irungu 2011). Other abiotic factors have also been observed to influence differential productivity of larval habitats. For instance, water temperature determines the rate at which feeding and metabolism occur, which affects the larval development rate (Clements 1992, Nayar et al. 1999, Bayoh and Lindsay 2003). Water turbidity and pH also influence mosquito diversity in aquatic habitats. Culicines have been observed to thrive in more turbid water than anophelines (Bukhari et al. 2011, Dida et al. 2018). Generally, in all mosquito species water pH below 4.5 or above 10 is associated with higher larval mortalities (Emidi et al. 2017). Biotic factors such as presence of larval competitors and predators, and vegetation play important roles in determining the suitability of larval habitats. For example, gravid mosquitoes avoid habitats occupied by their competitors (Impoinvil et al. 2008) and predators (Blaustein et al. 2004, Sumba et al. 2004). The avoidance of predator-infested habitats is attributed to the ability of gravid females to detect predator kairomones (Roberts 2014, Silberbush and Blaustein 2018). The role played by the presence of vegetation within or around larval habitats in influencing both larval diversity and density is well documented (Minakawa et al. 2005, Wamae et al. 2010). Besides altering the organic content of water through falling plant material (Muturi et al. 2008) thus influencing mosquito species composition in larval habitats, presence of vegetation also serves as either a larval food source (Mutuku et al. 2006) or shelter from predators and physical disturbances.

Understanding how the different habitat-associated ecological factors influence mosquito occurrence, abundance and diversity could assist in the development and deployment of effective larval control strategies (Stein et al. 2011). Mosquito larval habitat ecology has been understudied in Africa (Dida et al. 2018) and no such research has been documented for Malawi. This has operational implications for the deployment of LSM for malaria control. The present study was, therefore, undertaken to characterize potential anopheline larval habitats on the basis of their ecology and larval productivity in Malawi.

Material & Methods

Study area

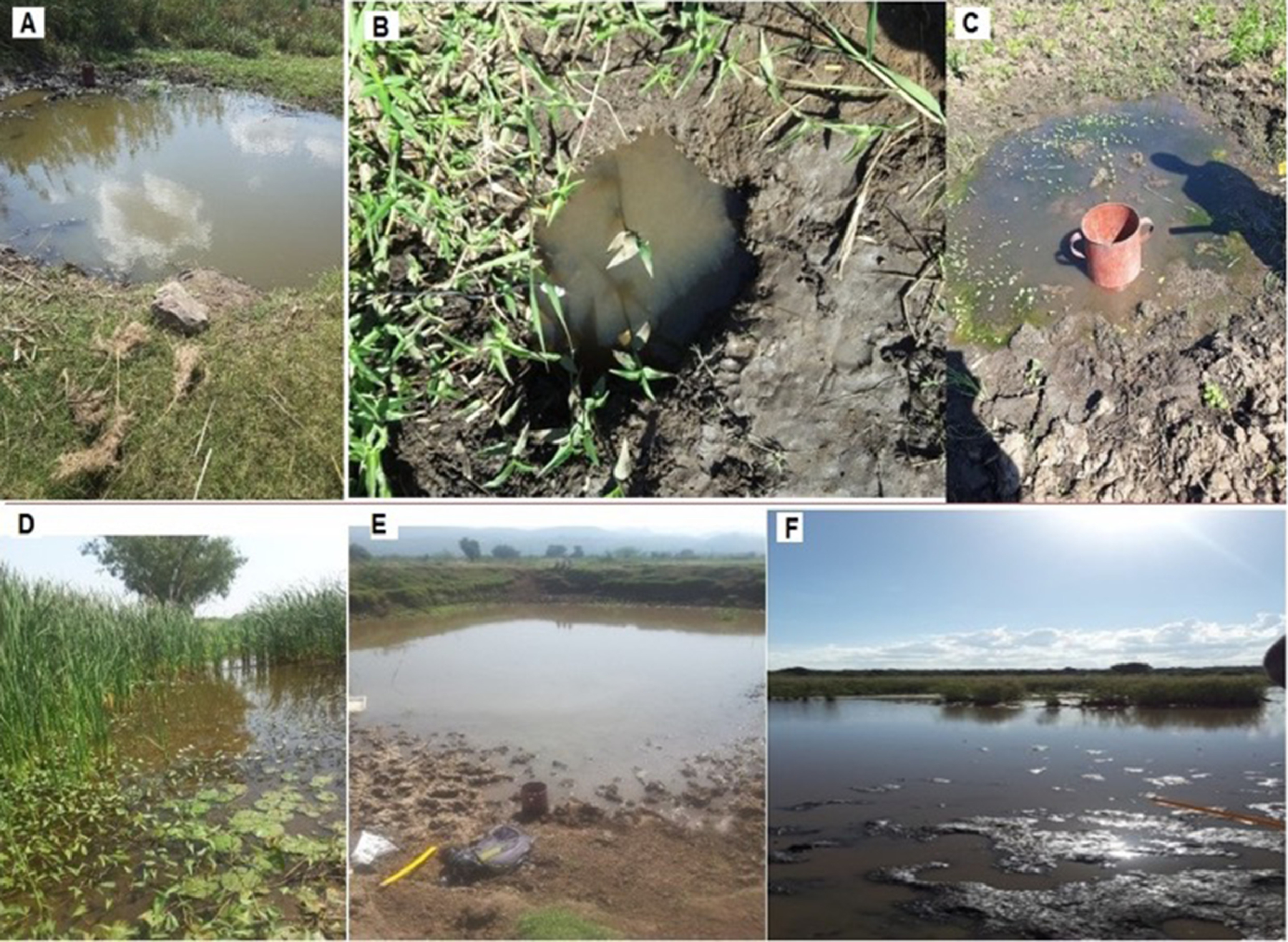

The study was undertaken in eight months, split between 2017 and 2018, in six villages which were participating in a community-led malaria control project known as the Majete Malaria Project (MMP) in Chikwawa district (16° 1' S; 34° 47' E), Malawi (Van Den Berg et al. 2018). These six villages were not included in the LSM arm of the MMP trial and hence were unaffected by the interventions. All study villages under MMP were divided into three regions referred to as focal areas A, B and C (McCann et al. 2017). The six study villages in the current study were evenly divided between focal areas B and C. Chikwawa district is an area of high malaria transmission in southern Malawi (Bennett et al. 2013). The area is hot and dry from September to December, hot and rainy from January to May, and cool and dry from June to August (Mzilahowa et al. 2012, Joshua et al. 2016). The higher temperatures and presence of water bodies create more humid environments, which further promote mosquito proliferation. The study areas are situated in river valleys, such that the terrain is generally flat but receives surface water runoff from the surrounding hilly watershed. The Shire River, the largest river in Malawi and only outlet of Lake Malawi, flows through Chikwawa District, including focal area B. This creates numerous breeding opportunities for mosquitoes. The smaller Mwanza River flows through focal area C. When the river dries, shallow wells are created for irrigation. Diverse potential mosquito larval habitats, including cattle hoof prints, brick-pits, wells, rice paddies and stream beds, are present in the area (Figure 1). The principal malaria vectors in this area are Anopheles gambiae s.s., An. arabiensis and An. funestus (Mzilahowa et al. 2012). Most inhabitants of the villages engage in millet cultivation and maize production. Furthermore, the majority of people keep livestock, with cattle and goats being the predominant animals.

Figure 1:

Examples of mosquito larval habitat types in the study area: (A) pond, (B) Well, (C) Borehole run-off, (D) Swamp, (E) Dam and (F) Stream bed

Selection of study villages and larval habitats

The study villages were selected using simple random sampling. Names of all villages per focal area not participating in the LSM arm of the larger project were written on cards and placed in a dish before an independent research assistant blindly selected three cards for each of the two focal areas (B and C). Within the confines of each of the six selected villages and in a 500 m radius outside the boundary of each village, all potential mosquito larval habitats were geo-referenced using the Global Positioning System (GPS) on Android-based tablets running Open Data Kit (ODK) (Anokwa et al. 2009, Hartung et al. 2010). A set of ten habitats was selected from the list of all mapped habitats in each selected village using simple spatially inhibitory random sampling. Here the minimum distance between the randomly selected habitats was set at 50 m (Chipeta et al. 2017). Because larval habitats can dry up over time, any selected habitat containing no water during the monitoring of larval habitats was replaced with the nearest neighbouring habitat that contained water regardless of habitat type. This effectively increased the total number of habitats visited from 60 to 70 as initially proposed. If no habitats with water were identified, habitats were selected from outside the 500 m buffer zone as long as there was no LSM activity ongoing in the area. In case of habitat flushing, which was a likely event in the rainy season, the habitats were visited when the water had stabilised or stopped overflowing.

Collection of ecological data

Based on their origin, their permanence, presence of vegetation and source of water, the potential larval habitats were classified into one of the following 11 categories: (1) Brick pits: water-filled pits resulting from brick-making, (2) Dam: artificial barrier constructed to hold water, (3) Drainage channel: artificial channel constructed to allow water passage, (4) Hoof print: an outline or indentation left by a hoof on the ground, (5) Pond: a naturally formed, permanent water body, (6) Rice field: an irrigated or flooded field where rice is grown, (7) Borehole runoff: a body of standing water resulting from overland flow of water from a borehole, (8) Swamp: an area of low-lying land with heavily water-saturated soil and dominated by plants, (9) Stream bed: a water body found in a natural water channel, (10) Well: a hole or pit created for purposes of exposing ground water and (11) Tyre tracks: an outline left by a tyre on the ground. All these habitat types fell into one of three main classes: natural, human-made/artificial and modified-natural. Following this classification, the following habitat-level biotic and abiotic parameters were recorded during each visit: geo-location, depth and area covered by water body, water turbidity, estimated duration of habitat exposure to sunlight per day, presence or absence of vegetation, substrate coverage, water surface temperature and pH, and presence of larval mosquito predators. The land use-land cover (LULC) profile of each habitat’s surroundings was also recorded, using the Braun Blanquet scale (Wikum and Shanholtzer 1978) to assign classes based on their percentage coverage: 0%, <5%, 6–10%, 11–25%, 26–50%, 51–75% and 76–100%. Water bodies that had dried up during the long dry season were not sampled until they contained water again.

Larval sampling

For each aquatic habitat, larvae were sampled from within an area sampler at one to three sampling points, which were equally distributed around the habitat perimeter. Collections were made between 9 am and 4 pm. The number of sampling points was based on the perimeter length of the habitat. For smaller habitats with perimeters equal or less than 10 m, one sampling point was selected. For habitats with perimeters larger than 10 m but less than 30 m, two sampling points were selected. Three samples were selected for all habitats with perimeters larger than 30 m. For each sample, an area sampler was used to mark the boundary of sampling and to prevent any mosquito larvae and predators from escaping sampling (Figure 1C). The area sampler was made of aluminium measuring 45 cm high with 27 cm diameter openings on both ends. The bottom lip of the sampler was serrated. Area samplers enable accurate estimation of larval density (Service 1993), and are more reliable than standard dippers in habitats with low larval densities (Fillinger et al. 2009). Standard 300 ml dippers, fish nets and pipettes were used to collect all mosquito larvae and pupae, and predators, from within the area sampler until all larvae were depleted. Reference to existing literature was the basis for determining which of the collected organisms were predacious (Shaalan and Canyon 2009, Sivagnaname 2009, Ohba et al. 2010, Kweka et al. 2011, Kundu et al. 2014, Dida et al. 2015, Benelli et al. 2016, Udayanga et al. 2019). All invertebrates were collected and separated into different orders such as Coleoptera, Odonata, Ephemeroptera and Hemiptera. Vertebrate predators such as fish and tadpoles were also recorded. All mosquito larvae were sorted by subfamily, anopheline or culicine, and separated by larval instar or pupal stage, and counted for entry into an Open Data Kit (ODK) form uploaded on a tablet. The number of anopheline larvae collected per area sampler yielded anopheline larval density per sampler. Per habitat, the anopheline larval density was calculated as sum of all anopheline larvae collected per area sampler divided by the number of samples taken for the habitat on the same day. A random sample of the collected anopheline larvae pooled from all habitat types was taken to a laboratory at the field station and reared to adults for further identification by microscopy using the keys of Gillies and Coetzee (1987) (Gillies and Coetzee 1987). Species identification within the Anopheles gambiae species complex and An. funestus group of mosquitoes were subsequently carried out by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) (Scott et al. 1993, Koekemoer et al. 2002).

Data analysis

Generalised linear mixed models were employed to quantify the effect of environmental variables on the density of Anopheles larvae. We first conducted bivariate tests to explore the variables that were significantly associated with the anopheline larval density. Non-parametric Mann-Whitney U and Kruskal Wallis tests were used to select which categorical variables go into the models. The associations between the response variable and continuous covariates were explored using Spearman’s correlation coefficient. The level of significance was set at 0.05. The significant covariates were then included in multivariable regressions to model density of Anopheles larvae, while adjusting for other covariates and also accounting for potential confounders. These regression models were fitted as zero-inflated negative binomial (ZINB) models, which included components to account for both over-dispersion and the high number of zeros in the data. The negative binomial component was fitted with a log link, while the zero-inflated component was fitted with a logit link. From the full model with all the covariates identified from the bivariate analyses, we employed a backward variable selection algorithm. The threshold was set as 0.25 so as not to discard variables which could be important in determining the anopheline larval density under actual field conditions. Thereafter, we fitted a ZINB mixed model using the covariates identified in the ZINB model in the preceding step. In addition to these covariates, this model added habitat as a random effect term in order to account for the repeated measurements at each habitat. All the analyses were performed using statistical package R version 3.6.1.

Results

Weather patterns

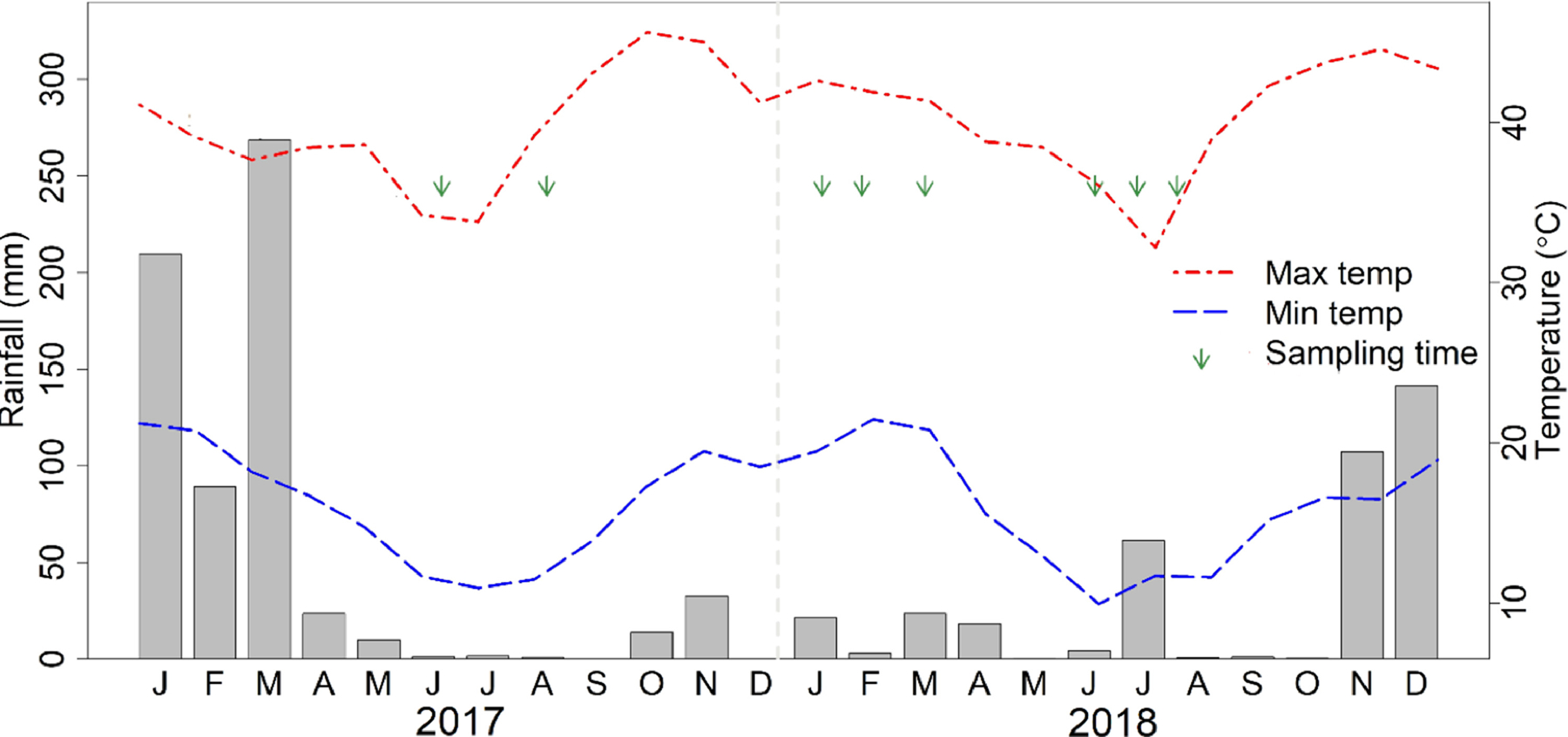

Weather conditions during the period of the study were recorded (Figure 2). June and July were the coldest months with minimum temperatures reaching 10°C. During warm months, September, October and November, maximum temperatures of over 40°C were observed. The highest total rainfall of around 300 mm was observed during the month of March in 2017. During the hot season, most potential larval habitats dried up, thus limiting mosquito breeding to larger permanent water bodies and small man-made wells dug for irrigation and domestic use in the dry season.

Figure 2:

Total monthly rainfall (mm; grey bars) and average, maximum and minimum temperatures (°C) over the study period. The data collection times are shown with green arrows.

Mosquito larval densities and diversity

Prior to commencement of data collection, a total of 140 potential habitats were mapped in all the six study villages. Ten habitats were randomly selected per village which resulted in 60 selected habitats. However, due to droughts that hit Malawi in 2016 and 2017 some of the selected habitats dried up in the course of the study and were replaced with nearby habitats in the same village. Effectively, 70 potential mosquito larval habitats were visited during the study, each between 1 to 7 times, for a total of 170 visits. Of the visited habitats, 46 (65.7%) were colonised by mosquito larvae during at least one visit. A total of 5,123 immature mosquitoes were observed: 3,359 anopheline larvae, 1,497 culicine larvae and 267 pupae in 39, 33 and 28 habitats, respectively (Table 1). Detailed taxonomic analysis by PCR was done on 330 anopheline larvae collected from positive habitats and reared to adult stage. Of these, 258 (78.2%) were An. arabiensis while 11 (3.3%) and 6 (1.8%) were An. quadriannulatus and An. gambiae s.s., respectively. Fifty-five of the anophelines initially identified as An. funestus s.l. based on morphological features were all confirmed to be An. funestus s.s. by PCR. All anopheline species were found sympatrically in some habitat types. Anopheles arabiensis were collected from all observed habitat types.

Tables 1:

The number of anopheline and culicine larvae and pupae collected (n = the number of water bodies in which the larvae were observed on at least one visit)

| Instar 1 | Instar 2 | Instar 3 | Instar 4 | Total (n) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anophelines | 1262 (n=34) |

1150 (n=39) |

666 (n=34) |

281 (n=24) |

3359 (39) |

| Culicines | 451 (n=30) |

512 (n=33) |

323 (n=32) |

211 (n=28) |

1497 (33) |

| Pupae | 267 (28) |

Productivity of larval habitat types

Ranked in terms of their contribution to the numbers of collected larvae per visit, dams, swamps, ponds, borehole runoffs and drainage channels were the five most productive habitat types. Collectively, these habitat types contributed 81.4% and 65.9% of the anopheline and culicine larvae observed, respectively (Table 2). Co-occurrence of the two mosquito subfamilies was observed in 39.5% (34/86) of all positive visits to habitats.

Table 2:

Contribution of the different habitat types to the number of immature mosquitoes collected

| Habitat type | No. sites | No. times sampleda (range) | Sites with immatures observed on ≥ 1 visit | Total immatures observed | Mean number per visit | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anophelinesb | Culicinesc | Pupaed | Anophelinesb | Culicinesc | Pupaed | Anophelinesb | Culicinesc | Pupaed | |||

| Dam | 4 | 10 (1–4) | 3 | 2 | 2 | 301 | 121 | 30 | 30.1 | 12.1 | 3 |

| Swamp | 10 | 34 (1–6) | 8 | 6 | 3 | 1020 | 417 | 32 | 30 | 12.3 | 0.9 |

| Pond | 4 | 14 (1–7) | 4 | 3 | 0 | 380 | 177 | 22 | 27.1 | 12.6 | 1.6 |

| Borehole runoff | 12 | 32 (1–6) | 6 | 5 | 5 | 866 | 245 | 70 | 27.1 | 7.7 | 2.2 |

| Drain-channel | 4 | 7 (1–2) | 2 | 1 | 0 | 168 | 27 | 0 | 24 | 3.9 | 0 |

| Rice field | 8 | 18 (1–6) | 7 | 7 | 1 | 271 | 287 | 10 | 15.1 | 15.9 | 0.6 |

| Well | 8 | 16 (1–3) | 5 | 6 | 2 | 152 | 116 | 54 | 9.5 | 7.3 | 3.4 |

| Streambed | 11 | 18 (1–2) | 5 | 6 | 3 | 153 | 107 | 17 | 8.5 | 5.9 | 0.9 |

| Brick pit | 9 | 21 (1–4) | 3 | 2 | 2 | 48 | 5 | 32 | 2.3 | 0.2 | 1.5 |

The number of times sampled is totaled across all sites while the range is per site.

Anopheline larvae

Culicine larvae

All mosquito pupae

Presence of mosquito larval predators

A diverse range of predators were collected from the potential larval habitats (Table S1). The predators included copepods and members of orders Odonata, Ephemeroptera, Hemiptera and Coleoptera. Vertebrate predators, amphibians and fish, were also found. The predators were collected in 75.3% (128/170) of all visits. Backswimmers and mayfly larvae were collected in 73% (93/128) and 55% (71/128) of the positive visits, respectively (Table S2). Amphibians and members of order Odonata were found in 26% of the positive visits. Water striders and fish were the least collected predators both in only 2% of the positive visits. Sympatry was observed in the types of habitats colonised by the predators. Backswimmers and mayfly larvae were collected in all habitat types while amphibians, water bugs, water scavenger beetles and, dragonfly and damselfly larvae were collected in eight of the nine habitat types. Copepods and water scorpions were both collected in five of the habitat types.

Temperature and pH of positive habitats

The habitats positive for the anopheline and culicine larvae had overlapping ranges of physiochemical properties (Table 3). The average water pH and temperature for all habitats in the study were 6.8 ± 0.1 and 28.6°C ± 0.3, respectively. The habitats colonised by anophelines had 6.71±0.2 and 28.4°C ± 0.4 as average water pH and temperature values. When the temperature range for all habitats visited was categorised into two: 19.4°C to 32°C and > 32°C to 40.8°C, more anopheline larvae were collected in the lower 19.4°C to 32°C temperature range (85.4%, 2809/3359) than in the upper (14.6%, 490/3359). The average pH and temperature values recorded in culicine habitats were 6.5 ± 0.2 and 27.8°C ± 0.4, respectively. Like with the anopheline larvae, more culicine larvae were collected in the lower 19.4°C to 32°C temperature range (88.6%, 1326/1497) than in the upper range (11.4%, 171/1497).

Table 3:

Range of physiochemical variables in habitats with anopheline and culicine larval presence

| Physiochemical variable | Subfamily | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anophelines | Culicines | |||

| Range | Mean ± SE | Range | Mean ±SE | |

| pH | 3.58 – 8.95 | 6.71±0.2 | 3.4 – 8.95 | 6.5±02 |

| Temperature (°C) | 21.6 – 37.8 | 28.4 ± 0.4 | 19.4 – 40.8 | 27.8±0.4 |

Effects of habitat and terrestrial factors

Of the 33 variables collected in the study, 10 variables were significantly associated with anopheline larval density (p< 0.05; Table S3). These variables were all included in the initial ZINB model before backward selection. Water temperature (p=0.071) was also included in the ZINB model because temperature can have a strong impact on mosquito development and survival (Paaijmans et al. 2008). Soil cover, turbidity of the water and the presence of both culicine larvae and predators were significant factors in the final ZINB model (Table 4). Based on the final ZINB model, anopheline densities were higher in aquatic habitats with bare soil making up part of the surrounding land cover (p<0.01) and in aquatic habitats with culicine larvae (p<0.01). The densities were significantly lower in highly turbid habitats (p<0.01) than in the least turbid habitats. The presence of predators in the aquatic habitats significantly reduced the probability of anopheline larvae being present (p=0.04).

Table 4:

Results of the ZINB mixed model (with log link and logit link functions) that examined the effects of aquatic and terrestrial variables on anopheline larval densities

| Variable* | Coefficient | SE | Z-value | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count model coefficients (negbin with log link) | ||||

| (Intercept) | 0.81 | 0.5382 | 1.505 | 0.13 |

| Soil cover ≤20 m | 1.94 | 0.5145 | 3.767 | <0.01 |

| Medium turbidity | −0.34 | 0.4469 | −0.766 | 0.44 |

| High turbidity | −4.34 | 1.0943 | −3.964 | <0.01 |

| Presence of culicine larvae | 1.27 | 0.4195 | 3.025 | <0.01 |

| Zero-inflation model coefficients (negbin with logit link) | ||||

| (Intercept) | 1.28 | 0.5276 | 2.42 | 0.02 |

| Presence of predator(s) | −1.33 | 0.6469 | −2.054 | 0.04 |

variable levels recorded using the Braun Blanquet scale (assigned 7 classes: 0%, <5%, 6–10%, 11–25%, 26–50%, 51–75% and 76–100%) were reduced to 2 levels (presence and absence).

Discussion

Habitat factors determine both mosquito larval densities and diversity, and consequently malaria transmission. We characterised anopheline larval habitats on the basis of their ecology and larval productivity. The results showed that all the habitat types prevalent in the study area contributed to the production of anopheline larvae but with differing densities. Anopheles arabiensis was the most abundant anopheline species and was collected in all types of the habitats examined. Higher anopheline larval densities were associated with presence of bare soil around the habitat and the presence of culicine larvae. Habitats with high turbidity and those with predators were associated with lower anopheline densities.

In addition to An. arabiensis being the most abundant anopheline species in our larval sampling, other members of the An. gambiae s.l. complex (An. quadriannulatus and An. gambiae s.s.) as well as An. funestus s.s. were collected from aquatic habitats in the study area. The greater abundance of An. arabiensis relative to An. gambiae s.s. and An. quadriannulatus agrees with multiple recent studies in the Majete area that have sampled adult mosquitoes in and near houses (Kabaghe et al. 2018, Mburu et al. 2019, Mburu et al. 2019). Adult An. funestus were also relatively common in those previous studies, though at lower abundances than An. arabiensis.

Nine larval habitat types with varied contribution to anopheline larval densities were identified in the study area. The number of habitat types observed was lower than would be expected in a normal year when enough rains fall. For example, due to the drought during the study period, hoof prints could not be counted as stand-alone habitats as they were only found to contain water when they existed within other more permanent habitat types such as dams, swamps and ponds. Dams, swamps, ponds, borehole runoffs and drainage channels were the five most productive habitat types for anopheline mosquitoes. The contribution of most of these habitat types could be associated with their relatively larger sizes and also permanence as compared to the smaller, less stable habitat types also visited during the study. The larger-sized permanent larval habitats are likely to host more mosquito larvae at a time thus contributing more to larval productivity. However, by being more stable the larger habitats also accommodate larger numbers of competitor and predator species than smaller temporary habitats (Minakawa et al. 2004). Though not supporting as many larvae as larger habitats at a given time, the smaller habitats may contribute more to adult densities over time due to reduced loss of larvae from predation (Mwangangi et al. 2007). Further, the lower depth of smaller habitats allows efficient absorption of sunlight in the shallow water column which promotes photosynthetic processes enabling availability of food and also increasing the water temperature hence larval development (Muturi et al. 2008).

In this study, we found that presence of bare soil within a 20 m radius from larval habitats was signicantly associated with higher anopheline larval densities. Indeed, An. gambiae s.l. have previously been shown to utilize shallow temporary puddles over bare soil as larval habitats (Gimnig et al. 2001, Minakawa et al. 2005, Huang et al. 2006, Fillinger et al. 2009, Ndenga et al. 2011). This finding has implications on the seasonality of anopheline larvae in our study area where larval habitats are predominantly surrounded by short-lived seasonal vegetation types. Death of these seasonal vegetation types, in the dry season, would create more bare ground thus promoting selection of the formerly vegetation-surrounded habitats by gravid anophelines as the vegetation dies.

Presence of culicine larvae was associated with higher anopheline larval densities. Three plausible mechanisms would explain this phenomenon. First, presence of culicine larvae in the habitats might have served as an alternative prey to predators thus reducing predation on the anophelines. Second, the presence of cues emanating from culicine larvae in the habitats could signal both safe and resource-rich sites for oviposition by gravid anophelines. Co-occurrence of anophelines and culicines is possibly caused by cues emitted by either species such as oviposition pheromones (Mwingira et al. 2019). Third, both species may be using the same habitat information to select the habitats. Stable coexistence in different mosquito species is possible due to their ability to exploit different niches within the same water bodies (Gilbreath et al. 2013). However, occupying the same habitat could potentially lead to competitive interaction for either resources and space (Carrieri et al. 2003, Kweka et al. 2012), which may have detrimental effects on both larval development and survival (Blaustein and Margalit 2018). This may induce discrimination of habitats occupied by other species by gravid females. For example, in a study in Kenya higher densities of anopheline and culicine immatures were observed when they occurred individually and not simultaneously (Impoinvil et al. 2008).

In the current study increasing turbidity was associated with reduced anopheline larval densities. Significantly larger densities were observed in the least turbid water than in highly turbid water. This finding is consistent with observations made on anopheline mosquitoes where their numbers were positively associated with clean water (Bukhari et al. 2011, Dida et al. 2018). Increasing turbidity levels reduce light penetration into the water which reduces food resources via reduced photosynthetic processes (Chirebvu and Chimbari 2015) and microbial growth (Muturi et al. 2008). Other studies, however, have recorded higher anopheline numbers with increasing turbidity (Gimnig et al. 2001, Fillinger et al. 2009, Mereta et al. 2013). Turbidity is caused by particles such as clay and silt, finely divided organic matter, plankton and microorganisms (Paaijmans et al. 2008). Therefore, whether turbidity influences mosquito larval presence likely depends on the absolute level (rather than the relative level) and the particles responsible for it. Habitats with moderate turbidity caused by edible particles are suitable for mosquito larvae (Sattler et al. 2005). Excessively turbid water, regardless of causative particles, reduces larval densities in An. gambiae s.l. (Ye-Ebiyo et al. 2003), as also confirmed by our results. Turbidity is considered an important index in larval monitoring of mosquito larvae (Chirebvu and Chimbari 2015).

The presence of predators was associated with reduced anopheline larval densities in the aquatic larval habitats. In this study a wide range of predators was recorded, both invertebrate and vertebrate. Direct predation of the larvae by the predators and avoidance by gravid mosquitoes to oviposit in predator infested habitats are likely the main explanations for reduced larval densities in such habitats. Gravid mosquitoes are known to detect cues emanating from predators thus avoid habitats from which the cues are coming (Blaustein et al. 2004, Munga et al. 2006). This was further confirmed by a dual choice study (Munga et al. 2006) in which An. gambiae s.s. provided with water conditioned with backswimmers and tadpoles or control non-conditioned water showed reduced oviposition output in the former compared to the latter. These phenomena have been observed in mosquitoes against many other species of predators (Munga et al. 2006, Roberts 2014). Since smaller habitats do not support large predator densities (Collins et al. 2019), predation rates in such habitats are low (Sunahara et al. 2002) hence they are more preferred by some anopheline species (Minakawa et al. 2004).

Our findings suggest that for more efficient anopheline larval control, less turbid habitats surrounded by bare soils and colonised by culicine larvae should be prioritised. Based on the findings, dams, swamps, ponds, borehole runoffs and drainage channels were the five most productive habitat types and should be prioritised by larval control efforts. However, all water bodies could be potential contributors to the mosquito populations and should be addressed if logistics, manpower and resources allow. Moreover, treatment of all available habitats has been shown to achieve higher mosquito reductions than selective habitat treatment (Dambach et al. 2019). Though observed to be less costly (Dambach et al. 2016) due to fewer habitats targeted for treatment, selective treatment of habitats could be more costly in terms of labour and time requirements if habitat characterisation to determine the most productive habitats is factored into the analyses.

The current study had some limitations. First, many habitats were of a temporal nature, which resulted in fewer repeated samples. Some sites were found to have water only once. Although this could not be avoided due to the highly seasonal occurrence of rainfall in the study area, this made investigation of effects of temporal changes on anopheline larval densities difficult for such sites. For this reason, all habitats that dried up during the course of the study were replaced with nearby habitats. Second, the lack of a significant influence of water temperature in determining anopheline larval densities could be attributed to limitations in our study design to account for the effect of hourly changes in water temperature. It is likely that at some time points, especially the early afternoon when the solar radiation is highest, larval densities are highly impacted by the higher temperatures which reach thermal death points (Paaijmans et al. 2008). Although logistically challenging, collecting larvae within the same, relatively small time frame, would reduce the range of surface water temperature, and we expect that temperature would then become a significant variable in predicting the presence of anopheline larvae.

The current study has shown that the presence of bare soil, culicine larvae, predators and the level of turbidity of water are the main factors determining anopheline larval densities in aquatic habitats in Majete, Malawi. These determinants provide basic associations between ecological variables and anopheline larval density, which could be used to guide deployment of targeted larval control. However, for the most effective control of vectors in the area all available aquatic habitats should be targeted, even those that are not characterized by the determined predictors. Further research is needed to determine whether targeted LSM would be cost-effective when habitat characterisation is included in cost analyses and to establish what methods would make the characterisation of habitats easier.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the Dioraphte Foundation, the Netherlands, for generous financial support. We are grateful to African Parks Majete for logistical assistance and access to their facilities. We thank Kim Mphwatiwa, Spencer Nchingula, Davies Kazembe and Happy Chongwe for the significant contributions they made in data collection. We also thank Asante Kadama, Richard Nkhata and Tinashe Tizifa for logistical support.

Funding

The study was funded by Dioraphte Foundation, the Netherlands. RSM received additional support from an NIH-funded postdoctoral fellowship (T32AI007524). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funders.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets for this study are available upon a reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- Anokwa Y, Hartung C, Brunette W, Borriello G, and Lerer A. 2009. Open data kit: tools to build information services for developing regions. In Computer. 42:10. [Google Scholar]

- Bayoh MN, and Lindsay SW. 2003. Effect of temperature on the development of the aquatic stages of Anopheles gambiae sensu stricto (Diptera: Culicidae). Bull. Entomol. Res 93: 375–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benelli G, Jeffries CL, and Walker T. 2016. Biological control of mosquito vectors: Past, present, and future. Insects 7: 1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett A, Kazembe L, Mathanga DP, Kinyoki D, Ali D, Snow RW, and Noor AM. 2013. Mapping malaria transmission intensity in Malawi, 2000–2010. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg 89: 840–849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Den Berg H, Van Vugt M, Kabaghe AN, Nkalapa M, Kaotcha R, Truwah Z, Malenga T, Kadama A, Banda S, Tizifa T, Gowelo S, Mburu MM, Phiri KS, Takken W, and McCann RS. 2018. Community-based malaria control in southern Malawi: A description of experimental interventions of community workshops, house improvement and larval source management. Malar. J 17: 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaustein L, Kiflawi M, Eitam A, Mangel M, and Cohen JE. 2004. Oviposition habitat selection in response to risk of predation in temporary pools: Mode of detection and consistency across experimental venue. Oecologia 138: 300–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaustein L, and Margalit J. 2018. Mosquito Larvae (Culiseta longiareolata) Prey Upon and Compete with Toad Tadpoles (Bufo viridis). J. Anim. Ecol 63: 841–850. [Google Scholar]

- Bukhari T, Takken W, Githeko AK, and Koenraadt CJM. 2011. Efficacy of aquatain, a monomolecular film, for the control of malaria vectors in rice paddies. PLoS One 6:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrieri M, Bacchi M, Bellini R, and Maini S. 2003. On the Competition Occurring Between Aedes albopictus and Culex pipiens (Diptera: Culicidae) in Italy. Environ. Entomol 32: 1313–1321. [Google Scholar]

- Chipeta M, Terlouw D, Phiri K, and Diggle P. 2017. Inhibitory geostatistical designs for spatial prediction taking account of uncertain covariance structure. Environmetrics 28:1. [Google Scholar]

- Chirebvu E, and Chimbari MJ. 2015. Characteristics of Anopheles arabiensis larval habitats in Tubu village, Botswana. J. Vector Ecol 40: 129–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clements AN 1992. The biology of mosquitoes, vol. 1. Development, nutrition and reproduction Chapman & Hall, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Collins CM, Bonds JAS, Quinlan MM, and Mumford JD. 2019. Effects of the removal or reduction in density of the malaria mosquito, Anopheles gambiae s.l., on interacting predators and competitors in local ecosystems. Med. Vet. Entomol 33: 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dambach P, Baernighausen T, Traoré I, Ouedraogo S, Sié A, Sauerborn R, Becker N, and Louis VR. 2019. Reduction of malaria vector mosquitoes in a large-scale intervention trial in rural Burkina Faso using Bti based larval source management. Malar. J 18: 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dambach P, Schleicher M, Stahl HC, Traoré I, Becker N, Kaiser A, Sié A, and Sauerborn R. 2016. Routine implementation costs of larviciding with Bacillus thuringiensis israelensis against malaria vectors in a district in rural Burkina Faso. Malar. J 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dida GO, Anyona DN, Abuom PO, Akoko D, Adoka SO, Matano AS, Owuor PO, and Ouma C. 2018. Spatial distribution and habitat characterization of mosquito species during the dry season along the Mara River and its tributaries, in Kenya and Tanzania. Infect. Dis. Poverty 7: 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dida GO, Gelder FB, Anyona DN, Abuom PO, Onyuka JO, Matano AS, Adoka SO, Kanangire CK, Owuor PO, Ouma C, and Ofulla AVO. 2015. Presence and distribution of mosquito larvae predators and factors influencing their abundance along the Mara River, Kenya and Tanzania. Springerplus 4: 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emidi B, Kisinza WN, Mmbando BP, Malima R, and Mosha FW. 2017. Effect of physicochemical parameters on Anopheles and Culex mosquito larvae abundance in different breeding sites in a rural setting of Muheza, Tanzania. Parasit. Vectors 10: 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fillinger U, Ndenga B, Githeko A, and Lindsay SW. 2009. Integrated malaria vector control with microbial larvicides and insecticide-treated nets in western Kenya: A controlled trial. Bull. Wld. Hlth. Org 87: 655–665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fillinger U, Sombroek H, Majambere S, Van Loon E, Takken W, and Lindsay SW. 2009. Identifying the most productive breeding sites for malaria mosquitoes in the Gambia. Malar. J 8: 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbreath TM, Kweka EJ, Afrane YA, Githeko AK, and Yan G. 2013. Evaluating larval mosquito resource partitioning in western Kenya using stable isotopes of carbon and nitrogen. Parasit. Vectors 6: 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillies MT, and Coetzee M. 1987. A Supplement to the Anophelinae of Africa South of the Sahara. Publ. South African Inst. Med. Res 55: 63. [Google Scholar]

- Gimnig JE, Ombok M, Kamau L, and Hawley WA. 2001. Characteristics of larval anopheline (Diptera: Culicidae) habitats in western Kenya. J. Med. Entomol 38: 282–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartung C, Anokwa Y, Brunette W, Lerer A, Tseng C, and Borriello G. 2010. Open data kit: Tools to build information services for developing regions. In ACM Int. Conf. Proceeding Ser. 1–12.

- Huang J, Walker ED, Otienoburu PE, Amimo F, Vulule J, and Miller JR. 2006. Laboratory tests of oviposition by the African malaria mosquito, Anopheles gambiae, on dark soil as influenced by presence or absence of vegetation. Malar. J 5: 2008–2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Impoinvil DE, Keating J, Mbogo CM, Potts MD, Chowdhury RR, and Beier JC. 2008. Abundance of immature Anopheles and culicines (Diptera: Culicidae) in different water body types in the urban environment of Malindi, Kenya. J. Vector Ecol 33: 107–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshua MK, Ngongondo C, Chipungu F, Monjerezi M, Liwenga E, Majule A, Stathers T, and Lamboll R. 2016. Climate change in semi-arid Malawi: Perceptions, adaptation strategies and water governance. Jàmbá J. Disaster Risk Stud 8: 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabaghe AN, Chipeta MG, Gowelo S, Mburu M, Truwah Z, McCann RS, Van Vugt M, Grobusch MP, and Phiri KS. 2018. Fine-scale spatial and temporal variation of clinical malaria incidence and associated factors in children in rural Malawi: A longitudinal study. Parasites and Vectors 11: 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koekemoer LL, Kamau L, Hunt RH, and Coetzee M. 2002. A cocktail polymerase chain reaction assay to identify members of the Anopheles funestus (Diptera: Culicidae) group. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg 66: 804–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenraadt CJM, Githeko AK, and Takken W. 2004. The effects of rainfall and evapotranspiration on the temporal dynamics of Anopheles gambiae s.s. and Anopheles arabiensis in a Kenyan village. Acta Trop 90: 141–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kundu M, Sharma D, Brahma S, and Pramanik S. 2014. Insect predators of mosquitoes of rice fields : portrayal of indirect interactions with alternative. J. Entomol. Zool. Stud 2: 97–103. [Google Scholar]

- Kweka EJ, Zhou G, Beilhe LB, Dixit A, Afrane Y, Gilbreath TM, Munga S, Nyindo M, Githeko AK, and Yan G. 2012. Effects of co-habitation between Anopheles gambiae s.s. and Culex quinquefasciatus aquatic stages on life history traits. Parasit. Vectors 5:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kweka EJ, Zhou G, Gilbreath TM, Afrane Y, Nyindo M, Githeko AK, and Yan G. 2011. Predation efficiency of Anopheles gambiae larvae by aquatic predators in western Kenya highlands. Parasit. Vectors 4:128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mala AO, and Irungu LW. 2011. Factors influencing differential larval habitat productivity of Anopheles gambiae complex mosquitoes in a western Kenyan village. J. Vector Borne Dis 48:52–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mburu MM, Mzilahowa T, Amoah B, Chifundo D, Phiri KS, van den Berg H, Takken W, and McCann RS. 2019. Biting patterns of malaria vectors of the lower Shire valley, southern Malawi. Acta Trop 197: 105030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mburu MM, Zembere K, Hiscox A, Banda J, Phiri KS, Van Den Berg H, Mzilahowa T, Takken W, and McCann RS. 2019. Assessment of the Suna trap for sampling mosquitoes indoors and outdoors. Malar. J 18:51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCann RS, van den Berg H, Diggle PJ, van Vugt M, Terlouw DJ, Phiri KS, Di Pasquale A, Maire N, Gowelo S, Mburu MM, Kabaghe AN, Mzilahowa T, Chipeta MG, and Takken W. 2017. Assessment of the effect of larval source management and house improvement on malaria transmission when added to standard malaria control strategies in southern Malawi: Study protocol for a cluster-randomised controlled trial. BMC Infect. Dis 17:639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mereta ST, Yewhalaw D, Boets P, Ahmed A, Duchateau L, Speybroeck N, Vanwambeke SO, Legesse W, De Meester L, and Goethals PL. 2013. Physico-Chemical and biological characterization of anopheline mosquito larval habitats Diptera: Culicidae: Implications for malaria control. Parasit. Vectors 6: 1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minakawa N, Munga S, Atieli F, Mushinzimana E, Zhou G, Githeko AK, and Yan G. 2005. Spatial distribution of anopheline larval habitats in Western Kenyan highlands: Effects of land cover types and topography. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg 73: 157–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minakawa N, Sonye G, Mogi M, and Yan G. 2004. Habitat characteristics of Anopheles gambiae s.s. larvae in a Kenyan highland. Med. Vet. Entomol 18: 301–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minakawa N, Sonye G, and Yan G. 2005. Relationships between occurrence of Anopheles gambiae s.l. (Diptera: Culicidae) and size and stability of larval habitats. J. Med. Entomol 42: 295–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munga S, Minakawa N, Zhou G, Barrack O-OJ, Githeko AK, and Yan G. 2006. Effects of larval competitors and predators on oviposition site selection of Anopheles gambiae sensu stricto. J. Med. Entomol 43: 221–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutuku FM, Bayoh MN, Gimnig JE, Vulule JM, Kamau L, Walker ED, Kabiru E, and Hawley WA. 2006. Pupal habitat productivity of Anopheles gambiae complex mosquitoes in a rural village in western Kenya. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg 74: 54–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muturi EJ, Mwangangi J, Shililu J, Jacob BG, Mbogo C, Githure J, and Novak RJ. 2008. Environmental factors associated with the distribution of Anopheles arabiensis and Culex quinquefasciatus in a rice agro-ecosystem in Mwea, Kenya. J. Vector Ecol 33: 56–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mwangangi JM, Mbogo CM, Muturi EJ, Nzovu JG, Githure JI, Yan G, Minakawa N, Novak R, and Beier JC. 2007. Spatial distribution and habitat characterisation of Anopheles larvae along the Kenyan coast. J. Vector Borne Dis 44: 44–51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mwingira VS, Spitzen J, Mboera LEG, Torres-estrada JL, and Takken W. 2020. The Influence of Larval Stage and Density on Oviposition Site-Selection Behavior of the Afrotropical Malaria Mosquito Anopheles coluzzii ( Diptera : Culicidae ). J. Med. Entomol 57: 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mzilahowa T, Hastings IM, Molyneux ME, and McCall PJ. 2012. Entomological indices of malaria transmission in Chikhwawa district, Southern Malawi. Malar. J 11: 1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nayar JK, Knight JW, Ali A, Carlson DB, and O’Bryan PD. 1999. Laboratory evaluation of biotic and abiotic factors that may influence larvicidal activity of Bacillus thuringiensis serovar. israelensis against two Florida mosquito species. J. Am. Mosq. Control Assoc 15: 32–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ndenga BA, Simbauni JA, Mbugi JP, Githeko AK, and Fillinger U. 2011. Productivity of malaria vectors from different habitat types in the western kenya highlands. PLoS One 6:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohba S-Y, Kawada H, Dida GO, Juma D, Sonye G, Minakawa N, and Takagi M. 2010. Predators of Anopheles gambiae sensu lato (Diptera: Culicidae) larvae in wetlands, western Kenya: confirmation by polymerase chain reaction method. J. Med. Entomol 47: 783–787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paaijmans KP, Takken W, Githeko AK, and Jacobs AFG. 2008. The effect of water turbidity on the near-surface water temperature of larval habitats of the malaria mosquito Anopheles gambiae. Int. J. Biometeorol 52: 747–753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts D 2014. Mosquito larvae change their feeding behavior in response to kairomones from some predators. J. Med. Entomol 51: 368–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sattler MA, Mtasiwa D, Kiama M, Premji Z, Tanner M, Killeen GF, and Lengeler C. 2005. Habitat characterization and spatial distribution of Anopheles sp. mosquito larvae in Dar es Salaam (Tanzania) during an extended dry period. Malar. J 4: 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott JA, Brogdon WG, and Collins FH. 1993. Identification of single specimens of the Anopheles gambiae complex by the polymerase chain reaction. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg 49: 520–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Service MW 1993. Mosquito Ecology. Field Sampling Methods, Elsevier Appl. Sci. London. [Google Scholar]

- Shaalan EAS, and Canyon DV. 2009. Aquatic insect predators and mosquito control. Trop. Biomed 26: 223–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silberbush A, and Blaustein L. 2018. Oviposition habitat selection by a mosquito in response to a predator: Are predator-released kairomones air-borne cues? J. Vector Ecol 33: 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivagnaname N 2009. A novel method of controlling a dengue mosquito vector, Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) using an aquatic mosquito predator, Diplonychus indicus (Hemiptera: Belostomatidae) in tyres. Dengue Bull 33: 148–160. [Google Scholar]

- Stein M, Ludueña-Almeida F, Willener JA, and Ricardo Almirón W. 2011. Classification of immature mosquito species according to characteristics of the larval habitat in the subtropical province of Chaco, Argentina. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 106: 400–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumba LA, Okoth K, Deng AL, Githure J, Knols BGJ, Beier JC, and Hassanali A. 2004. Daily oviposition patterns of the African malaria mosquito Anopheles gambiae Giles (Diptera: Culicidae) on different types of aqueous substrates. J. Circadian Rhythms 2: 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunahara T, Ishizaka K, and Mogi M. 2002. Habitat size: a factor determining the opportunity for encounters between mosquito larvae and aquatic predators. J. Vector Ecol 27: 8–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tusting LS, Thwing J, Sinclair D, Fillinger U, Gimnig J, Bonner KE, Bottomley C, and Lindsay SW. 2013. Mosquito larval source management for controlling malaria. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev 8: CD008923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Udayanga L, Ranathunge T, Iqbal MCM, Abeyewickreme W, and Hapugoda M. 2019. Predatory efficacy of five locally available copepods on Aedes larvae under laboratory settings: An approach towards bio-control of dengue in Sri Lanka. PLoS One 14: 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Wamae PM, Githeko AK, Menya DM, and Takken W. 2010. Shading by Napier grass reduces malaria vector larvae in natural habitats in Western Kenya highlands. Ecohealth 7: 485–497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO. 2013. Larval source management: A supplementary measure for malaria control: An operational manual. Geneva, World Hlth. Org 25: 41–43. [Google Scholar]

- Wikum DA, and Shanholtzer GF. 1978. Application of the Braun-Blanquet cover-abundance scale for vegetation analysis in land development studies. Environ. Manage 2: 323–329. [Google Scholar]

- Ye-Ebiyo Y, Pollack RJ, Kiszewski A, and Spielman A. 2003. Enhancement of development of larval Anopheles arabiensis by proximity to flowering maize (Zea mays) in turbid water and when crowded. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg 68: 748–752. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.