The alarming spread of the SARS-CoV-2 virus makes it necessary to find the right measures to prevent and combat the coronavirus disease (COVID)-19 pandemic.1 Researchers have identified angiotensin converting enzyme II (ACE2) as the likely receptor with which SARS-CoV-2 infects human cells.2,3 Recent findings suggest that ACE2 is highly expressed in the oral cavity3 and detectable virus concentrations were found in saliva.4,5 Hence, the virus may predominantly enter the body via the oral mucosa. Gum disease (periodontitis) is known to cause ulceration of the gingival epithelium and weaken the protective function of the buccal mucosa. It can be postulated that this exposed ulcerated surface increases the risk of invasion by SARS-CoV-2.

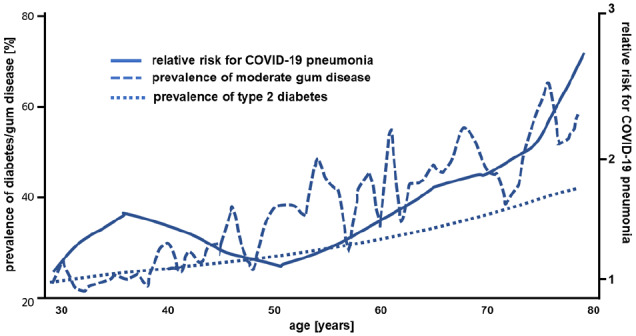

The current population-based analyses of the severe COVID-19 courses in China6 show a clear correlation with higher age, which is similar to the correlation between age and the prevalence of periodontitis, and also similar to the well-known correlation between age and diabetes prevalence (Figure 1).7,8 A further indication is the current COVID-19 mortality statistics in which European countries without regular and state-supported oral hygiene consultations and treatments (such as Belgium, Italy, and Spain), with comparable infrastructure and living standards, have significantly higher mortality rates per one million inhabitants (state on April 2, 2020: 606, 490, and 436, respectively) than countries with well-established oral hygiene programs (such as Germany: 71, Austria: 61, or Norway: 389).

Figure 1.

Association between age, prevalence of moderate gum disease, risk for COVID-19 disease, and prevalence of diabetes (modified from Sun et al.,6 Thornton-Evans et al.,7 and Cheng et al.8).

Diabetes is a risk factor for gum disease and it is necessary to pay attention to possible oral complications in the early stages. The International Federation of Diabetes (IDF)10 recommends that regular diabetes screenings should be supplemented by an annual oral cavity assessment for gum disease, including bleeding while brushing or inspection for swelling. Hyperglycemia causes damage to the connective tissue in the oral cavity with reduced synthesis of gum fibroblasts, resulting in the loss of periodontal fibers and alveolar bone.11 In addition, impairment of the phagocytic activity of mononuclear and polymorphonuclear cells has been observed, leading to the development of aggressive pathogenic subgingival flora. Periodontal infection can therefore induce systemic inflammation, which in turn builds up or reinforces chronic insulin resistance. A vicious circle of hyperglycemia, periodontitis and connective tissue degradation, inflammation (oral and systemic), and insulin resistance develops, which is virtually uncontrollable for all disorders without effective intervention.11

A recently published long-term study provided impressive evidence for the value of oral care in the primary prevention of pneumonia in people with diabetes. The investigators analyzed this association in 98 800 people in Taiwan over a period of 12 years. The authors concluded that patients who received intensive periodontal treatment had an average 66% lower risk of pneumonia. Patients with diabetes had a 78% increased risk of developing pneumonia compared to the control group.12 These findings indicate that the multimorbid patient with diabetes and periodontitis as a comorbidity has a frighteningly high risk of pneumonia even without SARS-CoV-2 infection.

The association between diabetes and increased COVID-19 mortality may be related to the aspects described above but also to additional systemic effects of periodontitis. Periodontal disease affects blood sugar levels and impairs the innate immune system. Periodontitis also increases systemic inflammation, as host-derived mediators of periodontal disease and tissue destruction (eg, cytokines and metalloproteinases) are released from the inflamed periodontal tissue into the circulatory system.13 It is known that patients with diabetes have an increased risk of mortality from concomitant oral diseases, while patients with periodontitis have a demonstrably higher risk of diabetes.14 In this context, biomarkers such as activated matrix metalloproteinase 8 (available as a laboratory or saliva rapid test) offer the possibility of identifying patients at risk for diabetes and thus making it accessible for targeted prevention.15,16

A well-functioning gingival epithelial barrier can help to prevent pathogenic viruses and bacteria in the oral cavity from entering the bloodstream. This means that regular daily tooth brushing with additional application of disinfectant mouthwash up to the posterior pharynx, especially in patients with diabetes, could potentially help to reduce the potential systemic consequences of a SARS-CoV-2 virus infections. The dentist and the diabetes specialist should advise patients with diabetes to have regular check-ups and dental hygiene treatments.17,18 This targeted prevention strategy, with additional recommendations for monitoring and maintaining oral health, can be a quick and simple approach to protection against the current coronavirus pandemic. COVID-19 does not stop at borders; it is a global challenge, and solutions to this pandemic will require an interdisciplinary alliance of experts in all fields, including dentistry, periodontology, and diabetology.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Andreas Pfützner  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2385-0887

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2385-0887

References

- 1. The Lancet. COVID-19: too little, too late? Lancet. 2020;395:755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zhou P, Yang XL, Wang XG, et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579:270-273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Xu H, Zhong L, Deng J, et al. High expression of ACE2 receptor of 2019-nCoV on the epithelial cells of oral mucosa. Int J Oral Sci. 2020;12:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chen L, Zhao J, Peng J, et al. Detection of 2019-nCoV in saliva and characterization of oral symptoms in COVID-19 patients [published online ahead of print March 19, 2020]. SSRN. Available at: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3557140

- 5. To KKW, Tsang OTY, Yip CCY, et al. Consistent detection of 2019 novel coronavirus in saliva [published online ahead of print February 12, 2020]. Clin Infect Dis. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa149 Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7108139/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6. Sun K, Chen J, Viboud C. Early epidemiological analysis of the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak based on crowdsourced data: a population-level observational study Lancet Digital Health. 2020;2:e201-e208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Thornton-Evans G, Eke P, Wie L, et al. Periodontitis among adults aged ≥30 years — United States, 2009–2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62:129-135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cheng YJ, Imperatore G, Geiss LS, et al. Secular changes in the age-specific prevalence of diabetes among U.S. adults: 1988–2010. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:2690-2696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Statista. Coronavirus (COVID-19) deaths worldwide per one million population as of April 26, 2020, by country. Available at https://www.statista.com/statistics/1104709/coronavirus-deaths-worldwide-per-million-inhabitants/

- 10. Skamagas M, Breen TL, LeRoith D. Update on diabetes mellitus: prevention, treatment, and association with oral diseases. Oral Dis. 2008;14:105-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Janket SJ, Jones JA, Meurman JH, Baird AE, Van Dyke TE. Oral infection, hyperglycemia, and endothelial dysfunction. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2008; 105:173-179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yang LC, Suen YJ, Wang YH, Lin TC, Yu HC, Chang YC. The association of periodontal treatment and decreased pneumonia: a nationwide population-based cohort study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:3356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hajishengallis G. Periodontitis: from microbial immune subversion to systemic inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15:30-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sanz M, Ceriello A, Buysschaert M, et al. Scientific evidence on the links between periodontal diseases and diabetes: consensus report and guidelines of the joint workshop on periodontal diseases and diabetes by the International diabetes Federation and the European Federation of Periodontology. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2018;137:231-241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sorsa T, Alassiri S, Grigoriadis A, et al. Active MMP-8 (aMMP-8) as a grading and staging biomarker in the periodontitis classification. Diagnostics (Basel). 2020;10:E61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Grigoriadis A, Sorsa T, Räisänen I, Pärnänen P, Tervahartiala T, Sakellari D. Prediabetes/diabetes can be screened at the dental office by a low-cost and fast chair-side/point-of-care aMMP-8 Immunotest. Diagnostics (Basel) 2019;9:E151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chi AC, Neville BW, Krayer JW, Gonsalves WC. Oral manifestations of systemic disease. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82:1381-1388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kiran M, Arpak N, Unsal E, Erdoǧan MF. The effect of improved periodontal health on metabolic control in type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Clin Periodontol. 2005;32:266-272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]