Abstract

Degradable embolic agents that provide transient arterial occlusion during embolization procedures have been of interest for many years. Ideally, embolic agents are visible with standard imaging modalities and offer on-demand degradability, permitting physicians to achieve desired arterial occlusion tailored to patient and procedure indication. Subsequent arterial recanalization potentially enhances the overall safety and efficacy of embolization procedures. Here, we report on-demand degradable and MRI-visible microspheres for embolotherapy. Embolic microspheres composed of calcium alginate and USPIO nanoclusters were synthesized with an air spray atomization and coagulation reservoir equipped with a vacuum suction. An optimized distance between spray nozzle and reservoir allowed uniform size and narrow size distribution of microspheres. The fabricated alginate embolic microspheres crosslinked with Ca2+ demonstrated highly responsive on-demand degradation properties in vitro and in vivo. Finally, the feasibility of using the microspheres for clinical embolization and recanalization procedures was evaluated with interventional radiologists in rabbits. Digital subtraction angiography (DSA) guided embolization of hepatic arteries with these embolic microspheres was successfully performed and the occlusion of artery was confirmed with DSA images and contrast enhanced MRI. T2 MRI visibility of the microspheres allowed to monitor the distribution of intra-arterial (IA) infused embolic microspheres. Subsequent on-demand image-guided recanalization procedures were also successfully performed with rapid degradation of microspheres upon intra-arterial infusion of an ion chelating agent. These instant degradable embolic microspheres will permit effective on-demand embolization/recanalization procedures offering great promise to overcome limitations of currently available permanent and biodegradable embolic agents.

Keywords: Embolic agents, On-demand degradable microspheres, Embolization, Interventional radiology, Embolotherapy

1. Introduction

A cornerstone of vascular intervention is embolotherapy, where blood flow to targeted vessels is blocked to decrease tissue perfusion, treat tumors, and stop hemorrhage. Embolization is widely adopted for the treatment of cancers, aneurysms, uterine fibroids, trauma, and gastrointestinal hemorrhage [1–8]. One of the main clinical embolo-therapies is trans-arterial embolization (TAE) of tumors such as hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [4], renal cell carcinoma (RCC) [5], and neuroendocrine tumors (NET) [6]. Transcatheter arterial embolization (TAE) involves selectively blocking the blood supply to tumor tissues and has been proposed as an alternative or adjunct to surgical resection. A wide variety of permanent embolic agents in the form of polymers, microspheres and micro-coils are delivered to the target artery through an image-guided arterial microcatheter. The choice of embolic agent is predicated on the goals of therapy and the duration and degree of occlusion required.

Permanent embolic agents have several limitations including slow or incomplete thrombus formation and off target damage [9–11]. Furthermore, permanent embolization agents can induce severe hypoxic conditions and enhance hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) serum level which play a major role in tumor progression [12]. Due to these drawbacks, temporary degradable embolics may be a desirable alternative to provide more precise, controlled therapeutic benefit. Autologous blood clots, porcine collagen-based sponge (SURGIFOAM®, Johnson & Johnson, NJ, USA)/porcine gelatin microspheres (Optispheres, Medtronic, MN, USA) and powder GelFoam (Upjohn, Kalamazoo, MI, USA) have been used as temporary embolic agents. However, the degree of occlusion and subsequent degradation are currently not controllable; current platforms lack the temporal precision required for efficient temporary occlusion [13,14]. As degradable embolic agents shrink in size, they may potentially advance beyond the intended level of occlusion resulting in more profound ischemia and necrosis and/or, reflux into adjacent vessels, resulting in non-target embolization and/or travel through capillaries (i.e., shunting) leading to unintended injury of downstream organs such as the lungs or brain. Development of a new class of embolic agents permitting on-demand degradation should significantly enhance the overall efficacy of embolotherapies. An additional consideration includes visibility during medical imaging and represents a critical design consideration for any new class of embolic agent. With increasing availability of combined X-ray DSA-MRI procedure suites, it is now possible to use DSA and MRI to guide catheter placement and MRI as complimentary modality to monitor the delivery of contrast tracers and therapeutic vectors to targeted regions. Incorporation MRI visible microspheres may lead to more accurate spatial localization of microspheres [15]. An understanding of the temporal and spatial distribution of embolic agents would be clinically beneficial. On-demand degradable temporary embolic agents with imaging visibility offers the potential to enhance therapeutic outcomes for a multitude of embolotherapies.

Here, we describe development of on-demand degradable alginate-based embolic microspheres and evaluate on-demand embolization/recanalization procedures using the fabricated embolic microspheres with interventional radiologists. Natural polysaccharides alginate originated from brown seaweed have been used for a variety of biomedical applications such as cell encapsulation [16], surgical sponges [17], and wound dressings [18] due to its biocompatibility and biodegradability [19]. It can be used as an on-demand degradable embolic agent; an alginate gel crosslinked with cation ions can be dissolved by removing the crosslinking ions [20], and the backbone also can be degraded via hydrolysis of the glycosidic bonds [21]. To fabricate on-demand degradable and MRI visible alginate based embolic microspheres in a controlled manner, spray-atomized microdroplets from a solution including alginate and ultra-small superparamagnetic iron oxide (USPIO) clusters were generated and coagulated in CaCl2 reservoir equipped with vacuum suction, as shown in Fig. 1a. The size and morphology of spray-coagulated alginate based embolic agents was optimized by adjusting the distance between nozzle and reservoir. Then, on-demand instant degradation properties of the fabricated embolic microspheres was investigated in vitro and during in vivo studies in mice micro-vessels with EDTA (ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid) ion-chelating agent which has been frequently used for other medical applications [22–24]. Finally, in vivo transcatheter intra-arterial (IA) embolization and on-demand instant recanalization of the embolic microspheres were demonstrated with fluoroscopy-guided transcatheter infusion procedures and MRI T2 imaging in rabbit animal models with interventional radiologists.

Fig. 1.

(a) Schematic illustration of air atomizing spray-coagulation set-up for fabricating Alg-USPIO microspheres, (b) A spray-pattern image taken with a planar red laser (650 nm). The prepared alginate solution was sprayed using a compressed air (20 psi)-assisted spray equipment. The spray pattern showed two divided regions of air-pressure-driven-atomization and turbulence. (c) Morphology of microspheres fabricated by the spray-coagulation in different distance of the nozzle-to-reservoir (white bar represents 50 μm). (d) A table for mean size and size distribution of fabricated microspheres in various condition.

2. Experimental section

2.1. Materials

Sodium alginate (MW 10,111), agarose, calcium chloride (CaCl2), diethylene glycol (DEG), n-hexadecane, phosphate buffer saline tablets (PBS, pH 7.4), polyacrylic acid (PAA), polyvinyl alcohol (PVA, MW 13,000–23,000), and sodium hydroxide were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA). Ferric chloride (FeCl3) was purchased from EMD. Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) solution was purchased from G-Biosciences (St Louis, MO, USA). Calcium chloride, PBS and PVA were dissolved into Milli-Q grade water and filtered for further use. Other reagents and materials were used for further experiments without purification.

2.2. Synthesis of USPIO clusters

41 nm USPIO clusters were synthesized with a high temperature hydrolysis reaction, as previously reported (Fig. S1) [25,26]. Briefly, a solution of NaOH (2 g) and DEG (20 ml) was prepared at 120 °C for 30 min under nitrogen atmosphere and kept at 70 °C. Next, a mixture of FeCl3 (65.7 mg), PAA (288 mg), and DEG (17 ml) was prepared at 220 °C for 30 min 2 ml of NaOH (2 g) and DEG (20 ml) was added into the second solution and incubated for 1 h more. After finishing the reaction, the reaction mixture was washed with the ethanol-water solution for 3 times. The sample were centrifugated at 3500 rpm for 15 min, and the supernatant was removed. Milli-Q water was added onto the USPIO clusters to re-disperse, and the solution was stored at room temperature before use. The morphology of USPIO clusters was determined by TEM (Tecnai Spirit G2, 120 kV, FEI), and the hydrodynamic size and the ζ-potential of USPIO clusters were characterized by DLS analysis (Zetasizer Nano ZSP, Malvern Instruments Ltd., Grovewood Road, Malvern, UK).

2.3. Spraying-coagulation fabrication of on-demand degradable microspheres

Gravity-fed high-volume low pressure (HVLP) air spraying gun (PNTgreen H2001, Ningbo Lis Industrial Co., Ltd., China.) with an 0.8 mm-sized nozzle was used for generation of microdroplets. An alginate solution (1 w/v % or 2 w/v% sodium alginate) was loaded in the sample-container of the spray. For the fabrication of magnetic alginate microspheres (Alg-USPIO), a solution was prepared by mixing USPIO clusters and alginate solution (weight ratio: 1:20 at USPIO:alginate). Compressed air with 20 psi was used to spray the solution onto 0.5 M CaCl2 reservoir equipped with a vacuum suction tube device made of customized perforated polyethylene tube connected to vacuum pump (11 psi) on the entry of the reservoir. The distance from the nozzle orifice to surface of reservoir was varied from 20 to 60 cm for optimizing spraying conditions.

2.4. Spray pattern imaging

Images of the pattern of sprayed solution was captured with two-dimensional planar laser and digital camera (RX-100, Sony, Japan). The obtained images from Milli-Q water and alginate solution were further processed with threshold function by ImageJ.

2.5. Characterization

Zero-shear viscosity of alginate solution in various concentration (0.25, 0.5, 1, 2 w/v%) was measured using rheometer (MCR 302, Anton Parr, Austria). The mean size and size distribution of microspheres with or without vacuum suction were analyzed with optical microscope (Olympus, Japan) and Image J program (NIH, USA). Approximately 200 microspheres were randomly counted in microscopic images for measuring mean size and distribution, and the statistical significance of parameters was evaluated by one-way ANOVA by distances, respectively. The mechanical properties of compressibility of embolic microspheres was measured as previously reported [27]. Compressibility of conventional embolic microspheres (LC Beads®) and Alg-USPIO microspheres in hydrated condition was compared by the compressibility index (CI) equation: CI = 1-Vf/Vi, where Vf represents the volume after compression and Vi represents the initial volume.

2.6. In vitro on-demand degradation of Alg-USPIO microspheres

On-demand degradation tests of embolic microspheres were performed to investigate the triggered degradation of Alg-USPIO microspheres by calcium ion chelation under EDTA. 10 μL of suspensions of Alg-USPIO microspheres (2 mg/ml) in Milli-Q grade water or blood serum were placed onto a glass slide, and 10 μL of EDTA solution (1, 5, 10, 30 mM) was injected from the side. The time points for complete degradation of microspheres under EDTA solution (1, 5, 10, 30 mM) were measured by time-lapse recordings at each second with optical microscopy. The obtained images were analyzed to determine the complete degradation time point showing no Alg-USPIO microspheres larger than 1 μm diameter. The blood serum was obtained by separation with centrifugation at 2000 rpm for 10 min from whole blood of mice. For in vitro embolization study, microhematocrit capillary tubes (Fisherbrand™, Fisher Scientific, MA, USA) with 0.11–0.12 cm diameter were elongated by application of heat to generate a fine capillary with diameter smaller than 20 μm. 50 μg of Alg-USPIO microspheres were loaded into the capillary, and 5 μL of 30 mM EDTA was injected. Images of microspheres were obtained during the test by optical microscope. The solution passed through the capillary during the on-demand degradation test was collected in centrifuge tubes and imaged by optical microscope. The measurement of size of degradation product was performed with DLS analysis (Zetasizer Nano ZSP, Malvern Instruments Ltd., Grovewood Road, Malvern, UK) after the reaction between equivalent volume of calcium alginate microspheres (0.5 mg/ml) and EDTA (30 mM) for 2 h.

2.7. MRI T2 contrast effect in phantoms

The samples for agarose MRI phantom were prepared by the following steps: Alg-USPIO microspheres were dispersed into 1% agarose solution at 70 °C. Next, the suspension was vortexed for 2 s. Then, the suspension was stored in −20 °C freezer. The MR phantom images were obtained using a Bruker 7.0 T ClinScan (Bruker BioSpin, Ettlingen, Germany).

2.8. Cell viability test

The cell viability of Clone-9 normal liver cell line was quantified by CCK-8 assay kit (Dojindo Inc., Rockville, MD, USA). For the cell viability test of USPIO clusters, a total of 1 × 104 cells was incubated in 100 μl of complete media with 96-well plate. After overnight incubation, culture media was replaced by 100 μl of media containing 0–2 mg/ml USPIO clusters, and the cells were incubated for 48 h. Then, 10 μl of CCK-8 reagents was treated and incubated for 4 h, and the absorbance of each well was quantified by spectrophotometer (BioTek Inc., Crawfordsville, IN, USA) at 450 nm. For cell viability evaluation of degradation product from Alg-USPIO microspheres after treatment of EDTA, 1 × 104 cells were placed in 90 μl of complete media in each well of 96-well culture plate and incubated overnight. 10 μl of samples containing degradation product (Alg-USPIO microspheres (0.5 mg/ml) and EDTA (0–30 mM)) was treated to the cells, and the cells were incubated for 24 h. Then, 10 μl of CCK-8 reagents was added and incubated for 4 h, and the absorbance was measured by spectrophotometer (BioTek Inc., Crawfordsville, IN, USA) at 450 nm.

2.9. In vivo evaluation of on-demand degradation of Alg-USPIO microspheres in mouse model

All experiments were approved by our Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). Six C57/BL6 mice were used in this experiment. 30 μL of 2 mg/mL Alg-USPIO microspheres were infused in subcutaneous micro-vessels to embolize the blood vessels downstream of injection point. After 3 min of the embolization, 100 μL of 30 mM of EDTA solution was infused to degrade the embolic microspheres. During the procedure, images of blood vessels were obtained to determine the on-demand degradation of embolic microspheres.

2.10. In vivo transcatheter hepatic intra-arterial embolization and on-demand degradation of Alg-USPIO microspheres in rabbit model

All experiments were approved by our Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). Five female New Zealand white rabbits weighing 4 kg in average were used in this experiment. The rabbit was anesthetized and catheterized (via the femoral artery) with X-ray fluoroscopic guidance by using a C-arm unit (PowerMobil; Siemens Medical Solutions, Erlangen, Germany). A 3-F vascular sheath was placed, and a 2-F catheter was subsequently introduced via this sheath. The 2-F catheter was advanced into celiac artery, proper hepatic artery (PHA), and left hepatic artery (LHA) with a 0.014-inch-diameter guidewire. Alg-USPIO microspheres were infused with the catheter tip positioned immediately proximal to the PHA bifurcation into the RHA and LHA. At 3 min post-embolization, 30 mM EDTA was delivered to the RHA alone through the catheter while LHA remained occluded. All procedures were imaged by conventional digital subtraction angiography (DSA) at predetermined time points. For the MRI studies, the LHA was occluded by the Alg-USPIO microspheres with the same strategy described above. Next, after observation of the embolization was determined by 1.5-T Area MRI scanner (Siemens Medical Solutions, Erlangen, Germany), 30 mM EDTA solution was infused into LHA. The rabbit was placed in MRI scanner and scanned continuously up to 1 h to determine the recanalization of the left hepatic artery. For obtaining T1 weighted MR with gadolinium contrast (Magnevist®, Bayer, Germany), the same catheter described above was advanced into the PHA, and both Alg- USPIO microspheres and 30 mM EDTA solution were infused with catheter into the PHA sequentially. MR images were obtained before treatment with Alg-USPIO microspheres, after embolization, and after infusion of the EDTA solution.

2.11. Histology (H&E and Prussian blue staining)

After the on-demand degradation of microspheres procedures, liver samples were dissected, and placed in a bottle containing 5% formalin solution for histological examination. Hematoxylin and eosin staining (H&E) and Prussian blue staining were performed to identify residual microspheres after the degradation. The obtained tissue sections were imaged with an optical microscope. The tissue images were compared with tissue images from control group treated IA infusion of PBS.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Preparation of on-demand degradable and MRI visible embolic microspheres by spray atomization-coagulation method

On-demand degradable and MRI visible embolic microspheres were prepared by spray atomization-coagulation method. Emulsion method is the most common to fabricate embolic microspheres [28]. However, the usage of organic solvents requires extensive purification processes [29] and the size distribution of fabricated microspheres are relatively wide leading to low reproducibility [30]. Air-assisted spray technique with tight control of factors responsible for the size and distribution may overcome these issues in the fabrication of alginate based embolic microspheres.

The morphology of fabricated microspheres is directly dependent on the spray-atomized microdroplets [31]. A 1 %w/v or 2 %w/v alginate solution was sprayed, and the coagulated microspheres with 0.5 M calcium chloride solution reservoir were characterized. The spray pattern image taken with a planar laser (650 nm) showed two divided regions of air-pressure-driven-atomization and turbulence (Fig. 1b). The size and shape of fabricated microspheres in those two regions were significantly different (Fig. 1c). When the coagulation reservoir was located within the air-pressure-driven-atomization region (20–40 cm distance from the nozzle), the spherical shaped microspheres was generated (Fig. 1c). When the coagulation reservoir was located in the turbulence region (>40 cm distance from nozzle) where atomized droplets collide and coalesce, the size distribution was significantly high and irregular shaped microspheres were observed (Fig. 1c). As the distance from the reservoir to the nozzle increased within the region of air pressure driven atomization, the size and size distribution of microspheres was decreased (Fig. 1d). When the air pressure is increased in a range of 10–20 psi, the size of microspheres was decreased at each nozzle-to-reservoir distance setup of 20–50 cm. However, too great of pressure (>20 psi) generated irregular-shaped particles with a high impact on the spray-atomized micro-droplets at the interface with CaCl2 solution. Increased concentration of alginate solution (2 %w/v) having a higher viscosity compared to 1% w/v alginate solution also decreased the size of microspheres in the same other conditions of spray-coagulation process (Fig. 1d and Fig. S2).

Taking these considerations into account, about 30 μm alginate embolic microsphere embedded with USPIO nanoclusters (Alg-USPIO microspheres) could be fabricated at 30 cm distance of the nozzle to coagulation reservoir equipped with a custom-designed vacuum suction jacket (Fig. 2a). A stable precursor solution was prepared by mixing of a synthesized superparamagnetic iron oxide (USPIO) nanocluster [32,33] and 2% alginate solution. The prepared USPIO nanoclusters-alginate solution was then sprayed using compressed air (20 psi)-assisted spray equipment. With the addition of multi-anionic USPIO clusters (5 wt%), the size of coagulated microspheres with Ca2+ were smaller than alginate microspheres without USPIO clusters. The application of vacuum suction successfully allowed a significant decrease in the size distribution of microspheres. The size distribution of microspheres fabricated with a vacuum suction was 10.4 μm which was significantly lower than 19.2 μm in a condition without the suction jacket (p < 0.01) (Fig. S3). Incorporation of USPIO clusters in alginate microspheres provided T2 MRI visibility of the microspheres (Fig. S4). The MRI visibility of microspheres would assist in post-infusion monitoring of outcome following catheter directed delivery [34]. The fabricated Alg-USPIO microspheres, as embolic agents, also demonstrated a similar compressibility with commercially available embolic microspheres (LC beads (Biocompatible, UK)) (Fig. S5) [20,35,36]. This optimized non-organic solvent-based spray-atomization-coagulation method could be highly productive for fabricating the embolic microspheres with relatively low size distribution compared to the conventional emulsion method (Fig. S6) and easy to combine microspheres with additional imaging contrast or chemotherapeutic agents for various applications. Easy purification process of the fabricated microspheres in spray method will also mitigate the concern for residual impurity or organic solvent/surfactant in the emulsion method that has been used for embolic microspheres. Further, well-established spray science practices utilized in industry settings [37,38] should readily allow the mass production 30–500 μm microspheres embolic agents potential clinical translation.

Fig. 2.

(a) Size and size distribution of Alg-USPIO microspheres, (inset) An optical microscopic image of Alg-USPIO microspheres (scale bar: 50 μm). (B) A schematic of the principle of on-demand degradation with ion chelating EDTA agent. (c) In vitro on-demand degradation of Alg-USPIO microspheres dispersed in a blood serum. White bars represent 50 μm. (d) Degradation time of microspheres dispersed in blood serum or Milli-Q water from the addition of EDTA solution (EDTA concentration: 1, 5, 10 and 30 mM).

3.2. In vitro and in vivo on-demand instant degradation of microspheres

Current side effects of embolization therapies mostly originate from permanent or degradable embolic agents [11,39,40]. Complex recanalization procedures are often required in the cases of unintended severe ischemia [41], non-target occlusion [10], migration of embolic materials [42], and tumor recurrence/regrowth [43]. Effective on-demand degradable embolic agents will permit potentially more convenient recanalization procedure and precise targeted occlusion leading to improved therapeutic outcomes [9–11,44]. Alg-USPIO microspheres crosslinked with divalent ions (Ca2+) should ideally allow simple and fast degradation in the recanalization process involved with ion chelating agents. We evaluated the on-demand instant degradability of the fabricated Alg-USPIO microspheres with a well-known EDTA ion chelating agent which has been used in chelation therapy and various medical applications [22–24]. As shown in Fig. 2b, the addition of EDTA extracted Ca2+ions incorporated with carboxylate groups in the alginate matrix and resulted in instant disintegration and dissolution of the microspheres dispersed in blood serum (Fig. 2c). The degradation time of microspheres was shortened by increasing the concentration of EDTA (Fig. 2c). Alg-USPIO microspheres dispersed in each Milli-Q water and blood serum (2 mg/ml) were completely degraded within 200 s upon the addition of EDTA (5–30 mM EDTA, 10 μL) (Fig. 2d). Further, the degradation product by EDTA was tested for a potential cytotoxicity in Clone9 hepatocyte cells. It showed no cytotoxicity demonstrating ~90% cell viability in the tested EDTA concentration range (Fig. S7).

The rapid and complete degradation was also demonstrated in a capillary (Fig. 3a). As observed in vitro test, the embolized capillary with the Alg-USPIO microspheres easily restored the flow with EDTA mediated instant degradation. Any particles or fragments of the microspheres were not observed in the collected solution from the degradation (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Video 1). DLS measurement of the solution after the degradation also confirmed the complete degradation with two peaks corresponding to the dissolved alginate chains from the microspheres (Fig. S8) [45,46]. Demonstrated complete degradation of the microspheres will prevent any secondary vessel occlusion/ischemia during the use of temporary embolization or recanalization process. This on-demand instant degradation in vitro findings in both dish and capillary were further confirmed with in vivo mice studies. Alg-USPIO microspheres infused into a micro-vein of subcutaneous tissue directly blocked blood flow as shown the color change from red to pale white (Fig. 3b). Upon the infusion of 30 mM of EDTA (100 μL), the red blood color and flow were instantly restored (Fig. 3b).

Fig. 3.

(a) Optical microscope images of (top and middle) In vitro on-demand degradation of embolized Alg-USPIO microspheres in a capillary and (bottom) collected solution after the on-demand degradation of Alg-USPIO microspheres (white bars: 30 μm), (b) In vivo embolization and on-demand degradation in subcutaneous micro-vessel of mice. (white bars: 1 mm).

Supplementary video related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biomaterials.2020.120408

3.3. In vivo transcatheter intra-arterial embolization with alginate-USPIO microspheres and on-demand recanalization of the embolized artery in rabbits

Clinical feasibility of on-demand instant degradable embolic microspheres was further evaluated with interventional radiologists by performing transcatheter intra-arterial embolization and subsequent recanalization procedures in a rabbit model. The selected rabbit animal model has been commonly utilized for translational research in the field of Interventional Radiology [47,48]. Selective hepatic artery catheterization and embolization using the fabricated microspheres was performed with DSA guidance. The 2-F catheter was advanced into the celiac artery, proper hepatic artery (PHA), and the confluence of the right and left hepatic arteries (RHA and LHA, respectively) with a 0.014-inch-diameter guidewire (Fig. 4a). Under DSA imaging, we were able to demonstrate immediate occlusion and selective recanalization via instant degradation of the microspheres. The fabricated Alg-USPIO microspheres (10 mg/ml) were successfully infused into the upstream at the PHA bifurcation into the right and left hepatic arteries. DSA images from X-ray fluoroscopy confirmed occlusion of both RHA and LHA (Fig. 4a). Then, the DSA imaging also guided selective RHA recanalization procedure and confirmed recovered blood flow after the IA infusion of 30 mM EDTA (3 mL) into RHA (Fig. 4a) while the LHA remained occluded. The infused EDTA amount is much lower than the EDTA dosage using in chelation therapy in clinics [49]. IV or oral administration also can be considered for developing the process. Recently, MRI which is not using ionizing radiation has been increasingly utilized with the high spatial and temporal resolution as an interventional tool [50]. Thus, our embolization and recanalization procedures were also evaluated with gadolinium contrast enhanced MRI (CE-MRI). Similar to DSA images, CE-MRI showed clear vascular perfusion before the embolization (Fig. 4b). The embolization with IA infused microsphere was determined by cessation of flow in small vascular branches interconnected with hepatic arteries (Fig. 4b). After the EDTA treatment, the small vascular branches were visualized with high T1 contrast, confirming that the microspheres had been dissolved by the EDTA treatment (Fig. 4b). Additionally, an accumulation of IA infused microspheres incorporated with USPIO could be observed in T2 weighted MRI images (Fig. 4c). Decreased signals showing the distribution of microspheres in the branches of hepatic artery could be observed on T2 weighted MR images (Fig. 4c). The T2 contrast was directly restored following 30 mM EDTA treatment (Fig. 4c). The on-demand degradable and MRI visible Alg-USPIO microspheres, as demonstrated in the DSA and MRI image guided embolization and on-demand degradation procedures, may permit possible patient-specific adjustments to individual treatment protocols (additional infusions or recanalization to achieve improved therapeutic efficacy) [36]. Finally, the completion of on-demand degradation of microspheres was further confirmed with histological analysis of liver tissues after the on-demand recanalization. Clear hepatic artery after the on-demand degradation of microspheres was observed in H&E and Prussian blue stained tissues as similar with PBS treated control group (Fig. 5). The microspheres composed by alginate, USPIO and EDTA that have been used in clinics also could have high potential in safety for the clinical translation. On-demand complete degradation of Alg-USPIO microspheres will be promising to prevent any harmful off-target delivery, which can occur during the conventional recanalization procedures. This pre-clinical study is a proof of concept/feasibility study. Degradable microspheres have been of interest to the Interventional Radiology community and in development for many years. Current limitations include the incomplete degradation of current devices with more distal embolization of degraded particles to the distal vascular bed, and the lack of knowledge regarding appropriate recanalization timepoints. These timepoints will likely vary, depending on the clinical scenario. The on-demand degradable calcium alginate microspheres utilized in the current study can be used to restore blood flow when non-target embolization is realized intra-procedurally. This is a current unmet need. Further, this platform can be used to study the appropriate length of embolization required for the diverse embolization applications (e.g., bleeding from trauma, embolization of benign conditions (uterine fibroid embolization), or embolization of malignant conditions (liver tumor embolization)).

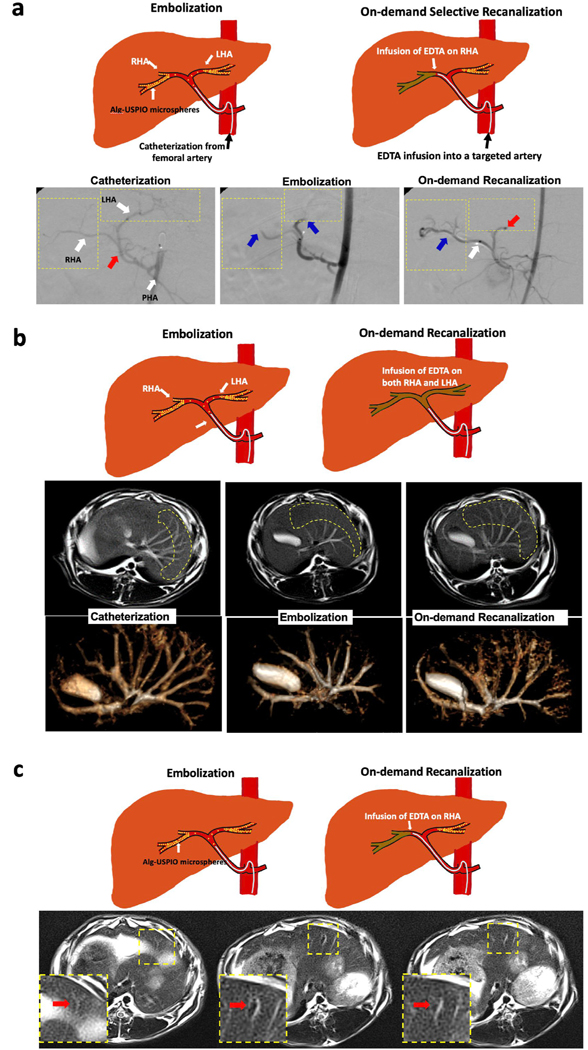

Fig. 4.

(a) (top) Schematics of in vivo embolization and on-demand degradation in white rabbit liver model and (bottom) DSA images confirming the procedures of catheterization (red arrow indicates the point of embolic agent infusion), embolization (blue arrows indicate an occlusion of left and right hepatic artery due to embolic agent), and on-demand recanalization (red arrow shows the continuous occlusion of left hepatic artery, blue arrow shows recanalization of right hepatic artery had started immediately after treatment of EDTA, and white arrow indicates the point of EDTA treatment with arterial catheter) in rabbit model. (b) (top) Schematics of procedures and (bottom) Gd contrasted enhanced T1 weighted and 3D-rendered MR images at each procedure of catheterization, embolization and on-demand degradation. (c) (top) Schematics of procedures and (bottom) T2 weighted MR images showing occluded MRI visible Alg-USPIO microspheres at each procedure of catheterization, embolization and on-demand degradation.

Fig. 5.

(top) H&E and (bottom) Prussian blue stained tissue images (4×, 10× and 20× magnification). On-demand degradation group was treated with EDTA on-demand recanalization of hepatic artery embolized with Alg-USPIO microspheres. Control group was treated with IA infusion of PBS. (CV: central vein, PV: portal vein, HA: hepatic artery, and BD: bile duct).

4. Conclusion

In summary, on-demand degradable and MRI visible embolic Alg-USPIO microspheres were fabricated with an optimized spray-coagulation method. Highly responsive degradation property of the fabricated alginate-based embolic microspheres the upon the addition of EDTA was demonstrated in respective in vitro capillary settings and in vivo mice micro vessel. On-demand instant degradability and MRI visibility of the Alg-USPIO should be promising to prevent various side effects from the embolization procedures using the conventional permanent and biodegradable temporary embolic materials. Thus, the fabricated microspheres were tested for potential transcatheter hepatic intra-arterial embolization and on-demand recanalization applications in a preclinical rabbit model with interventional radiologists. Interventional radiologists easily performed transcatheter IA infusion of Alg-USPIO embolic microspheres and confirmed the embolization of hepatic artery with DSA and CE-MRI image guidance. T2-MRI visibility of Alg-USPIO microspheres allowed to identify the distribution of IA infused microspheres that cannot be shown in DSA and CE-MRI. Subsequent on-demand recanalization process via selectively chosen IA infusion of EDTA solution was also conveniently performed. DSA, CE-MRI and T2-MRI confirmed the on-demand degradation of the microspheres and recanalization of embolized artery with restored blood flow. The developed on-demand degradable Alg-USPIO microsphere and preclinically demonstrated immediate restoration of blood flow during image-guided embolization and recanalization will permit potential effective embolization therapy and time controlled vascular occlusion that can overcome limitations and improve clinical outcome of current embolization therapies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was mainly supported by grants R01CA218659 and R01EB026207 from the National Cancer Institute and National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering. This work was also supported by the Center for Translational Imaging and Mouse Histology and Phenotyping Laboratory at Northwestern University.

Footnotes

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biomaterials.2020.120408.

Data availability

The raw and processed data required to reproduce these findings will be available upon request.

References

- [1].Jander HP, Russinovich NA, Transcatheter gelfoam embolization in abdominal, retroperitoneal, and pelvic hemorrhage, Radiology 136 (2) (1980) 337–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].DeHoll J, Shin P, Angle J, Steers W, Alternative approaches to the management of priapism, Int. J. Impot. Res. 10 (1) (1998) 11–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Peck DJ, McLoughlin RF, Hughson MN, Rankin RN, Percutaneous embolotherapy of lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage, J. Vasc. Intervent. Radiol. 9 (5) (1998) 747–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Lin D-Y, Liaw Y-F, Lee T-Y, Lai C-M, Hepatic arterial embolization in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma—a randomized controlled trial, Gastroenterology 94 (2) (1988) 453–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Goldstein HM, Medellin H, Beydoun MT, Wallace S, Ben-Menachem Y, Bracken R, Johnson DE, Transcatheter embolization of renal cell carcinoma, Am. J. Roentgenol. 123 (3) (1975) 557–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Gupta S, Johnson MM, Murthy R, Ahrar K, Wallace MJ, Madoff DC, McRae SE, Hicks ME, Rao S, Vauthey JN, Hepatic arterial embolization and chemoembolization for the treatment of patients with metastatic neuroendocrine tumors: variables affecting response rates and survival, Cancer 104 (8) (2005) 1590–1602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Murayama Y, Nien YL, Duckwiler G, Gobin YP, Jahan R, Frazee J, Martin N, Viñuela F, Guglielmi detachable coil embolization of cerebral aneurysms: 11 years’ experience, J. Neurosurg. 98 (5) (2003) 959–966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Goodwin SC, Vedantham S, McLucas B, Forno AE, Perrella R, Preliminary experience with uterine artery embolization for uterine fibroids, J. Vasc. Intervent. Radiol. 8 (4) (1997) 517–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Dinter DJ, Rexin M, Kaehler G, W.J.J.o.V. Neff I, Radiology, Fatal coil migration into the stomach 10 years after endovascular celiac aneurysm repair 18 (1) (2007) 117–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].López-Benítez R, Richter GM, Kauczor H-U, Stampfl S, Kladeck J, Radeleff BA, Neukamm M, Hallscheidt PJ, Analysis of nontarget embolization mechanisms during embolization and chemoembolization procedures, Cardiovasc. Intervent. Radiol. 32 (4) (2009) 615–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Sakamoto I, Aso N, Nagaoki K, Matsuoka Y, Uetani M, Ashizawa K, Iwanaga S, Mori M, Morikawa M, Fukuda TJR, Complications associated with transcatheter arterial embolization for hepatic tumors 18 (3) (1998) 605–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Virmani S, Rhee TK, Ryu RK, Sato KT, Lewandowski RJ, Mulcahy MF, Kulik LM, Szolc-Kowalska B, Woloschak GE, Yang G-Y, Comparison of hypoxia-inducible factor-1α expression before and after transcatheter arterial embolization in rabbit VX2 liver tumors, J. Vasc. Intervent. Radiol. 19 (10) (2008) 1483–1489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Woodside J, Schwarz H, Bergreen P, Peripheral embolization complicating bilateral renal infarction with Gelfoam, Am. J. Roentgenol. 126 (5) (1976) 1033–1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Tegtmeyer CJ, Smith TH, Shaw A, Barwick KW, Kattwinkel JJ, Renal infarction: a complication of gelfoam embolization of a hemangioendothelioma of the liver, Am. J. Roentgenol. 128 (2) (1977) 305–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Sharma KV, Dreher MR, Tang Y, Pritchard W, Chiesa OA, Karanian J, Peregoy J, Orandi B, Woods D, Donahue D, Esparza J, Jones G, Willis SL, Lewis AL, Wood BJ, Development of “imageable” beads for transcatheter embolotherapy, J. Vasc. Intervent. Radiol. : J. Vasc. Intervent. Radiol. 21 (6) (2010) 865–876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Tan WH, Takeuchi S, Monodisperse alginate hydrogel microbeads for cell encapsulation, Adv. Mater. 19 (18) (2007) 2696–2701. [Google Scholar]

- [17].Choi YS, Hong SR, Lee YM, Song KW, Park MH, Nam YS, Study on gelatin-containing artificial skin: I. Preparation and characteristics of novel gelatin-alginate sponge, Biomaterials 20 (5) (1999) 409–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Balakrishnan B, Mohanty M, Umashankar PR, Jayakrishnan A, Evaluation of an in situ forming hydrogel wound dressing based on oxidized alginate and gelatin, Biomaterials 26 (32) (2005) 6335–6342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Sun J, Tan H, Alginate-based biomaterials for regenerative medicine applications, Materials 6 (4) (2013) 1285–1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Kim D-H, Chen J, Omary RA, Larson AC, MRI visible drug eluting magnetic microspheres for transcatheter intra-arterial delivery to liver tumors, Theranostics 5 (5) (2015) 477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Sun J, Tan H, Alginate-based biomaterials for regenerative medicine applications 6 (4) (2013) 1285–1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Graeme KA, Pollack CV, Heavy metal toxicity, part ii: lead and metal fume fever, J. Emerg. Med. 16 (2) (1998) 171–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Lamas GA, Goertz C, Boineau R, Mark DB, Rozema T, Nahin RL, Lindblad L, Lewis EF, Drisko J, Lee KL, Tact Investigators, Effect of disodium EDTA chelation regimen on cardiovascular events in patients with previous myocardial infarction: the TACT randomized trial, J. Am. Med. Assoc. 309 (12) (2013) 1241–1250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Escolar E, Lamas GA, Mark DB, Boineau R, Goertz C, Rosenberg Y, Nahin RL, Ouyang P, Rozema T, Magaziner A, Nahas R, Lewis EF, Lindblad L, Lee KL, The effect of an EDTA-based chelation regimen on patients with diabetes mellitus and prior myocardial infarction in the trial to assess chelation therapy (TACT), Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcome 7 (1) (2014) 15–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Jeon MJ, Gordon AC, Larson AC, Chung JW, Kim YI, Kim DH, Transcatheter intra-arterial infusion of doxorubicin loaded porous magnetic nano-clusters with iodinated oil for the treatment of liver cancer, Biomaterials 88 (2016) 25–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Kim DH, Guo Y, Zhang ZL, Procissi D, Nicolai J, Omary RA, Larson AC, Temperature-sensitive magnetic drug carriers for concurrent gemcitabine chemohyperthermia, Adv. Healthc. Mater. 3 (5) (2014) 714–724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Kameniku J, Bhatia SK, Characterization of Compressibility in Alginate Microspheres, Northeast Bioengin C, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Hossain KMZ, Patel U, Ahmed I, Development of microspheres for biomedical applications: a review, Progress Biomater. 4 (1) (2015) 1–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Freitas S, Merkle HP, Gander BJ, Microencapsulation by solvent extraction/evaporation: reviewing the state of the art of microsphere preparation process technology, J. Contr. Release 102 (2) (2005) 313–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Yang Y-Y, Chung T-S, Bai X-L, Chan W-KJ, Effect of preparation conditions on morphology and release profiles of biodegradable polymeric microspheres containing protein fabricated by double-emulsion method, Chem. Eng. Sci. 55 (12) (2000) 2223–2236. [Google Scholar]

- [31].Zhang J, Li X, Zhang D, Xiu Z, Theoretical and experimental investigations on the size of alginate microspheres prepared by dropping and spraying, J. Microencapsul. 24 (4) (2007) 303–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Ge J, Hu Y, Biasini M, Beyermann WP, Yin YJ, Superparamagnetic magnetite colloidal nanocrystal clusters, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 46 (23) (2007) 4342–4345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Kim DH, Guo Y, Zhang Z, Procissi D, Nicolai J, Omary RA, Larson AC, Temperature-sensitive magnetic drug carriers for concurrent gemcitabine chemohyperthermia, Adv. Healthc. Mater. 3 (5) (2014) 714–724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Kim D-H, Larson AC, Nanocomposite carriers for transarterial chemoembolization of liver cancer, Intervent. Oncol. 4 (11) (2016) E173. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Caine M, Zhang X, Hill M, Guo W, Ashrafi K, Bascal Z, Kilpatrick H, Dunn A, Grey D, Bushby R, Bushby A, Willis SL, Dreher MR, Lewis AL, Comparison of microsphere penetration with LC Bead LUMI™ versus other commercial microspheres, J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 78 (2018) 46–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Kim DH, Choy T, Huang S, Green RM, Omary RA, Larson AC, Microfluidic fabrication of 6-methoxyethylamino numonafide-eluting magnetic microspheres, Acta Biomater. 10 (2) (2014) 742–750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Dias MI, Ferreira IC, Barreiro MF, Microencapsulation of bioactives for food applications, Food Funct. 6 (4) (2015) 1035–1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Chan E-S, Lim T-K, Ravindra P, Mansa RF, Islam A, The effect of low air-to-liquid mass flow rate ratios on the size, size distribution and shape of calcium alginate particles produced using the atomization method, J. Food Eng. 108 (2) (2012) 297–303. [Google Scholar]

- [39].Takayasu K, Moriyama N, Muramatsu Y, Shima Y, Ushio K, Yamada T, Kishi K, Hasegawa H, Gallbladder infarction after hepatic artery embolization, Am. J. Roentgenol. 144 (1) (1985) 135–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Clark TW, Complications of Hepatic Chemoembolization, Seminars in Interventional Radiology, Copyright© vol. 333, by Thieme Medical Publishers, Inc., Seventh Avenue, New, 2006, pp. 119–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Tarazov PG, Polysalov VN, Prozorovskij KV, Grishchenkova IV, Rozengauz EV, Ischemic complications of transcatheter arterial chemoembolization in liver malignancies, Acta Radiol. 41 (2) (2000) 156–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Lazzaro MA, Badruddin A, Zaidat OO, Darkhabani Z, Pandya DJ, Lynch JR, Endovascular embolization of head and neck tumors, Front. Neurol. 2 (2011) 64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Park JH, Han JK, Chung JW, Han MC, Kim ST, Postoperative recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma: results of transcatheter arterial chemoembolization, Cardiovasc. Intervent. Radiol. 16 (1) (1993) 21–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Lewis AL, Adams C, Busby W, Jones SA, Wolfenden LC, Leppard SW, Palmer RR, Small S, Comparative in vitro evaluation of microspherical embolisation agents, J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 17 (12) (2006) 1193–1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Lima AMF, Soldi V, Borsali R, Dynamic light scattering and viscosimetry of aqueous solutions of pectin, sodium alginate and their mixtures: effects of added salt, concentration, counterions, temperature and chelating agent, J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 20 (2009) 1705–1714. [Google Scholar]

- [46].Tanahatoe JJ, Kuil ME, Polyelectrolyte aggregates in solutions of sodium poly (styrenesulfonate), J. Phys. Chem. B 101 (31) (1997) 5905–5908. [Google Scholar]

- [47].Chen J, White SB, Harris KR, Li W, Yap JW, Kim DH, Lewandowski RJ, Shea LD, Larson AC, Poly(lactide-co-glycolide) microspheres for MRI-monitored delivery of sorafenib in a rabbit VX2 model, Biomaterials 61 (2015) 299–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Au - Khabbaz RC, Au - Huang Y-H, Au - Smith AA, Au - Garcia KD, Au - Lokken RP, Au - Gaba RC, Development and angiographic use of the rabbit VX2 model for liver cancer, JoVE 143 (2019), e58600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Lamas GA, Goertz C, Boineau R, Mark DB, Rozema T, Nahin RL, Drisko JA, Lee KL, Design of the trial to assess chelation therapy (TACT), Am. Heart J. 163 (1) (2012) 7–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Breyer T, Echternach M, Arndt S, Richter B, Speck O, Schumacher M, Markl M, Dynamic magnetic resonance imaging of swallowing and laryngeal motion using parallel imaging at 3 T, Magn. Reson. Imag. 27 (1) (2009) 48–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.