Abstract

Background/Aims:

In clinical trials, participant retention is critical to reduce bias and maintain statistical power for hypothesis testing. Within a multi-center clinical trial of diabetic retinopathy, we investigated whether regular phone calls to participants from the coordinating center improved long-term participant retention.

Methods:

Among 305 adults in the DRCR Retina Network Protocol S randomized trial, 152 participants were randomly assigned to receive phone calls at baseline, 6 months, and annually through 3 years (annual contact group) while 153 participants were assigned to receive a phone call at baseline only (baseline contact group). All participants could be contacted if visits were missed. The main outcomes were visit completion, excluding deaths, at 2 years (the primary outcome time point) and at 5 years (the final time point).

Results:

At baseline, 77% (117 of 152) of participants in the annual contact group and 76% (116 of 153) in the baseline contact group were successfully contacted. Among participants in the annual contact group active at each annual visit (i.e., not dropped from the study or deceased), 85% (125 of 147), 79% (108 of 136), and 88% (110 of 125) were contacted successfully by telephone around the time of the 1-, 2-, and 3-year visits, respectively. In the annual and baseline contact groups, completion rates for the 2-year primary outcome visit were 88% (129 of 147) versus 87% (125 of 144), respectively, with a risk ratio of 1.01 (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.93–1.10, P = .81). At 5 years, the final study visit, participant completion rates were 67% (96 of 144) versus 66% (88 of 133) with a risk ratio of 1.01 (95% CI, 0.85–1.19, P = .93). At 2 years, the completion rate of participants successfully contacted at baseline was 89% (202 of 226) versus 80% (52 of 65) who were not contacted successfully (risk ratio = 1.12 [95% CI 0.98–1.27], P = .09); at 5 years, the completion percentages by baseline contact success were 69% (148 of 213) versus 56% (36 of 64) (risk ratio = 1.24 [95% CI 0.98–1.56], P = .08).

Conclusions:

Regular phone calls from the coordinating center to participants during follow-up in this randomized clinical trial did not improve long-term participant retention.

Keywords: retention, loss to follow-up, multi-center randomized clinical trial

Introduction

Participant retention in clinical trials is a major factor affecting study validity and generalizability of study results. If retention is lower than anticipated, statistical power can be reduced, which makes identifying true differences between treatments more difficult, and pertinent safety observations can be missed. In addition, missing data can bias results when a participant’s decision to drop out is associated with the treatment assignment or study outcome. Identifying ways to improve participant retention in clinical trials is therefore important.

The DRCR Retina Network (formerly known as The Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network), funded by the National Institutes of Health, is a collaborative network of approximately 120 clinical sites in the United States and Canada that is dedicated to conducting high quality, collaborative clinical research that improves vision and quality of life for people with retinal diseases. As of June 1, 2019, the DRCR Retina Network has initiated 29 multicenter longitudinal clinical studies since its inception in 2003. A key role of the Network coordinating center (Jaeb Center for Health Research, Tampa, FL) is to help clinical sites maximize participant retention. For longitudinal studies, the coordinating center has supplemented individual site contact with study participants by maintaining its own direct contact with the participants, which is specified in the informed consent form. Contact is made with participants at baseline and at least annually thereafter. When needed, the coordinating center also contacts participants to assist in scheduling follow-up visits and tracks participants who miss a visit. Using this system, a high completion rate has been achieved for the primary outcome in several major DRCR Retina Network randomized trials: 95% in Protocol I (1 year, 854 eyes randomized),1 96% in Protocol T (1 year, 660 eyes),2 and 87% in Protocol S (2 years, 394 eyes).3

Considerable resources are needed to maintain routine participant calls from the coordinating center. Since its inception, the coordinating center has made over 30,000 telephone calls to study participants. It is unknown whether these calls increase participant retention. We assessed the value of the contact process within a DRCR Retina Network randomized clinical trial (Protocol S) by randomly assigning participants to receive contact from the coordinating center at baseline, 6 months, and annual visits through 3 years (annual contact) or to receive contact at baseline only (baseline contact). Follow-up continued through 5 years.

Methods

In Protocol S, 305 individuals with proliferative diabetic retinopathy were randomly assigned to receive either laser treatment or injections of a drug (ranibizumab) into the study eye.3 The sample size was chosen for the primary outcome of change in visual acuity from baseline and not the current analysis. Eighty-nine participants had both eyes enrolled into the study and were randomly assigned to receive laser in one eye and injections in the other eye. Participants receiving injections had visits every month in year 1 and every 4 to 16 weeks in years 2 through 5 depending on the status of the diabetic retinopathy, which was used to determine the need for reinjection. Participants in the laser group had visits approximately every 16 weeks through 5 years; however, they could be seen more regularly if the disease worsened.

In addition to treatment, participants were assigned randomly with equal probability to receive telephone calls at baseline, 6 months, and at annual visits thereafter (annual contact), or to receive a call at baseline only (baseline contact). Randomization was stratified by treatment group and performed on the study website using computer-generated random numbers. Owing to limited resources, planned contacts were discontinued after 3 years. Participants in both contact frequency groups were contacted by the coordinating center to assist with visit scheduling if follow-up visits were missed (i.e., “tracking” calls) at any time during the 5-year follow-up. A total of 10 coordinating center staff made calls to participants.

The study adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by relevant institutional review boards. Study participants provided written informed consent. The informed consent forms, which were approved by the institutional review board associated with each site, indicated that the coordinating center would receive participant contact information and that the coordinating center might contact individual participants twice per year or when a participant could not be located by the clinical site. Participants could provide cell, work, and home telephone numbers, indicate a preferred method and time of contact, and provide permission to leave a message if there was no answer. All numbers were used if a participant could not be reached.

Coordinating center staff were trained to ensure consistency across calls; however, a strict script was not used. Staff made calls irrespective of the participant’s contact frequency group, but staff were masked to the participant’s treatment group. When possible, the same staff member contacted the same participant throughout the duration of the trial. Each call was standardized to confirm the participant’s next study appointment, check whether contact information had changed, remind the participant of the importance of continued follow-up, express appreciation for the participant’s willingness to continue in the study, and remind the participant that the coordinating center could serve as a resource if the participant experienced any study-related issues. Although the duration of each call was not captured, calls generally took less than 5 minutes once the participant was reached. In addition to calls, all participants received a welcome letter from the coordinating center after enrollment, a study logo item annually (e.g., an umbrella), and birthday and holiday cards annually. A newsletter was sent in conjunction with publication of the 2-year primary results. If a participant was unreachable after 3 attempts, a standardized letter was sent to encourage the participant to contact the coordinating center. Communications were conducted in English or Spanish per the stated preference of the participant.

At 2 years (primary outcome time point) and 5 years (final study visit), visit completion rates (excluding deaths) were compared between groups using Poisson regression with robust variance estimation to estimate the risk ratio.4 There was no formal adjustment for multiplicity. Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina, USA).

Results

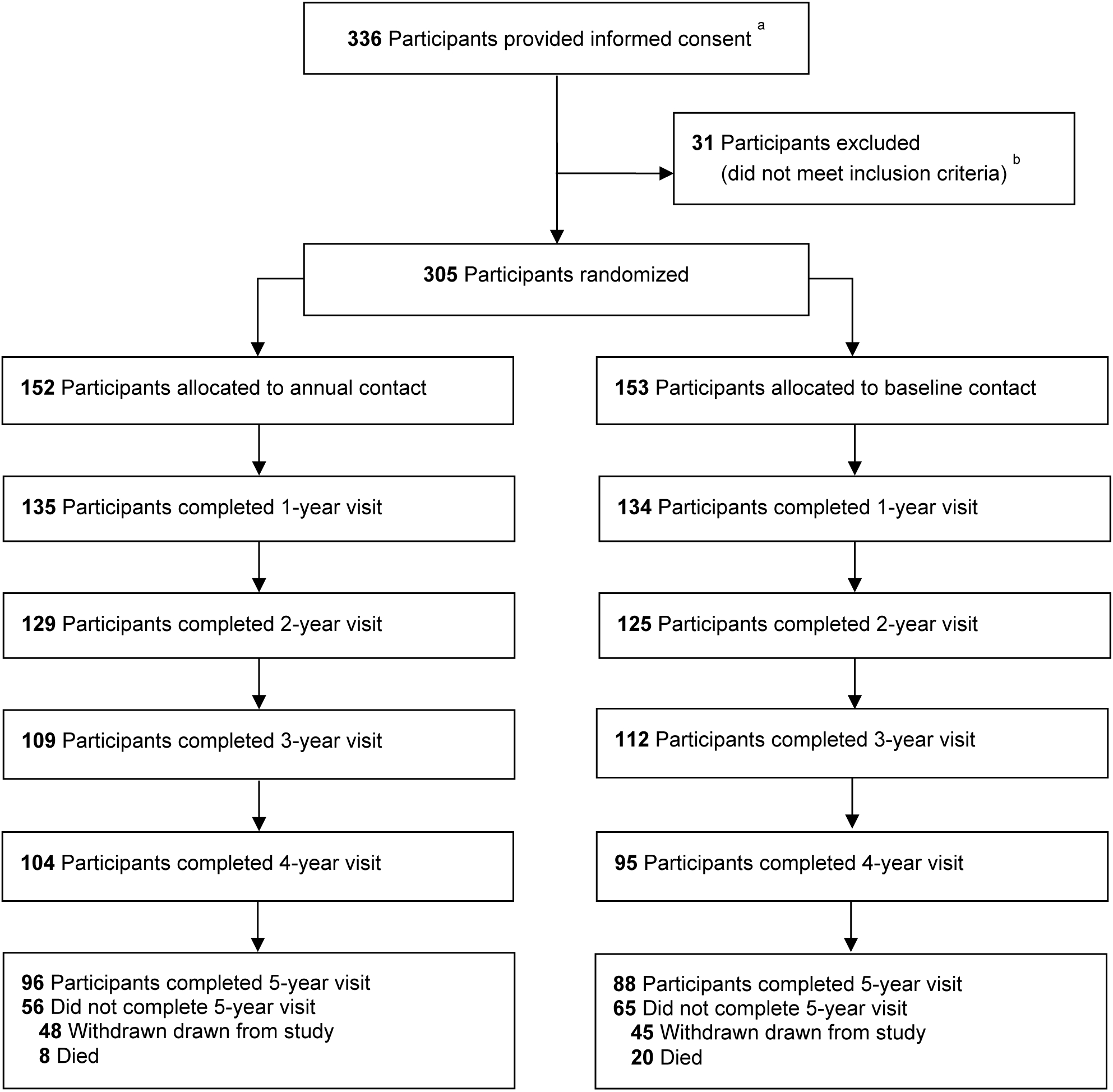

Among 305 participants, 152 were randomly assigned to annual contact and 153 were assigned to baseline contact (Table 1). Within the annual and baseline contact groups respectively, 33% (50) and 34% (52) were in the injection group, 37% (56) and 38% (58) were in the laser group, and 30% (46) and 28% (43) had two study eyes (i.e., one in each treatment group); 46% (70) and 42% (65) were female, 52% (79) and 53% (81) self-identified as white, and mean age was 52 in each group. Figure 1 is the CONSORT flow diagram.

Table 1.

Baseline Participant Characteristics.

| Annual Contact N=152 | Baseline Contact N=153 | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR), y | 53 (44–60) | 51 (45–59) |

| Female, No. (%) | 70 (46) | 65 (42) |

| Race/ethnicity, No. (%) | ||

| Non-Hispanic white | 79 (52) | 81 (53) |

| Hispanic or Latino | 41 (27) | 37 (24) |

| Non-Hispanic black or African American | 27 (18) | 31 (20) |

| Asian | 1(<1) | 2 (2) |

| American Indian or Alaskan Native | 1 (<1) | 0 |

| More than one race | 2 (1) | 0 |

| Unknown or not reported | 1 (<1) | 2 (1) |

| Treatment Group, No. (%) | ||

| Injection (one study eye) | 50 (33) | 52 (34) |

| Laser (one study eye) | 56 (37) | 58 (38) |

| Two study eyes (one in each group) | 46 (30) | 43 (28) |

| Diabetes type, No. (%) | ||

| Type 1 | 34 (22) | 28 (18) |

| Type 2 | 112 (74) | 119 (78) |

| Uncertain | 6 (4) | 6 (4) |

| Duration of diabetes, median (IQR), y | 17 (10–24) | 18 (11–23) |

| Hemoglobin A1c, median (IQR), % | 8.7 (7.4–10.3) | 8.5 (7.3–10.4) |

| Arterial blood pressure, median (IQR), mmHg | 100 (88–108) | 97 (89–105) |

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range.

Figure 1.

a Participants were not formally screened prior to obtaining informed consent.

b Information was not collected on specific reasons for exclusion.

At baseline, 77% (117 of 152) of participants in the annual contact group and 76% (116 of 153) in the baseline contact group were successfully contacted. Among participants successfully versus not successfully contacted at baseline (combining annual and baseline contact groups), 44% (102) and 46% (33) were female, 58% (136) and 33% (24) self-identified as white, and median age was 52 regardless of call success. Among participants in the annual contact group active at each annual visit (i.e., not dropped from the study or deceased), 85% (125 of 147), 79% (108 of 136), and 88% (110 of 125) were successfully contacted by telephone around the time of the 1-, 2-, and 3-year visits (46 to 74 weeks, 100 to 117 weeks, and 144 to 172 weeks), respectively. During the first 3 years, excluding baseline calls, participants in the annual contact group were successfully contacted for a routine or tracking call a median (interquartile range) of 4 (3–4) times, while participants in the baseline contact group were contacted for a tracking call a median of 1 (1–1) time.

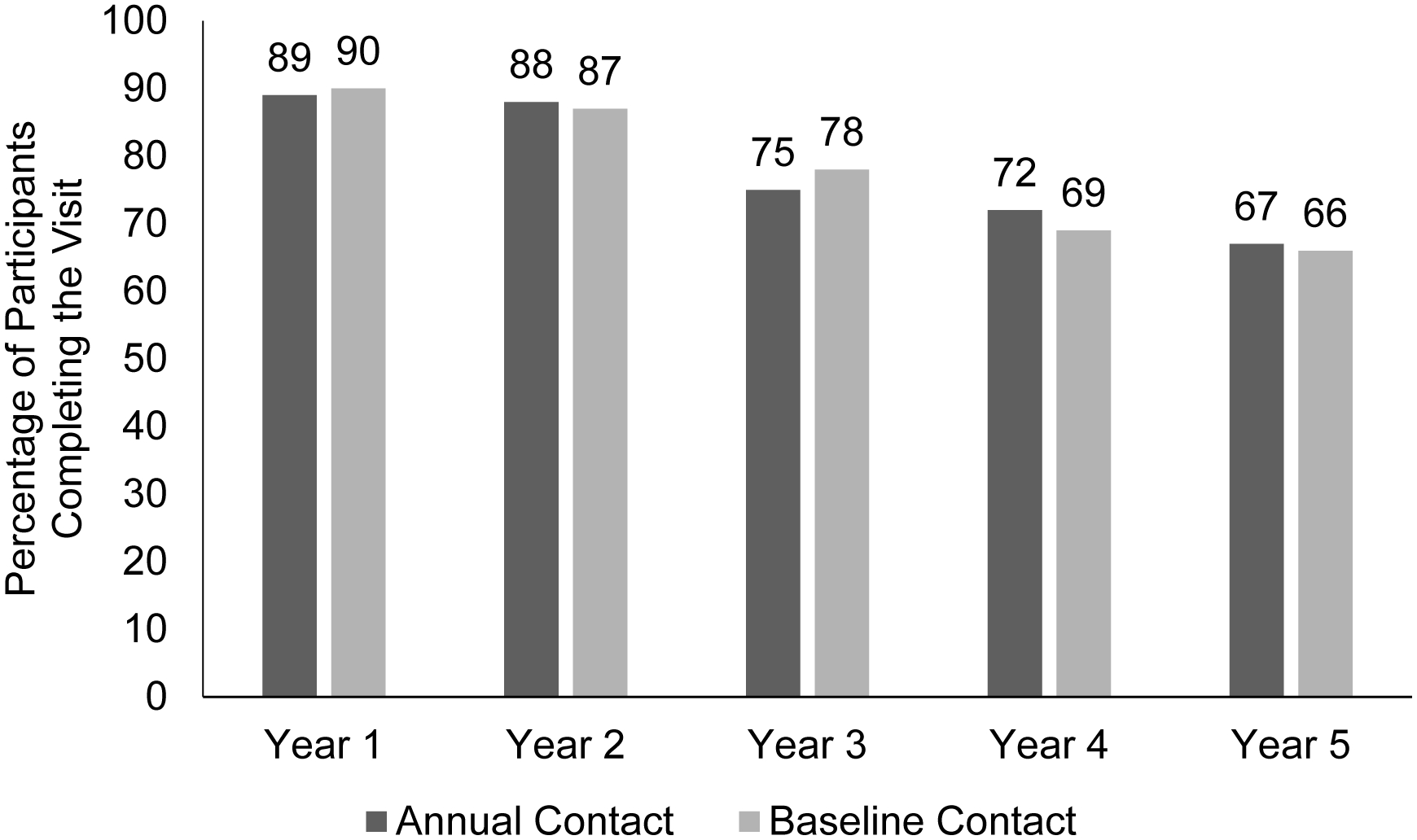

Figure 2 shows the completion rates (censoring deaths) of annual visits in each group over the 5 years of the study. In the annual and baseline contact groups, respectively, completion rates for the 2-year primary outcome visit were 88% (129 of 147) versus 87% (125 of 144) with a risk ratio of 1.01 (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.93–1.10, P = .81). At 5 years, the final study visit, completion rates were 67% (96 of 144) versus 66% (88 of 133) with a risk ratio of 1.01 (95% CI, 0.85–1.19, P = .93). Results were similar when adjusting for the covariates of age, sex, race/ethnicity, language, and treatment group (2 years: risk ratio = 1.00, 95% CI 0.92–1.10, P = .92; 5 years: risk ratio = 0.98, 95% CI 0.83–1.16, P = .83). When deaths were included in the analysis as non-completion (sensitivity analysis), the completion rates in the annual and baseline contact groups were 85% (129 of 152) versus 82% (125 of 153) at 2 years (risk ratio = 1.04, 95% CI 0.94–1.15, P = .46), and 63% (96 of 152) versus 58% (88 of 153) at 5 years (risk ratio = 1.10, 95% CI 0.92–1.32, P = .31).

Figure 2.

Annual visit completion (excluding deaths) of participants randomized to annual or baseline telephone contact from the coordinating center within a longitudinal randomized clinical trial. Randomization to contact frequency group was independent of randomization to treatment group.

At 2 years, the completion rate of participants successfully contacted at baseline was 89% (202 of 226) versus 80% (52 of 65) that were not successfully contacted; the risk ratio of 2-year visit completion for successful versus non-successful baseline call was 1.12 (95% CI 0.98–1.27, P = .09). At 5 years, the percentages by baseline contact success were 69% (148 of 213) versus 56% (36 of 64) with a risk ratio of 1.24 (95% CI 0.98–1.56, P = .08).

Completion rates by contact frequency within subgroups defined by age, sex, race/ethnicity, geographic region, treatment group, language, and number of participants randomized at the participant’s site are shown in Table 2. Reasons for participant dropout are shown in Table 3. Most participants who did not complete the study were lost to follow-up (32 of 48 [67%] and 22 of 45 [49%] in the annual and baseline contact groups).

Table 2.

Five-Year Completion by Contact Frequency and Baseline Characteristics (Excluding Deaths).

| Annual Contact | Baseline Contact | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | No. Completed (%) | N | No. Completed (%) | |

| Overall | 144 | 96 (67) | 133 | 88 (66) |

| Age | ||||

| < 50 y | 61 | 43 (70) | 60 | 40 (67) |

| ≥ 50 y | 83 | 53 (64) | 73 | 48 (66) |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 67 | 44 (66) | 57 | 39 (68) |

| Male | 77 | 52 (68) | 76 | 49 (64) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| White | 76 | 54 (71) | 68 | 51 (75) |

| Hispanic or Latino | 39 | 23 (59) | 33 | 20 (61) |

| Black/African American | 24 | 15 (63) | 28 | 16 (57) |

| Other | 4 | 3 (75) | 2 | 1 (50) |

| Unknown or not reported | 1 | 1 (100) | 2 | 0 |

| US Census Region | ||||

| Northeast | 21 | 12 (57) | 20 | 12 (60) |

| Midwest | 14 | 13 (93) | 17 | 13 (76) |

| South | 83 | 55 (66) | 77 | 52 (68) |

| West | 26 | 16 (62) | 19 | 11 (58) |

| Treatment Group | ||||

| Injection (one study eye) | 48 | 31 (65) | 41 | 30 (73) |

| Laser (one study eye) | 51 | 34 (67) | 56 | 33 (59) |

| Two study eyes (one in each group) | 45 | 31 (69) | 36 | 25 (69) |

| Language | ||||

| English | 131 | 90 (69) | 127 | 84 (66) |

| Spanish | 13 | 6 (46) | 6 | 4 (67) |

| Number of Participants Randomized at Site | ||||

| 1204 | 36 | 28 (78) | 36 | 26 (72) |

| 5 or more | 108 | 68 (63) | 97 | 62 (64) |

Table 3.

Reasons for Participant Drops by Contact Frequency.

| Dropped Reason, No. (%) | Annual Contact N=48 | Baseline Contact N=45 |

|---|---|---|

| Lost to follow-up | 32 (67) | 22 (49) |

| Site withdrew participant | 5 (10) | 3 (7) |

| Unknown | 1 (2) | 6 (13) |

| Travel difficulty | 2 (4) | 4 (9) |

| Poor health | 3 (6) | 2 (4) |

| Did not want study treatment | 2 (4) | 2 (4) |

| Difficulty contacting participant | 0 | 2 (4) |

| Visit too lengthy | 0 | 2 (4) |

| Moved | 2 (4) | 0 |

| Adverse event | 1 (2) | 1 (2) |

| Changed doctor | 0 | 1 (2) |

Discussion

Optimizing participant retention is critical to clinical trial success. This study evaluated whether annual calls from a coordinating center to participants during a longitudinal, randomized clinical trial would improve participant retention. Through 5 years, there was no difference in participant retention whether participants were assigned to contact at baseline only or at baseline, 6 months, and annual visits through 3 years.

To our knowledge, no other clinical trial has evaluated whether frequency of participant contact from a coordinating center improves participant retention. Other studies have found phone calls, text messages, and/or emails to be effective in improving adherence to medication, questionnaire response, and cancer screening,5–7 but we were unable to identify studies where clinical trial retention was the main outcome for such interventions. Improving retention defined as participant completion of in-clinic visits remains a challenge. Monetary incentives have been shown to increase the response of postal and electronic questionnaires.8 Whether such incentives would increase in-clinic retention is currently unknown.

Although this study was not designed to address the effect of baseline contact on long-term retention rates, participants who were successfully contacted at baseline may have had higher retention rates at 2 and 5 years. Additional studies would be needed to test this hypothesis. However, given these results, additional focus from the coordinating center and clinical sites might be needed for participants who were not successfully contacted by the coordinating center at baseline.

Based on the results of this study, the DRCR Retina Network has discontinued routine follow-up calls to study participants. Because the impact of the initial baseline call is unknown, the DRCR Retina Network will continue to make participant calls at baseline. As-needed tracking calls to facilitate participant scheduling when a visit is missed will also continue. Given the time and resources required to conduct follow-up calls, the reduction in call burden is estimated to result in an annual cost savings of approximately $20,000 across DRCR Retina Network trials.

This study had several limitations. First, some calls were not successfully completed. At baseline, only three-quarters of calls were successfully completed despite multiple attempts. It is unknown whether a higher call success rate would have resulted in better follow-up rates. In addition, we do not know if increasing or decreasing contact frequency would affect retention. Second, annual calls were discontinued after 3 years even though follow-up continued through 5 years. However, there were no appreciable differences in retention rates between the contact groups either before or after the 3-year time point. Third, the frequency of contact from site personnel was not systematically collected in this study. We still consider the relationship between site personnel and participants to be critical for retention.9 Fourth, these results are from a cohort with high morbidity and mortality; it is unknown if similar results would be found in a healthier cohort, such as individuals with non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Fifth, it is conceivable that the frequency of clinic visits, which differed by treatment group in this study, could have affected the efficacy of phone calls (e.g., calls could be more effective when visits are infrequent); however, treatment groups were balanced between contact frequency groups. Finally, 5-year follow-up completion may have been affected by publication of the primary trial results at 2 years; however, all participants were notified of the results regardless of contact frequency or treatment group.

Successful retention of study participants is a key determinant of a trial’s success. These results do not support the hypothesis that routine annual telephone calls from a coordinating center to participants during a clinical trial for diabetic retinopathy improve participant retention. Future studies focusing on alternative methods to increase patient retention, such as text messaging, are needed.

Financial support:

Supported through a cooperative agreement from the National Eye Institute and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services EY14231, EY23207, EY18817. Genentech provided ranibizumab for the study and funds to the DRCR Retina Network to defray the study’s clinical site costs.

The National Institutes of Health participated in oversight of the conduct of the study and review of the manuscript but not directly in the design or conduct of the study nor in the collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication. Per the DRCR Retina Network Industry Collaboration Guidelines (available at http://www.drcr.net), the DRCR Retina Network had complete control over the design of the protocol, ownership of the data, and all editorial content of presentations and publications related to the protocol.

Financial Disclosures: A complete list of all DRCR Retina Network investigator financial disclosures can be found at www.drcr.net.

References

- 1.Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network. Randomized trial evaluating ranibizumab plus prompt or deferred laser or triamcinolone plus prompt laser for diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmology. 2010;117(6):1064–1077 e1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network, Wells JA, Glassman AR, et al. Aflibercept, bevacizumab, or ranibizumab for diabetic macular edema. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(13):1193–1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Writing Committee for the Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network, Gross JG, Glassman AR, et al. Panretinal photocoagulation vs intravitreous ranibizumab for proliferative diabetic retinopathy: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;314(20):2137–2146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spiegelman D, Hertzmark E. Easy SAS calculations for risk or prevalence ratios and differences. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;162(3):199–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thakkar J, Kurup R, Laba TL, et al. Mobile Telephone Text Messaging for Medication Adherence in Chronic Disease: A Meta-analysis. JAMA internal medicine. 2016;176(3):340–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wong MS, Ching JL, Lam TT, et al. Association of interactive reminders and automated messages with persistent adherence to colorectal cancer screening: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncology. 2017;3(9):1281–1283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clark L, Ronaldson S, Dyson L, Hewitt C, Torgerson D, Adamson J. Electronic prompts significantly increase response rates to postal questionnaires: a randomized trial within a randomized trial and meta-analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2015;68(12):1446–1450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brueton VC, Tierney JF, Stenning S, et al. Strategies to improve retention in randomised trials: a Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2014;4(2):e003821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zweben A, Fucito LM, O’Malley SS. Effective Strategies for Maintaining Research Participation in Clinical Trials. Drug information journal. 2009;43(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]