To the Editor: A 45-year-old man with severe antiphospholipid syndrome complicated by diffuse alveolar hemorrhage,1 who was receiving anticoagulation therapy, glucocorticoids, cyclophosphamide, and intermittent rituximab and eculizumab, was admitted to the hospital with fever (Fig. S1 in the Supplementary Appendix, available with the full text of this letter at NEJM.org). On day 0, Covid-19 was diagnosed by SARS-CoV-2 reverse-transcriptase–polymerase-chain-reaction (RT-PCR) assay of a nasopharyngeal swab specimen, and the patient received a 5-day course of remdesivir (Fig. S2). Glucocorticoid doses were increased because of suspected diffuse alveolar hemorrhage. He was discharged on day 5 without a need for supplemental oxygen.

From day 6 through day 68, the patient quarantined alone at home, but during the quarantine period, he was hospitalized three times for abdominal pain and once for fatigue and dyspnea. The admissions were complicated by hypoxemia that caused concern for recurrent diffuse alveolar hemorrhage and was treated with increased doses of glucocorticoids. SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR cycle threshold (Ct) values increased to 37.8 on day 39, which suggested resolving infection (Table S1).2,3

On day 72 (4 days into another hospital admission for hypoxemia), RT-PCR assay of a nasopharyngeal swab was positive, with a Ct value of 27.6, causing concern for a recurrence of Covid-19. The patient again received remdesivir (a 10-day course), and subsequent RT-PCR assays were negative.

On day 105, the patient was admitted for cellulitis. On day 111, hypoxemia developed, ultimately requiring treatment with high-flow oxygen. Given the concern for recurrent diffuse alveolar hemorrhage, the patient’s immunosuppression was escalated (Figs. S1 through S3). On day 128, the RT-PCR Ct value was 32.7, which caused concern for a second Covid-19 recurrence, and the patient was given another 5-day course of remdesivir. A subsequent RT-PCR assay was negative. Given continued respiratory decline and concern for ongoing diffuse alveolar hemorrhage, the patient was treated with intravenous immunoglobulin, intravenous cyclophosphamide, and daily ruxolitinib, in addition to glucocorticoids.

On day 143, the RT-PCR Ct value was 15.6, which caused concern for a third recurrence of Covid-19. The patient received a SARS-CoV-2 antibody cocktail against the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein (Regeneron).4 On day 150, he underwent endotracheal intubation because of hypoxemia. A bronchoalveolar-lavage specimen on day 151 revealed an RT-PCR Ct value of 15.8 and grew Aspergillus fumigatus. The patient received remdesivir and antifungal agents. On day 154, he died from shock and respiratory failure.

We performed quantitative SARS-CoV-2 viral load assays in respiratory samples (nasopharyngeal and sputum) and in plasma, and the results were concordant with RT-PCR Ct values, peaking at 8.9 log10 copies per milliliter (Fig. S2 and Table S1). Tissue studies showed the highest SARS-CoV-2 RNA levels in the lungs and spleen (Figs. S4 and S5).

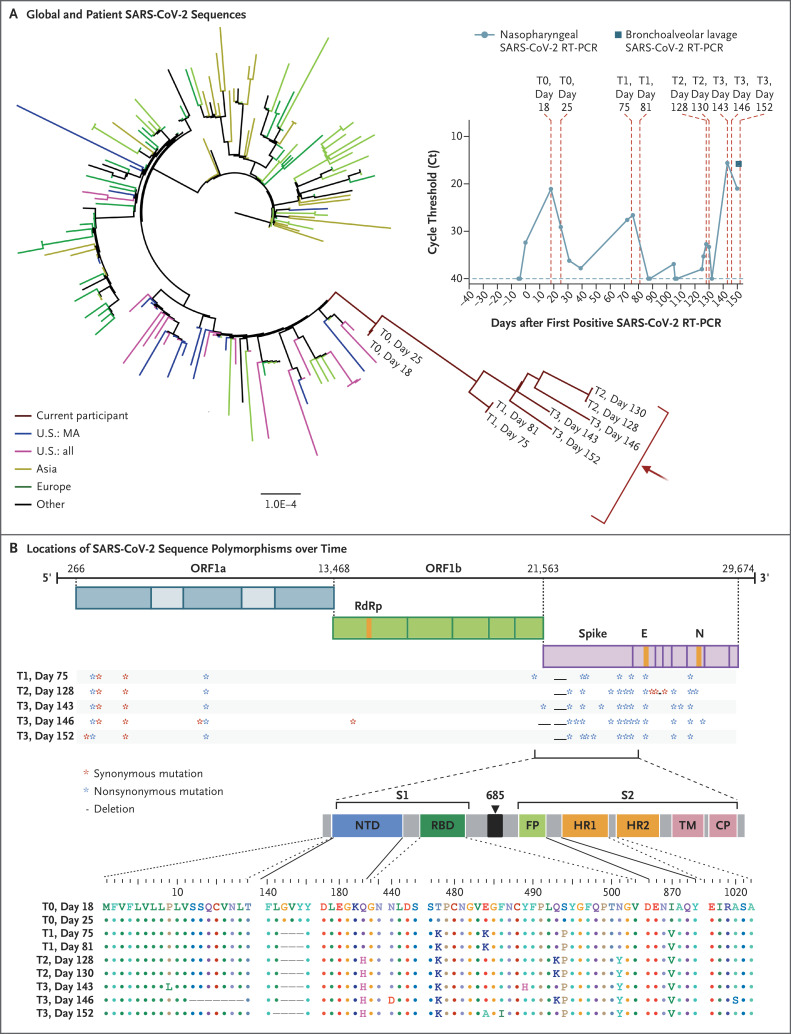

Phylogenetic analysis was consistent with persistent infection and accelerated viral evolution (Figures 1A and S6). Amino acid changes were predominantly in the spike gene and the receptor-binding domain, which make up 13% and 2% of the viral genome, respectively, but harbored 57% and 38% of the observed changes (Figure 1B). Viral infectivity studies confirmed infectious virus in nasopharyngeal samples from days 75 and 143 (Fig. S7). Immunophenotyping and SARS-CoV-2–specific B-cell and T-cell responses are shown in Table S2 and Figures S8 through S11.

Figure 1. SARS-CoV-2 Whole-Genome Viral Sequencing from Longitudinally Collected Nasopharyngeal Swabs.

Shown in Panel A is a maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree with patient sequences (red arrow) at four time points with high levels of SARS-CoV-2 viral loads (T0 denotes days 18 and 25; T1 days 75 and 81; T2 days 128 and 130; and T3 days 143, 146, and 152), along with representative sequences from the state (U.S.: MA), country (U.S.: all), Asia, Europe, and Other (Africa, South America, and Canada). The scale represents 0.0001 nucleotide substitutions per site. The inset shows nasopharyngeal and bronchoalveolar-lavage SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR cycle threshold (Ct) values; the horizontal dashed line represents the cutoff for positivity at 40, and vertical red dashed lines represent days of viral sequencing (days 18, 25, 75, 81, 128, 130, 143, 146, and 152). Shown in Panel B are the locations of deletions and synonymous and nonsynonymous mutations in the patient at T1, T2, and T3 as compared with T0. CP denotes cytoplasmic domain, E envelope, FP fusion peptide, HR1 heptad repeat 1, HR2 heptad repeat 2, N nucleocapsid, NTD N-terminal domain, ORF open reading frame, RBD receptor-binding domain, RdRp RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, S1 subunit 1, S2 subunit 2, and TM transmembrane domain.

Although most immunocompromised persons effectively clear SARS-CoV-2 infection, this case highlights the potential for persistent infection5 and accelerated viral evolution associated with an immunocompromised state.

Supplementary Appendix

Disclosure Forms

This letter was published on November 11, 2020, at NEJM.org.

Footnotes

Supported in part by the Massachusetts Consortium for Pathogen Readiness through grants from the Evergrande Fund; Mark, Lisa, and Enid Schwartz; the Harvard University Center for AIDS Research (NIAID 5P30AI060354); Brigham and Women’s Hospital; and a grant (1UL1TR001102) from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences to the Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center.

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this letter at NEJM.org.

References

- 1.Deane KD, West SG. Antiphospholipid antibodies as a cause of pulmonary capillaritis and diffuse alveolar hemorrhage: a case series and literature review. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2005;35:154-165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wölfel R, Corman VM, Guggemos W, et al. Virological assessment of hospitalized patients with COVID-2019. Nature 2020;581:465-469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.He X, Lau EHY, Wu P, et al. Temporal dynamics in viral shedding and transmissibility of COVID-19. Nat Med 2020;26:672-675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baum A, Fulton BO, Wloga E, et al. Antibody cocktail to SARS-CoV-2 spike protein prevents rapid mutational escape seen with individual antibodies. Science 2020;369:1014-1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Helleberg M, Utoft Niemann C, Sommerlund Moestrup K, et al. Persistent COVID-19 in an immunocompromised patient temporarily responsive to two courses of remdesivir therapy. J Infect Dis 2020;222:1103-1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.