Abstract

The purpose of the present study was to identify aberrantly expressed genes for gallbladder cancer based on the annotation analysis of microarray studies and to explore their potential functions. Differential gene expression was investigated in cholesterol polyps, gallbladder adenoma and gallbladder cancer using microarrays. Subsequently, microarray results were comprehensively analyzed. Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) analyses were performed to determine the affected biological processes or pathways. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) of cholesterol polyps, gallbladder adenoma and gallbladder cancer were identified. Following comprehensive analysis, 14 genes were found to be differentially expressed in the gallbladder wall of both gallbladder cancer and gallbladder adenoma. The 20 most significantly upregulated genes were only upregulated in the gallbladder wall of gallbladder cancer, but not in the gallbladder wall of cholesterol polyps and gallbladder adenoma. In addition, 182 DEGs were upregulated in the gallbladder wall of gallbladder adenoma compared with the gallbladder wall of cholesterol polyps. A total of 20 most significant DEGs were found in both the tumor and gallbladder wall of gallbladder cancer. In addition, the most significant DEGs that were identified were only upregulated in the tumor of gallbladder cancer. GO and KEGG analysis indicated that the aforementioned DEGs could participate in numerous biological processes or pathways associated with the development of gallbladder cancer. The present findings will help improve the current understanding of tumorigenesis and the development of gallbladder cancer.

Keywords: gallbladder diseases, gallbladder cancer, cholesterol polyps, gallbladder adenoma, biomarkers

Introduction

Gallbladder cancer is the most common malignant tumor of the biliary tract and is the third most common gastrointestinal malignancy worldwide (1). Due to the vague clinical symptoms and signs of gallbladder cancer, most patients are diagnosed at an advanced stage (2). Since the etiology and pathogenesis of gallbladder cancer are still unclear, it is essential to research the molecular mechanism of the disease and explore novel potential biomarkers that may assist early diagnosis and treatment.

Gallbladder adenoma is a rare disease and rarely malignant, but transformation may occur (3). Previous evidence has proposed that adenomas are the premalignant lesions of gallbladder cancer (3,4). However, the genetic evidence is still poorly defined (5). Due to the poor prognosis of gallbladder cancer, it is crucial to distinguish benign and malignant gallbladder adenoma (6). There is a need for accurate diagnostic methods to distinguish between benign and malignant diseases. Currently, the size and number of gallbladder polyps, along with patient age, are typically used to assist with distinguishing benign and malignant diseases (7). For example, previous research has found that conjugated bile acids (glycochenodeoxycholic and taurochenodeoxycholic) could be identified as possible biomarkers for cholesterol polyps and adenomatous polyps, and the gallbladder bile acids glycochenodeoxycholic acid and taurochenodeoxycholic acid are highly expressed in cholesterol polyps (8). For patients with gallbladder carcinoma, compared with healthy individuals and patients with cholesterol polyps, serum vascular endothelial growth factors (SVEGF)-C are closely related with lymph node metastasis, distant metastasis and stage, in addition, SVEGF-D has a positive relationship with the tumor depth, lymph, distant metastasis and stage that could represent available biomarkers for the diagnosis of gallbladder carcinoma (6).

The present study aimed to comprehensively analyze a transcriptome profile and identify DEGs in gallbladder cancer based on annotation analysis of microarray studies.

Materials and methods

Patients and tissue samples

Gallbladder stones (two men and one woman; age range, 60–62 years), gallbladder adenoma (two men and one woman; age range, 60–62 years) and gallbladder carcinoma (two men and one woman; age range, 60–63 years) tissues (n=3 each) were obtained from the Department of Pancreaticobiliary Surgery, the First Affiliated Hospital of China Medical University between September 2018 and December 2019. All cases were reviewed by two or more independent pathologists. No patients received radiation or chemotherapy before surgery. During the surgery, fresh tumor tissues or gallbladder wall tissues were collected in the operating room and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen within 15 min and then stored in RNA Fixer reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) at −80°C for total RNA extraction. The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee of The First Affiliated Hospital of China Medical University (2018075). All patients who participated in the study signed written informed consent.

RNA extraction and transcript analysis

RNA extraction was performed using an RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Total RNA was quantified using a NanoDrop ND-2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and the RNA integrity was assessed with an Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent Technologies, GmbH). Total RNA samples were analyzed on the Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 and amplified RNA (aRNA) was prepared using the GeneChip 3′IVT Express kit (Affymetrix; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Briefly, cDNA was synthesized by reverse transcription, and a double-stranded DNA template was then obtained by second-strand synthesis. Subsequently, an aRNA labeled with biotin was inverted in vitro utilizing GeneChip 3′IVT Express kit (Affymetrix; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) at 40°C for 16 h and stored at 4°C. The aRNA was purified, fragmented and hybridized with the chip probe (Beckman Coulter, Inc.). Following hybridization, the chip was automatically washed using a GeneChip Hybridization Wash and Stain kit (Affymetrix; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and dyed using GeneChip Fluidics Station 450 instrument (Affymetrix; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Finally, it was scanned to obtain the image and the Affymetrix microarray data using a GeneChip Scanner 3000 (Affymetrix; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

To obtain the raw data, the Feature Extraction function in GeneSpring (version 10.5.1.1; Agilent Technologies, GmbH) was utilized to analyze the array image. Briefly, the raw data were normalized with the quantile algorithm. In the experiment, probe groups in the lowest 20% of the signal strength in the two sample groups were filtered as background noise. The coefficient of variation of the probe group was calculated in the sample group, and the probe group with a coefficient of variation >25% in both groups were also filtered out. Finally, DEG transcripts were identified.

To explore DEGs in different gallbladder diseases, further analysis was conducted, as shown in Table I. In the present study, gallstones served as normal samples compared with cholesterol polyps, gallbladder adenoma and gallbladder cancer.

Table I.

Six groups for differential expression analysis via microarray analysis.

| Groups | Tissue type | Number of samples | Comparison |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group I | Gallbladder wall | 3 | Cholesterol polyps vs. gallbladder stones |

| Group II | Gallbladder wall | 3 | Gallbladder adenoma vs. gallbladder stones |

| Group III | Gallbladder wall | 3 | Gallbladder cancer vs. gallbladder stones |

| Group IV | Gallbladder wall | 3 | Gallbladder adenoma vs. cholesterol polyps |

| Group V | Gallbladder wall | 3 | Gallbladder cancer vs. gallbladder adenoma |

| Group VI | Tumor tissue | 3 | Gallbladder cancer vs. gallbladder adenoma |

Differential expression analysis

In the present study, linear models for microarray data (version 3.44.3; Bioconductor) were performed based on empirical Bayesian distribution to calculate the P-value (9). The screening criteria for DEGs was as follows: |Fold change (FC)|>1.5 and P-value <0.05. To probe out DEGs in cholesterol polyps, gallbladder adenoma and gallbladder cancer, differential expression analyses including scatter plot analysis, volcano plot analysis and hierarchical clustering analysis were performed using GraphPad Prism (version 7.0; GraphPad Software, Inc.).

Comparative analysis

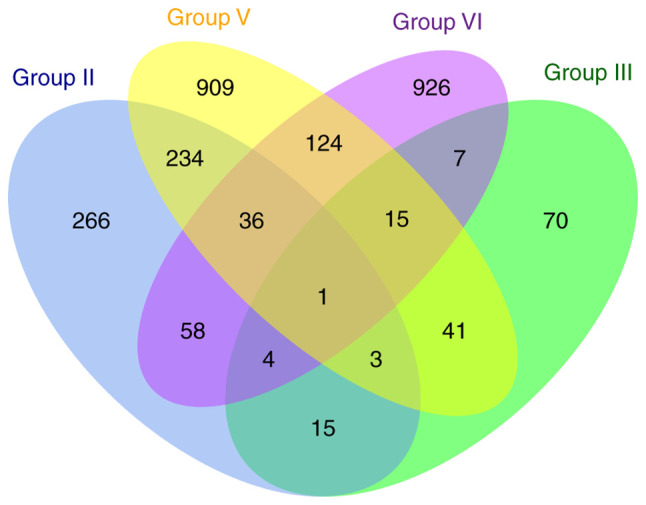

To explore differentially expressed genes between different diseases a comparative analysis was undertaken, as shown in Table II and Fig. 1. In group II, the gallbladder wall of gallbladder adenoma and gallbladder wall of gallbladder stones were compared. In group III, the gallbladder wall of gallbladder cancer and gallbladder wall of gallbladder stone were compared. In group IV, comparative analysis was performed between gallbladder wall of gallbladder adenoma and gallbladder wall of cholesterol polyps. For group V, comparative analysis between gallbladder wall of gallbladder cancer and gallbladder wall of gallbladder adenoma was presented.

Table II.

Comprehensive analysis of DEGs in the six groups.

| Comparative groups | Gallbladder wall of gallstone | Cholesterol polyps (gallbladder wall) | Gallbladder adenoma (gallbladder wall) | Gallbladder cancer (gallbladder wall) | Gallbladder adenoma (tumor wall) | Gallbladder cancer (tumor wall) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | ○ | √ | ||||

| II | ○ | √ | ||||

| III | ○ | √ | ||||

| IV | ○ | √ | ||||

| V | ○ | √ | ||||

| VI | ○ | √ | ||||

| A | ||||||

| a=I∩II∩III | √ | √ | √ | |||

| b=II∩III-a | √ | √ | ||||

| c=II-b-I∩II | √ | |||||

| d=III-b-I∩III | √ | |||||

| B=IV | √ | |||||

| C=V∩VI | √ | √ | ||||

| D=VI–V∩VI | √ |

∩ represents the common DEGs between two groups, √ and ○ represent different samples (gallbladder wall of gallstone, gallbladder wall of cholesterol polyps, gallbladder wall of gallbladder adenoma and tumor wall of gallbladder adenoma) used for intersection. DEGs, differentially expressed genes.

Figure 1.

Venn diagram showing comprehensive analysis methods, which involves the comparison of different groups, of DEGs in the six groups. Group II: Gallbladder wall of gallbladder adenoma vs. gallbladder wall of gallbladder stones. Group III: Gallbladder wall of gallbladder cancer vs. gallbladder wall of gallbladder stones; Group IV: Gallbladder wall of gallbladder adenoma vs. gallbladder wall of cholesterol polyps; Group V: Gallbladder wall of gallbladder cancer vs. gallbladder wall of gallbladder adenoma. The DEGs in groups I and VI were not compared in this analysis.

Functional enrichment analysis

To explore the biological processes or pathways involved in DEGs, Gene Ontology (GO; http://geneontology.org/) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG; http://www.kegg.jp/kegg/) pathway enrichment analyses were performed (10,11). GO terms include ‘biological process’ (BP), ‘molecular function’ (MF) and ‘cellular component’ (CC).

Validation of the differential expression and prognostic value of key genes using gene expression profiling interactive analysis (GEPIA)

Key genes were verified by GEPIA (http://gepia.cancer-pku.cn/) in The Cancer Genome Atlas (https://www.cancer.gov/about-nci/organization/ccg/research/structural-genomics/tcga) and Genotype-Tissue Expression dataset (GTEx; http://commonfund.nih.gov/GTEx/) (12). Differential expression and overall survival (OS) analyses were performed.

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) assay

A total of 10 pairs of gallbladder cancer tissues and normal tissues (five men and five woman; age range, 55–65 years) were collected from the Department of Pancreaticobiliary Surgery, the First Affiliated Hospital of China Medical University between September 2018 and December 2019. All patients signed written informed consent. Total RNA was extracted from tissues using TRIzol® reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). According to the manufacturer's instructions, reverse transcription was performed using a TaqMan Real-Time PCR kit (Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). RT-qPCR was run on a CFX96 Real-Time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.). The following primer pairs were used for the qPCR: HLA class II histocompatibility antigen, DP a1 chain (HLA-DPB1) forward, 5′-ATGACACTCTTCTGAATTGACTG-3′ and reverse, 5′-GGTAATGATAAAACATGCTCTC-3′; nuclear receptor subfamily 4 group A member 2 (NR4A2) forward, 5′-TCATCTCCTCAGACTGGGGG-3′ and reverse, 5′-TGTACCAAATGCCCCTGTCC-3′; ephrin-B2 (EFNB2) forward, 5′-TATGCAGAACTGCGATTTCCAA-3′ and reverse, 5′-TGGGTATAGTACCAGTCCTTGTC-3′; four and a half LIM domains protein 1 forward (FHL1), 5′-AAATGCACAAAGTGTGCCCG-3′ and reverse, 5′-TCGTTTGGGACACTCAGCAC-3′; insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 7 (IGFBP7) forward, 5′-ACAGTGGTTGATGCCTTAC-3′ and reverse, 5′-CCCTTATGGGTTGCTAACTAC-3′; Rho Family GTPase (RND) forward, 5′-CTATGACCAGGGGGCAAATA-3′ and reverse, 5′-TCTTCGCTTTGTCCTTTCGT-3′; E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase NEURL1B (NEURL1B) forward, 5′-ACAGCAGCTTCCAAGACACA-3′ and reverse, 5′-GTTGGGCAGGCTGTAGTAGG-3′; and GAPDH forward, 5′-ACTCCCATTCTTCCACCTTTG-3′ and reverse, 5′-CCCTGTTGCTGTAGCCATATT-3′. GADPH served as an internal control. The relative expression levels were determined using the 2−ΔΔCq method (13).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analysis was conducted on R (14) or GraphPad Prism 7.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc.). Data were expressed as the mean ± SD. Each experiment was repeated at least three times. Comparisons between groups were analyzed by a Student's t-test. GO and KEGG annotation enrichment analyses were evaluated using a Fisher's exact test. For OS analysis, the samples were divided into high and low expression groups according to the median expression value of key genes. Differences between two groups were compared with Kaplan-Meier curves, followed by log-rank test. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Transcript analysis results

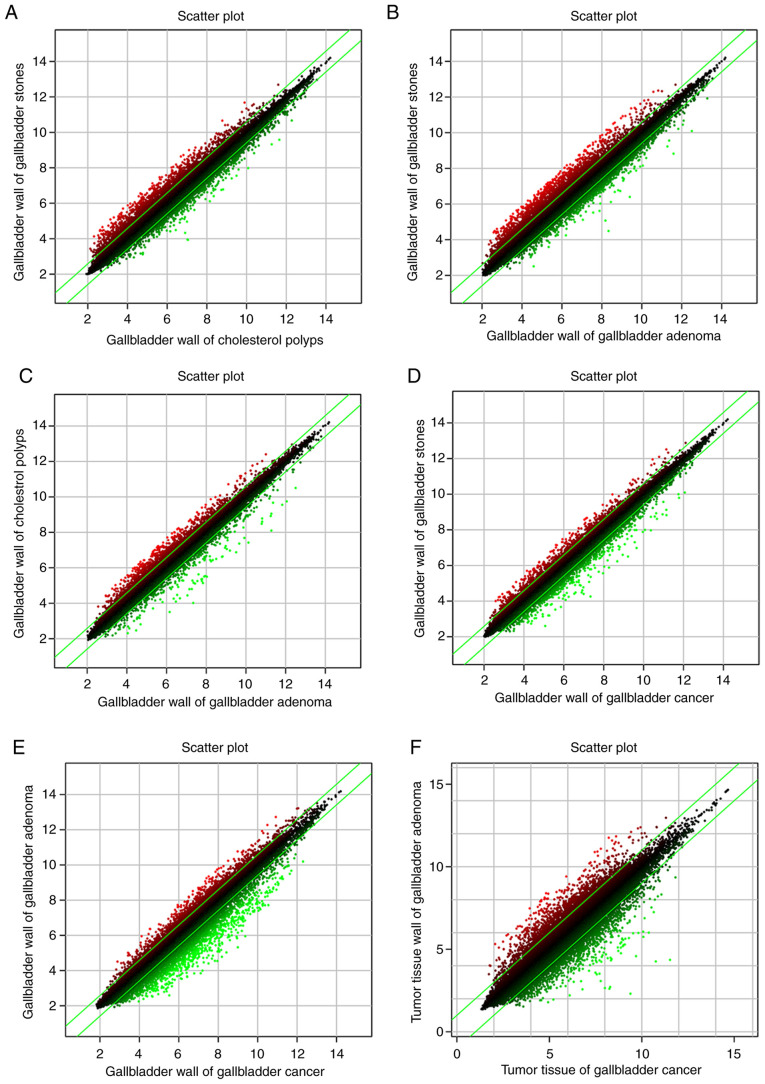

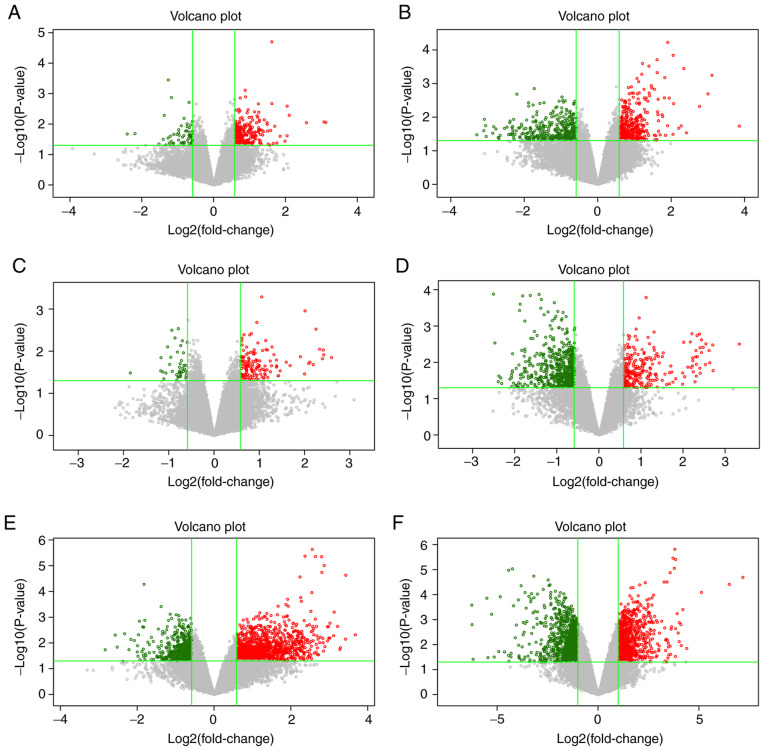

In the present study, the gene expression profiles in the compared groups were analyzed via microarray analysis. The differential expression analysis results were shown in Table III according to |FC|>1.5 and P-value <0.05. The DEGs were marked for further analysis (Tables SI–SVI listed all DEGs in the six compared groups). The scatter plots show the distribution of upregulated genes in the two groups (Fig. 2). The volcano plots were used to show the DEGs between different compared groups. In Fig. 3, the red and green dots represented DEGs with the criteria of | FC |>1.5 and P-value <0.05, and the gray dot indicates genes with no significant difference.

Table III.

Differentially expressed genes in six different comparative groups.

| Comparative groups | Total number of upregulated genes | Total number of downregulated genes |

|---|---|---|

| I | 198 | 43 |

| II | 346 | 271 |

| III | 116 | 40 |

| IV | 182 | 502 |

| V | 830 | 533 |

| VI | 540 | 632 |

Figure 2.

Scatter plots of genes in different compared groups. (A-F) Represent comparison I, II, III, IV, V and VI, respectively. Red represents upregulated genes and green represents downregulated genes. Comparison I: Gallbladder wall of gallstone vs. gallbladder wall of cholesterol polyps; Comparison II: Gallbladder wall of gallstone vs. gallbladder wall of gallbladder adenoma; Comparison III: Gallbladder wall of gallstone vs. gallbladder wall of gallbladder cancer; Comparison IV: Gallbladder wall of cholesterol polyps vs. gallbladder wall of gallbladder adenoma; Comparison V: Gallbladder wall of gallbladder adenoma vs. gallbladder wall of gallbladder cancer; Comparison VI: Tumor wall of gallbladder adenoma vs. tumor wall of gallbladder cancer.

Figure 3.

Volcano plots of compared groups. (A-F) Represent comparison I, II, III, IV, V and VI, respectively. Red represents upregulated genes and green represents downregulated genes. Comparison I: Gallbladder wall of gallstone vs. gallbladder wall of cholesterol polyps; Comparison II: Gallbladder wall of gallstone vs. gallbladder wall of gallbladder adenoma; Comparison III: Gallbladder wall of gallstone vs. gallbladder wall of gallbladder cancer; Comparison IV: Gallbladder wall of cholesterol polyps vs. gallbladder wall of gallbladder adenoma; Comparison V: Gallbladder wall of gallbladder adenoma vs. gallbladder wall of gallbladder cancer; Comparison VI: Tumor wall of gallbladder adenoma vs. tumor wall of gallbladder cancer.

To effectively distinguish DEGs in the different comparison groups, unsupervised hierarchical clustering analysis was performed. This analysis could distinguish between the different samples in the six comparison groups (Figs. S1–S6).

Comparative analysis

In comparison A (Groups I–III; Table II): i) A total of eight commonly upregulated genes [including Uncharacterized LOC101928168 (LOC101928168), 3-Hydroxy-3-Methylglutaryl-CoA Synthase 2 (HMGCS2), Secretagogin, EF-Hand Calcium Binding Protein (SCGN), Chimerin 2 (CHN2), X-Linked Kx Blood Group (XK), Mucin 6, Oligomeric Mucus/Gel-Forming (MUC6), Phospholipid Phosphatase 5 (PLPP5) and Heat Shock Protein Family H Member 1 (HSPH1)] and one downregulated gene [ST8 α-N-Acetyl-Neuraminide α-2,8-Sialyltransferase 4 (ST8SIA4)] were identified in cholesterol polyps, gallbladder adenoma and gallbladder cancer for gallbladder walls (data not shown); ii) A total of 14 common DEGs were found to overlap in the gallbladder wall of gallbladder cancer and gallbladder adenoma (Table IV); iii) A total of 273 differentially upregulated genes were only expressed in the gallbladder wall of gallbladder adenoma, of which the 20 most significantly DEGs, according to the FC, were selected to continue further analysis (Tables IV and V). A total of 85 upregulated genes were identified in the gallbladder wall of gallbladder cancer (Table VI). The 20 most significantly DEGs were selected, as shown in Table VI.

Table IV.

Common DEGs in the gallbladder wall of gallbladder cancer and gallbladder adenoma.

| A, Upregulated genes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entrez accession no. | Gene symbol | Gene name | Fold-change | P-value | False discovery rate |

| 1906 | EDN1 | Endothelin 1 | 1.549618769 | 0.029390674 | 0.955609729 |

| 83661 | MS4A8 | Membrane-spanning 4-domains, subfamily A, member 8 | 2.003454854 | 0.016940921 | 0.955609729 |

| 213 | ALB | Albumin | 2.246885592 | 0.044086126 | 0.955609729 |

| 10232 | MSLN | Mesothelin | 3.577553479 | 0.034944882 | 0.955609729 |

| 1515 | CTSV | Cathepsin V | 1.810360067 | 0.018438263 | 0.955609729 |

| 573 | BAG1 | BCL2 associated athanogene 1 | 1.619984489 | 0.045294551 | 0.955609729 |

| 100507412 | LOC100507412 | Uncharacterized LOC100507412 | 2.405560916 | 0.00588484 | 0.955609729 |

| 55283 | MCOLN3 | Mucolipin 3 | 2.597985418 | 0.035436453 | 0.955609729 |

| 7586 | ZKSCAN1 | Zinc finger with KRAB and SCAN domains 1 | 2.303988209 | 0.010795501 | 0.955609729 |

| B, Downregulated genes | |||||

| Entrez accession no. | Gene symbol | Gene name | Fold-change | P-value | False discovery rate |

| 6926 | TBX3 | T-box 3 | −1.97381941 | 0.024886922 | 0.955609729 |

| 25987 | TSKU | Tsukushi, small leucine rich proteoglycan | −1.506934454 | 0.049505143 | 0.955609729 |

| 6319 | SCD | Stearoyl-coa desaturase (delta-9-desaturase) | −1.692411038 | 0.031149526 | 0.955609729 |

| 4857 | NOVA1 | Neuro-oncological ventral antigen 1 | −1.754139316 | 0.041834676 | 0.955609729 |

| 5209 | PFKFB3 | 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-biphosphatase 3 | −1.859592699 | 0.015450602 | 0.955609729 |

Table V.

Top 20 upregulated genes in the gallbladder wall of gallbladder adenoma.

| Entrez accession no. | Gene symbol | Gene name | Fold-change | P-value | False discovery rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3115 | HLA-DPB1 | Major histocompatibility complex, class II, DP β1 | 14.39294587 | 0.018542717 | 0.95561 |

| 10321 | CRISP3 | Cysteine-rich secretory protein 3 | 8.596046776 | 0.000569554 | 0.95561 |

| 9153 | SLC28A2 | Solute carrier family 28 (concentrative nucleoside transporter), member 2 | 7.972874721 | 0.002038587 | 0.95561 |

| 1733 | DIO1 | Deiodinase, iodothyronine, type I | 4.13402372 | 0.000144984 | 0.95561 |

| 2568 | GABRP | γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) A receptor, pi | 4.11863611 | 0.032541353 | 0.95561 |

| 6555 | SLC10A2 | Solute carrier family 10 (sodium/bile acid cotransporter), member 2 | 3.729761379 | 5.99474E-05 | 0.95561 |

| 6819 | SULT1C2 | Sulfotransferase family 1C member 2 | 3.716642697 | 0.018104673 | 0.95561 |

| 4496 | MT1H | Metallothionein 1H | 3.527957872 | 0.000668336 | 0.95561 |

| 4494 | MT1F | Metallothionein 1F | 3.505661422 | 0.002675451 | 0.95561 |

| 54346 | UNC93A | Unc-93 homolog A (C. Elegans) | 3.355156356 | 0.008516354 | 0.95561 |

| 148523 | CIART | Circadian associated repressor of transcription | 3.136234278 | 0.026466979 | 0.95561 |

| 388561 | ZNF761 | Zinc finger protein 761 | 3.111132847 | 0.002949854 | 0.95561 |

| 100127888 | SLCO4A1-AS1 | SLCO4A1 antisense RNA 1 | 3.072422599 | 0.006932207 | 0.95561 |

| 4495 | MT1G | Metallothionein 1G | 3.050121402 | 0.00019533 | 0.95561 |

| 2069 | EREG | Epiregulin | 3.031503175 | 0.048716806 | 0.95561 |

| 7364 | UGT2B7 | UDP glucuronosyltransferase 2 family, polypeptide B7 | 2.971195084 | 0.035730027 | 0.95561 |

| 3821 | KLRC1 | Killer cell lectin-like receptor subfamily C, member 1 | 2.902803001 | 0.00149172 | 0.95561 |

| 3822 | KLRC2 | Killer cell lectin-like receptor subfamily C, member 2 | 2.902803001 | 0.00149172 | 0.95561 |

| 10562 | OLFM4 | Olfactomedin 4 | 2.899525179 | 0.03455814 | 0.95561 |

| 990 | CDC6 | Cell division cycle 6 | 2.763474564 | 0.001361724 | 0.95561 |

Table VI.

Top 20 upregulated genes in the gallbladder wall of gallbladder cancer.

| Entrez accession no. | Gene symbol | Gene name | Fold-change | P-value | False discovery rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 54474 | KRT20 | Keratin 20, type I | 6.027529 | 0.014263 | 0.99994 |

| 11075 | STMN2 | Stathmin 2 | 4.545556 | 0.021002 | 0.99994 |

| 22943 | DKK1 | Dickkopf WNT signaling pathway inhibitor 1 | 3.983841 | 0.034789 | 0.99994 |

| 3790 | KCNS3 | Potassium voltage-gated channel, modifier subfamily S, member 3 | 3.193245 | 0.022064 | 0.99994 |

| 3606 | IL18 | Interleukin 18 | 2.740635 | 0.029388 | 0.99994 |

| 8174 | MADCAM1 | Mucosal vascular addressin cell adhesion molecule 1 | 2.657304 | 0.038834 | 0.99994 |

| 1305 | COL13A1 | Collagen, type XIII, α1 | 2.593326 | 0.016279 | 0.99994 |

| 7171 | TPM4 | Tropomyosin 4 | 2.492788 | 0.012088 | 0.99994 |

| 84189 | SLITRK6 | SLIT and NTRK like family member 6 | 2.419904 | 0.007957 | 0.99994 |

| 79966 | SCD5 | Stearoyl-CoA desaturase 5 | 2.399926 | 0.02229 | 0.99994 |

| 56892 | C8orf4 | Chromosome 8 open reading frame 4 | 2.363066 | 0.030948 | 0.99994 |

| 81671 | VMP1 | Vacuole membrane protein 1 | 2.354891 | 0.017192 | 0.99994 |

| 406991 | MIR21 | MicroRNA 21 | 2.354891 | 0.017192 | 0.99994 |

| 55612 | FERMT1 | Fermitin family member 1 | 2.268497 | 0.042115 | 0.99994 |

| 55816 | DOK5 | Docking protein 5 | 2.254499 | 0.009369 | 0.99994 |

| 24147 | FJX1 | Four jointed box 1 | 2.241426 | 0.027788 | 0.99994 |

| 2043 | EPHA4 | EPH receptor A4 | 2.181555 | 0.036922 | 0.99994 |

| 1908 | EDN3 | Endothelin 3 | 2.174776 | 0.02892 | 0.99994 |

| 1316 | KLF6 | Kruppel-like factor 6 | 2.17353 | 0.022611 | 0.99994 |

| 440712 | C1orf186 | Chromosome 1 open reading frame 186 | 2.165575 | 0.034576 | 0.99994 |

| 5318 | PKP2 | Plakophilin 2 | 2.134774 | 0.043853 | 0.99994 |

| 63923 | TNN | Tenascin N | 2.081014 | 0.040874 | 0.99994 |

| 78989 | COLEC11 | Collectin subfamily member 11 | 2.067131 | 0.000518 | 0.99994 |

| 100131541 | LOC100131541 | Uncharacterized LOC100131541 | 2.032802 | 0.035034 | 0.99994 |

| 5727 | PTCH1 | Patched 1 | 2.01107 | 0.017085 | 0.99994 |

| 1359 | CPA3 | Carboxypeptidase A3 (mast cell) | 1.992477 | 0.022002 | 0.99994 |

| 3775 | KCNK1 | Potassium channel, two pore domain subfamily K, member 1 | 1.975891 | 0.02328 | 0.99994 |

| 5732 | PTGER2 | Prostaglandin E receptor 2 | 1.95077 | 0.006402 | 0.99994 |

| 51751 | HIGD1B | HIG1 hypoxia inducible domain family member 1B | 1.9257 | 0.025133 | 0.99994 |

| 23705 | CADM1 | Cell adhesion molecule 1 | 1.907871 | 0.044745 | 0.99994 |

In comparison B (Group IV; Table I), 684 DEGs in the gallbladder wall of gallbladder adenoma, of which 182 were upregulated and 502 were downregulated, shown in Table SIV. The top 20 DEGs are shown in Table VII. In comparison C, it was revealed that 177 DEGs were expressed both in the tumor tissue and gallbladder wall in gallbladder cancer. The 20 most significantly DEGs were selected according to the FC (Table VIII). In comparison D, 459 upregulated genes were found in the tumor of gallbladder cancer. The top 20 upregulated genes that were identified according to FC in Table IX.

Table VII.

Top 20 upregulated genes in the gallbladder wall of gallbladder adenoma compared with the gallbladder wall of cholesterol polyps.

| Entrez accession no. | Gene symbol | Gene name | Fold-change | P-value | False discovery rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8076 | MFAP5 | Microfibrillar associated protein 5 | 10.055828 | 0.00313194 | 0.930859211 |

| 8483 | CILP | Cartilage intermediate layer protein | 5.7556811 | 0.01148426 | 0.930859211 |

| 8839 | WISP2 | WNT1 inducible signaling pathway protein 2 | 5.0126842 | 0.001836636 | 0.930859211 |

| 4495 | MT1G | Metallothionein 1G | 4.958911 | 0.024060491 | 0.930859211 |

| 4496 | MT1H | Metallothionein 1H | 4.7119253 | 0.018260689 | 0.930859211 |

| 2202 | EFEMP1 | EGF containing fibulin-like extracellular matrix protein 1 | 3.9536176 | 0.019679555 | 0.930859211 |

| 7364 | UGT2B7 | UDP glucuronosyltransferase 2 family, polypeptide B7 | 3.9512615 | 0.040165838 | 0.930859211 |

| 3489 | IGFBP6 | Insulin like growth factor binding protein 6 | 3.3672636 | 0.035074166 | 0.930859211 |

| 10562 | OLFM4 | Olfactomedin 4 | 3.3045794 | 0.018570013 | 0.930859211 |

| 4494 | MT1F | Metallothionein 1F | 3.2510145 | 0.01264233 | 0.930859211 |

| 64167 | ERAP2 | Endoplasmic reticulum aminopeptidase 2 | 3.1751689 | 0.039260457 | 0.930859211 |

| 1543 | CYP1A1 | Cytochrome P450, family 1, subfamily A, polypeptide 1 | 3.0349092 | 0.041312515 | 0.930859211 |

| 388561 | ZNF761 | Zinc finger protein 761 | 2.8743053 | 0.00550548 | 0.930859211 |

| 683 | BST1 | Bone marrow stromal cell antigen 1 | 2.8327043 | 0.00702193 | 0.930859211 |

| 55057 | AIM1L | Absent in melanoma 1-like | 2.8267351 | 0.031481094 | 0.930859211 |

| 100127888 | SLCO4A1-AS1 | SLCO4A1 antisense RNA 1 | 2.689454 | 0.01048406 | 0.930859211 |

| 30835 | CD209 | CD209 molecule | 2.6028341 | 0.048163532 | 0.930859211 |

| 148523 | CIART | Circadian associated repressor of transcription | 2.5922233 | 0.029837355 | 0.930859211 |

| 10720 | UGT2B11 | UDP glucuronosyltransferase 2 family, polypeptide B11 | 2.5871195 | 0.005778714 | 0.930859211 |

| 2199 | FBLN2 | Fibulin 2 | 2.5660098 | 0.024397318 | 0.930859211 |

Table VIII.

Top 20 upregulated genes both in the tumor and gallbladder wall in gallbladder cancer.

| Entrez accession no. | Gene symbol | Gene name | Fold-change | P-value | False discovery rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1490 | CTGF | Connective tissue growth factor | 12.721 | 0.0049 | 0.663 |

| 3115 | HLA-DPB1 | Major histocompatibility complex, class II, DP β1 | 8.0389 | 0.0066 | 0.663 |

| 3400 | ID4 | Inhibitor of DNA binding 4, dominant negative helix-loop-helix protein | 6.919 | 4E-06 | 0.044 |

| 3399 | ID3 | Inhibitor of DNA binding 3, dominant negative helix-loop-helix protein | 5.8099 | 0.0001 | 0.435 |

| 1282 | COL4A1 | Collagen, type IV, α1 | 5.3601 | 0.0398 | 0.663 |

| 4929 | NR4A2 | Nuclear receptor subfamily 4 group A member 2 | 5.0011 | 0.0113 | 0.663 |

| 2669 | GEM | GTP binding protein overexpressed in skeletal muscle | 4.6392 | 0.0094 | 0.663 |

| 1948 | EFNB2 | Ephrin-B2 | 4.5216 | 0.0087 | 0.663 |

| 3397 | ID1 | Inhibitor of DNA binding 1, dominant negative helix-loop-helix protein | 4.3673 | 0.0121 | 0.663 |

| 2919 | CXCL1 | Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 1 (melanoma growth stimulating activity, α) | 4.2191 | 0.0453 | 0.663 |

| 390 | RND3 | Rho family GTPase 3 | 4.1688 | 0.0017 | 0.663 |

| 2273 | FHL1 | Four and a half LIM domains 1 | 4.1366 | 0.011 | 0.663 |

| 3490 | IGFBP7 | Insulin like growth factor binding protein 7 | 4.1039 | 0.0369 | 0.663 |

| 54492 | NEURL1B | Neuralized E3 ubiquitin protein ligase 1B | 3.8487 | 0.0083 | 0.663 |

| 301 | ANXA1 | Annexin A1 | 3.811 | 0.0242 | 0.663 |

| 10631 | POSTN | Periostin, osteoblast specific factor | 3.7339 | 0.0224 | 0.663 |

| 79772 | MCTP1 | Multiple C2 domains, transmembrane 1 | 3.6779 | 0.0247 | 0.663 |

| 3486 | IGFBP3 | Insulin like growth factor binding protein 3 | 3.4581 | 0.0304 | 0.663 |

| 5327 | PLAT | Plasminogen activator, tissue | 3.288 | 0.0023 | 0.663 |

| 26353 | HSPB8 | Heat shock protein family B (small) member 8 | 3.2012 | 0.0416 | 0.663 |

Table IX.

Top 20 upregulated genes in the tumor of gallbladder cancer.

| Entrez accession no. | Gene symbol | Gene name | Fold-change | P-value | False discovery rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1048 | CEACAM5 | Carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule 5 | 143.4154524 | 2.06062×10−5 | 0.0894515 |

| 10562 | OLFM4 | Olfactomedin 4 | 90.22299879 | 3.89271×10−5 | 0.0960529 |

| 7020 | TFAP2A | Transcription factor AP-2 α (activating enhancer binding protein 2 α) | 18.24994233 | 3.9829×10−4 | 0.1609015 |

| 1015 | CDH17 | Cadherin 17, LI cadherin (liver-intestine) | 16.14818371 | 1.31492×10−3 | 0.1871078 |

| 10451 | VAV3 | VAV guanine nucleotide exchange factor 3 | 16.0872594 | 7.651281×10−3 | 0.2974407 |

| 1604 | CD55 | CD55 molecule, decay accelerating factor for complement (Cromer blood group) | 14.25260113 | 3.93845×10−6 | 0.0512905 |

| 1373 | CPS1 | Carbamoyl-phosphate synthase 1 | 14.14519343 | 2.998467×10−2 | 0.3979446 |

| 3872 | KRT17 | Keratin 17, type I | 11.21846461 | 2.5881794×10−2 | 0.3854011 |

| 5268 | SERPINB5 | Serpin peptidase inhibitor, clade B (ovalbumin), member 5 | 11.07304422 | 1.2500212×10−2 | 0.3344667 |

| 9843 | HEPH | Hephaestin | 11.07030706 | 8.947495×10−3 | 0.3090802 |

| 213 | ALB | Albumin | 10.91257754 | 0.034730042 | 0.408424 |

| 3158 | HMGCS2 | 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA synthase 2 (mitochondrial) | 10.74010853 | 6.900844×10−3 | 0.2884597 |

| 63928 | CHP2 | Calcineurin-like EF-hand protein 2 | 7.987754539 | 1.5774911×10−2 | 0.3509474 |

| 7031 | TFF1 | Trefoil factor 1 | 7.9601374 | 0.017823277 | 0.3616271 |

| 11074 | TRIM31 | Tripartite motif containing 31 | 7.589614806 | 1.280721×10−3 | 0.1871078 |

| 23213 | SULF1 | Sulfatase 1 | 7.505284011 | 2.8219398×10−2 | 0.3929094 |

| 3216 | HOXB6 | Homeobox B6 | 7.355635549 | 1.101194×10−3 | 0.1861479 |

| 84419 | C15orf48 | Chromosome 15 open reading frame 48 | 7.266966891 | 3.1186816×10−2 | 0.4004668 |

| 2982 | GUCY1A3 | Guanylate cyclase 1, soluble, α3 | 7.041356237 | 1.9708261×10−2 | 0.3677601 |

| 8329 | HIST1H2AI | Histone cluster 1, h2ai | 6.935644729 | 7.41761×10−4 | 0.1737322 |

Function enrichment analysis

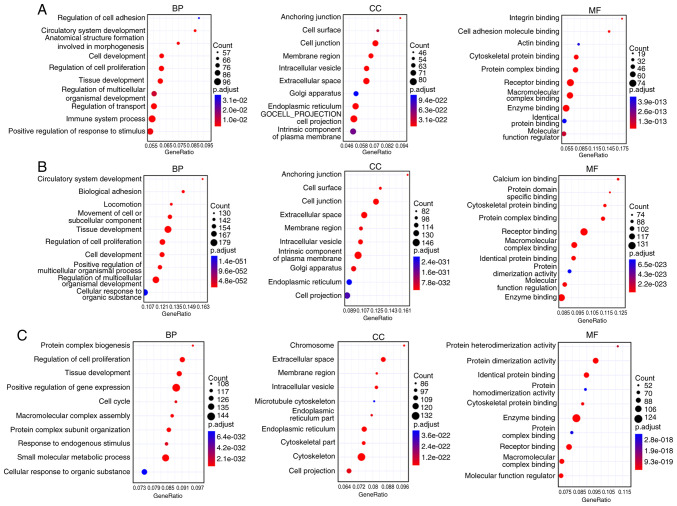

To better understand the biological pathways that were affected in the gallbladder walls of cholesterol polyps, gallbladder adenoma and gallbladder cancer, GO analysis was conducted on the DEGs. Fig. 4A shows that the GO terms that experienced the most significant enrichment of comparison A was the BP ‘Immune system process’, MF ‘Integrin binding’ and the CC ‘Anchoring junction’. Fig. 4B shows that the DEGs of gallbladder walls in cholesterol polyps vs. gallbladder adenoma participate in a number of GO pathways, the number of DEGs with the highest count had roles in the BP ‘Tissue development’, the CC ‘Cell junction’ and the MF ‘Receptor binding’. Fig. 4C demonstrates that the number of DEGs of the tumor tissues in cholesterol polyps compared with gallbladder adenoma had the highest count in the BP ‘Positive regulation of gene expression’, the CC ‘Cytoskeleton’ and the MF ‘Enzyme binding’.

Figure 4.

GO function enrichment analysis of all the compared groups. (A) GO function enrichment analysis of (A) comparison I, II, III and IV, (B) comparison V and (C) comparison VI. GO, Gene Ontology; BP, biological process; CC, cellular component; MF, molecular function. Red represents upregulated genes and green represents downregulated genes. Comparison I: Gallbladder wall of gallstone vs. gallbladder wall of cholesterol polyps; Comparison II: Gallbladder wall of gallstone vs. gallbladder wall of gallbladder adenoma; Comparison III: Gallbladder wall of gallstone vs. gallbladder wall of gallbladder cancer; Comparison IV: Gallbladder wall of cholesterol polyps vs. gallbladder wall of gallbladder adenoma; Comparison V: Gallbladder wall of gallbladder adenoma vs. gallbladder wall of gallbladder cancer; Comparison VI: Tumor wall of gallbladder adenoma vs. tumor wall of gallbladder cancer.

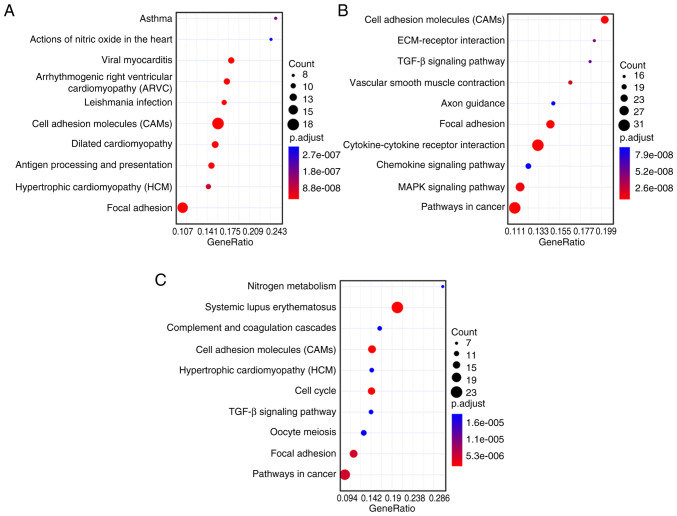

KEGG pathway enrichment analysis

The biological pathways that were enriched by DEGs were also analyzed with KEGG. Fig. 5A shows that the most significantly enriched pathways in the gallbladder walls of cholesterol polyps, gallbladder adenoma and gallbladder cancer compared with normal groups was ‘cell adhesion molecules (CAMs)’. Fig. 5B shows that the most significantly enriched pathway with DEGs in the gallbladder walls of gallbladder adenoma vs. gallbladder cancer was ‘Cell adhesion molecules (CAMs)’. Fig. 5C indicates that the most significantly enriched pathway in the tumor tissues of gallbladder adenoma vs. gallbladder cancer was the ‘Systemic lupus erythematosus’.

Figure 5.

Top 10 pathways in KEGG pathway analysis of all compared groups. op 10 pathways in KEGG pathway analysis of (A) comparison I, II, III and IV, (B) comparison V and (C) comparison VI. KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; ECM, extracellular matrix; TGF, transforming growth factor. Comparison I: Gallbladder wall of gallstone vs. gallbladder wall of cholesterol polyps; Comparison II: Gallbladder wall of gallstone vs. gallbladder wall of gallbladder adenoma; Comparison III: Gallbladder wall of gallstone vs. gallbladder wall of gallbladder cancer; Comparison IV: Gallbladder wall of cholesterol polyps vs. gallbladder wall of gallbladder adenoma; Comparison V: Gallbladder wall of gallbladder adenoma vs. gallbladder wall of gallbladder cancer; Comparison VI: Tumor wall of gallbladder adenoma vs. tumor wall of gallbladder cancer.

Validation of key genes in gallbladder cancer

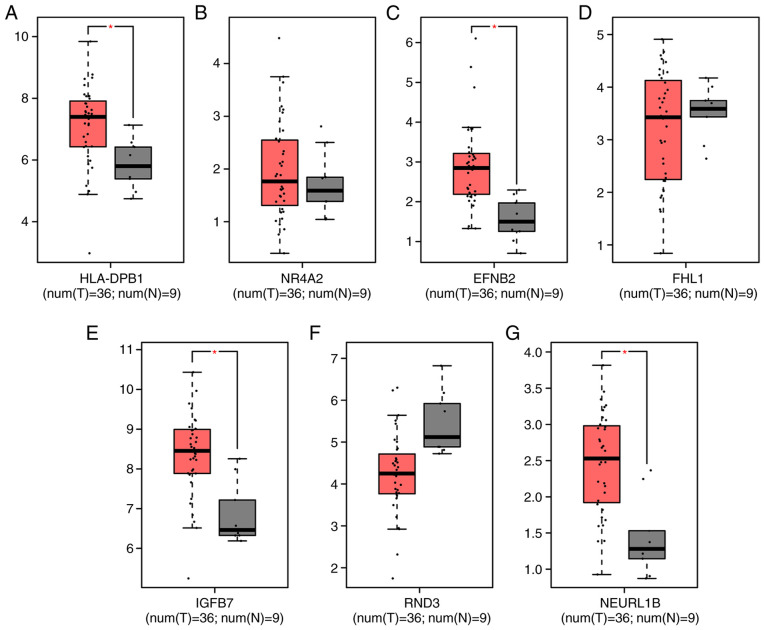

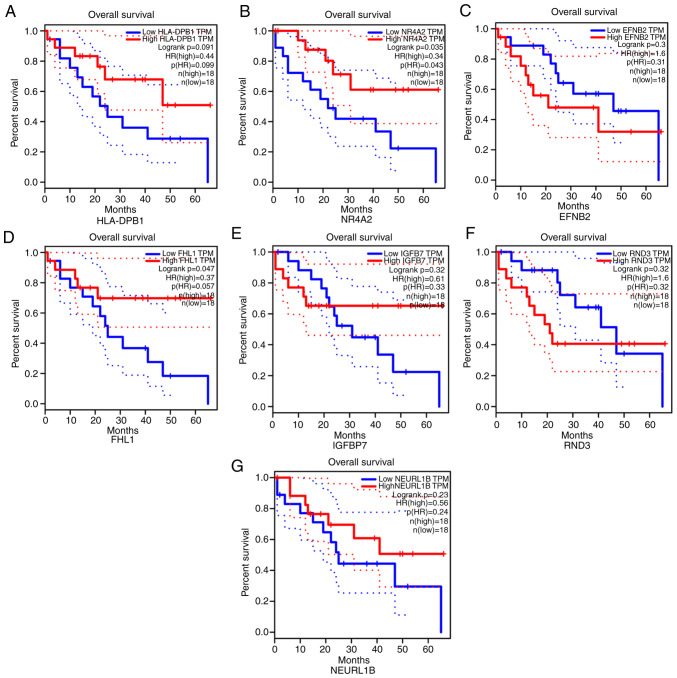

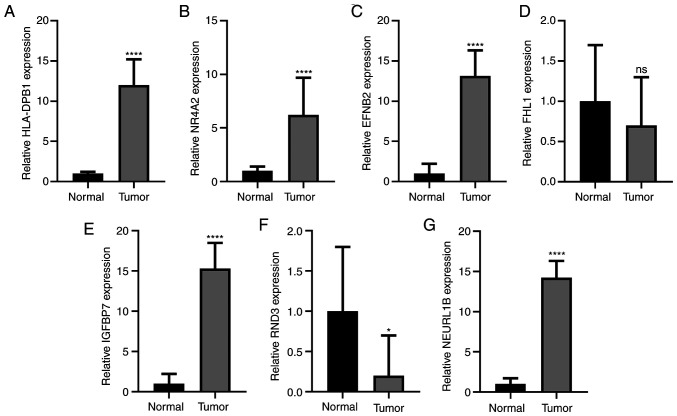

Among the top 20 DEGs in the gallbladder wall and tumor of gallbladder cancer, seven novel DEGs, including HLA-DPB1 (Fig. 6A), NR4A2 (Fig. 6B), EFNB2 (Fig. 6C), FHL1 (Fig. 6D), IGFBP7 (Fig. 6E), RND3 (Fig. 6F) and NEURL1B (Fig. 6G) for gallbladder cancer were validated using GEPIA. HLA-DPB1, EFNB2, IGFBP7 and NEURL1B had a significantly higher expression in gallbladder cancer tissues compared with normal tissues. The prognostic value of these DEGs were further analyzed. There was no significant difference between low HLA-DPB1 expression and prognosis of gallbladder cancer (Fig. 7A). The low expression of NR4A2 (Fig. 7B) indicated poorer OS for patients with gallbladder cancer. No significant difference was found between patients with low EFNB2 expression and those with high EFNB2 expression (Fig. 7C). Low FHL1 expression predicted significantly less favorable OS (Fig. 7D). There was no significant difference observed for different expression levels of IGFBP7 (Fig. 7E), RND3 (Fig. 7F) and NEURL1B (Fig. 7G). Therefore, the data presented here indicated that only NR4A2 and FHL1 could represent potential prognostic markers for patients with gallbladder cancer. Following validation using RT-qPCR, HLA-DPB1 (Fig. 8A), NR4A2 (Fig. 8B) and EFNB2 (Fig. 8C) had significantly higher expression levels in gallbladder cancer tissues compared with normal tissues. However, there was no statistical difference in FHL1 expression between gallbladder cancer tissues and normal tissues (Fig. 8D). Moreover, high IGFBP7 expression was determined in gallbladder cancer tissues compared with normal tissues (Fig. 8E). As shown in Fig. 8F, RND3 mRNA expression was significantly decreased in gallbladder cancer tissues compared with normal tissues. A significantly higher expression level of NEURL1B was also detected in gallbladder cancer tissues compared with normal tissues (Fig. 8G).

Figure 6.

Validation of key genes in gallbladder cancer tissues using Gene Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis. (A) HLA-DPB1, (B) NR4A2, (C) EFNB2, (D) FHL1, (E) IGFBP7, (F) RND3 and (G) NEURL1B. HLA-DPB1, Major Histocompatibility Complex, Class II, DP β1; NR4A2, nuclear receptor subfamily 4 group a member 2; EFNB2, ephrin B2; FHL1, four and a half LIM domains 1; IGFBP7, insulin like growth factor binding protein 7; RND3, Rho family GTPase 3; NEURL1B, neutralized E3 ubiquitin protein ligase 1B; T, tumor; N, normal. *P<0.05.

Figure 7.

Overall survival analysis of key genes in gallbladder cancer. (A) HLA-DPB1, (B) NR4A2, (C) EFNB2, (D) FHL1, (E) IGFBP7, (F) RND3 and (G) NEURL1B. Red represents high expression and blue represents low expression. HLA-DPB1, Major Histocompatibility Complex, Class II, DP β1; NR4A2, nuclear receptor subfamily 4 group a member 2; EFNB2, ephrin B2; FHL1, four and a half LIM domains 1; IGFBP7, insulin like growth factor binding protein 7; RND3, Rho family GTPase 3; NEURL1B, neutralized E3 ubiquitin protein ligase 1B; HR, hazard ratio.

Figure 8.

Validation of key genes in gallbladder cancer tissues using a reverse transcription-quantitative PCR assay. (A) HLA-DPB1, (B) NR4A2, (C) EFNB2, (D) FHL1, (E) IGFBP7, (F) RND3 and (G) NEURL1B. *P<0.05; and ****P<0.0001; ns, not significant; HLA-DPB1, Major Histocompatibility Complex, Class II, DP β1; NR4A2, nuclear receptor subfamily 4 group a member 2; EFNB2, ephrin B2; FHL1, four and a half LIM domains 1; IGFBP7, insulin like growth factor binding protein 7; RND3, Rho family GTPase 3; NEURL1B, neutralized E3 ubiquitin protein ligase 1B.

Discussion

Gallbladder disease is one of the most common causes of upper abdominal pain (15). It is critical to focus on gallbladder diseases due to the potential for malignant degeneration of any gallbladder lesion (15). Gallbladder adenomas and primary adenocarcinomas have been identified as the most common benign and malignant tumors, respectively (16). Nevertheless, efforts have been put into elucidating the pathophysiological mechanisms leading to the development of gallbladder cancer, however, most of these mechanisms remain unknown. Therefore, it is crucial to disclose the molecular mechanisms of gallbladder cancer to promote the development of new cancer biomarkers and appropriate treatment strategies.

Different from other microarray studies, in the present study, the microarrays were comprehensively analyzed (17–19). Firstly, eight differentially expressed upregulated genes were found, which included LOC101928168, HMGCS2, SCGN, CHN2, XK, MUC6, PLPP5 and HSPH1 both in cholesterol polyps and gallbladder adenoma from gallbladder walls. Secondly, 14 common DEGs were identified in the gallbladder walls of gallbladder cancer and gallbladder adenoma. It is important to distinguish benign and malignant gallbladder adenoma due to the poor diagnosis of gallbladder cancer. T-Box Transcription Factor 3, Tsukushi, Small Leucine Rich Proteoglycan, Stearoyl-CoA Desaturase (SCD), NOVA Alternative Splicing Regulator 1 and 6-Phosphofructo-2-Kinase/Fructose-2,6-Biphosphatase 3 were downregulated in the gallbladder wall of gallbladder cancer and gallbladder adenoma; EDN1, MS4A8, ALB, MSLN, CTSV, BAG1, LOC100507412, MCOLN3 and ZKSCAN1 were upregulated in the gallbladder wall of gallbladder cancer and gallbladder adenoma. Thirdly, 273 upregulated genes were expressed in the gallbladder wall of gallbladder adenoma. Fourthly, the 20 most significantly DEGs that were upregulated in the gallbladder wall of gallbladder cancer were identified including KRT20, STMN2, DKK1, KCNS3, IL18, MADCAM1, COL13A1, TPM4, SLITRK6, SCD5, C8orf4, VMP1, MIR21, FERMT1, DOK5, FJX1, EPHA4, EDN3, KLF6 and C1orf186. Among them, DKK1 is known to regulate tumor angiogenesis, which is essential for tumor invasive growth and metastasis (20). IL18 has been reported to be a candidate cytokine that may provide a new insight into the development of next generation cancer immunotherapy (21). Desaturated fatty acids are essential for tumor cell survival, and SCD5 may represent a viable target for the development of novel agents for cancer treatment (22), which could become a candidate for the treatment of gallbladder cancer. KLF6 is a member of the Kruppel-like family of zinc finger transcription factors, which has been identified as a mutated tumor inhibitor in selective human cancer types, but not gallbladder cancer (23).

A total of 182 upregulated DEGs in the gallbladder walls of gallbladder adenoma were obtained and compared with that of cholesterol polyps. The top 20 most significantly expressed genes included MFAP5, CILP, WISP2, MT1G, MT1H, EFEMP1, UGT2B7, IGFBP6, OLFM4, MT1F, ERAP2, CYP1A1, ZNF761, BST1, AIM1L, SLCO4A1-AS1, CD209, CIART, UGT2B11 and FBLN2. The overexpression of CCN5/WISP2 in adipose tissue has previously been secreted and circulated in the blood in a transgenic mouse model, which suggests that WISP2 could become a biomarker in blood for gallbladder adenoma and cholesterol polyps (24). The gene expression of MT1G, MT1H and MT1F in human peripheral blood lymphocytes can be used as potential biomarkers for cadmium exposure (25). Cadmium exposure could contribute to the development of gallbladder cancer (26). EFEMP1 expression accumulates angiogenesis and accelerates the growth of cervical cancer in vivo (27). Patients with UGT2B7*1/*2 genotypes, UGT2B7 genetic variation are at risk for suboptimal immune recovery due to significant long-term autologous induction (28). The expression of IGFBP-6 in vascular endothelial cells is upregulated by hypoxia and IGFBP-6 suppresses angiogenesis in vitro and in vivo (29), but this has not been reported in the context of gallbladder cancer. OLFM4 expression is associated with cancer differentiation, stage, metastasis and prognosis in a variety of cancer types, such as breast cancer, esophageal adenocarcinoma and gastrointestinal cancer, suggesting that it has underlying clinical value as an early cancer biomarker or therapeutic target (30). CYP1A1/1A2 isoenzymes are involved in EROD activity in blood lymphocytes (31); however, there is currently no previous report on the functions of this gene in gallbladder cancer. The production of extracellular cADPR, catalyzed by BST-1, followed by concentrating the uptake of cyclic nucleotides by hemopoietic progenitors, may be physiologically relevant in normal hematopoiesis (32), but its function in gallbladder cancer remains unknown. CD209 has been identified to present on monocyte-derived DCs, a cell adjuvant for cancer immunotherapy (33). FBLN2 is a novel gene associated with hypertension (34).

The top 20 upregulated genes were expressed both in tumors and gallbladder walls of gallbladder cancer, which included CTGF, HLA-DPB1, ID3, ID4, COL4A1, NR4A2, GEM, EFNB2, ID1, CXCL1, RND3, FHL1, IGFBP7, NEURL1B, ANXA1, POSTN, MCTP1, IGFBP3, PLAT and HSPB8. The study focused on whether these genes expression levels could be assessed using blood or bile. CTGF could play an important role in the inflammation of gallbladder cancer (35). Therefore, CTGF has the potential to become a future biomarker for gallbladder cancer, circulating in the blood and bile. It has been revealed that the dynamic changes of growth centers and plasma cell differentiation are determined by ID3 and E protein activity (35). Following validation using RT-qPCR, the genes HLA-DPB1, NR4A2, EFNB2, IGFBP7 and NEURL1B were found to be highly expressed in gallbladder cancer. RND3 was significantly decreased in gallbladder cancer. HLA-DPB1, NR4A2 and FHL1 could be underlying prognostic markers for gallbladder cancer.

In the present study, a transcriptome profile was comprehensively analyzed enabling the identification of DEGs in gallbladder cancer, based on an annotation analysis of microarray studies. The present findings could provide a novel understanding on the tumorigenesis and development of gallbladder cancer.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- DEGs

differentially expressed genes

- GO

Gene Ontology

- KEGG

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

- aRNA

amplified RNA

- FC

fold-change

Funding

This work was funded by Natural Science Foundation of Liaoning Province (grant no. 2020-BS-283).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

CG conceived and designed the study. XZ and XN conducted most of the experiments and data analysis and wrote the manuscript. BZ and LC participated in acquiring data and helped draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee of The First Affiliated Hospital of China Medical University (2018075). All patients who participated in the study signed written informed consent.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Sicklick JK, Fanta PT, Shimabukuro K, Kurzrock R. Genomics of gallbladder cancer: The case for biomarker-driven clinical trial design. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2016;35:263–275. doi: 10.1007/s10555-016-9602-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chandra V, Kim JJ, Mittal B, Rai R. MicroRNA aberrations: An emerging field for gallbladder cancer management. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:1787–1799. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i5.1787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim YT, Kim J, Jang YH, Lee WJ, Ryu JK, Park YK, Kim SW, Kim WH, Yoon YB, Kim CY. Genetic alterations in gallbladder adenoma, dysplasia and carcinoma. Cancer Lett. 2001;169:59–68. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3835(01)00562-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Itoi T, Watanabe H, Ajioka Y, Oohashi Y, Takel K, Nishikura K, Nakamura Y, Horil A, Saito T. APC, K-ras codon 12 mutations and p53 gene expression in carcinoma and adenoma of the gall-bladder suggest two genetic pathways in gallbladder carcinogenesis. Pathol Int. 1996;46:333–340. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.1996.tb03618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee SH, Lee DS, You IY, Jeon WJ, Park SM, Youn SJ, Choi JW, Sung R. Histopathologic analysis of adenoma and adenoma-related lesions of the gallbladder. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2010;55:119–126. doi: 10.4166/kjg.2010.55.2.119. (In Korean) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu MC, Jiang L, Hong HJ, Meng ZW, Du Q, Zhou LY, She FF, Chen YL. Serum vascular endothelial growth factors C and D as forecast tools for patients with gallbladder carcinoma. Tumour Biol. 2015;36:6305–6312. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-3316-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choi JH, Yun JW, Kim YS, Lee EA, Hwang ST, Cho YK, Kim HJ, Park JH, Park DI, Sohn CI, et al. Pre-operative predictive factors for gallbladder cholesterol polyps using conventional diagnostic imaging. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:6831–6834. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.6831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhao MF, Huang P, Ge CL, Sun T, Ma ZG, Ye FF. Conjugated bile acids in gallbladder bile and serum as potential biomarkers for cholesterol polyps and adenomatous polyps. Int J Biol Markers. 2016;31:e73–e79. doi: 10.5301/jbm.5000173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ritchie ME, Phipson B, Wu D, Hu Y, Law CW, Shi W, Smyth GK. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:e47. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, Mukherjee S, Ebert BL, Gillette MA, Paulovich A, Pomeroy SL, Golub TR, Lander ES, Mesirov JP. Gene set enrichment analysis: A knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:15545–15550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kanehisa M, Goto S, Sato Y, Furumichi M, Tanabe M. KEGG for integration and interpretation of large-scale molecular data sets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40((Database Issue)):D109–D114. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tang Z, Li C, Kang B, Gao G, Li C, Zhang Z. GEPIA: A web server for cancer and normal gene expression profiling and interactive analyses. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45W:W98–W102. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2013. R Core Team: R: A language and environment for statistical computing. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rodriguez S, Gaunt TR, Guo Y, Zheng J, Barnes MR, Tang W, Danish F, Johnson A, Castillo BA, Li YR, et al. Lipids, obesity and gallbladder disease in women: Insights from genetic studies using the cardiovascular gene-centric 50K SNP array. Eur J Hum Genet. 2016;24:106–112. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2015.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mellnick VM, Menias CO, Sandrasegaran K, Hara AK, Kielar AZ, Brunt EM, Doyle MB, Dahiya N, Elsayes KM. Polypoid lesions of the gallbladder: Disease spectrum with pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2015;5:387–399. doi: 10.1148/rg.352140095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang F, Wang R, Li Q, Qu X, Hao Y, Yang J, Zhao H, Wang Q, Li G, Zhang F, et al. A transcriptome profile in hepatocellular carcinomas based on integrated analysis of microarray studies. Diagn Pathol. 2017;12:4. doi: 10.1186/s13000-016-0596-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meng LZ, Fang JG, Sun JW, Yang F, Wei YX. Aberrant expression profile of long noncoding RNA in human sinonasal squamous cell carcinoma by microarray analysis. Biomed Res Int. 2016;2016:1095710. doi: 10.1155/2016/1095710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu L, Liu Y, Liu C, Zhang Z, Du Y, Zhao H. Analysis of gene expression profile identifies potential biomarkers for atherosclerosis. Mol Med Rep. 2016;14:3052–3058. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2016.5650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Park H, Jung HY, Choi HJ, Kim DY, Yoo JY, Yun CO, Min JK, Kim YM, Kwon YG. Distinct roles of DKK1 and DKK2 in tumor angiogenesis. Angiogenesis. 2014;17:221–234. doi: 10.1007/s10456-013-9390-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ma Z, Li W, Yoshiya S, Xu Y, Hata M, El-Darawish Y, Markova T, Yamanishi K, Yamanishi H, Tahara H, et al. Augmentation of immune checkpoint cancer immunotherapy with IL18. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22:2969–2980. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roongta UV, Pabalan JG, Wang X, Ryseck RP, Fargnoli J, Henley BJ, Yang WP, Zhu J, Madireddi MT, Lawrence RM, et al. Cancer cell dependence on unsaturated fatty acids implicates stearoyl-CoA desaturase as a target for cancer therapy. Mol Cancer Res. 2011;9:1551–1561. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-11-0126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yin D, Komatsu N, Miller CW, Chumakov AM, Marschesky A, McKenna R, Black KL, Koeffler HP. KLF6: mutational analysis and effect on cancer cell proliferation. Int J Oncol. 2007;30:65–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grünberg JR, Elvin J, Paul A, Hedjazifar S, Hammarstedt A, Smith U. CCN5/WISP2 and metabolic diseases. J Cell Commun Signal. 2018;12:309–318. doi: 10.1007/s12079-017-0437-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chang XL, Jin TY, Zhou YF. Metallothionein 1 isoform gene expression induced by cadmium in human peripheral blood lymphocytes. Biomed Environ Sci. 2006;19:104–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee MH, Gao YT, Huang YH, McGee EE, Lam T, Wang B, Shen MC, Rashid A, Pfeiffer RM, Hsing AW, Koshiol J. A metallomic approach to assess associations of serum metal levels with gallstones and gallbladder cancer. Hepatology. 2020;71:917–928. doi: 10.1002/hep.30861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.En-lin S, Sheng-guo C, Hua-qiao W. The expression of EFEMP1 in cervical carcinoma and its relationship with prognosis. Gynecol Oncol. 2010;117:417–422. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2009.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Habtewold A, Amogne W, Makonnen E, Yimer G, Riedel KD, Ueda N, Worku A, Haefeli WE, Lindquist L, Aderaye G, et al. Long-term effect of efavirenz autoinduction on plasma/peripheral blood mononuclear cell drug exposure and CD4 count is influenced by UGT2B7 and CYP2B6 genotypes among HIV patients. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66:2350–2361. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang C, Lu L, Li Y, Wang X, Zhou J, Liu Y, Fu P, Gallicchio MA, Bach LA, Duan C. IGF binding protein-6 expression in vascular endothelial cells is induced by hypoxia and plays a negative role in tumor angiogenesis. Int J Cancer. 2012;130:2003–2012. doi: 10.1002/ijc.26201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu W, Rodgers GP. Olfactomedin 4 expression and functions in innate immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2016;35:201–212. doi: 10.1007/s10555-016-9624-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dey A, Parmar D, Dayal M, Dhawan A, Seth PK. Cytochrome P450 1A1 (CYP1A1) in blood lymphocytes evidence for catalytic activity and mRNA expression. Life Sci. 2001;69:383–393. doi: 10.1016/S0024-3205(01)01130-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Podestà M, Benvenuto F, Pitto A, Figari O, Bacigalupo A, Bruzzone S, Guida L, Franco L, Paleari L, Bodrato N, et al. Concentrative uptake of cyclic ADP-ribose generated by BST-1+ stroma stimulates proliferation of human hematopoietic progenitors. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:5343–5349. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408085200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Osugi Y, Vuckovic S, Hart DN. Myeloid blood CD11c(+) dendritic cells and monocyte-derived dendritic cells differ in their ability to stimulate T lymphocytes. Blood. 2002;100:2858–2866. doi: 10.1182/blood.V100.8.2858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vallvé JC, Serra N, Zalba G, Fortuño A, Beloqui O, Ferre R, Ribalta J, Masana L. Two variants in the fibulin2 gene are associated with lower systolic blood pressure and decreased risk of hypertension. PLoS One. 2012;7:e43051. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gloury R, Zotos D, Zuidscherwoude M, Masson F, Liao Y, Hasbold J, Corcoran LM, Hodgkin PD, Belz GT, Shi W, et al. Dynamic changes in Id3 and E-protein activity orchestrate germinal center and plasma cell development. J Exp Med. 2016;213:1095–1111. doi: 10.1084/jem.20152003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.