High-dose nitric oxide is a novel treatment associated with improved oxygenation and decreased tachypnea in pregnant patients with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).

Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Rescue therapies to treat or prevent progression of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) hypoxic respiratory failure in pregnant patients are lacking.

METHOD:

To treat pregnant patients meeting criteria for severe or critical COVID-19 with high-dose (160–200 ppm) nitric oxide by mask twice daily and report on their clinical response.

EXPERIENCE:

Six pregnant patients were admitted with severe or critical COVID-19 at Massachusetts General Hospital from April to June 2020 and received inhalational nitric oxide therapy. All patients tested positive for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection. A total of 39 treatments was administered. An improvement in cardiopulmonary function was observed after commencing nitric oxide gas, as evidenced by an increase in systemic oxygenation in each administration session among those with evidence of baseline hypoxemia and reduction of tachypnea in all patients in each session. Three patients delivered a total of four neonates during hospitalization. At 28-day follow-up, all three patients were home and their newborns were in good condition. Three of the six patients remain pregnant after hospital discharge. Five patients had two negative test results on nasopharyngeal swab for SARS-CoV-2 within 28 days from admission.

CONCLUSION:

Nitric oxide at 160–200 ppm is easy to use, appears to be well tolerated, and might be of benefit in pregnant patients with COVID-19 with hypoxic respiratory failure.

We report the treatment of pregnant patients with severe or critical coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) with nitric oxide gas. Nitric oxide is a therapeutic gas that typically is delivered at 10–80 ppm to produce selective pulmonary vasodilation and improve arterial oxygenation. More recently, nitric oxide at a high dose (160–200 ppm) has demonstrated broad antimicrobial activity on bacteria and viruses such as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV-1), the virus that caused severe acute respiratory syndrome in 2003.1–3

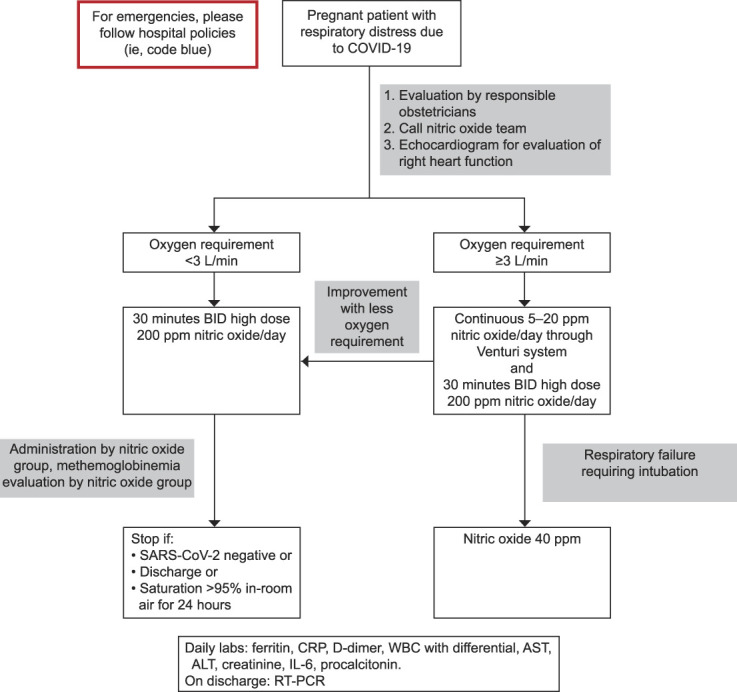

Owing to the efficacy of inhaled nitric oxide in adults with other causes of acute respiratory distress syndrome and pulmonary hypertension with a relatively safe therapeutic profile, we formed an interdisciplinary team to provide nitric oxide therapy to patients admitted to our hospital with severe or critical COVID-19 respiratory symptoms who were rapidly deteriorating (the nitric oxide treatment protocol is shown in Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Clinical flow chart for nitric oxide therapy in pregnant patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) at Massachusetts General Hospital. COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; BID, twice a day; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; CRP, c-reactive protein; WBC, white blood cells; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; IL-6, interleukin-6; RT-PCR, real time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction.

Safaee Fakhr. Nitric Oxide in Pregnant Patients With COVID-19. Obstet Gynecol 2020.

METHOD

Patients were classified into two categories (severe or critical) according to the severity of respiratory, circulatory, and multiple organ involvement, as reported in Appendix 1, available online at http://links.lww.com/AOG/C61.4,5 The Institutional Review Board approved collection of the data from the Massachusetts General Hospital medical records.

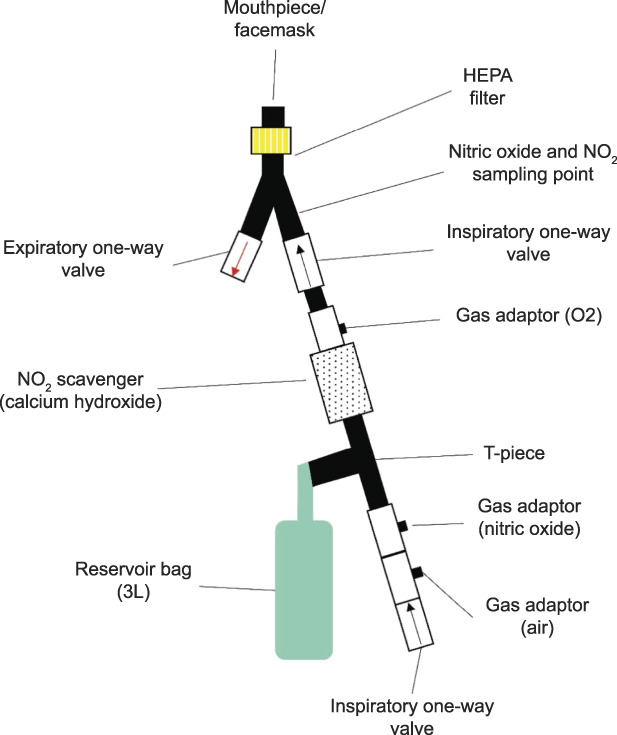

The nitric oxide gas was provided to spontaneously breathing, awake patients using a snug-fitting mask connected to the breathing circuit (Fig. 2).6 The nitric oxide mixture was delivered at a concentration between 160 and 200 ppm at the desired FiO2 concentration. Nitrogen dioxide concentrations had been measured previously using the same breathing circuit and a test lung in the laboratory and were maintained at concentrations below 1.5 ppm. Nitrogen dioxide is a toxic free radical gas derived from the reaction of nitric oxide with oxygen that can cause, at high concentration, lung damage through direct epithelial cells injury.7 Treatment sessions lasted between 30 minutes and 1 hour. Before, during, and after each treatment session, SpO2, methemoglobin saturation (%), heart rate, and noninvasive blood pressure were monitored continuously. During nitric oxide breathing, methemoglobin is formed by oxidation of iron (from Fe2+ to Fe3+). Ferric hemoglobin (MetHb [Fe3+]) is unable to transport oxygen. To avoid tissue hypoxia in respiratory failure, our goal was to maintain methemoglobin below 5%.

Fig. 2. Nitric oxide delivery system. Schematic representation of the NO delivery system for spontaneous breathing patients. HEPA, high-efficiency particulate air. Modified from Gianni S, Safaee Fakhr B, Araujo Morais CC, Di Fenza R, Larson G, Pinciroli R, et al. Nitric oxide gas inhalation to prevent COVID-2019 in healthcare providers. Preprint. Posted online April 11, 2020. medRxiv. doi: 10.1101/2020.04.05.20054544. Used with permission of the author.

Safaee Fakhr. Nitric Oxide in Pregnant Patients With COVID-19. Obstet Gynecol 2020.

Data on the safety and efficacy of nitric oxide administration (SpO2, heart rate, blood pressure, and methemoglobin) were reported in each patient's chart on completion of each session and are summarized as “baseline” (before starting nitric oxide delivery), “iNO” (approximately 15 minutes into the nitric oxide session), and “post-iNO” (5–10 minutes after nitric oxide delivery). Data are presented as the median and interquartile range or median (minimum and maximum values). All statistical analysis was conducted using Prism 8.4.2.

EXPERIENCE

Six pregnant women with severe or critical COVID-19 were admitted to Massachusetts General Hospital from April 1 to June 11, 2020. Nitric oxide inhalation was started in all patients as rescue therapy on request by the treating clinical team within 48 hours after admission. Patient characteristics are shown in Appendix 1 (http://links.lww.com/AOG/C61). During the first 48 hours of hospitalization, all six patients required supplemental oxygen; four were treated in the intensive care unit for 3–17 days, and two were intubated for 30 hours–14 days. During mechanical ventilation, the intermittent high-concentration nitric oxide gas was suspended and continuous low-dose (less than 40 ppm) inhaled nitric oxide was delivered by the ventilator at the discretion of the intensive care unit team as per standard clinical protocols. A high concentration of nitric oxide gas treatments resumed after extubation. All patients were discharged home in stable condition (hospital length of 2–25 days) and were shown to be independent in their daily activities based on the Katz Index of Independence in Activities of Daily Living (Appendix 2, available online at http://links.lww.com/AOG/C61) at the 28-day follow-up.

A total of 39 treatments of 160–200 ppm of nitric oxide gas inhalation were delivered to the six patients (ranging from 2 to 18 treatments per patient). Thirteen of the 26 treatments administered to patient 1, patient 2, and patient 3 occurred when baseline hypoxia was present (SpO2%/FiO2% ratio<315 is equal to [PaO2]/FiO2<300 mmHg).8 Systemic oxygenation improved immediately during the delivery of nitric oxide in each of these treatment sessions (Appendix 3A, available online at http://links.lww.com/AOG/C61). Nitric oxide inhalation was associated with rapid subjective relief of shortness of breath in all patients, and respiratory rates decreased (Appendix 3B, available online at http://links.lww.com/AOG/C61), returning to being tachypneic 3 hours after the treatment (ranging from 0 to 16 hours after the treatment). Heart rate and mean systemic arterial pressure were unchanged compared with baseline (Appendix 3C and D, available online at http://links.lww.com/AOG/C61).

By the 28th day after initial hospitalization, five of six patients had tested negative twice for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) by real time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction from a nasopharyngeal swab, and one patient remained positive (Appendix 1, http://links.lww.com/AOG/C61). C-reactive protein levels were measured daily in all patients, and levels decreased in association with the initiation of nitric oxide (Appendix 4A, available online at http://links.lww.com/AOG/C61). In patient 6, initiation of nitric oxide therapy was associated with decline in C-reactive protein and interleukin-6 levels and a slow improvement in absolute lymphocyte counts (Appendix 4B, available online at http://links.lww.com/AOG/C61).

Inhalation of nitric oxide was well tolerated in all patients. No acute adverse effects were observed in any patient. Methemoglobin (baseline 0.9%, interquartile range 0.5–1.3%) was measured continuously and peaked at 2.5% (interquartile range 2.0–3.0%).

During hospitalization, patients 4 and 5 received inhaled nitric oxide (5–20 ppm) and supplemental oxygen during delivery to maintain an SpO2 level above 95%. Patient 4 delivered vaginally, and patient 5 delivered by cesarean.

Patient 2 required intubation for acute respiratory distress syndrome and hemodynamic shock and delivered twins by cesarean under general anesthesia at 30 weeks of gestation. She developed acute kidney injury (stage 2) the day after the emergent cesarean delivery (creatinine 1.12 mg/dL, with a baseline level of 0.51 mg/dL), and her kidney function returned to baseline value before discharge. Apgar scores were 2, 5, and 6 at 1, 5, and 10 minutes, respectively, for newborn A and 4 and 7 at 1 and 5 minutes, respectively, for newborn B. Birth weights were 1.34 and 1.60 kg, respectively. Both newborns were intubated and received surfactant at delivery and were extubated on day 3. All newborns tested negative on real time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction for SARS-CoV-2 infection after delivery and remained in good condition by day 28 of maternal admission; the twins delivered at 30 weeks of gestation remain in the neonatal intensive care unit owing to prematurity, and the other newborns have been discharged home. Of the three women who remained pregnant at discharge, two have delivered without complications, although one had a late preterm birth at 36 weeks of gestation.

DISCUSSION

The treatment of severe or critical COVID-19 is difficult and not well studied. Although this is a preliminary report on the use of nitric oxide gas from a small cohort of spontaneously breathing pregnant patients with COVID-19, there are several plausible reasons for using nitric oxide in this population, as graphically illustrated in Appendix 5 (available online at http://links.lww.com/AOG/C61) together with previous study on adults9 and newborns,10 including a reasonable safety profile; potential antiviral, antiinflammatory, and mild bronchodilatory action; and selective pulmonary vasodilation, which may improve maternal and fetal oxygenation. This study is limited by the lack of fetal parameters during nitric oxide treatments, because these data were not recorded. Acute kidney injury is a known complication of nitric oxide treatment11; one patient developed acute kidney injury, though a causal relationship between development of acute kidney injury and administration of nitric oxide cannot be derived from our data, and the patient had clinical events that may have contributed to the acute kidney injury, independent of nitric oxide treatments. Future patients treated with high-dose nitric oxide should be monitored for the development of acute kidney injury.

Inhaled nitric oxide gas has been used in pregnancy and has not been associated with teratogenicity.12,13 No adverse events were reported in the medical record or by the clinicians providing high-dose nitric oxide to the patients (L.B., A.J.K., W.H.B., R.W.C., F.I., M.G.C.). Transcutaneous methemoglobin levels peaked on average at 2.5%. Our decision to use high-concentration nitric oxide treatments (160–200 ppm) in patients with severe or critical COVID-19 was based on prior reports showing the antibacterial and antiviral effects of nitric oxide.2,14 Specifically, Keyaerts et al show in in vitro studies that nitric oxide released from nitric oxide–donor molecules exerts a direct antiviral effect against SARS-CoV-1.1 The two viruses responsible for the epidemics of 2002–2003 (SARS-CoV-1) and 2019–2020 (SARS-CoV-2) show wide genetic similarities.15 We hypothesize that free-radical nitric oxide gas exerts virucidal action by direct nitrosation16 of critical virion proteins required for infection, replication, and transmission. However, the precise antiviral effects of nitric oxide have yet to be determined.

In summary, high-dose inhaled nitric oxide was well tolerated and was associated with improved oxygenation and respiratory rate for pregnant patients with severe or critical COVID-19. The potential benefits of nitric oxide inhalation therapy to improve outcomes in patients with COVID-19 need to be tested in prospective randomized trials.17

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure Lorenzo Berra: salary support K23-NIH; devices support: iNO Therapeutics LLC, Praxair Inc., Masimo Corp; grant from iNO Therapeutics LLC. Fumito Ichinose: R01 and R21-NIH; consultant: Nihon Kohden Innovation Center; grants from Kyowa Hakko Kirin Pharma, Inc. Robert Kacmarek: consultant: Medtronic. Steffen Wiegand: DFG-WI5162/2-1. Pankaj Arora: grant: K23-NIH. The other authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

This study was supported by the Reginald Jenney Endowment Chair at Harvard Medical School of LB, by LB Sundry Funds at Massachusetts General Hospital, and by laboratory funds of the Anesthesia Center for Critical Care Research of the Department of Anesthesia, Critical Care and Pain Medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital.

Peer reviews and author correspondence are available at http://links.lww.com/AOG/C62.

Each author has confirmed compliance with the journal's requirements for authorship.

Published online ahead-of-print August 26, 2020.

Figure.

No available caption

REFERENCES

- 1.Keyaerts E, Vijgen L, Chen L, Maes P, Hedenstierna G, Van Ranst M. Inhibition of SARS-coronavirus infection in vitro by S-nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine, a nitric oxide donor compound. Int J Infect Dis 2004;8:223–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller CC, Hergott CA, Rohan M, Arsenault-Mehta K, Döring G, Mehta S. Inhaled nitric oxide decreases the bacterial load in a rat model of Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia. J Cyst Fibros 2013;12:817–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bartley BL, Gardner KJ, Spina S, Hurley BP, Campeau D, Berra L, et al. High-dose inhaled nitric oxide as adjunct therapy in cystic fibrosis targeting Burkholderia multivorans. Case Rep Pediatr 2020;2020:1536714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lokken EM, Walker CL, Delaney S, Kachikis A, Kretzer NM, Erickson A, et al. Clinical characteristics of 46 pregnant women with a SARS-CoV-2 infection in Washington state. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2020. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Breslin N, Baptiste C, Gyamfi-Bannerman C, Miller R, Martinez R, Bernstein K, et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 infection among asymptomatic and symptomatic pregnant women: two weeks of confirmed presentations to an affiliated pair of New York City hospitals. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM 2020;2:100118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gianni S, Safaee Fakhr B, Morais CCA, Di Fenza R, Larson G, Pinciroli R, et al. Nitric oxide gas inhalation to prevent COVID-2019 in healthcare providers. Available at: https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.04.05.20054544v1. Retrieved August 20, 2020.

- 7.National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Nitrogen dioxide: immediately dangerous to life or health concentrations (IDLH. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/idlh/10102440.html. Retrieved June 1, 2020.

- 8.Rice TW, Wheeler AP, Bernard GR, Hayden DL, Schoenfeld DA, Ware LB. Comparison of the SpO2/FIO2 ratio and the PaO 2/FIO2 ratio in patients with acute lung injury or ARDS. Chest 2007;132:410–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miller C, Miller M, McMullin B, Regav G, Serghides L, Kain K, et al. A phase I clinical study of inhaled nitric oxide in healthy adults. J Cyst Fibros 2012;11:324–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barrington KJ, Finer N, Pennaforte T, Altit G. Nitric oxide for respiratory failure in infants born at or near term. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2017, Issue 1. Art. No.: CD000399. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000399.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Gebistorf F, Karam O, Wetterslev J, Afshari A. Inhaled nitric oxide for acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) in children and adults. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2016, Issue 6. Art. No.: CD002787. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD002787.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Robinson JN, Banerjee R, Landzberg MJ, Thiet MP. Inhaled nitric oxide therapy in pregnancy complicated by pulmonary hypertension. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1999;180:1045–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bonnin M, Mercier FJ, Sitbon O, Roger-Christoph S, Jaïs X, Humber M, et al. Severe pulmonary hypertension during pregnancy: mode of delivery and anesthetic management of 15 consecutive cases. Anesthesiology 2005;102:1133–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saura M, Zaragoza C, McMillan A, Quick RA, Hohenadl C, Lowenstein JM, et al. An antiviral mechanism of nitric oxide: inhibition of a viral protease. Immunity 1999;10:21–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhou P, Yang XL, Wang XG, Hu B, Zhang L, Zhang W, et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature 2020;579:270–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ignarro LJ, editor. Nitric oxide: biology and pathobiology. New York: Academic Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alvarez RA, Berra L, Gladwin MT. Home nitric oxide therapy for COVID-19. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2020;202:16–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]