Supplemental Digital Content is available in the text.

Keywords: critical care, postintensive care syndrome, prediction

Abstract

Objectives:

Improved ability to predict impairments after critical illness could guide clinical decision-making, inform trial enrollment, and facilitate comprehensive patient recovery. A systematic review of the literature was conducted to investigate whether physical, cognitive, and mental health impairments could be predicted in adult survivors of critical illness.

Data Sources:

A systematic search of PubMed and the Cochrane Library (Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews ID: CRD42018117255) was undertaken on December 8, 2018, and the final searches updated on January 20, 2019.

Study Selection:

Four independent reviewers assessed titles and abstracts against study eligibility criteria. Studies were eligible if a prediction model was developed, validated, or updated for impairments after critical illness in adult patients. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus or an independent adjudicator.

Data Extraction:

Data on study characteristics, timing of outcome measurement, candidate predictors, and analytic strategies used were extracted. Risk of bias was assessed using the Prediction model Risk Of Bias Assessment Tool.

Data Synthesis:

Of 8,549 screened studies, three studies met inclusion. All three studies focused on the development of a prediction model to predict (1) a mental health composite outcome at 3 months post discharge, (2) return-to-pre-ICU functioning and residence at 6 months post discharge, and (3) physical function 2 months post discharge. Only one model had been externally validated. All studies had a high risk of bias, primarily due to the sample size, and statistical methods used to develop and select the predictors for the prediction published model.

Conclusions:

We only found three studies that developed a prediction model of any post-ICU impairment. There are several opportunities for improvement for future prediction model development, including the use of standardized outcomes and time horizons, and improved study design and statistical methodology.

Survivors of critical illness frequently experience new or worsening physical, cognitive, and/or mental health impairments lasting beyond hospital discharge, recognized as the postintensive care syndrome (PICS) (1). There are currently no proven strategies to reduce the prevalence and severity of multiple impairments within PICS (2), yet the population of survivors is growing (3). A recent large, observational study reported that 64% and 56% of their cohort experienced one or more impairments in the domains of PICS, at 3 and 12 months, respectively (4). Such impairments prevent individuals from returning to their previous familial roles and impact return to employment (5, 6). Ensuing morbidity has broad public health and societal implications (7).

There is a growing urgency to recognize and detect these post-ICU impairments. Survivors of critical illnesses encounter fragmented care as they transition from the ICU to posthospital settings and care in the community in the months after hospital discharge (8–10). Due to the complex and multifaceted care needs of ICU survivors, multiple clinicians are involved in their care, with variable knowledge and abilities to recognize, detect, and manage PICS-associated sequelae (11). Therefore, accurate prediction of future problems following discharge from the ICU or hospital is needed to triage patient care and helps ensure survivors receive the right care, by the right clinician, at the right time in their recovery trajectory. It is particularly important to identify those most at-risk of developing long-term and/or severe impairments to inform clinical decision-making and care coordination. However, the ability to predict impairments in the physical, cognitive, and/or mental health domains of PICS is currently unknown.

In May 2019, the Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) convened a 1-day, state-of-the-art meeting with international and interprofessional experts, to evaluate the literature and reach consensus on key questions relating to PICS (see related article—Mikkelsen et al, in press). We report the results of one aim of this meeting to conduct a systematic review of statistical models for predicting impairments in physical, cognitive, and/or mental health status in adult ICU survivors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This systematic review was registered on International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (CRD42018117255) and conducted and reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews guidelines (12). For the purpose of this review, we distinguished between publications that could be considered “prediction model” studies, rather than “predictor finding” (also called “prognostic factor”) studies (13). This distinction is based on the goal of a prediction model to use multiple variables, in combination, to estimate patient-specific probabilities of the likelihood of a future health state (14). Comparatively, prognostic factor (predictor finding) studies aim to identify individual predictors’ (such as age, disease stage, or biomarkers) independent contribution to the prediction of a diagnostic or prognostic outcome (14). For purposes of this review, we defined a prediction model publication as a study where a model, score, or formula, comprising the combination of two or more predictors, was reported.

Search Strategy and Sources

PROSPERO was initially searched to identify whether a systematic review on this topic was registered. Thereafter, an experienced medical information specialist (B.S.) iteratively developed and tested a systematic and comprehensive literature search strategy in consultation with the research team. The strategy was peer reviewed by another senior information specialist prior to execution using the Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies (PRESS) Checklist (15). The searches were performed in PubMed and the Cochrane Library (Wiley platform) on December 8, 2018, and updated on January 6, 2019.

For the purposes of this review, we were not focused on predicting PICS but, rather, impairments in its constituent domains (physical, cognitive, and/or mental health). The searches used a combination of controlled vocabulary (e.g., “Intensive Care Units”, “Survivors”, “Mass Screening”) and keywords (e.g., “critical care”, “post-ICU”, “screen”). Vocabulary and syntax were adjusted across databases. There were no language restrictions, but results were limited to the last 10 years to identify contemporary papers, consistent with the introduction of the term PICS in a 2012 publication. Publications that were nonhuman or not original research (e.g., animal studies, editorials) were removed from the PubMed results. Specific details regarding the strategies appear in Supplemental Table 1 (Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/CCM/F853).

We also identified three related systematic reviews and on January 20, 2019, searched PubMed for the references cited in each, as well as for records related to or citing any of these reviews.

Study Selection and Screening

Titles and abstracts were assessed against eligibility criteria (Supplemental Table 2, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/CCM/F853) with each title and abstract undergoing independent review by two of the four reviewers (K.J.H., E.H., N.L., J.M.). Full-text articles were retrieved where the abstract contained insufficient information to assess eligibility. Full-text articles were independently reviewed by two of the four reviewers, against eligibility criteria (Supplemental Table 2, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/CCM/F853). Discrepancies were resolved by consensus between the reviewers, with any remaining conflicts resolved by an independent reviewer (M.O.H.).

Data Extraction (Including Risk of Bias)

A prepiloted, standardized form was used for data extraction by a single reviewer (E.H.) and independently cross-checked by a second reviewer (K.J.H.). Data items included the following: 1) study characteristics; 2) outcome measurement (timing of measurement, tools used); and 3) prediction model descriptors.

Three independent assessors (M.S. G.S.C., M.O.H.) reviewed each article, using the Prediction model Risk Of Bias Assessment Tool (PROBAST) (14) to evaluate risk of bias for the included studies. The PROBAST was designed to assess studies that develop, validate, or update multivariable prediction models for diagnosis or prognosis. The assessment consists of four domains containing 20 signaling questions to facilitate recognition of both the risk of bias and applicability of a study (16). The four domains focus on 1) “Participants”—the data sources used and how participants were selected for enrollment into the study, 2) “Predictors”—definition and measurement of the predictors, 3) “Outcome”—definition and determination of the outcome, and 4) “Analysis”—whether key statistical considerations were correctly addressed. Domain 4 relates to how the studies addressed key statistical considerations related to prediction model development. This domain does not have an applicability section and is only assessed for risk of bias.

For the overall grading for each study, we used the criteria detailed in the PROBAST “Explanation and Elaboration” document (16). Specifically, if the evaluation of a prediction model was judged as low on all domains relating to bias and applicability, the study was rated as “low risk of bias” or “low concern regarding applicability”. If an evaluation resulted in a rating of “high” for at least one domain, it was rated as “high risk of bias” or “high concern regarding applicability” accordingly. If the prediction model evaluation was unclear for one or more domains, but rated as low in the remaining domains, it was rated as “unclear risk of bias” or “unclear concern regarding applicability.”

RESULTS

Study Selection

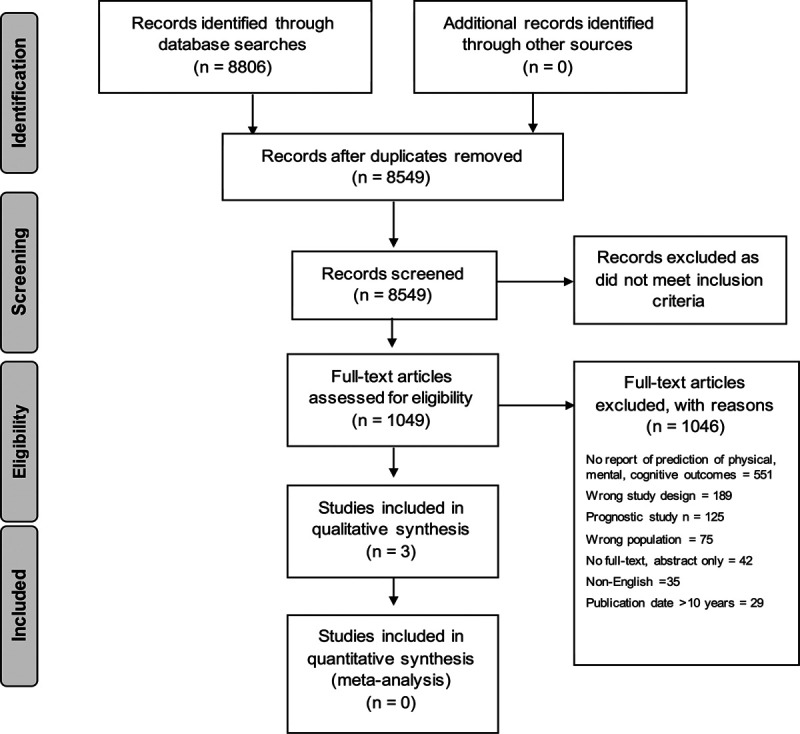

The search retrieved 8,806 citations. After removal of duplicates, 8,549 titles and abstracts were screened for eligibility, with 1,049 meeting eligibility criteria. After screening the full-text articles, three studies were eligible and included (Fig. 1). The top three reasons for exclusion were as follows: No prediction of impairments in physical, cognitive, or mental health (n = 551); study design did not meet our inclusions (n = 189); or classified as a prognostic factor study, as defined above (n = 125).

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews flow diagram—selection of articles.

Description of Included Studies

Characteristics of the three included studies, along with the outcome measurement used, are presented in Tables 1 and 2 and Supplemental Table 3 (Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/CCM/F853). Two of the studies predicted physical function after critical illness, whereas the remaining study predicted mental health. Notably, none of the included studies predicted cognitive function after hospital discharge.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of Included Studies

| References | Location | Design | Cohort, n | Data Source | ICU Type | Age, yr | Male, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Milton et al (17) | Europe | Prospective cohort | 572 enrolled; cases n = 80; noncases n = 319 | Multinational | 10 mixed | Cases 64 (54–72)a; noncases 65 (56–73)a | Cases 59; noncases 62 |

| Detsky et al (18) | United States | Prospective cohort | 303 enrolled; 299 at follow-up | Multicenter | 3 medical; 2 surgical | 62 (53–71)a | 57 |

| Schandl et al (19) | Europe | Prospective quasi-experimental | 258 enrolled; 148 at follow-up | Single center | 1 mixed | Intervention male 53 (17)b; intervention Female 52 (18)b;control male 52 (17)b; control female 54 (20.5)b | Intervention 65; control 64 |

aMedian (interquartile range).

bMean (sd).

TABLE 2.

Description of Outcomes Measures in Included Studies

| References | Postintensive Care Syndrome–Dependent Variable | Outcome Measure/s | Outcome Measure Score Direction | Timing of Outcome Measurement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Milton et al (17) | Mental health—depression, anxiety, posttraumatic stress disorder | HADS; RAND-36 (Mental Component Summary); PTSS-14 | HADS—high score = worse outcome; RAND—36 low score = worse outcome; PTSS-14—high score = worse outcome | 3 mo post ICU discharge |

| Detsky et al (18) | Physical function | Independent ambulation up 10 steps pre hospital. Independent toileting pre hospital | N/A | Prehospital and 6 mo post enrollment |

| Schandl et al (19) | Physical function | Katz ADL Index; ADL Staircase Questionnaire | High score = worse outcome | Katz ADL Index at 2 wk pre hospital; ADL Staircase Questionnaire at 2 mo post ICU discharge |

ADL = activities of daily living, HADS = Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, PTSS = Posttraumatic Stress Scale.

Milton et al (17) in 2018 conducted a prospective, multinational study (n = 572) across 10 general ICUs in secondary and tertiary care hospitals in Sweden, Denmark, and the Netherlands, in a mixed cohort, of middle-aged patients. The prediction model they developed focused on the mental health domain of PICS—specifically anxiety, depression, and posttraumatic stress. The model was developed to predict individual patients’ risk for psychologic problems at 3 three months after ICU discharge. The final predictors in their model included the following: age, lack of social support, traumatic memories, and symptoms of depression assessed at ICU discharge. The intended time point of application for the model was ICU discharge to identify high-risk patients that might require post-ICU follow-up.

Detsky et al (18) in 2017 conducted a prospective, multisite study (n = 303) across three university-affiliated hospitals in Philadelphia, United States, in medical and surgical cohorts of mostly male, middle-aged patients. The prediction model developed focused on the physical domain of PICS and identified important predictors of return to baseline function (6 mo status, compared with pre-ICU admission). In the model, predictors for not returning to baseline function included age, medical (vs surgical) patient, non-White race, higher Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation III score, hospitalization in prior year, and past history of cancer, liver disease, neurologic condition, or any type of transplantation. The model used easily accessible factors that could be obtained on day 1 of the ICU admission.

Schandl et al (19) in 2014 conducted a prospective, quasiexperimental, single site study (n = 258) in Stockholm, Sweden, in a mixed cohort of middle-aged patients. The predictive model focused on physical disability as the PICS domain of interest. In the final model, the four predictors included are low educational level, impaired core stability, fractures, and an ICU length of stay of more than 2 days. The intended timepoint for application of this model was ICU discharge to help clinicians identify patients at risk of ongoing physical disability and who might warrant ongoing support

Risk of Bias and Applicability (PROBAST) Assessment

The overall and domain specific gradings for risk of bias and applicability are reported in Table 3. All studies received a rating of high risk of bias, principally due to issues in the analysis domain 4, related to the statistical models used to develop the prediction model.

TABLE 3.

Results From the Prediction Model Study Risk Of Bias Assessment Tool Assessment

| Domain and Definition | Milton et al (17) | Detsky et al (18) | Schandl et al (19) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | |||

| A) Risk of bias | High | High | High |

| B) Applicability | High | Low | Low |

| Domain 1: Participant selection | |||

| A) Risk of bias introduced by selection of participants | Low | Low | Low |

| B) Concern that the included participants and setting do not match the review question | Low | Low | Low |

| Domain 2: Predictors | |||

| A) Risk of bias introduced by predictors or their assessment | Low | Low | Low |

| B) Concern that the definition, assessment, or timing of assessment of predictors in the model do not match the review question | High. | Low | Low |

| Rationale: selected ICU discharge risk factors may be problematic to capture in practice. | |||

| Domain 3: Outcome | |||

| A) Risk of bias introduced by the outcome or its determination | Low | High. | High; |

| Rationale: concerns around the use of baseline information (that were used as candidate predictors) to define the outcome. High risk of bias due to reliance on self-report from either patients or caregivers, without use of a performance-based measure. | Rationale: The combination of high risk of bias due to reliance on self-report from either patients or caregivers, without use of a performance-based measure and differential verification of the outcome for some individuals. | ||

| B) Concern that the outcome, its definition, timing, or determination do not match the review question | Low | Low | Low |

| Domain 4: Analysis | |||

| A) Risk of bias introduced by sample size or participant flow | High. | High. | High. |

| Rationale: small EPV, univariable p-based screening of variables for inclusion into model, unclear whether all model building steps were repeated in the bootstrap. | Rationale: Small EPV, no adjustment for overfitting, internal validation incompletely described, and unclear whether all model building steps were repeated in the cross-validation. | Rationale: Small EPV, no adjustment for overfitting, internal validation incompletely described, continuous variables were dichotomized. |

EPV = events per variable.

Possible rankings for responses related to risk of bias (indicated as “A”) are low, high, or unclear. Justification is not always necessary when a ranking of low is reported but is necessary when a ranking of high or unclear is provided. Possible rankings for responses related to applicability (indicated as “A”) are the same, although only applies to domains 1, 2, and 3 and not domain 4. The Prediction Model Study Risk Of Bias Assessment Tool (PROBAST) consists of four domains containing 20 signaling questions to facilitate both the risk of bias and applicability assessment, which are detailed in the PROBAST “Explanation and Elaboration” document (16). We have noted why an assessment other than low was determined by the raters.

Domain 1: Participant Selection

All studies selected a diverse critically ill population, and the PROBAST assessment led to the classification of all three studies having a low risk of bias and low concern regarding applicability related to the participants that were selected.

Domain 2: Predictors

All studies had a low risk of bias rating related to the predictors used in the prediction model development. We chose the rating of “high” concern for applicability for the study by Milton et al (17) as there was concern about the ability to capture the modified patient health questionnaire (PHQ)–2 as a predictor at the time of ICU discharge. Indeed, in the supplement they report that the PHQ-2 total score was missing in 11% of responders.

Domain 3: Outcome

All studies had a low concern or risk regarding their methodology in addition to the applicability of the prediction model outcome for use in clinical practice and/or other studies. However, only the study by Milton et al (17) received a low ranking for risk of bias. One concern about the outcome used by Schandl et al (19) and Detsky et al (18) was the reliance on self-reported measures of physical function (e.g. activities of daily living [ADL]), via the patient or caregiver, without inclusion of performance-based measures performed under standardized conditions (20–22). Additionally, the latter study only evaluated a high-level mobility activity (the ability to ambulate up 10 stairs independently) and one basic ADL (toilet independently). These functional activities require different physical skills; furthermore, a range of disability within these two extremes may not be captured.

Domain 4: Analysis

All studies received a rating of high concern for risk in the analysis domain. The key concern in all studies related to the sample size and the ratio of the number of outcome events to the total number of candidate predictors, termed “events per variable” (EPV). There is ongoing discussion about when this ratio becomes a concern, as discussed in section 4.1 of PROBAST “Explanation and Elaboration” document (16). Studies with EPVs lower than 10 may be considered at high risk of creating an “overfitted” model or failing to include important predictors (16). All studies had a EPV ratio that resulted in a concern for potential bias: Milton et al (17) EPV equals to 4.4 (80 participants with psychologic problems/18 candidate predictors), Detsky et al (18) EPV equals to 4.1 (91 participants returned to baseline/22 candidate predictors), and Schandl et al (19) EPV equals to 3.0 (69 participants had new-onset physical disability/23 candidate predictors). Each study had additional signaling questions that supported the ranking of high risk of bias (supplemental materials, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/CCM/F853).

DISCUSSION

Prediction of ICU survivors’ outcomes is important to patients, families, clinicians, and for healthcare delivery. However, based on our systematic review, the availability of rigorous prediction models is limited, and more work is required to advance this field. Specifically, our systematic review identified only three studies that developed a model to predict long-term impairments. Of the three, one predicted mental health, two predicted physical function, and none predicted cognitive function after critical illness. Further, the development of the prediction model in each study was deemed to be at a high risk of bias, and to our knowledge, these models have not been externally validated at the time of this review (although from personal communication with the authors, an external validation has been completed for Schandl et al [19], and is under peer review). We also identified issues related to the definition and measurement of outcomes and the reliance on self-reported measures recognizing that performance-based measures are also important to capture health states in critical care research, although both can be prone to measurement error.

Several aspects of clinical care could benefit from future advancements in the prediction of postdischarge impairments. At discharge from the ICU, patients and families might be better informed about potential impairments across the arc of care. A current challenge is that patients and families are often underprepared for what to expect post-ICU discharge, with a recent survey reporting that approximately one third of ICU physicians rarely formally discuss post-ICU challenges with patients and families (23). The reasons for this finding are likely multifactorial; however, a lack of evidence regarding the prediction of PICS outcomes may be a contributing factor.

PICS-related problems are commonly considered within post-ICU programs such as peer support groups (24, 25) and follow-up clinics (26–28). However, one of the common barriers to implementing these programs is identifying which patients are likely to benefit from attending (29). Given issues with the cost and sustainability of such programs, it is crucial to identify the most suitable target population. Once these patients have returned to their communities, they are likely to be managed by their primary care doctor who may have variable exposure to and knowledge of PICS-related problems. Yet, little is known about how to best transition survivors back to primary care (30). Further, patterns of recovery can be variable among survivors where some might experience an initial improvement in their health, followed by a later decline (31).

This review, designed as part of the SCCM’s International Consensus Conference on Prediction and Identification of Long-Term Impairments after Critical Illness (32), has important clinical implications for bedside clinicians. First, patients and families care greatly about post-ICU impairments such as physical function and often want to know an estimate of long-term functional outcomes following critical illness (31, 33). This review highlighted the limited evidence-base with which to predict such outcomes. When providing anticipatory guidance to patients and their family in the ICU, and thereafter, clinicians should acknowledge the uncertainty with which post-ICU impairments can be predicted currently. Although there is no one strategy to reliably predict PICS-related problems, clinicians can use the approach recommended by the consensus conference to risk-stratify and screen survivors at high risk for long-term cognitive, mental health, and physical impairments after critical illness. Therein, factors before (e.g., pre-exiting functional impairments), during (e.g., delirium), and after (e.g., early psychologic symptoms) can be used to identify patients at high risk for long-term functional impairments.

Second, there is growing interest in the critical care community to improve ICU survivorship and address post-ICU impairments. Despite the lack of supporting evidence (24, 26), one key intervention has been the establishment of post-ICU recovery programs globally (27, 28, 34). This review, along with the international consensus conference recommendations (32), can be used to inform the identification of patients who are more likely to encounter new problems or worsening of pre-existing problems following ICU discharge who may benefit from structured recovery programs. It can also aid the identification of survivors in need of referral to specialist clinicians and services (e.g., rehabilitation). Third, there is a need to develop rigorous prediction models to better predict post-ICU impairments that can be used to more robustly inform clinical decision-making as described above. This review summarizes the current state of the literature and provides impetus to advance the science, clearly setting out the methodological groundwork to do so.

To help centralize guidance in this nascent research area, we have developed a summary table (Table 4) to provide researchers a centralized resource to guide the development of future prediction model studies using current best practices. These recommendations borrow heavily from the Transparent Reporting of a multivariable prediction model for Individual Prognosis Or Diagnosis statement (35, 36) and PROBAST statement (14, 16). We have also embedded several references in Table 4 to provide methodological details that could help inform researchers developing prediction study funding applications. We specifically direct researchers to recently published prediction model sample size guidance based on the type of outcome being predicted—continuous (16, 37), binary (38, 39), or time-to-event (38). The concern regarding low EPV in domain 4 of the PROBAST assessment stems largely from too small sample sizes, which may have resulted from a lack of clear sample size guidance at the time of their design.

TABLE 4.

Recommended Approaches and Considerations for Researchers When Planning and Reporting the Development of a New Prediction Model

| Domains | Key Design and Reporting Considerations |

|---|---|

| Data source | • Clarify how the data used to develop the prediction model were collected. |

| Participants | • Clearly report the inclusion and exclusion criteria for individuals included in the study. |

| • Provide descriptive summaries of participant characteristics used for internal (and if relevant, external) validation. | |

| • The targeted sample size should be determined by considering the number of subjects relative to the number of predictor parameters for potential inclusion in the prediction model (i.e., events per variable). For sample size guidance, we direct readers to methodological papers based on the type of outcome being predicted—continuous (16, 37), binary (38, 39), or time-to-event (38). | |

| Outcome | • Specific details should be provided regarding how the outcome was defined, including what information was used to create the outcome variable, at what precise time the outcome was collected or measured during follow-up, and what differences, if any, in how this information was captured for individuals in the study. |

| Predictors | • Provide a precise definition of the predictor variables included in the final model, along with the method(s) by which these variables were selected. |

| Missing data | • Report how much data were missing from the predictors and from the outcome. |

| • A plan for management of missing data should be developed prior to model development. | |

| Model development | • Univariable selection using p thresholds should be avoided and in general, data-driven variable selection should be done with some conservatism (e.g., accepting higher p thresholds for variable inclusion). |

| • Avoid dichotomizing and categorizing continuous predictors and consider other methods (e.g., restricted cubic splines or fractional polynomial methods) to model nonlinear relationships. | |

| Model performance | • Performance measures (40) should be tailored to the intended purpose of the model but generally be visualized when possible and include a measure of discrimination (e.g., area under receiver operator characteristics curve or area under precision recall curve), calibration slope and intercept (e.g., calibration curve [41, 42]), and clinically relevant performance (e.g. decision curve [43]). Avoid performance measures based on arbitrary chosen thresholds (44). |

| • CIs should be reported for performance measures. | |

| Model specification | • Report the model that was used to develop the statistical model (e.g., logistic regression, Cox proportional hazards model). |

| • The full model equation should be reported when applicable (e.g., intercept or the baseline hazard function in a time-to-event model). | |

| Model Validation | • Variable selection should be repeated using bootstrap methods. |

| • Internal validation is an essential component of model development. When possible, conduct external validation. Random splitting for internal validation is not generally a recommended practice (45). Model performance should be assessed by time, geography, center/site, and other key factors (46). | |

| • Optimism correction should be conducted and reported. | |

| Additional Considerations | • In prediction studies focusing in individuals who survive a critical care admission, many will die within the selected time horizons (e.g., 3–12 mo following discharge). This creates a problem whereby a patient is at risk for multiple events, but only one of these events is of interest (i.e., competing risks). If mortality is not part of the predicted outcome state, more complex methods may need to be considered when developing a prediction model (16). |

| • Authors should consider issues related to measurement error (47, 48), fairness (49–54), and how a model would be assessed in a risk of bias assessment (i.e., Prediction Model Study Risk Of Bias Assessment Tool [16]) when constructing their model. |

For additional details, authors are directed to the embedded citations and to the Transparent Reporting of a multivariable prediction model for Individual Prognosis Or Diagnosis publication (35) that contains an accompanying checklist that informed this table. In addition to optimally support prediction model replication and extension, we recommend that authors make their programming code (particularly in the case of machine learning models) available in full. In addition, whenever possible, the data used should be made publicly available to the research community.

There are potential limitations to our study. First, it is possible that our inclusion criteria or search did not identify some prediction model articles that have been published. However, omissions are unlikely to have been systematic or frequent, as we are aided by the knowledge of literature by content experts in the working group. Second, due to resource constraints, our search only included two literature databases. However, we hand searched the reference list of the three articles included, as well as the three identified and related systematic reviews. Finally, we restricted our focus to the prediction of physical, cognitive, and mental health outcomes in adult ICU survivors. There may be prediction models for other outcomes or for pediatric populations that are not examined here.

In conclusion, our systematic review of prediction models for physical, cognitive, and mental health impairments in adult survivors of critical illness identified only three published studies. At the present time, there is no published external validation of these models. The design and evaluation of methodologically rigorous prediction models is important to assess for potential benefit on clinical decision-making, patient triage, and communication with survivors of critical illness and their families.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Kaitryn Campbell, MLIS, AHIP (St. Joseph’s Healthcare Hamilton, Hamilton, ON) for peer review of the PubMed search strategy. We would like to thank Lynn Higgins and Western Health Library Services for their contribution in sourcing full-text articles for this review.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

This work was conducted for the Society of Critical Care Medicine’s International State-of-the-Art Workshop on Prediction and Identification of Long-Term Impairments after Critical Illness.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s website (http://journals.lww.com/ccmjournal).

Supported, in part, by Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM). The information specialist was funded by SCCM to conduct the search for this review.

Drs. Haines’, McPeake’s, Ferrante’s, and Sevin’s institutions received funding from the Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM). Drs. Haines from a Thrive grant from SCCM, and Drs. McPeake and Sevin received funding from SCCM. Dr. McPeake’s institution received funding from THIS Institute (University of Cambridge). Drs. Anderson’s and Ferrante’s institutions received funding from National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI). Dr. Anderson’s institution received funding from the American Thoracic Society Foundation. Drs. Anderson, Brummel, Ferrante, Jackson, Needham, and Harhay received support for article research from the NIH. Dr. Brummel’s institution received funding from the NIH, and he received funding from Merck. Drs. Hough and Skidmore disclosed work for hire. Dr. Ferrante is supported by a Beeson award from the National Institute on Aging (K76 057023). Dr. Needham’s institution received funding from NIH (R01HL132887) evaluating nutrition and exercise in acute respiratory failure. For purposes of this multisite trial, Baxter Healthcare Corporation has provided an unrestricted research grant and donated amino acid product. Also, two study sites (not his University/site) have received an equipment loan from Reck Medical Devices. Dr. Collins was supported by the National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centre, Oxford, and Cancer Research UK (program grant: C49297/A27294). Dr. Harhay’s institution received funding from NIH/NHLBI grants K99HL141678 and R00HL141678. BJA was supported by K23HL140482 from the U.S. National Institutes of Health. The remaining authors have disclosed that they do not have any potential conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Needham DM, Davidson J, Cohen H, et al. : Improving long-term outcomes after discharge from intensive care unit: Report from a Stakeholders’ conference. Crit Care Med. 2012; 40:502–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kross EK, Hough CL: Broken wings and resilience after critical illness. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016; 13:1219–1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iwashyna TJ, Cooke CR, Wunsch H, et al. : Population burden of long-term survivorship after severe sepsis in older Americans. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012; 60:1070–1077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marra A, Pandharipande PP, Girard TD, et al. : Co-occurrence of post-intensive care syndrome problems among 406 survivors of critical illness. Crit Care Med. 2018; 46:1393–1401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kamdar BB, Suri R, Suchyta MR, et al. : Return to work after critical illness: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Thorax. 2020; 75:17–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McPeake J, Mikkelsen ME, Quasim T, et al. : Return to employment after critical illness and its association with psychosocial outcomes. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2019; 16:1304–1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mikkelsen ME, Netzer G, Iwashyna T. Post-Intensive Care Syndrome (PICS) 2019. Available at: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/post-intensive-care-syndrome-pics. Accessed January 9, 2020.

- 8.Brandstetter S, Dodoo-Schittko F, Brandl M, et al. ; DACAPO study group: Ambulatory and stationary healthcare use in survivors of ARDS during the first year after discharge from ICU: Findings from the DACAPO cohort. Ann Intensive Care. 2019; 9:70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hill AD, Fowler RA, Pinto R, et al. : Long-term outcomes and healthcare utilization following critical illness–A population-based study. Crit Care. 2016; 20:76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lone NI, Gillies MA, Haddow C, et al. : Five-year mortality and hospital costs associated with surviving intensive care. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016; 194:198–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jensen EK, Poulsen LM, Mathiesen O, et al. : Healthcare providers’ knowledge and handling of impairments after intensive unit treatment: A questionnaire survey. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2020; 64:532–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. : The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009; 62:e1–e34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Riley RD, Hayden JA, Steyerberg EW, et al. ; PROGRESS Group: Prognosis Research Strategy (PROGRESS) 2: Prognostic factor research. PLoS Med. 2013; 10:e1001380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wolff RF, Moons KGM, Riley RD, et al. ; PROBAST Group†: PROBAST: A tool to assess the risk of bias and applicability of prediction model studies. Ann Intern Med. 2019; 170:51–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McGowan J, Sampson M, Salzwedel DM, et al. : PRESS peer review of electronic search strategies: 2015 guideline statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016; 75:40–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moons KGM, Wolff RF, Riley RD, et al. : PROBAST: A tool to assess risk of bias and applicability of prediction model studies: Explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2019; 170:W1–W33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Milton A, Schandl A, Soliman IW, et al. : Development of an ICU discharge instrument predicting psychological morbidity: A multinational study. Intensive Care Med. 2018; 44:2038–2047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Detsky ME, Harhay MO, Bayard DF, et al. : Six-month morbidity and mortality among intensive care unit patients receiving life-sustaining therapy. A prospective cohort study. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2017; 14:1562–1570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schandl A, Bottai M, Holdar U, et al. : Early prediction of new-onset physical disability after intensive care unit stay: A preliminary instrument. Crit Care. 2014; 18:455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bean JF, Olveczky DD, Kiely DK, et al. : Performance-based versus patient-reported physical function: What are the underlying predictors? Phys Ther. 2011; 91:1804–1811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chan KS, Aronson Friedman L, Dinglas VD, et al. : Are physical measures related to patient-centred outcomes in ARDS survivors? Thorax. 2017; 72:884–892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Denehy L, Nordon-Craft A, Edbrooke L, et al. : Outcome measures report different aspects of patient function three months following critical care. Intensive Care Med. 2014; 40:1862–1869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Govindan S, Iwashyna TJ, Watson SR, et al. : Issues of survivorship are rarely addressed during intensive care unit stays. Baseline results from a statewide quality improvement collaborative. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014; 11:587–591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haines KJ, Beesley SJ, Hopkins RO, et al. : Peer support in critical care: A systematic review. Crit Care Med. 2018; 46:1522–1531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McPeake J, Hirshberg EL, Christie LM, et al. : Models of peer support to remediate post-intensive care syndrome: A report developed by the society of critical care medicine thrive international peer support collaborative. Crit Care Med. 2019; 47:e21–e27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lasiter S, Oles SK, Mundell J, et al. : Critical care follow-up clinics: A scoping review of interventions and outcomes. Clin Nurse Spec. 2016; 30:227–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McPeake J, Shaw M, Iwashyna TJ, et al. : Intensive care syndrome: Promoting independence and return to employment (InS:PIRE). Early evaluation of a complex intervention. PLoS One. 2017; 12:e0188028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sevin CM, Bloom SL, Jackson JC, et al. : Comprehensive care of ICU survivors: Development and implementation of an ICU recovery center. J Crit Care. 2018; 46:141–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haines KJ, McPeake J, Hibbert E, et al. : Enablers and barriers to implementing ICU follow-up clinics and peer support groups following critical illness: The Thrive Collaboratives. Crit Care Med. 2019; 47:1194–1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Admon AJ, Tipirneni R, Prescott HC: A framework for improving post-critical illness recovery through primary care. Lancet Respir Med. 2019; 7:562–564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pfoh ER, Wozniak AW, Colantuoni E, et al. : Physical declines occurring after hospital discharge in ARDS survivors: A 5-year longitudinal study. Intensive Care Med. 2016; 42:1557–1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mikkelsen MES, Anderson B, Bienvenu JO, et al. : Society of Critical Care Medicine’s international consensus conference on prediction and identification of long-term impairments after critical illness. Crit Care Med. 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Azoulay E, Kentish-Barnes N, Pochard F: Health-related quality of life: An outcome variable in critical care survivors. Chest. 2008; 133:339–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Haines KJ, Holdsworth C, Cranwell K, et al. : Development of a peer support model using experience-based co-design to improve critical care recovery. Crit Care Explor. 2019; 1:e0006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Collins GS, Reitsma JB, Altman DG, et al. : Transparent reporting of a multivariable prediction model for individual prognosis or diagnosis (TRIPOD). Ann Intern Med. 2015; 162:735–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moons KG, Altman DG, Reitsma JB, et al. : Transparent reporting of a multivariable prediction model for individual prognosis or diagnosis (TRIPOD): Explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2015; 162:W1–W73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Riley RD, Snell KIE, Ensor J, et al. : Minimum sample size for developing a multivariable prediction model: Part I - Continuous outcomes. Stat Med. 2019; 38:1262–1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Riley RD, Snell KI, Ensor J, et al. : Minimum sample size for developing a multivariable prediction model: PART II - Binary and time-to-event outcomes. Stat Med. 2019; 38:1276–1296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van Smeden M, Moons KG, de Groot JA, et al. : Sample size for binary logistic prediction models: Beyond events per variable criteria. Stat Methods Med Res. 2019; 28:2455–2474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Steyerberg EW, Vickers AJ, Cook NR, et al. : Assessing the performance of prediction models: A framework for traditional and novel measures. Epidemiology. 2010; 21:128–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Austin PC, Steyerberg EW: Graphical assessment of internal and external calibration of logistic regression models by using loess smoothers. Stat Med. 2014; 33:517–535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Van Calster B, Nieboer D, Vergouwe Y, et al. : A calibration hierarchy for risk models was defined: From utopia to empirical data. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016; 74:167–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Van Calster B, Wynants L, Verbeek JFM, et al. : Reporting and interpreting decision curve analysis: A guide for investigators. Eur Urol. 2018; 74:796–804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wynants L, van Smeden M, McLernon DJ, et al. ; Topic Group ‘Evaluating diagnostic tests and prediction models’ of the STRATOS initiative: Three myths about risk thresholds for prediction models. BMC Med. 2019; 17:192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Steyerberg EW. Clinical Prediction Models. 2019New York, Springer [Google Scholar]

- 46.Riley RD, Ensor J, Snell KI, et al. : External validation of clinical prediction models using big datasets from e-health records or IPD meta-analysis: Opportunities and challenges. BMJ. 2016; 353:i3140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Luijken K, Groenwold RHH, Van Calster B, et al. : Impact of predictor measurement heterogeneity across settings on the performance of prediction models: A measurement error perspective. Stat Med. 2019; 38:3444–3459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pajouheshnia R, van Smeden M, Peelen LM, et al. : How variation in predictor measurement affects the discriminative ability and transportability of a prediction model. J Clin Epidemiol. 2019; 105:136–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Braun L: Race, ethnicity and lung function: A brief history. Can J Respir Ther. 2015; 51:99–101. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Eneanya ND, Yang W, Reese PP: Reconsidering the consequences of using race to estimate kidney function. JAMA. 2019; 322:113–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gianfrancesco MA, Tamang S, Yazdany J, et al. : Potential biases in machine learning algorithms using electronic health record data. JAMA Intern Med. 2018; 178:1544–1547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Goodman SN, Goel S, Cullen MR: Machine learning, health disparities, and causal reasoning. Ann Intern Med. 2018; 169:883–884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rajkomar A, Hardt M, Howell MD, et al. : Ensuring fairness in machine learning to advance health equity. Ann Intern Med. 2018; 169:866–872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Obermeyer Z, Powers B, Vogeli C, et al. : Dissecting racial bias in an algorithm used to manage the health of populations. Science. 2019; 366:447–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.