Abstract

Electrodepositing low loadings of metallic nanoparticle catalysts onto the surface of semiconducting photoelectrodes is a highly attractive approach for decreasing catalyst costs and minimizing optical losses. However, securely anchoring nanoparticles to the photoelectrode surface can be challenging—especially if the surface is covered by a thin insulating overlayer. Herein, we report on Si-based photocathodes for the hydrogen evolution reaction that overcome this problem through the use of a 2–10 nm thick layer of silicon oxide (SiOx) that is deposited on top of Pt nanoparticle catalysts that were first electrodeposited on a 1.5 nm SiO2|p-Si(100) absorber layer. Such insulator–metal–insulator–semiconductor (IMIS) photoelectrodes exhibit superior durability and charge transfer properties compared to metal–insulator–semiconductor (MIS) control samples that lacked the secondary SiOx overlayer. Systematic investigation of the influence of particle loading, SiOx layer thickness, and illumination intensity suggests that the SiOx layer possesses moderate conductivity, thereby reducing charge transfer resistance associated with high local tunneling current densities between the p-Si and Pt nanoparticles. Importantly, the IMIS architecture is proven to be a highly effective approach for stabilizing electrocatalytic nanoparticles deposited on insulating overlayers without adversely affecting mass transport of reactant and product species associated with the hydrogen evolution reaction.

Keywords: Photoelectrochemistry, photocatalysis, electrocatalysis, UV-ozone, silicon, platinum, nanoparticles, silicon dioxide

Graphical Abstract

As the cost of solar photovoltaic technology continues to drop, a major hurdle limiting the widespread use of variable solar energy is the lack of efficient and cost-effective energy storage.1–3 Photoelectrochemical cells (PECs) provide one promising approach for storing solar energy by converting it into chemical energy, much as nature accomplishes with photosynthesis.4–7 Central to the operation of PEC technologies are semiconducting photoelectrodes that convert sunlight into an electronic driving force, or photovoltage, which is then used to drive nonspontaneous electrochemical reactions such as water electrolysis. By this means, PEC technology is capable of converting abundant and renewable sunlight into storable “solar fuels” such as hydrogen (H2).

Despite the great promise of PEC technology to contribute to a sustainable energy future, there remain several key barriers in the development of commercially viable PEC materials and devices that must be overcome.8–10 One major challenge for PEC water-splitting technology has been the trade-off between photoelectrode stability and efficiency.5,6,11 Consequently, many recent efforts in the field have focused on stabilizing efficient narrow band gap materials like silicon (Si) by coating them with thin, transparent overlayers of insulating materials such as SiO212–17 or TiO2.18–20 These efforts have included the protection of buried p–n junctions,21–24 as well as photoelectrodes based on a metal–insulator–semiconductor (MIS) architecture in which photovoltage is generated across an MIS Schottky junction.11,14,18,25 In MIS photoelectrodes the metallic component is of great importance for generating high photovoltage across the MIS junction as well as for enabling efficient electrocatalysis at the electrode/electrolyte interface.26–29 Additionally, it is critically important that the metal itself also be stable.30,31 This requirement entails not only resistance to oxidation and dissolution, but also strong physical adhesion and robust electronic contact to the underlying photoelectrode. The latter two issues are especially important when the metal layer takes the form of metallic nanoparticles, which naturally have a small contact area with the underlying electrode surface. Despite this challenge, nanoparticle catalysts are attractive for minimizing the loading and cost of expensive catalysts,32 minimizing optical losses,33 and taking advantage of pinch-off effects to achieve higher photovoltages.34–37

One potentially scalable and low-cost means of depositing metal nanoparticles or ultrathin films on photoelectrodes is electrodeposition.38–41 However, it has been observed that the adhesion of metal nanoparticles to the surface of thin insulating materials like SiO2 is very poor,17,42 creating a large challenge for the use of electrodeposition for PEC applications. In this paper, we present a means of stabilizing electrodeposited Pt nanoparticles on a SiO2/p-Si surface while simultaneously reducing charge transfer resistance across the nanoscale Pt|SiO2|Si MIS junction. These improvements were achieved by coating the nanoparticle-containing photoelectrode surface with a thin (2–10 nm) silicon oxide (SiOx) overlayer, which was applied by a simple, room-temperature UV-ozone process.43 Adding this secondary SiOx layer creates what is referred to herein as an insulator–metal–insulator–semiconductor (IMIS) photoelectrode, which is illustrated schematically in Figure 1a. The SiOx-coated Pt nanoparticle structure is similar in nature to core–shell nanoparticles that have previously been used for high temperature heterogeneous catalysis to enhance thermal stability,44–46 improving the stability of Pt for oxygen reduction catalysis,47 and for suppressing undesired back reactions in photoelectrochemical applications.48,49 However, the IMIS photoelectrode takes this core–shell concept a step further, anchoring the catalytic core directly to the surface of the photoelectrode in an architecture that protects both the nanoparticle and the semiconductor.

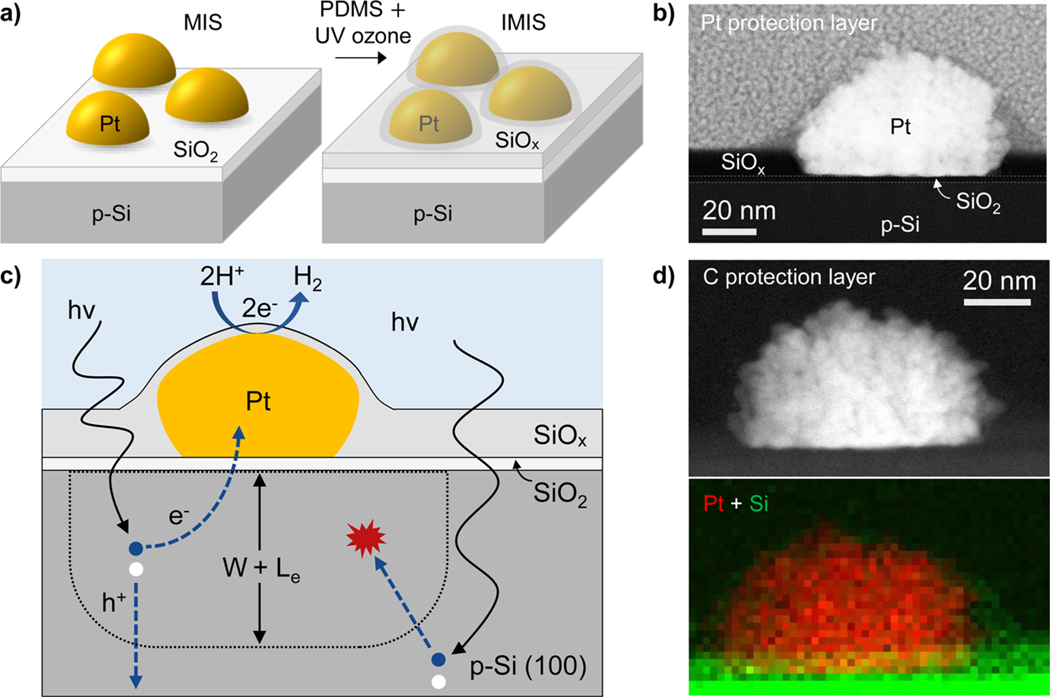

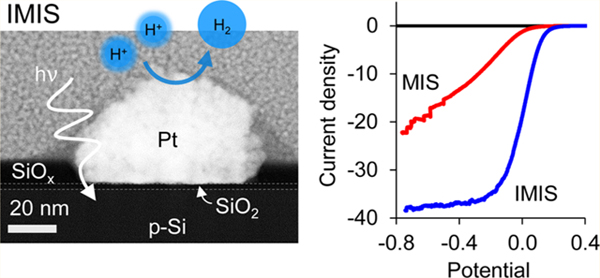

Figure 1.

Nanoparticle-based MIS and IMIS photoelectrodes. (a) Schematic side views of a metal–insulator–semiconductor (MIS) photoelectrode decorated with electrodeposited Pt nanoparticles and an insulator–metal–insulator–semiconductor (IMIS) photoelectrode containing an additional SiOx overlayer. (b) Cross-sectional HAADF-STEM image of a SiOx/Pt/native SiO2/p-Si IMIS nanojunction based on a 10 nm thick SiOx overlayer with Pt protection layer. (c) Schematic side-view illustrating the basic operating processes occurring in an IMIS photoelectrode. (d) Cross-sectional HAADF-STEM image of an IMIS nanojunction described in (b) with a C protection layer (top) and XEDS map of Pt (red) and Si (green) peak signals (bottom).

The basic operating principles of the IMIS photoelectrode are shown schematically in Figure 1c. First, excitons must be generated within a distance less than the sum of the depletion width (W) and effective minority carrier diffusion length (Le) in order for the minority carrier electrons to reach the MIS nanojunction at the base of the metal nanoparticle. Once the minority carrier electron reaches the SiO2/Si interface, it tunnels through the thin SiO2 layer to reach the nanoparticle catalyst, a process that depends strongly on the SiO2 layer thickness.50 Protons in solution are concurrently transported to the nanoparticle surface where they are reduced by the electrons, resulting in the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER).

This initial study of IMIS photoelectrodes was based upon photocathodes made from p-Si(100) wafers. First, the MIS structure (Figure 1a) was fabricated by photoelectrodepositing platinum nanoparticles onto native SiO2/p-Si(100) from a 3 mmol L−1 K2PtCl4 solution. The platinum loading was controlled by varying the number of cyclic voltammetry (CV) cycles during electrodeposition (Figure S1). The resulting average particle size, coverage, spacing, and Pt loadings were determined from SEM analysis (Figure S2) and are provided in Table S1. The average particle size and spacing were observed to increase and decrease, respectively, with increased Pt loading. SEM images in Figure S3 reveal that the as-deposited Pt nanoparticles have a relatively rough and dendritic morphology. Following electrodeposition of the Pt nanoparticles, polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) was spin-coated onto the MIS and converted into SiOx by a room-temperature ultraviolet (UV)-ozone treatment to give the final IMIS structure (Figure 1a). X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) characterization of the as-deposited SiOx layer indicates that Si predominantly exists as silicon dioxide (SiO2) and residual carbon from PDMS remains in the SiO2, consistent with previous studies of thin SiOx films grown by this method (Figure S4).43,51 These previous studies reported that, more than 55% of the C atoms are eliminated from PDMS films after 2 h of UV ozone exposure for SiOx films under 20 nm. Additional details on the UV-ozone treatment and characterization of SiOx thin films can be found in literature.43,51–53 Cross sectional HAADF-STEM and energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (XEDS) mapping images of an IMIS sample, 10 nm SiOx/Pt/native SiO2/p-Si, (Figure 1b,d) shows a well-defined ≈1.5 nm thick native SiO2 layer under the Pt particle and a ≈10 nm thick SiOx layer covering the electrode surface in between the Pt nanoparticles. From other HAADF-STEM images, the observed SiO2 + SiOx thickness varies across the sample (Figure S5). In areas of high Pt particle density the SiOx layer is thicker (up to 17 nm) and thinner (≈9 nm) in areas where particles are relatively far apart. The cross sectional HAADF-STEM and XEDS mapping images in Figure 1b,d and S6 also clearly show a thin SiOx overlayer covering the surface of the Pt nanoparticle. Additional STEM images (Figure S5) suggest that some of the larger particles do not have a complete SiOx shell, allowing some dendritic Pt nanoparticles to protrude out the SiOx shell and directly contact the electrolyte. The observation of partial or full coverage of Pt nanoparticles by the thin SiOx layer is further corroborated by a significant decrease in the Pt 4f XPS signal from the surface of an IMIS sample compared to an MIS sample of identical Pt loading, presumably due to screening by the SiOx overlayer (Table S2).

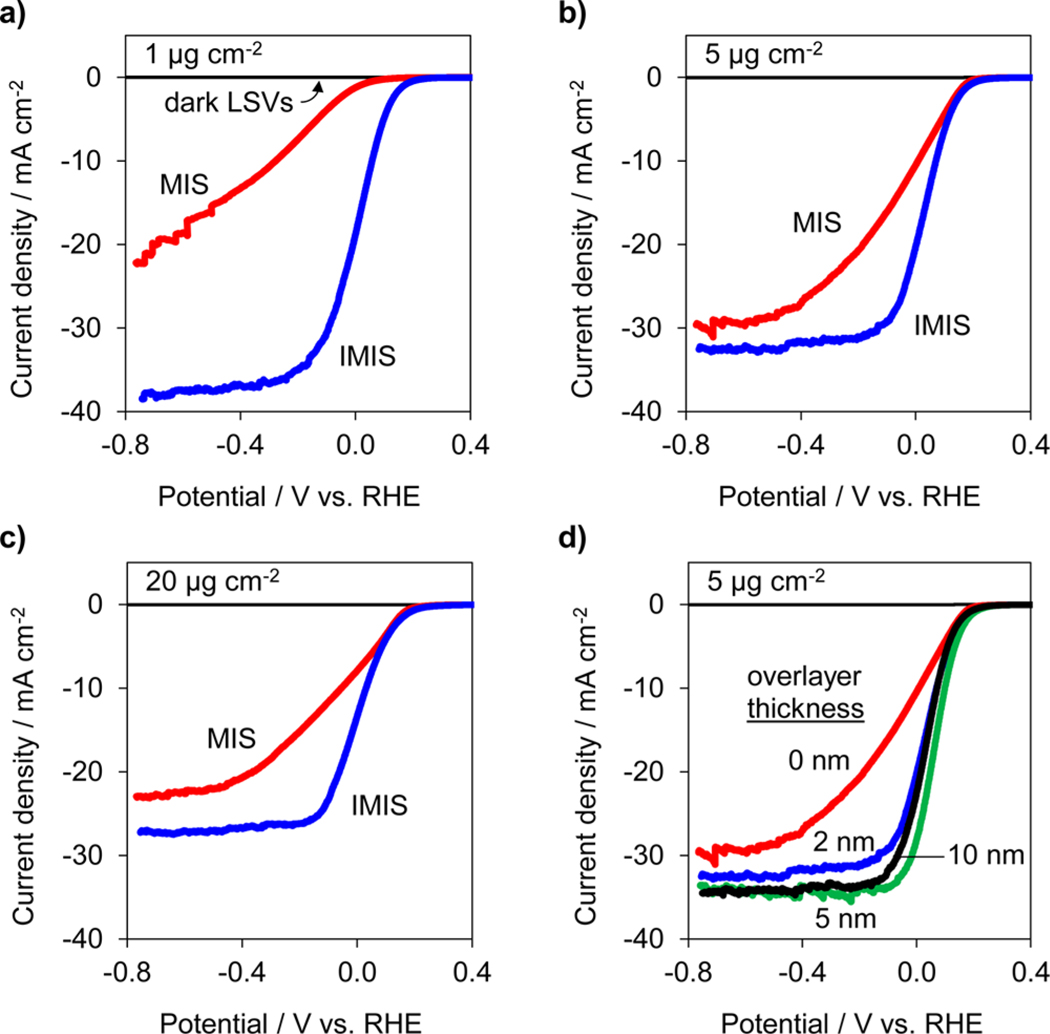

PEC performance of the MIS and IMIS photoelectrodes was evaluated by performing consecutive linear sweep voltammograms (LSVs) in deaerated 0.5 mol L−1 H2SO4 under simulated AM 1.5 G illumination. Figure 2 contains the initial LSV curves for MIS and IMIS photoelectrodes with 1 μg cm−2, 5 μg cm−2, and 20 μg cm−2 Pt loadings (Figure 2a–c). The SiOx overlayer on the IMIS samples was 2 nm thick, as measured by ellipsometry on control areas lacking any Pt nanoparticles. From Figure 2, it is immediately evident that there is a substantial improvement in the current–potential (I–E) characteristics of the IMIS samples compared to the MIS samples, with the former exhibiting larger limiting photocurrents and substantially steeper slopes in the LSV curve as it transitions from the photocurrent onset potential to the photolimiting current plateau. The PEC LSV performance of an UV-ozone treated MIS and “x” nm SiOx/SiO2/p-Si control electrodes was also evaluated, confirming that the difference in PEC performance between the MIS and IMIS photoelectrodes was due to the presence of the SiOx overlayer and not a result of the UV-ozone treatment nor HER catalysis associated with residual carbonaceous species in the SiOx (Figure S7). Table 1 summarizes the performance of all photoelectrodes, as measured by the operating potential required to achieve −10 mA cm−2 for the first LSV measured. The MIS photoelectrode with the lowest Pt loading exhibited the worst performance, requiring −280 mV vs RHE to achieve −10 mA cm−2. By contrast, the IMIS photoelectrode with equivalent Pt loading was able to operate at +60 mV vs RHE at the same current density. Significant improvements in the operating potential of IMIS samples with 5 μg cm−2 and 20 μg cm−2 Pt loading were observed compared to their MIS counterparts, though not as dramatic as for the low Pt loading samples. The presence of the SiOx overlayer created the additional benefit of increasing the photolimited current density. For IMIS samples, the limiting current density decreased monotonically with increasing Pt loading and can be explained by increased optical losses associated with the opaque Pt particles. The ability of the 1 μg cm−2 IMIS sample to achieve a photolimiting current density close to the theoretical maximum for crystalline Si (≈42 mA cm–2 under AM 1.5 illumination) indicates that neither the Pt nanoparticles nor the SiOx overlayer contribute to any significant optical losses for that sample.

Figure 2.

MIS and IMIS performance. LSV measurements for |Pt| native SiO2|p-Si(100) MIS (red) and |2 nm SiOx|Pt|native SiO2|p-Si(100) IMIS (blue) photoelectrodes for (a) 1 μg cm−2 Pt, (b) 5 μg cm−2 Pt, and (c) 20 μg cm−2 Pt. (d) LSV measurements for |”x” nm SiOx|5 μg cm−2 Pt|native SiO2|p-Si(100) for various SiOx thicknesses from 0 to 10 nm. All LSV measurements were performed at 20 mV s−1 in 0.5 mol L−1 H2SO4 under AM 1.5 G illumination. Current densities are normalized with respect to the geometric area of the exposed photoelectrode.

Table 1.

Summary of Pt Particle Characterization (Based on SEM images), Electrode Performance (Based on Figure 2), and Degradation Behavior (Based on Figure 3 and S6–8)a

| approximate Pt loadinga (μg cm−2) | SiOx thickness (nm) | average Pt nanoparticle diameter (nm) | Pt 2D coverage (%) | V vs RHE (mV) at −10 mA cm−2 | ΔV (mV) between LSV 1 and 3 at −10 mA cm−2 | ΔV/h (mV/h) during CP | ΔV (mV) between LSV before and after 1 h CP at −10 mA cm−2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIS | 1 | 0 | 38 ± 32 | 3.3 ± 0.8 | −280 | −200 | −140 | n/ab |

| MIS | 5 | 0 | 55 ± 36 | 15 ± 3.1 | +7 | −70 | −80 | −260 |

| MIS | 20 | 0 | 66 ± 54 | 42 ± 1.2 | −60 | −30 | −45 | −110 |

| IMIS | 1 | 2 | 37 ± 30 | 3.9 ± 0.6 | +60 | −30 | −11 | −80 |

| IMIS | 5 | 2 | 58 ± 34 | 13 ± 0.9 | +70 | −40 | −14 | −30 |

| IMIS | 20 | 2 | 70 ± 53 | 32 ± 1.6 | +30 | −10 | −6 | −15 |

| IMIS | 5 | 5 | 65 ± 42 | 13 ± 0.2 | +100 | −20 | −7 | −12 |

| IMIS | 5 | 10 | 53 ± 38 | 14 ± 1.1 | +70 | −8 | −5 | −5 |

See the Supporting Information for more details on SEM analysis of Pt loading, Pt particle density, Pt surface area, Pt coverage, and average Pt particle sizes and distances.

LSV performance of the MIS sample with lowest loading degraded so much that the photocurrent did not reach 10 mA cm−2.

IMIS photoelectrodes with varied SiOx thickness and a constant Pt particle loading of 5 μg cm−2 were also fabricated to view the influence of SiOx thickness on PEC performance. Figure 2d shows LSV curves for IMIS samples with 2, 5, or 10 nm of SiOx layers. Although the onset potential of the LSV curves changed very little, there was a notable increase in the limiting photocurrent upon addition of just 2 nm of SiOx, which can be attributed to reduced reflection losses due to the presence of the thicker UV-ozone SiOx layer compared to the native SiO2/Si interface. Increasing overlayer thickness beyond 2 nm resulted in a nominal increase in limiting photocurrent. More importantly, the thicker SiOx layers did not cause any decrease in PEC performance by limiting mass transport of protons to the Pt surface. This observation may have two explanations. First, some of the larger, dendritic Pt particles may not be entirely covered by the SiOx overlayer, meaning that proton transport from the bulk electrolyte will be unimpeded for those particles. In the case of encapsulated Pt nanoparticles, such as that shown in Figure 1b, facile proton transport may also take place by diffusion through the thin SiOx overlayer. This explanation is consistent with evidence from previous studies that have reported the presence of proton and water transport through thin SiO2 layers that were used to encapsulate Pt microelectrodes54 and Pt oxygen reduction reaction catalysts.47 It should also be noted that the SiOx thin films fabricated by the same UV-ozone process used in this study have been used as selective gas separation membranes for small molecules.52,53,55

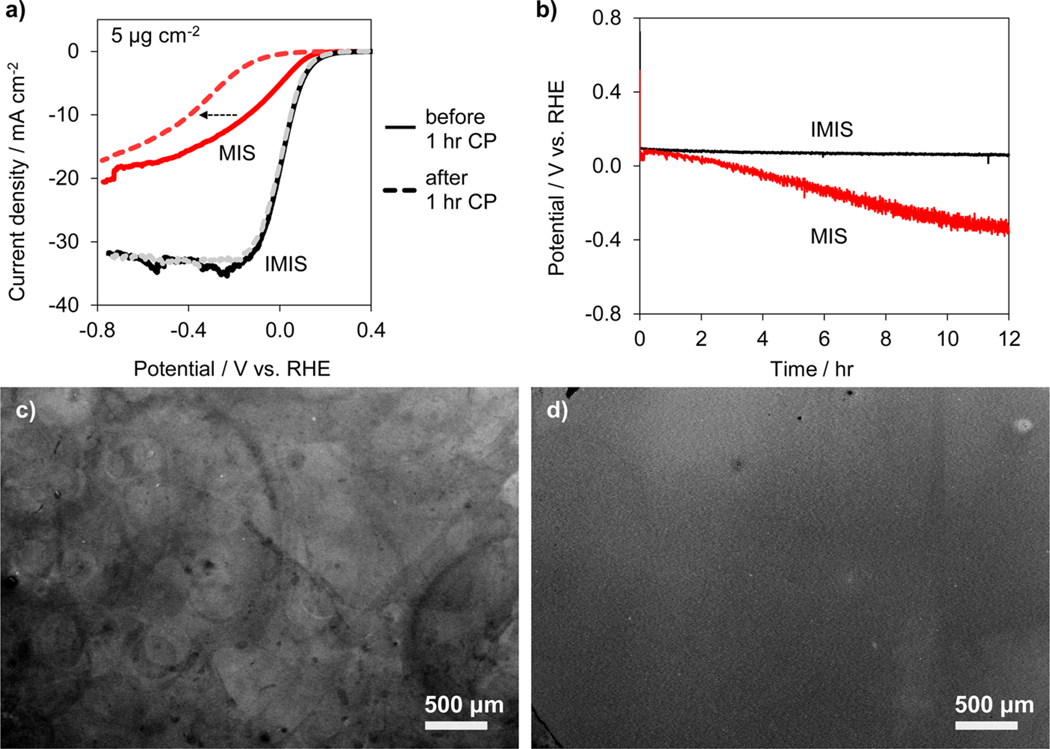

The short-term stability of MIS and IMIS photocathodes was first evaluated by conducting two additional LSVs immediately following the LSVs of Figure 2 (Figure S8). The change in operating potentials at −10 mA cm−2 between the first and third LSV are compared in Table 1. All of the MIS samples exhibited substantial instability in these measurements, with the operating potential shifting more negative by 30–200 mV at an operating current of −10 mA cm−2. The 20 μg cm−2 MIS sample showed substantially less degradation in performance than the 1 μg cm−2 sample. In contrast to MIS photoelectrodes, all of the IMIS photoelectrodes demonstrated excellent stability, with very little change in operating potential (8–40 mV) between the first and third LSV curves. The stability was also investigated under a constant applied current (chronopotentiometry (CP)) over the course of 1 h, during which time the samples were intermittently subjected to open circuit operation to simulate the periodic cycling conditions in a real device (Figure S9). The operating potential of the MIS samples decreased at 45–140 mV h−1, whereas the IMIS samples exhibited excellent stability (5–14 mV h−1). The changes in operating potentials for all samples are compared in Table 1. Interestingly, the change in operating potential at −10 mA cm−2 for the MIS samples during the 1 h CP test was very small compared to the >110 mV shifts in potential observed in LSV curves before and after the 1 h CP test (Figures 3a and S10). This observation indicates that operating the MIS photoelectrodes under potential cycling is far more detrimental than continuous operation at a set current density or potential. In a separate experiment, the long-term stability of freshly prepared 12 μg Pt cm−2 MIS and IMIS photoelectrodes was investigated by monitoring the change in operating potential required to sustain −10 mA cm−2 during a 12 h CP measurement (Figure 3b). The operating potential of the MIS electrode decreased at 40 mV h−1, whereas the IMIS electrode remained very stable, only a 2.5 mV h−1 decrease, for the duration of the 12 h test.

Figure 3.

MIS and IMIS stability. (a) LSV measurements for MIS (red) and IMIS (black) samples with 5 μg cm−2 Pt loading before (solid lines) and after (dashed lines) the 1 h CP stability test conducted at −10 mA cm−2 for 1 h. The IMIS sample was fabricated with a 10 nm thick SiOx overlayer, and the LSV sweep rate was 20 mV s−1. (b) CP stability measurements for MIS (gray curve) and IMIS (black curve) samples with 12 μg cm−2 Pt loading operating at −10 mA cm−2 for 12 h. Measurements performed in 0.5 mol L–1 H2SO4 under simulated AM 1.5 G illumination. Low resolution SEM images of (c) MIS and (d) IMIS samples after the 12 h CP stability test.

The results of Figures 2 and 3 highlight the ability of the IMIS photoelectrode architecture to be employed for stable and efficient PEC energy conversion, but also raise three underlying questions: (i) Why do the electrodeposited MIS photoelectrodes have such poor LSV performance in the first place?; (ii) How does the addition of the secondary SiOx layer improve the LSV performance for IMIS photoelectrodes?; and (iii) Why are IMIS photoelectrodes so much more stable than MIS photoelectrodes?

In addressing the first two questions, it is useful to recall the four fundamental processes illustrated in Figure 1c that are essential to MIS photoelectrode operation: (i) light absorption/electron–hole generation, (ii) minority carrier transport to the MIS junction, (iii) tunneling across the insulator, and (iv) electrocatalytic charge transfer at the electrode/electrolyte interface. UV–vis and LSV measurements performed on control samples consisting of electrodeposited Pt particles on transparent indium tin oxide reveal that neither light absorption nor kinetic overpotential losses can explain the poor performance of the MIS photoelectrodes. These measurements show that the 5 μg cm−2 Pt loading possesses >85% light transmittance across the visible wavelengths (Figure S11a) and is capable of achieving −10 mA cm−2 with less than 40 mV kinetic overpotential loss (Figure S11b). Differences in carrier collection efficiency between the MIS and IMIS samples can also be ruled out because the effective minority carrier diffusion length of both samples was found to be nearly identical (Le ≈ 103 μm, see Figure S12). This distance is far greater than the average distance between adjacent particles (<1 μm), meaning that the carrier collection efficiency in both samples should be similar.

At first glance, one would not expect that tunneling of carriers through the native SiO2 layer would be a major source of inefficiency in the MIS photoelectrodes because the tunneling probability through an SiO2 layer of thickness ≈1.5 nm is very high,50,56 and many MIS photovoltaic (PV) cells have been reported with excellent fill factors.57–61 However, the key distinction between the aforementioned studies and the MIS photoelectrodes investigated in this work is the mismatch between the illuminated area and the MIS junction area. In most MIS PV cells and photoelectrodes demonstrated to date, the MIS junction (Aj) area is similar or equal to the illuminated area (Ahv), meaning that the current density that is normalized by the junction area (Ij = I/Aj) is very similar to the photogenerated current density that is normalized by the illuminated area (IL = I/Ahv). Under AM 1.5 illumination, these current densities are typically 25–40 mA cm−2 for c-Si. However, the photoelectrodes investigated in this work have a relatively small coverage of Pt particles, meaning that the net junction area is significantly smaller than the illuminated area (Aj ≪ Ahv). The consequence of this inequality is that Ij can substantially deviate from IL, as described by eq 1:

| (1) |

In this work, the upper limit of Aj can be estimated as the net area covered by Pt particles, which was determined from the projected 2D area of Pt particles in SEM images. Taking as an example the 1 μg cm−2 Pt MIS sample with θPt = 0.03 and IL ≈ 21 mA cm−2 illuminated area, the sample-averaged limiting current density through the MIS nanojunctions is −700 mA per cm2 of junction area (Figure S13). This current density is likely to be even larger when one considers that the physical contact area between the electrodeposited Pt particles and SiO2 substrate is smaller than that indicated by SEM images (Figure S5). At such high local current densities, voltage losses due to tunneling will be significant, even for tunneling through a very thin 1.5 nm thick SiO2 insulator (Figure S14).26

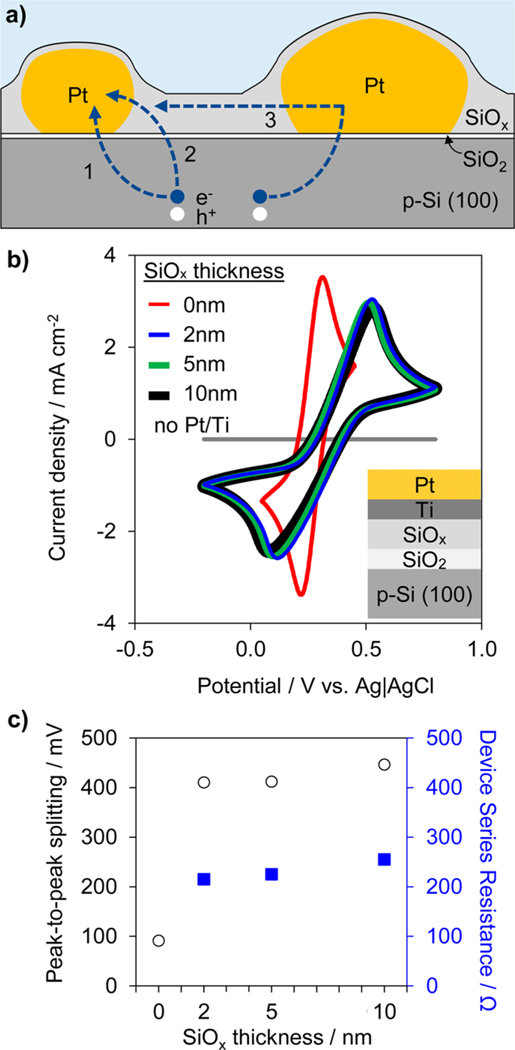

For the reasons highlighted above, we conclude that the poor I–E performance of the MIS photoelectrodes is explained by large voltage drops needed to support high local current density across the MIS nanojunctions. It follows that the presence of the SiOx overlayer substantially decreases or eliminates these tunneling-related voltage drops in the IMIS samples, but how? One possibility is that the SiOx overlayer is moderately conductive, providing additional pathways through which minority carriers can reach the Pt nanoparticles (Figure 4a). This has the effect of increasing the effective MIS junction area, thereby reducing the local tunneling current densities directly underneath the Pt particles. In addition to the conventional charge transfer pathway (Figure 4a, path 1), we hypothesize that the SiOx overlayer enables carriers to reach a given Pt particle by tunneling from the p-Si to the SiOx (Figure 4a, path 2), and possibly by lateral transport along SiOx between neighboring Pt particles (Figure 4a, path 3). In this latter case, the SiOx overlayer can serve to distribute electrons between particles, especially those not in intimate electrical contact with the substrate.

Figure 4.

Analyzing carrier transport pathways. (a) Schematic side view of IMIS photoelectrode illustrating possible charge transfer pathways between the Si substrate and Pt nanoparticles. Pathways include (1) conventional tunneling through MIS nanojunction and (2, 3) alternative charge transfer routes involving conduction through the SiOx. (b) CV measurements in 10 mmol L−1 ferri/ferrocyanide, 1 mol L−1 KCl solution for 3 nm Pt/2 nm Ti/“x” nm SiOx/native SiO2/p-Si(100) for various SiOx thicknesses from 0 to 10 nm. The CV sweep rate was 100 mV s−1. (c) Peak-to-peak splitting voltage (circles) and corresponding charge transfer resistances (squares) associated with the CV curves in b.

The viability of the proposed alternative electron transport pathways is contingent upon the electronic conductivity of the SiOx overlayer material. Pure SiO2 is an excellent insulator,62 but defects, impurities, or slight variation in stoichiometry may change this. In this study, it is likely that traces of carbonaceous impurities remaining in the spin-coated SiOx overlayers provide some degree of electrical conductivity. Indeed, XPS analysis of control samples with spin-coated SiOx contain 30% higher C 1s signal compared to samples containing native SiO2 where the carbon only arises from adventitious carbon species. Furthermore, it is likely that the highest amount of unconverted carbon will remain in the SiOx layer immediately surrounding the Pt particles due to shadowing during the UV-ozone process, thus providing the highest conductivity at the MIS nanojunction where it is most needed. Another source of conductivity in the SiOx layer could be protons or hydrogen atoms taken up from the acidic electrolyte. Previous studies have proposed that protons in silicon dioxide may be reduced to hydrogen atoms, which then serve as electron mediators for electrochemical reduction as demonstrated with 6 nm thick thermally grown SiO2.63 Furthermore, the presence of Si–H bonds within SiO2 have been found to increase tunneling current through chemical SiO2,64 which could also facilitate charge transfer in this study.

The conductivity of the SiOx overlayer was investigated with cyclic voltammetry (CV) to measure charge transfer rates across continuous SiOx films of varying thickness using a standard ferri/ferrocyanide redox couple, as previously used to evaluate the conductivity of ALD TiO2 layers in MIS photoanodes.18,65 These measurements were conducted on a series of samples on which a bilayer film of 1 nm of Ti and 3 nm of Pt were sequentially deposited by physical vapor deposition onto “x” nm SiOx/native SiO2/p-Si electrodes (0 nm < x < 10 nm), as depicted in the inset of Figure 4b. The electron transfer kinetics of ferri/ferrocyanide at the surface of the Pt top layer are very fast such that the largest source of resistance is associated with charge transfer across the SiO2/SiOx stack. A control sample lacking the catalytic Pt layer exhibits orders of magnitude lower current density and no observable Fe2+/Fe3+ redox features. As seen in Figure 4b, the CV for the control sample with 0 nm of SiOx demonstrated relatively small peak-to-peak splitting (<100 mV). However, the addition of 2 nm of SiOx resulted in an increase in the peak-to-peak splitting to 410 mV, indicating a significant increase in charge transfer resistance across the stack. Interestingly, increasing the SiOx thickness beyond 2 nm did not lead to a significant increase in peak-to-peak splitting. The lack of sensitivity of the charge transfer resistance on the SiOx thickness suggests that the SiOx does not behave like a typical tunneling oxide, for which increasing oxide thickness should lead to an exponential decay in tunneling current and exponential increase in peak-to-peak splitting.18,19,65 Instead, the nearly constant peak-to-peak splitting for all three SiOx layer thicknesses indicates the SiOx layer is moderately conductive and that the effective charge transfer resistance associated with conduction across the SiOx is very small compared to that associated with tunneling between the p-Si substrate and SiOx overlayer (Figure 4c and Figure S15). Thus, the measurements in Figure 4 support the hypothesis that the spin-coated SiOx layer enables additional charge transfer pathways between the Si substrate and Pt nanoparticles, thereby reducing the voltage drops needed for tunneling across the MIS nanojunctions at high current densities. It should be noted that the initial increase in charge transfer resistance upon deposition of the first 2 nm of SiOx can be explained by a decrease in the tunneling probability across the native SiO2 layer due to a decrease in density of states of SiOx compared to the metallic Pt/Ti layer.

The source of poor stability for the uncoated MIS photoelectrodes is less clear, with possible explanations including catalyst poisoning, particle detachment, and reduced quality of the electrical contact. Control samples based on Pt particles electrodeposited on ITO/glass substrates reveal no loss in catalytic activity during HER experiments (Figure S11b), supporting the conclusion from the stable operation of the IMIS samples that the Pt particles are not being poisoned by a contaminant in the system. In addition, the possible role of the SiOx layer to serve as a “glue” to physically adhere the nanoparticles to the substrate during operation was evaluated by taking SEM images of identical locations on a MIS photoelectrode before and after three consecutive LSVs in 0.5 mol L−1 H2SO4. Despite significant decrease in performance of the MIS photoelectrode during these measurements, these images reveal no substantial particle detachment over this short time period (Figure S16). In contrast, SEM images taken after the longer 12 h CP stability test (Figure 3c,d) suggest that particle adhesion does become an issue over longer time periods. These SEM images reveal a highly nonuniform Pt distribution on the surface of the MIS photoelectrode and a uniform Pt distribution on the IMIS photoelectrode, suggesting Pt particle migration and/or detachment from the MIS surface. Large circular features are also evident on the MIS photoelectrode surface, which may correspond with the location of H2 bubbles that remained attached to the photoelectrode surface for prolonged times. It is possible that H2 bubbles on MIS electrodes reduce the ECSA, forcing higher local current densities through accessible Pt nanoparticles near the bubble edges and thereby accelerating local degradation. In the case for IMIS electrodes, small H2 bubbles are also present on the surface, but the hydrophilic SiOx overlayer facilitates bubble detachment at smaller diameters and reduces its average residence time on the photoelectrode surface. This facile bubble removal is evident in the IMIS chronopotentiometry stability tests, where the stochastic fluctuations associated with bubble dynamics are very small in comparison to those observed for the MIS electrode (Figures 3b and S9a). This observation suggests a detrimental role of surface-bound H2 bubbles on the durability of the uncoated Pt nanoparticles.

Another possible cause of instability is degradation of the SiO2 and/or the SiO2/Si interface at MIS junctions resulting from heat dissipation under conditions of high local tunneling current densities that are present in samples with low and medium Pt loadings, and MIS electrodes masked with H2 bubbles. Typically, such thermal degradation of MIS junctions is observed in solid-state devices that undergo oxide breakdown and dielectric breakdown-induced epitaxy (DBIE) of the Si substrate66–68 under application of a large reverse bias69 or current surge.70 It is possible that the large photodriven current densities present in our samples could lead to similar phase change effects or particle detachment due to heat dissipation associated with the tunneling across the SiO2 insulating layer.

Regardless of the exact mechanism by which MIS sample performance degraded, it was consistently observed that the extent of performance degradation was proportional to the current density through the MIS nanojunctions. This was already noted in Table 1, which shows that performance degradation decreased with increasing Pt particle loading. In order to investigate this relationship further, MIS electrodes with 11% and 30% Pt coverages were tested in 0.5 mol L−1 H2SO4 under 0.25 and 1 sun intensities to systematically vary the current densities through the junctions (Figure S17). At 0.25 sun intensity, corresponding to low current density through the junction, both electrodes remained reasonably stable during the 5 CV cycles. However, upon operation under 1 sun illumination, corresponding to higher current density, the performance degraded after just 1 cycle. Importantly, the performance degradation was far greater for the MIS sample with low Pt loading and at high light intensity. The observations of poor stability for higher light intensity and/or lower loading thus indicate that degradation is greatest when the current density through the nanojunctions is highest. In IMIS electrodes, the SiOx overlayer may alleviate this issue by decreasing local current densities through the MIS nanojunctions. Our observations are consistent with both thermally induced degradation, as well as H- or H2 induced damage, which are expected to be more prominent at higher current densities.

In summary, this study has described a room-temperature and scalable means of stabilizing electrodeposited Pt nanoparticle catalysts on an insulating substrate for MIS photoelectrodes for solar water splitting. The enhanced performance with the SiOx overlayer modification indicates improved carrier transport between the native SiO2/p-Si substrate and the electrodeposited Pt nanoparticles. Additionally, the IMIS photoelectrodes exhibit excellent stability, while the unmodified MIS photoelectrodes undergo gradual performance degradation related to the presence of H2 bubbles on the photoelectrode surface. We hypothesize that the improved current–potential performance of the IMIS samples results from a decrease in tunneling losses across the MIS nanojunctions, which is made possible by an increase in the effective junction area between the substrate and Pt particles. Based on this proposed mechanism, we expect that the IMIS approach will be broadly applicable to improving the efficiency and stability of MIS photoelectrodes based on low-loadings of nanoparticle catalysts.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge Chathuranga De Silva for assistance with XPS measurements. D.V.E. and N.Y.L. acknowledge Columbia University (start-up funds) and the National Science Foundation (NSF) Center for Precision Assembly of Superstratic and Superatomic Solids for funding (DMR-1420634).

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.6b02909.

(I) SiOx/Pt/native SiO2/Si synthesis procedures, (II) characterization of MIS and IMIS samples, (III) photoelectrochemical characterization, (IV) understanding origins of poor PEC performance by MIS photoelectrodes, (V) understanding degradation in PEC performance of MIS photoelectrodes (PDF)

REFERENCES

- (1).Lewis NS; Nocera DG Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2006, 103 (43), 15729–15735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Safaei H; Keith DW Energy Environ. Sci. 2015, 8, 3409. [Google Scholar]

- (3).Newman J; Hoertz PG; Bonino C.a.; Trainham JA. J. Electrochem. Soc 2012, 159 (10), A1722–A1729. [Google Scholar]

- (4).Chen X; Shen S; Guo L; Mao SS Chem. Rev. 2010, 110 (11), 6503–6570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Walter MG; Warren EL; McKone JR; Boettcher SW; Mi Q; Santori EA; Lewis NS Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 6446–6473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Gratzel M Nature 2001, 414, 338–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Turner J; Sverdrup G; Mann MK; Maness P-C; Kroposki B; Ghirardi M; Evans RJ; Blake D Int. J. Energy Res. 2008, 32, 379–407. [Google Scholar]

- (8).McKone JR; Lewis NS; Gray HB Chem. Mater. 2014, 26, 407–414. [Google Scholar]

- (9).Lewis NS Electrochem. Soc. 2013, 43–49. [Google Scholar]

- (10).Pinaud BA; Benck JD; Seitz LC; Forman AJ; Chen Z; Deutsch TG; James BD; Baum KN; Baum GN; Ardo S; Wang H; Miller E; Jaramillo TF Energy Environ. Sci. 2013, 6, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- (11).Zhu T; Chong MN Nano Energy 2015, 12, 347–373. [Google Scholar]

- (12).Muñoz AG; Lewerenz HJ ChemPhysChem 2010, 11 (8), 1603–1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Lewerenz HJ; Skorupska K; Muñoz AG; Stempel T; Nüsse N; Lublow M; Vo-Dinh T; Kulesza P Electrochim. Acta 2011, 56, 10726–10736. [Google Scholar]

- (14).Esposito DV; Levin I; Moffat TP; Talin AA Nat. Mater. 2013, 12 (6), 562–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Kenney MJ; Gong M; Li Y; Wu JZ; Feng J; Lanza M; Dai H Science 2013, 342 (6160), 836–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Choi MJ; Jung J-Y; Park M-J; Song J-W; Lee J-H; Bang JH J. Mater. Chem. A 2014, 2, 2928. [Google Scholar]

- (17).Hill JC; Landers AT; Switzer JA Nat. Mater. 2015, 14, 6751–6755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Chen YW; Prange JD; Dühnen S; Park Y; Gunji M; Chidsey CED; McIntyre PC Nat. Mater. 2011, 10 (7), 539–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Scheuermann AG; Prange JD; Gunji M; Chidsey CED; McIntyre PC Energy Environ. Sci. 2013, 4 (8), 1166–1169. [Google Scholar]

- (20).Hu S; Shaner MR; Beardslee JA; Lichterman M; Brunschwig BS; Lewis NS Science 2014, 344 (6187), 1005–1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Boettcher SW; Warren EL; Putnam MC; Santori EA; Turner-Evans D; Kelzenberg MD; Walter MG; McKone JR; Brunschwig BS; Atwater H.a.; Lewis NS J. Am. Chem. Soc 2011, 133, 1216–1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Seger B; Laursen AB; Vesborg PCK; Pedersen T; Hansen O; Dahl S; Chorkendorff I Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2012, 51 (36), 9128–9131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Seger B; Pedersen T; Laursen AB; Vesborg PCKK; Hansen O; Chorkendorff IJ Am. Chem. Soc 2013, 135 (3), 1057–1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Laursen AB; Pedersen T; Malacrida P; Seger B; Hansen O; Vesborg PCK; Chorkendorff I Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys 2013, 15 (46), 20000–20004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Ji L; McDaniel MD; Wang S; Posadas AB; Li X; Huang H; Lee JC; Demkov AA; Bard AJ; Ekerdt JG; Yu ET Nat. Nanotechnol. 2014, 10 (1), 84–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Singh R; Green MA; Rajkanan K Sol. Cells 1981, 3 (2), 95–148. [Google Scholar]

- (27).Dominey RN; Lewis NS; Bruce JA; Bookbinder DC; Wrighton MS J. Am. Chem. Soc 1982, 104, 467–482. [Google Scholar]

- (28).Szklarczyk M; Bockris JO J. Phys. Chem 1984, 88, 1808–1815. [Google Scholar]

- (29).Heller A Science 1984, 223, 1141–1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).McCrory CCL; Jung S; Ferrer IM; Chatman SM; Peters JC; Jaramillo TF J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137 (13), 4347–4357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Shao-Horn Y; Sheng WC; Chen S; Ferreira PJ; Holby EF; Morgan D Top. Catal. 2007, 46 (3–4), 285–305. [Google Scholar]

- (32).Vesborg PCK; Jaramillo TF RSC Adv. 2012, 2 (21), 7933. [Google Scholar]

- (33).Heller A; Aspnes DE; Porter JD; Sheng TT; Vadimsky RG J. Phys. Chem 1985, 89 (1982), 4444–4452. [Google Scholar]

- (34).Nakato Y; Ueda K; Yano H; Tsubomura HJ Phys. Chem. 1988, 92, 2316–2324. [Google Scholar]

- (35).Nakato Y; Tsubomura H Electrochim. Acta 1992, 37, 897–907. [Google Scholar]

- (36).Nakato Y; Yano H; Nishiura S; Ueda T; Tsubomura HJ Electroanal. Chem. Interfacial Electrochem. 1987, 228, 97–108. [Google Scholar]

- (37).Rossi RC; Tan MX; Lewis NS Appl. Phys. Lett 2000, 77, 2698. [Google Scholar]

- (38).Oskam G; Long JG; Natarajan A; Searson PC J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys 1998, 31, 1927–1949. [Google Scholar]

- (39).Kawamura YL; Sakka T; Ogata YH J. Electrochem. Soc. 2005, 152, C701. [Google Scholar]

- (40).Aggour M; Skorupska K; Stempel Pereira T; Jungblut H; Grzanna J; Lewerenz HJ J. Electrochem. Soc 2007, 154 (9), H794–H797. [Google Scholar]

- (41).Liu YH; Gokcen D; Bertocci U; Moffat TP Science (Washington, DC, U. S.) 2012, 338, 1327–1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Arrington D; Curry M; Street S; Pattanaik G; Zangari G Electrochim. Acta 2008, 53 (5), 2644–2649. [Google Scholar]

- (43).Mirley C; Koberstein J Langmuir 1995, 11 (4), 1049–1052. [Google Scholar]

- (44).Gould TD; Izar A; Weimer AW; Falconer JL; Medlin JW ACS Catal. 2014, 4, 2714–2717. [Google Scholar]

- (45).Joo SH; Park JY; Tsung C-K; Yamada Y; Yang P; Somorjai GA Nat. Mater. 2009, 8 (2), 126–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Dai Y; Lim B; Yang Y; Cobley CM; Li W; Cho EC; Grayson B; Fanson PT; Campbell CT; Sun Y; Xia Y Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2010, 49 (44), 8165–8168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Takenaka S; Miyamoto H; Utsunomiya Y; Matsune H; Kishida MJ Phys. Chem. C 2014, 118 (2), 774–783. [Google Scholar]

- (48).Maeda K; Teramura K; Lu D; Saito N; Inoue Y; Domen K Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2006, 45, 7806–7809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Agiral A; Soo HS; Frei H Chem. Mater. 2013, 25 (11), 2264–2273. [Google Scholar]

- (50).Shewchun J; Singh R; Green MA J. Appl. Phys 1977, 48 (2), 765. [Google Scholar]

- (51).Ouyang M; Yuan C; Muisener RJ; Boulares A; Koberstein JT Chem. Mater. 2000, 12 (29), 1591–1596. [Google Scholar]

- (52).Ouyang M; Muisener RJ; Boulares A; Koberstein JT J. Membr. Sci 2000, 177 (1–2), 177–187. [Google Scholar]

- (53).Ouyang M; Klemchuk PP; Koberstein JT Polym. Degrad. Stab 2000, 70, 217–228. [Google Scholar]

- (54).Velmurugan J; Zhan D; Mirkin MV Nat. Chem. 2010, 2 (6), 498–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Houston KS; Weinkauf DH; Stewart FF J. Membr. Sci 2002, 205, 103–112. [Google Scholar]

- (56).Green MA; King FD; Shewchun J Solid-State Electron. 1974, 17, 551–561. [Google Scholar]

- (57).Hezel R Prog. Photovoltaics 1997, 5, 109–120. [Google Scholar]

- (58).Har-Lavan R; Ron I; Thieblemont F; Cahen D Appl. Phys. Lett 2009, 94 (4), 43308. [Google Scholar]

- (59).Kim KH; Kim HJ; Jang P; Jung C; Seomoon K Electron. Mater. Lett 2011, 7 (2), 171–174. [Google Scholar]

- (60).Jung Y; Li X; Rajan NK; Taylor AD; Reed M.a. Nano Lett. 2013, 13, 95–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).García De Arquer FP; Mihi A; Kufer D; Konstantatos G ACS Nano 2013, 7 (4), 3581–3588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Verwey JF; Amerasekera EA; Bisschop J Rep. Prog. Phys 1990, 53, 1297–1331. [Google Scholar]

- (63).Lee J; Lee JG; Lee S; Seo M; Piao L; Bae JH; Lim SY; Park YJ; Chung TD Nat. Commun. 2013, 4 (May), 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (64).Hattori T; Watanabe K; Ohashi M; Matsuda M; Yasutake M Appl. Surf. Sci 1996, 102 (96), 86–89. [Google Scholar]

- (65).Scheuermann A; Kemp K; Tang K; Lu D; Satterthwaite P; Ito T; Chidsey CED; Mc Intyre P Energy Environ. Sci 2016, 9, 504. [Google Scholar]

- (66).Selvarajoo TAL; Ranjan R; Pey KL; Tang LJ; Tung CH; Lin W IEEE Trans. Device Mater. Reliab 2005, 5, 190–197. [Google Scholar]

- (67).Pey KL; Tung CH; Radhakrishnan MK; Tang LJ; Lin WH Int. Electron Devices Meet. 2002, 1 (C), 163–166. [Google Scholar]

- (68).Azizi N; Yiannacouras P ECE1768–Reliability Integr. Circuits 2003, 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- (69).Lombardo S; Crupi F; La Magna A; Spinella C; Terrasi A; La Mantia A; Neri BJ Appl. Phys. 1998, 84 (1), 472. [Google Scholar]

- (70).Ranjan R; Pey KL; Tung CH; Tang LJ; Ang DS; Groeseneken G; De Gendt S; Bera LK Appl. Phys. Lett 2005, 87 (24), 242907. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.