We provide the first genetic evidence that LSD1 in skeletal cells is critical for endochondral ossification during bone repair.

Abstract

Bone fracture is repaired predominantly through endochondral ossification. However, the regulation of endochondral ossification by key factors during fracture healing remains largely enigmatic. Here, we identify histone modification enzyme LSD1 as a critical factor regulating endochondral ossification during bone regeneration. Loss of LSD1 in Prx1 lineage cells severely impaired bone fracture healing. Mechanistically, LSD1 tightly controls retinoic acid signaling through regulation of Aldh1a2 expression level. The increased retinoic acid signaling in LSD1-deficient mice suppressed SOX9 expression and impeded the cartilaginous callus formation during fracture repair. The discovery that LSD1 can regulate endochondral ossification during fracture healing will benefit the understanding of bone regeneration and have implications for regenerative medicine.

INTRODUCTION

Bone fractures are common injuries caused by high-force impact or stress, and many diseases, such as osteoporosis or certain cancers, can cause increased risk for bone injury (1, 2). Bone can rapidly and efficiently repair itself; however, 5 to 10% of fracture cases have impaired healing, such as delayed fusion or nonunion, which leads to additional surgery, morbidity, and decreased quality of life (3). Clinical studies have shown that many health conditions, including diabetes, hypothyroidism, aging, and vascular disease, are related to fracture healing defects (4). To begin to address this clinical problem, it is important to understand what regulatory signaling pathways are necessary for bone regenerative cells to promote bone regeneration upon injury.

Bone fracture healing recapitulates many facets of bone formation during embryonic development, as both intramembranous and endochondral bone formation contribute to fracture repair (5). Intramembranous bone formation occurs immediately adjacent to the broken ends of the bone, whereas skeletal progenitors directly differentiate to osteoblasts. Endochondral bone formation initiates in the gap region where periosteal cells turn into chondrocytes and form the cartilaginous callus, which is subsequently mineralized and replaced by a bony hard callus (6).The periosteum harbors stem cells responsible for skeletal repair (7–9). Genetic mouse models and lineage-tracing techniques have identified several markers that label the periosteal cells during bone regeneration. Prx1, Ctsk, LepR, aSMA, DKK3, or Gli1-lineage cells all mark periosteal cells that contribute to chondrocytes and osteoblasts in the fracture callus (7, 8, 10–16). Prx1 lineage cells have been reported to be a main source for fracture healing as almost all the callus cellular components are derived from Prx1 lineage cells, and deletion of Rbpj or Runx1 in these cells led to impaired fracture callus formation (7, 8, 17–19). In addition, Prx1+ periosteal cells overlap with the newly identified myxovirus resistance-1 (Mx1) and alpha smooth muscle actin (a-SMA) periosteal skeletal stem cells (20). Although the importance of Prx1 cells in fracture repair is known, the molecular pathways they follow to perform this function is still unknown.

Epigenetic regulation of bone progenitors plays important roles in bone homeostasis. Lysine-specific histone demethylase 1A (LSD1) was the first found histone demethylase that specifically catalyzes the demethylation of H3K4me1 and H3K4me2 and generally functions as a transcriptional repressor (21). A previous study demonstrated that mice with LSD1 deletion in bone progenitors exhibited high bone mass due to increased osteoblast differentiation during bone development (22), while the role of LSD1 in periosteal cells under bone regeneration is yet to be determined.

In this study, we uncovered LSD1 as a key regulator for Prx1 lineage cells to repair bone injury. LSD1 can restrain retinoic acid (RA) signaling in fracture healing cells through directly targeting and suppressing Aldh1a2 via histone modification. Loss of LSD1 increased RA signaling, which led to decreased SOX9 level and impaired cartilaginous callus formation, thus resulting in fracture nonunion.

RESULTS

LSD1 deletion in Prx1 lineage cells leads to impaired bone fracture healing

Histone demethylation enzyme LSD1 plays important roles in bone homeostasis (22). To explore the role of LSD1 in fracture healing, we deleted LSD1 in fracture healing cells using Prx1-Cre mice. We performed unilateral femoral fractures on 6-week-old Lsd1fl/fl control mice and Prx1-cre; Lsd1fl/fl mice (Lsd1Prx1). The healing process was monitored by serial x-rays every 7 days, and we used the callus index (CI), defined as the maximum diameter of callus divided by the diameter of adjacent diaphysis, to measure callus formation over time. In control mice, a hard tissue callus was evident at the fracture site at 14 days post fracture (dpf), and it gradually decreased in size reflecting a remodeling process (Fig. 1, A and B). Unexpectedly, the callus in Lsd1Prx1 mice was hardly discernible at 14 dpf and also at later time points (Fig. 1, A and B). To further study the mineralized callus formation, we performed micro–computed tomography (μCT) analyses and found that Lsd1Prx1 mice exhibited impaired hard callus formation at 14 dpf and fracture nonunion at 42 dpf (Fig. 1C). In addition, Lsd1Prx1 mice showed a decrease in the total fracture callus bone volume compared with control mice (Fig. 1D). To examine the structural property of the repaired bones, we applied biomechanical torsion test on fractured femur isolated at 42 dpf from Lsd1Prx1 and control mice. As expected, the femur bone maximum torque was notably lower in Lsd1Prx1 mice (fig. S1A). The callus of Prx1-Cre; Lsd1fl/+ mice underwent a normal healing process (fig. S1, B and C), indicating that the abnormal healing process in Lsd1Prx1 mice was from the deletion of the Lsd1 gene in Prx1-Cre cells and not from the expression of Cre recombinase. Together, these data suggest that the expression of LSD1 in Prx1 lineage cells is required for bone fracture healing.

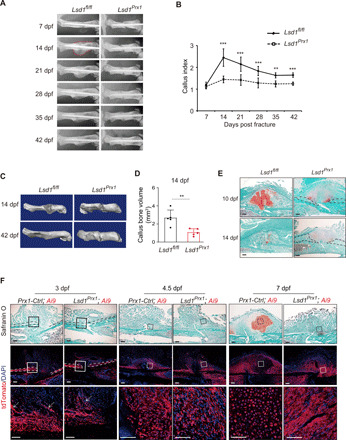

Fig. 1. LSD1 is required for cartilaginous callus formation during bone fracture healing.

(A) Temporal radiographic analysis of fractured femurs in Lsd1Prx1 and control mice. (B) CI calculated from radiographic data showed the callus formation at different time points of mutant and control mice. n = 6 for each group. Data are presented as means ± SD (n = 8). Unpaired t test, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001. (C) Reconstruction of μCT data reflected hard bony callus formation at 14 dpf and 42 dpf in mutant and control mice. (D) Graphs show callus bone volume of Lsd1Prx1 and control mice at 14 dpf. Two-tailed Student’s t test. Data are means ± SD. n = 5/6. (E) Safranin O staining showed the cartilage callus formation from Lsd1Prx1 and control mice fractured femurs at 10 and 14 dpf. n = 3 mice per genotype per time point. Scale bars, 100 μm. (F) Fluorescence label of Prx1 lineage cells (tdTomato+ cells) at the injury site from Lsd1Prx1 and control mice fractured femurs at 3, 4.5, and 7 dpf. n = 3 mice per genotype per time point. Scale bars, 100 μm.

To assess how LSD1 deletion affected bone fracture healing, we performed histological analysis at different time points in Lsd1Prx1 and control mice. A robust cartilaginous callus was formed in the fracture sites of Lsd1fl/fl control mice at 10 dpf, as indicated by Safranin O staining, and the cartilage was then replaced by woven bone at 14 dpf (Fig. 1E). In contrast, cartilage formation was greatly impaired in Lsd1Prx1 mice as there was no integrated cartilage established during the healing process, and only small islands of chondrocytes were identified (Fig. 1E). Intramembranous bone formation at the fracture site proceeded normally, which suggests that loss of LSD1 mainly affected endochondral bone formation during fracture healing (Fig. 1E, black dash).

The impaired cartilaginous callus formation and abnormal bone fracture healing in Lsd1Prx1 mice prompted us to examine the contribution of Prx1 lineage cells in Lsd1Prx1 mice during bone fracture healing. To this end, we examined Prx1 lineage cells at the fracture site 1 to 7 dpf in Prx1-Cre; Lsd1fl/fl (Lsd1Prx1) and Prx1-Cre; Lsd1fl/+ mice (Prx1-Ctrl) with the Ai9 reporter, which expresses tdTomato following Cre-mediated recombination (fig. S1D) (23). The results showed that the expansion of periosteum adjacent to the fracture site happened normally in both Lsd1Prx1; Ai9 and Prx1-Ctrl; Ai9 mice from 1 to 3 dpf (Fig. 1F and fig. S2A). In addition, fibroblast-like cells accumulated at the injury site with no obvious difference between groups at 4.5 dpf, indicating that deletion of LSD1 did not affect the accumulation of Prx1-Cre cells at the injury site in early phases (Fig. 1F). At 7dpf, Prx1-Ctrl; Ai9 mice formed a cartilaginous callus, while Lsd1Prx1; Ai9 mice stayed at a fibrous callus stage (Fig. 1F), which indicates that loss of LSD1 inhibited the transformation from fibrous callus to cartilaginous callus. As angiogenesis is reported to have a positive effect on chondrocyte differentiation during fracture repair, we performed immunofluorescence for CD31 to evaluate the vascularization of the fracture callus. CD31 staining revealed that vessel formation in the callus was normal in Lsd1Prx1 mice (fig. S2, B to D). Together, these data suggest that LSD1 is essential for cartilaginous callus formation during fracture healing.

LSD1-deficient Prx1 lineage cells show decreased SOX9 expression during fracture healing

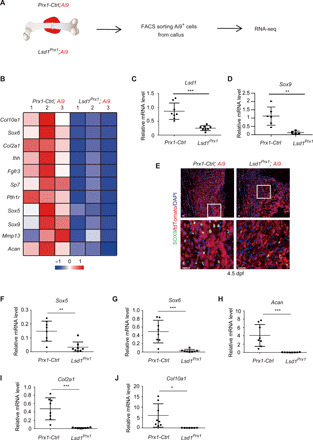

To gain mechanistic insight into what prevents cartilaginous callus formation in Lsd1Prx1; Ai9 mice, we performed RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) using Prx1 lineage cells sorted from Lsd1Prx1; Ai9 mice and Prx1-Ctrl; Ai9 mice at 4.5 dpf when periosteal cells are about to be committed to turn into chondrocytes (Fig. 2A). LSD1 protein was significantly depleted in Ai9 cells from Lsd1Prx1; Ai9 mice (fig. S3A). Comparing transcriptomes of samples from Lsd1Prx1; Ai9 mice and Prx1-Ctrl; Ai9 mice, we found that the expression of Sox9, a well-known chondrogenesis factor, was greatly repressed in cells from Lsd1Prx1; Ai9 mice (Fig. 2B), while other chondrocyte regulators including Snail1, Nkx3-2, Cebpa, Rbpj, and Stat1 showed no obvious difference between groups (fig. S3B). The reduced expression of Lsd1 and Sox9 was validated by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR; Fig. 2, C and D). To further confirm that loss of LSD1-inhibited SOX9 expression, we examined the SOX9 protein level in vivo. Lsd1Prx1; Ai9 mice exhibited less SOX9+ cells compared to the littermate controls in the fracture callus at 4.5 dpf (Fig. 2E). Consistent with the decreased expression of SOX9, the expression of SOX9 target genes and chondrocyte marker genes were greatly repressed in cells from Lsd1Prx1 mice (Fig. 2B). Differential expression of these genes was validated by reverse transcription PCR (Fig. 2, F to J). The decreased expression of Type II collagen (COLII) and Type X collagen (COLX) was confirmed by immunostaining using antibodies specific to COL2A1 and COL10A1, respectively (fig. S3, C and D).

Fig. 2. LSD1-deficient Prx1 lineage cells show decreased SOX9 expression during fracture healing.

(A) Illustration of fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) sorting of Prx1 lineage cells from Lsd1Prx1 and control mice fractured femurs at 4.5 dpf. (B) Heat map showed the differentially expressed chondrocyte-related genes in the RNA-seq samples from fractured femurs of Lsd1Prx1 and control mice. (C and D) RT-PCR analysis of the expression levels of candidate genes in Prx1-lineage callus cells sorted from fractured femur of Lsd1Prx1 and control mice at 4.5 dpf. Data are presented as means ± SD (n = 8). Unpaired t test, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001. (E) Immunofluorescence staining showed the expression of SOX9 at fracture site in Lsd1Prx1 and control mice at 4.5 dpf. n = 2 per genotype. Scale bars, 25 μm. (F to J) RT-PCR analysis of the expression levels of genes in Prx1 lineage callus cells sorted from fractured femurs of Lsd1Prx1 and control mice at 4.5 dpf. Data are presented as means ± SD (n = 8). Unpaired t test, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

LSD1 regulates the expression of SOX9

The decreased expression of SOX9 in LSD1-deficient periosteal cells prompted us to investigate the effects of LSD1 on chondrocyte differentiation. We isolated periosteal cells from 4-week-old Lsd1Prx1 mice and control mice and performed micromass culture. We found that the chondrocyte differentiation of Lsd1Prx1 cells was suppressed along with reduced expression level of Sox9 and other chondrocyte markers (Fig. 3, A and B), indicating that loss of LSD1 inhibited chondrocyte differentiation of periosteal cells. Sox9 heterozygous mutant mice display a phenotype similar to the skeletal abnormalities of human campomelic dysplasia patients (24). Strikingly, we found that the skeletal phenotypes of Lsd1Prx1 mice strongly resembled Sox9 heterozygous mice, including short and bent limbs (Fig. 3, C to E), hypoplasia of scapula (Fig. 3D), the absence of the deltoid protuberance of humerus (Fig. 3E), and expanded hypotrophic zone in the growth plate (Fig. 3F). In addition, we detected reduced SOX9 protein level at the growth plate in Lsd1Prx1 mice (Fig. 3G). In line with this, the Sox9 mRNA level was also decreased in the growth plate chondrocytes of Lsd1Prx1 mice (fig. S4A). Collectively, these data indicate that LSD1 regulates SOX9 level during bone repair and skeletal development.

Fig. 3. LSD1 regulates the expression of SOX9.

(A) Alcian blue staining of micromass culture using periosteal cells isolated from Lsd1Prx1 and control mice. n = 4. (B) Relative mRNA expression of chondrocyte marker genes at day 6 were analyzed by RT-PCR, n = 3. Unpaired t test, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001. (C to E) Skeletal preparations of newborn mice at postnatal day 2 were shown for whole skeletal (C) and limbs (D and E). Scale bars, 25 mm. (F) Growth plate sections of the tibia of Prx1-CKO and control mice (n = 3) at postnatal day 2 as shown by Safranin O staining. Scale bars, 20 μm. (G) Immunofluorescence staining showed the SOX9 protein level in the growth plate from P2 Lsd1Prx1 and control mice. n = 3. Scale bars, 20 μm.

LSD1 inhibits RA signaling through suppression of ALDH1A2

LSD1 has been suggested to act as a transcriptional suppressor to its H3K4me1/2 demethylase activity and as a transcriptional activator to its H3K9 demethylase activity (21). As loss of LSD1 did not change the H3K9 methylation levels at the Sox9 promoter region (fig. S5, A and B), we proposed that LSD1 could use its H3K4me1/2 demethylase activity to suppress signaling pathways that negatively regulate the expression of Sox9. To explore this possibility, we analyzed the RNA-seq data between Prx1-Ctrl; Ai9 and Lsd1Prx1; Ai9 callus cells to compare Wnt/notch/RA/actin polymerization signaling pathways, which have been reported as SOX9 inhibiting pathways (25–28). We found that the RA signaling pathway–related genes were enriched in Lsd1Prx1; Ai9 samples and that Aldh1a2 had the highest increase in gene expression upon deletion of LSD1 (Fig. 4A and fig. S5, C to E). ALDH1A2 (aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 family member a2) is a rate-limiting enzyme that catalyzes the synthesis of RA from retinaldehyde (29). ALDH1A2 protein was also increased in the periosteum of Lsd1Prx1 mice (fig. S6A). To measure in vivo ALDH activity in the fracture callus, we isolated 4.5 dpf callus cells from Lsd1Prx1 mice and control mice and then performed a flow cytometry–based ALDEFLUOR assay. In line with up-regulated ALDH1A2 level, the ALDH activity was increased in LSD1-deficient cells, which could be blocked by the ALDH-specific enzyme inhibitor diethylaminobenzaldehyde (DEAB; Fig. 4, B and C). Cyp26a1 is also up-regulated in Lsd1Prx samples, which encodes a RA catabolic enzyme (Fig. 4A) (30). To investigate the net effect of LSD1 loss of function on RA metabolism, we measured local and systemic serum all-trans RA (ATRA) levels at 4.5 dpf through liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). Because of limitations in the amount of callus tissue and the input requirements for this analytic technique, we were unable to determine the local ATRA level. However, an increase of systemic serum ATRA level was observed in Lsd1Prx1 mice at 4.5 dpf (Fig. 4D). In addition, to delineate whether loss of LSD1 could amplify RA signaling, we transfected Lsd1Prx1 and control cells with RARE-luc reporter and then stimulated the cells with all-trans retinal for 12 hours before measuring reporter activity. As expected, Lsd1Prx1 cells were more sensitive to retinal stimulation and exhibited increased RA signaling compared to controls (Fig. 4E). To address whether LSD1 could directly regulate Aldh1a2, we performed chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)–qPCR analysis using an LSD1-specific antibody on murine periosteal cells and found that LSD1 directly bound to the promoter region of ALdh1a2 (Fig. 4F). We next sought to explore whether the deletion of LSD1 changed the histone H3K4 methylation state on the Aldh1a2 promoter. ChIP-qPCR data showed that H3K4me2 levels were increased near the transcription start site of Aldh1a2 locus in Lsd1Prx1 cells compared to control cells (Fig. 4G), suggesting a more active transcriptional state upon LSD1 deletion. Together, our results indicate that LSD1 negatively regulates Aldh1a2 and RA signaling.

Fig. 4. LSD1 inhibits RA signaling through suppression of ALDH1A2.

(A) Quantitative expression analysis of RA signaling–related genes in the RNA-seq samples from fractured femurs of Lsd1Prx1 and control mice. (B and C) Flow cytometric analysis of ALDH activity of Prx1 lineage cells in the presence and absence of the ALDH inhibitor DEAB to show specificity. n = 4 to 6 mice per group; data represent means ± SD. ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test was performed, ***P < 0.001. (D) Concentrations of endogenous ATRA in serum of Lsd1Prx1 and Prx1-Ctrl mice by LC-MS/MS analysis. Unpaired t test was performed, n = 7 mice per group, **P < 0.01. (E) Luciferase assay detected RA signaling in Lsd1Prx1 and control periosteal cells treated with all-trans retinal for 12 hours. Results are representative of two independent experiments. Data are represented means ± SD. Unpaired t test was performed, **P < 0.01. (F) ChIP-qPCR analysis of LSD1 enrichment in the Aldh1a2 promoter regions in periosteal cells. n = 3 for each group, data are represented means ± SD. Unpaired t test was performed, ***P < 0.001. IgG, immunoglobulin G. (G) ChIP-qPCR analysis of H3K4me2 enrichment in the Aldh1a2 promoter regions in periosteal cells derived from 4-week-old Lsd1Prx1 and Lsd1fl/fl mice. n = 3 for each group; all data represent means ± SD. ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test was performed, ***P < 0.001.

Increased RA signaling inhibits SOX9 expression and fracture healing

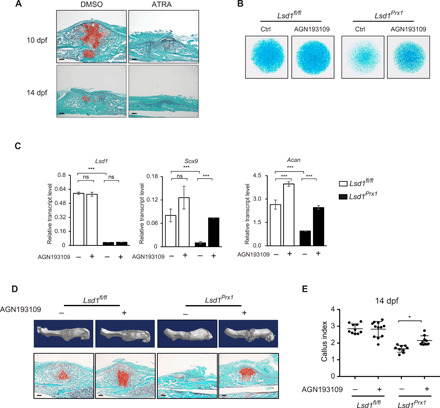

We found both RA and retinal could markedly inhibit chondrocyte differentiation and SOX9 protein level (fig. S7, A and B), which is consistent with previous studies showing that RA signaling suppressed chondrocyte differentiation (31). We therefore sought to investigate whether RA could impair cartilaginous callus formation during fracture healing. We performed standard femoral fracture on wild-type mice and randomly assigned them to treatment with either ATRA (15 mg/kg) or corn oil (control) daily starting at 4 dpf. At 14 dpf, we found that ATRA-treated mice failed to form a normal hard callus (fig. S7, C and D). Histological analysis showed that the cartilaginous callus was greatly impaired in the ATRA-treated group, which was analogous to that observed in Lsd1Prx1 mice (Fig. 5A). Inhibition of RA signaling through AGN193109, a selective RA receptor (RAR) antagonist, rescued the chondrocyte differentiation defects of Lsd1Prx1 cells (Fig. 5, B and C). To assess whether AGN193109 could improve the cartilage callus formation in Lsd1Prx1 mice, we treated Lsd1Prx1 mice and control mice with AGN193109 (4 mg/kg, daily) from 2 to 12 dpf. After administration of AGN193109, Lsd1Prx1 mice displayed improved cartilage callus formation at 14 dpf (Fig. 5, D and E). Overall, these data suggest that RA signaling suppresses fracture healing and contributes to the impaired fracture repair in Lsd1Prx1 mice.

Fig. 5. Increased RA signaling inhibits SOX9 expression and fracture healing.

(A) Safranin O staining was performed to detect cartilage formation at 10 and 14 dpf in ATRA-treated (15 mg/kg, daily) or vehicle control-treated mice. n = 3 mice per group. Scale bars, 100 μm. (B) Alcian blue staining of micromass culture using periosteal cells isolated from 4-week-old Lsd1Prx1 and control mice treated with AGN193109 or dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). n = 3. (C) RT-PCR analysis of the expression levels of Lsd1, Sox9, and Acan in AGN193109- or DMSO-treated micromass samples. Scale bars, 100 μm. ns, not significant, ***P < 0.001. (D) Reconstruction of μCT data reflected hard bony callus formation and Safranin O staining that showed cartilage formation of Lsd1Prx1 and control mice treated with AGN193109 or DMSO. (E) CI calculated from radiographic data showed the callus formation at 14 dpf of Lsd1Prx1 and control mice treated with AGN193109 or DMSO. N ≥ 9 for each group. Data are presented as means ± SD; unpaired t test, *P < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we provide the first genetic evidence that histone modification enzyme LSD1 is involved in bone repair. Loss of LSD1 in Prx1-Cre+ cells led to decreased SOX9 expression and impaired fracture cartilaginous callus formation, which was attributed to increased RA signaling.

SOX9 is a transcription factor that plays a central role in chondrocyte differentiation and cartilage maintenance, as it is indispensable for the commitment of mesenchymal stem cells toward the chondrocyte lineage (32). Heterozygous mutations of Sox9 cause campomelic dysplasia, a severe human skeletal malformation syndrome characterized with dwarfism, micrognathia, bent long bones, and other bone defects (33). Identifying factors that regulate SOX9 is of importance for better understanding and treating SOX9-related cartilage diseases. Our work reveals that loss of LSD1 reduced SOX9 levels, which led to both a campomelic dysplasia–like phenotype during bone development and impaired cartilaginous callus formation during bone regeneration. We showed that LSD1 sustains SOX9 expression during the process of fracture healing by repressing RA signaling via histone modification of Aldh1a2. However, it is possible that LSD1 could also regulate SOX9 independent of histone demethylation. In addition to the well-known role of LSD1 in histone modification, LSD1 also demethylates nonhistone proteins such as P53, signal transducers and activators of transcription 3 (STAT3), and hypoxia-inducible factor 1A (HIF1A) (34). STAT3 and HIF1A can be demethylated by LSD1 resulting in increased activity or stability, and several studies have shown STAT3 and HIF1A can bind to the Sox9 promoter and regulate its transcription directly (35–38). This suggests that LSD1 may also be able to regulate SOX9 through STAT3 or HIF1A.

RA signaling is crucial to embryonic development and postnatal maintenance of organ systems, including the skeletal system (39). Clinical data shows that both high- and low-serum retinol levels were associated with increased risk of fracture (40). Meanwhile, both increased RA signaling by RARγ agonist treatment or decreased RA signaling caused by vitamin A deficiency led to a delay in fracture repair, attributed to a decrease in bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signaling (41). Our data show that enhanced RA signaling could decrease SOX9 levels, which had a strong direct effect on chondrocyte differentiation and cartilage formation. Because of the important role of RA signaling, RA homeostasis is tightly regulated in mammals. There are various enzymes, receptors, and carrier proteins in charge of storage, transportation, metabolism, and clearance of RA signaling components. RALDH1A2 is a key enzyme responsible for synthesizing RA, and Raldh1a2 knockout mice displayed a lethal phenotype due to impaired RA synthesis, and this phenotype could be rescued by administration of ATRA (42). Our finding that LSD1 directly regulated expression of Raldh1a2 is a new approach to controlling RA signaling, and this regulation is essential for chondrocyte differentiation from progenitor cells.

Overall, our study highlights a critical role of LSD1 in endochondral ossification during fracture healing. Impaired fracture healing is more likely to happen in aging conditions or certain pathological states, such as diabetes mellitus, osteomyelitis, avascular necrosis, and hyperparathyroidism. Whether LSD1 has some functional loss in these conditions during fracture healing requires further study. Gaining further insight into the role of LSD1 in pathology-related impaired fracture repair will benefit clinical treatment of these diseases.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

Lsd1fl/fl mice–bearing loxP sites flanking exon 6 of the Lsd1 gene were provided by M. Rosenfeld. Prx1-Cre mice were purchased from the Jackson laboratory. Ai9 reporter mice were provided by Z. Qiu. All mice were bred and maintained under specific pathogen–free conditions in the institutional animal facility of the Shanghai Institute of Biochemistry and Cell Biology, Chinese Academy of Sciences. Age- and sex-matched littermates were used as control mice. Both genders were used in experiments.

ChIP assays

Primary periosteal cells were isolated from Lsd1Prx1 mice and control Lsd1fl/fl mice. Cells (1 × 106) were used for each immunoprecipitation. Briefly, cells were cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde at room temperature for 10 min. Glycine with a final concentration of 125 mM was added to quench the cross-linking. Cells were scraped, washed by phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) three times, and lysed with SDS buffer (1% SDS, 10 nM EDTA, and 50 mM tris). Samples were then sonicated to produce 0.2- to 0.7-kb DNA fragments. Indicated antibody (8 μg) was used for immunoprecipitation overnight at 4°C. Protein G beads were then added and incubated for 2 hours to isolate anitbody-bound chromatin. The ChIP DNA was purified with a PCR purification kit (Qiagen) and quantified by real-time PCR. The primers sequences for ChIP-qPCR are listed in table S1.

Isolation and culture of periosteal cells

Primary periosteal cells were isolated from the femurs of 4-week-old mice. After carefully removing the muscles and tendons, periosteum was scrapped under a dissecting microscope and then digested with collagenase II (1 mg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich) and dispase II (2 mg/ml; Roche) for 30 min at 37°C. Cells were passed through a 70-μm nylon mesh (BD Falcon), then pelleted at 1500 rpm for 5 min, suspended in α-minimal essential medium (Gibco) with 10% fetal bovine serum (Ausbian) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco), and cultured in the cell incubator at 37°C with 5% CO2.

Antibodies and reagents

Anti-LSD1 (ab17721) were obtained from Abcam. Anti-H3K4me1 (A2355), anti-H3K4me2 (A2356), and anti-H3K4me3 (A2357) were purchased from ABclonal Technology. Anti-tubulin antibody (SC-23948) for Western blot was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Anti-ALDH1A2 (ab75674) for immunostaining was from Abcam. Anti-SOX9 (AB5535) was purchased from Millipre/Merck. Anti-CD31 (AF3628) was from R&D Systems. All-trans retinol [HY-B1342, MedChemExpress (MCE)] was used at a concentration of 1 μM. All-trans RA (HY-14649, MCE) was used at a concentration of 100 nM. AGN193109 (HY-U00449) was purchased from MCE.

Vector information

pGL3-RARE-luciferase vector (no. 13458) was purchased from Addgene.

Histology and immunostaining

Tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 48 hours and incubated in 15% diethyl pyrocarbonate–EDTA (pH 7.8) for decalcification. Then, specimens were embedded in paraffin and sectioned at 5 μm. Immunohistochemistry was performed using a trichostatin A–biotin amplification system (PerkinElmer Life Sciences) according to the manufacturer’s instructions using antibody against SOX9. Frozen bone samples were thawed at room temperature for 10 min, rehydrated with PBS, and blocked for 1 hour with 10% horse serum and 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS, followed by primary antibodies incubation overnight at 4°C. Then, samples were washed three times with PBS and incubated by secondary antibodies for 1 hour followed by washing three times with PBS. The samples were mounted with fluoroshield mounting medium with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Abcam, ab104139). Images were acquired with an Olympus confocal microscope (FV1200) and Olympus fluorescence microscope (BX51). The following primary antibodies were used: SOX9 (1:200 dilution; Millipore, AB5535), ALDH1A2 [1:100 dilution; Abcam, ab75674; citrate unmasking (pH 6)], collagen type II (1:200 dilution; Abcam, ab34712), collagen type X (1:200 dilution; Abclonal, A6889), and platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule/CD31 (1:200 dilution; R&D Systems, AF3628).

Sample preparation for frozen section

Freshly extracted unfractured and fractured mouse samples were collected and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 36 hours at 4°C. Samples were decalcified with 15% EDTA for 14 days. After washing in PBS, samples were incubated in PBS/30% sucrose overnight at 4°C and embedded in optimum cutting temperature embedding medium. Samples were preserved at −80°C. Sections were performed by a Leica cryostat with a thickness of 10 cm.

Mice bone fracture model

Six-week-old male or female mice were used for the model. Mice were anesthetized using chloral hydrate. The patella was dislocated laterally to expose femoral condyles, and an intramedullary pin was inserted to stabilize the femur; the patella was then relocated. The fracture was made using a dentist’s microdrill at midpoint of femur. Muscles were reapproximated, and the skin was closed using a 6/0 nylon suture. Fracture repair was followed radiographically using an MX2 x-ray system (6 s at 932 kV) weekly.

μCT analysis

The mouse fractured femurs were skinned and fixed in 70% ethanol. Femurs were scanned using a Skyscan 1176 scanner (Bruker, Kartuizersweg, Belgium) with a spatial resolution of 8.96 μm. The x-ray energy is 70 kVp and 305 μA. Three-dimensional reconstruction of bone was performed using CTVox software.

Biomechanical testing

The mouse fractured femurs were skinned and fixed in 70% ethanol before testing. The specimens were fixed by silica gel at the two ends of the bone. Specimens were tested in torsion using electromechanical torsion testing machine (0.5 N.m torque cell; LAB ANS UHNZ001) at 30°/min. The torque data were plotted against the rotational deformation to determine the maximum torque.

ALDEFLUOR assay

The ALDEFLUOR Kit (STEMCELL Technologies, 01700) was used to measure the ALDH enzymatic activity in callus cells following the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, fracture callus tissues at 4.5 dpf were isolated and cut into small pieces with sterile scissors and then digested with collagenase II (1 mg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich) and dispase II (2 mg/ml; Roche) for 30 min at 37°t. Cells were passed through a 70-μm nylon mesh (BD Falcon) then pelleted at 1500 rpm for 5 min, and suspended in 1-ml ALDEFLUOR assay buffer. After addition of 5 μl of ALDH substrate and a brief mixing, 0.5 ml of the cell suspension was transferred to a new tube supplemented with 5 μl of DEAB (a specific ALDH inhibitor) as a negative control.

Both tubes were incubated for 40 min at 37°C. The cells were then washed twice with ALDEFLUOR buffer and stained with DAPI for dead cells before analyzing by BD LSR II flow cytometer.

Quantitation of ATRA in mouse serum

ATRA was quantified in serum as previously described (43). Briefly, 100 μl of serum and 1 μl of ATRA-d5 [50 μg/ml; internal standard, Toronto Research Chemicals (TRC)] were transferred to a 15-ml glass culture tube and extracted in 200 μl of acetonitrile (Sigma-Aldrich) and 2-μl formic acid (Sigma-Aldrich) and 10 ml of hexanes (Sigma-Aldrich). The hexane extracts was separated by centrifugation, dried under nitrogen flow, and reconstituted in 100 μl of acetonitrile for LC-MS/MS analysis. The whole process was performed on ice and under yellow light to avoid the degradation.

The concentration of ATRA from serum was measured using the AB Sciex 4000 QTRAP LC-MS/MS System equipped with atmospheric-pressure chemical ionization (APCI) in positive ion mode. Briefly, ATRA was separated with the 2.1 mm by 100 mm Supelcosil ABZ + PLUS column (3 μm; Sigma-Aldrich) with the following running solvents: A, H2O with 0.1% formic acid; B, acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid. Quantification is based on peak area ratio of ATRA to the ATRA-d5 and the ATRA-d5 concentration.

RNA sequencing

Six-week-old female Lsd1Prx1; Ai9 mice and Prx1 Lsd1fl/+; Ai9 littermate controls were applied for fracture surgery. Total RNA was isolated using TRIzol (Sigma-Aldrich) from sorted ai9+ cells from the bone callus of fractured femurs at 4.5 dpf. Complementary DNA (cDNA) library preparation and sequencing were performed according to Illumina’s standard protocol.

Real-time RT-PCR analysis

Total RNA was prepared using TRIzol (Sigma-Adrich) and was reverse-transcribed into cDNA with the PrimeScript RT Reagent Kit (TakaRa). Real-time qPCR was performed with the Bio-Rad CFX96 System. The sequences of oligonucleotides used for qPCR are listed in table S1.

In vivo AGN193109 treatment

Six-week-old female Lsd1Prx1 mice and Lsd1fl/fl littermate controls were applied for fracture surgery. Lsd1Prx1 mice were then divided into two groups separately. We injected these mice with either AGN193109 (2 mg/kg) or saline intraperitoneally every day from 2 to 12 dpf. At 14 dpf, we did histological analysis on these fractured bones to examine the formation of cartilage at the fracture site. We also did radiographic and μCT analysis of 14 dpf samples.

In vivo ATRA treatment

Six-week-old wild-type male mice were applied for fracture surgery. Mice were then divided into two groups separately. We injected these mice with either ATRA (15 mg/kg) or saline intraperitoneally every day from 4 dpf to the sample collection day. At 10 and 14 dpf, we did histological analysis on these fractured bones to examine the formation of cartilage at the fracture site. We also did radiographic and μCT analysis of 14 dpf samples.

Skeletal preparation and staining

Mice were eviscerated, and the skin was removed, and the resulting samples were transferred into acetone for 48 hours after overnight fixation in 95% ethanol. Skeletons were then stained in Alcian blue and Alizarin red solution as described previously (44). Specimens were kept in 1% KOH until tissue had completely cleared.

Statistics

All results are presented as the means ± SD. Comparisons between two groups were analyzed using two-tailed, unpaired Student’s t test. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukery’s post hoc test was used when the data involves multiple group comparisons.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the cell biology core facility and the animal core facility of Shanghai Institute of Biochemistry and Cell Biology for assistance. Funding: This work was supported by the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (grant number XDB19000000), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC; grant number 81725010), and the NSFC (grant number 81672119). All experiments were performed according to the protocol approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Institute of Biochemistry and Cell Biology, SIBS, and CAS. Author contributions: W.Z., J. Sun, and H.F. designed research. J. Sun, H.F., W.X., Y.H., and J. Suo performed research. N.Q. contributed to x-ray data collection. J. Sun, H.F., Y.S., and W.Z. analyzed data. J. Sun, H.F., A.R.Y., M.B.G., and W.Z. wrote the paper. Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. Additional data related to this paper may be requested from the authors.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/6/45/eaaz1410/DC1

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Gil J. A., DeFroda S. F., Sindhu K., Cruz A. I. Jr., Daniels A. H., Challenges of fracture management for adults with osteogenesis imperfecta. Orthopedics 40, e17–e22 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Piccioli A., Rossi B., Sacchetti F. M., Spinelli M. S., Di Martino A., Fractures in bone tumour prosthesis. Int. Orthop. 39, 1981–1987 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Einhorn T. A., Gerstenfeld L. C., Fracture healing: Mechanisms and interventions. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 11, 45–54 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hernandez R. K., Do T. P., Critchlow C. W., Dent R. E., Jick S. S., Patient-related risk factors for fracture-healing complications in the United Kingdom General Practice Research Database. Acta Orthop. 83, 653–660 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferguson C., Alpern E., Miclau T., Helms J. A., Does adult fracture repair recapitulate embryonic skeletal formation? Mech. Dev. 87, 57–66 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhou X., von der Mark K., Henry S., Norton W., Adams H., de Crombrugghe B., Chondrocytes transdifferentiate into osteoblasts in endochondral bone during development, postnatal growth and fracture healing in mice. PLOS Genet. 10, e1004820 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duchamp de Lageneste O., Julien A., Abou-Khalil R., Frangi G., Carvalho C., Cagnard N., Cordier C., Conway S. J., Colnot C., Periosteum contains skeletal stem cells with high bone regenerative potential controlled by periostin. Nat. Commun. 9, 773 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murao H., Yamamoto K., Matsuda S., Akiyama H., Periosteal cells are a major source of soft callus in bone fracture. J. Bone Miner. Metab. 31, 390–398 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ono N., Kronenberg H. M., Bone repair and stem cells. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 40, 103–107 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maes C., Kobayashi T., Selig M. K., Torrekens S., Roth S. I., Mackem S., Carmeliet G., Kronenberg H. M., Osteoblast precursors, but not mature osteoblasts, move into developing and fractured bones along with invading blood vessels. Dev. Cell 19, 329–344 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mizoguchi T., Pinho S., Ahmed J., Kunisaki Y., Hanoun M., Mendelson A., Ono N., Kronenberg H. M., Frenette P. S., Osterix marks distinct waves of primitive and definitive stromal progenitors during bone marrow development. Dev. Cell 29, 340–349 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shi Y., He G., Lee W. C., McKenzie J. A., Silva M. J., Long F., Gli1 identifies osteogenic progenitors for bone formation and fracture repair. Nat. Commun. 8, 2043 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhou B. O., Yue R., Murphy M. M., Peyer J. G., Morrison S. J., Leptin-receptor-expressing mesenchymal stromal cells represent the main source of bone formed by adult bone marrow. Cell Stem Cell 15, 154–168 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Debnath S., Yallowitz A. R., McCormick J., Lalani S., Zhang T., Xu R., Li N., Liu Y., Yang Y. S., Eiseman M., Shim J. H., Hameed M., Healey J. H., Bostrom M. P., Landau D. A., Greenblatt M. B., Discovery of a periosteal stem cell mediating intramembranous bone formation. Nature 562, 133–139 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matthews B. G., Grcevic D., Wang L., Hagiwara Y., Roguljic H., Joshi P., Shin D.-G., Adams D. J., Kalajzic I., Analysis of αSMA-labeled progenitor cell commitment identifies notch signaling as an important pathway in fracture healing. J. Bone Miner. Res. 29, 1283–1294 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mori Y., Adams D., Hagiwara Y., Yoshida R., Kamimura M., Itoi E., Rowe D. W., Identification of a progenitor cell population destined to form fracture fibrocartilage callus in Dickkopf-related protein 3–green fluorescent protein reporter mice. J. Bone Miner. Metab. 34, 606–614 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Colnot C., Skeletal cell fate decisions within periosteum and bone marrow during bone regeneration. J. Bone Miner. Res. 24, 274–282 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Soung D. Y., Talebian L., Matheny C. J., Guzzo R., Speck M. E., Lieberman J. R., Speck N. A., Drissi H., Runx1 dose-dependently regulates endochondral ossification during skeletal development and fracture healing. J. Bone Miner. Res. 27, 1585–1597 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang C. C., Inzana J. A., Mirando A. J., Ren Y., Liu Z., Shen J., O’Keefe R. J., Awad H. A., Hilton M. J., NOTCH signaling in skeletal progenitors is critical for fracture repair. J. Clin. Invest. 126, 1471–1481 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ortinau L. C., Wang H., Lei K., Deveza L., Jeong Y., Hara Y., Grafe I., Rosenfeld S. B., Lee D., Lee B., Scadden D. T., Park D., Identification of functionally distinct Mx1+αSMA+ periosteal skeletal stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 25, 784–796.e5 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shi Y., Lan F., Matson C., Mulligan P., Whetstine J. R., Cole P. A., Casero R. A., Shi Y., Histone demethylation mediated by the nuclear amine oxidase homolog LSD1. Cell 119, 941–953 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sun J., Ermann J., Niu N., Yan G., Yang Y., Shi Y., Zou W., Histone demethylase LSD1 regulates bone mass by controlling WNT7B and BMP2 signaling in osteoblasts. Bone Res. 6, 14 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Madisen L., Zwingman T. A., Sunkin S. M., Oh S. W., Zariwala H. A., Gu H., Ng L. L., Palmiter R. D., Hawrylycz M. J., Jones A. R., Lein E. S., Zeng H., A robust and high-throughput Cre reporting and characterization system for the whole mouse brain. Nat. Neurosci. 13, 133–140 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bi W. M., Huang W., Whitworth D. J., Deng J. M., Zhang Z., Behringer R. R., de Crombrugghe B., Haploinsufficiency of Sox9 results in defective cartilage primordia and premature skeletal mineralization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 6698–6703 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kohn A., Rutkowski T. P., Liu Z., Mirando A. J., Zuscik M. J., O’Keefe R. J., Hilton M. J., Notch signaling controls chondrocyte hypertrophy via indirect regulation of Sox9. Bone Res. 3, 15021 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kumar D., Lassar A. B., Fibroblast growth factor maintains chondrogenic potential of limb bud mesenchymal cells by modulating DNMT3A recruitment. Cell Rep. 8, 1419–1431 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sekiya I., Koopman P., Tsuji K., Mertin S., Harley V., Yamada Y., Shinomiya K., Niguji A., Noda M., Transcriptional suppression of Sox9 expression in chondrocytes by retinoic acid. J. Cell Biochem. 81, 71–78 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Woods A., Wang G., Beier F., RhoA/ROCK signaling regulates Sox9 expression and actin organization during chondrogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 11626–11634 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cunningham T. J., Duester G., Mechanisms of retinoic acid signalling and its roles in organ and limb development. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 16, 110–123 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Topletz A. R., Tripathy S., Foti R. S., Shimshoni J. A., Nelson W. L., Isoherranen N., Induction of CYP26A1 by metabolites of retinoic acid: evidence that CYP26A1 is an important enzyme in the elimination of active retinoids. Mol. Pharmacol. 87, 430–441 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shimono K., Tung W. E., Macolino C., Chi A. H. T., Didizian J. H., Mundy C., Chandraratna R. A., Mishina Y., Enomoto-Iwamoto M., Pacifici M., Iwamoto M., Potent inhibition of heterotopic ossification by nuclear retinoic acid receptor-γ agonists. Nat. Med. 17, 454–460 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lefebvre V., Dvir-Ginzberg M., SOX9 and the many facets of its regulation in the chondrocyte lineage. Connect. Tissue Res. 58, 2–14 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schafer A. J., Foster J. W., Kwok C., Weller P. A., Guioli S., Goodfellow P. N., Campomelic dysplasia with XY sex reversal: Diverse phenotypes resulting from mutations in a single Genea. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 785, 137–149 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Forneris F., Binda C., Battaglioli E., Mattevi A., LSD1: Oxidative chemistry for multifaceted functions in chromatin regulation. Trends Biochem. Sci. 33, 181–189 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Amarilio R., Viukov S. V., Sharir A., Eshkar-Oren I., Johnson R. S., Zelzer E., HIF1 regulation of Sox9 is necessary to maintain differentiation of hypoxic prechondrogenic cells during early skeletogenesis. Development 134, 3917–3928 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hall M. D., Murray C. A., Valdez M. J., Perantoni A. O., Mesoderm-specific Stat3 deletion affects expression of Sox9 yielding Sox9-dependent phenotypes. PLOS Genet. 13, e1006610 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee J. Y., Park J. H., Choi H. J., Won H. Y., Joo H. S., Shin D. H., Park M. K., Han B., Kim K. P., Lee T. J., Croce C. M., Kong G., LSD1 demethylates HIF1α to inhibit hydroxylation and ubiquitin-mediated degradation in tumor angiogenesis. Oncogene 36, 5512–5521 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang J. B., Huang J., Dasgupta M., Sears N., Miyagi M., Wang B., Chance M. R., Chen X., Du Y., Wang Y., An L., Wang Q., Lu T., Zhang X., Wang Z., Stark G. R., Reversible methylation of promoter-bound STAT3 by histone-modifying enzymes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 21499–21504 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Niederreither K., Dolle P., Retinoic acid in development: Towards an integrated view. Nat. Rev. Genet. 9, 541–553 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Michaëlsson K., Lithell H., Vessby B., Melhus H., Serum retinol levels and the risk of fracture. N. Engl. J. Med. 348, 287–294 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tanaka K., Tanaka S., Sakai A., Ninomiya T., Arai Y., Nakamura T., Deficiency of vitamin A delays bone healing process in association with reduced BMP2 expression after drill-hole injury in mice. Bone 47, 1006–1012 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mic F. A., Molotkov A., Benbrook D. M., Duester G., Retinoid activation of retinoic acid receptor but not retinoid X receptor is sufficient to rescue lethal defect in retinoic acid synthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 7135–7140 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kane M. A., Napoli J. L., Quantification of endogenous retinoids. Methods Mol. Biol. 652, 1–54 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Greenblatt M. B., Shim J. H., Zou W., Sitara D., Schweitzer M., Hu D., Lotinun S., Sano Y., Baron R., Park J. M., Arthur S., Xie M., Schneider M. D., Zhai B., Gygi S., Davis R., Glimcher L. H., The p38 MAPK pathway is essential for skeletogenesis and bone homeostasis in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 120, 2457–2473 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/6/45/eaaz1410/DC1