Positive river heat–sea ice feedback doubles the river heat effect on declining Arctic sea ice.

Abstract

Arctic river discharge increased over the last several decades, conveying heat and freshwater into the Arctic Ocean and likely affecting regional sea ice and the ocean heat budget. However, until now, there have been only limited assessments of riverine heat impacts. Here, we adopted a synthesis of a pan-Arctic sea ice–ocean model and a land surface model to quantify impacts of river heat on the Arctic sea ice and ocean heat budget. We show that river heat contributed up to 10% of the regional sea ice reduction over the Arctic shelves from 1980 to 2015. Particularly notable, this effect occurs as earlier sea ice breakup in late spring and early summer. The increasing ice-free area in the shelf seas results in a warmer ocean in summer, enhancing ocean–atmosphere energy exchange and atmospheric warming. Our findings suggest that a positive river heat–sea ice feedback nearly doubles the river heat effect.

INTRODUCTION

River discharge transports large volumes of relatively warm freshwater into the Arctic Ocean (1), affecting the heat budget and potentially enhancing sea ice decline. Observations show high riverine heat (Qrh) in spring and early summer when the shelf seas are still covered by ice (2). The entrained Qrh is difficult to measure, however, since it remains invisible to satellite observations and is largely decoupled from the atmosphere (3). Meanwhile, its effect becomes clearly visible in spring when Qrh triggers ice breakup in the vicinity of river mouths (4, 5). Subsequent warming of ocean surface waters in summer further delays sea ice formation in autumn (6), although the relationship between Qrh and autumn sea ice is less defined compared to the well-established strong impact of Qrh on spring sea ice retreat (3, 4). There are, however, reasons to believe that the impacts of Qrh are not confined to seasonal changes of sea ice in the shelf seas. Enhanced offshore sea ice retreat in spring caused by Qrh likely results in further increase of net solar radiation loading during summer, which is closely linked to seasonal heat cycling in the upper ocean and energy exchange with the atmosphere linked to climate (7, 8). However, more comprehensive information needed to quantify the various impacts of Qrh in the Arctic has been lacking.

There is now no alternative to numerical modeling for quantifying Qrh transport over the Arctic shelves and further offshore to the deep-sea areas and the associated impacts on Arctic sea ice variability. Most state-of-the-art climate models have incorporated riverine freshwater (volume) influxes to the Arctic Ocean (9–13). However, Qrh has been rarely included in these models. Recently, Qrh has been simulated in fully coupled climate models incorporating more sophisticated land surface modules, namely, CM2M and CM2G from the Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory. Another state-of-the-art model, Nucleus for European Modeling of the Ocean (NEMO), has an optional parameterization of Qrh in which river water temperature (Tw) was represented by sea surface temperature (Ts) observed at river mouths (14), although this parameterization does not realistically account for the seasonal change of Tw. Whitefield et al. (15) developed a new pan-Arctic climatological dataset of river discharge and Tw based on observed records from 30 Arctic rivers and used this dataset in regional sea ice–ocean model simulations, showing that riverine heat fluxes to the Arctic shelves reduced September sea ice extent by ~10% from 1979 to 2012. While these prior studies have made notable advances in clarifying the influence of river heat on Arctic ocean–sea ice–atmosphere dynamics, previous model studies have not deeply evaluated impacts of interannually variable Qrh. In this study, we combined a pan-Arctic coupled sea ice–ocean model [Center for Climate System Research Ocean Component Model (COCO), version 4.9] (16) with an Arctic land surface model [A coupled hydrological and biogeochemical model (CHANGE)] and distributed hydrological model (1, 17) to quantify the Qrh impact on decreasing Arctic sea ice within the six major Arctic shelf regions (Fig. 1C) in the recent decades (1980–2015). The coupled land–ocean–sea ice model framework provides capabilities for clarifying the influence of Qrh seasonal and interannual variability and longer-term warming trends on Arctic sea ice dynamics in the recent decades. The experimental design also represents a substantial advance toward more realistic simulation and attribution of Arctic sea ice variability, feedbacks, and underlying drivers.

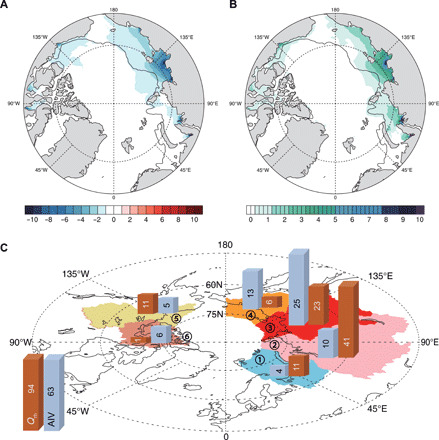

Fig. 1. Riverine heat release causes anomalous sea ice thickness and volume.

(A) The anomaly of annual mean sea ice thickness (centimeters) caused by riverine heat, Qrh from 1980 to 2015. (B) The proportion (%) of the ice thickness reduction shown in (A) relative to annual mean sea ice thickness. (C) The mean Qrh (×1018 J) produced by the six largest river drainages and the annual anomalous sea ice volume (AIV, cubic kilometer, positive indicates reduction) caused by Qrh from 1980 to 2015 for the six individual shelf regions. In (A) and (B), only values with a mean sea ice thickness anomaly exceeding 0.5 cm are shown. The colored areas in (C) represent the six targeted shelf regions in this study, including the major river drainage areas producing Qrh. The circled numbers in (C) represent ① Barents Sea, ② Kara Sea (Ob and Yenisey Rivers), ③ Laptev Sea (Lena River), ④ Eastern Siberian Sea (Kolyma River), ⑤ Beaufort Sea (Mackenzie River), and ⑥ Canadian Archipelago. Thin black contours in (A) and (B) show the 200-m isobath.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Spatiotemporal variability of riverine heat

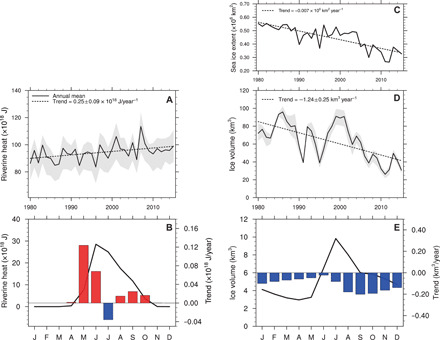

According to the CHANGE simulations, an average of 94.4 × 1018 J year−1 of Qrh was delivered to the Arctic river mouths from 1980 to 2015 (Fig. 1C), which is equivalent to an annual heat flux of 3.0 TW. This estimate is similar to the 3.2 TW estimate obtained by Whitefield et al. (15) based on observations from 30 Arctic rivers. Our analysis showed an increasing Qrh trend of 0.25 ± 0.09 × 1018 J year−1 during this period (Fig. 2A). This Qrh contribution to the Arctic Ocean energy budget is sizable, constituting about 6.8% of oceanic heat inputs from the Atlantic and Pacific oceans (18)—enough to melt 0.31 × 106 km2 of 1-m-thick ice. The Qrh is characterized by strong seasonal variability; whereby, approximately 65% of the annual Qrh input occurs from May to July (Fig. 2B) when the Arctic shelf is mostly covered by sea ice, thus warming the shelf waters (4). Independent observations of melting dates derived from the satellite record show a 10- to 30-day delay in seasonal retreat of the ice cover over the shelf seas relative to thawing of nearby Arctic land areas from 1980 to 2015 (fig. S1). The spring thaw signal over Arctic land areas coincides with seasonal snowmelt and the freshwater runoff pulse to Arctic rivers (19, 20); the earlier terrestrial thaw onset indicates a Qrh contribution to ocean warming under the ice cover, whereby Qrh is an important heat source for preconditioning sea ice melt in spring and early summer.

Fig. 2. Seasonal and interannual variability of riverine heat and anomalous sea ice volume.

Impact of riverine heat Qrh on Arctic sea ice decay in the six Arctic shelf regions (see Fig. 1c for their definition). (A) Time series of Qrh discharged into the Arctic Ocean, (B) seasonal cycle of Qrh (line); 1980–2015 trends are shown by red and blue bars, (C) satellite summer (15–31 July) sea ice extent, (D) AIV interannual variation, and (E) seasonal cycle with trends (bars) of ice volume reduction caused by Qrh over the six Arctic regions. Gray shading in (A) and (D) denotes uncertainties indicated from model sensitivity experiments (Supplementary Materials). Linear trends in (A), (C), and (D) are shown by dotted lines.

Decay of sea ice under impact of riverine heat

The simulated annual sea ice thickness decay caused by Qrh indicates that the largest sea ice reduction impact occurs around the mouths of the largest Arctic rivers (Fig. 1, A and B). An overall maximum annual reduction in the estimated regional mean sea ice thickness of more than 10% (~10 cm) occurred in near-shore part of the Laptev Sea and was associated with a relatively large Qrh input from local rivers (mostly the Lena River). In this region, the impact of Qrh on sea ice can be traced as far as 80°N during summer, demonstrating that Qrh eventually causes sea ice decay over the outer shelf rather than being only confined to a narrow coastal zone (Fig. 1, A and B).

Our analysis shows that from 1980 to 2015, Qrh caused a sea ice extent retreat of 0.05 × 106 km2 over the six Arctic shelf regions in September (fig. S2). Anomalous ice volume (AIV), representing the annual sea ice reduction driven by Qrh over the Arctic shelves (Fig. 1C), averaged 63.3 km3 from 1980 to 2015 (Fig. 2D). The linear AIV trend suggests a sea ice volume decay rate of 1.24 ± 0.25 km3 year−1 (P < 0.01) from 1980 to 2015 (Fig. 2D). Seasonally, the maximum AIV is found in July (Fig. 2E). The AIV shows strong interannual variability ranging from 25 to 100 km3 and large regional differences (Fig. 1C). The largest AIV of 25 km3 is found in the Laptev Sea, which has the highest Qrh among the six shelf regions (Fig. 1C) (compared, for example, with AIV = 5 km3 in the Beaufort Sea).

However, the relationship between AIV and Qrh is complex; for instance, AIV in the East Siberian Sea, despite relatively low Qrh, is larger than the AIV in the Kara Sea (Fig. 1C). This provides important evidence indicating why AIV was higher in the 1980s and 1990s compared with the more recent decades (Fig. 2D), despite having lower Qrh (Fig. 2A). Consolidated sea ice conditions near riverine heat sources (river mouths) in the 1980s and 1990s (Fig. 2C) led to an enhanced Qrh impact on sea ice through intensive lateral and bottom sea ice melt (3, 6), while earlier ice retreat and more extensive ice-free area in recent decades (Fig. 2C) decreased the direct contact of Qrh with sea ice during the melting season, hence lowering AIV (Fig. 2D). Significant correlation (r = 0.60, P < 0.01) between simulated AIV and observed sea ice extent in early summer supports this finding (Fig. 2C). However, according to our model simulations, the increasing Qrh trend (Fig. 2A) and decrease in heat expenditures on sea ice melt in the vicinity of river mouths enhanced ocean warming and additional heat released to the atmosphere. The consequences of these changes are discussed in the following sections.

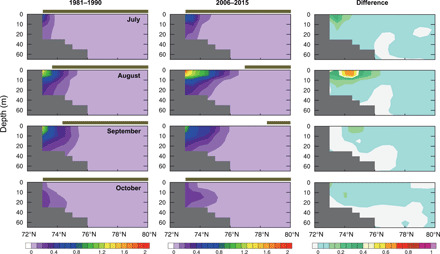

Warming of shelf waters caused by riverine heat

The anomalous ocean warming resulting from the increasing impact of Qrh averaged over 1980–2015 was estimated as Qow = 48.2 × 1018 J year−1. This warming spreads from the river mouths toward the outer shelf and also vertically, occupying the entire water column, with greater spread in the recent decades relative to the 1980s (Fig. 3). For example, the anomalous warming of the ocean surface layer reached 76°N in August in the Laptev Sea, where the thin (~5 m) surface layer showed anomalous warming (+1.5°C) from 2006 to 2015 (Fig. 3). Whitefield et al. (15) simulated a ~150-km spread of warm surface riverine water into the Beaufort Sea, which was associated with intensive mixing with deeper water layers at the shelf break. Our analysis shows a similar lateral Qrh spread of up to ~200-km offshore from the Mackenzie River outlet (Fig. 1B). The associated warming resulted in earlier breakup of sea ice by ~5 to 14 days over the coastal shelf and by ~3 days over the outer shelf for the 2006–2015 period relative to 1981–1990 (fig. S3). Both satellite records (fig. S1) and model simulations (fig. S3) also show a widespread lengthening of the ice-free season from 1981–1990 to 2006–2015, consistent with the earlier ice breakup and later freezing. The anomalous warming of the water column toward the outer shelf and bottom layer persists until September, as shown for the 2006–2015 period (Fig. 3), although the impact of Qrh on sea ice reduction in the outer shelves is not as large (Fig. 1, A and B) because the sea ice has already retreated further northward (Fig. 3). Further details of the heat contributed to ocean warming are discussed in the next section.

Fig. 3. Riverine heat increases oceanic temperatures over the Arctic shelves.

Latitude-depth sections of monthly anomalous ocean temperatures (°C) caused by Qrh along the 127°E section of the Laptev Sea averaged for periods (left) 1981–1990, (middle) 2006–2015, and (right) their difference (positive values denote recent warming). The upper horizontal bars in each panel indicate the maximum sea ice extent in individual months.

Ocean–sea ice–atmosphere heat balance change under riverine heat impacts

Our results provide compelling evidence that Qrh contributes to sea ice decay (Fig. 2D) and ocean warming (Qow; Fig. 3) over the six Arctic shelf regions (Fig. 1C). However, we also found that the sea ice retreat triggered feedbacks resulting from the sensitivity of the Arctic ocean–sea ice–atmosphere system to the state of the sea ice cover. A representative example is the ice-albedo feedback. By comparing the two numerical experiments, we found that sea ice decay and associated changes in surface albedo (21, 22) resulted in anomalous absorption of additional shortwave radiation (Qsw), which also led to further ocean warming and sea ice melt. In addition, sea ice retreat prompted the release of ocean heat into the atmosphere (Qao) through ice-free areas via contributions of upward longwave radiation and sensible and latent heat fluxes. Furthermore, we quantify the consequences of this increasing Qrh influx. Since the outer boundaries of the shelf regions are far away from the area where impact of Qrh is significant, heat losses through lateral exchanges between the shelves and deeper ocean areas were assumed to be negligible.

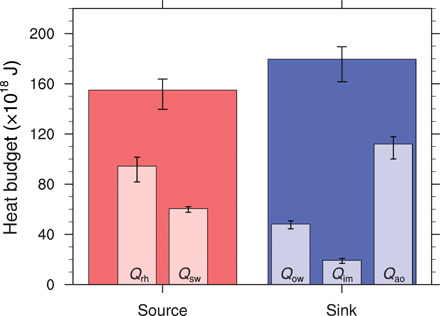

The ocean–sea ice–atmosphere system heat balance, including sources (Qrh + Qsw) and sinks (Qim + Qow + Qao) induced by riverine heat influx, averaged for 1980–2015 in the six Arctic shelf regions (Fig. 1C) is summarized in Fig. 4. Here, the ice-albedo feedback triggered by sea ice retreat resulted in 60.6 × 1018 J year−1 of radiative heat (Qsw) pumped into the system in addition to the 94.4 × 1018 J year−1 of Qrh delivered by warm riverine waters. Qsw represents the difference in net solar radiation between the two model experiments over the six Arctic shelf regions. Together, Qrh + Qsw represent total system sources in annual heating of 155.0 × 1018 J year−1—an astonishing 64% increase in net energy inputs due to the positive ice-albedo feedback.

Fig. 4. Heat balance change over Arctic shelf regions caused by influx of riverine heat.

Mean annual energy budget, including heat sources and sinks over the six Arctic shelf regions (Fig. 1). The heat sources are constituted by influx of riverine heat (Qrh) and additional absorption of solar radiation at the ocean surface caused by the sea ice–albedo feedback (Qsw). The heat sinks are formed by ocean warming (Qow), sea ice melting (Qim), and heat release from ocean to atmosphere (Qao). All values are averaged for the 1980–2015 period. The vertical lines at the top of the bars represent uncertainties of the estimates, defined by the three sensitivity experiments (Supplementary Materials).

The ocean–sea ice–atmosphere system heat sources were balanced by several sinks, including heat sinks to sea ice melt (Qim) estimated as Lf ∙ ρi ∙ A ∙ hi, where Lf is the latent heat of fusion (333.7 × 103 J kg−1), ρi is the ice density (917 kg m−3), A is the ice area (5.18 × 1012 m2), and hi is the melted ice thickness (meters). The resulting Qim estimate of 19.4 × 1018 J year−1 constituted 12% of Qrh + Qsw (Fig. 4). Most notable, the effect of the Qim heat sink occurred in spring and early summer, accounting for 9% of Qrh during May and August (Fig. 2E). The sea ice reduction by Qrh in winter (Fig. 2E) represents an amplified impact of summer ocean warming across the season (6) and is corroborated by observations showing a thinning shelf ice thickness trend in winter (23).

The anomalous heat sink for ocean warming (Qow) was estimated as 48.2 × 1018 J year−1 (Fig. 4) for the upper 100-m ocean layer (or surface to bottom layer, whichever is shallower) averaged over the six Arctic shelf regions, with an increasing Qow heat sink trend of 0.16 ± 0.09 × 1018 J year−1 from 1980 to 2015 (fig. S4A). The maximum Qow occurred in late summer (i.e., August or September; fig. S5B), which is a seasonally delayed manifestation of the increased ice melt in spring and early summer due to the peak of Qrh. In addition, the ocean warming caused a ~4-day delay of freezing during sea ice formation around large river mouths (fig. S3). The later freezing and earlier breakup trend yielded a longer open water period of up to 15 days in the inner parts of the shelf seas (fig. S3).

Most of the heat stored in the upper ocean in summer is lost to the atmosphere during autumn and winter by the upward propagation of longwave radiation and sensible/latent heat fluxes (fig. S5A). Annual ocean-to-atmosphere heat fluxes contributed 112.0 × 1018 J (0.68 W m−2), or 62%, to the overall heat sinks, thus constituting the largest of the energy sink components. The anomalous heat release to the atmosphere was strongest in late summer and autumn due to ocean surface warming (fig. S5). The three ocean–atmosphere heat flux components (net upward longwave radiation, sensible, and latent heat) contributed almost equally to the ocean heat sink (fig. S4B). Qao showed a significant increasing trend of 0.70 ± 0.18 × 1018 J year−1 from 1980 to 2015, which is well expressed by the three Qao constituents and dominated by increasing latent and sensible heat fluxes in the recent decade (fig. S4B). Our simulations captured the effects of the ice-albedo feedback via reduction of sea ice cover and the ocean temperature increase caused by Qrh, resulting in enhanced ocean–atmosphere energy transfer. Thus, our simulations provide a conservative estimate of atmospheric warming caused by Qrh and associated ocean warming.

Average warming of the 300-m atmospheric surface layer (24) in summer (JJAS) over the six Arctic shelf regions from the anomalous Qao increase was estimated to be 0.34 K (Supplementary Materials), contributing 0.003 K per year to the increasing air temperature trend from 1980 to 2015 (fig. S6). This regional air temperature increase constitutes a sizable part (~5%) of the overall Arctic surface air temperature warming trend of 0.064°C year−1 documented from maritime meteorological stations from 1979 to 2008 (25). The temperature increase further amplifies the Qrh effects on sea ice retreat and ocean warming, although these secondary effects were not addressed by our study.

The model estimated components (Qim + Qow + Qao) indicate a combined annual heat sink of approximately 179.5 × 1018 J from the influx of riverine heat into the Arctic shelf regions (Fig. 4). The apparent imbalance between annual heat sources and sinks of ~24.6 × 1018 J (expressed as a difference between sources and sinks in Fig. 4) characterizes an uncertainty of the estimated heat balance in the system. We note, however, that this imbalance is well within the range of model uncertainty due to the formulated forcing (i.e., indicated by vertical uncertainty lines in Fig. 4). Split evenly between energy sources and sinks, this uncertainty represents only ~8% of the total amount of heat sources or sinks annually by the system. This uncertainty can be explained by nonstationarities in the heat budget of the system, which are difficult to distinguish. For example, the residence time of riverine water and heat in the deeper water column may exceed 1 year in the shelf seas (26), resulting in overestimated annual Qow. Additional information about uncertainties in our estimates of the heat balance components is provided by the sensitivity experiments derived from three different atmospheric forcing datasets and represented by the uncertainty lines in Fig. 4. For example, the Qrh uncertainty of 19.7 × 1018 J year−1 (table S1) is mainly driven by the difference in precipitation between the three forcing datasets. Overall, these uncertainties do not preclude a meaningful analysis of the heat balance in the ocean–sea ice–atmosphere system (Fig. 4).

Our results indicate that riverine heat influx from the six major river drainage systems is having an important effect on the state of Arctic sea ice and, more generally, the ocean–sea ice–atmosphere system. Qrh enforced shelf sea ice decay in the melt season is triggering additional ocean absorption of shortwave radiation associated with the ice-albedo feedback. Increasing riverine heat influxes in the recent decade have warmed extensive areas of the Arctic shelves, promoting stronger ocean–atmosphere heat exchanges and thinner winter sea ice relative to the 1980s (Fig. 5).

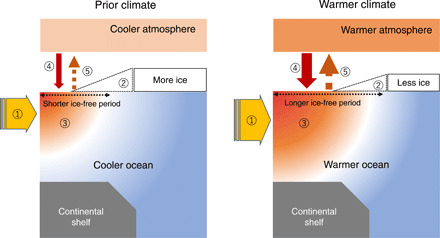

Fig. 5. Schematic showing changes in the Arctic atmosphere–sea ice–ocean system caused by riverine heat.

Anomalous riverine heat Qrh influx ① results in ② sea-ice reduction including loss of ice area, thickness, and longer ice-free periods, ③ ocean warming, ④ positive feedback caused by additional sea ice retreat and enhanced absorption of atmospheric heat, and ⑤ additional atmospheric warming caused by anomalous release of ocean heat into the atmosphere. The thicker vertical and horizontal arrows indicate larger heat fluxes or inflows.

The important role of riverine heat inputs on the Arctic ocean–sea ice–atmosphere system revealed by this study is lacking in the current generation of Earth system models. Thus, model improvements to better represent Qrh are needed to provide more realistic projections of future Arctic climate system trajectories. A considerable area of the Siberian shelf is underlain by submarine permafrost vulnerable to thawing. Increasing trends in Qrh may facilitate additional thawing of bottom permafrost and the release of greenhouse gases (27, 28) that further amplify Arctic warming. The warming ocean likely affects the shelf ecosystem that preserves large amounts of organic matter discharged from terrestrial rivers (29). Increasing ocean temperatures over the broad Arctic shelves may result in enhanced decomposition of benthic organic matter through enhanced bacterial activity and the microbial loop (30), consequently altering nutrient cycling and affecting food availability associated with changes in sea ice, stratification, and vertical mixing (31). Thus, implications of increasing Qrh influx in the Arctic may be far reaching, contributing to and potentially triggering multidisciplinary changes in the Arctic climate system.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We used the COCO-CHANGE model framework to assess impacts of Qrh on the Arctic sea ice variability. The COCO model, with 25-km horizontal resolution and 28 hybrid σ-z vertical levels, covers the pan-Arctic region from the Bering Strait to 45°N latitude in the Atlantic side. The atmospheric forcing components are constructed from the Climate Forecast System Reanalysis (32). The CHANGE model includes two modules. The first module represents land surface processes simulating explicit water and energy fluxes and vegetation dynamics in the atmosphere-soil-vegetation system. The second module includes a river discharge scheme adopting a storage-based distributed water routing algorithm with 0.5° (latitude/longitude) resolution (1, 17). Discharge and river water temperatures, simulated using the CHANGE model forced by three different meteorological datasets (Supplementary Materials), were used as riverine freshwater and heat fluxes in the COCO model experiments, which makes it possible to quantify the sensitivity of sea ice to the associated fluxes. Both COCO and CHANGE have been extensively used to simulate changes in sea ice–ocean processes associated with the Arctic sea-ice retreat (12) and long-term changes in river discharge and water temperatures from the pan-Arctic river system (1, 17), respectively.

Two sets of model experiments using the COCO-CHANGE framework were performed. The first (control) experiment used river discharge without consideration of riverine heat: Riverine heat flux referenced to Ts at each river mouth was kept to zero. In other words, Tw is assumed to be the same as the simulated Ts at each model time step so that the simulated ocean temperature is not changed directly by river discharge. This experimental setting is typical for the traditional model design [e.g., (9–13)]. The second experiment used the same atmospheric forcing and model configuration as the control, except that the COCO model used variable Tw derived from CHANGE [i.e., the riverine heat flux defined by ρwCwv(Tw – Ts) is positive in most periods, ρw is the water density (kg m−3), Cw = 4187 J kg−1 K−1 is the specific heat of water, and v is the volume flux (m3 s−1)]. The second experimental design is advanced in that the model realistically represents seasonal and interannual changes of Qrh and the associated impacts on the Arctic sea ice and heat budget compared with previous modeling efforts that used more simplistic parameterizations (14) and climatological data (15). We note that this approach is valid only when the mass transport in a basin with open boundaries is balanced so that the heat fluxes have unambiguous physical interpretation (33). However, we used this approach in our study as it is a standard one for modeling simulations. Differences between the two experiments were used to quantify the effect of the Qrh -induced heat flux anomaly on the state of the Arctic ocean–sea ice–atmosphere system in the defined six Arctic shelf regions (Fig. 1C). Full descriptions of the model approach are given in the Supplementary Materials.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported chiefly by the Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research of Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) (KAKENHI 26340018, 17H01870, and 19H05668); the Arctic Challenge for Sustainability II (ArCS II; JPMXD1300000000, JPMXD1420318865) project funded by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT), Japan; NASA grants NNH18ZDA001N-TE, 80NSSC19K0649, 80NSSC18K0980, and NNX15AT74A; NSF grants AON-1203473, AON-1724523, AON-1947162, and 1708427; DOE grant DE-SC0020640; the Norwegian Nansen Legacy program (project no. 276730); and CarbonBridge program (project no. 226415) both funded by the Research Council of Norway (RCN). We thank J. Walsh for comments on the manuscript and T. Yamazaki for comments on data analysis. Author contributions: H.P. developed the ideas, wrote most of this paper with I.P., and drew most of the figures. All authors participated in data processing and preliminary analysis. H.P. and E.W. coordinated the model experiments and analyzed the simulation results. Y.K., J.S.K., and K.O. analyzed satellite data. The insight into riverine heat impacts on sea ice was provided by X.Z. and D.Y. The riverine heat related heat budget, figures, and insight were provided by I.P. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript. Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. Data simulated by CHANGE and COCO are available from the sites (http://doi.org/10.17592/001.2020072701 and http://doi.org/10.17592/001.2020090101). Additional data related to this paper may be requested from the authors.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/6/45/eabc4699/DC1

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Park H., Yoshikawa Y., Yang D., Oshima K., Warming water in Arctic terrestrial rivers under climate change. J. Hydrometeorol. 18, 1983–1995 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lammers R. B., Pundsack J. W., Shiklomanov A. I., Variability in river temperature, discharge, and energy flux from the Russian pan-Arctic landmass. J. Geophys. Res. 112, G04S59 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Janout M., Hölemann J., Juhls B., Krumpen T., Rabe B., Bauch D., Wegner C., Kassens H., Timokhov L., Episodic warming of near-bottom waters under the Arctic sea ice on the central Laptev Sea shelf. Geophys. Res. Lett. 43, 264–272 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dean K. G., Stringer W. J., Ahlnas K., Searcy C., Weingartner T., The influence of river discharge on the thawing of sea ice, Mackenzie River Delta: Albedo and temperature analyses. Polar Res. 13, 83–94 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nghiem S. V., Hall D. K., Rigor I. G., Li P., Neumann G., Effects of Mackenzie River discharge and bathymetry on sea ice in the Beaufort Sea. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 873–879 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carmack E., Polyakov I., Padman L., Fer I., Hunke E., Hutchings J., Jackson J., Kelley D., Kwok R., Layton C., Melling H., Perovich D., Persson O., Ruddick B., Timmermans M.-L., Toole J., Ross T., Vavrus S., Winsor P., Toward quantifying the increasing role of oceanic heat in sea ice loss in the new Arctic. Bullet. Amer. Meteor. Soc. 96, 2079–2105 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kattsov V. M., Walsh J. E., Twentieth-century trends of Arctic precipitation from observational data and a climate model simulation. J. Climate 13, 1362–1370 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Serreze M. C., Barrett A. P., Stroeve J. C., Kindig D. N., Holland M. M., The emergence of surface-based Arctic amplification. Cryosphere 3, 11–19 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weatherly J. W., Walsh J. E., The effects of precipitation and river runoff in a coupled ice-ocean model of the Arctic. Climate Dynam. 12, 785–798 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Delworth T. L., Broccoli A. J., Rosati A., Stouffer R. J., Balaji V., Beesley J. A., Cooke W. F., Dixon K. W., Dunne J., Dunne K. A., Durachta J. W., Findell K. L., Ginoux P., Gnanadesikan A., Gordon C. T., Griffies S. M., Gudgel R., Harrison M. J., Held I. M., Hemler R. S., Horowitz L. W., Klein S. A., Knutson T. R., Kushner P. J., Langenhorst A. R., Lee H.-C., Lin S.-J., Lu J., Malyshev S. L., Milly P. C. D., Ramaswamy V., Russell J., Schwarzkopf M. D., Shevliakova E., Sirutis J. J., Spelman M. J., Stern W. F., Winton M., Wittenberg A. T., Wyman B., Zeng F., Zhang R., GFDL’s CM2 global coupled climate models. Part I: Formulation and simulation characteristics. J. Climate 19, 643–674 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nummelin A., Ilicak M., Li C., Smedsrud L. H., Consequences of future increased Arctic runoff on Arctic Ocean stratification, circulation, and sea ice cover. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 121, 617–637 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Watanabe E., Jin M., Hayashida H., Zhang J., Steiner N., Multi-model intercomparison of the Pan-Arctic ice-algal productivity on seasonal, interannual, and decadal timescales. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 124, 9053–9084 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang X., Zhang J., Heat and freshwater budgets and their pathways in the Arctic Mediterranean in a coupled Arctic Ocean/Sea-ice model. J. Oceanogr. 57, 207–234 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 14.G. Madec; the NEMO team, NEMO ocean engine, in Note du Pole de Modelisation [Institut Pierre-Simon Laplace (IPSL), France, 2016].

- 15.Whitefield J., Winson P., McClelland J., Menemenlis D., A new river discharge and river temperature climatology data set for the pan-Arctic region. Ocean Model. 88, 1–15 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 16.H. Hasumi, CCSR Ocean Component Model (COCO) version 4.0, in Center for Climate System Research Report (University of Tokyo, 2006), vol. 25, 103 pp. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Park H., Yoshikawa Y., Oshima K., Kim Y., Ngo-Duc T., Kimball J. S., Yang D., Quantification of warming climate-induced changes in terrestrial Arctic river ice thickness and phenology. J. Climate 29, 1733–1754 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Woodgate R. A., Weingartner T. J., Lindsay R., Observed increases in Bering Strait oceanic fluxes from the Pacific to the Arctic from 2001 to 2011 and their impacts on the Arctic Ocean water column. Geophys. Res. Lett. 39, L24603 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rawlins M. A., McDonald K. C., Frolking S., Lammers R. B., Fahnestock M., Kimball J. S., Vörösmarty C. J., Remote sensing of snow thaw at the pan-Arctic scale using the SeaWinds scatterometer. J. Hydrol. 312, 294–311 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim Y., Kimball J. S., Glassy J., Du J., An extended global Earth system data record on daily landscape freeze-thaw status determined from satellite passive microwave remote sensing. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 9, 133–147 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Curry J. A., Schramm J. L., Enert E. E., Sea ice-albedo climate feedback mechanism. J. Climate 8, 240–247 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perovich D. K., Richter-Menge J. A., Jones K. F., Light B., Elder B. C., Polashenski C., Laroche D., Markus T., Lindsay R., Arctic sea-ice melt in 2008 and the role of solar heating. Ann. Glaciol. 52, 355–359 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Polyakov I. V., Pnyushkov A. V., Alkire M. B., Ashik I. M., Baumann T. M., Carmack E. C., Goszczko I., Guthrie J., Ivanov V. V., Kanzow T., Krishfield R., Kwok R., Sundfjord A., Morison J., Rember R., Yulin A., Greater role for Atlantic inflows on sea-ice loss in the Eurasian Basin of the Arctic Ocean. Science 356, 285–291 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brooks I. M., Tjernstrom M., Persson P. O. G., Shupe M. D., Atkinson R. A., Canut G., Birch C. E., Mauritsen T., Sedlar J., Brookes B. J., The turbulent structure of the Arctic summer boundary layer during the Arctic summer cloud-ocean study. J. Geophys. Res. 122, 9685–9704 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bekryaev R. V., Polyakov I. V., Alexeev V. A., Role of polar amplification in long-term surface air temperature variations and modern Arctic warming. J. Climate 23, 3888–3906 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schlosser P., Bauch D., Fairbanks R., Bönisch G., Arctic river-runoff: Mean residence time on the shelves and in the halocline. Deep Sea Res. Part I 41, 1053–1068 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nicolsky D. J., Shakhova N., Modeling sub-sea permafrost in the East Siberian Arctic shelf: The Laptev Sea region. J. Geophys. Res. 117, F03028 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shakhova N., Semiletov I., Salyuk A., Yusupov V., Kosmach D., Gustafsson Ö., Extensive methane venting to the atmosphere from the sediments of the East Siberian Arctic shelf. Science 327, 1246–1250 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fichot C. G., Kaiser K., Hooker S. B., Amon R. M. W., Babin M., Bélanger S., Walker S. A., Benner R., Pan-Arctic distributions of continental runoff in the Arctic Ocean. Sci. Rep. 3, 1053 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kirchman D. L., Morán X. A. G., Ducklow H., Microbial growth in the polar oceans–role of temperature and potential impact of climate change. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 7, 451–459 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Piepenburg D., Recent research on Arctic benthos: Common notions need to be revised. Polar Biol. 28, 733–755 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saha S., Moorthi S., Pan H.-L., Wu X., Wang J., Nadiga S., Tripp P., Kistler R., Woollen J., Behringer D., Liu H., Stokes D., Grumbine R., Gayno G., Wang J., Hou Y. T., Chuang H.-Y., Juang H.-M. H., Sela J., Iredell M., Treadon R., Kleist D., van Delst P., Keyser D., Derber J., Ek M., Meng J., Wei H., Yang R., Lord S., van den Dool H., Kumar A., Wang W., Long C., Chelliah M., Xue Y., Huang B., Schemm J.-K., Ebisuzaki W., Lin R., Xie P., Chen M., Zhou S., Higgins W., Zou C.-Z., Liu Q., Chen Y., Han Y., Cucurull L., Reynolds R. W., Rutledge G., Goldberg M., The NCEP climate forecast system reanalysis. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 91, 1015–1058 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bacon S., Aksenov Y., Fawcett S., Madec G., Arctic mass, freshwater and heat fluxes: methods and modelled seasonal variability. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A 373, 20140169 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bitz C. M., Holland M. M., Weaver A. J., Eby M., Simulating the ice-thickness distribution in a coupled climate model. J. Geophys. Res. 106, 2441–2463 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bitz C. M., Lipscomb W. H., An energy-conserving thermodynamic model of sea ice. J. Geophys. Res. 104, 15669–15677 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lipscomb W. H., Remapping the thickness distribution in sea ice models. J. Geophys. Res. 106, 13989–14000 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 37.B. P. Leonard, M. K. MacVean, A. P. Lock, The flux-integral method for multi-dimensional convection and diffusion, in NASA Tech. Memo (NASA, 1994). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Noh Y., Kim H. J., Simulations of temperature and turbulence structure of the oceanic boundary layer with the improved near-surface process. J. Geophys. Res. 104, 15621–15634 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Steele M., Morley R., Ermold W., PHC: A global ocean hydrography with a high-quality Arctic Ocean. J. Climate 14, 2079–2087 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Woodgate R. A., Aagaard K., Weingartner T. J., Monthly temperature, salinity, and transport variability of the Bering Strait through flow. Geophys. Res. Lett. 32, L04601 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Olonscheck D., Mauritsen T., Notz D., Arctic sea-ice variability is primarily driven by atmospheric temperature fluctuations. Nat. Geosci. 12, 430–434 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Y. Kim, J. S. Kimball, J. Glassy, K. C. McDonald, MEaSUREs Global Record of Daily Landscape Freeze/Thaw Status, Version 4. Boulder, Colorado USA (NASA National Snow and Ice Data Center Distributed Active Archive Center, 2017); 10.5067/MEASURES/CRYOSPHERE/nsidc-0477.004. [DOI]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/6/45/eabc4699/DC1