Abstract

The purpose of our analysis was to determine if older adults show sleep inertia effects on performance at scheduled wake time, and whether these effects depend on circadian phase or sleep stage at awakening. Using the Digit Symbol Substitution Test, effects of sleep inertia on performance were assessed over the first 30 minutes after wake time on baseline days and when sleep was scheduled at different circadian phases. Mixed model analyses revealed that performance improved as time awake increased; that beginning levels of performance were poorest when wake time was scheduled to occur during the biological night; and that effects of sleep inertia on performance during the biological night were greater when awaking from non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep than from REM sleep. Based on our current understanding of sleep inertia effects in young subjects, and previous reports that older subjects awaken at an earlier circadian phase and are more likely to have their final awakening from NREM sleep than younger adults, our findings suggest older adults may be more vulnerable to sleep inertia effects than young adults.

Keywords: sleep inertia, performance, aging, biological rhythm, REM

Sleep inertia is a period of time immediately upon awakening during which alertness and performance are impaired, such that normal waking levels are not yet met (Balkin & Badia, 1988; Lubin, Hord, Tracy, & Johnson, 1976). It has been reported that both subjective alertness and cognitive performance are significantly impaired upon awakening even in subjects who are not sleep deprived and who are awakened at their habitual wake time (Achermann, Werth, Dijk, & Borbély, 1995; Jewett et al., 1999). Previous investigations have reported varying durations of sleep inertia effects, from 1 minute (Webb & Agnew, 1964) to two hours after awakening (Jewett et al., 1999). Based on prior studies of sleep inertia, it appears that the sleep-to-wake transition cannot be characterized as an immediate change from one state to another, but instead is a process that takes some time to complete (Ferrara & De Gennaro, 2000).

A variety of experimental paradigms have been used to study sleep inertia. One approach has been the use of abrupt awakenings by auditory stimuli or research staff in an attempt to mimic unpredictable, urgent calls to duty as would be experienced by military or emergency personnel (Langdon & Hartman, 1961). Such studies have investigated sleep inertia after awakenings during the night and after daytime naps (Dinges, Orne, & Orne, 1985). In one such study, it was reported that as wakefulness prior to a 2-hour nap increased from 6 hours to 54 hours, the effects of sleep inertia also increased, with waking performance increasingly impaired with longer wake durations before the nap (Dinges, Orne, Whitehouse, & Orne, 1987). It has also been reported that the deeper the sleep stage just before awakening from the nap, the poorer was waking performance (Dinges et al., 1985). In another study of young subjects, the effects of sleep inertia on performance upon awakening from Stage 2 non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep were more pronounced than those after awakening from REM sleep (Cavallero & Versace, 2003) Those studies indicated that the benefits of napping to counter performance impairments due to sleep loss must be weighed against performance impairments due to sleep inertia after awakening from the nap.

While such approaches have practical applications, they may not be applicable to understanding the effects of sleep inertia from routine or unforced awakenings. One report of the effects of sleep inertia in a group of young subjects found that performance immediately after waking from an 8-hour nighttime sleep episode at habitual bedtime was significantly worse than performance after 26 hours of sleep deprivation (Wertz, Ronda, Czeisler, & Wright, Jr., 2006).

Most previous studies of sleep inertia were conducted in young adults, and it is not clear whether there are sleep inertia effects on performance in older adults, and if so, what factors influence the extent of performance impairments due to sleep inertia in older subjects. It is well established that aging is associated with changes in sleep quality (Dijk, Duffy, & Czeisler, 2001; Webb & Campbell, 1980), and that the prevalence of reported sleep complaints, including difficulty maintaining sleep, early morning awakenings, and daytime sleepiness all increase with age (Foley et al., 1995). Both subjective assessments of early morning awakening (Duffy, Dijk, Klerman, & Czeisler, 1998) and objective measures of sleep duration and consolidation (Dijk, Duffy, Riel, Shanahan, & Czeisler, 1999) demonstrate that older subjects have more difficulty maintaining sleep when it is scheduled at adverse circadian phases than younger subjects. Due to the relative lack of information about sleep inertia effects in older adults, and because of the well-known age-related changes in sleep quality, we conducted a study to examine sleep inertia effects on waking performance in healthy older adults with waketimes scheduled to occur at all circadian phases.

Method

Participants.

Included in these analyses are data from ten healthy older volunteers (age 64.90 ± 5.47 years, range 55–72 years; 5 men, 5 women). Data from an additional older woman were omitted from the analysis due to the fact that her percent of correct responses on the DSST was only 77%, significantly lower than the other ten subjects (range 95%−99% correct). The subjects were medically and psychologically healthy as assessed during a screening evaluation prior to the study, which included a complete physical examination, clinical biochemical tests on blood and urine, an electrocardiogram, psychological questionnaires (MMPI, the Geriatric Depression Scale, and the Folstein Mini-Mental State Exam) and a screening interview with a clinical psychologist to rule out current or past psychopathology. None were under the care of a physician for any chronic medical condition and none were regularly taking medications. Subjects had to report having a habitual sleep duration between 6.5 and 9.5 hours (actual mean ± SD = 7.86 ± 0.95 h) and to have no major sleep complaints, and all were evaluated for sleep disorders prior to admission via overnight polysomnography. Subjects were screened to omit those with clinically-significant sleep apnea (apnea hypopnea index ≥20 per hour and daytime sleepiness as evidenced by an Epworth Sleepiness Scale score >10) or periodic limb movement disorder (periodic limb movement index ≥15 per hour). For three weeks prior to the study, subjects were required to abstain from caffeine, nicotine, alcohol and all medications. Compliance with these criteria was verified upon admission by comprehensive toxicological urine analysis. The study was done in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Human Research Committee of the Partners HealthCare System. Each subject provided written informed consent prior to starting the study.

Experimental procedure.

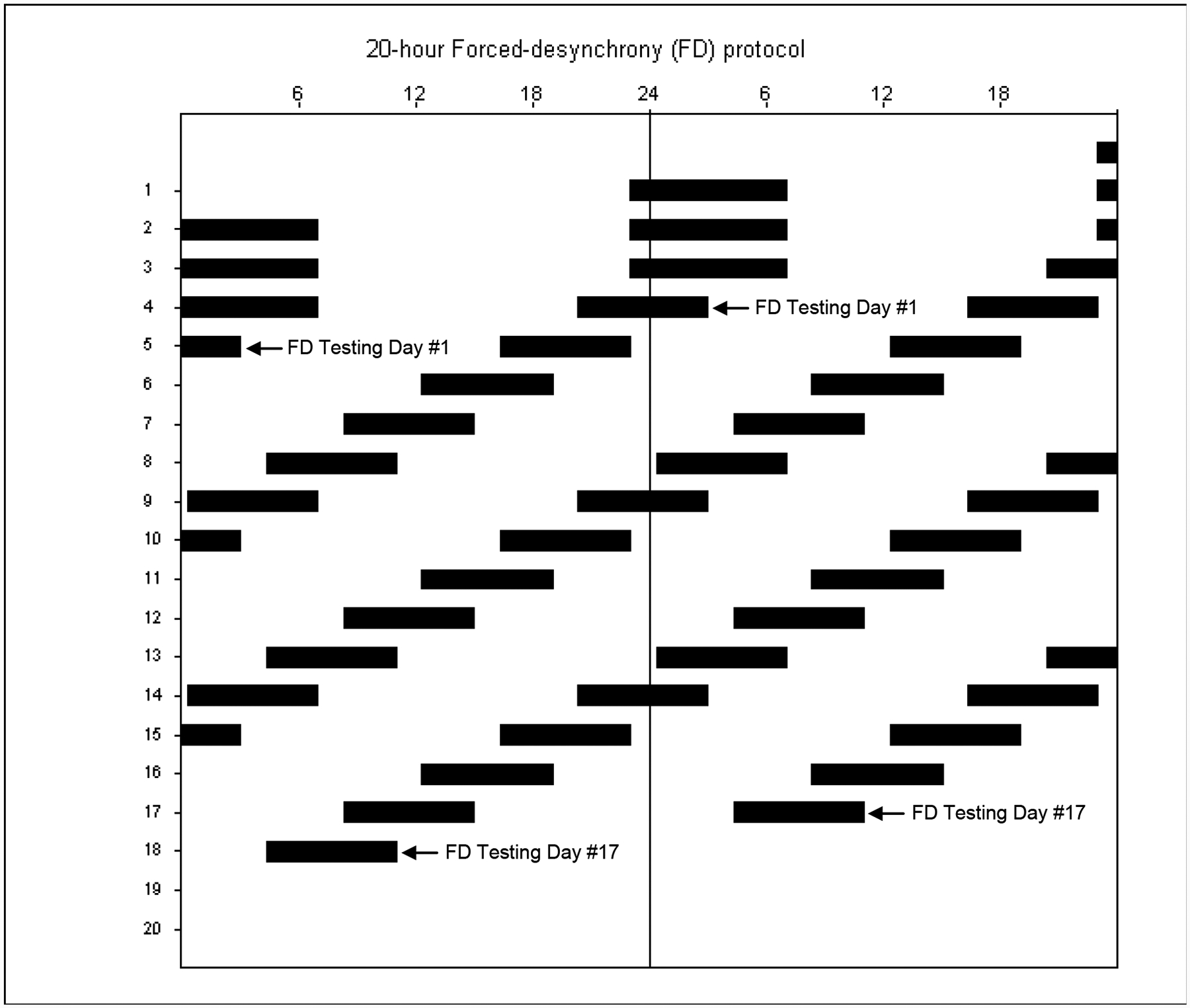

Each study began with 3, 24-hour baseline days consisting of 16 hours of wakefulness and an 8-hour sleep opportunity, scheduled according to each subject’s habitual bed and wake time from the week prior to study. These three baseline days were followed by a forced-desynchrony segment consisting of 18, 20-hour “days,” equivalent to 15 calendar days. Each “day” consisted of 13.33 hours of wakefulness and a 6.67-hour sleep opportunity, with sleep episodes scheduled to begin 4 hours earlier each day (see Figure 1). This resulted in sleep and wake episodes occurring at all circadian phases. Because the first forced-desynchrony day began following the final baseline 8-hour sleep opportunity, there were 17 opportunities to assess waking performance during the forced-desynchrony segment and 3 opportunities to assess waking performance during the baseline segment. For the entire study, each subject lived in a private study room shielded from external time cues, and study staff were trained to avoid any discussion of time of day or day of protocol. Ambient light intensity during all scheduled wake episodes was approximately 0.0087 W/m2 (~3.3 lux) at 137 cm from the floor in the horizontal angle and had a maximum of 0.048 W/m2 (15 lux) at 187 cm from the floor in the vertical direction anywhere in the room (dim indoor room light); during scheduled sleep episodes all lights were turned off (<0.03 lux). Following the forced-desynchrony segment, each subject remained in the study for an additional thirteen calendar days during which they received an investigational medication before each bedtime (results will be reported elsewhere).

Figure 1.

Scheduled sleep-wake cycle of the study protocol plotted in double raster format, with successive days plotted to the right of, and beneath one another. Reference clock hour is indicated along the top axis. Scheduled sleep episodes are represented by the black bars. The first three baseline sleep episodes were scheduled to occur at each subject’s habitual bedtime and last for 8 hours. Beginning on the fourth sleep episode, subjects began the forced-desynchrony (FD) segment of the study, during which they were scheduled to sleep for 6.67 hours, with sleep scheduled to occur 4 hours earlier each day. The arrows mark the first (on Day 5) and last (on Day 18) days of FD sleep inertia testing.

Data collection.

Core body temperature was recorded each minute via rectal temperature sensor (YSI, Yellow Springs, OH, USA) worn throughout the study for assessment of circadian phase and period (see below). For all scheduled sleep episodes, the polysomnogram (PSG) was recorded using a standard montage: electroencephalogram (EEG) was recorded from four derivations (C3, C4, O1, O2) each referenced to the contralateral mastoid; electro-oculogram (EOG; LOC and ROC referenced to the contralateral mastoid); and submental electromyogram (EMG). PSG data were acquired using a Vitaport Digital Sleep Recorder (Temec Instruments, Kerkrade, Netherlands). After each study was complete, PSG data were scored in 30 second epochs according to standard criteria (Rechtschaffen & Kales, 1968) by a trained technologist.

A short performance test battery was scheduled to be administered 1, 10, 20 and 30 minutes after each wake time to assess sleep inertia. At the scheduled wake time, the room lights were automatically turned on via computer and a technician entered the room and ensured that the subject was awake. With the subject remaining in bed, the technician raised the head of the bed, provided the subject with a computer keyboard, and ensured that the computer monitor could be easily viewed by the subject. The subject remained in this position until the final sleep inertia test battery was completed, approximately 35 minutes after scheduled wake time. Each test battery contained a 90-second Digit-Symbol Substitution Test (DSST), which we report here. During the tests and between each test battery, the subject was not allowed to watch videos, listen to music, or read. Study staff remained outside the room during test batteries but did enter the room between batteries. Other performance tests were administered at approximately 120-minute intervals throughout each scheduled wake episode. Those data will be reported elsewhere.

Data analysis.

In some cases, scheduled tests were delayed due to technical problems. We therefore used the actual elapsed time after scheduled wake time that each test was taken in our analyses, rather than the scheduled test time. We then binned tests into one of four 10-minute elapsed time bins. Ranges for each bin (elapsed time since scheduled wake time) were: 1–9; 10–19; 20–29; and 30–39 minutes; any test taken 40 or more minutes after scheduled wake time was excluded from analysis. In all cases, we used the number of correct DSST trials as our performance measure.

Unless otherwise noted, all statistical analyses were conducted via mixed model analysis (SAS 6.12, SAS Institute, Cary, NC), incorporating into the mixed model a random intercept statement allowing for means to vary across subjects, and not assuming an identical intraclass correlation, but rather modeling a different variance component for each subject. Please note that all references to the factor TIME AWAKE treat time after awakening as a categorical, not continuous, variable.

Baseline

Performance data.

DSST observations collected during the baseline days were binned as described above. The mean number of correct DSST trials for each bin were analyzed via mixed model analysis for factors GENDER and TIME AWAKE (time after awakening of each observation).

Sleep data.

Scored PSG data from each sleep episode were assessed to determine the amount of sleep and wakefulness during the last scheduled hour of sleep, and to identify the occurrence of the last epoch of sleep prior to each scheduled wake time.

Forced-desynchrony.

Performance data.

All DSST observations from the forced-desynchrony segment were binned into one of four 10-minute bins with respect to time since awakening, as described above. DSST data from each study day were next assigned to one of six circadian phase bins corresponding to the phase of scheduled wake time on that day (see below). The data were then analyzed via mixed model analysis for factors GENDER, TIME AWAKE (time after awakening of each observation), CIRCADIAN PHASE OF SCHEDULED WAKE TIME, and SLEEP STAGE UPON AWAKENING.

Circadian phase data.

Core body temperature data from the forced-desynchrony segment were assessed for intrinsic circadian period using non-orthogonal spectral analysis (Czeisler et al., 1999). This method takes into account the imposed 20-hour rest-activity schedule and searches for an unknown periodicity in the circadian range (15 to 30 hours). From this estimate of intrinsic circadian period and the program’s projection of the core body temperature nadir at the start of the study segment, a circadian phase (between 0 and 359 degrees) was assigned to each scheduled wake time of the forced-desynchrony segment, with 0° representing the core body temperature minimum. This information was used to assess CIRCADIAN PHASE OF SCHEDULED WAKE TIME.

Sleep data.

Scored PSG data from each sleep episode were assessed to determine the amount of sleep and wakefulness during the last scheduled hour of sleep, and to identify the occurrence of the last epoch of sleep prior to each scheduled wake time. We used this information to select a subset of wake times during which subjects had less than 10 minutes of scored wake in the last hour of the scheduled sleep episode. This information was used to assess SLEEP STAGE UPON AWAKENING.

Results are reported as mean ± standard deviation unless otherwise noted. Results in the Figures are presented as mean ± standard error, with all observations first averaged within, and then across subjects.

Results

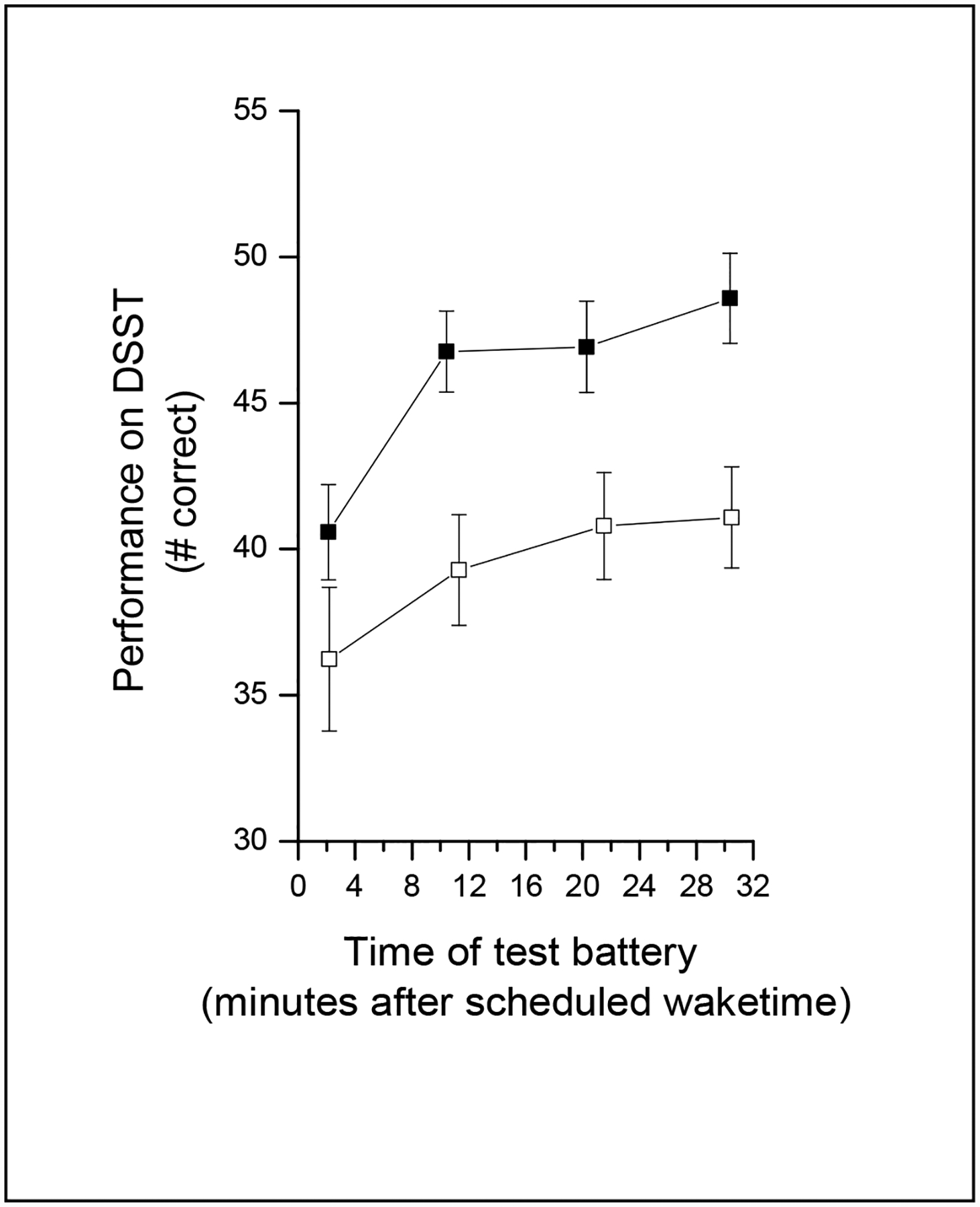

There were thirty opportunities to assess performance after waking from baseline sleep episodes (three wake times each from the ten subjects). During the baseline condition, performance improved the longer a subject was awake across the first 30 minutes of scheduled wake time (effect of TIME AWAKE: F3, 27 = 15.78, P = 0.0001; see Figure 2) but there was no significant effect of GENDER (F1, 30 = 0.36, P = 0.5505). Subjects were on average waking up 13.96 ± 21.76 minutes prior to scheduled wake time (n=27; due to technical problems, sleep data for three baseline sleep episodes were not available), and had been awake on average 23.89 ± 17.88 minutes in the last hour of scheduled baseline sleep. Because of the amount of wakefulness in the baseline sleep episodes and because of prior reports of sleep disruption at adverse circadian phases in older subjects (Dijk et al., 2001; Dijk et al., 1999), our subsequent analyses were restricted to a subset of those wake times during which subjects slept well in the final scheduled hour of sleep.

Figure 2.

Performance across the first 30 minutes of scheduled wake during baseline (open symbols) and forced-desynchrony (filled symbols) conditions. The number of DSST trials completed correctly (mean ± sem) for each of the four test batteries (scheduled to occur 1, 10, 20 and 30 minutes after wake time) are plotted with respect to the time at which each test battery actually occurred.

Of a total of 170 scheduled wake times during the forced-desynchrony condition (17 wake times each from 10 subjects), 57 (ranging from 2–11 wake times from each of the 10 subjects) met the criteria of having less than 10 minutes of wake in the last hour of scheduled sleep. In this subset of waketimes, subjects were waking up 1.35 ± 1.15 minutes prior to scheduled wake time and had been awake only 4.84 ± 2.68 minutes in the last hour of scheduled sleep. On average, the last hour of the scheduled sleep episode in this subset consisted mainly of Stage 2 sleep: 8% wake; 12% Stage 1; 50% Stage 2; 3% Stage 3; 2% Stage 4; and 25% REM.

Accuracy (percentage of correct attempts) was similar in both forced-desynchrony and baseline conditions [forced-desynchrony: 99 ± 2.39 % correct (n=221 observations from 57 waketimes); baseline: 98 ± 2.38 % correct (n=119 observations from 30 waketimes); F1, 69 = 0.19, P=0.6647]. The number of trials completed correctly was greater in the forced-desynchrony condition than in the baseline condition (forced desynchrony: 44.66 ± 9.83; baseline: 39.34 ± 7.42; F1, 69 = 39.00, P=0.0001; see Figure 2). This appears to be due to a practice effect, because a regression line fit through the data from the entire study (baseline + forced-desynchrony) had a positive slope (0.67 ± 0.09). When we compared the number of correct trials from the baseline condition with those from the same circadian phases [0° (n=3) and 60° (n=7)] during the forced-desynchrony condition, the number of correctly-completed trials was significantly greater in the forced-desynchrony condition (F1, 69 = 94.74, P=0.0001).

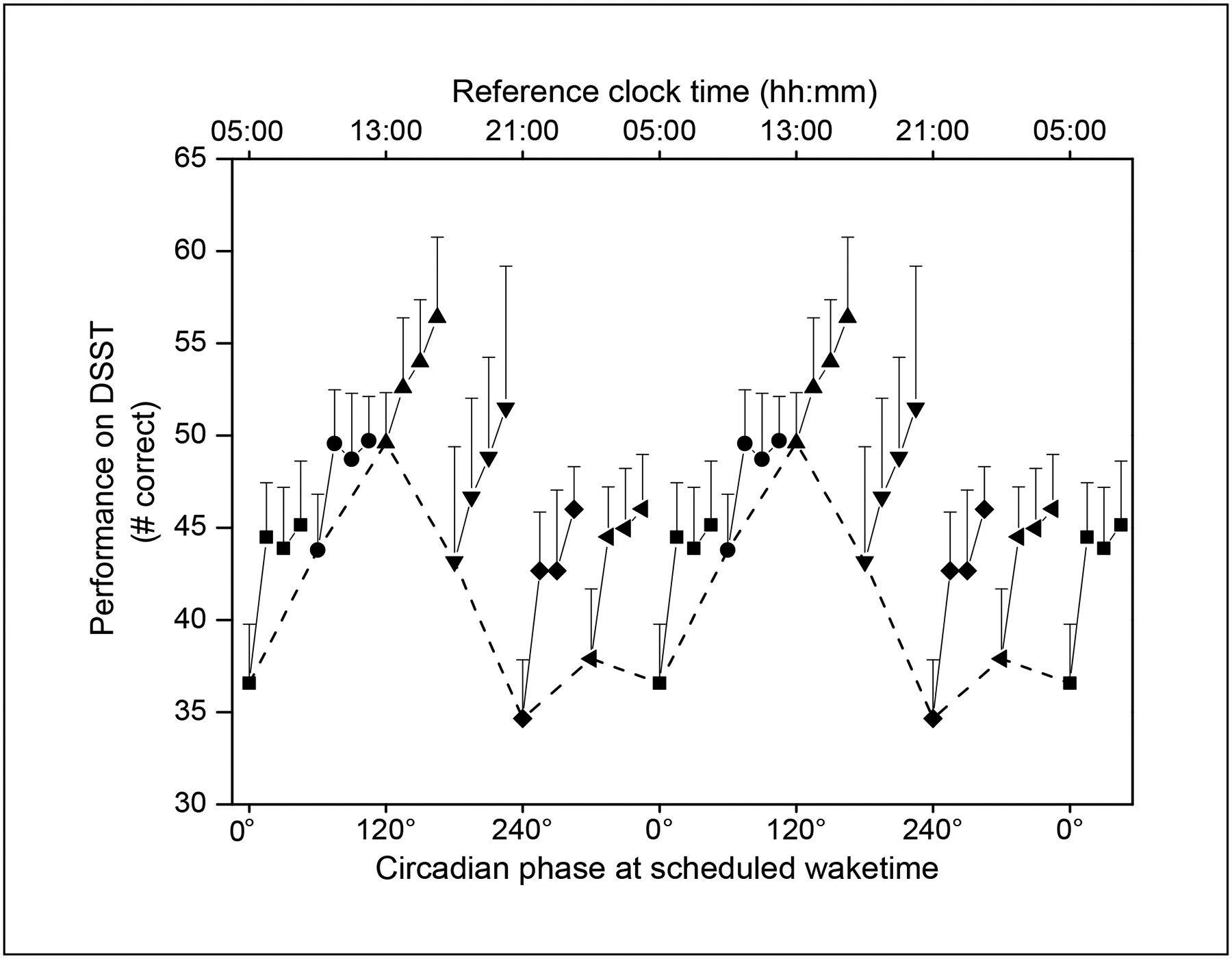

During the forced-desynchrony condition, there was a significant effect of TIME AWAKE (F3, 119 = 28.67, P = 0.0001) on waking performance across the first 30 minutes of scheduled wake time, with better performance the longer a subject was awake (see Figure 2). There also was a significant effect of CIRCADIAN PHASE (F5, 119 = 9.37, P=0.0001), with the worst initial levels of performance when awakening between 240° and 360° / 0°, and the best initial levels of performance when awakening near 120° (see dashed line in Fig 3). There was no significant interaction between CIRCADIAN PHASE and TIME AWAKE, indicating that the improvement in performance was similar regardless of what phase the subject awoke at. There was no significant effect of GENDER (F1,127 = 0.04, P = 0.8396).

Figure 3.

Performance across the first 30 minutes of scheduled wake time during forced-desynchrony plotted with respect to circadian phase at scheduled wake time. Scheduled wake times were binned into 60° circadian phase bins (approximately 4 circadian hours), with 0° corresponding to the core body temperature minimum. Within each circadian phase bin, the number of correct DSST trials (mean + sem) from each of the four sleep inertia batteries are shown connected with a solid line. Note that within each 4-hour circadian phase bin, the 30 minutes of performance data for that bin are presented on an expanded scale, so that the change in performance across the initial 30 minutes of awakening can be better visualized. Data are double plotted, and the initial bin at each circadian phase is shown connected with a dashed line to better visualize the circadian variation of performance upon awakening.

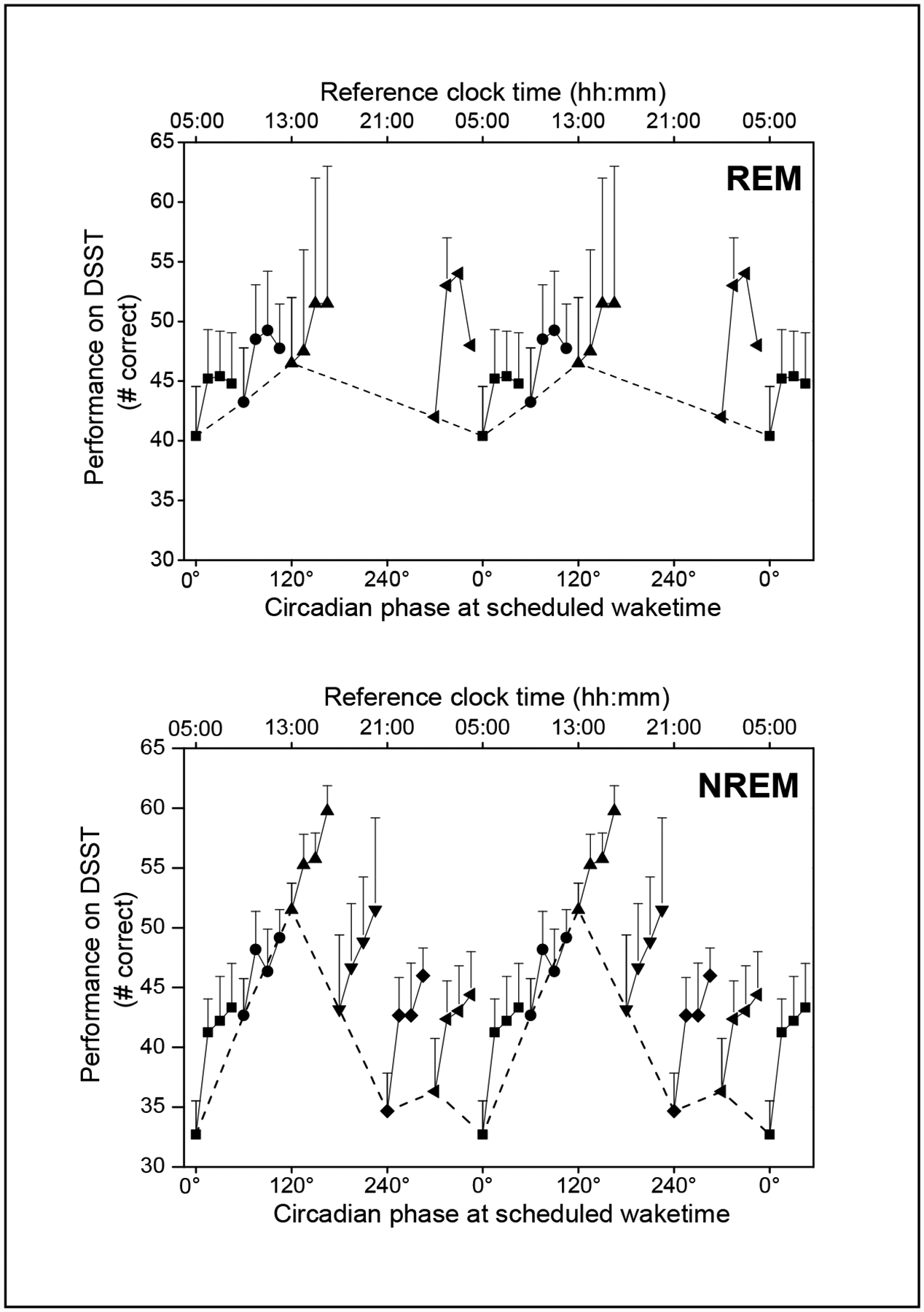

Of the 57 wake times, 13 were from REM sleep, 43 from NREM sleep Stages 1 or 2, and 1 from NREM Stage 3 sleep. We omitted that one wake time from slow wave sleep from our analysis of the effect of sleep stage on performance at wake time. When we added SLEEP STAGE UPON AWAKENING into our mixed model analysis, it was a significant factor (F1, 150 = 10.42, P=0.0015), with better performance when awakening from REM sleep than from NREM Stages 1 or 2 (see Figure 4). TIME AWAKE (F3, 150 = 26.11, P = 0.0001) and CIRCADIAN PHASE (F5, 150 = 10.41, P=0.0001) remained significant effects, indicating that these factors applied to both REM and NREM awakenings. When SLEEP STAGE UPON AWAKENING was re-defined as the predominant sleep stage of the last 5 minutes prior to awakening, as opposed to the last single epoch of scored sleep, only three of the 57 sleep episodes were affected. Mixed model analysis again revealed SLEEP STAGE UPON AWAKENING, TIME AWAKE and CIRCADIAN PHASE to be significant effects on waking performance.

Figure 4.

Performance across the first 30 minutes of scheduled wake time during forced-desynchrony upon awakening from REM (top panel) or NREM Stages 1 or 2 sleep (bottom panel). As in Figure 3, scheduled wake times were binned into 60° circadian phase bins, with 0° corresponding to the core body temperature minimum. Within each circadian phase bin, the number of correct DSST trials (mean + sem) from each of the four sleep inertia batteries are shown connected with a solid line. Data are double plotted, and the initial bin at each circadian phase is shown connected with a dashed line to better visualize the circadian variation of performance immediately upon awakenings. There were no wake times from REM sleep at 180° or 240° which met our criteria for inclusion in the analysis.

When we compared observations from awakenings in the phase bin centered around the core-body temperature minimum (0°), for which the same subjects (n=3) showed both REM and NREM awakenings, a paired t-test confirmed that the level of performance upon awakening from REM sleep was significantly greater than when awakening from NREM sleep (P = 0.0021). When we re-defined SLEEP STAGE UPON AWAKENING as the predominant sleep stage from the last 5 minutes prior to awakening, an additional subject (n=4) showed both REM and NREM awakenings centered around the core-body temperature minimum (0°). When this subject was included in this analysis, the paired t-test no longer showed a significant difference.

Discussion

Our results from the baseline condition demonstrate that sleep inertia effects are present in healthy older subjects sleeping at their habitual times, with performance improving as time awake increases. As is typical for subjects in this age group, most subjects were unable to remain asleep for the entire 8-hour sleep opportunity (Miles & Dement, 1980; Prinz, Vitiello, Raskind, & Thorpy, 1990). We therefore limited our subsequent analyses to only those wake times where the subjects had slept well in the final scheduled hour of sleep. While this reduced our data set, it allowed us to investigate the effects of sleep inertia upon awakening from sleep at different circadian phases without the confound of large differences in duration of wakefulness between phases.

We found a significant effect of circadian phase on performance following awakening, with best initial performance when waking around 120°, corresponding to early afternoon under entrained conditions. Performance was poorest when wake time occurred between 240° and 360° / 0°, phases corresponding to late evening and night under entrained conditions. Consistent with our current finding from older adults, a previous study of sleep inertia in a group of young adults found that sleep inertia effects on performance were greatest when subjects awoke during the biological night compared to waking during the biological day (Rodgers, Czeisler, & Wright, 2006). The circadian phase at which there is the greatest sleep inertia effect has important implications for older adults, because as has been reported previously by our group and others, older adults awaken at a significantly earlier circadian phase under entrained conditions than younger adults (Duffy et al., 2002; Duffy et al., 1998; Lewy, Bauer, Singer, Minkunas, & Sack, 2000).

We also found a significant effect of sleep stage on waking performance, with initial levels of performance better when subjects awoke from REM sleep than performance when they woke from NREM Stages 1 or 2 sleep. This effect of sleep stage was most evident when wake time was scheduled to occur during the late biological night, between 300° and 360° / 0°. Our results are consistent with a prior report from a study in young adults which found that performance after waking from REM sleep was better than performance after waking from Stage 2 NREM sleep (Cavallero et al., 2003). However, in that study sleep was curtailed and subjects were purposefully awakened during REM or Stage 2 NREM sleep, unlike our study in which awakenings occurred after a 6.7-hour scheduled sleep episode.

It has been suggested that in the context of assessing sleep inertia, ‘sleep depth’ is the most important consideration and that the stage of sleep from which awakening occurs is but one facet of sleep depth (Dinges, Orne, & Orne, 1985). Sleep depth in this context has been described as being influenced by not only sleep stage upon awakening, but also the amount of slow wave sleep, number of body movements, response to awakening signals, circadian phase, and rapid return to sleep after awakening. Because our study design consisted of assessing sleep inertia after awakenings at the end of a scheduled 6.7-hour sleep episode, this limited our ability to assess the impact of ‘sleep depth’ on performance after awakening. However, with waketimes scheduled to occur at all circadian phases, we were able to assess two facets of sleep depth in tandem – sleep stage and circadian phase. Furthermore, there was very little slow wave sleep in the final hour of the scheduled sleep episode (only 5% of the epochs), and therefore the amount of slow wave sleep in the pre-awakening period did not influence our comparison of performance upon awakening from NREM versus REM sleep

While we did not compare data from our older subjects with those from young adults, our current results suggest that older adults may experience greater levels of sleep inertia at their usual wake times than younger adults for two reasons. Older adults typically wake at an earlier internal biological time under entrained conditions, closer to the core body temperature nadir when the effects of sleep inertia are greatest. In addition, a previous forced desynchrony study conducted in our laboratory found that older adults are more likely than young adults to have their final awakening from NREM sleep than from REM sleep (Dijk et al., 2001), again, when the effects of sleep inertia are greatest. Together, these two independent factors could make older adults more susceptible than young adults to the effects of sleep inertia. Whether or not this is the case will require future studies in which sleep inertia effects are investigated in both young and older adults in the same study protocol.

Subjects in our study had no chronic medical conditions, no sleep disorders, and were not on medications; therefore, how our findings of sleep inertia effects relate to the more typical older adult population is not clear. Older adults with chronic medical conditions often have sleep maintenance problems (Foley, Ancoli-Israel, Britz, & Walsh, 2004), thus potentially increasing their exposure to sleep inertia effects through more frequent awakenings during the night. Such nighttime awakenings are not usually associated with performing tasks such as those used in our study, and therefore additional studies of more typical older adults using a variety of performance assessments will be needed to determine whether such individuals are more vulnerable to effects of sleep inertia.

Many older adults, including otherwise healthy older adults like those in our study, wake during the night to void (Asplund, 2004; Fonda, 1999), and nocturia has been reported to be a significant risk factor for falls in older adults (Brown et al., 2000; Stewart, Moore, May, Marks, & Hale, 1992). While it is not clear whether sleep inertia plays a role in such nighttime falls, additional studies using other measures of performance, including measures of balance and motor skills, are needed to understand how sleep inertia effects may contribute to nighttime falls in older adults.

Acknowledgements

We thank the subject volunteers for their participation; D. McCarthy for subject recruitment; the nursing and technical staff of the General Clinical Research Center; the Division of Sleep Medicine Sleep and Chronobiology Cores for scoring the PSG recordings; J.M. Ronda for IS support; Dr. W. Wang for statistical advice; and Dr. C.A. Czeisler for overall support. This study was supported by grant AG09975 and was conducted in the Brigham and Women’s Hospital General Clinical Research Center supported by RR02635; data analysis was also supported by grant AG06072 (to JFD).

References

- Achermann P, Werth E, Dijk DJ, & Borbély AA (1995). Time course of sleep inertia after nighttime and daytime sleep episodes. Archives Italiennes de Biologie, 134, 109–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asplund R (2004). Nocturia, nocturnal polyuria, and sleep quality in the elderly. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 56, 517–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balkin TJ & Badia P (1988). Relationship between sleep inertia and sleepiness: cumulative effects of four nights of sleep disruption/restriction on performance following abrupt nocturnal awakenings. Biological Psychology, 27, 245–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JS, Vittinghoff E, Wyman JF, Stone KL, Nevitt MC, et al. , for the Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. (2000). Urinary incontinence: does it increase risk for falls and fractures? Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 48, 721–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavallero C & Versace F (2003). Stage at awakening, sleep inertia and performance. Sleep Research Online, 5, 89–97. [Google Scholar]

- Czeisler CA, Duffy JF, Shanahan TL, Brown EN, Mitchell JF, Rimmer DW et al. (1999). Stability, precision, and near-24-hour period of the human circadian pacemaker. Science, 284, 2177–2181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dijk DJ, Duffy JF, & Czeisler CA (2001). Age-related increase in awakenings: impaired consolidation of nonREM sleep at all circadian phases. Sleep, 24, 565–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dijk DJ, Duffy JF, Riel E, Shanahan TL, & Czeisler CA (1999). Ageing and the circadian and homeostatic regulation of human sleep during forced desynchrony of rest, melatonin and temperature rhythms. Journal of Physiology, 516.2, 611–627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinges DF, Orne MT, & Orne EC (1985). Assessing performance upon abrupt awakening from naps during quasi-continuous operations. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments & Computers, 17, 37–45. [Google Scholar]

- Dinges DF, Orne MT, Whitehouse WG, & Orne EC (1987). Temporal placement of a nap for alertness: contributions of circadian phase and prior wakefulness. Sleep, 10, 313–329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy JF, Dijk DJ, Klerman EB, & Czeisler CA (1998). Later endogenous circadian temperature nadir relative to an earlier wake time in older people. American Journal of Physiology, 275, R1478–R1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy JF, Zeitzer JM, Rimmer DW, Klerman EB, Dijk DJ, & Czeisler CA (2002). Peak of circadian melatonin rhythm occurs later within the sleep of older subjects. American Journal of Physiology, 282, E297–E303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrara M & De Gennaro L (2000). The sleep inertia phenomenon during the sleep-wake transition: theoretical and operational issues. Aviation, Space, and Environmental Medicine, 71, 843–848. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foley D, Ancoli-Israel S, Britz P, & Walsh J (2004). Sleep disturbances and chronic disease in older adults: results of the 2003 National Sleep Foundation Sleep in America Survey. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 56, 497–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foley DJ, Monjan AA, Brown SL, Simonsick EM, Wallace RB, & Blazer DG (1995). Sleep complaints among elderly persons: an epidemiologic study of three communities. Sleep, 18, 425–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonda D (1999). Nocturia: a disease or normal ageing? British Journal of Urology International, 84 Suppl 1, 13–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jewett ME, Wyatt JK, Ritz-De Cecco A, Khalsa SB, Dijk DJ, & Czeisler CA (1999). Time course of sleep inertia dissipation in human performance and alertness. Journal of Sleep Research, 8, 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langdon DE & Hartman B (1961). Performance upon sudden awakening. School of Aerospace Medicine, 62–17, 1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewy AJ, Bauer VK, Singer CM, Minkunas DV, & Sack RL (2000). Later circadian phase of plasma melatonin relative to usual waketime in older subjects. Sleep 23[S2], A188–A189. [Google Scholar]

- Lubin A, Hord DJ, Tracy ML, & Johnson LC (1976). Effects of exercise, bedrest and napping on performance decrement during 40 hours. Psychophysiology, 13, 334–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles LE & Dement WC (1980). Sleep and aging. Sleep, 3, 119–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinz PN, Vitiello MV, Raskind MA, & Thorpy MJ (1990). Geriatrics: sleep disorders and aging. New England Journal of Medicine, 323, 520–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rechtschaffen A & Kales A (1968). A manual of standardized terminology, techniques and scoring system for sleep stages of human Subjects. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers JJ, Czeisler CA, & Wright KP (2006). Influence of circadian phase on sleep inertia. Sleep, 29, A65. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart RB, Moore MT, May FE, Marks RG, & Hale WE (1992). Nocturia: a risk factor for falls in the elderly. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 40, 1217–1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb WB & Agnew H (1964). Reaction time and serial response efficiency on arousal from sleep. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 18, 783–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb WB & Campbell SS (1980). Awakenings and the return to sleep in an older population. Sleep, 3, 41–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wertz AT, Ronda JM, Czeisler CA, & Wright KP Jr. (2006). Effects of sleep inertia on cognition. Journal of the American Medical Association, 295, 163–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]