Abstract

Purpose:

Near-infrared fluorescence (NIRF) imaging has been widely used in preclinical studies; however, its low tissue penetration represents a daunting problem for translational clinical imaging of neurodegenerative diseases. The retina is known as an extension of the central nerve system (CNS), and it is widely considered as a window to the brain. Therefore, the retina can be considered as an alternative organ for investigating neurodegenerative diseases, and an eye represents an ideal NIRF imaging organ, due to its minimal opacity.

Procedures:

NIRF ocular imaging (NIRFOI), for the first time, was explored for imaging of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) via utilizing “smart” fluorescent probes CRANAD-X (X = −2, −3, −30, −58, and −102) for amyloid beta (Aβ), and CRANAD-61 for reactive oxygen species (ROS). Mice were intravenously injected the fluorescence dyes and images from the eyes were captured with an IVIS imaging system at different time points.

Results:

All of the tested NIRF probes could be used to differentiate transgenic AD mice and WT mice, and NIRFOI could provide much higher sensitivity for imaging Aβs than NIRF brain imaging did. Our data suggested that NIRFOI could capture the imaging signals from both soluble and insoluble Aβ species. Moreover, we demonstrated that NIRFOI with CRANAD-102 could be used to monitor the therapeutic effects of BACE-1 inhibitor LY2811376. Compared to NIRF brain imaging, NIRFOI provided a larger change of Aβ levels before and after LY2811376 treatment. In addition, we demonstrated that CRANAD-61 could be used to image reactive oxygen species in the eyes.

Conclusion:

The large detection margin by NIRFOI is very important for both diagnosis and therapy response monitoring. Compared to fluorescence microscopic imaging, NIRFOI captures signals with a wide angle (large field of view (FOV)) and can be used to detect soluble Aβs. We believe that NIRFOI has remarkable translational potential for future human studies and can be a potential imaging technology for fast, cheap, accessible, and reliable screening of AD in the future.

Keywords: Near-infrared fluorescence ocular imaging, Alzheimer’s disease, Amyloid beta, Ocular imaging, NIRF probes

Introduction

Near-infrared fluorescence (NIRF) imaging has been widely used in preclinical studies, due to its low cost, numerous available contrast agents, non-radiation exposure, high throughput capacity, easy operation, and straightforward data analysis [1-5]. However, non-invasive NIRF imaging has limited potential as a clinical imaging technology, due to poor tissue penetration of near-infrared (NIR) light. To avoid this problem, the eye is a natural target for NIRF imaging, due to its minimal opacity for NIR light. Nonetheless, the application of NIRF ocular imaging (NIRFOI) has rarely been investigated. Obviously, NIRFOI has tremendous strength as a clinically applicable imaging technology.

Due to extremely heavy medical and social burdens of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) for today and the future, cheap, fast, reliable, and widely applicable imaging methods are indispensable to relieve the burdens. Currently, memory and behavioral tests are widely used for clinical AD diagnosis [6]; however, these tests are tedious and heavily dependent on medical experts. Although studies indicate that molecular magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and positron emission tomography (PET) are promising diagnostic modalities [7-9], the high-cost PET imaging, narrow availability of PET tracers, and the low sensitivity of MRI are obstacles for their wide applications in both preclinical and clinical studies. Compared to MRI and PET imaging, NIRFOI is an attractive imaging method, because it could be a cheap, fast, reliable, and widely available technology for AD screening.

The retina is widely considered as a window to the brain. Anatomically and developmentally, the retina is known as an extension of the central nerve system (CNS) [10, 11]. Several well-defined neurodegenerative conditions, including AD, that affect the brain have manifestations in the eyes [10, 11]. Therefore, the eye could be used as a window for non-invasively imaging certain CNS diseases. The linkage of brains and eyes in AD pathology is well established, both from morphological changes such as nerve fiber layer thickness and molecular level changes such as deposit of amyloid beta (Aβ) species. Ning et al. reported that APP/PS1 mice developed Aβ deposits in the retina and caused retinal degeneration [12]. We recently showed that aged beagle dogs had abundant Aβ plaques in the retina [13]. Koronyo-Hamaoui et al. showed the formation of Aβ plaques in the retina prior to the appearance of plaques in the brains in APP/PS1 transgenic AD mice [14]. In human eyes, studies have now confirmed that the retina expresses APP and has the necessary cellular machinery to generate Aβs [15, 16]. Several groups and clinical studies have confirmed the existence of Aβ deposits in human eyes [17-21].

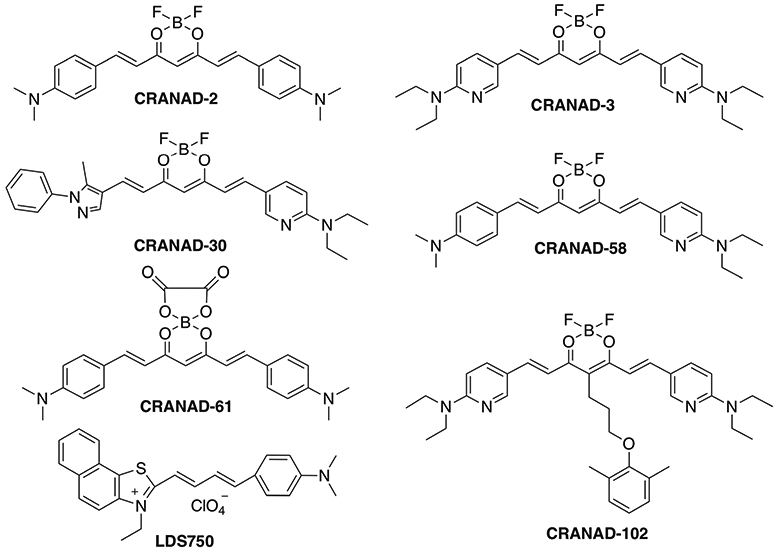

In the past years, we have invented our own brand of imaging probes, called CRANAD-Xs (Fig. 1), which are “smart” imaging probes for various Aβ species. Among them, CRANAD-2, −3, −30, −58, and −102 showed remarkable fluorescence signal increase once they interacted with Aβ species [22-25]. In this report, we used CRANAD-X to conduct NIRFOI imaging. Our results indicated that NIRFOI with CRANAD-X was a very sensitive imaging method for detecting Aβ species, and could be used to monitor the therapeutic effectiveness of a BACE-1 inhibitor [26]. Recently, our group reported that CRANAD-61 (Fig. 1) could be used for imaging reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the brains of AD mice using two-photon imaging and NIRF brain imaging [27]. In this report, our data suggested that CRANAD-61 could also be used to detect the high concentrations of ROS in the eyes of AD mice.

Fig. 1.

Chemical structures of NIRF probes tested in this report.

Materials and Methods

Transgenic female APP-PS1 mice and age-matched wild-type (WT) female mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory. NIRFOI was performed on IVIS® Spectrum (PerkinElmer, Hopkinton, MA). All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Massachusetts General Hospital.

In vivo NIRF Ocular Imaging

In vivo NIRF imaging was performed using an IVIS® Spectrum imaging system (PerkinElmer, Hopkinton, MA). Images were acquired with a 605-nm excitation filter and a 680-nm emission filter. Data analysis was performed using Living Image 4.2.1 software. A 14-month-old mouse (APP-PS1, n = 2–4, and age-matched WT, n = 2–4) was placed in a cassette that is specialized for lateral positioning of an eye, and field of view (FOV) = B was used to cover one eye area. Before injection of CRANAD-X, a background image was captured. An injection solution of CRANAD-X (1.0 mg/kg) was freshly prepared in 15 % DMSO, 15 % cremorphor, and 70 % PBS, and the solution was stabilized for 20 min before injection. Each mouse was intravenously injected with 100 μl of CRANAD-X via tail vein. Fluorescence signals from the eye area were recorded at 0, 15, 30, 60, 120, and 240 min after intravenous injection. To quantify the NIRF signal, an equal size ROI was drawn around the eye region.

NIRFOI Monitor Therapeutic Effectiveness

CRANAD-102 was used to monitor the therapeutic effects of BACE-1 inhibitor LY2811376 in APP/PS1 mice. Four-month-old mice (APP-PS1, n = 5, female) were imaged with CRANAD-102 before treatment, and then the mice were intravenously injected for a continuous 3 days with LY2811376 (100 μl, 2.5 mg/ml, 5 % etholethanol+5 % cremorphor+90 % PBS), based on our previously reported protocol [24]. At day 4, CRANAD-102 (1.0 mg/kg, 15 % DMSO, 15 % cremorphor, and 70 % PBS, 100 μl/mouse) was intravenously injected, and NIRF images were captured from the brain and eyes area at 0, 30, and 60 min post-injection (Ex = 605 nm, Em = 680 nm, and FOV = B). To quantify the NIRF signal, an ROI was drawn around the brain and eye region respectively for each mouse.

Results

Proof-of-concept NIRFOI with Wild-type Mice

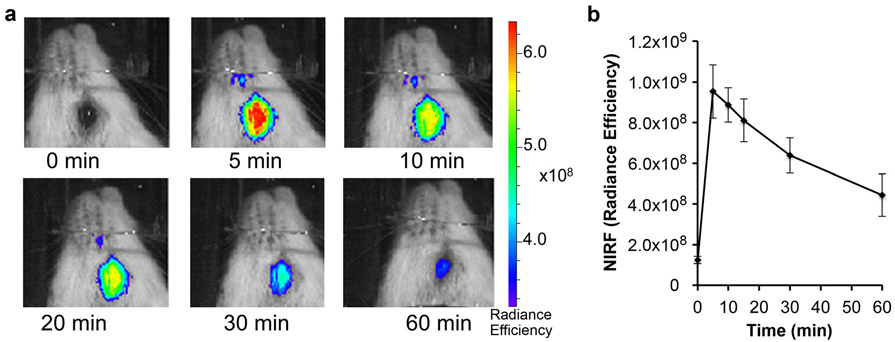

To investigate whether NIRFOI is feasible, we used CRANAD-3 [24] to perform NIRFOI with WT mice. To acquire images, a mouse was placed into a homemade black cassette for lateral positioning to exposure one eye towards the camera of an IVIS imaging system, and a small field of view (FOV = B) was used. As expected, apparent NIRF signals could be captured (Fig. 2a), and the dynamic of CRANAD-3 could be monitored as well (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2.

a Representative NIRF ocular images with CRANAD-3 in WT mice at different time points after injection. b Quantitative analysis of the images (n = 2).

NIRFOI Screening of CRANAD-X with APP/PS1 Mice

For transgenic mice, we used APP/PS1 mice, one of the most widely studied transgenic AD mouse models, to investigate the imaging capacity of CRANAD-Xs. APP/PS1 mice possess double humanized APP and PS1 genes, and constantly produce considerable amounts of “human” Aβ species throughout their lifetimes [28, 29]. Previous studies indicate that APP/PS1 mice have no significant Aβ deposits/plaques before 6 months of age. In this strain, cognitive impairment can be observed around 9 months of age [28, 29].

NIRFOI with Probes Capable of Detecting Both Soluble and Insoluble Aβ Species

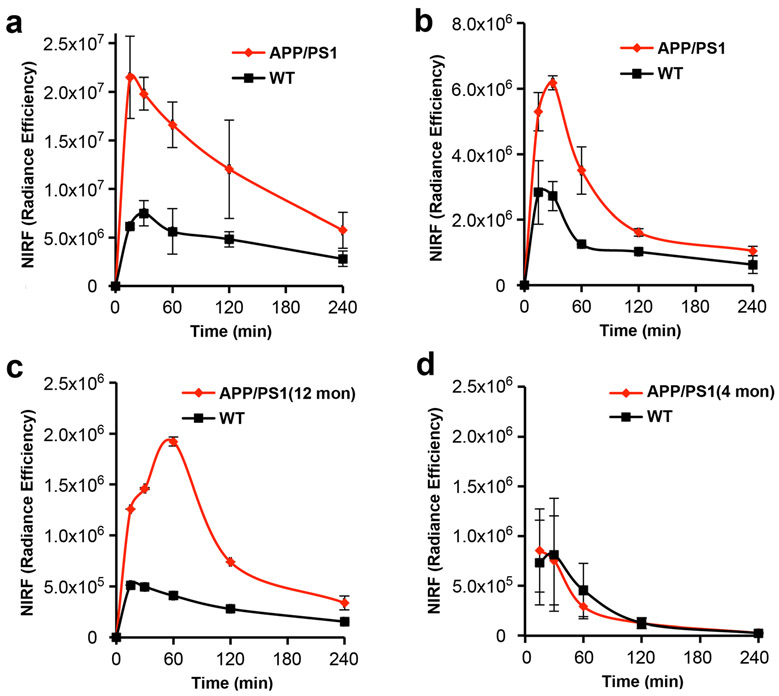

We used CRANAD-3 [24] to investigate the feasibility of NIRFOI to differentiate transgenic AD and age-matched WT mice. CRANAD-3 is capable of detecting both soluble and insoluble Aβs in vitro and in vivo. In this investigation, 14-month-old APP/PS1 mice were used. The mice were injected (iv) with CRANAD-3 and imaged with an IVIS imager with FOV = B. Images were acquired at 5, 15, 30, 60, 120, and 240 min post-injection (p.i.). Quantitative analysis of ROI (region of interesting) of the eye area showed considerable large differences between AD and WT at all of the time points. The largest difference was 3.15-fold (Fig. 3a), which is significantly higher (3.15-fold vs 1.98-fold) than that from brain NIRF imaging with the same probe and with the same dose and imaging parameters. The large difference is very important for diagnosis and therapy monitoring. Meanwhile, we also found that the NIRF intensity of APP/PS1 at 30 min was 10-fold higher than the pre-injection background. The ratio of F(30 min) and F(pre-inj) is also one important fact for reliable quantification, and a probe with a large ratio could have less interference from autofluorescence (NIRF signal from pre-injection).

Fig. 3.

NIRFOI with CRANAD-X (X = −2, −3, and −58). a Time-course of CRANAD-3 in 14-month-old APP/PS1 and WT mice. b Time-course of CRANAD-58 in 14-month-old APP/PS1 and WT mice. c Time-courses of CRANAD-2 in 12-month- and d 4-month-old APP/PS1 and WT mice.

We also investigated whether CRANAD-58 [23], a similar analogue of CRANAD-3, could provide more sensitive detection for Aβs. We found that the F(30 min)/F(pre-inj) was about 4.1-fold, and the differences detected by CRANAD-58 were slightly lower than that from CRANAD-3 (2.80-fold vs 3.15-fold) (Fig. 3a, b). Interestingly, the dynamic of CRANAD-58 in the eyes and brain is different. The NIRF signal in the brain reached the highest within 5 min, while the peak in the eyes reached at 30 min for 14-month-old APP/PS1 mice (Fig. 3b).

NIRFOI with Probes Only Capable of Detecting Insoluble Aβ Species

Our previous data indicated that CRANAD-2 was primarily sensitive for insoluble Aβs [23]. To investigate whether CRANAD-2 can be used to detect Aβ deposits in the eyes, we first followed a similar protocol of CRANAD-3 to image 14-month APP/PS1 mice. As expected, CRANAD-2 was able to differentiate AD and WT mice with a large difference, which was about 2.95-fold. However, the F(30 min)/F(pre-inj) was just about 3-fold (Fig. 3c). To investigate whether CRANAD-2 can be used to image young APP/PS1 mice, we iv injected CRANAD-2 with 4-month-old APP/PS1 mice and age-matched controls, and found that CRANAD-2 was not able to differentiate the two groups (Fig. 3d). This is not a surprise because the Aβs in the brains of 4-month-old APP/PS1 mice were primarily soluble species, but CRANAD-2 is not sensitive for soluble Aβs.

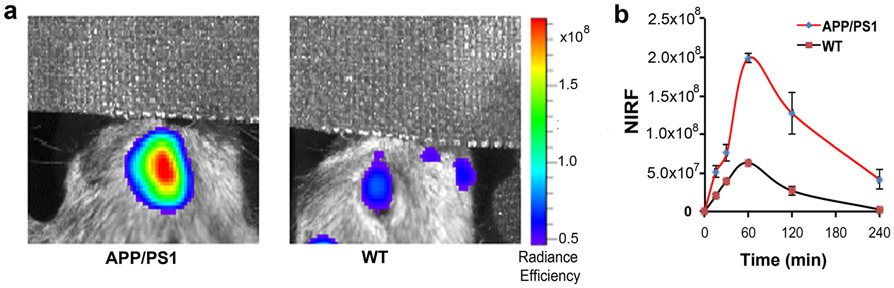

NIRFOI with Probes Selective for Soluble Aβs

Evidence indicates that soluble Aβs are more likely the most toxic species, and can be used as biomarkers for early/pre-symptomatic stage of AD [30, 31]. We have recently developed NIRF probes for selectively imaging soluble Aβs. One of them is CRANAD-102, which showed significantly higher signal for soluble Aβs over insoluble Aβ aggregates [25]. To investigate whether CRANAD-102 can be used for NIRFOI, we first tested it with 14-month-old APP/PS1 mice and age-matched controls. As expected, CRANAD-102 showed significant differences between APP/PS1 and WT (Fig. 4a, b). Its dynamic in the eye was slower than all of the above-tested NIRF probes (Fig. 4b), which is likely due to its hindered structure. CRANAD-102 reached NIRF signal peak around 60 min, and the difference at this time point was about 3.14-fold. To validate whether CRANAD-102 can be used to detect soluble Aβs, we used 4-month-old APP/PS1 mice, in which soluble Aβs are the dominant Aβ species. Indeed, CRANAD-102 provided 2.42-fold higher NIRF signal from APP/PS1 mice than that from the WT controls (SI Fig. 3, see Electronic Supplementary Material (ESM)), indicating CRANAD-102 was capable of imaging soluble Aβs. Interestingly, the dynamic of CRANAD-102 from 4-month-old APP/PS1 mice was different from the 14-month-old APP/PS1 mice, in which the peak shifted to 30 min p.i. (SI Fig. 3 in ESM). This is likely indicating that old mice have large Aβ oligomers that can hold CRANAD-102 longer. The data from CRANAD-2 and CRANAD-102 is complementary, due to each of them having different specificity, i.e., CRANAD-2 is specific to insoluble Aβs; while CRANAD-102 is specific to soluble Aβ species.

Fig. 4.

NIRFOI with CRANAD-102. a Representative images of the eyes of 14-month-old APP/PS1 and WT mice at 60 min after CRANAD-102 injection. b Time-course of CRANAD-102 in 14-month-old APP/PS1 and WT mice.

NIRFOI with Probes of Shorter Excitation/Emission

CRANAD-30 has a high quantum yield, and it showed significant fluorescence intensity increases and emission blue-shifts (620 nm) with Aβs (SI Fig. 1 in ESM). However, its emission (Ex/Em = 572/727 nm) is shorter than that of CRANAD-2, −3, −58, and −102. We have attempted to use CRANAD-30 for brain imaging in APP/PS1 mice but failed to detect significant difference between AD and WT, due to its short Ex/Em. However, we found that CRANAD-30 could be used for ocular imaging of Aβs, and the difference was about 2.97-fold at 30 min p.i. (SI Fig. 2 in ESM). Nonetheless, F(30 min)/F(pre-inj) was only about 3-fold, indicating the short Ex/Em is still a problem for NIRFOI, because the ocular pigment absorbs light with a short wavelength. Collectively, our results indicated that NIRFOI had some advantages over brain NIRF imaging, and probes with excitation around 570 nm and emission around 620 nm could be used for NIRFOI, but not for NIRF brain imaging.

NIRFOI for ROS Imaging

Studies show that ROS concentrations in the brains of APP/PS1 mice are higher than those of age-matched WT mice [32]. Recently, our research groups developed NIRF probes for detecting ROS in the brain, and found that the ROS level in APP/PS1 mice was significantly higher than that in the age-matched controls [27]. However, it is not clear whether the ROS level in eyes of APP/PS1 mice is also higher than that of WT mice. In this regard, we used CRANAD-61, which is a ROS sensitive NIRF probe developed in our group, and its fluorescence could be “turn-off” upon interacting with ROS [27]. We injected CRANAD-61 intravenously into 14-month APP/PS1 mice and control mice. Indeed, similar to the NIRF brain imaging with CRANAD-61, NIRFOI data showed that NIRF signal from the eyes of WT mice was 1.82-fold higher than that from the APP/PS1 mice (SI Fig. 4 in ESM). Our results indicated that the abnormal level of ROS in APP/PS1 brains could be detected by NIRFOI.

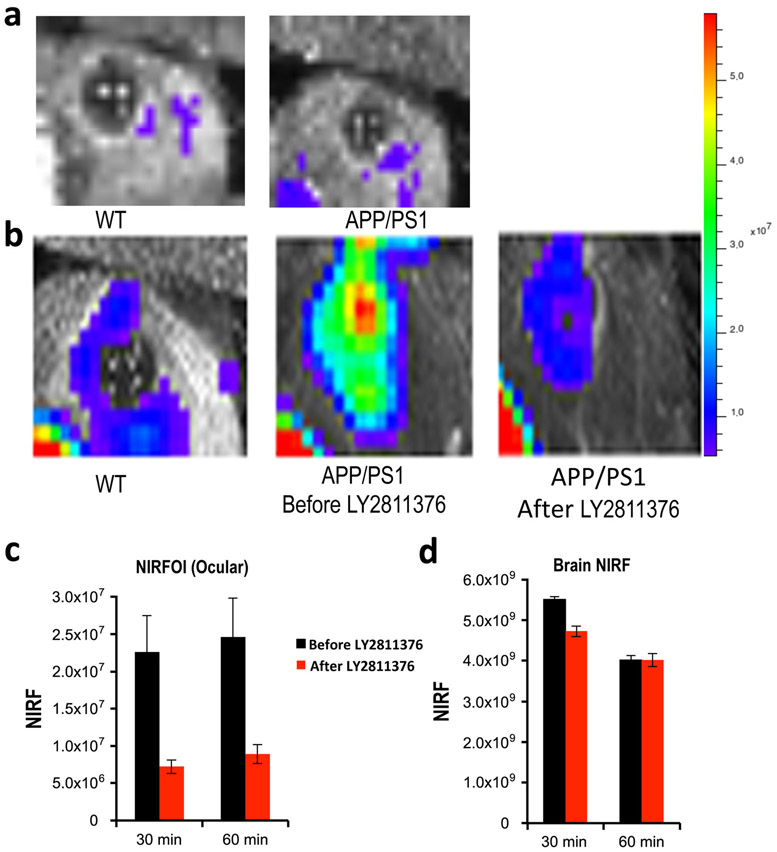

Monitoring Drug Treatment

From our NIRFOI screening of CRANAD-Xs, CRANAD-102 showed highest F(30 min)/F(pre-inj) ratio (30-fold), indicating that CRANAD-102 can provide reliable S/N margins. Moreover, CRANAD-102 detected the largest difference between AD mice and WT mice among CRANAD-Xs; therefore, we decided to test the feasibility of NIRFOI for monitoring therapy with CRANAD-102. For therapy, we selected LY2811376, a well-characterized BACE-1 inhibitor that could lead to 60 % decreasing of the soluble Aβs in the cortex after a single dose (30 mg/kg oral) in mouse studies [26]. As expected, the NIRFOI signal from APP/PS1 mice (n = 5) after LY2811376 treatment (3 days) was 70 % lower than that from the same mice before treatment (Fig. 5a, b). The difference from NIRFOI was significantly higher than that from NIRF brain imaging (about 25 %) (Fig. 5c), indicating that NIRFOI is a more sensitive method for monitoring therapy.

Fig. 5.

NIRFOI for monitoring therapy with Aβ-lowering drug LY2811376. a Representative images of the eyes of 4-month-old WT (left) mice and APP/PS1 mice (right) before the injection of CRANAD-102. b Representative images of the eyes of 4-month-old WT (left) mice and APP/PS1 mice before treatment (middle) and after treatment (right). The images were acquired with CRANAD-102. c Quantification of the ocular NIRF signal differences between before and after treatment with LY2811376. d Quantification of the brain NIRF signal differences between before and after treatment with LY2811376.

Discussion

AD causes a huge societal burden, and the total payments in 2015 for all individuals with AD are estimated at $226 billion in the USA. To reduce the cost of AD care, inexpensive imaging diagnosis with a primary-care setting can be one of the keys. However, currently available imaging diagnostic technologies, such as expensive PET imaging, are nearly prohibitive for community-setting preliminary screening. Near-infrared fluorescence imaging is an ideal choice for a low-cost method. Nonetheless, no prior studies have shown the clinical translational feasibility of NIRF imaging for neurodegenerative diseases. Evidence indicates that early intervention can be a promising approach for slowing down the progression of AD. However, early intervention heavily relies on early detection/diagnosis, which is still under development. Considering the large AD populations, cheap, fast, reliable, and widely applicable imaging methods are indispensable for early diagnostic screening. In this report, considering the retina as a window to the brain, we validated the feasibility of NIRFOI in AD mouse models, and demonstrated that NIRFOI could be a widely affordable imaging method for early detection and for monitoring the change of soluble Aβs during drug intervention.

Koronyo-Hamaoui et al. reported that Aβ plaques in the retina could be detected via a fluorescence microscope with curcumin [14, 17]. However, evidence indicated that Aβ plaques have poor correlation with the severity of sporadic AD, and plaques are not reliable biomarkers for sporadic AD diagnosis [30, 31]. Recently, mounting evidence indicated that soluble Aβs could be the biomarkers for the early stage of AD [30, 33]; however, soluble Aβ does not have morphology that can be observed under a microscope. Therefore, other technology that can be used to quantify the soluble Aβ species is highly desirable. NIRFOI captures signals with a wide angle (large FOV) and can collect all of the signals from Aβ species in the eyes. Therefore, we believe that NIRFOI imaging is one of such technologies that can capture the imaging signals from both soluble and insoluble Aβ species.

Although curcumin has been used for retinal microscopic imaging of Aβ plaques [14, 17], it has limitation of depth penetration due to its short wavelengths of excitation (Ex) and emission (Em) (< 550 nm). The retina has a densely compacted pigmented epithelium cell layer, which can severely interfere with fluorescent signal of curcumin.

Compared to conventional retinal microscopic imaging, NIRFOI has the following general advantages: (1) it covers the whole eye, including the retina, vitreous body, and lens; (2) it has deeper tissue penetration, due to its long Ex/Em of CRANAD-Xs to avoid the absorption of blood and pigments in the retina; (3) it has less autofluorescence due to long excitation; and (4) the quantification of NIRFOI is straightforward. On the contrary, for microscopic imaging, certain criteria, such as plaque size and plaque occupy area, have to be set for quantification, which could be complicated and inaccurate, and (5) NIRFOI could be used for biomarkers that have invisible morphology (such as ROS and soluble Aβs). As known, soluble Aβ does not have morphology that can be observed under a microscope. On the contrary, the conventional retinal microscopic imaging is heavily dependent on visible morphological biomarkers (such as plaques and tau tangles).

In this report, we demonstrated that NIRFOI could provide higher sensitivity for Aβs than brain NIRF imaging does. For the same probe, the difference between AD and WT mice detected by NIRFOI was about 1.5-fold higher than brain NIRF imaging. Obviously, this high sensitivity is very important for both diagnosis and therapy monitoring.

Like most of small molecules, the entry of CRANAD-X into the retina is likely similar to its entry into the brain, which is dependent on its lipophilicity (LogP 1–3.5), and molecular weight (MW < 500), molecular hindrance, and other factors. The differences of kinetics of CRANAD-102 and other CRANAD-Xs are probably due to different molecular hindrance [25]. CRANAD-102 has larger hindrance; therefore, it has slow entry and slow washing-out.

Tau tangles have been reportedly found in the retina of both human and transgenic tau animal models [34, 35]. Gupta et al. reported that retina tau pathology could be observed in human glaucomas [36]. LDS750/PBB5 has recently been reported as a tau imaging agent for transgenic P301L tau mice [37]. In our future studies, we will investigate whether LDS750 can be used to differentiate P301L mice from age-matched WT mice.

In the current studies, the image acquisition was performed on an IVIS imaging system, which has been widely used for whole body imaging of small animals. However, IVIS has some limitations for NIRFOI. With IVIS, each time only one or two mice can be imaged; thus, it always takes a long time to image multiple mice. Because IVIS is designed for whole body imaging, the resolution is not optimized for NIRFOI, and the overlay of photography and NIRF signal is not perfect. Based on the above facts, a special imaging device that can image multiple mice and provide high resolution for the eyes at the same time is urgently needed for future studies.

The investigations in this report also have some limitations. NIRFOI cannot provide spatial resolution for the eyes, and the abnormality of Aβs and tau in the eyes cannot specifically reflect which brain areas have a similar abnormality. Moreover, we also found that eye color has considerable effects on NIRFOI signal. In addition, a special imaging system that can be used to capture images for the eyes is urgently needed for future studies.

Conclusion

In summary, we demonstrated that, for the first time, NIRFOI was feasible, and could be used to image Aβs and ROS in the eyes. Considering the transparency of the eyes, easy operation of the experiments, low cost of the imaging system, and the wide availability of contrast agents, we believe that NIRFOI will have a high impact on medical imaging studies including AD imaging and have tremendous potential for translational studies and clinical applications.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements.

We thank Pamela Pantazopoulos, B.S., for proofreading this manuscript. We also thank China Scholarship Council of Ministry of Education of China for supporting (J.Y. and J.Y.).

Funding This work was supported by R21AG050158, R03AG050038, and R01AG055413 awards from NIA (C.R.).

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (https://doi.org/10.1007/s11307-018-1213-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Rudin M, Weissleder R (2003) Molecular imaging in drug discovery and development. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2:123–131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kobayashi H, Ogawa M, Alford R, Choyke PL, Urano Y (2010) New strategies for fluorescent probe design in medical diagnostic imaging. Chem Rev 110:2620–2640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Staderini M, Martin MA, Bolognesi ML, Menendez JC (2015) Imaging of beta-amyloid plaques by near infrared fluorescent tracers: a new frontier for chemical neuroscience. Chem Soc Rev 44:1807–1819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cui M, Ono M, Watanabe H, Kimura H, Liu B, Saji H (2014) Smart near-infrared fluorescence probes with donor-acceptor structure for in vivo detection of beta-amyloid deposits. J Am Chem Soc 136:3388–3394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ono M, Watanabe H, Kimura H, Saji H (2012) BODIPY-based molecular probe for imaging of cerebral β-amyloid plaques. ACS Chem Neurosci 3:319–324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dubois B, Feldman HH, Jacova C, DeKosky ST, Barberger-Gateau P, Cummings J, Delacourte A, Galasko D, Gauthier S, Jicha G, Meguro K, O’Brien J, Pasquier F, Robert P, Rossor M, Salloway S, Stern Y, Visser PJ, Scheltens P (2007) Research criteria for the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: revising the NINCDS-ADRDA criteria. Lancet Neurol 6:734–746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klunk WE, Koeppe RA, Price JC et al. (2015) The Centiloid Project: standardizing quantitative amyloid plaque estimation by PET. Alz Dement 11:1–15 e11–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jack CR Jr, Garwood M, Wengenack TM, Borowski B, Curran GL, Lin J, Adriany G, Gröhn OHJ, Grimm R, Poduslo JF (2004) In vivo visualization of Alzheimer’s amyloid plaques by magnetic resonance imaging in transgenic mice without a contrast agent. Magn Reson Med 52:1263–1271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Knight MJ, McCann B, Kauppinen RA, Coulthard EJ (2016) Magnetic resonance imaging to detect early molecular and cellular changes in Alzheimer’s disease. Front Aging Neurosci 8:139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.London A, Benhar I, Schwartz M (2013) The retina as a window to the brain-from eye research to CNS disorders. Nat Rev Neurol 9:44–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nguyen CTO, Hui F, Charng J, Velaedan S, van Koeverden AK, Lim JKH, He Z, Wong VHY, Vingrys AJ, Bui BV, Ivarsson M (2017) Retinal biomarkers provide “insight” into cortical pharmacology and disease. Pharmacol Therap 175:151–177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ning A, Cui J, To E, Ashe KH, Matsubara J (2008) Amyloid-beta deposits lead to retinal degeneration in a mouse model of Alzheimer disease. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 49:5136–5143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Emptage L, Hunter JJ, Kisilak ML et al. (2016) Retinal amyloid stained with CRANAD-28 is visible in vivo with fluorescence imaging but not OCT in a canine model of Alzheimer’s disease. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 57:SP 2218 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koronyo-Hamaoui M, Koronyo Y, Ljubimov AV, Miller CA, Ko MHK, Black KL, Schwartz M, Farkas DL (2011) Identification of amyloid plaques in retinas from Alzheimer’s patients and noninvasive in vivo optical imaging of retinal plaques in a mouse model. NeuroImage 54(Suppl 1):S204–S217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson LV, Leitner WP, Rivest AJ, Staples MK, Radeke MJ, Anderson DH (2002) The Alzheimer’s Abeta-peptide is deposited at sites of complement activation in pathologic deposits associated with aging and age-related macular degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci of USA 99:11830–11835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ratnayaka JA, Serpell LC, Lotery AJ (2015) Dementia of the eye: the role of amyloid beta in retinal degeneration. Eye (Lond) 29:1013–1026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koronyo Y, Biggs D, Barron E, Boyer DS, Pearlman JA, Au WJ, Kile SJ, Blanco A, Fuchs DT, Ashfaq A, Frautschy S, Cole GM, Miller CA, Hinton DR, Verdooner SR, Black KL, Koronyo-Hamaoui M (2017) Retinal amyloid pathology and proof-of-concept imaging trial in Alzheimer’s disease. JCI Insight 2:e93621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsai Y, Lu B, Ljubimov AV, Girman S, Ross-Cisneros FN, Sadun AA, Svendsen CN, Cohen RM, Wang S (2014) Ocular changes in TgF344-AD rat model of Alzheimer’s disease. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 55:523–534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Isas JM, Luibl V, Johnson LV, Kayed R, Wetzel R, Glabe CG, Langen R, Chen J (2010) Soluble and mature amyloid fibrils in drusen deposits. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 51:1304–1310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luibl V, Isas JM, Kayed R, Glabe CG, Langen R, Chen J (2006) Drusen deposits associated with aging and age-related macular degeneration contain nonfibrillar amyloid oligomers. J Clin Invest 116:378–385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anderson DH, Talaga KC, Rivest AJ, Barron E, Hageman GS, Johnson LV (2004) Characterization of beta amyloid assemblies in drusen: the deposits associated with aging and age-related macular degeneration. Exp Eye Res 78:243–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ran C, Xu X, Raymond SB, Ferrara BJ, Neal K, Bacskai BJ, Medarova Z, Moore A (2009) Design, synthesis, and testing of difluoroboron-derivatized curcumins as near-infrared probes for in vivo detection of amyloid-beta deposits. J Am Chem Soc 131:15257–15261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang X, Tian Y, Li Z, Tian X, Sun H, Liu H, Moore A, Ran C (2013) Design and synthesis of curcumin analogues for in vivo fluorescence imaging and inhibiting copper-induced cross-linking of amyloid beta species in Alzheimer’s disease. J Am Chem Soc 135:16397–16409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang X, Tian Y, Zhang C, Tian X, Ross AW, Moir RD, Sun H, Tanzi RE, Moore A, Ran C (2015) Near-infrared fluorescence molecular imaging of amyloid beta species and monitoring therapy in animal models of Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112:9734–9739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li Y, Yang J, Liu H, Yang J, du L, Feng H, Tian Y, Cao J, Ran C (2017) Tuning the stereo-hindrance of a curcumin scaffold for the selective imaging of the soluble forms of amyloid beta species. Chem Sci 8:7710–7717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.May PC, Dean RA, Lowe SL, Martenyi F, Sheehan SM, Boggs LN, Monk SA, Mathes BM, Mergott DJ, Watson BM, Stout SL, Timm DE, Smith LaBell E, Gonzales CR, Nakano M, Jhee SS, Yen M, Ereshefsky L, Lindstrom TD, Calligaro DO, Cocke PJ, Greg Hall D, Friedrich S, Citron M, Audia JE (2011) Robust central reduction of amyloid-beta in humans with an orally available, non-peptidic beta-secretase inhibitor. J Neurosci 31:16507–16516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang J, Zhang X, Yuan P, Yang J, Xu Y, Grutzendler J, Shao Y, Moore A, Ran C (2017) Oxalate-curcumin-based probe for micro- and macroimaging of reactive oxygen species in Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 114:12384–12389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Borchelt DR, Thinakaran G, Eckman CB, Lee MK, Davenport F, Ratovitsky T, Prada CM, Kim G, Seekins S, Yager D, Slunt HH, Wang R, Seeger M, Levey AI, Gandy SE, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, Price DL, Younkin SG, Sisodia SS (1996) Familial Alzheimer’s disease-linked presenilin 1 variants elevate Abeta1-42/1-40 ratio in vitro and in vivo. Neuron 17:1005–1013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Delatour B, Guegan M, Volk A, Dhenain M (2006) In vivo MRI and histological evaluation of brain atrophy in APP/PS1 transgenic mice. Neurobiol Aging 27:835–847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Selkoe DJ, Hardy J (2016) The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease at 25 years. EMBO Mol Med 8:595–608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McLean CA, Cherny RA, Fraser FW et al. (1999) Soluble pool of Abeta amyloid as a determinant of severity of neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Neurol 46:860–866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Manczak M, Reddy PH (2012) Abnormal interaction of VDAC1 with amyloid beta and phosphorylated tau causes mitochondrial dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease. Hum Mol Genet 21:5131–5146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sengupta U, Nilson AN, Kayed R (2016) The role of amyloid-beta oligomers in toxicity, propagation, and immunotherapy. EBioMedicine 6:42–49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gasparini L, Crowther RA, Martin KR et al. (2011) Tau inclusions in retinal ganglion cells of human P301S tau transgenic mice: effects on axonal viability. Neurobiol Aging 32:419–433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schon C, Hoffmann NA, Ochs SM et al. (2012) Long-term in vivo imaging of fibrillar tau in the retina of P301S transgenic mice. PLoS One 7:e53547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gupta N, Fong J, Ang LC, Yucel YH (2008) Retinal tau pathology in human glaucomas. Can J Ophthalmol 43:53–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maruyama M, Shimada H, Suhara T, Shinotoh H, Ji B, Maeda J, Zhang MR, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VMY, Ono M, Masamoto K, Takano H, Sahara N, Iwata N, Okamura N, Furumoto S, Kudo Y, Chang Q, Saido TC, Takashima A, Lewis J, Jang MK, Aoki I, Ito H, Higuchi M (2013) Imaging of tau pathology in a tauopathy mouse model and in Alzheimer patients compared to normal controls. Neuron 79:1094–1108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.