Abstract

Objective

Describe the care preference changes among nursing home residents receiving proactive Advance Care Planning (ACP) conversations from health care practitioners during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Design

Retrospective chart review.

Setting and Participants

Nursing home residents (n = 963) or their surrogate decision makers had at least 1 ACP conversation with a primary health care practitioner between April 1, 2020, and May 30, 2020, and made decisions of any changes in code status and hospitalization preferences.

Methods

Health care practitioners conducted ACP conversations proactively with residents or their surrogate decision makers at 15 nursing homes in a metropolitan area of the southwestern United States between April 1, 2020, and May 30, 2020. ACP conversations reviewed code status and goals of care including Do Not Hospitalize (DNH) care preference. Resident age, gender, code status, and DNH choice before and after the ACP conversations were documented. Descriptive data analyses identified significant changes in resident care preferences before and after ACP conversations.

Results

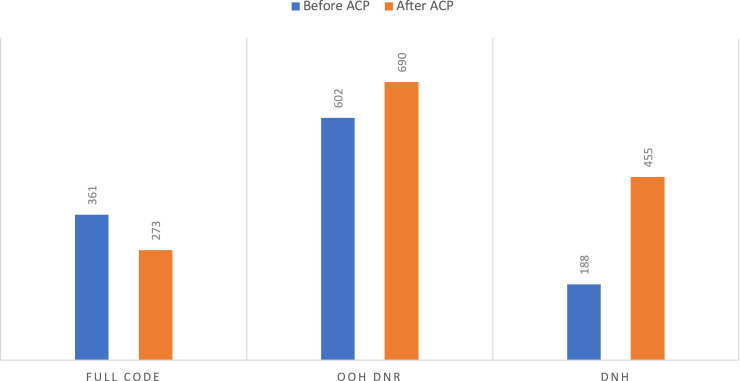

Before the most recent ACP discussion, 361 residents were full code status and the rest were Out of Hospital Do Not Resuscitate (DNR). Of the individuals with Out of Hospital DNR, 188 residents also chose DNH. After the ACP conversation, 88 residents opted to change from full code status to Out of Hospital DNR, thereby increasing the percentage of residents with Out of Hospital DNR from 63% to 72%. Almost half of the residents decided to keep or change to the DNH care option after the ACP conversation.

Conclusion and Implications

Proactive ACP conversations during COVID-19 increased DNH from less than a quarter to almost half among the nursing home residents. Out of Hospital DNR increased by 9%. It is important for all health care practitioners to proactively review ACP with nursing home residents and their surrogate decision makers during a pandemic, thereby ensuring care consistent with personal goals of care and avoiding unnecessary hospitalizations.

Keywords: Advance care planning, nursing home, COVID-19

In 2016, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported a total of 15,600 nursing homes with 1.7 million licensed beds, and approximately 1.3 million residents living in nursing homes in the United States.1 An increasing number of older adults received end-of-life care in nursing homes.2, 3, 4 Advance Care Planning (ACP) is a process for individuals to specify to what extent they would like to receive medical treatment, especially under medical crisis, and to designate a surrogate decision-maker who can direct health care choices consistent with their wishes when they are unable to make their own decisions. ACP is an important step in identifying individuals' preferences toward treatment options and end-of-life care; avoiding aggressive medical care that is inconsistent with an individual's values; and resulting in earlier hospice referral, improvement in quality of life, and reduced medical expenses.5, 6, 7, 8

Hospitalizations are frequently detrimental and burdensome for frail older adults, and can cause serious medical complications.9 Failure to acknowledge and abide by resident preference for treatment and end-of-life care is considered a serious medical error.10 , 11 ACP in nursing homes should address both resuscitation and hospitalization preference.7 The overall hospitalization rate was 1.47 times higher for nursing home residents who had ACP without addressing hospitalization status, and 2 times higher for those without any ACP conversations, compared with individuals with ACP, including addressing hospitalization status.12 More than two-thirds of the nursing home residents had a change in care preference after 1 or more ACP conversations.13 Prior existing ACP orders might not have reflected the residents' preference accurately. The residents' and surrogates' goals of care are dynamic depending on the health conditions and circumstances.13 Therefore, health care providers need to revisit ACP over time to ensure consistency with patients’ goals.

The Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic is clearly changing the health care system. Nursing home residents, who are primarily frail older adults with more than 3 chronic illnesses, have experienced a higher risk for infection and death from severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2).14 The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) reported a total of 164,055 confirmed COVID-19 nursing home resident cases in the United States, with 43,231 deaths as of July 26, 2020.15 Nursing home residents who contract COVID-19 are at a high risk for both hospitalization and intensive care and ventilatory support. Most older adults having increased morbidity and mortality due to COVID-19 did not have adequate ACP before admission to intensive care units.16 Patients/surrogates may not have been informed of the efficacy of proposed aggressive management given prognosis. Hospitals have implemented visitor restrictions to reduce the potential risks of nosocomial SARS-CoV-2 transmission, which increase the difficulties in addressing ACP with surrogate decision makers. Incapacitated COVID-19 residents tend to receive more aggressive treatment that is inconsistent with goals of care when nobody is available at the bedside to speak on their behalf, and clinicians are forced to act quickly under medical crisis.17 Hence, it is extremely important to clarify residents’ preferences and goals of care during the current COVID-19 pandemic.18 Given the at-risk nature of nursing home residents, primary care practitioners should proactively facilitate ACP conversations before a medical crisis. ACP may reduce moral distress among families and health care providers by ensuring that individuals receive care consistent with their values and preferences. The purpose of this study was to describe resuscitation and hospitalization preference changes among nursing home residents after receiving proactive ACP conversations from health care practitioners during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

Three physicians and 20 advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs) who provide primary care services to nursing home residents in a metropolitan area of the southwestern United States, proactively initiated ACP conversations with residents and their surrogates among 15 nursing homes between April 1, 2020, and May 30, 2020, during the COVID-19 pandemic. The physicians, specializing in internal medicine and geriatrics, all had more than 3 years of practice experience in long-term care settings. The APRNs (including nurse practitioners or clinical nurse specialists), specializing in adult or geriatric care, had one-half to more than 10 years of practice experience in long-term care settings. The physicians and APRNs provide primary care services to all of the long-term care residents, and transitional primary care services to residents who stay for short-term skilled nursing rehabilitation. These practitioners had a 1-hour zoom training on initiating ACP conversations during the COVID-19 pandemic by a Board-certified palliative care physician before starting these discussions in nursing homes. Handouts describing topics for the ACP conversation were e-mailed to all practitioners for reference. These included goals of care clarification requiring specific orders in place in the nursing home, such as resuscitation status and hospitalization preference.

Residents’ age, gender, code status, and Do Not Hospitalize (DNH) care choice before the ACP conversations were collected and documented by clinical support staff as of April 1, 2020. Health care practitioners initiated the ACP conversations with the nursing home residents or their surrogates proactively by face-to-face visits or phone calls during the period of April 1 to May 30, 2020, to further clarify goals of care. After the residents or the surrogates confirmed the care decisions, including resuscitation status and DNH preferences, health care practitioners documented the decisions accordingly. For surrogates who did not respond to the first phone contact from health care practitioners, a second attempt was made by the same practitioner during this period. Residents who died or were discharged before having ACP conversations, or whose surrogates did not respond or make a final decision after ACP conversations were excluded from final data analysis. Residents admitted to the nursing homes after April 1, 2020. were not included in data collection.

The Institutional Review Board designated this retrospective chart review of ACP conversation outcomes data as exempt. The researchers (physician, APRN, and university professor) reviewed and summarized these data to examine any changes in the resident care preferences (including resuscitation and DNH status), before and after the ACP conversations. A total of 1112 nursing home residents were included on the initial data collection. During the period of April 1, 2020, to May 30, 2020, 16 patients died, 67 patients were discharged without having ACP conversations, and 66 patients or surrogates still have not responded or made decisions after practitioners’ initiation for ACP conversations. Therefore, A total of 963 (87%) nursing home residents who or whose surrogates had at least 1 ACP conversation with the practitioner were included in the retrospective chart review.

Data analyses were performed using SPSS Premium, Version 26 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). Descriptive statistics including frequencies and measures of central tendency analyzed sociodemographics. McNemar's χ2 statistical analysis compared groups by resuscitation and DNH preference before and after ACP conversations. Furthermore, residents were divided into 4 age groups with approximately one-quarter in each group. Crosstabs with χ2 statistical analyses were performed to examine the relationship between age categories by code status and DNH care choices. Out of Hospital Do Not Resuscitate (DNR) and DNH preference changes before and after ACP conversations in each nursing facility also were examined using descriptive statistics.

Results

A total of 963 residents from 15 nursing homes were included in this retrospective chart review study. Most residents were women (n = 598, 62.1%) versus men (n = 365, 37.9%). Age ranged from 22 years to 105 years (mean = 78 years) (Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Nursing Home Residents’ Information

| Nursing Home Residents' Information | |

|---|---|

| No. facilities | 15 |

| Initial no. residents (as of April 1, 2020) | 1112 |

| No. residents who died (without ACP) | 16 |

| No. residents discharged (without ACP) | 67 |

| No. residents pending decisions after ACP | 66 |

| Final no. residents made decisions after ACP | 963 |

| Average age (y) | 78 |

| Female, n (%) | 598 (62.1) |

| Male, n (%) | 365 (37.9) |

| Full Code (before ACP), n (%) | 361 (37.5) |

| Full Code (after ACP), n (%) | 273 (28.3) |

| Out of Hospital DNR (before ACP), n (%) | 602 (62.5) |

| Out of Hospital DNR (after ACP), n (%) | 690 (71.7) |

| DNH (before ACP), n (%) | 188 (19.5) |

| DNH (after ACP), n (%) | 455 (47.2) |

Data collection period: April 1 to May 30, 2020.

Before the ACP conversation, more than half of the residents had code status listed as Out of Hospital DNR. Approximately one-third of the residents had full code listed in their respective nursing home medical records. Among those having code status listed as Out of Hospital DNR, fewer than a quarter of the residents chose DNH as the hospitalization preference. At the conclusion of the study, 273 residents/surrogates remained full resuscitation whereas 690 residents confirmed code status as Out of Hospital DNR, which increased by 9%. A total of 267 residents/surrogates also changed their hospitalization preferences to DNH, which increased the total percentage of residents with DNH orders to 47.2% (Figure 1 ). Comparisons of resuscitation and hospitalization preference before and after ACP conversations using the McNemar test, identified statistically significant changes for resuscitation (χ2 86.011, P < .001), and hospitalization preference (χ2 265.004, P < .001).

Fig. 1.

Code status and DNH status changes before and after ACP. Nursing home residents changed resuscitation and DNH preference after ACP conversations. Residents remaining full code status decreased from 361 to 273; choosing Out of Hospital DNR increased from 602 to 690. More residents (increased from 188 to 455) chose DNH care option.

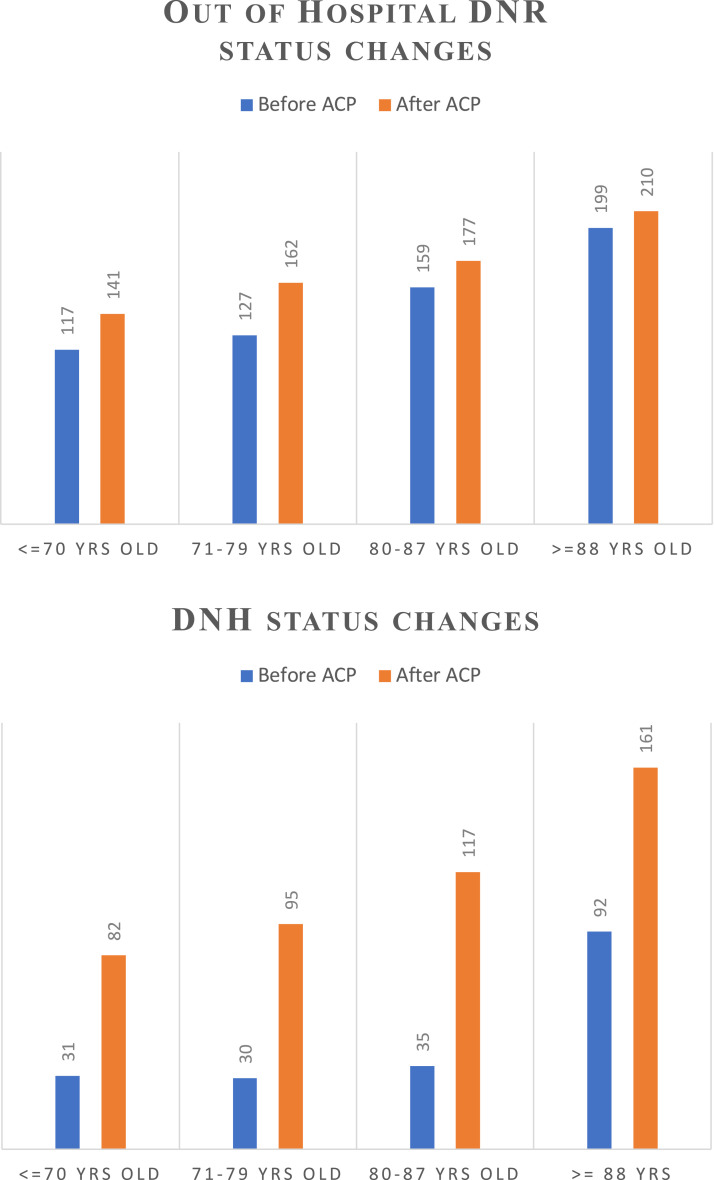

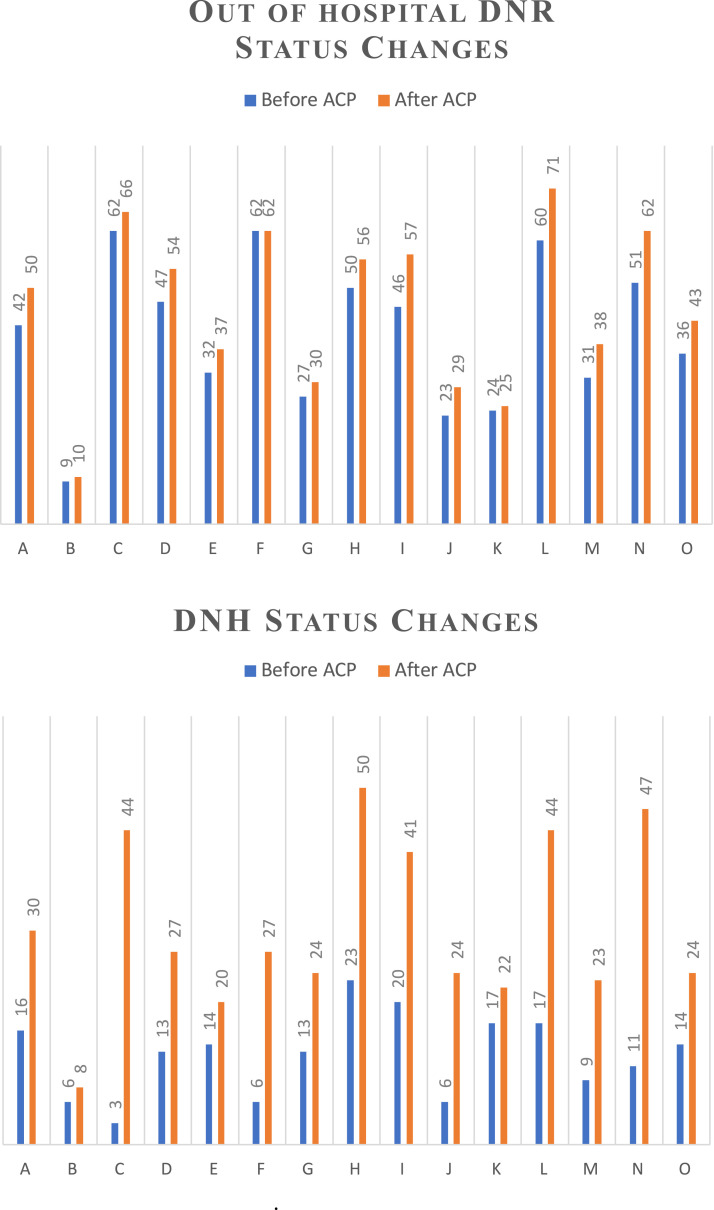

Furthermore, we categorized the nursing home residents into 4 age groups, with one-quarter in each age group. The resuscitation status is significantly different among all age groups before (χ2 110.070, P < .001) and after ACP discussions (χ2 96.160, P < .001). The number of residents who chose Out of Hospital DNR and DNH both increased across all age groups after the ACP conversation (Figure 2 ). More residents older than 88 years chose Out of Hospital DNR as compared with their younger counterparts (≤70 years), and similar findings were noted regarding DNH status. We also examined the data across all 15 nursing homes before and after ACP conversations. Increased number of residents and surrogates changed code status to Out of Hospital DNR after ACP conversations. The number of residents choosing DNH rose in each facility as well (Figure 3 ).

Fig. 2.

Out of Hospital DNR and DNH status changes before and after ACP among different age groups. Nursing home residents were categorized into 4 age groups (≤70; 71–79; 80–87; ≥88) with approximately one-quarter in each group. Increased number of residents across all age groups changed to Out of Hospital DNR and DNH preference after ACP conversations.

Fig. 3.

Out of Hospital DNR and DNH status changes before and after ACP among 15 nursing homes. The changes in Out of Hospital DNR and DNH preference across all 15 nursing homes are listed. The number of residents choosing Out of Hospital DNR and DNH status after ACP conversations has remained the same or increased in each nursing home.

Discussion

ACP involving review of current health status and prognosis, treatment goals, and care preferences with the nursing home residents and their surrogates is important to ensure patient-centered care.19 ACP conversations also enable health care professionals to provide care consistent with nursing home residents' values. Nursing home residents who had focused ACP discussions with their health care providers are 4 times more likely to die in their preferred place.20 , 21 Health care professionals engaging families in ACP conversations is positively associated with the family's decision to limit or withdraw life-sustaining treatments. ACP discussions to explore the end-of-life treatment preferences for the nursing home residents should become routine.22, 23, 24, 25

Frail nursing home residents face significantly higher risk of hospitalization and mortality during the COVID-19 pandemic.14 In addition, not only is the individual risk higher, but the risk is also attributable to all nursing home residents due to the rapid spread of the virus during the pandemic. Recent changes, including strict restrictions for visitors and designated COVID units, also have made the hospital a less geriatric-friendly environment for frail nursing home residents with cognitive impairment. Given the increased risks, prognostic implications, and changes in the material experience and concerns about quality of hospitalizations, nursing home residents and their families might have different views and goals of care specifically regarding resuscitation and hospitalization preference.

This study has demonstrated that nursing home residents and their surrogates do change their care preferences significantly during the current COVID-19 pandemic. Clearly identifying these residents' care preferences can avoid undesired care escalation, which may be especially important at a time when hospital resources may be strained or under increased demand. Furthermore, it also helps nursing home residents, families, and health care professionals to prepare optimally for any potential medical crisis such that appropriate care can be provided to meet residents' and families’ goals, including end-of-life symptom management. It is important for health care providers to proactively carry routine ACP conversations with nursing home residents and their surrogates, especially during any health condition changes.

Limitations of this study include those associated with a retrospective chart review study. The ACP conversation was carried out by more than 20 different practitioners providing primary geriatric services among 15 nursing homes. Although all of the practitioners received a 1-hour training session provided by a board-certified palliative care physician about how to deliver an ACP conversation under the COVID-19 pandemic, the potential exists for variation in competency for delivery of these difficult end-of-life discussions. All of the ACP conversations were conducted and documented during the beginning months of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. As the COVID-19 pandemic evolves, individuals may continue to change their perceptions regarding their health status and goals of care. ACP is a dynamic process, and it may take multiple conversations to clarify the goals of care. Some families need to coordinate with multiple members across the country before they can finalize the care preference for their loved ones residing in nursing homes. Sixty-six families were still pending final care decisions on completion of the data collection; these cases were excluded from these data analyses. A recommendation for future study includes comparisons of rehospitalization rates following ACP conversations with DNH status changes.

Conclusions and Implications

ACP is an important step to identifying individuals’ values, goals, and preferences toward treatment options and end-of-life care. ACP can reduce undesired escalation of care, avoid unnecessary hospitalizations, improve the quality of life, and reduce medical expenses.5, 6, 7, 8 Nursing home residents have experienced a higher risk of hospitalization and death due to the current COVID-19 pandemic. To our knowledge, this is the first study to reevaluate goals of care for nursing home residents using proactive engagement of ACP initiated by health care providers during the current COVID-19 pandemic. It is important to include both resuscitation and DNH preferences in ACP discussions with nursing home residents. Our study has shown that nursing home residents and their surrogates have significantly changed their care preferences after ACP conversations with their primary practitioners during this pandemic. ACP is a dynamic process, and individuals might alter their care preferences and goals of care under any health condition or environmental changes. It is important for all health care professionals to readdress ACP proactively with nursing home residents and their surrogates, thereby ensuring care consistent with personal goals of care and avoiding unnecessary hospitalizations.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to all the practitioners at Austin Geriatric Specialists who initiated the Advance Care Planning conversations with nursing home residents and their families under the current COVID-19 pandemic, and to all the office staff who have helped during the data collection process.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Nursing Home Care. FastStats. Published May 21, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/nursing-home-care.htm Available at:

- 2.Teno J.M., Gozalo P., Mitchell S.L. Survival after multiple hospitalizations for infections and dehydration in nursing home residents with advanced cognitive impairment. JAMA. 2013;310:319–320. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.8392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mitchell S.L., Teno J.M., Miller S.C., Mor V. A national study of the location of death for older persons with dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:299–305. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Houttekier D., Cohen J., Bilsen J. Place of death of older persons with dementia. A study in five European countries. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58:751–756. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02771.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dwyer R., Stoelwinder J., Gabbe B., Lowthian J. Unplanned transfer to emergency departments for frail elderly residents of aged care facilities: A review of patient and organizational factors. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2015;16:551–562. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2015.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Swagerty D. Integrating palliative care in the nursing home: An interprofessional opportunity. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2014;15:863–865. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2014.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abele P., Morley J.E. Advance directives: The key to a good death? J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2016;17:279–283. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2016.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martin R.S., Hayes B., Gregorevic K., Lim W.K. The effects of advance care planning interventions on nursing home residents: A systematic review. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2016;17:284–293. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2015.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O’Malley A.J., Caudry D.J., Grabowski D.C. Predictors of nursing home residents’ time to hospitalization: Predictors of nursing home residents’ time to hospitalization. Health Serv Res. 2011;46:82–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01170.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heyland D.K., Barwich D., Pichora D. Failure to engage hospitalized elderly patients and their families in advance care planning. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:778–787. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Allison T.A., Sudore R.L. Disregard of patients’ preferences is a medical error: comment on “Failure to engage hospitalized elderly patients and their families in advance care planning.”. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:787. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hickman S., Unroe K., Ersek M. Systematic advance care planning and potentially avoidable hospitalizations of nursing home residents (S831) J Pain Symptom Manage. 2019;57:498–499. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hickman S.E., Unroe K.T., Ersek M.T. An interim analysis of an advance care planning intervention in the nursing home setting. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64:2385–2392. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Published February 11, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/older-adults.html Available at:

- 15.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services COVID-19 Nursing Home Data. Published July 26, 2020. https://data.cms.gov/stories/s/COVID-19-Nursing-Home-Data/bkwz-xpvg/ Available at:

- 16.Block B.L., Jeon S.Y., Sudore R.L. Patterns and trends in advance care planning among older adults who received intensive care at the end of life. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180:786–789. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.7535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.The importance of addressing advance care planning and decisions about do-not-resuscitate orders during novel coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) | Critical Care Medicine | JAMA | JAMA Network. https://jamanetwork-com.ezproxy.lib.utexas.edu/journals/jama/fullarticle/2763952 Available at: [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Block B.L., Smith A.K., Sudore R.L. During COVID-19, outpatient advance care planning is imperative: We need all hands on deck. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68:1395–1397. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bollig G., Gjengedal E., Rosland J.H. They know!—Do they? A qualitative study of residents and relatives’ views on advance care planning, end-of-life care, and decision-making in nursing homes. Palliat Med. 2016;30:456–470. doi: 10.1177/0269216315605753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fosse A., Schaufel M.A., Ruths S., Malterud K. End-of-life expectations and experiences among nursing home patients and their relatives—A synthesis of qualitative studies. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;97:3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2014.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abarshi E., Onwuteaka-Philipsen B., Donker G. General practitioner awareness of preferred place of death and correlates of dying in a preferred place: A nationwide mortality follow-back study in The Netherlands. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;38:568–577. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2008.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gonella S., Basso I., Dimonte V. Association between end-of-life conversations in nursing homes and end-of-life care outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2019;20:249–261. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2018.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kastbom L., Milberg A., Karlsson M. ‘We have no crystal ball’ - advance care planning at nursing homes from the perspective of nurses and physicians. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2019;37:191–199. doi: 10.1080/02813432.2019.1608068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gilissen J., Pivodic L., Smets T. Preconditions for successful advance care planning in nursing homes: A systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2017;66:47–59. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2016.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chan H.Y., Pang S.M. Let me talk – an advance care planning programme for frail nursing home residents. J Clin Nurs. 2010;19:3073–3084. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03353.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]