Abstract

Objective

Tracheostomy is an important surgical procedure for coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) patients who underwent prolonged tracheal intubation. Surgical indication of tracheostomy is greatly affected by the general condition of the patient, comorbidity, prognosis, hospital resources, and staff experience. Thus, the optimal timing of tracheostomy remains controversial.

Methods

We reviewed our early experience with COVID-19 patients who underwent tracheostomy at one tertiary hospital in Japan from February to September 2020 and analyzed the timing of tracheostomy, operative results, and occupational infection in healthcare workers (HCWs).

Results

Of 16 patients received tracheal intubation with confirmed severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection, five patients (31%) received surgical tracheostomy in our hospital. The average consultation time for surgical tracheostomy was 7.4 days (range, 6 - 9 days) from the COVID-19 team to the otolaryngologist. The duration from tracheal intubation to tracheostomy ranged from 14 to 27 days (average, 20 days). The average time of tracheostomy was 27 min (range, 17 - 39 min), and post-wound bleeding occurred in only one patient. No significant differences in hemoglobin (Hb) levels were found between the pre- and postoperative periods (mean: 10.2 vs. 10.2 g/dl, p = 0.93). Similarly, no difference was found in white blood cell (WBC) count (mean: 12,200 vs. 9,900 cells /µl, p = 0.25). After the tracheostomy, there was no occupational infection among the HCWs who assisted the tracheostomy patients during the perioperative period.

Conclusion

We proposed a modified weaning protocol and surgical indications of tracheostomy for COVID-19 patients and recommend that an optimal timing for tracheostomy in COVID-19 patients of 2 - 3 weeks after tracheal intubation, from our early experiences in Japan. An experienced multi-disciplinary tracheostomy team is essential to perform a safe tracheostomy in patients with COVID-19 and to minimize the risk of occupational infection in HCWs.

Keywords: Tracheostomy, SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, Surgical strategy, Optimal timing

1. Introduction

An outbreak of the novel coronavirus (severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; SARS-CoV-2) has led to a pandemic of acute respiratory illness termed coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) [1]. Clinical results revealed that patients with severe COVID-19 are likely to be considered for tracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation to support their potential recovery, and in 4% - 5% of such patients, invasive mechanical ventilation is required [2,3]. Tracheostomy is an important surgical procedure for patients with COVID-19 who received prolonged tracheal intubation [4,5], which poses the following clinical question: when should the tracheostomy should be performed? Although delaying the tracheostomy of COVID-19 patients would reduce the occupational infection among healthcare workers (HCWs) in the hospital, an extended duration of tracheal intubation, mechanical ventilation, and intensive care unit (ICU) stay might lead to further complications including ventilator associated pneumonia (VAP). Surgical management recommendations for tracheostomy from international, multidisciplinary experts indicated that tracheostomy should be performed at least 10 days after tracheal intubation in COVID-19 patients [6]. However, the surgical indication for tracheostomy is greatly affected by the general condition of the patient, comorbidity, prognosis, hospital resources, and staff experience. Thus, the optimal timing of tracheostomy remains controversial and highly dependent on the hospital, region, and country.

There is a universal agreement that tracheostomy of COVID-19 patients is associated with an increased risk of viral transmission. When performing tracheostomy in a COVID-19 patient, meticulous attention should be paid to the anesthetic and surgical management details of the tracheostomy to minimize cross-contamination and occupational infection among HCWs [7]. Previous findings on severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) suggested that some procedures capable of generating aerosols, such as tracheal intubation, noninvasive ventilation, tracheostomy, and manual ventilation before intubation, have been associated with an increased risk of SARS transmission to HCWs [8]. Although data on SARS-CoV-2 infectivity are scarce, infection and death among HCWs have been reported [9]. Therefore, to assure the safety of performing a tracheostomy in COVID-19 patients, the establishment of a surgical tracheostomy strategy using appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE) in each hospital is essential. Here, we review our early experience with COVID-19 patients who underwent tracheostomy in Japan and propose a surgical strategy and an optimal timing of tracheostomy that should be adopted by a multidisciplinary tracheostomy team.

2. Materials and methods

We retrospectively reviewed the clinical data from COVID-19 patients who received intensive care and tracheostomy at Nagoya University Hospital from February to September 2020. Clinical data included age, sex, medical comorbidities, laboratory results, intubation history, operative data, complications, and postoperative outcomes. All patients had a documented diagnosis of COVID-19 confirmed using polymerase chain reaction (PCR). This study was approved by the Ethics Review Committee of Nagoya University Hospital (2020–0301).

2.1. Intensive care of COVID-19 patients

Due to the tertiary hospital of our region, severe cases of respiratory conditions or end-stage renal disease requiring hemodialysis maintenance are mainly transferred and treated in our ICU. Intensive drug treatment includes favipiravir, ciclesonide, lopinavir/ritonavir, and systemic corticosteroids, as well as respiratory care, as we previously reported [7,10]. Considerations regarding weaning from mechanical ventilation, even in COVID-19 patients, are similar to the general criteria used for patients with severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) [11,12]. Considering the COVID-19 characteristics (i.e., a lot of sputum in the early phase of the disease), we modified the criteria for assessing the readiness to wean, which consists of an adequate mentation, airway patency and protection, adequate oxygenation, a stable cardiovascular system, and an adequate pulmonary function (Table 1 ). Due to the risk of occupational infection among HCWs and difficulty to perform noninvasive positive pressure ventilation (NPPV) or high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) after extubation, “adequate cough” was deleted from the general criteria, and the stricter criterium of SpO2 (> 94%) was adapted in our hospital.

Table 1.

Considerations for assessing readiness to wean.

| Adequate mentation | Arousable |

| RASS- 1 - 0 | |

| No or minimal continuous sedative infusions | |

| Airway patency and protection | Absence of excessive tracheobronchial secretion |

| Adequate oxygenation | SpO2 > 94% on FiO2 0.4 and PEEP ≦ 8 cm H2O |

| Stable cardiovascular system | HR ≦ 140 beats/min, |

| Stable blood pressure; no or minimal vasopressors | |

| (DOA ≦ 5 µg/kg/min, DOB ≦ 5 µg/kg/min, NAD ≦ 0.05 µg/kg/min) | |

| Adequate pulmonary function | Tidal volume > 5 mL/kg |

| Respiratory frequency/tidal volume < 105/min/L | |

| No significant respiratory acidosis (pH > 7.25) |

RASS: Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale, PEEP: positive end-expiratory pressure, HR: heart rate, DOA: dopamine, DOB: dobutamine, NAD: noradrenaline.

2.2. Surgical indication of tracheostomy in COVID-19 patients

For the COVID-19 patients who received a prolonged tracheal intubation (7 - 10 days), extubating the tracheal tube or performing tracheostomy was considered. Firstly, we tried to identify the patients who were ready to wean from mechanical ventilation using the criteria in Table 1, and then, we determined whether patients could be successfully extubated using a spontaneous breathing trial (SBT) as a diagnostic test, which was usually performed with low levels of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) (e.g. 5 - 7 cm H2O), low levels of pressure support (e.g. 5 – 7 cm H2O), and at least for 30 min. Patients who were not applicable for assessing the readiness to wean, failed the SBT, and required re-tracheal intubation underwent tracheostomy. Tracheostomy is often considered after initiation of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) in patients with respiratory failure to improve patient comfort and allow the lightening of sedation. Because critically-ill COVID-19 patients treated with VV-ECMO are expected to have a prolonged tracheal intubation, we tended to perform tracheostomy earlier than usual. Our general criteria to perform tracheostomy in COVID-19 patients are listed in Table 2 . We carefully discussed the condition of each patient and determined the optimal timing of tracheostomy based on the hospital resources and staff. Our multidisciplinary tracheostomy team consisted of experienced personnel (at least two board certificated otolaryngologists, one critical care and emergency doctor, and one critical care nurse) to minimize the operating time and to avoid occupational SARS-CoV-2 infection. Tracheostomy was performed in an isolation room in our ICU.

Table 2.

Surgical tracheostomy strategy in COVID-19 patients.

| Factors | Considerations |

|---|---|

| Patient | Stable general condition |

| Over 14 days after tracheal intubation | |

| Not applicable for assessing readiness to wean | |

| Failure of SBT | |

| Re-intubation | |

| Severe disease with VV-ECMO | |

| Equipment | Appropriate personal protective equipment available |

| An isolation room (desirable negatively pressured isolation room) available | |

| Staff | Enough airway management training for all staff elements |

| Experienced tracheostomy team available |

SBT: spontaneous breathing trial, ECMO: extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

2.3. Anesthetic and surgical management of tracheostomy in COVID-19 patients

We have previously described tracheostomy management, such as preoperative preparation, enhanced PPE, and surgical protocol [7]. All surgical staff used PPE, such as a N95 mask or a clean space powered air-purifying respirator (PAPR), goggles, a face shield, cap, double gloves, and a water-resistant disposable gown (Fig. 1 a). Due to the isolated environment and limited staff in the operating room, the tracheostomy set, such as knife, forceps, bobby, and several types of hooks were carefully prepared before the tracheostomy (Fig. 1b). After setting the surgical position with the patient neck stretched, a multidisciplinary tracheostomy team performed an open tracheostomy with an inverted U-shaped tracheal flap for an easy exchange of the tracheostomy tube (Fig. 1c). Importantly, the PPE should be removed by a non-contact person to avoid self-contamination and exposure to surrounding people.

Fig. 1.

Preparation of tracheostomy in patients with COVID-19, including PPE and tracheostomy set.

2.4. Statistical analysis

To assess the influence of tracheostomy in COVID-19 patients, we compared the pre- (one day before the tracheostomy) and the postoperative blood test (one day after the tracheostomy) results using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Descriptive statistics were obtained using JMP (Version 10, SAS, Cary, North Carolina, USA). A two-sided p-value of 0.05 or lower was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of patients

From February to September 2020, 16 patients with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection received tracheal intubation with intensive care in our hospital (Nagoya University Hospital), among whom surgical tracheostomy was performed in 5 patients (31%). The characteristics of patients are shown in Table 3 . The average consultation time for surgical tracheostomy was 7.4 days (range, 6 - 9 days) from the ICU COVID-19 team to the otolaryngologists. The duration from tracheal intubation to tracheostomy ranged from 14 to 27 days (average, 20 days). All COVID-19 patients who underwent tracheostomy received antibiotic treatment before tracheostomy because of VAP or possible VAP related to tracheal intubation.

Table 3.

Characteristics of patients.

| Case | Age(years) | Sex | Comorbidity | Duration from first symptom to tracheal intubation (day) | Duration from tracheal intubation to tracheostomy (day) | Duration from consultation to tracheostomy (day) | Operating time (min) | Complications | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 74 | Male | HT, DM, BA | 10 | 17 | 6 | 33 | None | Alive |

| 2 | 52 | Female | DM, ESRD | 7 | 27 | 6 | 27 | Bleeding | Alive |

| 3 | 53 | Male | DM, MI | 10 | 21 | 9 | 39 | None | Alive |

| 4 | 79 | Male | HT, DM, ESRD | 1 | 14 | 8 | 22 | None | Alive |

| 5 | 70 | Male | CHF, Fallot ope | 14 | 21 | 8 | 17 | None | Dead |

HT: hypertension, DM: diabetes mellitus, BA: bronchial asthma, ESRD: end-stage renal disease requiring hemodialysis maintenance, MI: myocardial infarction, CHF: chronic heart failure.

3.2. Outcomes of tracheostomy in 5 COVID-19 patients

Surgical tracheostomy was performed in 5 COVID-19 patients by our experienced tracheostomy team to minimize the risk of virus infection in HCWs. The average time of tracheostomy was 27 min (range, 17 - 39 min), and was no loss of a large amount of blood. No significant differences in hemoglobin (Hb) levels were found between the pre- and postoperative periods (mean: 10.2 vs. 10.2 g/dl, p = 0.93). Similarly, no difference was found in white blood cell (WBC) (mean: 12,200 vs. 9900 cells /µl, p = 0.25). Postoperative chest radiography showed no clinical progression of the respiratory condition. Although postoperative bleeding from the surgical wound occurred in one patient, it was easily controlled with an absorbable hemostat, and no additional treatment was required.

After the tracheostomy, there was no occupational infection among the HCWs who assisted the tracheostomy patients during the perioperative period.

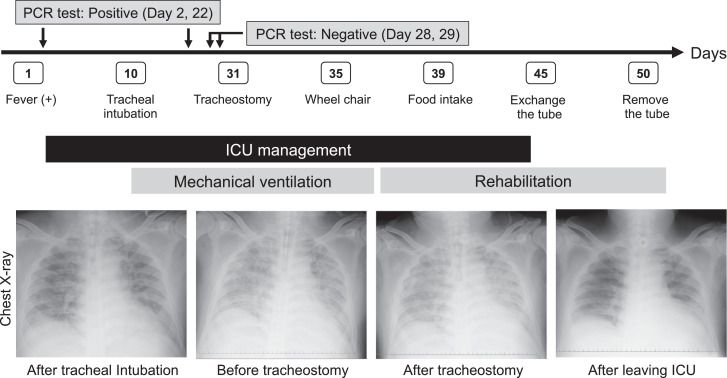

3.3. Representative case

A 53-year-old man experienced a slight fever on day 1 and underwent tracheal intubation for mechanical ventilation on day 10. Due to a prolonged tracheal intubation, surgical tracheostomy was performed on day 31 in a negative-pressure airborne infection isolation room in our ICU. Fig. 2 shows the clinical course of the patient and the chest radiological findings during the treatment. After the tracheostomy, his respiratory and general conditions gradually improved, and thus, his tracheostomy tube could be removed on day 50.

Fig. 2.

Clinical course and chest radiological findings in a COVID-19 patient undergoing tracheostomy.

4. Discussion

Tracheostomy is a safe and effective surgical procedure for patients with prolonged tracheal intubation, such as acute respiratory failure. Although recent clinical results showed the safety and usefulness of tracheostomy in COVID-19 patients [13,14], no specific weaning protocol and no surgical indications for tracheostomy have been defined for COVID-19 patients at the present. Decision making around tracheostomy in COVID-19 patients would be mainly based on standard weaning procedure [12,15]. However, decision makers have to consider both of patient's benefits and an occupational infection of SARS-CoV-2 in HCWs during the COVID-19 pandemic. In this paper, we reviewed our early experiences of tracheostomy in COVID-19 patients in Japan and proposed a modified weaning protocol and surgical indications of tracheostomy for COVID-19 patients as shown in Table 1, 2. For example, the stricter criterium of SpO2 (> 94%) was adapted in our strategy due to difficulty of performing NPPV or HFNC after extubation for COVID-19 patients. Considering the general condition of each patient, hospital resources and staff experience, clinicians should determine whether tracheostomy is truly beneficial or not in COVID-19 patients with prolonged intubation.

Despite the efficiency of tracheostomy in COVID-19 patients, the optimal timing of tracheostomy remains controversial. Traditionally, a tracheostomy is performed to accelerate ventilator weaning, to enhance clearance of secretions, to improve patient mobility, to reduce VAP, and to increase potential for speech, ability to eat orally [16]. In randomized controlled trials that compared early and late tracheostomies, the timing of tracheostomy was divided as follows: very early (< 4 days), moderately early (< 10 days) and late (> 10 days) tracheotomies [17], [18], [19]–20]. The TracMan study, which was one of the first multi-center studies to evaluate tracheostomy timing, demonstrated that very early tracheostomy (< 4 days) was associated with shorter duration of sedation but made no difference in 30-day mortality or length of stay in the ICU or hospital [17]. Although one systematic review of 12 randomized studies revealed that early tracheotomy was associated with more ventilator-free days, shorter ICU stays, and reduced long-term mortality, compared to late tracheotomy [21], a specific attention should be paid to the timing of tracheostomy in COVID-19 patients in terms of the characteristics of infectious diseases. We performed tracheostomy in COVID-19 patients with an average of 20 days from tracheal intubation to tracheostomy under enhanced PPE. Our tracheostomy timing is consistent with recent recommendations or guidelines for COVID-19 patients, which suggests performing tracheostomy 2 - 3 weeks after tracheal intubation [4,[22], [23]–24]. It has been reported that SARS-CoV-2 viral loads in upper respiratory specimens of infected patients are the highest in the early stages of the disease with typical clearance by 2 weeks [25]. While SARS-CoV-2 viral loads do not correlate well with the severity of symptoms or the risk of cross-infection in HCWs, there are minimal clinical data regarding an early tracheostomy (< 14 days) in ventilated COVID-19 patients [26], suggesting that an early tracheostomy (< 14 days) should only be performed in some selected COVID-19 patients [24]. Considering an increased risk of VAP due to prolonged tracheal intubation, we recommend that the timing of tracheostomy consultation should be within 7 - 10 after tracheal intubation and the optimal timing for tracheostomy in COVID-19 patients should be 2 - 3 weeks after tracheal intubation. However, our results are based on a small population of one tertiary hospital in the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan. Thus, the optimal timing of tracheostomy should be investigated in a larger patient population from a multi-center study.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, tracheostomy, including open and percutaneous tracheostomy, is recommended to be performed by a team consisting of the least number of providers with the highest level of experience possible [27]. Percutaneous tracheostomy is one of the effective methods and results in a lower postoperative bleeding complication rate. However, it is controversial which procedures are suitable to prevent SARS-CoV-2 aerosolization. Recent US and UK studies have suggested that open tracheostomy is as favorable as percutaneous tracheostomy for COVID-19 patients, being safe for clinicians [13,28]. In our experience with open tracheostomy, there were no severe surgical complications or occupational infection among HCWs who participated in the tracheostomy. Regardless of the type of tracheostomy, the most important thing is to avoid of SARS-CoV-2 aerosolization during the procedure. To benefit both the patient and the HCWs, the most reliable and familiar procedure in each hospital should be considered and selected.

As SARS-CoV-2 is thought to spread through contact and droplet infection, careful attention should be paid during airway management. To improve the safety of airway procedures in COVID-19 patients, we previously developed a new reusable type of equipment, which consists of a transparent plastic shield with a sloping angled surface and a plastic drape attached to the top and side edges of the shield [29]. To protect HCWs from occupational SARS-CoV-2 infection, an appropriate and strict infection prevention is critical for aerosol-generating medical procedures, such as tracheal intubation, bronchoscopy, and tracheostomy [8]. When performing the tracheostomy in the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic, it was essential to establish an experienced multi-disciplinary tracheostomy team to minimize occupational infection in HCWs. In a clinical setting, it is necessary to prepare hospital resources, such as PPE and staff, and to obtain written informed consent from the family of the patient before the tracheostomy. In our experience, tracheostomy was performed within 7.4 days, on average, from the consultation, suggesting that one week is reasonable to prepare and perform a safe tracheostomy in COVID-19 patients. Notably, as we demonstrated in this paper, an experienced multi-disciplinary tracheostomy team is essential to perform a safe and quick tracheostomy, resulting in clinical benefits for both COVID-19 patients and the HCWs of the hospital.

The PCR test for SARS-CoV-2 is useful for the initial diagnosis of COVID-19 infection and the follow-up testing is important to assure its clearance. Previously, we determined the timing of tracheostomy after confirmation of, at least, two negative PCR results for SARS-CoV-2. However, the detection rate from several samples varies with the upper and lower respiratory sites, and most patients undergoing tracheostomy are in the convalescent phase (14 - 21 days) [27]. Thus, as long as the tracheostomy for COVID-19 is performed under enhanced PPE, the PCR test for SARS-CoV-2 is not mandatory to decide the timing of tracheostomy in COVID-19 patients. Finally, no occupational SARS-CoV-2 infection occurred in HCWs during intensive care in our early experiences of COVID-19 in Japan. Although there is a lack of evidence for COVID-19, we should not overestimate the occupational SARS-CoV-2 infection in the hospital or miss the optimal timing of tracheostomy in patients who really need intensive treatment to recover from illness.

5. Conclusion

We proposed a modified weaning protocol and surgical indications of tracheostomy for COVID-19 patients and recommend that an optimal timing for tracheostomy in COVID-19 patients of 2 - 3 weeks after tracheal intubation, from our early experiences in Japan. An experienced multi-disciplinary tracheostomy team is essential to perform a safe tracheostomy in COVID-19 patients and to minimize the risk of occupational SARS-CoV-2 infection in HCWs.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest to declare.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing.

References

- 1.Zhu N., Zhang D., Wang W., Li X., Yang B., Song J. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China. N Engl J Med 2020. 2019;382(8):727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang C., Wang Y., Li X., Ren L., Zhao J., Hu Y. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan. China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen N., Zhou M., Dong X., Qu J., Gong F., Han Y. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):507–513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.David A.P., Russell M.D., El-Sayed I.H., Russell M.S. Tracheostomy guidelines developed at a large academic medical center during the COVID-19 pandemic. Head Neck. 2020;42(6):1291–1296. doi: 10.1002/hed.26191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang X., Huang Q., Niu X., Zhou T., Xie Z., Zhong Y. Safe and effective management of tracheostomy in COVID-19 patients. Head Neck. 2020;42(7):1374–1381. doi: 10.1002/hed.26261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McGrath B.A., Brenner M.J., Warrillow S.J., Pandian V., Arora A., Cameron T.S. Tracheostomy in the COVID-19 era: global and multidisciplinary guidance. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(7):717–725. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30230-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hiramatsu M., Nishio N., Ozaki M., Shindo Y., Suzuki K., Yamamoto T. Anesthetic and surgical management of tracheostomy in a patient with COVID-19. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2020;47(3):472–476. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2020.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tran K., Cimon K., Severn M., Pessoa-Silva C.L., Conly J. Aerosol generating procedures and risk of transmission of acute respiratory infections to healthcare workers: a systematic review. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(4):e35797. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chu J., Yang N., Wei Y., Yue H., Zhang F., Zhao J. Clinical characteristics of 54 medical staff with COVID-19: a retrospective study in a single center in Wuhan. China. J Med Virol. 2020;92(7):807–813. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koshi E., Saito S., Okazaki M., Toyama Y., Ishimoto T., Kosugi T. Efficacy of favipiravir for an end stage renal disease patient on maintenance hemodialysis infected with novel coronavirus disease. CEN Case Rep. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s13730-020-00534-1. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.MacIntyre N.R., Cook D.J., Ely E.W., Epstein S.K., Fink J.B., Heffner J.E. Evidence-based guidelines for weaning and discontinuing ventilatory support: a collective task force facilitated by the American College of Chest Physicians; the American Association for Respiratory Care; and the American College of Critical Care Medicine. Chest. 2001;120(6 Suppl):375S–395S. doi: 10.1378/chest.120.6_suppl.375s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boles J.-.M., Bion J., Connors A., Herridge M., Marsh B., Melot C. Weaning from mechanical ventilation. Eur Respir J. 2007;29(5):1033–1056. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00010206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yeung E., Hopkins P., Auzinger G., Fan K. Challenges of tracheostomy in COVID-19 patients in a tertiary centre in inner city London. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2020.08.007. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Breik O., Nankivell P., Sharma N., Bangash M.N., Dawson C., Idle M. Safety and 30-day outcomes of tracheostomy for COVID-19: a prospective observational cohort study. Br J Anaesth. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2020.08.023. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schmidt G.A., Girard T.D., Kress J.P., Morris P.E., Ouellette D.R., Alhazzani W. Liberation from mechanical ventilation in critically Ill adults: executive summary of an official American College of Chest Physicians/American Thoracic Society Clinical Practice Guideline. Chest. 2017;151(1):160–165. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2016.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heffner J.E. The role of tracheotomy in weaning. Chest. 2001;120(6):477–481. doi: 10.1378/chest.120.6_suppl.477s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Young D., Harrison D.A., Cuthbertson B.H., Rowan K. Effect of early vs late tracheostomy placement on survival in patients receiving mechanical ventilation: the TracMan randomized trial. JAMA. 2013;309(20):2121–2129. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.5154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rumbak M.J., Newton M., Truncale T., Schwartz S.W., Adams J.W., Hazard P.B. A prospective, randomized, study comparing early percutaneous dilational tracheotomy to prolonged translaryngeal intubation (delayed tracheotomy) in critically ill medical patients. Crit Care Med. 2004;32(8):1689–1694. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000134835.05161.b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Terragni P.P., Antonelli M., Fumagalli R., Faggiano C., Berardino M., Pallavicini F.B. Early vs late tracheotomy for prevention of pneumonia in mechanically ventilated adult ICU patients: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2010;303(15):1483–1489. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trouillet J.L., Luyt C.E., Guiguet M., Ouattara A., Vaissier E., Makri R. Early percutaneous tracheotomy versus prolonged intubation of mechanically ventilated patients after cardiac surgery: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154(6):373–383. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-154-6-201103150-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hosokawa K., Nishimura M., Egi M., Vincent J.L. Timing of tracheotomy in ICU patients: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Crit Care. 2015;19:424. doi: 10.1186/s13054-015-1138-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Volo T., Stritoni P., Battel I., Zennaro B., Lazzari F., Bellin M. Elective tracheostomy during COVID-19 outbreak: to whom, when, how? Early experience from Venice, Italy. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s00405-020-06190-6. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miles B.A., Schiff B., Ganly I., Ow T., Cohen E., Genden E. Tracheostomy during SARS-CoV-2 pandemic: recommendations from the New York head and neck society. Head Neck. 2020;42(6):1282–1290. doi: 10.1002/hed.26166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chao T.N., Harbison S.P., Braslow B.M., Hutchinson C.T., Rajasekaran K., Go B.C. Outcomes after tracheostomy in COVID-19 patients. Ann Surg. 2020;272(3):181–186. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000004166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zou L., Ruan F., Huang M., Liang L., Huang H., Hong Z. SARS-CoV-2 viral load in upper respiratory specimens of infected patients. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(12):1177–1179. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2001737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chiang S.S., Aboutanos M.B., Jawa R.S., Kaul S.K., Houng A.P.-.H., Dicker R.A. Controversies in tracheostomy for patients with COVID-19: the when, where, and how. Respir Care. 2020 doi: 10.4187/respcare.08100. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lamb C.R., Desai N.R., Angel L., Chaddha U., Sachdeva A., Sethi S. Use of Tracheostomy During the COVID-19 Pandemic: American College of Chest Physicians/American Association for Bronchology and Interventional Pulmonology/Association of Interventional Pulmonology Program Directors Expert Panel Report. Chest. 2020;58(4):1499–1514. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.05.571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Long S.M., Chern A., Feit N.Z., Chung S., Ramaswamy A.T., Li C. Percutaneous and open tracheostomy in patients with COVID-19: comparison and outcomes of an institutional series in New York City. Ann Surg. 2020 doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000004428. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goto Y., Yamamoto T., Ozaki M. Aerosol shield and tent for health-care workers’ protection during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Acute Med Surg. 2020;7(1):e550. doi: 10.1002/ams2.550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]