Abstract

Research in bioelectronics is highly interdisciplinary, with many new developments being based on techniques from across the physical and life sciences. Advances in our understanding of the fundamental chemistry underlying the materials used in bioelectronic applications have been a crucial component of many recent discoveries. In this Review, we highlight ways in which a chemistry-oriented perspective may facilitate novel and deep insights into both the fundamental scientific understanding and the design of materials, which can in turn tune the functionality and biocompatibility of bioelectronic devices. We provide an in-depth examination of several developments in the field, organized by the chemical properties of the materials. We conclude by surveying how some of the latest major topics of chemical research may be further integrated with bioelectronics.

Keywords: Bioelectronics, Biointerfaces, Biophysical chemistry, Electrochemistry, Photoelectrochemistry, Synthetic chemistry, Surface chemistry

1. Introduction

Blurring the boundaries between biotic and abiotic systems, bioelectronics is catalyzing profound progress in diagnoses, therapy, prosthetics, as well as facilitating a deeper understanding of physiological processes. New directions and activities are emerging in the bioelectronics community, which signify that this is an active, exciting field with numerous unexplored questions. Some of the recent developments include advanced materials synthesis,1, 2 closed-loop neural3, 4 and cardiac5–8 interfaces, 3D seamless integration of chronic bio-interfaces,9–12 in vivo real-time biosensing,11–16 therapeutics for restoring lost neural functions and reversing neurodegenerative disorders,17–21 etc.

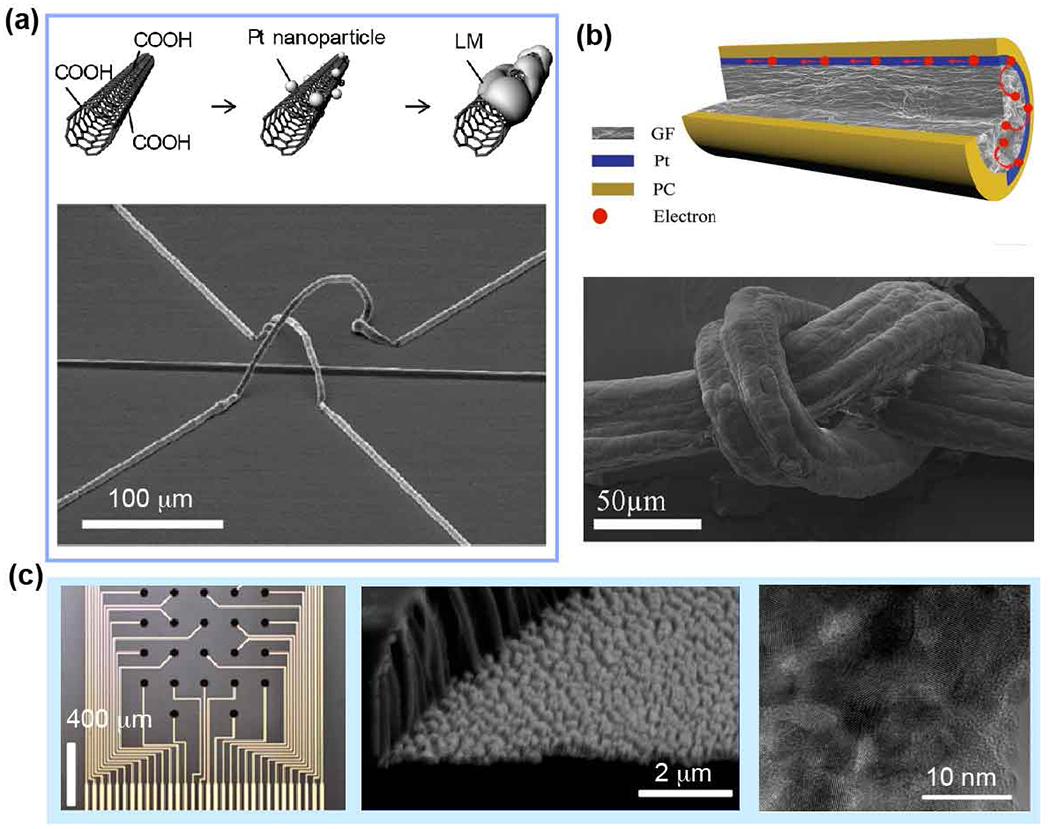

Generally, the validation and optimization of material and bioelectronics devices are heavily focused on engineering and functional considerations. Electrical circuits of various scales and geometries have been designed and manufactured to interrogate bioelectrical phenomena with high fidelity and sensitivity over a wide range of spatial scales.22 At the small end, there is the nanoscale subcellular level, where relevant devices include single-channel patch-clamp and nanoscale field effect transistors. Individual cells and colonies exist on the micron to millimetre scale, where electrical monitoring is typically performed with whole-cell patch-clamp or extracellular electrodes. At the mesoscale tissue-level, microelectrode arrays and mesh electrodes are the most widely used tools for monitoring. To obtain tissue monitoring with fine spatial resolution, the integration of hundreds of electrodes in parallel arrays have been developed for simultaneous signal collection. Furthermore, more functionalities, such as drug delivery, optogenetics, MRI or acoustic imaging, and wireless signal transductions, have been factored and assembled into integrated probes intended for more sophisticated investigations of biological activities using integrated fabrication and engineering techniques.23–26

While the engineering aspects of bioelectronics are extensively discussed elsewhere,27–32 the coverage of chemistry-specific developments in the literature has been comparatively sparse. Despite this, they have aided in creating a new functional material toolkit, in tailoring traditional materials to achieve long-lasting functioning, and in improving probe efficacy and functionality. In this review (Fig. 1), fundamental synthetic chemistry, surface chemistry, electrochemistry, and biophysical chemistry in bioelectronics are discussed first. Next, we summarize new chemical advances that are essential for bioelectronics performance under each category of material (i.e., inorganic or organic semiconductors or conductors, Table 1). These processes play fundamental and indispensable roles to advance the field as they produce new material components, optimize cost-efficient production, promote biocompatibility and long-term stability, improve electrochemical and biophysical performance, and help reveal new biophysical mechanisms and functionalities at biointerfaces. At the end of the review, we discuss new chemistry opportunities for future bioelectronics.

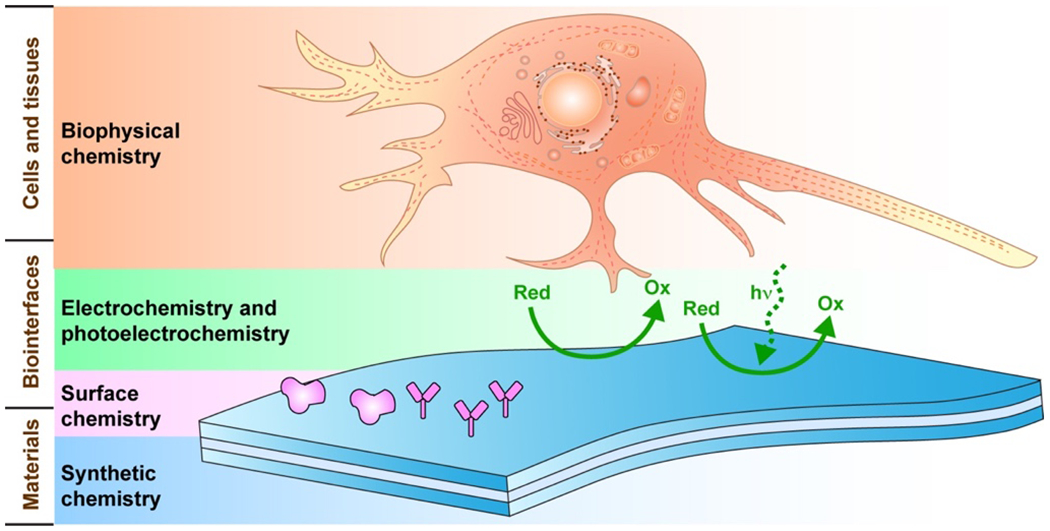

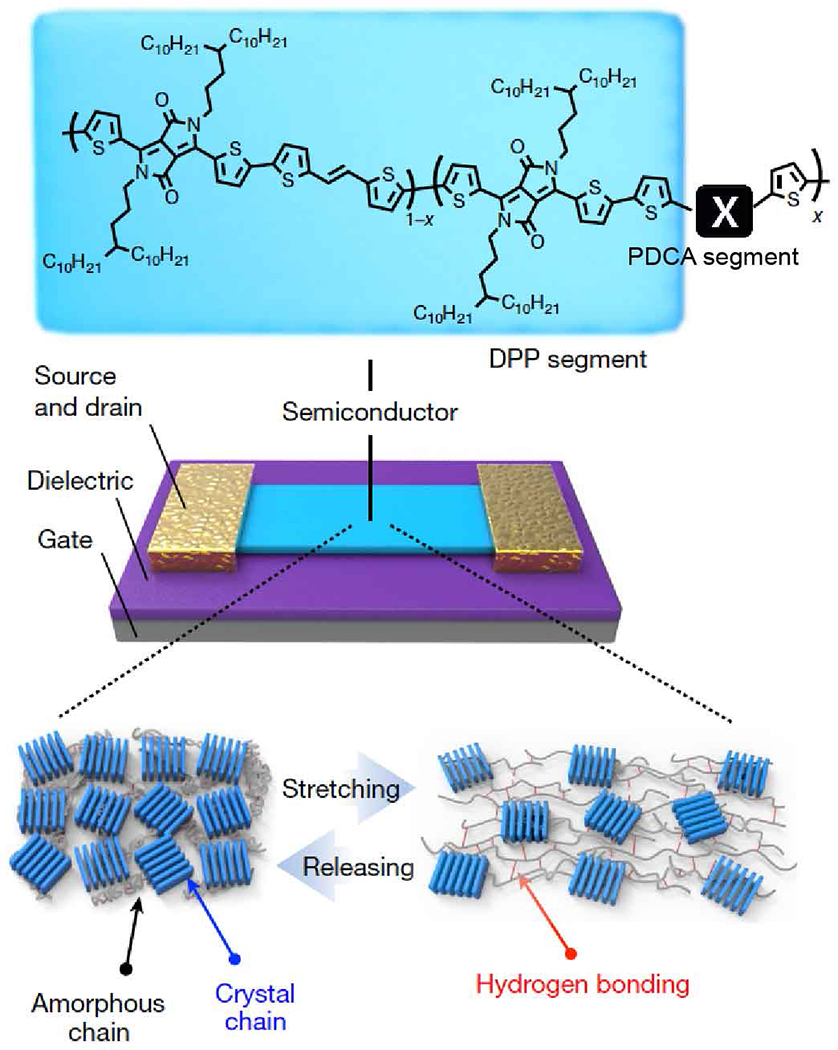

Figure 1.

Chemistry aspects of bioelectronics.

Table 1.

Summary of advantages, disadvantages and example applications of the material groups used for fabrication of bioelectronics devices.

| Advantages | Disadvantages | Application Examples | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inorganic semiconductors | - Established industrial processing - Colloidal structures can be synthesized - Mostly crystalline material - Available surface modification methods - Tunable electrical and optical properties |

- Larger material rigidity - Mechanical mismatch at the biointerfaces - Some materials are highly cytotoxic |

- Resorbable devices134, 157, 160 - Intracellular stimulation38, 67, 129 - Intracellular recording43, 175 - Membrane voltage sensor225 |

| Organic semiconductors | - Solution processable - Flexible and can be intrinsically stretchable - Available surface and bulk modification methods - Tunable electrical and optical properties - Generally low cytotoxicity |

- Lower carrier mobility - Stability in air and in vivo may be poor - May have low crystallinity |

- Stretchable sensors273 - Bioelectronic sensing291, 294 - Optical modulation308, 317 |

| Inorganic conductors | - Established fabrication methods - Good stability - Colloidal structures can be synthesized - Mostly crystalline material - Available surface modification methods - Excellent and stable electrical conductivity - Generally low cytotoxicity |

- Larger material rigidity - Mechanical mismatch at the biointerfaces |

- Recording microelectrodes336, 342, 352, 353, 358, 362 - Intracellular electrochemical detection405, 407 - Wearable electronics404, 427 - In vivo monitoring16 |

| Organic conductors | - Solution processable - Suitable for additive manufacturing (e.g., inkjet printing, 3D printing) - Flexible and can be intrinsically stretchable - Can have high water content - Available surface and bulk modification methods - Tunable electrical conductivity - Generally low cytotoxicity |

- Low chemical stability - May need to manage the conductive phases within the material - May have low crystallinity |

- Stretchable electronics465 - In vivo recording469 - Transparent electronics478 - Chemical assembly in living cells494 |

2. Fundamentals at biointerfaces

In this section, we want to accustom the reader to the fundamentals of working with junctions between the various materials and biological structures, which are referred to as biointerfaces. First, we discuss the size and time scale of the formation of interfaces and how they affect our choice of materials. We follow with a discussion on the basic biophysical principles behind the transduction of biological signals. Finally, we describe the concepts of mechanical matching between natural and artificial systems and the importance of their biochemical stability.

2.1. Size scales of bioelectronics

Biointerfaces can be formed at different length scales depending on the relevant biological question and application, ranging from large-area non-specific modulation to subcellular sensing (Fig. 2a). The following discussion provides not only a description of biointerface design but also a historical perspective on the field of bioelectronics. Relatively large, noninvasive electrodes were developed first and remain widely used today. For recording, those applications are mainly electroencephalography (EEG) for recording brain activity through the scalp, electrocardiography (ECG) for recoding of cardiac activity, and electromyography (EMG) for investigation of skeletal muscles. Similarly, large-area stimulations are routinely used in emergency cardiac arrest defibrillation, in physical therapy for electrical muscle stimulations, and to effectively treat some mental illnesses through electroconvulsive therapy.33 By definition, large-area techniques have limited resolution and suboptimal efficiency due to making indirect contact and being placed far from the tissue of interest. The bioelectrical effects are averaged over a large area and it is therefore difficult to disentangle the variety of chemical interactions at this scale.

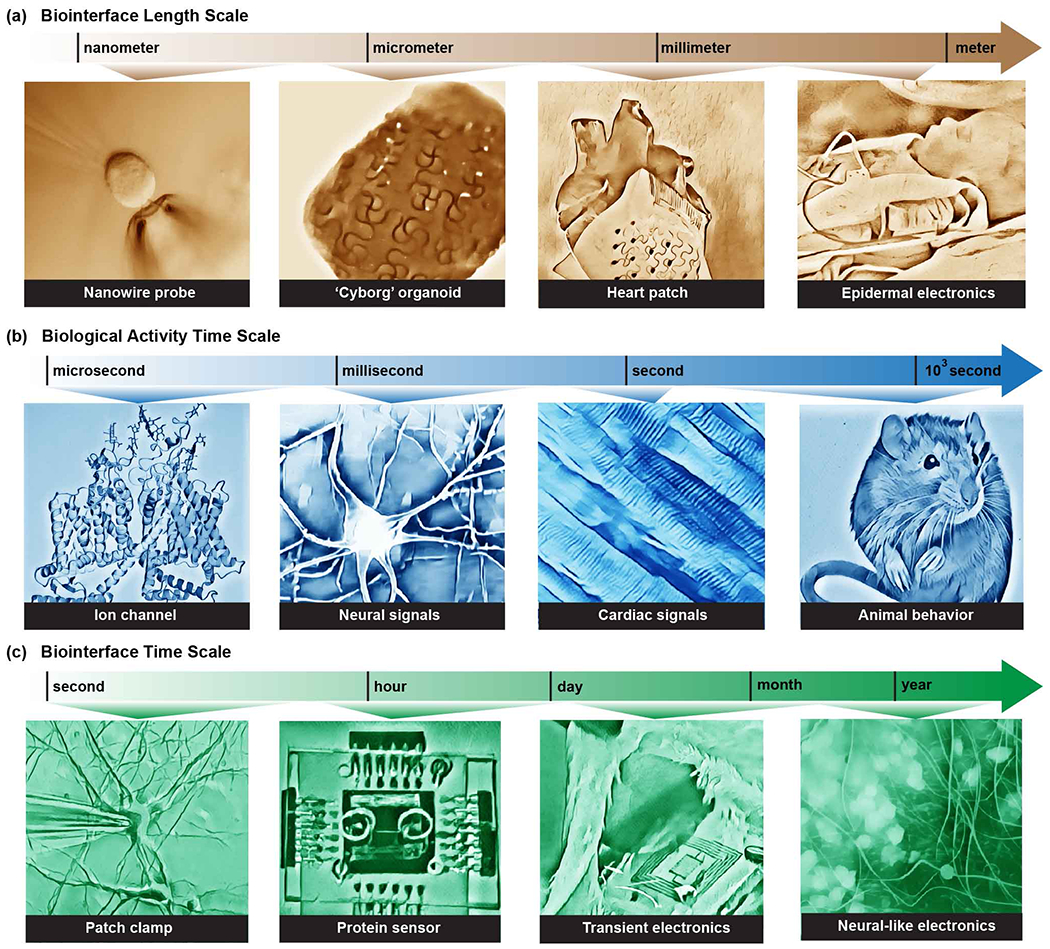

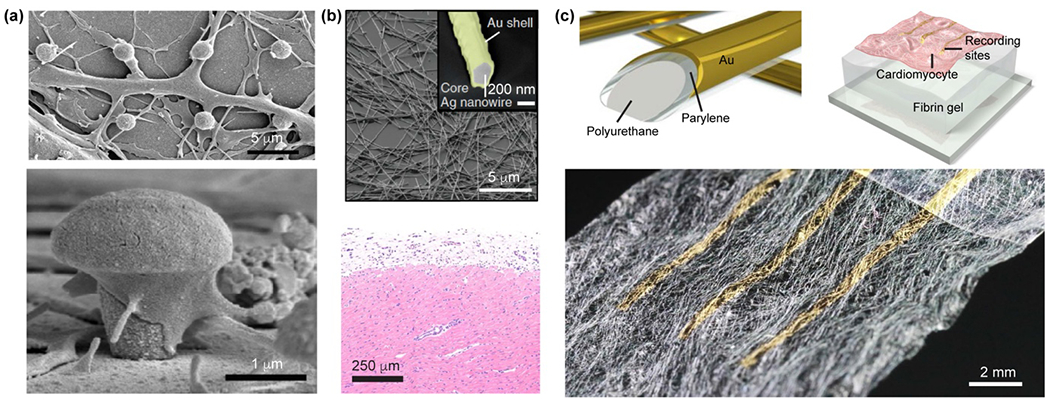

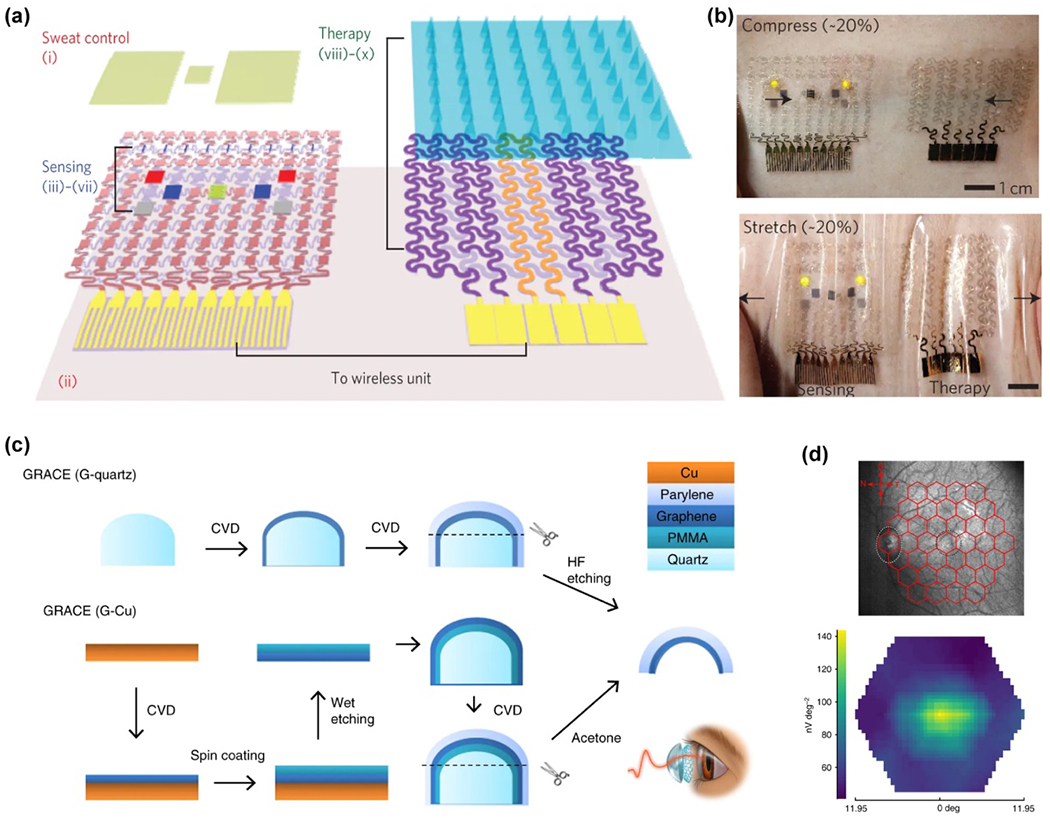

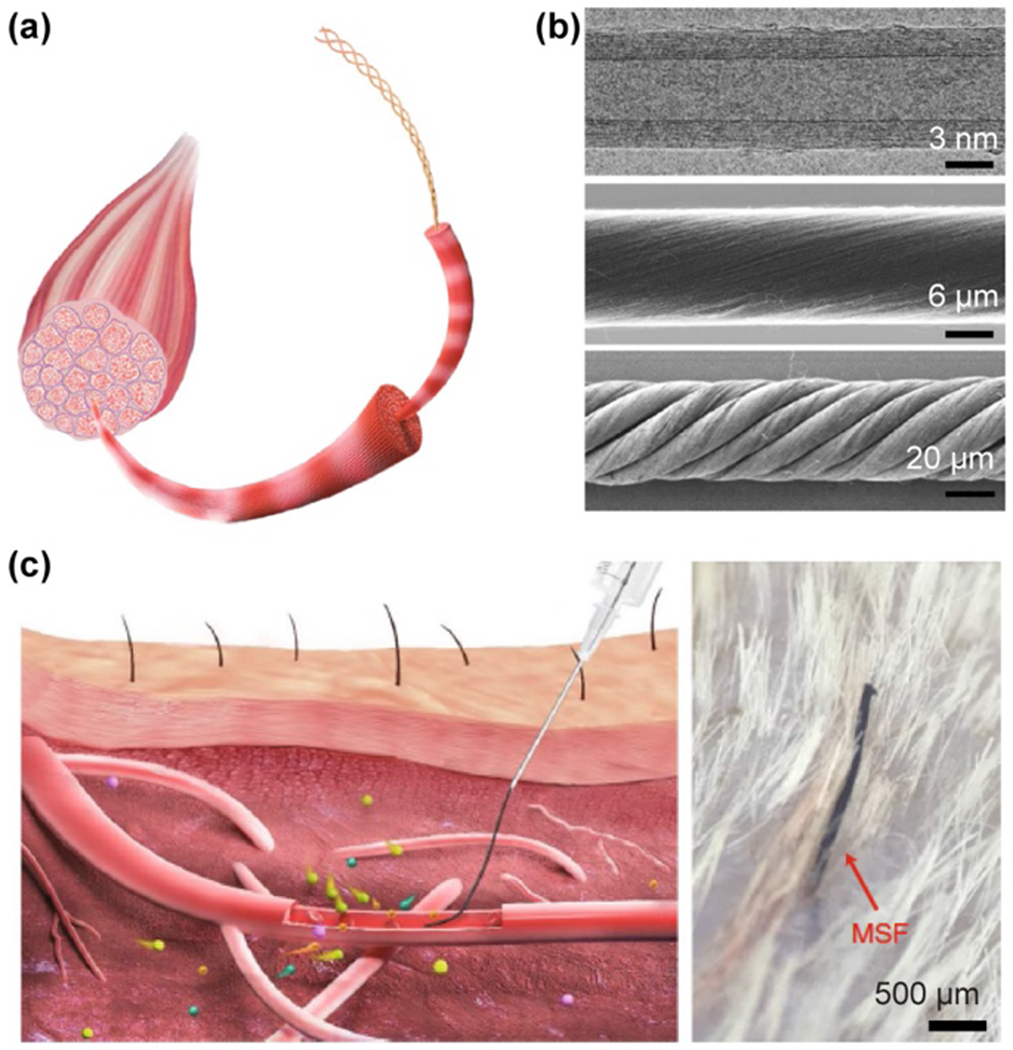

Figure 2.

Bioelectronics and bioelectrical studies span a range of length and time scales. Awareness of chemistry and physics at all applicable levels is necessary to devise appropriate synthetic and analytical methods for the study of biointerfaces.

Progress in materials research brought the possibility of the creation of probes with higher resolution placed closer to the active cells, which facilitated the development of smaller and less invasive devices. The first step was the development of direct biointerfaces with a single organ. These efforts brought us artificial pacemakers, cochlear implants, and deep-brain stimulation probes, which improved survival and quality of life for millions of people. However, the realization of challenging goals such as visual prosthetics or brain-machine communication requires single-cell resolution. Traditional electronics face certain key limitations in such applications. Namely, they possess undesirable mechanical properties, limited biocompatibility, and low interface resolution.

The advent of modern micro- and nanotechnology opened the next frontier in bioelectronics2, 11, 12, 23, 29, 32, 34–40. Probes became smaller and more adaptable, improving the biocompatibility of devices. Micron-sized devices allowed for measurement of local electric potentials deep inside tissues and interfacing with small groups of cells, bringing a whole new insight into the study of cell physiology. On this scale, substantial chemical interactions between the materials and the tissues, such as adhesive forces, have to be taken into account. Current state-of-the-art devices are capable of forming exact single-cell extracellular41 and intracellular42, 43 interfaces. Hopefully, further development in the field will produce methods for single organelle modulation or even studies on specific cell structures such as microfilaments or ion channels. Such measurements will become highly local and allow the study of heterogeneity44 and non-equilibrium processes in living cells. On the lowest scale, chemical and mechanical energy terms become approximately equal in magnitude,45 which will without doubt reveal the presence of new fundamental processes.

With increased spatial resolution comes decreased signal throughput through the biointerface. While large-area recordings give only average readings of electrical activity, such recordings are generally more useful for practical applications. Signals from single cells are usually not representative of the entire tissue and can carry significant noise. Therefore, another challenge that comes with utilizing microscale biointerfaces is achieving high parallelization of modulation and recording. For this purpose, massive amounts of bioelectronic components have to be fabricated or assembled. Recently, significant effort has been put into clinical translation of machine-brain interface technologies by Neuralink. Recent reports demonstrate simultaneous recording from 1020 electrodes.46 While this number is ten-fold higher than those of classic microelectrode arrays (e.g., Utah or Michigan probes),47–52 it is still far from that achieved by biological interfaces. For example, human auditory nerves are made of some 30,000 myelinated neuron fibers53 and optical nerves of more than a million.54 The number of neuronal connections necessary to establish a high-fidelity computer-brain interface is still a matter of debate. However, with the first devices entering clinical trials,55, 56 we should expect a better quantitative assessment of these technologies over the next few decades. It can be envisioned that new materials in a form of massively self-assembled neuro-mimetic fibrils will one day match the parallelization of information transfer observed in nature. A recent report showing bundles of microwires used for neuronal recording represents a promising early step in this direction.57 It is therefore important to study nanoscale self-assembly processes, dynamic combinatorial libraries and other types of parallel chemistries for the synthesis of future bioelectronic devices.

2.2. Time scales of bioelectronics

The relevant time scales in the bioelectronics can be seen from two orthogonal perspectives. One describes the time scale over which biological signals are generated (Fig 2b), and the other is the duration of the biointerface, that is, the time that the device and the biological system spend in contact. (Fig 2c). The timing of recording and stimulation with respect to the biological events will be discussed first. For interfacing with highly active cells such as neurons or cardiac muscles, which can fire an action potential on the timescale of milliseconds, a high frequency response is required from the device. For investigations of even more transient biological events such as the action of molecular motors or activity of single ion channels, even higher temporal resolution on the timescale of nano- to microseconds is required. The timing of the target process therefore determines the required kinetics of the recording or stimulation. For example, for studies of transient states, using diffusion-limited processes would be unwise. Conversely, devices meant to sense or stimulate slower physiological processes such as bone regeneration58 require less temporal resolution but carry with them a different set of considerations. In this case, interfacial chemistry plays an important role as interactions such as adhesion have a significant effect on the stability of an interface as well as any immune response it can elicit. Likewise, devices that can potentially impact mechanotransduction or chemical transduction must consider the time scale of these processes, where signals are delivered and processed with significant delay, on the order of minutes to hours. Understanding the required stimulation or response frequency is thus a critical factor in matching the design of devices with their specific applications.

The other independent time scale is the period over which we expect our biointerface to be active. The interfacing time scale can range from extremely transient experiments to permanent implantation for clinical applications. Biointerfaces used in studies of individual physiological processes can be relatively short-lived. They are used to study single physiological interactions and disposed of soon after. As such, these types of experiments do not require extensive studies of stability and biocompatibility. Maintaining stable biointerfaces becomes a concern for experiments with tissues or cell cultures. In this case, devices need to maintain their integrity and it becomes important to evaluate additional interactions in the biointerface beyond the designated purpose of the device. If for example, the products of the device decomposition lead to uncontrolled proliferation of cells or increased cytotoxicity, such interactions cannot be ignored. It is therefore critical to take into account the chemical composition of such devices as well as the reactivity of their constituents. For applications requiring implantations of the device into an organism, not only does device stability have to be higher, but additional considerations have to account for the immune system response to the presence of a foreign body. The origin and methods of mitigation of immune response to the biointerface will be discussed in the following section. Excellent stability and biocompatibility are required for a long-term integration of bioelectronics with a host body. An important example of an application that requires long-term integration is the formation of chronic brain interfaces. The delicate nature of brain tissue makes it not only more sensitive to invasive probes, but due to the brain’s limited regeneration ability, replacement of used bioelectronics devices with new ones is not a feasible solution. Each removal and insertion of probes causes irreversible trauma that can lead to fatal accumulation of damages. Therefore, clinical applications of the machine-brain interface demand stable, long-term biointerfaces.

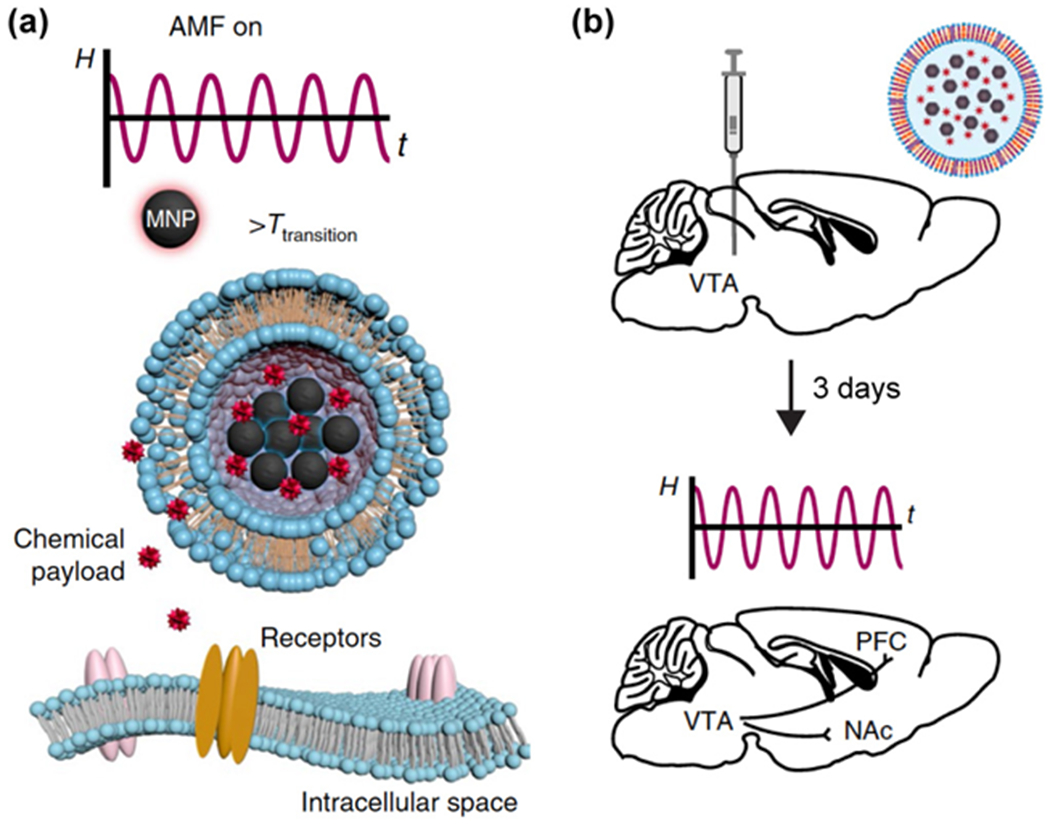

For long-term integration of bioelectronics, additional attention has to be paid to all the secondary electronics necessary for their operation. Bench-top controllers, transducers, and power sources can be used in short-term laboratory experiments without concern. The case is significantly different for implantable bioelectronics, where electrodes tethered to extensive external instrumentation limits the mobility of host organisms and makes such a solution impractical. Hence, lightweight and, ideally, remote-controlled recording and modulation devices represent an important design principle that requires significant thought. The essential issue is the integration of bioelectronic devices with proper microscale power supplies. Recent developments point to devices to which power can be delivered remotely, e.g., through magnetic resonant coupling.59 Another front is led by the freestanding devices that lack traditional electric circuits, but can locally stimulate tissues through magnetothermal,23, 60 chemomagnetic,61 photoelectrochemical,62, 63 photothermal,64–67 and photoacoustic38, 68 effects that are initiated with remotely delivered physical stimuli. Future research in applied bioelectronics will no doubt veer towards the development of integrated, wireless devices for the ultimate goal of seamless, inconvenience-free bionic integration.

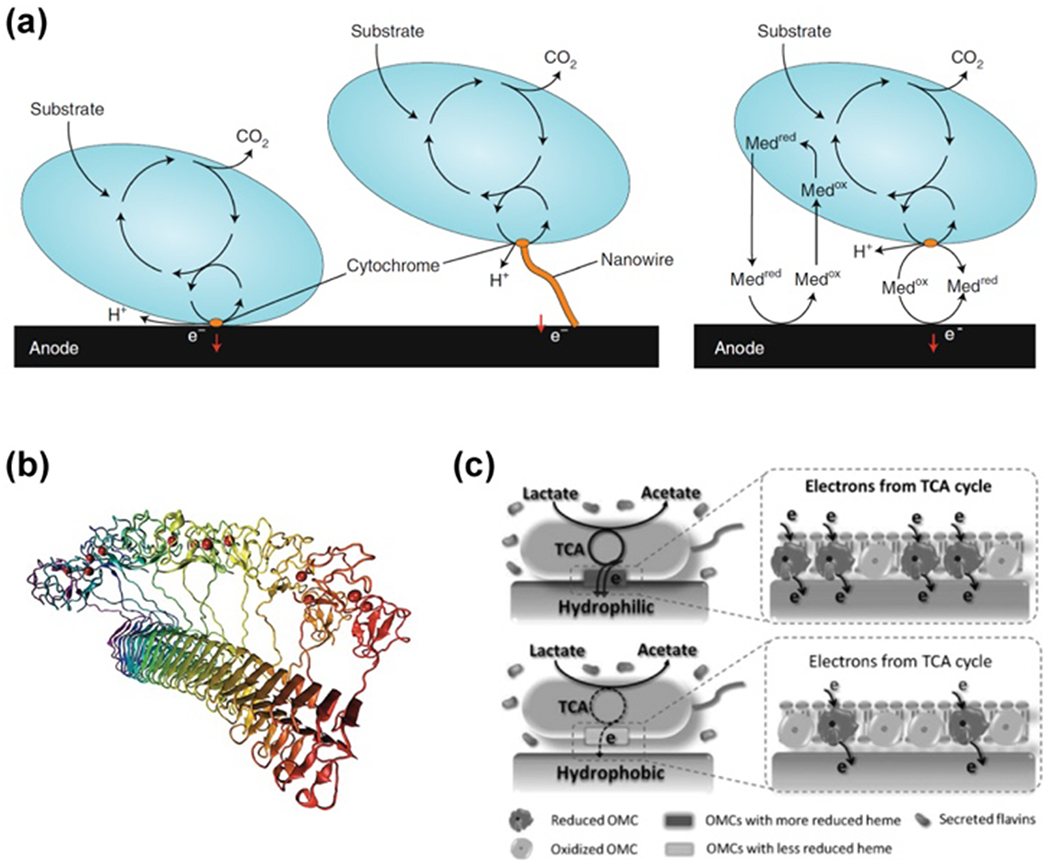

2.3. Signal transductions

Biological systems fundamentally differ from standard electronics by their mechanisms of signal generation and transmission. In conventional conductors such as metals, the majority of electric charge is carried directly by electrons. In biological systems, rich in water, ions, and organic matter, electric current is carried mostly by ionic fluxes. These two modes of conduction are, in principle, very dissimilar, which requires a specific interface in which signals can be transduced (Fig. 3).

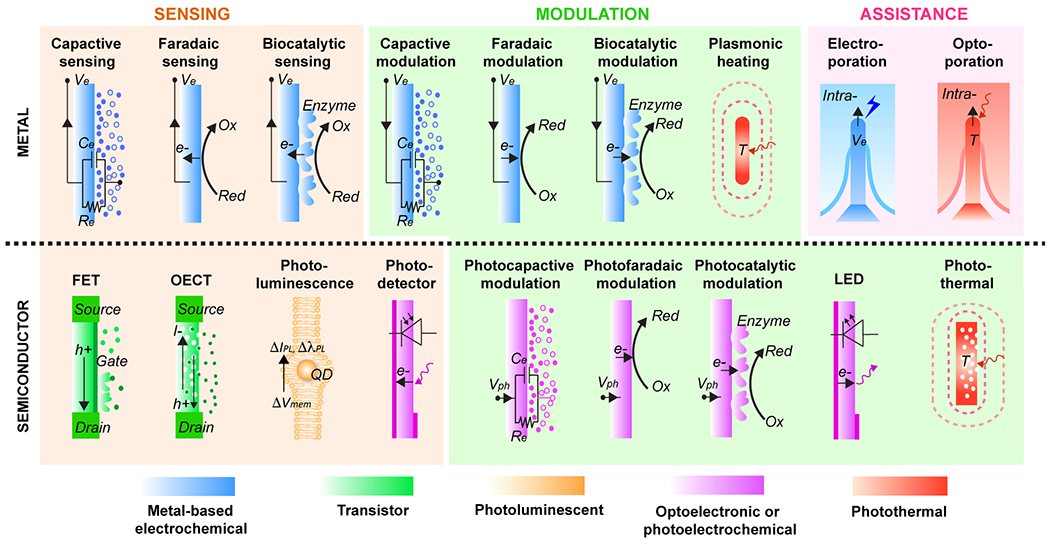

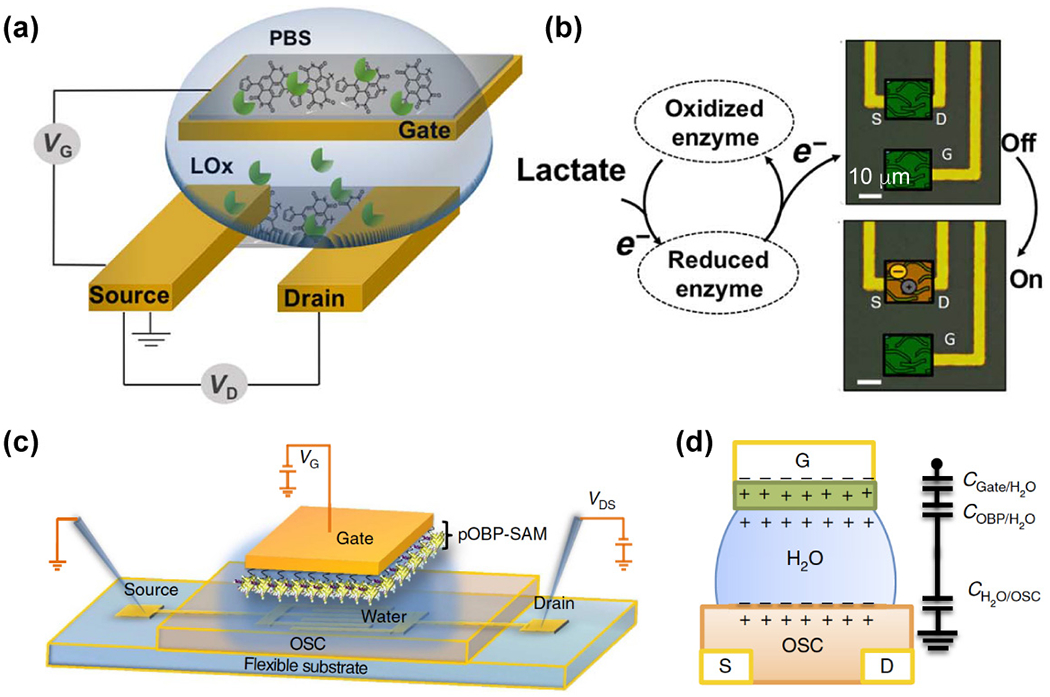

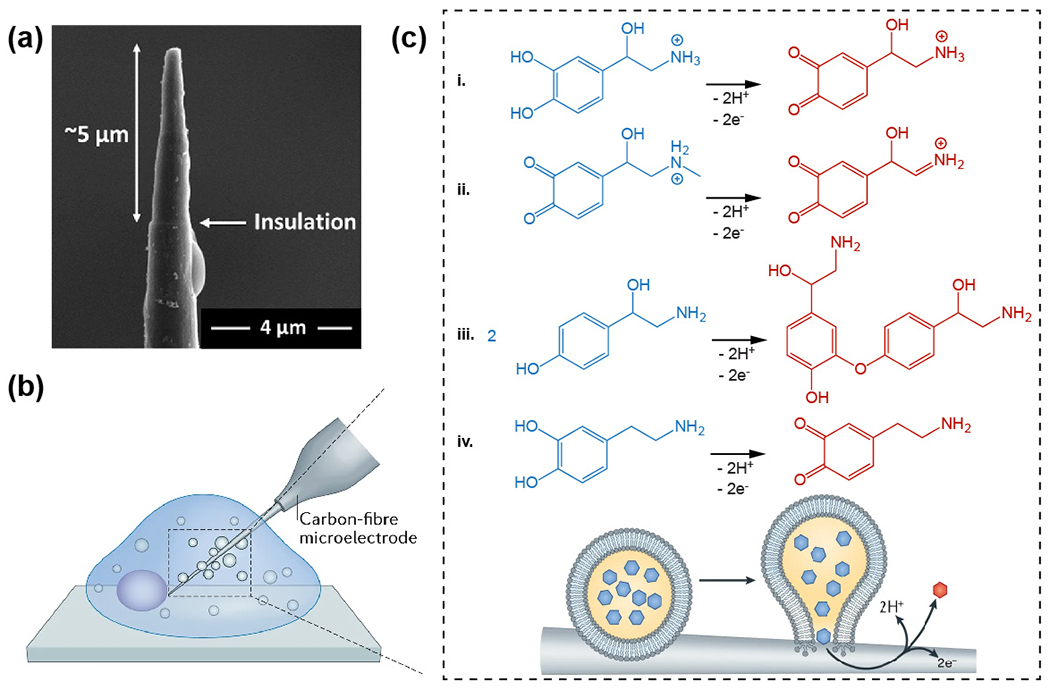

Figure 3.

Signal transduction mechanisms in bioelectrical interfaces can vary depending on the material design and chemistry. Top: Metal-based electrodes can be used for recording or injection of capacitive, faradaic, and biocatalytic currents. Free-standing metallic nanostructures allow used for plasmonic heating. Additionally, metallic structures can be used to facilitate interface interrogation penetrating cellular membranes using electroporation and optoporation. Bottom: Highly sensitive recording of bioelectric signals using field-effect transistor (FET) and organic electrochemical transistors (OECT). Readout of optical signals using photoluminescent materials and photodetectors. Free-standing nanoscale semiconductors allow for wireless injection of currents through photocapacitive, photofaradaic and photocatalytic effects. Micro light-emitting diodes (LED) can be used to deliver optical signals. Semiconductors without electric and radiative energy decay pathways can generate photothermal heating.

2.3.1. Bioelectricity in cells and tissues

Electrically active cells communicate via spikes of ion fluxes caused by a sudden release of ions, known better as action potentials. The potential difference between insides of cells and their extracellular environment (usually negative) is maintained by active transport and imbalance in the concentration of ions, typically K+ and Na+. The resting transmembrane potential existing due to this imbalance is classically described using the Goldman-Hodgkin-Katz (GHK) equation:

| Equation (1) |

where Vrest is the resting membrane potential, R is the ideal gas constant, T is the absolute temperature, and F is the Faraday constant. The sums account for permeabilities P and concentrations [M] of monovalent ions on the inside and outside of the membrane.69 The resting membrane potential is the mechanism by which cells store energy used for signaling. When stimulation occurs, passive ion channels open and ions freely flow in and out of the membrane. This ion flux generates electric currents which can create a local potential change in the tissue, effectively meaning this cell is interacting with neighboring cells to cause further signal transduction. A potential generated at point (x,y,z) by moving ions can be derived from Ohm’s law and, treating the ions as pure monopoles, takes the form of:

| Equation (2) |

where Ii is the current from the ith monopole, σ is the conductivity of the medium, and ri is the distance from the monopole to the point (x,y,z).69

The aforementioned model averages molecular interactions and approximates properties of the media and the surrounding tissues. In reality, the environment of biological fluids is highly crowded, and in dense structures, e.g., brain tissue, electrodiffusion is affected by heterogeneities at a molecular level.70 Hence deviations from this classic interpretation can be observed on a subcellular length scale. Such heterogeneities can arise from the extracellular environment and interactions with large proteins and charged species, as well as from uneven spatial distribution of ion channels in the membrane. Therefore, it is paramount that the progress in nanodevices’ research comes together with the development and validation of new theoretical models.70

2.3.2. Electrochemical sensing or modulation processes

The most straightforward electrode-tissue interface utilizes capacitive currents (Fig. 3). A chemically inert electrode can only inject current due to building capacitive charge on its surface due to applied potential. Ions with complementary charges will migrate towards the electrode, creating charge currents, and start building up a layer on the electrode surface called an electrical double layer (EDL). Ionic currents will flow only until the electrode is fully charged. The time constant for EDL formation can be described as:

| Equation (3) |

where Re and Ce are the leakage resistance and capacitance of the electrode, respectively. This simple relation is an essential operational specification of the electrode. It describes its operational limits as well as its bandwidth – the maximum frequency at which signals can be delivered or received. The electrical interaction between the electrode and the membrane can be estimated with a highly simplified model of an equivalent circuit, in which the cell and electrode are treated as potential sources, an interface is modelled as a parallel capacitor and a resistor, and an additional term is added for internal electrode resistance.71 Using this equivalent circuit and Equation 2, we can derive the relation between cell and electrode potentials:

| Equation (4) |

where Ve is the electrode potential, Vcell is the potential at the cell surface, Rint is electrode’s internal resistance, and s is the complex frequency of interacting waveforms. The above equation can be used to qualitatively describe both stimulation and recording. For stimulation, we choose to control electrode potential Ve and interact with the cell. For recording, the cell is firing its active potential Vcell, and we measure readings received on the electrode.

By analyzing Equation 4, fundamental qualities of electrode-cell biointerfaces can be derived. First, electrical interaction, as parameterized by the potential, is inversely proportional to the distance r between the electrode and cell membrane. Hence the closer the distance between the electrode and the membrane, the stronger the interaction. Also, for strong interactions, it is recommended to keep leakage resistance (Re) low and electrode capacitance (Ce) high. Resistance of interconnections plays a role in determining the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of the biointerface. For higher currents, Rint has to be kept low, but for good SNR, it has to be kept high. For designs in which the electrode is bifunctional and used for recording and stimulation, a compromise has to be made.

Purely capacitive electrodes rely only on EDL and have a limited range of operation. Stimulation with higher potentials can be accomplished using electrodes injecting Faradaic currents (Fig. 3). Such an electrode is chemically active and introduces new ions due to electrochemical reduction or oxidation occurring on its surface. It has been shown that highly catalytic electrodes are capable of stimulating with strong potentials.72 The drawback of using a chemically active electrode is its degradation over time. One possible way to prevent extensive damage to an electrode injecting Faradaic current is the application of principles used for the fabrication of supercapacitors.73 These principles include the application of nearly completely reversible electrochemical reactions or precise structuring of the electrode on the atomic level, which permit increasing its capacity beyond the limit of traditional materials. Another possible development in this field might be the application of bioelectrocatalysis (Fig. 3), which uses electrode-bound enzymes to generate active species in situ for selective stimulation or process metabolites present in the system to be used for their detection.74, 75 Additionally, although redox signaling is paramount in biological systems,76, 77 it was not thoroughly explored with respect to bioelectronic modulation.

2.3.3. Optoelectronic or photoelectrochemical sensing or modulation processes

Semiconductor-based optoelectronics or photoelectrochemical devices can be used to deliver (e.g., using a light emitting diode [LED] or a photovoltaic device) or read out (e.g., using an in vivo photometer) stimulation signals at the biointerface, when matched with electrical circuits or wireless microcontrollers (Fig. 3).78, 79 To perform single cell studies, we can either use semiconductor structures/devices that are microns or nanometres in size, or use highly localized initial stimuli (e.g., a laser spot) over macroscopic structures/devices.

Many of the devices for such studies are based on diode junctions. In particular, for photoelectrochemical stimulation applications, a photovoltaic mechanism is often adopted.62 A diode device is typically created when hole-rich (p-type) and electron-rich (n-type) semiconductors are placed in contact, causing a shift in their valence and conduction bands near the p-n junction, within a region called the depletion zone. Photoexcitation can promote an electron from the valence to the conduction band, creating an electron-hole pair.38 The electrons and holes then diffuse away from the depletion zone in accordance with their charge, creating a potential difference on different parts of the device that can be used to stimulate cells and tissues similarly to wired electrodes described above.

Depending on the material, photoexcitation can inject capacitive current, Faradaic current, or a combination thereof into the biointerface (Fig. 3). These processes in freestanding structures can be understood within a framework analogous to that of the wired electrode. However, semiconductors are highly sensitive to their environment through the alteration of their surfaces’ electronic structure. Photostimulation and other physical behaviors at the interfaces can be predicted both qualitatively and quantitatively using the concept of band bending. Band bending in semiconductor describes the alteration in native electronic structure due to the material environment, surface modification,80 or the material size and dimensionality.81 Semiconductor physics and electronic processes underlaying their photoactivity require a more thorough discussion, for which we redirect readers to literature specific to semiconductors.32, 38

2.3.4. Photothermal modulation processes

The photothermal effect arises from radiationless energy transfers in photoexcited materials. That is, the emitted energy translates into the kinetic energy of the material or its surroundings, and the temperature increases. In practice, this means that the best candidates for photothermal modulation primary respond to excitation with the generation of phonons or plasmons. In crystalline materials, nonradiative recombination can produce quantized oscillations in the bulk material, known as phonons, which are responsible for photothermal heating in those structures.82 For certain metallic nanomaterials, such as noble metal nanoparticles and carbon nanostructures, light absorption results in oscillations of associated free electrons on the material surface. These oscillations are referred to as surface plasmons, and their production can convert almost all incoming light energy to heat.83, 84 Continuous-wave irradiation of plasmonic materials can therefore create strong temperature gradients (Fig. 3).64

Transduction of thermal signals is another vital aspect of biophysics, yet it has not been studied as extensively as electrical signals. Cell physiology, especially the catabolic process responsible for energy generation, generates multiple intracellular and extracellular thermal gradients.85 Such signals can trigger proliferation and affect other cellular metabolic pathways. It can be deduced from the GHK equation (Eq. 1) that temperature affects membrane potential, and its increase will make it more sensitive to stimulations. Additionally, multiple ion channels have been discovered to be especially receptive to temperature gradients such as thermosensitive potassium channel TREK-1.64 For thermal sensing, purely resistive microelectromechanical devices as well as a range of nanostructures have proven effective. Quantum dots, upconverting nanoparticles, and metal cluster were all applied to create remote luminescent thermometers.86

A closely related phenomenon can be observed when instead of steady irradiation, high-power pulsed lasers are used to illuminate plasmonic nanostructures. A sudden release of energy causes evaporation of solvents around the material surface, forming gas nanocavities which, upon collapsing, release ultrasonic waves traveling through the medium. This phenomenon is referred to in the literature as a photoacoustic effect.65, 68, 87 Although the mechanism of the generation of photoacoustic waves is not fully understood it allowed the development of a variety of imaging and stimulation methods.88, 89 Recently, the photoacoustic effect was used to facilitate entry of recording electrodes into the cells through the local optoporation mechanism in a similar manner to the classical electroporation (Fig. 3), but providing superior process control and cell viability.90 However, potential applications of the photoacoustic effect in bioelectronics remain largely unexplored.

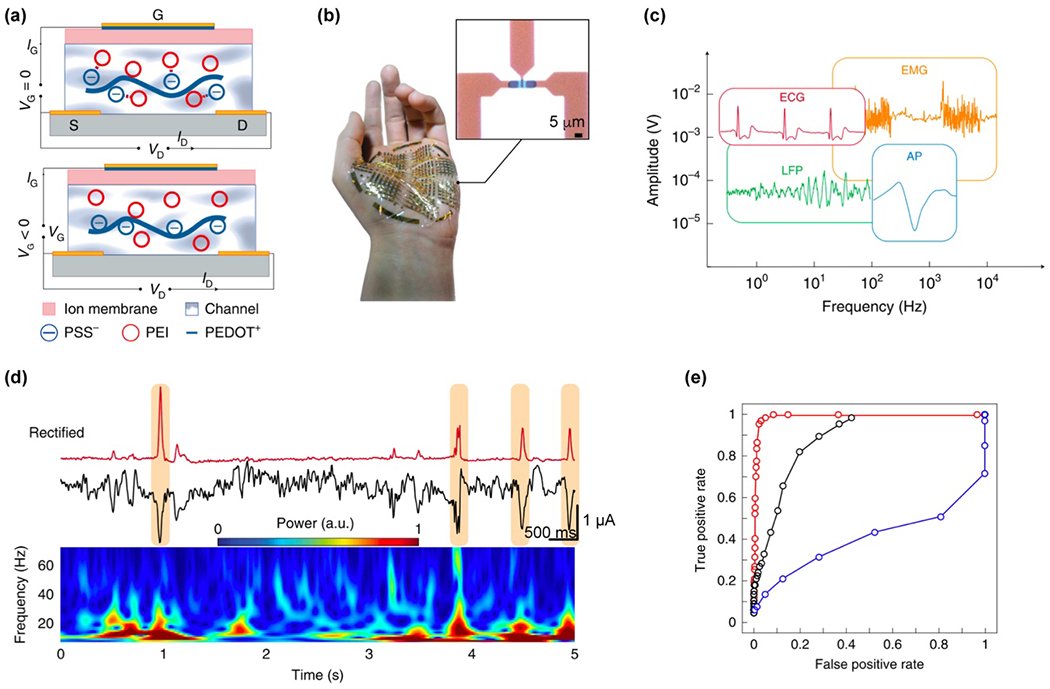

2.3.5. Transistor-based sensing processes

Transistors are some of the most important elements in nearly all modern electronics and bioelectronics. In particular, field-effect transistors (FETs, Fig. 3) are widely used as they have been extensively studied due to their importance in the operation of integrated circuits. In the regular planar configuration, a semiconductor substrate is connected to a source (S), drain (D), and gate (G) electrodes. The gate electrode is separated from the substrate using a dielectric insulator. When a voltage potential is applied between the source and drain electrodes, the current will flow through the semiconductor channel. The current through the semiconductor will be proportional to the potential applied to the gate. Depending on the doping of the semiconductor substrate, a transistor can operate in enhancement or depletion mode. For an ideal transistor in enhancement mode, no current flow will occur at gate potential below the specific threshold and beyond the threshold potential, current will rise linearly until saturation current is reached. The behavior is reversed in a depletion mode transistor. The ratio of current change to the applied potential in a transistor is defined as transconductance gm and can be a direct measure of its sensitivity.

The external connection to the gate is typically omitted for bioelectronic sensing applications, as the gate potential variation is generated directly by the dynamic processes from charged species or cells. Notably, for FET-based detection of binding of unbinding of charged species (such as protein marker), the sensitivity is limited to the characteristic Debye screening length:

| Equation (5) |

Where lb is the Bjerrum length, Σi is the sum of present ion species with concentrations ρi and valence zi. The Debye screening length can be used to approximate sensitivity range and is on the order of <1 nm in concentrated electrolytes.38 Specificity and sensitivity of FETs in bioelectronic situations can be improved by using surface modifications with biomolecules capable of molecular recognition.91 The advantage of FET devices over metal-based capacitive and faradaic electrodes is that device current flows in a closed-circuit, so that the potential issues with the electrode impedance, electrode corrosion or biological invasiveness can be minimized. This also allows FET devices to achieve faster response times92 and lower SNR93 when compared to single terminal electrodes.

The second type of transistor – electrolyte gated transistor – has gained increased popularity in bioelectronics over the recent years due to its high transconductance, biocompatibility, and processing versatility. In this configuration, the semiconducting substrate and gate are replaced with porous structures which can be interpenetrated by ions increasing or decreasing current flow through the channel. The most popular materials for gating channels are made of organic conductors and semiconductors forming a class of organic electrochemical transistors (OECTs, Fig. 3). Transconductance in OECTs can be described using Bernards model94, 95 and the equation:

| Equation (6) |

which accounts for channel geometry: width W, length L, and thickness d; charge carrier mobility μ; capacitance per unit volume of a channel C*; gate voltage VG and specific threshold voltage Vth. Capacitance in organic materials can be widely tuned; therefore, characteristic of OECTs is their exceptionally high transconductance.96 OECTs can be used for ion-selective sensing with the introduction of proper membranes.97 A closely related topic to OECTs is a class of hydrogel-based devices called organic electronic ion pumps (OEIPs) which can be used for ion delivery98–100 and as drug delivery platforms.3, 95, 101 For a detailed discussion on OECTs and OEIPs we direct the readers to recent reviews focusing on these subjects.102, 103

2.3.6. Stimulation with molecular and optical signals

Biological systems utilize a range of small molecules and peptides for intracellular or organism-wide signaling. Bioelectronic devices can be used to deliver signaling molecules and pharmaceuticals directly into tissue, increasing their availability and potency.104 Microfluidic channels present one promising approach to this application. The drawback of this approach is that it requires the integration of secondary elements, such as pressure sources, to function properly. Although some micropumps with low power consumption have been devised,105, 106 there is still much progress to be made in this area. An alternative approach is to design materials that can dispense drugs from inside their structure on-demand such as the aforementioned OEIPs. However, volumetric materials have limited cargo capacity, and molecules are usually delivered through diffusion and positive pressure, which lowers delivery speed and efficiency.

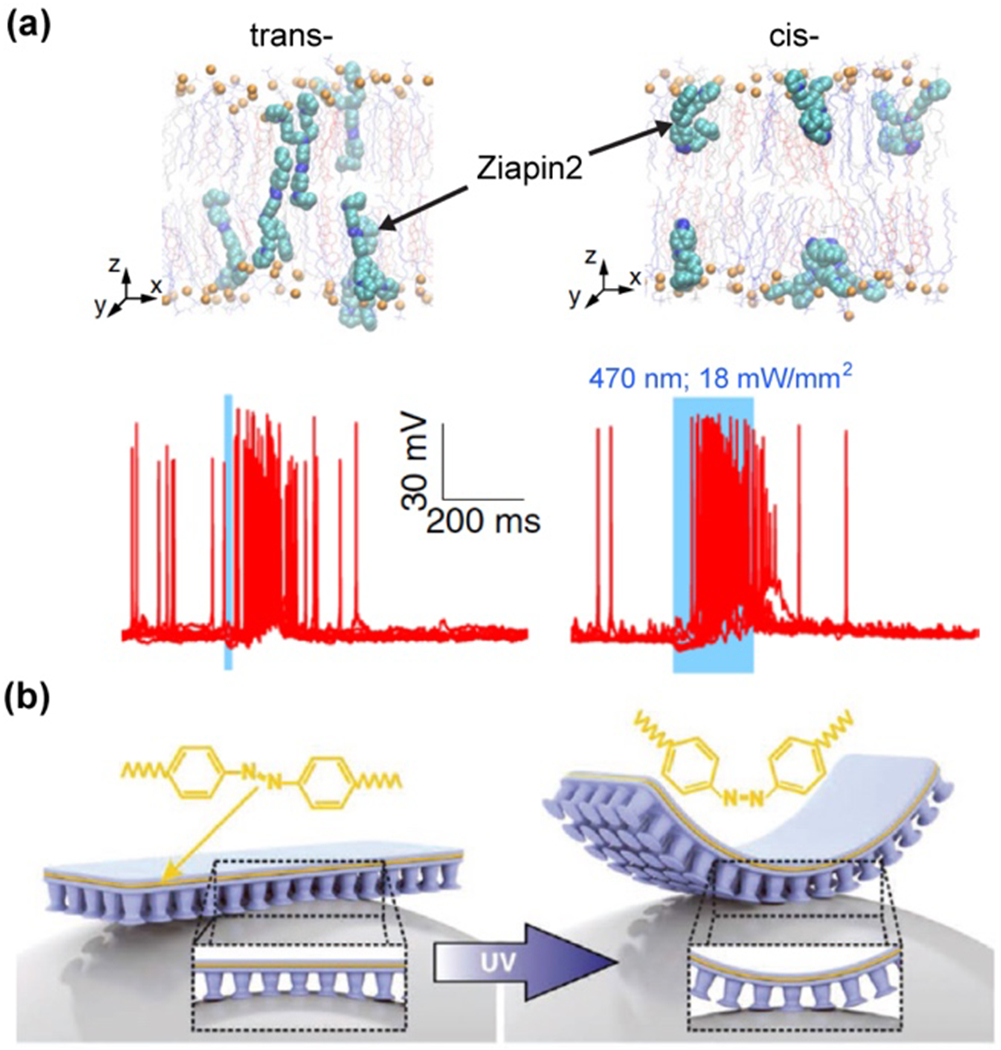

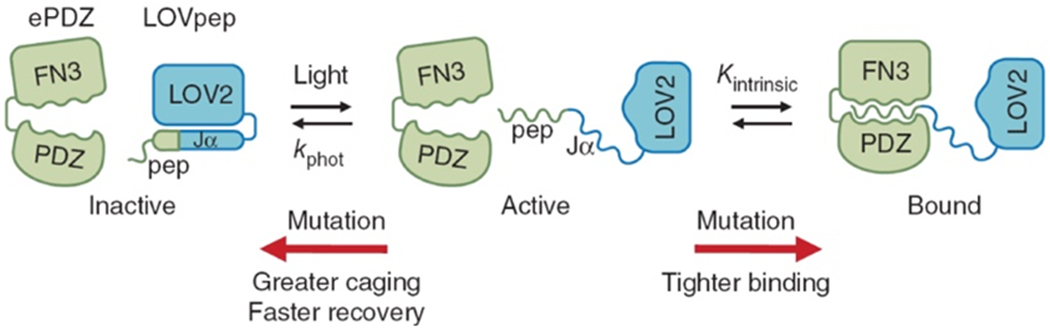

Apart from some small organisms, most cells and tissues cannot be directly stimulated using light. Two approaches exist to make ordinary cells susceptible to optical signals: optogenetics and optopharmacology. Optogenetics relies on genetic modification of target cells to display specially engineered optically responsive ion channels,107 while optopharmacology relies on delivery of photoresponsive drugs which, while inactive in their native form, can be distributed evenly among cells and will become active only upon illumination.108 Both of these approaches, which are discussed further in section 7.2.2, allow for local optical modulation of cellular activity. Delivery of light to the stimulation location can be accomplished using waveguides or microlight sources such as upconverting materials, or micro-LEDs.109 Efficiency of light delivery can be calculated using the equation:

| Equation (7) |

where Ps is the output power of the source, η factors are coupling and scattering efficiency, and Φ is the geometric factor of the light interface.110 The design of materials that can be used as waveguides focuses on maximizing coupling and scattering efficiency. Furthermore, for microlight sources, increasing the light power output without excess resistive heating is a challenge. Additionally, geometric factors can be taken to account, and directional light sources can be devised that focus their emission on the limited angular range and allow for efficient and highly localized stimulation. Because those optical systems require genetic modification or drug delivery for their functioning it is common to integrate them into single optofluidic system.111

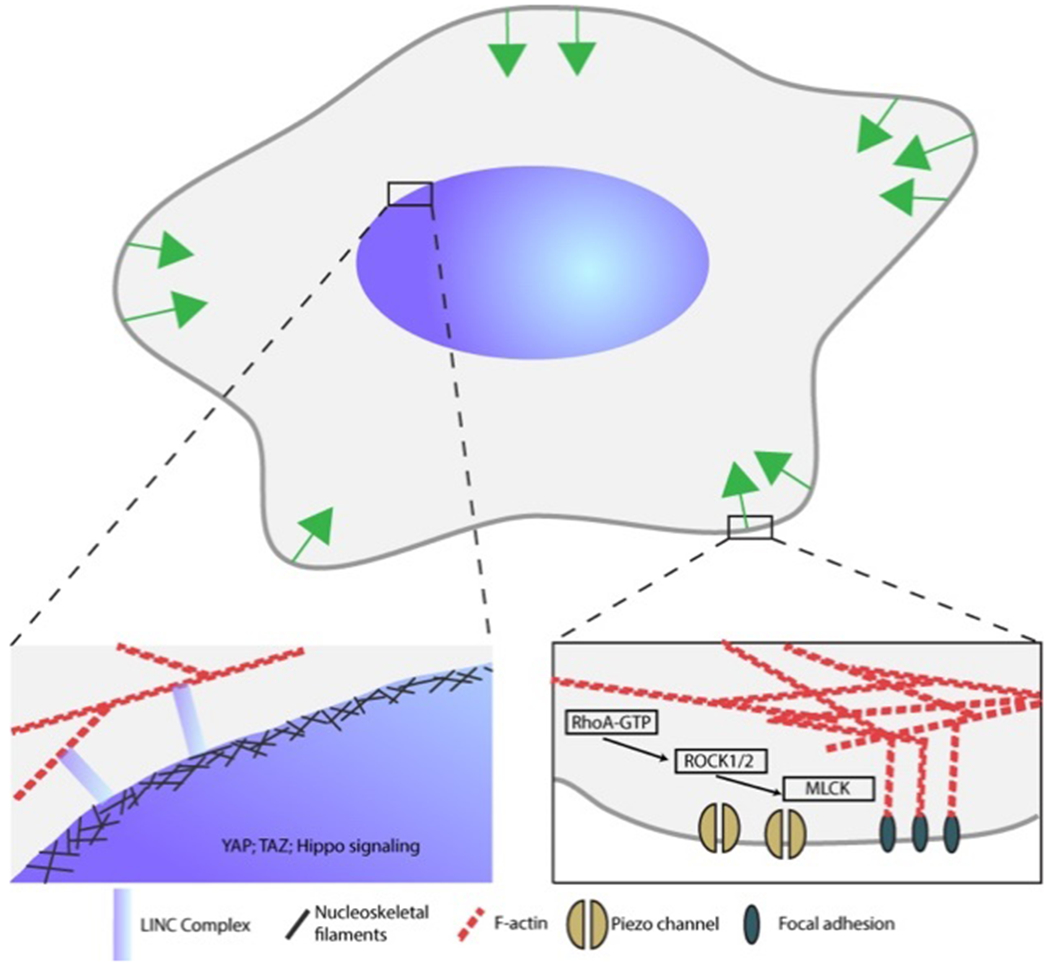

2.3.7. Transduction of mechanical signals

Nearly all biological systems have been observed to be sensitive to mechanical stimulation. Mechanical stimuli can be transduced through surface receptors and mechanosensitive ion channels or else directly detected by the cytoskeleton.112 Mechanotransduction is an important mechanism that can be used for bioelectronics since it can greatly influence cell functions and their ultimate fate.113 For example, mechanical obstacles or stimulation can significantly impair growth and myelination of oligodendrocytes.114 Historically, studies have focused on the impact of bulk mechanical properties of extracellular matrix, namely its stiffness. More recently, the effects of the presence of static curvature115 have also drawn interest. Materials with gradients of mechanostatic interactions, tuneable stiffness, and active curvature actuation on the nanoscale are highly sought after.

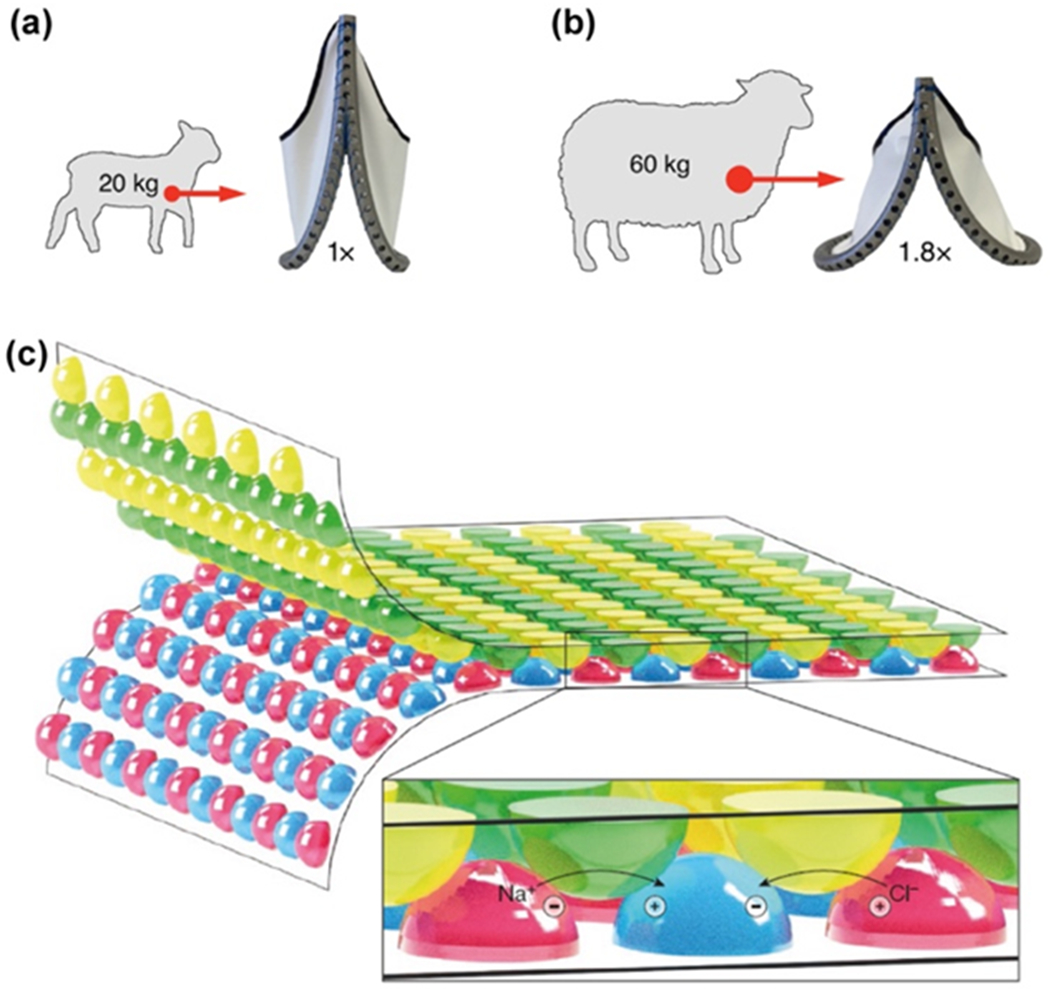

2.4. Mechanical match and mismatch

Biology sets several constraints on the design of bioelectronics, which makes integrating biological and artificial systems especially challenging. One of the most important considerations is the mechanical matching across the interface. The most widely used metric of stiffness is the Young’s modulus, which relates the stress and strain of a linearly elastic material. While cells themselves are in fact viscoelastic, and thus excluded from this definition, the most useful devices for biointerfaces with soft biological tissues have Young’s moduli in the range of 0.1 – 50 kPa, with neural tissue and skeletal muscle targets on the lower and upper end, respectively.116 In contrast, most of the substrates used in traditional electronic devices have Young’s moduli in the range of 100 MPa to 10 GPa. It has been shown that mechanical mismatch can lead to rejection of the interface by causing an inflammatory response in tissues17, 117 or merely being a nuisance for an organism and limiting its motoric activities.118 Other reports show that material stiffness affects the complex behavior of surrounding cells such as differentiation and adhesion.116 As has been discussed in recent specialized reviews on this issue,17, 22 this knowledge is of critical importance to the realization of neural interfaces for computer-brain communication119 and deep brain stimulation for the restoration of motor functions.120 The brain is highly reactive, and even slight insertion trauma caused by stiffness mismatch between the tissue and the probe can cause activation of microglia and macrophages.17 In effect, this acute inflammation can turn into chronic inflammation, which will cause degradation of the interface or the device itself. Rejection of the implant or loss of its integrity renders the device inoperative and would require extraction, treatment of damages, and reinsertion of new probes, complicating the treatment and significantly increasing side-effects. It is therefore critical to achieve mechanical matching in order to form stable biointerfaces.

Multiple solutions for improving mechanical matching have been devised with the most straightforward solution being reduction of dimensionality of materials and reduction of the size of their constituents to the microscale and nanoscale.121 This approach allows for a lower bending stiffness and to realize flexible and stretchable biointerfaces with classic electronic materials such as silicon (Si) and gold (Au).122 While mechanical properties are improved, such materials are still far more rigid than biological tissues and may compromise the stability of a biointerface. The search for materials with intrinsically matching mechanical properties has arrived at organic conductors and semiconductors as suitable candidates, with the highest promise coming from their hydrogel formulations thanks to their high water content, which allows for transfer of ions and dissolved gases. However, significant efforts are still needed to improve the electronic and optoelectronic functions in these organic materials.

Another critical aspect of mechanical matching is planning for the geometry of the interface. Biological materials generally have rough surfaces which leave a gap when put against flat materials, such as thin inorganic layers. Intrinsically rough materials such as nanostructures and carbon-based materials tend to perform better in this area.123 When possible, biocompatible adhesives could be employed to fill the gap.124

An alternative approach is to use hard-soft composites, which may ultimately solve the compromise between the electronic/optoelectronic functions and the mechanical properties needed for future biointerfaces. The hard-soft composites contain hard materials, which bear some useful functionality, and soft matrix materials that can act both to improve the mechanical match and to potentially offer some biological functionality themselves. This allows for a wide variety of hard materials, which include materials such as Si and noble metals that are already ubiquitous in electronics, to be incorporated into biological tissues while attenuating the immune response. By carefully tailoring soft carrier materials to desired applications, hard-soft composites can be employed to in vitro cultures, on the skin of test subjects, or even implanted into organisms.

2.5. Reactivity of the materials

Biointerfaces are formed in environments that inherently can be volatile and difficult to design and control for. Cells and tissues present on the materials possess a wide range of pH values, varying concentration of ions, and a spectrum of molecules and biomolecules – most of them chemically active. For achieving chemically stable and electrically functional devices over a desired time frame, it is important to keep in mind the chemical processes that it undergoes during its operation. Depending on the application, this can be undesired or desired. Careful investigation of chemical properties of the material allows for proper tuning of its stability.

2.5.1. Reactivity of the components

Bioelectronic components might be either unintentionally or intentionally reactive. Unintentional reactivity leads mostly to deterioration of the materials causing it to lose performance over time due to mechanical damage, chemical disintegration, or loss of electrical or electrochemical properties. Constituents released into the environment might also in turn react with biological structures. Unintentional reactivity can be minimized with the use of materials that are inert to their environment or chemical passivation of their surfaces. Some materials, such as faradaic electrodes, require chemical reactions to perform their functions. Such materials will unavoidably interact chemically with the environment. This must be taken into account when designing the system. In this case, utilizing reversible redox reactions can substantially increase the lifetime of the interface. Other intentionally reactive materials are ones that undergo controlled disintegration and can be used for the applications in transient electronics – devices which do not require extraction as they safely decompose in biological conditions. Finally, reactive materials can be used to adapt to their environment or have self-healing properties. Achieving these properties requires careful study of chemistries present in the environment and the device alike.

2.5.2. Consequences of reactivity

Reactive components will inevitably interact with their environment. Almost all devices undergo some deterioration and releases in a small number of their constituents, but for some transient applications in modulation or sensing, e.g., intermediate heart pacing or drug delivery, long term stability might be undesired. An ideal device could be implanted and, after fulfilling its duty, decompose and be safely metabolized by an organism.125 This approach would make a follow-up surgical extraction of the device unnecessary. For both cases it is important to ensure that the release of the material or its constituents into the system will not impair the development of cells and tissues or alter the cellular process in a harmful way.126, 127

Important classes of reactive materials are those capable of self-repair and self-healing. Inspired by biological systems, these materials are able to self-regenerate from mechanical and chemical damages and regain their original properties.115 Self-healing properties arise from the insightful engineering of the chemical interactions present in the structure of materials. They can be realized using either reversible reactions or through the implementation of mechanisms or catalysts that can be activated by damages to help the material recover its integrity.39 In turn, these can be engineered using independent chemistries or processes working in concert with the biological environment. Self-healing properties are essential for conductive materials, which require constant electrical continuity for their uninterrupted operation. It is expected that the long-term integration of bioelectronics will require some type of regeneration ability in such materials.

3. Inorganic semiconductor-based bioelectronics

3.1. Si-based bioelectronics

Inorganic semiconductors are widely utilized in electronic and photonic bio-interface research. They are essential for the design of high performance devices with desirable applications such as electronic sensing, signal amplification and transduction.22, 38 In particular, semiconducting Si has attracted researchers’ interest due to its biocompatibility and well-developed microfabrication methods.38 Si exhibits high charge carrier mobilities (electron mobility ~1300 cm2⋅V−1⋅s−1; holes mobility ~400 cm2⋅V−1⋅s−1 at 300K), leading to rapid responses and good sensitivity for the device performances. This property enables accurate probing of complex biological dynamics128 with bioelectronic devices. The well-established and precisely-controlled synthesis of Si makes it easy to fabricate various architectures from nano- to macroscopic scale. Such multiscale material control matches well with the multi-scale application for different biological components and enables integration with various biological systems.38 More specifically, one-dimensional (1D) Si nanostructures, exhibiting improved mechanical flexibility and increased carrier transportation capacity, can be delivered into neural cultures or tissues in a drug-like manner with high spatial resolution.22, 129, 130 In this section, we review and discuss several chemistry aspects of Si-based biointegrated systems, including the synthetic chemistry of Si nanostructures, chemical and biochemical sensing by Si-based transistors, photoelectrochemistry and electrochemistry of Si materials, surface chemistry for biocompatibility and specific targeting, and chemical etching and degradation.

3.1.1. Overview of synthesis methods for Si-based structures

Chemical vapour deposition (CVD) is a commonly used strategy to produce Si-based materials.131 In a CVD system, Si nanowires (SiNWs) are typically synthesized through the vapor–liquid–solid (VLS) growth mechanism.38 Metal catalysts, e.g., Au, Pt or copper (Cu), act as energetically preferential sites for the absorption and decomposition of gas-phase Si precursors (e.g., silane (SiH4), disilane (Si2H6), or silicon tetrachloride (SiCl4)), when operated above the eutectic temperatures. The continuously fed gas reactants establish supersaturated metal/Si alloy droplets, followed by the nucleation and precipitation of SiNWs. Besides producing nanowires, CVD is also useful in the scaleable synthesis of a variety of other nanostructures, such as 0D nanoparticles, 2D multilayered membranes,38 and 3D mesoporous structures.67 In particular, the Si mesoporous structures were synthesized from a nano-casting method by using mesoporous silica (e.g., SBA-15) as a template, in which SiH4 was decomposed inside the mesopores in a CVD system. Precision Si synthesis in a CVD system is important since the doping profile, morphology, and crystal structure can determine their physical properties and the corresponding bioelectronic applications.38

Besides the conventional vacuum processes and vapour-phase deposition method, Si structures can also be synthesized by solution processes.132 For example, hydrogenated polysilanes are feasible liquid Si precursors, as they show excellent solubility in organic solvents.132 In a nitrogen atmosphere, through a photo-polymerization process under UV light and a heat treatment, polycrystalline Si can be obtained from the polysilane precursor. As scaleable fabrication methods such as spin-coating or ink-jetting can be used, poly-Si films with large area and high electron mobilities (e.g., 108 cm2⋅V−1⋅s−1) have been produced.132 Crystallized Si can also be obtained at high temperature (>745 °C) in a molten salt system. For example, SiO2 nanoparticles were used as the precursor to produce Si in a CaCl2 molten salt (850 °C) system.133

Chemical etching methods are also commonly used for the synthesis of Si-based materials.134, 135 In a hydrofluoric acid/hydrogen peroxide (HF/H2O2) solution, Si can be selectively removed by a metal-assisted chemical etching (MACE) process, where noble metals serve as catalytic sites for directional etching.135 MACE has produced various morphologies, such as nano- or microwires,136 needles,137, 138 thin films,139, 140 and other structures.141, 142 In a recent example, it was found that even atomic Au can trigger the MACE process, producing SiNWs with massively parallel 3D grooves on their sidewalls. The groove spacing can be as small as ~5 nm, and the starting atomic Au patterns were likely generated by a ‘stick-slip’-like droplet instability during the VLS growth (Fig. 4a).143

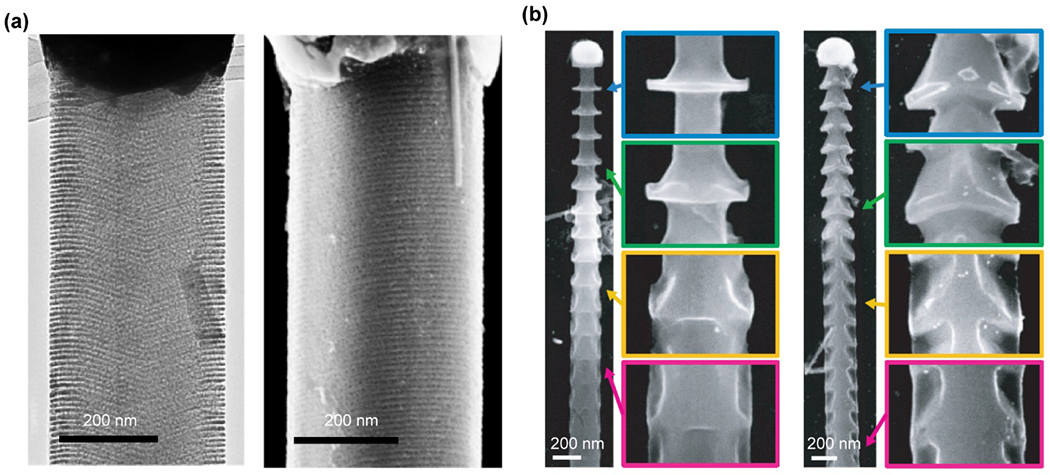

Figure 4.

Si nanowires with various structures and morphologies can be produced from metal-assisted chemical etching methods. (a) SiNWs with ordered grooves, etched from a mixture of hydrofluoric acid/hydrogen peroxide. Reproduced from ref.143 under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License from Springer Nature, copyright 2017. (b) SiNWs spicules formed by wet chemical etching in KOH solutions. Reproduced from ref.144 with permission from the American Association for the Advancement of Science, copyright 2015.

Many other chemical etching methods, such as KOH etching or defect selective etching using solutions such as K2Cr2O7/HF or CrO3/HF, are also efficient routes for the fabrication of Si nanostructures.144–150 For example, anisotropic SiNW spicules were synthesized by wet chemical etching of p-doped SiNWs in KOH solutions (Fig. 4b), using atomic Au diffusion–induced patterns as the etch mask.144 An ENGRAVE (Encoded Nanowire Growth and Appearance through VLS and Etching) strategy was also developed to control the etching rate of Si in KOH using variable dopant concentrations.145–147 Specialized features ranging between 10 nm to 700 nm in length have been successfully encoded along the SiNWs.145–147

Finally, electrochemical etching allows for the synthesis of nanoporous Si films and particles from single-crystal Si substrates.139 The loose porous structures in electrochemically etched Si substantially reduced the Young’s modulus,67, 137 which is beneficial for establishing minimally invasive biointerfaces.

3.1.2. Degradation of Si-based structures

The physical and chemical properties of Si-based electronics are known to be very stable at dry states. But for bioelectronic applications, the degradation of Si at biointerfaces needs to be carefully considered in wet environments.151 Si reacts with water via hydrolysis to form silicic acid Si(OH)4: Si + 4H2O → Si(OH)4 + 2H2, where the Si(OH)4 departs the Si surface through diffusion. Silicon dioxide (SiO2) may also form as an intermediate.134 Several parameters play important roles in the degradation, including surface chemistry, dopants, pH, ion concentration and temperature.128, 152–155 Understanding the chemical processes of Si degradation has already opened a new way toward safer biomedical applications, e.g., in vivo implants based on transient electronics.125, 134, 156–159

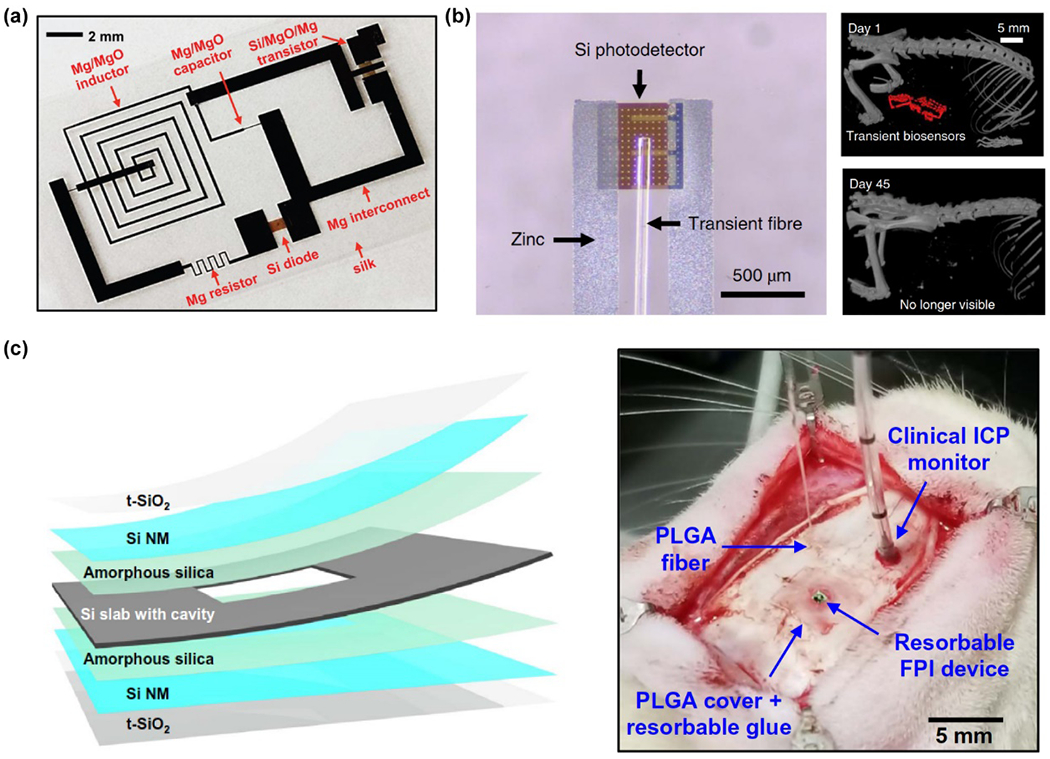

Ultrathin single crystalline Si nanomembranes (SiNMs) are the main constituent in several well-performing, transient electronic systems. For example, Hwang et al. developed a transient integrated circuit by using degradable materials such as magnesium (Mg), MgO/SiO2, Si, and silk for parts like inductors, capacitors, and transistors (Fig. 5a).134 Si nanomembranes of 70 nm thickness were dissolved via hydrolysis with speeds of 4.5 nm/day and 2 nm/day under physiological temperatures (37°C) and room temperature (25°C), respectively. Magnesium coils, Si Joule heating elements, and silk substrates and packages conferred transient thermal protection against infection, as increased local temperature suppressed bacterial growth as well as eased pain. Similarly, Bai et al. developed injectable bioresorbable devices that can be naturally resorbed or undergo clearance from the body after an operational lifetime (Fig. 5b).160 This bioresorbable device can be successfully used for continuous checking of the cerebral microenvironment (i.e., temperature changes, oxygenation and neural activity) in freely moving mice. More recently, Shin et al. developed SiNM-based bioresorbable optical pressure sensors that depend on pressure-induced deflections of SiNM diaphragms (Fig. 5c).157 The potential of using this material, which is also compatible with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), for clinical applications is very promising based on in vitro studies, histopathological evaluations, and acute measurements of intracranial pressure (ICP) and temperature (ICT).

Figure 5.

Transient and bioresorbable electronics derived from the degradation of Si and other transient materials. (a) Optical image of circuit design and components of a transient device. Reproduced from ref.134 with permission from the American Association for the Advancement of Science, copyright 2012. (b) Left: photograph of a SiNM-based bioresorbable spectrometer. Right: implanted device can be naturally resorbed after 45 days. Reproduced from ref.160 with permission from Springer Nature, copyright 2019. (c) Left: a schematic diagram of a SiNM-based bioresorbable sensor designed for the measurements of intracranial pressure (ICP) and temperature (ICT). Right: photograph of the bioresorbable sensor implanted in the intracranial space of a rat. Reproduced from ref.157 with permission from the American Association for the Advancement of Science, copyright 2019.

For long-term applications of Si-based bioelectronics,161, 162 degradation needs to be minimized. One technique for accomplishing this employs a thermal oxide thin layer directly grown on the surface, which can prevent biodegradation in phosphate-buffered saline solution.163 Several efficient passivation coating materials also work well to inhibit Si degradations, including stable Al2O3,162 TiO2,164 and SrTiO3.165 As demonstrated by Hu et al., atomic layer deposition (ALD) of TiO2 layer (4 to 143 nm thick) significantly improves the stability of Si photoanodes under basic water oxidation conditions.161 More generally, TiO2 stabilizes many semiconductors during oxidative photochemical processes by engineering the band structures and the defect states.

3.1.3. Chemistry for optical functionalities at the Si biointerfaces

Among the many useful functions of Si semiconductors, their ability to convert light into electric current is one of the most important uses. After Si semiconductors absorb light, the photonic energy can be transferred into electronic energy. When Si-based materials are used in cell cultures or as implants, they are usually surrounded by biological fluids, forming semiconductor/saline interfaces. With light, this can yield transient, photocapacitive modulation of cells or tissues (Fig. 3), or longer-lasting photofaradic reactions (Fig. 3) where the electrons and holes participate in cathodic and anodic reactions, respectively.

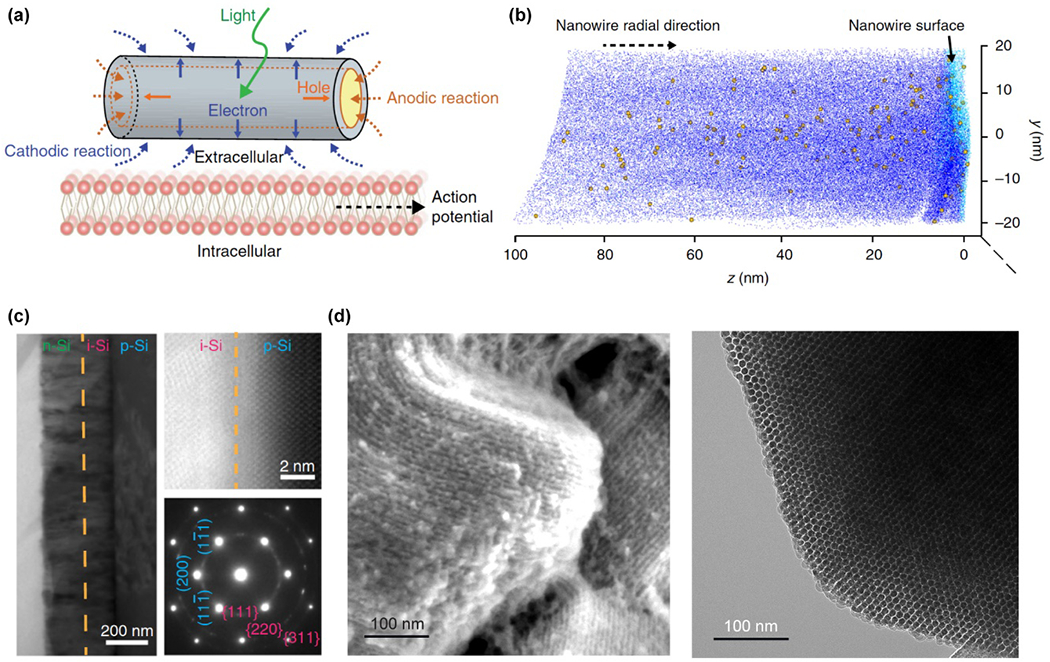

Palanker et al. developed a series of photovoltaic retinal implants, where the high-pixel-density devices provide local modulation of rat retinal neurons for potential restoration of vision.166–168 In order to enhance photostimulation by nano-bioelectronic devices, the photovoltaic or photoelectrochemical effect must be maximized. Parameswaran et al. found that dopant modulation and surface chemistry of the Si nanostructures could enhance their performance as neuromodulators (Fig. 6a).129 They used coaxial p-type/intrinsic/n-type (p-i-n) SiNWs, each consisting of a p-doped core nanowire, an interlayer of intrinsic Si, and a n-doped shell, to modulate primary rat dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons through photoelectrochemical processes. Experiments also showed that diffused atomic Au on the SiNW sidewalls could significantly enhance the generation of photoelectrochemical currents, and thus the neuromodulation efficacy (Fig. 6b).129 A similar conclusion was found in another study conducted by Jiang et al., which studied 2D p-i-n Si membranes with noble metal nanoparticles (e.g., Au, Ag and Pt) decorated on their surfaces by means of an electroless deposition method.38 They found that metal-decorated p-i-n membranes enhanced photoelectrochemical current generation by at least an order of magnitude. This successfully yielded photo stimulation of the brain cortex and behavior control (Fig. 6c).38 Si photovoltaic devices can also play a key role in ultrasensitive detection of biometric signals. Yokota et al. recently reported the fabrication of a conformable imager derived from low-temperature polycrystalline Si (LTPS) thin-film transistor (TFT), which can read out small photocurrents of less than 10 pA with low noise.169 The TFT readout circuits are designed by Si oxide film (SiO), Si nitride film (SiN), and amorphous Si film (a-Si) that was transferred from polycrystalline Si through excimer laser annealing. Combined with sensitive organic detectors, the imager can detect and calibrate the displacement of the device electronically on the basis of fingerprint or vein feature points.

Figure 6.

Si nanostructures used in the photo stimulation of cells. (a) A schematic diagram shows coaxial p-type/intrinsic/n-type (p-i-n) SiNWs for photoelectrochemical extracellular modulation of DRG neuron membrane potential. (b) Atom probe tomography shows the presence of diffused Au (yellow balls) on the sidewalls of p-i-n SiNWs (Si atoms: dark blur; O atoms: light blue). (a) and (b) Reproduced from ref.129 with permission from Springer Nature, copyright 2018. (c) Cross-section TEM image (left), scanning TEM (STEM) image (upper right) and the diffraction pattern of a p-i-n Si membrane nanostructure applied for the photostimulation of brain cortex and behavior control. Reproduced from ref.38 with permission from Springer Nature, copyright 2018. (d) Left: SEM image of nanostructures of replica Si from hexagonal mesoporous silica SBA-15, which were applied in the elicitation of action potential by photothermal effect. Right: TEM image shows the hexagonal packing of a Si nanowire. Reproduced from ref.67 with permission from Springer Nature, copyright 2016.

Electric energy generated from light radiation on Si can also be converted into heat, in a process known as the photothermal effect as described in section 2.3.4 (Fig. 3). The local temperature increase induced by light can be exploited to activate biological responses. This is a promising avenue for Si-based photostimulation. Researchers have developed strategies to enhance this Si photothermal effect. Jiang et al, developed mesoporous Si microparticles with a nano-casting method (Fig. 6d).67 The replica Si from hexagonal mesoporous silica SBA-15 display open-framework and porosity. The microparticles have an improved photothermal effect, as the porosity reduces the thermal conductivity and heat capacity but enhanced the light absorption. This mesoporous Si can modulate action potential (AP) firing and deterministic neuronal responses up to ~15 Hz through an optocapacitance mechanism.67

3.1.4. Chemistry for electrical functionalities at the Si biointerfaces

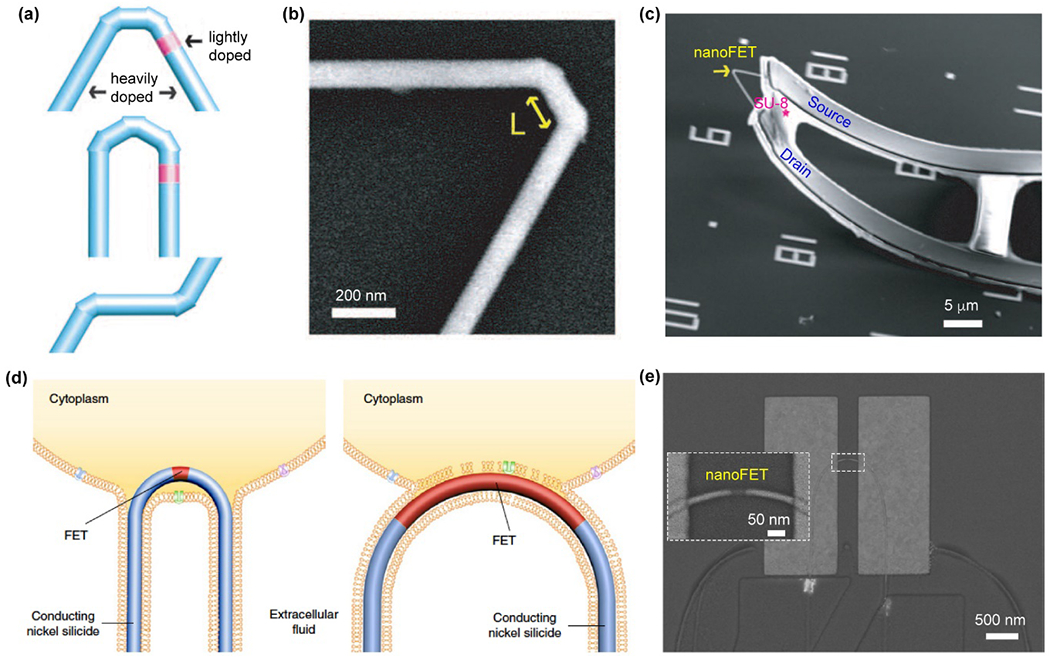

One of the most common applications for semiconductor-based bioelectronics is sensing bioelectrical signals. While patch-clamp electrodes have been developed enough that they can sense localized electrical signals from single ion channels, the electrodes are invasive and the biointerface is brief. With a smaller dimensionality, SiNW-based nano-bioelectronics43, 170–172 have been developed for intracellular recordings.43 The chemical designs of the SiNWs play a key role in facilitating the intracellular entrance. For example, the first nanoscale FETs (nanoFETs) used for intracellular electrical recording involved the CVD synthesis of kinked nanowires with dopant modulation. The kinked SiNWs with two cis-linked kinks of an overall ~60° angle of the bent junction were achieved by repeated pressure modulations (Fig. 7a–c).43 The nano-sized FET region was established by inserting a lightly doped region (~200 nm) in heavily doped n-type nanowire backbone (Fig. 7a). Such doping control enables a localized FET region for sensitive intracellular recording. 43

Figure 7.

Si-based nanoFET for intracellular recordings. (a) A schematic diagram of the nano-sized FET region, which was introduced by dopant modulation on kinked nanowires. (b) A SEM image of a kinked Si nanowire. (c) NanoFET on an SU-8 microribbon support. (a) – (c) Reproduced from ref.43 with permission from the American Association for the Advancement of Science, copyright 2010. (d) A schematic diagram of probe internalization and intracellular recording by short channel nanoFETs. (e) SEM image of a U-shape nanoFET with atomically sharp nickel silicide interfaces. (d) and (e) Reproduced from ref.175 with permission from Springer Nature, copyright 2019.

Atomically sharp nickel silicide interfaces derived from solid-state reactions on Si nanowires yielded short-channel nanoFET devices.173 Using this method, Zhao et al. realized a scaleable fabrication of highly sensitive nano-bioelectronics (Fig. 7d and e) through deterministic shape-controlled nanowire assembly.174, 175 These devices were able to record the full amplitude APs from primary neurons and other electrogenic cells in a multiplexed layout.

Additionally, the Rogers group has developed a series of works about the thermal growth of SiO2 layers over Si nanomembranes. This oxide design not only enabled the electrical coupling of devices to tissues, but also served as an encapsulating material against the penetration of biofluids. These bioelectronic devices showed safe and long-term applicability, including epicardial mapping of ex vivo hearts and electrical stimulation.176–178

Lastly, molecular functionalization of silicon surfaces has been widely applied to improve the electrical performance of silicon substrates in biosensing applications and memory devices.179 H-terminated silicon surface can be directly or indirectly coupled with electrically active moieties via oxide-free functionalization. Such moieties include but are not limited to ferrocene,180–182 quinones,183 metal-complexed porphyrins,184 tetrathiafulvalene (TTF),185, 186 and fullerene (C60).187, 188 Additionally, Bunimovich et al. reported FET-based biosensors with oxide-free Si–C layers that showed exceptional sensitivity (< 0.1×10−9 M) in DNA detection,189 where single-stranded DNA was electrostatically adsorbed. Changes of molecular length, packing density, and coverage in surface terminating groups can largely influence insulating properties and capacitance performance.180, 190–192

3.1.5. Chemistry for tight integration at Si biointerfaces

Overall, molecules with a variety of terminal groups can be anchored directly onto silicon surfaces via covalent bonds, e.g., silicon-carbon, silicon-nitrogen, and silicon-oxygen bonds. The resultant properties strongly depend on the surface molecular layer formation processes, which include carbonization, oxidation, hydrolytic condensation, thermal dehydrocoupling, and ring-opening click chemistry.193, 194 The functionalized surface monolayer further serves to provide linkages that are useful for attachment of native bioderivatives (e.g., peptide motifs195, 196 and proteins197–200) and synthetic nanomaterials.201 When immobilized on the silicon surfaces, these species can effectively improve cell-silicon interactions or biosensing abilities.89, 202

Si surface chemistry plays an important role in the interaction between Si-based materials and biological targets. For example, surface modifications of Si substrates with polylysine can be used for deterministic patterning of Si/neurite interfaces.203 Surface modification can also enable controlled cellular internalization of SiNWs. Zhang et al. reported strong interactions between SiNWs modified with folate and CHO-β cells, and uptake of the modified SiNWs by the cells.204 Surface coating of SiNWs has also facilitated intracellular recording. The Lieber group has reported several cases which showed that surface modification of SiNW-based nanoFET probes with a phospholipid bilayer can promote intracellular entrance for the device through a possible membrane fusion process.42, 43, 175

Surface geometry modification can also help establish close biological integration. For example, through Au diffusion in SiNW growth and subsequent wet-chemical etching, Luo et al. reported the synthesis of anisotropic Si spicules (Fig. 4b). With a spiky sidewall, the spicules established very strong mechanical interactions with extracellular matrix materials, such as a collagen hydrogel144. Similar structural features may be adopted for future implantable material design and implementation.

3.2. Other inorganic semiconductor-based materials

Besides Si, inorganic semiconductors such as ZnS nanoparticles, TiO2 nanotubes, MoS2 nanosheets, and many other metal oxides and metal sulfides have also been widely used in bioelectronics or bioelectrical studies. Their stability, diverse band gaps, and broad range of nanostructures make them good candidates for chemical and biological sensing, in vitro or in vivo labeling, and energy transduction at biointerfaces.205–208

3.2.1. General synthesis methods

Here we discuss a number of methods for synthesizing semiconductors that are tailored to fit the eventual biological question or application for the materials. The four processes we focus on are gas phase, solution phase colloidal, electrodeposition/molten salt-enabled, and bioinspired mineralization syntheses. These techniques allow for a vast array of possible compositions and device geometries, depending on the specific needs of the biointerface with respect to parameters such as band gap, size, and toxicity. For instance, interfaces intended to be used with photoelectrochemical modulation work best with bandgaps in the visible light range.

a). Gas phase synthesis

Conventional epitaxial growth methods of semiconductor thin films include molecular beam epitaxy (MBE), pulsed laser deposition (PLD), and CVD.209 The MBE method could precisely control the growth process at the atomic level. However, ultrahigh-vacuum (<10−10 torr) conditions are required. PLD requires a low-pressure system in the presence of precursor gases such as O2, N2 and H2 and is good at creating artificially layered oxides for fabrication of oxide electronic and magnetic materials. CVD and metal-organic chemical vapour deposition (MOCVD) are most commonly used methods for semiconductor thin film epitaxial growth. Various kinds of semiconductor thin films, such as MoS2,210 WS2,211 WSe2,212 SiGe,213 GaAs,214 InGaP,215 and GaN216 have been synthesized from the CVD or MOCVD methods.123, 205, 217 Semiconductor thin films with single-atom thickness and unique electronic band structures provide key advantages in developing novel electronic and photonic devices.218 Compared with other synthesis methods, the precise control over chemical composition, the high-quality crystalline nature, and the low defect level of semiconductor thin films ensure excellent electrical and optical properties across the entire materials.208 Additionally, CVD and MOCVD syntheses can produce bulky chips and circuits for future large-scale bioelectronic applications.

b). Solution phase colloidal synthesis

There are a variety of solution-based methods available, including sol–gel process, co-precipitation, thermal decomposition, and hydrothermal method. The sol–gel process, i.e., hydrolysis and polycondensation of metal alkoxide (or halide)-based precursors, has been applied to synthesize nanocrystalline or amorphous semiconductors. For making nanocrystals with a narrow size distribution, co-precipitation is widely used, as its lack of extra calcination and post-annealing steps make it more convenient. Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP), polyethylenimine (PEI), and other capping molecules have been used for tailoring the particle nucleation and growth kinetics and for stabilizing nanocrystals. Solution-phase methods provide a variety of synthetic combinations for different structural and compositional features. Furthermore, dopants enable tuneable electronic and photonic properties to meet desired specific requirements at biointerfaces.219

c). Electrodeposition/molten salt method

GaAs, GaP, InP, and GaInP2, can also be synthesized using electrodeposition in plating solutions.220 For example, GaAs can be co-deposited by Ga(III) and As(III) oxides (e.g., H3AsO3, HAsO32−) through high temperature reduction and sequential room temperature aqueous solution deposition. Because the as-deposited semiconductors are usually amorphous or poorly crystallized, further annealing processes are frequently required. Electrodeposition of GaP or InP is usually completed by melting eutectics, e.g., NaF/NaPO3/Ga2O3 or In2O3/NaPO3/KPO3/NaF/KF salts at about 600-900 °C. Alternately, a two-step method involving cathodic electrodeposition of In, followed by post-deposition phosphorization with red phosphorus also resulted in the synthesis of InP.

d). Bioinspired mineralization processes

Ion exchange methods developed by Holtus et al. have demonstrated the successful transformation of carbonate minerals into perovskite semiconductors.221 This method can be used to produce 3D structures with tuneable bandgaps, without significant changes to the overall morphology of the material. This raises the possibility of combinatorial investigations into biointerface formation, where the material structure remains consistent, but the electrical parameters of the material vary.

3.2.2. Quantum dots-based bioelectrical studies

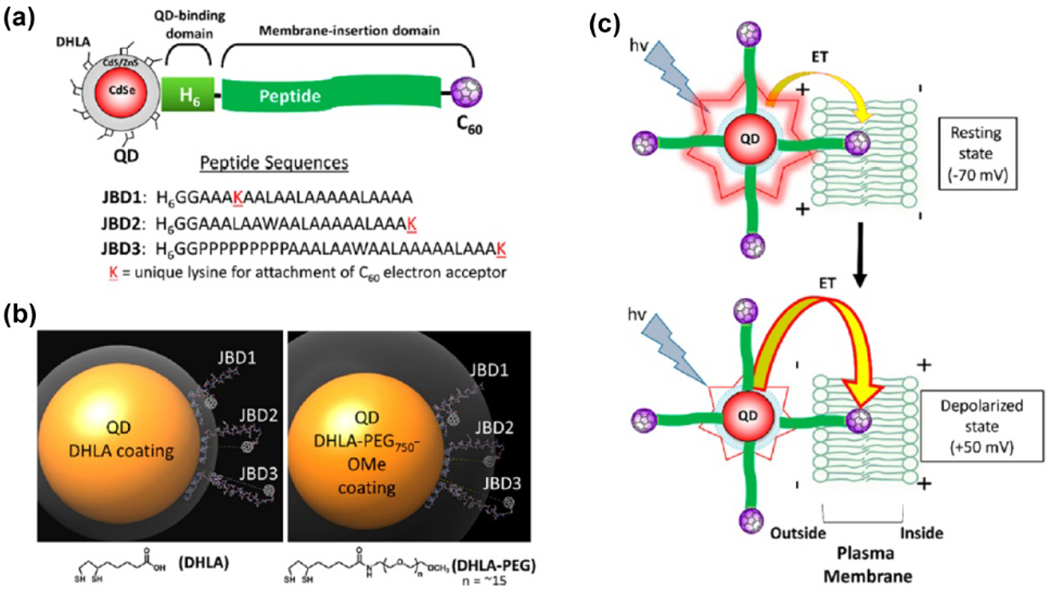

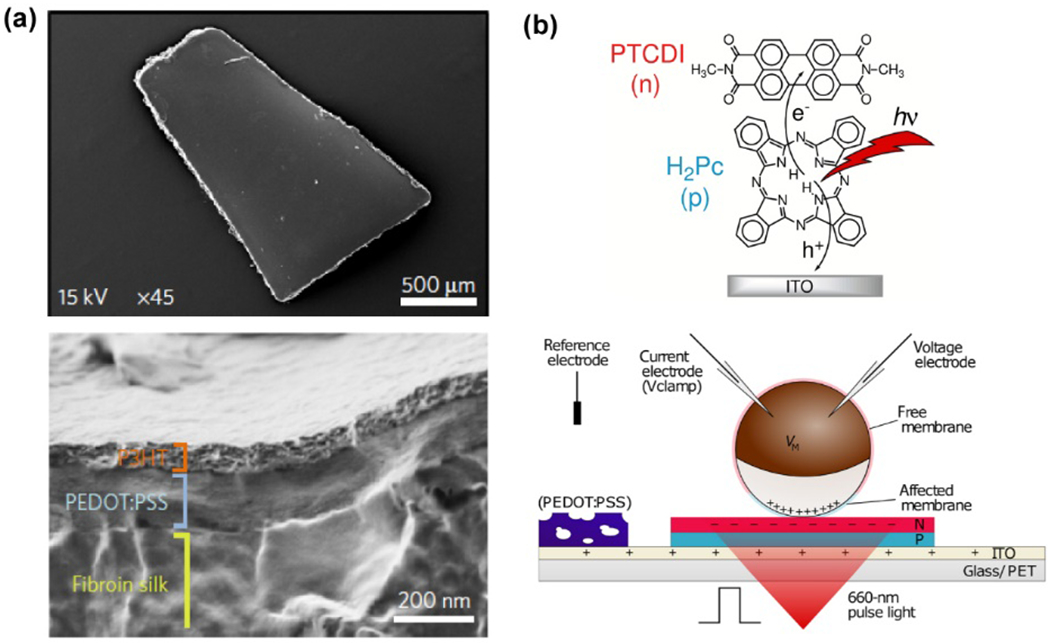

The photoluminescence of semiconductor materials, especially for quantum dots, has been widely used for cell and tissue imaging.154, 222 They are used to track organelle or cell dynamics upon electrical modulation or for correlative bioelectronic sensing and imaging. Quantum dots have been demonstrated to be nanosized tools which can efficiently record subthreshold and suprathreshold events. In particular, detecting bioelectrical events in the space between two lipid layers of the cell membrane (Fig. 3) has been proposed and demonstrated preliminarily,223–225 which is challenging for electrode recording methods. By coupling quantum dots with other molecular systems, bioelectrical sensing in neural membranes can also be conducted. For example, Nag et al. reported using CdSe/CdS/ZnS QD for electric field-sensitive charge transfer and for mapping membrane potential in living cells (Fig. 8).225 They designed a QD (electron donor) – peptide/fullerene (electron acceptor) bioconjugated system, where hydrophilic QDs were localized at exofacial leaflets of the plasma membrane while multiple copies of hydrophobic peptide–C60 fullerenes self-assembled within the lipid bilayer.225 Upon membrane depolarization, electrons transfer with enhanced basal rate from the photoexcited QD donor to the fullerene acceptor, giving rise to further quenching of QD/PL. The fluorescence response of this integrated bioelectrical probe exhibits comparable temporal responsiveness, but with 20- to 40-fold greater normalized change in fluorescence values than those reported for voltage-sensitive dyes.

Figure 8.

QD applied for bioelectronic voltage sensing in neural membranes. (a) A schematic diagram and (b) molecular models for the design of the QD (electron donor) – peptide-fullerene (electron acceptor) bioconjugated system. (c) A schematic diagram for the fluorescence change introduced by membrane depolarization process. The electrons transfer from the photoexcited QD donor to the fullerene acceptor when the plasma membrane is depolarized, giving rise to the quenching of PL. Reproduced from ref.225 with permission from the American Chemical Society, copyright 2017.

Moreover, the nanoscale sizes of QDs have enabled light-triggered redox reactivity in the cytosolic space from the subcellular biointerfaces. This has produced light-harvesting bacteria and yeast cells for energy-efficient biofuel or fine chemical production, a new approach in synthetic biology and biomanufacturing.226–230

Finally, the emission from QDs can be used for optogenetics stimulation. A notable example is a recent demonstration of using ZnS-based mechanoluminescent QDs for ultrasound-triggered optogenetics231. The photoexcited QDs were injected into the blood circulation and can be recharged by 400 nm light at the superficial vessel location. The QDs emit light on-demand by applying a focused ultrasound through intact scalp and skull. This demonstration opens up a new avenue for future in vivo bioelectrical studies with QDs.

3.2.3. 2D-semiconductors bioelectronics

2D semiconductors such as MoS2226–229, just a few nanometres in thickness, are good candidates for soft bioelectronics.232 The band gap of monolayer MoS2 is 1.8 eV and 1.2 eV for the bulk.233 MoS2-based FET devices have a high on/off ratio,205, 234 together with high surface-to-volume ratio, which makes them highly suitable for bioelectronic sensing.123, 213 Sarkar et al. reported a MoS2-based FET sensor that can detect streptavidin at ultralow concentrations, about 100 fM.232 Additionally, the flexibility and the piezoresistivity of MoS2235 have enable the fabrication of a skin-like tactile sensor array, as reported by Park et al.236 This MoS2-based conformal tactile sensor can be placed over uncommon surfaces such as leather and a human fingertip. The device showed sensitive and robust behaviors and linear responses even after 10,000 loading cycles.

2D semiconductors also possess advantages for optoelectronic applications due to their excellent absorption in the visible range and the capability to generate photocurrent. For example, Choi et al. reported the design of a human eye-inspired, hemispheric image sensor with high array density, which was fabricated from a MoS2-graphene heterostructure.237 These soft implantable bioelectronics act as retinal prosthetics and can successfully stimulate optic neuronal cells of a rat under external optical irradiation. Furthermore, MoS2 demonstrates high rates of electron-hole pair generation in response to illumination. Liu et al. reported that the reactive oxygen species (ROS) generated from the photocatalysis effect of few-layered vertically aligned MoS2 achieved E. coli disinfection with >99.999% inactivation.236 Photoexcited electron–hole pairs in other semiconductor composites,238, 239 such as C3N4/rGO heterojunctions,240 may also enable the photocatalytic effect in cells and tissue. Zhang et al. reported a modulation neuronal interface between C3N4 and PC12 cells, where neuronal differentiation can be achieved upon photostimulation.240 Moreover, the photocatalytic effect has enabled g-C3N4 mediated conversion of NADH into NAD+, a process which can be utilized for the catalytic synthesis of L-lactate from L-lactate dehydrogenase.241–243

The shape, dimensions, chemical composition, and surface properties of 2D semiconductors are all related to their biocompatibility. While 2D MoS2 has been demonstrated to show low cytotoxicity,244, 245 biocompatibility in vitro and in vivo remains a concern for other 2D materials, especially for those transition metal dichalcogenides containing Se, Te, or As.246–248

3.2.4. Metal oxide-based bioelectronics

Many metal oxide semiconductors can be configured as FET devices. For example, Nakatsuka et al. used thin-film In2O3 FETs for biomolecular sensing under physiological condition. They modified their FETs with DNA aptamers whose conformation changes upon binding to various molecules such as serotonin, dopamine, glucose and sphingosine-1-phosphate. Notably, the detected molecular concentration ranges from 10−14 to 10−9 M in PBS solution, overcoming the limitations of Debye screening .249