Abstract

FGFR3 is a prognostic and predictive marker and is a validated therapeutic target in urothelial bladder cancer. Its utility as a marker and target in the context of immunotherapy is incompletely understood. We review the role of FGFR3 in bladder cancer and discuss preclinical and clinical clues of its effectiveness as a patient selection factor and therapeutic target in the era of immunotherapy.

Keywords: bladder cancer, fibroblast growth factor receptor, immunotherapy, pharmacogenetics, targeted molecular therapy

Introduction

Cytotoxic chemotherapy had been the only standard-of-care treatment for advanced urothelial bladder cancer, which is the world’s 10th most common cancer and thirteenth most deadly (1). Cisplatin-based regimens are associated with objective responses in up to 45% of patients, but these responses are generally not durable (2, 3). Cisplatin-based therapies are associated with toxicities, including treatment-related mortality in rare cases. Beginning with the regulatory approval of atezolizumab, an inhibitor of programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1), in 2016, a total of five immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), including the programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) inhibitors pembrolizumab and nivolumab and the PD-L1 inhibitors avelumab and durvalumab, gained regulatory approval for advanced urothelial cancer. These therapies are associated with durable responses in a minority of patients (roughly 15% among patients selected based on immune infiltration) and comparatively favorable side effect profiles (4). They have now been used in the first line alone and in combination with chemotherapy and are the preferred choice in the second line after chemotherapy (5–7).

In spite of the great therapeutic potential of ICIs, only a minority (approximately 20%) of patients experience tumoral response to ICIs and median survival with second line immunotherapy remains shorter than 1 year (8). It follows that the identification of biomarkers is a critical step in improving therapy for advanced urothelial bladder cancer. Recognition of characteristics associated with ICI response can help clinicians and researchers optimize patient selection, appreciate new combination or sequencing strategies, and identify mechanisms or targets for development of novel therapeutics. Tumoral PD-L1 expression is only modestly useful as a marker, as tumoral responses to ICI have been observed regardless of PD-L1 status (albeit at a numerically higher rate among those with greater PD-L1 expression) (9). Consensus molecular classifications, which define luminal, basal/squamous, stroma-rich, and neuroendocrine-like subgroups of muscle-invasive bladder cancer, although useful in understanding the biology of tumors, similarly fall short in helping to guide ICI therapy (10). The goal remains to discover tumor characteristics, drivers, and markers that can offer greater therapeutic and instructive value in the context of ICI therapy. Overactivity in the ErbB family (including EGFR and Her2/neu), which is associated with luminal and basal/squamous classifications, has only demonstrated utility as a drug target or predictive marker in a small proportion of clinical trials related to that pathway (11). Similarly, although VEGF activation portends poor outcomes, VEGF has not proved to be particularly promising as a therapeutic target (11). Mutations in DNA damage response genes, including ERCC1, ERCC2, ATM, FANCC, and RB1 can help predict response to platinum-based therapy, but markers for newer immune-based therapies are needed (11). The fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 (FGFR3) gene has long been associated with bladder cancer oncogenesis and recently become a therapeutic target (12). It has become particularly important in the context of immunotherapy given its inverse relationship with an anti-tumor immune response due, at least in part, to its association with a lymphocyte-excluded phenotype (13). We review the current knowledge of FGFR3 in the context of both modern therapies such as anti-PD-1 immunotherapy and FGFR blockade.

FGFR3 in Bladder Cancer

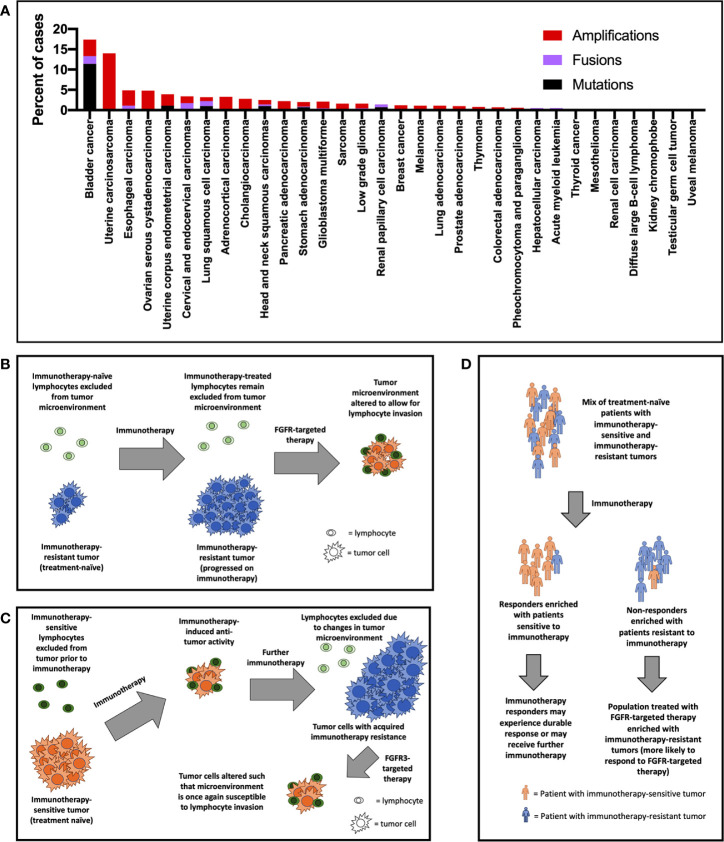

The chromosome 4 gene FGFR3 encodes the FGFR3 protein, a tyrosine kinase that has classically been known to play important roles in development, osteogenesis, and bone maintenance (14, 15). FGFR3 is highly expressed in chondrocytes and osteoblasts, and germline mutations are associated with bone growth disorders such as achondroplasia, chondrodysplasia, and thanatophoric dysplasia (16–20). Curiously, while activating mutations curb growth in bone, the same mutations are associated with excess growth in other tissues (e.g., nevi in skin) (21). Germline FGFR3 mutations are paternally inherited and are associated with advanced paternal age (22). The introduction of improved clinical genetic testing techniques in oncology has facilitated the discovery that FGFR3 gene alterations are implicated in a wide range of cancers [ Figure 1A , (23, 24)]. The prevalence of FGFR3 gene aberrations is highest in urothelial carcinomas (18% of cases), followed by uterine carcinosarcoma (14%), esophageal (5%), ovarian (5%), and endometrial (4%) cancers (23–25). FGFR3 signaling has been observed to overlap with known oncogenic pathways such as RAS/PI3K/ERK/AKT/EGFR and has been implicated in tumoral epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (26, 27). The role of FGFR3 gene in oncogenesis may even be at the pre-translational level: Has_circ_0068871, a circRNA product of FGFR3 gene transcription, is overexpressed in bladder cancer, and is associated with cancer cell proliferation and migration (28). Expression of the antisense transcript FGFR3-AS1, which increases stabilizes and promotes expression of FGFR3 mRNA, and which is overexpressed in urothelial tumors, is associated with tumor invasiveness, proliferation, and motility (29). The most common FGFR3 mutation, S249C, likely develops through an apoprotein B mRNA editing enzyme, catalytic polypeptide-like (APOBEC)-mediated mutagenic mechanism (30). FGFR3-transforming acid coiled coil 3 (TACC3) fusions, which result in constitutive signaling, represent another frequent source of FGFR3 gene aberration (31).

Figure 1.

(A) FGFR3 gene alterations by cancer type based on available data from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) (only recurrent mutations and fusions—those comprising in >1% of mutations/fusions—were included). Potential mechanisms of improved response rate to FGFR3-targeted therapy in the post-immunotherapy setting include (B) primary immunotherapy resistance, (C) secondary immunotherapy resistance, and (D) enrichment of patients with immunotherapy-resistant tumors in trials of FGFR3-targeted therapy.

As prognostic indicators, FGFR3 gene alterations are generally associated with lower grade and stage among all urothelial bladder carcinomas (32). Among non-muscle invasive cases, 49-84% express FGFR3, compared to 18% of muscle-invasive cases, and FGFR3 mutations are associated with lower disease-specific survival (32–34). Among American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) 8th edition T1 tumors, FGFR3 expression is associated with lower grade tumor and lower risk of cancer progression (35). FGFR3 gene mutations, amplifications, and fusions are associated with luminal-papillary subtype of urothelial cancer, which itself is associated with non-muscle invasive disease and favorable prognosis compared with other subtypes (13, 36, 37). However, in spite of the general association of FGFR3 alterations with favorable characteristics, there is no evidence to suggest that FGFR3 gene alterations correlate with a less aggressive phenotype once urothelial carcinoma has become advanced. In fact, FGFR3 gene alterations are associated with less favorable outcomes in the context of chemotherapy for advanced disease (38, 39).

The identification of FGFR3 as an oncogenic driver in urothelial cancer has led to the development of FGFR3-targeting therapeutics [ Table 1 , (40)]. While the dovitinib, which targets FGFR3, among other tyrosine kinases, showed poor single-agent activity in an unselected urothelial cancer patient population, using pan-FGFR inhibitors with greater target affinity in genomically selected populations has proven to be a more promising approach (41, 42). This observation may reflect a compensation of other FGFR isotypes when therapeutics target FGFR3 on its own. The FGFR1-4 inhibitor erdafitinib is the sole FGFR-targeting agent to which the United States Food and Drug Administration has granted regulatory approval to date. Erdafitinib is indicated for patients with FGFR2 or FGFR3-altered, platinum-treated urothelial cancer (43). Infigratinib, a FGFR1-3 inhibitor, has also demonstrated promising activity (44, 45). Rogaratinib, another pan-FGFR inhibitor is under investigation using FGFR1 or FGFR3 RNA expression levels, rather than genetic mutational status, as a patient selection criterion (46). The most common treatment-emergent toxicities among these agents are hyperphosphatemia, stomatitis, diarrhea, elevated creatinine, fatigue, hand-food syndrome, and decreased appetite. Although the FGFR-inhibitors are undoubtedly becoming a valuable component of the oncologist’s armamentarium for advanced bladder cancer treatment, a greater understanding is needed of how best to combine and sequence these medications with other therapies in the treatment paradigm.

Table 1.

FGFR inhibitors marketed or in development for bladder cancer.

| Medication name | Target | Manufacturer | Phase of development | Patient population | Combination | NCT identifier |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Erdafitinib

(Balversa) |

FGFR1-4 | Johnson & Johnson | Marketed | FGFR2/3 mutation or fusion | – | NCT02365597 |

| Ib/II | FGFR2/3 mutation or fusion | Cetrelimab (PD-1 inhibitor) | NCT03473743 | |||

|

Infigratinib

(BGJ398) |

FGFR1-3 | BridgeBio Pharma | III | Adjuvant, FGFR3 altered1 | – | NCT04197986 |

| Pilot | Non-muscle invasive, FGFR mutation or fusion | – | NCT02657486 | |||

|

Rogaratinib

(BAY 1163877) |

FGFR1-4 | Bayer | II/III | high FGFR1 or 3 expression | – | NCT03410693 |

| Ib/II | cisplatin-ineligible, high FGFR1, or three expression | Atezolizumab (PD-L1 inhibitor) | NCT03473756 | |||

|

Pemigatinib

(Pemazyre) |

FGFR1-3 | Incyte | II | FGF or FGFR alteration2 | – | NCT02872714 |

| II | platinum ineligible, FGFR3 mutation or rearrangement | Pembrolizumab (PD-1 inhibitor) | NCT04003610 | |||

| II | Non-muscle invasive (neoadjuvant) | – | NCT03914794 | |||

|

Derazantinib

(ARQ 087) |

Pan-FGFR | Basilea | Ib/II | FGFR altered2 | Atezolizumab (PD-L1 inhibitor) | NCT04045613 |

|

Vofatamab

(B701) |

FGFR3 | Rainier Therapeutics | Ib/II | Pembrolizumab (PD-1 inhibitor) | NCT03123055 |

1“Susceptible” FGFR3 mutations, fusions, or translocations.

2Definition of “altered” are not specified.

FGFR3 as a Therapeutic Target and as a Patient Selection Tool in Context of Immunotherapy for Bladder Cancer

The preclinical and correlative literature underpinning the rationale for combining FGFR3-targeted therapy with immunotherapy is substantial. Research in animal models have contributed to an appreciation of the potential synergies between these two mechanisms. Some studies have suggested that FGFR3 has an important role in regulating the innate immune system, including inhibition of interferons and stimulation of tumor necrosis factor-α (47, 48). Others have noted inhibitory effects on a broad range of components of the adaptive immune response, including lymphocyte infiltration, and T-cell CD8A expression, as well as stimulatory effects on the anti-inflammatory TGF-β response signature (13, 49–52). In fact, our previous work has suggested that FGFR3 mutations and FGFR3-TACC3 fusions may be associated exclusively with tumors that exhibit a lymphocyte-excluded phenotype. Moreover, the degree of FGFR3 expression predicts lymphocyte exclusion (13). Wnt/β-catenin signaling, which is associated with non-T-cell-inflamed tumors both in bladder cancers and across most solid cancers, has been shown to overlap with FGFR3 signaling (13, 53–55). In lung cancer models, FGFR3 inhibition enhances the effect of programmed cell death-1 (PD-1) blockade (56). However, evidence that FGFR3 pathways work in opposition to immune activity is not uniform: FGFR3 amplifications are associated with decreased anti-inflammatory M2 macrophage bladder tumor infiltration (51). Additionally, some correlative analyses have not detected a difference in ICI response rates among patients with FGFR3 mutations compared to those with the wild-type allele (52). Additionally, FGFR3 mutations are associated with lower PD-L1 expression, a marker that has been shown to have some correlation with ICI response in some bladder cancer trials (7, 50).

Investigational approaches studying the most appropriate role for FGFR inhibition in the context of ICI therapy (either through sequencing or combination) are generally in early clinical stages. The most robust experience available are what appear to be post-hoc analyses of FGFR inhibition following ICI therapy. In erdafitinib’s pivotal trial, patients who had previously received ICI therapy experienced higher response rates compared with the cohort as a whole (59% vs. 40%) (43, 57). Preliminary data with rogaratinib suggest a similar effect: an interim analysis of its phase I trial demonstrated 30% response among ICI-treated patients compared with 24% across all patients (58). There are several potential reasons for the finding of increased responsiveness to FGFR inhibitors after ICI ( Figures 1B–D ). It may be that previous ICI therapy primes patients for FGFR-targeted therapy – i.e., FGFR inhibition “sensitizes” the tumor to the effects of ICI by altering the microenvironment to allow for lymphocyte invasion ( Figure 1B ). Another related explanation for the clinical trial results is that tumors develop enhanced FGFR3 pathway (lymphocyte exclusionary) signaling as a resistance mechanism while on immunotherapy. Subsequent FGFR inhibition would disrupt this oncogenic tumoral lymphocyte exclusion ( Figure 1C ). A third possibility is that patients who fail immunotherapy tend to be patients whose tumors exhibit poor lymphocyte exclusion ( Figure 1D ). These may be the exact patients who we might expect to benefit most from FGFR-targeted therapy, which may directly address this immune deficit. These may also be patients whose tumors are driven by mechanisms unrelated to the immune system. Importantly, rogaratinib in combination with atezolizumab for first-line urothelial bladder cancer has now shown an objective response rate of 44% including a 16% complete response rate (59). Future research may provide insight to help identify which of these interpretations (or combination of these interpretations or different interpretation altogether) is most accurate. This research may help us understand to what degree FGFR-targeted therapy is best considered as a treatment to be sequenced with immunotherapy. Or, alternatively, to what degree patients who will benefit from FGFR-targeted therapies and those who will benefit from immunotherapy represent two distinct categories. Eventual analyses from currently ongoing phase Ib/II trials testing the FGFR inhibitors vofatamab (NCT03123055), erdafitinib (NCT03473743), and rogaratinib (NCT03473756) in combination with ICI therapies in broad (not genetically selected) populations may enhance our ability to evaluate these propositions.

Discussion

The FGFR3 gene is prevalent in bladder cancers and may hold value as a prognostic marker and as a tool for patient selection. FGFR3 mutations are associated with less aggressive disease across all bladder cancers, although this is not necessarily the case among advanced tumors. Therapies targeting the FGFR3 protein (and its isoforms) have demonstrated clinical benefit in some patients. However, clinicians still require a greater understanding of how these drugs fit into the treatment paradigm alongside immunotherapies. There is conflicting evidence from preclinical and retrospective correlative studies related to the scientific rationale for combining and/or sequencing FGFR-targeted therapies with immunotherapies. To date, the balance of data suggests that there may be a benefit to combining the two types of approaches. However, an alternate theory is that there may be some patients (perhaps those with tumors termed “immune hot” or “lymphocyte invasive”) may be candidates for immunotherapy and not FGFR-targeted therapy, while patients with so-called “immune cold” (or lymphocyte excluded) may be unlikely to benefit from immunotherapy and may be better off with FGFR inhibition earlier on. As FGFR inhibitors become more established in bladder cancer treatment and are studied in earlier lines of therapy, we should gain a more complete view of the best placement of these drugs within therapeutic algorithms.

Author Contributions

AK and RS conceived and wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This manuscript was supported by the NIH National Cancer Institute award K08CA234392.

Conflict of Interest

RS reports consulting/honoraria from Aduro, AstraZeneca, BMS, Exelixis, Eisai, Janssen, Mirati, and Puma. Grant/Research support (to institution): AbbVie, Bayer, BMS, CytomX, Eisai, EpiVax Oncology, Evelo, Genentech, Immunocore, Mirati, Merck, Novartis.

The remaining author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The handling editor declared a past co-authorship with one of the authors RS.

References

- 1. Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin (2018) 68(6):394–424. 10.3322/caac.21492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Logothetis CJ, Dexeus FH, Finn L, Sella A, Amato RJ, Ayala AG, et al. A prospective randomized trial comparing MVAC and CISCA chemotherapy for patients with metastatic urothelial tumors. J Clin Oncol (1990) 8(6):1050–5. 10.1200/JCO.1990.8.6.1050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Loehrer PJ, Einhorn LH, Elson PJ, Crawford ED, Kuebler P, Tannock I, et al. A randomized comparison of cisplatin alone or in combination with methotrexate, vinblastine, and doxorubicin in patients with metastatic urothelial carcinoma: a cooperative group study. J Clin Oncol (1992) 10(7):1066–73. 10.1200/JCO.1992.10.7.1066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Powles T, Durán I, van der Heijden MS, Loriot Y, Vogelzang NJ, De Giorgi U, et al. Atezolizumab versus chemotherapy in patients with platinum-treated locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma (IMvigor211): a multicentre, open-label, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet (2018) 391(10122):748–57. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)33297-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Flaig TW, Spiess PE, Agarwal N, Bangs R, Boorjian SA, Buyyounouski MK, et al. Bladder Cancer, Version 3.2020, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw (2020) 18(3):329–54. 10.6004/jnccn.2020.0011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rosenberg JE, Hoffman-Censits J, Powles T, van der Heijden MS, Balar AV, Necchi A, et al. Atezolizumab in patients with locally advanced and metastatic urothelial carcinoma who have progressed following treatment with platinum-based chemotherapy: a single-arm, multicentre, phase 2 trial. Lancet (2016) 387(10031):1909–20. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00561-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Galsky MD, Arija JÁA, Bamias A, Davis ID, De Santis M, Kikuchi E, et al. Atezolizumab with or without chemotherapy in metastatic urothelial cancer (IMvigor130): a multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet (2020) 395(10236):1547–57. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30230-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bellmunt J, de Wit R, Vaughn DJ, Fradet Y, Lee JL, Fong L, et al. Pembrolizumab as Second-Line Therapy for Advanced Urothelial Carcinoma. N Engl J Med (2017) 376(11):1015–26. 10.1056/NEJMoa1613683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Balar AV, Galsky MD, Rosenberg JE, Powles T, Petrylak DP, Bellmunt J, et al. Atezolizumab as first-line treatment in cisplatin-ineligible patients with locally advanced and metastatic urothelial carcinoma: a single-arm, multicentre, phase 2 trial. Lancet (2017) 389(10064):67–76. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32455-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kamoun A, de Reyniès A, Allory Y, Sjödahl G, Robertson AG, Seiler R, et al. A Consensus Molecular Classification of Muscle-invasive Bladder Cancer. Eur Urol (2020) 77(4):420–33. 10.1016/j.eururo.2019.11.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Andreatos N, Iyer G, Grivas P. Emerging biomarkers in urothelial carcinoma: Challenges and opportunities. Cancer Treat Res Commun (2020) 25:100179. 10.1016/j.ctarc.2020.100179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cappellen D, De Oliveira C, Ricol D, de Medina S, Bourdin J, Sastre-Garau X, et al. Frequent activating mutations of FGFR3 in human bladder and cervix carcinomas. Nat Genet (1999) 23(1):18–20. 10.1038/12615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sweis RF, Spranger S, Bao R, Paner GP, Stadler WM, Steinberg G, et al. Molecular Drivers of the Non-T-cell-Inflamed Tumor Microenvironment in Urothelial Bladder Cancer. Cancer Immunol Res (2016) 4(7):563–8. 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-15-0274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ledwon JK, Turin SY, Gosain AK, Topczewska JM. The expression of fgfr3 in the zebrafish head. Gene Expr Patterns (2018) 29:32–8. 10.1016/j.gep.2018.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wen X, Li X, Tang Y, Tang J, Zhou S, Xie Y, et al. Chondrocyte FGFR3 Regulates Bone Mass by Inhibiting Osteogenesis. J Biol Chem (2016) 291(48):24912–21. 10.1074/jbc.M116.730093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ornitz DM, Legeai-Mallet L. Achondroplasia: Development, pathogenesis, and therapy. Dev Dyn (2017) 246(4):291–309. 10.1002/dvdy.24479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kimura T, Ozaki T, Fujita K, Yamashita A, Morioka M, Ozono K, et al. Proposal of patient-specific growth plate cartilage xenograft model for FGFR3 chondrodysplasia. Osteoarthritis Cartilage (2018) 26(11):1551–61. 10.1016/j.joca.2018.07.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chang IJ, Sun A, Bouchard ML, Kamps SE, Hale S, Done S, et al. Novel phenotype of achondroplasia due to biallelic FGFR3 pathogenic variants. Am J Med Genet A (2018) 176(7):1675–9. 10.1002/ajmg.a.38839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lee YC, Song IW, Pai YJ, Chen SD, Chen YT. Knock-in human FGFR3 achondroplasia mutation as a mouse model for human skeletal dysplasia. Sci Rep (2017) 7:43220. 10.1038/srep43220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gomes MES, Kanazawa TY, Riba FR, Pereira NG, Zuma MCC, Rabelo NC, et al. Novel and Recurrent Mutations in the FGFR3 Gene and Double Heterozygosity Cases in a Cohort of Brazilian Patients with Skeletal Dysplasia. Mol Syndromol (2018) 9(2):92–9. 10.1159/000486697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Foldynova-Trantirkova S, Wilcox WR, Krejci P. Sixteen years and counting: the current understanding of fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 (FGFR3) signaling in skeletal dysplasias. Hum Mutat (2012) 33(1):29–41. 10.1002/humu.21636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wilkin DJ, Szabo JK, Cameron R, Henderson S, Bellus GA, Mack ML, et al. Mutations in fibroblast growth-factor receptor 3 in sporadic cases of achondroplasia occur exclusively on the paternally derived chromosome. Am J Hum Genet (1998) 63(3):711–6. 10.1086/302000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cerami E, Gao J, Dogrusoz U, Gross BE, Sumer SO, Aksoy BA, et al. The cBio cancer genomics portal: an open platform for exploring multidimensional cancer genomics data. Cancer Discov (2012) 2(5):401–4. 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gao J, Aksoy BA, Dogrusoz U, Dresdner G, Gross B, Sumer SO, et al. Integrative analysis of complex cancer genomics and clinical profiles using the cBioPortal. Sci Signal (2013) 6(269):pl1. 10.1126/scisignal.2004088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Klebanov N, Artomov M, Goggins WB, Daly E, Daly MJ, Tsao H. Burden of unique and low prevalence somatic mutations correlates with cancer survival. Sci Rep (2019) 9(1):4848. 10.1038/s41598-019-41015-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Li L, Zhang S, Li H, Chou H. FGFR3 promotes the growth and malignancy of melanoma by influencing EMT and the phosphorylation of ERK, AKT, and EGFR. BMC Cancer (2019) 19(1):963. 10.1186/s12885-019-6161-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Guo P, Wang Y, Dai C, Tao C, Wu F, Xie X, et al. Ribosomal protein S15a promotes tumor angiogenesis via enhancing Wnt/beta-catenin-induced FGF18 expression in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncogene (2018) 37(9):1220–36. 10.1038/s41388-017-0017-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mao W, Huang X, Wang L, Zhang Z, Liu M, Li Y, et al. Circular RNA hsa_circ_0068871 regulates FGFR3 expression and activates STAT3 by targeting miR-181a-5p to promote bladder cancer progression. J Exp Clin Cancer Res (2019) 38(1):169. 10.1186/s13046-019-1136-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Liao X, Chen J, Liu Y, He A, Wu J, Cheng J, et al. Knockdown of long noncoding RNA FGFR3- AS1 induces cell proliferation inhibition, apoptosis and motility reduction in bladder cancer. Cancer Biomark (2018) 21(2):277–85. 10.3233/CBM-170354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Shi MJ, Meng XY, Lamy P, Banday AR, Yang J, Moreno-Vega A, et al. APOBEC-mediated Mutagenesis as a Likely Cause of FGFR3 S249C Mutation Over-representation in Bladder Cancer. Eur Urol (2019) 76(1):9–13. 10.1016/j.eururo.2019.03.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Williams SV, Hurst CD, Knowles MA. Oncogenic FGFR3 gene fusions in bladder cancer. Hum Mol Genet (2013) 22(4):795–803. 10.1093/hmg/dds486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pietzak EJ, Bagrodia A, Cha EK, Drill EN, Iyer G, Isharwal S, et al. Next-generation Sequencing of Nonmuscle Invasive Bladder Cancer Reveals Potential Biomarkers and Rational Therapeutic Targets. Eur Urol (2017) 72(6):952–9. 10.1016/j.eururo.2017.05.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Akanksha M, Sandhya S. Role of FGFR3 in Urothelial Carcinoma. Iran J Pathol (2019) 14(2):148–55. 10.30699/ijp.14.2.148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. van Rhijn BWG, Mertens LS, Mayr R, Bostrom PJ, Real FX, Zwarthoff EC, et al. FGFR3 Mutation Status and FGFR3 Expression in a Large Bladder Cancer Cohort Treated by Radical Cystectomy: Implications for Anti-FGFR3 Treatment?. Eur Urol (2020) 78(5):682–7. 10.1016/j.eururo.2020.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kang HW, Kim YH, Jeong P, Park C, Kim WT, Ryu DH, et al. Expression levels of FGFR3 as a prognostic marker for the progression of primary pT1 bladder cancer and its association with mutation status. Oncol Lett (2017) 14(3):3817–24. 10.3892/ol.2017.6621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Knowles MA, Hurst CD. Molecular biology of bladder cancer: new insights into pathogenesis and clinical diversity. Nat Rev Cancer (2015) 15(1):25–41. 10.1038/nrc3817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Tan TZ, Rouanne M, Tan KT, Huang RY, Thiery JP. Molecular Subtypes of Urothelial Bladder Cancer: Results from a Meta-cohort Analysis of 2411 Tumors. Eur Urol (2019) 75(3):423–32. 10.1016/j.eururo.2018.08.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Robertson AG, Kim J, Al-Ahmadie H, Bellmunt J, Guo G, Cherniack AD, et al. Comprehensive Molecular Characterization of Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer. Cell (2017) 171(3):540–56.e25. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.09.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Seiler R, Ashab HAD, Erho N, van Rhijn BWG, Winters B, Douglas J, et al. Impact of Molecular Subtypes in Muscle-invasive Bladder Cancer on Predicting Response and Survival after Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy. Eur Urol (2017) 72(4):544–54. 10.1016/j.eururo.2017.03.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Morales-Barrera R, Suarez C, Gonzalez M, Valverde C, Serra E, Mateo J, et al. The future of bladder cancer therapy: Optimizing the inhibition of the fibroblast growth factor receptor. Cancer Treat Rev (2020) 86:102000. 10.1016/j.ctrv.2020.102000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Milowsky MI, Dittrich C, Martinez ID, Jagdev S, Millard FE, Sweeney C, et al. Final results of a multicenter, open-label phase II trial of dovitinib (TKI258) in patients with advanced urothelial carcinoma with either mutated or nonmutated FGFR3. J Clin Oncol (2013) 31(6_suppl):255–. 10.1200/jco.2013.31.6_suppl.255 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Roskoski R., Jr The role of fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR) protein-tyrosine kinase inhibitors in the treatment of cancers including those of the urinary bladder. Pharmacol Res (2020) 151:104567. 10.1016/j.phrs.2019.104567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Loriot Y, Necchi A, Park SH, Garcia-Donas J, Huddart R, Burgess E, et al. Erdafitinib in Locally Advanced or Metastatic Urothelial Carcinoma. N Engl J Med (2019) 381(4):338–48. 10.1056/NEJMoa1817323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Pal SK, Rosenberg JE, Hoffman-Censits JH, Berger R, Quinn DI, Galsky MD, et al. Efficacy of BGJ398, a Fibroblast Growth Factor Receptor 1-3 Inhibitor, in Patients with Previously Treated Advanced Urothelial Carcinoma with FGFR3 Alterations. Cancer Discov (2018) 8(7):812–21. 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-18-0229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Pal SK, Bajorin D, Dizman N, Hoffman-Censits J, Quinn DI, Petrylak DP, et al. Infigratinib in upper tract urothelial carcinoma versus urothelial carcinoma of the bladder and its association with comprehensive genomic profiling and/or cell-free DNA results. Cancer (2020) 126(11):2597–606. 10.1002/cncr.32806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Schuler M, Cho BC, Sayehli CM, Navarro A, Soo RA, Richly H, et al. Rogaratinib in patients with advanced cancers selected by FGFR mRNA expression: a phase 1 dose-escalation and dose-expansion study. Lancet Oncol (2019) 20(10):1454–66. 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30412-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Liu SB, Lu LF, Lu XB, Li S, Zhang YA. Zebrafish FGFR3 is a negative regulator of RLR pathway to decrease IFN expression. Fish Shellfish Immunol (2019) 92:224–9. 10.1016/j.fsi.2019.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Xie KY, Wang Q, Cao DJ, Liu J, Xie XF. Spinal astrocytic FGFR3 activation leads to mechanical hypersensitivity by increased TNF-alpha in spared nerve injury. Int J Clin Exp Pathol (2019) 12(8):2898–908. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Siemers NO, Holloway JL, Chang H, Chasalow SD, Ross-MacDonald PB, Voliva CF, et al. Genome-wide association analysis identifies genetic correlates of immune infiltrates in solid tumors. PLoS One (2017) 12(7):e0179726. 10.1371/journal.pone.0179726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Chen S, Zhang N, Shao J, Wang T, Wang X. Multi-omics Perspective on the Tumor Microenvironment based on PD-L1 and CD8 T-Cell Infiltration in Urothelial Cancer. J Cancer (2019) 10(3):697–707. 10.7150/jca.28494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Xue Y, Tong L, LiuAnwei Liu F, Liu A, Zeng S, Xiong Q, et al. Tumorinfiltrating M2 macrophages driven by specific genomic alterations are associated with prognosis in bladder cancer. Oncol Rep (2019) 42(2):581–94. 10.3892/or.2019.7196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Wang L, Gong Y, Saci A, Szabo PM, Martini A, Necchi A, et al. Fibroblast Growth Factor Receptor 3 Alterations and Response to PD-1/PD-L1 Blockade in Patients with Metastatic Urothelial Cancer. Eur Urol (2019) 76(5):599–603. 10.1016/j.eururo.2019.06.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Buchtova M, Oralova V, Aklian A, Masek J, Vesela I, Ouyang Z, et al. Fibroblast growth factor and canonical WNT/beta-catenin signaling cooperate in suppression of chondrocyte differentiation in experimental models of FGFR signaling in cartilage. Biochim Biophys Acta (2015) 1852(5):839–50. 10.1016/j.bbadis.2014.12.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Luke JJ, Bao R, Sweis RF, Spranger S, Gajewski TF. WNT/beta-catenin Pathway Activation Correlates with Immune Exclusion across Human Cancers. Clin Cancer Res (2019) 25(10):3074–83. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-1942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Krejci P, Aklian A, Kaucka M, Sevcikova E, Prochazkova J, Masek JK, et al. Receptor tyrosine kinases activate canonical WNT/beta-catenin signaling via MAP kinase/LRP6 pathway and direct beta-catenin phosphorylation. PLoS One (2012) 7(4):e35826. 10.1371/journal.pone.0035826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Palakurthi S, Kuraguchi M, Zacharek SJ, Zudaire E, Huang W, Bonal DM, et al. The Combined Effect of FGFR Inhibition and PD-1 Blockade Promotes Tumor-Intrinsic Induction of Antitumor Immunity. Cancer Immunol Res (2019) 7(9):1457–71. 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-18-0595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Siefker-Radtke AO, Necchi A, Park SH, GarcÃa-Donas JS, Huddart RA, Burgess EF, et al. First results from the primary analysis population of the phase 2 study of erdafitinib (ERDA; JNJ-42756493) in patients (pts) with metastatic or unresectable urothelial carcinoma (mUC) and FGFR alterations (FGFRalt). J Clin Oncol (2018) 36(15_suppl):4503. 10.1200/JCO.2018.36.15_suppl.4503 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Joerger M, Cassier PA, Penel N, Cathomas R, Richly H, Schostak M, et al. Rogaratinib in patients with advanced urothelial carcinomas prescreened for tumor FGFR mRNA expression and effects of mutations in the FGFR signaling pathway. J Clin Oncol (2018) 36(15_suppl):4513–. 10.1200/JCO.2018.36.15_suppl.4513 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Rosenberg JE, Gajate P, Morales-Barrera R, Lee J-L, Necchi A, Penel N, et al. Safety and preliminary efficacy of rogaratinib in combination with atezolizumab in a phase Ib/II study (FORT-2) of first-line treatment in cisplatin-ineligible patients (pts) with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial cancer (UC) and FGFR mRNA overexpression. J Clin Oncol (2020) 38(15_suppl):5014–. 10.1200/JCO.2020.38.15_suppl.5014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]