Abstract

The majority of the tumors arising from the peripheral nerves of the hand are relatively benign. However, a tumor diagnosed as malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (MPNST) has destructive consequences. Clinical signs and symptoms are usually caused by direct and indirect effects of the tumor, such as nerve invasion or compression and infiltration of surrounding tissues. Definitive diagnosis is made by tumor biopsy. Complete surgical removal with maximum reservation of residual neurologic function is the most appropriate intervention for most symptomatic benign peripheral nerve tumors (PNTs) of the hand; however, MPNSTs require surgical resection with a sufficiently wide margin or even amputation to improve prognosis. In this article, we review the clinical presentation and radiographic features, summarize the evidence for an accurate diagnosis, and discuss the available treatment options for PNTs of the hand.

Keywords: Neurofibroma, Neuroma, Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor, Peripheral nerve tumor, Perineurioma, Schwannoma

Core Tip: Tumors located within a peripheral nerve are rare and easily overlooked. In this paper, we review clinical presentation and radiographic features, summarize the evidence for accurate diagnosis, and discuss available treatment options for peripheral nerve tumors arising in the hand.

INTRODUCTION

Tumors located within peripheral nerves are relatively rare and easily overlooked clinically. Of all tumors arising from the hand, peripheral nerve tumors (PNTs) account for less than 5% and are usually categorized based on their benign or malignant features[1-3]. In general, the overwhelming majority of the tumors are benign, while the incidence of malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors (MPNSTs) is extremely low[1,4,5]. To our knowledge, only a few cases of MPNSTs arising from digital nerves have been reported in the literature[6]. Benign lesions arising from the peripheral nerve sheath of the hand mainly include schwannomas, neurofibromas, and perineuriomas. Traumatic neuroma is the most frequently seen lesion in hand surgery. It is not a neoplasm but the proliferative result of nerve repair[7]. More rarely, other benign neoplasms of non-neural sheath origin, such as ganglion cysts, fibrolipomatous hamartomas, and glomus tumors affecting peripheral nerves, should be differentiated from peripheral nerve sheath tumors. In this article, we review various benign and malignant neoplasms and benign neoplasms of non-neural sheath origin of the hand.

The most common presenting complaints of PNTs are soft tissue mass, pain, and sensory loss or weakness in the hand. However, none of these manifestations can particularly suggest one certain type of nerve tumor, nor can they be used as a basis for differential diagnosis with, for example, foreign bony inclusion granuloma, flexor tendon cysts, gang, and mucous cysts. Most benign tumors typically grow slowly and have a long duration, whereas MPNSTs are apt to progress rapidly in terms of lump size, pain degree, and neurologic function deficits[8,9]. On physical assessment, PNTs tend to be movable perpendicular to the axis of the peripheral nerve but are fixed along the axis. Positive Tinel sign of the tumor assists in nerve localization.

Ultrasonography, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are used to evaluate and locate PNTs. MRI is the most useful modality to determine the location of the mass relative to the nerve and to evaluate the extent of involvement of surrounding structures[10]. Although these imaging techniques are less helpful in distinguishing PNTs from other neoplasms, they assist in determining the malignant nature of the tumor, such as large size, invasion into adjacent tissues, and tumor necrosis[11]. Definitive diagnosis for both benign and malignant PNTs is established using microscopic examination, such as histopathological and immunohistochemical analyses.

Management of benign PNTs is based on the signs and symptoms. Appropriate treatment should be applied for symptoms such as pain, disfigurement, or neurologic deficits or suspicion for malignancy, whereas in the absence of symptoms, conservative therapy is sufficient. The careful balance between local tumor removal and minimizing residual neurologic deficits should be achieved in optimal treatment[12]. Most MPNSTs require multidisciplinary approaches to achieve the best treatment for patients, such as irradiation, surgical margins, and amputation[12,13].

BENIGN PERIPHERAL NERVE TUMORS

Schwannoma

Schwannomas, also known as neurilemmomas, are the most common benign tumors of peripheral nerves. They make up about 5% of all benign soft tissue neoplasms, among which 3%-19% develop in the upper limb[14,15]. Schwannomas can occur in people at any age, especially in their 30 s and 60 s, and have no sex predilection[16]. Simultaneous single schwannomas in one nerve are more common than multiple schwannomas in the hand.

Schwannomas usually manifest as solitary, slow-growing, and encapsulated neoplasms and are totally composed of Schwann cells of myelin sheaths[17,18]. The painless lump will persist for a long time before diagnosis, which makes diagnosis and treatment more difficult. Meanwhile, it may be misdiagnosed as neurofibroma or ganglion of the hand. As the tumor grows larger and gradually compresses the involved nerve, pain, paresthesia, and other symptoms may appear accordingly[19]. However, the size of most schwannomas does not exceed 3 cm in diameter[20,21].

Clinically, MRI and ultrasonography can help diagnose and localize these tumors[22]. On MRI (Figure 1), schwannomas show low signal intensity on T1-weighted (T1W) and high signal intensity on T2-weighted (T2W)[14]. An accordant enhancement and eccentric placement of the nerve can distinguish schwannoma from neurofibromas. The biphasic structures, such as Antoni A (dense) and Antoni B (loose), are typical pathological features of schwannoma, along with nuclear palisading and strong S100 protein positivity (Figure 2). To ensure optimum efficiency of nerve recovery and reduce unnecessary damage to vital nerve fascicles, careful planning with accurate diagnosis before operation is helpful (Figure 3)[15,23]. In terms of prognosis, the disease is usually curative after surgical removal.

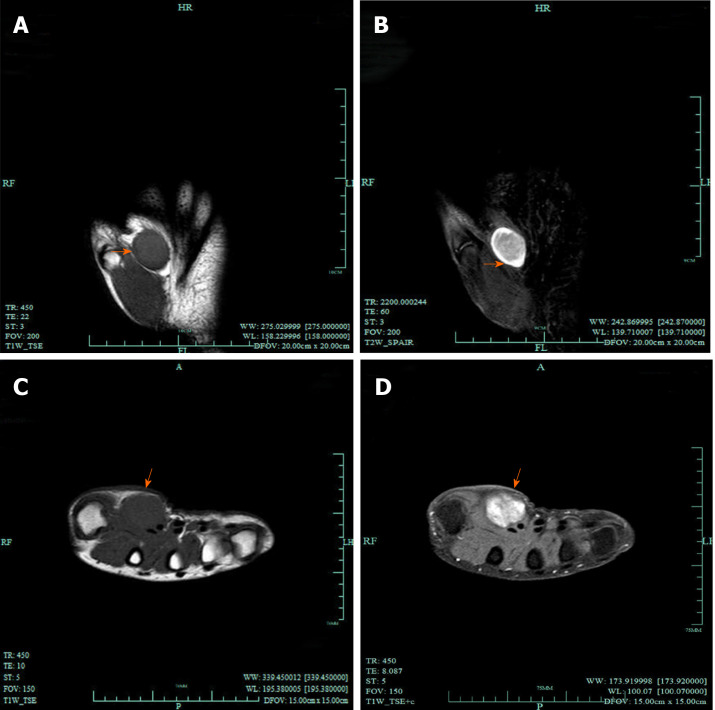

Figure 1.

Magnetic resonance imaging of schwannomas. A, B: Coronal magnetic resonance images; T1-weighted image (A) demonstrated a nodule of low intensity signal (arrows), while on T2-weighted image (B) it presented as high signal (arrows); C, D: Transverse magnetic resonance images; C: T1-weighted image; D: The lesions show significant enhancement after administration of contrast agent (arrows).

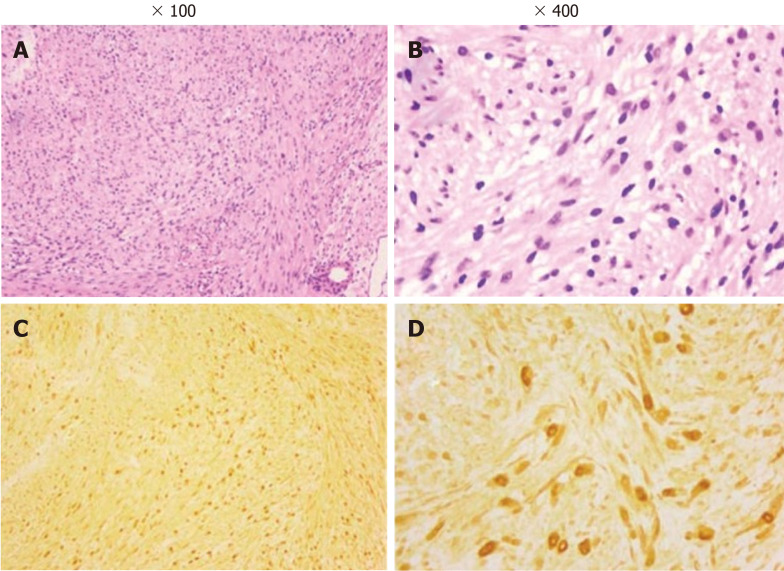

Figure 2.

Photomicrograph of the tumors. A and B: Pathological examination shows a biphasic architecture of Antoni A (dense) and Antoni B (loose) and nuclei palisading with multiple fascicles (hematoxylin and eosin); C and D: The tumor cells stain positive for S100 protein. Adapted with permission from Jiang S, Shen H, and Lu H. Multiple schwannomas of the digital nerves and common palmar digital nerves: An unusual case report of multiple schwannomas in one hand. Medicine (Baltimore) 2019; 98: e14605.

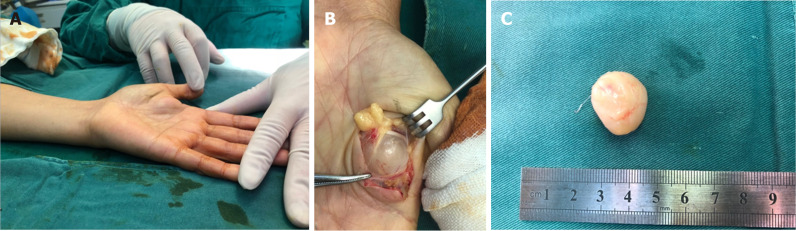

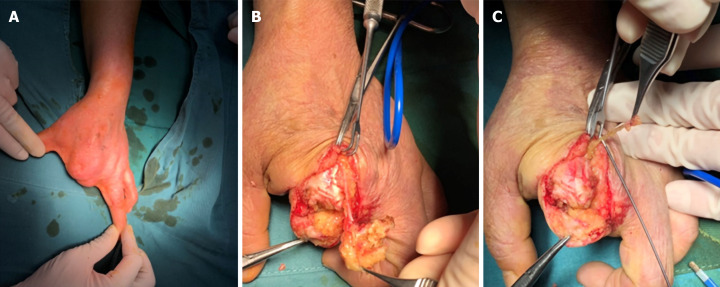

Figure 3.

Schwannomas. A: A solitary, palpable lesion on the volar of the left hand; B: A solitary, encapsulated well-defined surface of schwannomas involving the median nerve branch was found during operation; C: The lesion, of 22 mm in diameter, was removed carefully without damaging the nerve. Courtesy of Lu Hui, Orthopedics, The First Affiliated Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China.

Neurofibroma

Neurofibromas are also relatively common benign peripheral nerve sheath tumors. They often consist of a mixed population of Schwann cells, fibroblasts, and perineurial-like cells scattered within the myxoid matrix, nerve fibers, and collagen fibers, with the neoplastic cell originating from Schwann cells[11,24]. It is clinically important for surgeons to distinguish between schwannomas and neurofibromas, and the difference is that the latter have intratumor nerve fibers. Neurofibromas can be classified into four subtypes according to their anatomic localization and gross appearance, namely, plexiform neurofibromas, cutaneous neurofibromas, intraneural neurofibromas, and massive soft tissue neurofibromas[25]. Among them, localized cutaneous neurofibromas are the most common type.

Neurofibromas are usually found in the young population, especially in 20–30-year-old individuals, without gender bias. They are typically painless and slow-growing masses. The lesions mostly originate from the branches of the nerves; and, therefore, almost all of them exist in shallow locations.

When diagnosed as neurofibroma, schwannoma should be ruled out first. On MRI, both lesions present as well-defined fusiform masses that rarely exceed 5 cm in diameter[26]. However, neurofibromas can be distinguished from schwannomas based on the location of the tumors. Schwannomas are eccentric relative to the nerve, whereas neurofibromas are concentric. In general, pathological examination is definitely the gold standard to diagnose neurofibromas. Histologically, they are composed of elongated Schwann cells, fibroblasts, and perineurial-like cells intermixed with undulating bundles of nerve fibers, collagen, and mucin. Immunohistochemical stains are also applied to make a definite diagnosis. Neurofibromas will show positive S100, which is less pronounced than in schwannomas. The perineurium surrounding the tumor can be stained by epithelial membrane antigen so that the neurofilament can highlight the entrapped neuronal processes[27].

Treatment options for neurofibromas depend on subtypes, signs, and symptoms. Cutaneous neurofibromas should not be resected unless there are symptoms of pain, bleeding, functional defect, or impairment of appearance. Asymptomatic solitary intraneural neurofibromas can be managed by regular follow-up. Surgical resection is necessary for patients who experience intolerable pain or progressive neurologic function deficits or if the diagnosis is uncertain or when malignancy is suspected. For patients in need of treatment, surgical resection with preserved nerve function and no recurrence is the goal we should try our best to achieve.

Clinically, most neurofibromas occur in isolation, of which only about 10% may be associated with neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1)[28]. NF1, also known as von Recklinghausen disease, is an autosomal dominant genetic disorder[29]. It is the most common type of neurofibromatosis with incidence of 1/3000 to 1/2600[30,31]. Half of NF1 patients have a family history, whereas others have personal genetic mutation[32,33]. It is usually characterized as Lisch nodules that are also called iris hamartomas, axillary or inguinal freckles, café-au-lait macules, and tumors. The morbidity of both benign and malignant tumors will increase over the lifetime in patients with NF1[34,35]. Generally, neurofibromas are the most common type of benign tumors in patients with NF1. As for the treatment of tumors in patients with NF1, an optimal plan according to the different tumor pathologies should be carefully formulated, and the details are presented in sections of this article (Figure 4).

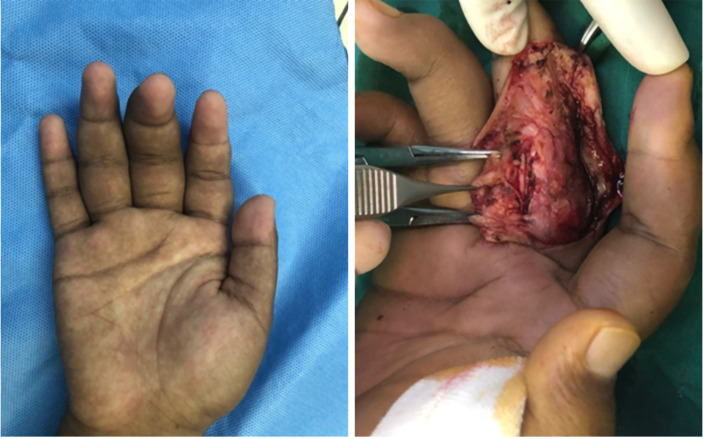

Figure 4.

Neurofibromatosis type 1 patient with neurofibromas on the radius of the right middle finger underwent surgical operation. Adapted with permission from Lu H, Chen Q, and Shen H. Hamartoma compress medial and radial nerve in neurofibromatosis type 1. Int J Clin Exp Med 2015; 8: 15313-15316.

Perineurioma

Perineuriomas are benign tumors that are entirely composed of perineurial cells. They are classified into two types, the most common type of which is soft tissue perineurioma, whereas intraneural perineurioma is rare[36]. Intraneural perineuriomas are usually described as solitary and locally expensed peripheral nerves, whereas soft tissue perineurioma is not associated with nerves[37,38]. Although they are clinically distinct, pathologically both of them express clonal monosomy for chromosome 22, which indicates the same neoplastic origin. Researches have indicated that about 60% of the perineuriomas have mutations in tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 7[39].

Soft tissue extraneural perineuriomas are more common in middle-aged people and have a slight predominance in women[40]. Because the tumor has no clear association with any nerve, a painless and slow-growing mass in the extremities may be the only clinical manifestation. On gross examination, well-defined white-tan rubbery nodules will be found. Histological findings are slender cells with very delicate and overlapping elongated cellular processes arranged in loose fascicles or whorls. Surgical excision is the preferred option for soft tissue extraneural perineuriomas with little possibility of recurrence or neurologic injury.

Intraneural perineuriomas are rare lesions with similar features as schwannomas[41]. They usually affect adults aged 20 to 40 years, and the commonly involved locations are radial, ulnar, and median nerves of the upper limb[42,43]. The tumor usually grows slowly along the involved nerve; therefore, patients always come to the clinic with complaints of weakness, sensory loss, and consecutive muscle atrophy. In terms of imaging, thickened and continuous fascicular architecture will be found on MRI, and most lesions will show low to moderate signal intensity on T1W, but abnormal high signal intensity on T2W, enhanced by intravenous contrast administration[44].

Grossly intraneural perineuriomas show multiple nodes secondary to firm, enlarged nerve fascicles. Microscopic findings are proliferating perineural cells organized in concentric layers around the centric axon, forming a pseudo-onion bulb structure on transverse sections[45,46].

In the presence of pain or neurologic injury, surgical excision should be the main treatment with extremely low risk of recurrence. As axons pass through the tumor, residual nerve dysfunction may occur.

BENIGN NEOPLASMS OF NON-NEURAL SHEATH ORIGIN

Neuroma

Neuroma is a type of reactive PNT that often occurs after disruption of axons or nerve, such as amputation, laceration, compression or transection injuries, compression of local tissues, or even microtrauma caused by stretching or surgery in soft tissues[7,47]. Successful nerve regeneration requires the adjacency of two split nerve ends and unobstructed access for growing axons, whereas neurotmesis leads to lack of endoneurial tube and a massive collection of disorganized nerve tissues that gradually develop along the injured nerve or just at the proximal end of the transected nerve[48,49]. Moreover, the simultaneous effect of signaling molecules and wound-repairing cells can lead to collagen remodeling and scar formation, resulting in the eventual formation of neuromas that are composed of poorly vascularized dense fibrous structures[50].

Neuromas usually present as small, firm, and painful nodules and can lead to sensorimotor deficits. They are hardly larger than 5 cm in diameter[51]. MRI and ultrasonography can help to diagnose, but more importantly, the history of trauma or surgery should not be ignored.

Many options are available for treating painful neuromas. To help ease the pain, pharmacological treatments are used to inhibit pain-signaling pathways; therefore, drugs such as N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonists, anticonvulsants, opioids, local anesthetics, antidepressants, and calcitonin can be selected[52,53]. However, factors such as adverse effects of the drugs, pain level, and route of administration should be taken into consideration before drug selection. Invasive treatment is the first choice for removal of neuromas, such as surgical neuroma resection[54]. However, in some certain cases, external or internal neurolysis is already sufficient[55]. In cases of complete transection, unless the nerve is not essential, nerve grafting or reconstruction may be indispensable (Figure 5)[56]. To deal with cases of unimportant nerve transection, we can choose to embed the proximal end into nearby soft tissues, muscles, or even bone marrow to reduce external stimulation and decrease the possibility of recurrence. The combination of these multiple skills has more advantages in treating peripheral nerve injuries, relieving pain, decreasing rate of tumor recurrence, and diminishing phantom symptoms compared with simple neurectomy. All things considered, a rational preoperative plan and careful surgical techniques are necessary to achieve the best result in removing the tumor and preventing recurrence. Although treatments mentioned previously have already achieved a certain degree of success, the results still fall short of our expectations, and some patients still suffer from side effects caused by operation and painful neuromas (Figure 6).

Figure 5.

Neuroma. A: Partial rupture of the median nerve with neuroma formation in the right hand; B and C: Surgical neuroma resection with nerve grafting was performed in this patient. Courtesy of Lu Hui, Orthopedics, The First Affiliated Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China.

Figure 6.

Digital nerve neuromas. A: A patient with amputation of the second and third fingers suffered neuralgia; B and C: Digital nerve neuromas were found and neurectomy with radiofrequency ablation was performed to decrease the possibility of recurrence. Courtesy of Lu Hui, Orthopedics, The First Affiliated Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China.

Other benign neoplasms of non-neural sheath origin

A nerve sheath ganglion is a cyst of nerve origin that is filled with mucin. Most ganglion cysts occur in proximity to tendons or joints, which suggests that they develop from local mechanical irritation or injury to perineural tissues. The main nerve in which these lesions occur is common peroneal nerve close to the knee[57]. Ganglion cysts located in the upper extremity are rarely reported, and there are a few cases of nerve sheath ganglion involving the ulnar, median, and radial nerves[58-64]. When ganglion cysts cause intra- or extraneural compression, typical symptoms are pain, weakness, and/or loss of sensation. Resection with careful protection of vital nerve fascicles is the main therapy in patients with presenting signs and symptoms (Figure 7)[12].

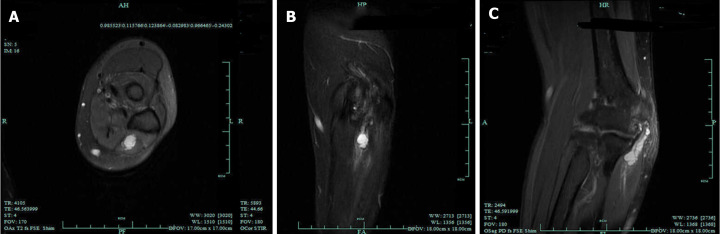

Figure 7.

Magnetic resonance imaging of intraneural ganglion cyst of the ulnar nerve. A: Hyperintense lesion in the ulnar nerve on T2-weighted (T2W) in transverse section; B: Hyperintense lesion in the ulnar nerve on T2W in coronal section; C: Hyperintense beaded lesion in the ulnar nerve on T2W in median sagittal section. Adapted with permission from Li P, Lou D, and Lu H. The cubital tunnel syndrome caused by intraneural ganglion cyst of the ulnar nerve at the elbow: a case report. BMC neurology 2018; 18: 217.

Fibrolipomatous hamartoma, also known as neural fibrolipoma, is a benign tumor-like process with adipose and fibrous infiltrations into the epineurium and perineural tissue[65,66]. It is indeed an unusual condition that most commonly involves the median, ulnar, or digital nerve in children and adolescents. Sometimes it can be noticed at birth because of the association with macrodactyly caused by the overgrowth of distal bone and soft tissue. Patients present with pain, numbness, paresthesia, and loss of sensation and strength owing to nerve compression by the slow-growing mass. The signs and symptoms of carpal tunnel syndrome most likely occur when the distal median nerve is involved[3]. On MRI, nerve fascicle enlargement surrounded by hyperintense fat on T1W sequences is the typical imaging feature of this disease. Surgical debulking or carpal tunnel release results in good outcomes and low possibility of recurrence.

Glomus tumors are benign neoplasms arising from glomus bodies and account for 5% of tumors in the hand; glomus tumors of peripheral nerves are rare[67,68]. Intraneural glomus tumors are extremely rare, and to our knowledge, only several cases have been reported[69-76]. Tingling sensation, numbness, point tenderness, and paresthesia are the presenting manifestations, and no loss of strength has been found in these cases. MRI and ultrasonography assist in locating the tumor and planning surgical excision (Figure 8)[70]. Surgical excision with careful preservation of nerve fascicles can relieve symptoms in most patients, and microsurgical technique aids in the process of precise tumor dissection (Figure 9).

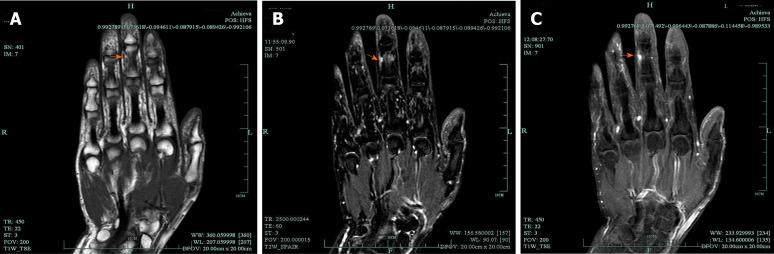

Figure 8.

Magnetic resonance imaging of multiple intraneural glomus tumors in the digital nerve. A: A hyperintense signal on T1-weighted; B: A hyperintense signal on T2-weighted; C: Contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging showing a significantly enhanced signal. Adapted with permission from Wang Y and Lu H, Multiple intraneural glomus tumors in different digital nerve fascicles. BMC Cancer 2019; 19: 888.

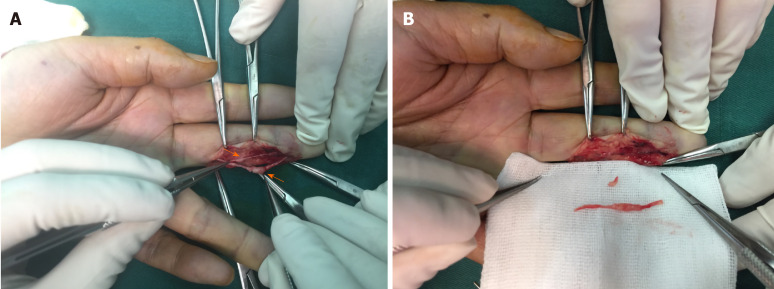

Figure 9.

Two lesions in the digit nerve and multiple intraneural glomus tumors. A and B: Two lesions in the digit nerve were found during the operation and complete resection of multiple intraneural glomus tumors was performed in this case. Adapted with permission from Wang Y and Lu H, Multiple intraneural glomus tumors in different digital nerve fascicles. BMC Cancer 2019; 19: 888.

MALIGNANT PERIPHERAL NERVE SHEATH TUMORS

Generally, we classify MPNSTs as malignant soft tissue sarcomas. Although they are really rare tumors, they cause destructive consequences[77]. They can originate from peripheral nerves or extraneural soft tissues and manifest as nerve sheath differentiation. MPNSTs mostly occur in 20-50-year-old individuals[5,78], and 22%-50% of MPNSTs occur in patients with NF1. About 8%–13% of patients with NF1 are diagnosed with MPNSTs[35,79]. Half of the lesions are caused by malignant transformation of preexisting neurofibromas, whereas others develop by themselves[80]. MPNSTs mostly occur in the proximal upper or lower extremities and the trunk, and the major nerve trunks are commonly involved, whereas the originating nerves are often not.

Most MPNSTs present with potentially painful, rapidly enlarging lumps closely related to major nerves, and the tumors are apt to spread along the distal and proximal perineural and epineural tissue[81]. MRI can help with diagnosis and localize the tumors. Signs such as tumor size exceeding 5 cm, unclear boundaries, significant heterogeneity, fat infiltration, and surrounding edema are suggestive of malignant neoplasms[26,82]. Positron emission tomography/CT also assists in differentiating MPNSTs from benign tumors and evaluating systemic metastases[83]. Biopsy is well known as the most accurate method for diagnosis. Grossly, MPNSTs are mostly large and firm tumors with intratumor hemorrhage and partial necrosis. Under electron microscope, MPNSTs are typically characterized by highly cellular areas, consisting of spindle cells similar to Schwann cells[84]. These malignant tumor cells perform active mitosis and, immunohistochemically, are weakly positive for S100[85].

In general, we stage and treat MPNSTs as malignant soft tissue sarcomas[86]. For primary tumors of the limbs, surgical resection alone with a wide margin is usually insufficient, whereas amputation of the limb proximal to the tumor may be necessary[87]. In some cases, neoadjuvant radiotherapy (RT) can provide an opportunity for limb preservation, and postoperative adjuvant RT can decrease the rate of local recurrence in patients who cannot attain wide excision margins by surgery alone[87-89].

Despite appropriate surgery and RT, the prognosis of MPNSTs remains unsatisfactory. Signs such as size of > 5 cm, higher tumor grade, relation to NF1, old age, distant metastasis, and positive margins are predictive of bad outcomes[5].

CONCLUSION

A diversity of PNTs may involve the hand and the wrist. Compared with other body parts, the morbidity is relatively low, and fortunately, most of the tumors are benign. Signs and symptoms usually result from direct or indirect effects of the tumor to surrounding tissues and nerves. Masses, pain, sensory loss, and weakness of the hand are the most common symptoms, similar to the manifestations of many common diseases of hand. On examination, PNTs tend to be movable perpendicular to the axis of the peripheral nerve but fixed along the axis. Imaging examinations, especially MRI, are most commonly used to evaluate and localize PNTs, determine whether or not it is intrinsic to the nerve, and delineate involvement of adjacent structures. Positron emission tomography/CT can help differentiate MPNSTs from benign tumors and evaluate for systemic metastases[90]. Definitive diagnosis for both benign and malignant PNTs depends on microscopic examination, such as histopathological and immunohistochemical analyses. When dealing with benign PNTs, signs and symptoms of the patients should be taken into consideration. Asymptomatic non-neoplastic lumps or benign tumors can be treated conservatively, whereas patients with symptoms such as disfigurement, neurologic deficit, or intolerable pain or with suspicion for malignancy require early treatment. The goal of treatment is complete surgical removal with maximum reservation of residual neurologic function. For MPNSTs, simple surgical resection with a sufficiently wide margin combining RT plays an integral role in the current management, contributing to overall increased survival rates.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Peer-review started: May 20, 2020

First decision: September 14, 2020

Article in press: September 25, 2020

Specialty type: Oncology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Jun YM, Malik H S-Editor: Zhang H L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Ma YJ

Contributor Information

Hai-Ying Zhou, Department of Orthopedics, The First Affiliated Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou 310003, Zhejiang Province, China.

Shuai Jiang, Department of Orthopedics, The First Affiliated Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou 310003, Zhejiang Province, China.

Fei-Xia Ma, Department of Breast Surgery, The First Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang Chinese Medical University, Hangzhou 310000, Zhejiang Province, China.

Hui Lu, Department of Orthopedics, The First Affiliated Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou 310003, Zhejiang Province, China. huilu@zju.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Sandberg K, Nilsson J, Søe Nielsen N, Dahlin LB. Tumours of peripheral nerves in the upper extremity: a 22-year epidemiological study. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg. 2009;43:43–49. doi: 10.1080/02844310802489079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hsu CS, Hentz VR, Yao J. Tumours of the hand. Lancet Oncol. 2007;8:157–166. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70035-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marty FL, Marteau E, Rosset P, Faizon G, Laulan J. [A retrospective study of hand and wrist tumors in adults] Chir Main. 2010;29:183–187. doi: 10.1016/j.main.2010.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Forthman CL, Blazar PE. Nerve tumors of the hand and upper extremity. Hand Clin. 2004;20:233–242, v. doi: 10.1016/j.hcl.2004.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Farid M, Demicco EG, Garcia R, Ahn L, Merola PR, Cioffi A, Maki RG. Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors. Oncologist. 2014;19:193–201. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2013-0328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mitchell CH, Fayad LM, Ahlawat S. Magnetic Resonance Imaging of the Digital Nerves of the Hand: Anatomy and Spectrum of Pathology. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 2018;47:42–50. doi: 10.1067/j.cpradiol.2017.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oliveira KMC, Pindur L, Han Z, Bhavsar MB, Barker JH, Leppik L. Time course of traumatic neuroma development. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0200548. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0200548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perrin RG, Guha A. Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2004;15:203–216. doi: 10.1016/j.nec.2004.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Valeyrie-Allanore L, Ismaïli N, Bastuji-Garin S, Zeller J, Wechsler J, Revuz J, Wolkenstein P. Symptoms associated with malignancy of peripheral nerve sheath tumours: a retrospective study of 69 patients with neurofibromatosis 1. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:79–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06558.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nilsson J, Sandberg K, Søe Nielsen N, Dahlin LB. Magnetic resonance imaging of peripheral nerve tumours in the upper extremity. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg. 2009;43:153–159. doi: 10.1080/02844310902734572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pilavaki M, Chourmouzi D, Kiziridou A, Skordalaki A, Zarampoukas T, Drevelengas A. Imaging of peripheral nerve sheath tumors with pathologic correlation: pictorial review. Eur J Radiol. 2004;52:229–239. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2003.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lai CS, Chen IC, Lan HC, Lu CT, Yen JH, Song DY, Tang YW. Management of extremity neurilemmomas: clinical series and literature review. Ann Plast Surg. 2013;71 Suppl 1:S37–S42. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0000000000000042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hung YW, Tse WL, Cheng HS, Ho PC. Surgical excision for challenging upper limb nerve sheath tumours: a single centre retrospective review of treatment results. Hong Kong Med J. 2010;16:287–291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jiang S, Shen H, Lu H. Multiple schwannomas of the digital nerves and common palmar digital nerves: An unusual case report of multiple schwannomas in one hand. Medicine (Baltimore) 2019;98:e14605. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000014605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adani R, Baccarani A, Guidi E, Tarallo L. Schwannomas of the upper extremity: diagnosis and treatment. Chir Organi Mov. 2008;92:85–88. doi: 10.1007/s12306-008-0049-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adani R, Tarallo L, Mugnai R, Colopi S. Schwannomas of the upper extremity: analysis of 34 cases. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2014;156:2325–2330. doi: 10.1007/s00701-014-2218-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Funata N. [Tumors(4), Pathology of tumours of the peripheral nerves, pituitary gland and benign epithelial cysts. No. 12 in series of articles: basic knowledge of neuropathology for neurosurgeons] No Shinkei Geka. 2003;31:683–690. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hébert-Blouin MN, Amrami KK, Scheithauer BW, Spinner RJ. Multinodular/plexiform (multifascicular) schwannomas of major peripheral nerves: an underrecognized part of the spectrum of schwannomas. J Neurosurg. 2010;112:372–382. doi: 10.3171/2009.5.JNS09244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fanburg-Smith JC, Majidi M, Miettinen M. Keratin expression in schwannoma; a study of 115 retroperitoneal and 22 peripheral schwannomas. Mod Pathol. 2006;19:115–121. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kang HJ, Shin SJ, Kang ES. Schwannomas of the upper extremity. J Hand Surg Br. 2000;25:604–607. doi: 10.1054/jhsb.2000.0472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aslam N, Kerr G. Multiple schwannomas of the median nerve: a case report and literature review. Hand Surg. 2003;8:249–252. doi: 10.1142/s0218810403001741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hems TE, Burge PD, Wilson DJ. The role of magnetic resonance imaging in the management of peripheral nerve tumours. J Hand Surg Br. 1997;22:57–60. doi: 10.1016/s0266-7681(97)80018-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sá Â, Nobre Azevedo L, Cunha L. [Schwannoma of the Upper Extremity: Retrospective Analysis of 17 Cases] Acta Med Port. 2016;29:519–524. doi: 10.20344/amp.6906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zheng H, Chang L, Patel N, Yang J, Lowe L, Burns DK, Zhu Y. Induction of abnormal proliferation by nonmyelinating schwann cells triggers neurofibroma formation. Cancer Cell. 2008;13:117–128. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu J, Williams JP, Rizvi TA, Kordich JJ, Witte D, Meijer D, Stemmer-Rachamimov AO, Cancelas JA, Ratner N. Plexiform and dermal neurofibromas and pigmentation are caused by Nf1 loss in desert hedgehog-expressing cells. Cancer Cell. 2008;13:105–116. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.12.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wasa J, Nishida Y, Tsukushi S, Shido Y, Sugiura H, Nakashima H, Ishiguro N. MRI features in the differentiation of malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors and neurofibromas. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;194:1568–1574. doi: 10.2214/AJR.09.2724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jokinen CH, Dadras SS, Goldblum JR, van de Rijn M, West RB, Rubin BP. Diagnostic implications of podoplanin expression in peripheral nerve sheath neoplasms. Am J Clin Pathol. 2008;129:886–893. doi: 10.1309/M7D5KTVYYE51XYQA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beert E, Brems H, Daniëls B, De Wever I, Van Calenbergh F, Schoenaers J, Debiec-Rychter M, Gevaert O, De Raedt T, Van Den Bruel A, de Ravel T, Cichowski K, Kluwe L, Mautner V, Sciot R, Legius E. Atypical neurofibromas in neurofibromatosis type 1 are premalignant tumors. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2011;50:1021–1032. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carroll SL. Molecular mechanisms promoting the pathogenesis of Schwann cell neoplasms. Acta Neuropathol. 2012;123:321–348. doi: 10.1007/s00401-011-0928-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Le LQ, Shipman T, Burns DK, Parada LF. Cell of origin and microenvironment contribution for NF1-associated dermal neurofibromas. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4:453–463. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hummel TR, Jessen WJ, Miller SJ, Kluwe L, Mautner VF, Wallace MR, Lázaro C, Page GP, Worley PF, Aronow BJ, Schorry EK, Ratner N. Gene expression analysis identifies potential biomarkers of neurofibromatosis type 1 including adrenomedullin. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:5048–5057. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rodriguez FJ, Stratakis CA, Evans DG. Genetic predisposition to peripheral nerve neoplasia: diagnostic criteria and pathogenesis of neurofibromatoses, Carney complex, and related syndromes. Acta Neuropathol. 2012;123:349–367. doi: 10.1007/s00401-011-0935-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Naber U, Friedrich RE, Glatzel M, Mautner VF, Hagel C. Podoplanin and CD34 in peripheral nerve sheath tumours: focus on neurofibromatosis 1-associated atypical neurofibroma. J Neurooncol. 2011;103:239–245. doi: 10.1007/s11060-010-0385-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miller SJ, Jessen WJ, Mehta T, Hardiman A, Sites E, Kaiser S, Jegga AG, Li H, Upadhyaya M, Giovannini M, Muir D, Wallace MR, Lopez E, Serra E, Nielsen GP, Lazaro C, Stemmer-Rachamimov A, Page G, Aronow BJ, Ratner N. Integrative genomic analyses of neurofibromatosis tumours identify SOX9 as a biomarker and survival gene. EMBO Mol Med. 2009;1:236–248. doi: 10.1002/emmm.200900027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Salamon J, Mautner VF, Adam G, Derlin T. Multimodal Imaging in Neurofibromatosis Type 1-associated Nerve Sheath Tumors. Rofo. 2015;187:1084–1092. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1553505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Payne WT, Merrell G. Benign bony and soft tissue tumors of the hand. J Hand Surg Am. 2010;35:1901–1910. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2010.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hornick JL, Fletcher CD. Soft tissue perineurioma: clinicopathologic analysis of 81 cases including those with atypical histologic features. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:845–858. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000155166.86409.d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Restrepo CE, Amrami KK, Howe BM, Dyck PJ, Mauermann ML, Spinner RJ. The almost-invisible perineurioma. Neurosurg Focus. 2015;39:E13. doi: 10.3171/2015.6.FOCUS15225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hornick JL, Bundock EA, Fletcher CD. Hybrid schwannoma/perineurioma: clinicopathologic analysis of 42 distinctive benign nerve sheath tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:1554–1561. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181accc6c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gu HY, Wei ZM, Lin DL, Zhao H, Hao FY. Soft tissue perineurioma with peripheral lymphoid cuff of the tongue: a case report and literature review. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2014;7:323–326. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee HY, Manasseh RG, Edis RH, Page R, Keith-Rokosh J, Walsh P, Song S, Laycock A, Griffiths L, Fabian VA. Intraneural perineurioma. J Clin Neurosci. 2009;16:1633–1636. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2009.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mauermann ML, Amrami KK, Kuntz NL, Spinner RJ, Dyck PJ, Bosch EP, Engelstad J, Felmlee JP, Dyck PJ. Longitudinal study of intraneural perineurioma--a benign, focal hypertrophic neuropathy of youth. Brain. 2009;132:2265–2276. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.León Cejas L, Binaghi D, Socolovsky M, Dubrovsky A, Pirra L, Marchesoni C, Pardal A, Monges S, Peretti G, Taratuto AL, Lubinieki F, Reisin R. Intraneural perineuriomas: diagnostic value of magnetic resonance neurography. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2018;23:23–28. doi: 10.1111/jns.12240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.De Smet K, De Maeseneer M, Talebian Yazdi A, Stadnik T, De Mey J. MRI in hypertrophic mono- and polyneuropathies. Clin Radiol. 2013;68:317–322. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2012.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rankine AJ, Filion PR, Platten MA, Spagnolo DV. Perineurioma: a clinicopathological study of eight cases. Pathology. 2004;36:309–315. doi: 10.1080/00313020410001721663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Klein CJ, Wu Y, Jentoft ME, Mer G, Spinner RJ, Dyck PJ, Dyck PJ, Mauermann ML. Genomic analysis reveals frequent TRAF7 mutations in intraneural perineuriomas. Ann Neurol. 2017;81:316–321. doi: 10.1002/ana.24854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Buchheit T, Van de Ven T, Hsia HL, McDuffie M, MacLeod DB, White W, Chamessian A, Keefe FJ, Buckenmaier CT, Shaw AD. Pain Phenotypes and Associated Clinical Risk Factors Following Traumatic Amputation: Results from Veterans Integrated Pain Evaluation Research (VIPER) Pain Med. 2016;17:149–161. doi: 10.1111/pme.12848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wood MD, Mackinnon SE. Pathways regulating modality-specific axonal regeneration in peripheral nerve. Exp Neurol. 2015;265:171–175. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2015.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Faroni A, Mobasseri SA, Kingham PJ, Reid AJ. Peripheral nerve regeneration: experimental strategies and future perspectives. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2015;82-83:160–167. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2014.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Egami S, Tanese K, Honda H, Kasai H, Yokoyama T, Sugiura M. Traumatic neuroma on the digital tip: Immunohistochemical analysis of inflammatory signaling pathways. J Dermatol. 2016;43:836–837. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.13297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kang J, Yang P, Zang Q, He X. Traumatic neuroma of the superficial peroneal nerve in a patient: a case report and review of the literature. World J Surg Oncol. 2016;14:242. doi: 10.1186/s12957-016-0990-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Economides JM, DeFazio MV, Attinger CE, Barbour JR. Prevention of Painful Neuroma and Phantom Limb Pain After Transfemoral Amputations Through Concomitant Nerve Coaptation and Collagen Nerve Wrapping. Neurosurgery. 2016;79:508–513. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0000000000001313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yan H, Zhang F, Kolkin J, Wang C, Xia Z, Fan C. Mechanisms of nerve capping technique in prevention of painful neuroma formation. PLoS One. 2014;9:e93973. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0093973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pet MA, Ko JH, Friedly JL, Mourad PD, Smith DG. Does targeted nerve implantation reduce neuroma pain in amputees? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472:2991–3001. doi: 10.1007/s11999-014-3602-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mrowczynski O, Mau C, Nguyen DT, Sarwani N, Rizk E, Harbaugh K. Percutaneous Radiofrequency Ablation for the Treatment of Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumors: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Cureus. 2018;10:e2534. doi: 10.7759/cureus.2534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yao C, Zhou X, Zhao B, Sun C, Poonit K, Yan H. Treatments of traumatic neuropathic pain: a systematic review. Oncotarget. 2017;8:57670–57679. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.16917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lu H, Chen L, Jiang S, Shen H. A rapidly progressive foot drop caused by the posttraumatic Intraneural ganglion cyst of the deep peroneal nerve. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2018;19:298. doi: 10.1186/s12891-018-2229-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Li P, Lou D, Lu H. The cubital tunnel syndrome caused by intraneural ganglion cyst of the ulnar nerve at the elbow: a case report. BMC Neurol. 2018;18:217. doi: 10.1186/s12883-018-1229-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chang WK, Li YP, Zhang DF, Liang BS. The cubital tunnel syndrome caused by the intraneural or extraneural ganglion cysts: Case report and review of the literature. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2017;70:1404–1408. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2017.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yahya A, Malarkey AR, Eschbaugh RL, Bamberger HB. Trends in the Surgical Treatment for Cubital Tunnel Syndrome: A Survey of Members of the American Society for Surgery of the Hand. Hand (N Y) 2018;13:516–521. doi: 10.1177/1558944717725377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mobbs RJ, Phan K, Maharaj MM, Chaganti J, Simon N. Intraneural Ganglion Cyst of the Ulnar Nerve at the Elbow Masquerading as a Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumor. World Neurosurg 2016; 96: 613.e5-613. :e8. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2016.08.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chen WA, Barnwell JC, Li Y, Smith BP, Li Z. An ulnar intraneural ganglion arising from the pisotriquetral joint: case report. J Hand Surg Am. 2011;36:65–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2010.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Colbert SH, Le MH. Case report: intraneural ganglion cyst of the ulnar nerve at the wrist. Hand (N Y) 2011;6:317–320. doi: 10.1007/s11552-011-9329-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Spinner RJ, Wang H, Howe BM, Colbert SH, Amrami KK. Deep ulnar intraneural ganglia in the palm. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2012;154:1755–1763. doi: 10.1007/s00701-012-1422-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Spinner RJ, Scheithauer BW, Amrami KK, Wenger DE, Hébert-Blouin MN. Adipose lesions of nerve: the need for a modified classification. J Neurosurg. 2012;116:418–431. doi: 10.3171/2011.8.JNS101292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rodriguez FJ, Erickson-Johnson MR, Scheithauer BW, Spinner RJ, Oliveira AM. HMGA2 rearrangements are rare in benign lipomatous lesions of the nervous system. Acta Neuropathol. 2008;116:337–338. doi: 10.1007/s00401-008-0412-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Scheithauer BW, Rodriguez FJ, Spinner RJ, Dyck PJ, Salem A, Edelman FL, Amrami KK, Fu YS. Glomus tumor and glomangioma of the nerve. Report of two cases. J Neurosurg. 2008;108:348–356. doi: 10.3171/JNS/2008/108/2/0348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gombos Z, Zhang PJ. Glomus tumor. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2008; 132: 1448-1452 [PMID: 18788860 DOI: 10. :1043/1543–2165(2008)132. doi: 10.5858/2008-132-1448-GT. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Brems H, Park C, Maertens O, Pemov A, Messiaen L, Upadhyaya M, Claes K, Beert E, Peeters K, Mautner V, Sloan JL, Yao L, Lee CC, Sciot R, De Smet L, Legius E, Stewart DR. Glomus tumors in neurofibromatosis type 1: genetic, functional, and clinical evidence of a novel association. Cancer Res. 2009;69:7393–7401. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wang Y, Lu H. Multiple intraneural glomus tumors in different digital nerve fascicles. BMC Cancer. 2019;19:888. doi: 10.1186/s12885-019-6098-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kline SC, Moore JR, deMente SH. Glomus tumor originating within a digital nerve. J Hand Surg Am. 1990;15:98–101. doi: 10.1016/s0363-5023(09)91114-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Calonje E, Fletcher CD. Cutaneous intraneural glomus tumor. Am J Dermatopathol. 1995;17:395–398. doi: 10.1097/00000372-199508000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Polk P, Biggs PJ. Glomus tumor in neural tissue. Am J Dermatopathol. 1996;18:444. doi: 10.1097/00000372-199608000-00053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kim SW, Jung SN. Glomus tumour within digital nerve: a case report. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2011;64:958–960. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2010.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wong GN, Nandini CL, Teoh LC. Multiple intraneural glomus tumors on a digital nerve: case report. J Hand Surg Am. 2013;38:1972–1975. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2013.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Srinivasan D, Rajappa S. Glomus tumor of digital nerve - a case report. J Hand Microsurg. 2014;6:106–107. doi: 10.1007/s12593-014-0136-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Coindre JM. Grading of soft tissue sarcomas: review and update. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2006;130:1448–1453. doi: 10.5858/2006-130-1448-GOSTSR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Shurell E, Tran LM, Nakashima J, Smith KB, Tam BM, Li Y, Dry SM, Federman N, Tap WD, Wu H, Eilber FC. Gender dimorphism and age of onset in malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor preclinical models and human patients. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:827. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Keng VW, Rahrmann EP, Watson AL, Tschida BR, Moertel CL, Jessen WJ, Rizvi TA, Collins MH, Ratner N, Largaespada DA. PTEN and NF1 inactivation in Schwann cells produces a severe phenotype in the peripheral nervous system that promotes the development and malignant progression of peripheral nerve sheath tumors. Cancer Res. 2012;72:3405–3413. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-4092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Carter JM, O'Hara C, Dundas G, Gilchrist D, Collins MS, Eaton K, Judkins AR, Biegel JA, Folpe AL. Epithelioid malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor arising in a schwannoma, in a patient with "neuroblastoma-like" schwannomatosis and a novel germline SMARCB1 mutation. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:154–160. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3182380802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Goertz O, Langer S, Uthoff D, Ring A, Stricker I, Tannapfel A, Steinau HU. Diagnosis, treatment and survival of 65 patients with malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors. Anticancer Res. 2014;34:777–783. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Demehri S, Belzberg A, Blakeley J, Fayad LM. Conventional and functional MR imaging of peripheral nerve sheath tumors: initial experience. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2014;35:1615–1620. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A3910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Derlin T, Tornquist K, Münster S, Apostolova I, Hagel C, Friedrich RE, Wedegärtner U, Mautner VF. Comparative effectiveness of 18F-FDG PET/CT versus whole-body MRI for detection of malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors in neurofibromatosis type 1. Clin Nucl Med. 2013;38:e19–e25. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0b013e318266ce84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Yang J, Ylipää A, Sun Y, Zheng H, Chen K, Nykter M, Trent J, Ratner N, Lev DC, Zhang W. Genomic and molecular characterization of malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor identifies the IGF1R pathway as a primary target for treatment. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:7563–7573. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Yu J, Deshmukh H, Payton JE, Dunham C, Scheithauer BW, Tihan T, Prayson RA, Guha A, Bridge JA, Ferner RE, Lindberg GM, Gutmann RJ, Emnett RJ, Salavaggione L, Gutmann DH, Nagarajan R, Watson MA, Perry A. Array-based comparative genomic hybridization identifies CDK4 and FOXM1 alterations as independent predictors of survival in malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:1924–1934. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Longhi A, Errani C, Magagnoli G, Alberghini M, Gambarotti M, Mercuri M, Ferrari S. High grade malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors: outcome of 62 patients with localized disease and review of the literature. J Chemother. 2010;22:413–418. doi: 10.1179/joc.2010.22.6.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Stucky CC, Johnson KN, Gray RJ, Pockaj BA, Ocal IT, Rose PS, Wasif N. Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors (MPNST): the Mayo Clinic experience. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:878–885. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-1978-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kahn J, Gillespie A, Tsokos M, Ondos J, Dombi E, Camphausen K, Widemann BC, Kaushal A. Radiation therapy in management of sporadic and neurofibromatosis type 1-associated malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors. Front Oncol. 2014;4:324. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2014.00324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Bernthal NM, Putnam A, Jones KB, Viskochil D, Randall RL. The effect of surgical margins on outcomes for low grade MPNSTs and atypical neurofibroma. J Surg Oncol. 2014;110:813–816. doi: 10.1002/jso.23736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ferner RE, Golding JF, Smith M, Calonje E, Jan W, Sanjayanathan V, O'Doherty M. [18F]2-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography (FDG PET) as a diagnostic tool for neurofibromatosis 1 (NF1) associated malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumours (MPNSTs): a long-term clinical study. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:390–394. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]