Abstract

Objective: This study aimed to review the research status and to demonstrate the hot spots and frontiers of epilepsy and circadian rhythm via CiteSpace.

Method: We searched Web of Science (WoS) for studies related to epilepsy and circadian rhythm from inception to 2020. CiteSpace was used to generate network maps about the collaborations between authors, countries, and institutions and reveal hot spots and frontiers of epilepsy and circadian rhythm.

Results: A total of 704 studies related to epilepsy and circadian rhythm from the WoS were retrieved. Sanchez-Vazquez FJ was the most prolific author (17 articles). The USA and University of Murcia were the leading country and institution in this field with 219 and 22 publications, respectively. There were active collaborations among the authors, countries, and institutions. Hot topics focused on the interaction between epilepsy and circadian rhythm, as well as possible novel treatments.

Conclusions: Based on the results of CiteSpace, the current study suggested active cooperation between authors, countries, and institutions. Major ongoing research trends include the circadian rhythm of epilepsy based on different epileptic focus and the interaction between epilepsy and circadian rhythm, especially through melatonin, sleep–wake cycles, and clock genes, which may implicate possible treatments (such as chronotherapy, neural stem cells transplantation) for epilepsy in the future.

Keywords: epilepsy, circadian rhythm, bibliometrics, visualization analysis, CiteSpace, review

Background

Epilepsy is a common neurological disease with an unpredictable occurrence caused by abnormal discharge of brain neurons with high incidence and high cost (1, 2). A systematic review estimated that the point prevalence of active epilepsy was 6.38%0, while the lifetime prevalence was 7.6%0, especially higher in low- to middle-income countries (3). In the People's Republic of China, the lifetime epilepsy prevalence had increased to 4.57%0 in the 0–4 year group and 8.43%0 in the 30–34 year group by 2015 (4). Epilepsy affects about 65 million people in the entire world (5) and not only brings heavy economic burden to families and societies but also results in psychological problems (6).

The unpredictable nature of epileptic seizures makes it difficult to diagnose and treat. Current evidence and technology like electroencephalogram (EEG) recordings help confirm the association between epilepsy and circadian rhythm (7, 8), which may provide a new basis for the prediction and treatment of epilepsy. The circadian rhythm refers to the sleep–wake cycles, physiological and psychological behavior, and biology under the control of the circadian clock, including changes in sleep and wakefulness, core body temperature, blood pressure, and hormone levels. Evidence showed that circadian rhythm changed in epilepsy subjects (8), including hormones, body temperature, activity, and sleep–wake cycles (9, 10, 37). A better understanding of the relationship between epilepsy occurrence and circadian rhythm may provide more treatment approaches such as chronotherapy to control epilepsy. Therefore, visualizing the research status, hot spots, and frontiers of epilepsy and circadian rhythm is meaningful and necessary. CiteSpace is an application for analyzing and visualizing trends and patterns in scientific literature with metrology, co-occurrence analysis and cluster analysis based on Java (11, 12). By means of CiteSpace, our study focused on the network of co-authors, countries, and institutions; co-cited references analysis; co-occurring keywords and cluster analysis; and the burst of keywords and explored the hot spots and trends of epilepsy and circadian rhythm.

Method

Search Strategy

We retrieved related studies using the following terms: epilepsy and circadian rhythm. The index used was the Science Citation Index Expanded of Web of Science (SCI-EXPANDED), and the time span was from inception to 2020. A detailed search strategy was reported in Box 1.

BOX 1. Search strategy.

#1 (Epilepsy*) OR (Seizure Disorder*) OR (Aura*)

#2 (Circadian Rhythm*) OR (Diurnal Rhythm* OR Twenty* Four Hour Rhythm*

#1 AND #2

Index = the Science Citation Index Expanded of Web of Science (SCI-EXPANDED)

Time Span = inception−2020

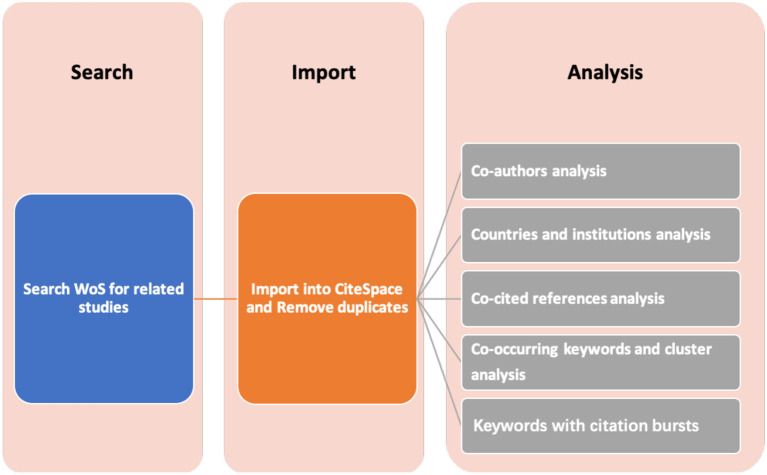

Visualization Analysis Tool—CiteSpace

CiteSpace was used for bibliometrics and visualization analysis, which can provide critical points in the development of epilepsy and circadian rhythm, including the fast-growth topical areas and citation hotspots. CiteSpace contains three central concepts, including burst detection, betweenness centrality, and heterogeneous networks, which help to identify the nature of a research front, label a specialty, and detect emerging trends and abrupt changes in a timely manner (12). There are various nodes and links in different CiteSpace visualization knowledge maps; nodes with high centrality are usually recognized as hot spots or turning points in a field. Data from WoS were exported in plain text format with full records and references, named “download_XXX.txt,” and then were imported into CiteSpace 5.3.R4 for analysis (Figure 1). Relevant visual maps were drawn and interpreted.

Figure 1.

Flow chart for CiteSpace.

Results

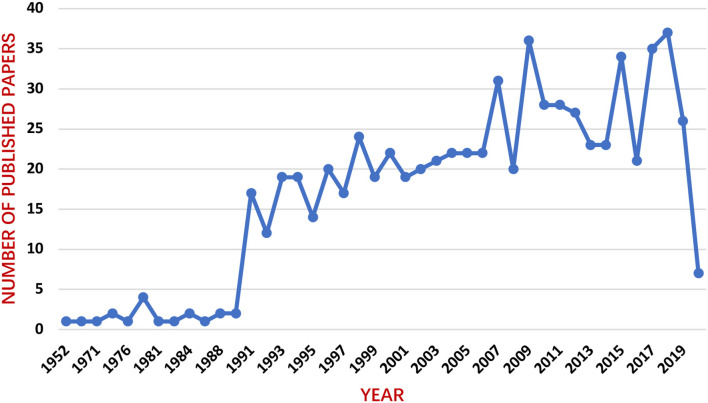

Publication Years

A total of 704 relevant papers were obtained after removing two duplicates (publications in 2020 were not fully included). As shown Figure 2, the number of publications about epilepsy and circadian rhythm has generally steadily increased but with some fluctuations, especially growing rapidly in 1990s, which indicates that this field received great attention in the 1990s.

Figure 2.

Annual trend chart of publications.

Co-authors Analysis

In the network of co-authors, each node represents one author, and the size of the node indicates the number of publications of the author. A larger node means more publications. The top 10 authors contributed 109 articles (15.48%) (Table 1). The most productive author was SANCHEZ-VAZQUEZ FJ (17 articles, 2.41%), followed by IIGO M (14 articles, 1.99%), REFINETTI R (14 articles, 1.99%), DELGADO MJ (13 articles, 1.85%), MENAKER M (11 articles, 1.56%), and TABATA M (11 articles, 1.56%). The lines between different authors represent collaboration. As presented in Figure 3, prolific authors often have stable collaboration with other authors.

Table 1.

The top 10 authors of epilepsy and circadian rhythm.

| Rank | Author | N (%) | Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | SANCHEZ-VAZQUEZ FJ | 17 (2.41%) | 1998 |

| 2 | IIGO M | 14 (1.99%) | 1996 |

| 3 | REFINETTI R | 14 (1.99%) | 1992 |

| 4 | DELGADO MJ | 13 (1.85%) | 2010 |

| 5 | MENAKER M | 11 (1.56%) | 1992 |

| 6 | TABATA M | 11 (1.56%) | 1996 |

| 7 | ISORNA E | 10 (1.42%) | 2010 |

| 8 | AIDA K | 7 (0.99%) | 1997 |

| 9 | MADRID JA | 6 (8.52%) | 2001 |

| 10 | STRAUME M | 6 (8.52%) | 1998 |

Figure 3.

The network of co-authors.

Countries and Institutions Analysis

The top 10 countries and top 5 institutions contributed 527 (74.86%) and 67 (9.52%) articles, respectively (Table 2). The top 5 countries were the USA, Spain, Japan, Germany, and Netherlands. And the top five institutions were the University of Murcia, University of Virginia, University Complutense Madrid, University of Tokyo, and Teikyo University of Science & Technology. Results showed that countries and institutions actively collaborated, especially with the USA and European countries (Figure 4).

Table 2.

The top 10 countries and top 5 institutions of epilepsy and circadian rhythm.

| Rank | Country | N (%) | Institution | N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | USA | 219 (31.11%) | University of Murcia | 22 (3.13%) |

| 2 | Spain | 89 (12.64%) | University of Virginia | 15 (2.13%) |

| 3 | Japan | 50 (7.10%) | University Complutense Madrid | 12 (1.70%) |

| 4 | Germany | 32 (4.55%) | University of Tokyo | 9 (1.28%) |

| 5 | Netherlands | 29 (4.12%) | Teikyo University of Science & Technology | 9 (1.28%) |

| 6 | Canada | 28 (3.98%) | ||

| 7 | Italy | 23 (3.27%) | ||

| 8 | France | 22 (3.13%) | ||

| 9 | England | 20 (2.84%) | ||

| 10 | Brazil | 15 (2.13%) |

Figure 4.

The network of countries and institutions.

Co-cited References Analysis

Table 3 presented the top 10 co-cited references related to epilepsy and circadian rhythm, and they were co-cited more than 160 times. The first co-cited reference was an article published by Ralph et al., (13) which proved the pacemaker role of the suprachiasmatic nucleus in a mammalian circadian system and laid a foundation for future research. The second co-cited reference was published by Durazzo et al., (14) and results of this article suggested that some epilepsy does not occur randomly. Endogenous circadian rhythms and rhythmic exogenous factors may play substantial roles in seizure occurrence. The third co-cited reference explored the day/night patterns of focal seizures (15). This article showed that both sleep/wake state and day/night or circadian rhythms may affect seizure proclivity, with different effects depending on the location of the epileptogenic region.

Table 3.

The top 10 co-cited references of epilepsy and circadian rhythm.

| Rank | Co-cited reference | Impact factor | Co-citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ralph MR, 1990, Science, V247, P975, Doi 10.1126/Science.2305266 |

41.037 | 22 |

| 2 | Durazzo TS, 2008, Neurology, V70, P1265, Doi 10.1212/01.Wnl.0000308938.84918.3f |

8.689 | 21 |

| 3 | Pavlova MK, 2004, Epilepsy Behav, V5, P44, Doi 10.1016/J.Yebeh.2003.10.013 |

2.378 | 19 |

| 4 | Feliciano A, 2011, J Biol Rhythm, V26, P24, Doi 10.1177/0748730410388600 |

2.473 | 17 |

| 5 | Velarde E, 2009, J Biol Rhythm, V24, P104, Doi 10.1177/0748730408329901 |

2.473 | 16 |

| 6 | Hofstra WA, 2009, Epilepsia, V50, P2019, Doi 10.1111/J.1528-1167.2009.02044.X |

5.562 | 16 |

| 7 | Loddenkemper T, 2011, Neurology, V76, P145, Doi 10.1212/Wnl.0b013e318206ca46 |

8.689 | 15 |

| 8 | Hofstra WA, 2009, Epilepsy Behav, V14, P617, Doi 10.1016/J.Yebeh.2009.01.020 |

2.378 | 13 |

| 9 | Dibner C, 2010, Annu Rev Physiol, V72, P517, Doi 10.1146/Annurev-Physiol-021909-135821 |

17.902 | 13 |

| 10 | Vera LM, 2013, Chronobiol Int, V30, P649, Doi 10.3109/07420528.2013.775143 |

2.562 | 12 |

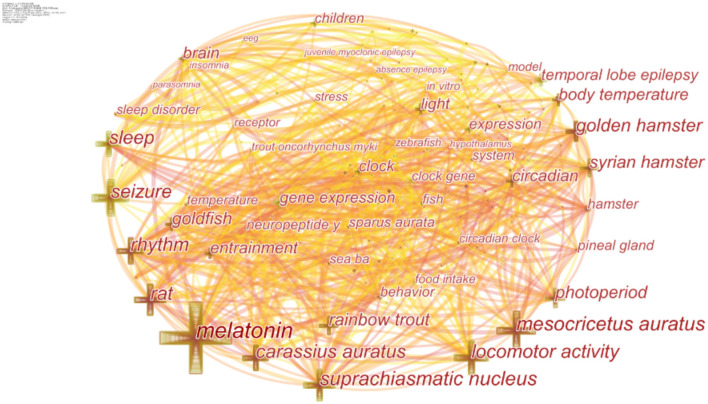

Co-occurring Keywords and Cluster Analysis

High-frequency keywords represent a hot topic in a research field, while high-centrality keywords reflect the position and influence of the corresponding research content in this research field. As shown in Table 4, hot keywords in the frequency and centrality order were melatonin (MT) (frequency: 142, centrality: 0.16), mesocricetus auratus (frequency: 84, centrality: 0.14), and carassius auratus (frequency: 66, centrality: 0.11). Other keywords included gene expression, temporal lobe epilepsy, neuropeptide, pineal gland, children, and so on (Figure 5).

Table 4.

Top 10 keywords in terms of frequency and centrality of epilepsy and circadian rhythm.

| Rank | Frequency | Keywords | Centrality | Keywords |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 321 | Circadian rhythm | 0.2 | Epilepsy |

| 2 | 142 | Melatonin | 0.16 | Melatonin |

| 3 | 135 | Epilepsy | 0.15 | Entrainment |

| 4 | 84 | Mesocricetus auratus | 0.14 | Circadian rhythm |

| 5 | 76 | Suprachiasmatic nucleus | 0.14 | Mesocricetus auratus |

| 6 | 72 | Seizure | 0.13 | Brain |

| 7 | 72 | Locomotor activity | 0.12 | Circadian |

| 8 | 69 | Sleep | 0.11 | Carassius auratus |

| 9 | 67 | Rat | 0.1 | Golden hamster |

| 10 | 66 | Carassius auratus | 0.1 | Rainbow trout |

Figure 5.

Co-occurring keywords map.

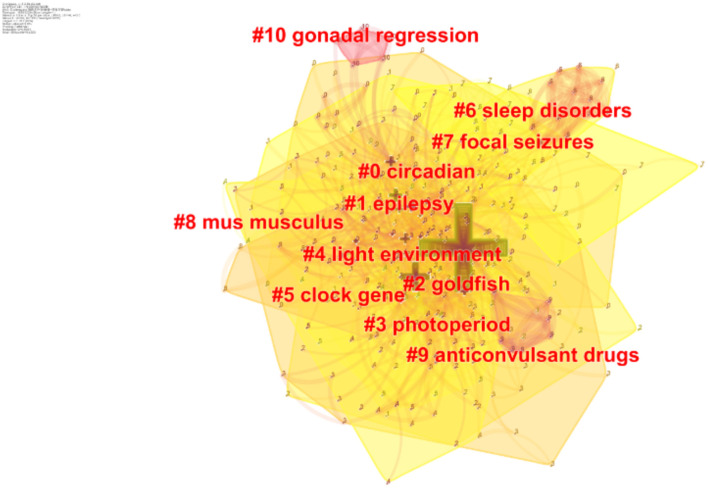

Clustering analysis revealing the main topics was performed for co-occurrence keywords using CiteSpace. The mean silhouette is usually used for evaluating the clusters. In general, a silhouette value over 0.7 means the cluster is high in efficiency and convincing; if it is above 0.5, the cluster is generally considered reasonable. Eventually, we obtained 10 clusters, and the silhouette value for each cluster was over 0.5, suggesting that the results were reliable and meaningful. Among them, seven clusters had a silhouette value over 0.7 (Figure 6, Table 5).

Figure 6.

Keywords cluster analysis co-occurrence map.

Table 5.

Keywords cluster analysis (the silhouette value is over 0.7).

| Cluster ID | Silhouette | Label (LLR) | Included keywords (top 15) | Cite year |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | 0.785 | Light environment | Stress; innate immunity; light–darkness cycle; pikeperch; otolith; light spectrum; pike perch; circadian axis; hpi axis; ketone body regulation; neurological disorders; epigenetics; immunity; ketogenic diet; metabolic disorders | 2007 |

| 5 | 0.701 | Clock gene | Melatonin; fasting; liver; dopamine receptors; pituitary; muscle functional gene; intestine; circadian system; dopamine; annual reproductive cycle; food hoarding; photoperiodism; green wavelength; refractoriness; functional genes | 2006 |

| 6 | 0.867 | Sleep disorders | Insomnia; polysomnography; circadian rhythm disorders; parasomnias; narcolepsy; practice guidelines; practice parameters; standards of practice; sleep apnea syndrome; periodic limb movement disorder; restless legs syndrome; disease symptoms; neurologic diseases; international classification of sleep disorders; interictal | 2004 |

| 7 | 0.848 | Focal seizures | Polyspike; spike-wave; photoparoxysmal response; absence epilepsy; spike-wave discharges; absence; wag; myoclonus; rij rats; tonic–clonic seizure; genetic model; juvenile myoclonic epilepsy; rem sleep; wag/rij rats; sleep-related epilepsy | 2013 |

| 8 | 0.929 | Mus musculus | Dark adaptation; photic entrainment; period length; interindividual variability; stability; phase response; circadian rhythm; running wheel; arvicanthis niloticus; dark pulses; light pulses; mongolian gerbils; locomotor activity; mesocricetus auratus; masking | 2001 |

| 9 | 0.975 | Anticonvulsant drugs | Experimental seizures; electroshock; pentylenetetrazol; epilepsy; melatonin analogs; sedative; anticonvulsant; gamma distribution; rodents; anxiolytic; automated seizure detection; preclinical research; sleep disturbance; rett syndrome; seizure | 1991 |

| 10 | 0.983 | Gonadal regression | Short photoperiod; long photoperiod; recrudescence; golden hamster; circadian rhythms; circadian rhythm; epilepsy; melatonin; locomotor activity; circadian; photoperiod; goldfish; mesocricetus auratus; suprachiasmatic nucleus; sleep disorders | 1991 |

Keywords With Citation Bursts

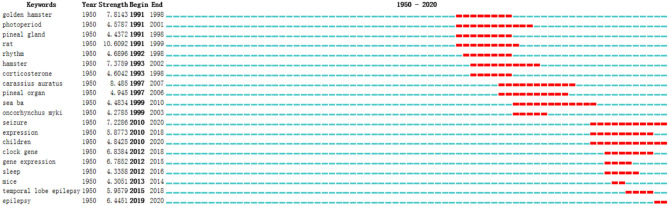

Figure 7 showed the top 20 keywords with the strongest citation bursts. The blue line represents the time interval, while the red line indicates the time period in which a keyword was found to have a burst (16). Keywords with citation bursts first appeared in 1950 (golden hamster, photoperiod, and pineal gland), along with the strongest keyword (rat). The most recent keyword with citation bursts appeared in 2019 (epilepsy). And 3 keywords with citation bursts continue to 2020 (seizure, children, and epilepsy).

Figure 7.

Top 20 keywords with the strongest citation bursts.

Discussion

Summary of Findings

The current study aimed to review the research status and demonstrate the hot spots and frontiers of epilepsy and circadian rhythm via CiteSpace. A total of 704 studies related to epilepsy and circadian rhythm were retrieved from the WoS. Sanchez-Vazquez FJ was the most prolific author (17 articles). The USA and University of Murcia were the leading country and institution in this field with 219 and 22 publications, respectively. There were active collaborations among the authors, countries, and institutions. Hot topics focused on the interaction between epilepsy and circadian rhythm, as well as possible novel treatments.

Active Cooperation Is Urgent

Although the number of publications about epilepsy and circadian rhythm fluctuated each year, epilepsy and circadian rhythm have been proven to be a hot research field since their emergence. Active cooperation was observed between prolific authors and developed countries especially the USA and European countries. Besides, co-authors analysis and co-cited references analysis suggested that high-frequency co-cited references did not come from prolific authors. Therefore, it is urgent for developing countries to encourage institutions to participate in research, strengthen cooperation, promote the development of related fields, and publish high-quality articles.

Hot Issues in Epilepsy and Circadian Rhythm Research

Keywords are the high-level summarization and conciseness of the topic of an article. During the analysis process, the commonly used keywords were often used to identify hot issues in a research field. Results of co-occurring keywords and cluster analysis suggested that major ongoing research trends include the circadian rhythm of epilepsy based on different epileptic focus and the interaction between epilepsy and circadian rhythm, especially through MT, sleep–wake cycles, and clock genes, which may implicate possible treatments (such as chronotherapy and neural stem cell transplantation) for epilepsy in the future.

Epileptic Focus

The circadian rhythm of epilepsy occurrence is influenced by the localization of epilepsy. After analyzing the clinical seizures of 170 consecutive epilepsy patients, Gurkas et al. (17) found that seizures in children occur in specific circadian patterns depending on seizure onset location: generalized seizures were seen most frequently in wakefulness; frontal lobe seizures were seen at night and in sleep. In children, temporal lobe seizures occurred more frequently in wakefulness, usually in early evening (9, 18, 19, 37). Spencer et al. (20) used the NeuroPace RNS System to record objective and long-term rhythmicity of epileptiform activity and found that long episodes and long episodes validated as electrographic seizures patterns varied by region. The above results suggest implications for future treatments based on different epileptic focus.

Type

The diurnal pattern of seizure occurrence is also affected by the type of epilepsy (generalized or focal). Studies showed that the occurrence of generalized seizures and focal seizures originating from the parietal lobe in particular followed the circadian rhythm of cortisol (21).

Children

Changed circadian rhythm is evident in children with epilepsy. The results of Loddenkemper et al. (9) showed that, in children with focal epilepsy, frontal lobe seizures occurred predominantly during sleep, while temporal lobe seizures happened mostly during wakefulness. Generalized epilepsy often happens during daytime when children are wake (17, 22). Passarelli et al. (23) found that young patients with epilepsy associated with unilateral mesial temporal sclerosis had more seizures than middle-aged/old patients between 16:01 and 20:00 during video-EEG monitoring. Whether age plays an important role in the occurrence of epilepsy needs further study.

Melatonin

The pineal gland is a major component of the mammalian circadian rhythmicity system, which synthesizes MT at night. The secretion of MT shows a regular pattern of less secretion during the day and more secretion in the night, white sputum, and low night, which is synchronized with the peripheral light–dark cycle (24), and has a wide range of physiological functions such as maintaining circadian rhythmicity, promoting sleep, and enhancing human immune function. In various animal models of epilepsy, MT plays an antiepileptic effect (25–27). Mevissen et al. (28) found that the threshold of epileptic release in amygdala-ignited model rats was significantly increased by about 200 or 250% after 30 min of intraperitoneal injection of MT (75 or 100 mg/kg), which may significantly reduce the sensitivity of seizures in rats. The increase in epilepsy caused by MT of 75 mg/kg is comparable to the increase in post-release caused by conventional antiepileptic drugs such as carbamazepine, valproate, and phenytoin, and MT can also prevent secondary epileptic seizures (29). Significant clinical improvement in seizure activity was reported during MT treatment, particularly during the night (30). However, this conclusion needs to be further verified due to conflicting results. A Cochrane review published by Brigo (31) concluded that it was impossible to confirm the role of MT in reducing seizure frequency or improving quality of life in people with epilepsy and that adverse events of MT were not systematically evaluated.

Clock Genes

Cluster #5 indicated the vital role of clock genes in the circadian variation of epileptic excitability in epilepsy. By performing transcriptome analysis on human epileptogenic tissue, Li et al. (32) reported that disruption of clock circadian regulator (CLOCK) altered cortical circuits and may lead to generation of focal epilepsy. The BMAL1 gene, which codes for the binding partner of CLOCK to form the transcription CLOCK–BMAL1 complex, is also directly involved in epilepsy as proven by animal research (33). Leite Goes Gitai et al. (34) reported that, for mesial temporal lobe epilepsy patients, the imbalance of core clock genes in the epileptic hippocampus may affect the phase and amplitude of different genes that play roles in the electrical activity of neurons with consequences on the rhythmic fluctuation in the inhibitory/excitatory imbalance. The results of Matos et al. (35) also showed that altered temporal expression of the clock genes after a post-status epilepticus model suggests that clock genes may be involved in epilepsy. Therefore, chronotherapy and neural stem cell transplantation, as well as light, diet, exercise, and other zeitgebers, could modulate the rhythms in the hippocampus, and related structures may bring clinical benefits for reducing epilepsy. However, these genes and transcription factors should be further studied except in patients with lesional epilepsy associated with focal cortical dysplasia and tuberous sclerosis complex (36).

Sleep–Wake Cycles

As one of the representatives of circadian rhythm, sleep and wakefulness are easy to observe, which dominate epilepsy time biology studies and are the most robust predictors of seizures (9, 37). Animal experiments further confirmed the relationship between epilepsy occurrence and circadian rhythm (38). It is reported that sleep–wake-related patterns may have a role in seizure susceptibility (39), especially in patients with frontal lobe epilepsy, where sleep-related seizures are more evident (40). Temporal lobe complex partial seizures decrease rapid eye movement (REM) sleep (41). and non-REM sleep could favor epilepsy occurrence (40, 42), which may be supported by topographical EEG analyses (43).

Subjects

Keywords with citation bursts showed that 3 keywords (seizure, children, and epilepsy) with citation bursts continue to 2020, indicating that children with epilepsy has been getting great attention in recent years. Future studies could apply the results so far to human research subjects, especially children.

Strengths and Limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first study to use the co-occurrence and co-citation analysis methods by CiteSpace to perform bibliometric analysis and visual display of the epilepsy and circadian rhythm from hot spots, co-cited references, and cooperation among authors, countries, and institutions. However, our study still has some limitations. Limited by the CiteSpace software, we analyzed only English studies in WoS; therefore, the data may not be comprehensive enough, and our results may not be applied to research published in other languages. Besides, due to the existence of multiple synonyms, when clustering keywords, there may be some overlap between different categories of content.

Conclusions

Based on the results of CiteSpace, the current study suggested active cooperation between authors, countries, and institutions. Major ongoing research trends include the circadian rhythm of epilepsy based on different epileptic focus and the interaction between epilepsy and circadian rhythm, especially through MT, sleep–wake cycles, and clock genes, which may implicate possible treatments (such as chronotherapy and neural stem cell transplantation) for epilepsy in the future.

Author Contributions

YZ designed and analyzed the data. DZ and SL drafted the manuscript and edited the manuscript. LZ analyzed the data. RJ contributed to revising the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Begley CE, Beghi E. The economic cost of epilepsy: a review of the literature. Epilepsia. (2002) 43 (Suppl. 4):3–9. 10.1046/j.1528-1157.43.s.4.2.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murray CJ, Vos T, Lozano R, Naghavi M, Flaxman AD, et al. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. (2012) 380:2197–223. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61689-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fiest KM, Sauro KM, Wiebe S, Patten SB, Kwon CS, Dykeman J, et al. Prevalence and incidence of epilepsy: a systematic review and meta-analysis of international studies. Neurology. (2017) 88:296–303. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Song P, Liu Y, Yu X, Wu J, Poon AN, Demaio A, et al. Prevalence of epilepsy in China between 1990 and 2015: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Glob Health. (2017) 7:020706. 10.7189/jogh.07.020706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thurman DJ, Beghi E, Begley CE, Berg AT, Buchhalter JR, Ding D, et al. Standards for epidemiologic studies and surveillance of epilepsy. Epilepsia. (2011) 52 (Suppl. 7):2–26. 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2011.03121.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tellez-Zenteno JF, Patten SB, Jette N, Williams J, Wiebe S. Psychiatric comorbidity in epilepsy: a population-based analysis. Epilepsia. (2007) 48:2336–44. 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01222.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karoly PJ, Ung H, Grayden DB, Kuhlmann L, Leyde K, Cook MJ, et al. The circadian profile of epilepsy improves seizure forecasting. Brain. (2017) 140:2169–82. 10.1093/brain/awx173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baud MO, Kleen JK, Mirro EA, Andrechak JC, King SD, et al. Multi-day rhythms modulate seizure risk in epilepsy. Nat Commun. (2018) 9:88. 10.1038/s41467-017-02577-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Loddenkemper T, Vendrame M, Zarowski M, Gregas M, Alexopoulos AV, Wyllie E, et al. Circadian patterns of pediatric seizures. Neurology. (2011) 76:145. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318206ca46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smyk MK, van Luijtelaar G. Circadian rhythms and epilepsy: a suitable case for absence epilepsy. Front Neurol. (2020) 11:245. 10.3389/fneur.2020.00245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen C. Searching for intellectual turning points: progressive knowledge domain visualization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2004) 101 (Suppl. 1):5303–10. 10.1073/pnas.0307513100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen CM. CiteSpace II: detecting and visualizing emerging trends and transient patterns in scientific literature. J Am Soc Inf Sci Tec. (2006) 57:359–77. 10.1002/asi.20317 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ralph MR, Foster RG, Davis FC, Menaker M. Transplanted suprachiasmatic nucleus determines circadian period. Science. (1990) 247:975–8. 10.1126/science.2305266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Durazzo TS, Spencer SS, Duckrow RB, Novotny EJ, Spencer DD, Zaveri HP. Temporal distributions of seizure occurrence from various epileptogenic regions. Neurology. (2008) 70:1265–71. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000308938.84918.3f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pavlova MK, Shea SA, Bromfield EB. Day/night patterns of focal seizures. Epilepsy Behav. (2004) 5:44–9. 10.1016/j.yebeh.2003.10.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen CM, Dubin R, Kim MC. Emerging trends and new developments in regenerative medicine: a scientometric update (2000 - 2014). Expert Opin Biol Thai. (2014) 14:1295–317. 10.1517/14712598.2014.920813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gurkas E, Serdaroglu A, Hirfanoglu T, Kartal A, Yilmaz U, Bilir E. Sleep-wake distribution and circadian patterns of epileptic seizures in children. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. (2016) 20:549–54. 10.1016/j.ejpn.2016.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hofstra WA, Spetgens WPJ, Leijten FSS, Rijen PCV, Gosselaar P, Palen JVD, et al. Diurnal rhythms in seizures detected by intracranial electrocorticographic monitoring: an observational study. Epilepsy Behav. (2009) 14:617–21. 10.1016/j.yebeh.2009.01.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pavlova MK, Jong Woo L, Furkan Y, Dworetzky BA. Diurnal pattern of seizures outside the hospital: is there a time of circadian vulnerability? Neurology. (2012) 78:1488–92. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182553c23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spencer DC, Sun FT, Brown SN, Jobst BC, Fountain NB, Wong VS, et al. Circadian and ultradian patterns of epileptiform discharges differ by seizure-onset location during long-term ambulatory intracranial monitoring. Epilepsia. (2016) 57:1495–502. 10.1111/epi.13455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van Campen JS, Valentijn FA, Jansen FE, Joels M, Braun KP. Seizure occurrence and the circadian rhythm of cortisol: a systematic review. Epilepsy Behav. (2015) 47:132–7. 10.1016/j.yebeh.2015.04.071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sriram R, Christine P, Marcin Z, Alexopoulos AV, Kothare SV, Tobias L. Predicting diurnal and sleep/wake seizure patterns in paediatric patients of different ages. Epileptic Disord. (2014) 16:56–66. 10.1684/epd.2014.0644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Passarelli V, Castro LH. Gender and age influence in daytime and nighttime seizure occurrence in epilepsy associated with mesial temporal sclerosis. Epilepsy Behav. (2015) 50:14–7. 10.1016/j.yebeh.2015.05.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morgan PJ, Barrett P, Howell HE, Helliwell R. Melatonin receptors: localization, molecular pharmacology and physiological significance. Neurochem Int. (1994) 24:101–46. 10.1016/0197-0186(94)90100-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lapin IP, Mirzaev SM, Ryzov IV, Oxenkrug GF. Anticonvulsant activity of melatonin against seizures induced by quinolinate, kainate, glutamate, NMDA, and pentylenetetrazole in mice. J Pineal Res. (2010) 24:215–8. 10.1111/j.1600-079X.1998.tb00535.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Costa-Lotufo LcV, Fonteles MMDF, Lima ISP, Oliveira AAD, Nascimento VS, Veralice MSB, et al. Attenuating effects of melatonin on pilocarpine-induced seizures in rats. Comp Biochem Physiol C Toxicol Pharmacol. (2002) 131:521–9. 10.1016/S1532-0456(02)00037-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Borowicz KK, Kamiński R, Gasior M, Kleinrok Z, Czuczwar SJ. Influence of melatonin upon the protective action of conventional anti-epileptic drugs against maximal electroshock in mice. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. (1999) 9:185–90. 10.1016/S0924-977X(98)00022-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mevissen M, Ebert U. Anticonvulsant effects of melatonin in amygdala-kindled rats. Neurosci Lett. (1998) 257:13–6. 10.1016/S0304-3940(98)00790-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Löscher W, Rundfeldt C, Hönack D. Pharmacological characterization of phenytoin-resistant amygdala-kindled rats, a new model of drug-resistant partial epilepsy. Epilepsy Res. (1993) 15:207. 10.1016/0920-1211(93)90058-F [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peled N, Shorer Z, Peled E, Pillar G. Melatonin effect on seizures in children with severe neurologic deficit disorders. Epilepsia. (2010) 42:1208–10. 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2001.28100.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brigo F, Igwe SC, Del Felice A. Melatonin as add-on treatment for epilepsy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2016) 8:CD006967 10.1002/14651858.CD006967.pub4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li P, Fu X, Smith NA, Ziobro J, Curiel J, Tenga MJ, et al. Loss of CLOCK results in dysfunction of brain circuits underlying focal epilepsy. Neuron. (2017) 96:387–401 e386. 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.09.044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gerstner JR, Smith GG, Lenz O, Perron IJ, Buono RJ, Ferraro TN. BMAL1 controls the diurnal rhythm and set point for electrical seizure threshold in mice. Front Syst Neurosci. (2014) 8:121. 10.3389/fnsys.2014.00121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leite Goes Gitai D, de Andrade TG, Dos Santos YDR, Attaluri S, Shetty AK. Chronobiology of limbic seizures: potential mechanisms and prospects of chronotherapy for mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. (2019) 98:122–34. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2019.01.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Matos HC, Koike BDV, Pereira WDS, de Andrade TG, Castro OW, Duzzioni M, et al. Rhythms of core clock genes and spontaneous locomotor activity in post-status epilepticus model of mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. Front Neurol. (2018) 9:632. 10.3389/fneur.2018.00632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lipton JO, Yuan ED, Boyle LM, Ebrahimi FD, Kwiatkowski E, Nathan A, et al. The circadian protein BMAL1 regulates translation in response to S6K1-mediated phosphorylation. Cell. (2015) 161:1138–51. 10.1016/j.cell.2015.04.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kaleyias J, Loddenkemper T, Vendrame M, Das R, Syed TU, Alexopoulos AV, et al. Sleep-wake patterns of seizures in children with lesional epilepsy. Pediatr Neurol. (2011) 45:109–13. 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2011.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pitsch J, Becker AJ, Schoch S, Müller JA, De CM, Gnatkovsky V. Circadian clustering of spontaneous epileptic seizures emerges after pilocarpine-induced status epilepticus. Epilepsia. (2017) 58:1159–71. 10.1111/epi.13795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chellappa SL, Gaggioni G, Ly JQ, Papachilleos S, Borsu C, Brzozowski A, et al. Circadian dynamics in measures of cortical excitation and inhibition balance. Sci Rep. (2016) 6:33661. 10.1038/srep33661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tinuper P, Bisulli F, Cross JH, Hesdorffer D, Kahane P, Nobili L, et al. Definition and diagnostic criteria of sleep-related hypermotor epilepsy. Neurology. (2016) 86:WNL.0000000000002666. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bazil CW, Castro LH, Walczak TS. Reduction of rapid eye movement sleep by diurnal and nocturnal seizures in temporal lobe epilepsy. Arch Neurol. (2000) 57:363–8. 10.1001/archneur.57.3.363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pavlova MK, Shea SA, Scheer FAJL, Bromfield EB. Is there a circadian variation of epileptiform abnormalities in idiopathic generalized epilepsy? Epilepsy Behav. (2009) 16:461–7. 10.1016/j.yebeh.2009.08.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lazar AS, Lazar ZI, Dijk DJ. Circadian regulation of slow waves in human sleep: topographical aspects. Neuroimage. (2015) 116:123–34. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.05.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]