Key Points

Question

Are borderline personality disorder (BPD) and its specific diagnostic criteria associated with who reports a suicide attempt(s) over 10 years of prospective follow-up?

Findings

In this longitudinal study of adults with personality disorders, after controlling for significant demographic and other clinical risk factors, BPD and the specific criteria of identity disturbance, chronic feelings of emptiness, and frantic efforts to avoid abandonment emerged as significant factors associated with prospectively observed suicide attempt status.

Meaning

Identity disturbance, chronic feelings of emptiness, and frantic efforts to avoid abandonment may be clinically overlooked features of BPD in context of suicide risk assessment.

Abstract

Importance

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) has been identified as a strong risk factor for suicidal behavior, including suicide attempts. Delineating specific features that increase risk could inform interventions.

Objective

To examine factors associated with prospectively observed suicide attempts among participants in the Collaborative Longitudinal Study of Personality Disorders (CLPS), over 10 years of follow-up, with a focus on BPD and BPD criteria.

Design, Setting, and Participants

The CLPS is a multisite, naturalistic, prospective study of adult participants with 4 personality disorders (PDs) and a comparison group of adults with major depressive disorder and minimal PD features. Participants were all treatment-seeking and recruited from inpatient, partial, and outpatient treatment settings across New York, New York, Boston, Massachusetts, New Haven, Connecticut, and Providence, Rhode Island. A total of 733 participants were recruited at baseline, with 701 completing at least 1 follow-up assessment. The cohorts were recruited from September 1996 through April 1998 and September 2001 through August 2002. Data for this study using this follow-up sample (N = 701) were analyzed between March 2019 and August 2020.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Participants were assessed annually using semistructured diagnostic interviews and a variety of self-report measures for up to 10 years. Multiple logistic regression analyses were used to examine baseline demographic and clinical risk factors, including BPD and individual BPD criteria, of suicide attempt assessed over 10 years of prospective follow-up.

Results

Of the 701 participants, 447 (64%) identified as female, 488 (70%) as White, 527 (75%) as single, 433 (62%) were unemployed, and 512 (73%) reported at least some college education. Of all disorders, BPD emerged as the most robust factor associated with prospectively observed suicide attempt(s) (odds ratio [OR], 4.18; 95% CI, 2.68-6.52), even after controlling for significant demographic (sex, employment, and education) and clinical (childhood sexual abuse, alcohol use disorder, substance use disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder) factors. Among BPD criteria, identity disturbance (OR, 2.21; 95% CI, 1.37-3.56), chronic feelings of emptiness (OR, 1.63; 95% CI, 1.03-2.57), and frantic efforts to avoid abandonment (OR, 1.93; 95% CI, 1.17-3.16) emerged as significant independent factors associated with suicide attempt(s) over follow-up, when covarying for other significant factors and BPD criteria.

Conclusions and Relevance

In the multisite, longitudinal study of adults with personality disorders, identity disturbance, chronic feelings of emptiness, and frantic efforts to avoid abandonment were significantly associated with suicide attempts. Identity disturbance, chronic feelings of emptiness, and frantic efforts to avoid abandonment may be clinically overlooked features of BPD in context of suicide risk assessment. In light of the high rates of BPD diagnostic remission, our findings suggest that these criteria should be independently assessed and targeted for further study as suicide risk factors.

This study examines prospective factors associated with suicide attempts among participants over 10 years of follow-up, with a focus on borderline personality disorder and its diagnostic criteria.

Introduction

Suicidal behavior, which encompasses deaths, attempts, and ideation, is a significant public health concern and has increased over the past decade.1 Many psychiatric disorders are associated with an increased risk for suicide attempts; however, it has been estimated that 73% of patients with borderline personality disorder (BPD) will have approximately 3 suicide attempts in their lifetime,2 and as many as 9% will die by suicide.3 This significant risk for suicidal behaviors occurs independently of BPD’s common psychiatric comorbidities, such as major depressive disorder (MDD) and substance use disorder (SUD).4

Given the heterogeneous nature of BPD, identifying which components of the disorder in particular confer greatest risk for suicidal behaviors would aid intervention development. Prospective studies to date most consistently identify the affective instability criterion as a precipitant of suicidal behavior. Data from earlier follow-up intervals of the Collaborative Longitudinal Study of Personality Disorders (CLPS) found that, while affective instability, impulsivity, and identity disturbance all were prospectively associated with suicidal behavior, only the BPD affective instability criterion was associated with suicide attempts with nonzero intent to die after 2 years of follow-up.5 Similarly, negative affectivity was also associated with suicide attempts after 7 years of follow-up.6 In another longitudinal study of 290 inpatients, affective instability, along with self-harm and dissociation, were found to be the BPD criteria that were prospectively associated with suicide attempts over 16 years of follow-up.7 This association between affective instability and suicidal ideation and behavior has also been observed more proximally in studies using experience sampling methods.8

The heightened impulsivity characteristic of BPD has also been identified as potentially exacerbating suicide risk. One retrospective study9 identified impulsivity as the only BPD criterion independently linked to suicidal behavior, and several studies link impulsivity to suicide risk within individuals with BPD.6,10,11 Affective instability and impulsivity, while components of BPD, are also symptoms of, or constructs linked to, numerous other psychiatric disorders. Other features of BPD, such as identity disturbance and those related to disturbance in interpersonal functioning, are unique and specific to BPD,12 yet limited research specifically investigates these criteria’s associations with suicide and self-injury, and whether these symptoms specifically contribute to the independent risk BPD confers.

Additionally, prior work on independent components of BPD and suicide has been limited to 2-year predictions at most, despite the potential for BPD to be a prolonged condition conferring risk across the life span. Using data from the CLPS, a longitudinal, multisite study of the course and outcome of personality disorders, this study seeks to extend this line of inquiry by examining how individual BPD criteria are prospectively associated with suicide attempts over 10 years of follow-up. Based on earlier findings,5 we anticipate that affective instability and impulsivity will continue to be independently associated with suicidal behavior, but that chronic feelings of emptiness, identity disturbance, and frantic efforts to avoid abandonment will also be associated with suicide attempt over follow-up because this latter set of criteria has been found to be associated with self-injurious behavior3,13,14 and is unique and specific to BPD.

Methods

The CLPS is a multisite, longitudinal study on the course and outcome of 4 PDs: schizotypal (STPD), BPD, avoidant (AVPD), and obsessive compulsive (OCPD), and a comparison group of MDD without PD, in which a maximum of 2 criteria were allowed for any PD. The CLPS had 10 years of follow-up data, which included weekly ratings for axis I disorders and monthly ratings of PD criteria for the 4 PDs of interest, assessed at annual intervals. Institutional review boards approved CLPS at all 4 sites, Brown University, Harvard University, Columbia University, and Yale University, as well as data collection subsites. All participants provided written informed consent.

Participants

The CLPS study had a total of 733 participants, aged 18 to 45 years, recruited from treatment clinics affiliated with the 4 CLPS sites, targeting those currently in inpatient, partial, or outpatient treatment or with prior treatment history. Excluded from participation were individuals with (1) acute substance intoxication or withdrawal; (2) active psychosis; (3) cognitive impairment; or (4) a history of either schizophrenia, schizophreniform, or schizoaffective disorders. If individuals met the diagnostic criteria for at least 1 of 4 PDs assessed in the CLPS or for MDD without PD (see subsequent sections for assessment methods), they were eligible to participate. Participants were interviewed at baseline, 6 months, 1 year, and annually until 10 years of follow-up.

Personality disorder criteria were assessed using the Diagnostic Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders (DIPD)15 administered at baseline and throughout follow-up. Verification of the PD diagnosis came from a self-report measure, the Schedule for Nonadaptive and Adaptive Personality,16 and/or clinical assessment from an outside clinician. Participants who met criteria for 1 of 4 PDs (STPD, BPD, AVPD, or OCPD) were enrolled into the study. The comparison group consisted of participants who met full criteria for MDD as assessed using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV,17 but with no more than 2 criteria for any PD.

Measures

The DIPD-IV15 is a semistructured interview consisting of questions that assess each criterion of the 10 DSM–IV PDs. In this study, interrater and test-retest reliability of the DIPD-IV (κ) were 0.68 for the PDs and 0.69 for BPD.18 Axis I disorders were assessed using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV,17 a semistructured interview with demonstrated reliability. The interrater reliability κ and test-retest κ for axis I disorders in this study ranged from 0.80 to 1.00 and 0.61 to 0.78, respectively.

Childhood sexual abuse was assessed using the Revised Childhood Experiences Questionnaire (CEQ-R19), a semistructured interview assessing a number of childhood abuse and neglect experiences, from ages 0 to 17 years. The CEQ-R has good psychometric properties with a median κ of 0.88 for interrater reliability.

Suicidal behavior was assessed using the Longitudinal Interview Follow-up Evaluation (LIFE),20 a semistructured interview rating system with demonstrated reliability for assessing the longitudinal course of psychiatric disorders and functioning, including suicidal behaviors. Suicide attempts are operationalized as any suicidal behaviors with nonzero intent to die, regardless of medical threat, and are recorded for each month of follow-up.

Data Analyses

All analyses were conducted using SPSS, version 25 (IBM), and used 2-tailed hypothesis tests with α = .05. Logistic regression models were conducted to examine whether baseline demographic predicted occurrence of a suicide attempt status over 10 years of follow-up. Similarly, logistic models were conducted to examine associations of individual clinical variables with the occurrence of a suicide attempt, controlling for significant demographic variables. A combined model including all significant demographic and clinical variables was conducted to evaluate their independent associations. A Cox proportional hazard regression model for the association of BPD with time to suicide attempt was conducted as confirmatory, posthoc analysis.

A series of logistic regression models, controlling for significant demographic and clinical variables, estimated specific BPD criteria as factors prospectively associated with suicide attempt over 10 years of follow-up. The BPD criteria as risk factors were examined independently in separate models as well as simultaneously.

Results

A subsample of 701 participants providing follow-up data was used in this study. There were no significant differences on demographic variables between those who did and did not provide follow-up data. Descriptive statistics for zero-order correlations between all variables are presented in the eTable in the Supplement. Participants were a mean age of approximately 33 years at baseline, and most were female (n = 447; 64%), identified their race/ethnicity as White (n = 488; 70%) based on self-report demographic forms with prespecified categories, reported completing at least some college as their highest level of education (n = 512; 73%), and reported being unemployed at baseline (n = 433; 62%).

Demographic variables were initially entered into individual logistic regression models as factors associated with suicide attempt over follow-up (Table 1). Over 10 years of prospective follow-up, 148 (21%) endorsed suicidal behavior with nonzero intent at some point. Being female, less educated (high school degree or less), and being unemployed were significantly associated with suicide attempt over follow-up, with each demographic factor resulting in approximately 1.5 times greater odds of making a suicide attempt over follow-up.1

Table 1. Separate Logistic Regression Analyses of Demographic and Clinical Factors Associated With SA+ Over 10 Years of Follow-up (N = 701).

| Variable | No. (%) | Wald χ2 | OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SA+ (n = 148) | SA− (n = 553) | |||

| Demographic variables | ||||

| Age, mean (SD) | 33.94 (7.8) | 32.45 (8.2) | 0.43 | 1.01 (0.99-1.03) |

| Female | 105 (70.9) | 342 (61.8) | 1.15a | 1.51 (1.02-2.23) |

| White | 109 (73.6) | 379 (68.5) | 1.44 | 0.78 (0.52-1.17) |

| Education (high school or less) | 50 (33.8) | 139 (25.1) | 4.40a | 1.52 (1.03-2.25) |

| Unemployed | 102 (68.9) | 331 (59.9) | 4.03a | 1.49 (1.01-2.19) |

| Relationship status (not partnered) | 108 (73.0) | 419 (75.8) | 0.49 | 1.16 (0.77-1.75) |

| Clinical variables, controlling for significant demographic variables above | ||||

| MDD | 117 (79.1) | 428 (77.4) | 0.13 | 1.09 (0.69-1.70) |

| PTSD | 70 (47.3) | 143 (25.9) | 17.87c | 2.30 (1.56-3.39) |

| Alcohol use disorder | 85 (57.4) | 197 (35.6) | 22.12c | 2.52 (1.71-3.70) |

| Substance use disorder | 80 (54.1) | 178 (32.2) | 23.04c | 2.61 (1.76-3.86) |

| CSA | 72 (51.4) | 139 (26.7) | 24.78c | 2.73 (1.84-4.06) |

| PD | ||||

| Paranoid | 24 (16.2) | 68 (12.3) | 0.86 | 1.28 (0.76-2.13) |

| Schizotypal | 19 (12.8) | 83 (15.0) | 0.57 | 0.81 (0.47-1.40) |

| Schizoid | 4 (2.7) | 20 (3.6) | 0.66 | 0.63 (0.21-1.91) |

| Borderline (DSM-IV) | 104 (70.3) | 141 (25.5) | 80.30c | 6.53 (4.33-9.85) |

| Borderline (without SIB) | 93 (62.8) | 133 (24.1) | 63.02c | 4.99 (3.35-7.41) |

| Histrionic | 3 (2.0) | 10 (1.8) | .001 | 1.02 (0.27-3.80) |

| Narcissistic | 8 (5.4) | 30 (5.4) | 0.15 | 1.17 (0.52-2.65) |

| Antisocial | 20 (13.5) | 32 (5.8) | 7.80b | 2.43 (1.30-4.53) |

| Avoidant | 85 (57.4) | 261 (47.2) | 3.73 | 1.44 (1.00-2.09) |

| Dependent | 13 (8.8) | 32 (5.8) | 0.58 | 1.31 (0.66-2.60) |

| Obsessive-compulsive disorder | 38 (25.7) | 240 (43.4) | 13.09c | 0.47 (0.31-0.71) |

Abbreviations: CSA, childhood sexual abuse; MDD, major depressive disorder; OR, odds ratio; PD, personality disorder; PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder; SA−, no suicide attempts over follow-up; SA+, suicide attempt over 10 years of follow-up; SIB, self-injurious behavior criterion.

P < .05.

P < .01.

P < .001.

History of childhood sexual abuse, DSM-IV axis I disorders, and DSM-IV PDs at baseline were then entered into individual logistic regression models as factors associated with suicide attempt over follow-up, controlling for significant demographic covariates (Table 1). A history of childhood sexual abuse, PTSD, AUD, and SUD were significant risk factors, each increasing the odds of at least 1 suicide attempt by approximately 2.5 times. While MDD was not a significant risk factor, it was notably the most prevalent disorder experienced by both groups. Of the PDs, BPD and ASPD were both positively and prospectively associated with suicide attempt over follow-up; in contrast, OCPD was associated with significantly lower odds of suicide attempt over follow-up. Borderline personality disorder was associated with an approximate 6.5-fold increase in odds (5-fold increased odds when excluding the self-injurious behavior criterion) of having at least 1 suicide attempt over 10 years.

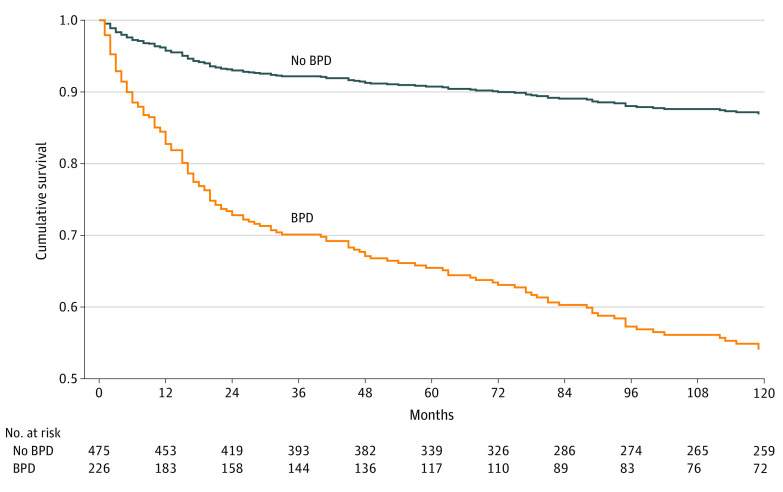

A hierarchical multiple logistic regression model determining baseline factors associated with suicide attempt over follow-up was estimated, including individually significant (1) demographic factors (sex, employment, education), (2) axis I and clinical factors (PTSD, AUD, SUD, and childhood sexual abuse), and (3) PD diagnoses (BPD,2 ASPD, and OCPD; Table 2). Demographics accounted for approximately 2% of the variance. Adding non-PD clinical factors accounted for approximately an additional 12% of the variance. Adding PDs accounted for an additional 11% when modeling BPD excluding self-injurious behavior and an additional 14% of the variance when including the complete BPD criteria. In the final model, only BPD and sexual abuse were significant baseline factors associated with suicide attempt over follow-up; OCPD remained a significant negative risk factor for suicide attempt over follow-up. This association of BPD was also modeled in a Cox proportional hazards regression analysis predicting time to event of the first suicide attempt by baseline BPD status (Figure).

Table 2. Hierarchical Multiple Logistic Regression Analysis of Independently Significant Demographic, Non-PD Clinical, and PD Diagnosis Predictors of SA+ Over 10 Years of Follow-up (N = 701).

| Risk factor | χ2 Model | Χ2 Step | Nagelkerke R2 step | Final | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wald χ2 | OR (95% CI) | ||||

| Step 1. Demographics | |||||

| Female | 8.45a | 8.45a | .02 | .04 | 1.05 (.65-1.68) |

| High school or less | 1.84 | .71 (.43-1.16) | |||

| Employed | .22 | .90 (.58-1.41) | |||

| Step 2. Non-PD clinical | |||||

| Childhood sexual abuse | 61.45b | 53.00b | .14 | 10.11c | 2.12 (1.33-3.36) |

| PTSD | 1.19 | 1.30 (.81-2.08) | |||

| Alcohol use disorder | 3.54 | 1.57 (.98-2.50) | |||

| Drug use disorder | 2.12 | 1.43 (.88-2.32) | |||

| Step 3. PD diagnoses | |||||

| Borderline PD (without SIB) | 117.93b | 56.48b | .25 | 39.58b | 4.18 (2.68-6.52) |

| Antisocial PD | .02 | 1.06 (.51-2.19) | |||

| Obsessive compulsive PD | 10.82c | .47 (.30-.73) | |||

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; PD, personality disorder; PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder; SA+, suicide attempt over 10 years of follow-up; SIB, self-injurious behavior criterion.

P < .05.

P < .001.

P < .01.

Figure. Survival Function for Time to First Suicide Attempt.

BPD indicates borderline personality disorder.

Individual BPD criteria assessed at baseline were examined as factors associated with suicide attempt over follow-up (Table 3). A first set of analyses examines each BPD criterion independently of the others; a second model estimates all BPD criteria simultaneously, except for the self-injurious behavior criterion owing to its overlap with the outcome variable. All models controlled for significant demographic and clinical covariates. When BPD criteria were examined separately, each criterion was positively prospectively associated with suicide attempt over follow-up, with increases of approximately 2 to 3 times the odds of suicidal behavior. However, in the simultaneous model, only 3 criteria emerged as significant independent factors associated with suicide attempt over follow-up: identity disturbance, frantic efforts to avoid abandonment, and chronic feelings of emptiness.

Table 3. Logistic Regression Analyses of BPD Criteria as Prospective Factors Associated With SA+ Over 10 Years of Follow-up, Covarying for Individually Significant Demographic and Clinical Variablesa.

| Variable | No. (%) | Models BPD criteria separately | Multivariable model with all BPD criteria | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n = 701) | SA+ (n = 148) | SA− (n = 553) | Wald χ2 | OR (95% CI) | Wald χ2 | OR (95% CI) | |

| Anger | 302 (45.6) | 102 (68.9) | 218 (39.5) | 22.36b | 2.88 (1.86-4.47) | 1.80 | 1.44 (0.85-2.45) |

| Affective instability | 362 (51.6) | 116 (78.4) | 246 (44.5) | 25.48b | 3.33 (2.09-5.32) | 3.00 | 1.64 (0.94-2.87) |

| Emptiness | 292 (41.7) | 93 (62.8) | 199 (36.1) | 20.18b | 2.61 (1.72-3.98) | 4.36c | 1.63 (1.03-2.57) |

| Identity disturbance | 212 (30.2) | 80 (54.1) | 132 (23.9) | 31.91b | 3.37 (2.21-5.13) | 10.59d | 2.21 (1.37-3.56) |

| Dissociation/paranoid | 218 (31.1) | 79 (53.4) | 139 (25.1) | 18.31b | 2.55 (1.66-3.92) | 0.20 | 1.12 (0.68-1.86) |

| Abandonment | 190 (27.1) | 69 (46.6) | 121 (21.9) | 24.28b | 2.99 (1.93-4.62) | 6.71c | 1.93 (1.17-3.16) |

| Impulsivity | 318 (45.4) | 100 (67.6) | 218 (39.4) | 19.50b | 2.69 (1.73-4.17) | 3.78 | 1.67 (1.00-2.79) |

| Unstable relations | 267 (38.1) | 84 (56.8) | 183 (33.1) | 11.39c | 2.10 (1.37-3.24) | 0.95 | 0.76 (0.44-1.32) |

Abbreviations: BPD, borderline personality disorder; OR, odds ratio; SA+, suicide attempt over 10 years of follow-up; SA−, no suicide attempts over follow-up.

Individually significant relevant demographic and clinical covariates include sex, education, employment, sexual abuse history, posttraumatic stress disorder, alcohol use disorder, drug use disorder, antisocial personality disorder, and obsessive-compulsive personality disorder. Recruitment site was examined as a post hoc control variable. Although suicide attempts were significantly uneven across sites (χ23 = 18.95; P <.001), controlling for site as a structural set of dummy coded variables did not change the patterns of significance in any of the models examined. Where not specified, results presented are based on model excluding self-injurious behavior criterion to minimize potential construct contamination.

P < .001.

P < .05.

P < .01.

Given the strong individual effect sizes for affective instability (OR, 3.33; 95% CI, 2.09-5.32) and anger (OR, 2.88; 95% CI, 1.86-4.47) and a strong association between these 2 criteria (r = 0.45; see the eTable in the Supplement for all intercorrelations), post hoc analyses were conducted to examine whether these criteria became nonsignificant in the combined model owing to correlated variance with suicide attempt over follow-up. Combined models were reanalyzed excluding 1 of 2 criteria. With the anger criterion removed, both the affective instability (χ21, 4.59; OR, 1.80; 95% CI, 1.05-3.09; P = .03) and impulsivity (χ21, 5.19; OR, 1.79; 95% CI, 1.08-2.96; P = .02) criteria became significant factors associated with suicide attempt over follow-up, in addition to identity disturbance, emptiness, and frantic efforts to avoid abandonment. With the affective instability criterion removed, anger remained nonsignificant (χ21, 3.42; OR, 1.62; 95% CI, 0.97-2.71; P = .06), but impulsivity again became an additional significant risk factor (χ21, 4.26; OR, 1.72; 95% CI, 1.03-2.87; P = .04). These results suggest overlap between the affective instability, anger, and impulsivity criteria may account for their falling out of the combined model.

Discussion

This study extends prior work documenting the association between BPD and increased risk in suicidal behavior, finding that a BPD diagnosis was a risk factor for whether participants made a prospectively observed suicide attempt over 10 years of follow-up, even after adjusting for demographic and other clinical variables, including other PDs. Early data from the CLPS study based on 2 years of follow-up identified affective instability as the most robust independent risk factor for suicide attempt, while impulsivity and identity disturbance were significantly associated with self-injurious behaviors (including attempts and behaviors with no intent to die) but not of attempts alone.5 However, after 10 years of follow-up, our results indicate that identity disturbance, frantic efforts to avoid abandonment, and chronic feelings of emptiness were the most robust independent factors associated with suicide attempt over follow-up, when controlling for all other BPD criteria.

Our finding linking identity disturbance, chronic emptiness, and frantic efforts to avoid abandonment to suicide outcomes is one of only a few empirical findings linking these criteria to suicide. These criteria are relatively understudied as potential contributors to suicide risk within BPD, perhaps because impulsivity and affective instability may seem more directly relevant.21 Moreover, few prior studies prospectively examined suicidal behavior, and even fewer across time frames as long as this study. The emptiness finding converges with one study’s finding13 that only this criterion predicted higher levels of suicidality and a greater likelihood of attempting suicide when examining effects of the presence of a sole criterion for BPD in psychiatric outpatients compared with control individuals meeting no BPD criteria.13 However, those findings may not generalize to clinical samples of patients diagnosed as having BPD.

Despite limited empirical work demonstrating direct links between these facets of BPD and suicide, a study3 examining effects of individual BPD criteria on nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI) demonstrated potential effects of identity disturbance and emptiness, consistent with findings in our study. Furthermore, transdiagnostic work found that in young adult samples with and without BPD, momentary increased negative affect was linked to NSSI urges only when clarity about self-concept was low, suggesting a potential facilitative role of identity disturbance in increased risk for self-harm.14 Given the potential for NSSI to increase risk for future suicidal behavior via increased acquired capability for harm to self,22,23 this may be one way these criteria increase suicide risk over time.

Prior work additionally suggests potential theoretical reasons these criteria could contribute to suicide risk over time. The criteria of identity disturbance, chronic emptiness, and frantic efforts to avoid abandonment are represented in the personality functioning dimension of the Alternative DSM-5 Model for Personality Disorders in DSM-5 Section III,24 as well as the International Classification of Diseases, 11th Revision25; this dimension reflects the notion that disturbance in how one views themselves and others is central across personality disorders.26 Accordingly, these criteria may interfere with self-direction, development of meaningful and lasting interpersonal relationships, and engagement in goals and value-directed living, becoming increasingly problematic throughout the life span because these facets of life might otherwise buffer suicidal tendencies. This is consistent with models of suicide that identify thwarted belonging23 and lack of social connectedness27 as key components of risk for suicidal action.

Impulsivity and affective instability were significant risk factors in our study when examined individually and remain integral to understanding suicide risk. Affective instability and impulsivity might be more salient risk factors at a younger age, with criteria related to identity and sense of self more salient in later years.28,29,30,31 In children, impulsivity, emotional dysregulation, and self-harm are key factors associated with future BPD diagnoses.32 In contrast, older adults (ages 45-68 years) with BPD are much less likely to endorse these criteria than younger adults (ages 18-25 years).28 The same study reported no significant age differences in suicidality and suicide attempts, highlighting the consistency in severity of suicidality in BPD across age. Thus, it is possible that different symptoms predict risk of suicide in patients with BPD depending on age, with impulsivity conferring risk particularly in young populations owing to reduced prefrontal cortex and subcortical promotivational circuitry development33 and fewer cognitive control strategies.34 Additionally, the BPD criterion of impulsivity, which assesses specific forms of risky behaviors but does not distinguish between psychological processes contributing to them, may not capture the relatively narrow forms of the broader impulsivity construct most relevant to suicidality in studies over shorter time frames (ie, lack of premeditation and urgency35). Using a multidimensional measure of impulsivity might clarify whether specific facets are also independent risk factors over a longer time frame.

Our results by no means suggest that the commonly associated BPD criteria risk factors of affective instability and impulsivity are unimportant, especially given that in real-world clinical settings, clinicians evaluate risk factors without considering statistical independence. Because these criteria are more observable and are common intervention targets, they should continue to be assessed as part of the overall suicide risk profile. However, our findings regarding identity disturbance, abandonment, and emptiness indicate that these too should be assessed and targeted, particularly because interventions that target this set of criteria typically differ from those targeting affective instability and impulsivity. In light of our knowledge that many individuals with BPD will remit from this disorder, the focus on individual criteria is especially important, particularly because many of these criteria are emphasized in International Classification of Diseases, 11th Revision, and Alternative DSM-5 Model for Personality Disorders as salient to the assessment of personality functioning.

Strengths and Limitations

Strengths of the research design include the large sample size recruited from multiple sites, the carefully diagnosed sample, and the prospective design that includes 10 years of follow-up. There were also several limitations. Assessments were primarily based on interviewer ratings of participants’ self-report back to the time of each prior assessment (typically during 1 year), thus subject to recall biases; however, reliability checks with overlapping intervals suggested participant reports were generally consistent.18,36 Also, our sample was predominantly White and female. Furthermore, we did not assess effect of treatment. While data on treatment were collected, because treatment was naturalistic and quite heterogeneous, examination of treatment effects in prior published work in the sample suggests that treatment use is a proxy for severity.37 While relation of treatment effects and suicidal behavior is an important area of research, it would be inappropriate to analyze treatment effects in a naturalistic study. Finally, it should be cautioned that even in prospective studies, statistically significant findings may or may not translate into clinical prediction.

Conlusions

Overall, the results of this study show the importance of assessing and targeting identity disturbance, abandonment, and emptiness in patients with BPD when considering suicide prevention, symptoms that may often be overshadowed by affective or behavioral features of BPD. These other features that may confer risk of suicidal behavior may help to inform or elaborate contemporary theories of suicidal behavior.

eTable. Descriptives (frequency and percent or mean and standard deviation) and zero-order associations among all demographic and clinical variables

References

- 1.Suicidal thoughts and behavior among adults: results from the 2015. National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Accessed July 8, 2020. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-DR-FFR3-2015/NSDUH-DR-FFR3-2015.htm

- 2.Soloff PH, Lynch KG, Kelly TM, Malone KM, Mann JJ. Characteristics of suicide attempts of patients with major depressive episode and borderline personality disorder: a comparative study. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(4):601-608. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.4.601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brickman LJ, Ammerman BA, Look AE, Berman ME, McCloskey MS. The relationship between non-suicidal self-injury and borderline personality disorder symptoms in a college sample. Borderline Personal Disord Emot Dysregul. 2014;1(1):14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yen S, Shea MT, Pagano M, et al. Axis I and axis II disorders as predictors of prospective suicide attempts: findings from the collaborative longitudinal personality disorders study. J Abnorm Psychol. 2003;112(3):375-381. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.112.3.375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yen S, Shea MT, Sanislow CA, et al. Borderline personality disorder criteria associated with prospectively observed suicidal behavior. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(7):1296-1298. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.7.1296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yen S, Shea MT, Sanislow CA, et al. Personality traits as prospective predictors of suicide attempts. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2009;120(3):222-229. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2009.01366.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wedig MM, Silverman MH, Frankenburg FR, Reich DB, Fitzmaurice G, Zanarini MC. Predictors of suicide attempts in patients with borderline personality disorder over 16 years of prospective follow-up. Psychol Med. 2012;42(11):2395-2404. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712000517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Links PS, Eynan R, Heisel MJ, et al. Affective instability and suicidal ideation and behavior in patients with borderline personality disorder. J Pers Disord. 2007;21(1):72-86. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2007.21.1.72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brodsky BS, Malone KM, Ellis SP, Dulit RA, Mann JJ. Characteristics of borderline personality disorder associated with suicidal behavior. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154(12):1715-1719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chesin MS, Jeglic EL, Stanley B. Pathways to high-lethality suicide attempts in individuals with borderline personality disorder. Arch Suicide Res. 2010;14(4):342-362. doi: 10.1080/13811118.2010.524054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilson ST, Fertuck EA, Kwitel A, Stanley MC, Stanley B. Impulsivity, suicidality and alcohol use disorders in adolescents and young adults with borderline personality disorder. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2006;18(1):189-196. doi: 10.1515/IJAMH.2006.18.1.189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gunderson JG Clinical practice: borderline personality disorder. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(21):2037-2042. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1007358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ellison WD, Rosenstein L, Chelminski I, Dalrymple K, Zimmerman M. The clinical significance of single features of borderline personality disorder: anger, affective instability, impulsivity, and chronic emptiness in psychiatric outpatients. J Pers Disord. 2016;30(2):261-270. doi: 10.1521/pedi_2015_29_193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scala JW, Levy KN, Johnson BN, et al. The role of negative affect and self-concept clarity in predicting self-injurious urges in borderline personality disorder using ecological momentary assessment. J Pers Disord. 2018;32(suppl):36-57. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2018.32.supp.36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR. Attainment and maintenance of reliability of axis I and II disorders over the course of a longitudinal study. Compr Psychiatry. 2001;42(5):369-374. doi: 10.1053/comp.2001.24556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clark LA, Vanderbleek E. Schedule for Nonadaptive and Adaptive Personality. Encycl Personal Individ Differ; 2016:1-4. [Google Scholar]

- 17.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. User’s Guide for the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders SCID-I: Clinician Version. American Psychiatric Pub; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zanarini MC, Skodol AE, Bender D, et al. The collaborative longitudinal personality disorders study: reliability of axis I and II diagnoses. J Pers Disord. 2000;14(4):291-299. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2000.14.4.291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zanarini MC, Gunderson JG, Marino MF, Schwartz EO, Frankenburg FR. Childhood experiences of borderline patients. Compr Psychiatry. 1989;30(1):18-25. doi: 10.1016/0010-440X(89)90114-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keller MB, Lavori PW, Friedman B, et al. The Longitudinal interval follow-up evaluation: a comprehensive method for assessing outcome in prospective longitudinal studies. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1987;44(6):540-548. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800180050009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Linehan MM, Korslund KE, Harned MS, et al. Dialectical behavior therapy for high suicide risk in individuals with borderline personality disorder: a randomized clinical trial and component analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(5):475-482. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.3039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chesin MS, Galfavy H, Sonmez CC, et al. Nonsuicidal self-injury is predictive of suicide attempts among individuals with mood disorders. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2017;47(5):567-579. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Joiner T. Why People Die by Suicide. Harvard University Press; 2007. doi: 10.2307/j.ctvjghv2f [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bach B, First MB. Application of the ICD-11 classification of personality disorders. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18(1):351. doi: 10.1186/s12888-018-1908-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bender DS, Morey LC, Skodol AE. Toward a model for assessing level of personality functioning in DSM-5, part I: a review of theory and methods. J Pers Assess. 2011;93(4):332-346. doi: 10.1080/00223891.2011.583808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klonsky ED, May AM. The three-step theory (3ST): a new theory of suicide rooted in the “ideation-to-action” framework. Int J Cogn Ther. 2015;8(2):114-129. doi: 10.1521/ijct.2015.8.2.114 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morgan TA, Chelminski I, Young D, Dalrymple K, Zimmerman M. Differences between older and younger adults with borderline personality disorder on clinical presentation and impairment. J Psychiatr Res. 2013;47(10):1507-1513. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2013.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peckham AD, Jones P, Snorrason I, Wessman I, Beard C, Björgvinsson T. Age-related differences in borderline personality disorder symptom networks in a transdiagnostic sample. J Affect Disord. 2020;274(9):508-514. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.05.111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Reich DB, Silk KR, Hudson JI, McSweeney LB. The subsyndromal phenomenology of borderline personality disorder: a 10-year follow-up study. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(6):929-935. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.6.929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Soloff PH, Chiappetta L. 10-year outcome of suicidal behavior in borderline personality disorder. J Pers Disord. 2019;33(1):82-100. doi: 10.1521/pedi_2018_32_332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Hennen J, Reich DB, Silk KR. Prediction of the 10-year course of borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(5):827-832. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.5.827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Casey BJ, Jones RM. Neurobiology of the adolescent brain and behavior: implications for substance use disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49(12):1189-1201. doi: 10.1097/00004583-201012000-00005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mischel W, Shoda Y, Rodriguez MI. Delay of gratification in children. Science. 1989;244(4907):933-938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lynam DR, Miller JD, Miller DJ, Bornovalova MA, Lejuez CW. Testing the relations between impulsivity-related traits, suicidality, and nonsuicidal self-injury: a test of the incremental validity of the UPPS model. Personal Disord. 2011;2(2):151-160. doi: 10.1037/a0019978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Skodol AE, Gunderson JG, Shea MT, et al. The collaborative longitudinal personality disorders study (CLPS): overview and implications. J Pers Disord. 2005;19(5):487-504. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2005.19.5.487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bender DS, Skodol AE, Pagano ME, et al. Prospective assessment of treatment use by patients with personality disorders. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57(2):254-257. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.57.2.254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable. Descriptives (frequency and percent or mean and standard deviation) and zero-order associations among all demographic and clinical variables