Cost is often cited as a barrier to equitable access to healthy diets, which is concerning due to the strong links between poor diets and increased risk of several chronic health conditions and decreased immunity.

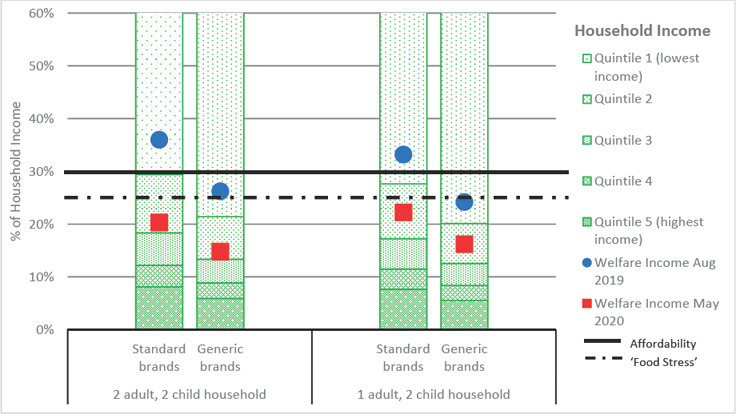

Our Healthy Diets Australian Standardised Affordability and Pricing (HD‐ASAP) protocol1 measures the cost and affordability of a household's usual diet, based on reported intakes in the Australian Health Survey,2 and the cost of a healthy diet, based on the Australian Dietary Guidelines.3 When diet costs more than 25% of disposable income, households are considered to be in ‘food stress’; when more than 30%, healthy diets are considered ‘unaffordable’.4

During the COVID‐19 lockdown from May 2020, a sudden increase in unemployment and underemployment meant many households had reduced incomes. The Australian Government responded by providing an economic support package including cash payments and increased eligibility to access benefits. For low‐income households, recipients of some government benefits were granted special payments of $750 in April and July 2020, and the unemployment benefit (JobSeeker) was increased by a supplement of $550/fortnight.

For households of two adults and two children (aged 14 and 8), we estimated a healthy diet costs $624/fortnight, when pricing included fresh foods together with the most commonly purchased brands of packaged items. If both adults were unemployed, prior to COVID‐19 this would have been unaffordable, costing 36% of household income (Figure 1 ). However, where families were eligible for COVID‐19 economic support, healthy diets were potentially attainable at 20% of household income.

Figure 1.

Affordability of healthy diets for unemployed households.

Source: Quintiles 1–5 from Australian Bureau of Statistics 2016 Census, welfare incomes calculated fromwww.servicesaustralia.gov.au

Before COVID‐19, if these households attempted to reduce food costs by purchasing generic supermarket brands, the healthy diet cost $456/fortnight. This was more affordable than using branded products, but still cost 26% of household income. However, when these families received the COVID‐19 supplements, ‘food stress’ was greatly relieved – with healthy diets costing 15% of household income.

Unemployed single‐parent households (one adult, two children aged 14 and 8) were in a similarly difficult situation pre‐COVID‐19, with a healthy diet that included commonly purchased brands ($459/fortnight) costing 33% of household income (Figure 1). Even when purchasing generic brands, procuring a healthy diet ($336/fortnight) could be stressful, requiring 24% of household income.

With the extra payments due to COVID‐19, purchasing a healthy diet including branded packaged items became affordable (22% of household income), and even more so with the purchasing of generic brands (16% of household income).

Whilst the purchase of the cheaper food items can assist in managing household food budgets, it is only the additional income from the COVID‐19 extra payments that allows families to more easily afford the healthy foods they need.

The exemption of those receiving unemployment benefits from the second $750 payment in July 2020, and the intention of the Australian Government to reduce the coronavirus supplement to $250/fortnight from September 2020 before removing it altogether in January 2021, means that a healthy diet will return to being a source of financial stress or an unaffordable ‘luxury’ for many Australian families.

For several years, many organisations and individuals have called for an increase to unemployment benefits. Following the implementation of the coronavirus supplement, one survey found 83% of welfare‐dependent people reported eating healthier and more regularly compared to pre‐COVID‐19.5 Given our findings of improved affordability of healthy diets during COVID‐19, these survey results are not surprising and confirm the notion that, given the opportunity, low‐income families will prioritise the purchase of healthy food.

Particularly during a global pandemic, the ability to afford a diet that supports health and decreases the risk of co‐morbidities is essential for both long‐term unemployed households and those suffering the stress of a suddenly reduced income. Without adequate income, or lowering of healthy food prices, the health and wellbeing of the most vulnerable Australians will suffer, increasing the pressure on our health and social services and further impacting our economy. The full coronavirus supplement to unemployment benefits should be retained in its entirety – permanently.

Funding

ML was supported by a Research Training Program Scholarship provided by The University of Queensland, and a Top Up Scholarship provided by The Australian Prevention Partnership Centre, The Sax Institute.

Acknowledgments

Research Training Program Scholarship

References

- 1.Lee AJ, Kane S, Lewis M, et al. Healthy diets ASAP - Australian standardised affordability and pricing methods protocol. Nutr J. 2018;17(1):88. doi: 10.1186/s12937-018-0396-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Australian Bureau of Statistics . ABS; Canberra (AUST): 2013. 4324.0.55.002 Microdata: Australian Health Survey: Nutrition and Physical Activity, 2011-12 [Internet]http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/PrimaryMainFeatures/4324.0.55.002?OpenDocument [cited 2017 Nov 12]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Health and Medical Research Council . NHMRC; Canberra (AUST): 2013. Australian Dietary Guidelines - Providing the Scientific Evidence for Healthier Australian Diets. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ward PR, Verity F, Carter P, et al. Food stress in Adelaide: The relationship between low income and the affordability of healthy food. J Environ Public Health. 2013;2013:10. doi: 10.1155/2013/968078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Australian Council of Social Service . ACOSS; Sydney (AUST): 2020. Survey of 955 People Receiving the New Rate of Jobseeker and Other Allowances [Internet]https://www.acoss.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/200624-I-Can-Finally-Eat-Fresh-Fruit-And-Vegetables-Results-Of-The-Coronaviru._.pdf [cited 2020 Jul 29]. Available from: [Google Scholar]