Abstract

Background and Aim

During COVID‐19 outbreak, restrictions to in‐person consultations were introduced with a rise in telehealth. An indirect benefit of telehealth could be better attendance. This study aimed to assess “failure‐to‐attend” (FTA) rate and satisfaction for two endoscopy‐related compulsory telehealth clinics during the COVID‐19 outbreak.

Methods

Consecutive patients booked for endoscopy‐related telehealth clinics at a tertiary hospital were prospectively assessed. In‐person clinic control data were assessed retrospectively. Sample size was calculated to detect an anticipated increase in attendance of 8%. Secondary outcomes included FTA differences between clinics and evaluation of patients and doctors satisfaction. Satisfaction was assessed based on six Likert scale questions used in previous telehealth research and asked to both patients and doctors (6Q_score). This study was exempt from IRB review after institutional IRB review.

Results

There were 691 patients booked for appointments in our endoscopy clinics during the study periods (373 in 2020). FTA rates were lowered by half during the compulsory telehealth clinics (12.6% to 6.4%, P < 0.01). The patient 6Q_score was higher for the advanced endoscopy clinic (84.6% vs 73.8%, P < 0.01), while the doctor 6Q_score was similar between both advanced clinics and post endoscopy clinics (91.1% vs 92.5% respectively, P = 0.80). An in‐person follow‐up consultation was suggested for 3.5% of the appointments, while the necessity of physical examination was flagged in 5.1%.

Conclusions

The use of phone consultations in endoscopy‐related clinics during the COVID‐19 outbreak has improved FTA rates while demonstrating high satisfaction rates. The need for in‐person follow‐up consultations and physical examination were low.

Keywords: COVID‐19, Endoscopy, Outpatient clinic, Telehealth

Introduction

According to the World Health Organization, the COVID‐19 outbreak has reached the status of a pandemic, as per July 2020, there were almost 14 million confirmed cases and almost 600 000 related deaths throughout the globe. 1 One of the many strategies to mitigate the spread of the disease is social isolation. Although this concept is straightforward to determine actions for nonessential/urgent matters (e.g. canceling entertainment‐related social gatherings), it is more difficult to implement when interpersonal contact is necessary (e.g. hospitals and supermarkets). As a manner to address such issue, many hospitals have canceled low‐priority procedures and have advised the departments to shift outpatient consultations to telehealth/phone consultations.

Studies on the use of telehealth as a tool for specialist consultations describe as benefits more timely access to the appointment/specialist opinion and avoidance of travel to the face‐to‐face appointment. 2 , 3 Barsom et al. have evaluated the use of video consultation for the follow‐up of colorectal cancer patients in a tertiary center in the Netherlands. They describe similar patient satisfaction and perceived quality of care when compared with face‐to‐face consultations. However, different from the current scenario, the decision to allocate the patient to either group was made by the patient. 4

Telephone consultations as a method for telehealth do not provide visual cues and limit interpretation of visual signs such as visualization of skin lesions. However, the need of such feedback is almost non‐existent for endoscopy‐related consultations as their purpose is focused. The main foci of endoscopy‐related outpatient clinics are twofold: to inform and consent the patient for an endoscopic procedure that is to be performed in the near future and to explain the results of a recent procedure already performed, for which a copy of the endoscopy report has already been provided to the patient. Therefore, phone consultations might be a good fit for endoscopy‐related outpatient clinics. The practicalities and indications for the use of phone consults has been described by van Galen and Car 5 and fit the previous description.

The aim of this study is to evaluate patient and consultant experiences with phone consultations for endoscopy‐related outpatient appointments during the COVID‐19 outbreak.

Methods

All consecutive patients booked for a telehealth consultation due to the COVID‐19 outbreak with the weekly advanced endoscopy clinic or with the weekly post endoscopy clinic at Austin Health were included for the primary outcome. The data on “failure to attend” (FTA) were compared with retrospective data on exclusively in‐person consultations. This retrospective control consisted of the same number of clinics carried out in a similar period in 2019.

In our institution, the “advanced endoscopy” clinic consists of patients pre‐advanced and post‐advanced endoscopy procedures (e.g. endoscopic ultrasound, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, endoscopic submucosal dissection, and large/piecemeal endoscopic mucosal resection) while the “post endoscopy” clinic is limited solely to the follow‐up after more routine endoscopy procedures (e.g. diagnostic gastroscopy for reflux disease and surveillance colonoscopy of small polyps). We expect that the patient profile did not change from 2019 to 2020 as both clinics had these patient profiles set several years ago. Both the “advanced endoscopy” and the “post endoscopy” clinics have been carried out in the same institution in 2019 and 2020.

For the secondary outcomes, all non‐FTA prospective cohort was assessed for eligibility as per the following criteria:

-

1.

Inclusion criteria

Patients booked for an outpatient consultation in the post endoscopy clinic or advanced endoscopy clinic

Consultation determined to be held through telehealth as per preventive measures due to the COVID‐19 outbreak

Age >18 years

Ability to give informed consent

-

2.

Exclusion criteria

Telehealth consultation performed with a relative as per patient's preference

Patient that is deemed as confused/not able to understand

Unwilling/unable to participate in the post‐consultation survey

Primary outcome

The expected FTA difference between in‐person and telehealth consultations was based on observations of the initial weeks of the telehealth clinics at Austin Health. One of the authors (LZCTP) who attended both clinics has made an estimate on the FTA rates pre‐introduction and post‐introduction of telehealth consultations, which led to an estimated difference of 8% in FTA (2.0% vs 10.0%). This was then used to calculate a sample size for two independent groups with dichotomous variable, enrolment ratio of 1:1, 0.05 two‐tailed alpha error and power of 80%. Conservatively utilizing a 10% safety margin, the prospective collection of data was rounded up to 150 patients per group. Collection of data to ascertain exact numbers for FTA rates only took place after the protocol had been submitted and approved by the local ethics committee.

The FTA definition for the retrospective cohort (in‐person consultations) was of patients that were booked for the outpatient clinic and that did not call/informed they wanted to cancel the appointment beforehand and subsequently did not attend the consultation. For a patient to be deemed as FTA in the prospective (telehealth clinic) group, he/she was called at least three times to one or more of the phone numbers available in the hospital's electronic database.

Secondary outcomes

Patient satisfaction measurement

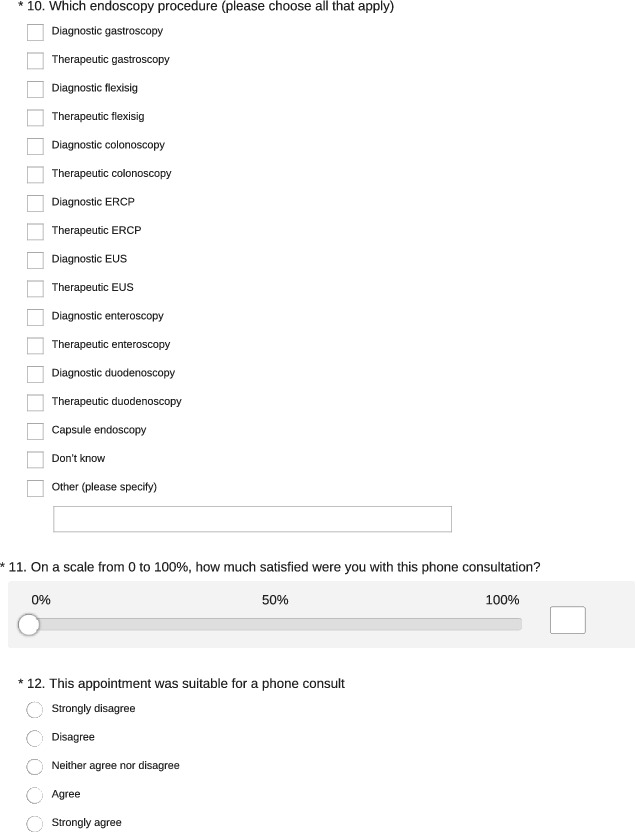

As per previously studied by Barsom et al. 4 and Donnon et al., 6 patients' satisfaction was evaluated with the 10‐item multisource feedback questionnaire. This consists of 5‐point Likert‐scale response mode statements ranging from 1 (Totally agree) to 5 (Totally disagree). To the multisource feedback questionnaire, we have added a question regarding previous consultation with a gastroenterologist/endoscopist, which could potentially influence other questions. In addition, a patient attitude towards phone consult (PAT‐PC) questionnaire was created, adapted from Barsom et al. 4 study. This consisted of 14 items based on the 5‐point Likert scale. These were offered to the patients to be filled through the phone with a doctor different from whom he/she had their consultation with, or to be sent through their email as a link to an electronic survey (Appendix I). If the patient contacted through the phone could not respond to the questionnaire in the first contact attempt or if the patient that accepted to participate through the electronic survey did not respond to it after a week of the appointment, a single phone call was used to remind the patient about the survey. If this was still unsuccessful in retrieving a filled questionnaire, the patient was considered as “unwilling”.

Consultant satisfaction measurement

The consultant satisfaction was evaluated through a 10‐item questionnaire at the conclusion of each consult (one item scoring from 0 to 100 the overall experience with the phone consultation; six items based on the 5‐point Likert scale—adapted from the PAT‐PC questionnaire; and three items yes/no questions based on the study of Barsom et al. 4 ). The six Likert‐scale questions present in the doctor questionnaire are directly relatable to six items in the patient's PAT‐PC questionnaire. Therefore, the direct comparison of patient and doctor satisfaction with the phone consultation was carried out through the comparison of “good responses” (i.e. strongly agree/agree) for these six questions henceforth called 6Q_score. The doctor questionnaire was also filled through an electronic survey (Appendix II).

Statistical analyses

Data was summarized as mean ± standard deviation (SD) for continuous data and as frequency and percentages for categorical data. For continuous data, comparisons were performed using Mann–Whitney U test on the basis of the normality assumption assessed by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Shapiro–Wilk tests. Categorical data were compared with Pearson χ 2 test. A P value of <0.05 was considered significant. Statistical analyses were performed with spss statistical software (IBM Corp. 2020. IBM SPSS Statistics, Version 26.0. Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Between April 15 and May 27, 2020, consecutive patients booked for six post endoscopy clinics and seven advanced endoscopy clinics were assessed for the primary outcome. Similarly, six post endoscopy and seven advanced endoscopy clinics held between April 15 and May 29, 2019, were retrospectively assessed. There were 691 patients booked for appointments at Austin endoscopy‐related clinics during these periods (318 in 2019 and 373 in 2020). The average age was similar between both 2019 and 2020 cohorts (60.6 vs 61.9 years, P = 0.25), as was male gender (43.4% vs 48.7%, P = 0.16)—Table 1.

Table 1.

Full cohort demographics

| 2019 Cohort N = 373 | 2020 Cohort N = 318 | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male—N (%) | 155 (48.7) | 162 (43.4) | 0.07 |

| Age—mean (SD) | 61.9 (14.2) | 60.6 (14.9) | 0.34 |

| Patients booked as phone consultation—N (%) | 0 (0) | 318 (100) | <0.01 |

| Patients booked as face‐to‐face consultation—N (%) | 373 (100) | 0 (0) | <0.01 |

N, total numbers; SD, standard deviation.

The FTA rates were calculated for both prospective (2020) and retrospective (2019) cohorts and were shown to be lowered by half during the COVID‐19 outbreak compulsory phone clinics (12.6% to 6.4%, P < 0.01)—Table 2. The data have been broken down by the individual clinics in Table 3. A flowchart explaining the study has been included for clarity (Fig. 1).

Table 2.

Differences in “failure‐to‐attend” (FTA) between in‐person and phone clinics

| 2019 | 2020 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients booked—N (%) | FTA—N (%) | Patients booked—N (%) | FTA—N (%) | P value | |

| Advanced endoscopy clinic | 145 (45.6) | 17 (11.7) | 162 (43.4) | 7 (4.3) | 0.02 |

| Post endoscopy clinic | 173 (54.4) | 23 (13.3) | 211 (56.6) | 17 (8.1) | 0.09 |

| Total | 318 (100) | 40 (12.6) | 373 (100) | 24 (6.4) | <0.01 |

N, total numbers.

Table 3.

2020 Detailed cohort demographics

| 2020 Cohort breakdown | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Advanced endoscopy N = 162 | Post endoscopy N = 211 | ||

| Age—mean (SD) | 61.7 (15.2) | 59.7 (14.8) | 0.21 |

| Unwilling—N (%) | 42 (27.1) | 39 (20.1) | 0.22 |

| All ineligible—N (%) | 21 (13.5) | 30 (15.5) | |

| Ineligible due to language barrier—N (%) | 6 (3.9) | 18 (9.3) | |

| Web‐based—N (%) | 69 (44.5) | 85 (43.8) | |

| Over‐the‐phone—N (%) | 23 (14.8) | 40 (20.6) | |

| Duration of consult in minutes—mean (SD) | 10.9 (6.3) | 14.3 (8.5) | <0.01 |

| Overall doctor satisfaction in %—mean (SD) | 97.6 (48.6) | 93.1 (47.0) | <0.01 |

| Doctor 6Q_score in %—mean (SD) | 91.1 (46.6) | 92.5 (47.7) | 0.80 |

| Patient 6Q_score in %—mean (SD) | 84.6 (43.1) | 73.8 (39.9) | <0.01 |

N, total numbers; SD, standard deviation.

Figure 1.

Study flowchart. [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

The satisfaction profiles were assessed only in the prospective cohort, for eligible patients that verbally consented in participating in the survey. Two hundred seventeen patient questionnaires were successfully completed (56% of the prospective cohort) compared with 257 doctor questionnaires (68% of the prospective cohort). The mismatch of doctor to patient satisfaction questionnaires completed were due to issues including initial verbal consent being withdrawn or the web‐based survey not being completed even after a one‐time post clinic contact. In the 2020 cohort, the average phone consult duration was slightly longer for the post endoscopy clinic (11 min vs 14 min, P < 0.01), even though it showed a lower patient 6Q_score (84.6% vs 73.8%, P < 0.01) and overall score (97.6% vs 93.1%, P < 0.01). The doctor 6Q_score was similar between the advanced and post endoscopy clinics (91.1% vs 92.5%, respectively, P = 0.80). Indirect satisfaction for patients and doctors (6Q_score) has been summarized in Figures 2 and 3. In the subanalysis of confounding factors for the outcome of patient's satisfaction assessed through the 6Q_score, four confounders were controlled for. No difference was found in patient 6Q_score between male and female patients; patients on their first consultation with a gastroenterologist/endoscopist about the current medical problem; and between patients pre/post endoscopic procedure (P = 0.43; P = 0.45; and P = 0.12, respectively). A follow‐up consultation was suggested to be carried out in‐person for only 3.5% of the appointments, while the necessity of physical examination was flagged in only 5.1%.

Figure 2.

Patient satisfaction summary (6Q_score).  , Strongly agree;

, Strongly agree;  , Agree;

, Agree;  , Neutral;

, Neutral;  , Disagree;

, Disagree;  , Strongly disagree. [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

, Strongly disagree. [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Figure 3.

Doctors satisfaction summary (6Q_score).  , Strongly agree;

, Strongly agree;  , Agree;

, Agree;  , Neutral;

, Neutral;  , Disagree;

, Disagree;  , Strongly disagree. [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

, Strongly disagree. [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Discussion

Because of the COVID‐19 pandemic, social distancing has been recommended throughout the globe. This had several immediate effects in most workplaces and, within outpatient clinics, was translated into the adoption of telehealth consults whenever possible. The two most common modalities of telehealth in outpatient clinics are phone and video consults. Despite potentially improving the consult experience due to image/video input, video consultations are dependable on available software (which was not set up at the early stages of the pandemic) and participants' technology expertise. Therefore, only phone consults have been used in our endoscopy‐related telehealth clinics in the first few months of the COVID‐19 outbreak.

The results of this study suggest that a better attendance was achieved when the consult was carried over the phone rather than in‐person. Despite the in‐person attendance rate was not able to be assessed prospectively, this finding supports the use of phone consults as an alternative that could potentially lead to an optimized use of health‐care resources. This was true for less complex clinics (e.g. advices regarding colonoscopy intervals after a polyp was removed) and more complex clinics (e.g. investigation of pancreatic lesion with endoscopic ultrasound) alike.

Potential savings of this strategy are there for both the patients and the health service. A conservative estimation only accounting for parking/fuel/transportation costs could be for patients to save AUD 10 per appointment. This would lead to savings of around AUD 30 000 a year (approximately 3000 patients in both endoscopy‐related clinics per year). As per the health service, with the anticipated lower FTA rate for a year, an extra 180 to 200 patients could be seen, increasing efficiency and potential revenue. Both clinics account for about only 1% of all appointments of specialist clinics held at Austin Health; what highlights that the potential benefit of telehealth can be much higher. Therefore, we believe that this is likely a valid option even after COVID‐19 for endoscopy‐related clinics and potentially a good option for other outpatient clinics where face‐to‐face consultations are not required.

In our study, we have identified high satisfaction with both doctors and patients, but the results were better among doctors. A comparative analysis was performed based on the six Likert scale questions that are found in both doctor's and patient's questionnaires (Appendices I and II). This was considered as indirect satisfaction. Although both describe high indirect satisfaction, the rate of agree/strongly agree was lower for patients (78.4% vs 91.9%, P < 0.01). When using a direct scale for doctor satisfaction (0–100%), a high score was found for both clinics but was slightly higher for the advanced endoscopy clinic (97.6% vs 93.1%, P < 0.01), but interestingly, the indirect satisfaction was similar between the advanced and post endoscopy clinics (91.1% vs 92.5%, P = 0.80).

Because of the COVID 19 outbreak, all our consults became telehealth consults from March 2020. In contrast, all the consults for our endoscopy‐related clinics in 2019 were carried out face‐to‐face. For safety purposes, the patients were not allowed to choose face‐to‐face consultations themselves. Only if the doctor deemed necessary, the consultation would then be carried out face‐to‐face with adequate personal protective devices. There were no cases that were flagged before consultation as requiring a face‐to‐face appointment during the prospective collection of data (2020). Therefore, we understand that a patient selection bias towards face‐to‐face or telehealth is absent in this scenario.

The limitations of this study include the retrospective assessment of the in‐person cohort, the difference in questionnaires for doctors and patients, and the use of a sole modality of telehealth (i.e. phone consults). Specifically, our ability to only assess the secondary outcome in our prospective (phone consult) cohort impairs this study to compare satisfaction of face‐to‐face versus phone consults. Another limitation is the lack of direct comparison of the overall experience with the phone consult between doctors and patients. This has been partially addressed with the comparison between the six relatable questions (6Q_score), but future research including a direct comparison is warranted. Nevertheless, the current results provide input on the potential benefits of the use of telehealth in endoscopy‐related clinics, which may extend to other clinics within the health‐care network that do not require face‐to‐face consultations.

Several factors can negatively affect attendance, and many likely got worse by the COVID‐19 outbreak. This means that we would expect an even higher FTA rate in 2020 compared with 2019. Therefore, we could also look at the use of retrospective data as a strength rather than a weakness in the current scenario. The prospective collection of data on face‐to‐face attendance during 2020 is likely to be biased and not representative of times without the pandemic. Contrastingly, phone consultations likely nullify the effect of several of these factors (e.g. lockdown, fear of COVID‐19, and travel restrictions). Although some bias could shift the patient satisfaction towards telehealth (e.g. fear of attending a consult in‐person), we understand that the results concerning our primary outcome (FTA rates) are reliable and representative.

In conclusion, the use of phone consultations in endoscopy‐related clinics during the COVID‐19 outbreak has improved FTA rates in our institution while maintaining high satisfaction rates for both patients and doctors. The need for in‐person follow‐up consultations and physical examination were low. These data suggest that employing telehealth for endoscopy‐related clinics is a viable alternative, which might be cost effective to maintain even after the COVID‐19 outbreak is over.

Patient questionnaire.

Doctor questionnaire.

Zorron Cheng Tao Pu, L. , Singh, G. , Rajadurai, A. , Terbah, R. , De Silva, R. , Vaughan, R. , Efthymiou, M. , and Chandran, S. (2021) Benefits of phone consultation for endoscopy‐related clinics in the COVID‐19 pandemic. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 36: 1064–1080. 10.1111/jgh.15292.

Declaration of conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflict of interests for this article.

Author contribution: Leonardo, Anton, Rhys, Marios, and Sujievvan conceptualized and designed the study. Sujievvan was responsible for the study supervision. All authors were involved in data extraction. Leonardo and Ryma were involved in the statistical analyses. All authors helped with the interpretation of the results and drafting of the manuscript. Rhys, Marios, and Sujievvan carried out the critical revision of the article for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript. All manuscript drafts and editing were made solely by the authors.

Ethical approval: This study was approved by the Research Office at Austin Health as a Quality & Service Improvement project under the reference RiskmanQ Number: 38839.

Statement of previous publication: The authors confirm that this manuscript is original and that its content (in part or in full) has not been concurrently submitted or previously published in any other medical journal.

References

- 1. Organization WH . WHO coronavirus disease (COVID‐19) dashboard. 2020.

- 2. Vimalananda VG, Orlander JD, Afable MK et al. Electronic consultations (E‐consults) and their outcomes: a systematic review. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2020; 27: 471–479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Constanzo F, Aracena‐Sherck P, Hidalgo JP et al. Contribution of a synchronic teleneurology program to decrease the patient number waiting for a first consultation and their waiting time in Chile. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2020; 20: 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Barsom EZ, Jansen M, Tanis PJ et al. Video consultation during follow up care: effect on quality of care and patient‐ and provider attitude in patients with colorectal cancer. Surg. Endosc. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. van Galen LS, Car J. Telephone consultations. BMJ 2018; k1047: 360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Donnon T, Al Ansari A, Al Alawi S, Violato C. The reliability, validity, and feasibility of multisource feedback physician assessment: a systematic review. Acad. Med. 2014; 89: 511–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]