Abstract

Background

COVID-19 pneumonia exhibits several extra-pulmonary complications.

Case presentation

A 23-year old, asthmatic male with coronavirus pneumonia developed with generalized, acute abdominal pain. Further evaluations revealed a mild ascites and portal vein thrombosis although the patient received proper anticoagulation therapy. Routine lab data regarding the secondary causes of portal vein thrombosis were normal.

Conclusion

We speculated that the underlying cause of portal vein thrombosis in our case was coronaviruses. Therefore, clinicians should always consider thrombosis and other hypercoagulable diseases in patients with COVID-19.

Keywords: COVID-19, Pneumonia, Portal vein, Thrombosis

Background

Novel Coronavirus pneumonia was first described as pneumonia of unknown cause in Wuhan, China, at the end of 2019 [1] and rapidly became pandemic. With time, some new extra-pulmonary manifestations of this viral pneumonia were described. Increased incidence of thromboembolic events was frequently reported [2].

Herein, we aim to describe a 26-year-old male with COVID-19 pneumonia and acute Portal Vein Thrombosis (PVT).

Case presentation

A 26-year-old male, a known case of asthma, was brought to the Emergency Department (ED) in Faghihi hospital, Shiraz, Iran, on 11 April 2020 due to acute-onset dyspnea and a decrease in the level of consciousness since the day of admission. He was admitted with the impression of an acute asthma attack. There was no history of fever, hemoptysis, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting (N/V), lower gastrointestinal tract bleeding, incontinence, and stroke signs and symptoms. He had asthma for several years and only used the salbutamol inhaler as needed. His social history was positive for alcohol, cigarette smoking, and occasionally marijuana.

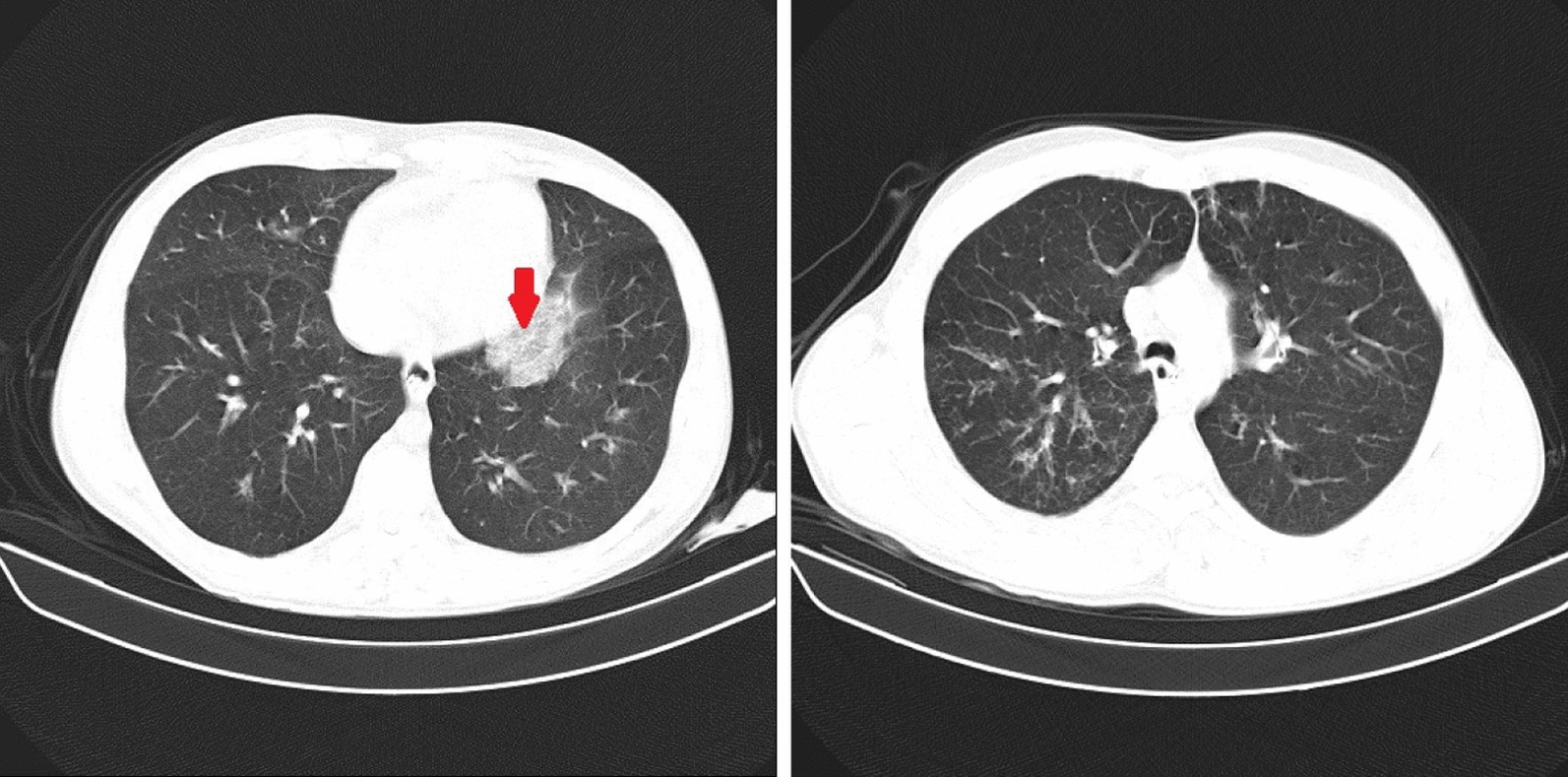

We intubated the patient due to severe hypoxia and respiratory distress; blood Oxygen saturation (O2 Sat.) was 60% and 97% before and after intubation, respectively. The initial vital signs included temperature: 36.9 °C, pulse rate: 110/min, respiratory rate: 36/min, and blood pressure: 120/90 mmHg. Generalized wheezing was heard through auscultation. Other physical findings were normal. Brain computed tomography (CT) was normal. Chest CT showed bilateral peripheral and peribronchovascular patchy ground-glass opacities in both lung fields with tree-in-bud appearance (Fig. 1).The tracheal aspirate was positive for real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) for SARS-COV2. The blood routine tests are summarized in Table 1.

Fig. 1.

Chest CT showed bilateral peripheral and peribronchovascular patchy ground glass opacities (arrow) in both lungs with tree-in-bud appearance

Table 1.

A breif summery of blood routine tests

| Tests | 11 April | 15 April | 16 April | 21 April | 29 April | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Result | ||||||

| WBC (*103/µL) | 18.1 | 14.1 | 8.6 | 9.2 | 5.4 | 4.8–10.8 |

| NE (%) | 68 | 93.3 | 90.5 | 85.5 | 65.3 | 40–80 |

| LY (%) | 12 | 4.9 | 7.1 | 12.1 | 22.2 | 20–40 |

| Hb (g/dL) | 14.7 | 10.7 | 9.4 | 10.9 | 10 | 13.5–18 |

| MCV (fL) | 92.3 | 90.1 | 91.7 | 83.9 | 89.5 | 81–98 |

| Plt (* 109/L) | 213 | 93 | 78 | 127 | 171 | 150–450 |

| PT (s) | 19.2 | N.A | 17.2 | 20.1 | N.A | 11–14 |

| aPTT (s) | 28 | N.A | 29 | 29 | N.A | 27–35 |

| Cr (mg/dL) | 1.3 | 1 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 17 | 07–1.4 |

| BUN (mg/dL) | 21 | 21 | 21 | 18 | 1 | 6–23 |

WBC white blood cell, NE neutrophil, LY lymphocye, Hb hemoglobulin, MCV mean corpuscular volume, fL femotoliter, Plt platelet, PT prothrombin time, aPTT activated partial thromboplastin time, Cr creatinine, BUN blood urea nitrogen level, NA not available

Electrocardiography showed sinus tachycardia, and other findings were normal. Urine analysis was positive for marijuana, benzodiazepine, and morphine. Venous Blood gas analysis was as follows: pH 6.97, partial pressure of carbon dioxide (PCO2) = 103 mmHg, and venous bicarbonate level (HCO3) = 23 mmol/L. We started the initial treatment immediately with dexamethasone (4 mg, IV every 8 h), Piperacillin/tazobactam (3.375 g, IV every 6 h), prophylactic heparin (5000 IU every 12 h). Due to significant patient-ventilator asynchrony, the patient was paralyzed with cisatracurium in addition to midazolam and propofol. During the mechanical ventilation course, he developed progressive thrombocytopenia (Table 1), but no apparent cause was found. Therefore, intravenous immunoglobulin (25 g per day for 3 days) was prescribed empirically for presumed SARS-COV2-induced thrombocytopenic purpura as idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. His respiratory condition got better during the next 5 days when we started weaning the patient off the mechanical ventilation, and he was extubated on 16 April 2020, but thrombocytopenia persisted.

On 21 April 2020 (10 days after admission), the patient developed upper GI bleeding associated with generalized abdominal pain with distension. Upper GI endoscopy was normal, except for the presence of minimal erythema and congestion in the cardia and fundus. No esophageal and fundal varices and duodenal ulcers were reported. Abdominopelvic Sonography showed mild free fluid in the abdominal cavity. The diagnostic abdominal tap was done, and the results are summarized in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 2.

f.Alb, Albumin of ascitic fluid

| Tests | 21 April | 29 April | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Results | |||

| f.Alb (g/dL) | 1.6 | N.A | |

| f.pro (g/dL) | 2.7 | N.A | |

| AST (U/L) | 44 | 40 | 2–37 |

| ALT (U/L) | 67 | 45 | 2–41 |

| Alk.p (U/L) | 138 | 138 | 64–306 |

| Amylase (U/L) | 42 | 42 | 20–100 |

| Lipase (U/L) | 15 | 17 | 5–60 |

| T.B (mg/dL) | 1.41 | 2.44 | 0.1–1.2 |

| D.B (mg/dL) | 0.27 | 0.98 | 0–0.3 |

| Serum Alb (g/dL) | N.A | 2.8 | 3.5–5.3 |

| Serum protein (g/dL) | N.A | 4.6 | 6.6–8.6 |

| TIBC (µg/dL) | 277 | N.A | 230–440 |

| sFe (µg/dL) | 49 | N.A | 40–168 |

f.pro protein of ascitic fluid, AST aspartate transaminase, ALT alanine transaminase, Alk.p alkaline phosphatase, T.B total bilirubin, D.B direct bilirubin, TIBC total iron-binding capacity, sFe serum iron, NA not available

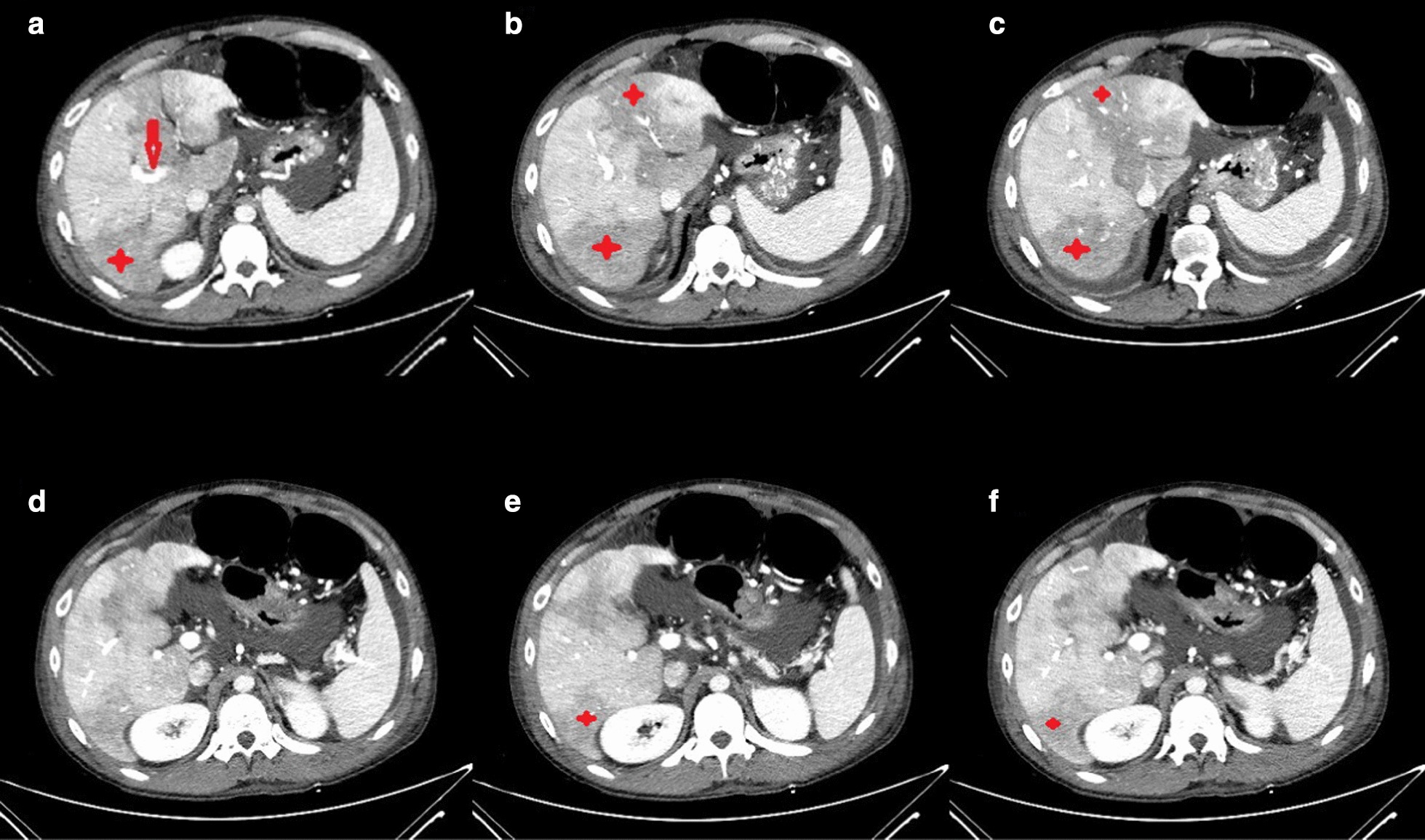

Regarding concomitant abdominal pain and abnormal liver biochemistries (Table 2), abdominal CT was requested which showed hypoperfused areas in the posterior segment of the right (Rt.) hepatic lobe and the medial and lateral segments of left (Lt.) lobe along with evidence of filling defect in the main Rt. Portal vein. Also, the Lt. portal vein was not opacified (Fig. 2). Color Doppler Sonography (CDS) of the abdomen showed the absence of flow in the portal vein without collateral veins consistent with acute portal vein thrombosis. An extensive evaluation of the possible underlying hypercoagulable state was unremarkable (Table 3).

Fig. 2.

Abdominopelvic CT with IV contast. Hypoperfusion is seen in the posterior segment of right (Rt.) hepatic lobe, and the medial and lateral segments of left (Lt.) lobe (stars). Evidence of filling defect in main Rt. portal vein is also detected (arrow)

Table 3.

Laboratory findings in the patient

| Tests | Result | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| C3 (mg/dL) | 130 | Adults: 90–180 |

| C4 (mg/dL) | 29 | 100–40 |

| LAC (s) | 40.8 | 28–42 |

| Protein C (%) | 81 | 65–160 |

| Protein S (%) | 89.8 | 65–150 |

| Factor V Leiden (s) | 91.6 | ≥ 120 |

| Anti-thrombin (%) | 123 | 70–140 |

| ASMA | N | Up to 1:10 |

| ANA (U/mL) | 7 | Negative: < 12 |

| Borderline: 12–18 | ||

| Positive: > 18 | ||

| Anti-ds-DNA (U/mL) | 1.3 | Negative: < 12 |

| Borderline: 12–18 | ||

| Positive: > 18 | ||

| β2 glyco-IgG (U/mL) | 52.8 | Negative: < 12 |

| Equivocal: 12–18 | ||

| Positive: > 18 | ||

| β2 glyco-IgM (U/mL) | 2.4 | Negative: < 12 |

| Equivocal: 12–18 | ||

| Positive: > 18 |

LAC lupus anticoagulant, ASMA anti-smooth muscle antibody, N negative, ANA antinuclear antibody, β2 glyco-IgG beta-2 glycoprotein immunoglobulin G antibody, β2 glyco-IgM beta-2 glycoprotein immunoglobulin M antibody

When gastrointestinal bleeding was stopped, Enoxaparin was started at a minimum effective dose of 1.5 IU/kg/day (60 IU every 12 h) regarding recent thrombocytopenia and risk of gastrointestinal re-bleeding. After about 1 week, his abdominal pain well improved, and platelet count became normal, and finally the patient was discharged with oral warfarin. Unfortunately, patient did not come to our OPD clinic for follow up and further investigation.

Discussion

Herein, we report a coincidence of the acute portal vein thrombosis and COVID-19 respiratory pneumonia in the background of an acute asthma attack. PVT is a rare venous thromboembolic disease typically occurring in patients with an underlying disease such as decompensated cirrhosis and/or malignancies, pancreatitis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and other hypercoagulable states [2]. Our patient did not have any of the mentioned risk factors. There is some unproven concern about the increased thrombotic event during or early after IV immunoglobulin exists. Still, no episode of portal vein thrombosis is linked to IVIG to date [3]. Several studies showed that thromboembolic events increased in patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection since the pandemic declared by the World Health Organization (WHO) [4–6]. In previous studies, thromboembolic events were pulmonary emboli, deep venous thrombosis (DVT), and cerebral infarction usually occurring in the elderly with severe COVID-19 and comorbid diseases such as hypertension and diabetes [5–8]. To the best of our knowledge, our patient is the third case with PVT. The first was a 79-year old female without unknown medical comorbidities who had diarrhea and epigastric abdominal pain and acute dyspnea 8 days after abdominal pain [9]. The second case was a 72-year-old male with Parkinson’s disease and mild vascular dementia who was suffering from jaundice, fever, hypotension, elevated liver enzyme, and acute kidney injury. At first, he was admitted with the impression of Escherichia Coli sepsis. Therefore, he received proper antibiotic regimen, but the fever was not resolved [10]. However, in our study, the patient was a young man without any significant comorbidities, except for a history of asthma and chronic alcohol consumption.

The exact pathophysiology of the increased prevalence of thromboembolism events in COVID-19 positive patients remains unclear [5]. However, immobilization and hypoxemia, as seen in our patient at the time of admission along with the increase in inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-6 (IL-6), IL-10, and Tumor Necrosis Factor Alfa (TNF-α) are the possible mechanisms [11–13]. Unfortunately, we cannot assess the serum level of these cytokines. The attachment of the viruses to the endothelial surfaces via angiotensin-converting enzyme receptor (ACE-R), leads to the lymphocytic endothilitis, interferon-1 (INF-1), and prothrombotic genes overexpression [14]. Becker speculated that the attachment of COVID-19-related extracellular RNA to the factor XI and XII which belongs to the contact pathway of the coagulation cascade leads to the interferon-γ (INF-γ) suppression and a hyper-inflammatory state [15]. Our patient was a smoker. Smoking has been deemed as a risk factor for severe COVID pneumonia and a minor risk factor for thrombotic event which may potentiate the above-mentioned hypercoagulable state [16].

Conclusion

Our report of portal vein thrombosis in the setting of COVID-19 pneumonia adds portal vein thrombosis to other COVID-19 associated thrombotic phenomenon and denotes that the clinician who cares for these patients should have a high index of suspicion to diagnose this unusual presentation in a proper clinical scenario.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- PVT

Portal vein thrombosis

- ED

Emergency department

- N/V

Nausea and vomiting

- CT

Computed tomography

- CXR

Chest X-ray

- RT-PCR

Real-time polymerase chain reaction

- Rt.

Right

- Lt.

Left

- CDS

Color doppler sonography

- WHO

World health organization

- DVT

Deep venous thrombosis

- IL

Interleukin

- ACE-R

Angiotensin-converting enzyme receptor

- INF

Interferon

Authors’ contributions

R.B., R.S, M.F., and Z.M. contributed to the design and implementation of the research, to the analysis of the results and the writing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or gathered during this study are not publicly available given our commitment to patient privacy rights. However, anonymous data may be requested from the corresponding author for valid use.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This case report was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences. We also declare that this patient has not been reported in any other submission by the authors or anyone else.

Consent for publication

A written consent form was assigned by the patient.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Jiang F, Deng L, Zhang L, Cai Y, Cheung CW, Xia Z. Review of the clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) J Gen Internal Med. 2020;35:1545–1549. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-05762-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klok FA, Kruip M, van der Meer NJM, Arbous MS, Gommers D, Kant KM, et al. Confirmation of the high cumulative incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19: an updated analysis. Thromb Res. 2020;191:148–150. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Basta M. Intravenous immunoglobulin-related thromboembolic events—an accusation that proves the opposite. Clin Exp Immunol. 2014;178:153–155. doi: 10.1111/cei.12551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhou B, She J, Wang Y, Ma X. Venous thrombosis and arteriosclerosis obliterans of lower extremities in a very severe patient with 2019 novel coronavirus disease: a case report. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2020;50(1):229–232. doi: 10.1007/s11239-020-02084-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhou B, She J, Wang Y, Ma X. A case of coronavirus disease 2019 with concomitant acute cerebral infarction and deep vein thrombosis. Front Neurol. 2020;11:296. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.00296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bozzani A, Arici V, Franciscone MM, Danesino V, Cascina A, Ticozzelli G, et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection and the upper limb deep vein thrombosis risk. Ann Vasc Surg. 2020;66:11–3. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2020.04.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cui S, Chen S, Li X, Liu S, Wang F. Prevalence of venous thromboembolism in patients with severe novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(6):1421–4. doi: 10.1111/jth.14830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dmytriw AA, Vulkanov V, Agarwal S, Khaneja A, Turkel-Parella D, Liff J, et al. Etiologic Subtypes of Ischemic Stroke in SARS-COV-2 Virus patients. Front Neurol. 2020;11(1004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.de Barry O, Mekki A, Diffre C, Seror M, El Hajjam M, Carlier R-Y. Arterial and venous abdominal thrombosis in a 79-year-old woman with COVID-19 pneumonia. Radiol Case Rep. 2020;15(7):1054–1057. doi: 10.1016/j.radcr.2020.04.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.La Mura V, Artoni A, Martinelli I, Rossio R, Gualtierotti R, Ghigliazza G, et al. Acute portal vein thrombosis in SARS-CoV-2 infection: a case report. Off J Am Coll Gastroenterol. 2020;115(7):1140–1142. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000000711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. The Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barco S, Konstantinides SV, Investigators CT. Thrombosis and thromboembolism related to COVID-19 A clarion call for obtaining solid estimates from large-scale multicenter data. Res Pract Thromb Haemost. 2020;4:741–743. doi: 10.1002/rth2.12364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Connors JM, Levy JH. Thromboinflammation and the hypercoagulability of COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18:1559–1561. doi: 10.1111/jth.14849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sharma A, Garcia G, Arumugaswami V, Svendsen CN. Human iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes are susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 infection. Cell Rep Med. 2020;1(4):100052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Becker RC. COVID-19 update: Covid-19-associated coagulopathy. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2020;50(1):54–67. doi: 10.1007/s11239-020-02134-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vardavas CI, Nikitara K. COVID-19 and smoking: a systematic review of the evidence. Tob Induc Dis. 2020;18–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or gathered during this study are not publicly available given our commitment to patient privacy rights. However, anonymous data may be requested from the corresponding author for valid use.