Abstract

Opioid use and misuse is a problem that is complex and widespread. Opioid misuse rates are rising across all U.S. demographics, including among pregnant women. The opioid epidemic brings a unique set of challenges for maternity health care providers, ranging from ethical considerations to the complex medical needs and risks for both woman and fetus. This article addresses care for pregnant women during the antepartum, intrapartum and postpartum periods through the lens of the opioid epidemic, including: screening and counseling, a multidisciplinary approach to prenatal care, maternal legal considerations, and considerations for care during labor, birth and postpartum. Providers can be trained to identify women at-risk through the evidence-based process of Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) and connect them with the appropriate care to optimize outcomes. Women at moderate risk for opioid use can be engaged in a brief conversation with their provider to discuss risks and enhance motivation for healthy behaviors. Women with risky opioid use can be given a warm referral to pharmacologic treatment programs, ideally comprehensive prenatal treatment programs where available. Evidence regarding care for the pregnant woman with opioid use disorder and practical clinical recommendations are provided.

Keywords: opioid, SBIRT, screening, pregnancy, postpartum, buprenorphine, pharmacotherapy, neonatal opioid withdrawal syndrome, neonatal abstinence syndrome

Précis

An overview and guide to maternity care for women with opioid use disorder during pregnancy and in the postpartum period is provided.

INTRODUCTION

The United States is experiencing an epidemic of opioid use, misuse, and overdose, with 91 deaths each day due to opioid overdose.1 Opioids diminish the intensity of pain in the body and may create a euphoric feeling, which can lead to their misuse.2 Opioid misuse is the use of any opioid, including prescription opioid medications (eg, oxycodone, hydrocodone, morphine, methadone, fentanyl) or illegal opioids (eg, heroin), in a manner, situation, amount, or frequency that can cause harm to users or to those around them.3 Opioid use disorder (OUD) is a chronic medical condition characterized by tolerance, craving, inability to control use, and continued use of opioids despite adverse consequences.4 OUD is a type of addiction, a primary chronic disease of brain reward, motivation, memory and related circuitry. Definitions are shown in Table 1.5–8

Table 1:

Definitions of opioid use, misuse and opioid use disorder.

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Opioid use5 | Continuous or intermittent consumption of an opioid |

| Opioid misus5 | The use of any opioid in a manner, situation, amount, or frequency that can cause harm to users or to those around them. |

| Opioid use disorder6, 7 | Pattern of opioid use characterized by tolerance, craving, inability to control use and continued use despite adverse consequences. To be diagnosed with an opioid use disorder, a person must have 2 or more of the following symptoms within a 12-month period of time (from the following categories): Loss of control Social problems Risky use Pharmacological Problems An opioid use disorder may be mild, moderate, or severe, based on the number of symptoms present. |

| Addiction9 | Primary, chronic disease of brain reward, motivation, memory and related circuitry. Dysfunction in these circuits leads to characteristic biological, psychological, social and spiritual manifestations. This is reflected in an individual pathologically pursuing reward and/or relief by substance use and other behaviors. Addiction is characterized by inability to consistently abstain, impairment in behavioral control, craving, diminished recognition of significant problems with one’s behaviors and interpersonal relationships, and a dysfunctional emotional response. Like other chronic diseases, addiction often involves cycles of relapse and remission. Without treatment or engagement in recovery activities, addiction is progressive and can result in disability or premature death. |

Between 2008–2012, more than a quarter (28%) of reproductive age women with commercial health insurance and more than a third (39%) of reproductive age women with Medicaid filled an opioid prescription.9 This is particularly concerning because women are at higher risk for developing OUD than are men. Compared to men, women are more likely to experience pain as severe,10 to develop chronic pain,11 and to be prescribed opioids for pain management.11 Women are also more likely to move from opioid use to OUD more quickly than men, a process known as “telescoping.”12,13 Opioid overdose deaths are increasing more rapidly among women than men,14 and in 2017, more women died of opioid overdose than motor vehicle accidents.14

Opioid use by pregnant women has also shown a marked increase, mirroring the larger epidemic. A definitive relationship between opioid misuse and teratogenic effects has yet to be established; however, an association between intrauterine opioid exposure and risk of heart defects, neural tube defects, and gastroschisis has been identified in epidemiologic case control studies.15,16 Fetotoxic effects of opioids include intrauterine growth restriction, preterm birth, low birth weight, and intrauterine fetal demise.16 Following birth, opioid-exposed infants are at risk for developing neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS). In addition maternal postpartum relapse and death can occur.15,16 The number of births complicated by maternal OUD during pregnancy in the United States increased more than four-fold between 1999 and 2014,17 resulting in a parallel increase in the incidence of NAS.18 NAS is a constellation of symptoms characterized by central and autonomic instability after prenatal exposure to substances and may require supportive inpatient treatment.19,20 Recently, neonatal opioid withdrawal syndrome (NOWS) has been recognized as a type of NAS with specific opioid-related symptoms.21

Current recommendations for treating women with OUD during pregnancy emphasize behavioral therapy and access to pharmacotherapy, including methadone, buprenorphine (Subutex) or buprenorphine/naloxone (Suboxone).6 Two recent systematic reviews have found that detoxification, defined as assisted or unassisted withdrawal from opioids without initiation of pharmacotherapy, increases the risk of relapse.22,23 However, despite current recommendations, the majority of pregnant women with OUD do not receive pharmacotherapy during pregnancy.24 Roper, et al summarized prenatal considerations for women with opioid use disorder in a review that highlighted the importance of pharmacotherapy treatment programs to avoid the risk of relapse and adverse effects on the fetus.25 Buprenorphine is generally preferred over methadone given its equivalent safety and efficacy as well as the increased ease in which the medication can be obtained.26 Women receiving methadone need to attend a methadone clinic daily to obtain the medication in person, whereas women receiving buprenorphine can receive a prescription to pick up multiple doses of the medication at their local pharmacy.

National, state, and regional organizations are aware of the impact that the opioid epidemic has had on pregnant women and several clinical guidelines and resources have been published (Appendix 1).6,27 The Council for Patient Safety in Women’s Health Care’s Alliance for Innovations on Maternal Health has recently published a safety bundle focused on maternity care for women with opioid use disorder.28 The common theme in these guidelines is the recognition that the use of medically supervised opioid replacement therapy or pharmacotherapy with methadone, buprenorphine or buprenorphine/naloxone should be integrated into supportive prenatal care models that address OUD and psychosocial needs.

In this article, a clinical case that highlights some of the key issues that midwives and other providers need to be aware of during the antepartum, intrapartum, and postpartum care of pregnant women with OUD is described. Literature on screening and counseling for opioid use disorder, a multidisciplinary approach to prenatal care, maternal legal considerations, and unique aspects of care during labor, birth and postpartum are discussed.

ANTEPARTUM CASE PRESENTATION

B.L. is a 28-year-old G3P1011 presenting for a new prenatal visit at 22 weeks gestation by last menstrual period. She reported that she did not enter care earlier in the pregnancy because she was busy. Her medical history was significant for a motor vehicle accident six years ago resulting in chronic back pain. She reported taking prenatal vitamins as her only daily medication. Routine laboratory tests and ultrasound for dating and anatomical survey were ordered. As part of her routine first prenatal visit, the midwife utilized the Screening, Brief Intervention and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT)29 framework to assess B.L.’s drug use history. First, the midwife used the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) Quick Screen to screen for substance use (Table 2).30 B.L. answered “yes” to a history of use of an illegal substance, so the midwife had B.L. subsequently complete the NIDA-Modified ASSIST,30 which assesses lifetime illicit and non-medical use of prescription drugs and determines a risk level. Based on B. L.’s response, the midwife determined that B.L.’s opioid use was high risk for potentially causing harm to herself and/or the fetus.30 Through motivational interviewing31, the midwife engaged in a discussion with B.L. about her opioid use, history, and current needs. B.L. shared that she was prescribed hydrocodone/acetaminophen (Norco) after her motor vehicle accident, which failed to control her pain after one year. After referral to a pain clinic, B.L. switched to oxycodone (OxyContin), increasingly required higher doses, and began to purchase oxycodone illegally. She eventually began smoking heroin daily due to the high cost of oxycodone.

Table 2.

Screening and Brief Intervention for Prenatal Substance Use Using the NIDA Screening Tool30

| Step | Screening Tool | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | NIDA Quick Screen | Ask patients about past year drug use using the NIDA Quick Screen. |

| Step 2 | NIDA-Modified ASSIST | Ask the patient about lifetime drug use using the NIDA-Modified Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST) |

| Step 3 | NIDA Risk Level and | Determine risk level based on score: 0–3 Low Risk 4–26 Moderate Risk ≥27 High Risk |

| Step 4 | Brief Intervention |

Low Risk Provide feedback Reinforce abstinence Offer continuing support |

|

Moderate Risk Provide feedback Advise, Assess and Assist Consider referral based on clinical judgement Offer continuing support |

||

|

High Risk Provide feedback on the screening results Advise, Assess and Assist Arrange referral Offer continuing support |

Adapted from: National Institute on Drug Abuse. Resource Guide: Screening for Drug Use in General Medical Settings. Rockville, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2009.30

Given her history, the midwife established a diagnosis of OUD. When B.L. conceived her first child, she returned to the pain clinic and was started on buprenorphine/ naloxone pharmacotherapy for OUD throughout her pregnancy. During that pregnancy, she felt judged by her maternity care providers and received little guidance about what to expect for herself or her infant in light of her OUD. This experience resulted in her delayed prenatal care initiation during her second pregnancy. B.L.’s goal in this pregnancy was to do the “safest thing for me and my baby.”

The midwife acknowledged B.L.’s bravery in disclosing her history, saying, “I understand it was difficult for you tell me about your past history. I applaud you for your courage and I will do everything I can to support your recovery process and to help you meet your goal.” The midwife then referred B.L. to a specialty prenatal addiction medicine clinic within her university system that cares for pregnant women with OUD. The prenatal plan of care at this clinic included buprenorphine/naloxone medication management, depression and anxiety screening, social needs assessment, a plan for intrapartum and postpartum pain management, breastfeeding and neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) education, a plan for contraception, and a plan for close postpartum follow-up to prevent relapse.

ANTEPARTUM MANAGEMENT

Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT)

Both the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) 6 and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) 32 recommend universal screening and assessment of all pregnant women for substance use including opioids using Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral for Treatment(SBIRT)29 at the first prenatal visit and periodically throughout pregnancy. SBIRT is a comprehensive evidence-based public health approach to substance use for individuals at risk of developing a substance abuse disorder.29,32 Screening, the first step of SBIRT, is the process by which a healthcare professional utilizes a standardized tool to identify patients at risk for substance abuse. Brief intervention is the process by which a healthcare professional engages an individual in a short conversation about their substance use utilizing motivational interviewing techniques31 and providing feedback and advice. Referral to treatment is the process by which a healthcare provider refers an individual to specialized therapy or treatment.29,32 In September 2012, the CDC convened an expert panel to discuss the use of SBIRT in the perinatal period; the panel recommended universal substance abuse screening during pregnancy.33

Screening

l. Substance abuse affects women across all socioeconomic, racial and ethnic groups as well as geographic areas.6 Providing universal screening for all pregnant women avoids perpetuating unsubstantiated stereotypes about the race, class, or physical appearance of women with substance use. Pregnancy-validated screening tools include the NIDA Quick Screen30 (Table 2), the 4P’s34 (Appendix 2), or CRAFFT35 (Appendix 2).

The United States Preventive Services Task Force has not yet found sufficient evidence to support universal screening for illicit drug use during pregnancy; however, the organization is in the process of conducting a systematic review of the most currently available evidence and will update guidelines when this analysis is complete.36 The American College of Nurse-Midwives Position Statement on Addiction in Pregnancy37 includes a recommendation for compassionate, comprehensive, and holistic care, but does not currently include recommendations for universal screening. Of note, in this case study, had the midwife not employed universal screening, B.L. might not have voluntarily disclosed her opioid use due to her history of feeling stigmatized during her first pregnancy.

Brief Intervention

Brief Intervention refers to the process by which a healthcare professional engages an individual with drug use in a short conversation, providing feedback and advice. A Brief Intervention typically lasts 5–10 minutes and can be repeated multiple times during follow-up visits. After screening, women identified as having no history of opioid use prior to pregnancy or low-level use with immediate cessation during pregnancy can be considered low risk for OUD.33 These women should receive brief advice and reinforcement about the importance of abstinence. A summary of interventions based on screening-identified risk level is described in Table 2.

Women identified with high risk use of any substance in the past, including recent treatment, cessation late in pregnancy, or continued low level use are considered to be at moderate risk.33 For these women, frequent follow-up visits and brief intervention using motivational interviewing techniques may enhance desire for change.33 During this process, midwives and their staff should be aware that conversations should be non-judgmental and supportive, as this is a key opportunity to establish trust and rapport. For women like B.L. who are identified as being high risk through a universal screening process, the first step of brief intervention is to raise awareness. In B.L.’s case, the midwife offered: 1) Feedback and encouragement about her disclosure; 2) Enhanced motivation: “I encourage you to continue to take your buprenorphine/naloxone since this has worked so well for you. There are some special considerations for pregnant women taking this medication and the most important thing for you and your baby is your continued recovery;” and 3) Negotiation about a plan: “How I can help support you in your pregnancy and your recovery process? May I refer you to my OB colleague who can continue your medication?”33

Motivational interviewing31 is an important skill in the SBIRT process. The goal of motivational interviewing is to elicit self-motivational statements and behavioral change by expressing empathy, using reflective listening, helping the client identify the discrepancy between their goals/values and current behaviors, avoiding argument and confrontation by adjusting to resistance rather than directly opposing it, and supporting self-efficacy and optimism.38 Becoming skilled at motivational interviewing takes time, and midwives can benefit from in-person training, which allows for immediate feedback or using online resources such as The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMSHA) document, “Tip 35, Enhancing Motivation for Change in Substance Abuse Treatment.”38

Referral to Treatment

Referral to treatment is required for women like B.L. with high-risk opioid use, as they may need more intensive management than brief intervention alone. Available information suggests that among pregnant women, receipt of multidisciplinary services that integrate maternity and addiction care in one setting may result in improved retention in prenatal care,39–41 increased gestational length and birth weight,40 reduction in intravenous injection risk behaviors (needle-sharing),42 and fewer drug positive urine screens.43 In a study of 49,985 women screened for substance abuse in the Kaiser Permanente system, those who screened positive and received integrated substance abuse treatment and prenatal care were less likely to have a low birthweight infant (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 1.8; 95% CI, 1.1–3.1), preterm birth (aOR, 2.1; 95% CI, 1.3–3.2), or an intrauterine fetal demise (aOR, 16.2; 95% CI, 6.0–43.8), compared to those who screened positive based on a urine toxicology screen, but did not receive care through such a program.32

Models of care for women with OUD incorporating pharmacotherapy, prenatal care, assessment and treatment of mental health needs, and addressing needs based on social determinants of health such as food insecurity, intimate partner violence, transportation, and childcare are well described.44 Finnegan initially proposed the biopsychosocial model for pregnant women with substance use disorders that integrates prenatal care with social and psychological services.45 If available, it is ideal to refer women with OUD to a specialty clinic that co-locates prenatal care with addiction care. An example of this type of clinic could include a maternity care provider (eg, midwife, obstetrician, and /or maternal fetal medicine specialist), a provider with a buprenorphine waiver, addiction medicine and mental health providers, ultrasound services, social workers, case management, naloxone (Narcan) kits, and peer support.

Midwives can serve as key members of the team that cares for these women. For example Sutter et al described a new group prenatal care model for women with OUD that is co-located in a prenatal pharmacotherapy program.46 This inter-professional model includes midwives, physicians, nurses and mental health care providers. In a study of this model of care, participants provided feedback about their experiences after giving birth. The feedback included an increased feeling of trust between themselves and their providers, an increased motivation to remain sober during the pregnancy, and a social connectedness with other women that endured after birth.46 Goodman et al has described the multidisciplinary approach of co-locating midwifery care with addiction and psychiatric services to improve care of pregnant women with opioid use disorder at Dartmouth University.47 In the absence of a multidisciplinary clinic, midwifery co-management incorporating referrals for pharmacotherapy, as well psychiatry, social work, and case management may be needed to address the complex needs of the woman. In addition, discussion of intrapartum and postpartum pain management options during the prenatal period will help to prepare women and consultation with an anesthesiologist prior to labor may help ensure appropriate pain management during this critical window.

Buprenorphine Waiver

In order to prescribe or dispense buprenorphine, qualified providers including physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants and most recently, certified nurse-midwives, must complete required training and complete the Waiver Completion Form from SAMHSA. The waiver is then forwarded to the Drug Enforcement Agency that assigns the provider a special designation number which must be included on each buprenorphine prescription. Details about obtaining a buprenorphine waiver are available on the SAMHSA web site.

In October 2018, Congress passed H.R. 6: Substance Use Disorder Prevention that Promotes Opioid Recovery and Treatment (SUPPORT) for Patients and Communities Act. This Act builds on the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act, which was passed in July 2016, and expands prescriptive authority of buprenorphine to midwives and other advance practice registered nurses for a 5-year period and permanently authorizes the SAMHSA program for nurse practitioners and physician assistants. Because of the physiology of pregnancy including increased metabolism and volume of distribution, buprenorphine doses often are adjusted throughout pregnancy. Most women will require dosage increases due to increased withdrawal or craving symptoms.48 Split dosing, twice daily, three times daily or even four times daily, is often needed.49

CLINICAL CARE DURING PREGNANCY FOR WOMEN WITH OPIOID USE DISORDER

Modifications to prenatal care are necessary for women with OUD. These women may require screening for HIV, hepatitis C, hepatitis B, syphilis, gonorrhea, chlamydia, and tuberculosis as well as repeating screening for women who are at high risk of interval new infection (e.g. women actively using drugs, those with partners who have known infections or who are actively using substances, etc.).29 Midwives should be aware that standard tests for HIV and hepatitis C antibody screening may miss recent infection, During the “window period,” the time after infection but before the body has developed antibodies, some women can have a false negative HIV and/or hepatitis C test.50 Thus polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing among those at highest risk of recent transmission may be the test of choice. Women who are hepatitis B surface antibody negative and at high risk of hepatitis B infection should be vaccinated during pregnancy. Given the risk for intrauterine growth restriction, an early ultrasound for dating confirmation and a mid-trimester anatomy ultrasound are recommended, as well as interval growth ultrasounds as indicated.29

Women who struggle with opioid use, misuse or OUD often have complex social and psychiatric stressors in their lives. One-third of pregnant women with OUD have a psychiatric comorbidity, most commonly depression and/or anxiety.51 It is recommended that clinicians routinely screen for mental health disorders among women with OUD and have a referral network in place for those who need specialized mental health care. A majority of women enrolled in opioid pharmacotherapy programs also report smoking (88%−95%).52 If smoking cessation is not addressed in their opioid treatment program, smoking cessation techniques including nicotine replacement therapy or bupropion can be discussed during prenatal care in order to improve pregnancy outcomes and maternal health.

One example of a comprehensive prenatal checklist to ensure that the complex needs of women with OUD during pregnancy are met has been developed by the Northern New England Perinatal Quality Improvement Network.53 The checklist includes items such as specific laboratory tests, mental health referrals, social services referrals, and smoking cessation referrals and a toolkit for providers. Goodman et al conducted a pilot study to determine if the checklist was implemented and if so, whether there were any effects on perinatal outcomes.53 The authors compared outcomes in a similar cohort of women with OUD cared for before the checklist was implemented and after the checklist was implemented (n =223). Across the 8 sites where the checklist was implemented, the number of women with access to naloxone increased (10.9% to 36.3%, P < .001); more women received information about the benefits of breastfeeding (50.9% vs. 72%, P < .01); and utilization of nicotine replacement therapy increased (9.1% vs. 26.8%, P = .01). There were no significant difference in the rates of prematurity, low birth weight or breastfeeding at the time of hospital discharge, however; this study utilized a pre- and post-design and may not have been powered to detect significant differences in these outcomes.53

Antepartum Urine Drug Screening

Urine drug screening is commonly used once prenatal care providers are aware of a woman’s drug use. Urine screening may be a useful tool during prenatal care for substance use treatment monitoring and around the time of birth when knowledge of substance use may inform management decisions intrapartum or for the newborn. It is up to the prenatal provider and/or addiction medicine provider to determine how frequently urine drug screening is used. Often, urine drug screens are collected at each prenatal visit. Urine drug screening should always be done with a woman’s knowledge and consent.33

While a number of substances including urine, blood, hair, saliva, sweat, and toenails/fingernails can all be used for laboratory drug testing, urine is most commonly used because it is easy to collect. Urinalysis screening for opioid use detects drug metabolites. Drug and metabolite concentrations are higher in urine compared to serum, allowing for longer detection times.54 Immunoassays are the most common method for initial drug screening; these utilize antibodies to identify the presence of specific drugs or metabolites. Immunoassays provide rapid results but may yield false-positive results. Therefore, positive urine immunoassays results are considered presumptive until confirmatory testing is done.54 Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry is most frequently used for confirmatory testing and is the most accurate and reliable method of testing, however it can be costly and time-consuming. Thus, it is only done after a positive result from an immunoassay.54

The sensitivity, specificity, false positive, and false negative rates for urine opiate immunoassay screening varies considerably across various opioid drugs.55 The traditional opiate immunoassay can detect morphine and codeine, however, opioids such as methadone, oxycodone, and tramadol (Ultram) may go undetected due to their more synthetic nature.56 While screening tests are available for specific compounds, they typically can detect only one or 2 compounds at one time.56 Opioids may be present in urine for up to 4 days after use, although the exact time depends upon the type of opioid being used.54 False negative screening results can occur if too much time has passed between opioid use and testing or when metabolites are not present in sufficient quantity to be detectible.54 A number of substances have also been associated with false positive immunoassay results for opioid use including ingestion of poppy seeds,57,58 as well as use of dextromethorphan, diphenhydramine, quinine, quinolones, levofloxacin (Levaquin), ofloxacin (Ocuflox) rifampin (Rifadin), and verapamil (Calan).54,59 A 2017 study that compared meconium drug screening to maternal urine drug screening to detect opioid exposure among mother-infant dyads at birth found that maternal urine drug screen had a higher sensitivity (0.52, 95% CI 0.39–0.65) and specificity (0.88; 95% CI, 0.79–0.97) for the detection of intrauterine opiate exposure compared to meconium drug screening.60 It is important to note that routine urine drug screening is controversial as it does not reflect severity of disease.6 Most importantly, women should be informed of the legal ramifications of positive results including mandatory reporting requirements.61–63

Education and Preparation for Neonatal Opioid Withdrawal Syndrome

Prenatal education for women with OUD includes discussion about expectations of newborn care and the risk of neonatal opioid withdrawal syndrome (NOWS). Approximately 30% to 50% of newborns exposed to opioids in utero will experience symptoms of NOWS.63 NOWS is a complex of behavioral and physiologic symptoms exhibited by newborns following prenatal exposure to opiates. Clinical signs and symptoms of NOWS include tachypnea, temperature instability, mottling, nasal congestion, diarrhea, vomiting, feeding problems, poor weight gain, skin breakdown, erratic sleep patterns, high-pitched cry, hypertonicity, irritability, tremors, and seizure activity. Newborns are typically monitored for signs of NOWS for 72 to96 hours after birth.64

Treatment for NOWS may include both non-pharmacologic and pharmacologic (opioid-replacement) interventions. Recent studies have suggested that the use of non-pharmacologic interventions may improve outcomes for infants with NOWS. Specifically, breastfeeding has been associated with a mean reduction in length of hospital stay of 3 to 7 days, and swaddling, low stimulation environment and rooming-in with the mother have been associated with a 3 to 17 day decrease in length of stay, 8 fewer days of opioid therapy, a 20% to 60% reduction in the need for medication, and a 3–8 day reduction in the total number of treatment days for NOWS infants.65 The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends starting adjuvant medications such as morphine for NOWS infants only if the non-pharmacologic methods fail.63 AAP recommends that institutions use a scoring tool to assess signs of withdrawal among infants. According to 2013 survey of 383 facilities, 95% of institutions were using the Finnegan Neonatal Abstinence Scoring System to guide treatment.66 Antenatal preparation can include visiting the newborn intensive care unit and meeting with a neonatologist in addition to education and counseling.

Breastfeeding Education

Breastfeeding is recommended for women using pharmacotherapy including methadone or buprenorphine.67 Contraindications to breastfeeding include active illicit drug use, HIV infection, and respiratory tuberculosis.68 Wachman, et al 2018 found that breastfeeding was associated with a decreased severity of NOWS, shorter newborn intensive care unit stays, and less pharmacotherapy for the infant;65 however, a retrospective chart review conducted in 2013 identified no statistically significant differences between the severity of NAS among babies who breastfed or did not breastfeed.65,69 Women should be counseled about the need to suspend breastfeeding and seek addiction care immediately if they relapse during the postpartum phase or while still breastfeeding.

Contraception Planning

Women with OUD are more likely to have an unintended pregnancy when compared to women without OUD.70 Ideally, plans for contraception including long-acting and reversible contraception options are reviewed during prenatal care. If a plan is not made prior to birth, a contraceptive plan can be made prior to discharge following birth. Providers are encouraged to elicit the woman’s goals for future pregnancy and pregnancy prevention. Failure to do so may reinforce an unintended message about women with OUD’s worthiness as mothers.

INTRAPARTUM AND POSTPARTUM CASE PRESENTATION

B.L. called the midwife on-call in early labor per the plan made during her prenatal care to ensure adequate pain management throughout her labor. The midwife on-call recommended that B.L. come to the triage unit and then called ahead to explain B.L.’s needs for an early epidural and, if needed, nitrous oxide for pain management until the epidural was effective. B.L. arrived at the triage unit and was found to be 2 centimeters dilated and contracting every 5–7 minutes with no leaking of fluid and normal fetal movement. Fetal heart tones were reassuring and she was coping well with her husband at her side. She requested nitrous oxide until her epidural was in place. B.L. was admitted to the labor floor and anesthesia was paged to place an epidural. Given B.L had an anesthesia consultation during her pregnancy, the anesthesiologist was aware of her case and pain management needs. Her epidural worked well to manage labor pain and she progressed to complete dilation 5 hours after arriving to the hospital. She pushed effectively for 30 minutes and gave birth to a healthy, male with an Apgar scores of 8 at one minute and 9 at five minutes. The pediatricians were present at the birth to evaluate the newborn immediately after birth. The newborn stayed with BL and roomed in during her postpartum stay. B.L. was aware that she and her newborn would stay in the hospital for at least 4 days after the birth because NOWS symptoms often do not present until 3–4 days postpartum.

Once she was transferred to a postpartum room, the nurses regularly evaluated the newborn for NOWS using Finnegan scoring system. Preventatively, non-pharmacologic interventions were implemented, including breastfeeding, swaddling, rooming-in and a low stimulation environment. B.L’s baby did not need pharmacologic intervention to manage withdrawal symptoms and was discharged home with B.L. on postpartum day 4.

B.L. had 2 postpartum visits at 2 and 6 weeks in the specialty prenatal addiction clinic where she received care during her pregnancy. Her infant was followed through the pediatric clinic in the same university system. B.L.’s dose of buprenorphine/naloxone was decreased at her 6 week postpartum visit and she scored low on the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Screen for postpartum depression at both her 2 and 6 week postpartum visits. She reported that she was thrilled with the care she and the newborn received. She planned to follow up after the postpartum period of 6 weeks with the pain clinic that originally prescribed her buprenorphine/naloxone. She was screened for depression and anxiety at each of her infant’s pediatric visits as well.

INTRAPARTUM AND POSTPARTUM MANAGEMENT

There are few studies available to guide intrapartum and postpartum pain management for women with OUD. ACOG recommends an early labor epidural and avoiding opioid agonist-antagonist drugs, such as nalbuphine (Nubain), because nalbuphine may precipitate withdrawal in women on opioid agonist treatment.6 Use of 50%−50% mixture of nitrous oxide and oxygen that is inhaled and self-administered, until adequate pain relief can be secured is an option if available. There are few published studies about the use of nitrous oxide for pain relief during labor among women with OUD. In a cohort study of 68 women (vaginal n=35; cesarean n= 33), there were no statistically significant differences in intrapartum pain or analgesia among women taking methadone versus women not taking methadone or another opioid agonist.71

Postpartum pain management requirements may vary depending upon whether the women experienced a vaginal birth or cesarean delivery. Meyer et al71 compared postpartum pain scores between women who use methadone versus a similar cohort of women who did not use methadone. The women taking methadone who had a vaginal birth experienced increased pain scores compared to women not using methadone (median [25th, 75th percentile] 2.7 [1.9,5.0] versus 1.4 [0.5,3.0] respectively, P=.001). There was no statistically significant increase in postpartum opioid use. In contrast, women who were taking methadone and had a cesarean birth experienced higher pain scores (median [25th, 75th percentile] 5.3 [4.1,6.0] versus 3.0 [2.2,3.9], P=.001), but required 70% more opioid analgesic than women in the control group (P=.001). A subsequent retrospective cohort study by the same authors, women who were using buprenorphine (n = 63) were compared to women not using buprenorphine with regard to postpartum pain and opioid use. The findings were similar to the previous study that assessed women on methadone with those using buprenorphine reporting higher pain scores and higher use of opioid to treat postpartum pain when compared to women not on opioid treatment therapy.72 Studies are on-going to assess patient and provider satisfaction with an opioid-free post cesarean protocol for women with OUD.

Postpartum Relapse

Mounting evidence suggests that the first year after birth is a critical time for women with OUD and the most likely time for opioid relapse, overdose, and death.73 Increased vulnerability during the postpartum period may be due to multiple factors including loss of health insurance, the new demands of parenting, sleep deprivation, the threat of loss of child custody, and the increased risk of postpartum depression and anxiety.74 Without access to care and the strong interdisciplinary support women may have received during pregnancy, and in the face of these additional life stressors, women with OUD are have a significantly increased risk for postpartum relapse.75 Given the high risk of relapse, close postpartum surveillance is crucial and interventions such as providing naloxone kits can help prevent death from overdose.76 Women with OUD benefit from an early postpartum visit at 2 weeks and again at 6 weeks for psychiatric screening, substance abuse screening and to discuss the transition to receipt of care with a long-term pharmacotherapy provider. Ideally women should continue to be screened for substance abuse throughout the first year postpartum, which can be challenging if women lose their insurance.

LEGAL IMPLICATIONS FOR HEALTH CARE PROVIDERS

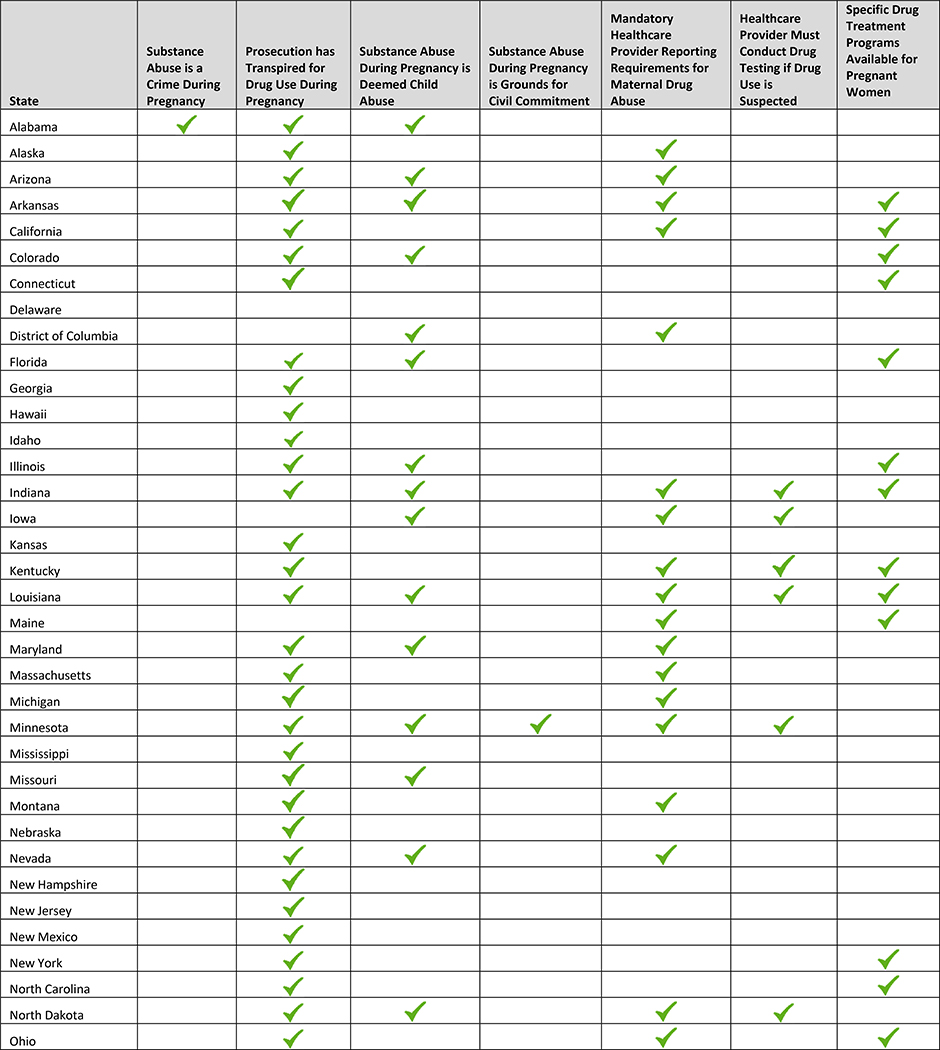

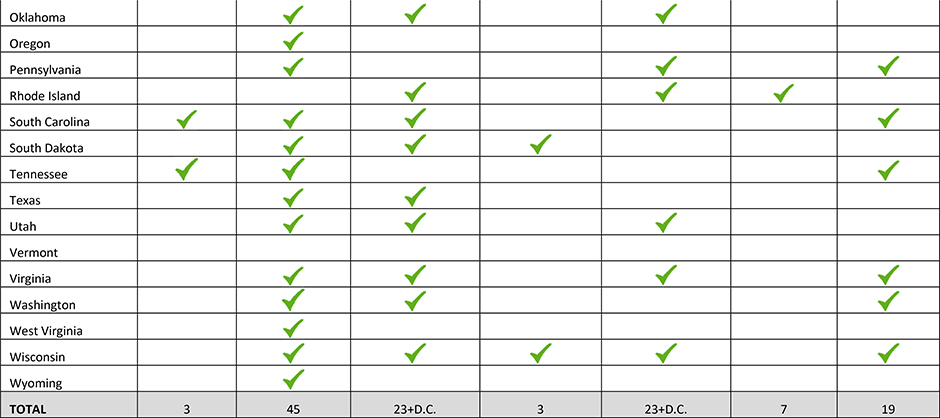

Local, state and federal laws requiring referral to child protective services are also germane to the care of this population As of 2017, 23 states and the District of Columbia require healthcare providers to report suspected maternal drug use; 23 states also consider drug use during pregnancy to be child abuse (Table 3).77,78 Since 1973, approximately 45 states have sought to take legal action against women for exposing their unborn fetus to drugs. Proponents of criminalization laws purport that threatened or actualized prosecution and incarceration will discourage maternal drug use; this has not been shown to be the case.77,78

Table 3:

State Laws Related to Perinatal Drug Use

|

|

Note. Adapted from “How States Handle Drug Use During Pregnancy,” by L. Miranda, V. Dixon, and C. Reyes, 2015, ProPublica Journalism in the Public Interest. Retrieved from https://projects.propublica.org/graphics/maternity-drug-policies-by-state; “State Policies on Substance Use during Pregnancy”, Guttmacher Institute, 2017, Retrieved from https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/substance-abuse-during-pregnancy.

Mandatory reporting requirements may pose a threat to the woman and provider relationship, and as such, have the potential to deter women from seeking prenatal care. Thus, for optimal care of pregnant women with opioid and substance use problems, it is imperative that providers understand the legal mandates in their state, including care for women who reside in other states. The Guttmacher Institute website provides a current summary of state policies related to substance use during pregnancy, including whether substance use is considered child abuse and when testing or reporting is required by law.77

Finally, it is vital that midwives have transparent discussions with pregnant women about legal mandates, hospital specific protocols for urine and cord toxicology screening, and reporting of drug-positive pregnant women and their newborns. For B.L., the midwife reviewed the policy for urine screening at time of buprenorphine/naloxone prescription and proceeded with her permission. Initially B.L. thought she would be immediately referred to child protective services because she was taking buprenorphine/naloxone, a common misperception. B.L was reassured that she did not meet criteria for referral in the state in which she resided and she was encouraged to disclose any relapses in order to best care for herself and her infant.

CONCLUSION

The current opioid epidemic requires all maternity providers to take an active role in prevention and treatment. The case of B.L illustrates many of the challenges women with OUD confront during pregnancy. She initially avoided care for fear of stigma against women with OUD. During her second pregnancy, she trusted that the recommendation by her prenatal provider to initiate pharmacotherapy was the best approach for the health of herself and her fetus/newborn. Collaborative, multidisciplinary care for women with OUD, whether in a specialty clinic or facilitated by a midwife, will promote optimal outcomes. Maternity care providers can also serve as advocates for policy change incorporating universal SBIRT into prenatal care and improving access to perinatal addiction care for all pregnant and postpartum women. At the heart of midwifery is the core principle that a trusting and open relationship is a critical component of the therapeutic relationship necessary to assure best outcomes for women.

Ideally, pregnant women with opioid misuse are referred to a specialty prenatal addiction programs; however, these are not widely available as only 19 states have drug treatment programs specifically targeted to pregnant women. The recent legislation which enables midwives to obtain a buprenorphine waiver can allow women with OUD that do not have an option to receive care at a specialty prenatal addiction clinic, to receive comprehensive care from their midwives. Providers who cannot refer women to these programs or do not have a buprenorphine waiver can still ensure comprehensive care through identifying local resources in the community to assist opioid-using women including pharmacotherapy treatment programs and resources to address the other psychosocial needs that often co-occur with opioid misuse. Per the ACNM Position Statement on Addiction in Pregnancy, midwives advocate for accessible care for all women and advocate against laws that punish pregnant women who seek treatment for drug and alcohol use disorders.37

Quick Points.

Opioid use during pregnancy is increasing and is associated with a range of adverse health effects for women and their newborns including neonatal abstinence syndrome, preterm birth, and a higher risk for maternal mortality and morbidity.

Midwives can care for pregnant women with drug use including opioids by learning to use the evidence-based framework SBIRT: Screening, Brief Intervention and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT).

Comprehensive care for pregnant women with opioid use disorder may be enhanced by co-management with midwives, addiction specialists, anesthesiologists, neonatologists and obstetricians.

Intrapartum care for women with opioid use disorder should include a pain management plan that addresses the specific goals and needs of the woman and also include a pain management plan for the postpartum period.

Laws regarding opioid use during pregnancy vary by state; midwives can familiarize themselves with reporting laws in their state and have transparent conversations with their patients about hospital protocols regarding drug testing and reporting.

Acknowledgments

Funding information: NIH grant WRHR K12, 1K12HD085816

Author Biographical Sketches

Abigail H. Rizk, CNM is in clinical practice with Birthcare Healthcare and a clinical instructor at the University of Utah College of Nursing.

Sara E. Simonsen, PhD, CNM, MSPH is an Associate Professor & Annette Poulson Cumming Presidential Endowed Chair in Women’s & Reproductive Health at the University of Utah College of Nursing.

Leissa Roberts, CNP, CNM, FACNM is a Clinical Professor and the Associate Dean for Faculty Practice at the University of Utah College of Nursing.

Lisa Taylor Swanson, PhD, MAcOM, EAMP is an Assistant Professor at the University of Utah College of Nursing.

Jennifer Berkowicz Lemoine, DNP APRN NNP-BC is an Assistant Professor at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette and a PhD student in the University of Utah College of Nursing.

Marcela Smid MD, MS, MA is an Assistant Professor in the Division of Maternal-Fetal Medicine in the University of Utah School of Medicine and Clinical Director of the Substance Use in Pregnancy Recovery Addiction Dependence Clinic.

Appendix

Appendix 1:

Resources for caring for pregnant women with OUD

| Resource | Description | Resource URL |

|---|---|---|

| ACOG | Opioid Use and Opioid Use Disorder in Pregnancy This Committee Opinion describes recommendations for opioid use and opioid use disorder screening and follow-up during pregnancy |

https://www.acog.org/Clinical-Guidance-and-Publications/Committee-Opinions/Committee-on-Obstetric-Practice/Opioid-Use-and-Opioid-Use-Disorder-in-Pregnancy |

| The Council for Patient Safety in Women’s Health Care’s Alliance for Innovations on Maternal Health | Obstetric Care for Women with Opioid Use Disorder This patient safety bundle focused on maternity care for women with opioid use disorder. |

https://safehealthcareforeverywoman.org/patient-safety-bundles/obstetric-care-for-women-with-opioid-use-disorder/ |

| NNEQPIN | A Toolkit For The Perinatal Care Of Women With Substance Abuse Disorders This toolkit is freely available and was designed to improve the safety and quality of care delivered to to pregnant women with opioid use disorders |

https://www.nnepqin.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/FULL-TOOLKIT-PDF_REV-05.21.18.pdf |

| SAMHSA | Clinical Guidance for Treating Pregnant and Parenting Women with Opioid Use Disorder and their Infants This clinical guide contains guidance about managing pregnant/parenting women with opioid use disorder as well as their infants. |

https://store.samhsa.gov/product/Clinical-Guidance-for-Treating-Pregnant-and-Parenting-Women-With-Opioid-Use-Disorder-and-Their-Infants/SMA18-5054 |

| SAMHSA | Healthy Pregnancy Healthy Baby Fact Sheets This is a series of fact sheets with information about the importance of continuing a treatment for opioid use disorder during pregnancy |

https://store.samhsa.gov/product/SMA18-5071 |

Abbreviations: ACOG, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; NNEPQIN, Northern New England Perinatal Quality Improvement Network; SAMHSA, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration

Appendix 2:

Clinical Screening Tools for Prenatal Substance Use and Abuse Screening

| Screening Tool | Description | Available from: | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRAFFT—Substance Abuse Screen for Adolescents and Young Adults35 |

C Have you ever ridden in a CAR driven by someone (including yourself) who was high or had been using alcohol or drugs? R Do you ever use alcohol or drugs to RELAX, feel better about yourself, or fit in? A Do you ever use alcohol or drugs while you are by yourself or ALONE? F Do you ever FORGET things you did while using alcohol or drugs? F Do your FAMILY or friends ever tell you that you should cut down on your drinking or drug use? T Have you ever gotten in TROUBLE while you were using alcohol or drugs? |

www.ceasar.org | Scoring: Two or more positive items indicate the need for further assessment. |

| NIDA Quick Screen30 | In the past year, how often have you used the following? • Alcohol, 4 or more drinks a day • Tobacco Products • Prescription Drugs for Non-Medical Reasons • Illegal Drugs |

https://www.drugabuse.gov/sites/default/files/files/QuickScreen_Updated_2013%281%29.pdf | Scoring: If the patient indicates any use of illegal drugs or prescription drugs for non-medical reasons, proceed to the NIDA-Modified ASSIST. 30 |

| Never, Once or Twice, Monthly, Weekly, Daily or Almost Daily | (If patient says yes to one or more days of heavy drinking or any current tobacco use, you should follow-up as well) | ||

| 4 Ps34 |

Parents: Did any of your parents have a problem with alcohol or other drug use? Partner: Does your partner have a problem with alcohol or drug use? Past: In the past, have you had difficulties in your life because of alcohol or other drugs, including prescription medications? Present: In the past month have you drunk any alcohol or used other drugs? |

Freely available and published in Committee on Obstetric Practice. Committee Opinion No. 711: Opioid Use and Opioid Use Disorder in Pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(2):488–489.6 | Scoring: Any “yes” should be used to trigger further discussion. |

Sources:

Dhalla S, Zumbo BD, Poole G. A review of the psychometric properties of the CRAFFT instrument: 1999–2010. Curr Drug Abuse Rev. 2011;4(1):57–64. 35

National Institute on Drug Abuse. Resource Guide: Screening for Drug Use in General Medical Settings. Rockville, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2009.30

Ewing H Medical Director, Born Free Project, Contra Costa County, 111 Allen Street, Martinez, CA. Phone: 510-646-1165.34

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosure: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Opioid Basics: Understanding the Epidemic. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website; https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/epidemic/index.html Updated December 19, 2018 Accessed May 9, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schuckit MA. Treatment of opioid-use disorders. N Engl J Med. 2016;28;375(4):357–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Misuse of Prescription Drugs. National Institute of Drug Abuse Publications website; https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/research-reports/misuse-prescription-drugs/summary Updated December, 2018. Accessed May 9, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Volkow ND. America’s addiction to opioids: heroin and prescription drug abuse. National Institute of Drug Abuse Testimony to Congress website; https://www.drugabuse.gov/about-nida/legislative-activities/testimony-to-congress/2014/americas-addiction-to-opioids-heroin-prescription-drug-abuse Updated May, 2014. Accessed May 9, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 5.U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General. Facing Addiction in America: The Surgeon General’s Report on Alcohol, Drugs, and Health. Washington (DC): US Department of Health and Human Services; 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Committee on Obstetric Practice. Committee Opinion No. 711: Opioid Use and Opioid Use Disorder in Pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(2):488–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Public Policy Statement: Short Definition of Addiction. American Society of Addiction Medicine website; https://www.asam.org/docs/default-source/public-policy-statements/1definition_of_addiction_short_4-11 Updated April 12, 2011. Accessed May 9, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ailes EC, Dawson AL, Lind JN, et al. Opioid Prescription Claims Among Women of Reproductive Age — United States, 2008–2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;23;64(2):37–41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nahin RL. Estimates of pain prevalence and severity in adults: United States, 2012. J Pain 2015;16:769–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prescription Painkiller Overdoses. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website; https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/prescriptionpainkilleroverdoses/index.html Updated September 4, 2018. Accessed May 9, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hernandez-Avila CA, Rounsaville BJ, Kranzler HRJD. Opioid-, cannabis-and alcohol-dependent women show more rapid progression to substance abuse treatment. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;74:265–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greenfield SF, Brooks AJ, Gordon SM, et al. Substance abuse treatment entry, retention, and outcome in women: a review of the literature. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;86:1–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital signs: overdoses of prescription opioid pain relievers and other drugs among women—United States, 1999–2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62(26):537–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Broussard CS, Rasmussen SA, Reefhuis J, et al. Maternal treatment with opioid analgesics and risk for birth defects. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204:314 e1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lind JN, Interrante JD, Ailes EC, et al. Maternal Use of Opioids During Pregnancy and Congenital Malformations: A Systematic Review. Pediatrics. 2017;139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haight SC. Opioid Use Disorder Documented at Delivery Hospitalization—United States, 1999–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018;67(31):845–849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patrick SW, Davis MM, Lehmann CU, Cooper WO. Increasing incidence and geographic distribution of neonatal abstinence syndrome: United States 2009 to 2012. J Perinatol. 2015;35(8):650–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yazdy MM, Desai RJ, Brogly SB. Prescription Opioids in Pregnancy and Birth Outcomes: A Review of the Literature. J Pediatr Genet. 2015;4:56–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dramatic Increases in Maternal Opioid Use and Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome. National Institute of Drug Abuse Publications website; https://www.drugabuse.gov/related-topics/trends-statistics/infographics/dramatic-increases-in-maternal-opioid-use-neonatal-abstinence-syndrome Updated January 2019. Accessed May 9, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sutter MB, Leeman L, Hsi A. Neonatal opioid withdrawal syndrome. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2014;41(2):317–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang MJ, Kuper SG, Sims B, et al. Opioid Detoxification in Pregnancy: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Perinatal Outcomes. Am J Perinatol. 2019;36(6):581–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Terplan M, Laird HJ, Hand DJ, et al. Opioid Detoxification During Pregnancy: A Systematic Review. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131:803–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martin CE, Longinaker N, Terplan M. Recent trends in treatment admissions for prescription opioid abuse during pregnancy. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2015;48:37–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roper V, Cox KJ. Opioid Use Disorder in Pregnancy. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2017;62(3):329–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goodman D Buprenorphine for the treatment of perinatal opioid dependence: pharmacology and implications for antepartum, intrapartum, and postpartum care. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2011;56(3):240–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Clinical Guidance for Treating Pregnant and Parenting Women With Opioid Use Disorder and Their Infants. Rockville, MD; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Obstetric Care for Women with Opioid Use Disorder Patient Safety Bundle. Council on Patient Safety in Women’s Health Care website; https://safehealthcareforeverywoman.org/patient-safety-bundles/obstetric-care-for-women-with-opioid-use-disorder/ Updated August, 2017. Accessed May 9, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shogren MD, Harsell C, Heitkamp T. Screening Women for At-Risk Alcohol Use: An Introduction to Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) in Women’s Health. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2017;62(6):746–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.National Institute on Drug Abuse. Resource Guide: Screening for Drug Use in General Medical Settings. Rockville, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miller WRRS. Motivational Interviewing: helping people change (3rd ed). New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 32.SBIRT: Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment. SAMHSA-HRSA Center for Integrated Health Solutions website; https://www.integration.samhsa.gov/clinical-practice/sbirt Updated April, 2011. Accessed May 9, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wright TE, Terplan M, Ondersma SJ, et al. The role of screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment in the perinatal period. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(5):539–547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ewing H Medical Director, Born Free Project, Contra Costa County, 111 Allen Street, Martinez, CA: Phone: 510–646-1165. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dhalla S, Zumbo BD, Poole G. A review of the psychometric properties of the CRAFFT instrument: 1999–2010. Curr Drug Abuse Rev. 2011;4(1):57–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Final Research Plan: Drug Use in Adolescents and Adults, Including Pregnant Women: Screening. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force website; https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/final-research-plan/drug-use-in-adolescents-and-adults-including-pregnant-women-screening Updated October, 2016. Accessed May 9, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 37.American College of Nurse-Midwives. Position Statement: Addiction in Pregnancy. Silver Spring, MD: American College of Nurse-Midwives, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. Enhancing motivation for change in substance abuse treatment. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Goler NC, Armstrong MA, Taillac CJ, Osejo VM. Substance abuse treatment linked with prenatal visits improves perinatal outcomes: a new standard. J Perinatol. 2008;28(9):597–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Carroll KM, Chang G, Behr H, Clinton B, Kosten TR. Improving treatment outcome in pregnant, methadone-maintained women: results from a randomized clinical trial. Am J Addict. 1995; 4(1):56–59. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sutter MB, Gopman S, Leeman L. Patient-centered Care to Address Barriers for Pregnant Women with Opioid Dependence. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2017;44(1):95–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.O’Neill K, Baker A, Cooke M, Collins E, Heather N, Wodak1 A. Evaluation of a cognitive-behavioural intervention for pregnant injecting drug users at risk of HIV infection. Addiction. 1996;91(8):1115–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chang G, Carroll KM, Behr HM, Kosten TR. Improving treatment outcome in pregnant opiate-dependent women. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1992;9(4):327–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Johnson E Models of Care for Opioid Dependent Pregnant Women. [published online Jan 14, 2019]. Semin Perinatol. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2019.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Finnegan LP. Perinatal substance abuse: comments and perspectives. Semin Perinatol. 1991;15(4):331–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sutter MB, Watson H, Bauers A, et al. Group Prenatal Care for Women Receiving Medication-Assisted Treatment for Opioid Use Disorder in Pregnancy: An Interprofessional Approach. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2019;64(2):217–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Goodman D Improving access to maternity care for women with opioid use disorders: colocation of midwifery services at an addiction treatment program. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2015;60(6):706–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mozurkewich EL, Rayburn WF. Buprenorphine and methadone for opioid addiction during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2014;41(2):241–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Welle-Strand GK, Skurtveit S, Jones HE, et al. Neonatal outcomes following in utero exposure to methadone or buprenorphine: a National Cohort Study of opioid-agonist treatment of Pregnant Women in Norway from 1996 to 2009. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;127(1–3):200–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hughes BL, Page CM, Kuller JA. Hepatitis C in pregnancy: screening, treatment, and management. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217(5):B2–B12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Arnaudo CL, Andraka-Christou B, Allgood K. Psychiatric Co-Morbidities in Pregnant Women with Opioid Use Disorders: Prevalence, Impact, and Implications for Treatment. Curr Addict Rep. 2017;4(1):1–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chisolm MS, Fitzsimons H, Leoutsakos JM, et al. A comparison of cigarette smoking profiles in opioid-dependent pregnant patients receiving methadone or buprenorphine. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15(7):1297–304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Goodman D, Zagaria AB, Flanagan V, et al. Feasibility and Acceptability of a Checklist and Learning Collaborative to Promote Quality and Safety in the Perinatal Care of Women with Opioid Use Disorders. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2019;64(1):104–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Moeller KE, Lee KC, Kissack JC. Urine drug screening: practical guide for clinicians. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83(1):66–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Milone MC. Laboratory testing for prescription opioids. J Med Toxicol. 2012;8:408–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nelson ZJ, Stellpflug SJ, Engebretsen KM. What Can a Urine Drug Screening Immunoassay Really Tell Us? J Pharm Pract. 2016;29(5):516–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ozbunar E, Aydogdu M, Doger R, Bostanci HI, Koruyucu M, Akgur SA. Morphine Concentrations in Human Urine Following Poppy Seed Paste Consumption. Forensic Sci Int. 2019;295:121–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rohrig TP, Moore C. The determination of morphine in urine and oral fluid following ingestion of poppy seeds. J Anal Toxicol. 2003;27(7):449–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Saitman A, Park HD, Fitzgerald RL. False-positive interferences of common urine drug screen immunoassays: a review. J Anal Toxicol. 2014;38(7):387–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stabler M, Giacobbi P Jr., Chertok I, Long L, Cottrell L, Yossuck P. Comparison of Biological Screening and Diagnostic Indicators to Detect In Utero Opiate and Cocaine Exposure Among Mother-Infant Dyads. Ther Drug Monit. 2017;39(6):640–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women. AGOG Committee Opinion No. 473: substance abuse reporting and pregnancy: the role of the obstetrician-gynecologist. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:200–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 633: Alcohol abuse and other substance use disorders: ethical issues in obstetric and gynecologic practice. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:1529–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hudak ML, Tan RC, Committee on Drugs; Committee on Fetus and Newborn; American Academy of Pediatrics. Neonatal drug withdrawal. Pediatrics. 2012;129(2):e540–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Artigas V Management of neonatal abstinence syndrome in the newborn nursery. Nurs Womens Health. 2014;18(6):509–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wachman EM, Schiff DM, Silverstein M. Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome: Advances in Diagnosis and Treatment. JAMA. 2018;319:1362–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mehta A, Forbes KD, Kuppala VS. Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome Management From Prenatal Counseling to Postdischarge Follow-up Care: Results of a National Survey. Hosp Pediatr. 2013;3(4):317–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sachs HC. The transfer of drugs and therapeutics into human breast milk: an update on selected topics. Pediatrics. 2013;132(3):e796–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gartner LM, Morton J, Lawrence RA, et al. Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics. 2005;115:496–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.O’Connor AB, Collett A, Alto WA, O’Brien LM. Breastfeeding rates and the relationship between breastfeeding and neonatal abstinence syndrome in women maintained on buprenorphine during pregnancy. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2013;58(4):383–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Than LC, Honein MA, Watkins ML, Yoon PW, Daniel KL, Correa A. Intent to become pregnant as a predictor of exposures during pregnancy: is there a relation? J Reprod Med. 2005;50(6):389–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Meyer M, Wagner K, Benvenuto A, Plante D, Howard D. Intrapartum and postpartum analgesia for women maintained on methadone during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110:261–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Meyer M, Paranya G, Keefer Norris A, Howard D. Intrapartum and postpartum analgesia for women maintained on buprenorphine during pregnancy. Eur J Pain. 2010;14(9):939–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Schiff DM, Nielsen T, Terplan M, et al. Fatal and Nonfatal Overdose Among Pregnant and Postpartum Women in Massachusetts. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:466–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chapman SLC, Wu L-T. Postpartum substance use and depressive symptoms: a review. Women Health. 2013;53(5):479–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Irvine MA, Kuo M, Buxton J, et al. Modelling the combined impact of interventions in averting deaths during a synthetic-opioid overdose epidemic. Addiction. 2019; doi: 10.1111/add.14664 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gopman S Prenatal and postpartum care of women with substance use disorders. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2014;41(2):213–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.State Policies in Brief: Substance Abuse During Pregnancy. Guttmacher Institute website; https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/substance-use-during-pregnancy Updated May 1, 2019. Accessed May 9, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 78.How states handle drug use during pregnancy. ProPublica website; https://projects.propublica.org/graphics/maternity-drug-policies-by-state Updated September 30, 2015. Accessed May 9, 2019. [Google Scholar]