Abstract

Objective

This study explores the effect of Donald Trump's candidacy, and first year in office, on Asian‐American linked fate. We argue that the use of anti‐Asian and anti‐immigrant messaging during the 2016 election, and the enactment of discriminatory policies once elected, increased feelings of panethnic linked fate among Asian Americans.

Method

To test our hypotheses, we assess Asian Americans’ levels of linked fate before the 2016 election, immediately after the 2016 election, and one year after the 2016 election with several time‐series surveys.

Results

We find that Asian‐American linked fate is higher after the election and remains high one year later. Qualitative data collected through open‐ended survey responses suggest that the increase in panethnic linked fate can be at least partially attributed to Trump's discriminatory rhetoric.

Conclusion

The results have implications for Asian‐American political behavior, particularly mobilization, by invoking collective action through panethnic linked fate.

In the 2016 presidential election, Donald Trump used many anti‐immigration messages to mobilize supporters. From chants of “build the wall” heard at Trump rallies to threats of ending the DACA program, Trump clearly signaled to voters that he would not support the immigration policies of his predecessor Barack Obama. Though much of the rhetoric focused on Latinos, Asian Americans were specifically targeted several times, including when Trump mocked a Chinese accent and when he threatened to cut off immigration from the Philippines. Trump's anti‐immigrant and anti‐Asian rhetoric, coupled with the noted increase in acts of anti‐Asian discrimination,1 may have activated Asian Americans’ panethnic linked fate.

Such a finding would be significant for our understanding of American politics for several reasons. First, it would provide evidence that external political threats play a significant role in determining the salience of group cohesion for Asian Americans, an understudied population. Recent research demonstrates that underrepresented groups such as Latinos develop panethnic linked fate in response to perceptions of threat (see Vargas, Sanchez, and Valdez, 2017). However, little is known about whether Asian Americans respond similarly. The unique circumstances of Trump's candidacy and election allow us to test the role of political threat in activating Asian‐American panethnic linked fate. Second, Asian Americans are a heterogeneous group in terms of culture, language, and immigration history and, thus, generally have low levels of linked fate (Masuoka, 2006). This heterogeneity serves as a good test case to better understand the factors that have the potential to unify seemingly disparate groups.

In this article, we test whether Trump's election to the White House increased a sense of panethnic linked fate among Asian Americans and whether those feelings were sustained over time. To assess this relationship, we use unique, cross‐sectional, time‐series data that asked different samples of Asian Americans about their levels of linked fate a week before the 2016 election, a week after the 2016 election, and a year following the 2016 election. Our findings suggest an increased expression of panethnic linked fate among Asian Americans one week following the election, and that the increase is sustained one year into the Trump presidency. Additionally, our qualitative evidence suggests that the increase in panethnic linked fate can be at least partially attributed to Trump's discriminatory rhetoric.

Asian‐American Linked Fate

Linked fate is the concept that an individual's life chances are tied to the fate of his or her racial or ethnic group (Dawson, 1995). Individuals with high levels of linked fate may develop group consciousness, and thus make political decisions based on the relative status of their racial/ethnic group. The concept of linked fate was first introduced to better understand African Americans’ cohesiveness and uniformity in political behavior (see, e.g., Dawson, 1995; Simien, 2005; Gay, 2004). Dawson (1995) and Tate (1994) argue that blacks’ common sociohistorical legacy with racism in the United States combined with continuing perceptions of discrimination have increased their sense of a common racial bond. While present in other groups, racial linked fate tends to be highest among African Americans (Masuoka, 2006).

For the most part, Asian Americans do not share the same historical legacies in the United States as African Americans, or even with one another. As a racial group, Asian Americans are more diverse in terms of their national origin and immigration histories. As Junn and Masuoka (2008) point out, no one Asian nationality group is predominant in the United States and there is great diversity in the languages spoken within Asian‐American communities. Additionally, a large segment of the Asian‐American population was born outside of the United States or are children of immigrants (Wong et al., 2001). For these reasons, several studies that explore Asian‐American identity formation find that this group is less likely to develop a racial identity that might increase feelings of panethnic linked fate in the same manner as African Americans (Lien et al., 2004; Masuoka, 2006; Skulley and Haynes, n.d.). However, others, such as Wong et al. (2005) and Junn and Masuoka (2008), demonstrate that group consciousness is malleable and that under the right political context, particularly one in which racial identity is primed by politicians, Asian Americans’ latent panethnic linked fate may become activated.

Based on this research, there is good reason to suspect that external political threats may play a role in shaping feelings of panethnic linked fate among Asian Americans. Research demonstrates that hostile political actors can influence perceptions of interpersonal discrimination, which may lead to increased feelings of group cohesion. Almeida et al. (2016) find that Latinos in states where anti‐immigration legislation is passed are much more likely to perceive encountering ethnic discrimination and experience an increase in panethnic linked fate. Similarly, Schildkraut (2014) shows that whites who were in contexts with a growing number of racial minorities felt discriminated against, activating a sense of group identity. The same logic may apply to Asian Americans, who may feel that when politicians are hostile to their group, they face more societal threats and discrimination. This may prime a shared identity and activate a sense of panethnic linked fate, which may influence political behavior, as recent studies suggest. Phoenix and Arora (2018) found that fear expressed during the 2016 election had a strong mobilizing effect on Asian Americans, while Kuo, Malhotra, and Mo (2017) found that perceptions of social exclusion among Asian Americans lead to an aversion for the Republican Party.

There is also good reason to believe that Trump's election may have increased Asian Americans’ perceptions of and experiences with discrimination, thus increasing their levels of panethnic linked fate. Trump levied numerous attacks on Asian Americans during his campaign. These attacks continued during his presidency as he mocked accents2 and targeted visa programs frequently used by Asian immigrants.3 While the attacks often targeted one ethnic group, the combination of attacks presented a broader pattern of anti‐Asian sentiment, which may have unified Asian Americans. Moreover, while Asian Americans vary significantly in their nationality, they are often lumped together by others (Espiritu, 1992). As a result, an attack on any Asian‐American nationality may lead to spillover attacks on others.4 Wu (2009), for example, showed that negative rhetoric toward one Asian‐American nationality group often leads to an increase in hate crimes against Asian Americans of a different nationality. As a result, Asian Americans may feel concerned when any group within their panethnic identity is attacked.

Additionally, Trump's election into office may have signaled to Asian Americans that voters found his anti‐immigrant, anti‐Asian rhetoric appealing; moreover, his election into office meant he could deliver on his campaign promises. Phoenix and Arora (2018) found a significant relationship between linked fate and the expression of fear and anger among Asian Americans during the 2016 election. Moreover, Lu and Jones (2019) suggest that direct experience with discrimination is not necessary for linked fate to develop; a perception of discrimination may be enough. Given previous findings, we hypothesize that Trump's attacks on Asian Americans and immigrants, in combination with his election to the White House, may heighten perceptions of discrimination among Asian Americans and activate panethnic linked fate and that the effect will be sustained into Trump's presidency.

Methodology

To test our hypotheses, we conducted two surveys on Amazon's Mechanical Turk (MTurk). The first survey was collected from November 1, 2016 to November 14, 2016. Roughly two‐thirds of the respondents took the survey before Election Day (N = 102) and about one‐third of the respondents took the survey after Election Day (N = 55). Because the political context and economic conditions remained almost constant across this two‐week period and the most notable change was the election of Trump, we can gain some insight into how perceived threats like the outcome of the 2016 election may shape Asian‐American panethnic linked fate. Additionally, given that any effect of an election may be temporary, we also commissioned a second survey that was collected roughly one year later, from December 20 to December 27, 2017 (N = 310). In each survey, respondents were paid 50 cents to complete a survey that took on average nine minutes to complete. All respondents in both surveys identify as Asian American.

It is important to note that MTurk surveys use an opt‐in rather than a national random sample. Thus, our data set was not purposely sampled to be representative of the population. As a result, the analysis below should be taken with caution given our sampling strategy. However, though we did not sample a random portion of the Asian‐American population, our survey does have several advantages. First, it is the only survey we are aware of that asked Asian Americans about panethnic linked fate directly before and after the 2016 election. Second, though not a nationally representative sample, Table 1 demonstrates that our samples are comparable in many ways to the 2016 National Asian American Survey (NAAS) (a survey collected only before the 2016 election) and the U.S. Census. The only major divergences are that the MTurk sample has a higher proportion of respondents born in the United States. Given this information, we have confidence that the findings in our MTurk sample can be extrapolated, albeit with caution, to Asian Americans nationally.5

TABLE 1.

Comparison of Asian‐American Respondents’ Demographic Data Across Both MTurk Samples, the NAAS, and the General U.S. Population of Asian Americans

| November 2016 Survey | December 2017 Survey | 2016 NAAS | U.S. Population | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 33 | 31 | 52 | 36 |

| Native born | 70 | 12 | 41 | |

| Bachelor's degree | 73 | 60 | 60 | 51 |

| Female | 48 | 41 | 46 | 52 |

| Chinese | 24 | 24 | 24 | |

| Indian | 17 | 21 | 20 | |

| Filipino | 12 | 12 | 19 | |

| Korean | 14 | 12 | 9 | |

| Vietnamese | 7 | 14 | 9 | |

| Japanese | 9 | 10 | 7 |

This article is being made freely available through PubMed Central as part of the COVID-19 public health emergency response. It can be used for unrestricted research re-use and analysis in any form or by any means with acknowledgement of the original source, for the duration of the public health emergency.

Third, the biases presented by MTurk's sampling method are unlikely to change between the first and second surveys. Even if the point estimate for linked fate is unrepresentative, it is unlikely that the increase in linked fate from one time point to the next is a product of bias. Finally, Asian‐American respondent levels of panethnic linked fate in our pre‐Trump sample (65.68 respondents say that they have “some” or “a lot” of Asian‐American panethnic linked fate) is higher than that of the NAAS (52.79 respondents say that they have some or a lot of Asian‐American panethnic linked fate), which was taken two months before our survey. The higher starting position of our baseline group provides a more conservative test of our theory as ceiling effects provide less room for Asian Americans as a group to increase in their linked fate in our sample.

Our panethnic linked fate measure for this project is created using two questions. The first asked respondents: “Do you think that what happens generally to Asian Americans in this country will have something to do with what happens in your life?” Those who responded yes were given the question: “How much does what happens to Asian Americans affect you?” Respondents were then given three choices: 1 = “A little”; 2 = “Some”; and 3 = “A lot” with which to answer. We use a combination of these questions to create a four‐point scale that ranges from 1 = No Asian‐American linked fate to 4 = A lot of Asian‐American linked fate.

Our main independent variable of interest is the timing in which the respondent took the survey. As such, we break our two surveys into three distinct time points. The first includes all Asian‐American respondents who completed the first survey from November 1, 2016, to midnight Pacific Standard Time (PST) on November 8, 2016 (T1‐pre‐Trump group). The second group includes those who took that same survey but during the period of November 9 (T2–immediately after Trump's election) to November 14. The final group completed the second survey a little over a year after Trump's election—December 20–27, 2017 (T3). Our analysis compares Asian Americans in the pre‐Trump group to those who completed the survey a week after his election and again approximately a year after his election.

Since our survey sample was not nationally representative or randomly distributed across these time frames, we include several control variables to ensure that our results are not driven by imbalances in our analysis. In particular, we control for age, income, education, partisanship, and ideology. Unfortunately, our first survey does not include measures for discrimination, nativity, or nationality, so we are unable to control for these variables. It is important to note that the surveys used for this analysis were originally used in a separate experiment that explored how Asian‐American and white authors advocating for Black Lives Matter influence support for the movement; Asian Americans were placed in one of three treatment groups.6 To ensure that the treatments in these surveys are not influencing our results, we include controls for treatment in the models. This control is particularly important given that in each survey, the treatment was presented before asking about linked fate.

Results

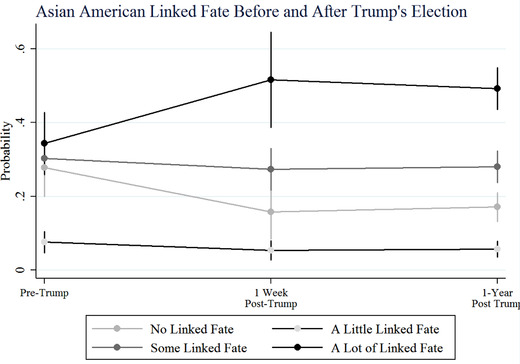

Table 2 7 presents ordered logit regression results predicting Asian‐American panethnic linked fate using time as the main independent variable of interest. Figure 1 presents corresponding marginal effects for Asian‐American linked fate derived from the model presented in Table 2. The results in Table 2 and Figure 1 demonstrate that even controlling for several factors, Asian Americans who were asked about their levels of linked fate a week after the 2016 election and Asian Americans who were asked about levels of linked fate a year after the election have significantly higher levels of panethnic linked fate than Asian Americans asked just one week before the election. Not only is this relationship significant, it is also substantial. Holding constant several variables, the predicted probability of expressing “a lot” of linked fate increases by over 10 percent between the week prior to Trump's election to the White House and one week after the 2016 election. In fact, after Trump's election the probability of Asian Americans identifying with “a lot” of linked fate is over 50 percent. This is true both one week and about one year after Trump's election.

TABLE 2.

Ordered Logit Regression Predicting Asian‐American Linked Fate Before and After Trump's Election

| Asian‐American Linked Fate | |

|---|---|

| (1–4) | |

| 1 week after 2016 election | 0.75** |

| (0.33) | |

| 1 year After 2016 election | 0.65*** |

| (0.23) | |

| Female | 0.28 |

| (0.19) | |

| Education | −0.01 |

| (0.07) | |

| Age | −0.00 |

| (0.01) | |

| Income | 0.00 |

| (0.00) | |

| Democrat | 0.39 |

| (0.24) | |

| Republican | −0.02 |

| (0.31) | |

| Ideology | 0.22* |

| (0.12) | |

| Treatment 1 | 0.17 |

| (0.23) | |

| Treatment 2 | 0.39* |

| (0.23) | |

| Cut 1 | 0.33 |

| (1.07) | |

| Cut 2 | 0.70 |

| (1.07) | |

| Cut 3 | 2.01* |

| (1.07) | |

| Observations | 434 |

note: *** p < 0.01; ** p < 0.05; * p < 0.1. Standard errors are in parentheses.

This article is being made freely available through PubMed Central as part of the COVID-19 public health emergency response. It can be used for unrestricted research re-use and analysis in any form or by any means with acknowledgement of the original source, for the duration of the public health emergency.

FIGURE 1.

Predicted Asian‐American Linked Fate (1 = None and 4 = A Lot) Before and After Trump's Election to the White House Based on Ordered Logit Regression

Qualitative Results

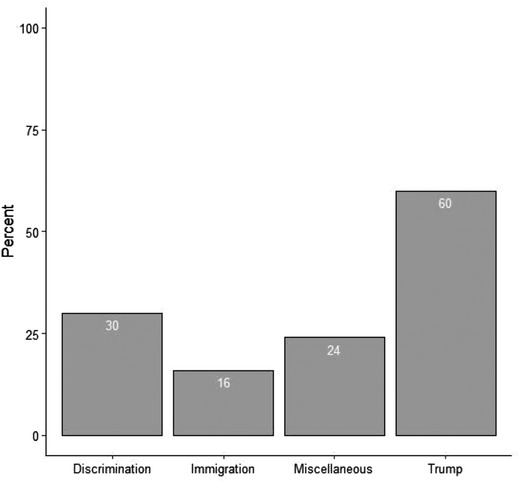

We asked respondents in the sample collected in December 2017: “Have you experienced a growing sense of connection to other Asian Americans following the 2016 Presidential Election?” For the 33 percent of respondents who answered yes, we asked the follow‐up question: “In two to three sentences, could you explain why you have experienced a growing sense of connection to other Asian Americans?" We then hand‐coded the responses into four categories; discrimination, immigration, Trump, and miscellaneous. Responses were categorized as discrimination if the explanation mentioned instances of discrimination. One respondent stated: “The climate [of] open racism being expressed by many angry white people has led me to feel the need to promote and seek promotion by other Asian American workers in my field…This isn't helped by all of the police shootings of black Americans and open hatred of brown and Muslim Americans, which makes me feel like, 'I could be next'.”

Similarly, responses were categorized as immigration if respondents mentioned immigration‐related issues. For example, one respondent said, “I worry about new immigration policies impacting my family or friends. I think about their lives and stories a lot more than I used to and how they are just as American.” If Trump was mentioned or clearly alluded to8 in a negative or threatening manner, then responses were coded into the Trump category. One respondent said, “I feel us Asians and other minorities have to stick together and be loyal to each other in light of the hatred perpetuated by this new President. I feel only us Asians can truly understand each other and what we go through.” If a respondent gave any other explanation that did not fall into the first three categories, then the responses were categorized as miscellaneous. For example, the following statement was categorized as both Trump and discrimination: “The really worst thing that Trump has accomplished is to unleash the simmering white antagonism towards (it seems) everyone that is not white. Sure, there has been a powerful and opposing white backlash but minorities are kind of giving up on whites for help.” Responses could be coded into multiple categories.

Figure 2 presents the percentage of responses in each of the four categories (discrimination, immigration, Trump, or miscellaneous). The results of our content coding of the open‐ended question suggest that growing fears about discrimination and Trump largely drive the growth in Asian‐American linked fate. Responses of discrimination (30.1 percent) and specific mentions of Trump (60.2 percent) are significantly more common than the miscellaneous category (24.3 percent) based on a two‐sample t‐test. Several comments show that the increase in linked fate is tied to fears about the general political environment rather than individual experiences with discrimination. Respondents mention “growing racism in the USA today,” “how discriminatory/prejudice(d) people are in this country,” and “simmering white antagonism towards (it seems) everyone that is not white.” Numerous comments emphasize the importance of Asian Americans coming together in the face of external threat.

FIGURE 2.

Content‐Coded Responses Answering a Question Why Asian Americans Experienced an Increase in Linked Fate After the 2016 Election

A comment made by one respondent is emblematic of the shifting environment created by the election of Trump: “Covert racists seem to be emboldened from the Trump presidency. As such, there is comfort in confiding in fellow Asian Americans who similarly feel threatened.” The content analysis provides additional support for our hypotheses that Trump's election heightened fear about discrimination, which in turn increased panethnic linked fate among Asian Americans.

Conclusion

Asian Americans are the fastest growing racial group in the United States (Hoeffel et al., 2012) and are increasingly becoming an important voting bloc in American politics. While this racial/ethnic group currently represents less than 6 percent of the total national population, geographic concentration in states like Hawaii, California, and New Jersey increase Asian‐American voting power. However, it remains an open question whether there is unification among Asian‐American voters. While Asian Americans tend to support the Democratic Party, as recently as the 1990s the community was viewed as a potential Republican voting bloc.

Our findings suggest that Asian Americans appear to feel a deeper connection to one another following the 2016 presidential election. Linked fate has long been shown to influence the political behavior of racial and ethnic minorities and increased feelings of linked fate may be one reason why Asian‐American Democratic support increased in 2016 even while Democratic support from other racial minority groups declined (Masuoka et al., 2018) and why Asian Americans became activated into politics (Lin, 2020). Our study suggests that Trump's hostile rhetoric may have increased Asian‐American linked fate. The results of this study have implications for American politics. Specifically, this study demonstrates that hostile politicians may play a large role in bringing marginalized groups together to build cross‐racial coalitions (Lu, 2020; Zheng, 2019). When Republicans use anti‐immigration policies to mobilize their base, they are in danger of alienating the fastest growing racial group.

While this study addresses an important topic, several important questions remain. First, our research design was conducted on a nonnationally representative sample of Asian Americans. While our own comparisons of our MTurk sample and the 2016 NAAS show statistical similarities in key demographics, future work may try to replicate this finding with a nationally representative data set. This would be particularly helpful in understanding the dynamics of linked fate among first‐generation Asian Americans, a population that was underrepresented in our samples. However, it is important to note that there is no national data set that we are aware of that asks about linked fate and is collected before and after the election of Trump in 2016. Our data set, though imperfect, is useful for understanding changes in Asian‐American linked fate given the impossibility of replicating the unique circumstances of the 2016 presidential election.

Second, future studies should assess whether other marginalized groups responded to the Trump candidacy as Asian Americans did. Additionally, future research should disaggregate which Asian‐American nationalities respond to group threats. AAPI political behavior is nuanced and the effects of political stimuli often vary by national origin group (Sadhwani, 2020). Our own cursory analysis asking respondents in the December 2017 wave of our survey whether they have experienced an increase in linked fate after the 2016 election demonstrates that South Asians are somewhat more likely than East Asians (p < 0.1) to have felt an increase in feelings of linked fate. Finally, future research should explore whether changes in Asian‐American linked fate after the 2016 election were driven by hostile rhetoric, fear of policy changes, or both. Our own analysis of the qualitative data suggests it is both. However, future work may find it useful to systematically test this possibility. While more work is necessary, this study provides an important contribution to our understanding of Asian‐American linked fate and the role of external political threats in shaping group identity.

Supporting information

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

See 〈https://www.latimes.com/opinion/story/2020-04-01/coronavirus-anti-asian-discrimination-threats〉.

We did not ask about national origin in the 2016 survey.

In our experiment, we created a letter that mimicked the website Letters for Black Lives. We ensured that respondents knew the topic of the letter through a headline that read “An Asian American's/White American's letter of support for the Black Lives Matter movement.” We also varied the race of the author from being Asian American to being white.

The results remain the same when we rescale linked fate on a one‐point scale and estimate an OLS regression. See the supplementary Appendix for these results, descriptive statistics, and an explanation of the data.

Examples of alluding to Trump include saying “when he was elected,” “his election,” or other similar phrases.

REFERENCES

- Almeida, J. , Biello K. B., Pedraza F., Wintner S., E. and Viruell‐Fuentes . 2016. “The Association Between Anti‐Immigrant Policies and Perceived Discrimination Among Latinos in the US: A Multilevel Analysis.” SSM—Population Health 2:897–903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson, M. C. 1995. Behind the Mule: Race and Class in African‐American Politics. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gay, C. 2004. “Putting Race in Context: Identifying the Environmental Determinants of Black Racial Attitudes.” American Political Science Review 547–62. [Google Scholar]

- Hoeffel, E. M. , Rastogi S., Kim M. O.; and Shahid H.. 2012. The Asian Population: 2010. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau; Available at 〈https://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-11.pdf〉. [Google Scholar]

- Junn, J. , and Masuoka N. 2008. “Asian American Identity: Shared Racial Status and Political Context.” Perspectives on Politics 6(4):729–40. [Google Scholar]

- Kuo, A. , Malhotra N., and C. H. Mo. 2017. “Social Exclusion and Political Identity: The Case of Asian American Partisanship.” Journal of Politics 79(1):17–32. [Google Scholar]

- Le Espiritu, Yen . 1992. Asian American Panethnicity: Bridging Institutions and Identities (Vol. 216). Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, M. 2020. “From Alienated to Activists: Expressions and Formation of Group Consciousness Among Asian American Young Adults.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46(7):1405–24. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, F. 2020. “Forging Ties: The Effect of Discrimination on Asian Americans’ Perceptions of Political Commonality with Latinos.” Politics, Groups, and Identities 8:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, F. , and B. Jones, 2019. “Effects of Belief Versus Experiential Discrimination on Race‐Based Linked Fate.” Politics, Groups, and Identities 7(3):615–24. [Google Scholar]

- Masuoka, N. 2006. “Together They Become One: Examining the Predictors of Panethnic Group Consciousness Among Asian Americans and Latinos.” Social Science Quarterly 87(5):993–1011. [Google Scholar]

- Masuoka, N. , Han H., Leung V., and Zheng B.. 2018. “Understanding the Asian American Vote in the 2016 Election.” Journal of Race, Ethnicity, and Politics 3(1):1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Phoenix, D. L. , and Arora M.. 2018. “From Emotion to Action Among Asian Americans: Assessing the Roles of Threat and Identity in the Age of Trump.” Politics, Groups, and Identities 6:357–72. [Google Scholar]

- Sadhwani, S. 2020. “Asian American Mobilization: The Effect of Candidates and Districts on Asian American Voting Behavior.” Political Behavior. Available at 〈 10.1007/s11109-020-09612-7〉. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schildkraut, D. 2014. “The White Establishment Is Now the Minority’: White Identity, Discrimination, and Linked Fate in the United States.” APSA 2014 Annual Meeting Paper. Available at 〈https://ssrn.com/abstract=2453577〉.

- Simien, E. M. 2005. “Race, Gender, and Linked Fate.” Journal of Black Studies 35(5):529–50. [Google Scholar]

- Tate, K. 1994. From Protest to Politics: The New Black Voters in American Elections. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Vargas, E. D. , Sanchez G. R., and Valdez J. A.. 2017. “Immigration Policies and Group Identity: How Immigrant Laws Affect Linked Fate Among US Latino Populations.” Journal of Race, Ethnicity and Politics 2(1):35–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong, J. S. , Lien P. T., and Conway M. M.. 2005. “Group‐Based Resources and Political Participation Among Asian Americans.” American Politics Research 33(4):545–76. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, J. S. , Ramakrishnan S. K., Lee T. , and Jane J.. 2001. Asian American Political Participation: Emerging Constituents and Their Political Identities. New York City: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Frank H. 2009. “Embracing Mistaken Identity: How the Vincent Chin Case Unified Asian Americans.” Asian American Policy Review 19:17. [Google Scholar]

- Yam, K. 2016. “Asian‐Americans Share Terrifying Stories of Racism After Election.” Huffington Post November 22.

- Zheng, B. Q. 2019. “The Patterns of Asian Americans’ Partisan Choice: Policy Preferences and Racial Consciousness.” Social Science Quarterly 100(5):1593–1608. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material