The purpose of this commentary is to highlight the importance of an intensive care unit (ICU) well‐being champion, who promotes self‐reflective practice and self‐care to protect staff well‐being. The well‐being champion provides peer‐to‐peer support, delivers psychological first aid and through the “Look, Listen and Link” approach, signposts staff towards professional assistance when needed. Our ICU nominated a well‐being champion from within the nursing team to take a bottom‐up approach to staff well‐being during the COVID‐19 crisis where the stress levels in ICU are notably high. 1

1. IMPACTS OF COVID‐19 ON WELL‐BEING IN ICU

The COVID‐19 pandemic has caused an excessive strain on global health care systems: ICU nursing staff have been at the front and centre of this crisis. During the pandemic, many ICUs extended beyond their walls and the ICU nursing workforce rapidly expanded with redeployed staff helping to meet the pandemic demands. In these extraordinary times staff faced divergence from established procedures. The patient to ICU nurse ratio increased alongside supervision of redeployed non‐ICU nurses and staff dealt with escalated end‐of‐life decisions attributable to a high ICU COVID‐19 mortality rate of 40% to 52%. 2

It is apparent that ICU nursing staff are exposed to high levels of stress prior to COVID‐19; additionally, evidence suggests, over 80% are at high risk of burnout, 3 compassion fatigue, and emotional exhaustion. 4 These risks could be even higher during the COVID‐19 pandemic, further challenging the ICU nurse's well‐being and resilience. 1 Furthermore, redeployed staff placed in unfamiliar work environments with minimal training cannot be expected to develop resilience in an unprecedented crisis. Following the first wave of the pandemic, redeployed staff have returned to their usual work environments, leaving some ICUs with increased bed capacity and a reduced workforce in preparation for a second COVID‐19 peak, causing anxiety among ICU nurses. 5 In addition, ICU nurses continued to spend prolonged periods in personal protective equipment (PPE) with the growing evidence of physical effects of extended time in PPE. 6 These unparalleled changes challenge the ICU nurses' well‐being.

Another factor affecting well‐being is increased exposure to moral distress among frontline ICU staff during COVID‐19. Moral distress can be defined as uncertainty, tension, constraint, conflict, and dilemmas experienced by health care workers in a crisis. 7 Nurses in ICU are often exposed to moral distress, which causes feelings of guilt, frustration, anger, and sense of injustice when their moral codes are compromised. 1 , 7 , 8 Furthermore, such moral distress could lead to long‐lasting mental distress including post‐traumatic stress disorder and depression. 1 Mentally distressed care staff will have limited capacity to support and offer compassionate care to patients. 4 It is evident that these well‐being risk factors are intensified for ICU nurses during the prolonged COVID‐19 pandemic; consequently, the ability to support, normalize psychological response and offer psychological first aid 9 can be challenged. Measures to address well‐being during COVID‐19 and into a future beyond COVID‐19 need to be identified and implemented.

2. THE WELL‐BEING CHAMPION ROLE

Nurses may be reluctant to speak openly with managers, 10 a well‐being champion provides approachable peer to peer support, encourages individual well‐being and signposts nurses towards professional help within the organization. Staff well‐being requires (a) an organizational “us,” (b) a team/unit “we” and (c) an individual “me” approach 4 for supportive workplace well‐being. In our ICU, a well‐being champion was identified from within the nursing team. They were supported by the nurse manager and a dedicated psychologist from the embedded psychology department and undertook psychological first aid training. Working alongside ICU nurses our well‐being champion shares the complex emotional state of uncertainty in a rapidly changing work environment allowing for empathetic support. Being in the “same shoes” as colleagues provides the opportunity to be curious, to ask open questions, to listen and to guide colleagues to draw their own conclusions (while carefully considering and observing dynamics among colleagues). Our well‐being champion's local unit knowledge and awareness of key staff concerns helped tailor support for colleagues. 3 Well‐being websites and Apps (both on tablets and computers) were highlighted to intensive care nurses strengthening vital peer support and camaraderie during these unprecedented times. The unit well‐being champion guided colleagues towards individual well‐being initiatives and a self‐reflective practice focusing on positive coping skills and mechanisms to amplify positive mindsets. Lastly, the well‐being champion provided the ICU nurses with a reflective diary to record their individual thoughts, feelings, and awareness during the staff recovery period after the core COVID‐19 phase. 11 This self‐reflective practice along with weekly email reminders encouraged ICU nurses towards self‐care to enhance their well‐being ownership.

3. SELF‐REFLECTIVE PRACTICE

Surviving and thriving in adversity is known as personal resilience, which involves the ability to bounce back after stressful events. 12 Resilient workers have increased awareness of their feelings such as anxiety, fear, and grief in challenging times. Staff well‐being and resilience are strongly related to each other. A systemic review of resilience interventions 12 identified that recognition and awareness of the positive thought process alongside reflective practice can enhance resilience.

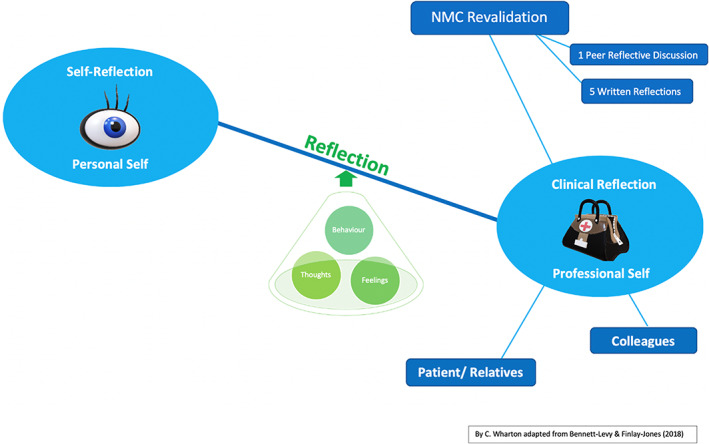

Reflective clinical practice is identified as an essential professional requirement by the Nursing and Midwifery Council. 13 Peer‐reflective discussion is useful to deepen shared learnings and practice improvement. Through professional reflective practice, nurses can revisit their lived feelings, thoughts, and behaviours (whether they are positive or negative) to convert these experiences to future resources, relating to their “professional self.” 13 The concept of personal practice, self‐refection of professional, and personal self, a core strategy used in psychology to develop therapist skills, interpersonal qualities, self‐awareness, and well‐being can be used for nurses. 14 As proposed in the Personal Practice Model for Nurses (Figure 1), a self‐reflective practice to identify one's own motivations, thoughts, feelings, and behaviours can enhance personal and professional growth. 14 Maintaining a good balance in the Personal Practice Model between professional reflection and personal reflection can help enrich well‐being and resilience. 14

FIGURE 1.

The personal practice model for nurses: Adapted with permission from Professor James Bennett‐Levy

Reflection encourages self‐care and compassion cultivating a positive mindset. The practice of mindfulness, which involves being fully present in the moment free from distraction or judgment, enhances reflection. Mindfulness can develop the ability to self‐sooth and reframe negative thoughts positively, improving compassion for self and others, which are essential for well‐being. 15 It is suggested self‐care is inadequately recognized by nurses 4 but nurses cannot care for others without caring for themselves. While critical care nurses are normally frequently highly resilient, 12 the majority were ill‐prepared for the prolonged working challenges of COVID‐19. To ensure staff well‐being during and after the COVID‐19 pandemic the Intensive Care Society and the British Psychological Society published recommendations for organizations, leaders, and managers. 9 , 11 The ICU well‐being champion customized the selection of well‐being resources and quick self‐care exercises by adapting to the evolving needs of ICU nurses. This can aid the passage through the disillusionment and exhaustion phase 9 while the personalized self‐reflective practice supported nurses in the recovery phase.

4. CONCLUSIONS

In the midst of this unparalleled global health crisis, the world witnessed the innovations, adaptability, and the vital contributions nurses make to the public health care system. In particular, the importance of supporting intensive care nurses' well‐being has been highlighted across various media platforms. When managed well, adversity can bring new knowledge, strength, and change, which are requisites for transformative personal growth. 12 Individual well‐being coupled with a robust workplace well‐being programme incorporating team/unit and organisational support systems can enhance quality patient care. A bottom‐up approach to well‐being practice is still in its infancy and requires further evaluation for effectiveness in the longer term. Innovative evidence‐based practice will shape ICUs into a future beyond COVID‐19. This commentary has sought to highlight the potential value of a well‐being champion in the delivery of peer‐to‐peer support guiding ICU nurses towards self‐reflection and well‐being ownership. We hope the points discussed here will assist other ICU's to utilize this process to protect their staff's well‐being, leading to an enriched patient care experience in any future crisis and beyond.

Wharton C, Kotera Y, Brennan S. A well‐being champion and the role of self‐reflective practice for ICU nurses during COVID‐19 and beyond. Nurs Crit Care. 2021;26:70–72. 10.1111/nicc.12563

REFERENCES

- 1. Williamson V, Murphy D, Greenberg N. COVID‐19 and experiences of moral injury in front‐line key workers (Editorial). Occup Med (Oxf). 2020;70(5):317–319. 10.1093/occmed/kqaa052 Accessed May 4, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Intensive Care National Audit and Research Centre . ICNARC report on COVID‐19 in Critical Care 7th September 2020. https://www.icnarc.org/Our-Audit/Audits/Cmp/Reports. Accessed September 21, 2020.

- 3. Vincent L, Brindley P, Highfield J, Innes R, Greig P, Suntharalingam G. Burnout Syndrome in UK Intensive Care Unit staff: data from all three Burnout Syndrome domains and across professional groups, genders and ages. J Intensive Care Soc. 2019;20(4):363‐369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jarden RJ, Sandham M, Siegert RJ, Koziol‐McLain J. Conceptual model for intensive care nurse work well‐being: a qualitative secondary analysis. Nurs Crit Care. 2020;25(2):74‐83. 10.1111/nicc.12485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. The Faculty of Intensive Care Medicine. Bridging guidance for critical care during restoration of NHS services Web site; 2020. https://www.baccn.org/static/uploads/resources/ficm_bridging_guidance_for_critical_care_during_the_restoration_of_nhs_service_AkrupyL.pdf. Accessed May 25, 2020.

- 6. Tabah A, Ramanan M, Laupland KB, et al. Personal protective equipment and intensive care unit healthcare worker safety in the COVID‐19 era (PPE‐SAFE): an international survey. J Crit Care. 2020;59:70‐75. 10.1016/j.jcrc.2020;06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Morley G. Recognizing and managing moral distress during the COVID‐19 pandemic: a guide for nurses. https://www.baccn.org/media/resources/COVID-19_Moral_Distress_Slides_Morley_2020.pdf. Accessed August 7, 2020.

- 8. St Ledger U, Begley A, Reid J, Prior L, McAuley D, Blackwood B. Moral distress in end‐of‐life care in the intensive care unit. J Adv Nurs. 2013;69(8):1869‐1880. 10.1111/jan.12053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. The British Psychological Society . The psychological needs of healthcare staff as a result of the coronavirus pandemic. British Psychological Society Covid19 Staff Wellbeing Group. https://www.bps.org.uk/sites/www.bps.org.uk/files/News/News-Files/Psychologicalneedsofhealthcarestaff.pdf. Assessed April 1, 2020.

- 10. Adams AMN, Chamberlain D, Giles TM. The perceived and experienced role of the nurse unit manager in supporting the wellbeing of intensive care unit nurses: an integrative literature review. Aust Crit Care. 2019;32(4):319‐329. 10.1016/j.aucc.2018.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Intensive Care Society (ICS) . Advice for sustaining staff wellbeing in critical care during and beyond COVID‐19; 2020. https://232fe0d6‐f8f4‐43eb‐bc5d‐6aa50ee47dc5.filesusr.com/ugd/360df8_baf9969e1dd1464686a86fbb57484d1b.pdf. Accessed August 25, 2020.

- 12. Cleary M, Kornhaber R, Thapa DK, West S, Visentin D. The effectiveness of interventions to improve resilience among health professionals: a systematic review. Nurs Educ Today. 2018;71:247‐263. 10.1016/j.nedt.2018.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nursing Midwifery Council (NMC) . The Code: professional standards of practice and behaviour for nurses, midwives and nursing associates; 2018. https://www.nmc.org.uk/standards/code/. Accessed May 27, 2020.

- 14. Bennett‐Levy J. Why therapists should walk the talk: the theoretical and empirical case for personal practice in therapist training and professional development. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2019;62:133‐145. 10.1016/j.jbtep.2018.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kotera Y, Green P, Sheffield D. Mental attitudes, self‐critcism, compassion and role identity among UK social work students. Br J Soc Work. 2019;49(2):351. 10.1093/bjsw/bcz149. [DOI] [Google Scholar]