Abstract

We established a pulsed fluidized bed system to dry and concurrently separate fine lignite (−6 + 3 and −3 + 1 mm lignite). The kinetics and evaporation of lignite moisture were investigated in the pulsed air flow. The variation in the evaporation rate was studied theoretically with respect to temperature, velocity of the pulsed air flow, and pulsed frequency. The rubbing effect between the air and lignite particle probably dominates the evaporation of water. The influence of temperature on the evaporation rate is more significant than that of air velocity by merely considering the effect of air entrainment of the evaporated moisture. Four operational parameters, including inlet temperature, air velocity, pulsating frequency, and bed height, were investigated and optimized through a response surface method to study the interactions between factors and determine the optimal separation conditions. Results indicate that the maximum standard deviation of the ash content of 23.74% was recorded under the optimal condition of the inlet temperature (80 °C), pulsating frequency (3.93 Hz), air velocity (1.09 m/s), and bed height (120 mm) for −6 + 3 mm lignite, and the maximum standard deviation of 24.99% was recorded for −3 + 1 mm lignite under the condition of the inlet temperature (100 °C), pulsating frequency (3.49 Hz), air velocity (0.55 m/s), and bed height (80 mm). The probable error values of separations of −6 + 3 mm lignite and −3 + 1 mm lignite with the pulsed fluidized bed were 0.12–0.16 and 0.10–0.16 g/cm3, respectively, which demonstrates that efficient drying and simultaneous separation of lignite can be achieved with the pulsed fluidized bed.

1. Introduction

To meet the increasing demand of energy sources, lignite has been widely used as a primary energy supply because of the large reserves and low mining cost.1−3 It is estimated that lignite accounts for approximately 13% of coal reserves in China2−4 and 19.8% of the Germany’s gross electricity generation in 2019, according to the report by the Fraunhofer Institute for Solar Energy Systems ISE.1,5,6 However, direct combustion of lignite potentially results in low combustion efficiency, high transportation cost, and potential damage of the combustor because of the high moisture content (20–55 wt %),3 high ash content, high volatile content, and low calorific value of lignite. Drying and beneficiation before utilization is the most effective and economical method for discarding hazardous components and gangue,3 thereby alleviating environmental pollution and improving the calorific capacity of lignite.

Fluidized bed drying and separation have numerous advantages such as high processing capacity, low cost, and low energy consumption7−9 and have been widely implemented in numerous fields, such as food processing, coating, and so forth. With purposes of drying lignite and simultaneously discarding gangue, numerous experiments have been conducted with fluidized beds10−13 and reported with efficient results in the drying and separation of wet particles.3,4,9,13−17 Lignite particles with high moisture content are very likely bounded with a water bridge, which restricts the free movement of the lignite particle in the fluidized bed. The water bridge enables the agglomeration of fine lignite particles, deteriorating the fluidization effect of lignite particles. The pulsed fluidized bed is a typical additional field fluidized bed,18−20 which uses pulsating air flow to promote the stratification of particles based on density difference and improve the drying performance and separation efficiency. The pulsed fluidized bed shows characteristics such as the absence of magnetite powder, low energy consumption, and high processing capacity. Meanwhile, this drying technology can utilize the industrial waste heat exhaust gas to dry the fine lignite, which is also an environment-friendly and cost-effective technology. Despite these advantages, the evaporation mechanisms underlying the lignite drying process and the combined effect of different factors on lignite drying and separation in the pulsed fluidized bed have been barely reported.

In the proposed work, the evaporation rate of the vapor was derived based on the Hertz–Knudsen equation by considering the influence of the temperature, air flow velocity, and the pulsating frequency. We primarily investigated the effect of the entrainment of the vapor molecules by the upstreaming air on the evaporation rate (Section 4.4). The independent variation trend of the evaporation rate with respect to the factors was also studied (Section 2.1). Afterward, the −6 + 3 mm lignite and −3 + 1 mm lignite were selected as separation objects to test and verify the feasibility and flexibility of using the pulsed fluidized bed to separate lignites of two different size ranges (Sections 2.2–2.4). Statistical analyses were implemented to optimize the process parameters of drying and separation of −6 + 3 mm lignite and −3 + 1 mm lignite. Four factors, including inlet temperature, air velocity, pulsating frequency, and bed height, were investigated and optimized through the response surface methodology21,22 to study the interactions between factors and determine the optimal separation conditions for −6 + 3 mm lignite and −3 + 1 mm lignite.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Variation in the Evaporation Rate

We used eq 14 to study the dependence of the evaporation rate on different factors. The results are shown in Figure 1. Within the temperature range of 280–360 K, the variation curves of the evaporation rate with respect to temperature barely have any difference under different air velocities, indicating that the influence of temperature on the evaporation rate is more significant than that of air velocity. However, numerous experimental research studies have reported the converse results.23,24 Putra and Ajiwiguna (2017) investigated the relative influence of temperature and air velocity on drying process and concluded that the drying effect at high air velocity (1.6–2.8 m/s) is more significant than that of temperature.23 An analogical result was also achieved by Sheng et al. (2018). In the temperature range of 40–60 °C and air velocity range of 2–6 m/s, the increase of air velocity accelerates the drying of water more significantly than that of temperature, according to the work of Chandramohan (2018).26 This is because air flow briefly contributes to the drying of lignite particles in three ways. The first is the intensive friction between air and lignite particles, rubbing away the surface moisture. This way probably dominates the evaporation of water. Another way is that the air carries water vapor quickly away from the lignite particle, creating an ambient with unsaturated vapor pressure that favors the evaporation of water. Pulsating frequency influences the rate of evaporation in a way analogous to the influence of air velocity, as the pulsating frequency determines the temporal variation of air velocity, thereby promoting the evaporation of water. The third one is the internal moisture evaporation. At the constant drying rate, the temperature of the lignite particle remains constant. Hence, the effect of temperature on the internal moisture evaporation is less significant than that of air velocity.

Figure 1.

Dependence of the evaporation rate on the temperature (a) and air velocity (b). [The change in the evaporation rate with respect to temperature was investigated under two air velocities (1 and 100 m/s); vmin is assumed to be 300 m/s in the calculation].

2.2. Experimental Result Analysis for −6 + 3 mm Lignite

The experimental results for −6+3 mm lignite are shown in Table 1. Generally, the standard deviation of the ash content varies from 20.30 to 23.74%. The maximum standard deviation of the ash content of 23.74% was recorded under the optimal condition of the inlet temperature (80 °C), pulsating frequency (3.93 Hz), air velocity (1.09 m/s), and bed height (120 mm) for −6 + 3 mm lignite. We used the linear, two-factor interaction (2FI), quadratic polynomial, and cubic polynomial models to fit the standard deviation of the ash content. The model summaries are shown in Tables 2 and 3. Table 2 compares residual errors with pure errors from the replicated design points. The quadratic model, suggested as the likely model, has a relatively larger probability value compared with the linear model and 2FI model. In the tests, the quadratic model takes the smallest F value aside from the cubic model, which is aliased. Hence, the quadratic model can be considered as the optimal model.

Table 1. Orthogonal Experimental Design for −6 + 3 mm Lignite.

| factor A | factor B | factor C | factor D | response | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| std | run | inlet temperature (°C) | pulsating frequency (Hz) | air velocity (m/s) | bed height (mm) | σash (—) |

| 7 | 1 | 80.00 | 3.93 | 1.02 | 140.00 | 22.25 |

| 27 | 2 | 80.00 | 3.93 | 1.09 | 120.00 | 23.54 |

| 26 | 3 | 80.00 | 3.93 | 1.09 | 120.00 | 23.74 |

| 13 | 4 | 80.00 | 3.49 | 1.02 | 120.00 | 20.98 |

| 1 | 5 | 60.00 | 3.49 | 1.09 | 120.00 | 21.53 |

| 3 | 6 | 60.00 | 4.36 | 1.09 | 120.00 | 20.87 |

| 24 | 7 | 80.00 | 4.36 | 1.09 | 140.00 | 22.05 |

| 16 | 8 | 80.00 | 4.36 | 1.16 | 120.00 | 21.62 |

| 17 | 9 | 60.00 | 3.93 | 1.02 | 120.00 | 21.74 |

| 21 | 10 | 80.00 | 3.46 | 1.09 | 100.00 | 22.21 |

| 10 | 11 | 100.00 | 3.93 | 1.09 | 100.00 | 21.19 |

| 14 | 12 | 80.00 | 4.36 | 1.02 | 120.00 | 21.06 |

| 9 | 13 | 60.00 | 3.93 | 1.09 | 100.00 | 21.71 |

| 20 | 14 | 100.00 | 3.93 | 1.16 | 120.00 | 21.06 |

| 2 | 15 | 100.00 | 3.49 | 1.09 | 120.00 | 20.87 |

| 5 | 16 | 80.00 | 3.93 | 1.03 | 100.00 | 22.82 |

| 15 | 17 | 80.00 | 3.49 | 1.16 | 120.00 | 22.59 |

| 8 | 18 | 80.00 | 3.93 | 1.16 | 140.00 | 23.48 |

| 28 | 19 | 80.00 | 3.93 | 1.09 | 120.00 | 23.54 |

| 6 | 20 | 80.00 | 3.93 | 1.16 | 100.00 | 22.30 |

| 12 | 21 | 100.00 | 3.93 | 1.09 | 140.00 | 22.10 |

| 23 | 22 | 80.00 | 3.49 | 1.09 | 140.00 | 22.39 |

| 29 | 23 | 80.00 | 3.93 | 1.09 | 120.00 | 23.14 |

| 11 | 24 | 60.00 | 3.93 | 1.09 | 140.00 | 22.34 |

| 22 | 25 | 80.00 | 4.36 | 1.09 | 100.00 | 21.57 |

| 25 | 26 | 80.00 | 3.93 | 1.09 | 120.00 | 23.24 |

| 19 | 27 | 60.00 | 3.93 | 1.16 | 120.00 | 21.55 |

| 18 | 28 | 100.00 | 3.93 | 1.02 | 120.00 | 20.30 |

| 4 | 29 | 100.00 | 4.36 | 1.09 | 120.00 | 20.37 |

Table 2. Lack of Fit Test for the Standard Deviation of the Ash Content of −6 + 3 mm Lignitea.

| source | sum of squares | DOF | mean square | F value | prob > F | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| linear | 74.85 | 20 | 3.74 | 102.06 | 0.0002 | |

| 2FI | 66.58 | 14 | 4.76 | 129.69 | 0.0001 | |

| quadratic | 2.38 | 10 | 0.24 | 6.49 | 0.0432 | auggested |

| cubic | 0.014 | 2 | 0.007 | 0.19 | 0.8327 | aliased |

| pure error | 0.15 | 4 | 0.037 |

DOF: Total degrees of freedom; F value: test statistic used to determine whether any term in the model is associated with the response.

Table 3. Model Summary Statistics for the Standard Deviation of the Ash Content of −6 + 3 mm Lignitea.

| type | standard deviation | R2 | adjusted R2 | predicted R2 | PRESS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| linear | 0.98 | 0.1455 | 0.0030 | –0.1543 | 29.39 | |

| 2FI | 1.07 | 0.1964 | –0.2501 | –0.8277 | 46.54 | |

| quadratic | 0.26 | 0.9641 | 0.9282 | 0.8142 | 4.73 | suggested |

| cubic | 0.22 | 0.9883 | 0.9455 | 0.0329 | 24.63 | aliased |

R2: coefficient of determination; adjusted R2: coefficient of determination adjusted for the number of coefficients; and PRESS: prediction residual sum of squares.

The same conclusion can be drawn from Table 3. From model summary statistics, the quadratic model comes out as the best model, which exhibits low standard deviation, high R2 value, and a low predicted residual sum of squares (PRESS). Hence, the quadratic model was underlined as the suggested model. Based on these analyses, a quadratic model was achieved. The formula (factor code unit-based) is given in eq 1.

| 1 |

2.3. Experimental Result Analysis for −3 + 1 mm Lignite

The experimental results for −3 + 1 mm lignite are shown in Table 4. The standard deviation of the ash content σash differs from 19.34 to 24.99%, which is analogous to the σash result for −6 + 3 mm lignite. The maximum σash of 24.99% was recorded under the optimal condition of the inlet temperature (100 °C), pulsating frequency (3.49 Hz), air velocity (0.55 m/s), and bed height (80 mm) for −3 + 1 mm lignite. Furthermore, the orthogonal experiment results were analyzed. The linear, 2FI, quadratic polynomial, and cubic polynomial models were fitted to the standard deviation of the ash content. The fitting summary is shown in Table 5.

Table 4. Orthogonal Experimental Design for −3 + 1 mm Lignite.

| factor A | factor B | factor C | factor D | response | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| std | run | inlet temperature (°C) | pulsating frequency (Hz) | air velocity (m/s) | bed height (mm) | σash (—) |

| 22 | 1 | 100.00 | 3.06 | 0.61 | 80.00 | 21.02 |

| 4 | 2 | 100.00 | 3.49 | 0.61 | 100.00 | 20.48 |

| 2 | 3 | 100.00 | 3.49 | 0.48 | 100.00 | 20.02 |

| 19 | 4 | 110.00 | 3.49 | 0.55 | 60.00 | 21.78 |

| 13 | 5 | 90.00 | 3.49 | 0.48 | 80.00 | 22.58 |

| 15 | 6 | 110.00 | 3.49 | 0.48 | 80.00 | 23.73 |

| 29 | 7 | 100.00 | 3.49 | 0.55 | 80.00 | 24.86 |

| 28 | 8 | 100.00 | 3.49 | 0.55 | 80.00 | 24.56 |

| 7 | 9 | 90.00 | 3.93 | 0.55 | 80.00 | 23.71 |

| 26 | 10 | 100.00 | 3.49 | 0.55 | 80.00 | 24.78 |

| 14 | 11 | 90.00 | 3.49 | 0.61 | 80.00 | 23.50 |

| 9 | 12 | 100.00 | 3.06 | 0.55 | 60.00 | 21.17 |

| 20 | 13 | 110.00 | 3.49 | 0.55 | 100.00 | 23.47 |

| 17 | 14 | 90.00 | 3.49 | 0.55 | 60.00 | 24.09 |

| 3 | 15 | 100.00 | 3.49 | 0.61 | 60.00 | 20.03 |

| 1 | 16 | 100.00 | 3.49 | 0.48 | 60.00 | 21.48 |

| 25 | 17 | 100.00 | 3.49 | 0.55 | 80.00 | 24.55 |

| 21 | 18 | 100.00 | 3.06 | 0.48 | 80.00 | 21.69 |

| 8 | 19 | 110.00 | 3.93 | 0.55 | 80.00 | 23.90 |

| 27 | 20 | 100.00 | 3.49 | 0.55 | 80.00 | 24.99 |

| 23 | 21 | 100.00 | 3.93 | 0.48 | 80.00 | 21.79 |

| 10 | 22 | 100.00 | 3.06 | 0.55 | 100.00 | 21.90 |

| 5 | 23 | 90.00 | 3.06 | 0.55 | 80.00 | 24.08 |

| 6 | 24 | 110.00 | 3.06 | 0.55 | 80.00 | 22.19 |

| 18 | 25 | 90.00 | 3.49 | 0.55 | 100.00 | 22.99 |

| 24 | 26 | 100.00 | 3.93 | 0.61 | 80.00 | 19.34 |

| 12 | 27 | 100.00 | 3.93 | 0.55 | 100.00 | 20.40 |

| 11 | 28 | 100.00 | 3.93 | 0.55 | 60.00 | 21.11 |

| 16 | 29 | 110.00 | 3.49 | 0.61 | 80.00 | 21.20 |

Table 5. Model Summary Statistics for the Standard Deviation of the Ash Content of −3 + 1 mm Lignite.

| type | standard deviation | R2 | adjusted R2 | predicted R2 | PRESS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| linear | 1.76 | 0.0617 | –0.0947 | –0.3060 | 103.31 | |

| 2FI | 1.92 | 0.1652 | –0.2986 | –1.0244 | 160.14 | |

| quadratic | 0.43 | 0.9675 | 0.9350 | 0.8206 | 14.19 | suggested |

| cubic | 0.17 | 0.9979 | 0.9902 | 0.9574 | 3.37 | aliased |

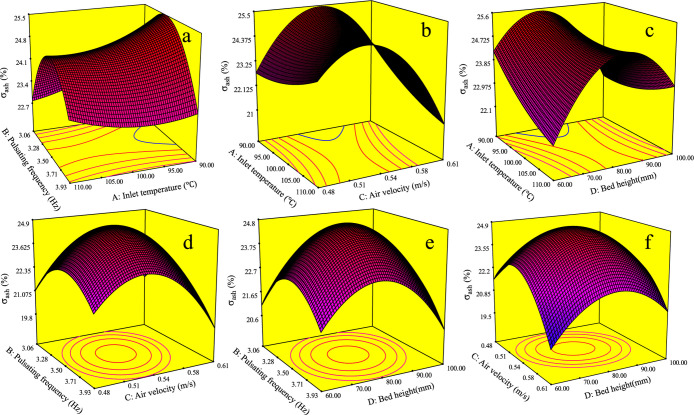

Based on the quadratic model, 3D response surfaces were generated and are illustrated in Figure 2 to explore to what extent the standard deviation of the ash content varies as functions of each combination of two factors. In the figure, the response surface marked with a red surface mesh can be considered as the representation of a function, which demonstrates the relationship between the dependent variable σash and two independent variables. The top point of the convex surface denotes the maximum σash, which is interpreted as the desirable result obtained under the optimized operation condition. The projection curves of concave surfaces demonstrate that the combination of air velocity and pulsating frequency, the combination of air velocity and inlet temperature, and the combination of inlet temperature and pulsating frequency have more significant influence on the outcome of the experiment, as the curvatures of projection curves vary significantly with these factors. Other combinations of each two factors have a less significant effect on σash because curvatures of projection curves barely change with bed height. This is because the bed is difficult to be stratified when the bed height increases, which deteriorates the separation efficiency.

Figure 2.

Response surface of the interaction effect between each two factors on σash (−6 + 3 mm lignite). (Figure 2a–f represents the variation in σash with respect to A and B factors, A and C factors, A and D factors, B and C factors, B and D factors, and C and D factors, respectively; A, B, C, and D denote inlet temperature, pulsating frequency, air velocity, and bed height, respectively).

Fitting results show that the quadratic model is the optimal model. It can be seen that the predicted quadratic sum of residual for the quadratic model has the minimum value aside from the aliased cubic model, which suggests that the quadratic model is the optimal model to fit the drying and separation characteristics of −3 + 1 mm lignite in the pulsed fluidized bed. Meanwhile, the quadratic model exhibits a low standard deviation and high R2 value. Hence, the quadratic model was underlined as the suggested model and is given by

| 2 |

3D response surfaces of the quadratic model were generated and are illustrated in Figure 3. It can be seen that each combination of two factors has a significant effect on σash. Compared with the experimental results of −6 + 3 mm lignite, the inlet temperature shows a less significant influence on σash. Probably, it is because wet fine lignite particles can readily agglomerate, as fine lignite particles were agglutinated tightly by water. The cohesive lignite particles are difficult to fluidize and separate. Meanwhile, the heterogeneous distribution of hot air flow in the pulsed fluidized bed further aggravated the drying of fine lignite particles, which diminishes the extent of the influence of the inlet temperature on σash.

Figure 3.

Response surface of the interaction effect between each two factors on σash (−3 + 1 mm lignite). (Figure 2a–f represents the variation of σash with respect to A and B factors, A and C factors, A and D factors, B and C factors, B and D factors, and C and D factors, respectively; A, B, C, and D denote inlet temperature, pulsating frequency, air velocity and bed height, respectively).

2.4. Separation Performance of Fine Lignite

The Ecart Probable/Moyen (Ep) was used to evaluate the efficiency of lignite separation in the pulsed fluidized bed. Based on the experiments discussed in the aforementioned section, the optimal operation conditions were determined for −6 + 3 mm lignite and −3 + 1 mm lignite. The operation parameters are listed in Table 6.

Table 6. Optimal Separation Parameters for −6 + 3 mm Lignite and −3 + 1 mm Lignite.

| lignite particle (mm) | inlet temperature °C | pulsating frequency (Hz) | bed height (mm) | air velocity (m/s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| –6 + 3 | 80 | 3.93 | 120 | 1.09 |

| –3 + 1 | 100 | 3.49 | 80 | 0.55 |

–6 + 3 mm lignite and −3 + 1 mm lignite were separated in the pulsed fluidized bed separately. The separation results were analyzed. Distribution rates were calculated and are illustrated in Tables 7 and 8 for −6 + 3 mm lignite and −3 + 1 mm lignite, respectively. Based on the data achieved in calculation tables, distribution curves were obtained and are illustrated in Figure 4.

Table 7. Calculation Table of Distribution Rates for −6 + 3 mm Lignite.

| sink–float product |

distribution

rate |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| density (g/cm3) | mean density (g/cm3) | gangue (%) | middling (%) | fine coal (%) | raw coal (%) | fine coal and middling (%) | high-density separation (%) | low-density separation (%) |

| –1.30 | 1.25 | 0.36 | 7.02 | 32.12 | 39.50 | 39.14 | 0.91 | 17.94 |

| 1.30–1.40 | 1.35 | 0.32 | 8.05 | 8.16 | 16.53 | 16.21 | 1.94 | 49.66 |

| 1.40–1.50 | 1.45 | 0.12 | 2.05 | 1.21 | 3.38 | 3.26 | 3.55 | 62.88 |

| 1.50–1.60 | 1.55 | 1.27 | 1.06 | 0.30 | 2.63 | 1.36 | 48.29 | 77.94 |

| 1.60–1.80 | 1.65 | 0.55 | 0.20 | 0.05 | 0.80 | 0.25 | 68.75 | 80.00 |

| 1.80–2.00 | 1.90 | 6.25 | 1.56 | 0.10 | 7.91 | 1.66 | 79.01 | 93.98 |

| +2.00 | 2.10 | 25.69 | 3.45 | 0.11 | 29.25 | 3.56 | 87.83 | 96.91 |

| total | 34.56 | 23.39 | 42.05 | 100.00 | 65.44 | |||

Table 8. Calculation Table of Distribution Rates for −6 + 3 mm Lignite.

| sink–float product |

distribution

rate |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| density (g/cm3) | mean density (g/cm3) | gangue (%) | middling (%) | fine coal (%) | raw coal (%) | fine coal and middling (%) | high-density separation (%) | low-density separation (%) |

| –1.30 | 1.25 | 1.08 | 4.87 | 26.21 | 32.16 | 31.08 | 3.36 | 15.67 |

| 1.30–1.40 | 1.35 | 1.15 | 5.80 | 12.76 | 19.71 | 18.56 | 5.83 | 31.25 |

| 1.40–1.50 | 1.45 | 0.55 | 3.89 | 1.82 | 6.26 | 5.71 | 8.79 | 68.13 |

| 1.50–1.60 | 1.55 | 0.40 | 2.04 | 0.45 | 2.89 | 2.49 | 13.84 | 81.93 |

| 1.60–1.80 | 1.65 | 1.27 | 0.78 | 0.16 | 2.21 | 0.94 | 57.47 | 82.98 |

| 1.80–2.00 | 1.90 | 3.90 | 1.23 | 0.10 | 5.23 | 1.33 | 74.57 | 92.48 |

| +2.00 | 2.10 | 29.81 | 1.62 | 0.11 | 31.54 | 1.73 | 94.51 | 93.64 |

| total | 38.16 | 20.23 | 41.34 | 100.00 | ||||

Figure 4.

Distribution curves for the separations of −6 + 3 mm lignite and −3 + 1 mm lignite.

It can be seen that the Ep values for −6 + 3 mm lignite and −3 + 1 mm lignite are 0.12–0.16 and 0.10–0.16 g/cm3, respectively. The smaller value of −3 + 1 mm lignite indicates that the segregation of −3 + 1 mm lignite is better than that of −6 + 3 mm lignite. This result is also demonstrated in the response surface analysis, where the σash value of −3 + 1 mm lignite is generally larger than that of −6 + 3 mm lignite. This is, to some extent, due to the effect of internal moisture evaporation in large lignite particles, which have a large internal surface area and probably possess more internal moisture. It takes more time for the internal moisture of −6 + 3 mm lignite to migrate to the exterior, deteriorating the drying and separation efficiency. In the pulsed fluidized bed, the size of large particles enlarges the voidage between particles. Hence, the air flow penetrates the bed easily, which incurs a relatively smaller bed expansion rate. Meanwhile, the dead zone and air-flow short circuit are likely to occur, which deteriorates the separation effect of lignite.

3. Conclusions

We derived the relation between the evaporation rate and the temperature, air velocity, and pulsating frequency. It can be concluded that the influence of temperature on the evaporation rate is more significant than that of air velocity without considering the intensive friction interaction between air flow and the surface moisture of lignite.

The maximum standard deviation of the ash content of 23.74% for −6 + 3 mm lignite was recorded under the optimal condition of the inlet temperature (80 °C), pulsating frequency (3.93 Hz), air velocity (1.09 m/s), and bed height (120 mm). The binary combinations of the inlet temperature, air velocity, and pulsating frequency have a more dramatic influence on the outcome of the experiment for −6 + 3 mm lignite. The maximum standard deviation of the ash content for −3 + 1 mm lignite was recorded as 24.99% under conditions of the inlet temperature (100 °C), pulsating frequency (3.49 Hz), air velocity (0.55 m/s), and bed height (80 mm). Generally, air velocity, pulsating frequency, and bed height have a more dramatic influence on the standard deviation of the ash content.

The Ep value was used to evaluate the separation efficiency of lignite under optimal operation conditions. The Ep values for separating −6 + 3 mm lignite and −3 + 1 mm lignite with the pulsed fluidized bed were 0.12–0.16 and 0.10–0.16 g/cm3, respectively, which verifies the feasibility and flexibility of utilizing the pulsed fluidized bed for the separation of −6 + 3 mm lignite and −3 + 1 mm lignite.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Experimental Materials

Lignite samples were taken from Shengli coal field in Inner Mongolia, China, and clarified as easy-to-wash coals.27 These samples were comminuted and then analyzed by sieving analysis, resulting in two granular levels, namely, −6 + 3 and −3 + 1 mm. Proximate analysis and ultimate analysis28 under a nitrogen atmosphere were conducted. The results are illustrated in Table 9. Total moisture contents of −6 + 3 mm lignite and −3 + 6 mm lignite are 31.66 and 29.99%, which are clarified as high moisture content lignite. High moisture content leads to an adverse effect in the combustion of lignite, as the evaporation of water requires a lot of thermal energy. The calorific capacities for −6 + 3 mm lignite and −3 + 1 mm lignite are 2667.50 and 2757.31 kcal/kg, respectively, which are much lower than that of standard thermal coal. Prior to being utilized in an economical and environment-friendly way, lignite is required to be dried and separated in order to reduce the moisture content and ash content and increase the calorific capacity correspondingly.

Table 9. Proximate Analysis and Ultimate Analysis Results of Lignite Coal Samples.

| granularity level (mm) | total moisture Mt (%) | internal moisture Mad (%) | ash content Ad (%) | volatile content Vdaf (%) | fixed carbon FCdaf (%) | calorific capacity (kcal/kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| –6 + 3 | 31.66 | 13.79 | 27.51 | 47.12 | 52.88 | 2667.50 |

| –3 + 1 | 29.99 | 10.34 | 27.81 | 46.44 | 53.56 | 2757.31 |

4.2. Experimental Apparatus

The experimental apparatus used for drying and separating lignite in the pulsed fluidized bed is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Schematic diagram of the experimental setup. [(1) Electric motor; (2) draft fan; (3) waste heat gas filter; (4) manometer; (5) air bellow; (6) gas heater; (7) ball valve; (8) flowrator; (9) frequency converter; (10) butterfly valve; (11) fluidized bed; and (12) thermocouple].

The core parts of the apparatus are as follows: gas heater, pulsating system, and fluidized bed with thermocouple heating equipment. The gas heater equipment includes an electrical heater and controller. The fluidized bed consists of air chamber, air distributor, bed body column, and a top cover. The column of the fluidized bed has a height of 0.4 m and inner diameter of 0.08 m. The air distributor, which is located between the bed column and air chamber, has a structure where the filtration fabric is sandwiched by two steel-punched plates. Round apertures with a constant diameter of 0.4 cm are distributed uniformly on the punched plate, resulting in an aperture ratio of approximately 24%. The top cover is connected to a pipe, through which the exhausted gas and dust are collected. The electrical heater consists of electrical heating tubes. The controller is responsible for setting the range of heating temperatures in order to satisfy experimental requirements. The electrical heater stops working until the given temperature value is achieved. Otherwise, when the temperature is lower than the given temperature, the controller switches on the electrical heater automatically. In the heating process, it is imperative to have the gas involved inside the heater. The pulsating system possesses an electromotor, decelerator, transducer, and butterfly valve. When the butterfly valve rotates, the gas velocity varies from the minimum value to the maximum value in half revolution. Thus, two gas flow pulses were generated in one revolution. The air velocity was calculated based on eq 3.

| 3 |

where u0 is the constant air flow and ω denotes the rotation angle of the valve.

The electromotor speed was set as 1440 rpm in the experiment. The reduction ratio of the decelerator was 11:1. With comprehensive consideration of the electromotor speed and the reduction ratio, the correlation between the frequency of pulsating air f and output frequency of the transducer fp is shown in eq 4.

| 4 |

The drying and separation procedure of fine lignite coal can be described as follows: the air was transported into the air bellow by a draught fan. Constant air flow was delivered through the gas heater, where the air was heated up to a certain temperature. Then, through the pipe, the heated air entered the butterfly section, where the pulsating air flow was generated. After that, the pulsating air flow was ejected into the fluidized bed across the air-distributing chamber. The system (Figure 5) was also designed to utilize the waste heat flue gas as the heat source to dry lignite in order to save energy. The waste heat flue gas was transported into the gas filter under the effect of a draught fan. Then, the filtered gas entered the butterfly section, where the pulsating air flow was generated and ejected into the fluidized bed.

Because of the density difference between the coal particle and gangue particle, coal particles were drifted and separated from gangue particles. In the experimental process, the inlet and outlet temperatures and the temperature inside the bed were measured using the thermocouple. The variation in temperature at different locations was recorded and analyzed. The separation time was set as 3 min.27 The lignite was sampled with a sampler. After each experiment, the top cover of the fluidized bed was opened. Then, the lignite can be sampled from the top of the fluidized bed. The as-received lignite sample was immediately weighted. The moisture content, which is defined on a dry basis, is the ratio of the weight of water to the weight of dry lignite.

4.3. Evaluation Index for Separation Efficiency

In the separation process, lignite was dried and simultaneously segregated under the combination effect of pulsating energy and thermal energy. The bed was restored to a stationary status after the experiment. The bed was divided equally into four layers. The ash content of each layer product was determined, as well as the segregation standard deviation of ash contents (σash) to investigate lignite separation efficiency in the pulsed fluidized bed. Formulas are shown as follows

| 5 |

| 6 |

where A(i) (%) is the ash content of i-layer product; γ(i) (%) denotes the productive rate of i-layer product; and A̅ (%) is the weighted mean of ash contents of all layer products. A̅ is equal to the ash content of raw lignite coal.

4.4. Theoretical Analysis of the Drying Process in the Pulsed Fluidized Bed

The drying of lignite generally involves the following processes: (1) The evaporation of surface moisture adhered to lignite particles; (2) heat diffusion from the surface to the interior of lignite particles; (3) the evaporation of the moisture adhered to the internal surface of the lignite porous structure; and (4) the diffusion and convection of water vapor under the effect of upstreaming air flow.

Generically, the evaporation of water from a liquid surface is always associated with the condensation of water on the liquid surface. The rate of evaporation and the rate of condensation of the vapor are calculated with the Hertz–Knudsen equation29,30

| 7 |

where Nl and Nv (—) are the number of the liquid and vapor molecules, respectively; S (m2) represents the surface area of the liquid; t (s) is the time; α (—) denotes the condensation coefficient; peq (Pa) represents liquid–vapor equilibrium pressure; p (Pa) is the vapor partial pressure near the liquid surface; m (kg) denotes the mass of a vapor molecule; kB (J·K–1) is the Boltzmann constant (by definition: kB = 1.380649 × 10–23 J·K–1), and T (K) denotes the temperature.

In eq 7, the rate of evaporation is influenced by α, peq, p, and T. However, in the pulsed fluidized bed, the upstreaming air flow carries the vaporized water away from the surface of lignite particles promptly after the water molecule enters the air. Thus, p is negligible compared with peq (i.e., p ≪ peq). In the pulsed fluidized bed drying process, the temperature of the hot upstreaming air flow ranges from 333.15 to 373.15 K (60–100 °C). Within this temperature range, peq can be calculated with the Buck equation31

| 8 |

where T (K) is the temperature in Kelvin. It can be seen from Figure 6 that the predicted saturated vapor pressures (Buck equation) correspond to the experimental data32 very well.

Figure 6.

Saturated vapor pressure variation with respect to temperature.

The pulsed air flow also exerts an influence on the rate of evaporation. For the study of evaporation and condensation processes, it is normally simplified that the distribution function of velocities of vapor molecules is Maxwellian. Because of the fact that at a nonequilibrium state, for instance, vapor molecules constantly drifted away from the liquid surface by the upstreaming air flow with the velocity of u, the average velocity of vapor molecules is nonzero. Meanwhile, the upper boundary of the fluidized bed is in contact with the atmosphere, where the velocity distribution of vapor follows Maxwellian. Thus, we consider local Maxwellian velocity distribution for vapor molecules for a single direction (same as the direction of upstreaming air flow) as

| 9 |

where f(v) is the velocity distribution function in one direction; v (m·s–1) is the vapor velocity, which consists of two parts (v = u + w): mean velocity of vapor gas flow u and (pulsed air velocity) and peculiar velocity w; the peculiar velocity is defined as the random motion velocity of a vapor molecule in the direction of upstreaming air flow; and the ensemble average of peculiar velocity ⟨w⟩ = 0.

In the collision theory, vapor molecules pass through the liquid surface by overcoming a certain energy barrier.29 Vlasov (2019) assumed that the energy barriers for the evaporation and condensation of molecules are approximately equal to the activation energies Eev and Econ in the framework of chemical kinetics, respectively. Econ is defined as29

| 10 |

where vmin is the threshold velocity; if v < vmin, no single vapor molecule will condense. If v ≥ vmin, it will condense.

Thus, we calculate the total number of collisions of vapor molecules with the liquid surface with eq 11(29)

| 11 |

where c (mol·m–3) is the vapor molar concentration near the liquid surface and ⟨v⟩ is the average speed of the vapor molecules. Similarly, the number of vapor molecules that condense on the liquid surface is given by29

| 12 |

Then, we can determine the condensation coefficient α as

| 13 |

It can be seen from eq 13 that α depends on vmin, u, and T. Substituting eqs 3, 8, and 13 into 7, we obtain that

|

14 |

Equation 14 helps us to directly study the independent variation trend of the evaporation rate with respect to temperature, air flow velocity, and the pulsating frequency and offers guidance to the experimental research studies.

4.5. Optimization of Lignite Drying and Separation Using the Response Surface Method

The response surface method (RSM) is widely used as a statistical approach to optimize the multifactor experiments.33 With the RSM, it is possible to determine the relationship between the objective variable and the input variables and the relative influence of input parameters on the objective function. The RSM is a representative method to approximate the true model.34 The principle behind the approximation is that the metamodels, like quadratic or cubic models, are constructed with unknown model parameters. Then, the metamodel is evaluated at multiple sample points to determine model parameters by minimizing the error in the model.34,35 The sample experiment points were determined based on an orthogonal experimental design, where four variables, namely, inlet temperature, pulsating frequency, air velocity, and bed height were analyzed. These variables were reported to have a significant effect on the segregation standard deviation of ash contents (σash).23−25,27 We implemented the RSM and designed the orthogonal experiments to optimize the operation conditions for drying and simultaneously separating lignite particles.

Four factors, namely, the inlet temperature, pulsating frequency, air velocity, and bed height were selected and analyzed. Experimental designs of different factors and levels are shown in Table 10 for −6 + 3 and −3 + 1 mm lignites. These air velocities were chosen in a way that sufficient diffusion and stratification of lignite particles promote and intensify the separation process of lignite in the pulsed fluidized bed.

Table 10. Experimental Designs of Four Factors and Three Levels.

| –6 + 3 mm lignite |

–3 + 1 mm lignite |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| code | factor | unit | max. | min. | max. | min. | level |

| A | inlet temperature | °C | 60 | 100 | 90 | 110 | 3 |

| B | pulsating frequency | Hz | 3.49 | 4.36 | 3.06 | 3.93 | 3 |

| C | air velocity | m/s | 1.02 | 1.16 | 0.48 | 0.61 | 3 |

| D | bed height | mm | 100 | 140 | 60 | 100 | 3 |

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Miao Pan (China University of Mining and Technology) for the helpful support with the schematic diagram of the experimental setup. The authors acknowledge the financial support by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (no. 2019QNA16).

Glossary

Nomenclature

- A

surface area of the liquid [m2]

- A(i)

the ash content of i-layer product [%]

- A̅

weighted mean of ash contents of all layer products [%]

- Eev

activation energy for the evaporation of vapour molecule [kJ mol–1]

- Nl

the number of the liquid molecules [—]

- Nv

the number of the vapour molecules [—]

- T

temperature [K]

- c

vapour molar concentration near the liquid surface [mol m–3]

- f

the frequency of pulsating air flow [Hz]

- fp

output frequency of transducer [Hz]

- f(v)

particle distribution function in one direction [—]

- kB

Boltzmann constant [J·K–1]

- m

the mass of a vapour molecule [kg]

- p

vapour partial pressure near the liquid surface [Pa]

- peq

liquid–vapour equilibrium pressure [Pa]

- t

time [s]

- u

pulsed air velocity [m·s–1]

- u0

constant air flow [m·s–1]

- v

the particle velocity [m·s–1]

- vmin

threshold velocity [m·s–1]

- ⟨v⟩

the average speed of the vapour molecules [m·s–1]

- w

peculiar velocity [m·s–1]

Glossary

Greek letter

- α

condensation coefficient [—]

- σash

segregation standard deviation of ash content [—]

- ω

rotation angle of the valve [rad]

- Ω

the total number of collision of vapour molecules [—]

- Ωcon

the number of vapour molecules that condense on the liquid surface [—]

- γ(i)

productive rate of i-layer product [%]

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Andruleit H.; Babies H.; Fleig S.; Ladage S.; Messner J.; Pein M.; Rebscher D.; Schauer M.; Schmidt S.; Goerne G.. Energy study 2016. Reserves, Resources and Availability of Energy Resources 2011. Energy Study; Federal Institute for Geosciences and Natural Resources (BGR): Hannover, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Yu J.; Tahmasebi A.; Han Y.; Yin F.; Li X. A review on water in low rank coals: the existence, interaction with coal structure and effects on coal utilization. Fuel Process. Technol. 2013, 106, 9–20. 10.1016/j.fuproc.2012.09.051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao P.; Zhao Y.; Luo Z.; Chen Z.; Duan C.; Song S.; Dong L. Feasibility studies of the sequential dewatering/dry separation of Chinese lignite in a vibration fluidized-bed dryer: effect of physical parameters and operation conditions. Energy Fuels 2014, 28, 4383–4391. 10.1021/ef5005418. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang K.; You C. Experimental and numerical investigation of lignite particle drying in a fixed bed. Energy Fuels 2011, 25, 4014–4023. 10.1021/ef200759t. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buyanov V. BP: Statistical review of world energy 2011. Econ. Pol. 2011, 4, 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Public net electricity generation in Germany 2019: Share from renewables exceeds fossil fuels. 2020, https://www.ise.fraunhofer.de/en/press-media/news/2019/Public-net-electricity-generation-in-germany-2019.html (accessed July 8, 2020).

- Osman H.; Jangam S. V.; Lease J. D.; Mujumdar A. S. Drying of low-rank coal (LRC)-a review of recent patents and innovations. Dry. Technol. 2011, 29, 1763–1783. 10.1080/07373937.2011.616443. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng C.; Zhao Y.; Duan C.; Zhang B.; Feng P.; Lv K.; Yuan W.; Zhang P.; Zhou C. Establishment and evaluation of a dynamic pressure measuring and analysis system for the air dense medium fluidized bed. Procedia Eng. 2015, 102, 1546–1554. 10.1016/j.proeng.2015.01.290. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wei L.; Zhu X.; Liu D.; Wan G.; Zeng M.; Wang J. Fluidized drying of lignite under mild conditions. J. China Univ. Min. Technol. 2014, 43, 300–304. [Google Scholar]

- Tahmasebi A.; Yu J.; Han Y.; Li X. A study of chemical structure changes of Chinese lignite during fluidized-bed drying in nitrogen and air. Fuel Process. Technol. 2012, 101, 85–93. 10.1016/j.fuproc.2012.04.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tahmasebi A.; Yu J.; Han Y.; Yin F.; Bhattacharya S.; Stokie D. Study of chemical structure changes of Chinese lignite upon drying in superheated steam, microwave, and hot air. Energy Fuels 2012, 26, 3651–3660. 10.1021/ef300559b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoehne O.; Lechner S.; Schreiber M.; Krautz H. J. Drying of lignite in a pressurized steam fluidized bed-Theory and experiments. Dry. Technol. 2009, 28, 5–19. 10.1080/07373930903423491. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao P.; Zhao Y.; Chen Z.; Luo Z. Dry cleaning of fine lignite in a vibrated gas-fluidized bed: Segregation characteristics. Fuel 2015, 142, 274–282. 10.1016/j.fuel.2014.11.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T.-J.; Jin Y.; Tsutsumi A.; Wang Z.; Cui Z. Energy transfer mechanism in a vibrating fluidized bed. Chem. Eng. J. 2000, 78, 115–123. 10.1016/s1385-8947(00)00160-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Azimi E.; Karimipour S.; Rahman M.; Szymanski J.; Gupta R. Evaluation of the performance of air dense medium fluidized bed (ADMFB) for low-ash coal beneficiation. Part 1: Effect of operating conditions. Energy Fuels 2013, 27, 5595–5606. 10.1021/ef400456n. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Katalambula H.; Gupta R. Low-grade coals: A review of some prospective upgrading technologies. Energy Fuels 2009, 23, 3392–3405. 10.1021/ef801140t. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- He J.; Zhao Y.; Zhao J.; Luo Z.; Duan C.; He Y. Enhancing fluidization stability and improving separation performance of fine lignite with vibrated gas-solid fluidized bed. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 2015, 93, 1793–1801. 10.1002/cjce.22272. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dong L.; Zhang Y.; Zhao Y.; Peng L.; Zhou E.; Cai L.; Zhang B.; Duan C. Effect of active pulsing air flow on gas-vibro fluidized bed for fine coal separation. Adv. Powder Technol. 2016, 27, 2257–2264. 10.1016/j.apt.2016.08.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dong L.; Zhao Y.; Duan C.; Luo Z.; Zhang B.; Yang X. Characteristics of bubble and fine coal separation using active pulsing air dense medium fluidized bed. Powder Technol. 2014, 257, 40–46. 10.1016/j.powtec.2014.02.049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duan C.; Yuan W.; Cai L.; Lv K.; Zhao Y.; Zhang B.; Dong L.; Lv P. Characteristics of fine coal beneficiation using a pulsing air dense medium fluidized bed. Powder Technol. 2015, 283, 286–293. 10.1016/j.powtec.2015.05.033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J.; Sun H.; Pan C.; Fan Y.; Hou H. Optimization of process parameters for directly converting raw corn stalk to biohydrogen by Clostridium sp. FZ11 without substrate pretreatment. Energy Fuels 2015, 30, 311–317. 10.1021/acs.energyfuels.5b01766. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koca S.; Aksoy D. O.; Cabuk A.; Celik P. A.; Sagol E.; Toptas Y.; Oluklulu S.; Koca H. Evaluation of combined lignite cleaning processes, flotation and microbial treatment, and its modelling by Box Behnken methodology. Fuel 2017, 192, 178–186. 10.1016/j.fuel.2016.12.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Putra R. N.; Ajiwiguna T. A. Influence of air temperature and velocity for drying process. Procedia Eng. 2017, 170, 516–519. 10.1016/j.proeng.2017.03.082. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ndukwu M. C. Effect of drying temperature and drying air velocity on the drying rate and drying constant of cocoa bean. Agric. Eng. Int. 2009, 11, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Sheng C.; Duan C.; Zhao Y.; Zhang P.; Dong L. Separation and upgrading of fine lignite in pulsed fluidized bed. 1. experimental study on lignite drying characteristics and kinetics. Energy Fuels 2018, 32, 922–935. 10.1021/acs.energyfuels.7b02885. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chandramohan V. P. Influence of air flow velocity and temperature on drying parameters: An experimental analysis with drying correlations. IOP Conf. Ser.: Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 377, 012197. 10.1088/1757-899x/377/1/012197. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng C.; Duan C.; Zhao Y.; Zhang P.; Dong L. Separation and upgrading of fine lignite in a pulsed fluidized bed. 2. experimental study on lignite separation characteristics and improvement of separation efficiency. Energy Fuels 2018, 32, 936–953. 10.1021/acs.energyfuels.7b02941. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Donahue C. J.; Rais E. A. Proximate analysis of coal. J. Chem. Educ. 2009, 86, 222. 10.1021/ed086p222. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vlasov V. A. Modeling of evaporation and condensation processes: a chemical kinetics approach. Heat Mass Tran. 2019, 55, 1661–1669. 10.1007/s00231-018-02549-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kolasinski K. W.Surface Science: Foundations of Catalysis and Nanoscience; John Wiley & Sons, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Buck A.Buck Research CR-1A User’s Manual; Buck Research Instruments, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Lide D. R.CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics; CRC press, 2004; Vol. 85. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen J.; Bastien C.. Nonlinear Optimization of Vehicle Safety Structures; Butterworth-Heinemann, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Arora J. S.Introduction to Optimum Design, 3rd ed.; Academic Press, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wu X.; Leung D. Y. C. Optimization of biodiesel production from camelina oil using orthogonal experiment. Appl. Energy 2011, 88, 3615–3624. 10.1016/j.apenergy.2011.04.041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]