Abstract

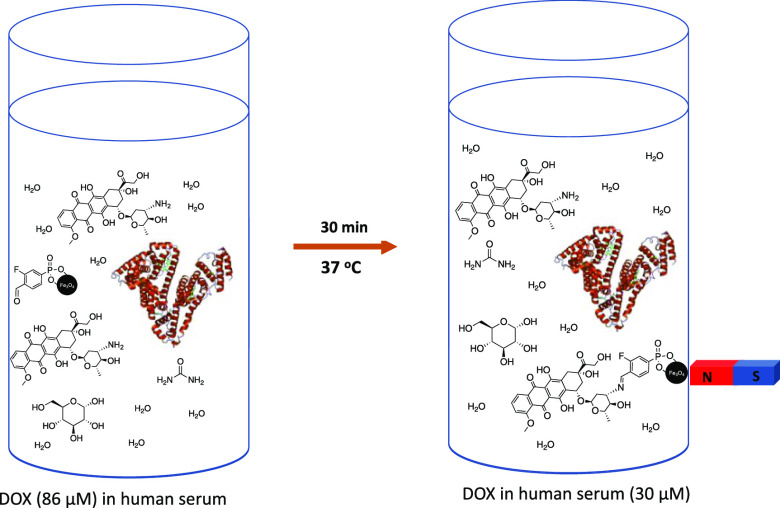

Drug capture is a promising technique to prevent off-target chemotherapeutic agents from reaching systemic circulation and causing severe side effects. The current work examines the viability of using immobilized aldehydes for drug-capture applications via Schiff base formation between doxorubicin (DOX) and aldehydes. Commercially available pyridoxal-5′-phosphate (VB6) was immobilized on iron oxide nanoparticles (IONPs) to capture DOX from human serum. Leaching of VB6 persisted as a primary issue and thus various aldehydes with anchoring groups such as catechol, silatrane, and phosphonate esters have been studied. The phosphonate group-based anchor was the most stable and used for further capture studies. To improve the hydrophilic nature of the aldehydes, sulfonate-containing aldehydes and polyethylene glycols (PEGs) were investigated. Finally, the optimized functionalized iron oxide particles, PEGylated-IONP, were used to demonstrate doxorubicin capture from human serum at biologically relevant temperature (37 °C), time (30 min), and concentrations (μM). The current study sets the stage for the development of potential compact dimension capture device based on surface-anchorable polymers with aldehyde groups.

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)1 is the third leading cause of mortality from cancer globally.2 Although transplantation is the lone curative procedure for HCC, only 30% of the patients qualify.3,4 The rest of the cases have to undergo systemic5 or intra-arterial6 therapies instead. State-of-the-art treatments such as trans-arterial chemoembolization (TACE), in which the chemotherapeutic agents are administered via a catheter close to the tumor,7 have been shown to improve the survival rate of patients because of the improved dose regiment.8 However, 50–75% of the drug delivered to the cancer using these techniques still passes through the tumor, entering systemic circulation and resulting in severe side effects.9 Furthermore, for common drugs such as doxorubicin (DOX), there is a clinical limit on the cumulative dose that can be administered because of the high potential for it to cause irreversible cardiac failure at cumulative doses exceeding 360 mg.10 In order to improve doses and prevent the off-target chemotherapeutic agents from causing side effects, drug-capture materials and techniques are currently being studied.11−13 So far, DOX capture by adsorption on activated charcoal,14 electrostatic attraction to anionic polystyrene sulfonate resins,11,15 and intercalation with genomic DNA16 have been explored.

Iron oxide magnetic particles are widely used for drug delivery and are generally considered safe for human use.17 Previously, we have shown that genomic DNA-functionalized magnetic particles can be used as a drug-filtering platform. The particles were readily decorated on static rare-earth magnets and directed to desired locations using interventional radiology techniques to capture DOX in an animal model.16 Although DNA-based materials have been shown to have higher rates of capture compared to ion-exchange resins, a key concern with DNA-based materials is the possible DNA fragmentation and unknown effects of foreign DNA in the body.18,19 Therefore, development of drug filters with biologically benign materials is crucial for the success of these drug-filtering materials.

In our quest to find an alternative drug-capture material, we examined the chemical reactions that DOX participated in and the known modes of cytotoxicity of DOX. One of the modes of action that stood out was the cross-linking of amino groups of DNA bases in the presence of cellular formaldehyde and DOX by forming DNA-HN-CH2-NH-DOX linkage (Figure 1).20 Further review of the literature showed encouraging examples of imine formation in aqueous medium and their high stability. For example, imine formed from DOX-NH2 in a pH-induced drug-release experiment showed reasonable stability at pH 7.4, only releasing less than 10% of DOX even after 96 h.21,22 In addition, several aldehydes have been reported to have a large equilibrium constant in water for Schiff base formation even with less-reactive aniline.23 Finally, aldehyde-containing compounds such as pyridoxal-5′-phosphate (VB6) and 5-formyl-2-furansulfonic acid have been identified to react with aminoglycoside Kanamycin A, an analogous moiety in DOX, in aqueous media to form 100% imine.24 Encouraged by these precedents, we considered evaluating Schiff base formation between immobilized aldehydes and DOX for drug-capture applications.

Figure 1.

DNA cross-linking by DOX in the presence of cellular formaldehyde.16

Results and Discussion

In a preliminary 1H NMR experiment (Figure S1), a mixture of VB6 and doxorubicin hydrochloride in D2O confirmed the formation of imine (1) in 5 min (Scheme 1). However, a significant amount of aldehyde existed as a hydrate.

Scheme 1. Imine Formation between Doxorubicin Hydrochloride and Pyridoxal-5′-phosphate in D2O.

Because phosphate groups have been utilized for immobilizing organic compounds on inorganic supports,25 we decided to directly immobilize VB6 on the surface of iron oxide nanoparticles (IONPs) and use them (IONP-VB6) for drug-capture applications. The particles were prepared by treating them in a solution of VB6 under various loading and washing conditions (Table S1). The initial capture experiments were carried out in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) solution of DOX (0.1 mg/mL) to imitate the physiological pH and ion concentration. The captured DOX was released when the particles were warmed in aqueous acetic acid (Figure S4), further supporting the imine formation. Depending on the loading and washing protocols used, the prepared IONP-VB6 were able to capture 3.4–4.6 mg of DOX from PBS per 100 mg of IONP-VB6 used, with the highest amount of DOX captured with material prepared at 50 °C (entry 2, Table S1). However, in all the tested cases, leaching of VB6 was observed in UV–vis experiments. Furthermore, the order of leaching observed was PBS (37 °C) > PBS (rt) > deionized water (37 °C) > deionized water (rt) based on the UV–vis experiment for constant mass of IONP-VB6 treated under these conditions. Thus, we concluded that the phosphate group was hydrolyzing under these conditions and decided to explore other anchoring groups. Despite this, preliminary experiments with IONP-VB6 in human serum at 37 °C still showed a decrease in the concentration of DOX (Figure S3), which demonstrated that immobilized aldehydes could be used for DOX capture under physiologically relevant conditions.

We decided to pursue simple aldehydes that were soluble in organic solvents for easy chemical modifications and surface loading. First, we treated 3,4-dihydroxy benzaldehyde, a readily available compound, with IONPs at rt for an hour,26 with immobilization expected via the catechol mode of binding.27 Although the IONP-3,4-dihydroxy benzaldehyde readily captured (2.8 mg per 100 mg) DOX from PBS, excessive leaching of the aldehyde was also observed by the UV–vis experiment (Figure S5). Nonetheless, this served as a proof that simple aldehydes on iron oxide surfaces could easily act as capturing materials. Furthermore, aromatic aldehydes were a suitable choice as their electronics and sterics could be easily modified to obtain the desired binding properties. One of the key goals was to find a robust anchoring group that was stable on IONPs under physiological conditions. Because siloxane and phosphonate groups are widely used as anchoring groups for metal oxide surfaces in biomedical applications,27 we synthesized simple aldehydes with silatrane (2) and phosphonate ethyl ester (3) anchoring groups and immobilized them on IONPs (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2. Preparation of IONP-OSi-CHO and IONP-3F4CPP.

Initial DOX-capture experiments using IONP-OSi-CHO (Figure S6) and IONP-3F4CPP (Figure S7) from PBS (0.1 mg/mL) at ambient temperature with mechanical shaking in 30 min showed capture of 3.8 and 4.8 mg of doxorubicin per 100 mg of functionalized IONPs, respectively. However, under similar conditions, both IONP-OSi-CHO and IONP-3F4CPP in PBS in the absence of DOX showed leaching of organics, even though these materials were thoroughly washed with organic solvents and deionized water during their preparation, until no organics could be detected in the washes using UV–vis. Because silatrane and phosphonates are known to bind metal oxide surfaces via various modes, we speculated that the loosely bound phosphonate and siloxane molecules came off under the present conditions. To remove these loosely bound molecules, the materials were first treated with PBS at 45 °C for 3 h and then thoroughly rinsed with PBS, water, and EtOH and dried at ambient temperature under vacuum. Afterward, the samples were used for doxorubicin capture from PBS (0.1 mg/mL) experiments at ambient temperature for 30 min resulted in 3.1 and 4.7 mg of doxorubicin captured per 100 mg of functionalized siloxane and phosphonate IONPs, respectively. Because the capture capacity was significantly reduced for the siloxane-anchored aldehyde after washing, we decided to pursue further studies with the phosphonate-containing aldehyde instead. The capture results of IONP-3F4CPP were consistent with three independent preparations. Similar capture performance was also observed with the 3-fluoro isomer. Because of the small size of the fluorine, we speculated a minimal steric effect and a beneficial electron-withdrawing inductive effect to keep the aldehyde group electron-deficient. Thus, further studies were pursued with the ortho-fluoro isomer. Furthermore, key material based on phosphonate anchors described in the manuscript have been characterized using transition electron microscopy, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) with energy-dispersive X-ray, attenuated total reflection FT-IR, and CHN analysis (Supporting Information, Sections 10, 11, 17, and 18, respectively), which show aggregation of the particles during functionalization, the presence of the carbonyl functional group (Figure S13), and increase in carbon content (0.6–2.5%; Table S2).

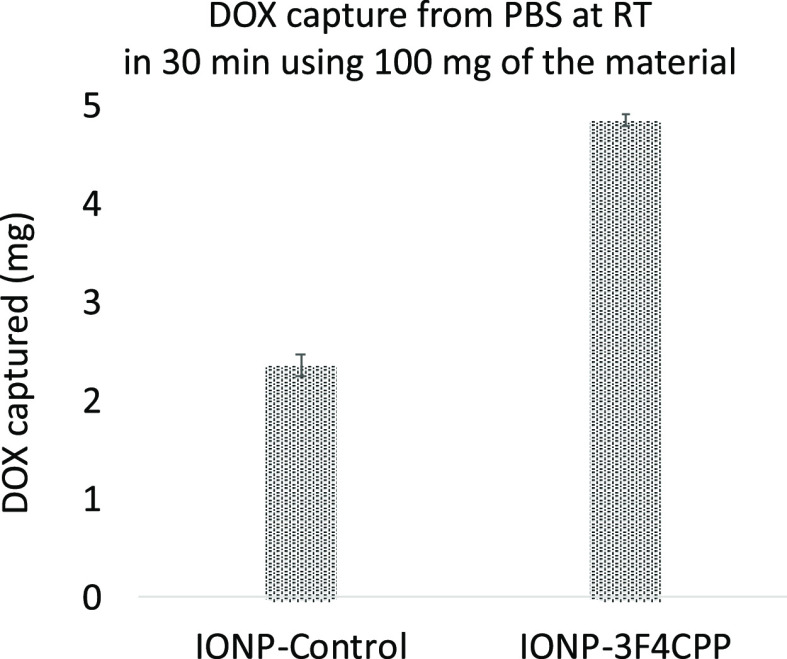

To deconvolute the effects of adsorption from that of imine formation on the amount of drug captured, a control batch of IONPs was treated under the same aldehyde loading conditions but in the absence of the aldehyde. The capture experiment performed with the IONP-Control at ambient temperature in PBS after 30 min resulted in 2.4 mg of doxorubicin capture, almost 50% as that of IONP-3F4CPP (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Capture via adsorption vs imine formation.

The performance of IONP-3F4CPP was then examined in the presence of human serum (HS) to investigate the antagonistic effects that proteins could have on the surface aldehydes, such as unwanted imine formation, or surface adsorption. We studied capture using 100 mg of IONP-3F4CPP at 37 °C in HS for 30 min at clinically relevant DOX concentration (0.05 mg/mL; Table 1 and Figure 3)28 and supraclinical concentrations (0.1 and 0.2 mg/mL).11 The capture amount increased as the concentration of DOX increased: 0.2 > 0.1 > 0.05 mg/mL (Table 1, entry 1–3). Furthermore, the amount captured changed as follows PBS (rt) > PBS (37 °C) > HS (rt) > HS (37 °C). These results show that the capture is directly proportional to the concentration of DOX in solution, which is in line with the Schiff base formation reaction and that binding in HS is significantly lower than that in PBS.

Table 1. DOX Capture from Human Serum at Various Concentrations in 30 min at 37 °Ca.

| entry | DOX conc. mg/mL | total % of DOX captured from 10 mL HS | DOX captured (mg) per 100 mg of IONP |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.05 | 24 | 0.12 |

| 2 | 0.1 | 43 | 0.43 |

| 3 | 0.2 | 53 | 1.06 |

Average of three experiments.

Figure 3.

DOX capture using various functionalized IONPs (100 mg) from human serum (10 mL; 0.05 mg/mL) at 37 °C; average of three experiments; error bars in Figure S15.

We hypothesized that both surface adsorption of protein and competing protein-aldehyde reactions in HS reduced the capture of DOX at low (0.05 mg/mL) concentrations. In order to improve the capture and mitigate the competing reactions with the protein amines, we envisioned that coating the surface with poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) could improve selectivity for capture.29 This approach, known as PEGylation, has been shown to improve the half-life of drug-loaded nanoparticles in blood by avoiding nonspecific protein binding and subsequent clearance by macrophages and monocytes.30 Furthermore, PEGylation would also improve the wettability of the functionalized IONPs, as the PEG macromolecules are hydrophilic. In our case, we hypothesized that the PEGs could sterically prevent proteins from interacting with the surface aldehydes, only allowing the small-molecule doxorubicin to approach the surface. As noncovalent-type PEGylation has been studied,31 thus, we started by simply exposing the IONP-3F4CPP to methoxypolyethylene glycols (mPEGs) with various molecular weights to PEGylate the surface. The resulting particles were then tested for DOX capture in HS at 37 °C for 30 min. The results showed that there was an overall increase in the amount of drug captured compared to the non-PEGylated IONP-3F4CPP. It was determined that the amount of doxorubicin captured with respect to the molecular weight of PEG used was mPEG-550 > mPEG-750 > mPEG-200 > no PEG > mPEG-2000 (Figure S12). This was attributed to the higher wettability of the functionalized IONPs and the prevention of protein adsorption. To increase the stability of PEG via covalent binding, a phosphonate-modified tetraethylene glycol (4) was coloaded (10 mol %) with the aldehyde on IONPs to obtain IONP-3F4CPP-PEG-Cl (Scheme 3), which resulted in similar capture (Figure 3) as that of the mPEG-550-exposed material. When the amount of IONP-3F4CPP-PEG-Cl was doubled (200 mg), a further decrease in the DOX concentration was observed (Figure 3).

Scheme 3. Preparation of IONP-3F4CPP-PEG-Cl.

In order to further increase the capture capacity of the particles, we decided to install both sulfonate and aldehyde groups because sulfonated resins have demonstrated the ability to capture DOX.11,12 In addition, we also hypothesized that the hydrophilic nature of the particle could help improve the rate of capture. The fluorine on the parent aldehyde 3 was readily replaced with a sulfonate side chain by fluoride displacement and loaded on the IONPs (Scheme 4). The resulting product (IONP-BiFun) was tested for DOX capture under representative conditions. To our surprise, there was no significant improvement in the amount of DOX captured in PBS. However, the amount captured from human serum was on par with that of the IONP-PEG-550. Thus, we debated if the improvement stemmed primarily from the hydrophilic nature of the material. In order to test if the improvement solely arrived from the hydrophilic nature of these modifications, the IONP-3F4CPP, IONP-3F4CPP-mPEG-550, and IONP-BiFun (100 mg each) were exposed to HS (10 mL each) at 37 °C for 30 min in the absence of DOX and subjected to similar washing and drying steps before being examined by CHN analysis. Comparison of the nitrogen content (0.7%) indicated that there was no significant difference between them. Furthermore, they were tested for their DOX capture capacity from PBS (0.1 mg/mL) at ambient temperature and showed very similar capture (∼3.1 mg per 100 mg of the material) capacity, retaining 65% of its original ability. Therefore, the improved capture exhibited by IONP-3FCPP-mPEG-550 and IONP-BiFun likely stemmed from the hydrophilicity imparted by the mPEG-550 and the sulfonate group.

Scheme 4. Preparation of IONP-BiFun.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we demonstrated that aldehyde-functionalized magnetic particles were able to capture doxorubicin via Schiff base formation, from biologically relevant concentrations and temperature from human serum. PEGylation and sulfonation of the IONPs also appeared to improve the drug capture in human serum. Such aldehyde-functionalized particles could also be extended to capture other drugs with amino groups (−NH2 and −NHR), such as daunorubicin, epirubicin, and idarubicin. Ongoing efforts are directed toward precisely designing polymers with solubilizing spacers, aldehyde moieties, and stable anchoring groups that can be used to reduce the amount of solid support needed, which will be convenient to be used as devices in in vitro flow models as well as in animal studies. This present work can also be easily extended to any metal oxide surfaces as the anchoring groups used in this study are also commonly employed to functionalize the surface of several metal oxides. For example, biomedical devices made of stainless steel and nitinol can be readily functionalized using this technique. Moreover, the material developed could have applications beyond off-target chemotherapy in areas such as dynamic combinatorial chemistry32 and protein-33 and microorganism-capture34 applications.

Materials and Instruments

Commercially available substrates were used as received. Reaction progress was monitored by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) using E. Merck silica gel 60 F254 precoated plates (0.25 mm) and visualized by UV fluorescence quenching, potassium permanganate. Silicycle SiliaFlash P60 Academic Silica gel (particle size 0.040–0.063 mm) was used for flash chromatography. 1H and 13C NMR spectra were recorded on a Varian Inova 500 spectrometer (500 and 126 MHz, respectively), a Bruker AV III HD spectrometer equipped with a Prodigy liquid nitrogen temperature cryoprobe (400 and 101 MHz, respectively), or a Varian Mercury 300 spectrometer (300 and 75 MHz, respectively) and are reported in terms of chemical shift relative to residual CHCl3 (7.26 and 77.16 ppm, respectively). Phosphorus chemical shift was referenced to H3PO4 (0.0 ppm). 13C in D2O was referenced to MeOH (49.5). Data for 1H NMR spectra are reported as follows: chemical shift (δ ppm) (multiplicity, coupling constant (Hz), integration). High-resolution mass spectra (HRMS) were acquired from the Caltech Mass Spectral Facility using fast-atom bombardment (FAB+), electrospray ionization (TOF ES+), or electron impact (EI+). Fluorescence measurements were performed using a 96-well plate on a Molecular Devices FlexStation 3 Multimode microplate reader. SEM and EDS measurements were performed on a Zeiss 1550VP field emission SEM equipped with an Oxford EDS module. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) measurements were performed on an FEI TF30ST transmission electron microscope at Caltech TEM facility. Infrared measurements were performed on a Nicolet iS50 Fourier transform infrared spectrometer equipped with a DuraScope ATR unit. C, H, and N analyses were carried out using a PerkinElmer 2400 Series II CHN elemental analyzer. Unless otherwise stated, reactions were carried out on the bench. Fe3O4 (30 nm APS, 99%) was purchased from Nanostructured & Amorphous Materials, Inc. Human serum was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (Hypo-Opticlear Human Sera). DOX was purchased from LC Labs. All reagents not otherwise mentioned were purchased from Sigma Aldrich and were used without further purification.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support from the NIH (R01CA194533). The authors also would like to thank Prof. Steven Hetts and Prof. Anand Patel for their valuable feedback throughout the project, Dr. Daryl Yee, Dr. William Wolf, and Dr. Jeong Hoon Ko for proofreading the manuscript, and Dr. Christopher Marotta for proof reading and helping with TEM experiments. The authors also acknowledge the support from the Beckman Institute of the California Institute of Technology for the use of the Molecular Materials Research Center.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.0c03840.

Imine formation in D2O (1H NMR), preparation of IONP-VB6, DOX capture (UV–Vis) from PBS using IONP-VB6, DOX capture from human serum IONP-VB6-RT (emission spectrum), release of DOX in aq. acid from IONP-VB6, preparation of IONP-3,4-dihydroxybenzaldehyde, and DOX capture (UV–vis), preparation of IONP-OSi-CHO and DOX capture (UV–vis), preparation of diethyl (3-fluoro-4-formylphenyl)phosphonate, preparation of IONP-3F4CPP and DOX capture (UV–vis), SEM of IONP-commercial, IONP-3F4CPP, and IONP-3F4CPP-HS, TEM of IONP-3F4CPP, preparation of PEGylated IONP-3F4CPP, DOX capture profile from human serum (PEGylated vs non-PEGylated), preparation of IONP-BiFun, synthesis of diethyl (2-(2-(2-(2-chloroethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethyl)phosphonate, preparation of IONP-3F4CPP-PEG-Cl, ATR-IR spectra, CHN analysis, DOX capture profile with error bars, and NMR spectra (PDF)

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): A provisional patent application has been filed by the technology transfer office of the California Institute of Technology on 3/19/2019.

Supplementary Material

References

- Balogh J.; Victor D. 3rd; Asham E. H.; Burroughs S. G.; Boktour M.; Saharia A.; Li X.; Ghobrial M.; Monsour H. Jr Hepatocellular carcinoma: a review. J. Hepatocell. Carcinoma 2016, 3, 41–53. 10.2147/jhc.s61146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray F.; Ferlay J.; Soerjomataram I.; Siegel R. L.; Torre L. A.; Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. Ca - Cancer J. Clin. 2018, 68, 394–424. 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llovet J. M.; Schwartz M.; Mazzaferro V. Resection and liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin. Liver Dis. 2005, 25, 181–200. 10.1055/s-2005-871198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abulkhir A.; Limongelli P.; Healey A. J.; Damrah O.; Tait P.; Jackson J.; Habib N.; Jiao L. R. Preoperative Portal Vein Embolization for Major Liver Resection. Ann. Surg. 2008, 247, 49–57. 10.1097/sla.0b013e31815f6e5b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinter M.; Peck-Radosavljevic M. Review article: systemic treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2018, 48, 598–609. 10.1111/apt.14913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crocetti L.; Bargellini I.; Cioni R. Loco-regional treatment of HCC: current status. Clin. Radiol. 2017, 72, 626–635. 10.1016/j.crad.2017.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raoul J.-L.; Forner A.; Bolondi L.; Cheung T. T.; Kloeckner R.; de Baere T. Updated use of TACE for hepatocellular carcinoma treatment: How and when to use it based on clinical evidence. Canc. Treat Rev. 2019, 72, 28–36. 10.1016/j.ctrv.2018.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llovet J. M.; Real M. I.; Montaña X.; Planas R.; Coll S.; Aponte J.; Ayuso C.; Sala M.; Muchart J.; Solà R.; Rodés J.; Bruix J. Arterial embolisation or chemoembolisation versus symptomatic treatment in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2002, 359, 1734–1739. 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)08649-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwu W. J.; Salem R. R.; Pollak J.; Rosenblatt M.; D’Andrea E.; Leffert J. J.; Faraone S.; Marsh J. C.; Pizzorno G. A clinical-pharmacological evaluation of percutaneous isolated hepatic infusion of doxorubicin in patients with unresectable liver tumors. Oncol. Res. 1999, 11, 529–537. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buijs M.; Vossen J. A.; Frangakis C.; Hong K.; Georgiades C. S.; Chen Y.; Liapi E.; Geschwind J.-F. H. Nonresectable Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Long-term Toxicity in Patients Treated with Transarterial Chemoembolization-Single-Center Experience. Radiology 2008, 249, 346–354. 10.1148/radiol.2483071902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel A. S.; Saeed M.; Yee E. J.; Yang J.; Lam G. J.; Losey A. D.; Lillaney P. V.; Thorne B.; Chin A. K.; Malik S.; Wilson M. W.; Chen X. C.; Balsara N. P.; Hetts S. W. Development and Validation of Endovascular Chemotherapy Filter Device for Removing High-Dose Doxorubicin: Preclinical Study. J. Med. Dev. 2014, 8, 0410081–0410088. 10.1115/1.4027444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X. C.; Oh H. J.; Yu J. F.; Yang J. K.; Petzetakis N.; Patel A. S.; Hetts S. W.; Balsara N. P. Block Copolymer Membranes for Efficient Capture of a Chemotherapy Drug. ACS Macro Lett. 2016, 5, 936–941. 10.1021/acsmacrolett.6b00459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aboian M. S.; Yu J. F.; Gautam A.; Sze C. H.; Yang J. K.; Chan J.; Lillaney P. V.; Jordan C. D.; Oh H. J.; Wilson D. M.; Patel A. S.; Wilson M. W.; Hetts S. W. In vitro clearance of doxorubicin with a DNA-based filtration device designed for intravascular use with intra-arterial chemotherapy. Biomed. Microdevices 2016, 18, 98. 10.1007/s10544-016-0124-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curley S. A.; Byrd D. R.; Newman R. A.; Ellis H. J.; Chase J.; Carrasco C. H.; Cleary K.; Bodden W.; Hohn D. C. Reduction of systemic drug exposure after hepatic arterial infusion of doxorubicin with complete hepatic venous isolation and extracorporeal chemofiltration. Surgery 1993, 114, 579–585. 10.5555/uri:pii:003960609390297Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh H. J.; Aboian M. S.; Yi M. Y. J.; Maslyn J. A.; Loo W. S.; Jiang X.; Parkinson D. Y.; Wilson M. W.; Moore T.; Yee C. R.; Robbins G. R.; Barth F. M.; DeSimone J. M.; Hetts S. W.; Balsara N. P. 3D Printed Absorber for Capturing Chemotherapy Drugs before They Spread through the Body. ACS Cent. Sci. 2019, 5, 419–427. 10.1021/acscentsci.8b00700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumenfeld C. M.; Schulz M. D.; Aboian M. S.; Wilson M. W.; Moore T.; Hetts S. W.; Grubbs R. H. Drug capture materials based on genomic DNA-functionalized magnetic nanoparticles. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2870. 10.1038/s41467-018-05305-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arias L.; Pessan J.; Vieira A.; Lima T.; Delbem A.; Monteiro D. Iron Oxide Nanoparticles for Biomedical Applications: A Perspective on Synthesis, Drugs, Antimicrobial Activity, and Toxicity. Antibiotics 2018, 7, 46. 10.3390/antibiotics7020046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai Y.; Tong Y.; Liu Y.; Hu H. Self-dsDNA in the pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2018, 191, 1–10. 10.1111/cei.13041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L.; Yang D.; Yang Q.; Cheng F.; Huang Y. Extracellular DNA in blood products and its potential effects on transfusion. Biosci. Rep. 2020, 40, BSR20192770. 10.1042/bsr20192770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutts S.; Nudelman A.; Rephaeli A.; Phillips D. The power and potential of doxorubicin-DNA adducts. IUBMB Life 2005, 57, 73–81. 10.1080/15216540500079093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao Y.; Liu S.; Zhang Y.; Chi Z.; Xu J. A pH-responsive polymer based on dynamic imine bonds as a drug delivery material with pseudo target release behavior. Polym. Chem. 2018, 9, 878–884. 10.1039/c7py02108a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma G.; Shetake N. G.; Barick K. C.; Pandey B. N.; Hassan P. A.; Priyadarsini K. I. Covalent immobilization of doxorubicin in glycine functionalized hydroxyapatite nanoparticles for pH-responsive release. New J. Chem. 2018, 42, 6283–6292. 10.1039/c7nj04706a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Godoy-Alcántar C.; Yatsimirsky A. K.; Lehn J.-M. Structure-stability correlations for imine formation in aqueous solution. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 2005, 18, 979–985. 10.1002/poc.941. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fuentes-Martínez Y.; Godoy-Alcántar C.; Medrano F.; Dikiy A.; Kanamycin A. Kanamycin A: imine formation in aqueous solution. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 2012, 25, 1395–1403. 10.1002/poc.3057. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gnauck M.; Jaehne E.; Blaettler T.; Tosatti S.; Textor M.; Adler H.-J. P. Carboxy-Terminated Oligo(ethylene glycol)–Alkane Phosphate: Synthesis and Self-Assembly on Titanium Oxide Surfaces. Langmuir 2007, 23, 377–381. 10.1021/la0606648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tulevski G. S.; Miao Q.; Fukuto M.; Abram R.; Ocko B.; Pindak R.; Steigerwald M. L.; Kagan C. R.; Nuckolls C. Attaching organic semiconductors to gate oxides: in situ assembly of monolayer field effect transistors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 15048–15050. 10.1021/ja044101z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pujari S. P.; Scheres L.; Marcelis A. T. M.; Zuilhof H. Covalent surface modification of oxide surfaces. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 6322–6356. 10.1002/anie.201306709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lammer J.; Malagari K.; Vogl T.; Pilleul F.; Denys A.; Watkinson A.; Pitton M.; Sergent G.; Pfammatter T.; Terraz S.; Benhamou Y.; Avajon Y.; Gruenberger T.; Pomoni M.; Langenberger H.; Schuchmann M.; Dumortier J.; Mueller C.; Chevallier P.; Lencioni R. Prospective randomized study of doxorubicin-eluting-bead embolization in the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma: results of the PRECISION V study. Cardiovasc. Intervent. Radiol. 2010, 33, 41–52. 10.1007/s00270-009-9711-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suk J. S.; Xu Q.; Kim N.; Hanes J.; Ensign L. M. PEGylation as a strategy for improving nanoparticle-based drug and gene delivery. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2016, 99, 28–51. 10.1016/j.addr.2015.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jokerst J. V.; Lobovkina T.; Zare R. N.; Gambhir S. S. Nanoparticle PEGylation for imaging and therapy. Nanomedicine 2011, 6, 715–728. 10.2217/nnm.11.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prabhu S.; Mutalik S.; Rai S.; Udupa N.; Rao B. S. S. PEGylation of superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticle for drug delivery applications with decreased toxicity: an in vivo study. J. Nanopart. Res. 2015, 17, 412. 10.1007/s11051-015-3216-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Han Y.; Nowak P.; Colomb-Delsuc M.; Leal M. P.; Otto S. Instructable Nanoparticles Using Dynamic Combinatorial Chemistry. Langmuir 2015, 31, 12658–12663. 10.1021/acs.langmuir.5b03673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safarik I.; Safarikova M. Magnetic techniques for the isolation and purification of proteins and peptides. Biomagn. Res. Technol. 2004, 2, 7. 10.1186/1477-044x-2-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plouffe B. D.; Murthy S. K.; Lewis L. H. Fundamentals and application of magnetic particles in cell isolation and enrichment: a review. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2015, 78, 016601. 10.1088/0034-4885/78/1/016601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.