Abstract

The global pandemic of coronavirus 2019 (COVID‐19) caused by coronavirus has had a profound impact on the delivery of health care in the United States and globally. Boston was among the earliest hit cities in the United States, and within Boston, the Massachusetts General Hospital provided care for more patients with COVID‐19 than any other hospital in the region. This necessitated a massive reallocation of resources and priorities, with a near doubling of intensive care bed capacity and a halt in all deferrable surgical cases. During this crisis, the Division of Cardiac Surgery responded in a unified manner, dealing honestly with the necessity to reduce Intensive Care Unit resource utilization for the benefit of both the institution and our community by deferring nonemergent cases while also continuing to efficiently care for those patients in urgent or emergent need of surgery. Many of the interventions that we instituted have continued to support teamwork as we adapt to the remarkably fluid changes in resource availability during the recovery phase. We believe that the culture of our division and the structure of our practice facilitated our ability to contribute to the mission of our hospital to support the community in this crisis, and now to its recovery. We describe here the challenge we faced in Boston and some of the details of the structure and function of our division.

Keywords: clinical review, COVID-19, culture, teamwork

1. COVID‐19 AT MGH

The first case of coronavirus 2019 (COVID‐19) was admitted to the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) on March 2, 2020. Between March 2nd and June 22nd, 1687 COVID‐positive patients were cared for at the MGH, including 514 in the expanded intensive care units (ICU). An additional 4062 patients were considered at‐risk for COVID‐19, requiring enhanced resources during portions of their care. At the peak of the pandemic in Boston, which lasted about 2 weeks during the weeks of April 13th and April 20th, there was a daily census of more than 300 inpatients at MGH with a confirmed diagnosis of COVID‐19, with approximately half of them in the ICUs. On March 11th, the Hospital Incident Command System, a structure established in the aftermath of the Marathon Bombing, directed us to review our upcoming surgical cases and defer all those that were not truly emergent. This proactive action by the MGH predated the March 15th order by the Massachusetts Department of Public Health to postpone or cancel any nonessential procedures. As the staff and resources were redeployed from the operating rooms (ORs) and perioperative areas to the intensive care units to care for patients with COVID‐19, the cardiac ORs were required to “ramp‐down” to 1–3 cases per day by March 23rd to keep resources available for the COVID surge. Accordingly, only patients with conditions such as coronary artery disease with unstable angina pectoris or critical left main stenosis, highly symptomatic aortic stenosis or aortic aneurysms exceeding 6 cm diameter remained on the OR schedule. 1

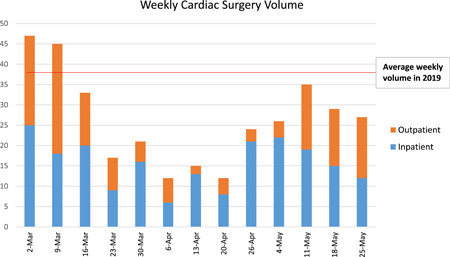

The impact of the virtual halt on cases on the division was profound. The annual surgical case volume of the division has been rising annually, to approximately 2000 cases in 2019, for an average volume of approximately 165 cases/month. At our nadir during the month of April, when the institution and city experienced the peak of the surge, our volume fell to 63 total cases for the month, 74% of which were urgent or emergent. In subsequent months, as we continued to care for a large number of patients with COVID‐19, but regained some capacity and staffing, our volume climbed to 121 cases in May and 151 cases in June. At the time of writing this manuscript, we are functioning at approximately 80% of our maximum capacity, and hope to return to full productivity in the coming weeks (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Weekly cardiac surgery case volumes and the impact of the COVID‐19 infection at MGH (compared with 2019). COVID‐19, coronavirus 2019; MGH, Massachusetts General Hospital

2. MGH CARDIAC SURGERY: NOT A “DIVISION” BUT A “UNIT”

The clinical operations of the cardiac surgery division at MGH are supported by eight clinically active surgeons addressing the full spectrum of cardiac disease, and two surgeons specializing in organ procurement and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO). The practice is supported by 45 inpatient and outpatient advanced practice providers and eight administrative staff. The guiding principles of our practice are

-

1.

the needs of the patient come first,

-

2.

we will contribute to the specialty via education and research, and

-

3.

the success of the individual depends on the success of the group, and the success of the group depends on the success of each individual.

Of these, there is likely little controversy over the first two, which represent universal values for all cardiac surgeons in the academic setting. The third, however, is more complex. Some units celebrate the team over the individual, a philosophy that leverages collective effort, but can discourage the power of individual drive and creativity. The result can be a smothering sense of uniformity and interchangeability—a “Stepford” practice. More common, in our experience, is a unit representing a collection of surgeons conveniently colocated physically and sharing institutional infrastructure and common expenses, but essentially running independent practices, energized by a personal drive to succeed and often competing with each other, either overtly or in a subtle manner—the “thousand flowers blooming” practice. We have made an unapologetic effort to capture the best of both paradigms—“to have our cake and eat it too” as Hartzell Schaff is fond of saying. Accordingly, as individuals have been added to the staff, we explicitly enunciate the value we place on teamwork making it clear that if this is not the sort of practice they want to join, then they should not do so. Furthermore, while trying to remain open to individuals exploring the field and finding their passion, we have sought out individuals strategically with specific skill sets and diverse clinical interests rather than using a “hire the best athlete” approach. We feel this minimizes the potentially counterproductive forces, from a teamwork perspective, of competition over the same clinical and academic “turf” and refocus it on how productive each member of the team can be in their subspecialty area.

The culture of teamwork is reinforced by explicit processes and procedures established with the intent of supporting a sense of shared responsibility for shared resources. This starts with equally shared OR block time among all members of the division from the newest hire to the most senior surgeon, giving everyone a chance to build a practice. This equally shared initial allocation, rather than a “first come, first booked approach,” prevents the “rich getting richer and the poor getting poorer” phenomenon. There is a defined “release time” to avoid leaving ORs unused, accommodating add‐on and urgent cases, and clear communication among surgeons is encouraged. This is reinforced by a brief (generally less than 5 min) telephone/zoom “OR Huddle” at 6:45 each day including all the surgeons on staff as well as OR nursing and anesthesia, a practice initiated during the ramp‐up as noted below.

Our OR time is organized with the expectation of two cases per room each day. These “slots” are allocated each day as “first starts” and “to‐follow” without committing to the location of the to‐follow case. This means that a surgeon does not “own” the room to which his or her cases are assigned at the beginning of the day. Second cases for the day are placed in ORs under the direction of the anesthesia and nursing staff based on anticipated case duration and available staffing to optimize the schedule for everyone, with the aim being to get all cases done during prime time, if possible. Accordingly, a given surgeon with two short cases will not necessarily follow themselves, but may instead be followed in that room by another surgeon with a long case, while their second short case is placed in another room following a longer case. While this may mean that the interval between cases will be prolonged on that operating day for the individual with two short cases, on another day when they have two long cases they will get the same benefit and in the end, we hope everyone gets home for dinner.

Before COVID, both outpatient and inpatient referrals to the practice were encouraged to flow via a centralized referral coordinator who has access to the clinic schedule and OR availability for all surgeons. The referral coordinator facilitated directed consultations for a specific surgeon if requested but also provided information regarding the other surgeons who may have earlier clinic availability or open OR capacity. This leaves the decision‐making in the hands of the patient or the referring doctor to request a consultation with a specific surgeon if they have a strong preference or to meet with another surgeon if they prefer an earlier appointment. This mechanism supports the practice growth of all members of the division, improves overall access by reducing outpatient wait times for clinic appointments, and decreases the preoperative length of stay for inpatients while optimizing OR utilization. Furthermore, for inpatients, this has led to the creation of a shared consult list that is circulated to all surgeons by email each day. This leads to transparency in the process and fosters mutual trust (“trust but verify”). While some inpatient referrals which are particularly high risk due to their acute nature are staffed by the on‐call surgeon to ensure even distribution, more common procedures are generally directed to those with the first open OR availability, provided the referring physician and the patient agree. This has created a sense of shared responsibility to provide care for these patients. By blending transparency around capacity with respect for the requests of referring providers, individual surgeons are still free to develop personal relationships and encouraged to cultivate outside referral practices. This approach has improved our OR utilization and has enabled us to increase our surgical volume by over 50% over a course of 4 years, without any concomitant increase in OR resources.

A sense of shared responsibility for outcomes is endorsed by an unblinded review of mortality and morbidity data, including Variable Life Adjusted Display curves for all STS risk modeled procedures. High‐risk patients are routinely discussed at Heart Team meetings not only with our cardiology colleagues but also among surgeons within the division to come to a collective decision so that no single surgeon feels pressured. If there is a difference of opinion between the referring cardiologist, or a second opinion is requested, we make every effort to manage that referral internally from surgeon to surgeon in a transparent way that discourages "doctor shopping" and preserves harmony among the surgeons. All matters of concern are openly discussed at the weekly division meeting attended by the surgeons. These may include division finance, resident education, ICU protocols, upcoming clinical trials, and so forth. Periodically, the division will coordinate dinner for all the surgeons and their spouses at a local restaurant without reference to a specific event or a holiday, but with the aim of increasing familiarity and strengthening the personal relationships that are critical to team building.

The surgeon compensation plan is fundamentally based on Relative Value Units (RVUs) to neutralize the impact of differences in payor mix. This has made the individual profit–loss statements/calculations irrelevant to the surgeons. While there is a risk of competition for RVU generating cases, the positive impact of increased overall case volume has largely kept this in check, and surgeons who receive inpatient consults that they cannot expeditiously accommodate, routinely internally refer to them other surgeons provided the patient, and referring cardiologist agree. Annual bonus payments are based on the overall margin generated by the group as a whole rather than by each individual surgeon, thus rewarding collective success with collective financial benefit.

3. GOOD TEAMS BEAT GREAT PLAYERS: HOW OUR CULTURE FACILITATED OUR RESPONSE TO COVID‐19

The sense of cohesion, mutual trust and teamwork that we established over the course of years served us well when confronting the challenges confronting the division and the institution in the face of the pandemic. When the institution asked us to discontinue all deferable cases, the division functioned as a coherent unit, applying uniform ground rules within each surgeon's practice without concern for favoritism or inequity. While in normal times, a distributed decision‐making structure allows each surgeon to be fundamentally responsible for the management of a patient on their service and the scheduling of cases within their OR slot, during this crisis we moved easily to a centralized command and control mode of function. As our OR capacity was drastically reduced, there was an acute need to prioritize care for those that required it most urgently. With the resources only allowing one elective and one urgent/emergent case per day, individual allocation of OR slots was abolished. Inpatients requiring urgent care were referred under central control to surgeons on a largely rotating basis to “keep all hands busy.” The on‐call surgeon for the day was “protected” from the scheduled cases to keep them available for emergencies. We believe that the “bank account” of trust built over preceding years made this possible without complaint.

Again, with a focus on transparency in decision‐making, we instituted a weekly Zoom meeting to discuss outpatient cases listed for the OR the following week. In addition to the surgeons, the leadership from cardiac anesthesia, OR nursing, perfusion, and critical care were invited to attend. Each surgeon was asked to present patients from their practice that they felt could not be deferred. These cases were reviewed and prioritized collectively by the whole team. While the division chief assumed the final authority to break an impasse, this was rarely required. When the cases were triaged, the discussion focused on the patient and not on the operating surgeon (Rule 1: the needs of the patient come first). This collective and transparent decision‐making provided a sense of comfort (and security) for the surgeon whose case was deferred. Deferred patients were frequently contacted by our clinic advanced practice providers to monitor changes in clinical status. Furthermore, such open and multidisciplinary discussion of the surgical schedule ensured confidence in responsible decision‐making by the surgeons and a sense of teamwork among members of the OR staff, all of whom were placed in a position of vulnerability to coronavirus infection at a time when testing for COVID‐19 was cumbersome, if available at all. We think that this collective involvement of all teams in this process prevented conflict and frustration, provided a common sense of purpose and boosted morale, all of which allowed us to “keep on keepin on” at MGH (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Legend: Keeping the lights on during the pandemic—MGH cardiac surgery team with representatives from surgery, OR nursing and perfusion teams. MGH, Massachusetts General Hospital; OR, operating room. Courtesy: Samantha Marinelli, BSN, RN

During the recovery phase, as the ORs and the ICUs began to come back on line, and the nursing and critical care staff were repatriated to their home units, transparency within the division, especially among the surgeons, has been a key principal. A single amalgamated waitlist of pending outpatient cases for all surgeons was assembled by our clinic advanced practice providers, and made accessible to all surgeons and advanced practice providers on a shared drive. Each surgeon was asked to prioritize the patients within their own practice, based on clinical urgency. These patients were then collectively discussed via teleconference where the surgeons were asked explain the basis of that prioritization to the group, so that all had confidence in the fairness of resource distribution. As can be imagined, different surgeon practices were affected differently, for example, while during the ramp‐down, CABGs for critical CAD and critical aortic stenosis patients were prioritized, most elective mitral valve repairs were deferred. This resulted in varying numbers of waitlist patients among surgeons. As the OR resources increased, we instituted weekly Zoom calls with the surgical staff to discuss room allocation for the surgeons based on their individual deferral lists to work through the backlog as efficiently possible. It was a great display of teamwork when the surgeons with long waitlists volunteered to defer new consults till they could clear their queue, which allowed the surgeons with shorter waitlists to take on a greater proportion of new referrals, resulting in an even distribution of resources.

4. ALL FOR ONE AND ONE FOR ALL: HOW HAS THE CRISIS MADE US STRONGER?

The necessity of social distancing during the pandemic has actually brought us closer. The rapid acceptance and integration of video teleconferencing into our lives has made our communication more fluid. Since physical location has become less important, the attendance at our resident didactic sessions has increased. In addition, teleconferencing provided us with the ability to record and archive those lectures. Monthly multidisciplinary team meetings to discuss patients with endocarditis have now been supplemented with ad hoc zoom case discussions, expediting decision‐making for these complex patients. These are things that we had desired for before the pandemic, but never figured out how to achieve, till the solutions were “thrust upon us.” Our clinics have become “smart,” with many initial patient visits with the surgeon being performed remotely via video or telephone conferencing, dramatically increasing clinic access. Patients that need an operation are then scheduled for a visit to MGH. Most postoperative visits have been converted to virtual visits as well. For a tertiary referral center such as ours, where patients often have to travel a significant distance to our facility, this is a change that many patients welcome—again a solution to a problem that we were not actively looking to solve.

As mentioned above, we have instituted a brief 6:45 a.m. huddle every morning to discuss the OR schedule for the day with our anesthesia, perfusion and nursing colleagues, to review the anticipated flow of the day. The surgeons briefly describe their cases (one‐liner), affording all to offer (or solicit) suggestions about particularly challenging or high risk cases. This way everyone knows what everyone else is doing. The logic of the flow of cases is reviewed so that there is no mystery as to why to‐follow cases are ordered as they are. Surgeons with less busy schedules for the day may offer to assist others in ways in which we would have all been unaware of previously. Any potential issues are identified early and solutions sought out. It also avoids conflict when decisions need to be made about resource allocation. The same format has been reproduced at a heart center level with a discussion at 7:00 a.m. amongst all cardiac procedural areas including the OR, cardiac catheterization lab and electrophysiology lab. This allows us to streamline access resources across the entire heart center including both procedural lab/OR time and ICU beds. This has led to more flexible scheduling of transcatheter valve implants or pacemaker generator changes for example. These are changes to our workflow that persist even after the pandemic has abated.

Beyond impacting efficiency and patient care, we believe that our conduct reinforced a sense of team‐work at an emotional level. As dry‐cleaning became a health hazard, most set aside our suits and ties; several seem unable to relocate them. While we attended division meetings and residency interviews via video, we also got a glimpse into each other's homes that we had not before. When one of our fellows tested positive for COVID‐19, one of the surgeons had groceries delivered to their apartment. The “downtime” of the pandemic allowed one of the surgeons to rekindle their woodworking/toy making passion to make a train engine for the son of one of our nurses who was infected with COVID‐19. When one of the surgeons fell ill on their call, and was being ruled out for COVID‐19, multiple surgeons offered to cover. Our ECMO surgeon volunteered to be called for every ECMO consult, so the exposure of other staff and residents to those high‐risk patients could be minimized. 2 Even though we could not gather in person, we held a virtual celebration for the retirement of a senior administrative cardiac OR nurse who had been with the cardiac surgery unit for over 45 years, including a video farewell from all the surgeons, not only wishing her well, but also recognizing the contributions that OR nursing and other technical staff make to the care of our patients.

The quip that “culture eats strategy for breakfast” is commonly attributed to Peter Drucker. If true, it would make sense then to focus on culture. Still, for all the “strategic planning sessions” that occur, it is striking how few “culture planning sessions” seem to take place. This may be because organizational culture is, on one hand, harder to see and yet omnipresent. It is difficult to define. Deeply ensconced in our social orders, it is characterized by passionately held assumptions. According to Edgar Schein, 3 it is manifest in behaviors (“how we do things around here”) and is expressed explicitly as values and supported by artifacts and creations. Believing that the field of cardiac surgery is a challenging one for us all, we have, with intent, valued our collective success and established, as an assumption, shared responsibility for shared resources. We have created processes as artifacts, characterized by transparency and collective reward, in alignment with these values. Our aim is to establish a culture of teamwork. We believe this leads to more satisfying careers for us as practitioners and better outcomes for our patients. We pride ourselves in making every effort to function as a learning organization, and to demonstrate not just resilience but antifragility. We also believe that this culture leads to healthier and more satisfying interpersonal relationships both at work and outside of work. We believe that we were better able to accommodate the stresses placed on our group by this crisis because of our culture and that the experience itself has made us stronger as a unit.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Concept and design: Arminder S. Jassar and Thoralf M. Sundt III. Data collection: Katy E. Perkins. Drafting article: Thoralf M. Sundt III and Arminder S. Jassar. Critical revision of article: Arminder S. Jassar, Katy E. Perkins, and Thoralf M. Sundt III. Approval of article: TMS.

Jassar AS, Perkins KE, Sundt TM. Teamwork in the time of coronavirus: An MGH experience. J Card Surg. 2021;36:1644‐1648. 10.1111/jocs.15036

[Correction added after first publication on 9 February 2021: The article title was revised.]

REFERENCES

- 1. Tanguturi VK, Lindman BR, Pibarot P, et al. Managing severe aortic stenosis in the COVID‐19 era [published online ahead of print, June 1, 2020]. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2020;S1936‐8798(20):31265‐31266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Osho AA, Moonsamy P, Hibbert KA, et al. Veno‐venous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for respiratory failure in COVID‐19 patients: Early experience from a Major Academic Medical Center in North America [published online ahead of print May 25, 2020]. Ann Surg. 2020;272:e75‐e78. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000004084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Schein EH Coming to a new awareness of organizational culture. MIT Sloan Management Review . January 15, 1984.