Abstract

The Hellenic Heart Failure Association has undertaken the initiative to develop a national network of heart failure clinics (HFCs) and cardio‐oncology clinics (COCs). We conducted two questionnaire surveys among these clinics within 17 months and another during the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak to assess adjustments of the developing network to the pandemic. Out of 68 HFCs comprising the network, 52 participated in the first survey and 55 in the second survey. The median number of patients assessed per week is 10. Changes in engaged personnel were encountered between the two surveys, along with increasing use of advanced echocardiographic techniques (23.1% in 2018 vs. 34.5% in 2020). Drawbacks were encountered, concerning magnetic resonance imaging and ergospirometry use (being available in 14.6% and 29% of HFCs, respectively), exercise rehabilitation programmes (applied only in 5.5%), and telemedicine applications (used in 16.4%). There are 13 COCs in the country with nine of them in the capital region; the median number of patients being assessed per week is 10. Platforms for virtual consultations and video calls are used in 38.5%. Coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak affected provision of HFC services dramatically as only 18.5% continued to function regularly, imposing hurdles that need to be addressed, at least temporarily, possibly by alternative methods of follow‐up such as remote consultation. The function of COCs, in contrast, seemed to be much less affected during the pandemic (77% of them continued to follow up their patients). This staged, survey‐based procedure may serve as a blueprint to help building national HFC/COC networks and provides the means to address changes during healthcare crises.

Keywords: Heart failure, Heart failure clinic, National network, Cardio‐oncology clinic, COVID‐19, Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2)

Background

The Hellenic Heart Failure Association § has undertaken the initiative to develop a national network of heart failure clinics (HFCs) and cardio‐oncology clinics (COCs), the Hellenic HF Clinics Network (HHFCN), consisting of healthcare units organized at three levels of infrastructure and expertise. 1 The mission of the HHFCN is to optimize the treatment and follow‐up of HF patients in order to improve their clinical outcomes in terms of survival, hospital admissions, and quality of life and to further reduce HF‐related healthcare expenditure and optimize the allocation of national healthcare resources. Although the HHFCN currently runs within the existing healthcare infrastructure, future planning to address the real healthcare needs of the population requires a registration of the current infrastructure and expertise within the network.

Aims

The aim of this study is to assess the distribution, infrastructure, resources, manpower, and level of training and expertise of the existing clinics that comprise the HHFCN, monitoring its evolution within a 17 month period and gauging the adjustments made because of the recent coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) outbreak.

Methods

Assessment was performed by two subsequent electronic 16‐item questionnaire surveys in September 2018 and February 2020, respectively. A supplementary questionnaire survey targeting COCs within the network was performed in February 2020. Given the recent COVID‐19 pandemic, a relative survey was further conducted in mid‐April 2020.

Results

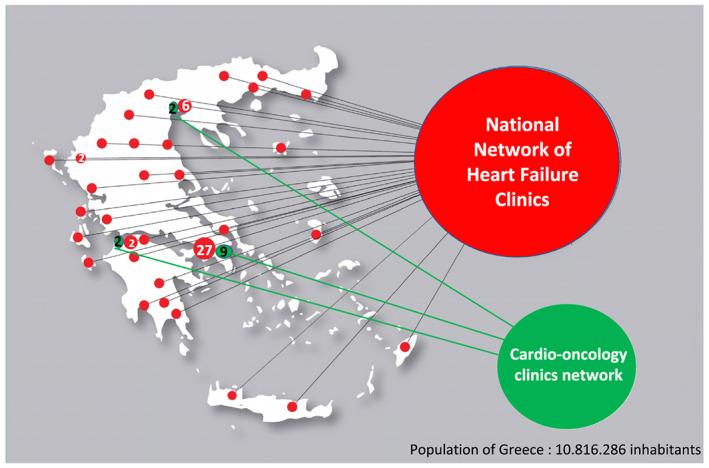

Heart failure clinics

Out of a total of 68 clinics comprising the network, 52 (76.4%) responded to the first survey and 55 (80.0%) to the second survey. A significant proportion of HFCs (n = 27, 39.7%) are located in the greater region of the capital (Figure 1 ). In terms of weekly schedule, 63.5% of HFCs see HF patients once a week (vs. 69.1% in 2020), 30.8% twice a week (vs. 21.8% in 2020), and 5.7% more than thrice a week (vs. 9.1% in 2020). The median number of patients treated per week is 10 [inter‐quartile range (IQR) 7–15].

Figure 1.

Distribution of heart failure and cardio‐oncology clinics in the country in the context of the National Network of Heart Failure Clinics.

The number and type of personnel engaged in HFCs are presented in Table 1 . One‐third of the clinics are not attended by a nurse; in more than half, no cardiology residents participate in the clinic; and in more than 80%, no cardiologists in HF subspecialty training attend. The median number of consultants in each HFC is 2 (IQR 1‐2). Both surveys revealed that 26% of the cardiologists in HFCs have a specific training/certification in HF, and at least one HF specialist can be found in 29% of HFCs (Supporting Information, Table S1 ).

Table 1.

Personnel engaged in the Hellenic Heart Failure Clinics Network during the two questionnaire surveys performed in September 2018 and February 2020

| Type of personnel | Number of clinics (%) | Number of clinics (%) |

|---|---|---|

| September 2018 | February 2020 | |

| N = 52 | N = 55 | |

| Consultant cardiologists, N1 = 97 and N2 = 99 | ||

| One consultant | 22 (42.3) | 27 (49.1) |

| Two consultants | 18 (34.6) | 17 (30.9) |

| Three consultants | 10 (19.2) | 6 (10.9) |

| Four consultants | 1 (1.9) | 5 (9.1) |

| Five consultants | 1 (1.9) | ‐ |

| Residents in cardiology, N1 = 36 and N2 = 23 | ||

| None | 27 (51.9) | 35 (63.6) |

| One resident | 18 (34.6) | 17 (30.9) |

| Two residents | 5 (9.6) | 3 (5.5) |

| Four residents | 2 (3.8) | ‐ |

| Attending cardiologists in heart failure subspecialty training, N1 = 13 and N2 = 13 | ||

| None | 42 (80.8) | 44 (80) |

| One cardiologist | 7 (13.5) | 9 (16.4) |

| Two cardiologists | 3 (5.8) | 2 (3.6) |

| Nurses, N1 = 39 and N2 = 40 | ||

| None | 17 (32.7) | 17 (30.9) |

| One nurse | 31 (59.6) | 36 (65.5) |

| Two nurses | 4 (7.7) | 2 (3.6) |

The numbers (N) in the first column refer to the number of consultant cardiologists, residents, and so forth in the first survey in 2018 registry and in the second survey in 2020 registry.

In terms of infrastructure of the hosting hospital, eight clinics (14.6%) have an in‐house cardiac magnetic resonance service, while additional 30 (54.5%) clinics have an established cooperation with a local or regional cardiac magnetic resonance laboratory. The incorporation of advanced echocardiographic techniques in clinical practice, namely, three‐dimensional echocardiography, speckle tracking strain analysis, and diastolic stress echocardiography, has been increased between the two surveys (23.1% in 2018 vs. 34.5% in 2020) (Supporting Information, Table S2 ). Natriuretic peptides (BNP and N‐terminal pro‐BNP) can be measured in the emergency department of the hosting hospital or in the clinic in more than 80% of the clinics [44 (84.6%) in the first survey vs. 47 (85.5%) in the second survey. Ergospirometry is used only in 15 (29%) HFCs and exercise programmes for HF rehabilitation only in 3 (5.5%) without any difference between the two surveys. Access to in‐house electrophysiology laboratory is available in nearly half of the units (46.2% in 2018 and 54.5% in 2020). Regarding inpatient facilities, ultrafiltration is widely available in 78.8% of hosting hospitals. Interventional procedures for structural heart disease such as transcatheter aortic valve implantation or transcatheter mitral valve repair (MitraClip) are performed in five facilities in 2018 and in six in 2020, while left ventricular assist devices are being implanted in three of the hospitals.

Heart failure clinics give patients the option to communicate with their doctor or nurse with several ways: by phone in 87.3%, by email in 50.9%, and by a web‐based platform able to perform video calls in 16.4%. One out of four clinics provides information on the services provided at the hosting hospital's web page. An electronic HF database or registry is used by 34 (65.4%) clinics. Special material such as brochures, videos, or online electronic material as a means of providing information and training to HF patients was used by 31 (59.6%) clinics in 2018 and by 41 (77.4%) in 2020. Thirty‐nine clinics (75%) in 2018 and 31 (56.3%) in 2020 had been actively involved in clinical research. A total of 45 (66.2%) clinics presented at least one abstract in national or international conferences and 38 (55.9%) published at least one peer‐reviewed paper during the preceding academic year (2017–2018), while for the subsequent academic year, at least 30 clinics (53.6%) presented abstracts and 21 (37.5%) published peer‐reviewed papers.

Cardio‐oncology clinics

A total of 13 COCs participated in the survey, nine of which were located in the capital region (Figure 1 ). The median number of patients seen per week is 10 (IQR 7–17.75), of the operating days per week is 1.5 (IQR 1–5) and of the cardiologists involved is 3 (IQR 2–5.50). The vast majority of cardiologists (92.3%) reported that they had some training in CO, most through attending congresses (84.6%) or studying educational material (books, manuscripts, etc.) (92.3%). There are a small number of cardiologists working in oncological hospitals with a long experience in CO.

In most of the hosting hospitals (92.3%), there is also an oncology and/or a haematology department. All COCs see patients before, during, and long term after cancer therapy, and every physician recognizes that special training is necessary for every cardiologist who treats patients with cancer. Cancer patients can contact attending cardiologists by phone in all COCs, by email in 61.5%, and by platforms for virtual consultations and video calls in 38.5%. Thirty‐eight per cent of COCs provide important information on the services provided at the hosting hospital's web page.

Heart failure clinics in the era of coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic

Only 18.5% of HFCs continue to function regularly during this pandemic, 5.5% refer their patients to general cardiology clinics, while the vast majority of patients are followed out of the hospital (in primary care services or in private practices). Digital web‐based applications that allow virtual consultations were available by 16.4% of HFCs before the pandemic and increased to 23.6% during this outbreak. A digital application for patient self‐assessment and follow‐up named ThessHF has been recently developed by the HFCs at Papanikolaou Hospital. Only one out of five HFCs has updated the information about the service provided at the hospital's web page. The majority of HFCs (87.3%) provide electronic prescriptions to HF patients without the need of a hospital visit. During the pandemic, the majority of HFCs (69.1%) estimate that admissions to hospitals due to decompensated HF have decreased, 21.8% believe that they are stable, while 7.3% report that there has been an increase.

Cardio‐oncology clinics in the era of coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic

The majority of COCs (77%) continue to follow up cancer patients, while only 23% report that patients are assessed out of hospital. However, 92.3% of the clinics give their patients the option of electronic prescriptions without a hospital visit. Because of the COVID‐19 outbreak, 30.8% of oncology patients start their anticancer treatment on time even without baseline CO assessment, while in 69.2%, baseline assessment is performed as always in the COCs. Pre‐operative cardiac assessment is performed in 54% by the cardiologists of COCs and in 46% by the cardiologist on call. Follow‐up visits were kept as scheduled before the pandemic in 30.8% of cases both for patients on active anticancer therapy and for those being followed because of cardiotoxicity history. Surveillance of oncology patients on treatment is performed only if they have a high cardiotoxicity risk in 15.4%, while it has been postponed in 23.1%. If patients on treatment develop cardiotoxicity, they are assessed in COCs in 61.5%, by the cardiologist on call in 15.4%, and in the emergency department in 23.1%.

Discussion

The present surveys depicted the current features of HFCs comprising a national network during its early stage of development, as part of a staged process that would allow the proper design of HF services throughout the country to address the real population needs. This process, involving first the development of a network comprising the existing clinics and facilities, second its longitudinal evaluation through surveys, and third its adjustment to real needs, may serve as a blueprint for other countries in their effort to develop an HFC network. Such a standardized procedure may contribute to the widespread implementation of the current standards of care that remain suboptimal and may further address the existing regional differences in the management of HF. 2 , 3 In addition, the existence of an organized network of clinics allows the rapid set‐up and conduct of surveys to address public health emergencies, such as the COVID‐19 pandemic, and other healthcare issues that may appear.

In Greece, nearly 40% of the HFCs are located in the capital region, which is consistent with the population distribution. It is important that HFCs exist all over the country, including far land areas and islands. In terms of personnel, the decrease in the number of residents involved in HFCs can be attributed to the great amount of residents that have left Greece because of the economic crisis. Cardiologists with special training in HF can be found in about one‐third of HFCs. Half of them have taken the European Society of Cardiology/Heart Failure Association exam for Heart Failure Certification, one‐third attended the Postgraduate Course in Heart Failure by the European Society of Cardiology/Heart Failure Association and University of Zurich, and the rest chose to be trained in HF through a fellowship. It is clear that training in HF in Greece needs proper reinforcement by increasing the HF fellowships provided, recognizing officially the HF subspecialization, and including adequate HF training in the core curriculum of cardiology.

The role of imaging in HFCs is crucial, and this is evident from the increased number of HFCs that incorporated the advanced echocardiographic techniques and diastolic stress echocardiography in clinical practice. 4 Availability of the rest of diagnostic modalities and advanced therapeutic interventions such as trancatheter valve implantation or repair or left ventricular assist device implantation is present in a sufficient number of hosting hospitals if the total population of the country is taken into account. However, it is important to reassure equal access of all patients to diagnostic and therapeutic modalities through inter‐clinic communication and collaboration as well as properly organized patient referral procedures.

In contrast, ergospirometry is underused, and HF rehabilitation facilities appear to be rather limited. Possible solutions include securing funds for the supply of the necessary equipment, training of the physicians for the most efficient application of ergospirometry and rehabilitation programmes, inclusion of rehabilitation programmes in reimbursement policies, and incorporation of them in clinical practice. The most important prerequisite is all the stakeholders to be aware of the indications of ergospirometry and of rehabilitation programmes' impact on patients' prognosis.

The field of CO is rapidly developing in the whole world including Greece. There is one COC for 1.3 million citizens in this country, a ratio similar to that of other European countries with well‐developed CO services including Spain (one per 1.2 million citizens) and Italy (one per 1.6 million). 5 , 6 Around 70% of COCs are located in Athens, within hospitals with oncological and haematological units. Special training on CO is a key unmet need encountered by our survey. However, cardiologists with continued involvement in the field are considered experts. As there is not yet an official CO fellowship in Greece, cardiologists treating oncology patients rely on self‐training or self‐education through textbooks, papers, webinars, and congresses. The recent developments of a Task Force on CO under the Hellenic Heart Failure Association and of a Working Group on CO within the Hellenic Society of Cardiology are expected to define the framework for CO training and practice in the country. 7

The COVID‐19 outbreak has affected the practice of both HFCs and COCs. Most HFCs do not see patients on a regular basis, using alternative methods of consulting patients. However, strategies in CO differ as cancer patients are treated according to their cardiotoxicity risk, and most of them are still under surveillance in COCs, as in other countries too. 8 However, both HFCs and COCs can make the most of the modern communication capabilities and telehealth 9 to ensure an accepted level of patient follow‐up while reducing the risk of exposure to the pandemic.

Two sequential questionnaire surveys were able to detect the status of the HFCs comprising the HHFCN in terms of distribution, infrastructure, manpower, and level of training and expertise as well as their longitudinal evolution. Benchmarking of these findings against national HF registry data will allow planning future adjustments to meet the population needs (Supporting Information, Table S3 ). Besides setting the grounds for the improvement of patients' care across the country, a structured national network of clinics is associated with numerous advantages, promotes effective cooperation between clinics, enhances research opportunities, supports guidelines implementation, allows rapid acquisition of data on public health emergencies, and facilitates faster and more efficient adjustments in similar crises.

Conflict of interest

None declared related to this manuscript.

Funding

Hellenic Heart Failure Association paid the publication fees for this manuscript.

Supporting information

Table S1. Accreditations and fellowships in heart failure among consultant cardiologists participating in the Hellenic Heart Failure Clinics Network (data from both surveys).

Table S2. Imaging modalities and other procedures in Heart Failure Clinics.

Table S3. Unmet needs and future actions of the Hellenic Heart Failure Association.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Mr Michalis Anastasiou for his administrative services.

The Taskforce of the Hellenic Heart Failure Clinics Network (2020) Distribution, infrastructure, and expertise of heart failure and cardio‐oncology clinics in a developing network: temporal evolution and challenges during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. ESC Heart Failure, 7: 3408–3413. 10.1002/ehf2.12870.

Footnotes

Hellenic Heart Failure Association stands for Hellenic Heart Failure Research Society in Greek (EMEKA).

Contributor Information

The Taskforce of the Hellenic Heart Failure Clinics Network:

Kalliopi Keramida, Dimitrios Farmakis, Katerina K. Naka, Maria Thodi, Vasiliki Bistola, Sotirios Xydonas, Apostolos Karavidas, Antonis Sideris, Athanasios Trikas, John Parissis, Filippos Triposkiadis, Stamatios Adamopoulos, and Gerasimos Filippatos

References

- 1. Task Force of the Hellenic Heart Failure Clinics Network . How to develop a national heart failure clinics network: a consensus document of the Hellenic Heart Failure Association. ESC Heart Fail 2020; 7: 15–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Komajda M, Schöpe J, Wagenpfeil S, Tavazzi L, Böhm M, Ponikowski P, Anker SD, Filippatos GS, Cowie MR, QUALIFY Investigators . Physicians' guideline adherence is associated with long‐term heart failure mortality in outpatients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: the QUALIFY international registry. Eur J Heart Fail 2019; 21: 921–929.30933403 [Google Scholar]

- 3. Maggioni AP, Dahlström U, Filippatos G, Chioncel O, Crespo Leiro M, Drozdz J, Fruhwald F, Gullestad L, Logeart D, Fabbri G, Urso R. EURObservational Research Programme: regional differences and 1‐year follow‐up results of the Heart Failure Pilot Survey (ESC‐HF Pilot). Eur J Heart Fail 2013; 15: 808–817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pieske B, Tschöpe C, de Boer RA, Fraser AG, Anker SD, Donal E, Edelmann F, Fu M, Guazzi M, Lam CSP, Lancellotti P, Melenovsky V, Morris DA, Nagel E, Pieske‐Kraigher E, Ponikowski P, Solomon SD, Vasan RS, Rutten FH, Voors AA, Ruschitzka F, Paulus WJ, Seferovic P, Filippatos G. How to diagnose heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: the HFA‐PEFF diagnostic algorithm: a consensus recommendation from the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2019; 40: 3297–3317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mitroi C, Martín‐García A, Ramos PM, Echaburu JV, Arenas‐Prat M, García‐Sanz R, Esteban VA, García‐Pinilla JM, Cosín‐Sales J, López‐Fernández T. Current functioning of cardio‐oncology units in Spain. Clin Transl Oncol 2020; 22: 1418–1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Canale MLLC, Bisceglia I, Vallerio P, Parrini I, Associazione Nazionale Medici Cardiologi Ospedalieri (ANMCO) Cardio‐Oncology Task Force . Cardio‐oncology organization patterns in Italy: one size does not fit all. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown) 2018; 19: 229–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Farmakis D, Keramida K, Filippatos G. How to build a cardio‐oncology service? Eur J Heart Fail 2018; 20: 1732–1734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pramesh CS, Badwe RA. Cancer management in India during Covid‐19. N Engl J Med 2020; 382: e61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Parikh A, Kumar AA, Jahangir E. Cardio‐oncology care in the time of COVID‐19 and the role of telehealth. JACC CardioOncol 2020; 2: 356–358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Accreditations and fellowships in heart failure among consultant cardiologists participating in the Hellenic Heart Failure Clinics Network (data from both surveys).

Table S2. Imaging modalities and other procedures in Heart Failure Clinics.

Table S3. Unmet needs and future actions of the Hellenic Heart Failure Association.