Abstract

Several months ago, an outbreak of pneumonia of unknown aetiology was detected in Wuhan City (China) and the aetiological agent of the atypical pneumonia was isolated by the Chinese authorities as novel coronavirus (2019‐nCoV or SARS‐CoV‐2). The WHO announced this new disease was to be known as “COVID‐19.” When looking for new antiviral compounds, knowledge of the main viral proteins is fundamental. The major druggable targets of SARS‐CoV‐2 include 3‐chymotrypsin‐like protease (3CLpro), papain‐like protease (PLpro), RNA‐dependent RNA polymerase, and spike (S) protein. Quercetin inhibits 3CLpro and PLpro with a docking binding energy corresponding to −6.25 and −4.62 kcal/mol, respectively. Quercetin has a theoretical, but significant, capability to interfere with SARS‐CoV‐2 replication, with the results showing this to be the fifth best compound out of 18 candidates. On the basis of the clinical COVID‐19 manifestations, the multifaceted aspect of quercetin as both antiinflammatory and thrombin‐inhibitory actions, should be taken into consideration.

Keywords: COVID‐19, infectious diseases, nutraceutical, quercetin, SARS‐CoV‐2

Abbreviations

- ARDS

acute respiratory distress syndrome

- MERS‐CoV

middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus

- MODS

multiple organ dysfunction syndrome

- SARS‐CoV‐1

severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus‐1

- SARS‐CoV‐2

severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus‐2

- WHO

World Health Organization

1. INTRODUCTION

Viral diseases continue to pose a serious threat to public health. The world has witnessed several viral epidemics over the past 20 years, including severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronavirus (SARS‐CoV‐1) in 2003, the influenza disease called H1N1 in 2009, and the middle east respiratory syndrome (MERS) coronavirus (MERS‐CoV) in 2012. Several months ago, an outbreak of pneumonia of unknown aetiology was detected in Wuhan City, Province of Hubei (China) and reported to the China Country Office of the World Health Organization (WHO) on December 31, 2019. The National Health Commission of China reported the outbreak was associated with exposure in one seafood market in Wuhan City. The aetiological agent of the atypical pneumonia was isolated on January 7, 2020 by the Chinese authorities as novel coronavirus (2019‐nCoV). The date of January 22, 2020 is important as it is thought to be when the virus appeared in Europe. The virus was isolated in Bavaria (Germany) from a German patient infected by an individual from Shanghai (China). Subsequently, the virus was present in Italy on January 25, 2020. The unsuspecting individuals infected with the virus are thought to have been able to circulate in the area of Basso Lodigiano with few symptoms or with symptoms mistaken for those of influenza.

On January 30, 2020, the WHO declared the situation a public health emergency of international concern (World Health Organization, 2020a) and on February 11, 2020, the WHO announced that the disease caused by this new virus was to be known as “COVID‐19,” which is an acronym of “coronavirus disease‐2019.”

On February 20, 2020, the first symptomatic COVID‐19 patient was identified in Italy at the Emergency Department of Codogno Hospital, Basso Lodigiano, Province of Lodi.

On February 26, 2020, the Director‐General of the WHO announced that the number of new cases of the viral disease, now officially known as COVID‐19, reported outside China since the day before had for the first time exceeded the number of new cases in China (World Health Organization, 2020b). On March 11, 2020, the WHO declared this viral disease to be a pandemic.

2. AETIOLOGY

Coronaviruses constitute a large family of viruses. They are single‐stranded RNA viruses, with a crown‐like appearance under an electron microscope.

Coronaviruses were identified in the mid‐1960s and are known to infect humans and certain animals (including birds and mammals). The primary target cells are the epithelial cells of the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts.

SARS‐CoV‐2 is a single‐stranded, positive‐sense RNA virus, having a diameter of 60–140 nm with a round or elliptic shape; however, it often exists in a pleomorphic state. Its RNA genome contains 29,891 nucleotides, encoding 9,860 amino acids, and shares 99.9% sequence identity compared to bat genome (bat‐SL‐CoVZC45), suggesting a very recent host shift into humans. Like other CoVs, it is sensitive to ultraviolet rays and heat. In addition, these viruses can be effectively inactivated by lipid solvents including chloroform, ether (75%), ethanol, peroxyacetic acid, and chlorine‐containing disinfectant. Chlorhexidine does not inactivate this virus (Chan et al., 2013; Chen et al., 2020).

3. TRANSMISSION

The new CoV, SARS‐CoV‐2, is a respiratory virus that spreads mainly through contact with the breath droplets of infected individuals, for example, through: (a) saliva, coughing, and sneezing; (b) direct personal contact; (c) hands, for example, by touching the mouth, nose, or eyes with contaminated (unwashed) hands. SARS‐CoV‐2 then uses the angiotensin‐converting enzyme II (ACE2) receptor expressed by human cells to attach to these, as with SARS‐CoV‐1 (Li et al., 2020). Studies have shown the virus survives on different surfaces for days and remains viable in aerosols for hours (van Doremalen et al., 2020). It is possible that transmission occurs via the faecal–oral route. Transmission of the virus from asymptomatic patients has been reported, with a high viral load in pharyngeal samples from minimally symptomatic patients during the initial period of the disease. This is different to what is seen with SARS and MERS, where infectivity peaks relatively later during symptomatic infection, and may account for the much greater spread of COVID‐19. However, the highest transmission rates have been reported to correlate with disease severity and are particularly pronounced in hospital settings, just as for SARS and MERS. The incubation period is thought to vary from 3 to 14 days, while onset of symptoms has been reported up to 14 days after exposure (Lauer et al., 2020) providing the basis for the length of quarantine/self‐isolation. A possible scenario resulting from this could therefore be potential transmission before the onset of symptoms: in fact, many cases were, unfortunately, isolated after the onset of symptoms (He et al., 2020).

4. CLINICAL PATTERNS

The symptoms that patients with COVID‐19 may exhibit are variable. Generally, patients are characterised by three main symptoms: (a) fever, (b) dry cough, and (c) dyspnoea.

We can classify the infection as symptomatic or asymptomatic. In addition, there are prodromal signs such as conjunctivitis (often the first sign) or gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and diarrhoea.

Some patients may present without fever, but with abdominal pain, anorexia, and dyspnoea. Less frequently occurring, but particularly typical of this new pathology, are anosmia and dysgeusia, often accompanied by gastrointestinal symptoms (Huang et al., 2020).

Negative prognostic epidemiological risk factors are older age, male sex, and smoking and poor prognostic clinical risk factors include associated comorbidities such as obesity, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, chronic kidney disease, as well as—of course—respiratory diseases. The greater the number of risk factors and associated pathologies, the higher the risk of a poor prognosis (Chen et al., 2020). A mild symptomatology can resolve itself even without particular medical treatment at home or, instead, it can progress towards pneumonia (bilateral interstitial pneumonia) and respiratory failure, thereby requiring hospitalisation of the patient. Patients can progress rapidly towards acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) with multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS) and death (Wang et al., 2020).

5. THERAPY

Currently, COVID‐19 therapy is only supportive and prevention is the only way to reduce transmission and limit spread. From a pharmacological perspective, initial treatment with lopinavir/ritonavir and with chloroquine was attempted. Due to a lack of chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine was then used (Dong, Hu, & Gao, 2020).

In addition, a number of antibiotics have been used, such as ceftriaxone with azithromycin or piperacillin/tazobactam and doxycycline, and then back to azithromycin alone.

From mid‐March 2020, lopinavir/ritonavir was replaced with remdesivir and the use of tocilizumab, and immediately after, heparin was suggested as a potential treatment. It was then proposed that glucocorticoids could be beneficial in the early stages of the disease; these had also been used in China, but there is currently some disagreement regarding their efficacy (Zhang et al., 2020).

Currently, the use of plasma with antibodies obtained from patients who have had COVID‐19 seems to have a good rationale, although the initial data from a limited number of patients are not encouraging (Zeng et al., 2020).

6. THE FLAVONOID QUERCETIN

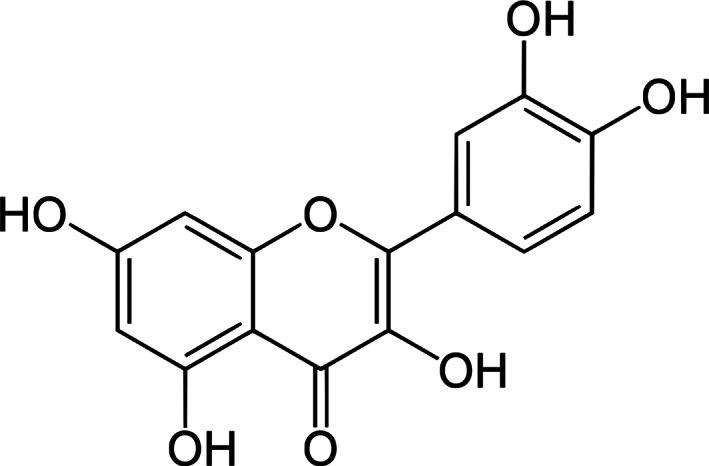

Quercetin (Figure 1), chemical name 2‐(3,4‐dihydroxyphenyl)‐3,5,7‐trihydroxychromen‐4‐one or 3,3′,4′,5,7‐pentahydroxyflavone, is classified as a flavonol, one of the six subcategories of flavonoid compounds, and is the major polyphenolic flavonoid found in various vegetables and fruits, such as berries, lovage, capers, cilantro, dill, apples, and onions (Anand, Arulmoli, & Parasuraman, 2016). It is yellow in colour and completely soluble in lipids and alcohol, insoluble in cold water, and sparingly soluble in hot water. “Quercetin” derives from the Latin word “quercetum,” meaning “oak forest,” and as a flavonol, is not produced in the human body (Lakhanpal & Rai, 2007). Quercetin is one of the most important plant molecules, showing pharmacological activity such as antiviral, anti‐atopic, pro‐metabolic, and antiinflammatory effects. It has also been demonstrated to have a wide range of anticancer properties, and several reports indicate its efficacy as a cancer‐preventing agent. Quercetin also has psychostimulant properties and has been documented to prevent platelet aggregation, capillary permeability, lipid peroxidation, and to enhance mitochondrial biogenesis (Aguirre, Arias, Macarulla, Gracia, & Portillo, 2011; Dabeek & Marra, 2019).

FIGURE 1.

Chemical structure of quercetin

7. QUERCETIN AND MOLECULAR DOCKING

Recently, in order to find new candidates expressing potential activity against SARS‐CoV‐2 viral targets, a number of studies reporting the use of computer modelling for screening purposes have been published (Liu & Zhou, 2005; Lung et al., 2020; Toney, Navas‐Martín, Weiss, & Koeller, 2004; Wang et al., 2007; Zhang et al., 2020). Typically, these models determine the free energy of binding between a ligand and a receptor (Forli et al., 2016). A lower binding free energy indicates a stronger ligand–receptor interaction. Although obtaining comparable results via different modelling approaches can be a challenge (Aldeghi, Heifetz, Bodkin, Knapp, & Biggin, 2016), computer‐based molecular docking allows visualisation of the relative binding affinity of thousands of molecules for the above‐listed viral receptors.

In addition to the speed and versatility of this method for rapidly finding a potent inhibitor of SARS‐CoV‐2, another advantage of molecular docking screening is the reduction of the high costs associated with physically screening the activity of large banks of natural substances (Chen, de Bruyn, & Kirchmair, 2017). Compounds that through this method demonstrate significant interaction with viral receptors can then be moved onto cell‐based assays to verify effectiveness and toxicity. Confirmatory results can then accelerate testing in animals and clinical trials.

Recently, the virtual screening (Lung et al., 2020) of 83 compounds commonly used in Chinese traditional medicine for activity against the RNA‐dependent RNA polymerase of SARS‐CoV‐2 identified the aflavin, an antioxidant polyphenol, as a potential inhibitor. Similarly, virtual screening of 115 compounds used within Chinese traditional medicine highlighted 13 for further studies (Zhang et al., 2020). Some of these were naturally occurring polyphenolic compounds such as quercetin and kaempferol, which have already received considerable attention for the treatment of other disease types (Cassidy et al., 2020; Khan et al., 2019; Tomé‐Carneiro & Visioli, 2016). In particular, the study showed a significant inhibition by quercetin of 3CLpro and PLpro with a docking binding energy corresponding to −6.25 and −4.62 kcal/mol, respectively (Zhang et al., 2020).

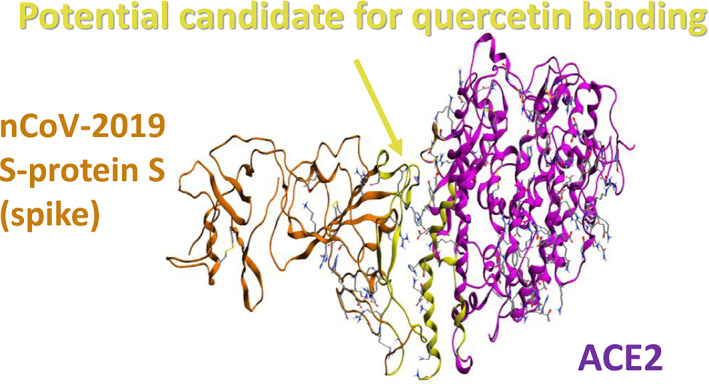

Moreover, Smith and Smith (2020) demonstrated for quercetin a theoretical, but significant, capability to interfere with SARS‐CoV‐2 replication, with the results showing this to be the fifth best compound out of 18 candidates. In fact, a reasonable target for structure‐based drug discovery was identified to be the disruption of the viral S protein‐ACE2 receptor interface (Figure 2). Once again, a computational docking model was used to identify small molecules that were able to bind to either the isolated viral S protein at its host receptor binding region or to the S protein–human ACE2 receptor interface, to potentially limit viral recognition of host cells and/or to disrupt host–virus interactions. Among the natural compounds tested, quercetin was identified as being between the top scoring ligands for the S protein:ACE2 receptor interface, further confirming its role as a promising antiviral agent that should be further investigated.

FIGURE 2.

A reasonable target for structure‐based drug discovery was identified to be the disruption of the viral S protein‐ACE2 receptor interface. Rendering of nCoV‐2019 S‐protein and ACE2 receptor. Green represents the interface targeted for docking. Source: Smith and Smith (2020), ChemRxiv [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

An in vitro molecular docking study was also performed to analyse the probability of molecular docking between quercetin and viral protease. Proteases play essential roles in viral replication, and specifically, 6LU7 was determined to be the main protease (Mpro) found in SARS‐CoV‐2. Quercetin formed H‐bonds with the 6LU7 amino acids His164, Glu166, Asp187, Gln192, and Thr190, with all of the H‐bonds interacting with amino acids in the virus Mpro active site (Khaerunnisa, Kurniawan, Awaluddin, Suhartati, & Soetjipto, 2020). The genome of SARS‐CoV‐2 is approximately 79% identical to that of SARS‐CoV‐1 (Hui et al., 2020). It is therefore not surprising that quercetin showed an IC50 of 8.6 ± 3.2 μM against SARS‐CoV‐1 PLpro (Park et al., 2017).

Nevertheless, 3 years have passed since this evidence was obtained, and unfortunately, no cell‐based assay of antiviral activity has been performed. Very recently, quercetin was reported to have antiviral activity with respect to SARS‐CoV‐1 by inhibiting also 3CLpro (Jo, Kim, Shin, & Kim, 2020).

8. MULTIFACETED QUERCETIN AND ITS CLINICAL RELEVANCE

On the basis of the results obtained by computational methods on molecular docking, it is anticipated that quercetin could have an effect on SARS‐CoV‐2 by interacting with 3CLpro, PLpro, and/or S protein. In addition to these targets, other findings could prompt us to consider quercetin as being endowed with a general, that is, not specific only for CoV, antiviral role (Chiow, Phoon, Putti, Tan, & Chow, 2016; Fanunza et al., 2020; Jo, Kim, Kim, Shin, & Kim, 2019; Mani et al., 2020; Nguyen et al., 2012; Park, Yoon, Kim, Lee, & Chong, 2012; Song, Shim, & Choi, 2011). In any case, based on the strong inflammatory cascade and the blood clotting phenomena triggered during SARS‐CoV‐2 infection, the multifaceted aspect of quercetin, which has been well described as exerting both antiinflammatory (quercetin dose‐dependently decreases the mRNA and protein levels of ICAM‐1, IL‐6, IL‐8, and MCP‐1) and thrombin‐inhibitory actions (Chen et al., 2011; Cheng, Huang, Pang, Wu, & Cheng, 2019; Liu et al., 2010), should be taken into consideration.

To date, a considerable amount of data has been accumulated describing the potential antiviral role (among others) of quercetin (Table 1). Indeed, several studies, using computational models and in vitro and in vivo assays, would seem to confirm this. At the present time, however, the critical lack of high‐quality clinical data must be highlighted, although some empirical and/or case–control clinical evaluations would appear encouraging. A randomised study performed a decade ago enrolled 1,002 adult subjects affected by viral infections of the upper respiratory tract; this showed that quercetin administered at very high dosages (1,000 mg/dose) for 12 weeks reduced the days of illness in middle‐aged and elderly subjects (Heinz et al., 2010). More recently, an empirical study conducted at a Wuhan hospital showed that an approach where, in addition to conventional therapies, patients were treated with traditional Chinese medicine remedies, including herbs with a high quercetin content, was medically safe, free from particular side effects additional to those obtained with the conventional approach alone, and was able to improve the symptoms of patients with COVID‐19 (Luo et al., 2020); (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Studies regarding quercetin

| Author | Year | Duration | Botanical compound | Species | Parameters | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chen et al. | 2011 | 48 hr | Houttuynia cordata Thunb., a plant containing flavonoids like quercetin, quercitrin, and isoquercitrin | Vero cells | The effect on HSV‐2 infection was determined by measuring cell viability using MTT assay | Quercetin, quercitrin, or isoquercitrin at 10 μM showed significant activity against HSV‐2 infection through inhibition of NF‐κB activation, while naringenin, a dihydroflavonoid from grape fruit showed no effect against HSV‐2 infection, indicating that the flavonoids are responsible for anti‐HSV‐2 activity in hot water extract of Houttuynia cordata |

| Cheng et al. | 2019 | Quercetin at various concentrations (2.5–20 μM) | ARPE‐19 cells | Quercetin effects on interleukin‐1β (IL‐1β)‐induced production of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines in ARPE‐19 cells | Quercetin could dose‐dependently decrease the mRNA and protein levels of ICAM‐1, IL‐6, IL‐8, and monocyte chemoattractant protein‐1 (MCP‐1). It also attenuated the adherence of the human monocytic leukaemia cell line THP‐1 to IL‐1β‐stimulated ARPE‐19 cells | |

| Fanunza et al. | 2020 | A small set of flavonoids including quercetin and wogonin | Quercetin and wogonin can suppress the VP24 effect on IFN‐I signalling inhibition. Quercetin showed a half‐maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of 7.4 μM, and it was characterised to significantly restore the IFN‐I signalling cascade, blocked by VP24, by directly interfering with the VP24 binding to karyopherin‐α and thus restoring P‐STAT1 nuclear transport and IFN gene transcription. Quercetin significantly blocked viral infection, specifically targeting EBOV VP24 anti‐IFN‐I function | |||

| Heinz et al. | 2010 | 12 weeks | Two quercetin doses (500 and 1,000 mg/day) | 1,002 subjects | Upper respiratory tract infection rates | For all subjects combined, quercetin supplementation over 12 weeks had no significant influence on upper respiratory tract infection rates or symptomatology compared to placebo. A reduction in upper respiratory tract infection total sick days and severity was noted in middle aged and older subjects ingesting 1,000 mg quercetin/day for 12 weeks who rated themselves as physically fit |

| Luo et al. | 2020 | 8.96 days | Herbs with a high quercetin content | 54 patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia | Hemogram, days of hospitalisation | The clinical results of our study showed that 54 patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia enhanced immune ability against COVID‐19 by detecting blood samples after traditional Chinese medicine treatment and category of invigorating spleen and removing dampness appears to shorten patients' hospitalisation day |

9. CONCLUSION

In the recent past, there have been several pandemics. Within the context of globalisation, some of these pandemics have truly raised the global risk to humankind. The COVID‐19 pandemic is the latest of these and is, so far, completely unresolved. In the meantime, as we await the development of an effective vaccine, researchers worldwide must focus all their efforts on selecting possible effective treatments, bearing in mind that the plant kingdom supplies chemical skeletons that, since ancient times, have provided humans with “drugs.” As a recent example, we remember the anti‐malarial drug artemisinin obtained from Artemisia annua, the studies on which resulted in 2015 in a Nobel Prize being awarded to the researcher Tu Youyou (Mikić, 2015).

Although a repeat of the artemisinin success story may be unlikely, the volume of data that recommends quercetin as a potential molecule candidate for an anti‐COVID‐19 role strongly supports the execution of a case–control clinical study with the aim of realising its possible efficacy within the context of this disease. On the basis of its poor pharmacokinetics profile, any galenic formulation aimed to improve its rate of absorption should be considered important. At our knowledge, the Phytosome form of quercetin could be a possible candidate.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organisation or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties. No writing assistance was utilised in the production of this manuscript.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors equally contributed in writing the manuscript.

Derosa G, Maffioli P, D'Angelo A, Di Pierro F. A role for quercetin in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19). Phytotherapy Research. 2021;35:1230–1236. 10.1002/ptr.6887

REFERENCES

- Aguirre, L. , Arias, N. , Macarulla, M. T. , Gracia, A. , & Portillo, M. P. (2011). Beneficial effects of quercetin on obesity and diabetes. Open Nutraceuticals Journal, 4, 189–198. [Google Scholar]

- Aldeghi, M. , Heifetz, A. , Bodkin, M. J. , Knapp, S. , & Biggin, P. C. (2016). Accurate calculation of the absolute free energy of binding for drug molecules. Chemical Science, 7, 207–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anand, D. A. V. , Arulmoli, R. , & Parasuraman, S. (2016). Overviews of biological importance of quercetin: A bioactive flavonoid. Pharmacognosy Reviews, 10, 84–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy, L. , Fernandez, F. , Johnson, J. B. , Naiker, M. , Owoola, A. G. , & Broszczak, D. A. (2020). Oxidative stress in Alzheimer's disease: A review on emergent natural polyphenolic therapeutics. Complementary Therapies in Medicine, 49, 102294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan, J. F ., To, K. K. , Tse, H. , Jin, D. J. , & Yuen, K. Y. (2013). Interspecies transmission and emergence of novel viruses: lessons from bats and birds. Trends Microbiol 21, 544–555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X. , Wang, Z. , Yang, Z. , Wang, J. , Xu, Y. , Tan, R. X. , & Li, E. (2011). Houttuynia cordata blocks HSV infection through inhibition of NF‐κB activation. Antiviral Research, 92, 341–345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y. , de Bruyn, K. C. , & Kirchmair, J. (2017). Data resources for the computer‐guided discovery of bioactive natural products. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling, 57, 2099–2111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, N. , Zhou, M. , Dong, X. , Qu, J. , Gong, F. , Han, Y. , … Zhang, L. (2020). Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: A descriptive study. Lancet, 395, 507–513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, S. C. , Huang, W. C. , Pang, J. H. S. , Wu, Y. H. , & Cheng, C. Y. (2019). Quercetin inhibits the production of IL‐1β‐induced inflammatory cytokines and chemokines in ARPE‐19 cells via the MAPK and NF‐κB signaling pathways. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 20, 2957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiow, K. H. , Phoon, M. C. , Putti, T. , Tan, B. K. , & Chow, V. T. (2016). Evaluation of antiviral activities of Houttuynia cordata Thunb. extract, quercetin, quercetrin and cinanserin on murine coronavirus and dengue virus infection. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Medicine, 9, 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dabeek, W. M. , & Marra, M. V. (2019). Dietary quercetin and kaempferol: Bioavailability and potential cardiovascular‐related bioactivity in humans. Nutrients, 11, 2288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong, L. , Hu, S. , & Gao, J. (2020). Discovering drugs to treat coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19). Drug Discoveries and Therapeutics, 14, 58–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanunza, E. , Iampietro, M. , Distinto, S. , Corona, A. , Quartu, M. , Maccioni, E. , … Tramontano, E. (2020). Quercetin blocks Ebola virus infection by counteracting the VP24 interferon inhibitory function. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 64(7), e00530‐20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forli, S. , Huey, R. , Pique, M. E. , Sanner, M. F. , Goodsell, D. S. , & Olson, A. J. (2016). Computational protein‐ligand docking and virtual drug screening with the AutoDock suite. Nature Protocols, 11, 905–919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He, X. , Lau, E. H. Y. , Wu, P. , Deng, X. , Wang, J. , Hao, X. , … Leung, G. M. (2020). Temporal dynamics in viral shedding and transmissibility of COVID‐19. Nature Medicine, 26, 672–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinz, S. A. , Henson, D. A. , Austin, M. D. , Jin, F. , & Nieman, D. C. (2010). Quercetin supplementation and upper respiratory tract infection: A randomized community clinical trial. Pharmacological Research, 62, 237–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang, C. , Wang, Y. , Li, X. , Ren, L. , Zhao, J. , Hu, Y. , … Cao, B. (2020). Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet, 395, 497–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hui, D. S. , Azhar, E. I. , Madani, T. A. , Ntoumi, F. , Kock, R. , Dar, O. , … Petersen, E. (2020). The continuing 2019‐nCoV epidemic threat of novel coronaviruses to global health – The latest 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan, China. International Journal of Infectious Diseases, 91, 264–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo, S. , Kim, H. , Kim, S. , Shin, D. H. , & Kim, M. S. (2019). Characteristics of flavonoids as potent MERS‐CoV 3C‐like protease inhibitors. Chemical Biology & Drug Design, 94, 2023–2030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo, S. , Kim, S. , Shin, D. H. , & Kim, M. S. (2020). Inhibition of SARS‐CoV 3CL protease by flavonoids. Journal of Enzyme Inhibition and Medicinal Chemistry, 35, 145–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khaerunnisa, S. , Kurniawan, H. , Awaluddin, R. , Suhartati, S. , & Soetjipto, S. (2020). Potential inhibitor of COVID‐19 main protease (Mpro) from several medicinal plant compounds by molecular docking study. Preprints, 2020030226. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, H. , Sureda, A. , Belwal, T. , Çetinkaya, S. , Süntar, İ. , Tejada, S. , … Aschner, M. (2019). Polyphenols in the treatment of autoimmune diseases. Autoimmunity Reviews, 18, 647–657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakhanpal, P. , & Rai, D. K. (2007). Quercetin: A versatile flavonoid. International Journal of Medicine, 2, 22–37. [Google Scholar]

- Lauer, S. A. , Grantz, K. H. , Bi, Q. , Jones, F. K. , Zheng, Q. , Meredith, H. R. , … Lessler, J. (2020). The incubation period of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) from publicly reported confirmed cases: Estimation and application. Annals of Internal Medicine, 172, 577–582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q. , Guan, X. , Wu, P. , Wang, X. , Zhou, L. , Tong, Y. , … Feng, Z. (2020). Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus‐infected pneumonia. The New England Journal of Medicine, 382, 1199–1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, B. , & Zhou, J. (2005). SARS‐CoV protease inhibitors design using virtual screening method from natural products libraries. Journal of Computational Chemistry, 26, 484–490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L. , Ma, H. , Yang, N. , Tang, Y. , Guo, J. , Tao, W. , & Duan, J. (2010). A series of natural flavonoids as thrombin inhibitors: Structure‐activity relationships. Thrombosis Research, 126, e365–e378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lung, J. , Lin, Y. S. , Yang, Y. H. , Chou, Y. L. , Shu, L. H. , Cheng, Y. C. , … Wu, C. Y. (2020). The potential chemical structure of anti‐SARS‐CoV‐2 RNA‐dependent RNA polymerase. Journal of Medical Virology, 92, 693–697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo, E. , Zhang, D. , Luo, H. , Liu, B. , Zhao, K. , Zhao, Y. , … Wang, Y. (2020). Treatment efficacy analysis of traditional Chinese medicine for novel coronavirus pneumonia (COVID‐19): An empirical study from Wuhan, Hubei Province, China. Chinese Medicine, 15, 34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mani, J. S. , Johnson, J. B. , Steel, J. C. , Broszczak, D. A. , Neilsen, P. M. , Walsh, K. B. , & Naiker, M. (2020). Natural product‐derived phytochemicals as potential agents against coronaviruses: A review. Virus Research, 284, 197989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikić, D. (2015). The 2015 Nobel Prize laureates in physiology or medicine. Vojnosanitetski Pregled, 72, 951–952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T. T. , Woo, H. J. , Kang, H. K. , Nguyen, V. D. , Kim, Y.‐M. , Kim, D.‐W. , … Kim, D. (2012). Flavonoid‐mediated inhibition of SARS coronavirus 3C‐like protease expressed in Pichia pastoris . Biotechnology Letters, 34, 831–838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park, H. R. , Yoon, H. , Kim, M. K. , Lee, S. D. , & Chong, Y. (2012). Synthesis and antiviral evaluation of 7‐O‐arylmethylquercetin derivatives against SARS‐associated coronavirus (SCV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV). Archives of Pharmacal Research, 35, 77–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park, J. Y. , Yuk, H. J. , Ryu, H. W. , Lim, S. H. , Kim, K. S. , Park, K. H. , … Lee, W. S. (2017). Evaluation of polyphenols from Broussonetia papyrifera as coronavirus protease inhibitors. Journal of Enzyme Inhibition and Medicinal Chemistry, 32, 504–515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, M. , & Smith, J. C. (2020). Repurposing therapeutics for COVID‐19: Supercomputer‐based docking to the SARS‐CoV‐2 viral spike protein and viral spike protein‐human ACE2 interface. ChemRxiv. 10.26434/chemrxiv.11871402.v3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Song, J. H. , Shim, J. K. , & Choi, H. J. (2011). Quercetin 7‐rhamnoside reduces porcine epidemic diarrhea virus replication via independent pathway of viral induced reactive oxygen species. Virology Journal, 8, 460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomé‐Carneiro, J. , & Visioli, F. (2016). Polyphenol‐based nutraceuticals for the prevention and treatment of cardiovascular disease: Review of human evidence. Phytomedicine, 23, 1145–1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toney, J. H. , Navas‐Martín, S. , Weiss, S. R. , & Koeller, A. (2004). Sabadinine: A potential non‐peptide anti‐severe acutne‐respiratory‐syndrome agent identified using structure‐aided design. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry, 47, 1079–1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Doremalen, N. , Bushmaker, T. , Morris, D. H. , Holbrook, M. G. , Gamble, A. , Williamson, B. N. , … Munster, V. J. (2020). Aerosol and surface stability of SARS‐CoV‐2 as compared with SARS‐CoV‐1. The New England Journal of Medicine, 382, 1564–1567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S. Q. , Du, Q. S. , Zhao, K. , Li, A. X. , Wei, D. Q. , & Chou, K. C. (2007). Virtual screening for finding natural inhibitor against cathepsin‐L for SARS therapy. Amino Acids, 33, 129–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D. , Hu, B. , Hu, C. , Zhu, F. , Liu, X. , Zhang, J. , … Peng, Z. (2020). Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus‐infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. Journal of the American Medical Association, 323, 1061–1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . (2020a). https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/30-01-2020-statement-on-the-second-meeting-of-the-international-health-regulations-(2005)-emergency-committee-regarding-the-outbreak-of-novel-coronavirus-(2019-ncov)

- World Health Organization . (2020b). https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-mission-briefing-on-covid-19---26-february-2020

- Zhang, D. H. , Wu, K. L. , Zhang, X. , Deng, S. Q. , & Peng, B. (2020). In silico screening of Chinese herbal medicines with the potential to directly inhibit 2019 novel coronavirus. Journal of Integrative Medicine, 18, 152–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W. , Zhao, Y. , Zhang, F. , Wang, Q. , Li, T. , Liu, Z. , … Zhang, S. (2020). The use of anti‐inflammatory drugs in the treatment of people with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19): The perspectives of clinical immunologists from China. Clinical Immunology, 214, 108393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, Q. L. , Yu, Z. J. , Gou, J. J. , Li, G. M. , Ma, S. H. , Zhang, G. F. , … Liu, Z. S. (2020). Effect of convalescent plasma therapy on viral shedding and survival in COVID‐19 patients. Journal of Infectious Diseases, 222, 38–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]