Abstract

The government of India implemented social distancing interventions to contain the COVID‐19 epidemic. However, effects of these interventions on epidemic dynamics are yet to be understood. Rates of laboratory‐confirmed COVID‐19 infections per day and effective reproduction number (Rt ) were estimated for 7 periods (Pre‐lockdown, Lockdown Phases 1 to 4 and Unlock 1–2) according to nationally implemented interventions with phased relaxation. Adoption of these interventions was estimated using Google mobility data. Estimates at the national level and for 12 Indian states most affected by COVID‐19 are presented. Daily case rates ranged from 0.03 to 285.60/10 million people across 7 discrete periods in India. From 18 May to 31 July 2020, the NCT of Delhi had the highest case rate (999/10 million people/day), whereas Madhya Pradesh had the lowest (49/10 million/day). Average Rt was 1.99 (95% CI 1.93–2.06) and 1.39 (95% CI 1.38–1.40) for the entirety of India during the period from 22 March 2020 to 17 May 2020 and from 18 May 2020 to 31 July 2020, respectively. Median mobility in India decreased in all contact domains during the period from 22 March 2020 to 17 May 2020, with the lowest being 21% in retail/recreation, except home which increased to 129% compared to the 100% baseline value. Median mobility in the ‘Grocery and Pharmacy’ returned to levels observed before 22 March 2020 in Unlock 1 and 2, and the enhanced mobility in the Pharmacy sector needs to be investigated. The Indian government imposed strict contact mitigation, followed by a phased relaxation, which slowed the spread of COVID‐19 epidemic progression in India. The identified daily COVID‐19 case rates and Rt will aid national and state governments in formulating ongoing COVID‐19 containment plans. Furthermore, these findings may inform COVID‐19 public health policy in developing countries with similar settings to India.

Keywords: COVID‐19, epidemic dynamics, India, public health interventions

1. INTRODUCTION

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) was declared a pandemic by the WHO on 11 March 2020 (WHO, 2020c). This novel infection, caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2), was first reported in Wuhan, China (Zhou et al., 2020), and is the seventh coronavirus known to infect humans (Andersen et al., 2020). As of 30 August 2020, 24,854,140 cases and 838,924 deaths have been reported worldwide (WHO, 2020b). As data collection efforts and testing protocols continue to evolve, these values likely represent a considerable underestimation of total cases and deaths (Richterich, 2020).

The successful impact of public health interventions on COVID‐19 in Wuhan, China, which included social distancing, isolating infected individuals and quarantine supported implementation of similar measures in many other countries (Anderson et al., 2020). For instance, mass‐gathering events have been reported to pose a considerable public health risk and therefore have been avoided in most COVID‐19‐infected countries. Modelling studies suggest that, whereas highly effective contact tracing coupled with case isolation has potential to contain COVID‐19 outbreaks, proper containment likely requires additional measures, for example contact mitigation (Hellewell et al., 2020). However, with recent declines in COVID‐19 case volume, many countries are turning to contact mitigation relaxation plans.

The federal government in India responded swiftly to COVID‐19 by implementing staged lockdown periods across the country; strict, intense contact mitigation was implemented initially, followed by phased relaxation as deemed appropriate. As India is among the world's most populated countries, COVID‐19 has considerable potential for widespread morbidity and mortality and containment has global implications. Evaluating impacts of COVID‐19 public health interventions is important to inform future effective public health and social interventions. The effective reproduction number (Rt ), which captures time‐dependent variations in the transmission potential of an infectious disease in a given population, is an important parameter for evaluating effectiveness of public health interventions (Pan et al., 2020). Although epidemiological characteristics of COVID‐19, including rates of confirmed cases and Rt , were investigated in Wuhan, China, across various periods of social distancing interventions (Pan et al., 2020), the impact of government‐imposed mitigation strategies on transmission dynamics in India remains unknown. In this study, we estimated the laboratory‐confirmed daily case rate and Rt of the COVID‐19 epidemic in key lockdown periods in India. Estimates presented here will provide key information for ongoing COVID‐19 prevention and control in India.

2. METHODS

2.1. Source of data

2.1.1. Time series data

Indian COVID‐19 time series incidence and fatality data were extracted on 15 August 2020 using the WHO coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) situation reports 10–193 (WHO, 2020a). We selected data from states/union territories where > 200 COVID‐19 cases (positive/recovered/deceased) had been recorded before 22 May 2020, which consisted of data from 17 states/union territories. Time series data on daily counts were not available for 5 states (Gujarat, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, Jammu and Kashmir, and Bihar); therefore, these were excluded from the study. Time series data for the remaining 12 states were extracted from official state Health and Family Welfare department websites (Appendix S1).

2.1.2. Census data

The official human population 2011 Indian census data were used (COI, 2011a). In 2014, the state of Andhra Pradesh was bifurcated into two states, Telangana and residuary Andhra Pradesh. As separate census data for these states were not available, combined results for Andhra Pradesh (Telangana and residuary Andhra Pradesh) are presented.

2.2. Case definitions

Cases were defined based on laboratory confirmation using throat/nasal swab real‐time reverse transcriptase‐polymerase chain reaction (RT‐PCR) assay, the diagnostic test recommended by the Indian Council for Medical Research (ICMR) for the diagnosis of COVID‐19 (ICMR, 2020b). Only laboratory‐confirmed cases were included in the analyses. The ICMR strategy for COVID‐19 testing included all symptomatic individuals who had undertaken international travel in the last 14 days, all symptomatic contacts of laboratory conformed cases, all symptomatic health care workers, all patients with severe acute respiratory illness (fever and cough and/or shortness of breath), and asymptomatic direct and high‐risk contacts of a confirmed cases (ICMR, 2020b). For hotspots/clusters, large migration gatherings and evacuation centres, all persons having fever, cough, sore throat or runny nose were recommended to be tested (ICMR, 2020b).

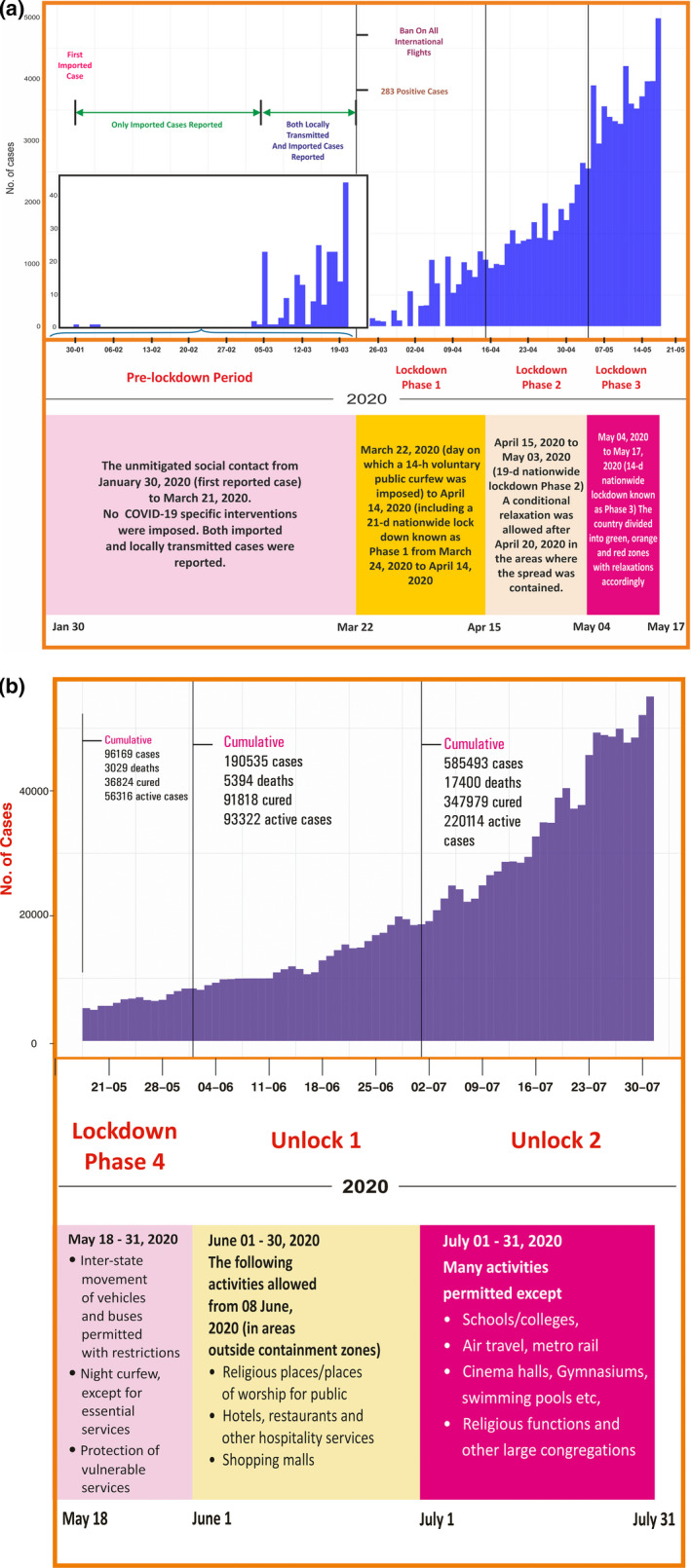

2.3. Classification of 7 time periods

The study period comprised an initial unmitigated social contact period when temperature screening was imposed at international checkpoints. This was followed by strict contact mitigation and then phased relaxation. Dynamics of the COVID‐19 epidemic were evaluated in discrete periods, according to changes in government policies (Figure 1). Based on these government‐imposed interventions, we classified 7 periods for analysis, including the following: 1) Pre‐lockdown; Unmitigated social contact from 30 January 2020 (first reported case) to 21 March 2020 during which no COVID‐19‐specific interventions were imposed, and both imported, and locally transmitted cases were reported; 2) Lockdown Phase 1; 22 March 2020 (day on which a 14 hr voluntary public curfew was imposed) to 14 April 2020 (including a 21 day nationwide lockdown from 24 March 2020 to 14 April 2020); 3) Lockdown Phase 2; 15 April 2020 to 03 May 2020 (19 day nationwide lockdown); 4) Lockdown Phase 3; 4 May 2020 to 17 May 2020 (14 day nationwide lockdown); 5) Lockdown Phase 4; 18 May 2020 to 31 May 2020; 6) Unlock 1; 1 June to 30 June 2020; and 7) Unlock 2; 1 – 31 July 2020. Detailed restrictions during nationwide Lockdowns Phases 1 to 4, and Unlock 1 – 2 are available at the website of the Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India (https://www.mha.gov.in/media/whats‐new, accessed on 17 August 2020). Briefly, conditional relaxation was allowed in Lockdown Phase 2 after 20 April 2020 in areas where spread was contained. During Lockdown Phase 3, the Indian government divided the country into green zones (districts with no confirmed case in last 21 d), orange zones (districts that were in neither red nor green zones) and red zones (hotspot districts), with relaxations accordingly. Seven discrete periods were divided into two broader categories: Public health interventions 1 (30 January to 17 May 2020) and Public health interventions 2 (18 May to 31 July 2020), and compared accordingly.

Figure 1.

(a) Incidence of COVID‐19 cases, key events and public health interventions across 4 periods in India. Detailed information relating to restrictions and relaxations during the nationwide lockdowns Phase 1 to 3 are available at the website of the Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India (https://www.mha.gov.in/media/whats‐new). (b) Incidence of COVID‐19 cases, key events and public health interventions across 3 periods in India. Detailed information relating to restrictions and relaxations during the nationwide lockdown Phase 4, Unlock 1 and 2 are available at the website of the Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India (https://www.mha.gov.in/media/whats‐new) [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

2.4. Mobility index

A domain‐specific mobility index was constructed using India's mobility report (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA) (Google, 2020). These data are publicly available from Google and represent the per cent change from baseline mobility within various domains (retail and recreation mobility, grocery and pharmacy mobility, parks mobility, transit stations mobility, workplace mobility and residential mobility) according to cell phone‐user geolocation data. As data were available as per cent mobility change from the baseline value, we considered 100 as the baseline value; therefore, 100 was added to each value to transform the raw Google data to domain‐specific mobility per day. The domain‐specific mobility index was constructed for the country and 12 Indian states.

2.5. Outcomes

Daily rate of laboratory‐confirmed cases per 10 million people per day was estimated across periods for the 12 Indian states and for the country. We used number of cases in each period, divided by the number of days in each period (52, 24, 19, 14, 14, 30, and 31d, respectively) and the total population of the selected region as per the 2011 census (COI, 2011a). The Rt was calculated to determine the transmission of SARS‐CoV‐2 in each of the 6 periods. The Rt was calculated based on the method developed by Cori et al. (Cori et al., 2013) that is able to detect changes in the Rt following public health interventions.

2.6. Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were conducted using R version 3.6.3 (R Development Core Team, http://www.r‐project.org). Epidemic curves were plotted, based on laboratory diagnosis date and intervention periods described. Choropleth maps describing geographical distributions of COVID‐19 case rates for the country and 12 Indian states through the 7 intervention periods were generated.

The Rt for each of 12 Indian states, as well as for the entire country, were calculated as per the method developed by Cori et al. (Cori et al., 2013). This method estimates Rt from the incidence time series and incorporates uncertainty in the distribution of the serial interval. We used the daily number of reported COVID‐19 cases from the above‐mentioned official data sources. The serial interval required to estimate Rt (mean = 7.5 d, SD = 3.4 d) was derived from previous studies in Wuhan, China (Li et al., 2020; Pan et al., 2020). The serial interval was considered constant across all periods. A 5‐day moving average was used to estimate Rt and its 95% credible interval on each day.

The first locally transmitted COVID‐19 case is thought to have occurred in India on 5 March 2020 and the Indian government closed international borders and air travel on 22 March 2020; therefore, March 22 was taken as our first day of Rt estimation. This allows for a complete serial interval from the first locally transmitted case, and enables presumption of a closed population and ensures an appropriate total case count (Cori et al., 2013). Therefore, the Rt was estimated from 1) March 22 to May 24; and 2) May 18 to August 7; and results of the initial burn‐in period (when both imported and locally transmitted cases were reported; Figure 1a) are not presented. For the 12 states, Rt was estimated for the whole period, but was presented from the day when 50 cumulative cases were reported (or from March 22 onwards, whichever is later) given the limited diagnostic cases and capacity in the preliminary period. Although country and state populations were assumed to be closed from March 22 onwards, the possibility of imported cases being reported cannot be ruled out at the state level.

Descriptive analyses to report changes in mobility index were conducted according to key intervention periods.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Epidemic curve

The COVID‐19 epidemic started in India on 30 January 2020 with the first imported case detected (MHFW, 2020b). Within 8 months, the country reported 78,761 new cases; 3,542,733 cumulative cases; and 63,498 cumulative deaths on 30 August 2020 (WHO, 2020b). By this time, COVID‐19 had been reported from 35 of the 36 states/union territories of the country (MHFW, 2020a).

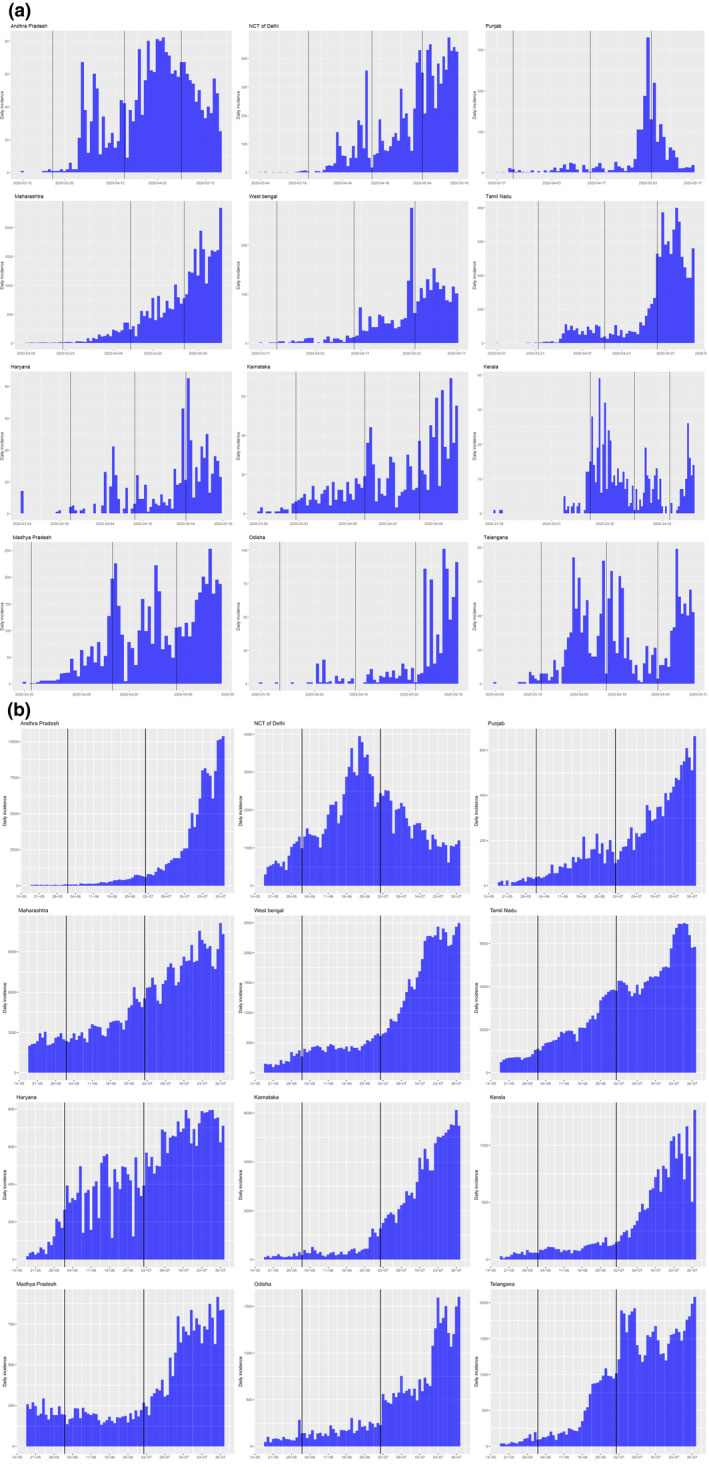

Daily number of cases were minimal during the Pre‐lockdown Period but continued to rise in subsequent Lockdown (Phases 1–4) and Unlock (1 and 2) periods, with approximately 5,000 cases/day reported at the end of Lockdown Phase 3 (Figure 1a) and 55,000 cases/day reported at the end of Unlock 2 (Figure 1b). There were obvious differences among states in epidemic progression (Figure 2a and 2b).

Figure 2.

(a) Incidence of COVID‐19 cases across 4 periods in 12 states of India. Vertical bars illustrate 4 periods related to public health interventions in India. Discrete periods: (1) Pre‐lockdown—30 January 2020 to 21 March 2020; 2) Lockdown Phase 1—22 March 2020 to 14 April 2020; 3) Lockdown Phase 2—15 April 2020 to 3 May 2020 and 4) Lockdown Phase 3—4 May 2020 to 17 May 2020. (b) Incidence of COVID‐19 cases across 3 periods in 12 states of India. Vertical bars illustrate 3 periods related to public health interventions in India. Discrete periods: 4) Lockdown Phase 4—18–31 May 2020; 5) Unlock 1— 01–30 June 2020; 6) Unlock 2—01–31 July 2020 [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

As of 17 May 2020, the state of Maharashtra had the highest number of cumulative cases (n = 33,043) followed by Tamil Nadu (n = 11,001) and NCT of Delhi (n = 9,751). Kerala reported the highest number of cases per day during Lockdown Phase 1. The highest number of cases/day was reported in Andhra Pradesh, Punjab and West Bengal during Lockdown Phase 2. Over 1,500 cases/day were reported from Maharashtra at the end of Lockdown Phase 3, followed by NCT of Delhi and Tamil Nadu where close to 400 cases/d were reported (Figure 2a).

As of 31 July 2020, the state of Maharashtra had the highest number of cumulative cases (n = 411,798) followed by Tamil Nadu (n = 239,978) and NCT of Delhi (n = 134,403) (Figure 2b).

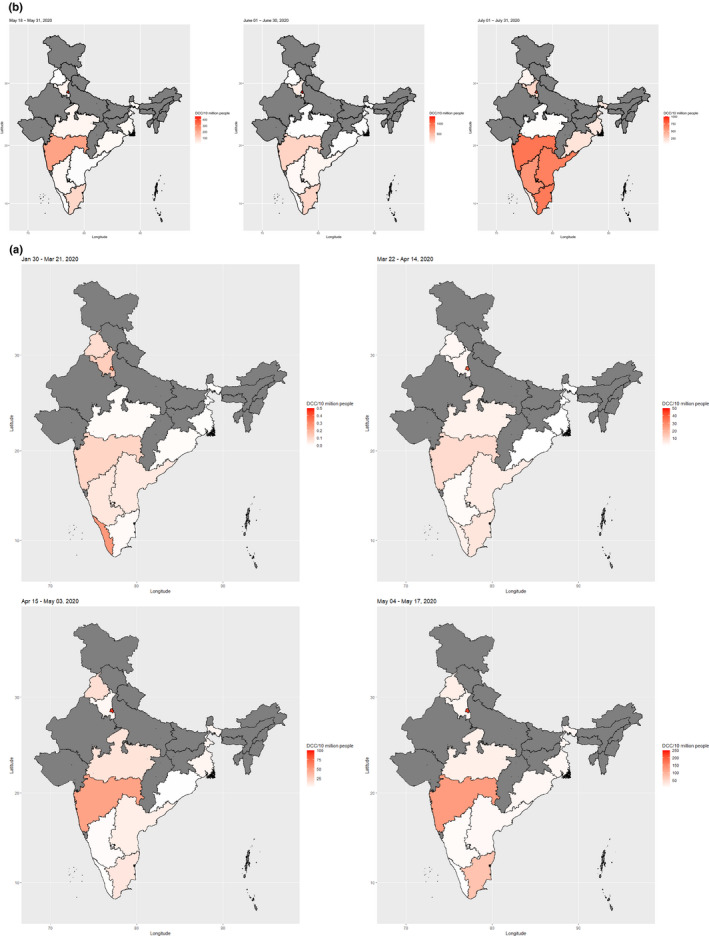

3.2. Case rate/10 million people/day

The case rate was 0.03, 3.50, 12.87, 30.05, 53.81, 105.90 and 285.60 per 10 million people per day across the 7 discrete periods in India. Overall, the case rate was 7 per 10 million people per day from 30 January 2020 to 17 May 2020. The case rate was 170 per 10 million people per day from 18 May to 31 July 2020. The rate of increase was highest from Pre‐lockdown Period through Lockdown Phase 1 and lowest from Lockdown Phase 3 through Phase 4 in the country (Table 1). There were large differences in incidence rates across 12 Indian states and across time periods (Table 1; Figure 3a and 3b). Among all states, the highest case rate was 53 per 10 million people per day from NCT of Delhi, whereas the lowest case rate was 2 per 10 million people per day from Kerala from 30 January 2020 to 17 May 2020 (Table 1). Among all states, the highest case rate was 999 per 10 million people per day from NCT of Delhi, whereas the lowest case rate was 49 per 10 million people per day from Madhya Pradesh from 18 May 2020 to 31 July 2020 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Daily incidence of COVID‐19 cases during the 7 Periods in 12 states of India

| Parameter | India | Andhra Pradesh combined a | NCT of Delhi | Punjab | Maharashtra | West Bengal | Tamil Nadu | Haryana | Karnataka | Kerala | Madhya Pradesh | Odisha |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human population (× 1,000) | 1,210,855 | 84,581 | 16,788 | 27,743 | 112,374 | 91,276 | 72,147 | 25,351 | 61,095 | 33,406 | 72,627 | 41,974 |

| Pre‐lockdown (Jan 30 to Mar 21, 2020) | ||||||||||||

| COVID−19 cases | 218 | 26 | 27 | 13 | 64 | 3 | 6 | 17 | 20 | 46 | 4 | 2 |

| Case rate/10 million people/d | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.31 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.13 | 0.06 | 0.26 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Lockdown Phase 1 (22 Mar to 14 Apr 2020) | ||||||||||||

| COVID−19 cases | 10,168 | 1,101 | 1,534 | 171 | 2,620 | 124 | 1,198 | 167 | 240 | 335 | 737 | 58 |

| Case rate/10 million people/d | 3.50 | 5.42 | 38.07 | 2.57 | 9.71 | 0.57 | 6.92 | 2.74 | 1.64 | 4.18 | 4.23 | 0.58 |

| Lockdown Phase 2 (15 Apr to 03 May 2020) | ||||||||||||

| COVID19 cases | 29,617 | 1,538 | 2,984 | 918 | 10,295 | 1,071 | 1,819 | 258 | 354 | 113 | 2,096 | 103 |

| Case rate/10 million people/d | 12.87 | 9.57 | 93.55 | 17.42 | 48.22 | 6.18 | 13.27 | 5.36 | 3.05 | 1.78 | 15.19 | 1.29 |

| Lockdown Phase 3 (04 May to 17 May 2020) | ||||||||||||

| COVID−19 cases | 50,947 | 1,143 | 5,206 | 876 | 20,064 | 1,479 | 7,978 | 468 | 533 | 102 | 2,140 | 659 |

| Case rate/10 million people/d | 30.05 | 9.65 | 221.50 | 22.55 | 127.53 | 11.57 | 78.99 | 13.19 | 6.23 | 2.18 | 21.05 | 11.21 |

| Overall (30 Jan to 17 May 2020) | ||||||||||||

| COVID−19 cases | 90,950 | 3,808 | 9,751 | 1978 | 33,043 | 2,677 | 11,001 | 910 | 1,147 | 596 | 4,977 | 822 |

| Case rate/10 million people/d |

6.89 |

4.13 | 53.29 | 6.54 | 26.98 | 2.69 | 13.99 | 3.29 | 1.72 | 1.64 | 6.29 | 1.80 |

| Lockdown Phase 4 (18 to 31 May 2020) | ||||||||||||

| COVID−19 cases | 91,216 | 1918 | 10,090 | 299 | 34,251 | 2,824 | 9,897 | 1,183 | 2074 | 667 | 3,114 | 1,276 |

| Case rate/10 million people/d | 53.81 | 16.20 | 429.30 | 7.70 | 217.71 | 22.10 | 97.98 | 33.33 | 24.25 | 14.26 | 30.63 | 21.71 |

| Unlock 1 (01 to 30 June 2020) | ||||||||||||

| COVID−19 cases | 384,697 | 22,801 | 67,516 | 3,305 | 107,130 | 13,058 | 66,005 | 11,138 | 12,021 | 3,172 | 5,504 | 5,212 |

| Case rate/10 million people/d | 105.90 | 89.86 | 1,340.57 | 39.71 | 317.78 | 47.69 | 304.96 | 146.45 | 65.59 | 31.65 | 25.26 | 41.39 |

| Unlock 2 (01 to 31 July 2020) | ||||||||||||

| COVID−19 cases | 1,072,030 | 174,282 | 48,238 | 10,551 | 247,357 | 51,629 | 153,709 | 20,417 | 108,873 | 19,201 | 18,214 | 26,163 |

| Case rate/10 million people/d | 285.60 | 664.69 | 926.89 | 122.68 | 710.06 | 182.46 | 687.26 | 259.79 | 574.84 | 185.41 | 80.90 | 201.07 |

| Overall (18 May 18 to 31 July 2020) | ||||||||||||

| COVID−19 cases | 1,547,943 | 199,001 | 125,844 | 14,155 | 388,738 | 67,511 | 229,611 | 32,738 | 122,968 | 23,040 | 26,832 | 32,651 |

| Case rate/10 million people/d | 170.45 | 313.71 | 999.48 | 68.03 | 461.24 | 98.62 | 424.34 | 172.18 | 268.36 | 91.96 | 49.26 | 103.72 |

Residuary Andhra Pradesh and Telangana.

Figure 3.

(a) Geographic distribution of incidence of COVID‐19 cases during the 4 Periods in 12 states of India. Note that combined results of Andhra Pradesh (for 2 states residuary Andhra Pradesh and Telangana) have been presented. DCC represents Daily Confirmed Cases, expressed as number of laboratory‐confirmed cases per 10 million people per day. (b) Geographic distribution of incidence of COVID‐19 cases during the 3 Periods in 12 states of India. Note that combined results of Andhra Pradesh (for 2 states residuary Andhra Pradesh and Telangana) have been presented. DCC represents Daily Confirmed Cases, expressed as number of laboratory‐confirmed cases per 10 million people per day [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

In Lockdown Phase 3, the highest case rate was recorded for NCT of Delhi (222 per 10 million people per day) and the lowest case rate was recorded for Kerala (2.18 per 10 million people per day). The case rate for all states continued to rise despite implementing public health interventions, except Kerala, where case rate decreased from Lockdown Phase 1 to Phase 3 (Figure 3a) and NCT of Delhi, where case rate decreased from Unlock 1 to Unlock 2.

3.3. Effective Reproduction number

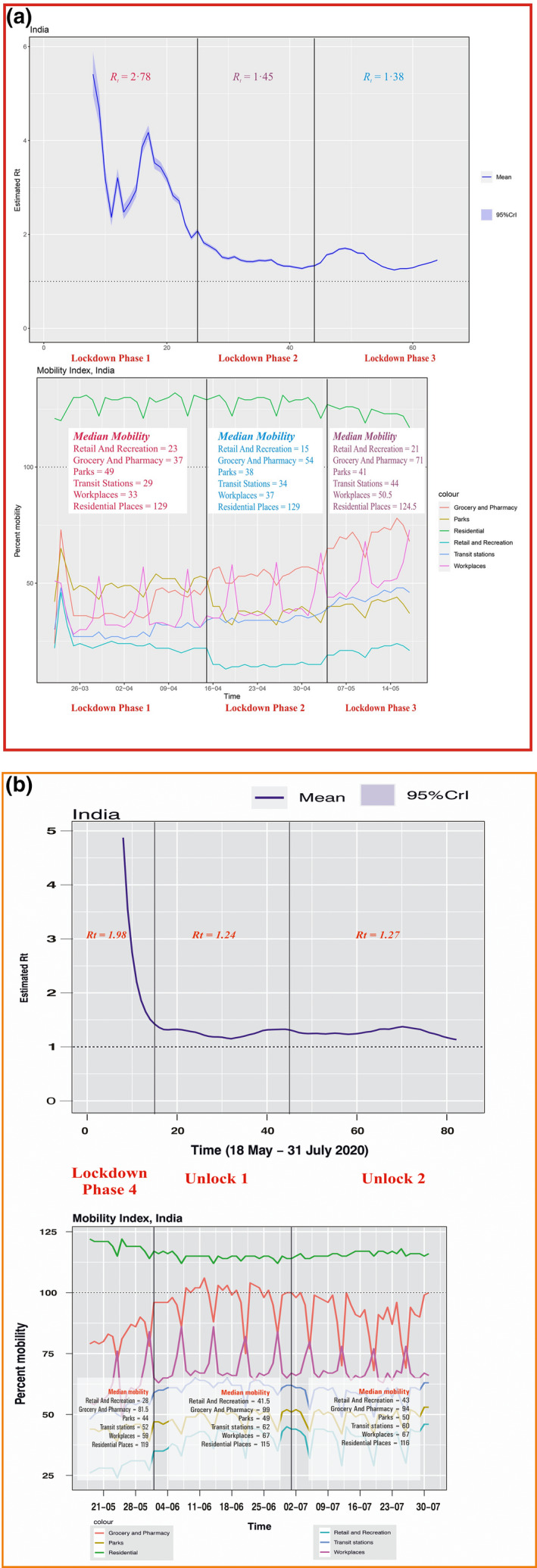

The Rt differed across all 7 periods. Average Rt was 1.99 (95% CI 1.93–2.06) for the entirety of India during the period from 22 March 2020 to 17 May 2020. The Rt was 2.78 (95% CI 2.65–2.91) in Lockdown Phase 1, 1.45 (95% 1.42–1.47) in Phase 2 and 1.38 (95% CI 1.36–1.40) in Phase 3. Therefore, the Rt had a consistent decreasing trend in India from Periods 2 through 4 (Figure 4a, Appendix p 3–6).

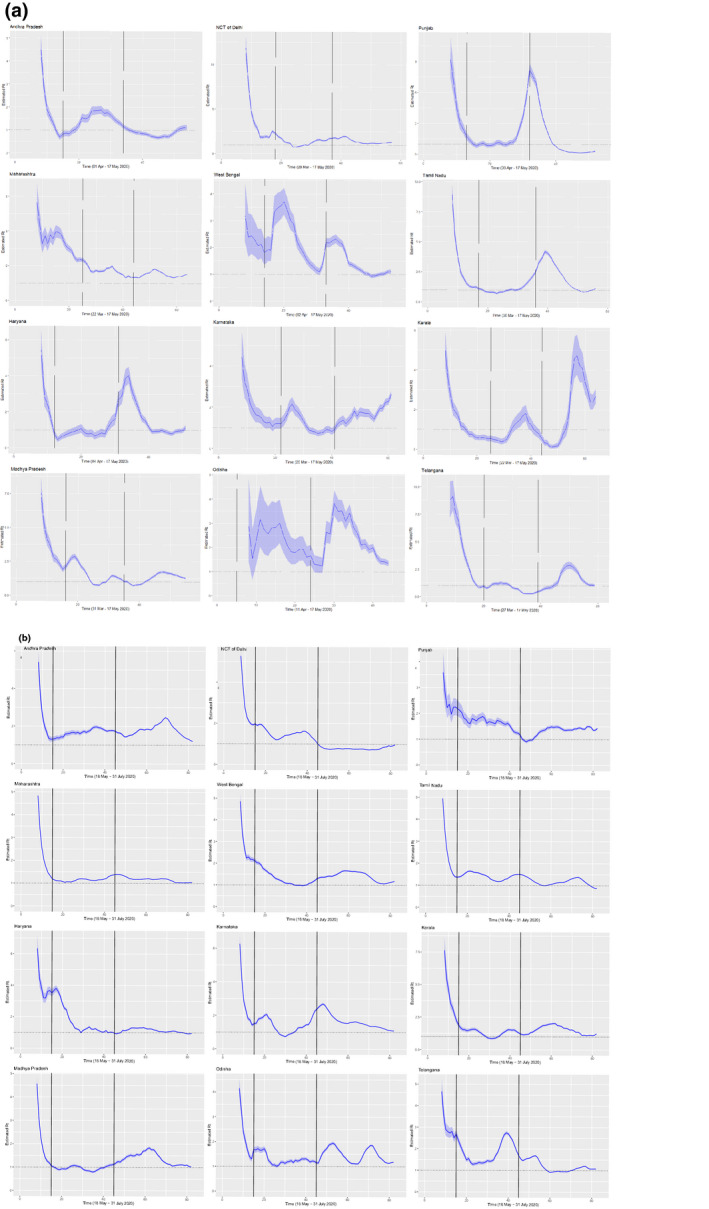

Figure 4.

(a) The effective reproduction number (Rt ) for the laboratory‐confirmed COVID‐19 cases and the domain‐specific mobility of Indian citizens across 3 discrete periods (Lockdown Phases 1–3) in India. Vertical bars illustrate 3 discrete periods related to public health interventions in India. Discrete periods: 2) Lockdown Phase 1—22 March 2020 to 14 April 2020; 3) Lockdown Phase 2—15 April 2020 to 3 May 2020 and 4) Lockdown Phase 3—4 May 2020 to 17 May 2020. Note that 100 was considered as a baseline mobility value when no interventions were imposed. (b) The effective reproduction number (Rt ) for the laboratory‐confirmed COVID‐19 cases and the domain‐specific mobility of Indian citizens across 3 discrete periods (Lockdown Phase 4, Unlock 1 and 2) in India. Vertical bars illustrate 3 discrete periods related to public health interventions in India. Discrete periods: 5) Lockdown Phase 4—18–31 May 2020; 6) Unlock 1—01–30 June 2020 and 7) Unlock 2—1–31 July 2020. Note that 100 was considered as a baseline mobility value when no interventions were imposed [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Average Rt was 1.39 (95% CI 1.38–1.40) for the entirety of India during the period from 18 May 2020 to 31 July 2020. The Rt was 1.98 (95% CI 1.96–2.00) in Lockdown Phase 4, 1.24 (95% 1.23–1.25) in Unlock 1 and 1.27 (95% CI 1.26–1.27) in Unlock 2. Therefore, the Rt had a decreasing trend in India from Lockdown Phase 4 to Unlock 1 but did not change much from Unlock 1 to Unlock 2 and remained on average > 1 (Figure 4b, Appendix p 3–6).

Strong geographic differences were identified in Rt across discrete periods in the country. For example, Rt was > 2 for Maharashtra (2.16), Odisha (2.3) and Punjab state of India (2.15) from 30 January 2020 to 17 May 2020. The Rt was > 1.5 for NCT of Delhi (1.92), Karnataka (1.58), Madhya Pradesh (1.81), Tamil Nadu (1.91), Telangana (1.91) and West Bengal (1.92) state from 30 January 2020 to 17 May 2020. The Rt was < 1.5 for Kerala (1.48), Haryana (1.48) and Andhra Pradesh (1.27) from 30 January 2020 to 17 May 2020 (Figure 5a; Appendix 7–53).

Figure 5.

(a) The effective reproduction number (Rt ) for laboratory‐confirmed COVID‐19 cases across 3 discrete periods (Periods 2–4) in 12 states of India. Vertical bars illustrate 3 discrete periods related to public health interventions in India. Discrete periods: 2) Lockdown Phase 1—22 March 2020 to 14 April 2020; 3) Lockdown Phase 2—15 April 2020 to 3 May 2020 and 4) Lockdown Phase 3—4 May 2020 to 17 May 2020. Note that starting point of the estimation varied in states subject to 50 cumulative cases reported. Overall, most states experienced a consistently decreasing trend from Lockdown Phases 1 through 3, respectively. (b) The effective reproduction number (Rt ) for laboratory‐confirmed COVID‐19 cases across 3 discrete periods (Periods 5–7) in 12 states of India. Vertical bars illustrate 3 discrete periods related to public health interventions in India. Discrete periods: 5) Lockdown Phase 4—18–31 May 2020; 6) Unlock 1—01 –30 June 2020 and 7) Unlock 2—1–31 July 2020. Overall, most states experienced a consistently decreasing trend from Lockdown Phases 4 through Unlock 2, respectively [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

The Rt was > 1 for all states and the entirety of India during the period from 18 May 2020 to 31 July 2020 except NCT of Delhi where Rt was 0.79 (95% CI 0.77–0.81) in Unlock 2 (Figure 5b; Appendix 7–53).

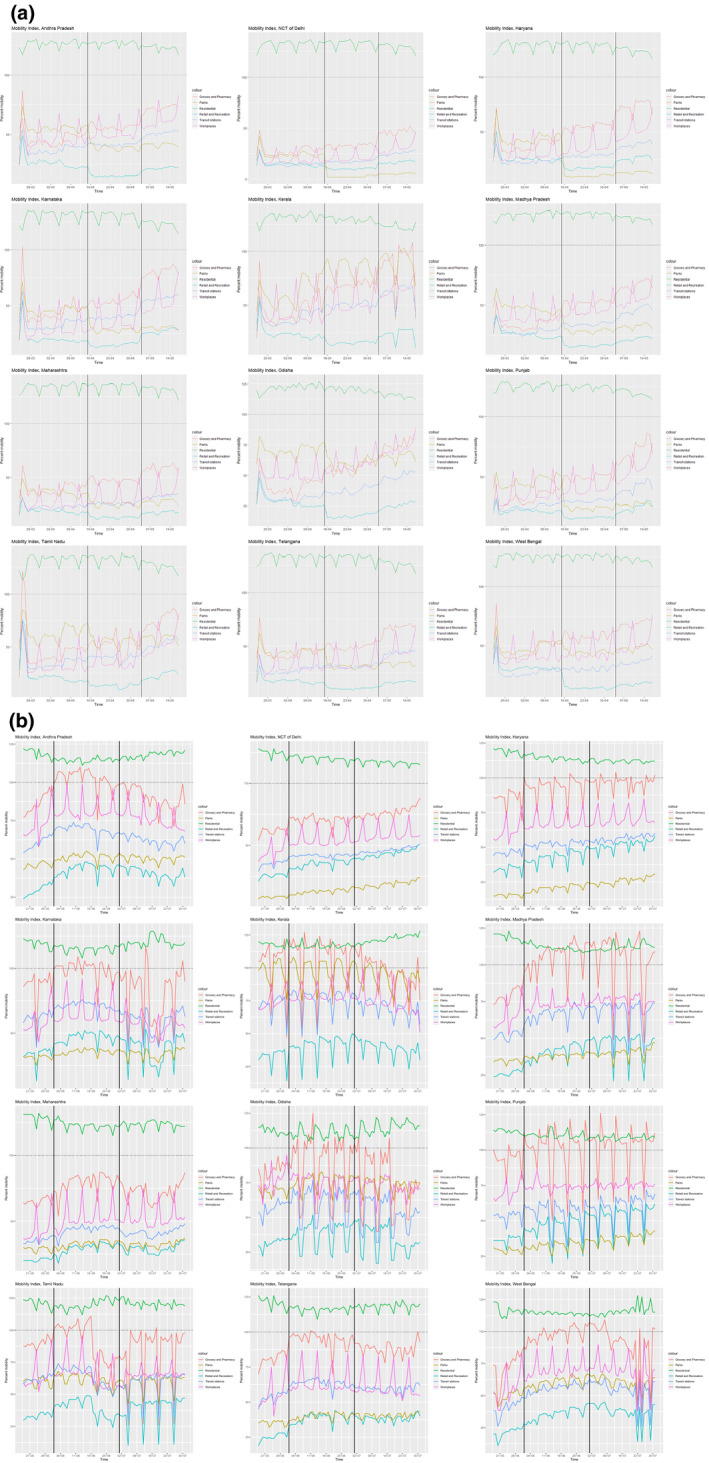

3.4. Mobility index

Median mobility was 21% for retail and recreation, 53% at the grocery and pharmacy, 42% at parks, 34% at transit stations, 38% at workplaces and 129% at residential places from 22 March 2020 to 17 May 2020 (Table 2). Mobility at grocery and pharmacy (median 37%), transit stations (median 29%) and workplaces (median 33%) was lowest from 22 March 2020 to 14 April 2020, during Lockdown Phase 1 (Figure 4a). Interestingly, mobility for retail and recreation (median 15%) and parks (median 38%) was lowest from 15 April 2020 to 3 May 2020, during Lockdown Phase 2 (representing relaxation). Note that these values were derived in comparison to a 100% baseline mobility in the country/state value when no such interventions were imposed.

Table 2.

Domain‐specific mobility in the country and 12 Indian states during key intervention periods. Note that a 100% baseline mobility was considered when no interventions were imposed

| Country/State | Mobility activity | Overall (22 March to 17 May 2020) | Lockdown Phase 1 (22 March to 14 April 2020) | Lockdown Phase 2 (15 April to 03 May 2020) | Lockdown Phase 3 (04 May to 17 May 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (95% CI) | Median (95% CI) | Median (95% CI) | Median (95% CI) | ||

| India | Retail and recreation | 21 (13–46) | 23 (20–46) | 15 (13–22) | 21 (18–24) |

| Grocery and pharmacy | 53 (24–78) | 37 (24–73) | 54 (49–57) | 71 (61–78) | |

| Parks | 42 (32–65) | 49 (42–65) | 38 (32–52) | 41 (35–44) | |

| Transit stations | 34 (26–48) | 29 (26–48) | 34 (33–37) | 44 (39–48) | |

| Workplaces | 38 (28–73) | 33 (28–57) | 37 (35–63) | 50 (44–73) | |

| Residential | 129 (117–132) | 129.5 (120–132) | 129 (121–131) | 124.5 (117–27) | |

| Andhra Pradesh | Retail and recreation | 22 (14–49) | 25.5 (21–49) | 15 (14–23) | 21 (19–23) |

| Grocery and pharmacy | 55 (24–87) | 44 (24–87) | 56 (52–61) | 72 (65–75) | |

| Parks | 42 (35–74) | 55 (45–74) | 39 (35–58) | 42 (38–43) | |

| Transit stations | 41 (32–54) | 37 (32–54) | 42 (39–44) | 51 (46–53) | |

| Workplaces | 49 (33–83) | 44 (33–68) | 49 (46–72) | 60.5 (55–83) | |

| Residential | 126 (117–130) | 127 (117–130) | 127 (121–129) | 124 (117–126) | |

| NCT of Delhi | Retail and recreation | 14 (9–29) | 14 (11–29) | 10 (9–13) | 17 (15–19) |

| Grocery and pharmacy | 33 (17–52) | 26 (17–48) | 34 (29–36) | 46(42–52) | |

| Parks | 6 (2–42) | 23 (21–42) | 2 (2–24) | 5 (4–6) | |

| Transit stations | 17 (12–29) | 14 (12–26) | 17 (16–20) | 25 (22–29) | |

| Workplaces | 20 (15–46) | 18 (15–33) | 19 (18–33) | 30 (23–46) | |

| Residential | 133 (121–137) | 134 (121–133) | 135 (124–137) | 130 (121–133) | |

| Haryana | Retail and recreation | 24 (15–51) | 25 (22–51) | 17 (15–24) | 25 (21–29) |

| Grocery and pharmacy | 53 (23–79) | 35 (23–72) | 55 (46–59) | 73 (60–79) | |

| Parks | 14 (9–70) | 42 (38–70) | 10 (9–45) | 13 (11–14) | |

| Transit stations | 27 (20–43) | 24 (20–40) | 28 (26–30) | 38 (33–43) | |

| Workplaces | 34 (24–72) | 28 (24–53) | 34 (30–61) | 50 (41–72) | |

| Residential | 129 (116–134) | 130 (120–134) | 130 (120–133) | 124 (116–127) | |

| Karnataka | Retail and recreation | 19 (12–55) | 19 (17–55) | 14 (12–19) | 27 (24–30) |

| Grocery and pharmacy | 52 (19–103) | 40.5 (19–103) | 54 (48–63) | 80.5 (73–87) | |

| Parks | 31 (25–72) | 45 (40–72) | 29 (25–48) | 31 (27–32) | |

| Transit stations | 39 (28–63) | 31 (28–63) | 39 (37–46) | 56.5 (53–60) | |

| Workplaces | 32 (19–80) | 26 (19–56) | 32 (28–66) | 49 (43–80) | |

| Residential | 130 (114–135) | 133 (117–135) | 132 (119–134) | 123.5 (114–126) | |

| Kerala | Retail and recreation | 21 (10–54) | 22 (17–54) | 15 (12–21) | 24 (10–28) |

| Grocery and pharmacy | 66 (19–108) | 40 (19–91) | 68 (59–75) | 94 (36–108) | |

| Parks | 79 (44–103) | 59 (44–80) | 87 (68–94) | 93 (67–103) | |

| Transit stations | 48 (30–69) | 34 (33–58) | 50 (45–55) | 63 (40–69) | |

| Workplaces | 48 (32–86) | 37 (32–80) | 48 (40–86) | 64 (57–81) | |

| Residential | 129 (119–138) | 133 (119–138) | 130 (125–133) | 123 (119–128) | |

| Madhya Pradesh | Retail and recreation | 22 (14–42) | 25 (22–42) | 16 (14–24) | 21 (18–24) |

| Grocery and pharmacy | 51 (26–72) | 32 (26–52) | 52 (45–55) | 65 (59–72) | |

| Parks | 33 (25–64) | 47 (41–64) | 28 (25–46) | 32 (28–35) | |

| Transit stations | 34 (25–51) | 28 (25–41) | 34 (32–36) | 45 (38–51) | |

| Workplaces | 43 (35–75) | 38 (35–61) | 43 (40–65) | 53 (47–75) | |

| Residential | 126 (117–129) | 126 (118–129) | 127 (120–128) | 123 (117–125) | |

| Maharashtra | Retail and recreation | 17 (11–31) | 18 (14–31) | 13 (11–18) | 17 (15–19) |

| Grocery and pharmacy | 46 (16–63) | 37 (16–61) | 47 (41–51) | 59 (50–63) | |

| Parks | 29 (21–49) | 36 (29–49) | 26 (21–36) | 28 (23–30) | |

| Transit stations | 25 (19–35) | 22 (19–31) | 25 (24–28 | 3 (29–35) | |

| Workplaces | 27 (19–59) | 24 (19–45) | 27 (23–50) | 33 (29–59) | |

| Residential | 135 (121–139) | 135 (125–139) | 136 (125–138) | 132 (121–134) | |

| Odisha | Retail and recreation | 25 (14–48) | 28 (24–48) | 16 (14–26) | 25 (21–29) |

| Grocery and pharmacy | 54 (27–82) | 39.5 (27–64) | 56 (49–64) | 74 (65–82) | |

| Parks | 67 (51–82) | 70 (59–82) | 60 (51–77) | 67 (57–70) | |

| Transit stations | 36 (27–54) | 31 (27–54) | 37 (34–43) | 48 (42–54) | |

| Workplaces | 57 (46–89) | 48 (46–68) | 57 (51–78) | 69 (64–89) | |

| Residential | 120 (112–127) | 122.5 (113–127) | 121 (117–123) | 115 (112–119) | |

| Punjab | Retail and recreation | 21 (15–31) | 21.5 (19–31) | 16 (15–22) | 24 (19–31) |

| Grocery and pharmacy | 47 (23–86) | 31 (23–44) | 51 (43–54) | 68 (57–86) | |

| Parks | 28 (21–54) | 44 (40–54) | 25 (21–50) | 27 (24–30) | |

| Transit stations | 29 (21–49) | 25 (21–33) | 30 (29–32) | 39.5 (34–49) | |

| Workplaces | 39 (26–78) | 33 (26–57) | 39 (36–63) | 55 (44–78) | |

| Residential | 125 (114–129) | 126 (119–129) | 125 (119–127) | 118.5 (114–123) | |

| Tamil Nadu | Retail and recreation | 19 (9–74) | 21 (17–74) | 14 (9–18) | 22.5 (18–28) |

| Grocery and pharmacy | 50 (21–121) | 39 (21–121) | 53 (30–68) | 74 (64–86) | |

| Parks | 59 (45–85) | 61 (48–85) | 57 (45–72) | 59 (50–61) | |

| Transit stations | 40 (29–76) | 32 (29–76) | 40 (33–44) | 51 (44–60) | |

| Workplaces | 35 (25–81) | 29 (25–71) | 33 (29–65) | 52 (40–81) | |

| Residential | 132 (113–139) | 133 (113–137) | 134 (122–139) | 126 (117–132) | |

| Telangana | Retail and recreation | 16 (9–32) | 18 (14–32) | 11 (9–16) | 17 (12–18) |

| Grocery and pharmacy | 48 (17–77) | 41 (17–77) | 50 (45–55) | 68 (54–71) | |

| Parks | 35 (28–62) | 44 (38–62) | 32 (28–48) | 35 (30–36) | |

| Transit stations | 30 (24–46 | 26 (24–42) | 31 (29–35) | 44 (33–46) | |

| Workplaces | 32 (21–68) | 29 (21–54) | 31 (29–58) | 43 (35–68) | |

| Residential | 132 (117–137) | 133 (123–137) | 133 (121–136) | 126 (117–132) | |

| West Bengal | Retail and recreation | 18 (12–58) | 31 (28–58) | 14 (12–28) | 17 (15–19) |

| Grocery and pharmacy | 55 (37–86) | 42 (37–86) | 57 (51–63) | 68 (62–73) | |

| Parks | 46 (40–67) | 46 (42–67) | 44 (40–54) | 48 (43–52) | |

| Transit stations | 29 (23–50) | 26 (23–50) | 30 (27–34) | 35 (32–41) | |

| Workplaces | 43 (34–76) | 38 (34–63) | 42 (37–66) | 49 (44–76) | |

| Residential | 125 (116–129) | 126 (116–129) | 126 (120–129) | 122 (116–126) |

The NCT of Delhi had the lowest mobility among the 12 states when compared to 100% baseline value at the retail and recreation (median 14%), grocery and pharmacy (median 33%), parks (median 6%), transit stations (median 17%) and workplaces (median 20%) from 22 March 2020 to 17 May 2020 (Figure 6a; Table 2).

Figure 6.

(a) Domain‐specific mobility of Indian citizens across 3 discrete periods (Periods 2–4) in 12 states of India. Vertical bars illustrate 3 discrete periods related to public health interventions in India. Discrete periods: 2) Lockdown Phase 1—22 March 2020 to 14 April 2020; 3) Lockdown Phase 2—15 April 2020 to 3 May 2020 and 4) Lockdown Phase 3—4 May 2020 to 17 May 2020. Note that 100 was considered as a baseline mobility value when no interventions were imposed. (b) Domain‐specific mobility of Indian citizens across 3 discrete periods (Periods 5–7) in 12 states of India. Vertical bars illustrate 3 discrete periods related to public health interventions in India. Discrete periods: 5) Lockdown Phase 4—18–31 May 2020; 6) Unlock 1—01–30 June 2020 and 7) Unlock 2—1–31 July 2020. Note that 100 was considered as a baseline mobility value when no interventions were imposed [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Median mobility subsequently increased in all the domains except residential during the period from 18 May 2020 to 31 July 2020 as compared to the period from 22 March 2020 to 17 May 2020 (Table 3, Figures 4b and 6b). Median mobility in the ‘Grocery and Pharmacy’ returned to levels observed before 22 March 2020 in Unlock 1 and 2. Median mobility was 41% for retail and recreation, 95% at the grocery and pharmacy, 49% at parks, 60% at transit stations, 67% at workplaces and 115% at residential places from 18 May 2020 to 31 July 2020.

Table 3.

Domain‐specific mobility in the country and 12 Indian states during key intervention periods. Note that a 100% baseline mobility was considered when no interventions were imposed

| Country/State | Mobility activity | Overall (18 May to 31 July 2020) | Lockdown Phase 4 (18 May to 31 May 2020) | Unlock 1 (01 June to 30 June 2020) | Unlock 2 (01 July to 31 July 2020) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (95% CI) | Median (95% CI) | Median (95% CI) | Median (95% CI) | ||

| India | Retail and recreation | 41 (24 – 46) | 28 (24–31) | 41.5 (32–45) | 43 (29–46) |

| Grocery and pharmacy | 95 (68–106) | 81.5 (72–90) | 99 (75–106) | 94 (68–100) | |

| Parks | 49 (39–53) | 44 (39–46) | 49 (42–52) | 50 (42–53) | |

| Transit stations | 60 (48–65) | 52 (48–56) | 62 (53–65) | 60 (49–63) | |

| Workplaces | 67 (49–86) | 59 (49–84) | 67 (63–86) | 67 (63–80) | |

| Residential | 115 (112–122) | 119 (114–122) | 115 (112–117) | 116 (114–118) | |

| Andhra Pradesh | Retail and recreation | 41 (24–48) | 29 (24–35) | 44.5 (32–48) | 40 (32–46) |

| Grocery and pharmacy | 97 (71 – 110) | 84.5 (77–97) | 103.5 (75–110) | 90 (71–100) | |

| Parks | 51 (43 – 55) | 46 (43–49) | 52 (43–55) | 51 (44–54) | |

| Transit stations | 65 (54 – 74) | 60 (54–66) | 70 (55–74) | 62 (55–67) | |

| Workplaces | 78 (58 – 99) | 70 (58–98) | 79 (75–99) | 75 (68–95) | |

| Residential | 117 (111–122) | 120 (113–122) | 115 (111–118) | 118 (114–121) | |

| NCT of Delhi | Retail and recreation | 38 (21–51) | 26 (21–27) | 35 (29–39) | 44 (38–51) |

| Grocery and pharmacy | 72 (54–88) | 63 (54–65) | 71.5 (56–76) | 76 (70–88) | |

| Parks | 14 (7–24) | 8.5 (7–9) | 13 (10–17) | 19 (14–24) | |

| Transit stations | 43 (29–51) | 35.5 (29–38) | 42 (38–43) | 46 (42–51) | |

| Workplaces | 54 (34–75) | 45 (34–64) | 52 (50–73) | 57 (53–75) | |

| Residential | 119 (112–128) | 125.5 (118–128) | 120.5 (113–123) | 117 (112–120) | |

| Haryana | Retail and recreation | 46 (28–58) | 34.5 (28–38) | 44 (32–51) | 52 (42–58) |

| Grocery and pharmacy | 96 (69–104) | 86 (69–92) | 96 (69–103) | 98 (84–104) | |

| Parks | 22 (13–31) | 16 (13–17) | 21 (17–25) | 26 (21–31) | |

| Transit stations | 53 (43–60) | 46 (43–49) | 53 (44–56) | 57 (52–60) | |

| Workplaces | 66 (52–85) | 60 (52–80) | 65 (63–82) | 68 (65–85) | |

| Residential | 113 (110–121) | 119.5 (114–121) | 114 (110–118) | 112 (110–114) | |

| Karnataka | Retail and recreation | 43 (13–53) | 35 (13–38) | 48 (35–52) | 43 (14–53) |

| Grocery and pharmacy | 94 (36–117) | 90 (39–97) | 102 (71–109) | 90 (36–117) | |

| Parks | 35 (25–39) | 32 (25–33) | 36 (30–39) | 36 (26–39) | |

| Transit stations | 66 (36–76) | 63 (39–68) | 72 (59–76) | 63 (36–71) | |

| Workplaces | 60 (43–92) | 55 (43–86) | 61 (59–92) | 57 (43–77) | |

| Residential | 118 (108–129) | 120.5 (113–123) | 116 (108–118) | 120 (113–129) | |

| Kerala | Retail and recreation | 40 (14–50) | 34.5 (14–38) | 43 (15–50) | 40 (23–49) |

| Grocery and pharmacy | 109 (47–127) | 111 (47–122) | 116 (47–127) | 98 (64–118) | |

| Parks | 97 (74–108) | 99 (76–107) | 104 (75–108) | 95 (74–105) | |

| Transit stations | 75 (48–83) | 74 (49–79) | 79.5 (48–83) | 72 (54–80) | |

| Workplaces | 76 (51–99) | 72.5 (68–90) | 77 (75–97) | 72 (51–99) | |

| Residential | 118 (114–128) | 118 (114–122) | 116 (115–123) | 122 (116–128) | |

| Madhya Pradesh | Retail and recreation | 43 (21–53) | 26 (24–29) | 42 (31–49) | 50 (21–53) |

| Grocery and pharmacy | 108 (47–123) | 78 (72–86) | 108 (75–120) | 110 (47–123) | |

| Parks | 39 (30–47) | 35 (31–36) | 38 (33–41) | 40 (30–47) | |

| Transit stations | 68 (36–76) | 52 (47–55) | 68 (54–75) | 72 (36–76) | |

| Workplaces | 73 (52–86) | 62 (52–86) | 72 (67–86) | 76 (65–81) | |

| Residential | 112 (108–123) | 119.5 (114–123) | 111 (108–117) | 111 (109–118) | |

| Maharashtra | Retail and recreation | 29 (18–36) | 20 (19–22) | 31 (18–35) | 29 (24–36) |

| Grocery and pharmacy | 74 (54–87) | 65 (60–70) | 82 (54–87) | 72 (60–87) | |

| Parks | 32 (25–37) | 30 (25–31) | 33 (27–36) | 33 (27–37) | |

| Transit stations | 42 (31–48) | 35 (32–39) | 44.5 (31–48) | 42 (36–48) | |

| Workplaces | 50 (33–77) | 40.5 (33–71) | 50 (39–77) | 51 (45–75) | |

| Residential | 124 (115–132) | 129.5 (119–132) | 123 (115–130) | 124 (117–127) | |

| Odisha | Retail and recreation | 34 (17–52) | 33 (22–35) | 42 (21–52) | 32 (17–50) |

| Grocery and pharmacy | 88 (40–125) | 84.5 (59–94) | 96 (48–125) | 75 (40–108) | |

| Parks | 75 (62–83) | 69.5 (63–73) | 78 (62–83) | 76 (62–80) | |

| Transit stations | 60 (32–77) | 57.5 (44–64) | 66.5 (38–77) | 54 (32–70) | |

| Workplaces | 76 (53–95) | 74.5 (60–95) | 78 (59–82) | 72 (53–81) | |

| Residential | 112 (105–122) | 111 (108–117) | 109 (105–119) | 116 (106–122) | |

| Punjab | Retail and recreation | 49 (20–62) | 36 (29–40) | 47.5 (20–57) | 57 (30–62) |

| Grocery and pharmacy | 105 (50–126) | 95 (76–104) | 105 (50–122) | 106 (63–126) | |

| Parks | 34 (25–44) | 29 (26–32) | 33 (25–38) | 39 (29–44) | |

| Transit stations | 60 (31–72) | 54 (44–57) | 59.5 (31–65) | 63 (37–72) | |

| Workplaces | 74 (61–86) | 69 (61–85) | 74 (67–86) | 75 (71–81) | |

| Residential | 110 (106–117) | 114 (111–115) | 110 (107–117) | 109 (106–112) | |

| Tamil Nadu | Retail and recreation | 40 (10–49) | 33 (30–36) | 40 (24–49) | 43 (10–47) |

| Grocery and pharmacy | 92 (26–111) | 89 (83–97) | 99 (52–111) | 92 (26–102) | |

| Parks | 62 (43–68) | 61 (54–64) | 63 (48–68) | 62 (43–64) | |

| Transit stations | 62 (30–74) | 62 (58–66) | 67.5 (48–74) | 62 (30–67) | |

| Workplaces | 66 (52–96) | 60.5 (52–93) | 66 (54–96) | 65 (55–80) | |

| Residential | 120 (112–127) | 122.5 (113–125) | 119 (112–127) | 120 (115–126) | |

| Telangana | Retail and recreation | 38 (19–44) | 25 (19–28) | 40 (29–44) | 39 (33–44) |

| Grocery and pharmacy | 90 (70–101) | 80.5 (70–87) | 96 (70–101) | 89 (78–100) | |

| Parks | 40 (32–43) | 36 (32–37) | 41 (35–43) | 41 (37–43) | |

| Transit stations | 61 (45–68) | 53.5 (45–57) | 64 (52–68) | 60 (53–64) | |

| Workplaces | 59 (40–87) | 53 (40–84) | 60 (58–87) | 57 (51–84) | |

| Residential | 118 (109–126) | 121.5 (113–126) | 117 (109–119) | 119 (112–123) | |

| West Bengal | Retail and recreation | 36 (11–45) | 22 (11–25) | 36 (27–44) | 39 (14–45) |

| Grocery and pharmacy | 94 (37–109) | 75 (42–85) | 98 (86–107) | 94 (37–109) | |

| Parks | 60 (41–67) | 50.5 (41–55) | 61 (52–67) | 62 (45–67) | |

| Transit stations | 55 (26–64) | 41.5 (26–49) | 55.5 (48–63) | 57 (26–64) | |

| Workplaces | 68 (38–93) | 53 (38–84) | 69 (61–89) | 70 (38–93) | |

| Residential | 115 (110–128) | 116 (110–123) | 114 (112–117) | 115 (111–128) |

4. DISCUSSION

The daily confirmed case rate increased substantially from 0.03 to 285.60 per 10 million people per day during the 7 discrete periods in India. Among the 12 states, the highest case rate was recorded for the NCT of Delhi (53 per 10 million people per day), whereas the lowest was recorded for Kerala (1.64 per 10 million people per day) from 30 January 2020 to 17 May 2020. However, the lowest case rate was recorded for Madhya Pradesh (49.26 per 10 million people per day) from 18 May 2020 to 31 July 2020. Many factors, including population structure and differences in the social contact rate/person/day, likely influenced progression of COVID‐19 in the country. Key factors likely to influence transmission are population density and possibility to implement physical distancing. The NCT of Delhi has a high population density (11,297 persons/km2), with 97.5% of the total population residing in urban areas and 10.91% of the urban population residing in slum areas (COI, 2011a). In contrast, Kerala has a population density of 860 persons/km2, and 47.7% of the total population resides in urban areas and only 1.27% of the urban population resides in slum areas (COI, 2011a). Social contact rate per person per day varied substantially in these settings in India: 17.0 in rural (Kumar et al., 2018), 28.3 in urban developed centres and 67.4 in urban slum areas (Chen et al., 2016).

The case rate was lowest in Kerala state from 30 January to 17 May 2020; it successfully implemented various measures, including testing, contact tracing, medical resource mobilization and communication in the initial stage of the epidemic entry (Das et al., 2020). Additionally, Kerala had a Nipah virus outbreak during May 2018 (Thomas et al., 2019) and gained experience in containing infectious disease outbreaks that their counterpart states would not have; this likely contributed to their low case rate.

The Rt decreased in conjunction with implementation of public health measures including social distancing, travel restrictions, bans on mass‐gathering events, quarantining of positive cases and their contacts, and improved medical care. In Wuhan, China, the Rt decreased from 3.0 in 26 January 2020 to 0.3 in 1 March 2020, within 40 days after multifaceted public health interventions were implemented (Pan et al., 2020). For the United States, the Rt reduced from 4.02 to 1.51 between 17 March and 1 April 2020 (Gunzler & Sehgal, 2020). As of 9 March 2020, the Rt was reported to be 3.10 for Italy, 6.56 for France, 4.43 for Germany and 3.95 for Spain (Yuan et al., 2020). The reduction pattern in Rt in India was similar to other areas of the world after implementing intense mitigation strategies. Although the Rt remained > 1 in most states of India during all 7 periods, the Rt in India was lower than in many European countries as well as the United States. As multiple factors were expected to have contributed to this change, associations of public health interventions with daily case rates and declining Rt warrant further investigation.

Previous studies reported a varied basic reproduction number (R0 ) 1.03 – 4.18 in India (Mandal & Mandal, 2020; Rai et al., 2020; Senapati et al., 2020) due to differences in time periods, data sources or methods employed. The time periods considered in these studies varied between: 4 March 2020 to 3 April 2020, with an estimated R0 of 2.56 (Rai et al., 2020), using initial epidemic growth phase data and reporting R0 to be 4.18 (Senapati et al., 2020); and before 9 April 2020 and reporting an R0 of 1.03 (Mandal & Mandal, 2020). We used official data from 22 March 2020 to 17 May 2020 and 18 May 2020 to 31 July 2020 to derive Rt estimates, so these estimates cannot be compared directly.

The mobility index highlighted the adoption level of the public health contact mitigation interventions imposed by the Indian government; clearly, they were highly effective in substantially reducing social contact in the country. Mobility in the country was < 50% in all the domains except grocery and pharmacy, where mobility was 53% (as compared to 100% baseline value) from 22 March 2020 to 17 May 2020. This likely had an important role in containing the COVID‐19 epidemic in the country and will perhaps explain in part why our calculated Rt for India was substantially lower than that estimated for many European countries and the United States where mobility did not decrease as drastically as in India. Increase in ‘Pharmacy mobility’ during the Unlock 1 and Unlock 2 needs to be investigated to confirm that COVID‐19 patients are not directly purchasing drugs without being captured in the government controlled COVID‐19 testing.

The current study had some limitations. The overall testing rate has not been very high in India; as of 23 May 2020, the country had tested 2,943,421 samples at a rate of 2,432 per million people. As of 1 June 2020, the United States had tested 17,612,125 samples at a rate of 53,911 per million people (CDC, 2020). Information on the diagnostic testing patterns remains illusive. However, there was a shortage of testing during the early phase of the epidemic. India tested 100 samples per day before 20 March 2020, but this was scaled up to 100,000 tests per day on 20 May 2020 (ICMR, 2020a). It has been demonstrated that changes in testing rates affect the epidemic curve of COVID‐19 (Omori et al., 2020). Therefore, an underestimated case rate in the initial stage of the epidemic cannot be ruled out. Additionally, migration of COVID‐19 cases between states cannot be excluded. As per the census of India (2011), 29.9% of total human population are migrants and 13.8% of the total population migrates between states, possibly due to social, economic and political reasons (COI, 2011b). Many anecdotal reports reveal interstate movement of migrants due to national lockdown/curfew and loss of jobs; however, exact figures remain unknown. Interstate migration of COVID‐19‐positive cases resulted in an unexplained bias in state‐level estimates. For example, Tamil Nadu state reported 646 cases as of 26 May 2020, with 54 cases being persons returning from other states (HFWD, 2020). Although these cases were not included for Tamil Nadu estimates, such data were not available from other states. Therefore, under‐ or overestimation at the state level cannot be ruled out.

Many other epidemiologic variables such as symptom‐onset date, proportion of asymptomatic or undiagnosed cases, as well as diagnostic testing patterns, remain unavailable. Moreover, impacts of individual state‐level or component parts of the overall strategies during the government‐imposed interventions remain unexamined. Therefore, current estimates should be carefully interpreted. Notwithstanding, in our opinion the current study provides much‐needed information for further control and prevention of COVID‐19 in India. Availability of additional data, hopefully in the near future, is expected to further improve these efforts.

The Indian government imposed strict contact mitigation followed by phased relaxation, which slowed the spread of COVID‐19 epidemic progression in India, as evidenced by the decreasing Rt demonstrated in this study. These findings will also inform policy development for the control of COVID‐19 epidemic in other regions and countries.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

ETHICAL STATEMENT

Informed consent for collection of epidemiological data was not required, as these data were already coded and available in the public domain. No identifiable personal information was used in this study.

Supporting information

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors acknowledge India's National and State Health departments for collecting the daily COVID‐19 epidemic data and releasing it in the public domain.

Singh BB, Lowerison M, Lewinson RT, et al. Public health interventions slowed but did not halt the spread of COVID‐19 in India. Transbound Emerg Dis.2021;68:2171–2187. 10.1111/tbed.13868

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The analysed data are available along with the manuscript. Sources of the raw data used in the analysis have been cited.

REFERENCES

- Andersen, K. G. , Rambaut, A. , Lipkin, W. I. , Holmes, E. C. , & Garry, R. F. (2020). The proximal origin of SARS‐CoV‐2. Nature Medicine, 26(4), 450–452. 10.1038/s41591-020-0820-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, R. M. , Heesterbeek, H. , Klinkenberg, D. , & Hollingsworth, T. D. (2020). How will country‐based mitigation measures influence the course of the COVID‐19 epidemic? The Lancet, 395(10228), 931–934. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30567-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC . (2020). Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID‐19). Testing Data in the U.S. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019‐ncov/cases‐updates/testing‐in‐us.html.

- Chen, J. , Chu, S. , Chungbaek, Y. , Khan, M. , Kuhlman, C. , Marathe, A. , & Xie, D. (2016). Effect of modelling slum populations on influenza spread in Delhi. British Medical Journal Open, 6(9), e011699. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COI . (2011a, 17 May 2020). Census of India 2011. Population enumeration data (Final population). Retrieved from http://censusindia.gov.in/2011census/population_enumeration.html.

- COI . (2011b, 05 June 2020). Census of India. Migration. Retrieved from https://censusindia.gov.in/Census_And_You/migrations.aspx.

- Cori, A. , Ferguson, N. , Fraser, C. , & Cauchemez, S. (2013). A new framework and software to estimate time‐varying reproduction numbers during epidemics. American Journal of Epidemiology, 178(9), 1505–1512. 10.1093/aje/kwt133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das, M. , Gennaro, I. , Menon, S. , Shah, A. , Shah, K. , Sippy, T. , & Vedavalli, P. (2020, 17 May 2020). Kerala’s strategies for COVID19 response: Guidelines and learnings for replication by other Indian states. Retrieved from http://www.idfcinstitute.org/knowledge/publications/working‐and‐briefing‐papers/keralas‐strategies‐for‐covid‐19‐response/.

- Google, L. (2020, 18 August 2020). Google COVID‐19 Community Mobility Reports. Retrieved from https://www.google.com/covid19/mobility/.

- Gunzler, D. , & Sehgal, A. R. (2020). Time‐varying COVID‐19 reproduction number in the United States. medRxiv, 2020.2004.2010.20060863. doi:10.1101/2020.04.10.20060863.

- Hellewell, J. , Abbott, S. , Gimma, A. , Bosse, N. I. , Jarvis, C. I. , Russell, T. W. , & Eggo, R. M. (2020). Feasibility of controlling COVID‐19 outbreaks by isolation of cases and contacts. The Lancet Global Health, 8(4), e488–e496. 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30074-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HFWD . (2020, 17 May 2020). Health and Family Welfare Department. Government of Tamil Nadu. COVID 19 Dashboard. Daily Bulletin. Retrieved from https://stopcorona.tn.gov.in/archive/.

- ICMR . (2020a, 17 May 2020). Indian Council of Medical Research. How India ramped up COVID‐19 testing capacity. Retrieved from https://main.icmr.nic.in/sites/default/files/press_realease_files/ICMR_Press_Release_India_testing_story_20052020.pdf.

- ICMR . (2020b, 20 May 2017). Indian Council of Medical Research. Revised Strategy for COVID19 testing in India (Version 4, dated 09/04/2020). Retrieved from https://main.icmr.nic.in/content/covid‐19.

- Kumar, S. , Gosain, M. , Sharma, H. , Swetts, E. , Amarchand, R. , Kumar, R. , & Krishnan, A. (2018). Who interacts with whom? Social mixing insights from a rural population in India. PLoS One, 13(12), e0209039. 10.1371/journal.pone.0209039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q. , Guan, X. , Wu, P. , Wang, X. , Zhou, L. , Tong, Y. , & Feng, Z. (2020). Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel Coronavirus–infected pneumonia. New England Journal of Medicine, 382(13), 1199–1207. 10.1056/NEJMoa2001316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandal, M. , & Mandal, S. (2020). COVID‐19 pandemic scenario in India compared to China and rest of the world: a data driven and model analysis. medRxiv. doi:https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.04.20.20072744v1.full.pdf.

- MHFW . (2020. a, 30 August 2020). COVID‐19 Statewise Status. Retrieved from https://www.mohfw.gov.in/.

- MHFW . (2020b, 17 May 2020). Update on Novel Coronavirus: one positive case reported in Kerala (Release ID: 1601095). Retrieved from https://pib.gov.in/PressReleseDetail.aspx?PRID=1601095.

- Omori, R. , Mizumoto, K. , & Chowell, G. (2020). Changes in testing rates could mask the novel coronavirus disease (COVID‐19) growth rate. International Journal of Infectious Diseases : IJID : Official Publication of the International Society for Infectious Diseases, 94, 116–118. 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.04.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan, A. , Liu, L. , Wang, C. , Guo, H. , Hao, X. , Wang, Q. , & Wu, T. (2020). Association of Public Health Interventions With the Epidemiology of the COVID‐19 Outbreak in Wuhan, China. Journal of the American Medical Association, 323(19), 1915–1923. 10.1001/jama.2020.6130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rai, B. , Shukla, A. , & Dwivedi, L. K. (2020). COVID‐19 in India: Predictions, Reproduction Number and Public Health Preparedness. medRxiv, 2020.2004.2009.20059261. doi:10.1101/2020.04.09.20059261.

- Richterich, P. (2020). Severe underestimation of COVID‐19 case numbers: effect of epidemic growth rate and test restrictions. medRxiv 2020.04.13.20064220. doi:10.1101/2020.04.13.20064220.

- Senapati, A. , Rana, S. , Das, T. , & Chattopadhyay, J. (2020). Impact of intervention on the spread of COVID‐19 in India: A model based study. arXiv.org. Retrieved from https://arxiv.org/pdf/2004.04950.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Thomas, B. , Chandran, P. , Lilabi, M. P. , George, B. , Sivakumar, C. P. , Jayadev, V. K. , & Hafeez, N. (2019). Nipah Virus Infection in Kozhikode, Kerala, South India, in 2018: Epidemiology of an outbreak of an emerging disease. Indian Journal of Community Medicine, 44(4), 383–387. 10.4103/ijcm.IJCM_198_19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO . (2020a, 15 August 2020). Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) Situation Reports – 10–193. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel‐coronavirus‐2019/situation‐reports/.

- WHO . (2020b, 31 August 2020). WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID‐19) Dashboard. Retrieved from https://covid19.who.int/.

- WHO . (2020c, 17 May 2020). World Health Organisation (WHO) Timeline – COVID‐19 – 11 March 2020. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/news‐room/detail/27‐04‐2020‐who‐timeline–‐covid‐19.

- Yuan, J. , Li, M. , Lv, G. , & Lu, Z. K. (2020). Monitoring transmissibility and mortality of COVID‐19 in Europe. International Journal of Infectious Diseases, 95, 311–315. 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, P. , Yang, X.‐L. , Wang, X.‐G. , Hu, B. , Zhang, L. , Zhang, W. , & Shi, Z.‐L. (2020). A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature, 579(7798), 270–273. 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material

Data Availability Statement

The analysed data are available along with the manuscript. Sources of the raw data used in the analysis have been cited.