Abstract

Due to the outbreak of Coronavirus, humans all over the world are facing several health problems. The present study has explored the spatio‐temporal pattern of Coronavirus spread in India including spatial clustering, identification of hotspot, spatial heterogeneity, and homogeneity, spatial trend, and direction of COVID‐19 cases using spatial statistical analysis during the period of 30 January to 20 June 2020. Besides, the polynomial regression model has been used for predictions of COVID‐19 affected population and related deaths. The study found positive spatial heterogeneity in COVID‐19 cases in India. The study has also identified 17 epicentres across the country with high incidence rates. The directional distribution of ellipse polygon shows that the spread of COVID‐19 now trending towards the east but the concentration of cases is mainly in the western part of the country. The country's trend of COVID‐19 follows a fourth‐order polynomial growth and is characterized by an increasing trend. The prediction results show that as on 14 October India will reach 14,660,400 COVID‐19 cases and the death toll will cross 152,945. Therefore, a “space‐specific” policy strategy would be a more suitable strategy for reducing the spatial spread of the virus in India. Moreover, the study has broadly found out seven sectors, where the Government of India lacks in terms of confronting the ongoing pandemic. The study has also recommended some appropriate policies which would be immensely useful for the administration to initiate strategic planning.

Keywords: COVID‐19 outbreak, geographical information system, geographically weighted regression, polynomial regression, spatial clustering, spatial trend

Resumen

Debido al brote del Coronavirus, los humanos de todo el mundo se enfrentan a varios problemas de salud. En el presente estudio se han explorado las pautas espacio‐temporales de la propagación del Coronavirus en la India, entre ellas la agrupación espacial, la identificación de focos, la heterogeneidad espacial y la homogeneidad, la tendencia espacial y la dirección de los casos de COVID‐19, usando un análisis estadístico espacial para el período entre el 30 de enero y el 20 de junio de 2020. Además, se ha utilizado el modelo de regresión polinómica para las predicciones de la población afectada por COVID‐19 y las muertes relacionadas. El estudio encontró una heterogeneidad espacial positiva en los casos de COVID‐19 en la India. También identificó 17 epicentros en todo el país con altas tasas de incidencia. La distribución direccional del polígono de la elipse muestra que la propagación de COVID‐19 ahora tiende hacia el este, pero la concentración de casos se encuentra principalmente en la parte occidental del país. La tendencia del país para COVID‐19 sigue un crecimiento polinómico de cuarto orden y se caracteriza por una tendencia al alza. Los resultados de la predicción muestran que, a 14 de octubre, la India alcanzará 14.660.400 casos de COVID‐19 y el número de muertes sobrepasará las 152.945. Por consiguiente, una estrategia política “espacialmente específica” sería una estrategia más adecuada para reducir la propagación espacial del virus en la India. Además, el estudio ha descubierto en general siete sectores en los que el Gobierno de la India carece de medios para hacer frente a la pandemia. En el estudio también se recomiendan algunas políticas apropiadas que serían inmensamente útiles para que la administración inicie una planificación estratégica.

抄録

新型コロナウイルスの発生により、世界中の人々は健康問題に直面している。本稿では、2020年1月30日~6月20日の期間で、新型コロナウイルス感染症 (COVID‐19)症例の空間クラスタリングや、ホットスポット、空間的な異質性及び同質性、空間的トレンド、方向性を、空間的統計分析を用いて特定し、インドにおけるコロナウイルスの拡大の時空間パターンを探索する。本研究から、インドのCOVID‐19症例には間的異質性が認められ、全国で、発生率の高い17のエピセンターも確認された。楕円多角形の方向分布は、現在COVID‐19は東に向かって拡大しているが、症例は主に国の西部に集中していることを示している。インドにおけるCOVID‐19のトレンドは4次多項式的に上昇する増加傾向が特徴である。インドのCOVID‐19症例は、10月14日の時点で14,660,400例に達し、COVID‐19による死亡者数は152,945人を超えると予想された。そのため、インドにおける新型コロナウイルスの空間的拡大を抑制するための戦略としては、地域に特異的な政策をとることがより適切であると考えられる。さらに、現在も続くパンデミックに対処する上でインド政府に不足している7つの分野が明らかになった。また、インド政府が戦略的計画を開始する際に非常に有用となると考えられる、適切な政策を推奨する。

1. INTRODUCTION

The novel Coronavirus‐2019 disease1 has posed an incredible danger to all mankind throughout the world (Mondal & Ghosh, 2020; Nadeem, 2020). It is a contagious human disease and its fast pace of infection and rate of transmission among people has introduced a new challenge for the health care system (Clara‐Rahola, 2020). The average incubation period of COVID‐19 is 5 to 6 days, although it can take up to 2 to 14 days for appearing symptoms (Arti, 2020; Pandey, Chaudhary, Gupta, & Pal, 2020) and during this long incubation period, the COVID‐19 infected patients can transmit the virus without any symptoms to his/her surrounding people (Koubaa, 2020). An interesting fact comes in light that the spread of the virus is following the geographic pattern, such as northern Italy is more affected than the southern part, and cities are more affected than rural areas. Currently, more than 70 percent of the total COVID‐19 cases across the world are reported from 11 countries namely the US, Brazil, India, Russia, South Africa, Peru, Mexico, Colombia, Chile, Spain and Iran. The World Health Organization (WHO) has reported that more than 213 countries and territories around the world are affected by the spreading of this deadly virus through direct contact by the affected people. However, the extent of the casualty rate is quite different for various land areas and essentially differs considering the demography of population and health care facilities (Ranjan, 2020) as well as on the effective steps taken by the government from time to time (Bedford et al., 2020).

In addition, Chowell and Rothenberg (2018) mentioned that infectious diseases (respiratory influenza, pneumonia, respiratory syncytial virus; vector‐borne like malaria, dengue, and Zika; sexually transmitted disease such as HIV and syphilis) follow a dynamic spatial pattern along with the associated socio‐economic and environmental conditions. Hence, COVID‐19, as an infectious disease, it has a high probability that it would follow a spatial pattern. In India, Ghosh, Dinda, Chatterjee, Das, and Mahata (2019) found that the spatial clustering of dengue follows a particular spatial trend in the city of Kharagpur. Similar kind of findings has been found by Rasam et al. (2014) in an exploratory analysis of the cholera spatial pattern in the district of Sabah in Malaysia. It has also been found that infectious disease also follows a general spatial pattern and cluster based on the infected person or locations (Lessler, Salje, Grabowski, & Cummings, 2016). Brockmann, David, and Gallardo (2009) mentioned that infectious diseases are strongly correlated with human mobility in the globalized world. Therefore, it also has a probability that COVID‐19 would follow a spatial trend according to human mobility in a country. Moreover, it was also found that in the case of COVID‐19, the distance has played a significant role to spread. Akhtar, Kraemer, and Gardner (2019) has shown that the Zika epidemic (infectious disease) in South America shows a spatial pattern with an overall accuracy of above 85 percent. Stresman et al. (2018) have found that hotspots of malaria, spread the disease in the surrounding areas following a systematic pattern. Inter household contact plays an agency role in malaria spreading. In India, it has been reported that cities are mainly playing the COVID‐19 epicentre, which indicates a systematic spatial pattern (Kaur et al., 2020).

Moreover, these infectious diseases have rapidly increased over the last two decades. The unhygienic environmental condition is responsible for the increasing rate of infectious diseases. For example, the waterborne diseases in the city of Tamil Nadu in summer seasons are identified with the dirty water from open sewage lines and drains, which show the clear linear pattern of disease spread. In the case of COVID‐19, it has been found that it spreads through social contacts with the active facilitation of illegal animal markets in Wuhan, China (Adnan, Khan, Kazmi, Bashir, & Siddique, 2020; Zhu et al., 2020).

However, there is a growing understanding that infectious diseases have specific geography; therefore, it is becoming increasingly important to study the different layers of health‐related data for a particular place. The geographic information systems (GIS) prepares a perfect base to merge explicit data regarding the disease and their interpretation in connection with population habitancy, encompassing health and social services and the natural environment (Zhou et al., 2020). However, a spatial examination of the epidemic focused on the question “Where is the disease concentrating and in which direction is it spreading?” GIS is being used in the epidemic studies to find where people are affected the most and the also makes it possible to view disease distributions in great detail. Haining (2012) mentioned that GIS plays a significant role to determine the trend of any disease spread over space. Moreover, the Tobler’s “first law of geography, explains that everything is related to everything else, but near things are more related than distant things. The spatial autocorrelation has critically explained this phenomenon and it is widely applicable in case of spatial spread of COVID‐19 in any country.

Therefore, in context of COVID‐19 spread in India, the present study aims to explore the spatial pattern of COVID‐19 outbreak including estimation of hotspots, clustering, spatial direction, and heterogeneity with the help of GIS in different time frames. Besides, the temporal trend of COVID‐19 cases in India has also been explored and predictions of positive cases have been estimated. In addition to that India’s response in managing the pandemic and necessary suitable policy dimensions also has been discussed in this study.

The rest of the paper has been organized as follows: Section 2 elaboratesthe method of this study, where different method and data sources have discussed. In Section 3, the results of the above‐mentioned research have been discussed. We have discussed the result according to each method applied in this study. Section 4 concludes, where the major findings have explained, in addition the selected suggest measure to confronting the COVID‐19 has highlighted.

2. METHODOLOGY AND DATA SOURCES

2.1. Hot‐Spot Analysis

As mentioned earlier, the present paper focuses on hotspots identification, spatial autocorrelation, and spatio‐temporal mapping of COVID‐19 spread in India. For hotspot analysis of present COVID‐19 in India Getis–Ord Gi* statistics have been calculated. It is a distance‐based z‐score value that tells where the particular phenomena significantly cluster. A high z‐score and small p‐value for a feature indicate a significant hot spot (Ruktanonchai, Pindolia, Striley, Odedina, & Cottler, 2014). The near‐zero z‐score indicates no spatial clustering. Following is the statistical expression of Getis–Ord Gi*:

where, x j is the attribute value for feature j, w i,j is the spatial weight between i and j; n is the total number of features. represents the mean whereas s denotes the standard deviation.

2.2. Spatial association

To understand the spatial autocorrelation, Moran’s I‐ method has been applied, which provides a correlation measure to a spatial context. The Moran’s I index value would indicate how the COVID‐19 affected cases are spatially distributed and what kind of pattern is being followed, namely, random(I = 0), dispersed(I < 0), and clustered(0 < I) (Chen, 2013). Following is the statistical expression of Moran’s I:

where N is the number of observation (in the present study i.e. polygon), is the mean of the variable, x i is the value of the variable in a particular location, w ij is the weight indexing location of i and j.

The inverse distance weighted (IDW) technique has been applied to compute the spatio‐temporal pattern analysis of COVID‐19 spread and distribution. The IDW generates an average value of COVID‐19 spread for unsampled locations across India using values from nearby weighted locations. The larger the power coefficient, the stronger is the weight of nearby points. The following equation estimates the value z at an unsampled location j:

where the sigma simply means the number of points that will be interpolated. A smaller number in the denominator (more distance) has less effect on the interpolated (Zp) value. In the IDW, the sampled points and values are superimposed on top and an interpolated raster is generated within the boundary. This results in nearby points having a greater influence on the unsampled locations.

In addition, the geographically weighted regression (GWR 1) has applied to understand the spatial prediction of diseases based on other demographic variables. In the present study, the GWR analytical framework is following:

where is the geographical co‐ordinate of the point i. T p is the total population, P d is the population density, H i is the health infrastructure, S c is the sub centre, P hc is the primary health centre, and C hc is the community health centre of the ith district. The regression coefficient is estimated at each data location. In GWR, an observation is weighted following its proximity to location i, so that the weighting of observation is no longer constant. The weight of each point is calculated as:

In GWR, the weight assigned to each observation is based on a distance decay function centred on observation i. In GWR, the local weights matrix is calculated from a kernel function W that places more weight on locations that are closer in space to the calibration location than those that are more distant in space.

2.3. Average nearest neighbour (ANN)

The widely applied ANN technique of clustering has been used to determine the spatial clustering of COVID‐19 trends in India. It considers the distance between each feature centroid and its nearest neighbour’s centroid location. If the average distance is less than the average for a hypothetical random distribution, the distribution of the features being analysed is considered clustered otherwise features are considered dispersed (Ebdon, 1985). The following are details of the average nearest neighbour ratio:

where, is the observed mean distance between each feature and its nearest neighbour:

and is the expected mean distance for the feature given in a random pattern:

where n is the total number of features, A is the area of minimum enclosing rectangle around the feature. The average ANN’s z score statistics calculated as:

where, standard error

If the index (average nearest neighbour ratio) is less than 1, the pattern exhibits clustering. If the index is greater than 1, the trend is towards dispersion.

2.4. Directional distribution (standard deviational ellipse)

The standard deviational ellipses show the spatial characteristics of COVID‐19 dispersion and directional trends. It is based on either Euclidean or Manhattan distance. The standard deviation ellipse is the most widely used technique to predict a disease outbreak over time. The standard deviational ellipse is given as:

where x and y are the co‐ordinates for feature i, { , ӯ} represent the mean centre for the features, and n is equal to the total number of features.

2.5. Temporal trend analysis

For understanding the future trend of the total affected cases of COVID‐19 in India, the polynomial regression model has been applied. The model predicts the prevalence of COVID‐19 in India given the time‐series data. The polynomial regression is based on the curvilinear relationship between a dependent and an independent variable. The following is the statistical expression of a polynomial regression model:

where X is the independent variable and M is the order of the polynomial. β 0 is the bias and also the intercept, β 1, β 2, β 3, β 4, are the weight or partial coefficients assigned to the predictors and n is the degree of the polynomial. The future value of COVID‐19 affected cases has been estimated based on 80 days of observation and estimated values are validated and corrected through the root mean squared log error (RMSLE) method considering ten days’ actual data. The formula of RMSLE is:

where, are the actual and predicted values respectively. The statistical uncertainty of the predicted value has been estimated based on the 95 percent predicted interval.

2.6. Data sources

The district and state‐level COVID‐19 cases data have been collected from the official website of the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. For country‐level time‐series data, the situational reports from WHO have been used. The time‐series data has been collected from 30 January to 20 June 2020; which include total confirmed, recovered, and death cases of COVID‐19 in India by the states and union government in India. Besides, the high resolution (30” × 30” or approximately 1 km) LandScan‐2018 population data has been used for GWR analysis. However, as a lesser number of populations has been tested compare to total population in India. therefore, there is a limitation of the database.

3. RESULT AND DISCUSSION

3.1. Spatiotemporal pattern of COVID‐19 hotspots and outliers

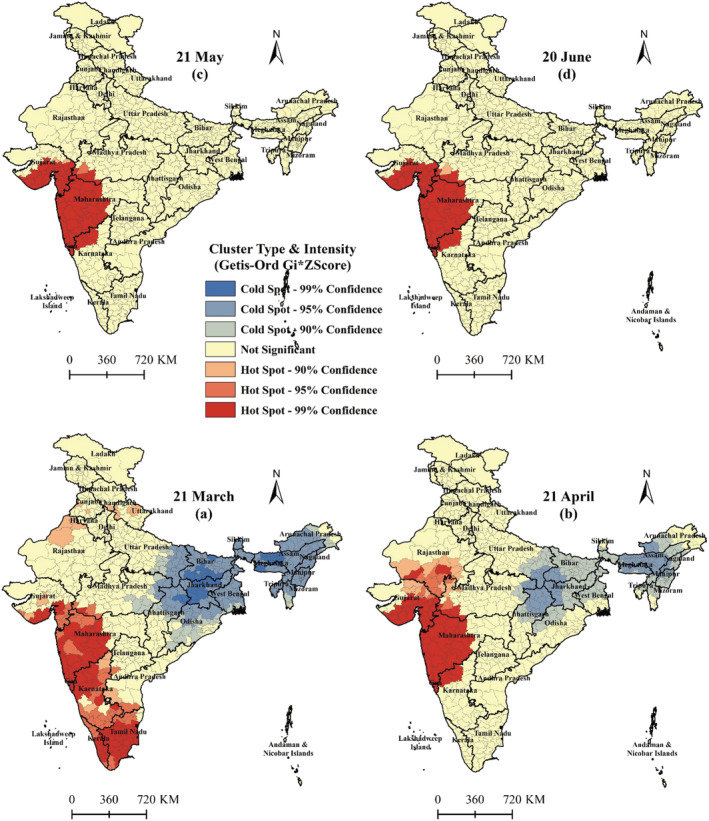

A commendable spatio‐temporal pattern all over the world can be identified by spatially analysing a statistically viable and important clustering of the locale through the hotspot and the cold‐spots. The hotspots analysis revealed that core clustering of high COVID‐19 affected districts are clustered mostly in the western regions (as of 20 June analysis) and variously encompassed by 60 districts (Maharashtra and Gujarat) though initially (as of 21 March 2020) the spread of various COVID‐19 clusters was along the southern (Tamil Nadu‐Chennai, Andhra Pradesh‐Hyderabad, Karnataka‐Bengaluru, and Kerala), western (Maharashtra‐Mumbai, Gujarat‐ Ahmedabad; two main commercial hubs of the country) and north‐central (Delhi‐ the national capital) regions of the country and encompassed 139 districts (Figure 1a). This result clearly portrays a high amount of incidence rate in the area. Similarly, a significant cold spots clusters were visible in the Eastern region (as of 21 March analysis) comprising Assam, West Bengal, Bihar and their surrounding regions encompassed 262 districts (Figure 1a) and the increase in the number of cases with respect to time in the eastern region has led to the sharp decline of cold spots that existed previously in that region. As of 21May, and 20 June, the cold spot areas in the eastern part disappeared completely (Figure 1c and d) indicating that the next phase of virus spread could possibly target these zones. Even at the pick of the pandemic stage in India, comparatively lower numbers of cases were reported from the east, except for a few centres situated at Gangetic West Bengal, Coastal Odisha, and along the Ganga valley of eastern Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. The hot spots analysis during the peak of lockdown phase (21 April) indicates intense clustering of high values around Maharashtra, Gujarat, and Rajasthan (Figure 1b); however, the initial high values clustering around Kerala, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu diminished in this phase possibly due to pre‐emptive actions taken by the Kerala, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu state governments and union government’s policies. Except for most likely hotspots and cold spots, other areas were identified as secondary categories, among which most areas do not show significant spatio‐temporal trends as shown in Figure 1. With time the yellow zones expanded covering larger areas because the cold spot zones turned into yellow due to the jump in the new COVID‐19 cases. West Bengal, Bihar, Assam, Chhattisgarh, Odisha, Jharkhand, Tripura, Nagaland are the states where the trend is very high (Figure 1d). However, in north‐east India, the numbers of COVID‐19 cases are much lower as compared to the rest of the country. It is because none of the airports in this region is internationally connected; a few numbers of immigrants have come to this region and out of them, most are travellers. From another point of view, after analysing hotspots, four places have been spotted (Delhi, Mumbai, Chennai, and Kolkata) which came out to be significant hotspots and they gradually extended the infection to the neighbouring locale. These cities are one of the heavily populated regions of the nation and pulled in an enormous number of floating populations from various parts of the nation, which made these places to be largely affected by COVID‐19. On the other hand, airports of these cities are internationally connected and acted as penetration paths of COVID‐19 from foreign countries. Figure 2 shows the standard deviation of COVID‐19 cases across the country, where a high Z‐score value corresponding to high amount of incidence rate in the area.

FIGURE 1.

Pattern and intensity of COVID‐19 hotspots in India (red and blue colours area represents statistically significant hotspots and cold‐spots respectively)

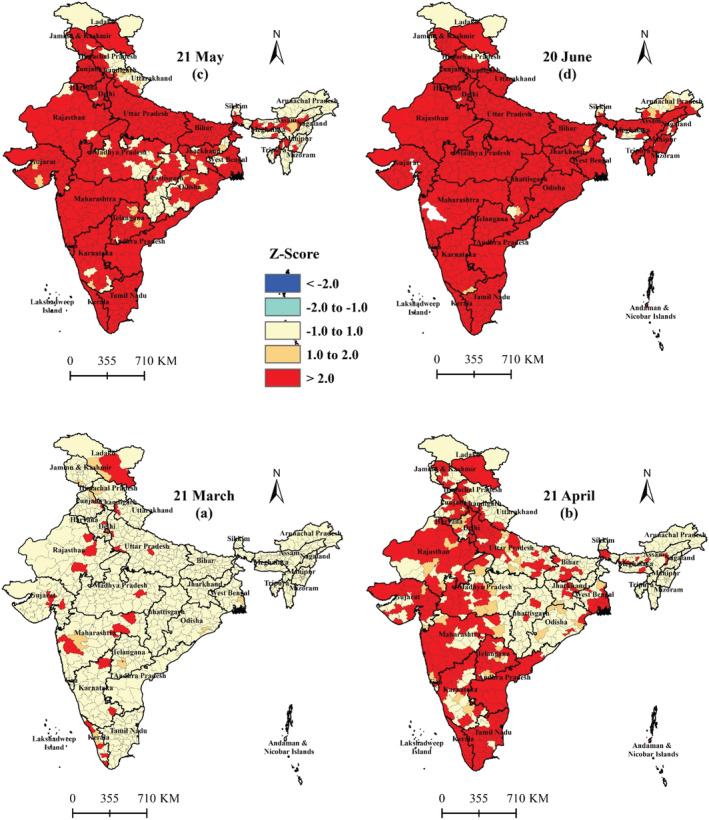

FIGURE 2.

Z‐score mapping for symbolizing standard deviation of COVID‐19 cases across the country (red colours area indicates Z‐score above 2 standard deviation)

3.2. Spatial association and GIS interpolation mapping

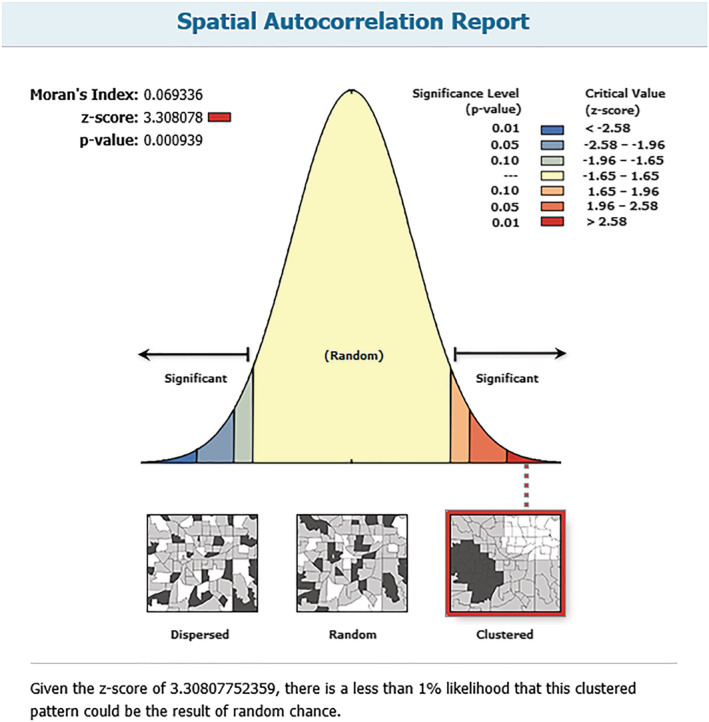

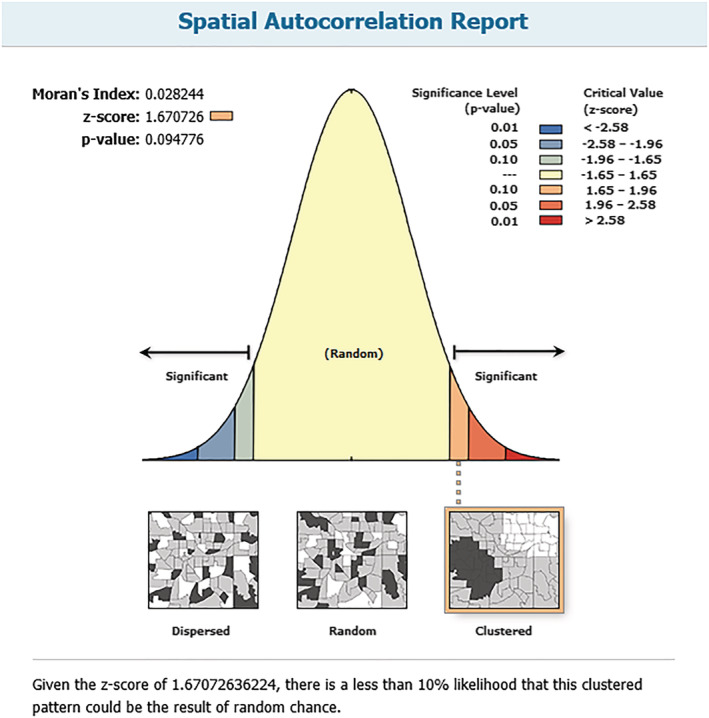

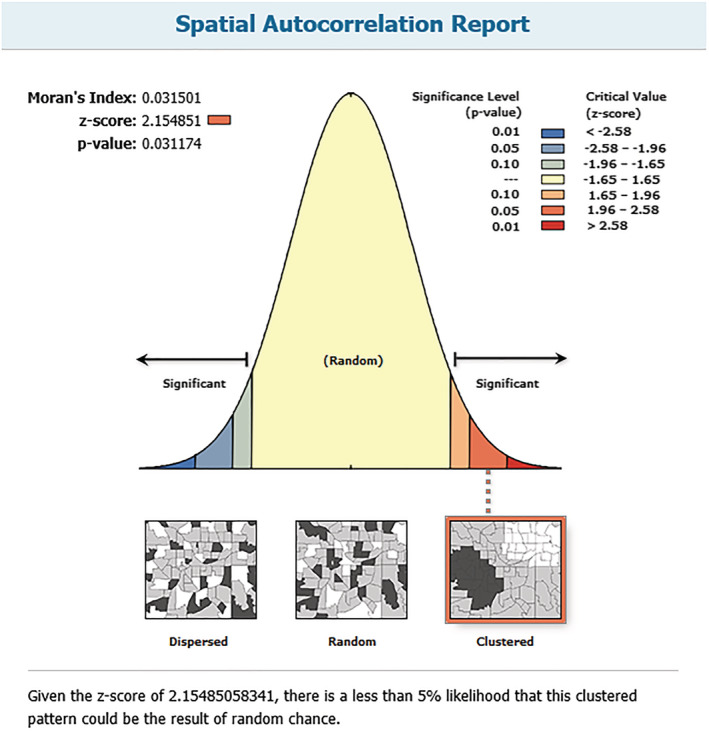

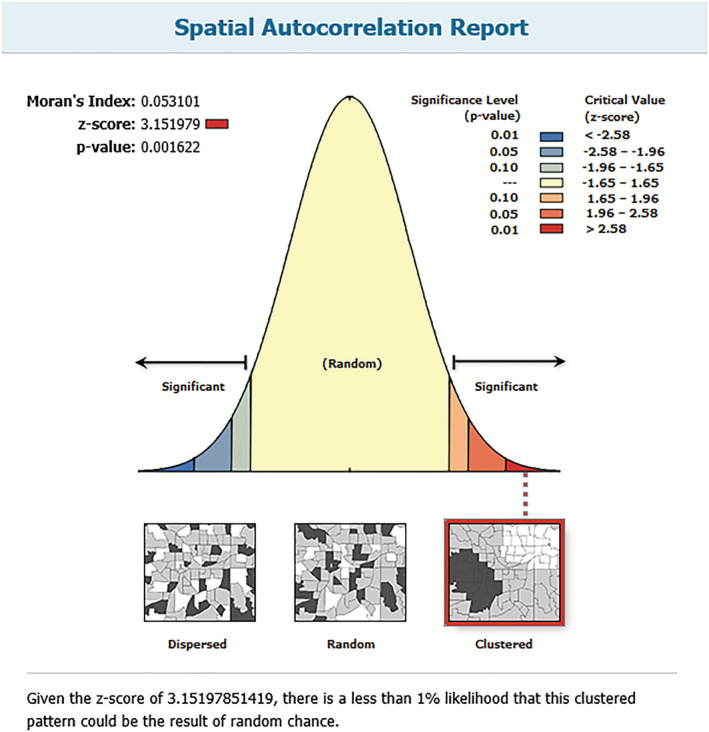

The Moran’s I based spatial autocorrelation values represent that there is a positive spatial auto correlation in COVID‐19 cases throughout India. The Moran’s I value for 21 March COVID‐19 cases was recorded 0.069 (p = 0.0009), and the Z‐score was 4.67 (Figure A1), which shows the data is statistically significant and confirms the presence of spatial structure. While the Moran’s I value for 21 April was 0.028 (p = 0.09) indicating a heterogeneity structure of COVID‐19 growth across the country (Figure A2). However, the Moran’s I value on 21 May was recorded 0.031, p = 0.031 (Figure A3) and on 20 June it was 0.053, p = 0.001 (Figure A4), showing an increasing trend of Moran’s I values which indicates that the structure of COVID19 growth across the country will reach a homogenous spatial structure. Besides, there was a significant temporal variation in the spatial dependence of COVID‐19 cases including early dates followed by a general size and significance of Moran’s I (range‐1 to +1) from 0.069 on 21 March to 0.053 on 20 June 2020.

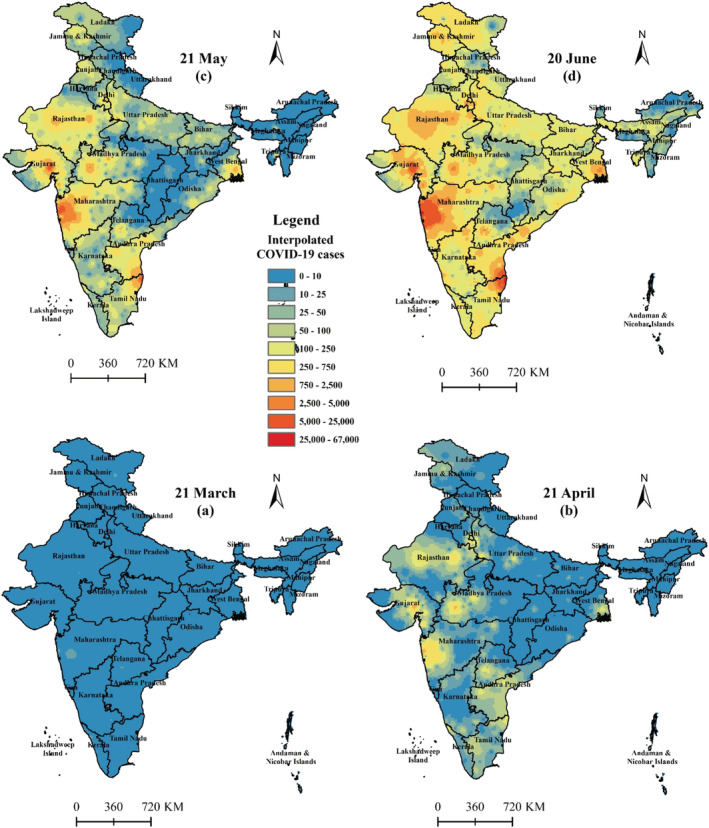

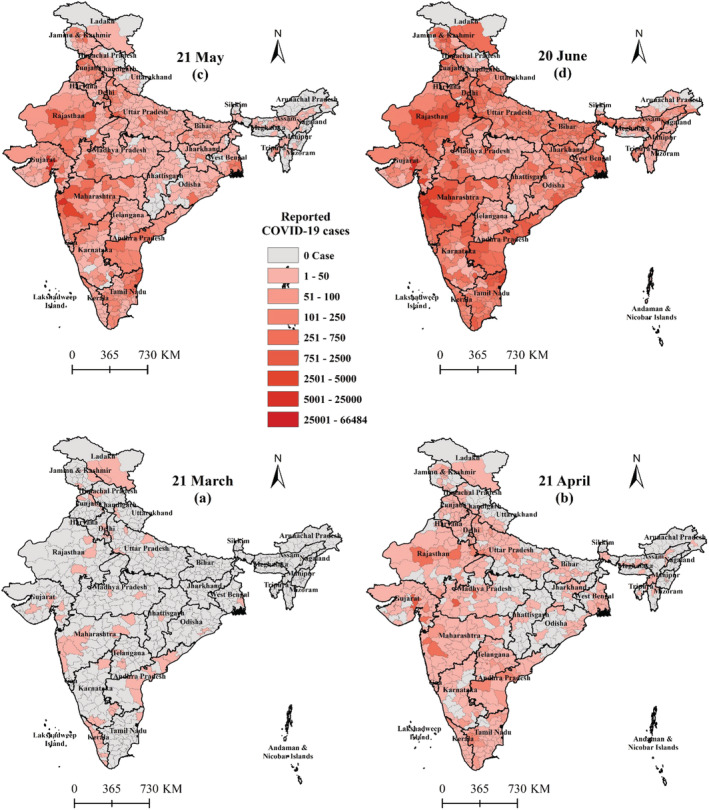

Figure 3, shows the general intensification and spatio‐temporal spread of the COVID‐19 pandemic in India. In the first phase, (as of 21 March) possible potential outreach was mostly around south Delhi (northern region), Mumbai (Western region), Hyderabad, Bangalore (Southern region) and Indore (Central region), Kerala (Southern region), Ladakh (Northern region) and Bhilwara (Western region). With time, epicentre expanded and newly emerged around the South Delhi, Agra in the Northern region; Mumbai, Thane, Pune, Surat, Ahmedabad Jaipur, Jodhpur in the Western region; Chennai, Hyderabad, Kurnool in the Southern region, Bhopal, Indore in the central region; Lucknow, Kanpur central in North‐eastern region; and Kolkata and its surrounding areas in the eastern region (Figure 3b). Kerala played a major role in the second phase analysis, by showing a marked improvement. This scenario continued into the next phases (21 May) as well and rapid growth and expansion were observed around the Mumbai, Ahmedabad, Indore, Chennai, Kolkata, and surrounding areas (Figure 3c). However, in the last phase (as of 20 June), most of the areas has recorded total cases in the triple digit. The gravity of the COVID‐19 cases is very high in the Western regions of the country especially Maharashtra and Gujarat. The existent epicentres are significantly affected its surrounding areas. Besides the virus spread significantly in the north‐eastern regions especially in the eastern districts of West Bengal, Bihar, Jharkhand, Assam, and gradually these areas come under pandemic situations due to inter‐state in migration of migrant labour from Western and Southern parts of the country (Figure 3d). Therefore, the eastern part of the country now faces an imminent threat of becoming epicentres of COVID‐19 cases and in the near future most probably these areas will become major hotspots as the spread of the virus in western regions may start to peak or gradually decline. This analysis showed a variety in the spatial dispersion of COVID‐19 cases in the nation and cases are expanding day by day.

FIGURE 3.

Spatio‐temporal trend of COVID‐19 outbreak in India (continuous surfaces produced by interpolating district wise COVID‐19 cases)

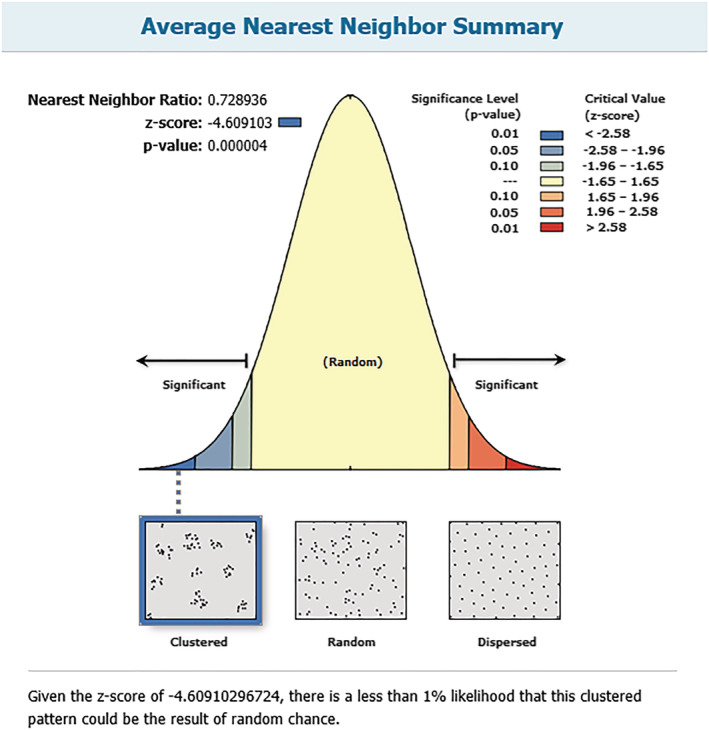

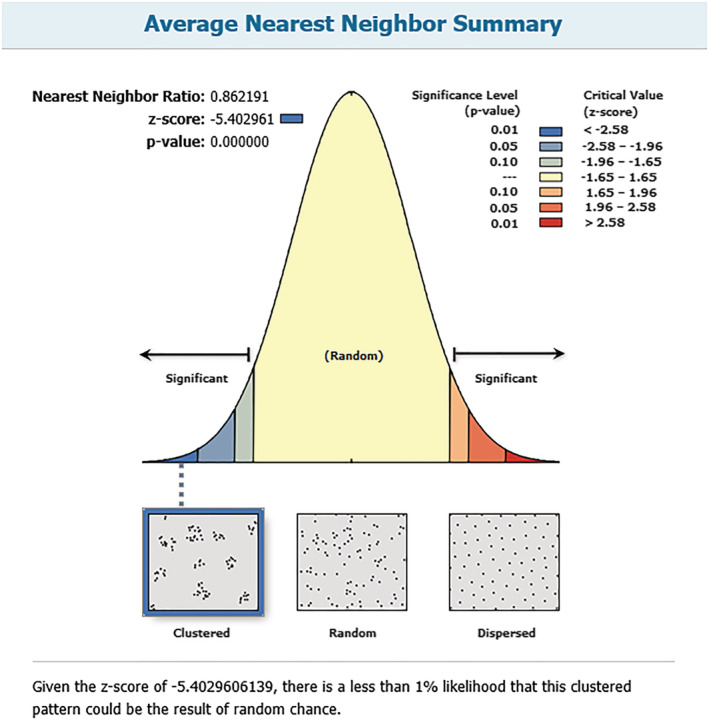

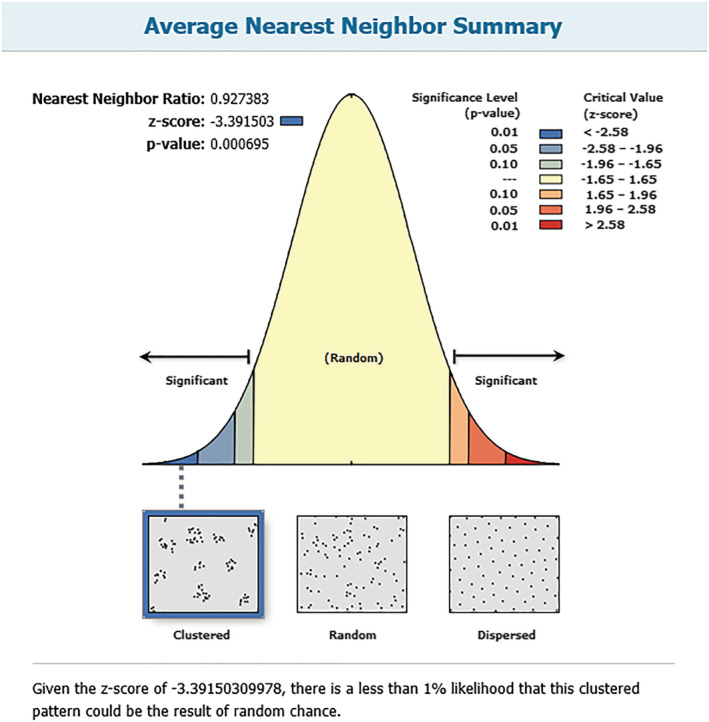

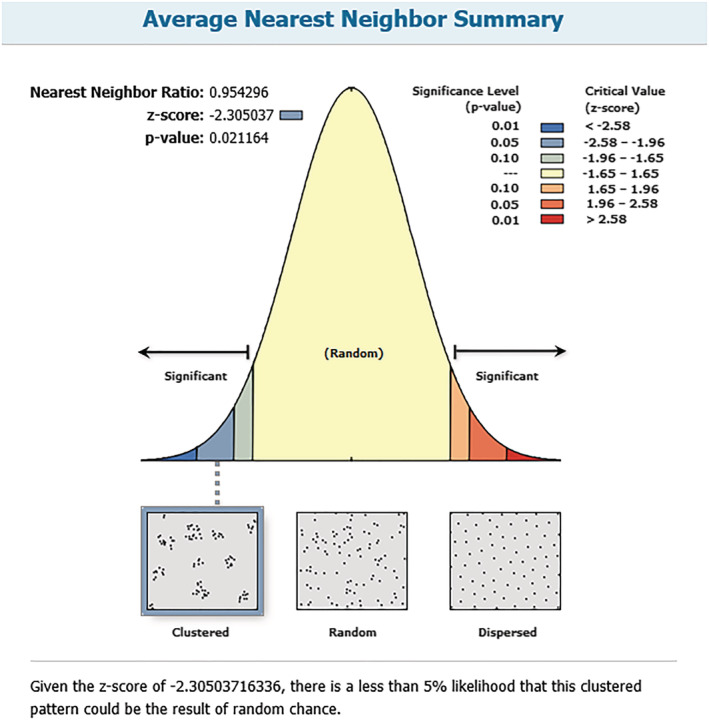

Further, the spatial distribution pattern of COVID‐19 cases was examined by ANN analysis provides the average distance from each point to another within its closest vicinity. The result of ANN shows the nearest neighbour ratio (R), Z‐score, and P values. If the ANN ratio <1, the case pattern is clustered; otherwise, it is dispersed. Similarly, a higher Z‐value indicates a higher degree of a cluster. As of 21 March, the average nearest neighbour ratio was < 1(%) i.e. 0.73 (p = 0.001), it was recorded 0.86 (p = 0.001) on 21 April; 0.92 (p = 0.001) on 21 May and 0.95 (p = 0.02) on 20 June analysis (Figures A5, A6, A7 and A8 respectively); while the Z values for COVID‐19 incident were −4.06, −5.40, −3.39 and −2.30 respectively (Table 1). It means that during the assessment period the pattern of the case was clustered, though it was higher on 21st March as compared to 20th June.

TABLE 1.

Average nearest neighbour summary

| Date | Nearest neighbour ration (NR) | Observed distance | Z‐score | P‐value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 21/3/2020 | 0.73 | 85126.53 | −4.61 | 0.000004 |

| 21/4/2020 | 0.86 | 57642.16 | −5.40 | 0.000001 |

| 21/5/2020 | 0.93 | 52109.96 | −3.39 | 0.000695 |

| 20/6/2020 | 0.95 | 49750.25 | −2.31 | 0.021 |

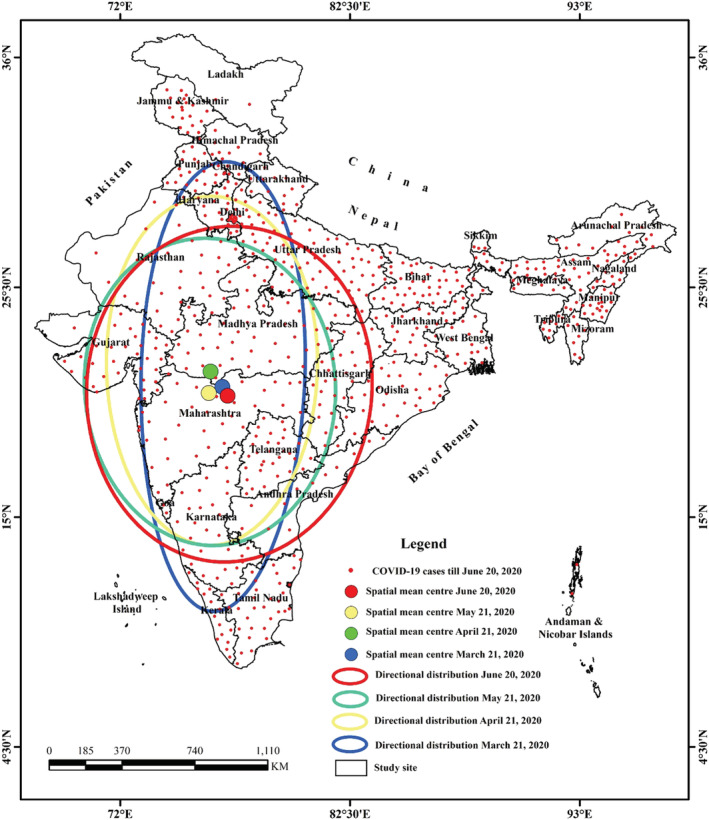

Figure 4 shows the location of COVID‐19 geographic mean centres, directional distribution of COVID‐19 cases for 21 March, 21 April, 21 May, and 20 June. The spatial mean centre is the analysis of the concentration point of any geographical phenomena (Abd Majid, Muhamad Nazi, & Mohamed, 2019). It suggests that all the mean centre of COVID‐19 cases were located very close to the western part of the country with little temporal shifting. The mean centre on 2t March was located at X co‐ordinate 20°57′2.8′′ N and Y co‐ordinate 76°39′47.31′′E (in Buldana district of Maharashtra); whereas for 21 April, it was slightly shifted (127.68 km westward) and located at X co‐ordinate 21°39′1.4′′ N and Y co‐ordinate 76°7′16′′ E (East and West Nimar districts of Madhya Pradesh). However, as of 21 May the mean centre shifted 108.40 km towards South and located at X co‐ordinate 20°40′20.47′′ N and Y co‐ordinate 76°2′4.97′′ E (in Buldana district of Maharashtra) and then again 91 km shifted towards East and located at X co‐ordinate 20°33′2.2′′ N and Y co‐ordinate 76°54′1.42′′ E (in Akola district of Maharashtra) as of 20 June. While the directional distribution of ellipse polygon indicates that initially the spread of COVID‐19 has followed North–South direction and with time it is gradually shifting towards East. Moreover, the ellipse polygon of 21 March has greater length towards North–South direction, which covered 68 percent of the distribution. The standard deviation of the distribution on the X‐axis was 1154.27 km and Y‐axis was 394.14 km, and the ratio between the X and Y axis was 2.93. Whereas, on 20 June it was 689.16 km on X‐axis and 860.98 km on Y‐axis with ratio 0.80. The direction of ellipse appeared that initially (as on 21 March) the distribution of COVID‐19 cases in India was towards North–South direction with 5°22′48″ rotation angle and with time the length of X‐axis has significantly reduced (as on 20 June length reduced by 465.11 km) and similarly Y‐axis length has increased by 466.84 km (Table 2) with rotation angle equal to 7°26′24″. This indicates that the disease is gradually spreading towards the east of the country and more probably in the next phase the direction of the pandemic will appear in the West–East direction.

FIGURE 4.

Spatial mean centre, directional distribution of COVID‐19 cases in India for 21 March, 21 April, 21 May and 20 June, 2020

TABLE 2.

Summarizes the characteristics of standard deviational ellipse of the COVID‐19 cases in India

| Date | Location of mean centre | Ellipse size of the Epidemics | Orientation of the ellipse | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean centre (X) | Mean Centre (Y) | X std. distance (km) | Y std. distance (km) | ||

| 21/3/2020 | 20°57′2.8′′ N | 76°39′47.31′′E | 1154.27 | 394.14 | 5°22′48” |

| 21/4/2020 | 21°39′1.4′′ N | 76°7′16′′ E | 896.98 | 506.6 | 4°12′36” |

| 21/5/2020 | 20°40′20.47′′ N | 76°2′4.97′′ E | 606.90 | 790.00 | 0°48′0” |

| 20/6/2020 | 20°33′2.2′′ N | 76°54′1.42′′ E | 689.16 | 860.98 |

7°26′24” |

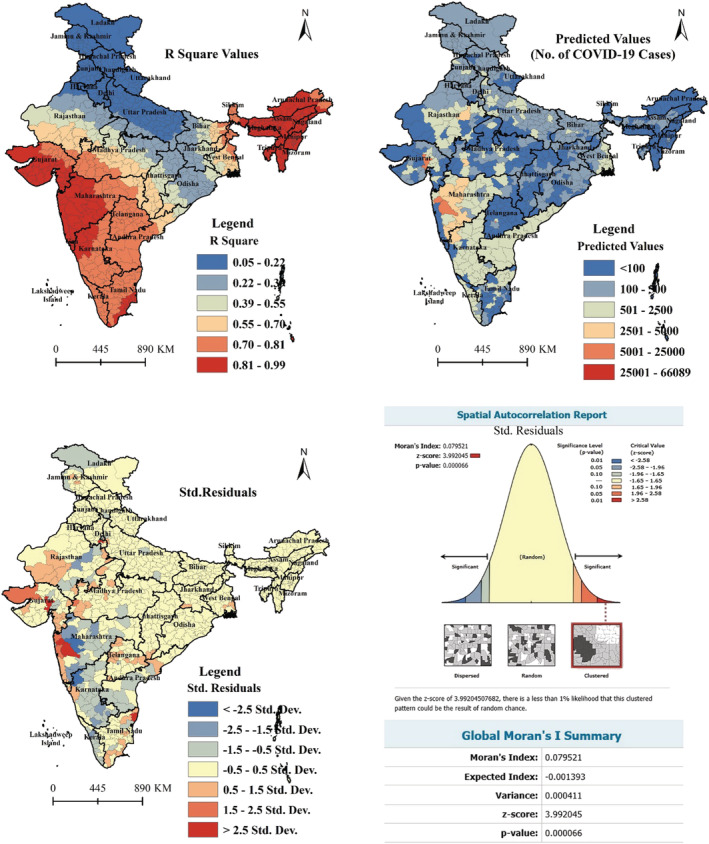

The GWR model indicates that population density, the total number of the populations, health infrastructure, sub centres, primary health care (PHC) and community health centre (CHC) have explained more than 89 percent (R2 = 0.89) of total variance at the country level of COVID‐19 affected cases. Moreover, Figure 5 shows the spatial pattern of R2 which indicates that almost the entire south‐eastern part of the country’s COVID‐19 is explained by the selected explanatory variables. Further, the standard residuals from the GWR are spatially random (Moran’s I = − 0.07; z = 3.99; p < 0.001), implying that there are other factors which also affects the COVID‐19 affected cases in district level. The residuals map also shows that COVID‐19 affected cases are underestimated primarily in the western part of the country (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5.

Spatial pattern of local R2, predicted, and standard residuals from the GWR model of COVID‐19 affected cases (20 June, 2020)

3.3. Spatio‐temporal trend and intensification of COVID‐19 in India

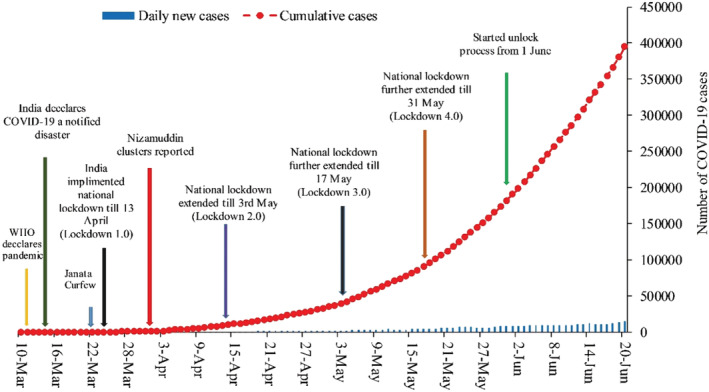

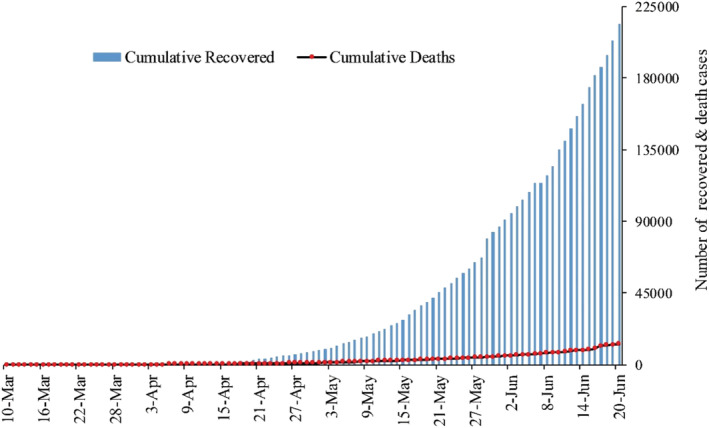

Although India registered the first COVID‐19 case in the last of January 2020 in Kerala, the number of new confirmed cases in India was very less till 21 March, 2020. From the beginning of April, the number of newly confirmed cases increased rapidly. Till the study period, India registered maximum fresh positive cases on 20 June (14,516 cases) and maximum deaths for a single day was on 17 June (2003 cases). The daily cumulative and new confirmed cases from up to the 20 June 2020 are summarized in figure 6. This figure shows that the curve of cumulative positive cases left the ground in the first week of April. The gap between the ground and the curve rapidly increased day by day and the curve got steeper slope as the days passed by. After 143 days from the date of the first COVID‐19 case reported in the country, India recorded 12,948 death cases (3.27%) and 213,831 recovered (54.12%) cases (as of 20 June). Out of the total cases, 79.25 percent of the cases were reported in the last 36 days of the study period. As of 1st April 2020, the percentage of recovered and death cases was 10.33 percent and 2.32 percent respectively. However, more than 50 percent of infected individuals (54.06%) have recovered till 20 June 2020 and the fatality rate was about 3.27 percent. Percentage of recovered enhanced by 6.37 percent in the last 20 days and an amount of casualty likewise followed a lower pattern in comparison of other infected nations, which ascribed to the update of diagnostic measures and health care service facilities for COVID‐19 in India. Figure 7 represents the trend of recovered and death cases in India for the entire period of the study.

FIGURE 6.

Temporal trend of reported COVID‐19 cases in India from 10 March to 20 June, 2020

FIGURE 7.

Changes in number of cumulative recovered and death in India from 10 March to 20 June, 2020

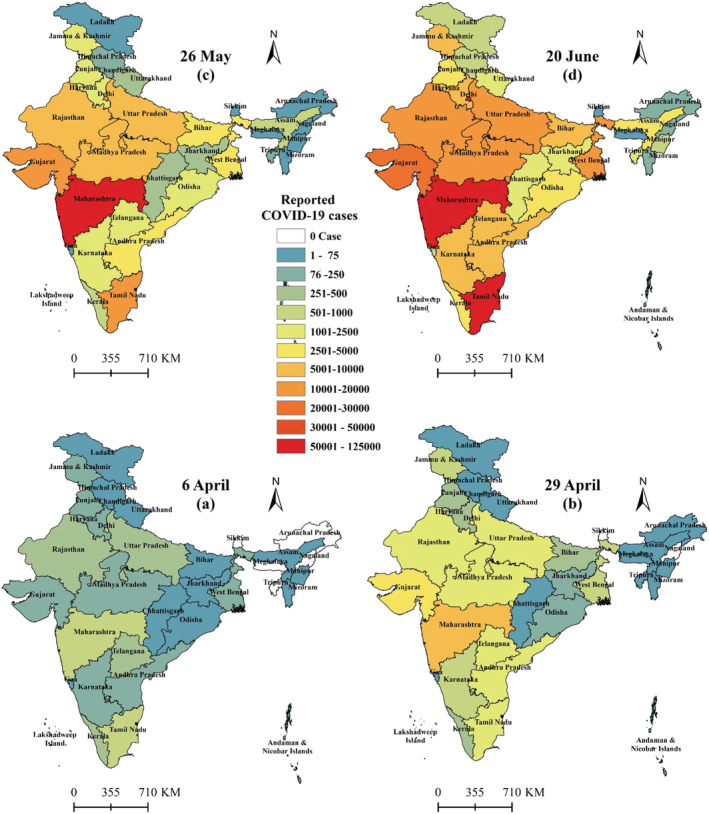

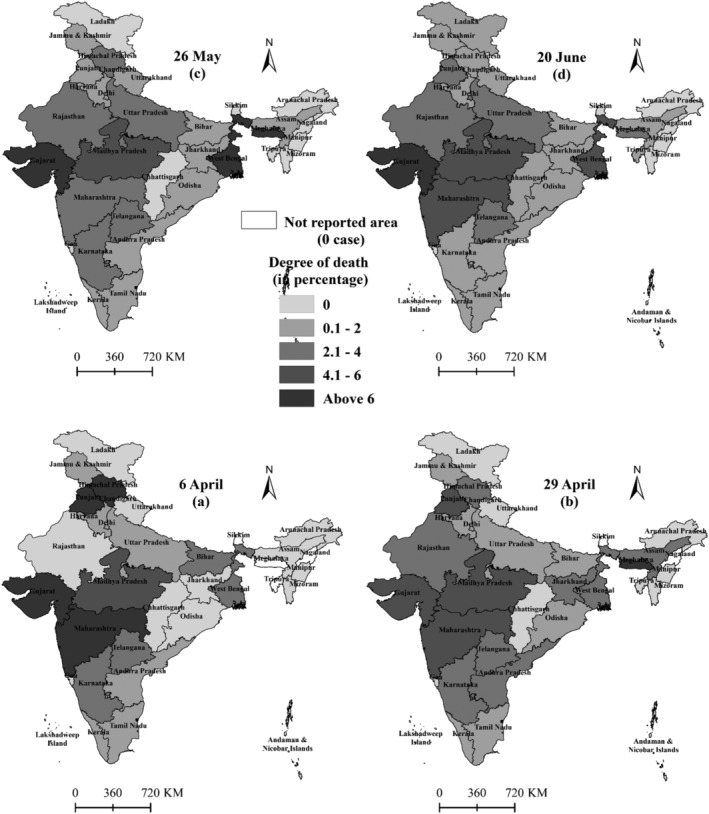

The spatial spread of COVID‐19 cases differs according to the situation of the states and districts and the geographic range of the cases has increased with each passing day. Figure 8 shows the spatial distribution of COVID‐19 cases among the districts of India from 21 March to 20 June. At the districts level, 41.94 percent cases were concentrated in six districts namely South Delhi (1,363), Ahmedabad (1,298), Pune (660), Mumbai (3029), Indore (915) and Jaipur (537) as of 21 April, however, 299 districts were not affected by COVID‐19 disease (Figure 6d). While almost 96.67 percent districts are affected by COVID‐19 disease as on 20 June and more than 50 percent cases are concentrated in seven districts namely South Delhi (34,840), Ahmedabad (18,837), Pune (15,881), Mumbai (66,484), Indore (915) and Chennai (39,470), which clearly shows an uneven distribution across the country. Whereas in the state level, till 6 April three states reported more than 500 cases (Maharashtra‐748, Delhi‐523, Tamilnadu‐517), while on 29 April twelve states registered more than 500 cases (Andhra Pradesh‐1,259, Delhi‐3,314, Gujarat‐3,744, Maharashtra‐9,318, Madhya Pradesh‐2,387, Rajasthan‐2,364, Uttar Pradesh‐2053, Tamil Nadu‐2058, Telengana‐1,004, West Bengal‐725, Karnataka‐523, Jammu & Kashmir‐565). However, with the passage of time, outbreak spread rapidly and fourteen new states were added namely Kerala, Odisha, Haryana, Bihar, Punjab, Ladakh, Chhattisgarh, Goa, Jharkhand, Manipur, Tripura, Uttarakhand, Assam, and Himachal Pradesh in the list of more than 500 positive cases as on 20 June. Among which 81.24 percent of COVID‐19 cases concentrated in seven states (namely Delhi−53,116, Gujarat‐ 26,141, Maharashtra‐ 124,331, Madhya Pradesh‐ 11,582, Rajasthan‐ 14,156 and Tamil Nadu‐54,449, Uttar Pradesh‐15785, West Bengal‐13,090), of which independently Maharashtra accounting 31.47 percent (one‐third) of the total cases with 45.51 percent deaths in India. On the other hand, Lakshadweep, Daman, Diu have not registered any confirmed COVID‐19 case till 20 June 2020 (Figure 9).

FIGURE 8.

District wise spatio‐temporal variation of reported COVID‐19 cases in India (21 March to 20 June, 2020)

FIGURE 9.

State‐wise spatio‐temporal variation of COVID‐19 cases in India (6 April to 20 June, 2020)

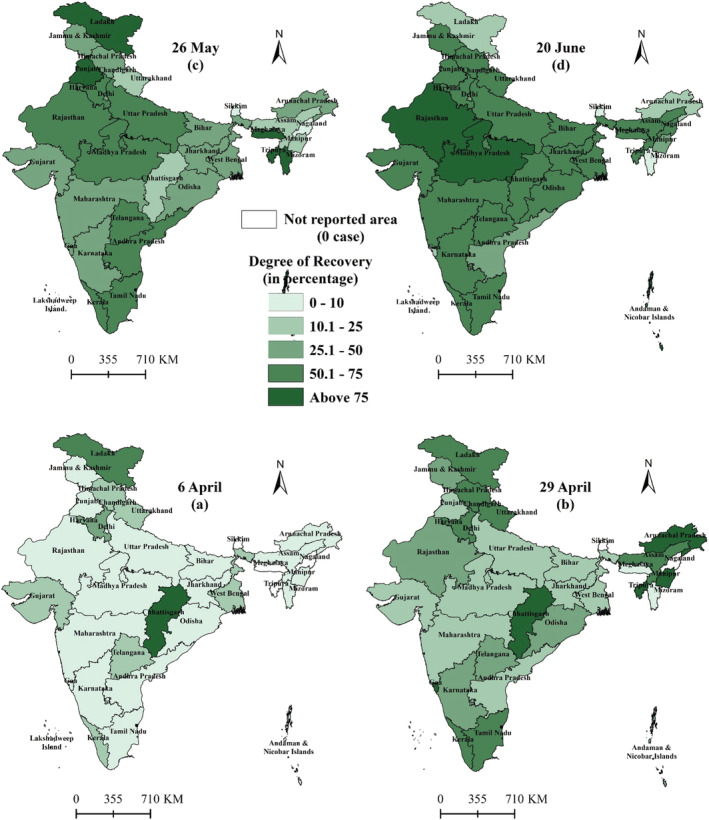

The spatiotemporal pattern of deaths and recovered cases in India has been shown in Figures 10 and 11 respectively. The recovered and morbidity rates of any pandemic in any area generally relies upon the procedures to fight against the circumstance just as on the regional elements, ecological conditions, financial structure, social awareness and medicinal facilities of that district. In India Kerala, Goa and Manipur are some of the states which are quite successful in preventing the rapid spread of the positive cases. On the other side, in the case of deaths, Gujarat (6.19%), Madhya Pradesh (4.27%), West Bengal (4.04%) and Maharashtra (4.74%) reported more than 4 percent fatality rate as on 20 June. However, within the study period, no death case has reported from Andaman and Nicobar Islands, Dadra and Nagar Haveli, Goa, Manipur, Mizoram, Sikkim, Nagaland and Arunachal Pradesh. On the other hand, fifteen states/UTs namely Andaman & Nicobar (77.78%), Chhattisgarh (65.63%), Meghalaya (75%), Chandigarh (82.68%), Madhya Pradesh (75.53%), Rajasthan (77.69%), Gujarat (69.49%), Himachal Pradesh (62.68%), Bihar (70.99%), Odisha (70.49%), Punjab (68.78%), UP (61.06%), Uttarakhand (65.82%), Nagaland (63.13%) and Assam (61.98%) reported more than 60 percent recovered cases. However, Ladakh (12.76%), Goa (16.28%), Mizoram (0.77%), Sikkim (7.14%), Arunachal Pradesh (10.68%), Dadra and Nagar Haveli (22.58%) reported significantly low recovered cases in India.

FIGURE 10.

State‐wise spatio‐temporal variation of COVID‐19 death cases in India (6 April to 20 June, 2020)

FIGURE 11.

State‐wise spatio‐temporal variation of recovered cases in India (6 April to 20 June, 2020)

3.4. Regression analysis and prediction of COVID‐19 cases in India

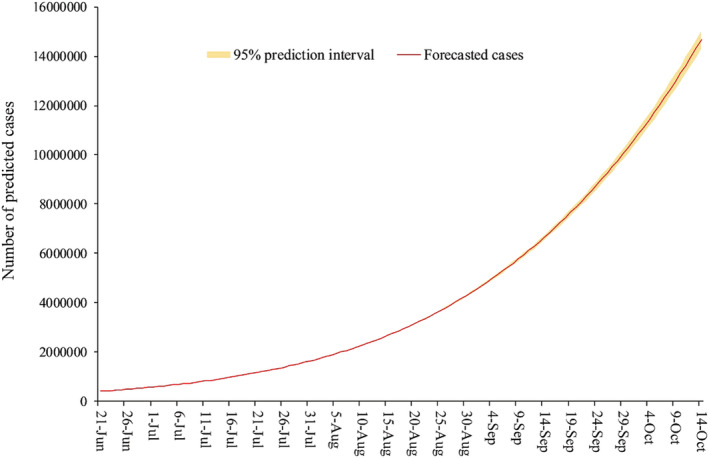

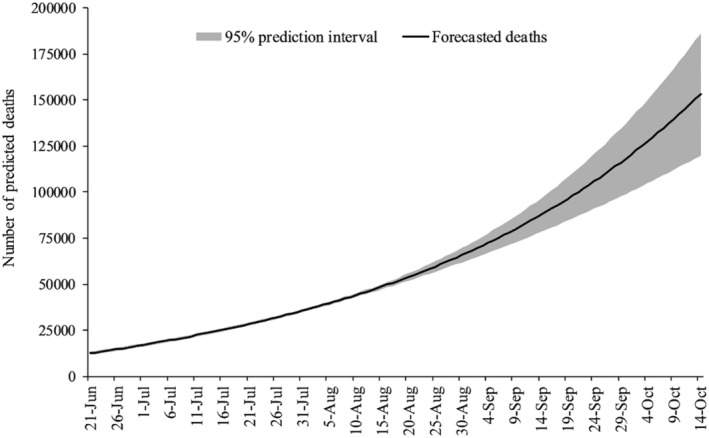

As we are probably aware of the fact that COVID‐19 is an infectious disease with a high transmission rate (Pandey et al., 2020) and there was no significant development in the quantity of COVID‐19 cases in India before March 2020, in this manner, 80 days training data at which the disease grows and reported noteworthy deaths (from 2 April to 20 June 2020) has been utilized to investigate the future pattern of the pandemic in India. To check the validation of the model, 10 days’ actual data (21 June to 30 June 2020) has been used and root means square log error (RMSLE) has been calculated. The RMSLE for both of the predicted confirmed cases and death cases is 0.002 and 0.017 respectively (see Table A1 and A2). Table A3 shows the prediction result of the number of confirmed cases and death cases in India using the polynomial regression model. The predicted result shows that on 14 October 2020, the number of COVID‐19 cases in India will reach 14,660,400 positive cases (which are near 1.21 percent of the total population) and 152,945 death cases. Figure 12 & 13 shows the day‐wise prediction of COVID‐19 positive cases and deaths in India respectively, with the 95 percent prediction interval from 21 June to 14 October 2020.

FIGURE 12.

Prediction of number of COVID‐19 patients in India till 14 October, 2020 (actual values are recorded till 20 June, 2020)

FIGURE 13.

Prediction of number of deaths by COVID‐19 infection in India till 14 October, 2020 (actual values are recorded till 20 June, 2020)

3.5. India’s response to the COVID‐19 pandemic

In the last week of January 2020, China was suffering from the COVID‐19 pandemic (Li et al., 2020). On 29 January the Indian Health Ministry advised Indians not to travel to China. After confirming the first case of the country on 30 January, the Government of India (GoI) announced to screen all the travellers who came from China after 15 January. Following the second positive case, GoI decided to cancel all the e‐visa facilities for the Chinese as well as for all the foreigners who are residing in China. Observing the situation, India started preparing for its upcoming battle against this virus. However, in this study, India’s response of the COVID‐19 pandemic was divided into two‐part, the first part will discuss the positive measures taken in India; the second part will focus on the lack of policy design to confront the COVID‐19 pandemic.

The government along with other institutions began to spread social awareness among the target population through the distribution of pamphlets, mass SMS and media. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs, India had suspended all the visas on or before 3 March to the nationals of Italy, Iran, South Korea, and Japan after confirming the confirmed cases of 21 Italian tourists along with their Indian bus driver, conductor and tourist guide (The Hindu, 4 March 2020). Observing the growing confirmed cases, the GoI officially decided not to celebrate the Holi 2 festival to avoid the gatherings and it was a message to all the residents of the country to be aware of the outbreak of COVID‐19. To contain the human to human transmission the government declared shut all the schools and colleges till 31 March in the state. On 13 March 2020, the Indian government imposed a strict travel restriction and suspended gatherings of 200 people and essentially closed its international and regional borders. The visas were revoked refuting entry to all except selective foreigners.

Moreover, based on WHO guidelines, mandatory thermal screening was setup at air and seaports for all passengers. Following the rapid growth rate of positive cases, shopping malls, theatres, and educational institutions were closed. On the other hand, all religious gatherings and festivals were also banned in India. The National Restaurant Association of India (NRAI) issued an advisory to all its members to shut down their restaurants from 18 to 31 March, 2020.

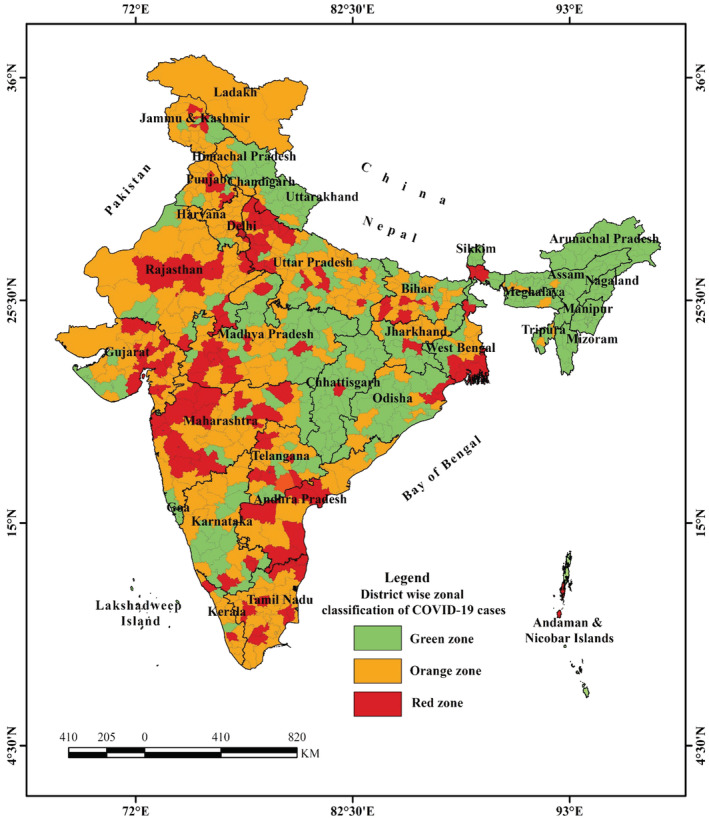

However, on 19 March, India calls for social distancing and appealed for “Janata Curfew” on 22 March (The Hindu, 20 March 2020). Day after the “Janata Curfew” GoI announced to stop all the domestic flights till the end of March to contain the inter‐state transmission. On the evening of 24 March, GoI announced a nationwide lockdown for 21 days till 14 April. It was the first phase of lockdown to contain the outbreak of this deadly virus in the country. According to reports from the Union Health Ministry of India, the death toll rose to 339, with 10,363 cases overall till 14 April, the last day of lockdown. On the same day observing the rapid growth of COVID‐19 positive cases, GoI extended the lockdown period till 3 May as the second phase of it, that is, “Lockdown 2.0”. During this lockdown period government strictly restricted outward movement of population from the containment zone except for maintaining essential services (including medical emergency) and stopped all vehicular movement, public transport, and personnel movement across the country. All the district headquarters provided helpline numbers for the preventive measures required and the need for prompt reporting to health facilities, availability of essential services, and administrative orders. Keeping in view of the growing number of positive cases, GoI extended “Lockdown 3.0” till 17 May followed by “Lockdown 4.0” up to 31 May. The WHO praised India’s COVID‐19 national lockdown as “tough and timely.” The Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW), Government of India identified 123 hotspot districts with large outbreaks on 15 April 2020 based on reported cases and directed the concerned state governments to follow the similar way of identification of hotspots in state level and repeat this exercise every week for implementing strict containment measures. In addition, government‐designated red, orange and green zones considering multiple factors taking into consideration the number of cases, doubling rate, the extension of testing and surveillance feedback to classify the districts (Figure 14). The districts will be labelled as green zone if there are no confirmed cases since the last 21 days. Whereas, the red zones or hotspot districts are defined after taking into account the total number of active cases, doubling rate of confirmed cases, the extent of testing, and surveillance feedback, while rest of the districts that are neither defined as red or green will be considered as the orange zone. In green zones, government permitted all activities except the limited number of activities that are banned throughout the country irrespective of the zones. However, buses can function with up to 50 percent seating capacity. These benevolent precautionary measures mainly played a significant role to contain the pandemic in India compared to other affected countries worldwide.

FIGURE 14.

District wise zone classification of COVID‐19 cases in India (The Union Health Ministry on first May, 2020 listed 130 districts in red zone, 284 in the orange zone and 319 in the green zone for a week after 3 May, 2020)

Further, after imposing the lockdown, the GoI announced a relief package of Rs 1.7 lakh crore. These included five kilograms of wheat or rice and one kilogram of pulses to each low‐income family, free cooking gas cylinders to 83 million poor families, one‐time cash transfers of $13.31–$30 to senior citizens and $6.65 per month to the poor women through Jandhan's account and medical insurance of $66,000 to all the frontline doctors, nurses and paramedics to the sanitary workers (World economic forum, 2020).

However, apart from the above positive measures, there are many shortcomings of the government's response to confront the COVID‐19 Pandemic. The GoI has been facing criticism in different angles from the experts. Here, the study also points out the lacuna of India’s measures in combating the COVID‐19 Pandemic.

First, in spite of the primary warning from the WHO in January, 2020, the Indian government showed a woeful delay in banning entry to international borders and airports. Moreover, the imposed lockdown didn’t have a transparent roadmap and operational preparedness. The sudden announcement did not consider the possible adverse effects in the near future, especially the livelihood of the poor. The GoI announced a lockdown on 24 March 2020, at 8.00 pm and gave 1.38 billion people within the country just four hours to get ready. It has been widely reported from different areas that being the second‐most populous country in the world with a large number of poor households. It might not be possible for the people of India to cope mentally and physically with the sudden noticed of the government to impose full lockdown.

Second, as a result of sudden imposed lockdown due to the COVID‐19 pandemic, thousands of migrant workers working across the Indian state were forced to stay in their workplace from the very beginning of the pandemic. The GoI did not take any positive step to return the stuck workers 3 to their homes initially; as the lockdown period continued to enhance, they reached the brink of economic problems and lost their jobs and livelihood. The thousands of labourers in unorganized sectors in the cities were forced to leave their workplace and they started travelling hundreds of miles towards their rural homes on foot. It is well evident that many people died due to inadequate supply of clean drinking water and food on the road. Eventually, the GoI took some initiative to bring them back home, but it was executed without a constructive plan. As a result, lots of workers were forced to return home at peak times; and it was impossible to maintain social distancing during the process of journey, where many migrant workers were reported to be COVID‐19 positive.

Third, the relief package provided by the GoI was criticized as inadequate, it was only 10 percent of the GDP, and it was not distributed among the people through the effective mechanized distribution system. As a result, the people gave more importance to the upcoming hunger trap than to COVID‐19 epidemics. In India, there are large numbers of people who live below the poverty level, who have been facing food insecurity. The food distribution systems during the pandemic created turmoil across the country. The tragic and heart breaking incidents regarding public distribution systems could have been abolished if the government had announced a special economic package for people. At the same time, they reassured fellow citizens positively about their difficulties. 4 During the lockdown period, the cost of daily necessities also went up, whereas the unemployed poor couldn”t buy enough necessary items due to insufficient income.

Fourth, with the passage of time, coronavirus spread to every pocket of the country; the rural people have become more vulnerable as a combined result of economic catastrophe and virus outbreak. In India, 450 million internally migrated from rural to urban areas. A large number of people from Uttar Pradesh (UP) and Bihar followed by Madhya Pradesh (MP) and other states have less accessibility to health care and more exposed to the present pandemic situation. Those who reached their native villages were seen as potential carriers of the infection and were ill‐treated by the police and locals. About 30 percent of migrant workers work as casual workers, and are therefore quite vulnerable to the vagaries of the labour market, and lack of social protection. The local administration failed to do this. The International Labour Organization has projected that 400 million people in India have fallen into poverty.

Fifth, the most vulnerable section would be rural poor people, who do not have either security of employment or any social protection. A large number of rural poor have been surviving on subsistence agricultural practices. 5 The rural population is served by smaller number of professionals or proper medical infrastructure at the same time transport systems were closed due to lockdown which prevented them to move out to the nearest cities to avail them. Therefore, Coronavirus affected the rural population more and they are much vulnerable due to both their poor economic condition as well as poorly design government policy.

Sixth, the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) can perform as useful tool to handle pandemic related distress, ensuring social stability. However, the GoI is working hard on creating work in rural areas through MGNREGA. Although there have been cash transfers among rural people, it is insufficient compared to India’s population size (Nandy, 2020; Verma, 2020). However, MGNREGA has a restriction of 100 days guaranteed employment and it also does not cover urban unemployment during this pandemic.

Seventh, the survey reports during and post lockdown period mentioned that small and medium industry sector have been affected greatly and large number of worker engaged with these sectors has lost their jobs. However, small and micro enterprises failure due to pandemic creates economic and also social tensions. The GoI needs to support and create lucid banking credit systems for these sectors in the post lockdown period.

4. CONCLUSION AND POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS

In this study, the spatio‐temporal pattern of the COVID‐19 outbreak has been analysed and excavated at the ground level in India. We found that the spatial spread of COVID‐19 cases significantly varies in states and districts levels, such as the three states reported more than 50 percent (58.70%) of the total cases with 66.37 percent deaths in India. From the spatio‐temporal analysis, it is quite evident that any radical change of characteristics is not found during the study period in most of the areas. Nevertheless, 17 epicentres with more than 700 cases were detected across the country located around South Delhi, Agra, Lucknow and Kanpur in the Northern region; Mumbai, Thane, Pune, Surat, Ahmedabad, Jaipur, Jodhpur in the Western region; Hyderabad, Chennai, Kurnool in the Southern region, Bhopal, Indore in the central region; and Kolkata in the Eastern region. It has been found through hotspots analysis that there is a clustering tendency of COVID‐19 cases in the 60 districts, which are located in the western part of the country (Maharashtra and Gujarat). The pattern distribution analysis found that the clustered pattern is dominant in COVID‐19 cases, with an average ANN ratio of less than 1. The spread of COVID‐19 has a similar course all through the period of analysis and the western part of the country seems to be the most concentrated part. The mean focal points of the COVID‐19 cases were located very close to the western part of the country with little shifting towards the east of the nation even if it is minimal. Besides, the time series analysis uncovers that in the initial phase, India followed a moderate development of affected cases contrasted with different nations and her extreme size of the population. The pattern of COVID‐19 affected cases growth follows 4th order polynomial growth and the outbreak has started to spread rapidly throughout the country from the last three weeks. Therefore, India will enter into a pandemic situation in a short time taken. The prediction results show that as on 14 October India will cross 14.66 million COVID‐19 cases which is ~1.21 percent of the total population.

Finally, in these challenging times, the Indian government is trying to perform soundly compared to the other countries. The rate of positive cases has been controlled by taking different steps taken by the central as well as the state governments. However, a pragmatic approach has taken after considering both the health and economic aspects of the country. As a developing country, to continue its economic growth engine partial lockdown strategy has taken is in a relatively safe zone. The partial lockdown is also showing satisfactory response from different parts of the country also having its negative impacts. Moreover, the government should implement additional measures for the hotspot region of COVID‐19 cases along with expanding the healthcare facilities (testing kits, ventilators and other medical equipment) and implementing proper policies for the poor people. Quick testing is important to contain COVID‐19 cases inside the affected zones.

Further, the study has recommended some policies to minimize the COVID‐19 transmission and reduce the livelihood generation problems in India, which are as following:

The existing and newly announced welfare schemes by GoI have to be more effective and economically strong to handle the pandemic until a vaccine is developed. The government must plan to create new relief packages that protect farmers, migrant workers, and day labourers. The public distribution systems need to be fair and reached the needy. The GoI has the surplus grain stock; the distribution of this surplus food grain could be an alternative way to deal with the crisis. In India, considering its high population and poverty, the government should ensure that people do not die due to hunger or starvation.

The growth of the Indian economy is heavily dependent on the unorganized sector, which is negatively hit by the COVID‐19 pandemic. In order to revive economic growth and lost livelihoods, the government should take immediate steps to address the most affected economic sectors and prepare and implement some effective policies. For example, tourism industries need financial support from the government to be thrive, because these sectors have suffered most due to the COVID‐19 imposed lockdown.

Moreover, the government should provide proper and adequate safety gear such as hand‐wash, sanitizers, masks, etc. to the all COVID‐19 “warriors” (health workers and police) and ensure good quality masks for the poor at low prices through ration shops. Besides, arrangement of adequate beds and keeping the entire required instruments in the healthcare centre should be ensured.

India has the lowest per capita ICU bed rations in the world health system (2.3 beds/100,000 population) along with a lack of adequately trained staff. The huge rural and poor population are hopelessly heading towards a catastrophic health crisis. In such a situation, the government has to formulate a health care policy.

In India, it has been noticed that emergency patients with high fever or breathing difficulties are facing lots of problems at the time of admission in the hospital due to similar symptoms of COVID‐19. The large numbers of such patients are returned without admission or without minimum treatment. The major government hospitals working with the COVID‐19 virus have stopped treating patients with other diseases. Therefore, it has become a concern area for COVID‐19 related health policy in India. There is a need to separate facilities for COVID‐19 and non‐COVID‐19 patients during this crisis.

The GoI needs to increase the healthcare infrastructure in rural India to deal with the epidemic and establish good co‐ordination to meet the basic medical needs of people.

The government should conduct door‐to‐door testing facilities to trace COVID‐19 patients and isolate of the symptomatic as well as asymptomatic persons, because it has noticed that patients with no symptoms are also likely to spread the infection.

In India, it has evidence that a large section of people is not aware enough about the epidemic and social distance rule is not properly maintained. Even the people are not wearing face masks and found to be spitting here and there. Therefore, the government should take adequate measures on such issues and at the same time need to spread consciousness about the COVID‐19 among the people.

The streets and markets in India are overcrowded, the government needs to make new policies for grocery shops, that is, they will remain open on alternate days to reduce overcrowding.

The government should also set up a task force to take strict action against black marketers in order to provide relief to the public.

APPENDIX A.

TABLE A1.

Root mean square log error (RMSLE) for total cases

| Date | Actual Values | Predicted Cases | Actual+1 | Predicted+1 | Log (Actual) | Log (Predicted) | Error (Difference) | Squared Error |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 21/6/2020 | 410,461 | 410,674 | 410,462 | 410,675 | 5.613272957 | 5.613498266 | −0.000225309 | 0.0000001 |

| 22/6/2020 | 425,282 | 425,431 | 425,283 | 425,432 | 5.628678023 | 5.628830153 | −0.000152131 | 0.0000000 |

| 23/6/2020 | 440,215 | 440,669 | 440,216 | 440,670 | 5.643665823 | 5.644113486 | −0.000447662 | 0.0000002 |

| 24/6/2020 | 456,183 | 456,407 | 456,184 | 456,408 | 5.659140049 | 5.659353248 | −0.000213199 | 0.0000000 |

| 25/6/2020 | 473,105 | 472,666 | 473,106 | 472,667 | 5.674958456 | 5.674555282 | 0.000403173 | 0.0000002 |

| 26/6/2020 | 490,401 | 489,467 | 490,402 | 489,468 | 5.690552233 | 5.689724304 | 0.000827929 | 0.0000007 |

| 6/27/2020 | 508,953 | 506,831 | 508,954 | 506,832 | 5.706678532 | 5.704864027 | 0.001814505 | 0.0000033 |

| 6/28/2020 | 528,859 | 524,781 | 528,860 | 524,782 | 5.723340721 | 5.71997893 | 0.00336179 | 0.0000113 |

| 6/29/2020 | 548,318 | 543,341 | 548,319 | 543,342 | 5.739033295 | 5.735073277 | 0.003960018 | 0.0000157 |

| 6/30/2020 | 566,840 | 562,533 | 566,841 | 562,534 | 5.753461256 | 5.750148777 | 0.003312479 | 0.0000110 |

| Mean | 0.0000042 | |||||||

| RMSLE= | 0.002059517 | |||||||

TABLE A2.

Root Mean Square Log Error (RMSLE) for death case

| Date | Actual values | Predicted cases | Actual+1 | Predicted+1 | Log (actual) | Log (predicted) | Error (difference) | Squared error |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 21/6/2020 | 13,254 | 12,572 | 13,255 | 12,573 | 4.122380 | 4.099422 | 0.022958 | 0.0005271 |

| 22/6/2020 | 13,699 | 12,990 | 13,700 | 12,991 | 4.136721 | 4.113649 | 0.023071 | 0.0005323 |

| 23.6/2020 | 14,011 | 13,416 | 14,012 | 13,417 | 4.146500 | 4.127659 | 0.018841 | 0.0003550 |

| 24/6/2020 | 14,476 | 13,849 | 14,477 | 13,850 | 4.160679 | 4.141453 | 0.019226 | 0.0003696 |

| 25/6/2020 | 14,894 | 14,289 | 14,895 | 14,290 | 4.173041 | 4.155038 | 0.018002 | 0.0003241 |

| 26/62020 | 15,301 | 14,737 | 15,302 | 14,738 | 4.184748 | 4.168424 | 0.016324 | 0.0002665 |

| 27/6/2020 | 15,685 | 15,191 | 15,686 | 15,192 | 4.195512 | 4.181618 | 0.013894 | 0.0001931 |

| 28/6/2020 | 16,095 | 15,653 | 16,096 | 15,654 | 4.206718 | 4.194623 | 0.012095 | 0.0001463 |

| 29/6/2020 | 16,475 | 16,122 | 16,476 | 16,123 | 4.216852 | 4.207449 | 0.009403 | 0.0000884 |

| 30/6/2020 | 16,893 | 16,599 | 16,894 | 16,600 | 4.227732 | 4.220100 | 0.007632 | 0.0000583 |

| Mean | 0.0002861 | |||||||

| RMSLE= | 0.0169132 | |||||||

TABLE A3.

Predicted number of COVID‐19 patients in India till 14 October, 2020

| Date | Prediction cases | Std. error | 95% interval | Prediction death | Std. error | 95% interval | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| lower limit | upper limit | lower limit | upper limit | |||||

| 21/6/2020 | 410,674 | 4630.06 | 401,478 | 419,869 | 12,572 | 413.229 | 11,751 | 13,392 |

| 22/6/2020 | 425,431 | 4629.18 | 416,237 | 434,625 | 12,990 | 413.15 | 12,170 | 13,811 |

| 23/6/2020 | 440,669 | 4628.11 | 431,477 | 449,861 | 13,416 | 413.055 | 12,596 | 14,237 |

| 624/6/2020 | 456,407 | 4626.9 | 447,217 | 465,596 | 13,849 | 412.947 | 13,029 | 14,669 |

| 25/6/2020 | 472,666 | 4625.6 | 463,479 | 481,853 | 14,289 | 412.831 | 13,469 | 15,109 |

| 26/6/2020 | 489,467 | 4624.28 | 480,282 | 498,651 | 14,737 | 412.713 | 13,917 | 15,556 |

| 27/6/2020 | 506,831 | 4,623 | 497,649 | 516,013 | 15,191 | 412.598 | 14,372 | 16,011 |

| 28/6/2020 | 524,781 | 4621.82 | 515,602 | 533,961 | 15,653 | 412.493 | 14,834 | 16,472 |

| 29/6/2020 | 543,341 | 4620.81 | 534,163 | 552,518 | 16,122 | 412.403 | 15,303 | 16,941 |

| 30/6/2020 | 562,533 | 4620.04 | 553,357 | 571,708 | 16,599 | 412.335 | 15,780 | 17,418 |

| 1/7/2020 | 582,382 | 4619.57 | 573,207 | 591,557 | 17,083 | 412.293 | 16,264 | 17,902 |

| 2/7/2020 | 602,913 | 4619.45 | 593,738 | 612,088 | 17,574 | 412.282 | 16,756 | 18,393 |

| 73/72020 | 624,152 | 4619.72 | 614,977 | 633,327 | 18,074 | 412.305 | 17,255 | 18,893 |

| 4/7/2020 | 646,125 | 4620.41 | 636,948 | 655,301 | 18,581 | 412.367 | 17,762 | 19,400 |

| 5.7/2020 | 668,859 | 4621.54 | 659,680 | 678,037 | 19,095 | 412.468 | 18,276 | 19,915 |

| 6/7/2020 | 692,381 | 4623.11 | 683,199 | 701,563 | 19,618 | 412.609 | 18,799 | 20,437 |

| 7/7/2020 | 716,721 | 4625.11 | 707,535 | 725,906 | 20,149 | 412.787 | 19,329 | 20,968 |

| 8/7/2020 | 741,906 | 4627.51 | 732,715 | 751,096 | 20,687 | 413.001 | 19,867 | 21,508 |

| 9/7/2020 | 767,966 | 4630.25 | 758,770 | 777,162 | 21,234 | 413.246 | 20,414 | 22,055 |

| 10/7/2020 | 794,933 | 4633.27 | 785,731 | 804,135 | 21,790 | 413.515 | 20,968 | 22,611 |

| 11/7/2020 | 822,835 | 4636.48 | 813,627 | 832,044 | 22,353 | 413.801 | 21,532 | 23,175 |

| 12/7/2020 | 851,706 | 4639.78 | 842,491 | 860,921 | 22,926 | 414.096 | 22,103 | 23,748 |

| 13/7/2020 | 881,577 | 4643.06 | 872,356 | 890,799 | 23,507 | 414.389 | 22,684 | 24,330 |

| 14/7/2020 | 912,481 | 4646.21 | 903,254 | 921,709 | 24,097 | 414.67 | 23,273 | 24,920 |

| 15/7/2020 | 944,452 | 4649.09 | 935,219 | 953,686 | 24,696 | 414.927 | 23,872 | 25,520 |

| 16/7/2020 | 977,524 | 4651.59 | 968,285 | 986,762 | 25,304 | 415.151 | 24,479 | 26,128 |

| 17/7/2020 | 1,011,730 | 4653.61 | 1,002,490 | 1,020,970 | 25,921 | 415.33 | 25,097 | 26,746 |

| 18/7/2020 | 1,047,110 | 4655.04 | 1,037,860 | 1,056,350 | 26,548 | 415.459 | 25,723 | 27,374 |

| 19/7/2020 | 1,083,690 | 4655.85 | 1,074,450 | 1,092,940 | 27,185 | 415.53 | 26,360 | 28,010 |

| 20/7/2020 | 1,121,520 | 4,656 | 1,112,280 | 1,130,770 | 27,831 | 415.544 | 27,006 | 28,657 |

| 21/7/2020 | 1,160,630 | 4655.54 | 1,151,390 | 1,169,880 | 28,488 | 415.503 | 27,663 | 29,313 |

| 22/7/2020 | 1,201,060 | 4654.61 | 1,191,820 | 1,210,310 | 29,154 | 415.419 | 28,329 | 29,980 |

| 23/7/2020 | 1,242,850 | 4653.4 | 1,233,610 | 1,252,090 | 29,831 | 415.312 | 29,007 | 30,656 |

| 24/7/2020 | 1,286,040 | 4652.25 | 1,276,800 | 1,295,280 | 30,519 | 415.209 | 29,694 | 31,344 |

| 25/7/2020 | 1,330,660 | 4651.65 | 1,321,420 | 1,339,900 | 31,217 | 415.156 | 30,393 | 32,042 |

| 26/7/2020 | 1,376,760 | 4652.23 | 1,367,520 | 1,386,000 | 31,927 | 415.208 | 31,102 | 32,751 |

| 27/7/2020 | 1,424,380 | 4654.84 | 1,415,140 | 1,433,630 | 32,647 | 415.441 | 31,822 | 33,472 |

| 28/7/2020 | 1,473,570 | 4660.56 | 1,464,310 | 1,482,820 | 33,379 | 415.951 | 32,553 | 34,205 |

| 29/7/2020 | 1,524,350 | 4670.72 | 1,515,080 | 1,533,630 | 34,123 | 416.858 | 33,295 | 34,951 |

| 30/7/2020 | 1,576,790 | 4686.95 | 1,567,480 | 1,586,100 | 34,879 | 418.306 | 34,048 | 35,709 |

| 31/8/2020 | 1,630,920 | 4711.18 | 1,621,560 | 1,640,270 | 35,646 | 420.468 | 34,811 | 36,481 |

| 1/8/2020 | 1,686,780 | 4745.67 | 1,677,350 | 1,696,200 | 36,426 | 423.546 | 35,585 | 37,267 |

| 2/8/2020 | 1,744,420 | 4,793 | 1,734,900 | 1,753,940 | 37,219 | 427.771 | 36,369 | 38,068 |

| 3/8/2020 | 1,803,890 | 4856.06 | 1,794,250 | 1,813,540 | 38,024 | 433.399 | 37,163 | 38,885 |

| 4/8/2020 | 1,865,240 | 4938.01 | 1,855,430 | 1,875,050 | 38,843 | 440.713 | 37,967 | 39,718 |

| 5/8/2020 | 1,928,510 | 5042.2 | 1,918,490 | 1,938,520 | 39,675 | 450.012 | 38,781 | 40,568 |

| 6/8/2020 | 1,993,740 | 5172.11 | 1,983,470 | 2,004,020 | 40,520 | 461.606 | 39,603 | 41,437 |

| 7/8/2020 | 2,061,000 | 5331.23 | 2,050,410 | 2,071,580 | 41,380 | 475.807 | 40,435 | 42,325 |

| 8/8/2020 | 2,130,320 | 5522.95 | 2,119,350 | 2,141,290 | 42,253 | 492.918 | 41,274 | 43,232 |

| 9/8/2020 | 2,201,750 | 5750.49 | 2,190,330 | 2,213,180 | 43,142 | 513.226 | 42,122 | 44,161 |

| 10/8/2020 | 2,275,360 | 6016.81 | 2,263,410 | 2,287,310 | 44,045 | 536.995 | 42,978 | 45,111 |

| 11/8/2020 | 2,351,180 | 6324.55 | 2,338,620 | 2,363,740 | 44,963 | 564.46 | 43,841 | 46,084 |

| 12/8/2020 | 2,429,270 | 6,676 | 2,416,020 | 2,442,530 | 45,896 | 595.827 | 44,713 | 47,079 |

| 13/8/2020 | 2,509,690 | 7073.14 | 2,495,640 | 2,523,740 | 46,845 | 631.271 | 45,591 | 48,099 |

| 14/8/2020 | 2,592,480 | 7517.67 | 2,577,550 | 2,607,410 | 47,810 | 670.946 | 46,478 | 49,143 |

| 15/8/2020 | 2,677,700 | 8011.05 | 2,661,790 | 2,693,610 | 48,792 | 714.979 | 47,372 | 50,212 |

| 16/8/2020 | 2,765,410 | 8554.53 | 2,748,420 | 2,782,400 | 49,790 | 763.485 | 48,273 | 51,306 |

| 17/8/2020 | 2,855,650 | 9149.27 | 2,837,480 | 2,873,820 | 50,805 | 816.565 | 49,183 | 52,426 |

| 18/8/2020 | 2,948,490 | 9796.34 | 2,929,040 | 2,967,950 | 51,837 | 874.314 | 50,100 | 53,573 |

| 19/8/2020 | 3,043,980 | 10496.7 | 3,023,130 | 3,064,830 | 52,887 | 936.825 | 51,026 | 54,748 |

| 20/8/2020 | 3,142,180 | 11251.5 | 3,119,830 | 3,164,530 | 53,955 | 1004.19 | 51,960 | 55,949 |

| 21/8/2020 | 3,243,150 | 12061.8 | 3,219,190 | 3,267,100 | 55,041 | 1076.5 | 52,903 | 57,179 |

| 22/8/2020 | 3,346,930 | 12928.5 | 3,321,260 | 3,372,610 | 56,146 | 1153.86 | 53,855 | 58,438 |

| 23/8/2020 | 3,453,610 | 13852.9 | 3,426,090 | 3,481,120 | 57,270 | 1236.36 | 54,815 | 59,726 |

| 24/8/2020 | 3,563,220 | 14836.2 | 3,533,750 | 3,592,690 | 58,414 | 1324.12 | 55,784 | 61,044 |

| 25/8/2020 | 3,675,840 | 15879.7 | 3,644,300 | 3,707,380 | 59,577 | 1417.25 | 56,763 | 62,392 |

| 26/8/2020 | 3,791,520 | 16984.6 | 3,757,790 | 3,825,250 | 60,761 | 1515.86 | 57,750 | 63,772 |

| 27/8/2020 | 3,910,330 | 18152.5 | 3,874,280 | 3,946,380 | 61,965 | 1620.09 | 58,747 | 65,183 |

| 28/8/2020 | 4,032,330 | 19384.6 | 3,993,830 | 4,070,830 | 63,190 | 1730.06 | 59,754 | 66,626 |

| 29/8/2020 | 4,157,570 | 20682.7 | 4,116,500 | 4,198,650 | 64,437 | 1845.91 | 60,771 | 68,103 |

| 30/8/2020 | 4,286,140 | 22048.1 | 4,242,350 | 4,329,930 | 65,705 | 1967.78 | 61,797 | 69,613 |

| 31/8/2020 | 4,418,080 | 23482.7 | 4,371,440 | 4,464,720 | 66,996 | 2095.81 | 62,833 | 71,158 |

| 1/9/2020 | 4,553,460 | 24988.1 | 4,503,840 | 4,603,090 | 68,309 | 2230.17 | 63,879 | 72,738 |

| 2/9/2020 | 4,692,360 | 26,566 | 4,639,600 | 4,745,120 | 69,645 | 2370.99 | 64,936 | 74,354 |

| 3/9/2020 | 4,834,830 | 28218.2 | 4,778,780 | 4,890,870 | 71,004 | 2518.45 | 66,002 | 76,006 |

| 4/9/2020 | 4,980,940 | 29946.6 | 4,921,460 | 5,040,420 | 72,388 | 2672.7 | 67,080 | 77,696 |

| 5/9/2020 | 5,130,760 | 31,753 | 5,067,700 | 5,193,830 | 73,796 | 2833.92 | 68,167 | 79,424 |

| 96/9/2020 | 5,284,360 | 33639.3 | 5,217,550 | 5,351,170 | 75,228 | 3002.28 | 69,265 | 81,191 |

| 7/9/2020 | 5,441,810 | 35607.6 | 5,371,090 | 5,512,530 | 76,686 | 3177.94 | 70,374 | 82,997 |

| 8/9/2020 | 5,603,170 | 37659.8 | 5,528,380 | 5,677,970 | 78,169 | 3361.1 | 71,494 | 84,845 |

| 9/9/2020 | 5,768,520 | 39797.9 | 5,689,480 | 5,847,570 | 79,679 | 3551.93 | 72,624 | 86,733 |

| 10/9/2020 | 5,937,930 | 42024.1 | 5,854,470 | 6,021,400 | 81,215 | 3750.62 | 73,766 | 88,664 |

| 11/9/2020 | 6,111,470 | 44340.5 | 6,023,400 | 6,199,530 | 82,778 | 3957.35 | 74,918 | 90,637 |

| 12/9/2020 | 6,289,210 | 46749.1 | 6,196,360 | 6,382,050 | 84,369 | 4172.32 | 76,082 | 92,655 |

| 13/9/2020 | 6,471,220 | 49252.2 | 6,373,400 | 6,569,030 | 85,987 | 4395.72 | 77,257 | 94,717 |

| 14/9/2020 | 6,657,570 | 51,852 | 6,554,590 | 6,760,560 | 87,634 | 4627.75 | 78,443 | 96,825 |

| 15/9/2020 | 6,848,350 | 54550.8 | 6,740,010 | 6,956,690 | 89,311 | 4868.61 | 79,641 | 98,980 |

| 16/9/2020 | 7,043,630 | 57350.8 | 6,929,720 | 7,157,530 | 91,016 | 5118.5 | 80,850 | 101,182 |

| 17/9/2020 | 7,243,470 | 60254.3 | 7,123,800 | 7,363,140 | 92,752 | 5377.64 | 82,071 | 103,432 |

| 18/9/2020 | 7,447,960 | 63263.6 | 7,322,320 | 7,573,610 | 94,518 | 5646.22 | 83,304 | 105,732 |

| 9/19/2020 | 7,657,180 | 66381.2 | 7,525,340 | 7,789,020 | 96,315 | 5924.46 | 84,549 | 108,082 |

| 20/9/2020 | 7,871,190 | 69609.4 | 7,732,940 | 8,009,440 | 98,144 | 6212.57 | 85,805 | 110,483 |

| 21/9/2020 | 8,090,090 | 72950.6 | 7,945,200 | 8,234,980 | 100,005 | 6510.78 | 87,074 | 112,936 |

| 22/9/2020 | 8,313,940 | 76407.4 | 8,162,190 | 8,465,700 | 101,898 | 6819.29 | 88,354 | 115,442 |

| 23/9/2020 | 8,542,830 | 79982.2 | 8,383,980 | 8,701,690 | 103,824 | 7138.34 | 89,647 | 118,002 |

| 24/9/2020 | 8,776,840 | 83677.5 | 8,610,650 | 8,943,030 | 105,785 | 7468.14 | 90,952 | 120,617 |

| 25/9/2020 | 9,016,040 | 87495.8 | 8,842,270 | 9,189,820 | 107,779 | 7808.92 | 92,270 | 123,288 |

| 26/9/2020 | 9,260,530 | 91439.8 | 9,078,920 | 9,442,140 | 109,808 | 8160.92 | 93,600 | 126,016 |

| 27/9/2020 | 9,510,370 | 95,512 | 9,320,680 | 9,700,070 | 111,873 | 8524.36 | 94,943 | 128,803 |

| 28/9/2020 | 9,765,660 | 99715.1 | 9,567,620 | 9,963,700 | 113,973 | 8899.48 | 96,298 | 131,648 |

| 29/9/2020 | 10,026,500 | 104,052 | 9,819,820 | 10,233,100 | 116,110 | 9286.52 | 97,666 | 134,554 |

| 30/9/2020 | 10,292,900 | 108,524 | 10,077,400 | 10,508,400 | 118,284 | 9685.71 | 99,047 | 137,520 |

| 1/10/2020 | 10,565,000 | 113,136 | 10,340,300 | 10,789,700 | 120,495 | 10097.3 | 100,441 | 140,549 |

| 2/10/2020 | 10,842,900 | 117,890 | 10,608,800 | 11,077,000 | 122,745 | 10521.5 | 101,848 | 143,642 |

| 3/10/2020 | 11,126,700 | 122,787 | 10,882,800 | 11,370,500 | 125,034 | 10958.7 | 103,269 | 146,799 |

| 4/10/2020 | 11,416,400 | 127,832 | 11,162,500 | 11,670,300 | 127,362 | 11408.9 | 104,703 | 150,021 |

| 5/10/2020 | 11,712,100 | 133,027 | 11,447,900 | 11,976,300 | 129,730 | 11872.6 | 106,150 | 153,310 |

| 6/10/2020 | 12,014,000 | 138,375 | 11,739,200 | 12,288,800 | 132,138 | 12349.9 | 107,610 | 156,666 |

| 7/102020 | 12,322,100 | 143,879 | 12,036,400 | 12,607,900 | 134,588 | 12,841 | 109,085 | 160,092 |

| 8/10/2020 | 12,636,500 | 149,541 | 12,339,500 | 12,933,500 | 137,080 | 13346.4 | 110,573 | 163,587 |

| 9/10/2020 | 12,957,300 | 155,365 | 12,648,800 | 13,265,900 | 139,614 | 13866.2 | 112,075 | 167,154 |

| 10/10/2020 | 13,284,600 | 161,353 | 12,964,100 | 13,605,100 | 142,191 | 14400.6 | 113,591 | 170,792 |

| 11/10/2020 | 13,618,500 | 167,509 | 13,285,800 | 13,951,100 | 144,813 | 14,950 | 115,121 | 174,505 |

| 12/10/2020 | 13,959,000 | 173,835 | 13,613,700 | 14,304,200 | 147,478 | 15514.7 | 116,665 | 178,292 |

| 13/10/2020 | 14,306,300 | 180,335 | 13,948,100 | 14,664,400 | 150,189 | 16094.8 | 118,223 | 182,154 |

| 14/10/2020 | 14,660,400 | 187,012 | 14,289,000 | 15,031,800 | 152,945 | 16690.7 | 119,796 | 186,094 |

FIGURE A1.

Spatial autocorrelation as of 21 March, 2020

FIGURE A2.

Spatial autocorrelation as of 21 April, 2020

FIGURE A3.

Spatial autocorrelation as of 21 May, 2020

FIGURE A4.

Spatial autocorrelation as of 20 June, 2020

FIGURE A5.

Nearest neighbor analysis as of 21 March, 2020

FIGURE A6.

Nearest neighbor analysis as of 21 April, 2020

FIGURE A7.

Nearest neighbor analysis as of 31 May, 2020

FIGURE A8.

Nearest neighbour analysis as of 20 June, 2020

Bag R, Ghosh M, Biswas B, Chatterjee M. Understanding the spatio‐temporal pattern of COVID‐19 outbreak in India using GIS and India's response in managing the pandemic. Reg Sci Policy Pract. 2020;12:1063–1103. 10.1111/rsp3.12359

Footnotes

GWR is non‐stationary spatial regression method widely used in spatial epidemiology.

Holi is a popular festival of colours widely celebrated in India.

In India, rural to urban migration is common phenomena because of two broad reasons, such as growing urbanization pulling an aspirant rural young population for better economic opportunities, on the other hand regional agrarian crisis pushes the distressed rural population to work in unhygienic urban slums as daily wage labourers. However, the present coronavirus pandemic in India has caused a substantial reverse migration from cities to the rural hinterland. In the first wave of the coronavirus pandemic in India, cities became the major hotspots, at the same time government has imposed a nationwide lockdown. Within a few days, a major portion of workers started migrating to rural areas due to a livelihood crisis in the cities. They lost their daily wage labouring jobs and were unable to fulfil the daily livelihood requirements.

The Indian state of Kerala has treated this pandemic differently within the country. Kerala was inventing low cost COVID‐19 Sample collection technique which also gathers samples without direct contact or exposure. The extensive field survey has been conducted for sample collection. Kerala has also dealt the public distribution systems effectively for poor people both in rural and urban areas.

Agriculture is the largest employer, at 42 percent of the workforce, but produces just 18 percent of GDP. Over 86 percent of all agricultural holdings have inefficient scale (below 2 hectares).

REFERENCES

- Abd Majid, N. , Muhamad Nazi, N. , & Mohamed, A. F. (2019). Distribution and spatial pattern analysis on dengue cases in Seremban District, Negeri Sembilan, Malaysia. Sustainability, 11(13), 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Adnan, M. , Khan, S. , Kazmi, A. , Bashir, N. , & Siddique, R. (2020). COVID‐19 infection: Origin, transmission, and characteristics of human coronaviruses. Journal of Advanced Research, 24, 91–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akhtar, M. , Kraemer, M. U. G. , & Gardner, L. M. (2019). A dynamic neural network model for predicting the risk of Zika in real‐time. BMC Medicine, 17(171), 1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arti, M. K. (2020). Modeling and Predictions for COVID 19 Spread in India. 10.13140/RG.2.2.11427.81444 [DOI]

- Bedford, J. , Enria, D. , Giesecke, J. , Heymann, D. L. , Ihekweazu, C. , Kobinger, G. , … Ungchusak, K. (2020). COVID‐19: Towards controlling of a pandemic. The Lancet, 395(10229), 1015–1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brockmann, D. , David, V. , & Gallardo, A. M. (2009). Human mobility and spatial disease dynamics. Diffusion fundamentals, 11(2), 1–27. http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:bsz:15-qucosa-188611 [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y. (2013). New approaches for calculating Moran’s index of spatial autocorrelation. PLoS ONE, 8(7), e68336. 10.1371/journal.pone.0068336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowell, G. , & Rothenberg, R. (2018). Spatial infectious disease epidemiology: On the cusp. BMC Medicine, 16(192), 1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clara‐Rahola, J. (2020). An empirical model for the spread and reduction of the CoVid19 pandemic. Studies of Applied Economics, 38(2), 1–11. 10.25115/eea.v38i2.3323 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ebdon, D. (1985). Statistics in geography. United Kingdom: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, S. , Dinda, S. , Chatterjee, N. D. , Das, K. , & Mahata, R. (2019). The spatial clustering of dengue disease and risk susceptibility mapping: an approach towards sustainable health management in Kharagpur city, India. Spatial Information Research, 27(2), 187–204. [Google Scholar]

- Haining, R. (2012). GIS and public health, by E.K. Cromley and S.L. McLafferty, New York, Guilford Press, 2012, 2nd ed., ISBN‐10 1609187504, ISBN‐13 978‐1609187507. International Journal of Geographical Information Science, 27(5), 1040–1041. 10.1080/13658816.2012.717629 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hebbar, N. (2020). COVID‐19: PM calls for social distancing, people's curfew. The Hindu, March 20, 1. https://www.magzter.com/article/Newspaper/The-Hindu/COVID-19-PM-Calls-For-Social-Distancing-Peoples-Curfew [Google Scholar]

- Kaur, T. , Sarkar, S. , Chowdhury, S. , Sinha, S. K. , Jolly, M. K. , & Dutta, P. S. (2020). Anticipating the novel coronavirus disease (COVID‐19) pandemic. Frontiers in Public Health, 8. 10.3389/fpubh.2020.569669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koubaa, A. (2020). Understanding the covid19 outbreak: A comparative data analytics and study. arXiv preprint arXiv:2003.14150. https://arxiv.org/abs/2003.14150

- Lessler, J. , Salje, H. , Grabowski, M. K. , & Cummings, D. A. T. (2016). Measuring spatial dependence for infectious disease epidemiology. PLoS ONE, 11(5), 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, R. , Pei, S. , Chen, B. , Song, Y. , Zhang, T. , Yang, W. , & Shaman, J. (2020). Substantial undocumented infection facilitates the rapid dissemination of novel coronavirus (SARS‐CoV2). Science, 368, 489–493. 10.1126/science.abb3221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mondal, S. , & Ghosh, S. (2020). Fear of exponential growth in Covid19 data of India and future sketching, (April). 10.13140/RG.2.2.28834.17607 [DOI]

- Nadeem, S. (2020). Coronavirus COVID‐19: Available free literature provided by various companies, journals and organizations around the world. Journal of Ongoing Chemical Research, 5(1), 7–13. [Google Scholar]

- Nandy, D. (2020). COVID‐19 rural crisis: Why MGNREGA needs a harder push. New Delhi: Down to Earth. https://www.downtoearth.org.in/blog/covid-19-rural-crisis-why-mgnrega-needs-a-harder-push-72130 [Google Scholar]

- Pandey, G. , Chaudhary, P. , Gupta, R. , & Pal, S. (2020). SEIR and regression model‐based COVID‐19 outbreak predictions in India. arXiv preprint arXiv:2004.00958. https://arxiv.org/abs/2004.00958v1

- Perappadan, B. S. (2020). COVID‐19 | Italian tourist in Jaipur tests positive. The Hindu, March 4, 1. https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/other-states/italian-tourist-in-jaipur-tests-positive-for-covid-19/article30967526.ece [Google Scholar]

- Ranjan, R. (2020). Estimating the Final Epidemic Size for COVID‐19 Outbreak using Improved Epidemiological Models. medRxiv. 10.1101/2020.04.12.20061002 [DOI]

- Rasam, A. R. A. , Ghazali, R. , Noor, A. M. M. , Mohd, W. M. N. W. , Hamid, J. R. A. , Bazlan, M. J. , & Ahmad, N. (2014). Spatial epidemiological techniques in cholera mapping and analysis towards a local scale predictive modelling. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science (Vol. 18, No. 1, p. 012095). IOP Publishing. 10.1088/1755-1315/18/1/012095 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ruktanonchai, C. W. , Pindolia, D. K. , Striley, C. W. , Odedina, F. T. , & Cottler, L. B. (2014). Utilizing spatial statistics to identify cancer hot spots: a surveillance strategy to inform community‐engaged outreach efforts. International Journal of Health Geographics, 13(39), 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stresman, G. H. , Mwesigwa, J. , Achan, J. , Giorgi, E. , Worwui, A. , Jawara, M. , & Alessandro, U. D. (2018). Do hotspots fuel malaria transmission: a village‐scale spatio‐temporal analysis of a 2‐year cohort study in The Gambia. BMC, 16(160), 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]