Abstract

Objectives:

This study investigated whether an intervention designed to reduce homeostatic sleep pressure would improve night shift performance and alertness in older adults.

Methods:

Non-shift workers aged 57.9±4.6 (mean±SD) worked 4 Day (07:00–15:00) and 4 Night shifts (23:00–07:00). Two intervention groups were instructed to remain awake until ~13:00h after each night shift: the sleep-timing group (ST; n=9) was instructed to spend 8h in bed attempting sleep; the sleep-ad lib group (SA; n=9) was given no further sleep instructions. A Control group (n=9) from our previous study was not given any sleep instructions. Performance and subjective sleepiness were assessed hourly using psychomotor vigilance task testing and Karolinska Sleepiness Scales.

Results:

The ST group maintained their day shift sleep durations on night shifts, whereas the Control group slept less. The ST group were able to maintain stable performance and alertness across the initial part of the night shift, while the Control group’s alertness and performance declined across the entire night. Wake duration before a night shift negatively impacted sustained attention and self-reported sleepiness but not reaction time, whereas sleep duration before a night shift affected reaction time and ability to sustain attention but not self-reported sleepiness.

Conclusions:

A behavioural change under the control of the individual worker, spending 8h in bed and waking close to the start of the night shift, allowed participants to acquire more sleep and improved performance on the night shift in older adults. Both sleep duration and timing are important factors for night shift performance and self-reported sleepiness.

Keywords: aging, shiftwork, sleep, circadian rhythms, PVT

INTRODUCTION

Working overnight requires attempting to sleep during the day when the circadian rhythm of sleep-wake propensity is promoting wakefulness1, contributing to shorter sleep durations in shift workers than day workers2. Insufficient sleep impairs cognitive performance3,4, which worsens during the biological night4,5, and leads to more accidents on-shift6 and when commuting7. Furthermore, night workers may attempt to perform tasks they are too tired to do safely because rating one’s own sleepiness is less reliable at night8,9. Older age10 is associated with less deep sleep and more frequent awakenings when sleeping at night11, and even greater fragmentation of sleep when sleeping during the day12. These age-related changes in the ability to maintain sleep during the day increase vulnerability to sleep-related impairments in older shift workers13. The 2004 Current Population Survey reported that nearly 9% of the 17.5 million U.S. workers age 55 and older were working night, split, irregular, or rotating shifts, amounting to more than 1.5 million individuals. Furthermore, adults over age 55 make up 22% of the U.S. workforce, a figure that is predicted to rise to 24.8% by 2026; almost one in four American workers14. Thus, interventions that are tailored to improving sleep and performance should be tested in older shift workers.

Sleeping in the morning just after finishing overnight work results in a long wake duration (WD) and increases the pressure for sleep on the subsequent night shift. Countermeasures to address the sleep and sleepiness problems of shift workers typically aim to address one, or both, of the two major sleep-wake regulatory processes, the sleep-wake homeostat and the circadian timing system. The typical approach is to: (i) acutely increase daytime sleep duration; (ii) acutely increase night-time (on-shift) alertness; (iii) shift biological clock timing to indirectly increase night-time alertness and daytime sleep. We recently reported that utilising both sleep-wake homeostatic and circadian approaches, by moving wake time closer to the start of the night shift and enhancing light in the latter half of the night shift, preserved night shift attention and vigilance to day shift levels in both younger15 and older adults16. While that strategy was successful, we recognize that obtaining bright light for several hours during a night shift may be impractical for many workers. We therefore carried out the current study to test whether a sleep timing intervention alone (without changing the lighting during work) would improve performance and alertness on the night shift in older adults. Our experimental group (called ST, for sleep timing) had a scheduled 8-h sleep opportunity that ended 1–2 hours before the subsequent overnight shift (similar to typical day workers), and was compared to the Control group from our previous study16. To examine whether just moving sleep closer to the next night shift would improve on-shift alertness and performance, we included a second experimental group who were instructed stay awake until 13:00 but were not given any further sleep or time-in-bed instructions (called SA, for sleep ad lib).

METHODS

Participants

Data from the nine participants in the Control group were collected in 2013–2015 and have been reported previously16. Two new experimental groups were studied between 2015 and 2018 and are compared to that Control group. All participants were part of the same large study, had the same screening criteria, pre-study monitoring, experimental conditions (except for sleep timing between night shifts) and were enrolled in the study throughout the calendar year (except August and December each year). There were 6 men and 3 women in each group, aged 57.9±4.6 years (mean±SD). An ANOVA showed that there were no significant differences in age (F2,26=1.02, p=0.4) or chronotype (F2,26=1.43, p=0.3) between the groups.

The protocol was approved by the Partners Health Care Institutional Review Board and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants gave written informed consent and were compensated for their participation.

Pre-study conditions

Participants were instructed to spend ~8h in bed each night for one week before the study, avoiding naps, caffeine, alcohol, and changes in medications. Compliance with the sleep schedule was verified via a wrist activity-light monitor.

Study protocol

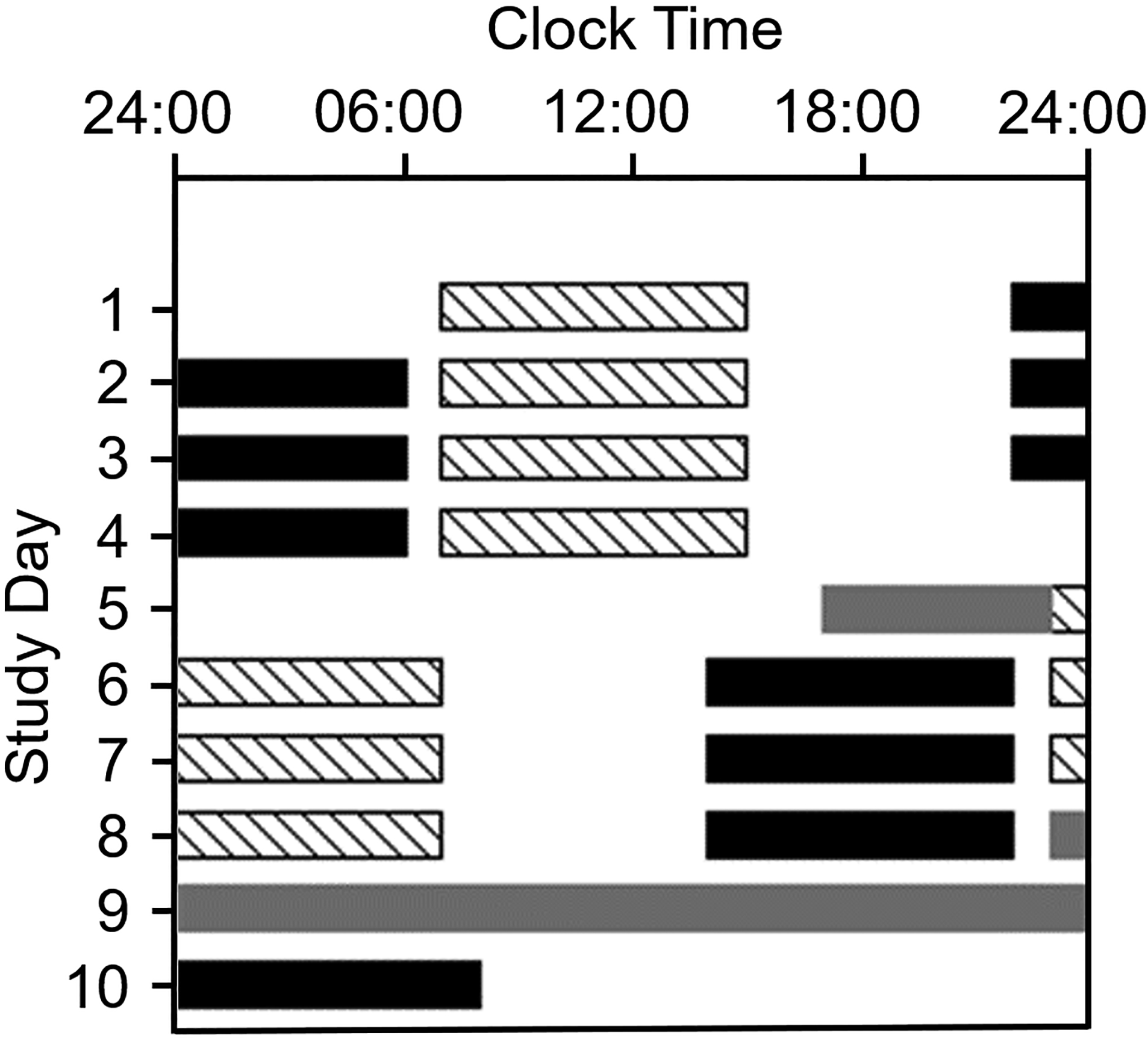

The 10-day laboratory protocol comprised four consecutive day shifts (7:00–15:00), a day off, and four consecutive night shifts (23:00–07:00; Figure 1). Participants were studied separately in light-controlled research suites (~90 lux from 4100K ceiling-mounted fluorescent lamps) in the Center for Clinical Investigation at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Hourly computerized neurobehavioral test batteries, ~45 minutes each hour, were monitored by study staff inside the suite. Test batteries were separated by 5-minute or 10-minute breaks, and the participants ate an ad lib lunch during the 30-minute meal break (11:00 or 03:00). Participants left the laboratory after each shift. Circadian phase assessments were performed before the first Night shift (Day 5) and during/following the final Night shift (Days 8–9; Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Raster plot of the 10-day simulated shift work protocol. Clock hour is shown across the x-axis and study day is shown on the y-axis. Consecutive study days are shown beneath the previous study day. Diagonal bars indicate work shifts in the laboratory under typical room lighting (~90 lux). Four Day shifts, from 07:00 to 15:00 were followed by a day off and four Night shifts, from 23:00 to 07:00. Grey bars indicate dim-light (~4 lux) circadian phase estimation procedures in the laboratory, when hourly saliva samples were collected. Participants were outside the laboratory at all other times. Black bars indicate scheduled sleep episodes at home, and scheduled sleep in the laboratory on Day 10. Participants were randomized to one of three sleep conditions on Days 6–8: the ST group depicted here had scheduled 8-h time in bed beginning between 13:00–14:00. Not shown: SA group: ad-lib sleep after 13:00; Control group: no instructions about the timing or duration of sleep following Night shifts 1–3.

Participants kept a self-selected ~8-h sleep schedule between day shifts and slept ad lib after the last day shift. After the first night shift, participants were randomized to one of the at-home sleep schedules; the sleep timing group (ST) was instructed to remain out of bed until 13:00–14:00, then go to bed and remain there, attempting to sleep for 8h. The sleep ad lib group (SA) was instructed not to go to bed before 13:00 but were not given further instructions. The Control group was not given any sleep instructions.

Sleep assessment

Bed and wake times were recorded in a diary and documented by a call to a timed-stamped voicemail. A motion and light sensing device, worn on the non-dominant wrist throughout the study, recorded sleep-wakefulness (analysed using MotionWare [version 1.1.20, CamNTech Ltd., Cambridge, UK]) at the high-sensitivity setting in 60-sec epochs, with manual editing of sleep episodes. Outcomes were time in bed (TIB) and sleep duration (SD). The Pre-study sleep was calculated by averaging the 7 nights immediately before the study. Day shift (DS) sleep was calculated by averaging the nights before DS3 and DS4. Night shift (NS) sleep was calculated before each work shift. NS1 was omitted because all participants slept ad lib. When Control or SA participants slept in more than one bout between night shifts (Control n=5, SA n=3) the TIB and SD of all bouts on that day were combined. Wake duration (WD) was calculated from the final wake-time to the time a test was performed.

Neurobehavioral tests

Subjective sleepiness was rated using the Karolinska Sleepiness Scale (KSS)17 every hour immediately before the PVT.

Hourly 10-minute visual PVT assessed sustained attention18. Participants pressed a button with their dominant thumb in response to a stimulus on the computer screen. Average reaction time (RT; ~90–100 per PVT) was recorded in msec. Lapses of attention were defined as RT>500ms.

Circadian phase assessment

Hourly saliva samples were collected in dim light [~4 lux] before NS1 (17:00–23:00) and throughout and after NS4 (Day 8–9, 23:00–24:00), and frozen and sent to Solidphase, Inc. (Portland, ME, USA) for assay via direct saliva melatonin radioimmunoassay (Bühlmann Diagnostics Corp., Amherst NH, USA). Dim-light melatonin onset (DLMO) was calculated as the clock time that melatonin levels crossed a 3.0 pg/mL threshold, using linear interpolation between adjacent samples19. A 1.0 pg/mL threshold was used for participants (ST n=2, Control n=2) whose melatonin levels did not reach 3.0 pg/mL. Phase shift was calculated as the difference in clock time of DLMO before NS1 and after NS4.

Data analysis

DS data comprised the average of DS3 and DS4. For all analyses, PVT mean RTs were converted to 1/mean RT to better approximate a normal distribution but are presented in the Figures as RT. Data were analysed using linear mixed models with planned post-hoc Bonferroni corrections. PVT lapses were analysed using general linear mixed models with a Poisson distribution. TIB and SD comparisons were performed with main and interaction effects, for factors group (ST, SA, Control) and shift (DS, NS2, NS3, NS4) with participant as a random effect.

Whole shift analyses were performed with planned post hoc comparisons for main and interaction effects, for factors group (ST, SA, Control), shift (DS, NS2, NS3, NS4), WD, and SD with participant as a random effect. Within NS comparisons (to identify the most vulnerable time of the night) were performed with planned post hoc comparisons for main and interaction effects, for factors group (ST, SA, Control), session (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8), WD, and SD with participant as a random effect.

Changes in circadian phase before and after the Night shift were assessed using ANOVA. The relationship between baseline DLMO and the magnitude of the phase shift was examined using a Pearson correlation coefficient.

Data are presented as mean±SEM unless otherwise stated. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA).

RESULTS

Time in bed and sleep duration

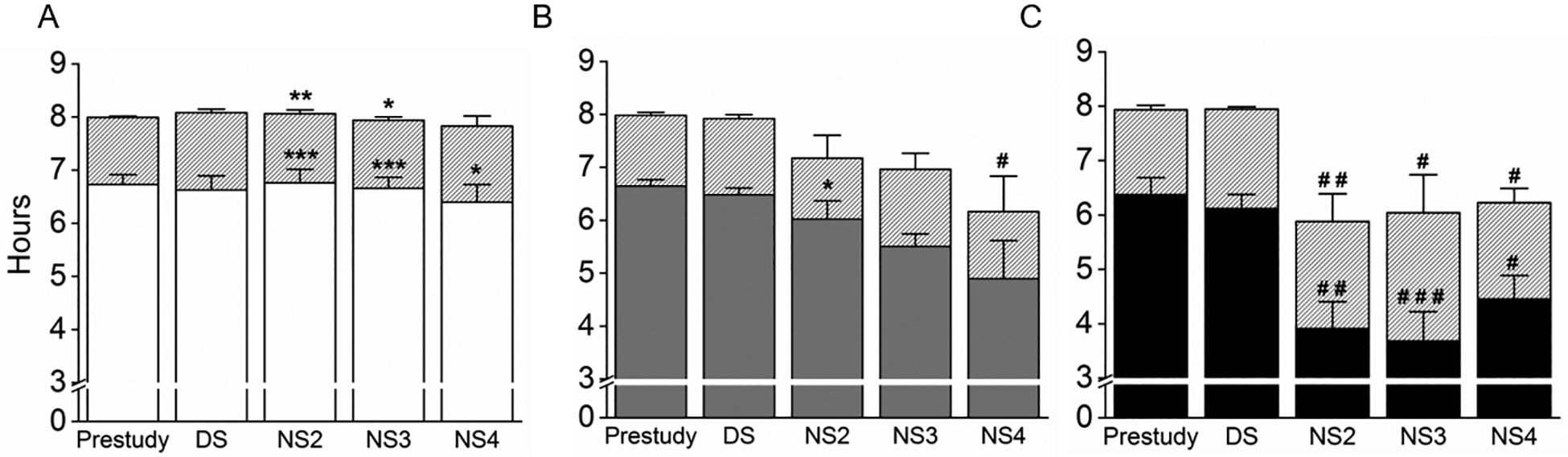

Pre-study and DS TIB and SD were similar between the ST, SA, and Control groups. TIB displayed significant effects of group (F2,89=12.82; p=0.0001), shift (F4,89=10.97; p<0.0001) and group*shift interaction (F8,89=3.31; p=0.002). The ST group maintained their DS TIB on the NS, in contrast with SA participants who spent less TIB before each successive NS, resulting in NS4 being significantly shorter than on the DS (p=0.02; Figure 2). The ST group spent on average 1.5h longer in bed than the Control group on NS (Figure 2), whereas TIB was similar between the SA and Control groups (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Average (±SEM) time in bed (TIB) and sleep duration (SD), assessed via wrist actigraphy. The grey bars represent TIB in each of the groups. Below the grey bars, SD is represented in the: (A) ST group as white bars; (B) SA group as grey bars and (C) Control group as black bars. Pre-study TIB and SD comprised the mean of the 7 nights before the laboratory study; Day shift (DS) TIB and SD were calculated as the mean TIB and SD before Day shifts 3 and 4; the night shift (NS) represents TIB and SD before the work shift. Significant difference between the study groups and Control group on the same sleep episode: * = p<0.05, ** = p<0.01 and *** = p<0.001. Significant difference from DS: # = p<0.05, ## = p<0.01 and ### = p<0.001.

SD also displayed significant overall effects of group (F2,89=14.64; p=0.0001), shift (F4,89=13.45; p<0.0001) and group*shift interaction (F8,89=5.0; p=0.0001). SD was similar between NS and DS in the ST group (Figure 2A). In contrast, the Control group slept significantly less before every NS than before the DS (p<0.05; Figure 2C) moreover, sleeping approximately 2h a day less than the ST group. The SA group slept less on the NS than the ST group (p=0.04), but longer than the Control group (p=0.02).

Subjective sleepiness; KSS

KSS displayed significant overall effects of shift (F3,828=40.27; p<0.0001) and shift*group (F6,828=3.90; p=0.0008) interaction, but no overall effect of group (F2,828=0.38; p=0.68). The ST group reported feeling sleepier on NS2 and NS3, the SA group felt sleepier on NS2 and NS4, and the Control group felt sleepier on every NS than they did on the DS.

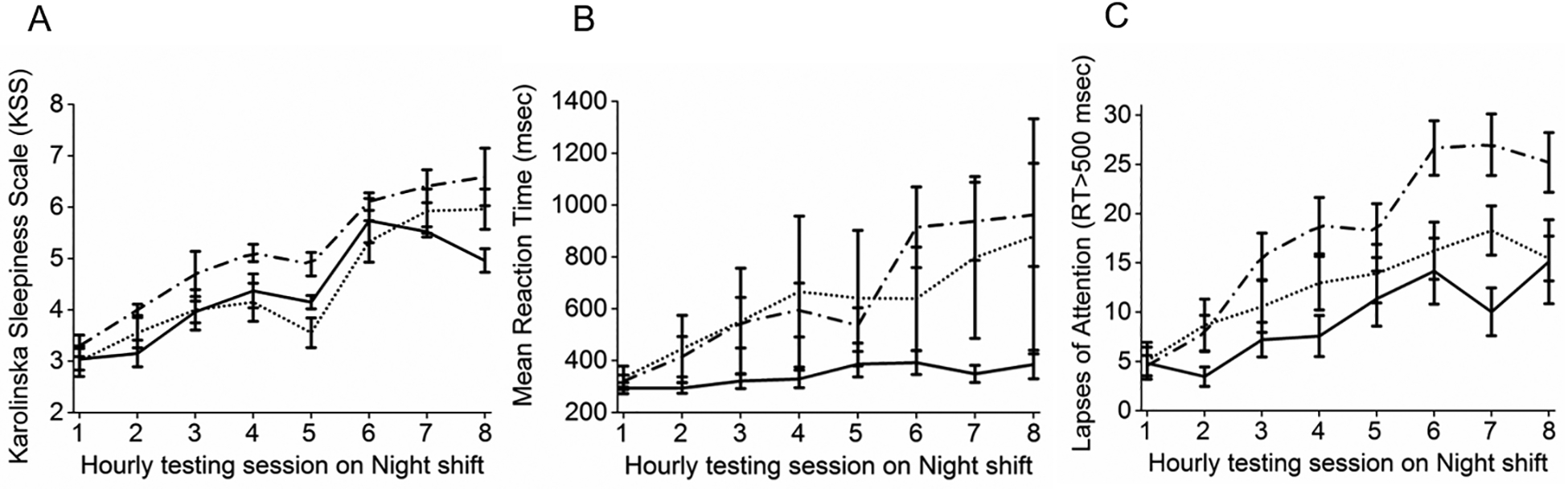

When sessions 2–8 of the average NS were compared to session 1, there was a significant overall effect of session (F7,583=16.93; p<0.0001) and WD (F1,583=5.58; p=0.02), but no overall effect of SD (F1,559=1.76; p=0.18), group (F2,583=0.11; p=0.90), or group*session interaction (F14,583=1.49; p=0.11). The ST group reported feeling sleepier during sessions 6 and 7 (p<0.0001), but not during session 8 (p=0.35), the SA group was significantly sleepier on sessions 6–8 (p<0.005), while the Control group reported feeling significantly sleepier during sessions 4–8 than during session 1 (p<0.04; Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

A. Subjective sleepiness (Karolinska Sleepiness Scale); B. PVT mean reaction time (RT); C. PVT lapses of attention (RT>500msec). Solid lines represent the ST group, dotted lines represent the SA group, and dashed lines represent the Control group. Each hourly test is shown on the x axis. Data presented are mean±SEM of Night shifts 2, 3, and 4.

PVT reaction time (RT) and lapses of attention

PVT data from one participant in the ST group was excluded when post hoc examination revealed they had not followed the instructions. RT displayed significant overall effects of shift (F3,718=59.25; p<0.0001), WD (F1,742=103.07; p<0.0001), SD (F1,718=25.11; p<0.0001), and group*shift interaction (F6,718=2.99; p=0.007), but no main effect of group (F1,718=1.14; p=0.32). The DS RT was similar between the groups (p=1). Compared to that on the DS, RT in the ST group was slower on NS4 (p=0.003). In contrast, the Control group was significantly slower on all three NS compared to the DS (p<0.0001; Figure 3B).

Comparing each hourly PVT session on the NS, there were significant overall effects of session (F7,506=47.4; p<0.0001), SD (F1,506=29.88 p<0.0001), and group*session interaction (F14,506=2.07; p=0.01) but no significant effect of WD (F1,506=0.54 p=0.46) or group (F2,506=0.63; p=0.53). Average RT slowed as the NS progressed (Figure 3B), however this impaired performance occurred later in the ST group; sessions 6–8 of the NS were slower than session 1 (p<0.01). Whereas sessions 2–8 were slower than session 1 in the Control group (p<0.0001).

Lapses of attention displayed a significant overall effect of group (F2,781=91.66; p<0.0001), shift (F3,781=90.12; p<0.0001), WD (F1,781=598.2; p<0.0001), and SD (F1,781=1157; p<0.0001), but no group*shift interaction (F6,781=22.01; p=0.11). Post hoc comparisons showed that lapses were significantly greater on NS compared to DS in all three groups (p<0.05) There were significantly more lapses in the SA group than in the ST group (p<0.001) on each NS (Figure 3C), but not between the SA and the Control groups.

Comparing each session on the NS, there was an overall effect of group (F2,527=25.6; p<0.0001), session (F7,527=71.88; p<0.0001), WD (F1,527=37.92; p<0.0001), SD (F1,527=1166; p<0.0001), and group*session interaction (F14,527=6.59; p<0.0001). The ST group had significantly more lapses in sessions 5–8 than in session 1 (p<0.0006), whereas the Control group had more lapses in all sessions than in session 1 (p<0.0001; Figure 3C). The Control group also had more lapses than the ST group in all sessions apart from session 1 (p<0.0001)

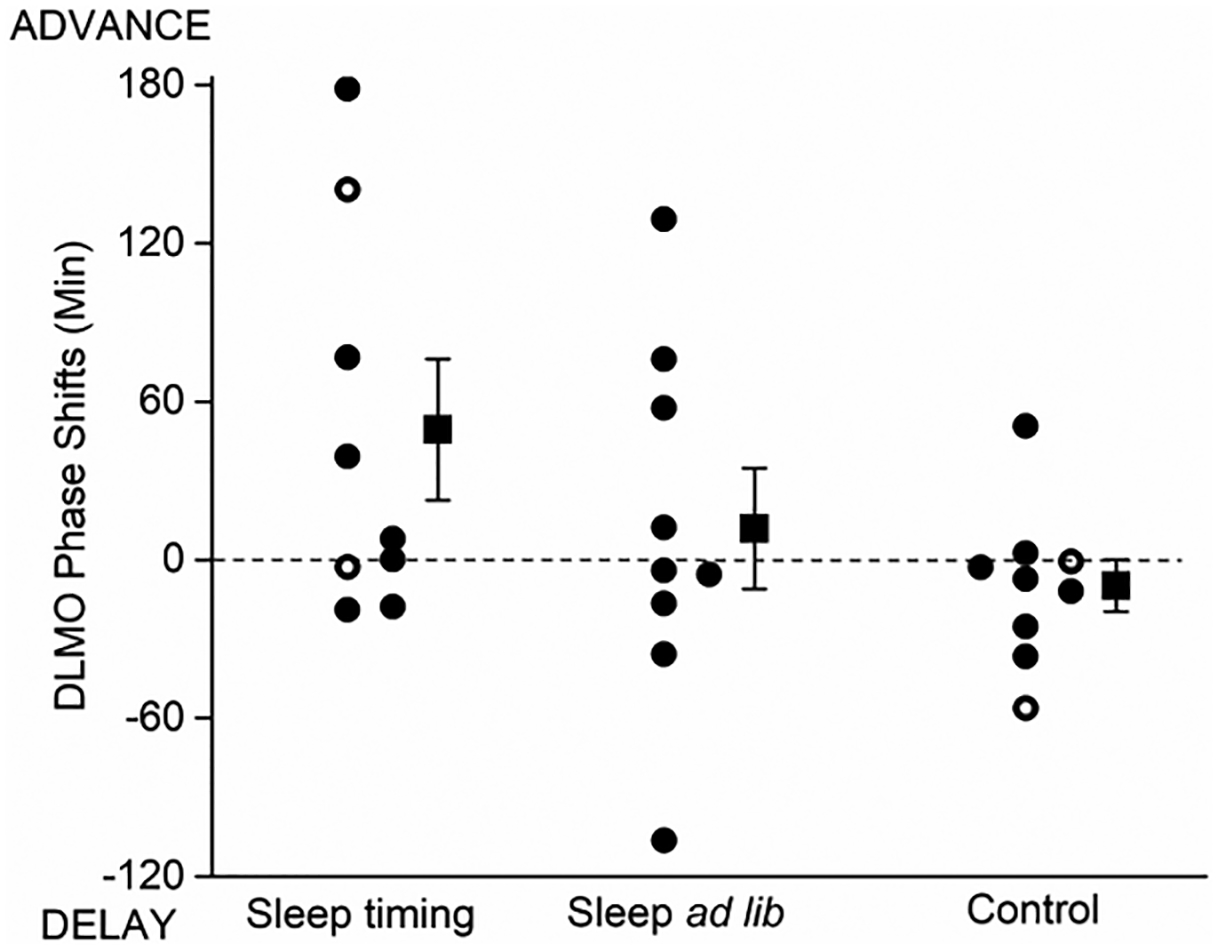

Circadian phase

DLMO was not significantly different between the groups before the NS. The ST and SA groups phase advanced by an average of 44.2±23.7 minutes, and 11.8±22.8 minutes respectively, whereas the Control group phase delayed by 9.7±9.9 minutes (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Individual and group mean (±SEM) circadian phase shifts of salivary dim light melatonin onset (DLMO). Closed symbols represent DLMO calculated at 3pg/ml threshold, open symbols represent DLMO calculated at 1pg/ml threshold. The group mean ±SEM is shown offset to the right of each group.

There was no significant correlation between the clock time of baseline (pre-NS) DLMO and the magnitude of the phase shift for either group or when the data were combined (all p>0.1).

DISCUSSION

In this simulated shift work protocol, the participants were able to comply with their at-home instructions and remained in bed for 8h each afternoon/evening, and by doing so had similar actigraphy-estimated sleep durations on the NS to that on the DS. While in general older adults typically have difficulty sleeping at adverse times of day, we found that instructing these fairly healthy participants to remain in bed attempting to sleep for eight hours (ST group) was sufficient to allow them to get nearly two hours more sleep each day than the Control group. The ST group also obtained more actigraphically-assessed sleep than the SA group, who were sleeping at the same time of day but who were not instructed to remain in bed for eight hours. We also instructed the ST group participants to try to make their bedroom as dark and quiet as possible, and to turn off their phone when they went to bed. Participants in the Control and SA groups were not given those same instructions. The ~2h sleep loss in the Control group before every NS was due to a combination of spending less time in bed and a greater proportion of that time awake; ~34% of the TIB was spent awake in the Control group, compared to ~17% in the ST group. Therefore, the sleep hygiene aspects of the instructions, in addition to the instructions to remain in bed attempting to sleep for eight hours, likely contributed to the longer sleep duration in the ST group20.

It is notable that when given the choice, most of the Control group (7/9) went to bed in the morning, as about 75% of shift workers are reported to do. We hypothesize that this morning sleep would have satisfied enough of their homeostatic sleep drive21 that after an interruption (due to noise, or need to void) any light or other stimuli they were exposed to may have made it difficult to return to sleep during a time of high circadian propensity for wake22. The intermediate amount of sleep obtained in the SA group, about an hour more than the Control group but an hour less than the ST group, suggests that the placement of sleep in the afternoon had an independent impact on sleep duration, perhaps due to increased sleep pressure23. Whether a split sleep schedule (morning sleep + evening nap) would improve night shift performance in older workers remains to be tested. While we did not have polysomnography recordings to assess sleep architecture (SWS, REM sleep), we did find that longer actigraphically-assessed sleep durations were associated with faster reaction times and fewer attentional lapses, suggesting that they had slept longer.

Day shift reaction times were maintained on the night shifts in the ST group, whereas the Control group was significantly slower on night shifts, with speed slowing from night to night in the Control group. In line with the intermediate sleep in the SA group, the SA group had performance intermediate between the Control and ST groups. However, we found that all groups showed significantly more lapses on the NS than on the DS, and more lapses at the end of the NS than at the beginning. Despite their longer sleep and shorter wake duration before a NS, the ST group had three times as many lapses of attention on the NS as they had on the DS. This propensity to lose focus leaves individuals vulnerable to errors and accidents on the NS, potentially harming themselves or others7. While our participants were not permitted to drive themselves to or from the laboratory, shift workers are vulnerable for a motor vehicle accident on their post-shift commute home due to the length of time they have been awake combined with the early morning circadian phase at which there is high sleep propensity24,25.

The sleep timing intervention was not designed to shift the phase of the central circadian timing system to adapt to night work, but instead was designed to reduce homeostatic sleep pressure on NS. Nevertheless, participants in the ST group showed a modest (~45 minutes) phase advance of their dim light melatonin onset, although five of the nine showed little or no change in phase. This modest phase shift is unlikely to have contributed significantly to the overall differences in sleep duration, performance, or subjective sleepiness that we observed between the groups.

The differential influence of sleep duration before a night shift (affecting speed and vigilance, but not subjective sleepiness) and wake duration (affecting vigilance and sleepiness, but not speed) on the night shift, indicates that the ability of participants to accurately assess their performance may have been impaired8.

While we did find significant differences between the ST and Control groups, some of our findings were impacted by the small group size and the variability in self-selected sleep behaviour in the SA and Control groups. While some of the performance variability in our study was associated with sleep and/or wake duration, additional studies that explore other factors contributing to susceptibility to shift work are needed. Light can have an alerting effect26, and we therefore controlled the lighting during the work shifts in all groups. However, participants left the laboratory between shifts and their light exposure was not controlled. Therefore, group differences in light exposure could have contributed to some of the variability within or between the groups, and future studies where off-shift light exposure20 in older workers is controlled should be considered. Our study included paid participants who were not regular shift workers. Whether actual shift workers would adopt an afternoon-evening sleep schedule remains to be tested. It is likely that individuals with family members living in the same home would find it difficult to adopt the study sleep schedule, although we did not assess the impact of the protocol on the individual or their family dynamic.

In summary, shift work is challenging because the worker is attempting to remain awake and function at a biological time at which his/her internal circadian system is promoting sleep, and then attempting to sleep in the daytime when a long and consolidated sleep episode is difficult to achieve1. Insufficient sleep, prolonged wake duration prior to beginning night work, and working when the circadian system is promoting sleep all combine to impair alertness and performance on the NS. We tested an intervention requiring participants to remain in bed attempting to sleep for 8 hours and timed so that they would rise only 1–2 hours before the subsequent work shift, designed to prolong sleep and reduce wake duration prior to the next NS. This protocol was successful in leading to a longer sleep duration, which was associated with better psychomotor performance during NS. It also resulted in a shorter wake duration prior to the subsequent NS, which was associated with an improved ability to focus. Thus, this simple intervention could be a potential nonpharmacologic strategy to help shift workers and should be further explored.

WHAT THIS PAPER ADDS.

What is already known about this subject?

Older shift workers report more sleep problems than do younger workers. We previously reported that a combined strategy of scheduled afternoon-evening sleep and enhanced lighting on the night shift could improve night shift performance in older adults.

What are the new findings?

We found that older adults who remained in bed for 8h were able to sleep significantly longer and had significantly greater vigilance on the subsequent night shift than the Control group.

How might this impact on policy or clinical practice in the foreseeable future?

Our findings indicate that sleep homeostatic-based shift work treatments can improve adaptation to shift work in older adults. This strategy can be implemented by individual workers.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors wish to thank the study participants; Dr. Min Ju Kim for serving as Project Leader for some of the Control participant studies; Michael Harris and Joyce Hong for assistance with participant recruitment and data processing; the staff of the Brigham and Women’s Hospital Center for Clinical Investigation and the Partners Chronobiology Core for assistance with data collection; Joseph M. Ronda, M.S. for technical assistance; and Dr. Charles A. Czeisler for helpful advice in designing the study.

FUNDING

The studies were supported by NIH grant R01 AG044416 and were performed in the Brigham and Women’s Hospital Center for Clinical Investigation, part of Harvard Catalyst (Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center) and supported by NIH Award UL1 TR001102 and financial contributions from Brigham and Women’s Hospital and from Harvard University and its affiliated academic health care centers. EDC was supported by NIH fellowship T32 HL007901. JHK was supported by a grant from Dankook University. CMI and JFD were supported in part by NIH grant P01 AG09975 during the analysis.

Footnotes

COMPETING INTERESTS

None

REFERENCES

- 1.Dijk DJ, Czeisler CA. Contribution of the circadian pacemaker and the sleep homeostat to sleep propensity, sleep structure, electroencephalographic slow waves, and sleep spindle activity in humans. Journal of Neuroscience 1995; 15(5):3526–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Åkerstedt T, Wright KP Jr. Sleep loss and fatigue in shift work and shift work disorder. Sleep Medicine Clinics 2009; 4(2):257–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McHill AW, Hull JT, Wang W, Czeisler CA, Klerman EB. Chronic sleep curtailment, even without extended (>16-h) wakefulness, degrades human vigilance performance. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2018; 115(23):6070–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Cordova PB, Bradford MA, Stone PW. Increased errors and decreased performance at night: A systematic review of the evidence concerning shift work and quality. Work 2016; 53(4):825–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pilcher JJ, Huffcutt AI. Effects of sleep deprivation on performance: A meta-analysis. Sleep 1996; 19(4):318–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wagstaff AS, Sigstad Lie JA. Shift and night work and long working hours--A systematic review of safety implications. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health 2011; 37(3):173–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duffy JF, Zitting KM, Czeisler CA. The case for addressing operator fatigue. Reviews of Human Factors and Ergonomics 2015; 10(1):29–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bermudez EB, Klerman EB, Czeisler CA, Cohen DA, Wyatt JK, Phillips AJ. Prediction of vigilant attention and cognitive performance using self-reported alertness, circadian phase, hours since awakening, and accumulated sleep loss. PLoS ONE 2016; 11(3):e0151770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhou X, Ferguson SA, Matthews RW, Sargent C, Darwent D, Kennaway DJ, Roach GD. Mismatch between subjective alertness and objective performance under sleep restriction is greatest during the biological night. Journal of Sleep Research 2012; 21(1):40–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Härmä MI, IImarinen JE. Towards the 24-hour society-new approaches for aging shift workers? Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment and Health 1999; 25(6):610–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klerman EB, Wang W, Duffy JF, Dijk DJ, Czeisler CA, Kronauer RE. Survival analysis indicates that age-related decline in sleep continuity occurs exclusively during NREM sleep. Neurobiology of Aging 2013; 34(1):309–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klerman EB, Dijk DJ. Age-related reduction in the maximal capacity for sleep--implications for insomnia. Current Biology 2008; 18(15):1118–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Booker LA, Magee M, Rajaratnam SMW, Sletten TL, Howard ME. Individual vulnerability to insomnia, excessive sleepiness and shift work disorder amongst healthcare shift workers. A systematic review. Sleep Medicine Reviews 2018; 41:220–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McMenamin TM. Shift work and flexible schedules Monthly Labor Review. Division of Labor Force Statistics, Office of Employment and Unemployment Statistics, Bureau of Labor Statistics; December 2007. Collins SM, Casey RP. America’s Aging Workforce: Opportunites and Challenges. In: Aging SCo, ed. United States Senate, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Santhi N, Aeschbach D, Horowitz TS, Czeisler CA. The impact of sleep timing and bright light exposure on attentional impairment during night work. Journal of Biological Rhythms 2008; 23(4):341–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chinoy ED, Harris MP, Kim MJ, Wang W, Duffy JF. Scheduled evening sleep and enhanced lighting improve adaptation to night shift work in older adults. Occupational and Environmental Medicine 2016; 73(12):869–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Åkerstedt T, Gillberg M. Subjective and objective sleepiness in the active individual. International Journal of Neuroscience 1990; 52(1–2):29–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Silva EJ, Wang W, Ronda JM, Wyatt JK, Duffy JF. Circadian and wake-dependent influences on subjective sleepiness, cognitive throughput, and reaction time performance in older and young adults. Sleep 2010; 33(4):481–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Benloucif S, Burgess HJ, Klerman EB, Lewy AJ, Middleton B, Murphy PJ, Parry BL, Revell VL. Measuring melatonin in humans. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine 2008; 4(1):66–69. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hébert M The effects of prior light history on the suppression of melatonin by light in humans. Journal of Pineal Research 2002; 33(4):198–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fuller PM, Gooley JJ, Saper CB. Neurobiology of the sleep-wake cycle: Sleep architecture, circadian regulation, and regulatory feedback. Journal of Biological Rhythms 2006; 21(6):482–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shigeyoshi Y, Taguchi K, Yamamoto S, Takekida S, Yan L, Tei H, Moriya T, Shibata S, Loros JJ, Dunlap JC, Okamura H. Light-induced resetting of a mammalian circadian clock is associated with rapid induction of the mPer1 transcript. Cell 1997; 91:1043–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dijk DJ, Von Schantz M. Timing and consolidation of human sleep, wakefulness, and performance by a symphony of oscillators. Journal of Biological Rhythms 2005; 20(4):279–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee ML, Howard ME, Horrey WJ, Liang Y, Anderson C, Shreeve MS, O’Brien CS, Czeisler CA. High risk of near-crash driving events following night-shift work. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2016; 113(1):176–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lunn RM, Blask DE, Coogan AN, Figueiro MG, Gorman MR, Hall JE, Hansen J, Nelson RJ, Panda S, Smolensky MH, Stevens RG, Turek FW, Vermeulen R, Carreón T, Caruso CC, Lawson CC, Thayer KA, Twery MJ, Ewens AD, Garner SC, Schwingl PJ, Boyd WA. Health consequences of electric lighting practices in the modern world: A report on the National Toxicology Program’s workshop on shift work at night, artificial light at night, and circadian disruption. The Science of the Total Environment 2017; 607–608:1073–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cajochen C, Zeitzer JM, Czeisler CA, Dijk DJ. Dose-response relationship for light intensity and ocular and electroencephalographic correlates of human alertness. Behavioral Brain Research 2000; 115(1):75–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]