Abstract

Emissions from solid-fuel burning cookstoves are associated with 3 to 4 million premature deaths annually and contribute significantly to impacts on climate. Pellet-fueled gasifier stoves have some emission factors (EFs) approaching those of gas-fuel (liquid petroleum gas) stoves; however, their emissions have not been evaluated for biological effects. Here we used a new International Organization for Standardization (ISO) testing protocol to determine pollutant- and mutagenicity-EFs for a stove designed for pellet fuel, the Mimi Moto, and for two other forced-draft stoves, Xunda and Philips HD4012, burning pellets of hardwood or peanut hulls. The Salmonella assay-based mutagenicity-EFs (revertants/megajouledelivered) spanned three orders of magnitude and correlated highly (r = 0.99; n = 5) with EFs of the sum of 32 particle-phase polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs). The Mimi Moto/hardwood pellet combination had total-PAH- and mutagenicity-EFs 99.2 and 96.6% lower, respectively, compared to data published previously for the Philips stove burning non-pelletized hardwood, and 100 and 99.8% lower, respectively, compared to those of a wood-fueled three-stone fire. The Xunda burning peanut hull pellets had the highest fuel energy-based mutagenicity-EF (revertants/megajoulethermal) of the pellet stove/fuel combinations tested, which was between that of diesel exhaust, a known human carcinogen, and a natural-draft wood stove. Although the Mimi Moto burning hardwood pellets had the lowest fuel energy-based mutagenicity-EF, this value was between that of utility coal and utility wood boilers. This advanced stove/fuel combination has the potential to greatly reduce emissions in contrast to a traditional stove, but adequate ventilation is required to approach acceptable levels of indoor air quality.

Keywords: Cookstove emissions, Pellet cookstoves, Particulate matter (PM), Mutagenicity, Toxicology

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Approximately one-third of the world’s population relies each day on solid-fuel stoves that emit health- and climate-damaging pollutants (Bonjour et al., 2013). Globally, ambient air pollution and household air pollution are the leading environmental health risk factors, respectively accounting for 4.1 and 2.6 million deaths annually (Gakidou et al., 2017). A recent cohort study across 11 countries showed an increase in the risks of all-cause mortality and cardiovascular and respiratory disease among individuals living in homes using solid fuels (vs. clean modern fuels) for cooking (Hystad et al., 2019). Efforts have sought to reduce exposures to pollutants through the distribution and promotion of improved biomass cookstoves, though reductions in health effects have often been unsatisfactory (Smith et al., 2011, Mortimer et al., 2017, Romieu et al., 2009, Mortimer and Balmes, 2018).

The argument for “making the clean available rather than making the available clean” emphasizes the need for aggressive transitioning to the cleanest stove/fuel combinations (i.e., gas- and electricity-based solutions), as opposed to incremental steps up the “energy ladder” (Smith and Sagar, 2014). However, the World Health Organization (WHO) recognizes that rural vs. urban and peri-urban populations naturally require longer periods (on the order of decades vs. years) to transition completely to clean energy carriers (World Health Organization, 2014). Because 45% of the world’s population remains rural (The World Bank, 2019), there exists a need for more readily available, yet clean burning solid-fuel energy options.

Pellet-fueled, forced-draft gasifier cookstoves have emerged as one potential solution because they are relatively low-emitting in the lab (Jetter et al., 2012, Bilsback et al., 2018, Chen et al., 2016) and field (Champion and Grieshop, 2019, Shen et al., 2012, Garland et al., 2017) and potentially available for rural populations (Carter et al., 2018); however, they are not without their challenges, and distribution at scale can be difficult (Jagger and Das, 2018, Carter et al., 2018). These stoves typically utilize an adjustable-speed electric fan that drives air into the base and top of the fuel/combustion chamber, thereby providing a primary combustion zone in the fuel bed where gasification/pyrolysis occurs, and a secondary combustion zone above the fuel bed to promote more complete combustion of the gasification products (e.g., carbon monoxide, alkanes, light tars). These stoves are designed to burn fuel that is much more homogeneous in size and density (pellets) than typical gathered fuels (e.g., wood, biomass crop residues), and can include removable chambers of varying sizes to ease in the refueling process and to select a desired burn duration and level of cooking power.

It is expected that in a packed bed (e.g., pellet stove combustion chamber), the rates of combustion reactions are inversely proportional to fuel size, that gases surrounding fuel pieces are hotter as fuel size decreases (Thunman and Leckner, 2005), and that particle emissions may generally decrease with increased packed bed height (Tuttle and Junge, 1978); additionally, the moisture content of wood pellets is optimized for “efficient combustion” (U.S. EPA BurnWise, 2011). Fuels that are homogenous in composition and size can also reduce variability in emissions when compared to other gasifier-type stoves burning unprocessed or lightly processed wood or other biomass, which often produce 3–5× higher emission factors (EFs) of particulate matter with an aerodynamic diameter of ≤2.5 μm (PM2.5) in the field vs. lab (Wathore et al., 2017, Roden et al., 2009).

The potential for a homogenous fuel to reduce combustion emissions is illustrated by in-field emissions testing in Rwanda, wherein the Mimi Moto stove burning hardwood pellets met International Organization for Standardization (ISO) 19867–3 Tiers 4 and 5 (i.e., the two highest tiers as defined in Table D.1 of Appendix D) for PM2.5 and carbon monoxide (CO), respectively, and approached gas-stove like performance (Champion and Grieshop, 2019, International Organization for Standardization, 2018b). In addition, if consuming a sustainably harvested or waste feedstock such as sawdust or agricultural waste, the climate impacts of pellet fuels may be negligible. Although this stove/fuel combination offers the potential to drastically reduce emissions while remaining available and affordable, the biological effects of such emissions remain uncharacterized.

The mutagenicity and carcinogenicity of emissions from the indoor combustion of wood, coal, and other types of biomass have been reviewed and evaluated by IARC (World Health Organization International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2010) which concluded that the indoor emissions from coal are carcinogenic to humans (Group 1 carcinogen), and those from biomass fuel (primarily wood) are probably carcinogenic to humans (Group 2A carcinogen). Using a glass-tube furnace, we found that mutagenicity-EFs of various types of biomass fuels were as much as an order of magnitude higher during the smoldering vs. flaming phase of combustion (Kim et al., 2018). Additionally, we have evaluated the mutagenicity- and other pollutant-EFs for three cookstoves burning dry red oak, finding that a forced-draft stove (Philips) had mutagenicity and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH) EFs >95% lower than those from a three-stone fire (TSF) (Mutlu et al., 2016).

To extend these studies, we report results using the Philips forced-draft stove and two others (Mimi Moto and Xunda) burning compressed pellets comprised of either hardwood or peanut hulls. As before, we determined many EFs, including particulate matter (PM), mutagenicity in Salmonella, and 32 particle-phase PAHs. We correlated the EFs, compared those factors among the three stoves and two fuel types, and compared the mutagenicity-EFs to those of other combustion emissions to provide an indication of the relative health impact of these advanced biomass-fueled stoves.

2. Experimental methods

2.1. Emissions testing and calculations

We conducted testing and sampled emissions as described previously (Mutlu et al., 2016, Jetter et al., 2012) and detailed in Appendix A. In brief, we burned two pellet types, Greenway Super Premium Oak/Hardwood (HW) and a proprietary peanut-hull type (PH), with wet-basis moisture contents of 6.0 ± 0.2% and 7.6 ± 0.2% (mean ± standard deviation, SD), respectively. Fuel analysis results are presented in Table D.2 of Appendix D; notable differences are that HW pellets have higher volatile matter (85 vs. 61%), whereas the PH pellets have higher ash (22 vs. 1%). In residential pellet stoves, the amount of volatile matter greatly influences combustion because the heterogenous (i.e., chemical and physical processes that convert solid fuels to liquid and gaseous products) and homogenous (i.e., combustion of reduced condensed and gas-phase compounds) reactions occur much more rapidly than the subsequent char oxidation (of primarily fixed carbon) (Obernberger and Thek, 2004). These fuels were burned in three forced-draft, gasifier cookstoves: a Mimi Moto stove (MM), a Philips Model HD4012 (Ph), and a Xunda ‘Super Dragon’ stove (Xu) (Fig. 1). The five stove/fuel combinations tested are herein referred to as MMHW, MMPH, PhHW, XuHW, and XuPH; Ph burning PH was not tested.

Fig. 1.

From left to right: (a) Mimi Moto pellet-fueled, forced-draft stove, (b) Philips HD4012 forced-draft stove, (c) a Xunda ‘Super Dragon’ forced-draft stove

We utilized a modified ISO 19867–1 laboratory test protocol that consisted of 8 replicate high-power phases, with each phase comprised of a fuel-burning period of ~30 min followed by a 5-min shutdown period (International Organization for Standardization, 2018a). Stoves were operated on their highest setting with mean fuel burning rates (Table D.3) ranging from 11.5 to 14.4 g min−1; mean test-average modified combustion efficiencies were high, between 98.1% and 99.8%. Two independent “burns” (each consisting of the 8 replicates) were conducted per stove/fuel combination, with filter masses pooled per “burn” to comprise an independent sample for the mutagenicity assays (i.e., there was a total of two samples per stove/fuel combination). We also tested pellet-sized (but otherwise unprocessed) red oak cut from dowels as described in Appendix C and illustrated in Figs. C.1 and C.2.

In contrast to the previous studies with low-volume samplers (Jetter et al., 2012, Mutlu et al., 2016), PM was sampled using fabricated high-volume samplers to allow for sufficient PM capture required for the biological assays; this high-volume sampling is described in detail in Appendix A. Additionally, ultrafine particle (UFP) emissions were measured with an engine exhaust particle sizer (EEPS 3090, TSI, Shoreview, MN). We calculated pollutant- and mutagenicity-EFs on a number of bases, including energy delivered (megajoule delivered, MJd), fuel-energy consumed (megajoule thermal, MJth), fuel mass consumed (kg), and time (h). We extracted the organics from the filter-bound PM with dichloromethane (DCM) and determined the percentage of extractable organic material (%EOM) by gravimetric analysis as described (DeMarini et al., 2004), and determined the concentrations in the extracts of 32 particle-phase PAHs as reported previously (Kooter et al., 2011). We solvent-exchanged the extracts into dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) at a range of 2–6 mg EOM ml DMSO−1 for the mutagenicity assays.

2.2. Mutagenicity assays and calculations

We performed the Salmonella plate-incorporation mutagenicity assay (Maron and Ames, 1983), calculated mutagenic potencies of the EOM and PM, determined mutagenicity-EFs, and calculated Pearson (r) correlation coefficients among all the EFs (for the 5 stove/fuel combinations) as described previously (Mutlu et al., 2016) and detailed in Appendix B; normality was not assumed when calculating the Pearson coefficients given the sample size (n = 5). Briefly, we evaluated the EOMs from each burn in Salmonella strain TA98 with and without metabolic activation (S9) and strain TA100 with S9. There was adequate sample to test only in three strain/S9 conditions: the two strains with S9 permit the detection of both frameshift and base-substitution PAHs, whereas TA98 -S9 permits detection of nitroarenes. The slopes of the linear regressions of the dose-response curves were the mutagenic potencies expressed as revertants (rev) μg EOM−1, which were then multiplied by the %EOM to give rev μg PM−1. These values were then multiplied by the PM EFs to give mutagenicity-EFs (rev MJd−1, rev MJth−1, rev kg fuel−1) and a mutagenicity rate (rev h−1).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Pollutant-emission factors

Table 1 shows EFs for all pollutants measured. Because the ISO protocol was recently published (mid-2018), emission factors using this protocol are limited in the literature. Mass EFs correlated strongly (r = 0.97) between the high-volume sampler for PM and the post-cyclone sampler for PM2.5 (Fig. D.1), and mode number-weighted particle diameters (averaged over entire high-power phases) ranged between 11 and 19 nm; particle size is typically <2.5 μm for this type of combustion (Shen et al., 2017). Therefore, results reported here for PM (used in the mutagenicity assays) are assumed to be representative of PM2.5, the focus of our former studies (Kim et al., 2018, Mutlu et al., 2016). PM2.5 EFs for MMHW and PhHW were slightly (2–3%) higher than their respective PM EFs, due likely to the different sampling methods employed within this study, and potentially the additional dilution between the PM and PM2.5 sampling locations. PM EFs for replicate burns and comparisons between burns are presented in Tables D.4 and D.5. Significant differences (p < 0.05) were only observed between replicate burns for MMPH, and only when expressed as mg-PM kg−1. Replicate burns for XuPH had widely varying (but not significantly different) PM EFs (e.g., ~4-fold change in mg-PM kg−1 between burns). However, the Xunda stove was not designed specifically for pellet fuel, and there were variations in ignition and migration of the flame-front through the fuel bed between replicate tests. Therefore, apart from XuPH, replicate burns were generally consistent in terms of PM EFs.

Table 1.

Mean pollutant-emission factors

| Emission sourceb |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pollutanta | Emission factora | MMHW | MMPH | PhHW | XuHW | XuPH | Propanec |

| PM (HiVol) | mg MJd−1 | 44.3 | 17.4 | 61.8 | 71.7 | 185.0 | - |

| mg MJth−1 | 17.9 | 6.6 | 22.1 | 19.6 | 41.2 | - | |

| mg kg of fuel−1 | 331.5 | 90.3 | 405.1 | 314.0 | 498.6 | - | |

| mg h−1 | 268.1 | 73.2 | 354.7 | 329.8 | 562.1 | - | |

| PM2.5 | mg MJd−1 | 45.7 | 15.3 | 62.9 | 70.3 | 145.6 | 1.2 |

| mg MJth−1 | 18.3 | 5.8 | 22.5 | 19.2 | 32.0 | 0.8 | |

| mg kg of fuel−1 | 339.2 | 79.3 | 411.4 | 306.6 | 388.2 | 35.2 | |

| mg h−1 | 274.0 | 64.0 | 359.9 | 323.1 | 435.0 | 4.8 | |

| UFP | #×1012 MJd−1 | 1444 | 1997 | 1440 | 873 | d | - |

| #×1012 MJth−1 | 585 | 758 | 514 | 240 | d | - | |

| #×1012 kg of fuel−1 | 10829 | 10371 | 9407 | 3905 | d | - | |

| #×1012 h−1 | 8764 | 8427 | 8197 | 4020 | d | - | |

| OC | mg MJd−1 | 1.2 | 0.5 | 1.6 | 6.6 | 50.5 | - |

| mg MJth−1 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 1.8 | 10.5 | - | |

| mg kg of fuel−1 | 9.2 | 2.8 | 10.6 | 29.0 | 124.6 | - | |

| mg h−1 | 7.4 | 2.2 | 9.4 | 30.9 | 144.1 | - | |

| EC | mg MJd−1 | 1.4 | 2.4 | 11.7 | 34.2 | 42.4 | - |

| mg MJth−1 | 0.6 | 0.9 | 4.2 | 9.3 | 9.9 | - | |

| mg kg of fuel−1 | 10.1 | 11.3 | 72.6 | 139.3 | 114.1 | - | |

| mg h−1 | 8.6 | 9.9 | 68.1 | 156.4 | 133.9 | - | |

| OC:EC | fractional ratio | 0.9 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 1.2 | - |

| CO | g MJd−1 | 2.98 | 0.30 | 2.77 | 1.65 | 3.14 | 0.2 |

| g MJth−1 | 1.20 | 0.11 | 0.99 | 0.45 | 0.72 | 0.1 | |

| g kg of fuel−1 | 22.25 | 1.54 | 18.12 | 7.41 | 8.99 | 5.8 | |

| g h−1 | 18.00 | 1.25 | 15.81 | 7.73 | 9.88 | 0.8 | |

| THC | g MJd−1 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.16 | 0.56 | 0.0 |

| g MJth−1 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.12 | 0.0 | |

| g kg of fuel−1 | 0.18 | 0.10 | 0.18 | 0.68 | 1.44 | 0.6 | |

| g h−1 | 0.15 | 0.08 | 0.16 | 0.70 | 1.61 | 0.1 | |

| CH4 | g MJd−1 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.10 | 0.0 |

| g MJth−1 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.0 | |

| g kg of fuel−1 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.26 | 0.0 | |

| g h−1 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.29 | 0.0 | |

| NOx | g MJd−1 | 0.15 | 0.98 | 0.16 | 0.19 | 1.07 | 0.1 |

| g MJth−1 | 0.06 | 0.37 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.25 | 0.0 | |

| g kg of fuel−1 | 1.15 | 5.07 | 1.07 | 0.84 | 3.15 | 1.4 | |

| g h−1 | 0.93 | 4.12 | 0.94 | 0.87 | 3.42 | 0.2 | |

PM, particulate matter; PM2.5, particulate matter ≤ 2.5 μm in diameter; OC, organic carbon; EC; elemental carbon; CO, carbon monoxide; THC, total hydrocarbons; CH4, methane; NOx, oxides of nitrogen; MJd, megajoule energy delivered to the cooking pot.

Data for TSP, PM2.5, OC, and EC derived from samples collected on filters; all other data derived from continuous-emission monitoring. MMHW, Mimi Moto burning hardwood pellets; MMPH, Mimi Moto burning peanut hull pellets; PhHW, Philips stove burning hardwood pellets; XuHW, Xunda stove burning hardwood pellets; XuPH, Xunda stove burning peanut hull pellets.

Data from Mutlu et al. (2016).

Data missing.

Mean PM EFs were generally low for all stove/fuel combinations tested, ranging from 17 to 185 mg MJd−1 for MMPH and XuPH, respectively. For comparison, the Philips stove and a traditional TSF burning cut hardwood [and employing a modified Water Boiling Test (WBT) as opposed to the ISO protocol employed here] previously had PM2.5 EFs of 78 and 449 mg MJd−1, respectively (Mutlu et al., 2016); that same study reported a mean PM2.5 EF of 1.2 mg MJd−1 for a propane stove (Table 1), an order of magnitude lower than that of the cleanest stove/fuel combination in the present study. A study of four Chinese pellet-fueled cookstoves burning hardwood pellets using the WBT (Carter et al., 2014) reports mean cold-start (high-power) PM2.5 EFs ranging from 71 to 311 mg MJd−1, with uncertainty bounds overlapping our (overall lower) mean EFs (17–185 mg MJd−1). That same study reported the Philips stove burning hardwood pellets to have a mean (± SE) cold-start PM2.5 EF of 70 ± 10 mg MJd−1, in agreement with our data for the PhHW combination (62 ± 6 mg MJd−1; Table D.5). A separate study (Shen et al., 2012) determined a pellet-fueled stove burning pine pellets to have PM EFs ranging from 30 to 112 mg MJth−1, higher than our data (7–41 mg MJth−1; Table D.5) due potentially to differences in fuel type (softwood vs. hardwood) and stove choice. The Mimi Moto burning hardwood pellets (MMHW) had similar results for PM EFs compared to data published in the Clean Cooking Catalog (PM: 0.33 vs. 0.54 g kg−1) (Clean Cooking Alliance, 2019). Compared to median values from field-based in-home testing (Champion and Grieshop, 2019), mean PM EFs in the present study were similar (0.33 vs. 0.37 g kg−1). Thus, our reported PM EFs are representative of typical lab-based and, to a lesser extent, field-based pellet-stove operation, and generally occupy the space between a gas-stove and an advanced, forced-draft wood stove.

In the present study, according to ISO 19867–3 ‘Voluntary Performance Targets’ (International Organization for Standardization, 2018b) and using the upper bound of the 90% confidence interval about each mean, three of the five stove/fuel combinations met tier-5 for CO, and MMHW and XuPH met tier-4. In terms of PM, the MMHW and MMPH met tier-4, the PhHW and XuHW met tier-3 (i.e., consistent with gasifier stoves burning a heterogeneous fuel), and the XuPH met tier-2. CO EFs for MMHW were slightly higher than in-field performance (22 vs. 14 g kg−1) (Champion and Grieshop, 2019), due potentially to the inclusion of a shutdown using the ISO protocol, where for this stove type, the surface oxidation of the charred fuel results in high emissions of CO (Tryner et al., 2018). Interestingly, the combination MMPH had similar CO EFs as the propane stove (Table 1).

PM compositions [in terms of organic carbon to elemental carbon (OC:EC) ratios] were generally low and varied from 0.1 for PhHW to 1.2 for XuPH; advanced biomass stoves that typically operate in flaming conditions may have OC:EC ratios below one (Bilsback et al., 2019). Additionally, THC emissions were low, as expected of gasifier stoves (Jetter et al., 2012) and indicative of low emissions of organics. Gasifier stoves are sensitive to operation and fuel supply (Champion and Grieshop, 2019, Tryner et al., 2018), and transitions between flaming (higher EC) and smoldering (higher OC) phases of combustion can occur rapidly. The XuPH combination resulted in the most visible smoke during testing and had the overall highest and most variable EFs for all measured pollutants of all fuel/stove combinations tested in this study (Table D.6). Therefore, these pellet stoves can approach the performance of gas stoves for CO (aligning with tier-5), but PM (and other pollutant) emissions vary widely based on stove and fuel choice.

The %EOM for each of the replicate burns and comparisons between each are shown in Table D.7. Despite the ~2-fold difference in %EOMs between replicate burns for most stove/fuel combinations, none of the %EOMs were significantly different between replicates (due in part to the low n values). We did not average the %EOM values of the two replicate burns. Instead, we performed the calculations that required %EOM values (i.e., mutagenic potency and mutagenicity emission factors) for each replicate burn separately.

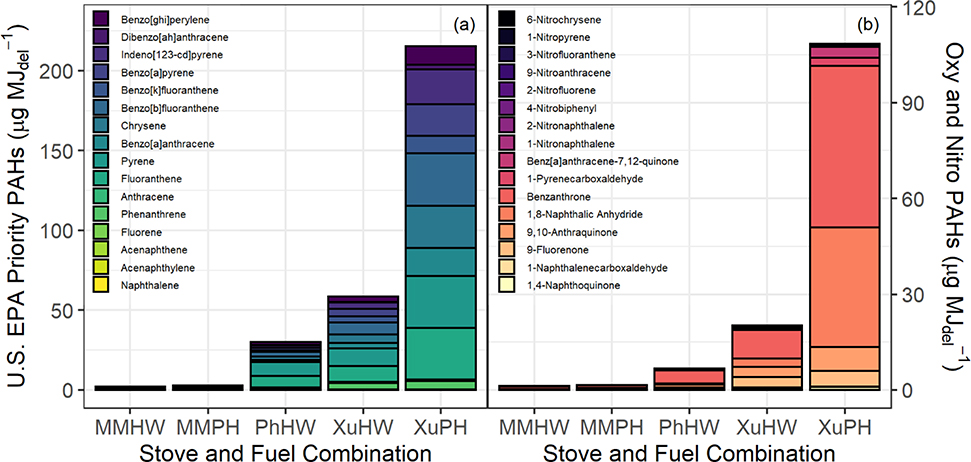

PAH EFs are plotted in Fig. 2 and tabulated in Table D.8, and they followed the trend of XuPH >> XuHW > PhHW >> MMPH > MHHW for both total EPA PAHs and total oxy- and nitro-PAHs. Total (particle-bound) PAHs reported here are an order of magnitude lower than those from a previous study on pellet cookstove emissions (0.001–0.06 vs. 0.01–0.66 mg MJth−1) (Shen et al., 2012), although PAH/PM ratios were within the range observed in that study, albeit generally lower (0.01–0.14% vs. 0.02–4.0%). A separate study determined total PAH/OC concentrations for pellet-fueled gasifier stoves to range narrowly between 2.4 and 3.2 mg g-OC−1 (Lai et al., 2019), compared to our observed range of 2.7–21 mg g-OC−1. Therefore, the PAH mass fractions observed in the present study were generally in agreement with previous studies on pellet-fueled gasifier cookstoves. It is important to note that cookstove PAH emissions (and their concatenate mutagenicities) can exist largely in the gas-phase (not characterized here), especially for less efficient stoves (Kim Oanh et al., 2002).

Fig. 2.

Stacked bar plots for (a) U.S. EPA priority PAHs and (b) oxy- and nitro- PAHs in units of μg MJd−1; data from Appendix Table D.8

Of the EPA PAHs, benzo[b]fluoranthene was predominant for MMHW, MMPH, and XuPH, in agreement with published data for gasifier cookstoves burning wood and straw pellets (Lai et al., 2019). Pyrene was predominant for PhHW and XuHW. Previously, pyrene was determined to be the predominant EPA PAH for traditional (i.e., TSF) and natural-draft (i.e., rocket) wood cookstoves (Mutlu et al., 2016); that same study determined benzanthrone to be the predominant oxy- or nitro-PAH for all stove/fuel combinations. Here, PAH EFs varied considerably between the stove/fuel combinations, with lowest and highest values (MMHW and XuPH, respectively) having 30- and 26-fold differences in total EPA and total oxy- and nitro-PAHs, respectively.

3.2. Mutagenic potencies of the EOM

The mutagenicity data of the extracts (rev plate−1) for all the replicate experiments and burns are shown in Table D.9. Additionally, Table D.10 shows the mutagenic potencies of the EOM (rev μg-EOM−1) for all the replicate burns, and Table D.11 shows the mean mutagenic potencies of the EOM for the replicate burns and statistical comparisons between them. With only two exceptions (PhHW in TA98 +S9 and TA98 -S9), the mutagenic potencies of the EOMs for any one stove/fuel combination were significantly different between replicate burns (Table D.11). Although the reason for this general lack of replicability is unclear, the inconsistent ignition and combustion in different regions of the fuel bed during the tests, especially with the Xunda stove (which was not designed specifically to burn pellets), may account for this result. Based on an average of the replicate data, the mutagenic potencies of the EOM of the stove/fuel combinations ranked similarly among the three strains: XuPH > PhHW > XuHW > MMPH ≈ MMHW. Thus, the mutagenic potency per mass of extractable organics was highest for the Xunda stove burning PH and lowest for the Mimi Moto stove burning either PH or HW. The EOMs from these stove/fuel combinations were most potent in strain TA98 -S9 or TA100 +S9, and all were the least potent in TA98 +S9. This suggests that, in general, the organics from these emissions exhibited more mutagenic activity due to nitroarenes and to base-substitution PAHs than to frameshift PAHs. The mutagenic potency of the EOM from one stove/fuel combination was similar across the 3 strain/S9 combinations. However, the mutagenic potencies of the EOMs among the 5 stove/fuel combinations varied approximately 6-, 12-, and 8-fold in TA98 -S9, TA98 +S9, and TA100 +S9, respectively, thereby illustrating the influence of stove/fuel choice on mutagenic potency of the EOM.

The mutagenic potencies of these EOMs were much lower than those found in our previous study using pieces of dry red oak fuel (Mutlu et al., 2016). Although the burn protocol varied between the two studies, the most likely variable was the fuel type (i.e., homogenous vs. heterogenous wood) and burning process (a more consistent migrating flame front with a packed bed of pellets vs. more inconsistent burning with semi-continuously fed pieces of fuel wood), as discussed in the ‘Study Outcomes’ section and explored in detail in Appendix C. This is indicated most clearly by the mutagenic potency of the EOM from the Philips stove burning dry red oak in the previous study versus hardwood pellets here. The mutagenic potency of the EOM was 4 to 14 times higher in the previous study compared to the present study (14.4 vs. 3.7, 23.2 vs. 3.1, and 17.8 vs. 5.4 rev μg EOM−1 for dry red oak vs. hardwood pellets in TA98 -S9, TA98 +S9, and TA100 +S9). This suggests that the more uniform combustion conditions provided by the pellets in a packed bed greatly reduced the mutagenic potency of the EOM relative to that produced by larger pieces of wood continuously fed.

3.3. Mutagenic potencies of the PM

Table D.12 shows the mutagenic potencies of the PM (rev mg PM−1) for all the replicate burns, and Table D.13 shows the mean mutagenic potencies of the PM for the replicate burns and statistical comparisons between them. Except for XuHW, the mutagenic potencies of the PM of all the other stove/fuel combinations varied ~2-fold or less and were not significantly different between replicate burns across all three strain/S9 combinations (Table D.13). The variability in the mutagenic potency of the PM between the XuHW burns may have been due to variation in combustion of this specific fuel/stove combination, highlighting the importance of matching a fuel type to a given stove type. Averaging the results from replicate burns, the mutagenic potencies of the PM ranked similarly among the 3 strain/S9 conditions: XuPH >> XuHW ≈ MMPH > PhHW > MMHW (Table D.13). Thus, the mutagenic potency per mass of PM was highest for the Xunda stove burning peanut hull pellets and lowest for the Mimi Moto stove burning hardwood pellets. The mutagenic potency of the PM from one stove/fuel combination was similar across the 3 strain/S9 combinations. However, the mutagenic potencies of the PM among the 5 stove/fuel combinations varied approximately 25-, 50-, and 38-fold in TA98 -S9, TA98 +S9, and TA100 +S9, respectively. The larger variation in mutagenic potencies of these PMs in the presence of S9 likely reflected the ~30-fold range of total PAH concentrations among the extracts (Table D.8).

The mutagenic potencies of the PMs were much lower than those in our previous study using pieces of dry red oak fuel (Mutlu et al., 2016). Although the burn (and sampling) protocol varied between the two studies, the most likely variable was the fuel type and subsequently improved burning process. For example, the reduced mutagenic potency of the PM in the presence of S9 (the strains detect primarily PAHs in the presence of S9) by as much as an order of magnitude for the Philips stove in the present study vs. the previous study (6.2-fold in TA98 +S9 and 12-fold in TA100 +S9) is consistent with the approximately order-of-magnitude lower concentration of total PAHs in the PM here using pellets (596 μg g-particle−1; Table D.8) vs. the previous study with pieces of wood (5837 μg g-particle−1; Table S2 of Mutlu et al.) for the Philips stove.

3.4. Mutagenicity-emission factors and rates

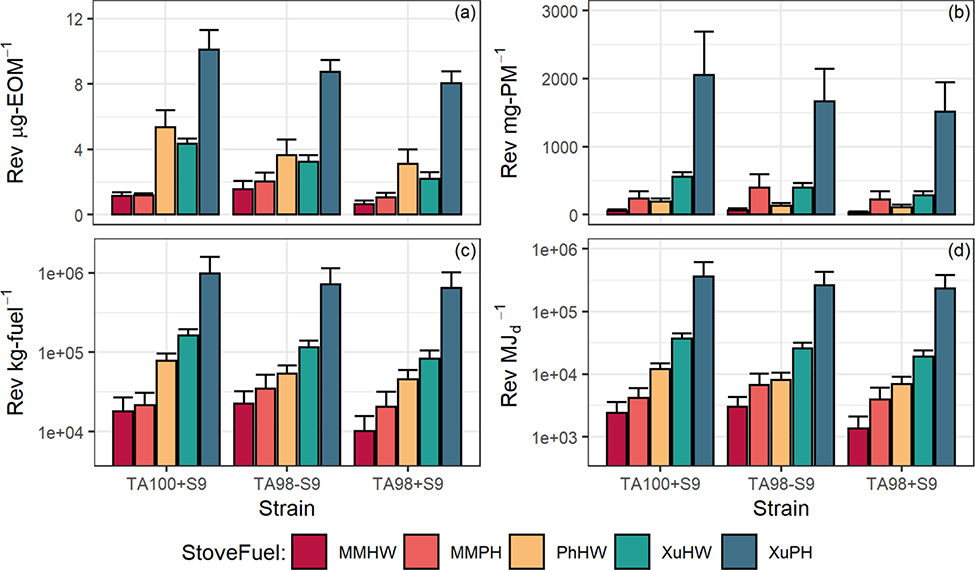

Mutagenicity-EFs and rates are presented in Fig. 3 and Tables D.14-D.21. In general, mutagenicity-EFs and rates were not significantly different between replicate burns except for (a) XuHW among all three strain/S9 combinations, and (b) PhHW in TA100 +S9, which detects PAHs, for rev h−1 (Table D.21). When the values were averaged and expressed as rev kg-fuel−1 or rev MJd−1 (Fig. 3c and d) or rev h−1, the stove/fuel combinations ranked as XuPH >> XuHW > PhHW > MMPH ≈ MMHW regardless of strain/S9 combination. Thus, the mutagenicity-EFs and rates were highest for the Xunda stove burning either fuel and lowest for the Mimi Moto burning either fuel.

Fig. 3.

Mutagenic potencies ± SE of (a) the EOM and (b) particles; data from Tables D.11 and D.13. Mutagenicity-emission factors ± SE expressed as (c) rev kg-fuel−1 and (d) rev MJd−1; data from Tables D.15 and D.17

The mutagenicity-EFs and rates were the highest in strain TA98 –S9 or TA100 +S9 and lowest in TA98 +S9. Thus, more of the mutagenicity was due to nitroarenes and base-substitution PAHs than to frameshift PAHs. The mutagenicity-EFs and rates among the 5 stove/fuel combinations varied similarly across the 3 strain/fuel combinations. For example, the rev MJd−1 for the stove/fuel combinations varied 87-, 172-, and 150-fold in TA98 –S9, TA98 +S9, and TA100 +S9, respectively. The larger variation in the presence of S9 likely reflected the 39- to 93-fold range of total PAH EFs (MJd) among the extracts (Table D.8). The rev MJd−1 in TA100 +S9 (which detects PAHs) of the Philips stove burning hardwood pellets (Table D.17) was 18 times lower than when burning dry red oak (0.1 vs. 1.8 × 105) (Mutlu et al., 2016). This order-of-magnitude reduction parallels the order-of-magnitude reduction (12-fold) in μg PAHs MJd−1 between the Philips stove burning hardwood pellets in the present study (36.8 μg-PAHs MJd−1; Table D.8) and burning dry red oak in the previous study (457 μg-PAHs MJd−1; Table S2 of Mutlu et al.). Therefore, the mutagenicity-EFs generally tracked with PAH EFs.

The mutagenicity-EFs of the cleaner-burning pellet stove/fuel combinations tested here (MMHW and MMPH) were 2–3 orders of magnitude lower than those of traditional and improved natural-draft cookstoves burning wood (TA98 and TA100, -S9 and +S9: range 0.8–2.9 × 107 rev kg−1) (Mukherji and Swain, 2002) and 1–2 orders of magnitude lower than those burning wood and sawdust briquettes (TA98 and TA100, -S9 and +S9: range 0.4–2.3 × 106 rev kg−1) (Kim Oanh et al., 2002). Additionally, the mutagenicity-EFs determined here (in general) correlated positively with PM EFs and negatively with stove thermal efficiencies, as previously observed for cookstoves (Shen, 2017). Our results indicate that the pellets likely provided more uniform combustion conditions (as did sawdust briquettes vs. wood in Kim Oanh et al.), which reduced the mutagenicity- and pollutant-EFs. Fig. D.2 of Appendix D shows time series plots of CO2 concentrations (as an indicator of fuel-burning rate) measured in a constant-flow dilution tunnel for the Philips stove burning cut red oak and hardwood pellets and highlights the increased variability in burning rates and conditions observed with cut red oak fuel compared to pellets.

3.5. Correlations among emission factors

Pearson correlation coefficients (r) and their statistical significance using mean EFs expressed per MJd for the five stove/fuel combinations for all pollutants and the TA100 +S9 results (because this strain detects primarily PAHs) are tabulated in Table D.22. Excluding UFP emissions (whose trends are described below), all pollutant- and mutagenicity-EFs were strongly and significantly correlated (r ≥ 0.92; p < 0.05) except for CO (r = 0.31–0.66), EC (r = 0.77–0.87), and nitrogen oxides (NOx) (r = −0.29–0.65). Consistent negative correlations for UFP suggest that lower mass emissions of the pollutants reported here resulted in higher particle number counts, agreeing with emissions data for two-stage (i.e., gasifier) residential solid-fuel heating stoves (Trojanowski and Fthenakis, 2019). Although often considered a proxy for PM, CO is not a reliable predictor of personal exposure or contributions to indoor PM concentrations (and hence emissions) from cookstove use (Carter et al., 2017). Additionally, for gasifier stoves, the shutdown (i.e., char burnout) period included in the ISO protocol was expected to result in high CO emissions during that time, with relatively low concurrent PM emissions (Tryner et al., 2018, Tryner et al., 2016, Sakthivadivel and Iniyan, 2017).

We performed a similar correlation analysis using field-based data (for PM2.5, OC, EC, and CO) for the Mimi Moto burning hardwood pellets in Rwanda (Table D.23) (Champion and Grieshop, 2019). Correlations were weaker in the field dataset, with r values ranging between 0.32 and 0.64, reflecting the increased variability inherent to field testing and in-home use. Thus, the strong correlations we found here and previously (Mutlu et al., 2016) among most of the pollutant- and mutagenicity-EFs in a laboratory setting may not apply to field settings.

3.6. Comparisons to other stove/fuel combinations

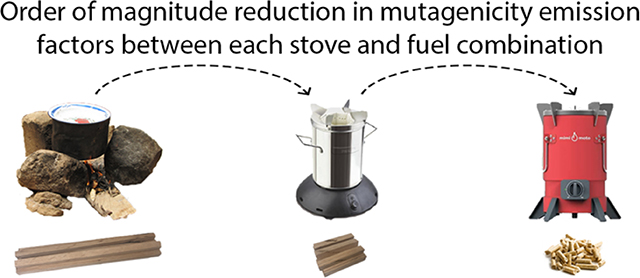

Tables D.24 and D.25 show the percent reductions in pollutant- and mutagenicity-EFs by the pellet-fueled stoves compared to previous results for the Philips stove and TSF, respectively, burning cut hardwood. Compared to the Philips stove burning cut hardwood (Table D.24), the Mimi Moto burning either HW or PH reduced many of the PAH EFs by ~98.5–99.4%; however, there was not a similar reduction in EFs for PM, CO, total hydrocarbons (THC), or NOx, with the latter likely due to the contributions from fuel nitrogen content (Table D.2) and to a lesser extent, thermal NOx. The mutagenicity-EF was reduced by 94.1–96.6%, in alignment with PAH reductions. In contrast, the XuPH increased the EFs an average of 22%, and mutagenicity-EFs 413% (Table D.24). Therefore, a stove burning pellets that it was not designed to burn may have both pollutant- and mutagenicity-EFs exceeding those of a gasifier stove burning a heterogeneous fuel.

Compared to the TSF burning cut hardwood (Table D.25), the Mimi Moto burning either HW or PH reduced many of the PAH EFs by 99.8–100% and the mutagenicity-EF by 99.7–99.8%; CO and especially NOx EFs were reduced to a lower extent (or in some cases increased). Despite having the highest emissions reported here, the XuPH still reduced rev MJd−1 (for TA100 +S9) by ~72% compared to the TSF. These comparisons show that the MMHW or MMPH greatly reduced many pollutant- and mutagenicity-EFs relative to the Philips stove and TSF, suggesting their potential for reducing harmful health effects from emissions from biomass stoves. These comparisons also illustrate the need for pellet fuels and stoves to be properly matched to obtain the greatest reduction in overall emissions.

3.7. Study outcomes

Results of this study suggest that a transition to a pelletized fuel, burned in the same stove (e.g., Philips), can result in roughly an order-of-magnitude decrease in mutagenicity-EFs. This decrease is due to two factors: reduced mutagenic potency of the PM by a factor of 3–12, and reduced PM EFs by a factor of 1.1–1.3; therefore, the former dominates. It is necessary to explore potential reasons for this decrease in mutagenicity of the PM, which include but are not limited to the influence on both PM EFs and composition by: (a) test protocol choice (WBT vs. ISO), (b) fuel devolatilization/combustion properties, (c) mutagenicity of the pelletized vs. non-pelletized fuel, (d) fuel characteristics, and (e) stove operation characteristics. These are described and explored in detail in Appendix C. Briefly, regarding (a), unpublished emissions test data (Champion et al., in preparation) for both the Philips stove burning cut red oak and the Mimi Moto burning hardwood pellets suggest that protocol choice significantly (p < 0.05, two-tailed Wilcoxon rank sum test) affects PM2.5 mass emission factors and rates but not PM composition in terms of OC:EC or EC:TC (elemental carbon to total carbon) ratios; therefore it does not appear that use of the ISO vs. WBT protocol results in dissimilar PM composition. To explore point (b), we conducted thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) on all fuels tested (Fig. C.3 of Appendix C). Results suggest that devolatilization (and controlled combustion) properties were similar between hardwood fuels (pellets, red wood, or cut dowels), owing likely to similar volatile matter (VM) and fixed carbon (FC) contents. Regarding (c), we characterized the mutagenicity of EOM from the red oak dowel tests, and found that pollutant- and mutagenicity-EFs (apart from OC and THC) were similar between tests of the Mimi Moto burning hardwood pellets and cut red oak dowels (Tables C.1-C.3 of Appendix C). Therefore, this limited experimentation suggests that it is the fuel size/loading and packed bed combustion that results in emissions and mutagenicity reductions, as opposed to the processing of the fuel itself.

Regarding (d), the fuel characteristics are listed in Table D.2 and show that cut red oak and hardwood pellets have nearly identical VM and FC contents (in addition to all other components analyzed, e.g., carbon, hydrogen, ash). Therefore, both fuel devolatilization and controlled combustion characteristics (as determined by TGA) and the fuel composition data were markedly similar between the “unprocessed” and pelletized hardwood. These results suggest that reductions in mutagenicity-EFs realized by switching to a pelletized fuel were due to combustion properties occurring within the stove (likely due to size/shape/density of the pellets and inherently more uniform combustion) and not the innate fuel properties (e.g., composition, moisture content). Finally regarding (e), it is theorized that stove operation characteristics lead to both reductions in PM emissions and to a lower mutagenic potency of the PM produced. This may be due to the more transient nature of combustion and PM emissions in the semi-continuous feeding of fuel in a stove burning cut wood vs. the batch-fed nature of the same stove burning pellets, as illustrated by the variable combustion (indicated by CO2 concentration) shown in Fig. D.2. Larger pieces of wood fuel vs. wood pellets and chips result in lower combustion efficiency due to the significantly reduced specific surface area (Friberg and Blasiak, 2002), and therefore the relatively steady combustion and higher combustion efficiencies of a batch-fed pellet stove may be the basis for the significant reductions in mutagenicity-EFs observed in the present study.

3.8. Study limitations

Limitations of this work include (a) limited testing in the lab under controlled conditions, (b) limited number of fuel/stove combinations tested, and (c) limited number of operational variables explored (e.g., only high-power operation). In regards to point (a), and due to limited stove operator influence on fuel feeding in batch-loaded gasifier stoves, field results may be similar to our results here as evidenced by field data reported for the Mimi Moto showing PM and CO EFs generally in agreement with lab test results (Champion and Grieshop, 2019). However, emissions are operationally dependent, and ~10% of households in that field study experienced elevated emissions (on-par with a carefully operated TSF).

3.9. Comparison with other combustion sources and implications of pellet stove emissions for public health

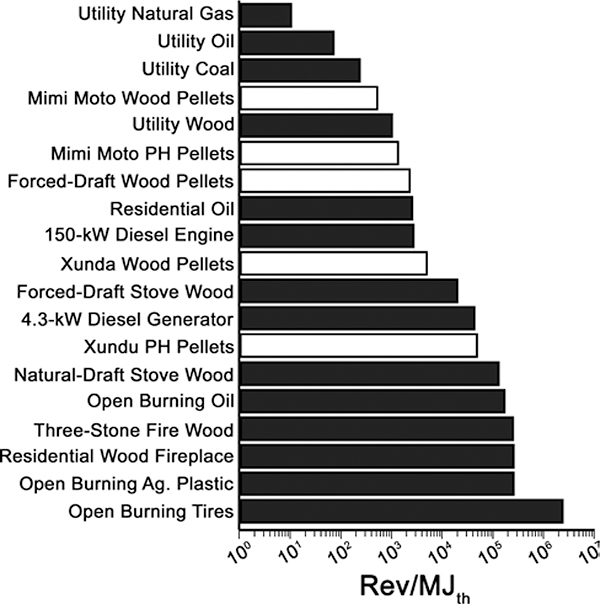

Fig. 4 places the mutagenicity-EFs based on fuel energy of these pellet stoves in context with those of other stoves, as well as with a variety of combustion emissions from controlled and open burning. Although the basis of energy delivered (MJd) is typically used in the context of cookstoves, normalization by fuel thermal energy consumed (MJth) is employed here to allow a comparison against other combustion sources. MMHW had the lowest mutagenicity-EF, which was between that of utility coal and utility wood boilers, whereas XuPH had the highest, between diesel generator exhaust and a natural-draft wood stove. Although the stove/fuel combinations tested had lower mutagenicity-EFs than those of traditional and even improved cookstoves (e.g., Philips), their mutagenicity-EFs remained at least two orders of magnitude greater than those of utility gas (and likely liquified petroleum gas combustion) and not much better (or slightly worse in the case of XuPH) than those of diesel exhaust, a known human carcinogen.

Fig. 4.

Comparison of mutagenicity-emission factors in strain TA98 +S9 (rev MJth−1) for a variety of combustion emissions. Data for diesel engines (Mutlu et al., 2015); data for remaining black bars (DeMarini et al., 1992, 1994, Mutlu et al., 2016, DeMarini et al., 2017). Data for white bars are from Table D.19. We calculated the mutagenicity-emission factor for the 150-kW diesel engine data (Turrio-Baldassarri et al., 2004) and published that value (2.76 × 103 rev MJth−1 in TA98 +S9) previously (Mutlu et al., 2015)

These results suggest that unvented emissions from these pellet stoves would likely result in poor indoor air quality. An additional caveat is that the PM from pellet-fueled gasifier cookstoves contains high fractions of inorganic ions (not characterized here) (Lai et al., 2019), including alkaline earth and alkali metals, which are reactive and electropositive and form alkaline oxides and peroxides (i.e., cellular reactive oxidative species) (Jomova and Valko, 2011). Along with mutagenicity and potential carcinogenicity, air pollution associated with emissions from household biomass stoves also causes telomere shortening (Li et al., 2019), which is the shortening of the ends of chromosomes and is associated with aging and chronic disease.

Nonetheless, pellet fuels may provide large populations with significant reductions in both pollutant- and mutagenicity-EFs. However, pellet fuel manufacturing and distribution is difficult to employ at scale (Jagger and Das, 2018, Carter et al., 2018). Subsidies are needed due to trade inequalities in rural regions where pellets are sold for much higher costs than the original feedstock material, and production efficiency has a large impact on final pellet cost (Carter et al., 2018); thus, small-scale operations may not be viable in competing with other fuels. In terms of climate, and concerning the entire life-cycle of pellets vs. cord wood (in the context of home heating and pellet demand in the Southeastern U.S.), the contribution of carbon dioxide equivalents is ~3× lower for pellets, due primarily to reductions of emissions by pellets during in-home combustion (Duden et al., 2017). In Rwanda, and dependent on both feedstock sourcing and upstream energy supply, pellet fuels approached or even subceeded the climate forcing of LPG (Champion and Grieshop, 2019). Therefore, both costs and climate impacts are likely country- and even community-dependent.

In terms of CO, the Mimi Moto burning hardwood pellets (meeting former International Workshop Agreement Tier 4 for CO) (Clean Cooking Alliance, 2012) could in theory meet WHO 24-h guidelines for CO if replacing TSF use in a home by ~70%; however, the continued use of traditional wood and charcoal stoves (“stacking”) quickly (on the order of minutes per day) negates PM2.5 reductions from the use of an improved stove type burning any fuel type (Johnson and Chiang, 2015). Despite its myriad health and climate impacts, the TSF remains an affordable, versatile, and durable technology (Ruiz-Mercado and Masera, 2015, Dickinson et al., 2019, Gould et al., 2020). Therefore, any intervention requires near-exclusive community-wide use of clean-burning fuels to lower pollutant concentrations to specific targets (e.g., the WHO interim target of 35 μg m−3 for PM2.5). Improving single contributors to hazardous indoor pollution, such as providing an advanced biomass cookstove alone, is not likely to improve health outcomes (Mortimer and Balmes, 2018).

4. Conclusions

The present study assessed the mutagenicity of PM of five pellet cookstove/fuel combinations. Mutagenicity-EFs correlated with PAH EFs and spanned three orders of magnitude, with the dirtiest stove/fuel combination (XuPH) ranking on-par with diesel exhaust, and the cleanest (MMHW) between those of utility wood and coal boilers. Therefore, careful matching of fuel and stove is recommended to reduce overall emissions and exposure from this advanced biomass cookstove technology. Although these stoves are an improvement over traditional and even many improved solid-fuel stoves, meeting WHO long-term targets for health will rely upon entire communities using clean cooking technologies (gas and electric) over a sustained period, along with reducing or eliminating any other sources of air pollution that may be present (Rosenthal et al., 2017). In the interim period, however, many communities do not have consistent access to gas and electric energy carriers, and pellet-fueled stoves have the potential to greatly reduce emissions, although adequate ventilation is required to assure acceptable indoor air quality.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Pellet cookstoves can be a clean energy solution for those reliant on solid fuels

Here, five pellet cookstove/fuel combinations were assessed for PM mutagenicity

Mutagenicity emission factors spanned 3 orders-of-magnitude & correlated with PAHs

Cleanest combination was similar to utility boiler; dirtiest to that of diesel PM

Pellet stoves can greatly reduce emissions, but adequate ventilation is required

Acknowledgements

Funding for this research was provided by the intramural research program of the Office of Research and Development of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Research Triangle Park, NC. The authors thank H. Beeltje (TNO) for help with the PAH analysis, Ed Brown (U.S. EPA) for help with the TGA, and Bill Linak (U.S. EPA) for guidance on the study and manuscript. This article was reviewed by the Biomolecular and Computational Toxicology Division, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and approved for publication. Approval does not signify that the contents reflect the views of the agency nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation for use.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Associated content

Appendices

The four appendices (A: Engineering and Chemistry Procedures, B: Mutagenicity Procedures, C: Comparison of Unprocessed and Pelletized Hardwood Fuels, and D: Supplemental Figures and Tables) are available free of charge at DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139488.

References

- BILSBACK KR, DAHLKE J, FEDAK KM, GOOD N, HECOBIAN A, HERCKES P, L’ORANGE C, MEHAFFY J, SULLIVAN A, TRYNER J, VAN ZYL L, WALKER ES, ZHOU Y, PIERCE JR, WILSON A, PEEL JL & VOLCKENS J 2019. A Laboratory Assessment of 120 Air Pollutant Emissions from Biomass and Fossil Fuel Cookstoves. Environ Sci Technol, 53, 7114–7125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BILSBACK KR, EILENBERG SR, GOOD N, HECK L, JOHNSON M, KODROS JK, LIPSKY EM, L’ORANGE C, PIERCE JR, ROBINSON AL, SUBRAMANIAN R, TRYNER J, WILSON A & VOLCKENS J 2018. The Firepower Sweep Test: A novel approach to cookstove laboratory testing. Indoor Air, 28, 936–949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BONJOUR S, ADAIR-ROHANI H, WOLF J, BRUCE NG, MEHTA S, PRUSS-USTUN A, LAHIFF M, REHFUESS EA, MISHRA V & SMITH KR 2013. Solid fuel use for household cooking: country and regional estimates for 1980–2010. Environmental Health Perspectives, 121, 784–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CARTER E, NORRIS C, DIONISIO KL, BALAKRISHNAN K, CHECKLEY W, CLARK ML, GHOSH S, JACK DW, KINNEY PL, MARSHALL JD, NAEHER LP, PEEL JL, SAMBANDAM S, SCHAUER JJ, SMITH KR, WYLIE BJ & BAUMGARTNER J 2017. Assessing Exposure to Household Air Pollution: A Systematic Review and Pooled Analysis of Carbon Monoxide as a Surrogate Measure of Particulate Matter. Environmental Health Perspectives, 125, 076002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CARTER E, SHAN M, ZHONG Y, DING W, ZHANG Y, BAUMGARTNER J & YANG X 2018. Development of renewable, densified biomass for household energy in China. Energy for Sustainable Development, 46, 42–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CARTER EM, SHAN M, YANG XD, LI JR & BAUMGARTNER J 2014. Pollutant Emissions and Energy Efficiency of Chinese Gasifier Cooking Stoves and Implications for Future Intervention Studies. Environmental Science & Technology, 48, 6461–6467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHAMPION WM & GRIESHOP AP 2019. Pellet-Fed Gasifier Stoves Approach Gas-Stove Like Performance during in-Home Use in Rwanda. Environmental Science & Technology, 53, 6570–6579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHEN Y, SHEN G, SU S, DU W, HUANGFU Y, LIU G, WANG X, XING B, SMITH KR & TAO S 2016. Efficiencies and pollutant emissions from forced-draft biomass-pellet semi-gasifier stoves: Comparison of International and Chinese water boiling test protocols. Energy for Sustainable Development, 32, 22–30. [Google Scholar]

- CLEAN COOKING ALLIANCE 2012. ISO International Workshop Agreement.

- CLEAN COOKING ALLIANCE. 2019. Clean Cooking Catalog: Mimi Moto [Online]. Available: http://catalog.cleancookstoves.org/stoves/434 [Accessed 20 May 2020].

- DEMARINI DM, BROOKS LR, WARREN SH, KOBAYASHI T, GILMOUR MI & SINGH P 2004. Bioassay-directed fractionation and salmonella mutagenicity of automobile and forklift diesel exhaust particles. Environmental Health Perspectives, 112, 814–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DEMARINI DM, LEMIEUX PM, RYAN JV, BROOKS LR & WILLIAMS RW 1994. Mutagenicity and chemical analysis of emissions from the open burning of scrap rubber tires. Environmental Science & Technology, 28, 136–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DEMARINI DM, WARREN SH, LAVRICH K, FLEN A, AURELL J, MITCHELL W, GREENWELL D, PRESTON W, SCHMID JE, LINAK WP, HAYS MD, SAMET JM & GULLETT BK 2017. Mutagenicity and oxidative damage induced by an organic extract of the particulate emissions from a simulation of the deepwater horizon surface oil burns. Environ Mol Mutagen, 58, 162–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DEMARINI DM, WILLIAMS RW, PERRY E, LEMIEUX PM & LINAK WP 1992. Bioassay-Directed Chemical Analysis of Organic Extracts of Emissions from a Laboratory-Scale Incinerator: Combustion of Surrogate Compounds. Combustion Science and Technology, 85, 437–453. [Google Scholar]

- DICKINSON KL, PIEDRAHITA R, COFFEY ER, KANYOMSE E, ALIRIGIA R, MOLNAR T, HAGAR Y, HANNIGAN MP, ODURO AR & WIEDINMYER C 2019. Adoption of improved biomass stoves and stove/fuel stacking in the REACCTING intervention study in Northern Ghana. Energy Policy, 130, 361–374. [Google Scholar]

- DUDEN AS, VERWEIJ PA, JUNGINGER HM, ABT RC, HENDERSON JD, DALE VH, KLINE KL, KARSSENBERG D, VERSTEGEN JA, FAAIJ APC & VAN DER HILST F 2017. Modeling the impacts of wood pellet demand on forest dynamics in southeastern United States. Biofuels, Bioproducts and Biorefining, 11, 1007–1029. [Google Scholar]

- FRIBERG R & BLASIAK W 2002. Measurements of mass flux and stoichiometry of conversion gas from three different wood fuels as function of volume flux of primary air in packed-bed combustion. Biomass & Bioenergy, 23, 189–208. [Google Scholar]

- GAKIDOU E, AFSHIN A, ABAJOBIR AA, ABATE KH, ABBAFATI C, ABBAS KM, ABD-ALLAH F, ABDULLE AM, ABERA SF, ABOYANS V, ABU-RADDAD LJ, ABU-RMEILEH NME, ABYU GY, ADEDEJI IA, ADETOKUNBOH O, AFARIDEH M, AGRAWAL A, AGRAWAL S, AHMADIEH H, AHMED MB, AICHOUR MTE, AICHOUR AN, AICHOUR I, AKINYEMI RO, AKSEER N, ALAHDAB F, AL-ALY Z, ALAM K, ALAM N, ALAM T, ALASFOOR D, ALENE KA, ALI K, ALIZADEH-NAVAEI R, ALKERWI AA, ALLA F, ALLEBECK P, AL-RADDADI R, ALSHARIF U, ALTIRKAWI KA, ALVIS-GUZMAN N, AMARE AT, AMINI E, AMMAR W, AMOAKO YA, ANSARI H, ANTÓ JM, ANTONIO CAT, ANWARI P, ARIAN N, ÄRNLÖV J, ARTAMAN A, ARYAL KK, ASAYESH H, ASGEDOM SW, ATEY TM, AVILA-BURGOS L, AVOKPAHO EFGA, AWASTHI A, AZZOPARDI P, BACHA U, BADAWI A, BALAKRISHNAN K, BALLEW SH, BARAC A, BARBER RM, BARKER-COLLO SL, BÄRNIGHAUSEN T, BARQUERA S, BARREGARD L, BARRERO LH, BATIS C, BATTLE KE, BAUMGARNER BR, BAUNE BT, BEARDSLEY J, BEDI N, BEGHI E, BELL ML, BENNETT DA, BENNETT JR, BENSENOR IM, BERHANE A, BERHE DF, BERNABÉ E, BETSU BD, BEURAN M, BEYENE AS, BHANSALI A, BHUTTA ZA, BICER BK, BIKBOV B, BIRUNGI C, BIRYUKOV S, BLOSSER CD, BONEYA DJ, BOU-ORM IR, BRAUER M, BREITBORDE NJK, BRENNER H, et al. 2017. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 84 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. The Lancet, 390, 1345–1422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GARLAND C, DELAPENA S, PRASAD R, L’ORANGE C, ALEXANDER D & JOHNSON M 2017. Black carbon cookstove emissions: A field assessment of 19 stove/fuel combinations. Atmospheric Environment, 169, 140–149. [Google Scholar]

- GOULD CF, SCHLESINGER SB, MOLINA E, LORENA BEJARANO M, VALAREZO A & JACK DW 2020. Long-standing LPG subsidies, cooking fuel stacking, and personal exposure to air pollution in rural and peri-urban Ecuador. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HYSTAD P, DUONG M, BRAUER M, LARKIN A, ARKU R, KURMI OP, FAN WQ, AVEZUM A, AZAM I, CHIFAMBA J, DANS A, DU PLESSIS JL, GUPTA R, KUMAR R, LANAS F, LIU Z, LU Y, LOPEZ-JARAMILLO P, MONY P, MOHAN V, MOHAN D, NAIR S, PUOANE T, RAHMAN O, LAP AT, WANG Y, WEI L, YEATES K, RANGARAJAN S, TEO K & YUSUF S 2019. Health Effects of Household Solid Fuel Use: Findings from 11 Countries within the Prospective Urban and Rural Epidemiology Study. Environmental Health Perspectives, 127, 57003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION FOR STANDARDIZATION 2018a. Clean Cookstoves and Clean Cooking Solutions - Harmonized Laboratory Test Protocols - Part 1: Standard Test Sequence for Emissions and Performance, Safety and Durability. [Google Scholar]

- INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION FOR STANDARDIZATION 2018b. Clean Cookstoves and Clean Cooking Solutions - Harmonized Laboratory Test Protocols - Part 3: Voluntary performance targets for cookstoves based on laboratory testing (TR 19867–3). [Google Scholar]

- JAGGER P & DAS I 2018. Implementation and scale-up of a biomass pellet and improved cookstove enterprise in Rwanda. Energy Sustain Dev, 46, 32–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JETTER J, ZHAO YX, SMITH KR, KHAN B, YELVERTON T, DECARLO P & HAYS MD 2012. Pollutant Emissions and Energy Efficiency under Controlled Conditions for Household Biomass Cookstoves and Implications for Metrics Useful in Setting International Test Standards. Environmental Science & Technology, 46, 10827–10834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JOHNSON MA & CHIANG RA 2015. Quantitative Guidance for Stove Usage and Performance to Achieve Health and Environmental Targets. Environmental Health Perspectives, 123, 820–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JOMOVA K & VALKO M 2011. Advances in metal-induced oxidative stress and human disease. Toxicology, 283, 65–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KIM OANH NT, NGHIEM LH & PHYU YL 2002. Emission of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons, Toxicity, and Mutagenicity from Domestic Cooking Using Sawdust Briquettes, Wood, and Kerosene. Environmental Science & Technology, 36, 833–839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KIM YH, WARREN SH, KRANTZ QT, KING C, JASKOT R, PRESTON WT, GEORGE BJ, HAYS MD, LANDIS MS, HIGUCHI M, DEMARINI DM & GILMOUR MI 2018. Mutagenicity and Lung Toxicity of Smoldering vs. Flaming Emissions from Various Biomass Fuels: Implications for Health Effects from Wildland Fires. Environmental Health Perspectives, 126, 017011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KOOTER IM, VAN VUGT MATM, JEDYNSKA AD, TROMP PC, HOUTZAGER MMG, VERBEEK RP, KADIJK G, MULDERIJ M & KRUL CAM 2011. Toxicological characterization of diesel engine emissions using biodiesel and a closed soot filter. Atmospheric Environment, 45, 1574–1580. [Google Scholar]

- LAI A, SHAN M, DENG M, CARTER E, YANG X, BAUMGARTNER J & SCHAUER J 2019. Differences in chemical composition of PM2.5 emissions from traditional versus advanced combustion (semi-gasifier) solid fuel stoves. Chemosphere, 233, 852–861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LI S, YANG M, CARTER E, SCHAUER JJ, YANG X, EZZATI M, GOLDBERG MS & BAUMGARTNER J 2019. Exposure-Response Associations of Household Air Pollution and Buccal Cell Telomere Length in Women Using Biomass Stoves. Environmental Health Perspectives, 127, 87004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARON DM & AMES BN 1983. Revised methods for the Salmonella mutagenicity test. Mutation Research, 113, 173–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MORTIMER K & BALMES JR 2018. Cookstove Trials and Tribulations: What Is Needed to Decrease the Burden of Household Air Pollution? Annals of the American Thoracic Society, 15, 539–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MORTIMER KJ, NDAMALA C, NAUNJE AW, MALAVA J, KATUNDU C, WESTON W, HAVENS D, POPE D, BRUCE N, NYIRENDA M, WANG D, CRAMPIN A, GRIGG J, BALMES JR & GORDON S 2017. A Cleaner Burning Biomass-Fueled Cookstove Intervention To Prevent Pneumonia In Children Under 5 Years Old In Rural Malawi (caps): A Cluster Randomised Controlled Trial. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 195, A5975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MUKHERJI S & SWAIN AKV, CHANDRA 2002. Comparative mutagenicity assessment of aerosols in emissions from biofuel combustion.pdf. Atmospheric Environment, 36, 5627–5635. [Google Scholar]

- MUTLU E, WARREN SH, EBERSVILLER SM, KOOTER IM, SCHMID JE, DYE JA, LINAK WP, GILMOUR MI, JETTER JJ, HIGUCHI M & DEMARINI DM 2016. Mutagenicity and Pollutant Emission Factors of Solid-Fuel Cookstoves: Comparison with Other Combustion Sources. Environmental Health Perspectives, 124, 974–982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MUTLU E, WARREN SH, MATTHEWS PP, KING C, WALSH L, KLIGERMAN AD, SCHMID JE, JANEK D, KOOTER IM, LINAK WP, GILMOUR MI & DEMARINI DM 2015. Health effects of soy-biodiesel emissions: mutagenicity-emission factors. Inhalation Toxicology, 27, 585–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OBERNBERGER I & THEK G 2004. Physical characterisation and chemical composition of densified biomass fuels with regard to their combustion behaviour. Biomass and Bioenergy, 27, 653–669. [Google Scholar]

- RODEN CA, BOND TC, CONWAY S, OSORTO PINEL AB, MACCARTY N & STILL D 2009. Laboratory and field investigations of particulate and carbon monoxide emissions from traditional and improved cookstoves. Atmospheric Environment, 43, 1170–1181. [Google Scholar]

- ROMIEU I, RIOJAS-RODRIGUEZ H, MARRON-MARES AT, SCHILMANN A, PEREZ-PADILLA R & MASERA O 2009. Improved biomass stove intervention in rural Mexico: impact on the respiratory health of women. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 180, 649–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROSENTHAL J, BALAKRISHNAN K, BRUCE N, CHAMBERS D, GRAHAM J, JACK D, KLINE L, MASERA O, MEHTA S, MERCADO IR, NETA G, PATTANAYAK S, PUZZOLO E, PETACH H, PUNTURIERI A, RUBINSTEIN A, SAGE M, STURKE R, SHANKAR A, SHERR K, SMITH K & YADAMA G 2017. Implementation Science to Accelerate Clean Cooking for Public Health. Environmental Health Perspectives, 125, A3–A7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RUIZ-MERCADO I & MASERA O 2015. Patterns of stove use in the context of fuel-device stacking: rationale and implications. Ecohealth, 12, 42–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAKTHIVADIVEL D & INIYAN S 2017. Combustion characteristics of biomass fuels in a fixed bed micro-gasifier cook stove. Journal of Mechanical Science and Technology, 31, 995–1002. [Google Scholar]

- SHEN G, TAO S, WEI S, ZHANG Y, WANG R, WANG B, LI W, SHEN H, HUANG Y, CHEN Y, CHEN H, YANG Y, WANG W, WEI W, WANG X, LIU W, WANG X & MASSE SIMONICH SL 2012. Reductions in emissions of carbonaceous particulate matter and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons from combustion of biomass pellets in comparison with raw fuel burning. Environmental Science & Technology, 46, 6409–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHEN GF 2017. Mutagenicity of particle emissions from solid fuel cookstoves: A literature review and research perspective. Environmental Research, 156, 761–769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHEN GF, GADDAM CK, EBERSYILLER SM, WAL RLV, WILLIAMS C, FAIRCLOTH JW, JETTER JJ & HAYS MD 2017. A Laboratory Comparison of Emission Factors, Number Size Distributions, and Morphology of Ultrafine Particles from 11 Different Household Cookstove-Fuel Systems. Environmental Science & Technology, 51, 6522–6532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SMITH KR, MCCRACKEN JP, WEBER MW, HUBBARD A, JENNY A, THOMPSON LM, BALMES J, DIAZ A, ARANA B & BRUCE N 2011. Effect of reduction in household air pollution on childhood pneumonia in Guatemala (RESPIRE): a randomised controlled trial. The Lancet, 378, 1717–1726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SMITH KR & SAGAR A 2014. Making the clean available: Escaping India’s Chulha Trap. Energy Policy, 75, 410–414. [Google Scholar]

- THE WORLD BANK. 2019. Rural Population (% of total population) [Online]. Available: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.RUR.totl.zs [Accessed Aug. 16 2019].

- THUNMAN H & LECKNER B 2005. Influence of size and density of fuel on combustion in a packed bed. Proceedings of the Combustion Institute, 30, 2939–2946. [Google Scholar]

- TROJANOWSKI R & FTHENAKIS V 2019. Nanoparticle emissions from residential wood combustion: A critical literature review, characterization, and recommendations. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 103, 515–528. [Google Scholar]

- TRYNER J, TILLOTSON JW, BAUMGARDNER ME, MOHR JT, DEFOORT MW & MARCHESE AJ 2016. The Effects of Air Flow Rates, Secondary Air Inlet Geometry, Fuel Type, and Operating Mode on the Performance of Gasifier Cookstoves. Environmental Science & Technology, 50, 9754–9763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TRYNER J, VOLCKENS J & MARCHESE AJ 2018. Effects of operational mode on particle size and number emissions from a biomass gasifier cookstove. Aerosol Science and Technology, 52, 87–97. [Google Scholar]

- TURRIO-BALDASSARRI L, BATTISTELLI CL, CONTI L, CREBELLI R, DE BERARDIS B, IAMICELI AL, GAMBINO M & IANNACCONE S 2004. Emission comparison of urban bus engine fueled with diesel oil and ‘biodiesel’ blend. Science of the Total Environment, 327, 147–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TUTTLE KL & JUNGE DC 1978. Combustion Mechanisms in Wood Fired Boilers. Journal of the Air Pollution Control Association, 28, 677–680. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. EPA BURNWISE 2011. Pellet Stove Fact Sheet. [Google Scholar]

- WATHORE R, MORTIMER K & GRIESHOP AP 2017. In-Use Emissions and Estimated Impacts of Traditional, Natural- and Forced-Draft Cookstoves in Rural Malawi. Environmental Science & Technology, 51, 1929–1938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION 2014. Guidelines for Indoor Air Quality - Household Fuel Combustion. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION INTERNATIONAL AGENCY FOR RESEARCH ON CANCER 2010. IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans - Household Use of Solid Fuels and High-Temperature Frying. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.