Abstract

Study objective

Emergency Department (ED) visits decreased significantly in the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic. A troubling proportion of this decrease was among patients who typically would have been admitted to the hospital, suggesting substantial deferment of care. We sought to describe and characterize the impact of COVID-19 on hospital admissions through EDs, with a specific focus on diagnosis group, age, gender, and insurance coverage.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective, observational study of aggregated third-party, anonymized ED patient data. This data included 501,369 patient visits from twelve EDs in Massachusetts from 1/1/2019–9/9/2019, and 1/1/2020–9/8/2020. We analyzed the total arrivals and hospital admissions and calculated confidence intervals for the change in admissions for each characteristic. We then developed a Poisson regression model to estimate the relative contribution of each characteristic to the decrease in admissions after the statewide lockdown, corresponding to weeks 11 through 36 (3/11/2020–9/8/2020).

Results

We observed a 32% decrease in admissions during weeks 11 to 36 in 2020, with significant decreases in admissions for chronic respiratory conditions and non-orthopedic needs. Decreases were particularly acute among women and children, as well as patients with Medicare or without insurance. The most common diagnosis during this time was SARS-CoV-2.

Conclusion

Our findings demonstrate decreased hospital admissions through EDs during the pandemic and suggest that several patient populations may have deferred necessary care. Further research is needed to determine the clinical and operational consequences of this delay.

Keywords: COVID-19, Emergency department, Hospital admissions, Care deferment

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

As the novel coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) spread across the United States in 2020, emergency department (ED) visits declined steeply. An analysis of the data from the National Syndromic Surveillance Program demonstrated a 42% decrease in overall weekly ED visits nationwide [1]. Several additional studies showed a substantial decline in volume relative to 2019, including decreases in presentations for syncope, cerebrovascular disease, myocardial infarction, pneumonia, and for exacerbations of COPD and heart failure [[2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7]].

Although the advent of telehealth visits during the pandemic may have prevented some ED visits entirely for lower-acuity cases [8] and may have helped to preempt some chronic disease exacerbations [9], remote care cannot replace the treatment received during a hospital admission, or fully explain the observed drop in presentation. Instead, the decrease in ED presentations likely reflects the tendency for patients to defer care due to concerns about contracting or spreading COVID-19, even when they are acutely ill [10].

1.2. Importance

The American College of Emergency Physicians encouraged patients to avoid delaying necessary medical care during the pandemic, especially in emergency situations [11]. Despite this, the Society of Actuaries expects a low to moderate pent-up demand for ED services as restrictions resulting from the pandemic loosen, suggesting that the decrease in visits is the result of deferred care, and not simply the absence of need [12].

The deleterious effects of delayed care have been observed in the wake of natural disasters [[13], [14], [15]]. Furthermore, deferred care during the COVID-19 pandemic may already be leading to increased morbidity and mortality in many communities [[16], [17], [18], [19]]. This threatens to be particularly acute among disadvantaged communities, who have been hard hit by the pandemic itself, and are dependent on EDs for a larger proportion of their care [20,21]. While figures vary between locales, in aggregate, it is estimated that there were over 30,000 excess deaths across the United States between March 1st and April 25th, 2020 that were not attributable to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) [22].

1.3. Goals

In this study, we sought to assess and characterize the impact of COVID-19 on hospital admissions through EDs, with a specific focus on diagnosis groups, age, gender, and insurance coverage.

2. Methods

2.1. Data

This was a retrospective, observational study of aggregated third-party, anonymized ED patient data. The dataset included 501,369 unique visits from twelve EDs in Massachusetts ranging from 1/1/2019–9/9/2019 and 1/1/2020–9/8/2020. Historical patient data was queried from a database of patient coding and billing records provided by LogixHealth, a national coding, billing, and analytics company located in Bedford, MA. The timestamps of patient arrivals, which were used to determine their dates of arrival, were recorded and saved to a hospital database at the time of registration. The de-identified data was stored, prepared, analyzed, and visualized using Microsoft Excel 2016. Additional statistical analysis was performed using R statistical software.

2.2. Setting

To keep our analysis consistent with the timing of regionally specific COVID-19 waves, our study was limited to twelve EDs within Massachusetts. These EDs included community sites, with 2019 annual censuses ranging from about 11,000 to 61,000 thousand arrivals, and a mean of about 34,000.

2.3. Preparation

Patients from all sites were pooled and considered as a single population. We combined “transfers” with “admits”, considering all other dispositions to be non-admissions, and grouped the data by week, using January 1st of each year to denote the first day of the first week of the respective year. Patients between the ages of fifteen and eighty-five were grouped in ten-year increments, with additional age groups for under two, two through fourteen, and eighty-five and older. We aggregated the records into four insurance coverage categories: Medicare, Medicaid, Private, and Self-pay.

We extracted the primary International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) codes from each patient chart and linked them to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) Clinical Classifications Software Refined (CCSR) diagnosis mapping tool [23], where we applied the “Default CCSR Category Description” field to represent diagnosis groups. Two of these diagnosis groups were related to COVID-19: one for a positive diagnosis and another to indicate COVID-19 exposure and screening.

2.4. Analysis

We analyzed the total number of arrivals as well as the total hospital admissions by week, for both years. The focus was on admissions during weeks 11 through 36 (3/12/2019–9/9/2019 and 3/11/2020–9/8/2020) to assess the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. We chose this range because the governor of Massachusetts declared a state of emergency for the state on 3/10/2020, which coincided with the last day of the 10th week of 2020 [24]. This date range had 79,141 admissions, which included the two diagnoses related to COVID-19.

We developed a Poisson regression model to estimate the percent change from 2019 to 2020 for the number of hospital admissions through EDs by age group, gender, insurance coverage, and diagnosis (using the top 40 diagnosis groups by volume). We chose the largest category for insurance coverage, “Private”, as the basis for insurance coverage, the central age category, “Age 45–54,” as the basis for age, and “Female” as the basis for gender. The top 40 diagnoses accounted for 70% of all admissions, leaving the remaining "Other" diagnoses as the basis for the diagnosis category. We excluded both SARS-CoV-2 related diagnoses from the regression analysis.

3. Results

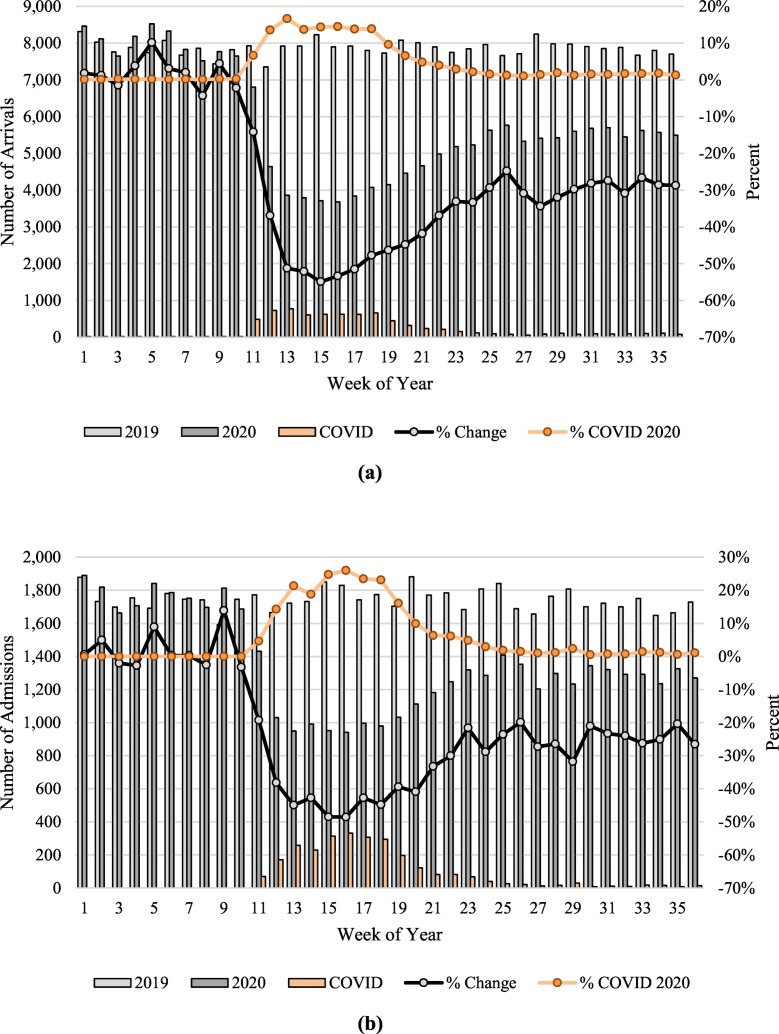

Starting in week 11 , just after the state of emergency declaration in Massachusetts, both the total volume and the hospital admission volume showed a steep decline. Week 15 ( 4/8/2020–4/14/2020) was the nadir of decreased volume with a 55% overall decrease in non-COVID volume, and a 49% reduction for non-COVID admissions, coinciding with 313 admissions for COVID-19. As of the end of week 36 (9/2/2020–9/8/2020), non-COVID admissions were 27% lower than the same week in 2019 (9/3/2019–9/6/2019). Fig. 1a and b display the total number of arrivals and admissions, respectively, across all sites by week for 2019 and 2020.

Fig. 1.

(a) Arrivals by Week. The first 10 weeks of both years are relatively consistent. A steep downward trend is observed in week 11 through week 15, after which point this trend changes and arrivals start to slowly recover. There is a notable increase in arrivals due to COVID-19 starting in week 11; (b) Admissions by Week. The first 10 weeks of 2019 and 2020 only display natural variations in hospital admissions through EDs. However, a steep decline in admissions occurred in week 11, continuing through week 15. Although admissions began to recover after week 15, they remained 25% lower than the 2019 admissions. Meanwhile, COVID-19 admissions appeared in week 11 of 2020, peaked at week 16, and continued to decline afterwards.

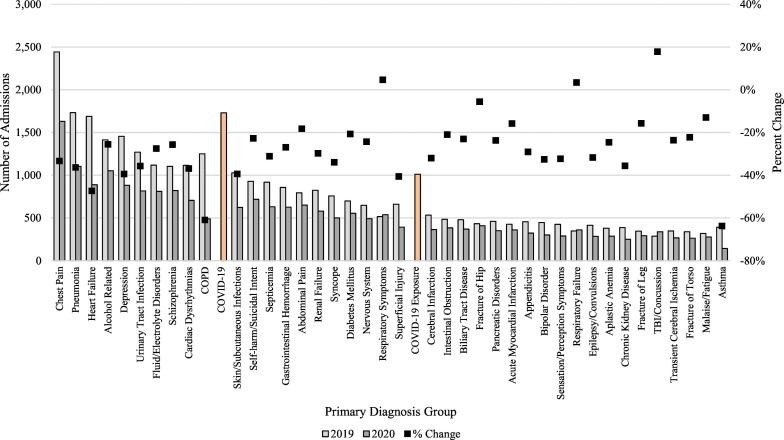

The decline in admissions was not consistent across all diagnostic categories. Asthma (−64%, 95% CI: −75% to −52%), COPD (−61%, 95% CI: −67% to −54%), and Heart Failure (−47%, 95% CI: −53% to −41%), had the most significant declines, while TBI/concussion (18%, 95% CI: 1% to 35%), respiratory symptoms (5%, 95% CI: −8% to 17%), and respiratory failure (3%, 95% CI: −12% to 18%) actually increased.

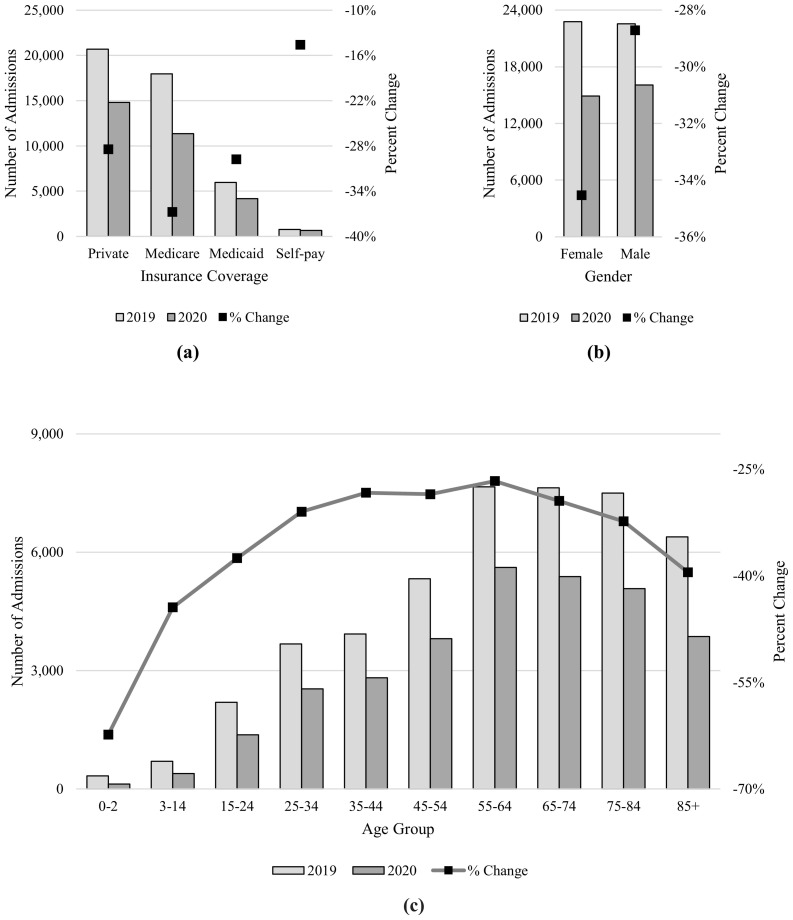

Infants of age 0–2 admissions dropped by 62% (95% CI: −75% to −50%) and patients aged 3 to 14 had 44% fewer admissions (95% CI: −54% to −35%), demonstrating significant delayed care for pediatrics. Female gender admissions dropped by 35% (95% CI: −36% to −33%), while male gender admissions only dropped by 29% (−30% to −27%). Other age groups had significantly fewer admissions, though not as substantial as the drop in pediatrics.

Medicare patients experienced the largest drop in admissions across insurance coverage categories (−37%, 95% CI: −39% to −35%), while self-pay patients experienced the smallest drop in admissions (−15%, 95% CI: −24% to −5%). Private and Medicaid patients’ admissions dropped 28% (95% CI: −30% to −27%) and 30% (95% CI: −33% to −26%), respectively.

Notably, among hospital admissions during weeks 11 through 36 of 2020, COVID-19 was the most common diagnosis group. Table 1 shows the difference in admissions from 2019 to 2020, the percent change, and the 95% confidence interval for each characteristic in weeks 11 through 36. Fig. 2a, b, and c display this information, categorized by age group, gender, and insurance coverage, respectively. Fig. 3 depicts the admissions for weeks 11 through 36 by the top 40 non-COVID diagnosis groups and the two COVID-19 related diagnoses.

Table 1.

Change in Admissions. Overall hospital admissions through EDs dropped 32% in weeks 11–36. The confidence intervals estimate the change in admissions from 2019 to 2020 for each independent characteristic.

| Characteristic | 2019 | 2020 | Difference | % Change | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||||

| Female | 22,780 | 14,912 | −7868 | −35% | −36% to −33% |

| Male | 22,553 | 16,077 | −6476 | −29% | −30% to −27% |

| Insurance Coverage | |||||

| Private | 20,683 | 14,802 | −5881 | −28% | −30% to −27% |

| Medicare | 17,956 | 11,357 | −6599 | −37% | −39% to −35% |

| Medicaid | 5965 | 4189 | −1776 | −30% | −33% to −26% |

| Self-pay | 781 | 667 | −114 | −15% | −24% to −5% |

| Age Group | |||||

| 0–2 | 332 | 125 | −207 | −62% | −75% to −50% |

| 3–14 | 700 | 389 | −311 | −44% | −54% to −35% |

| 15–24 | 2197 | 1373 | −824 | −38% | −43% to −32% |

| 25–34 | 3676 | 2538 | −1138 | −31% | −35% to −27% |

| 35–44 | 3930 | 2818 | −1112 | −28% | −32% to −24% |

| 45–54 | 5326 | 3808 | −1518 | −29% | −32% to −25% |

| 55–64 | 7656 | 5616 | −2040 | −27% | −30% to −24% |

| 65–74 | 7630 | 5383 | −2247 | −29% | −32% to −27% |

| 75–84 | 7501 | 5077 | −2424 | −32% | −35% to −29% |

| 85+ | 6388 | 3865 | −2523 | −39% | −43% to −36% |

| Diagnosis | |||||

| Chest Pain | 2443 | 1629 | −814 | −33% | −38% to −28% |

| Pneumonia | 1732 | 1102 | −630 | −36% | −42% to −30% |

| Heart Failure | 1689 | 889 | −800 | −47% | −53% to −41% |

| Alcohol Related | 1413 | 1052 | −361 | −26% | −32% to −19% |

| Depression | 1455 | 881 | −574 | −39% | −46% to −33% |

| Urinary Tract Infection | 1269 | 816 | −453 | −36% | −43% to −29% |

| Fluid/Electrolyte Disorders | 1116 | 809 | −307 | −28% | −35% to −20% |

| Schizophrenia | 1102 | 820 | −282 | −26% | −33% to −18% |

| Cardiac Dysrhythmias | 1115 | 704 | −411 | −37% | −44% to −29% |

| COPD | 1249 | 488 | −761 | −61% | −67% to −54% |

| Skin/Subcutaneous Infections | 1026 | 622 | −404 | −39% | −47% to −32% |

| Self-harm/Suicidal Intent | 928 | 717 | −211 | −23% | −31% to −14% |

| Septicemia | 916 | 631 | −285 | −31% | −40% to −23% |

| Gastrointestinal Hemorrhage | 855 | 625 | −230 | −27% | −36% to −18% |

| Abdominal Pain | 792 | 648 | −144 | −18% | −28% to −9% |

| Renal Failure | 824 | 579 | −245 | −30% | −39% to −21% |

| Syncope | 757 | 500 | −257 | −34% | −43% to −25% |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 698 | 554 | −144 | −21% | −31% to −11% |

| Nervous System | 647 | 490 | −157 | −24% | −34% to −14% |

| Respiratory Symptoms | 514 | 538 | 24 | 5% | −8% to 17% |

| Superficial Injury | 660 | 392 | −268 | −41% | −50% to −31% |

| Cerebral Infarction | 532 | 362 | −170 | −32% | −43% to −21% |

| Intestinal Obstruction | 483 | 382 | −101 | −21% | −33% to −9% |

| Biliary Tract Disease | 478 | 368 | −110 | −23% | −35% to −11% |

| Fracture of Hip | 431 | 407 | −24 | −6% | −19% to 8% |

| Pancreatic Disorders | 460 | 351 | −109 | −24% | −36% to −12% |

| Acute Myocardial Infarction | 426 | 359 | −67 | −16% | −29% to −3% |

| Appendicitis | 454 | 322 | −132 | −29% | −41% to −17% |

| Bipolar Disorder | 445 | 300 | −145 | −33% | −45% to −21% |

| Sensation/Perception Symptoms | 424 | 287 | −137 | −32% | −45% to −20% |

| Respiratory Failure | 347 | 359 | 12 | 3% | −12% to 18% |

| Epilepsy/Convulsions | 414 | 283 | −131 | −32% | −44% to −19% |

| Aplastic Anemia | 379 | 286 | −93 | −25% | −38% to −11% |

| Chronic Kidney Disease | 387 | 249 | −138 | −36% | −48% to −23% |

| Fracture of Leg | 344 | 290 | −54 | −16% | −30% to −1% |

| TBI/Concussion | 286 | 337 | 51 | 18% | 1% to 35% |

| Transient Cerebral Ischemia | 347 | 265 | −82 | −24% | −38% to −10% |

| Fracture of Torso | 337 | 262 | −75 | −22% | −36% to −8% |

| Malaise/Fatigue | 317 | 276 | −41 | −13% | −28% to 2% |

| Asthma | 389 | 141 | −248 | −64% | −75% to −52% |

Fig. 2.

(a) Admissions by Insurance Coverage. Admissions for Medicare patients decreased significantly by 37% while admissions for self-pay patients decreased only 15%; (b) Admissions by Gender. Admissions dropped 35% for females compared to only 29% for males; (c) Admissions by Age Group. Pediatric admissions, especially infants, dropped significantly while the 55–64 age group had the smallest drop in admissions.

Fig. 3.

Admissions Diagnosis. Asthma, COPD, and Heart Failure had the largest declines among the hospital admissions through EDs, while TBI, respiratory symptoms, and respiratory failure admissions actually increased. Notably, COVID-19 is the most common diagnosis in 2020.

Among the top 40 diagnosis groups, 14 had statistically significant drops after accounting for age, gender, and insurance coverage. We observed the largest declines for Asthma, COPD, and Heart Failure. Table 2 shows the results of the Poisson regression analysis, applying a 5% significance level. The model parameter estimate is the output of the model, which must be exponentiated to determine the estimated volume change and corresponding confidence intervals.

Table 2.

Poisson Regression Analysis Results. Female patients aged 45–54 with Private insurance and a diagnosis code other than the top 40 non-COVID diagnosis categories represent the reference group.

| Characteristic | Estimate | % Change | 95% CI | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year 2020 | -0.43 | -35% | -39% to -31% | <0.01 | |

| Insurance Coverage | |||||

| Private | (reference) | ||||

| Medicare | -0.10 | -10% | -13% to -6% | <0.01 | |

| Medicaid | 0.01 | 2% | -3% to 7% | 0.56 | |

| Self Pay | 0.30 | 36% | 21% to 52% | <0.01 | |

| Age Group | |||||

| 0-2 | -0.46 | -37% | -50% to -20% | <0.01 | |

| 3-14 | -0.32 | -27% | -37% to -16% | <0.01 | |

| 15-24 | 0.05 | 5% | -4% to 15% | 0.24 | |

| 25-34 | 0.00 | 0% | -7% to 7% | 0.92 | |

| 35-44 | 0.04 | 4% | -3% to 12% | 0.24 | |

| 45-54 | (reference) | ||||

| 55-64 | 0.04 | 4% | -2% to 10% | 0.20 | |

| 65-74 | 0.01 | 1% | -5% to 7% | 0.85 | |

| 75-84 | -0.04 | -4% | -10% to 2% | 0.19 | |

| 85+ | -0.08 | -8% | -13% to -2% | 0.01 | |

| Gender | |||||

| Female | (reference) | ||||

| Male | 0.08 | 8% | 5% to 12% | <0.01 | |

| Diagnosis | |||||

| All other Dx | (reference) | ||||

| Chest Pain | 0.04 | 4% | -4% to 12% | 0.36 | |

| Pneumonia | -0.02 | -2% | -10% to 7% | 0.68 | |

| Heart Failure | -0.17 | -16% | -24% to -8% | <0.01 | |

| Alcohol Related | 0.15 | 16% | 6% to 28% | <0.01 | |

| Depression | -0.07 | -7% | -15% to 3% | 0.17 | |

| Urinary Tract Infection | 0.05 | 6% | -5% to 17% | 0.30 | |

| Fluid/Electrolyte Disorders | 0.16 | 18% | 6% to 31% | <0.01 | |

| Schizophrenia | 0.07 | 8% | -3% to 20% | 0.16 | |

| Cardiac Dysrhythmias | -0.01 | -1% | -11% to 10% | 0.85 | |

| COPD | -0.40 | -33% | -41% to -24% | <0.01 | |

| Skin/Subcutaneous Infections | -0.08 | -7% | -18% to 4% | 0.20 | |

| Self-harm/Suicidal Intent | 0.35 | 42% | 27% to 58% | <0.01 | |

| Septicemia | 0.01 | 1% | -10% to 14% | 0.83 | |

| Gastrointestinal Hemorrhage | 0.22 | 24% | 11% to 40% | <0.01 | |

| Abdominal Pain | 0.16 | 17% | 4% to 32% | 0.01 | |

| Renal Failure | 0.10 | 11% | -2% to 25% | 0.09 | |

| Syncope | -0.03 | -2% | -15% to 11% | 0.71 | |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 0.22 | 25% | 10% to 42% | <0.01 | |

| Nervous System | 0.16 | 18% | 3% to 35% | 0.02 | |

| Respiratory Symptoms | 0.45 | 56% | 36% to 79% | <0.01 | |

| Superficial Injury | -0.10 | -10% | -22% to 4% | 0.15 | |

| Cerebral Infarction | 0.03 | 3% | -11% to 20% | 0.69 | |

| Intestinal Obstruction | 0.21 | 23% | 5% to 43% | <0.01 | |

| Biliary Tract Disease | 0.14 | 15% | -2% to 34% | 0.08 | |

| Fracture of Hip | 0.46 | 59% | 36% to 86% | <0.01 | |

| Pancreatic Disorders | 0.23 | 26% | 8% to 48% | <0.01 | |

| Acute Myocardial Infarction | 0.31 | 37% | 16% to 61% | <0.01 | |

| Appendicitis | 0.13 | 13% | -4% to 34% | 0.13 | |

| Bipolar Disorder | 0.16 | 17% | -1% to 38% | 0.06 | |

| Sensation/Perception Symptoms | 0.02 | 2% | -14% to 22% | 0.79 | |

| Respiratory Failure | 0.49 | 63% | 38% to 92% | <0.01 | |

| Epilepsy/Convulsions | 0.07 | 7% | -10% to 27% | 0.45 | |

| Aplastic Anemia | 0.19 | 21% | 2% to 45% | 0.03 | |

| Chronic Kidney Disease | 0.08 | 8% | -10% to 29% | 0.39 | |

| Fracture of Leg | 0.29 | 34% | 12% to 60% | <0.01 | |

| TBI/Concussion | 0.60 | 82% | 52% to 118% | <0.01 | |

| Transient Cerebral Ischemia | 0.15 | 17% | -2% to 39% | 0.09 | |

| Fracture of Torso | 0.14 | 15% | -4% to 38% | 0.13 | |

| Malaise/Fatigue | 0.14 | 15% | -4% to 39% | 0.13 | |

| Asthma | 0.12 | 13% | -7% to 36% | 0.22 | |

4. Discussion

Our goal was to describe and characterize the relative change in hospital admissions through EDs during the COVID-19 pandemic. We found a substantial decrease in admissions in the pediatric population, female gender, Medicare patients, and a variety of diagnoses related to chronic respiratory conditions and behavioral health. Meanwhile, orthopedic admissions displayed a relatively small change. Our results support and generalize similar studies by Kim, Harnett, and Westgard [1], [5], [7], and substantially expands the depth and breadth of the current body of information surrounding the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on emergency departments’ volume and hospital admissions from the ED with respect to patient demographics and diagnosis groups, as well as implications for resurgence, morbidity and mortality.

While less acute medical conditions may be evaluated and managed via telemedicine, hospital admissions are not fully replaceable by alternative modes of care due to their acuity and need for treatment. In this work, we investigated how the COVID-19 pandemic affected the trend of hospital admissions from EDs. We demonstrated a significant overall decline in admissions, which was non-homogeneous across age group, gender, insurance coverage, and diagnosis group.

The reduction in hospital admissions during the pandemic is a reflection of multiple contributing factors. The first, which has directly affected admissions, is the correlated reduction in arrivals, which can most likely be explained by patients balancing the urgency of an immediate health need with concerns regarding the risk of contracting SARS-CoV-2 infection in an ED. Lower admissions could also be due to reduced car travel (and therefore fewer car accidents), improved air quality, and decreased infectious disease transmission due to social distancing and use of masks. Anecdotal evidence also suggests better compliance with medication for chronic illnesses and an overall greater awareness of health maintenance during the pandemic.

We hypothesize that the decline in COPD and Asthma admissions represents a decline in patients with these chronic conditions presenting to the ED rather than patients with these diagnoses being miscategorized as having COVID-19. On the other hand, some of the Respiratory Failure and Respiratory Symptoms diagnoses could actually be COVID-19 cases, due to the diagnosis code not existing in the system at the onset of the pandemic.

Admissions for orthopedic diagnoses stayed relatively stable, most likely due to these conditions not being manageable at home or via telemedicine under any circumstances. However, non-orthopedic diagnoses admissions, such as appendicitis and urinary tract infections, which we had expected to remain stable, decreased significantly. We suspect these cases were either managed at home or were not admitted due to shared decision-making between the patient and provider. These results suggest a possible shift in medical decision-making in EDs to balance the potential risks of health deterioration and contraction of SARS-CoV-2 during the pandemic.

Given the observed decline in admissions, and the relationship between deferred care and increased morbidity, we hypothesize that future patients who deferred hospital admission may present with higher than normal severity. It is important for ED and hospital leaders to better understand and manage the specific causes associated with decreased ED volume and decreased hospital admissions. From the findings of this study we can anticipate a direct negative impact of pandemic-related deferment of care on patient outcomes. In addition, this impact on health outcomes may disproportionately affect disadvantaged populations, who often use EDs as their primary source of medical care and may not have access to telemedicine.

In addition to increased morbidity and mortality, a decrease in the number of admissions has an impact on overall staffing for both the ED and inpatient units. This affects multiple service lines including physicians, nurses, and ancillary staff. If admission volume does not recover soon, the ability of hospitals and providers to secure sufficient revenue to operate will be at risk [[25], [26], [27]]. Hospitals need to take this volume change into account and develop new forecasting models as they plan for future years. Once hospital administrators better understand the specific disease patterns with the highest decreases in volume, they should implement strategies to engage patients with the associated medical conditions and needs. These include engaging in community outreach, educational campaigns, and other strategies to ensure that patients are receiving the care they need in a timely manner. Hospitals can also engage in home health care initiatives to support the vulnerable populations by providing the care they need without them having to visit the ED.

This study was limited to EDs in Massachusetts and may not be generalizable to other areas that experience COVID-19 surges at different times with different levels of clinical knowledge about COVID-19. Future work should focus on the implications of deferred care, especially the potential for increased severity. A limitation of the data is the selection bias of how the primary diagnosis codes are selected by providers and coders, potentially causing various diagnosis groups to be over-represented or under-represented in the data. With that in mind, this bias would likely be consistent in both years, minimizing the effect.

5. Conclusion

In summary, we observed a 32% decrease in non-COVID admissions during weeks 11 through 36 in 2020 compared to the same weeks in 2019, with notable decreases in chronic respiratory conditions, non-orthopedic needs, pediatrics, females, patients with Medicare, and patients without health insurance. Our findings support those of recent other work and add significant depth to a range of diagnoses for which care has been delayed or deferred. Although telemedicine may replace lower acuity visits, it cannot replace the vigilant monitoring and potential for swift action characteristic of a hospital admission. The foregone admissions must be addressed via outreach and support for patients who may be suffering and dying due to prioritizing concerns of contracting or spreading COVID-19 over receiving necessary emergency care. Future work should focus on the resurgence of diagnoses, especially those exacerbated by deferred care, and on closing the gap for patients who are afraid or unable to visit the ED.

Meetings

None.

Grant or other financial support

None.

Competing interests

None.

References

- 1.Hartnett K.P., et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on emergency department visits — United States, January 1, 2019–May 30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(23):699–704. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6923e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Birkmeyer J.D., Barnato A., Birkmeyer N., Bessler R., Skinner J. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on hospital admissions in the United States. Health Aff (Millwood) Sep. 2020 doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jeffery M.M., et al. Trends in emergency department visits and hospital admissions in health care systems in 5 states in the first months of the COVID-19 pandemic in the US. JAMA Intern Med. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.3288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baum A., Schwartz M.D. Admissions to veterans affairs hospitals for emergency conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA. Jun. 2020;324(1):96–99. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.9972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Westgard B.C., Morgan M.W., Vazquez-Benitez G., Erickson L.O., Zwank M.D. An analysis of changes in emergency department visits after a state declaration during the time of COVID-19. Ann Emerg Med. 2020;76(5):595–601. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2020.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wong Laura E., Hawkins Jessica E., Langness Simone, Murrell Karen L., Iris Patricia, Sammann Amanda. Where are all the patients? Addressing covid-19 fear to encourage sick patients to seek emergency care. NEJM Catal. 2020:1–12. doi: 10.1056/CAT.20.0193. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim H.S., et al. Emergency department visits for serious diagnoses during the COVID-19 pandemic. Acad Emerg Med. Aug. 2020 doi: 10.1111/acem.14099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wosik J., et al. Telehealth transformation: COVID-19 and the rise of virtual care. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2020;27(6):957–962. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocaa067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Munir M.M., Martins R.S., Mian A.I. Emergency department admissions during COVID-19: Implications from the 2002–2004 sars epidemic. West J Emerg Med. 2020;21(4):744–745. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2020.5.48203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rubin R. COVID-19’s crushing effects on medical practices, some of which might not survive. JAMA. Jul. 2020;324(4):321–323. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.11254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Amidst COVID-19 Concerns, Emergency Physicians Urge Public Not to Delay Necessary Medical Care. https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/amidst-covid-19-concerns-emergency-physicians-urge-public-not-to-delay-necessary-medical-care-301041433.html

- 12.Impact of COVID-19 on Deferred Medical Costs and Future Pent-Up Demand. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simoons M.L., et al. Early thrombolysis in acute myocardial infarction: limitation of infarct size and improved survival. J Am Coll Cardiol. Apr. 1986;7(4):717–728. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(86)80329-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baum A., Barnett M.L., Wisnivesky J., Schwartz M.D. Association between a temporary reduction in access to health care and long-term changes in hypertension control among veterans after a natural disaster. JAMA Netw Open. Nov. 2019;2(11) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.15111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kishore N., et al. Mortality in Puerto Rico after hurricane Maria. N Engl J Med. Jul. 2018;379(2):162–170. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1803972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Solomon M.D., et al. The covid-19 pandemic and the incidence of acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(7):691–693. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2015630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nogueirai P.J., De Araújo Nobre M., Nicola P.J., Furtado C., Vaz Carneiro A. Excess mortality estimation during the COVID-19 pandemic: Preliminary data from Portugal. Acta Med Port. 2020;33(6):376–383. doi: 10.20344/amp.13928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baldi E., et al. Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest during the COVID-19 outbreak in Italy. N Engl J Med. Apr. 2020;383(5):496–498. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2010418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lerner E.B., Newgard C.D., Mann N.C. Effect of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic on the U.S. emergency medical services system: a preliminary report. Acad Emerg Med. Aug. 2020;27(8):693–699. doi: 10.1111/acem.14051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilder J.M. The disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on racial and ethnic minorities in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rimmer A. Covid-19: disproportionate impact on ethnic minority healthcare workers will be explored by government. BMJ. Apr. 2020;369:m1562. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Woolf S.H., Chapman D.A., Sabo R.T., Weinberger D.M., Hill L. Excess deaths from COVID-19 and other causes, march-April 2020. JAMA. Aug. 2020;324(5):510–513. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.11787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality . Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project; 2019. Clinical classifications software refined for ICD-10 diagnoses. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marmor Y.N., Rohleder T.R., Cook D.J., Huschka T.R., Thompson J.E. Recovery bed planning in cardiovascular surgery: a simulation case study. Health Care Manag Sci. Dec. 2013;16(4):314–327. doi: 10.1007/s10729-013-9231-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pines J.M. Mosby Inc.; Annals of Emergency Medicine: 2020. COVID-19, Medicare for all, and the uncertain future of emergency medicine. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Basu S., Phillips R.S., Phillips R., Peterson L.E., Landon B.E. Primary care practice finances in the United States amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Aff. Sep. 2020;39(9):1605–1614. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khullar D., Bond A.M., Schpero W.L. COVID-19 and the financial health of US hospitals. JAMA. Jun. 2020;323(21):2127–2128. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]