Graphical abstract

Keywords: Drug discovery, Drug repurposing, Computational methods, SARS-CoV-2, COVID-2019

Abstract

Background

Since the beginning of the novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) disease outbreak, there has been an increasing interest in finding a potential therapeutic agent for the disease. Considering the matter of time, the computational methods of drug repurposing offer the best chance of selecting one drug from a list of approved drugs for the life-threatening condition of COVID-19. The present systematic review aims to provide an overview of studies that have used computational methods for drug repurposing in COVID-19.

Methods

We undertook a systematic search in five databases and included original articles in English that applied computational methods for drug repurposing in COVID-19.

Results

Twenty-one original articles utilizing computational drug methods for COVID-19 drug repurposing were included in the systematic review. Regarding the quality of eligible studies, high-quality items including the use of two or more approved drug databases, analysis of molecular dynamic simulation, multi-target assessment, the use of crystal structure for the generation of the target sequence, and the use of AutoDock Vina combined with other docking tools occurred in about 52%, 38%, 24%, 48%, and 19% of included studies. Studies included repurposed drugs mainly against non-structural proteins of SARS-CoV2: the main 3C-like protease (Lopinavir, Ritonavir, Indinavir, Atazanavir, Nelfinavir, and Clocortolone), RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (Remdesivir and Ribavirin), and the papain-like protease (Mycophenolic acid, Telaprevir, Boceprevir, Grazoprevir, Darunavir, Chloroquine, and Formoterol). The review revealed the best-documented multi-target drugs repurposed by computational methods for COVID-19 therapy as follows: antiviral drugs commonly used to treat AIDS/HIV (Atazanavir, Efavirenz, and Dolutegravir Ritonavir, Raltegravir, and Darunavir, Lopinavir, Saquinavir, Nelfinavir, and Indinavir), HCV (Grazoprevir, Lomibuvir, Asunaprevir, Ribavirin, and Simeprevir), HBV (Entecavir), HSV (Penciclovir), CMV (Ganciclovir), and Ebola (Remdesivir), anticoagulant drug (Dabigatran), and an antifungal drug (Itraconazole).

Conclusions

The present systematic review provides a list of existing drugs that have the potential to influence SARS-CoV2 through different mechanisms of action. For the majority of these drugs, direct clinical evidence on their efficacy for the treatment of COVID-19 is lacking. Future clinical studies examining these drugs might come to conclude, which can be more useful to inhibit COVID-19 progression.

1. Introduction

The 21st century has allowed for coronaviruses to become well perfected and higher pathogenic to humans. In 2003 the world experienced severe acute respiratory syndrome of coronavirus (SARS-CoV) outbreak. It started from China and spread to five continents, with the calculated fatality rate of 9.6% during the outbreak period [1]. In 2012, the second outbreak of the Middle East respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus (MERS-CoV) occurred in the Arabian Peninsula, with the fatality rate of about 34.4% [2]. An outbreak of the novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) has emerged in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China, in December 2019. It is expanding at a remarkable pace so that on March 11th, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 as a pandemic [3]. As of writing this, there are more than one million people infected with, and more than 80,000 people died from COVID-19.

Having multiple routes of transmission and lack of full adherence to social distancing guidelines are important barriers making its prevention difficult [4], [5], [6], [7]. Also, despite widespread efforts, finding the origin, diagnosis, treatment, and management of COVID-19 has been a challenge for the health care system [8], [9], [10], [11]. Such efforts have so far occurred separately in different biomedical disciplines, particularly immunology, genetics, medical biotechnology, molecular engineering, nutrition, picotechnology, and regenerative medicine [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], highlighting the need for an integrated view of COVID-19 [33], [34], [35] aimed at doing science of high-quality [36]. With respect to the absence of specific treatment for COVID-19, we can provide only the combination of symptomatic treatment and supportive measures [37], [38], that for a significant proportion of cases, will not suffice. The fact is given as the disease can cause hyper inflammation affecting multiple systems and organs making it difficult to treat [26], [39], [40], [41], [42], [43], [44], [45].

The process of de novo drug design is hugely time-consuming. Drug repurposing, also known as drug repositioning or drug re-profiling, works as an alternate, systematic method in drug discovery that can aid in determining the new indications for the existing drugs. It is of high importance that this method repurposes drugs which their safety and pharmacokinetics have been recognized so far. Hence, it would confidently reduce the risk of adverse side effects, drug interactions, and drug development time and expenditure. The fastness of the computational or in silico techniques has made them an exciting approach to the drug repurposing world [46]. There are two main approaches to the computational drug repurposing process: target-based and disease-based [47]. The former allows the drug and the target to interact with each other leading to the establishment of drug-target interactions. The latter utilizes datasets to determine new indications for already approved drugs from comparisons of characteristics of diseases. Computational drug repurposing approaches differ from each other in some points, such as target modeling, algorithms, and the drug bank or data sets [48].

Since the beginning of the COVID-19 outbreak, there has been an increasing interest in finding a potential therapeutic agent for COVID-19. Considering the matter of time that this pandemic is not the time of trial and error [49] and also the possibility of re-infection [50], the computational methods of drug repurposing offer the best chance of selecting one drug from a list of approved drugs for the life-threatening condition of COVID-19. The present systematic review aims to provide an overview of studies that have used computational methods for COVID-19 drug repurposing.

2. Methods

We prepared this review according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) statement [51]. Before beginning the database search, the protocol of the present systematic review was developed and submitted to PROSPERO.

2.1. Search strategy

We undertook a systematic search in five databases, including PubMed, Scopus, Google Scholar, Cochrane, and the WHO global health library. The search terms and keywords included but not limited to the following terms for the disease; “Novel coronavirus”, “2019 nCoV”, “COVID-19″, ”Wuhan coronavirus“, ”Wuhan pneumonia“, ”SARS-CoV-2″, and for the drug repurposing; “Antiviral Agents”, “Drug Therapy”, “therapeutic use”, “therapeutic agents”, “Drug Repositioning”, “virtual screening”, “docking”, and “computational”. We imported search results into EndNote Version X9, Clarivate Analytics, USA.

2.2. Study selection

The present systematic review included original articles in English that applied computational methods for COVID-19drug repurposing. Eligible studies should repurpose drugs that are already approved by at least one of the following authorities: the European Medicines Agency (EMA), the Japan Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency (PMDA), or the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Studies that either investigated biologic agents (such as interleukins, vaccines, and miRNA), nutritional supplements, and traditional medicines or focused on protein structure prediction or determination rather than having a drug discovery project were not eligible to be included in this review. Also, studies examining a wet lab approach were excluded.

By considering the above criteria, two authors (K.M. and N.Y.) independently performed title/abstract screening and detailed review. In the case of disagreement, the two authors discussed the reasons to reach a consensus. When they were unable to reach a consensus, the third author (A.S.) was consulted.

2.3. Data extraction

The first two reviewers (K.M. and N.Y.) extracted the following data from each included publication: the first author, year of publication, country of origin, drug repurposing method, sequence alignment, target preparation, the resource for approved drugs, the visualization tool, molecular docking tool, coronavirus strain, target structures, candidate therapeutic agents, and the authors' conclusions. A consensus discussion between the two authors was made on items of discrepancies. The third author (A.S.) was involved in the points on which consensus did not happen.

2.4. Quality assessment

The idea of bias in computational drug research studies is not well established. However, few statements can aid in assessing bias systematically. Cleves et al. [4] argue about a bias that is produced by two dimensional (2D) descriptors in compound screening. The use of the method would reduce the probability of finding novel compounds. Also, Hert et al. [5] have introduced a bias that occurs when screening drug libraries, and therefore the result of screening would be restricted to the compounds with known biological effects. It is a threat to novelty, and a possible solution to this bias is the development of useful decoys (DUD), which use a standard set of ligands to make comparisons of different docking methods simultaneously [6]. Recently, Scannell et al. [7] have presented a bias that occurs when targeting a single molecule with a single compound and can be avoided with a multi-target approach. Eventually, it is crucial to point out the molecular flexibility of the targets. This point is usually missed out when one docking method is applied. The best way of putting this bias into account is to use the molecular dynamics simulations, a robust method with many functions that can predict the drug-target interaction in a better way. The most crucial function of molecular dynamics simulations is to provide multiple receptor conformations, in addition to many other sophisticated analyses that can accurately differentiate between a proper docking and an inadequate docking [52].

According to the potential issues of bias, a tool was designed for the assessment of five main aspects of quality of studies included in the present systematic review: design (mono-target vs. multi-target), target template modeling (crystal structure, homology modeling, and co-crystal ligand), docking tools, molecular dynamics simulation (yes vs. no), and the resource for approved drugs. The quality of each eligible article was independently appraised by two authors (K.M. and N.Y.) and then was double-checked by the third author (A.S.).

3. Results

3.1. Study selection

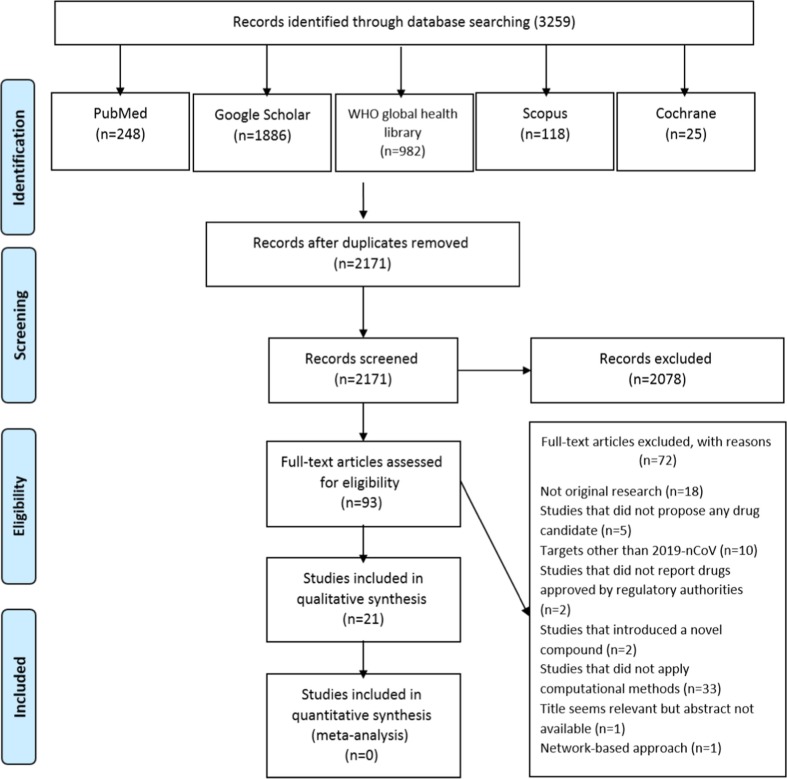

There were 3256 studies retrieved from the database search, of which 2171 papers remained after the removal of duplicates (Fig. 1 ). We conducted title and abstract screening on these 2171 studies and nominated 93 of them for detailed review. Considering the inclusion and exclusion criteria, we excluded 72 studies for different reasons as follows. There were studies not regarded as original research (n = 18) [53], [54], [55], [56], [57], [58], [59], [60], [61], [62], [63], [64], [65], [66], [67], [68], [69], [70], studies proposed a novel drug, an unapproved drug, or no drug at all (n = 9) [71], [72], [73], [74], [75], [76], [77], [78], [79], studies reporting drugs against targets other than the novel coronavirus (also known as 2019-nCoV or SARS-CoV2) (n = 10) [80], [81], [82], [83], [84], [85], [86], [87], [88], [89], studies applying any methods other than computational methods for drug repurposing (n = 33) [90], [91], [92], [93], [94], [95], [96], [97], [98], [99], [100], [101], [102], [103], [104], [105], [106], [107], [108], [109], [110], [111], [112], [113], [114], [115], [116], [117], [118], [119], [120], [121], [122], studies not published in full-text articles (n = 1) [123], and one study using network-based approach [124]. Finally, we included 21 original articles utilizing computational drug methods for COVID-19 drug repurposing [125], [126], [127], [128], [129], [130], [131], [132], [133], [134], [135], [136], [137], [138], [139], [140], [141], [142], [143], [144], [145].

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of the literature search process.

3.2. Study characteristics

As summarized in Table 1 , there were variations across studies in methods/techniques, software, targets, and modeling. AutoDock Vina (45.45%), the SWISS Model Web Server (41.9%), and PyMOL software (36.36%) were the most commonly used tools for docking, homology modeling, and visualization, respectively. Various targets were utilized in the computational drug repurposing approaches. Most of them were obtained from the RCSB Protein Bank Database and NCBI GenBank. Studies used the following components of the novel coronavirus as targets: main protease [146], endopeptidase, 3C-like protease (3CLP) [125], [127], [128], [129], [130], [133], [134], [135], [136], [137], [138], [139], [141], [142], [143], [144], [145], RNA dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) [127], [128], [131], [144], papain-like protease (PLP) [126], [132], [137], [144], helicase [127], [144], 3′-to-5′ exonuclease [127], 2′-O-ribose methyltransferase [127], [135], endoRNAse [127], and spike (S) protein [140], [144]. There was only one study combined with in vitro experiments [134].

Table 1.

|

|

|

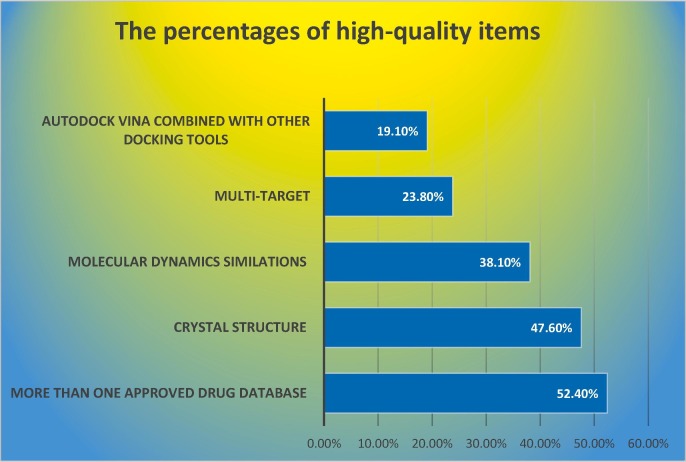

3.3. Study quality

Table 2 represents the details of the appraisal of study quality. Regarding the number of approved drug databases, more than 50% of studies used two or more databases. About 38% of the studies analyzed the molecular dynamics simulations. For the item target, more than 70% of studies investigated only one viral structure as the target. Also, more than 50% of the studies used homology modeling for the generation of the target sequence. AutoDock Vina was the only docking tool in more than 80% of studies. Fig. 2 displays the percentages of studies reporting high-quality items.

Table 2.

Quality of studies included in the systematic review.

|

Fig. 2.

The percentage of studies reported high-quality items.

3.4. Data synthesis

Conserved structures in the viral genome represent a high potential to be target candidates. While the phylogenetic tree inevitably undergoes evolutionary changes, a highly conserved structure can maintain its sequence among strains. Targeting such a highly conserved site will provide cross-reactive protection in different strains. Highly conserved elements of the 2019-nCoV (SARS-CoV2) include non-structural proteins such as 3CLP, RdRp, and PLP, and structural proteins, such as the S protein [78], [124]. Below is a target-based synthesis of data for COVID-19 drug repurposing as summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

The main findings of studies included in the systematic review.

| The first author, year | Findings |

|---|---|

| Sekhar 2020 |

|

| Elfiky 2020 |

|

| Alamri 2020 |

|

| Chang 2020 |

|

| Arya 2020 |

|

| Beck 2020 |

|

| Chen 2020 |

|

| Contini 2020 |

|

| Elfiky 2020 |

|

| Hosseini 2020 |

|

| Jin 2020 |

|

| Khan 2020 |

|

| Li 2020 |

|

| Lin 2020 |

|

| Nguyen 2020 |

|

| Nguyen 2020 |

|

| Smith 2020 |

|

| Ton 2020 |

|

| Wang 2020 |

|

| Wu 2020 |

|

| Xu 2020 |

|

3.5. 3CLPa

The main protease of the 2019-nCoV, also known as 3CLP or the C30 endopeptidase, is a highly conserved element that shares 96.1% similarity with the main protease of SARS-CoV. This protease is a member of the coronavirus polyproteins. When translation takes place, it is the first one that is auto-cleaved from the polyprotein. Then, it, in turn, would mediate the cleavage of the other 11 non-structural proteins that are vital for viral replication and transcription. Thus, 3CLP might serve as a marvelous target for COVID-19 therapy [78].

Lopinavir and Ritonavir are the most documented candidate drugs that target 3CLP (Table 3 ). However, Wu et al. claimed that Lopinavir and Ritonavir have not an excellent binding score in docking compared to other drugs [144]. Moreover, Contini et al. developed molecular dynamics simulations, which are known to be more potent than docking in the prediction of the drug-target binding [147]. The authors showed that Ritonavir failed to form the interaction with the 3CLP [130]. The good binding energy and docking score for each one of Elbasvir, Simeprevir, Indinavir, and Atanzavir might nominate these drugs as candidates for the inhibition of 3CLP of SARS-CoV2. Interestingly, both Indinavir and Remdesivir might be effective against SARS-CoV2 infection due to their excellent docking scores and limited toxicity, as confirmed by Chang et al. [128]. Nelfinavir was also mentioned as one of the best drugs binding to the 3CLP. However, it appeared less efficient than Tegobuvir and Bictegravir when the affinity and the physical–chemical analysis parameters were calculated using SeeSAR [136], [145]. Nguyen et al. suggested an unusual inhibitor of 3CLP, Clocortolone, a medium-strength steroid that is used for dermatitis and has good binding scores making it a promising cleanser against SARS-CoV2 contaminated surfaces [139].

Table 3.

Multi-target drugs repurposed for COVID-19.

|

3.6. RdRp

Viral RdRp is an enzyme that accelerates the replication of RNA from a template RNA and shares around 97.08% of its sequence with SARS-CoV [131].

Among the drugs that target this protein, Remdesivir is a bold one which, by a triphosphate nucleotide, would act as an ATP-competitive inhibitor of RdRp and intervene with the viral RNA synthesis. Also, Remdesivir can bind to the human TMPRSS2, a protein that mediates the cleavage of the viral S protein and promotes the entry of SARS-CoV2 into the host cells [144]. Ribavirin is another drug reported in two studies to interact with RdRp. It appeared not to be a very effective drug compared to other drugs [128], [131].

3.7. PLPa

PLP plays a crucial part in the initiation of infection through its ability to antagonize interferon (IFN) activity and deubiquitinate viral and cellular proteins [148].

Eight different structures attached to SARS-CoV PLP comprise sequences that are at least 82.17% identical to that of SARS-CoV2 PLP [132]. Two studies mainly focused on PLP drug candidates. Elfiky et al. pointed out drugs against SARS (GRL-0667, GRL-0617, and Mycophenolic acid) and HCV NS3 (Telaprevir, Boceprevir, and Grazoprevir) that have acceptable binding energy for SARS-CoV2 PLP but lack an excellent binding score [132]. Lin et al. demonstrated conformational changes of PLP upon binding to Darunavir and suggested Darunavir as a competitive inhibitor of PLP [137]. Arya et al. also reported two drugs that affect the SARS-CoV2 PLP: Chloroquine, an anti-malarial agent, and Formoterol, a drug that mainly works as a bronchodilator [126].

4. Discussion

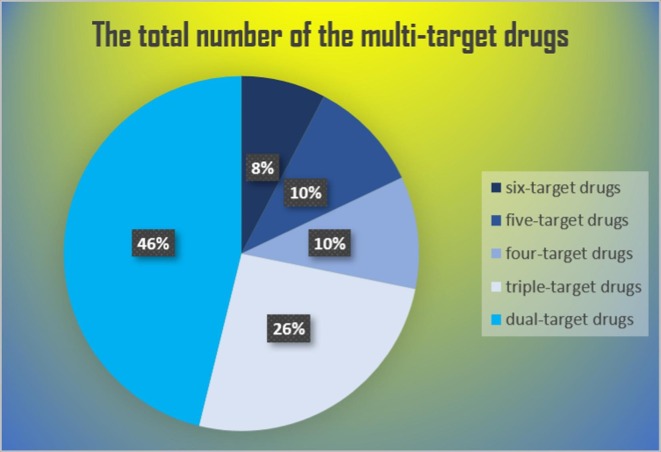

Multi-target therapeutic (Table 3 ) agents are more useful than mono-target drugs (Table 5 ) in terms of better predictive pharmacokinetics, better patient compliance, and reduced risk of drug interactions [149]. Simultaneously impacting different targets is, in particular, advantageous to approach individuals that express intrinsic or induced variability in drug response due to modifications in key disease-relevant biological pathways and activation of compensatory mechanisms [150], [151]. Below is a discussion of drugs repurposed for COVID-19 that target multiple viral elements (see Fig. 3 ).

Table 5.

Mono-target drugs repurposed for COVID-19.

|

Fig. 3.

The distribution of multi-target drugs for COVID-19.

This review revealed Atazanavir, Efavirenz, and Dolutegravir as the top-ranked drugs as arranged by the number of drugs. These drugs can similarly hit 3CLP, RdRp, helicase, 3′-to-5′ exonuclease, 2′-O-ribose methyltransferase, and endoRNAse proteins [127], [135]. Subsequently, each one of Ritonavir, Raltegravir, Darunavir, and Grazoprevir can target five viral replication proteins. Helicase, 3′-to-5′ exonuclease, and endoRNAse are common between them while Darunavir can exclusively target PLP and 3CLP, Grazoprevir can target PLP and RdRp, and both Ritonavir and Raltegravir are related to RdRp and 3CLP. Lopinavir Asunaprevir Lomibuvir and Boceprevir can target four viral replication proteins. Lopinavir and Asunaprevir commonly target 3CLP, helicase, and 3′-to-5′ exonuclease, while they exclusively target endoRNAse and RdRp, respectively. Lomibuvir and Boceprevir commonly target helicase and endoRNAse, while RdRp and 3′-to-5′ exonuclease are merely targeted by Lomibuvir and PLP and 2′-O-ribose methyltransferase are only targeted by Boceprevir.

It is worth mentioning that this category contains the highest number of repetitions among the multi-target drugs repurposed for COVID-19 therapy. Initially, each one of Entecavir, Penciclovir, and Ganciclovir similarly hit RdRp, helicase, and 3′-to-5′ exonuclease proteins. Danoprevir has the same targets as the drugs mentioned above, with an exception to helicase, which is replaced by endoRNAse. Moreover, Dabigatran, Itraconazole, and Saquinavir hit RdRp, helicase, and spike proteins; however, the later one hits 3CLP instead of the spike protein. Furthermore, Sempremivir and Nelfinavir commonly hit 3CLP and helicase, and distinctively hit each one of the 3′-to-5′ exonuclease and endoRNAse, respectively.

Indinavir and Remdesivir are the most documented drugs among dual-target drugs. These two drugs similarly target the 3CLP and desperately target each one of the helicase and RdRp, respectively. Also, Ribavirin is a drug with a dual effect; it targets RdRp and PLVP.

Smith et al. mentioned that Nitrofurantoin, Isoniazid pyruvate, Eriodictyol, are the top three candidates that bind to the ACE2 part of the ACE2 receptor-spike protein interface. Therefore, it might be expected that these drugs might restrict the binding of SARS-CoV2 spike protein to the ACE2 receptor and hence, inhibit the spread of infection [140]. However, this might be quite controversial if we consider what Wu et al. have declared about the inability of these drugs to block the viral infection and their restricted effect on the ACE2 Enzyme activity [144].

Chloroquine is another doubtful drug. Three studies have suggested that this drug might inhibit the PLP and the E-channel [126], [133], [144]. In all of these studies, the binding energy of Chloroquine is acceptable, but it lacks an excellent value and as declared by Wu and colleagues who emphasize on not considering the drugs that do not have a specific target like Chloroquine [144].

Wu et al. [144] have claimed that they found probable druggable compounds through the docking process of their structural model of helicase. The authors predicted that anti-bacterial drugs (Lymecycline, Cefsulodine, and Rolitetracycline), anti-fungal drug Itraconazole, anti-human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV-1) drug Saquinavir, anti-coagulant drug Dabigatran, and diuretic drug Canrenoic acid could act as potential coronavirus helicase inhibitors with high mfScores. Beck et al. [127] have also applied helicase as the drug repurposing target. The five top potential inhibitors have turned out to be Simeprevir, Atazanavir, Grazoprevir, Asunaprevir, and Telaprevir; with Kd (nM): 23.34, 25.92, 26.28, and 28.20, respectively.

Drug-target interaction (DTI) prediction results of repurposing of approved drugs indicate a list of possible inhibitors of 3′ to 5′ exonuclease, and the four top candidates were Simeprevir, Efavirenz, Danoprevir, and Ganciclovir [127].

2′-O-MTase, methylates the ribose 2′-O position of the first and second nucleotide in viral mRNA structure to sequester it from the host immune system [135]. The reported docking results in two separate studies that have utilized 2′-OMTase as their target was different. These two studies were performed by applying two different methodologies. Khan et al. [135] have performed homology modeling, molecular docking, and molecular dynamics simulations and have reported Dolutegravir and Bictegravir as probable candidates against SARS-CoV2. While Beck et al. [127] have conducted molecule transformer-drug target Interaction (MT-DTI) and have introduced Atazanavir, Efavirenz, and Boceprevir as potential inhibitors of SARS-CoV2 2′-OMTase.

EndoRNAse is an enzyme that can cleave both single-stranded and double-stranded RNA. In all 21 included studies, only Beck et al. [127] have used endoRNAse as a target for computational drug repurposing and proposed a list of approved drugs as potential candidates among which the top-ranked ones are Efavirenze and Atazanavir.

The best-documented multi-target drugs repurposed by computational methods for COVID-19 therapy include antiviral drugs commonly used to treat AIDS/HIV (Atazanavir, Efavirenz, and Dolutegravir Ritonavir, Raltegravir, and Darunavir, Lopinavir, Saquinavir, Nelfinavir, and Indinavir), HCV (Grazoprevir, Lomibuvir, Asunaprevir, Ribavirin, and Simeprevir), HBV (Entecavir), HSV (Penciclovir), CMV (Ganciclovir), and Ebola (Remdesivir), anticoagulant drug (Dabigatran), and an antifungal drug (Itraconazole). For the majority of these drugs, direct clinical evidence on their efficacy for the treatment of COVID-19 is lacking. There is, however, evidence from in vitro and clinical studies for the use of some drugs mentioned above in SARS-CoV2.

Atazanavir (ATV) is an antiretroviral protease inhibitor primarily introduced for the treatment of HIV. When it is administered intravenously, it can reach the lungs and help to cure pulmonary fibrosis. An in vitro study has shown that ATZ lessens SARS-CoV2 replication in both Vero cells and human epithelial pulmonary cells (A549). ATZ can particularly attenuate the unwanted inflammatory response to SARS-CoV2 in infected monocytes, as measured by the reduced levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL6 and TNFA [152].

In vitro studies indicate the anti-SARS activities of Lopinavir. Ritonavir is a potent inhibitor of cytochrome P450. When combined with Lopinavir, Ritonavir can help reduce cytochrome P450-mediated metabolism of Lopinavir in the liver that will increase plasma half-life of and biological effects of Lopinavir. As evidenced by a randomized controlled trial (RCT), no difference in clinical outcomes appeared following Lopinavir–Ritonavir treatment in adult patients with severe COVID-19 [153]. Moreover, patients receiving Lopinavir–Ritonavir treatment developed gastrointestinal adverse events more than those who underwent standard care.

An in vitro study [154] compared the safety and efficacy of nine HIV-1 protease inhibitors on SARS-CoV2 in VeroE6 cells. Amprenavir, darunavir, and indinavir could provide inhibition of SARS-CoV2 replication at a high 50% effective concentration (EC50) of 31.32, 46.41, and 59.14 μM. There was a lower dose required for Tipranavir to inhibit SARS-CoV2 replication. However, the selectivity index (SI) of Tipranavir was low. Ritonavir, Saquinavir, Atazanavir, Lopinavir, and Nelfinavir were the drugs that could at the lowest doses mitigate SARS-CoV2 replication while having a relatively high SI. They correspond to EC50 (SI) of 8.63 (8.59), 8.83 (5.03), 9.36 (>8.65), 5.73 (12.99), and 1.13 (21.52). Also, the Ctrough/EC50 ratio higher than one, which indicates that the compound can reach a trough serum concentration of higher than 50% effective concentration, occurred in only three of nine drugs Nelfinavir, Lopinavir, and Tipranavir. Overall, Nelfinavir seems to be the best among different anti-protease inhibitors, with both the lowest EC50 and the highest SI as well as the Ctrough/EC50 ratio higher than one.

Because of the absence of any effect of Darunavir on SARS-CoV cultured in Caco-2 cells, there is no SI attached to Darunavir [155]. By contrast, Remdesivir could reduce the cytopathogenic effect (CPE) of SARS-CoV at low doses (EC50 = 0.11 μM) and represent a noticeable SI higher than 900.

The study [156] evaluated the efficacy of seven drugs against SARS-CoV2 in Vero E6 cells. The 50% effective concentration at which the inhibitory effects of Ribavirin, Penciclovir, and Favipiravir on SARS-CoV2 replication appeared was as high as 109.5, 95.96, and 61.88 μM, respectively. It was reduced to 22.50 μM for Nafamostat and 2.12 for Nitazoxanide. Two drugs could have a powerful effect on SARS-CoV2 replication at low doses: Remdesivir and Chloroquine associated with EC50 (SI) of 0.77 (>129.87) and 1.13 (>88.5).

Like Chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine can have anti-malarial and immunomodulatory effects in a manner useful to patients with autoimmune diseases. Both Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine have shown to help antiviral immunity through inhibition of the fusion between viral and host-cell membranes, virus replication, and viral glycosylation and assembly. However, hydroxychloroquine has become more important for fewer adverse effects and drug-drug interactions. In vitro investigation points out a lower 50% effective concentration required for Chloroquine compared to hydroxychloroquine to exert anti-SARS-COv2 effects in Vero cells [157]. It would indicate the more potency of Chloroquine than its analog, hydroxychloroquine, in inhibiting SARS-CoV2 replication.

In conclusion, at this growing rate of COVID-19 pandemic and increasing mortality rate, it seems quite unachievable to design a novel specific drug for it. Therefore, it puts a spotlight on the drug repurposing system, and if we consider the matter of time, computational methods are our best shots. Since the incidence of this outbreak, many investigations have been conducted to present an appropriate therapeutic agent for COVID-19 utilizing computation drug repurposing approaches. Therefore, the review intended to cover all these studies to help build a concise framework for future research into COVID-19 therapy.

All methods have inherent limitations, and computational methods are not exceptional in this field. Thus, the use of models –which are illustrations of the real world- in running computational research, might be an inherent limitation. Besides, the results reported by docking score, binding energy, binding affinity, and other numerical variants were immensely divergent across twenty-one studies included in the review. Having the fact in mind that there is not any specific tool for quality assessment and comparison of computational repurposing methods; it would not be possible to evaluate the potential candidates from different studies to declare which is more significant.

5. Conclusion

Despite its limitations, the present systematic review provides a list of existing drugs that have the potential to influence SARS-CoV2 through different mechanisms of action. And in the near future, clinical studies examining these drugs might come to conclude, which can be more useful to inhibit COVID-19 progression.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Funding

There is no funding for the present study.

Authors' contributions

K.M. conceptualized the study. K.M. and N.Y. conducted database search, search results screening, detailed review, data extraction, quality assessment, and prepared the initial draft. A.S. prepared the final draft. N.R. supervised the project and critically appraised the manuscript.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

References

- 1.Organization WH. Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS).

- 2.Organization WH. Worldwide reduction in MERS cases and deaths since 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Hanaei S., Rezaei N. COVID-19: Developing from an outbreak to a pandemic. Arch. Med. Res. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2020.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lotfi M., Hamblin M.R., Rezaei N. COVID-19: Transmission, prevention, and potential therapeutic opportunities. Clinica Chimica Acta; Int. J. Clin. Chem. 2020;508:254–266. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2020.05.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.N. Samieefar, R. Yari Boroujeni, M. Jamee, M. Lotfi, M.R. Golabchi, A. Afshar, et al. Country Quarantine during COVID-19: Critical or Not? Disaster medicine and public health preparedness. 2020:1-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Rezaei N. COVID-19 affects healthy pediatricians more than pediatric patients. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2020;1 doi: 10.1017/ice.2020.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jabbari P., Jabbari F., Ebrahimi S., Rezaei N. COVID-19: A chimera of two pandemics. Disaster Med. Public Health Preparedness. 2020:1–2. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2020.223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sahu K.K., Siddiqui A.D., Rezaei N., Cerny J. Challenges for management of immune thrombocytopenia during COVID-19 pandemic. J. Med. Virol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jmv.26251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moazzami B., Razavi-Khorasani N., Dooghaie Moghadam A., Farokhi E., Rezaei N. COVID-19 and telemedicine: Immediate action required for maintaining healthcare providers well-being. J. Clin. Virology : the Official Publ. Pan Am. Soc. Clin. Virology. 2020;126 doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104345. 104345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Basiri A., Heidari A., Nadi M.F., Fallahy M.T.P., Nezamabadi S.S., Sedighi M. Microfluidic devices for detection of RNA viruses. Rev. Med. Virol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/rmv.2154. n/a(n/a):e2154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mohamed K., Rezaei N., Rodríguez-Román E., Rahmani F., Zhang H., Ivanovska M. International Efforts to Save Healthcare Personnel during COVID-19. Acta bio-medica : Atenei Parmensis. 2020;91(3) doi: 10.23750/abm.v91i3.9891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.H. Ahanchian, N. Moazzen, M.S.D. Faroughi, N. Khalighi, M. Khoshkhui, M.H. Aelami, et al., COVID-19 in a Child with Primary Specific Antibody Deficiency, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Rokni M., Hamblin M.R., Rezaei N. Cytokines and COVID-19: friends or foes? Hum. Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics. 2020,:1–3. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2020.1799669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ahanchian H., Moazzen N., Joghatayi S.H., Saeidinia A., Khoshkhui M., Aelami M.H. Death due to COVID-19 in an Infant with Combined Immunodeficiencies. Endocrine. 2020 doi: 10.2174/1871530320666201021142313. metabolic & immune disorders drug targets. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pourahmad R., Moazzami B., Rezaei N. Efficacy of plasmapheresis and immunoglobulin replacement therapy (IVIG) on patients with COVID-19. SN comprehensive. Clin. Med. 2020:1–5. doi: 10.1007/s42399-020-00438-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yazdanpanah F., Hamblin M.R., Rezaei N. The immune system and COVID-19: Friend or foe? Life Sci. 2020;256 doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.117900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mansourabadi A.H., Sadeghalvad M., Mohammadi-Motlagh H.R., Rezaei N. The immune system as a target for therapy of SARS-CoV-2: A systematic review of the current immunotherapies for COVID-19. Life Sci. 2020;258 doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.118185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saghazadeh A., Rezaei N. Immune-epidemiological parameters of the novel coronavirus - a perspective. Expert Rev. Clin. Immunol. 2020;16(5):465–470. doi: 10.1080/1744666X.2020.1750954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pashaei M., Rezaei N. Immunotherapy for SARS-CoV-2: potential opportunities. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2020;1–5 doi: 10.1080/14712598.2020.1807933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mojtabavi H., Saghazadeh A., Rezaei N. Interleukin-6 and severe COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Cytokine Netw. 2020;31(2):44–49. doi: 10.1684/ecn.2020.0448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nasab M.G., Saghazadeh A., Rezaei N. SARS-CoV-2-A tough opponent for the immune system. Arch. Med. Res. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2020.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Seyedpour S., Khodaei B., Loghman A.H., Seyedpour N., Kisomi M.F., Balibegloo M. Targeted therapy strategies against SARS-CoV-2 cell entry mechanisms: A systematic review of in vitro and in vivo studies. J. Cell. Physiol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jcp.30032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rezaei N. COVID-19 and medical biotechnology. Avicenna J. Med. Biotechnol. 2020;12(3):139. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rabiee N., Rabiee M., Bagherzadeh M., Rezaei N. COVID-19 and picotechnology: Potential opportunities. Med. Hypotheses. 2020;144 doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2020.109917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Darbeheshti F., Rezaei N. Genetic predisposition models to COVID-19 infection. Med. Hypotheses. 2020;142 doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2020.109818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bahrami A., Vafapour M., Moazzami B., Rezaei N. Hyperinflammatory shock related to COVID-19 in a patient presenting with multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children: First case from Iran. J. Paediatr. Child Health. 2020 doi: 10.1111/jpc.15048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fathi N., Rezaei N. Lymphopenia in COVID-19: Therapeutic opportunities. Cell Biol. Int. 2020;44(9):1792–1797. doi: 10.1002/cbin.11403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jahanshahlu L., Rezaei N. Monoclonal antibody as a potential anti-COVID-19. Biomed. Pharmacotherapy = Biomedecine & pharmacotherapie. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2020.110337. 129:110337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shojaeefar E., Malih N., Rezaei N. The possible double-edged sword effects of vitamin D on COVID-19: A hypothesis. Cell Biol. Int. 2020 doi: 10.1002/cbin.11469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Basiri A., Pazhouhnia Z., Beheshtizadeh N., Hoseinpour M., Saghazadeh A., Rezaei N. Regenerative medicine in COVID-19 treatment: real opportunities and range of promises. Stem Cell Reviews and Reports. 2020,:1–13. doi: 10.1007/s12015-020-09994-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yousefzadegan S., Rezaei N. Case report: death due to COVID-19 in three brothers. Am. J. Tropical Med. Hygiene. 2020;102(6):1203–1204. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.20-0240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Babaha F., Rezaei N. Primary immunodeficiency diseases in COVID-19 pandemic: a predisposing or protective factor? Am. J. Med. Sci. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.amjms.2020.07.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Momtazmanesh S., Ochs H.D., Uddin L.Q., Perc M., Routes J.M., Vieira D.N. All together to Fight COVID-19. Am. J. Tropical Med. Hygiene. 2020;102(6):1181–1183. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.20-0281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mohamed K., Rodríguez-Román E., Rahmani F., Zhang H., Ivanovska M., Makka S.A. Borderless collaboration is needed for COVID-19-A disease that knows no borders. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2020:1–2. doi: 10.1017/ice.2020.162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moradian N., Ochs H.D., Sedikies C., Hamblin M.R., Camargo C.A., Jr., Martinez J.A. The urgent need for integrated science to fight COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. J. Translational Med. 2020;18(1):205. doi: 10.1186/s12967-020-02364-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rzymski P., Nowicki M., Mullin G.E., Abraham A., Rodríguez-Román E., Petzold M.B. Quantity does not equal quality: scientific principles cannot be sacrificed. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2020;86 doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2020.106711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cascella M., Rajnik M., Cuomo A., Dulebohn S.C., Di Napoli R. Features, evaluation and treatment coronavirus (COVID-19). StatPearls [Internet] StatPearls Publishing. 2020 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saghazadeh A., Rezaei N. Towards treatment planning of COVID-19: Rationale and hypothesis for the use of multiple immunosuppressive agents: Anti-antibodies, immunoglobulins, and corticosteroids. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2020;84 doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2020.106560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yazdanpanah N., Saghazadeh A., Rezaei N. Anosmia: a missing link in the neuroimmunology of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Rev. Neurosci. 2020 doi: 10.1515/revneuro-2020-0039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jahanshahlu L., Rezaei N. Central nervous system involvement in COVID-19. Arch. Med. Res. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2020.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sadeghmousavi S., Rezaei N. COVID-19 and multiple sclerosis: predisposition and precautions in treatment. SN Compr. Clin. Med. 2020:1–6. doi: 10.1007/s42399-020-00504-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Goudarzi S., Dehghani Firouzabadi F., Dehghani Firouzabadi M., Rezaei N. Cutaneous lesions and COVID-19: Cystic painful lesion in a case with positive SARS-CoV-2. Dermatol. Ther. 2020 doi: 10.1111/dth.14266. e14266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saleki K., Banazadeh M., Saghazadeh A., Rezaei N. The involvement of the central nervous system in patients with COVID-19. Rev. Neurosci. 2020;31(4):453–456. doi: 10.1515/revneuro-2020-0026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lotfi M., Rezaei N. SARS-CoV-2: A comprehensive review from pathogenicity of the virus to clinical consequences. J. Med. Virol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jmv.26123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sarzaeim M., Rezaei N. Kawasaki disease and multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children with COVID-19. SN Compr. Clin. Med. 2020:1–6. doi: 10.1007/s42399-020-00558-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shim J.S., Liu J.O. Recent advances in drug repositioning for the discovery of new anticancer drugs. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2014;10(7):654–663. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.9224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sanseau P., Koehler J. Oxford University Press; 2011. Computational methods for drug repurposing. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pushpakom S., Iorio F., Eyers P.A., Escott K.J., Hopper S., Wells A. Drug repurposing: progress, challenges and recommendations. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2019;18(1):41–58. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2018.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mohamed K., Rezaei N. COVID-19 pandemic is not the time of trial and error. Am. J. Emergency Med. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2020.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.P. Jabbari, N. Rezaei, With Risk of Reinfection, Is COVID-19 Here to Stay? Disaster medicine and public health preparedness, 2020, 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Moher D., Shamseer L., Clarke M., Ghersi D., Liberati A., Petticrew M. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Systematic Rev. 2015;4(1):1. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Aminpour M., Montemagno C., Tuszynski J.A. An overview of molecular modeling for drug discovery with specific illustrative examples of applications. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland) 2019;24(9) doi: 10.3390/molecules24091693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Artificial intelligence finds drugs that could fight the new coronavirus. C&EN Global Enterprise. 2020;98(6):3.

- 54.Lim J., Jeon S., Shin H.Y., Kim M.J., Seong Y.M., Lee W.J. The author's response: case of the index patient who caused tertiary transmission of coronavirus disease 2019 in Korea: the application of lopinavir/ritonavir for the treatment of COVID-19 pneumonia monitored by quantitative RT-PCR. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2020 doi: 10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e89. 35(7):e89-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Richardson P., Griffin I., Tucker C., Smith D., Oechsle O., Phelan A. Baricitinib as potential treatment for 2019-nCoV acute respiratory disease. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):e30–e31. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30304-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lim J., Jeon S., Shin H.Y., Kim M.J., Seong Y.M., Lee W.J. Case of the index patient who caused tertiary transmission of COVID-19 infection in Korea: the application of lopinavir/ritonavir for the treatment of COVID-19 infected pneumonia monitored by quantitative RT-PCR. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2020 doi: 10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e79. 35(6):e79-e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wu W., Yang G., Zeng X., Wu S., Zhou B. Clinical research progress of antiviral drugs for the novel coronavirus pneumonia. Chin. J. Exp. Clin. Virology. 2020 34(0):E001-E. [Google Scholar]

- 58.J. Stebbing, A. Phelan, I. Griffin, C. Tucker, O. Oechsle, D. Smith, et al., COVID-19: combining antiviral and anti-inflammatory treatments. The Lancet Infect. Dis. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 59.Graham F. Daily briefing: The potential for repurposing existing drugs to fight COVID-19 coronavirus. Nature. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yasri S., Wiwanitkit V. Dose prediction of lopinavir/ritonavir for 2019-novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) infection based on mathematic modeling. Asian Pacific J. Tropical Med. 2020;13(3):137. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Klein A. Drug trials under way. New Sci. 2020;245(3270):6. doi: 10.1016/S0262-4079(20)30376-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kim J.Y. Letter to the editor: case of the index patient who caused tertiary transmission of coronavirus disease 2019 in Korea: the application of lopinavir/ritonavir for the treatment of COVID-19 pneumonia monitored by quantitative RT-PCR. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2019;35(7) doi: 10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Guo D. Old weapon for new enemy: drug repurposing for treatment of newly emerging viral diseases. Virol. Sin. 2020:1–3. doi: 10.1007/s12250-020-00204-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jiang H., Deng H., Wang Y.U., Liu Z., Sun M., Zhou P. The possibility of using Lopinave/Litonawe (LPV/r) as treatment for novel coronavirus (2019-nCov)pneumonia: a quick systematic review based on earlier coronavirus clinical studies. Chin. J. Emergency Med. 2020;29(2):182–186. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Liu X., Wang X.-J. Potential inhibitors against 2019-nCoV coronavirus M protease from clinically approved medicines. J. Genetics Genomics. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jgg.2020.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.X. Xu, Z. Dang, Promising Inhibitor for 2019-nCoV in Drug Development, 2020.

- 67.Wang M., Cao R., Zhang L., Yang X., Liu J., Xu M. Remdesivir and chloroquine effectively inhibit the recently emerged novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in vitro. Cell Res. 2020;1–3 doi: 10.1038/s41422-020-0282-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yao T.-T., Qian J.-D., Zhu W.-Y., Wang Y., Wang G.-Q. A systematic review of lopinavir therapy for SARS coronavirus and MERS coronavirus–a possible reference for coronavirus disease-19 treatment option. J. Med. Virol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jmv.25729. n/a(n/a) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.C. Chen, F. Qi, K. Shi, Y. Li, J. Li, Y. Chen, et al., Thalidomide combined with low-dose glucocorticoid in the treatment of COVID-19 pneumonia, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 70.Li G., De Clercq E. Nature Publishing Group; 2020. Therapeutic options for the 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Y. Quan, F. Liang, J. Xiong. aCODE: Agile Discovery of Drugs and Natural Products for Emerging Epidemic 2019-ncov based on Computational Pharmacology.

- 72.Zhang L., Lin D., Kusov Y., Nian Y., Ma Q., Wang J. Alpha-ketoamides as broad-spectrum inhibitors of coronavirus and enterovirus replication Structure-based design, synthesis, and activity assessment. J. Med. Chem. 2020 doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b01828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Y. Shi, X. Zhang, K. Mu, C. Peng, Z. Zhu, X. Wang, et al., D3Targets-2019-nCoV: A web server to identify potential targets for antivirals against 2019-nCoV, 2020.

- 74.S. Kumar, Drug and vaccine design against Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) spike protein through Computational approach, 2020.

- 75.Han D.P., Penn-Nicholson A., Cho M.W. Identification of critical determinants on ACE2 for SARS-CoV entry and development of a potent entry inhibitor. Virology. 2006;350(1):15–25. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.01.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Z. Haider, M.M. Subhani, M.A. Farooq, M. Ishaq, M. Khalid, R.S.A. Khan, et al., In silico discovery of novel inhibitors against main protease (Mpro) of SARS-CoV-2 using pharmacophore and molecular docking based virtual screening from ZINC database, 2020.

- 77.M. Macchiagodena, M. Pagliai, P. Procacci, Inhibition of the main protease 3CL-pro of the coronavirus disease 19 via structure-based ligand design and molecular modeling. arXiv preprint arXiv:200209937, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 78.A. Zhavoronkov, V. Aladinskiy, A. Zhebrak, B. Zagribelnyy, V. Terentiev, D.S. Bezrukov, et al., Potential COVID-2019 3C-like protease inhibitors designed using generative deep learning approaches, 2020.

- 79.Veljkovic V., Vergara-Alert J., Segalés J., Paessler S. Use of the informational spectrum methodology for rapid biological analysis of the novel coronavirus 2019-nCoV: prediction of potential receptor, natural reservoir, tropism and therapeutic/vaccine target. F1000Res. 2020 doi: 10.12688/f1000research.22149.1. 9(52):52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bari H.M., Awan A.A. Designing inhibitors for the SARS CoV main protease as anti-SARS drugs. McGill J. Med. 2004;8(1):96–97. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Blanchard J.E., Elowe N.H., Huitema C., Fortin P.D., Cechetto J.D., Eltis L.D. High-throughput screening identifies inhibitors of the SARS coronavirus main proteinase. Chem. Biol. 2004;11(10):1445–1453. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2004.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.de Wit E., Feldmann F., Cronin J., Jordan R., Okumura A., Thomas T. Prophylactic and therapeutic remdesivir (GS-5734) treatment in the rhesus macaque model of MERS-CoV infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2020;201922083 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1922083117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Du L., He Y., Zhou Y., Liu S., Zheng B.J., Jiang S. The spike protein of SARS-CoV - A target for vaccine and therapeutic development. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2009;7(3):226–236. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.S. Ekins, T.R. Lane, P.B. Madrid, Tilorone: A broad-spectrum antiviral invented in the USA and commercialized in Russia and beyond, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 85.Gordon C.J., Tchesnokov E.P., Feng J.Y., Porter D.P., Gotte M. The antiviral compound remdesivir potently inhibits RNA-dependent RNA polymerase from Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. J. Biol. Chem. 2020 doi: 10.1074/jbc.AC120.013056. jbc. AC120. 013056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lin S.-M., Lin S.-C., Hsu J.-N., Chang C-k, Chien C.-M., Wang Y.-S. Structure-based stabilization of non-native protein-protein interactions of coronavirus nucleocapsid proteins in antiviral drug design. J. Med. Chem. 2020 doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b01913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Vincent M.J., Bergeron E., Benjannet S., Erickson B.R., Rollin P.E., Ksiazek T.G. Chloroquine is a potent inhibitor of SARS coronavirus infection and spread. Virol. J. 2005;2(1):69. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-2-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Yamamoto N., Yang R., Yoshinaka Y., Amari S., Nakano T., Cinatl J. HIV protease inhibitor nelfinavir inhibits replication of SARS-associated coronavirus. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004;318(3):719–725. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.04.083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Yang Y., Deng Y., Wen B., Wang H., Meng X., Lan J. The amino acids 736–761 of the MERS-CoV spike protein induce neutralizing antibodies: Implications for the development of vaccines and antiviral agents. Viral Immunol. 2014;27(10):543–550. doi: 10.1089/vim.2014.0080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Agostini M.L., Andres E.L., Sims A.C., Graham R.L., Sheahan T.P., Lu X. Coronavirus susceptibility to the antiviral remdesivir (GS-5734) is mediated by the viral polymerase and the proofreading exoribonuclease. mBio. 2018;9(2):e00221–e318. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00221-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Andersen P.I., Ianevski A., Lysvand H., Vitkauskiene A., Oksenych V., Bjørås M. Discovery and development of safe-in-man broad-spectrum antiviral agents. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Bugert J., Hucke F., Zanetta P., Bassetto M., Brancale A. Antivirals in medical biodefense. Virus Genes. 2020:1–18. doi: 10.1007/s11262-020-01737-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Chen J., Ling Y., Xi X., Liu P., Li F., Li T. Efficacies of lopinavir/ritonavir and abidol in the treatment of novel coronavirus pneumonia. Chin. J. Infect. Dis. 2020 38(0):E008-E. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Colson P., Rolain J.-M., Raoult D. Chloroquine for the 2019 novel coronavirus. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Gao J., Tian Z., Yang X. Breakthrough: Chloroquine phosphate has shown apparent efficacy in treatment of COVID-19 associated pneumonia in clinical studies. Biosci. Trends. 2020 doi: 10.5582/bst.2020.01047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Gao W.Z., Yisi L., Dongdong T., Cheng W., Sa W., Jing C. Potential benefits of precise corticosteroids therapy for severe 2019-nCoV pneumonia. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy. 2020;5(1):1–3. doi: 10.1038/s41392-020-0127-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Jiang H., Wang Y., Wang K., Yang X., Zhang J., Deng H. A combination regimen by lopinave/litonawe (LPV/r), emtricitabine and tenofovir alafenamide fumarate (FTC/TAF) for treatment of novel coronavirus pneumonia (TARCoV) Chin. J. Emerg. Med. 2020 29(3):E006-E. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ju J., Kumar S., Li X., Jockusch S., Russo J.J. Nucleotide analogues as inhibitors of viral polymerases. bioRxiv. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 99.M. Karamanoglu, A Short Note on Potential 2019-ncov Treatment, 2020.

- 100.Kruse R.L. Therapeutic strategies in an outbreak scenario to treat the novel coronavirus originating in Wuhan, China [version 2; peer review: 2 approved] F1000Res. 2020;9 doi: 10.12688/f1000research.22211.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Sharifkashani S., Bafrani M.A., Khaboushan A.S., Pirzadeh M., Kheirandish A., Yavarpour Bali H. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor and SARS-CoV-2: Potential therapeutic targeting. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2020;884 doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2020.173455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Lu H. Drug treatment options for the 2019-new coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Biosci. Trends. 2020 doi: 10.5582/bst.2020.01020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.multicenter collaboration group of Department of S, Technology of Guangdong P, Health Commission of Guangdong Province for chloroquine in the treatment of novel coronavirus p. Expert consensus on chloroquine phosphate for the treatment of novel coronavirus pneumonia. Zhonghua Jie He He Hu Xi Za Zhi. 2020;43(0):E019-E. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 104.Nct. Severe 2019-nCoV Remdesivir RCT. https://clinicaltrialsgov/show/NCT04257656. 2020.

- 105.Nct. Mild/Moderate 2019-nCoV Remdesivir RCT. https://clinicaltrialsgov/show/NCT04252664. 2020.

- 106.Nct. Glucocorticoid Therapy for Novel CoronavirusCritically Ill Patients With Severe Acute Respiratory Failure. https://clinicaltrialsgov/show/NCT04244591. 2020.

- 107.Nct. A Randomized Multicenter Controlled Clinical Trial of Arbidol in Patients With 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV). https://clinicaltrialsgov/show/NCT04246242. 2020.

- 108.Nct. Efficacy and Safety of Hydroxychloroquine for Treatment of Pneumonia Caused by 2019-nCoV (HC-nCoV). https://clinicaltrialsgov/show/NCT04261517. 2020.

- 109.Nct. Efficacy and Safety of Darunavir and Cobicistat for Treatment of Pneumonia Caused by 2019-nCoV. https://clinicaltrialsgov/show/NCT04252274. 2020.

- 110.Nct. Evaluating and Comparing the Safety and Efficiency of ASC09/Ritonavir and Lopinavir/Ritonavir for Novel Coronavirus Infection. https://clinicaltrialsgov/show/NCT04261907. 2020.

- 111.Nct. A Prospective,Randomized Controlled Clinical Study of Antiviral Therapy in the 2019-nCoV Pneumonia. https://clinicaltrialsgov/show/NCT04255017. 2020.

- 112.Nct. A Randomized,Open,Controlled Clinical Study to Evaluate the Efficacy of ASC09F and Ritonavir for 2019-nCoV Pneumonia. https://clinicaltrialsgov/show/NCT04261270. 2020.

- 113.Nct. The Efficacy of Lopinavir Plus Ritonavir and Arbidol Against Novel Coronavirus Infection. https://clinicaltrialsgov/show/NCT04252885. 2020.

- 114.Nowak J.K., Walkowiak J. Is lithium a potential treatment for the novel Wuhan (2019-nCoV) coronavirus? A scoping review. F1000Res. 2020;9(93):93. [Google Scholar]

- 115.Russell C.D., Millar J.E., Baillie J.K. Clinical evidence does not support corticosteroid treatment for 2019-nCoV lung injury. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):473–475. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30317-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Shang L., Zhao J., Hu Y., Du R., Cao B. On the use of corticosteroids for 2019-nCoV pneumonia. The Lancet. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30361-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Sun M.L., Yang J.M., Sun Y.P., Su G.H. Inhibitors of RAS might be a good choice for the therapy of COVID-19 pneumonia. Zhonghua Jie He He Hu Xi Za Zhi. 2020 doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1001-0939.2020.0014. 43(0):E014-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Totura A.L., Bavari S. Broad-spectrum coronavirus antiviral drug discovery. Expert. Opin. Drug Discov. 2019;14(4):397–412. doi: 10.1080/17460441.2019.1581171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.K. Xu, Y. Chen, J. Yuan, P. Yi, C. Ding, W. Wu, et al. Clinical Efficacy of Arbidol in Patients with 2019 Novel Coronavirus-Infected Pneumonia: A Retrospective Cohort Study, 2020.

- 120.J. Zhang, X. Ma, F. Yu, J. Liu, F. Zou, T. Pan, et al. Teicoplanin potently blocks the cell entry of 2019-nCoV, bioRxiv, 2020.

- 121.Zhao J.P., Hu Y., Du R.H., Chen Z.S., Jin Y., Zhou M. Expert consensus on the use of corticosteroid in patients with 2019-nCoV pneumonia. Zhonghua Jie He He Hu Xi Za Zhi. 2020 doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1001-0939.2020.0007. 43(0):E007-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Zhou W., Liu Y., Tian D., Wang C., Wang S., Cheng J. Potential benefits of precise corticosteroids therapy for severe 2019-nCoV pneumonia. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy. 2020;5(1):1–3. doi: 10.1038/s41392-020-0127-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.A. Elfiky, Sofosbuvir Can Inhibit the Newly Emerged Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in Wuhan, China, China (1/20/2020), 2020.

- 124.Zhou Y., Hou Y., Shen J., Huang Y., Martin W., Cheng F. Network-based drug repurposing for human coronavirus. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41421-020-0153-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.M.A. Alamri, M.T. ul Qamar, S.M. Alqahtani, Pharmacoinformatics and molecular dynamic simulation studies reveal potential inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 main protease 3CLpro, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 126.R. Arya, A. Das, V. Prashar, M. Kumar, Potential inhibitors against papain-like protease of novel coronavirus (COVID-19) from FDA approved drugs, 2020.

- 127.Beck B.R., Shin B., Choi Y., Park S., Kang K. Predicting commercially available antiviral drugs that may act on the novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV), Wuhan, China through a drug-target interaction deep learning model. bioRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.csbj.2020.03.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Y.-C. Chang, Y.-A. Tung, K.-H. Lee, T.-F. Chen, Y.-C. Hsiao, H.-C. Chang, et al., Potential therapeutic agents for COVID-19 based on the analysis of protease and RNA polymerase docking, 2020.

- 129.Y.W. Chen, C.-P.B. Yiu, K.-Y. Wong, Prediction of the SARS-CoV-2 (2019-nCoV) 3C-like protease (3CL pro) structure: virtual screening reveals velpatasvir, ledipasvir, and other drug repurposing candidates, F1000Res, 2020;9(129):129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 130.A. Contini, Virtual screening of an FDA approved drugs database on two COVID-19 coronavirus proteins, 2020.

- 131.Elfiky A.A. Anti-HCV, nucleotide inhibitors, repurposing against COVID-19. Life Sci. 2020;117477 doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.117477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.A.A. Elfiky, N.S. Ibrahim, Anti-SARS and Anti-HCV Drugs Repurposing Against the Papain-like Protease of the Newly Emerged Coronavirus (2019-nCoV), 2020.

- 133.F.S. Hosseini, M. Amanlou, Simeprevir, Potential Candidate to Repurpose for Coronavirus Infection: Virtual Screening and Molecular Docking Study, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 134.Jin Z., Du X., Xu Y., Deng Y., Liu M., Zhao Y. Structure-based drug design, virtual screening and high-throughput screening rapidly identify antiviral leads targeting COVID-19. bioRxiv. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 135.R.J. Khan, R.K. Jha, G.M. Amera, M. Jain, E. Singh, A. Pathak, et al. Targeting novel coronavirus 2019: A systematic drug repurposing approach to identify promising inhibitors against 3C-like proteinase and 2'-O-ribose methyltransferase, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 136.Li Y., Zhang J., Wang N., Li H., Shi Y., Guo G. Therapeutic drugs targeting 2019-nCoV main protease by high-throughput screening. bioRxiv. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 137.Lin S., Shen R., He J., Li X., Guo X. Molecular modeling evaluation of the binding effect of ritonavir, lopinavir and darunavir to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 proteases. bioRxiv. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 138.D. Nguyen, K. Gao, J. Chen, R. Wang, G. Wei, Potentially highly potent drugs for 2019-nCoV, bioRxiv, 2020.

- 139.D.D. Nguyen, K. Gao, R. Wang, G. Wei, Machine intelligence design of 2019-nCoV drugs, bioRxiv, 2020.

- 140.M. Smith, J.C. Smith, Repurposing Therapeutics for the Wuhan Coronavirus nCov-2019: Supercomputer-Based Docking to the Viral S Protein and Human ACE2 Interface, 2020.

- 141.S. Talluri, Virtual High Throughput Screening Based Prediction of Potential Drugs for COVID-19, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 142.A.-T. Ton, F. Gentile, M. Hsing, F. Ban, A. Cherkasov, Rapid identification of potential inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 main protease by deep docking of 1.3 billion compounds, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 143.J. Wang, Fast identification of possible drug treatment of coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19) through computational drug repurposing study, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 144.Wu C., Liu Y., Yang Y., Zhang P., Zhong W., Wang Y. Analysis of therapeutic targets for SARS-CoV-2 and discovery of potential drugs by computational methods. Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica B. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2020.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Xu Z., Peng C., Shi Y., Zhu Z., Mu K., Wang X. Nelfinavir was predicted to be a potential inhibitor of 2019-nCov main protease by an integrative approach combining homology modelling, molecular docking and binding free energy calculation. bioRxiv. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 146.D. Fasting, W.Y.N.T. Know, D. Right, S.E.T.D. Learning, S.I. Memory, B.T.T.P.D. From, et al. How to Live Better, Longer.

- 147.Liu X., Shi D., Zhou S., Liu H., Liu H., Yao X. Molecular dynamics simulations and novel drug discovery. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 2018;13(1):23–37. doi: 10.1080/17460441.2018.1403419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Niemeyer D., Mosbauer K., Klein E.M., Sieberg A., Mettelman R.C., Mielech A.M. The papain-like protease determines a virulence trait that varies among members of the SARS-coronavirus species. PLoS Pathog. 2018;14(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Talevi A. Multi-target pharmacology: possibilities and limitations of the “skeleton key approach” from a medicinal chemist perspective. Front. Pharmacol. 2015;6:205. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2015.00205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Zimmermann G.R., Lehár J., Keith C.T. Multi-target therapeutics: when the whole is greater than the sum of the parts. Drug Discovery Today. 2007;12(1–2):34–42. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2006.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Xie L., Xie L., Kinnings S.L., Bourne P.E. Novel computational approaches to polypharmacology as a means to define responses to individual drugs. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2012;52:361–379. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010611-134630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Fintelman-Rodrigues N., Sacramento C.Q., Lima C.R., da Silva F.S., Ferreira A., Mattos M. Atazanavir inhibits SARS-CoV-2 replication and pro-inflammatory cytokine production. bioRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1128/AAC.00825-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Cao B., Wang Y., Wen D., Liu W., Wang J., Fan G. A trial of lopinavir–ritonavir in adults hospitalized with severe Covid-19. New Engl. J. Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Yamamoto N., Matsuyama S., Hoshino T., Yamamoto N. Nelfinavir inhibits replication of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 in vitro. bioRxiv. 2020;2020(04) 06.026476. [Google Scholar]

- 155.De Meyer S., Bojkova D., Cinati J., Van Damme E., Buyck C., Van Loock M. Lack of antiviral activity of darunavir against SARS-CoV-2. medRxiv. 2020;2020(04) doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.05.085. 03.20052548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Wang M., Cao R., Zhang L., Yang X., Liu J., Xu M. Remdesivir and chloroquine effectively inhibit the recently emerged novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in vitro. Cell Res. 2020;30(3):269–271. doi: 10.1038/s41422-020-0282-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Liu J., Cao R., Xu M., Wang X., Zhang H., Hu H. Hydroxychloroquine, a less toxic derivative of chloroquine, is effective in inhibiting SARS-CoV-2 infection in vitro. Cell Discovery. 2020;6(1):1–4. doi: 10.1038/s41421-020-0156-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Li J.-Y., You Z., Wang Q., Zhou Z.-J., Qiu Y., Luo R. The epidemic of 2019-novel-coronavirus (2019-nCoV) pneumonia and insights for emerging infectious diseases in the future. Microbes Infect. 2020;S1286–4579(20):30030–30037. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2020.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Li X., Liu M., Zhao Q., Liu R., Zhang H., Dong M. Preliminary Recommendations for Lung Surgery during 2019 Novel Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Epidemic Period. Zhongguo Fei Ai Za Zhi. 2020 doi: 10.3779/j.issn.1009-3419.2020.03.01. 23:10.3779/j.issn.1009-3419.2020.03.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Ralph R., Lew J., Zeng T., Francis M., Xue B., Roux M. 2019-nCoV (Wuhan virus), a novel Coronavirus: human-to-human transmission, travel-related cases, and vaccine readiness. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2020;14(1):3–17. doi: 10.3855/jidc.12425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Liu K., Fang Y.-Y., Deng Y., Liu W., Wang M.-F., Ma J.-P. Clinical characteristics of novel coronavirus cases in tertiary hospitals in Hubei Province. Chin. Med. J. (Engl.) 2020 doi: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000000744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]