Abstract

Social inequalities limit important opportunities and resources for members of marginalized and disadvantaged groups. Understanding the origins of how children construct their understanding of social inequalities in the context of their everyday peer interactions has the potential to yield novel insights into when – and how – individuals respond to different types of social inequalities. The present study examined whether children (N = 176; 3- to 8-years-old; 52% female, 48% male; 70% European American, 16% African American, 10% Latinx, and 4% Asian American; middle-income backgrounds) differentiate between structurally-based inequalities (e.g., based on gender) and individually-based inequalities (e.g., based on merit). Children were randomly assigned to a group that received more (advantaged) or fewer (disadvantaged) resources than another group due to either their groups’ meritorious performance on a task or the gender biases of the peer in charge of allocating resources. Overall, children evaluated structurally-based inequalities to be more unfair and worthy of rectification than individually-based inequalities, and disadvantaged children were more likely to view inequalities to be wrong and act to rectify them compared to advantaged children. With age, advantaged children became more likely to rectify the inequalities and judge perpetuating allocations to be unfair. Yet, the majority of children allocated equally in response to both types of inequality. The findings generated novel evidence regarding how children evaluate and respond to individually- and structurally-based inequalities, and how children’s own status within the inequality informs these responses.

Keywords: moral development, fairness, structural inequality, resource allocation

Social inequalities (i.e., differences in resources, opportunities, power, prestige, and/or status across groups within a social system) present a major barrier to the fair and equitable treatment of individuals within a society (Anderson, 1999; Duncan & Murnane, 2011; Reardon & Firebaugh, 2002; Wilkinson & Pickett, 2009). In order to address this pressing societal concern, it is important to understand the origins and development of the psychological processes that create, maintain, and perpetuate these inequalities (Brown, 2017; Ruck et al., 2019). Given that beliefs about social inequalities begin to emerge in early childhood (Elenbaas et al., 2020; Killen et al., 2018; Mandalaywala et al., 2020; Shutts et al., 2016), it is important to understand how children construct ideas about what it means to be advantaged or disadvantaged by an inequality and whether children distinguish between inequalities rooted in individual and structural factors. To examine this question, we presented children with familiar scenarios in which they were either advantaged or disadvantaged by an individually- or structurally-based inequality and assessed how they evaluated and responded to these inequality contexts.

Defining structurally- and individually-based inequalities

Critical to understanding how children evaluate inequalities is the recognition that not all inequalities are rooted in the same underlying factors and that not all individuals experience inequalities in the same way. Consistent with theorizing in feminist, critical race, and intersectional literatures (Crenshaw et al., 1995; Delgado & Stefancic, 2017; Haslanger, 2016; Hooks, 2000; Ridgeway, 2015; Roberts & Rizzo, 2020; Salter & Adams, 2013; Salter et al., 2017), we distinguish between “individually-based” inequalities (i.e., inequalities that arise from legitimate differences in individuals’ choices, ability, or effort) and “structurally-based” inequalities (i.e., inequalities that arise due to constraints within a social structure that systematically limit individuals’ access to resources and opportunities). Further, consistent with how social inequalities manifest in societies (e.g., gender and racial disparities) we operationalized “structurally-based” inequalities in the present study as inequalities that are intentionally created and/or maintained by high-status individuals and result in the creation, maintenance, or perpetuation of a status disparity.

Additionally, individuals occupy different positions within inequalities, with some people occupying higher-status positions (i.e., advantaged perspectives) and others occupying lower-status positions (i.e., disadvantaged perspectives). In the context of resource inequalities, we use the term “advantaged” to refer to individuals who hold or control more resources than others and the term “disadvantaged” to refer to individuals who hold or control fewer resources than others, though we acknowledge that advantaged and disadvantaged status can refer to a much broader range of factors with different implications and manifestations in other contexts.

Children’s perceptions of individually and structurally-based inequalities

Children’s beliefs about inequalities begin to emerge in the first few years of life. Young children develop an expectation that resources will be allocated equally and a preference for equal over unequal allocators (Sommerville & Ziv, 2018). Throughout childhood, children build on these expectations, forming a prescriptive understanding of fairness and a recognition of the distinction between equality and equity (Essler et al., 2020; Rizzo & Killen, 2016; Schmidt et al., 2016; Wörle & Paulus, 2018). In the context of preexisting inequalities, “equality” refers to distributing the same number of resources to all individuals regardless of the current distribution (which maintains the initial inequality) and “equity” refers to distributing more resources to individuals who currently have fewer (which rectifies the initial inequality).

Yet, beginning in early childhood, children also begin to recognize concerns for merit–the idea that individuals should be compensated according to their actions, abilities, or performance. For example, Baumard, Mascaro, and Chevallier (2011) presented children with a story about a hardworking and lazy character and asked them to distribute cookies between the two characters. They found that even 3- and 4-year-old children allocated a larger cookie—or a larger share of multiple cookies—to the hardworking character. Additional research has since expanded on these findings, revealing how children’s understanding of merit develops considerably during childhood, with 6- to 8-year-olds being increasingly likely to allocate resources meritoriously, judge merit-based allocations as fair, and verbally reason about the importance of ensuring fair compensation for effort and contribution (Schmidt et al., 2016; Rizzo et al., 2016). Thus, while children demonstrate a early recognition of the wrongfulness of inequalities, they also demonstrate an early concern for merit-based allocations, even when those allocations result in—individually-based—inequalities.

Structurally-based inequalities differ meaningfully from individually-based inequalities because they inherently disadvantage individuals based on their group memberships (e.g., gender, race, sexual orientation) rather than their actions, abilities, or competencies (Crenshaw et al., 1995; Haslanger, 2016; Ridgeway, 2015; Salter et al., 2017). By 3- to 5-years-old, children begin to form structural representations of social groups (Vasilyeva & Ayala, 2019) and view explicit instances of group-based discrimination as wrong and unfair (Killen et al., 2002). With age, children also begin to recognize the wrongfulness of gender and racial inequalities. For example, when presented with an inequality between racial ingroup and outgroup members, 5- to 6-year-old children rectify inequalities that disadvantage their racial ingroup members, and 10- to 11-year-olds rectify racial inequalities regardless of whether their racial ingroup or outgroup is disadvantaged (Elenbaas et al., 2016).

These separate bodies of research suggest that children do not develop a general aversion to inequalities, but rather consider the broader context and the reason for an inequality when determining how to respond. To directly examine children’s ability to distinguish between individually- and structurally-based inequalities, Rizzo, Elenbaas, and Vanderbilt (2018) presented children with inequality contexts that only differed by the underlying reason for the inequality (individual: based on performance on a task; structural: based on gender bias). They found that children as young as 3- to 5-years-old were more likely to rectify structurally-based inequalities and perpetuate individually-based inequalities and that by 6- to 8-years-old children were better able to recognize the systemic nature of the structural inequality. These results provide further evidence that children are capable of recognizing the difference between individually- and structurally-based inequalities. An important limitation of this work, however, was that children were not personally impacted by the inequality and thus had nothing to gain or lose by rectifying or perpetuating it. A pressing question is whether children will respond similarly to these inequalities when they are personally embedded within them.

Children’s perceptions of advantageous and disadvantageous inequalities

Despite early emerging concerns for equality, equity, and merit, children also actively create, maintain, and perpetuate inequalities that advantage themselves and their groups. Children advantage themselves and their ingroups for a variety of reasons including personal desire for resources, recognizing the legitimacy of merit-based allocations when they work hard (Kanngiesser & Warneken, 2012), and a lack of recognition about others’ intentions when others are more deserving (Li et al., 2017). In addition, group affiliation can heighten one’s motivation to advantage one’s own group as a way of demonstrating ingroup loyalty (Abrams & Rutland, 2008; Ruble et al., 2006; Spears-Brown & Bigler, 2005).

To examine how children’s status impacts their willingness to accept or reject inequalities, Blake and colleagues (2015) asked 4- to 15-year-old children to play a series of economic games that placed them into advantaged (received more resources than a peer) and disadvantaged (received fewer resources than a peer) positions within an inequality. No reason was provided for why one child received more than the other—the question was simply whether children would accept or reject the unequal allocations. They found that most children rejected disadvantageous inequalities by middle childhood, but did not reject advantageous inequalities until much later, and with significant cultural variation (also see Blake & McAuliffe, 2011; Sheskin et al., 2016; Shaw et al., 2016). Supporting these findings, McGuire and colleagues (2018a, 2018b) found that adolescents, but not children, rectified inequalities that disadvantaged their outgroup.

Why might children’s status impact their willingness to accept/reject inequalities? Recent findings in developmental and social psychology suggest that social status can lead to social-cognitive changes with implications for how individuals perceive social contexts and systems. For example, Kraus and colleagues (2010, 2012) documented that adults from high SES backgrounds perform worse at perspective taking and emotion understanding assessments compared to those from lower SES backgrounds. Similarly, Rizzo and Killen (2018) manipulated children’s social status via a resource allocation task (advantaged: receiving more resources, disadvantaged: receiving fewer resources). They found that children randomly assigned to the advantaged status performed worse on subsequent false-belief and belief-emotion theory of mind assessments compared to those assigned to the disadvantaged status. Research on social dominance orientation also suggests that advantaged individuals often fail to rectify inequalities because they perceive them to be justified (Pratto et al., 1994; but see Jost et al., 2004 for work on how members of disadvantaged groups also justify unjust systems in some contexts). Indeed, young children often assume that unexplained inequalities are often justified by individual/inherent factors (Hussak & Cimpian, 2014). Thus, there are likely several pathways by which status can impact one’s evaluations of inequalities beyond a simple desire for resources.

Present study

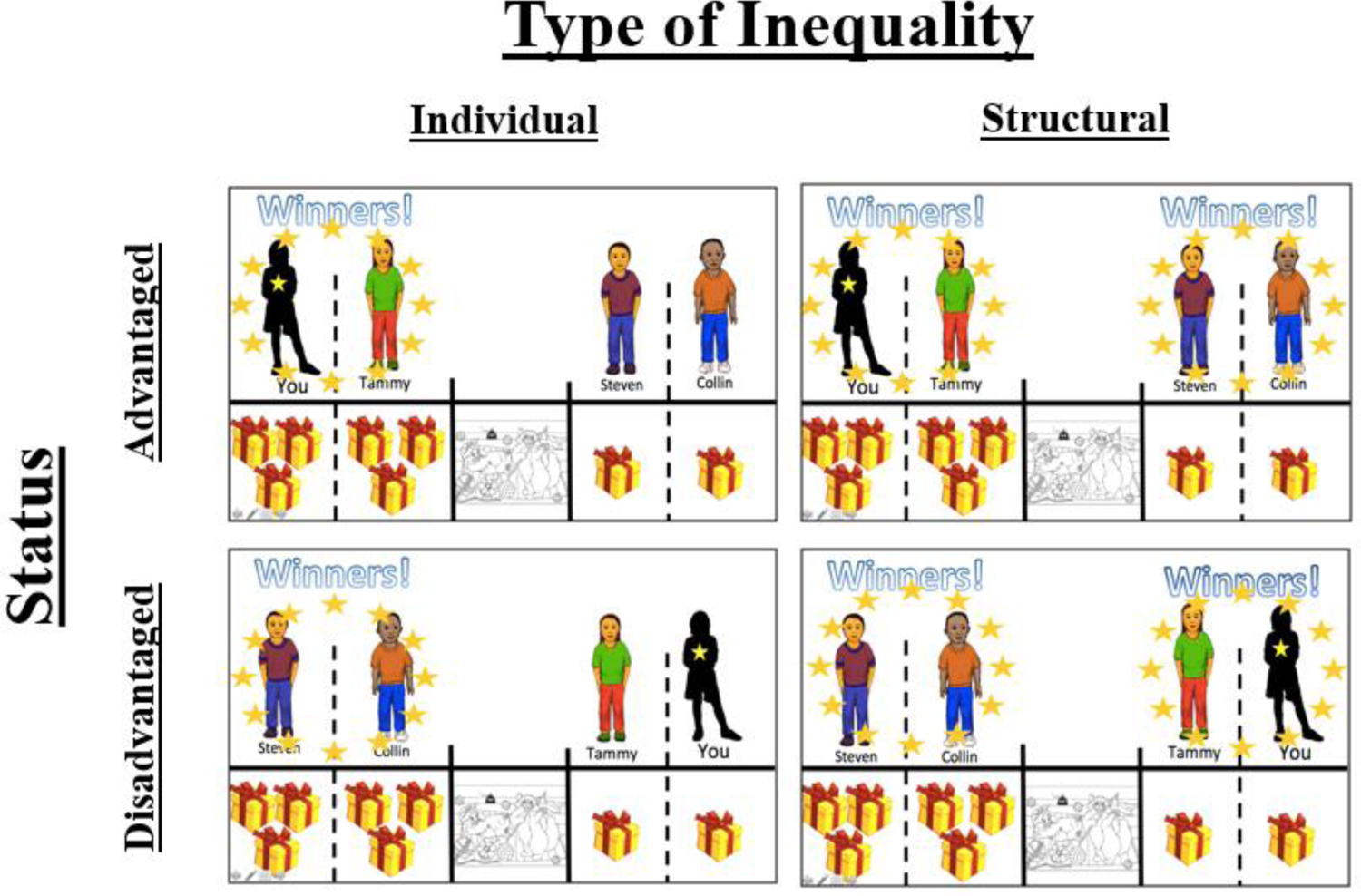

The goals of the present study were to examine how children’s evaluations of, and responses to, inequalities were related to (1) the type of inequality (individual, structural) and (2) their status (advantaged, disadvantaged) within the inequality. The present study thus utilized a 2 (Type of Inequality: Individual, Structural) by 2 (Status: Advantaged, Disadvantaged) between-subjects design, in which children were randomly assigned to one of four conditions, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Allocations for the four between-subject experimental conditions (female participant). The characters remained in stable locations on the screen throughout the task, and the prizes appeared beneath the characters in accordance with the allocations created.

We selected the contexts for these inequalities by identifying situations that were age-appropriate manifestations of individually- and structurally-based inequalities that children commonly experience in their daily lives. Children allocate resources meritoriously in peer contexts and experience differential allocations based on merit (Corsaro, 2017; Damon, 1977). Accordingly, we operationalized “individually-based” inequalities in the present study to be resource inequalities rooted in differences in meritorious performance across groups (e.g., when the individual in charge of allocating the resources gives more to the group that performed better on a task).

Gender is a well-documented structure within children’s daily lives; beginning early in development, children self-segregate into gender groups, share more with gender-ingroup peers, and hold differing expectations regarding gender roles and norms (see Bian, Leslie, & Cimpian, 2017; Conry-Murray, 2015, 2019; Liben & Bigler, 2002; Mulvey, 2015; Ruble et al., 2006). These gender norms are also reinforced by parents, teachers, and other adults (e.g., teachers expecting boys to perform better in STEM courses and gender differences in parental socialization practices). Accordingly, we operationalized “structurally-based” inequalities in the present study to be resource inequalities rooted in explicit social constraints that systematically limit individuals’ access to resources on the basis of gender group membership (e.g., when the individual in charge of allocating the resources preferences their gender ingroup regardless of each groups’ performance on a task). This operationalization is consistent with Haslanger’s (2016) argument that, within a social structure, social constraints “set limits, organize thought and communication, create a choice architecture; in short, they structure the possibility of space for agency” (p. 128). In the present study, the disadvantaged group in the structural conditions had no agency over their access to resources because the individual in charge of allocating the resources always gave more to their ingroup members regardless of performance.

To ensure consistency across the individual and structural conditions, we used a group-based paradigm with same-gender groups (for similar approaches with race, see Elenbaas et al., 2016; Olson et al., 2011). That is, regardless of condition, children were assigned to a group comprised of gender ingroup peers that competed against an outgroup comprised of gender outgroup peers.

We operationalized status as pertaining specifically to resource-based status (having more or fewer resources) given research documenting the saliency of resource allocations and disputes in children’s lives (Corsaro, 2017; Damon, 1977). Accordingly, we defined “advantaged status” as children who received more resources than other peers and defined “disadvantaged status” as children who received fewer resources than other peers. We acknowledge, however, that “status” can refer to a range of factors with various implications and manifestations. Finally, we examined intentional inequalities that resulted in clear differences in status (i.e., inequalities that were intentionally and explicitly created and maintained by an individual to advantage one group over another) to reflect the intentional nature of many pressing inequalities evident in broader society (Kendi, 2016; Ridgeway, 2015; Roberts & Rizzo, 2020).

The age range (3- to 8-years-old) sampled in this study was based on past research documenting developmental changes during this time in children’s understanding of equity, fairness, and equality, as well as knowledge about groups. We also note the importance of understanding children’s early emerging beliefs about inequalities, as they provide both an understanding of the inequalities that young children experience in their everyday lives and an insight into the developmental foundations upon which older children, adolescents, and adults build their understanding of inequality and injustice (Ruck et al., 2019). Age groups (Younger: 3- to 5-years-old, Older: 6- to 8-years-old) were defined to allow for a closer comparison to past research that commonly uses these groupings. Analyses revealed identical effects when age was analyzed continuously, and thus the results are discussed using the age-groups to allow for a more direct comparison to past research.

Theoretical framework and hypotheses.

The social reasoning developmental (SRD) model (Elenbaas et al., 2020; Mulvey, 2016; Rutland & Killen, 2015) guided the present research. The SRD model integrates foundational theories on children’s social-cognitive development to explain how a range of social concerns impact children’s perceptions of their social world. Specifically, the SRD model integrates social domain theory which examines children’s developing moral, social-conventional, and psychological reasoning (Smetana et al., 2014; Turiel, 2002, 2015), and social-developmental theories regarding children’s developing group identity and understanding of group dynamics (Abrams & Rutland, 2008; Nesdale, 2004; Tajfel & Turner, 1979). Briefly, the SRD model defines moral concerns as those that pertain to fairness, justice, others’ welfare, and individuals’ rights, group concerns as those that pertain to intra- and intergroup dynamics (e.g., group norms, group loyalty), and personal/psychological concerns as issues that are up to personal choice and individual prerogatives. Past research has identified how children evaluate each of these concerns in different ways beginning early in development (for a review, see Killen et al., 2018). The SRD model makes three predictions that are particularly relevant to the present study which examined children’s 1) judgments of inequalities; 2) judgments of equal, rectifying, and perpetuating inequalities; and 3) allocation of resources.

First, the SRD model argues that individuals actively reason about moral (e.g., fairness, equality, merit), group (e.g., ingroup loyalty, adherence to group norms), and personal (e.g., own desires and autonomy) concerns when making social decisions, and that children weigh and prioritize these concerns in a contextually-specific way based on their salience within a context (see Killen et al., 2018). In the present study, we expected the concerns for merit to be more salient in the individual condition and that concerns for equity would be more salient in the structural condition. Accordingly, we hypothesized that children would evaluate structurally-based inequalities to be more unfair than individually-based inequalities (H1). Evaluating structurally-based inequalities to be more unfair than individually-based inequalities would be evidenced by children judging the structural inequality to be more unfair than the individual inequality, judging perpetuating allocations to be more unfair for the structural than individual inequality, judging rectifying allocations to be more fair for the structural than individual inequality, and being more likely to rectify (and less likely to perpetuate) the structural than individual inequality. That is, across each of our primary measures, we expected to find a main effect for type of inequality, with children generally viewing structurally-based inequalities to be more unfair (and more in need of rectification) than individually-based inequalities.

Second, the SRD model argues that children’s reasoning reflects different priorities depending on their perspective or status within group contexts, and that competitive intergroup contexts (e.g., when two groups are competing over resources) can increase the salience of group-based concerns (McGuire et al., 2018a, 2018b). Accordingly, we hypothesized that children who were advantaged by the inequality would evaluate the inequalities to be less unfair than would children who were disadvantaged by them (H2). Evaluating advantageous inequalities to be less unfair than disadvantageous inequalities would be evidenced by advantaged children judging the inequalities to be less unfair than disadvantaged children, advantaged children judging perpetuating allocations to be less unfair than disadvantaged children, advantaged children judging rectifying allocations to be less fair than disadvantaged children, and advantaged children being more likely to perpetuate (and less likely to rectify) the inequality than disadvantaged children. That is, across each of our primary measures, we expected to find a main effect for status, with children who were advantaged by the inequality evaluating it to be less unfair (and less in need of rectification) than children who were disadvantaged by it.

And third, the SRD model argues that development occurs within domains (e.g., with age children develop a more mature understanding of the moral concerns for fairness) and across domains (e.g., with age, children become better at coordinating moral and group concerns). For example, with age, children become better able to recognize when personal or group concerns conflict with moral concerns (e.g., recognizing when taking a larger share of resources for one’s group means depriving another group of needed resources; Cooley & Killen, 2015). Accordingly, we hypothesized that, with age, children who were advantaged by the inequality would be more likely to evaluate the inequality to be unfair (H3). This view would be evidenced by older-advantaged children judging the inequalities to be more unfair than younger-advantaged children, older-advantaged children judging perpetuating allocations to be more unfair than younger-advantaged children, older-advantaged children judging rectifying allocations to be less unfair than younger-advantaged children, and older-advantaged children being more likely to rectify (and less likely to perpetuate) the inequality than younger-advantaged children. That is, across each of our primary measures, we expected to find an age by status interaction, with older-advantaged children evaluating inequalities to be more unfair (and more in need of rectification) than younger-advantaged children.

Methods

Participants

Children between the ages of 3- and 8-years-old (N = 176; 91 female, 85 male) participated in the study. The breakdown for age was: 13 3-year-olds, 47 4-year-olds, 35 5-year-olds, 32 6-year-olds, 34 7-year-olds, and 15 8-year-olds. Participants’ ethnicity was approximately representative of the sampling population: 70% European American, 16% African American, 10% Latinx, and 4% Asian American. The median annual household income was $91,918. The income data were based on the median annual household income of the county in the Mid-Atlantic region of the U.S. where the data were collected (and are middle-income for the region based on the cost of living). Six additional participants (2 three-year-olds, 3 four-year-olds, and 1 six-year-old) were interviewed but not included in the final analyses due to experimenter error (n = 1) or a failure to understand the key premises of the studies (determined by failing the memory checks; n = 5). Female researchers conducted 122 of the interviews, and a male researcher conducted the remaining 54. Preliminary analyses did not yield any effects for experimenter gender. The protocol for this study was approved by the IRB at the University of Maryland, protocol number: 965920–3, title: Children’s Perceptions of Individual and Structural Inequalities.

An a priori power analysis using G*Power (Faul et al., 2009), revealed that for our 2 (Type of Inequality: Individual, Structural) x 2 (Status: Advantaged, Disadvantaged) x 2 (Age: Younger, Older) design, a sample of 179 participants was needed to detect medium effects (f = .25) at an acceptable power (.80 or greater), with α = .05. Thus, we collected 182 participants using the stopping rule of stopping data collection at the end of the day when the 179th participant was collected, which allowed us to maintain adequate statistical power after dropping six participants, resulting in N = 176.

Procedure

Trained research assistants interviewed participants individually in a quiet space at their school. The protocol was administered using Microsoft Office PowerPoint 2013 and was narrated by the research assistant; data were collected in 2016–2017. Prior to beginning the experiment, participants were shown how to use the 6-point Likert-type scale that was used throughout the protocol. Participants assigned to the disadvantaged condition were debriefed at the end of the study – the experimenter told participants that there had been a computer error and that their team had actually won the game and they were awarded the full set of prizes. These “in-game” prizes were depicted as pictures of gift boxes with bows on them and did not translate to any form of actual compensation or reward outside of the experimental paradigm. Following the interview, participants were escorted back to their classrooms. Interviews lasted between 18–26 minutes and participants did not receive any form of direct compensation for their participation.

A 2 (Age: Younger, Older) X 2 (Status: Advantaged, Disadvantaged) X 2 (Type of Inequality: Individual, Structural) between-subjects design was used, resulting in four experimental conditions: Advantaged-Individual, Advantaged-Structural, Disadvantaged-Individual, Disadvantaged-Structural. All participants, regardless of condition, heard the same group identity induction (modified from Nesdale, 2004) and responded to an identical set of assessments. The only differences across the four conditions pertained to how and why the prizes were given out (see below).

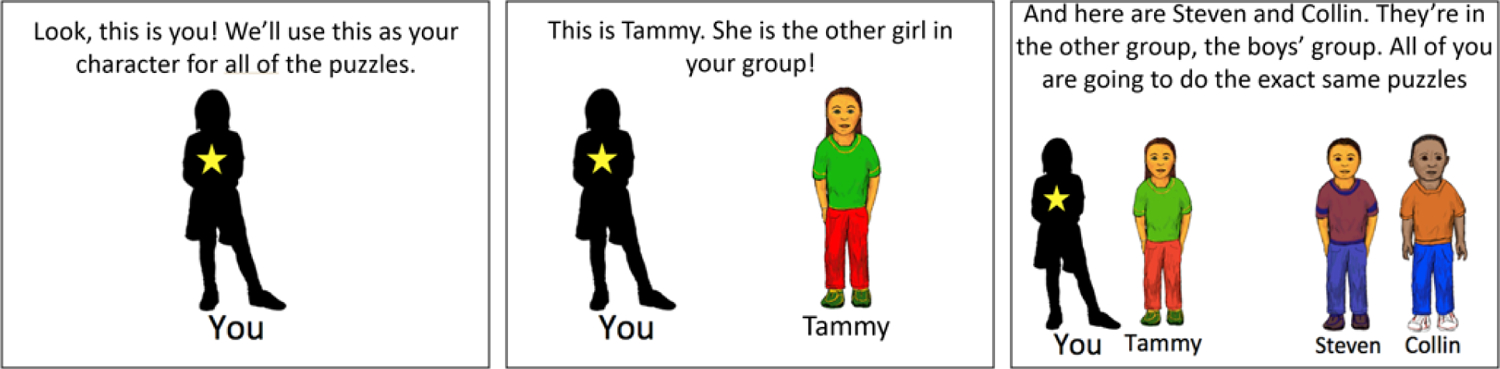

Group identity induction.

All participants were told that they had been chosen to join an online puzzle club, where they can complete puzzles with other children to earn prizes (see Figure 1). Participants were then introduced to their own avatar for the game, and the avatars of an ingroup member (who was a member of their gender ingroup) and two outgroup members (who were members of their gender outgroup). The groups were explicitly labeled as the “boys” group and the “girls” group to remain consistent with past research examining children’s understanding of gender-intergroup dynamics (e.g., Mulvey et al., 2015), and the ubiquity of gender labels in children’s daily lives (Ruble et al., 2006).

Figure 1.

Group identity induction for female participants. The first slide introduces the participant to their avatar, the second introduces the participant to their ingroup member, and the third introduces the participant to their outgroup members.

Puzzle task, allocation of prizes, and conditions.

Research assistants then told participants that everyone would be completing the same “Find the Differences” puzzles and provided them with instructions on how to complete the puzzles. After a short practice trial, participants then completed one of the puzzles. To control for actual performance, research assistants waited for participants to find 3 (of the possible 10) differences and then ended the activity saying, “Great job! You found 3 differences!” After completing the puzzles, participants were then introduced to a new peer, Alex, who was in charge of giving out the prizes. Critically, regardless of condition, Alex’s gender always matched the group that received more prizes (i.e., for an advantaged-female participant, Alex would be portrayed as female, whereas for a disadvantaged-female participant, Alex would be portrayed as male). The four between-subjects conditions (random assignment) were the following:

Advantaged-Individual.

Participants were told that their group had performed better on the puzzle, and that Alex was going to base their allocation on how well each group performed on the puzzle. Accordingly, Alex allocated 3 prizes to the participant and their ingroup member and allocated 1 prize to each of the outgroup members.

Advantaged-Structural.

Participants were told that the groups had tied on the puzzle, and that Alex was going to give more prizes to their gender ingroup. Accordingly, Alex allocated 3 prizes to the participant and their ingroup member and allocated 1 prize to each of the outgroup members.

Disadvantaged-Individual.

Participants were told that the other group had performed better on the puzzle, and that Alex was going to base their allocation on how well each group performed on the puzzle. Accordingly, Alex allocated 1 prize to the participant and their ingroup member and allocated 3 prizes to each of the outgroup members.

Disadvantaged-Structural.

Participants were told that the groups had tied on the puzzle, and that Alex was going to give more prizes to their gender ingroup. Accordingly, Alex allocated 1 prize to the participant and their ingroup member and allocated 3 prizes to each of the outgroup members.

To ensure that participants understood both of the salient manipulations (Status, Type of Inequality), and that the allocator (Alex) was systematic in their allocations, participants completed two puzzles and received resources in the exact same way both times (Advantaged participants and their gender ingroup member finished with 6 prizes, whereas Disadvantaged participants and their gender ingroup member finished with 2 prizes). After the second trial, participants were assessed on two memory questions to confirm their comprehension of the premises and manipulations: (1) “Can you tell me who did a better job on the puzzles? Did your group win, the girls’/boys’ group win, or did both groups win and find the same number of differences?” and (2) “Can you tell me who has more prizes? Does your group have more, the girls’/boys’ group have more, or do both groups have the same number?” Participants who failed the comprehension checks were retold the vignette from the end of the second puzzle completion (where the relevant information is revealed) and were reassessed on the memory checks up to two additional times. Participants who failed the memory checks all three times were excluded from data analyses (n = 5).

Assessments.

All participants, regardless of condition, were then assessed on their (1) Judgment of the Inequality (“How OK or not OK do you think it is that some kids got more prizes than others?”). Participants were then told that there were 8 more prizes to give out, and were asked for their (2) Judgments of Perpetuating, Equal, and Rectifying Allocations. Specifically, participants were shown each of the three allocation strategies (Perpetuating: giving 3 resources to both members of the Advantaged group and 1 resource to both members of the Disadvantaged group; Equal: giving 2 resources to both members of the Advantaged group and 2 resources to both members of the Disadvantaged group; Rectifying: giving 3 resources to both members of the Disadvantaged group and 1 resource to both members of the Advantaged group). For each allocation strategy, participants were asked, “How OK or not OK would that be?” Finally, participants were assessed on their (3) Own Allocation (“Can you show me how you think the prizes should be given out?”).

All judgment assessments were scored on a 6-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1: “Really not Okay” to 6: “Really Okay” and the Own Allocation assessment was scored categorically as: “Perpetuating Allocation”, “Equal Allocation”, and “Rectifying Allocation.”

Results

Data analytic plan

To test hypotheses regarding children’s judgments of the inequality, a 2 (Age: Younger, Older) X 2 (Status: Advantaged, Disadvantaged) X 2 (Type of Inequality: Individual, Structural) Univariate ANOVA was conducted with children’s judgment of the inequality as the dependent variable. To test hypotheses regarding children’s judgments of perpetuating, equal, and rectifying allocations, separate Age X Status X Type of Inequality Univariate ANOVAs were conducted for each Allocation Strategy (Perpetuating, Equal, Rectifying). To test hypotheses regarding children’s own allocations of resources, a generalized linear model was first conducted to identify significant effects and interactions, and then follow-up likelihood ratio X2 tests (LRT) were conducted to interpret the significant effects. For the sake of concision, only significant effects and interactions are reported. All effects or interactions that are not explicitly reported in the manuscript were not significant (p > .05).

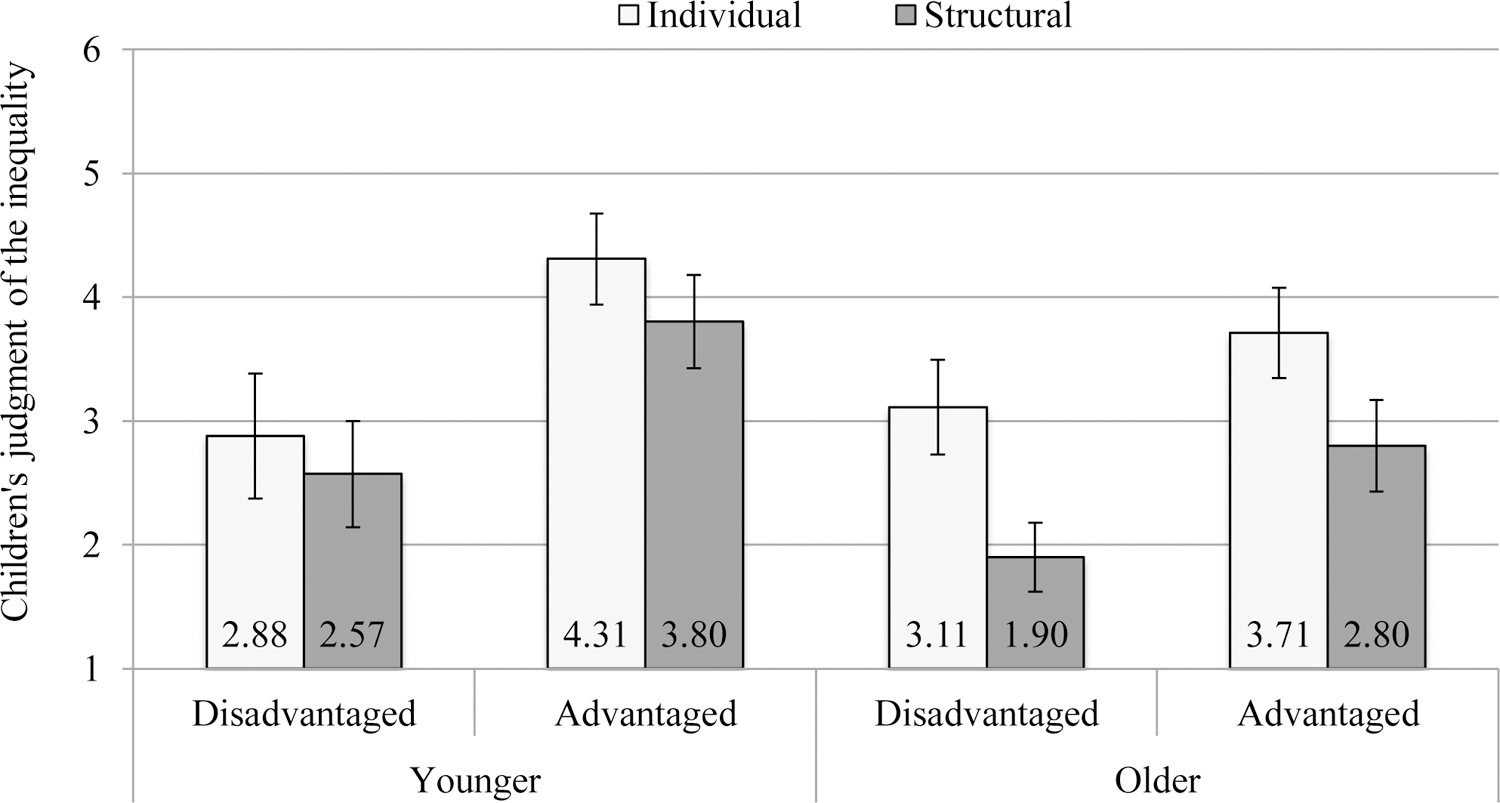

Judgments of the inequality

Children judged structurally-based inequalities to be more unfair than individually-based inequalities (main effect for Type of Inequality: F(1,167) = 7.37, p = .007, ηp2 = .042; see Figure 3). Additionally, children who were disadvantaged by the inequality judged it to be more unfair than children who were advantaged by it (main effect for Status: F(1,167) = 14.81, p < .001, ηp2 = .081). A main effect for Age was not found (p = .061), and there were no significant interactions between the variables (all ps > .20). Thus, our hypotheses regarding the type of inequality (H1) and status (H2) were supported. Our age-related hypothesis (H3), however, was not supported.

Figure 3.

Children’s judgment of the inequality by Age (Younger, Older), Status (Advantaged, Disadvantaged), and Type of Inequality (Individual, Structural). Scale: 1 = “Really Not Okay” to 6 = “Really Okay”. Bars represent the standard error of the means. Age is included in the figure for presentational purposes, but was not a significant predictor in the model.

Judgments of perpetuating, rectifying, and equal allocations

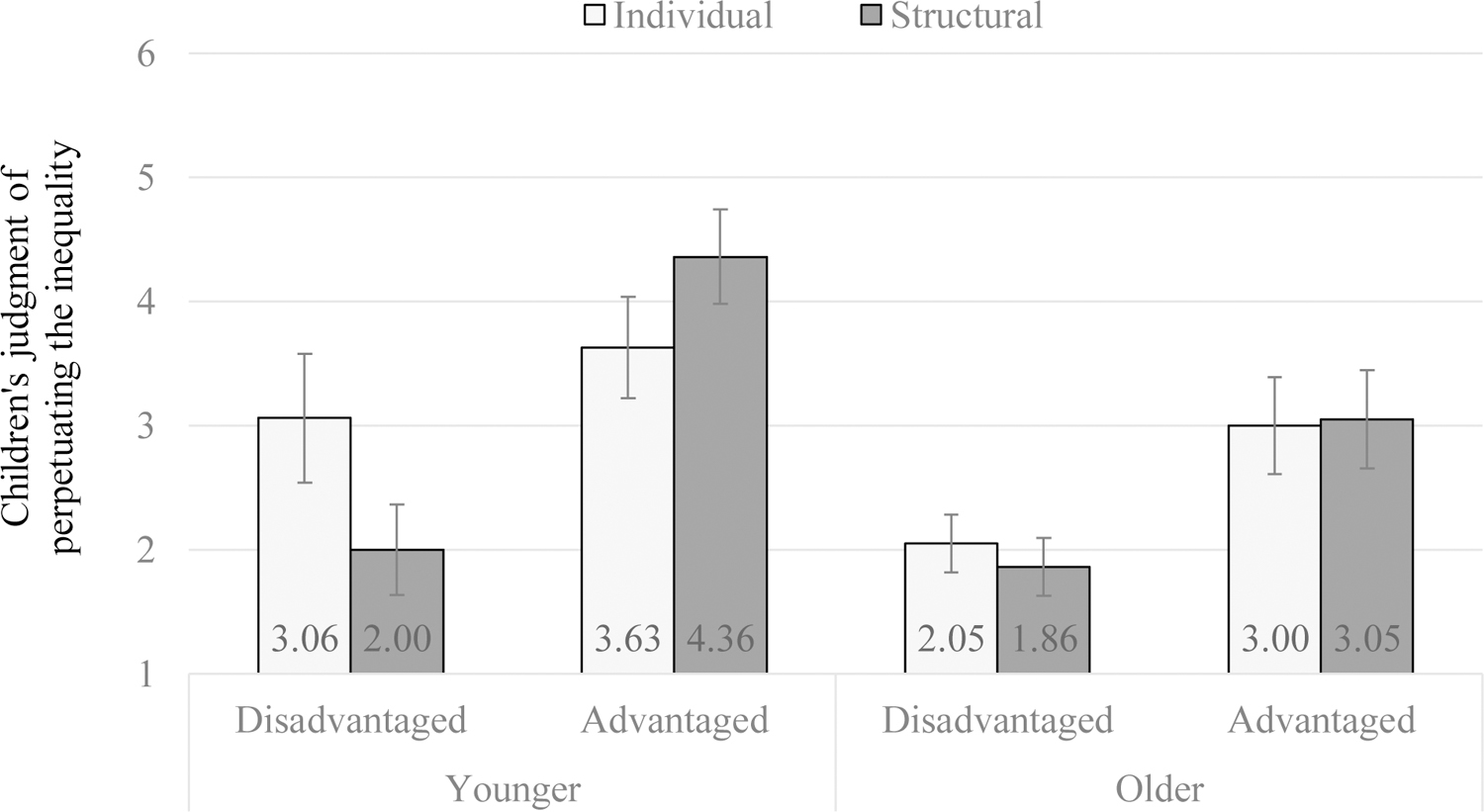

Perpetuating allocation.

Children who were disadvantaged by the inequality judged the perpetuating allocation to be more unfair than children who were advantaged by it (main effect of status: F(1,165) = 21.84, p < .001, ηp2 = .12; see Figure 4). Additionally, children judged the perpetuating allocations to be more unfair with age (main effect of age: F(1,165) = 8.11, p = .005, ηp2 = .047). An interaction between status and type of inequality was marginal, but not significant (p = .062). Thus, our hypotheses regarding status (H2) and age-related changes (H3) were supported. Our hypothesis regarding the type of inequality (H1), however, was not supported.

Figure 4.

Children’s judgment of the perpetuating allocation by Age (Younger, Older), Status (Advantaged, Disadvantaged), and Type of Inequality (Individual, Structural). Scale: 1 = “Really Not Okay” to 6 = “Really Okay”. Bars represent the standard error of the means. Type of Inequality is included in the figure for presentational purposes, but was not a significant predictor in the model.

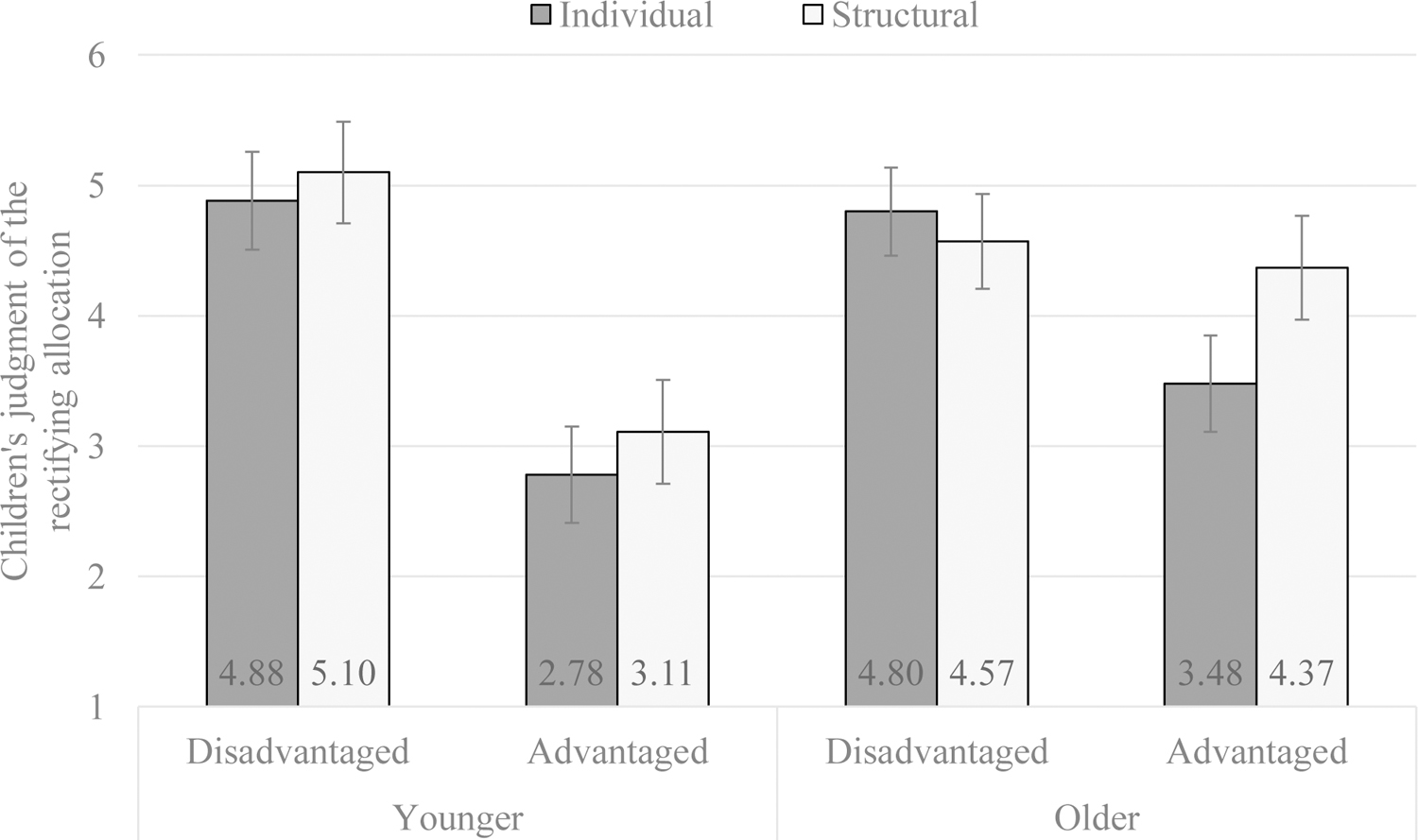

Rectifying allocation.

With age, children who were advantaged by the inequality judged the rectifying allocation to be more fair (age-related differences were not found for disadvantaged children; interaction between Age and Status: F(1, 165) = 5.40, p = .021, ηp2 = .032; main effect for status: F(1, 165) = 26.00, p < .001, ηp2 = .14; see Figure 5). Thus, our hypotheses regarding status (H2) and age-related changes (H3) were supported. Our hypothesis regarding the type of inequality (H1), however, was not supported.

Figure 5.

Children’s judgment of the rectifying allocation by Age (Younger, Older), Status (Advantaged, Disadvantaged), and Type of Inequality (Individual, Structural). Scale: 1 = “Really Not Okay” to 6 = “Really Okay”. Bars represent the standard error of the means. Type of Inequality is included in the figure for presentational purposes, but was not a significant predictor in the model.

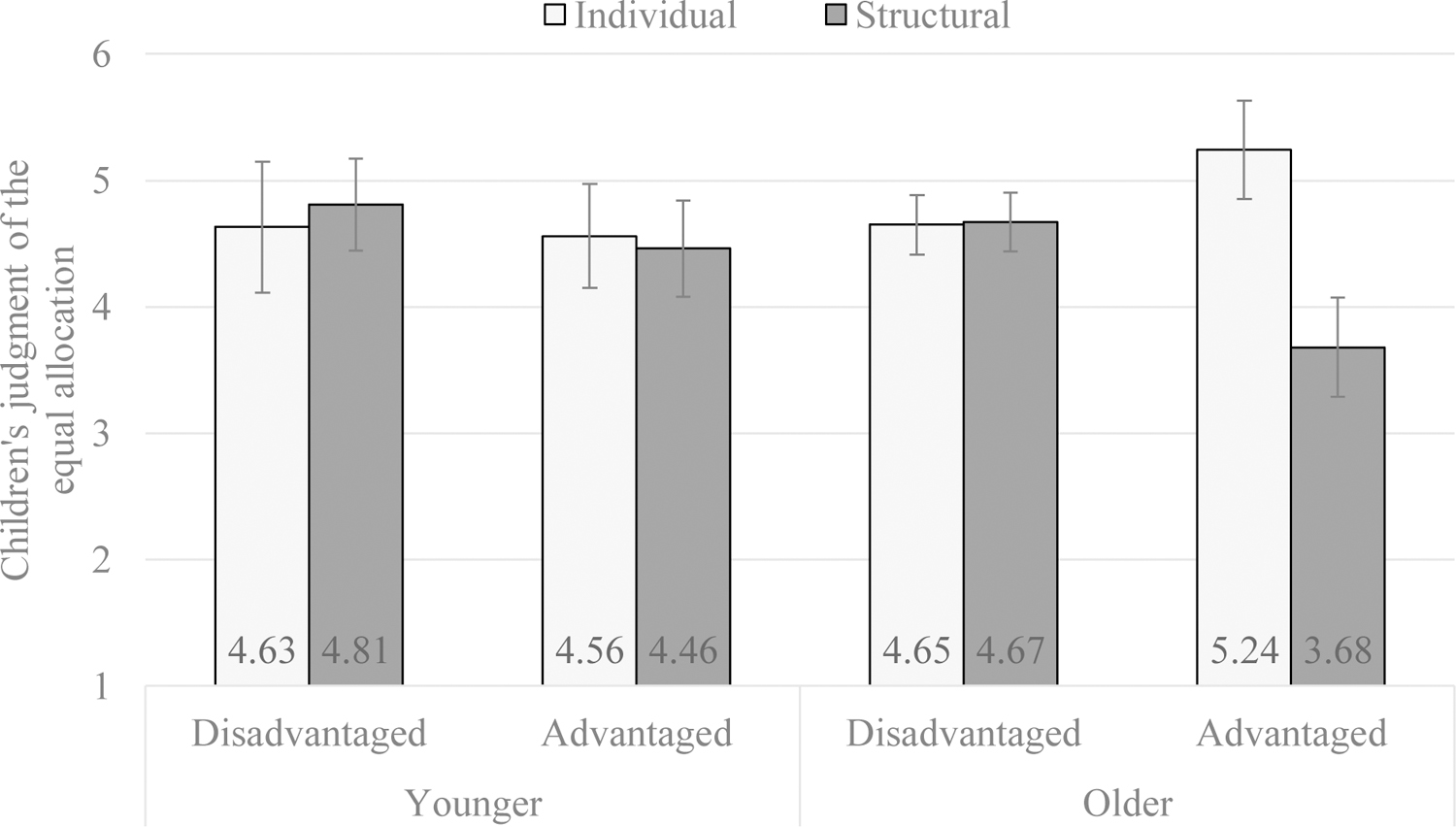

Equal allocations.

No significant effects or interactions were found (all ps > .096; see Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Children’s judgment of the equal allocation by Age (Younger, Older), Status (Advantaged, Disadvantaged), and Type of Inequality (Individual, Structural). Scale: 1 = “Really Not Okay” to 6 = “Really Okay”. Bars represent the standard error of the means. The figure is presented for descriptive purposes - no significant effects were found.

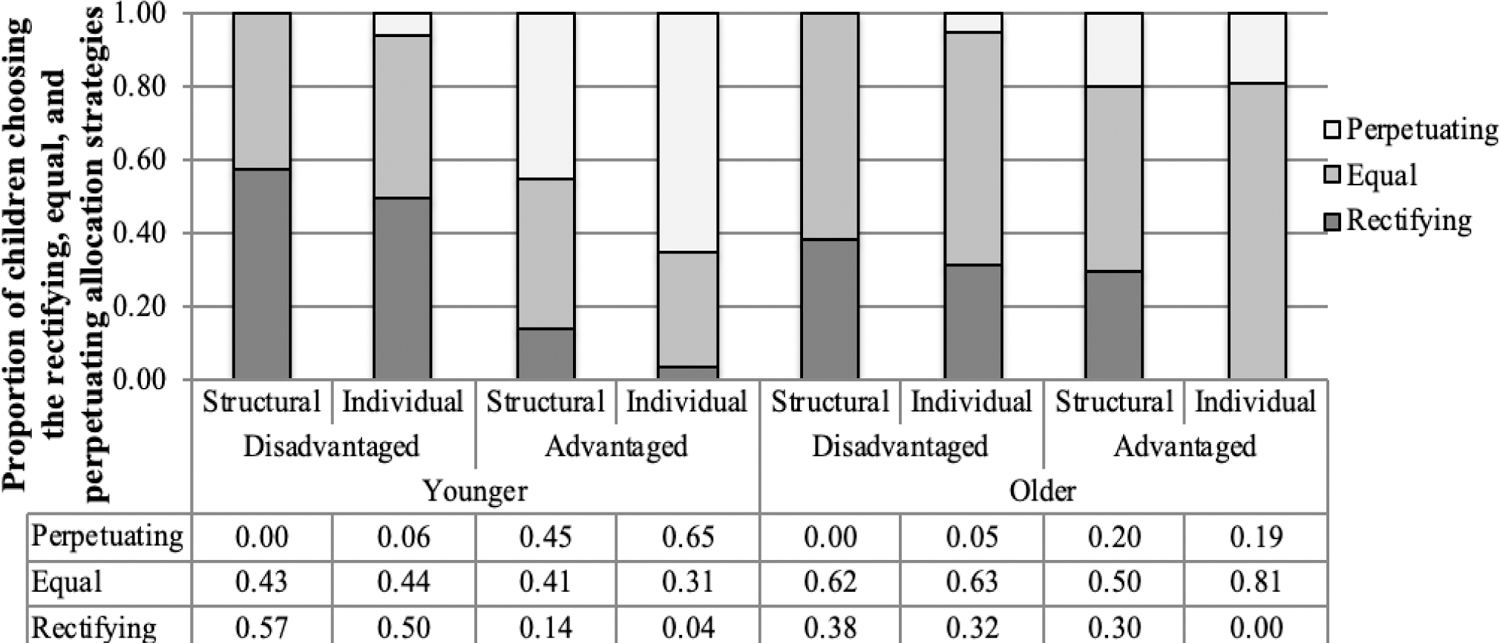

Children’s allocations

Children who were advantaged by the inequality were more likely to rectify the structurally-based inequality than the individually-based inequality (differences were not found for children who were disadvantaged by the inequality; Type of Inequality by Status interaction: LRT X2 (2) = 7.94, p = .019; main effect for Status: LRT X2 (2) = 50.22, p < .001; see Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Proportion of children allocating resources by choosing one of three strategies: Perpetuating, Equal, and Rectifying allocations by Age (Younger, Older), Status (Advantaged, Disadvantaged), and Type of Inequality (Individual, Structural). Proportions are reported in the table below the figure.

With age, children became less likely to perpetuate advantageous inequalities (individual and structural), and became more likely to allocate equally (age-related differences were not found for children who were disadvantaged by the inequalities; Age by Status interaction: LRT X2 (2) = 12.09, p = .02; main effect of Age: LRT X2 (2) = 15.58, p < .001).

Interestingly, children also became less likely to perpetuate individual inequalities (advantageous and disadvantageous) with age, again becoming more likely to allocate equally (age-related differences were not found structural inequalities; Age by Type of Inequality interaction: LRT X2 (2) = 12.36, p = .002).

Thus, all of our primary hypotheses were supported; children were more likely to rectify structurally- than individually-based inequalities (particularly when advantaged) and became less likely to perpetuate individual inequalities with age (H1) and became less likely to perpetuate advantageous inequalities with age (H2, H3).

Discussion

Social inequalities are a pressing societal concern throughout the lifespan (Duncan & Murnane, 2011; Turiel, 2002). Investigating how children think and reason about inequalities provides important new evidence regarding the psychological processes that create, maintain, and perpetuate them, as well as the developmental trajectories of these processes (Ruck et al., 2019; Roberts & Rizzo, 2020). Supporting several of the propositions in the social reasoning developmental (SRD) model (Killen et al., 2018), we found general support for the idea that children judge structural inequalities to be more unfair and in need of rectification than individual inequalities (H1), judge inequalities to be less unfair and in need of rectification when they are advantaged by them (H2), and become better at recognizing the need for rectifying advantageous inequalities with age (H3). Yet, we also found that the majority of older children defaulted to an equal allocation when given the chance.

Broadly, these findings merge and extend separate bodies of literature examining children’s emerging understanding of structural inequalities (Elenbaas et al., 2020; Peretz-Lange & Muentener, 2019; Elenbaas & Killen, 2016; McLoyd, 2019; Rizzo et al., 2018; Vasilyeva & Ayala, 2019), the delayed rejection of advantageous relative to disadvantageous inequalities (Blake et al., 2015; McGuire et al., 2018a, 2018b; Sheskin et al., 2016; Shaw et al., 2016), and children’s perpetuation of group-based inequalities and status hierarchies (Brown, 2017; Elenbaas, 2019; Dunham et al., 2011; Mehta & Strough, 2009; Renno & Shutts, 2015; Ruble et al., 2006). Below, we discuss several of these important connections and extensions, as well as directions for future research in this area.

Children distinguish between individually- and structurally-based inequalities (H1)

Even the youngest children in the present study (3- to 5-year-olds) judged structural inequalities to be more unfair than individual inequalities and were more likely to rectify them when given the chance. Beginning in early childhood, children develop the belief that individuals who work harder and produce more should be rewarded for their efforts (Baumard et al., 2011; Rizzo et al., 2016; Schmidt et al., 2016). These beliefs reflect an early-emerging understanding of the moral concern for merit-based fairness. At the same time, children are also developing an early awareness of equity and the wrongfulness of discrimination and bias (Elenbaas et al., 2020; Killen et al., 2018). Consistent with the SRD model, these results support the idea that children’s concerns for merit- and equity-based fairness coexist from early in development and are applied in contextually-specific ways. Children think flexibly and reason about the moral concerns present within a context when judging whether the context is fair or unfair and deciding what they should do about it.

Importantly, even advantaged children were more likely to rectify structurally- than individually-based inequalities in the present study. These results suggest that despite a generally higher support for advantageous inequalities than disadvantageous inequalities (see below), children in advantaged positions were still capable of recognizing when they were being unfairly advantaged due to their gender. Combined with past research documenting a connection between children’s judgments of inequalities and their behavioral responses to those inequalities (Essler et al., 2020; Rizzo & Killen, 2016, but see Smith et al., 2013), these results suggest that one way to help children reject and rectify structurally-advantageous inequalities is to encourage them to focus on the wrongfulness of the inequality. Future research using larger sample sizes should continue to examine how children’s evaluations of inequalities mediate or moderate their responses to them, regardless of advantaged/disadvantaged status. Such results would speak to a broader importance of emphasizing the wrongfulness of structural inequalities to children as a way of encouraging them to fully address them.

Status shapes children’s responses to inequalities (H2)

Children who were advantaged by the inequalities were less likely to view them as unfair, less likely to support rectifying them (and more likely to support perpetuating) them, and were themselves less likely to rectify (and more likely to perpetuate) them relative to disadvantaged children. These results indicate that children are not only more likely to accept/perpetuate inequalities that advantage them (Blake et al., 2015; Sheskin et al., 2016; Shaw et al., 2016), but that they are also less likely to hold prescriptive beliefs about their unfairness.

Why were advantaged children less likely to view the inequalities as wrong and in need of rectification? The SRD model argues that children actively consider a range of moral, group, and personal concerns when reasoning in social contexts. In the present study, advantaged children’s concern for ingroup loyalty (i.e., ensuring that their group’s resources and status were protected) may have precluded them from fully recognizing the harm caused to the disadvantaged group and the unfairness of the inequality. A growing body of research has examined how children’s status within an inequality impacts their perceptions of social contexts and systems. For example, Rizzo and Killen (2018) found that experimentally inducing children into an advantaged group led them to perform worse on false-belief and belief-emotion theory of mind assessments relative to those who were disadvantaged (see Kraus et al., 2010, 2012 for similar findings with adults). These results suggest that children’s status may be related to how they weigh and prioritize different concerns. When children are advantaged, they may be less likely to consider others’ welfare and the unfairness of the inequality and more likely to focus on concerns for ingroup loyalty.

Related findings by McLoughlin, Over, and colleagues (McLoughlin et al., 2018; McLoughlin & Over, 2017, 2019) regarding young children’s tendency to dehumanize outgroup members also speaks to a larger, yet relatively unexplored, area of contextual and social-cognitive processes that shape and drive children’s perceptions of intergroup contexts. Future research should continue to investigate how advantaged and disadvantaged perspectives might shape the way children construct their understanding of their social worlds, both as they currently are and as they should be (also see Kirkland et al., 2019; Wang & Roberts, 2019).

Children are less likely perpetuate advantageous inequalities as they get older (H3)

With age, advantaged children were more supportive of rectifying inequalities, were less supportive of perpetuating inequalities, and were less likely to actively perpetuate inequalities. Consistent with past research on children’s developing responses to inequalities, this pattern of results is indicative of a developing prioritization of equity over equality in contexts of inequality (Essler et al., 2020; Rizzo & Killen, 2016) and a developing ability to recognize this concern when one (or one’s group) is being advantaged (e.g., Blake et al., 2015; Elenbaas et al., 2016). Importantly, however, advantaged children did not fully shift from perpetuation to rectification. Rather, when allocating resources, they became more likely to allocate equally with age.

These developmental findings are important for several reasons. First, differences in children’s judgments of others’ allocations suggest that children’s understanding of their role as active agents within inequality contexts changes with age. According to the SRD model, this development can be explained by children’s developing recognition of the moral concerns for equity and fairness and by children’s developing ability to prioritize moral over group and personal concerns. In this study, children were simultaneously aware of a range of considerations bearing on how to fairly allocate resources (moral), maintain one’s status within their group (group), and achieve personal desires for resources (personal). When making decisions about how to allocate resources, children had to give priority to one of these concerns (fairness, ingroup loyalty, own desires) over others (e.g., prioritizing equality by allocating equally, prioritizing equity by rectifying).

Children reject and protect structural inequalities

A major barrier to rectifying inequalities is resistance from high-status group members who, by virtue of their status, wield disproportionate control over the perpetuation of the hierarchy. Thus, at the heart of the present study is a question that holds important implications for our understanding of inequalities: How do children perceive of, and respond to, structurally-advantageous inequalities? By comparing children’s responses to structurally-advantageous inequalities to their responses to individually-advantageous inequalities, as well as their responses to structurally-disadvantageous inequalities, the present study provides a nuanced and contextualized account of this important question. In this study, children in the structurally-advantageous context: (1) recognized that the structurally-based inequality was more wrong than the individually-based inequality, but still judged it to be more fair than the children who were disadvantaged by it; (2) were less likely to support blatant perpetuation of structurally-advantageous inequalities with age, but never became fully supportive of rectification; and (3) were more likely to rectify structurally-advantageous inequalities with age, but just barely, and a majority still opted to maintain the status-quo inequality via equal allocation.

Taken together, these results indicate that children in structurally advantageous contexts struggle to fully prioritize the moral concerns for equity and the wrongfulness of discrimination over group concerns for ingroup loyalty and protecting their group’s advantaged status. Past research has found that older children often rectify structural and group-based inequalities that advantage their ingroup in third-party contexts (Elenbaas et al., 2016; Olson et al., 2011). The fact that the majority of children in the present study allocated equally in response to the structurally-advantageous inequality in the present study suggests that prioritizing equity is particularly difficult for children who are personally embedded within an inequality context. This difficulty in turn led most children into a pattern of responding that neither explicitly endorsed the structural bias (thus maintaining the appearance of impartiality) but also did nothing to address or challenge it, thus resulting in a passive maintenance of the structural inequality.

The problem with this approach, however, is that allocating resources equally in contexts with preexisting inequalities simply maintains the status quo inequality. Thus, although previous research has documented that older children reject the introduction of new inequalities (Blake & McAuliffe, 2011; Blake et al., 2015; Sheskin et al., 2016; Shaw et al., 2016), the present study suggests that the majority of these older children fail to reject preexisting inequalities. One reason that children might opt to passively maintain (i.e., allow inequalities to persist through an equal distribution of new resources moving forward) inequalities is that they might come to view them as fair. Research with adults has found that people often attempt to justify the inequalities that exist around them, and particularly those that advantage them (Pratto et al., 1994). Yet, this cannot fully explain the present results, given that children did not justify the inequalities in their judgments of them, suggesting that there is something specific about actively rectifying an inequality or injustice that is particularly difficult for children (and adults). Thus, future research is needed to identify the contextual factors and psychological processes that lead children to prioritize passive maintenance of inequalities over an active rectification of them, as well as to identify the developmental mechanisms that might be leveraged to help children recognize the importance of anti-biased action.

Interestingly, although structurally disadvantaged children were far more likely to support attempts to rectify structurally-based inequalities, a majority of this group still opted for the passive approach (i.e., an equal allocation strategy) and judged the passive approach positively. Consistent with work in system justification theory (Jost et al., 2004) it is possible that disadvantaged children legitimized the inequality in their own minds before allocating resources. Although this is possible, the disadvantaged children in the present study judged the inequality to be unfair and resoundingly supported rectifying it. An alternative interpretation of these results is that children in the present study were concerned with their reputation and did not want to appear biased, even if that action would have been anti-biased (Engelmann et al., 2018; Leimgruber et al., 2012). That is, disadvantaged children may have wanted to rectify the inequality, but did not want others to perceive them as taking more than an equal share. This, however, is also a problem. If children’s social environments are structured in such a way that leads children in structurally-disadvantaged positions to fear appearing biased when responding to structural injustices, these environments are effectively ensuring that the injustice goes unchecked. Thus, in addition to examining how to facilitate structurally-advantaged children’s willingness to take an active approach in rectifying structural inequalities, future research should also examine how to reduce the environmental pressures that discourage structurally disadvantaged children from publicly identifying and challenging the systemic barriers that limit their access to important resources and opportunities.

Limitations and future directions

The inequalities used in the present study were straightforward cases of individually- and structurally-based inequalities, and were explicitly marked as such. Most studies on inequalities in childhood rely on minimal groups or economic games that children do not experience in their everyday lives. The present study goes beyond this common methodology by providing meaningful insights into how children perceive and respond to inequalities that commonly occur within peer contexts, such as receiving more/fewer resources due to performance or being advantaged/disadvantaged due to another peers’ gender bias. Research on the sociology of childhood contends that children’s peer contexts reflect their constructive interpretations of the cultural norms, practices, and structures that they observe in broader society (Corsaro, 2017). On this account, how children come to think and reason about the inequalities they experience in their daily lives have important implications for how children will reason about societal inequalities across development (Ruck et al., 2019). Yet, the societal inequalities that exist in the United States and beyond are steeped in historical oppression and are reinforced and maintained by social systems much larger than the peer contexts examined in the present study (e.g., systems of gender and racial oppression in the United States; Ridgeway, 2015; Roberts & Rizzo, 2020). We thus urge caution in generalizing the results beyond the scope of the present study without additional research to address this point directly.

We also acknowledge that there are a variety of definitions for “structural” inequalities and constraints used throughout the theoretical and empirical literatures. Our definition was based on Haslanger’s (2016) account of social structures as “networks of social relations … [that] include relations between people: being a parent of, being an employee of, being a spouse of” (p. 126) and social constraints as, “[constraints that] set limits, organize thought and communication, create a choice architecture; in short, they structure the possibility of space for agency” (p. 128). Accordingly, in the present study, we operationalized the online puzzle club as a social structure and the group leader’s decision to allocate resources based on gender group membership—regardless of groups’ performance on the puzzle—as a social constraint within that structure (i.e. the disadvantage group had no agency over how many resources they acquired). Critical to our definition is also the idea that structural constraints are intentionally created and result in a status disparity (see Rizzo et al., 2018 and Rizzo & Killen, 2018 for similar approaches). Yet, other accounts of children’s developing awareness of structural constraints rely on more formal institutions (e.g., schools, governments) and physical manifestations of structural constraints (e.g., classrooms with different sized buckets for boys and girls) that do not necessarily result in differences in status (e.g., the opportunity to play two, equal status, games; see Vasilyeva & Ayala, 2019; Vasilyeva et al., 2018). We see these as complementary lines of research from which we can generate a broader understanding of how children come to think and reason about structural constraints and inequalities in their daily lives, and look forward to future research examining differences in children’s responses across these definitions.

Additionally, the inequalities used in the present study were situated within a developmentally- and age-appropriate context (i.e., a game with “winners,”) and the prizes offered were “luxury” rather than necessary resources (e.g., food, water, medicine; see Essler et al., 2020; Rizzo et al., 2016). Competitive contexts are important for understanding children’s beliefs about intergroup inequalities (McGuire et al., 2018a, 2018b), but inequalities are not always explicitly identified as competitive and often involve the denial of necessary resources such as access to educational and healthcare resources. Further, inequalities are often more complex than the straight-forward manifestations used in the present study. Future research should thus examine how children respond when one group performs better than another group on a task due to the structural advantages they receive (e.g., greater educational opportunities or resources), when the task itself is biased towards one group over another (e.g., standardized testing), and in contexts where the structural inequality leads to a more direct threat to the welfare of the disadvantaged group. Using a range of assessments, and experimental designs that allow for moderation and mediation analyses between the assessments, will also be particularly beneficial in identifying the psychological processes implicated in children’s perpetuation/rectification of inequalities.

Finally, the present study was conducted with children growing up in middle income neighborhoods. Past research with adult participants has found important relations between individuals’ socioeconomic standing and their perceptions of others and inequalities (Kraus et al., 2010, 2012). Developmental scientists are beginning to examine how children’s own wealth backgrounds is related to their developing beliefs about inequalities (Burkholder et al., 2019; Elenbaas, 2019). Yet, more research is needed to fully understand the sociocultural influences on children’s responses to inequalities (Ruck, et al., 2019; Rogers, 2019). One promising approach to this is to achieve more diverse samples (geographically, racially, and socioeconomically) via the use of online data collection and recruitment procedures (e.g., Rhodes et al., 2020; Sheskin et al., 2020). By conducting research online, parents and children can participate from any home or public computer with internet access, thus removing several of the barriers that limit participation in in-person developmental research.

Conclusion

The present study yielded novel and important insights into children’s developing evaluations of, and responses to, individually- and structurally-based inequalities. Bridging multiple literatures, the present study provided robust and consistent evidence that children’s perceptions of inequalities are shaped by social-contextual factors such as the reason for an inequality, as well as children’s age and perspective within the inequality. More broadly, these results speak to the sophistication—and limitations—that young children have when reasoning about inequalities, and the importance of future research aimed at helping children challenge the inequalities that they experience in their daily lives.

Contributor Information

Michael T. Rizzo, New York University

Melanie Killen, University of Maryland.

References

- Abrams D, & Rutland A (2008). The development of subjective group dynamics In Levy SR & Killen M (Eds.), Intergroup relations and attitudes in childhood through adulthood (pp. 47–65). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson ES (1999). What is the point of equality? Ethics, 109, 287–337. [Google Scholar]

- Baumard N, Mascaro O, & Chevallier C (2012). Preschoolers are able to take merit into account when distributing goods. Developmental Psychology, 48, 492–8. 10.1037/a0026598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake PR, & McAuliffe K (2011). “I had so much it didn’t seem fair”: Eight-year-olds reject two forms of inequity. Cognition, 120, 215–24. 10.1016/j.cognition.2011.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake PR, McAuliffe K, Corbit J, Callaghan TC, Barry O, Bowie A, Kleutsch L, Kramer KL, Ross E, Vongsachang H, Wrangham R, & Warneken F (2015). The ontogeny of fairness in seven societies. Nature, 528, 258–261. 10.1038/nature15703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown CS (2017). Discrimination in childhood and adolescence: A developmental intergroup approach. NY: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Burkholder A, Elenbaas L, & Killen M (2019). Children’s and adolescents’ evaluations of intergroup exclusion in interracial and inter-wealth peer contexts. Child Development, 91, 512–527. 10.1111/cdev.13249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conry-Murray C (2015). Children’s judgments of inequitable distributions that conform to gender norms. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 61, 319–344. 10.13110/merrpalmquar1982.61.3.0319 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Conry-Murray C (2019). Children’s reasoning about unequal gender-based distributions. Social Development, 28, 465–481. 10.11/sode.12342 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cooley S, & Killen M (2015). Young children’s evaluations of resource allocation in the context of group dynamics. Developmental Psychology, 51, 554–563. 10.1037/a0038796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corsaro WA (2017) The sociology of childhood (5th ed). Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Damon W (1977). The social world of the child. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan GJ, & Murnane RJ (2011). Whither opportunity?: Rising inequality, schools, and children’s life chances. Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Dunham Y, Baron AS, & Carey S (2011). Consequences of “minimal” group affiliations in children. Child Development, 82, 793–811. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01577.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elenbaas L (2019). Against unfairness: Young children’s judgments about merit, equity, and equality. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 186, 73–82. 10.1016/j.jecp.2019.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elenbaas L, & Killen M (2016). Children rectify inequalities for disadvantaged groups. Developmental Psychology, 52, 1318–1329. 10.1037/dev0000154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elenbaas L, Rizzo M, & Killen M (2020). A developmental science perspective on social inequality. Current Directions in Psychological Science. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Elenbaas L, Rizzo MT, Cooley S, & Killen M (2016). Rectifying or perpetuating resource disparities: Children’s responses to social inequalities based on race. Cognition, 155, 176–187. 10.1016/j.cognition.2016.07.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelmann JM, Herrmann E, & Tomasello M (2018). Concern for group reputation increases prosociality in young children. Psychological Science, 29, 181–190. 10.1177/0956797617733830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essler S, Lepach AC, Petermann F, & Paulus M (2020). Equality, equity, or inequality duplication? How preschoolers distribute necessary and luxury resources between rich and poor others. Social Development, 29, 110–125. 10.1111/sode.12390 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Faul F, Erdfelder E, Buchner A, & Lang AG (2009). Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods, 41, 1149–60. 10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haslanger S (2016). What is a (social) structural explanation? Philosophical Studies, 173, 113–130. doi: 10.1007/s11098-014-0434-5. (Published online 1/9/15). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hussak LJ & Cimpian A (2015). An early-emerging explanatory heuristic promotes support for the status quo. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 109, 739–752. 10.1037/pspa0000033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jost JT, Banaji MR, & Nosek BA (2004). A decade of system justification theory: Accumulated evidence of conscious and unconscious bolstering of the status quo. Political Psychology, 25(6), 881–919. [Google Scholar]

- Kanngiesser P, & Warneken F (2012). Young children consider merit when sharing resources with others. PloS One, 7, e43979 10.1371/journal.pone.0043979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendi IX (2016). Stamped from the beginning: The definitive history of racist ideas in America. NY: Nation Books. [Google Scholar]

- Killen M, Elenbaas L, & Rizzo MT (2018). Young children’s ability to recognize and challenge unfair treatment of others in group contexts. Human Development, 61, 281–296. 10.1159/000492804 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkland K, Jetten J, & Nielsen M (2019). But that’s not fair! The experience of economic inequality from a child’s perspective In: Jetten J, Peters K (eds) The Social Psychology of Inequality. Springer, Cham: 10.10007/978-3-030-28856-3_12 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kraus MW, Côté S, & Keltner D (2010). Social class, contextualism, and empathetic accuracy. Psychological Science, 21, 1716–1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraus MW, Onyeador IN, Daumeyer NM, Rucker J, & Richeson JA (2019). The misperception of racial economic inequality. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 14, 899–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraus MW, Piff PK, Mendoza-Denton R, Rheinschmidt ML, & Keltner D (2012). Social class, solipsism, and contexualism: How the rich are different from the poor. Psychological Review, 119, 546–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunst JR (2017). Preferences for group dominance track and mediate the effects of macro-level social inequality and violence across societies. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114, 5407–5412. 10.1073/pnas.1616572114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leimgruber KL, Shaw A, Santos LR, & Olson KR (2012). Young children are more generous when others are aware of their actions. PloS one, 7, e48292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li V, Spitzer B, & Olson KR (2014). Preschoolers reduce inequality while favoring individuals with more. Child Development, 85, 1123–33. 10.1111/cdev.12198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire L, Rizzo MT, Rutland A, & Killen M (2018a). Deviating from the group: The role of competitive and cooperative contexts. Child Development. 10.1111/cdev.13094 [DOI] [PubMed]

- McGuire L, Rizzo MT, Killen M, & Rutland A (2018b). The development of intergroup resource allocation: The role of cooperative and competitive in-group norms. Developmental Psychology, 54, 1499–1506. 10.1037/dev0000535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLoughlin N, & Over H (2017). Young children are more likely to spontaneously attribute mental states to members of their own group. Psychological Science, 28, 1503–1509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLoughlin N, & Over H (2019). Encouraging children to mentalise about a perceived outgroup increases prosocial behaviour towards outgroup members. Developmental science, 22, doi: e12774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLoughlin N, Tipper SP, & Over H (2018). Young children perceive less humanness in outgroup faces. Developmental Science, 21, e12539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd VC (2019). How children and adolescents think about, make sense of, and respond to economic inequality: Why does it matter? Developmental Psychology, 55, 592–600. 10.1037/dev0000691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulvey KL (2015). Children’s reasoning about exclusion: Balancing many factors. Child Development Perspectives, 10, 22–27. Doi: 10.1111/cdep.12157 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mulvey KL, Rizzo MT, & Killen M (2015). Challenging gender stereotypes: Theory of mind and peer group dynamics. Developmental Science, 19, 999–1010. 10.1111/desc.12345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesdale D (2004). Social identity processes and children’s ethnic prejudice In Bennett M & Sani F (Eds.), The development of the social self (pp. 219–245). East Sussex, England: Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Okonofua JA, & Eberhardt JL (2015). Two strikes: Race and the disciplining of young students. Psychological Science, 26, 617–624. Doi: 10.1177/0956797615570365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson KR, Dweck CS, Spelke ES, & Banaji MR (2011). Children’s responses to group-based inequalities: Perpetuation and rectification. Social Cognition, 29, 270–287. 10.1521/soco.2011.29.3.270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peretz-Lange R & Muentener P (2019). Verbal framing and statistical patterns influence children’s attributions to situational, but not personal, causes for behavior. Cognitive Development, 50, 205–221. 10.1016/j.cogdev.2019.05.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pratto F, Sidanius J, Stallworth LM, & Malle BF (1994). Social dominance orientation: A personality variable predicting social and political attitudes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67, 741. [Google Scholar]

- Reardon SF, & Firebaugh G (2002). 2. Measures of Multigroup Segregation. Sociological Methodology, 32, 33–67. 10.1111/1467-9531.00110 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Renno MP, & Shutts K (2015). Children’s social category-based giving and its correlates: Expectations and preferences, Developmental Psychology, 51, 533–543. 10.1037/a0038819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes M, Leslie SJ, Saunders K, Dunham Y, & Cimpian A (2018). How does social essentialism affect the development of inter-group relations? Developmental Science, 21 e12509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes M, Rizzo M, Foster-Hanson E, Moty K, Leshin R, Wang MM, Benitez J, & Ocampo JD (2020). Advancing developmental science via unmoderated remote research with children. Unpublished Manuscript New York University; https://psyarxiv.com/k2rwy [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridgeway CL (2015). Status construction theory In Stone J, Dennis RM, Rizova P, Smith AD, & Hou X (Eds.), The Wiley Blackwell encyclopedia of race, ethnicity, and nationalism. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Rizzo MT, Elenbaas L, Cooley S, & Killen M (2016). Children’s recognition of fairness and others’ welfare in a resource allocation task: Age related changes. Developmental Psychology, 52, 1307–1317. 10.1037/dev0000134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzo MT, Elenbaas L, & Vanderbilt KE (2018). Children’s responses to individually- and structurally-based resource inequalities. Child Development. 10.1111/cdev.13181 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Rizzo MT & Killen M (2016). Children’s understanding of equity in the context of inequality. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 34, 569–581. 10.1111/bjdp.12150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzo MT & Killen M (2018). How social status influences our understanding of others’ mental states. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 169, 30–41. 10.1016/j.jecp.2017.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts SO & Rizzo MT (2020). The psychology of American racism. American Psychologist. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Rogers LO (2019). Commentary on economic inequality: “What” and “Who” constitutes research on social inequality in developmental science? Developmental Psychology, 55, 586–591, doi: 10.1037/dev0000640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruble DN, Martin CL, & Berenbaum SA (2006). Gender development In Eisenberg N, Damon W, & Lerner RM (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Social, emotional, and personality development (6th ed., Vol. 3, pp. 858–932). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Ruck MD, Mistry RS, & Flanagan CA (2019). Children’s and adolescents’ understanding and experiences of economic inequality: An introduction to the special section. Developmental Psychology, 55, 449–456. http://doi.org/1037/dev0000694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutland A & Killen M (2015). A developmental science approach to reducing prejudice and social exclusion: Intergroup processes, social-cognitive development, and moral reasoning. Social Issues and Policy Review, 9, 121–154. Doi: 10.1111/sipr.12012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt MFH, Svetlova M, Johe J, & Tomasello M (2016). Children’s developing understanding of legitimate reasons for allocating resources unequally. Cognitive Development, 37, 42–52. 10.1016/j.cogdev.2015.11.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw A, & Olson KR (2012). Children discard a resource to avoid inequity. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 141, 382–95. 10.1037/a0025907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw A, Choshen-Hillel S, & Caruso EM (2016). The development of inequity aversion: Understanding when (and why) people give others the bigger piece of the pie. Psychological Science, 27, 1352–1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheskin M, Nadal A, Croom A, Mayer T, Nissel J, & Bloom P (2016). Some equalities are more equal than others: Quality equality emerges later than numerical equality. Child Development, 87, 1520–1528. 10.1111/cdev.12544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smetana JG, Jambon M, & Ball C (2014). The social domain approach to children’s moral and social judgments In Killen M & Smetana JG (Eds.), Handbook of moral development (2nd ed., pp. 23–45). New York, NY: Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Smith CE, Blake PR, & Harris PL (2013). I should but I won’t: Why young children endorse norms of fair sharing but do not follow them. PloS one, 8(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommerville JA, & Ziv T (2018). The developmental origins of infants’ distributive fairness concerns In Gray K & Graham J (Eds.), Atlas of moral psychology (p. 420–429). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Spears-Brown C & Bigler RS (2005). Children’s perceptions of discrimination: A developmental model. Child Development, 76, 533–553. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00862.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel H, & Turner JC (1979). An integrative theory of social conflict. The social psychology of intergroup relations, 2, 33–47. [Google Scholar]

- Turiel E (2002). The culture of morality. NY: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Turiel E (2015). Morality and prosocial judgments and behavior In Schroeder DA & Graziano W (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of prosocial behavior (pp. 137–152). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Vasilyeva N & Ayala S (2019). Structural thinking and epistemic injustice In Sherman BR & Goguen S (Eds.) Overcoming epistemic injustice: Social and psychological perspectives. Rowman & Littlefield International. [Google Scholar]

- Vasilyeva N, Gopnik A, & Lombrozo T (2018). The development of structural thinking about social categories. Developmental Psychology, 54, 1735–1744. 10.1037/dev0000555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M & Roberts SO (2019, October). Social positions shape how beliefs about wealth develop. Poster at CDS 2019 Meeting, Louisville, KY. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson RG, & Pickett KE (2009). Income inequality and social dysfunction. Annual review of sociology, 35, 493–511. [Google Scholar]

- Wörle M & Paulus M (2018). Normative expectations about fairness: The development of a charity norm in preschoolers. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 165, 66–84. https://doi.org/10/1016/j.jecp.2017.03.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]