Abstract

Transected axons typically fail to regenerate in the central nervous system (CNS), resulting in chronic neurological disability in individuals with traumatic brain or spinal cord injury, glaucoma and ischemic reperfusion injury of the eye. Although neuroinflammation is often depicted as detrimental, there is growing evidence that alternatively activated, reparative leukocyte subsets and their products can be deployed to improve neurological outcomes. In the current study we identify a unique granulocyte subset, with characteristics of an immature neutrophil, that had neuroprotective properties and drove CNS axon regeneration in vivo, in part via secretion of a cocktail of growth factors. This pro-regenerative neutrophil promoted repair in the optic nerve and spinal cord, demonstrating its relevance across CNS compartments and neuronal populations. Our findings could ultimately lead to the development of novel immunotherapies that reverse CNS damage and restore lost neurological function across a spectrum of diseases.

Introduction

Axonal transection and neuronal death are pathological features of a wide range of central nervous system (CNS) disorders, including traumatic brain or spinal cord injury, multiple sclerosis, and motor neuron disease. They are also hallmarks of glaucoma and ischemia reperfusion injury of the eye. Protracted disability in individuals with these conditions is due, in large part, to the poor regenerative capacity of the CNS (which includes the retina, optic nerves, brain, brainstem and spinal cord). There is a dire need for novel therapies that not only mitigate, but reverse, chronic neurological deficits. One potential strategy that has been proposed to promote neuroprotection and regeneration involves modulation of the local immune response to CNS damage. Studies in cutaneous wound healing, atherosclerosis, and myocardial infarction, have elucidated alternative immune pathways that most likely evolved to repair bystander tissue damage associated with the clearance of microbial infections1–3. Although CNS-infiltrating, pro-inflammatory leukocytes are detrimental in the context of multiple sclerosis and neuromyelitis optica4, and possibly Alzheimer’s disease and stroke5,6, there is growing evidence that alternatively activated, restorative leukocyte subsets and their products can improve clinical outcomes in a range of neurological disorders7–10. A deeper understanding of the phenotypes of beneficial immune cells, their developmental pathways, and mechanisms of action, could lead to the development of novel neurorestorative immunotherapies.

A classic model of immune-driven CNS axon regeneration involves crush injury to the murine optic nerve, resulting in extensive neuronal loss and axonal transection, that is mitigated by intraocular (i.o.) injection of zymosan, a fungal cell wall extract11,12. Similar to white matter tracts in the brain and spinal cord, transected axons in the optic nerve fail to undergo long distance regeneration. However, i.o. zymosan injection, at the time of optic nerve crush injury (ONC), or up to 3 days afterwards, induces vitreal inflammation associated with rescue of retinal ganglion cells (RGCs, the neurons that give rise to the axons in the optic nerve) from death, and RGC axon regeneration. We previously showed that β−1,3-glucan, a cognate ligand of the innate immune pattern recognition receptor, dectin-1, is the active ingredient in zymosan responsible for its pro-regenerative properties in this model12. We detected dectin-1 on eye-infiltrating myeloid cells, as well as retina-resident microglia and dendritic cells (DCs), in i.o. zymosan-injected mice, but not on RGCs, Muller cells, oligodendrocytes, or astrocytes. The cellular and molecular mediators that trigger neurorepair downstream of dectin-1 signaling are poorly understood. In the current study we identify a unique granulocyte with characteristics of an immature neutrophil, that accumulated in the vitreous fluid in response to i.o. zymosan and exerted neuroprotective and axonogenic effects secondary, in part, to secretion of a cocktail of growth factors. We found that the same myeloid cell subset was capable of driving axon regeneration in the spinal cord, demonstrating its relevance across CNS compartments. A human cell line with characteristics of immature neutrophils also exhibited neuroregenerative capacity, suggesting that our observations might be translatable to the clinic.

Results

Intraocular Ly6Glow neutrophils drive RGC axon regrowth.

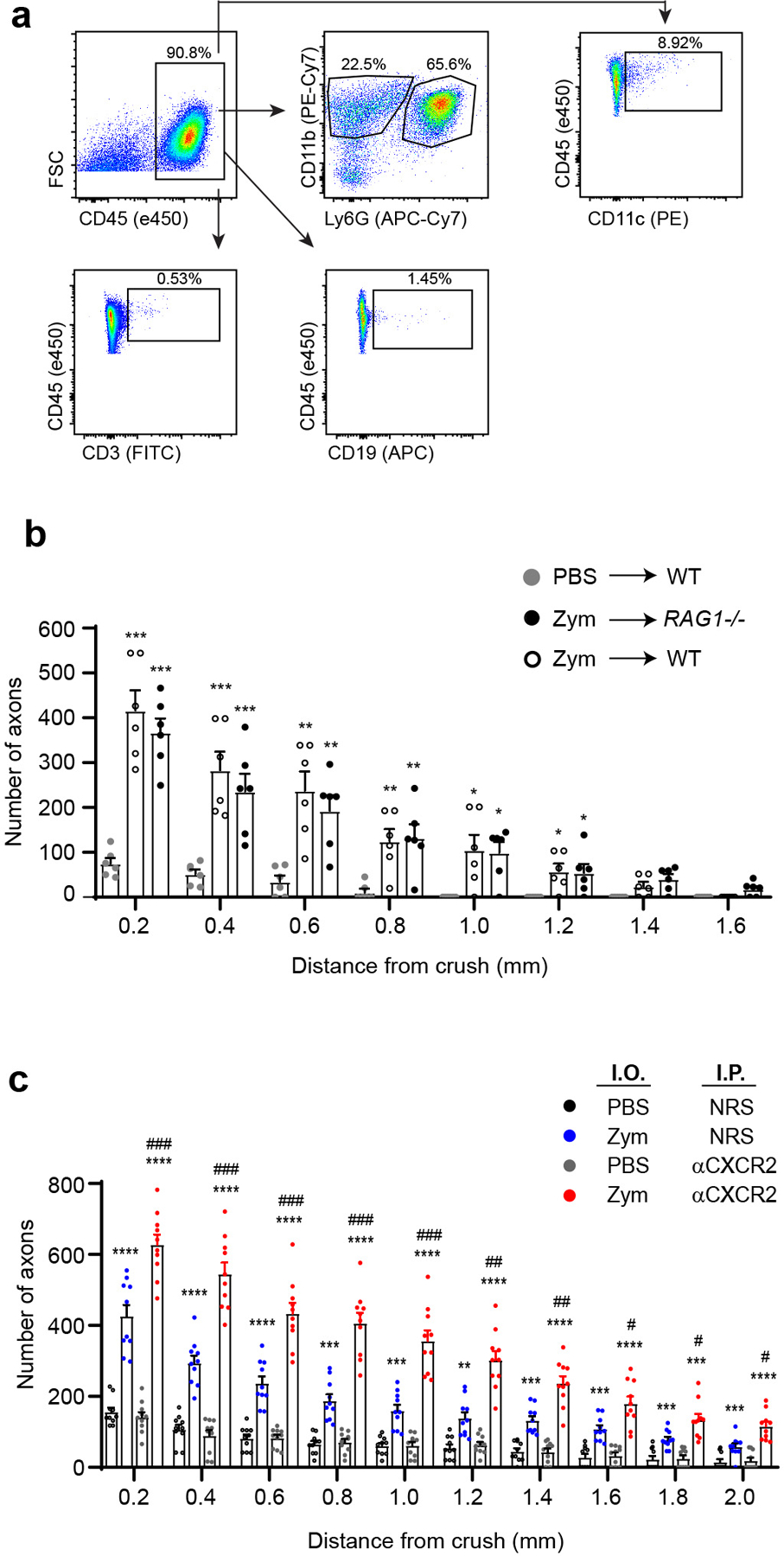

We used flow cytometric analysis to determine the cellular composition of infiltrates that accumulate in the posterior chamber of the eye following i.o. zymosan injection and ONC. (Gating strategy illustrated in Extended Data Fig. 1a). Vitreous fluid was serially collected until day 14 post-ONC, a standard time point when optic nerves are harvested to assess axon regeneration. Myeloid cells (neutrophils and monocytes/macrophages) were predominant at every time point (Fig. 1a, left). Neutrophils outnumbered all other leukocyte subsets from days 1–5 following i.o. zymosan injection, previously established as the critical time window for instigating RGC rescue and axonal regeneration11. Lymphocytes and dendritic cells were minor constituents of the vitreal infiltrates, irrespective of the day of harvest. Intraocular zymosan-driven RGC axon regeneration was unimpaired in Rag1−/− mice, indicating that mature T and B cells are dispensable in this model (Extended Data Fig. 1b).

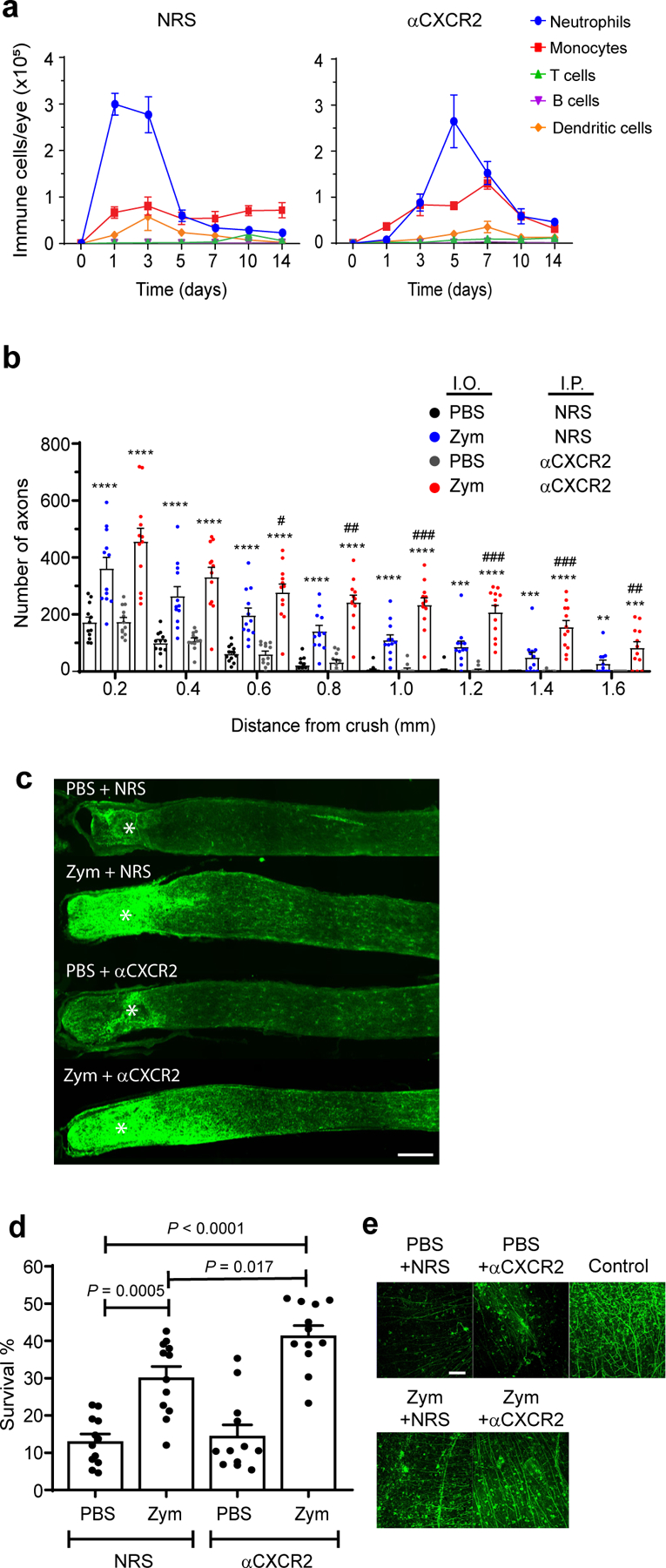

Fig. 1 |. Zymosan-driven regrowth of optic nerve axons is enhanced by blockade of eye-infiltrating CXCR2+ neutrophils.

a-e Mice with ONC injury received a single i.o. injection of zymosan or PBS on day 0, and i.p. injections of either control serum (NRS) or αCXCR2 antisera every other day starting on day 0. a, The cellular composition of vitreal infiltrates collected at serial time points from zymosan injected eyes in the NRS (left) or αCXCR2 (right) treatment groups (n=10 eyes per group per time point). One experiment representative of 7 independent experiments with similar results is shown. b-e, Optic nerves and retinas were harvested on day 14. b, The density of GAP-43+ regenerating axons in longitudinal optic nerve sections at serial distances from the crush site (n= 12 nerves per group), scale bar 200 μm. One experiment representative of 3 is shown. c, Representative images of optic nerves from each group in one experiment from b. d, The frequency of viable BRN3a+ retinal ganglion cell (RGC) neurons in whole mounts, normalized to healthy retina (n=12 retinas per group). One experiment representative of 3 is shown. e, Representative images of retinal whole mounts from each group in one experiment from d. “Control” indicates a healthy, naive retina, scale bar 100 μm. In a,b,d, data are shown as mean +/− sem; statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 compared with i.o. PBS/ i.p. NRS group; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001, compared with i.o. zymosan/ i.p. NRS group).

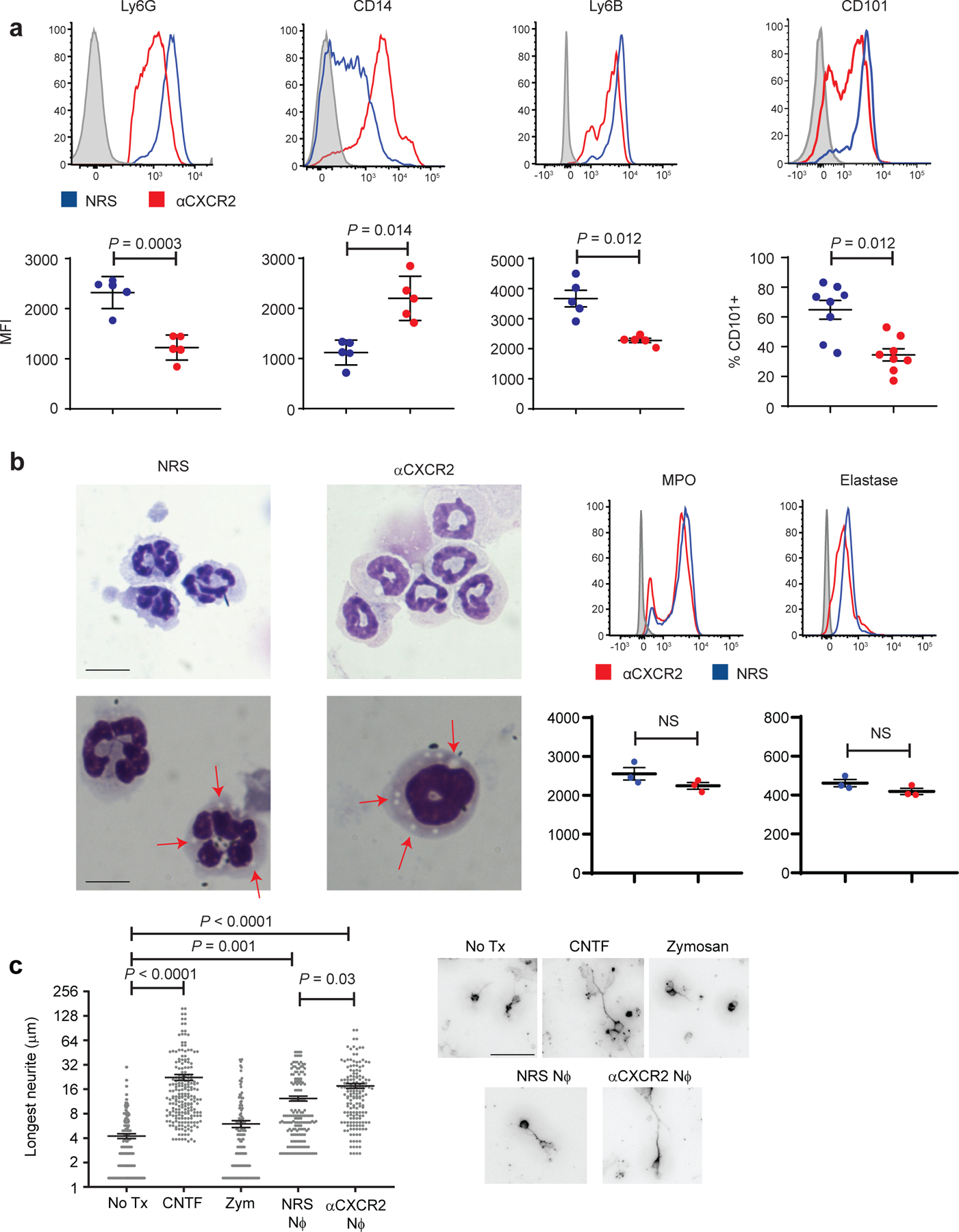

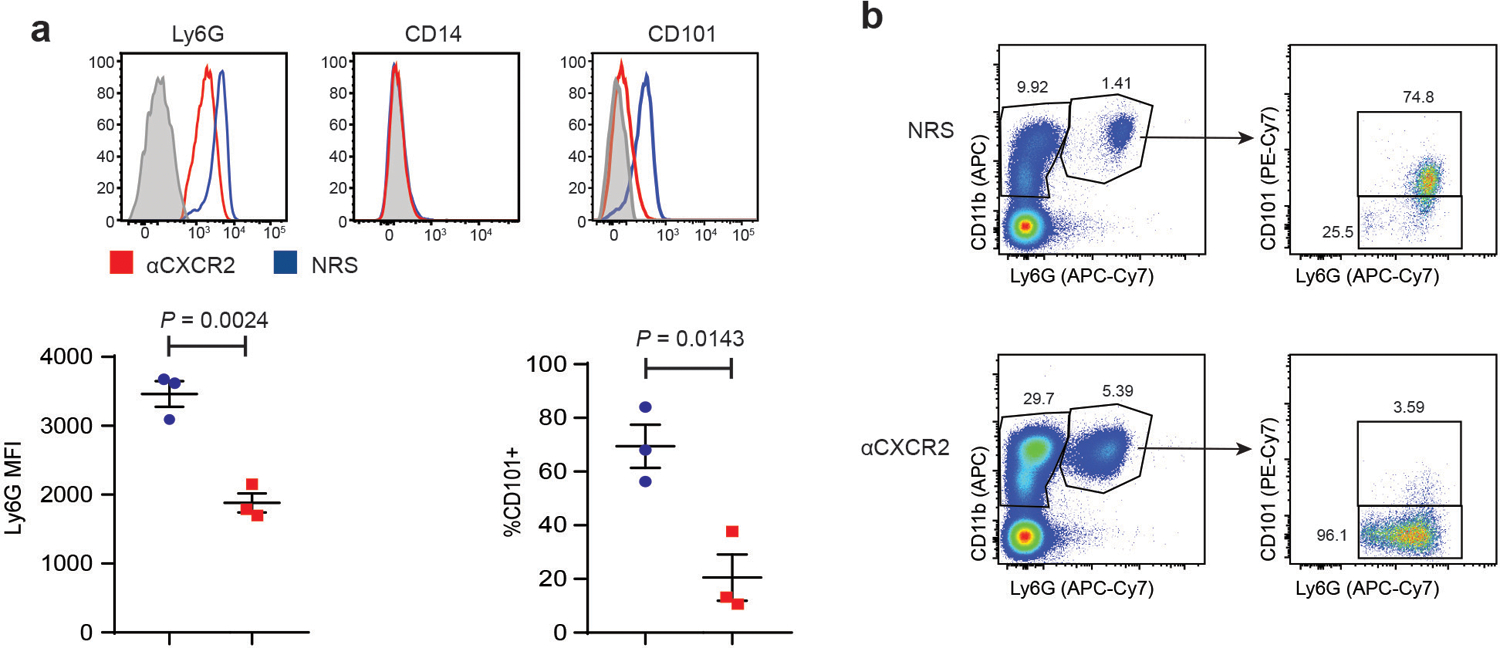

To assess the contribution of neutrophils, we attempted to impede their entry into the posterior chamber of the eye with a blocking antisera against CXCR2, the predominant chemokine receptor expressed by mature murine neutrophils. Unexpectedly, systemic administration of anti-CXCR2, from the day of ONC/ i.o. zymosan injection onward, significantly enhanced RGC survival and axon regeneration (Fig. 1b–e). The augmentation of axonal regeneration by administration of anti-CXCR2 was sustained through day 28 following ONC injury/ i.o. zymosan injection (Extended Data Fig. 1c), with some axons reaching the optic chiasm (data not shown). Flow cytometric analyses revealed that i.o. neutrophil accumulation was delayed, but not prevented, in the anti-CXCR2 treated cohort, such that the number of neutrophils peaked on day 5 rather than days 1–3 (Fig. 1a, right). The peak of i.o. monocyte and dendritic cell accumulation was delayed until day 7. Furthermore, the characteristics of the infiltrating leukocyte population were altered. Intraocular inflammatory cells, isolated between days 3 through 7 post ONC/ i.o. zymosan and anti-CXCR2 treatment, contained an expanded subpopulation of CD11b+ myeloid cells that express relatively low amounts of Ly6G and Ly6B, and relatively high expression of CD14, when compared with i.o. infiltrates isolated from the mice treated with control sera (Fig. 2a). The majority of these Ly6Glow CD14hi cells had ring-shaped nuclei and are CD101−/low, indicative of an immature neutrophil phenotype (Fig. 2a,b). In contrast, their Ly6Ghi CD14low counterparts (the most populous subset in the control group), universally had segmented nuclei and were CD101hi, consistent with conventional mature neutrophils. Both Ly6GlowCD14hi and Ly6GhiCD14low cells possessed cytoplasmic granules, and expressed comparable amounts of elastase and myeloperoxidase (Fig. 2b). Intraocular Ly6G+ cells, isolated 5 days following ONC/ i.o. zymosan and anti-CXCR2 treatment, directly stimulated the neurite outgrowth of primary RGC in vitro (Fig. 2c). The frequency of Ly6GlowCD101−/low myeloid cells was elevated in the blood and spleen of the anti-CXCR2 treated cohort, suggesting that the combination of i.o. zymosan administration and CXCR2 blockade accelerates mobilization of immature neutrophils from the bone marrow to the circulation, from where they are recruited to the eye (Extended Data Fig. 2, and data not shown). These results implicate a subpopulation of immature neutrophils in i.o. zymosan-induced optic nerve axon regeneration.

Fig. 2 |. Treatment of mice with αCXCR2 antisera, starting on the day of i.o. zymosan injection, skews eye-infiltrating neutrophils towards an immature phenotype.

a-c Mice were injected i.o. with zymosan on day 0 of ONC injury, and i.p. with either αCXCR2 (red) or NRS (blue) on days 0, 2 and 4. Inflammatory cells were isolated from the vitreous on day 5. a, b Surface expression of myeloid cell markers. Upper panels, representative histograms. Lower panels, geometic Mean Fluorescence Intensity of Ly6G (n=5 mice/group), CD14 (n=5 mice/group), Ly6B (n=5 mice/group), MPO and elastase on Ly6G+ gated cells ( (n=3 mice/group), and % of Ly6G+ gated cells that are CD101+(n=8 mice/group). Each symbol represents data obtained from a single mouse. One experiment representative of 3 is shown. Statistical significance determined by two tailed unpaired Student’s t-test. b, left panels, Cytospins of purified vitreal Ly6G+ cells, Wright Giemsa stained (top panels scale bar 10 μm, bottom panels scale bar 6 μm). Arrows point to granules. c, Mean length of the longest neurite grown by primary RGC, following 24 h co-culture with intraocular Ly6G+ neutrophils (Nϕ) that were purified from the NRS or αCXCR2 treatment groups. RGC were cultured with recombinant ciliary neurotrophic factor (CNTF) as a positive control, or with particulate zymosan (Zym) or media alone (No Tx) as negative controls (n= 200 RGCs per condition). Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. Right panels, representative images, scale bar 20 μm. a, b, c, Data are shown as mean +/− sem.

Transcriptome profiling of intraocular Ly6Glow cells.

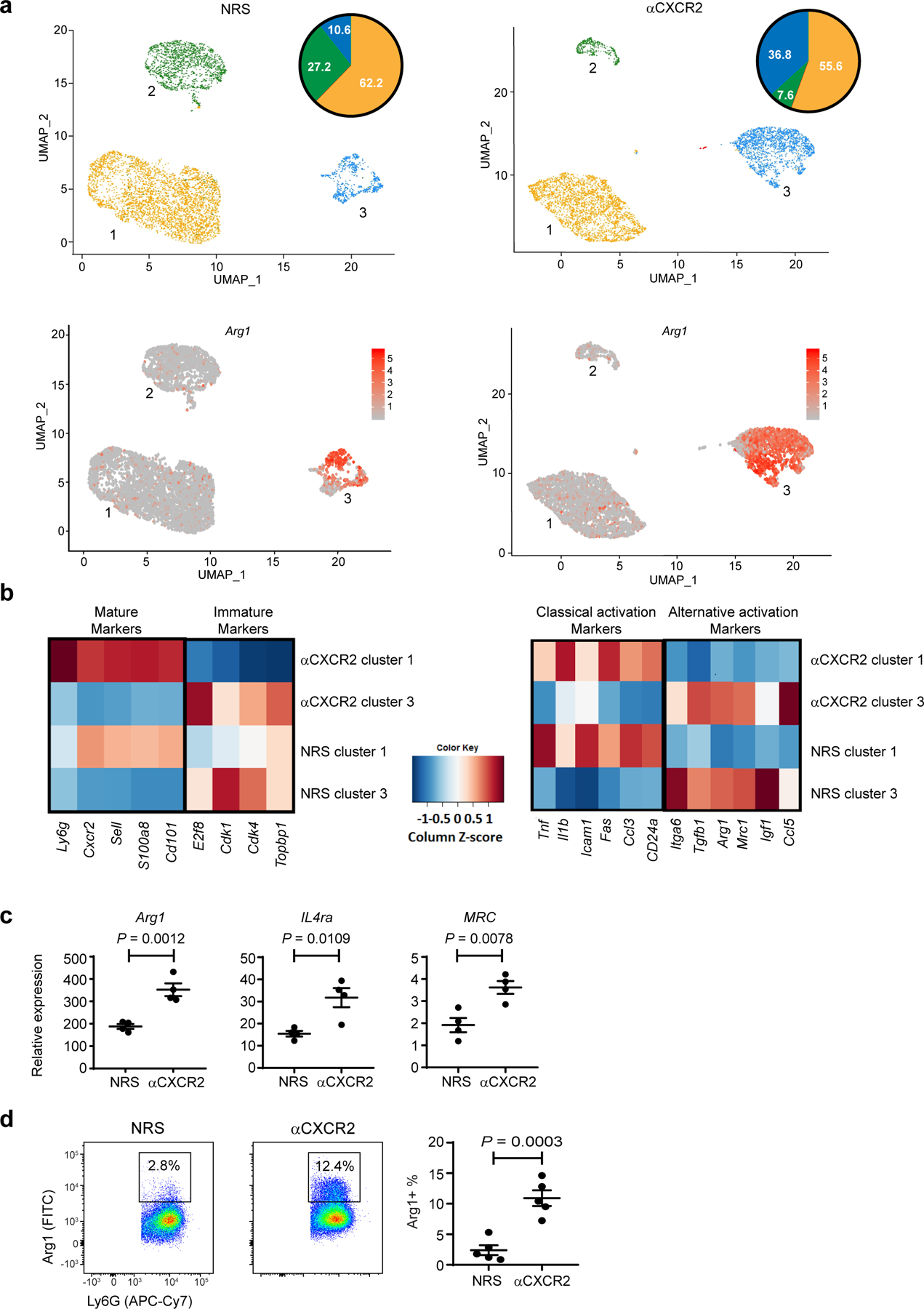

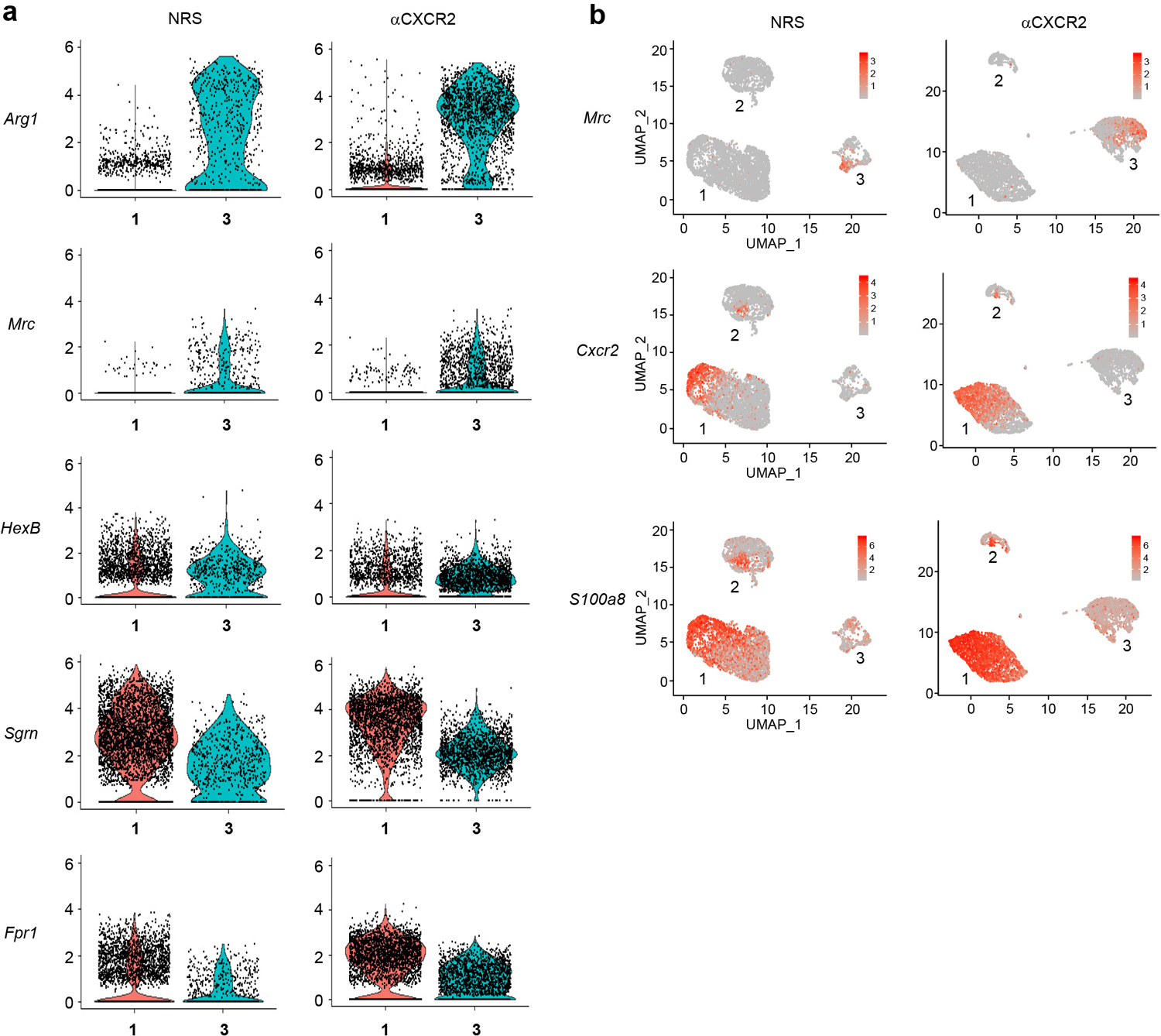

For in-depth analysis, we purified Ly6G+ cells from the vitreous of mice five days following i.o. zymosan injection and treatment with either anti-CXCR2 or control sera. Whole transcriptome, single-cell RNA-sequencing (scRNA-Seq) was then performed. Three distinct clusters were observed in the single cell datasets derived from either the anti-CXCR2 or control antibody treated groups, with profiles indicative of immature (cluster 3), intermediate (cluster 2), or mature (cluster 1) stages of neutrophil development (Fig. 3a,b, heat map on left). Consistent with our flow cytometry data, the percentage of intraocular Ly6G+ cells that fell within the immature neutrophil cluster was more than 3 fold higher in mice treated with anti-CXCR2 compared with mice treated with control sera (36.8% versus 10.6%, respectively). These results confirm that RGC axon regrowth is associated with the accumulation of immature neutrophils close to the site of nerve injury.

Fig. 3 |. Neuroregenerative neutrophils have characteristics of alternatively activated cells.

a-d, Mice with ONC injury were injected i.o. with zymosan on day 0, and i.p. with αCXCR2 or NRS on days 0, 2, and 4. Ly6G+ cells were purified from intraocular infiltrates on day 5. a,b, Single cell analysis of pooled intraocular Ly6G+ cells from the NRS (left panels) or αCXCR2 (right panels) treatment groups, using 10X Genomics (n= 5 mice/ group). a, Upper panels, UMAPs showing 5,909 cells (left, NRS treatment group) and 4,844 cells (right, αCXCR2 treatment group) by cluster. Pie charts indicate the percent of cells in each cluster. Lower panels, featureplots showing cluster-specific expression of arginase-1 (Arg1). b, Heat maps depicting the scaled expression of genes related to neutrophil maturation (left) and classical or alternative activation markers (right). c, RNA was extracted from Ly6G+ cells purified from the intraocular infiltrates of individual mice. Arg1, IL-4 receptor alpha chain (IL4Ra), and CD206/ mannose receptor (MRC) transcripts were quantified by qPCR, and normalized to β-actin (n=4 mice/ group). One experiment representative of 3 independent experiments is shown. d, Representative flow cytometric dot plots showing intracellular Arginase-1 protein expression in Ly6G+ gated cells. Right panel, percent of Ly6G+ cells that are Arginase-1+ (n=5 mice/group). One experiment representative of 2 is shown. c, d Each symbol represents the results obtained from an individual mouse. Data are show as mean +/− sem. Statistical significance was determined by two tailed unpaired Student’s t-test.

Zymosan-induced Ly6Glow cells are alternatively activated.

Novel subpopulations of neutrophils were recently described in animal models of cancer, myocardial infarction, and infection. “N2” neutrophils, that express arginase-1, VEGFα and bear a ring-form nucleus, were initially identified in intratumor infiltrates13. These cells are distinct from conventional “N1” neutrophils which express pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, and bear a multi-segmented nucleus. Enrichment of N2 neutrophils in the tumor bed is associated with impaired anti-tumor immunity and accelerated tumor growth. Unconventional neutrophils with features similar to N2 cells have subsequently been described in animal models of helminth and staphylococcus infection, stroke, and myocardial infarction14–16. In all of these models unconventional neutrophils are characterized by ring form nuclei, as well as expression of genes encoding Type 2 cytokines (Il4, Il5 and/ or Il13 mRNA) and genes traditionally associated with alternatively activated “M2” macrophages (such as Arg1/ arginase-1, Mrc1/CD206, Il4ra/IL-4 receptor α chain, Itga6/VLA-6, Tgfb1/TGF-β1, Igf1/ Insulin-like growth factor 1, and Ccl5 ). However, the ability of alternatively activated neutrophil subsets to induce neuroprotection and neuroregeneration has yet to be demonstrated.

Reminiscent of the “N2” and the other alternatively activated neutrophils described above, Ly6Glow cells, purified from the vitreous fluid of mice on day 5 post-ONC/i.o. zymosan/αCXCR2 treatment, exhibited elevated abundance of transcripts for Arg1, Mrc1, and Il4ra relative to their Ly6Ghi counterparts (Fig. 3c). Furthermore, a significant percentage of those cells expressed arginase-1 protein (Fig. 3d). Consistent with these results, single-cell RNA sequencing of intraocular Ly6G+ cells revealed that transcripts for Arg1 and Mrc1, as well as Itga6, Tgfb1, Igf1, and Ccl5, were enriched in the immature neutrophil subset (cluster 3) that was expanded in the αCXCR2-treated cohort (Fig. 3a, bottom; 3b heat map, right, and Extended Data Fig. 3). Thus, zymosan-induced Ly6Glow neutrophils have characteristics of an alternatively activated myeloid cell.

Donor Ly6Glow cells promote RGC survival and axon regrowth.

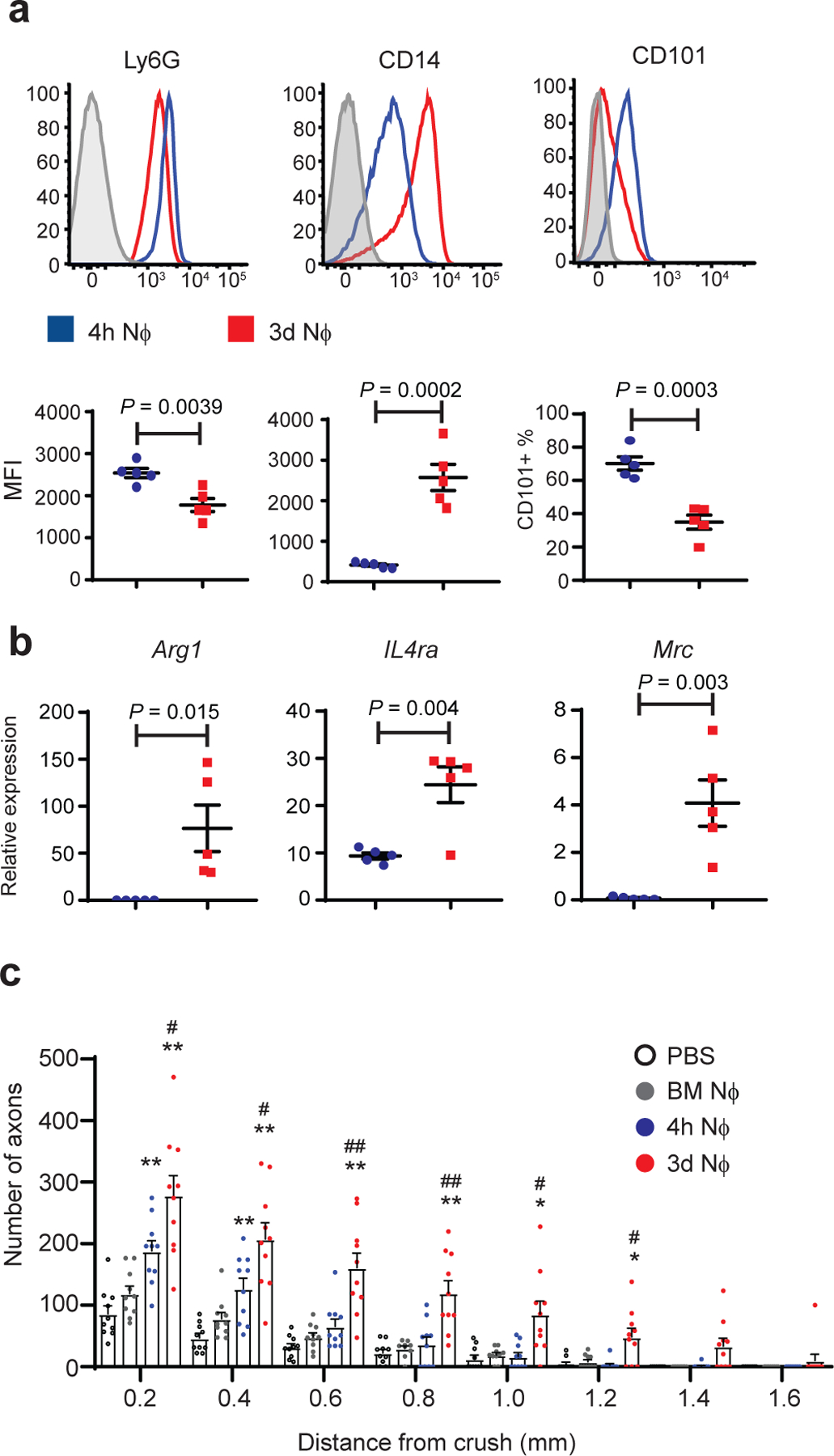

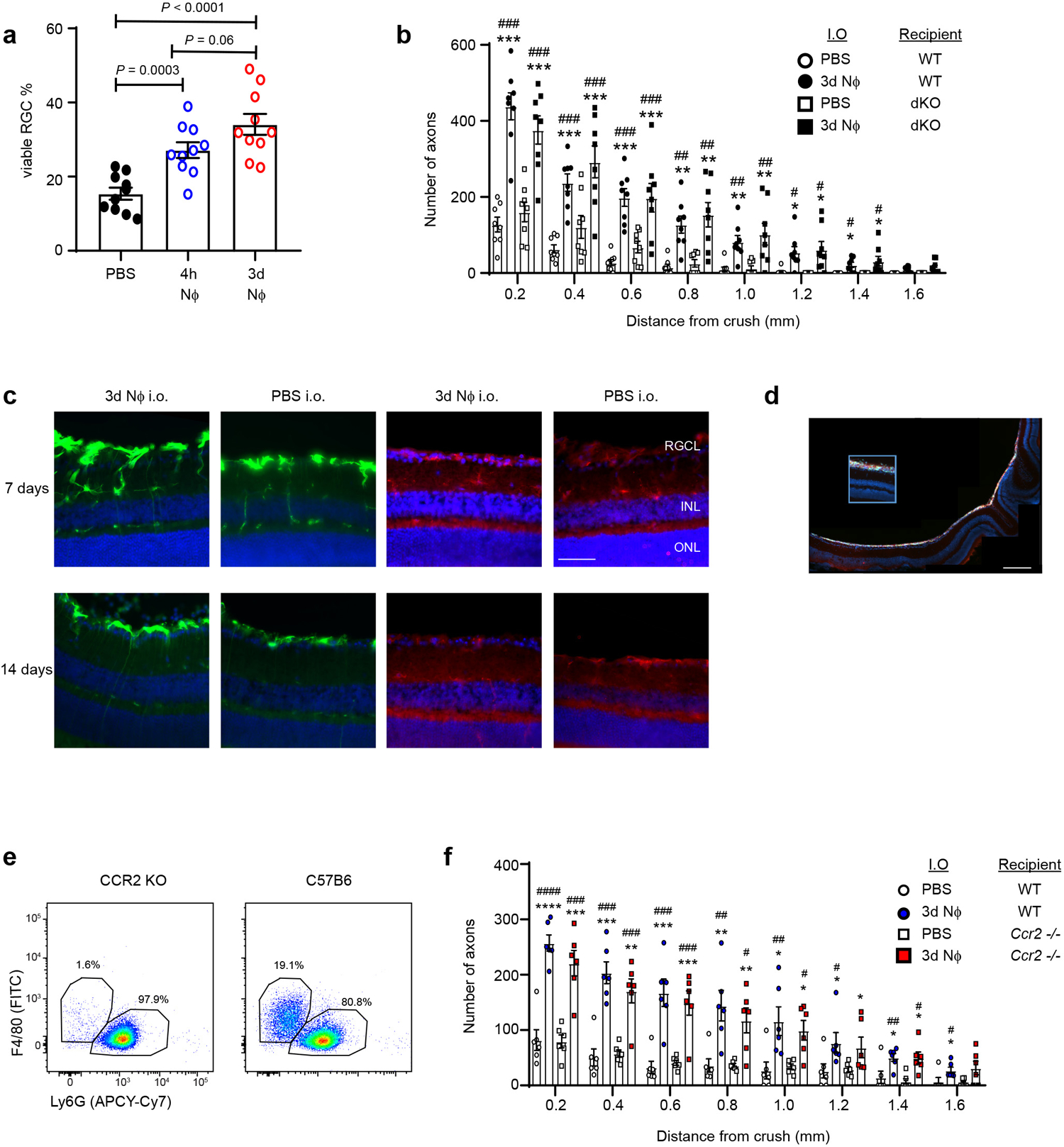

We used an adoptive transfer approach to directly evaluate the neuroprotective and pro-regenerative potential of zymosan-elicited Ly6Glow neutrophils in vivo. The low yield of Ly6Glow cells sorted from vitreal infiltrates of i.o. zymosan injected mice prohibits adoptive transfer experiments with those cells. As an alternative approach, we isolated Ly6G+ cells from the peritoneal cavities of naive mice at serial time points following intraperitoneal injection of zymosan, and characterized them by flow cytometric analysis and quantitative RT-PCR. We found that neutrophils isolated on day 3 post i.p. zymosan injection (3d Nϕ) simulated a number of the properties of the pro-regenerative neutrophils harvested from the eyes of the i.o. zymosan/ anti-CXCR2 treatment group, including relatively low expression of cell surface Ly6G and CD101, high expression of cell surface CD14, and high expression of Arg1, Il4ra, and Mrc1 transcripts (Fig. 4a,b). In contrast, neutrophils isolated from the peritoneal cavity of mice 4 h following i.p. zymosan injection (4h Nϕ) resembled conventional mature neutrophils in that they were Ly6GhiCD14lowCD101hi and expressed undetectable to low amounts of Arg1, Il4ra, and Mr1c transcripts.

Fig. 4 |. CD14+Ly6Glow cells, purified 3 days following i.p. zymosan injection, are neuroregenerative.

Peritoneal cells were harvested via lavage 4 hours (blue) or 3 days (red) following i.p. zymosan injection. a, Cell surface expression of indicated molecules on Ly6G gated cells. Upper panels, representative histograms. Lower panels, geometric Mean Fluorescence Intensity of Ly6G and CD14; % of cells that are CD101+(n=5 mice/group) One of 3 independent experiments shown. b, RNA was extracted from purified Ly6G+ cells. Arg1, IL4Ra, and MRC, measured by qPCR normalized to Actβ (n=5 mice/group) One of 3 independent experiments shown. c, Ly6G+ cells (NΦ), purified from zymosan-induced i.p. infiltrates, were adoptively transferred into the eyes of mice on days 0 and 3 post ONC injury. For negative controls, separate groups of mice were injected i.o. with PBS or naïve bone marrow neutrophils (BMNϕ) according to the same dosing regimen. Optic nerves were harvested 14 days later and analyzed by GAP-43 immunohistochemistry. The figure shows the density of regenerating axons in optic nerve sections, at serial distances from the crush site (n= 10 nerves per group). One experiment representative of 4 is shown. Statistical significance determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01 compared with PBS; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, compared with 4 hour NΦ). a,b Each symbol represents data obtained using inflammatory cells pooled from both eyes of a single mouse. Error bars depict mean +/− sem for all data sets.

When injected into the eyes of wild-type mice with ONC injury, 3d Nϕ induced robust RGC survival and axonal regeneration, while 4h Nϕ were less effective, and naïve bone marrow neutrophils (BM Nϕ) had no significant impact (Fig. 4c, Extended Data Fig. 4a, and data not shown). 3d Nϕ promoted RGC axon regeneration in mice genetically deficient in the zymosan receptors, dectin-1 and TLR2, ruling out the possibility that free zymosan particles (either inadvertently co-transferred with donor neutrophils, or released into the vitreous by dying donor neutrophils), are responsible for their pro-regenerative effect (Extended Data Fig. 4b). Intraocular transfer of 3d Nϕ was still capable of triggering RGC axon regeneration when delayed by 6 h (and to some extent, up to 12 h) from ONC injury, demonstrating a therapeutic window that extends beyond the time of the acute traumatic event (Extended Data Fig. 5a).

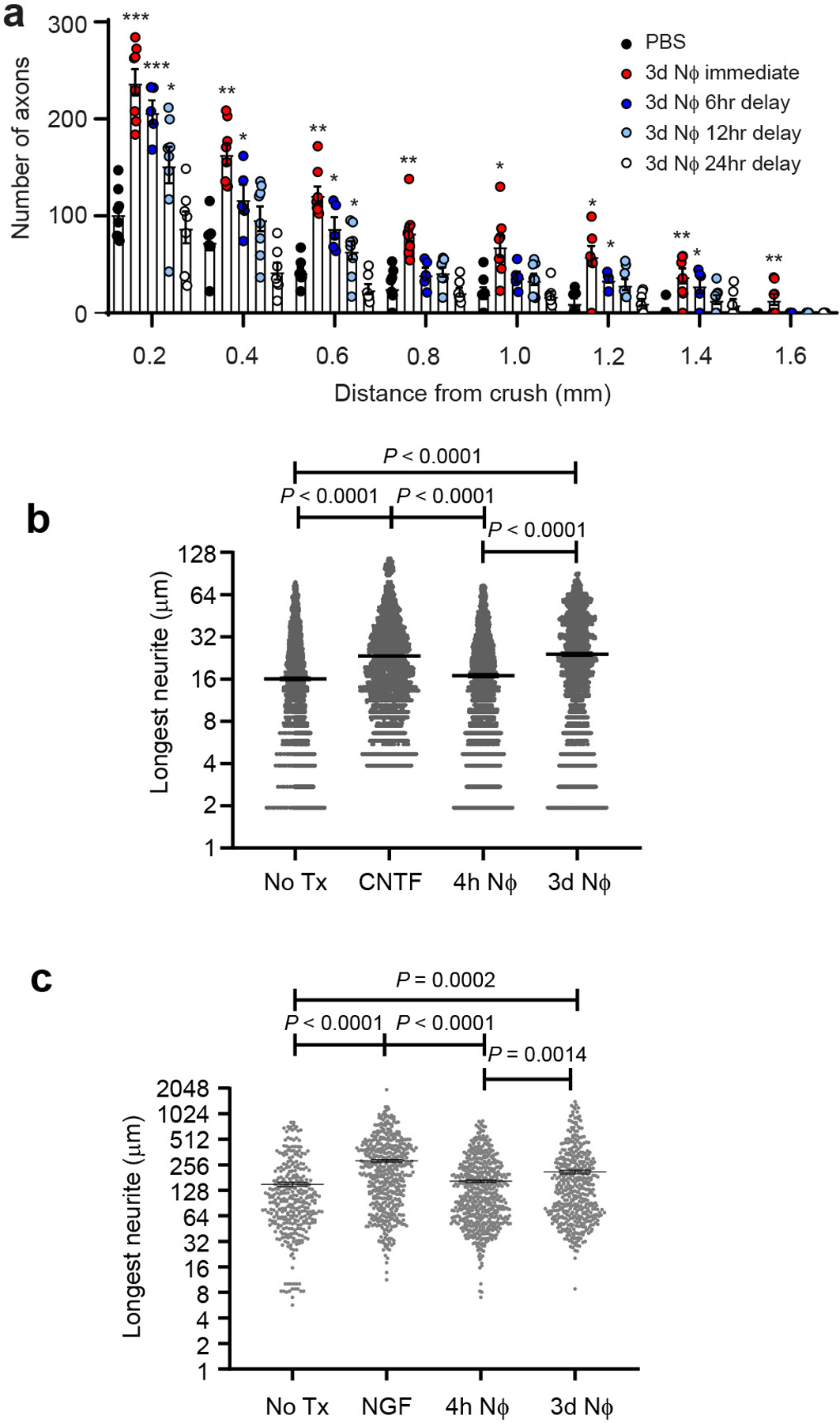

Intraocular injection of 3d Nϕ (and, to a lesser extent, PBS) resulted in upregulation of GFAP and Iba-1 staining in retinal cross-sections obtained from mice with ONC injury (Extended Data Fig. 4c). Enhanced Iba-1 staining is consistent with activation of retinal microglia, which we previously reported occurs in response to ONC injury alone12. Both GFAP and Iba-1 expression waned by 14 days post-transfer and, at that point, was comparable between the groups injected with 3d Nϕ versus PBS. 3d Nϕ transfers triggered the secondary recruitment of host monocytes from the periphery via a CCR2 dependent pathway (Extended Data Fig. 4e). Alternatively activated neutrophils have been shown to polarize monocyte/ macrophages towards a reparative and/ or pro-resolving phenotype that enhances healing in animal models of helminth infection, myocardial infarction and acetaminophen-induced liver injury14,17,18. However, 3d Nϕ promoted axon regeneration in Ccr2−/− hosts, independent of i.o. monocyte/ macrophage infiltration (Extended Data Fig. 4e, f). This finding is consistent with the ability of highly purified 3d Nϕ to directly induce neurite outgrowth of RGC in culture, in the absence of other myeloid cell subsets (Fig. 5a). 3d Nϕ were still able to induce neurite outgrowth when added to dissociated RGCs 4 h after the neurons were plated, providing further evidence that neurons remain responsive to the regenerative properties of alternatively activated neutrophils in a therapeutic paradigm (Extended data Fig. 5b). Collectively, these data demonstrate that zymosan-modulated Ly6Glow neutrophils directly stimulate the regeneration of transected optic nerve axons in vivo, and are capable of doing so after a significant delay from the time of acute injury.

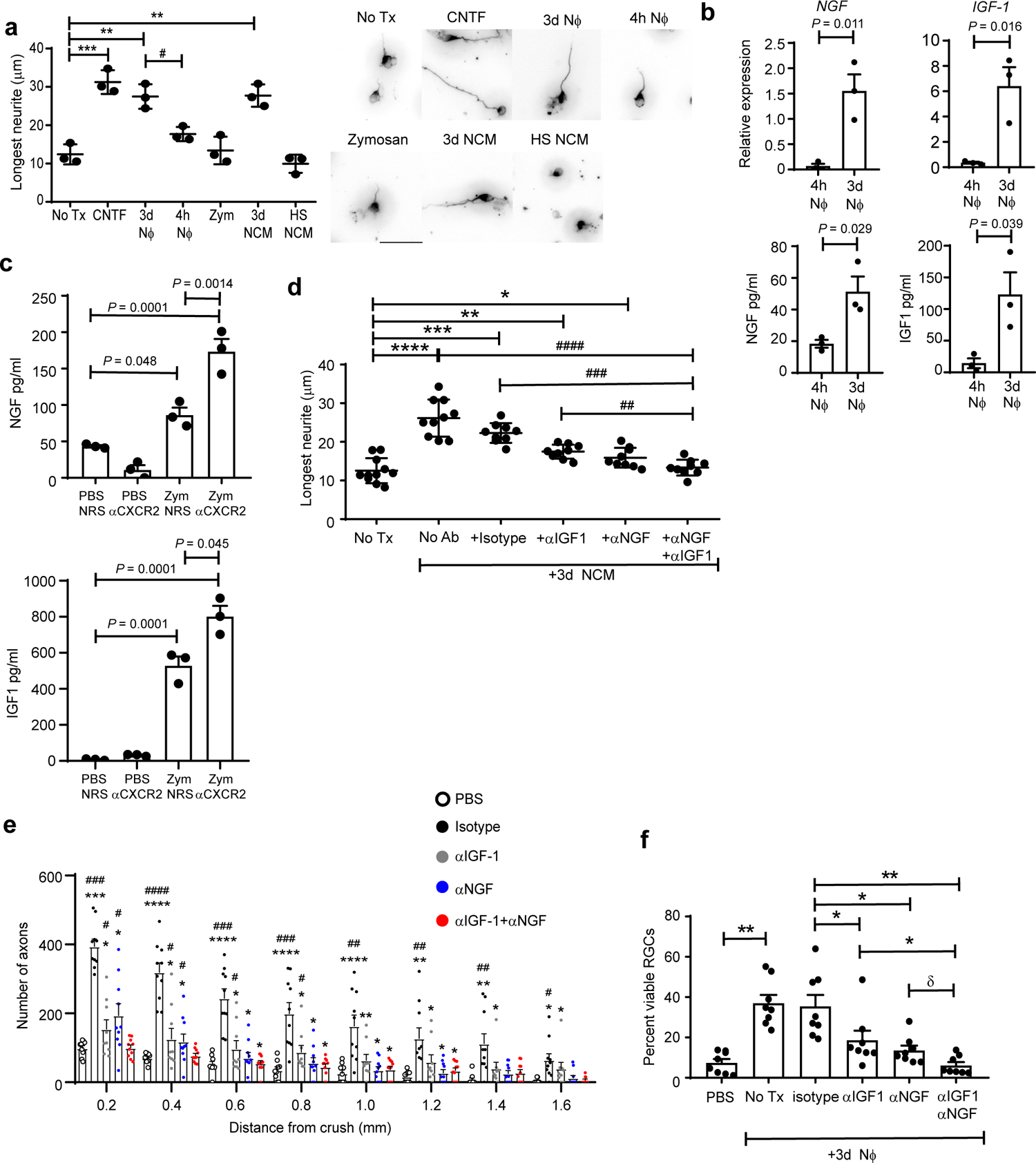

Fig. 5 |. CD14+Ly6Glow cells induce RGC axon outgrowth, in part, via secretion of growth factors.

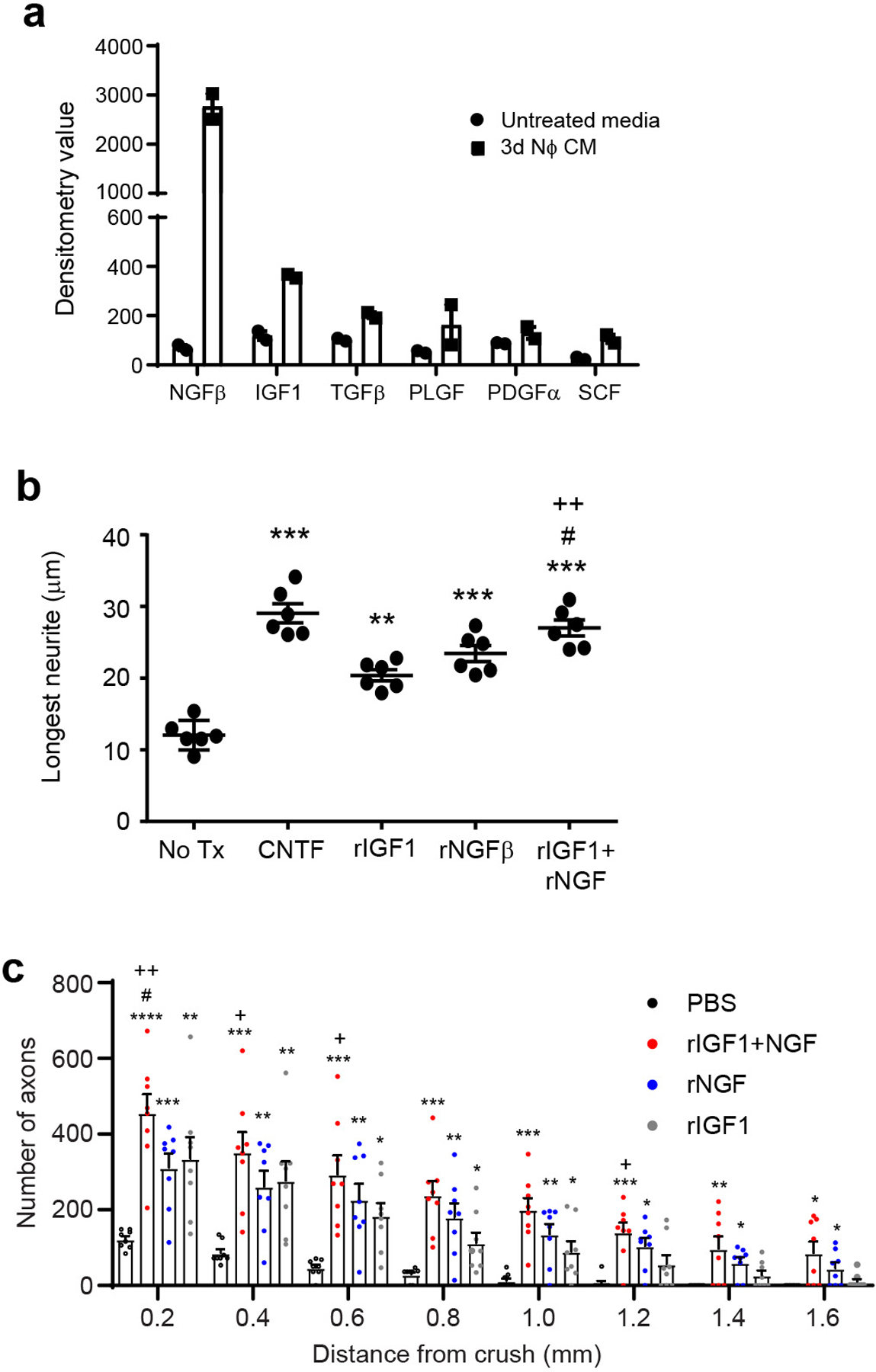

a-d, Ly6G+ cells were purified from peritoneal lavage fluid that was collected 4 hours (4h NΦ) or 3 days (3d NΦ) following i.p. zymosan injection. a, 3d NΦ, 4h NΦ, the conditioned media of 3d NΦ (3d NCM), or heat shocked conditioned media of 3d NΦ (HS NCM), were added to primary RGC cultures, and neurite outgrowth was measured 24 hours later. RGCs were cultured with recombinant CNTF or particulate zymosan (Zym) as positive and negative controls, respectively. Each circle represents the mean neurite length of 200 RGCs countedin one experiment, n=3 independent experiments. Statistical significance determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. Right panels, representative images. b, Upper panels, NGF and IGF-1 mRNA levels in 4h or 3d NΦ, quantified using qPCR, and normalized to Actβ. Lower panels, NGF and IGF-1 protein levels, measured in the CM of 4h or 3d NΦ by ELISA. c, NGF and IGF-1 protein levels, measured by ELISA, in vitreous fluid collected on day 5 following ONC injury and i.o. zymosan or PBS injection. Mice were injected i.p. with either NRS or αCXCR2 on days 0, 2 and 4 post-ONC injury. b,c Statistical significance determined using the two tailed unpaired Student’s t-test (n= 3 mice/group). One of two experiments shown. d, Primary RGC were cultured with conditioned media of 3d NΦ, in the absence or presence of neutralizing antibodies against NGF and/ or IGF-1, or isotype matched control antibodies. Neurite length was measured 24 hours later. Each symbol represents the mean neurite length of 100 RGCs counted in one independent experiment; n=10 experiments. Statistical significance determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. e,f, Purified 3d NΦ were adoptively transferred, with or without neutralizing antibodies against NGF and/ or IGF-1 or isotype matched control antibodies, into the eyes of mice with ONC injury, as in fig. 4c. A negative control group was injected with PBS alone. Optic nerves and retinas were harvested 14 days later. e, Density of regenerating axons in optic nerve sections, at serial distances from the crush site. (n= 10 nerves per group). One experiment representative of 3 shown. Statistical significance determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 compared with PBS; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 compared with αNGF+αIGF-1). f, Frequency of viable BRN3a+ RGC neurons in whole mounts, normalized to healthy retina (n=10 retina per group). One experiment representative of 2 shown. Statistical significance determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. a, d, f, *, #P < 0.05, **, ##P < 0.01, ***, ###P < 0.001, ****, ####P < 0.0001, δ P=.058. a-f, Error bars depict mean +/− sem.

Ly6Glow neutrophils secrete an array of growth factors.

Conditioned culture media harvested from 3d Nϕ (3d NCM) promoted neurite outgrowth of primary RGCs, indicating that soluble factors are, at least in part, responsible for the pro-regenerative properties of 3d Nϕ (Fig. 5a). The neurite growth-promoting effect of NCM was heat sensitive, suggesting that proteins were responsible for this activity. We performed a multiplexed antibody array assay to screen NCM for a panel of candidate growth factors. Nerve growth factor (NGF) and insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1) were highly elevated in NCM versus unconditioned media (Extended Data Fig. 6a). High expression of NGF and IGF1 by 3d Nϕ, in comparison to 4h Nϕ, were corroborated by qRT-PCR and ELISA (Fig. 5b). NGF and IGF-1 proteins were readily detectable in the vitreous on days 3 and 5 following i.o. zymosan injection, and their abundance was enhanced by the administration of αCXCR2 antisera (Fig. 5c).

Neutralization of either NGF or IGF-1 with antagonistic antibodies mitigated NCM-driven RGC neurite outgrowth in vitro (Fig. 5d). Neutralization of both growth factors together had a greater impact than blocking either one alone. Similarly, i.o. administration of either anti-NGF or anti-IGF-1 neutralizing antibody, at the time of 3d Nϕ adoptive transfer, impeded RGC protection and axon regeneration in vivo; administration of both antibodies had an additive effect (Fig. 5e,f). Conversely, recombinant NGF and IGF-1 acted in a collaborative fashion to promote RGC neurite outgrowth in vitro and RGC axon regeneration in vivo (Extended Data, Fig. 6b,c). These findings indicate that zymosan-modulated Ly6Glow neutrophils promote neuronal survival and axon regeneration, in part, via secretion of NGF and IGF1.

Ly6Glow cells drive repair in the spinal cord.

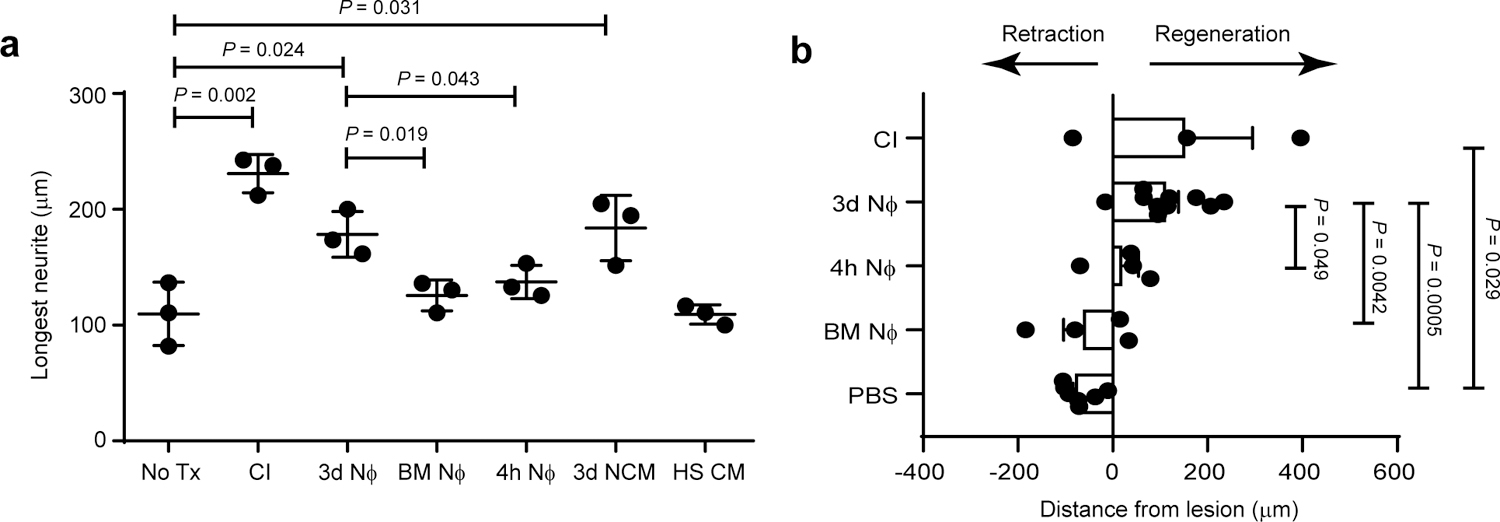

To determine whether the neuroregenerative effects of Ly6Glow neutrophils are limited to RGCs and the microenvironment of the eye, or are more broadly applicable, we assessed their effects on dorsal root ganglia (DRG) cells. Importantly, 3d Nϕ stimulated axon outgrowth of primary DRG neurons when added at the initiation of culture or up to 8 h later, whereas naïve bone marrow neutrophils and 4h Nϕ were ineffectual (Fig. 6a; Extended Data Fig. 5c). The conditioned media of 3d Nϕ also induced neurite outgrowth of DRG (Fig. 6a). In order to test the regenerative potential of alternatively activated neutrophils in the setting of traumatic spinal cord injury (SCI), we injected 3d Nϕ, 4h Nϕ, naïve bone marrow neutrophils, or PBS alone, into sciatic nerves 5 days before laceration of spinal cord dorsal columns at the T4 level. For a positive control, a separate group of mice was subjected to conditioning injury (ie, sciatic nerve crush) 5 days prior to SCI, which is a widely used method for priming the regeneration of severed dorsal column axons19. Spinal cords were harvested from all groups on day 52 post-SCI and subjected to immunohistological analysis. We found severed dorsal column axons retracted proximally, away from the injury site, in the groups of mice that had been injected in the sciatic nerves with either vehicle or bone marrow neutrophils (Fig. 6b). Administration of 4h Nϕ prevented axonal retraction, but did not trigger regeneration past the injury site. Conversely, severed axons regrew rostrally in the mice that had been injected with 3d Nϕ, passing beyond the injury site by a distance commensurate to that reached by axons in mice subjected to a conditioning injury. Thus, 3d Nϕ displayed neuroprotective and pro-regenerative functions in several CNS compartments, namely the optic nerve and the spinal cord.

Fig. 6 |. CD14+Ly6Glow cells drive the regeneration of spinal cord axons.

a, Primary DRG neurons were cultured alone (No Tx), or with 3 day neutrophils (3d NΦ), 4 hour neutrophils (4h NΦ), bone marrow neutrophils (BM NΦ), conditioned media from 3d NΦ cultures (3d NCM), or heat shocked 3d NCM (HS CM). For a positive control, DRGs were harvested 5 days following conditioning injury (CI) to the sciatic nerve. Neurite length was measured 24 hours later. Each symbol represents the mean of 50 DRGs counted in one independent experiment; n=3 independent experiments. Statistical significance determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. b, Bilateral sciatic nerves were injected with either 3d NΦ, 4h NΦ, BM NΦ, or PBS, 5 days prior to spinal cord (SC) dorsal column transection. For a positive control, a separate group of mice was subjected to conditioning injury (CI) of the sciatic nerves 5 days prior to the SC transection. Sagittal sections of the spinal cord were obtained 52 days following SC transection, and subjected to immunohistochemistry. The data show the average distance between the lesion center and the rostral tip of regenerating axons. n= 7 (PBS injection), 4 (BM NΦ), 4 (4h NΦ), 10 (3d NΦ), and 3 (CI). One experiment representative of 2 is shown. Statistical significance determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. a,b Data shown as mean +/− sem.

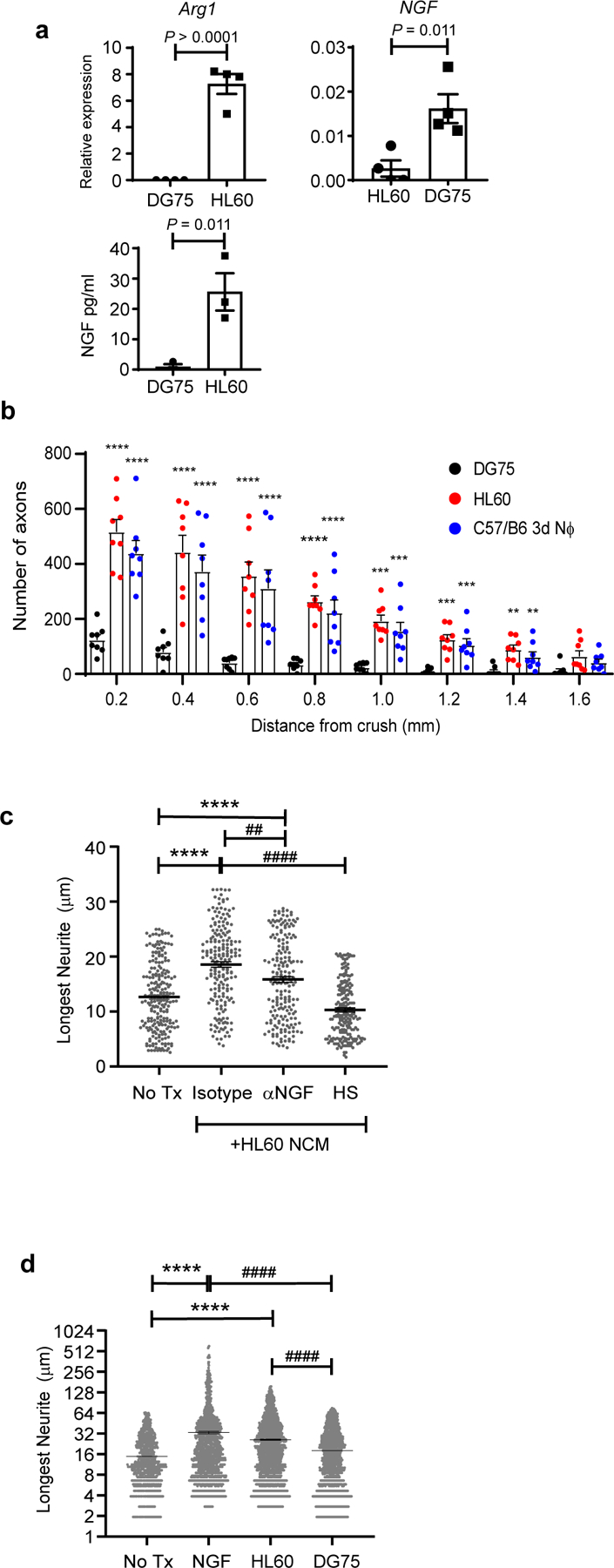

Human neutrophil-like cells are neuroregenerative.

We next investigated the capacity of human myeloid cells, with characteristics of an immature neutrophil, to initiate neurorepair. HL-60 is a human promyelocytic leukemia cell line that, following short term resting culture with DMSO, exhibits morphological, enzymatic, chemotactic properties, and a cell surface antigen profile, indicative of immature neutrophils (ie, promyelocytes and blasts)20,21. At that point, they are deficient in secondary granules, suggestive of an early developmental stage in the granulocyte lineage22. Similar to zymosan-modulated Ly6Glow murine neutrophils, HL-60 cells expressed Arg1 and NGFB (Fig. 7a). Furthermore, they stimulated the regrowth of severed RGC axons upon adoptive transfer into the eyes of RAG1-deficient mice with ONC injury (Fig. 7b). In contrast, adoptive transfer of DG75 cells, a human B cell lymphoma line, had no measurable effect. Conditioned media of HL-60, but not DG75, cells induced neurite outgrowth by explanted RGC and DRG neurons (Fig. 7c and data not shown). Similar to 3d Nϕ NCM, the axonogenic effect of HL-60 conditioned media was heat sensitive and partially suppressed by neutralization of NGF (Fig. 7c). HL60, but not DG75, cells directly stimulated neurite outgrowth by human cortical neurons in co-cultures (Fig. 7d). These results illustrate the neuroprotective and reparative potential of immature human granulocytes, mediated in part by a growth factor dependent mechanism.

Fig. 7 |. Human cell line derived immature neutrophils are neuroregenerative.

a, NGF protein levels were measured in conditioned media (CM) of HL60 and DG75 cells by ELISA (lower panel); Arg1 and NGF mRNA levels measured in HL60 and DG75 cells by qPCR, and normalized to Actβ (middle and right panels), n=4 independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined by two tailed unpaired Student’s t-test, b, Human HL60 or DG75 cells, or murine 3d NΦ, were adoptively transferred into the vitreous of C57BL/6 RAG1−/− mice on days 0 and 3 post ONC injury. Optic nerves were harvested 14 days later. Density of regenerating axons in optic nerve sections, at serial distances from the crush site (n= 8 nerves per group). One experiment representative of 2 is shown. Statistical significance determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test (**P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001, compared with DG75). c, Primary RGC were cultured with unconditioned media (No tx), HL60 CM in presence of either isotype control or anti-NGF antibodies, or heat shocked (HS) HL60 CM. Neurite length was measured 24 hours later (n= 200 RGCs per condition). One of 2 independent experiments is shown. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test (****P < 0.0001, compared with unconditioned media; ##P < 0.01, ####P < 0.0001, compared with HL60 CM + isotype antibodies). d, Primary human cortical neurons were cultured with unconditioned media alone (No Tx), NGF (positive control), HL60 cells, or DG75 cells. Neurite length was measured 24 hours later (n= 1000 neurons per condition). One of two experiments shown. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test (****P < 0.0001, ** P<0.01, compared to No Tx, ####P < 0.0001, compared with DG75 cells). a-d, Data shown as mean +/− sem.

Discussion

In this study, we identify a novel myeloid cell phenotype with neuroprotective and axogenic properties that arises in the setting of optic nerve and spinal cord injury. In contrast to the widely held notion that myeloid cells which promote tissue repair are generally of the monocyte/ macrophage lineage23–26, the reparative cell that we characterize here is a CD14+Ly6Glow granulocyte with features of an immature neutrophil. This finding is particularly surprising since numerous studies have highlighted the destructive impact of neutrophils infiltrating the CNS27–30. However, as opposed to pro-regenerative CD14+Ly6Glow cells, the neutrophils that mediate CNS damage in these experimental systems are mature hypersegmented neutrophils, that access the CNS in a CXCR2 dependent manner. Although a few published studies have suggested that neutrophils may play a beneficial role in the context of CNS trauma31,32, we are the first to characterize this singular CD14+Ly6Glow subset and its biological functions. The neuroprotective and axonogenic properties of the CD14+Ly6Glow cells are, in part, secondary to secretion of the growth factors NGF and IGF-1. Although highly effective, treatment with a combination of antibodies against NGF and IGF-1 did not completely abrogate CD14+Ly6Glow neutrophil-mediated axonal regeneration in vivo, implicating the presence of additional growth promoting factors. Proteomics analyses have revealed numerous growth factors, besides NGF and IGF-1, in vitreous fluid isolated from i.o. zymosan injected mice, as well as supernatants of pro-regenerative 3d NΦ, that could collectively contribute to RGC rescue and axon regrowth (unpublished data). Interestingly, we have found that adoptively transferred 3d NΦ spatially align against the inner retina the role of cell-to-cell interactions in the RGC regenerative process is a subject of ongoing investigation. We have considered the possibility that pro-regenerative neutrophils, and their products, modulate Muller glia and/ or retinal astrocytes, and that these glial cells, in turn, promote or amplify RGC survival and axon regrowth, possibly via production of NGF and IGF-1, or other factors such as Apolipoprotein E and CNTF33. GFAP expression is elevated in the retina of mice following i.o. injection of 3d NΦ, indicative of reactive astrogliosis. Future experiments with conditional knock-out or transgenic mice might help clarify the roles and mechanisms of action of different glial populations in the regenerative process.

Our findings add to a growing body of literature that attests to the heterogeneity and functional sub-specialization of circulating and tissue-infiltrating neutrophils. In particular, zymosan-elicited neuroregenerative neutrophils are reminiscent of recently described subpopulations of neutrophils that bear the signatures of an early developmental stage (based on cell surface phenotype and nuclear morphology) as well as alternative activation (based on expression of markers associated with M2-like macrophages), and play immunoregulatory and/ or reparative roles, in murine models of cancer, chronic infection, and myocardial ischemia13–15,17. Alternatively activated neutrophils have been detected in ischemic brain tissue in rodent models of stroke, and their frequency correlates with increased neuronal survival, reduced infarct size, and enhanced clinical recovery16,34. The extent to which the alternatively activated neutrophils characterized in these diverse models are biologically or developmentally related to one another, or share common mechanisms of action, remains to be determined. The existence of human neuroregenerative neutrophils is supported by our finding that HL-60 cells, widely used as a surrogate for immature human neutrophils, have axonogenic properties comparable to zymosan-elicited CD14+Ly6Glow murine neutrophils. HL-60-mediated neurite outgrowth is also partially dependent on NGF but not IGF-1 (data not shown). However, HL-60 is a transformed myeloid leukemic cell line, as opposed to a subset of naturally occurring, primary neutrophils. An atypical subpopulation of Arg1+ primary human neutrophils, isolated in the low density mononuclear layer of Ficoll gradients, has been described in the setting of advanced stage cancer, HIV infection, pregnancy, and systemic lupus erythematosus35–40. Although heterogeneous, the majority of these low density neutrophils are immature based on nuclear morphology (banded) and cell surface phenotype (CD33+CD10−CD16low). In a number of studies, low density human neutrophils were shown to possess immunosuppressive properties35–37. It is unknown whether they also possess reparative properties, and/ or whether they mobilize to sites of CNS injury.

ONC injury, in and of itself, induces the upregulation of dectin-1 on retinal microglia and dendritic cells12. We hypothesize that engagement of dectin-1 on resident myeloid cells triggers the generation of a local inflammatory milieu conducive to the recruitment and polarization of neuroregenerative Ly6Glow neutrophils. G-CSF levels rise in the vitreous fluid and the serum following i.o. zymosan injection, in conjunction with the mobilization of CD101−CD14+Ly6Glow neutrophils, that bear ring shaped nuclei, into the bloodstream (unpublished data). These circulating Ly6Glow cells do not express Arg1 or other markers of alternative activation, suggesting that they have not acquired neuroprotective or growth promoting properties in the periphery (data not shown). Hence, it is likely that Ly6Glow neutrophils are polarized towards a neuroregenerative phenotype only after they cross the blood-eye barrier. Zymosan-elicited Ly6Glow neutrophils express low levels of CXCR2 and infiltrate the vitreous by a CXCR2 independent pathway. We are currently interrogating candidate chemoattractants, other than ELR+ CXC chemokines, that might orchestrate their migration to the posterior chamber of the eye, as well as candidate polarizing factors that might drive their differentiation locally. We are hopeful that this research will inform the development of protocols for the generation of neuroregenerative neutrophils from bone marrow precursors ex vivo, with the ultimate goal of reinfusing the polarized neutrophils into individuals with axonal injury, as an autologous cellular therapy. Alternatively, selected mobilizing and polarizing factors could be administered systemically, or at sites of CNS injury, to expand endogenous populations of alternatively activated neutrophils. Finally, identification of CD14+Ly6Glow neutrophil chemoattractants may lead to the development of strategies that promote the migration of endogenous, as well as adoptively transfered, reparative neutrophils to sites of CNS injury, while blocking the migration of potentially toxic mature neutrophils or other pathogenic leukocytes. In previous studies of the ONC crush model, multimodal therapeutic approaches were more effective than single agents, in some cases achieving RGC axon regeneration across the optic chiasm (such as i.o. zymosan injection combined with a CAMP analog and pten deletion)41. The distinctive mechanism of action of the Ly6Glow neuroregenerative neutrophil subset makes it an attractive candidate for multimodal therapy, in synergy with agents that block cell-intrinsic or extrinsic suppressors of axon growth, to rescue dying neurons and enhance axonal regeneration after CNS injury.

Methods

Mice.

C57BL/6 WT, Ccr2−/− (B6.129S4-Ccr2tm1Ifc/J), Clec7a−/− (B6.129S6-Clec7atm1Gdb/J),Tlr2−/− (B6.129-Tlr2tm1Kir/J), and Rag1−/− (B6.129S7-Rag1tm1Mom/J) mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory. Dectin-1–TLR2 double-deficient (Clec7a−/− Tlr2−/− ) mice were bred and maintained in house. Mice were group-housed with a 12-h light/dark cycle and ad libitum access to food and water. All animal handling and surgical procedures were performed in compliance with national guidelines and approved by the University of Michigan and the Ohio State University Committees on Use and Care of Animals.

Optic nerve crush (ONC) surgery and i.o. zymosan injection.

Adult male or female mice (age 8–10 wk) were anesthetized with 100 mg/kg ketamine and 10 mg/kg xylazine i.p. The optic nerve was exposed through an incision in the conjunctiva while being visualized under a Nikon microscope. The nerve was then compressed, ∼1–2 mm behind the eye, for 5 sec using a curved forceps (Dumont #5; Roboz). Immediately after ONC, the posterior chamber of the eye was injected with 3 μL of zymosan (12.5 μg/μL in PBS) or PBS alone, using a Hamilton syringe with a 30 G removable needle. The eyes were then rinsed with a few drops of sterile PBS. Ophthalmic ointment (Puralube; Fera Pharmaceuticals) was applied on the operated eye. For all surgical procedures, buprenorphine (0.1 mg/kg, subcutaneous) was given pre- and post-operatively (12, 24, 36, 48, and 60 h) . All operated mice were closely monitored until the end point. At 2 weeks after surgery, mice were given a lethal dose of ketamine/xylazine i.p. and then perfused transcardially with PBS for 5 min. Mice were inspected for lens injury after each i.o. injection. Those with cataracts were eliminated.

Administration of antisera.

Mice were injected, i.p., every 2 days with 500 μl of rabbit polyclonal αCXCR2 neutralizing sera (Cocalico) or normal rabbit sera control (NRS, Sigma), as previously described42.

Intraperitoneal (i.p.) lavage and neutrophil isolation.

Mice were injected i.p. with 500 μl of zymosan (2 μg/μL in PBS) and euthanized either 4 h or 3 d later via CO2 fixation. 10 ml of sterile ice-cold PBS was injected into the peritoneal cavity, and aspirated after 5 min. Neutrophils were isolated from lavaged cells with MACS Ly6G magnetic beads (Miltenyi Biotec) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Purity (95–99%) was confirmed using flow cytometry.

Intro-ocular (i.o.) adoptive transfer.

Purified Ly6G+ cells were resuspended in sterile PBS at a concentration of 1 × 105 cells/μl and loaded into a Hamilton syringe with a 30 G needle. In some cases, anti-NGF (Alomone) and/ or anti-IGF1 (Abcam) polyclonal antibodies, or polyclonal control antibodies (Sigma), were included in the cell suspension, at a final concentration of 1 μg/μl. 3 μl of cell suspension was injected into the posterior chamber of each eye of anesthesized mice on days 0 and 3 post ONC injury.

Intraocular administration of growth factors.

Recombinant mouse NGF (R&D) and/ or IGF-1 (Peprotech) were reconstituted in sterile PBS at a concentration of 1 μg/μl. Recombinant growth factors or PBS alone were injected into the posterior chamber of the eye (1–2 μl/ eye) of anesthesized mice immediately following ONC and on post op day 3.

Dorsal spinal cord injury (SCI).

Male mice were anesthetized with 100 mg/kg ketamine and 10 mg/kg xylazine i.p. The T8 lamina were removed under a stereomicroscope using micro-rongeurs. The spinal column was exposed, and Roboz McPherson-Vannas Micro Dissecting Spring scissors were inserted 1mm deep. A hemisection of the dorsal spinal cord was performed to transect axons in the dorsal columns. Muscle layers were closed with Perma-Hand Black sutures (5–0, Ethicon) and skin incisions were closed with coated Vycryl sutures (5–0, Ethicon). 6 weeks after SCI, rhodamine-conjugated dextran MW 3,000 (Microruby, Life Technology, 1.5 μl of 10% solution) was injected into the sciatic nerve using a Nanofil 10 μL syringe with a 36 G beveled needle (World Precision Instrument). 10 days after tracer injection, mice were perfused and spinal cords were harvested for immunohistochemical analysis.

Sciatic nerve crush.

Five days prior to SCI, some mice received a conditioning injury to the sciatic nerve. Mice were anesthetized as described above and the sciatic nerves on both sides were exposed and compressed at mid-thigh level for 10 s using fine forceps (Dumont #5). The surgical wound was closed by clipping the overlying skin.

Intraneural adoptive transfer.

Purified Ly6G+ cells were resuspended in sterile PBS at a concentration of 1 × 105 cells/μl and loaded into a Nanofil syringe with a 33 G needle (World Precision Instrument). Each sciatic nerve was injected with 1.5 μl of cell suspension.

Primary mouse RGC cultures.

6–7 day old mouse pups were euthanized. Their eyes were dissected and placed in ice cold PBS. Under a Nikon dissection stereoscope, retinas were exposed; the neural layer was dissected and placed into 1ml of ice-cold PBS. Retinas were transferred to a 15 ml conical tube with 1 ml of 0.05% trypsin (Gibco). Retinas were triturated 20x with a fire polished glass pipette, incubated in a water bath at 37°C for 5 min, after which trituration was repeated. Trypsin was quenched by adding 10 ml of 10% FBS in PBS. Tubes were centrifuged at 1500 RPM for 5 min. Supernatant was removed. Cells were suspended in MACS buffer (2% BSA, 0.004% EDTA in PBS). RGCs were isolated withMACS Thy1.2 magnetic beads (Miltenyi Biotec). Purified RGCs were suspended in Neurobasal media (Gibco) supplemented with B27 s (Gibco), glutamine (2 mM, Gibco), and Penicillin/Streptomycin (100 units/ml, Gibco), andplated at 1 × 104cells/well in a 96-well plate that had been precoated with poly-L-lysine (Sigma) and laminin (Millipore). RGCs were co-cultured with MACS purified Ly6G+ neutrophils (1 × 104cells/well), neutrophil conditioned media, zymosan (1 μg/ml), or recombinant CNTF (100 ng/ml) for 20 h at 37°C and 5% CO2, after which they were fixed with ice cold 4% PFA in PBS for 30 min, before immunohistochemical staining and imaging.

Primary mouse DRG cultures.

Lumbar (L4–5) DRG,collected from 8–10-week-old mice, were digested with collagenase type 2 (4 mg/ml, Worthington Biochemical) and dispase (1 mg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich) for 45 min at 37°C and 5% CO2. DRGs were counted, resuspended in DMEM/F12 (Gibco) with FBS (10%, Atlanta Biologicals), Glutamine (2 mM, Gibco), and Penicillin/Streptomycin (100 units/ ml; Gibco), and plated at a concentration of 5 × 103/well on laminin/polyL-lysine–coated 24-well plates. DRG were incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2, either alone or in the presence of Ly6G MACS bead purified neutrophils (1 × 104 cells/ well) or neutrophil conditioned media. After 20 h, cultures were fixed with ice cold 4% PFA in PBS for 30 min before immunohistochemical staining and analysis.

Primary human cortical neuron in vitro culture.

Primary human cortical neurons (ScienCell) were thawed, counted, diluted in neuronal media with Neuronal growth supplement (ScienCell), and plated at 1.2 × 104cells/well in a 96-well plate precoated with poly-L-lysine (Sigma) and laminin (Millipore). Neurons were either cultured alone, or in the presence of HL60 cells, DG75 cells (1.2 × 104cells/well) or recombinant human NGF (10 μg/ml), at 37°C and 5% CO2. After 20 h neurons were fixed with ice cold 4% PFA in PBS for 30 min, prior to immunohistochemical staining and imaging.

Immunohistochemistry and quantification of regenerating axons, viable RGC, and neurite length.

Optic nerves.

Mice were perfused, optic nerves and eyes were dissected and post fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4°C. Nerves were transferred to a 30% sucrose/PBS solution and maintained at 4°C for at least 2 h and up to 2 wk. Optic nerves were imbedded in Tissue-Tek OCT Compound (Sakura Fintek USA, Inc.) and stored at −80 °C. Longitudinal sections (10 μm thick) were cut with a cryostat, mounted on Superfrost Plus microscope slides (Fisher Scientific), and stained with polyclonal rabbit anti-GAP43 antibodies (Abcam). Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Invitrogen) was used for fluorescent labeling. Images were acquired using an Olympus IX71 inverted microscope with Olympus Cellsens Dimension 2.0 software, attached to an Olympus DP72 digital camera. Regenerating GAP43+ axons were counted at each 0.2-mm interval past the injury site, up to 1.6 mm, using a superimposed grid (3–5 sections/ nerve). The number of labeled axons per section was normalized to the width of the section and converted to the total number of regenerating axons per optic nerve, as described previously43.

Retinas.

For cross-sectional images, eyes were dissected, post fixed as described above, and cryoprotected. 25 μm sections were cut with a cryostat. Sections were mounted on Superfrost Plus microscope slides, rinsed with PBS, blocked with 5% normal goat serum in PBS with 0.25% Triton X-100 [PBS-T]) at 25°C, and incubated with primary antibodies (anti-GFAP, Sigma, 1:500; anti-Iba1 Invitrogen 1:300) diluted in blocking solution (PBST+ 5% goat serum) overnight at 4°C. The next day, sections were washed with PBS-T and incubated with secondary antibodies (Goat anti-mouse Alexa 488 or Goat anti-rabbit Alexa 594) in blocking solution (PBS+ 5% goat serum) for 2 h at 25°C. DAPI (300 nM) was used to counterstain sections.

For whole retinal whole mount, PFA-fixed retinas were placed in a 35 mm dish (Corning) with sterile PBS. The retinal neural layer was dissected out of the globe under a dissecting microscope. Retinas were incubated with goat anti-mouse Brn3a (Santa Cruz) for 3 days, followed by Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated donkey anti-goat secondary antibody (invitrogen). Retinas were washed, placed on Superfrost Plus microscope slides and imaged. Images were acquired using an Olympus IX71 inverted microscope attached to an Olympus DP72 digital camera. Brn3a+ RGCs were counted over 8 fields distributed between 4 quadrants per retina at pre-specified distances from the optic disc using Image J software32.

Spinal Cords.

Dissected spinal cords were post-fixed overnight and transferred to 30% sucrose in solution for cryoprotection. Spinal cords were cut into 25 μm thick sagittal sections using a cryostat and processed for immunostaining44. Briefly, spinal cord tissue sections were rinsed with PBS, blocked with 5% normal donkey serum in PBS with 0.25% Triton X-100 [PBS-T]) at 25°C, and incubated with primary antibodies (anti-GFAP, Sigma, 1:500; anti-laminin, Sigma, 1:500) diluted in blocking solution (PBST+ 3% donkey serum) overnight at 4°C. The next day, sections were washed with PBS-T and incubated with secondary antibodies (Donkey anti-mouse Alexa 488 and donkey anti-rabbit Alexa 647) in blocking solution (PBS+ 3% donkey serum) for 2 h at 25°C. After washing with PBS and mounting (ProLong anti-fade mounting medium, Life Technologies), sections were imaged using a Zeiss Axiovert Zoom fluorescent microscope or Olympus IX71. Regeneration of dorsal column axons was quantified in all sections containing Microruby labeled axons (4–6 sections per animal), as previously described45. The lesion center was localized using characteristic GFAP and laminin staining patterns. The average distance from the epicenter to the most rostral, Microruby-positive axon tips was measured using Image J. The average value from all tracer containing sections was taken as one data point.

Primary murine DRG, murine RGC, and human cortical neurons.

Plates were washed in PBS+0.1% Triton-X (PBST), then blocked with 10% goat sera in PBST, for 1 h, at 25°C. After washing twice in PBST, samples were incubated with anti-βIII-tubulin antibodies (TUJ1, Promega), in 3% BSA in PBST, overnight at 4 °C. Following two PBST washes, the samples were incubated with an Alexa Fluor488-conjugated secondary antibody (invitrogen), for 1–2 h at 25°C. Samples were washed twice with PBS and left in a solution of PBS and DAPI stain (NucBlue Fixed Cell ReadyProbes Reagent (ThermoFisher Scientific), 2 drops per ml PBS). RGCs and human cortical neurons were imaged at 20×, and DRG at 10×, using an Olympus IX71 inverted microscope attached to an Olympus DP72 digital camera. Images were analyzed with Neuromath (Weizmann Institute of Science). The longest neurite of each neuron was measured in graphpad (Prism).

Neutrophil conditioned media.

MACS-purified neutrophils were placed into the RGC base media (neurobasal media with B27, Pen/strep and 2 mM L-glutamine) at a concentration of 5 × 106 cell/ml and incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 24 h. Supernatant was collected and spun at 1800 RPM.

Cell morphology.

Purified neutrophils were subjected to cytospin for five minutes at 5.5 × 103 RPM. Slides were air dried, stained with Wright-Giemsa solution (thermo-scientific), and imaged under an Olympus IX71 inverted microscope.

Flow Cytometry.

Flow cytometric analysis was performed as previously described46,47. Mice were euthanized by isofluorane overdose. Blood was collected from the left ventricle in an EDTA tube. PBMCs were isolated over a lympholyte gradient (Cedarlane labs), and incidental red blood cells were lysed using an Ammonium-Chloride-Potassium (ACK) Lysing Buffer (Quality Biological). Eyes were dissected, rinsed in PBS, and placed in a 35-mm dish (Corning). Each eye was opened, vitreous fluid was collected; retinas were rinsed with 200 μl of PBS. Cells in the vitreal fluid and retinal rinse were combined.

Cells were labeled with fixable viability dye (eFluor506 or eFluor780; eBioscience), blocked with anti-CD16/32 (clone 2.4G2), and stained with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies specific for CD11b (clone M1/70), CD45 (30-F11), CD11c (N418), CD3 (145–2C11), CD4 (GK1.5), CD8 (53–6.7), CD19 (1D3), CD14 (61D3), Ly6B (7/4), CD101 (polyclonal), and F4/80 (BM8), all purchased from eBiosciences; and Ly6C (AL-21) and Ly6G (1A8), purchased from Pharmingen. For intracellular staining, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.5% saponin and stained with fluorescent antibodies specific for arginase-1 (polyclonal; eBiosciences), neutrophil elastase (polyclonal, Bioss) or myeloperoxidase (polyclonal, Abcam). Flow cytometry was performed with a FACS Canto II cell analyzer (BD Biosciences). Cells were gated on forward and side scatter after doublet exclusion and analyzed on FlowJo v10 software.

Human hematopoietic cell lines.

HL-60 and DG-75 cell lines were obtained from ATCC. Cells were cultured in RPMI Media with 10% FBS + 2mM L-glutamine + Pen/Strep. 24 h prior to co-culture with RGCs, cells were transferred to Neurobasal with B27 supplementation, L-glutamine and Pen/strep.

Protein analysis.

A panel of growth factors were measured in NCM using a growth factor antibody array (Raybiotech). ELISA was used to measure murine NGF (Millipore) and IGF-1 (Thermo-Scientific), and human NGF and IGF-1 (both Abcam), protein levels. Total protein was determined via a Bradford assay (Thermo Scientific) and used to normalize analyte concentrations.

Quantitative PCR.

Cells were resuspended in 300 ml of RLT buffer prior to Qiagen RNeasy RNA purification. Purified RNA was converted into cDNA using a high-capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Life Technologies). Transcripts were quantified via SYBR Green qPCR performed an iQ Thermocycler (Bio-Rad) or ABI using Quant Studio Design v1.3. Primer sequences shown in chart below.

Mouse:

Actb: FP: 5′-GGTCCACACCCGCCACCAG-3′ RP: 5′-CACATGCCGGAGCCGGAGCCGTTGTC-3′

Arg1: FP: 5′-CTCCAAGCCAAAGTCCTTAGAG-3′ RP: 5′-AGGAGCTGTCATTAGGGACATC-3′

Il4ra: FP: 5′-ACACTACAGGCTGATGTTCTTCG-3′ RP: 5′-TGGACCGGCCTATTCATTTCC-3′

Mrc1: FP: 5′-AAGGCTATCCTGGTGGAAGAA-3′ RP: 5′-AGGGAAGGGTCAGTCTGTGTT-3′

Ngfb: FP: 5′-CCCGAATCCTGTAGAGAGTGG-3′ RP: 5′-GAGTTCCAGTGTTTGGAGTCGAT-3′

Igf1: FP: 5′-AGACAGGCATTGTGGATGAG-3′ RP: 5′-TGAGTCTTGGGCATGTCAGT-3′

Human:

ACTB: FP: 5′-CATGTACGTTGCTATCCAFFC-3′ RP: 5′-CTCCTTAATGTCACGCACGAT-3′

ARG1: FP: 5′-GTGGAAACTTGCATGGACAAC-3′ RP: 5′-AATCCTGGCACATCGGGAATC-3′

NGFB: FP: 5′-TGTGGGTTGGGGATAAGACCA −3′ RP: 5′-GCTGTCAACGGGATTTTGGGT-3′

Single-cell RNA seq 10x genomics.

Eyes were dissected, and the vitreous fluid was collected, retinas were rinsed with 200 μl of PBS and cells collected from rinse. Neutrophils were purified by MACS Ly6G bead purification. Cell purity and viability was confirmed by flow cytometry. A single-cell suspension was submitted to University of Michigan Genomics Core for processing and analysis. The single-cell suspension was loaded onto a well on a 10x Chromium Single Cell instrument (10x Genomics). Barcoding and cDNA synthesis were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, the 10x™ GemCode™ Technology partitions thousands of cells into nanoliter-scale Gel Bead-In-EMulsions (GEMs), where all the cDNA generated from an individual cell share a common 10x Barcode. In order to identify the PCR duplicates, Unique Molecular Identifier (UMI) was also added. The GEMs were incubated with enzymes to produce full-length cDNA, which was then amplified by PCR to generate enough quantity for library construction. Qualitative analysis was performed using the Agilent Bioanalyzer High Sensitivity assay.

The cDNA libraries were constructed using the 10x ChromiumTM Single cell 3′ Library Kit according to the manufacturer’s original protocol. For post library construction QC, 1 μl of sample was diluted 1:10 and ran on the Agilent Bioanalyzer High Sensitivity chip for qualitative analysis. For quantification, Illumina Library Quantification Kit was used. Libraries were sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq or NextSeq 2×150 paired-end kits using the following read length: 26-bp Read1 for cell barcode and UMI, 8-bp I7 index for sample index and 98-bp Read2 for transcript. Cell Ranger 1.3 (http://10xgenomics.com) was used to process Chromium single cell 3′ RNA-seq output.48

Once the gene-cell data matrix was generated, poor quality cells were excluded, such as cells with less than 500 unique genes or more than 7,000 unique genes expressed. Only genes expressed in 3 or more cells were used for further analysis. Cells were also discarded if their mitochondrial gene percentages were over 20%. The data were natural log transformed and normalized for scaling the sequencing depth to a total of 1 × 104 molecules per cell, followed by regressing-out the number of UMI using Seurat package (version 2.3.3).

Seurat downstream analysis steps included SCTransform, dimensionality reduction [PCA (Principal component analysis], and UMAP (Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection), standard unsupervised clustering, and the discovery of differentially expressed cell type-specific markers. The SCTransform functionality embedded in Seurat R package include normalization and scaling of UMI, batch information and mitochondrial content. We included the batch information as a variable in the SCTransform to scale out the differences between the batches. For the unsupervised clustering, we chose as low resolution parameter (0.1). Differential gene expression analyses, to identify cell type-specific genes, were performed using the non-parametric Wilcoxon rank sum test. In order to compare the average gene expression of genes in the cell types identified in the two single-cell datasets, heat maps using Pearson’s correlation values were generated.

Statistical Analysis.

RGC frequency and axon density data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test using Graphpad 8.0 (Prism). The unpaired Student t test was used to analyze flow cytometry, ELISA, and qPCR data with only two groups, and one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test was used to analyze flow cytometry, ELISA, RGC cultures and qPCR data with more than two groups.

Extended Data

Extended Data Fig. 1. Zymosan-induced RGC axon regeneration is independent of mature T and B cells.

a, Gating scheme for analysis of intraocular infiltrates by flow cytometry. b, C57BL/6 WT or RAG1 deficient mice were injected i.o. with zymosan or PBS on the day of ONC injury. Optic nerves were harvested 14 days later. Longitudinal sections were stained with fluorochrome-conjugated anti-GAP-43 antibodies to enumerate the density of regenerating axons at serial distances from the crush site (n=6 nerves/ group). Data are shown as mean +/− sem. One of two independent experiments with similar results is shown. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test (P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, compared with the PBS →WT group). c, Optic nerves were harvested on day 28 following i.o. injection of either PBS or zymosan. Mice received i.p. injections of either αCXCR2 antisera or control sera every other day from the day of ONC onward. The density of GAP-43+ regenerating axons was measured in optic nerve longitudinal sections at serial distances from the crush site (n= 10 nerves per group). Data are shown as mean +/− sem; statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 compared with the i.o. PBS/ i.p. NRS group; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001, compared with the i.o. zymosan/ i.p. NRS group).

Extended Data Fig. 2. Immature neutrophils are mobilized into the circulation following treatment with i.o. zymosan and i.p. αCXCR2.

Mice received an i.o. injection of zymosan on day 0, and i.p. injections of NRS (blue) or αCXCR2 (red) on days 0 , 2 and 4, post ONC injury. Peripheral blood cells were obtained on day 5 and analyzed by flow cytometry. a, Cell surface expression of Ly6G, CD14 and CD101. Upper panels, representative histograms. Lower panels, geometric Mean Fluorescence Intensity on gated Ly6G+ cells and percentage of CD101+ neutrophils. Each symbol represents data from an individual mouse (n=3 mice/ group). Data are shown as mean +/− sem. One experiment representative of 3 with similar results is shown. Statistical significance was determined by two tailed unpaired Student’s t-test. b, Representative dot plots.

Extended Data Fig. 3. A population of alternatively activated, immature neutrophils is expanded in intraocular infiltrates following treatment with i.o. zymosan and i.p. αCXCR2.

Single-cell analysis using 10X Genomics of intraocular Ly6G+ cells from the NRS (left panels) or αCXCR2 (right panels) treatment groups, as in fig. 3. a, Violin plots showing the cells expressing Arg1, Mrc, Hexb, Sgrn and Fpr1 in clusters 1 and 3 of the NRS and αCXCR2 treatment groups. b, Featureplots showing cluster-specific expression of Mrc (CD206, alternative activation marker), CXCR2 and S100a8 (maturation markers).

Extended Data Fig. 4. Adoptively transferred CD14+Ly6Glow cells induce RGC axon regeneration independent of TLR2 and dectin-1 or CCR2 signaling.

a, Mice were subjected to ONC injury on day 0 and received i.o. injections of either PBS, 4h NΦ, or 3d NΦ, on days 0 and 3. Retina were harvested on day 14. The frequency of viable BRN3a+ RGC neurons in whole mounts, normalized to healthy retina (n=10 retina per group). One experiment representative of 2 is shown. Statistical significance determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. b, Peritoneal Ly6G+ cells were purified 3 days after i.p. zymosan injection (3d NΦ), and adoptively transferred into the eyes of naïve C57BL/6 WT or TLR2−/−dectin-1−/− double knock-out (dko) mice on days 0 and 3 post ONC injury. For negative controls, additional groups were injected i.o. with PBS. Optic nerves were harvested 14 days later and analyzed by GAP-43 immunohistochemistry. The figure shows the density of regenerating axons, at serial distances from the crush site (n= 8 nerves per group). One of 2 independent experiments is shown. Statistical significance determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 compared with PBS/WT; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 compared with PBS/dKO). c, GFAP (green) and IBA1 (red) IHC of retinal cross-sections obtained 7 or 14 days following ONC and i.o injection of either 3d NΦ or PBS. Representative images shown (n= 3 mice, 1 of 3 independent experiments, scale bar 80 μm). d, eGFP labeled 3d NΦ were injected i.o. on the day of ONC injury. Representative microscopic image of retinal cross-section prepared 3 days later (n=3 mice, 1 of 2 independent experiments scale bar 200 μm). e, Representative flow cytometric analysis of intraocular infiltrates harvested from WT or Ccr2−/− mice on day 3 post ONC injury and i.o. injection of 3d NΦ (n= 5 mice per group). f, 3d NΦ were adoptively transferred into the eyes of C57BL/6 WT or Ccr2−/− mice on days 0 and 3 post ONC injury. Axonal densities at serial distances from the crush site, on day 14 post ONC injury (n=6 nerves, 1 of 2 independent experiments is shown). Statistical significance determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, compared with PBS/WT; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 ####P < 0.0001, compared with PBS/ Ccr2−/−). a,b,f Data are shown as mean +/− sem.

Extended Data Fig. 5. Pro-regenerative neutrophils retain therapeutic efficacy when administered following CNS injury.

a, 3d NΦ were adoptively transferred into the eyes of mice on the day of ONC injury, or after a delay of 6, 12, or 24 hrs. NΦ adoptive transfer was repeated 3 days later. A control group was injected i.o. with PBS alone on days 0 and 3. Optic nerves were harvested on day 14 for quantification of axonal densities by GAP-43 IHC (n= 8 nerves per group). (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01 *** P<0.001 compared with PBS). b, 4h or 3d NΦ were added to primary RGC cultures 4hrs after RGC plating. In other wells, RGC were cultured in media alone (No Tx), or in the presence of recombinant CNTF, as negative and positive controls, respectively. Neurite outgrowth was measured 24 hours later (n=2000 RGCs per condition, one of two independent experiments shown). Statistical significance determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. c, 4h or 3d NΦ were added to primary DRG cultures 8hrs after DRG plating. In other wells, DRG were cultured in media alone (No Tx), or in the presence of recombinant NGF, for negative and positive controls, respectively. Neurite outgrowth was measured 24 hours later (n=300 DRGs per condition, one of two independent experiments shown). Statistical significance determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. a-c, Data shown as mean +/− sem.

Extended Data Fig. 6. NGF and IGF-1 drive RGC axon regeneration in a collaborative manner.

a, Quantification of a panel growth factors in unconditioned media (black bars) and NCM (gray bars) by multiplexed antibody array. b, Primary RGC were cultured in the absence or presence of recombinant mouse CNTF, IGF-1, NGF, or a combination of IGF-1 and NGF. Neurite length was measured 24 hours later. Each symbol represents the mean of 200 RGCs in one independent experiment (n=6 independent experiments shown). Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test (**P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 compared with No Tx; #P < 0.05 compared with NGF; ++P < 0.01, compared with IGF-1). c, Recombinant IGF-1 (blue bars), NGF (green), a combination of NGF and IGF1 (white), or PBS alone (black) was injected into the vitreous on days 0 and 3 post ONC injury. Optic nerves were harvested 14 days later. Density of regenerating axons in optic nerve sections, at serial distances from the crush site (n= 8 nerves per group). One experiment representative of 2 with similar results is shown. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 compared with PBS; #P < 0.05 compared with NGF; +P < 0.05, ++P < 0.01, compared with IGF-1). b,c, Data shown as mean +/− sem.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank S. Atkins for technical support. Financial support for this research was provided by the National Eye Institute (NEI), National Institutes of Health (R01EY029159 and R01EY028350, to B.M.S. and R.J.G., and K08NS101054 to A.R.S.), the Wings of Life Foundation (C.Y.), and the Dr. Miriam and Sheldon G. Adelson Research Foundation (R.J.G.). B.M.S. holds the Stanley D. and Joan H. Ross Chair in Neuromodulation at the Ohio State University.

Footnotes

Competing Interests statement

The authors have no competing interests.

Data Availability

Single cell RNA seq data are available in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (www.ncbi.nlm.hih.gov/geo) with accession no, GSE144637. Other data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on request.

References

- 1.Lucas T et al. Differential roles of macrophages in diverse phases of skin repair. J Immunol 184, 3964–3977, doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903356 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tourki B & Halade G Leukocyte diversity in resolving and nonresolving mechanisms of cardiac remodeling. FASEB J 31, 4226–4239, doi: 10.1096/fj.201700109R (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chinetti-Gbaguidi G, Colin S & Staels B Macrophage subsets in atherosclerosis. Nat Rev Cardiol 12, 10–17, doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2014.173 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Segal BM CNS chemokines, cytokines, and dendritic cells in autoimmune demyelination. J Neurol Sci 228, 210–214, doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2004.10.014 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Akiyama H et al. Inflammation and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiology of aging 21, 383–421, doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(00)00124-x (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shi K et al. Global brain inflammation in stroke. Lancet Neurol 18, 1058–1066, doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(19)30078-X (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miron VE et al. M2 microglia and macrophages drive oligodendrocyte differentiation during CNS remyelination. Nat Neurosci 16, 1211–1218, doi: 10.1038/nn.3469 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giles DA et al. Myeloid cell plasticity in the evolution of central nervous system autoimmunity. Ann Neurol 83, 131–141, doi: 10.1002/ana.25128 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bollaerts I, Van Houcke J, Andries L, De Groef L & Moons L Neuroinflammation as Fuel for Axonal Regeneration in the Injured Vertebrate Central Nervous System. Mediators of inflammation 2017, 9478542, doi: 10.1155/2017/9478542 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jassam YN, Izzy S, Whalen M, McGavern DB & El Khoury J Neuroimmunology of Traumatic Brain Injury: Time for a Paradigm Shift. Neuron 95, 1246–1265, doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.07.010 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yin Y et al. Macrophage-derived factors stimulate optic nerve regeneration. J Neurosci 23, 2284–2293 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baldwin KT, Carbajal KS, Segal BM & Giger RJ Neuroinflammation triggered by beta-glucan/dectin-1 signaling enables CNS axon regeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112, 2581–2586, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1423221112 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fridlender ZG et al. Polarization of tumor-associated neutrophil phenotype by TGF-beta: “N1” versus “N2” TAN. Cancer cell 16, 183–194, doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.06.017 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen F et al. Neutrophils prime a long-lived effector macrophage phenotype that mediates accelerated helminth expulsion. Nat Immunol 15, 938–946, doi: 10.1038/ni.2984 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsuda Y et al. Three different neutrophil subsets exhibited in mice with different susceptibilities to infection by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Immunity 21, 215–226, doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.07.006 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cuartero MI et al. N2 Neutrophils, Novel Players in Brain Inflammation After Stroke Modulation by the PPAR gamma Agonist Rosiglitazone. Stroke 44, 3498–3508, doi: 10.1161/Strokeaha.113.002470 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Horckmans M et al. Neutrophils orchestrate post-myocardial infarction healing by polarizing macrophages towards a reparative phenotype. Eur Heart J 38, 187–197, doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw002 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang W et al. Neutrophils promote the development of reparative macrophages mediated by ROS to orchestrate liver repair. Nat Commun 10, 1076, doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09046-8 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Neumann S & Woolf CJ Regeneration of dorsal column fibers into and beyond the lesion site following adult spinal cord injury. Neuron 23, 83–91 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Newburger PE, Chovaniec ME, Greenberger JS & Cohen HJ Functional changes in human leukemic cell line HL-60. A model for myeloid differentiation. J Cell Biol 82, 315–322, doi: 10.1083/jcb.82.2.315 (1979). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boss MA, Delia D, Robinson JB & Greaves MF Differentiation-linked expression of cell surface markers on HL-60 leukemic cells. Blood 56, 910–916 (1980). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Olsson I & Olofsson T Induction of differentiation in a human promyelocytic leukemic cell line (HL-60). Production of granule proteins. Exp Cell Res 131, 225–230, doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(81)90422-5 (1981). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ma SF et al. Adoptive transfer of M2 macrophages promotes locomotor recovery in adult rats after spinal cord injury. Brain Behav Immun 45, 157–170, doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2014.11.007 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wynn TA & Vannella KM Macrophages in Tissue Repair, Regeneration, and Fibrosis. Immunity 44, 450–462, doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.02.015 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schwartz M “Tissue-repairing” blood-derived macrophages are essential for healing of the injured spinal cord: from skin-activated macrophages to infiltrating blood-derived cells? Brain Behav Immun 24, 1054–1057, doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2010.01.010 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gliem M, Schwaninger M & Jander S Protective features of peripheral monocytes/macrophages in stroke. Biochimica et biophysica acta 1862, 329–338, doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2015.11.004 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.von Leden RE, Parker KN, Bates AA, Noble-Haeusslein LJ & Donovan MH The emerging role of neutrophils as modifiers of recovery after traumatic injury to the developing brain. Exp Neurol 317, 144–154, doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2019.03.004 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Semple BD, Bye N, Ziebell JM & Morganti-Kossmann MC Deficiency of the chemokine receptor CXCR2 attenuates neutrophil infiltration and cortical damage following closed head injury. Neurobiol Dis 40, 394–403, doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2010.06.015 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Herz J et al. Role of Neutrophils in Exacerbation of Brain Injury After Focal Cerebral Ischemia in Hyperlipidemic Mice. Stroke 46, 2916–2925, doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.010620 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brennan FH et al. Complement receptor C3aR1 controls neutrophil mobilization following spinal cord injury through physiological antagonism of CXCR2. JCI insight 4, doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.98254 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roth TL et al. Transcranial amelioration of inflammation and cell death after brain injury. Nature 505, 223–228, doi: 10.1038/nature12808 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kurimoto T et al. Neutrophils express oncomodulin and promote optic nerve regeneration. J Neurosci 33, 14816–14824, doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5511-12.2013 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lorber B, Berry M, Douglas MR, Nakazawa T & Logan A Activated retinal glia promote neurite outgrowth of retinal ganglion cells via apolipoprotein E. J Neurosci Res 87, 2645–2652, doi: 10.1002/jnr.22095 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hou Y et al. N2 neutrophils may participate in spontaneous recovery after transient cerebral ischemia by inhibiting ischemic neuron injury in rats. Int Immunopharmacol 77, 105970, doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2019.105970 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sagiv JY et al. Phenotypic diversity and plasticity in circulating neutrophil subpopulations in cancer. Cell Rep 10, 562–573, doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.12.039 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu CY et al. Population alterations of L-arginase- and inducible nitric oxide synthase-expressed CD11b+/CD14(−)/CD15+/CD33+ myeloid-derived suppressor cells and CD8+ T lymphocytes in patients with advanced-stage non-small cell lung cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 136, 35–45, doi: 10.1007/s00432-009-0634-0 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rodriguez PC et al. Arginase I-producing myeloid-derived suppressor cells in renal cell carcinoma are a subpopulation of activated granulocytes. Cancer research 69, 1553–1560, doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1921 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cloke T, Munder M, Taylor G, Muller I & Kropf P Characterization of a novel population of low-density granulocytes associated with disease severity in HIV-1 infection. PLoS One 7, e48939, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048939 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ssemaganda A et al. Characterization of neutrophil subsets in healthy human pregnancies. PLoS One 9, e85696, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085696 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mistry P et al. Transcriptomic, epigenetic, and functional analyses implicate neutrophil diversity in the pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 116, 25222–25228, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1908576116 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Benowitz LI, He Z & Goldberg JL Reaching the brain: Advances in optic nerve regeneration. Exp Neurol 287, 365–373, doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2015.12.015 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References