Highlights

-

•

Common Bile Duct is extremely rare site for primary Neuroendocrine tumors.

-

•

WHO classification categorized neuroendocrine neoplasms of digestive tract into three subtypes: well differentiated neuroendocrine tumor, poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma and mixed adenoneuroendocrine carcinoma.

-

•

The etiology of developing NET in the bile duct tissues is unknown but it is related to chronic inflammation with subsequent metaplasia.

-

•

Surgical resection is the mainstay of the treatment.

-

•

Postoperative chemotherapy using cisplatin and etoposide showed promising results.

Keywords: Neuroendocrine tumors, Common bile duct, Case report

Abstract

Introduction

Neuroendocrine tumors (NET) of common bile duct are rare. There have been less than 100 cases reported worldwide.

Presentation of case

A 37-year-old female patient was referred to our center after six months of abdominal pain with no definite diagnosis. At initial presentation, she complained of increased abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, oral intolerance to food and icteric sclera. Physical examination and laboratory tests were indicative of pancreatitis. At day four, she took retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) and a mid CBD stenosis or impacted stone was found. In order to locally investigate the lesion, Endoscopic Ultrasound (EUS) examination was performed which reported 16 × 12 mm isoechoic tumoral lesion at the middle of the CBD. In this regard we decided to perform ERCP-guided brushing biopsy of the lesion. The pathology report was highly suggestive for malignancy. She underwent resection of the mid portion of the CBD with Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy, cholecystectomy and portahepatis lymph node dissection. The pathology report indicated that the CBD lesion was well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumor grade II.

Discussion

The exact etiology of developing NET in the bile duct tissues is not clear however cholelithiasis and congenital malformation of the biliary tract has been proposed to cause chronic inflammation with subsequent metaplasia which ultimately transforms into NET.

Conclusion

As there are very few cases of NETs of the CBD, no definite surgical or medical treatment is proposed. Currently, combination of radical surgical resection and lymph node dissection followed by chemotherapy is the treatment of choice.

1. Introduction

Neuroendocrine tumors (NET) are rare originating from chromaffin cells and Kulchitsky cells both of which originate from the endoderm [1]. Most cases of NETs occur in gastrointestinal tract and pancreatic tissue, however, lung, thymus, and uterus are other sites of primary lesions. Common Bile Duct (CBD) is extremely rare site for primary NETs because even though chromaffin cells consist high proportion of the small intestine cells, they are rarely found within the biliary ducts [2]. Most cases introduced in the literature are presented with painless jaundice with or without pruritus however pain or discomfort in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen and weight loss may initiate patient’s symptoms [3]. Given the paucity of data on the incidence of NET, gender dominancy and age at presentation is not clear, but most cases are female patients ranged 37–67 years old [4]. Here we report the first national case of NET found in the middle of the CBD presenting with long standing dull abdominal pain.

2. Case presentation

A 37-year-old female patient was referred to Cancer Institute, Imam Khomeini Hospital Complex, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran after six months of abdominal pain with no definite diagnosis rather than a 2 × 3 cm mass lesion in the CBD reported in an abdominal ultrasonography which was performed in private clinic outside of our center. At initial presentation, she complained of increased abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, oral intolerance to food and icteric sclera. Laboratory tests were indicative of serum total bilirubin level of 10.1 mg/dL with 7.5 mg/dL being direct bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase level of 944 IU/L, aspartate aminotransferase of 44 IU/L and alanine aminotransferase of 44 IU/L, amylase level of 2310 IU/L and lipase level of 1190 IU/L, there was no leukocytosis or anemia found. The initial impression was pancreatitis and she became hydrated until appropriate diuresis established. As the hemodynamic variables were stable, she was candidate for endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). Prior to ERCP, we consulted with gastroentrologists at our center and they proposed performing Magnetic Resonance Cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) and it revealed a filling defect at the mid CBD with proximal of the CBD being dilated to 12 mm (Fig. 1). ERCP reported mid CBD stenosis or impacted stone which was bypassed via an 8 cm 10f plastic stent and bile drainage was achieved. In order to locally investigate the lesion, Endoscopic Ultrasound (EUS) examination was performed which reported 16 × 12 mm isoechoic tumoral lesion at the middle of the CBD with three small stones proximal to the stent. In this regard, we decided to perform ERCP-guided brushing biopsy of the lesion. The pathology report was as follows: sheets and clusters of atypical cells with high nucleus to cytoplasm ratio and hyperchromatic nuclei which was highly suggestive for malignancy. At this stage, we assumed that we were facing klatskin tumor of the proximal of the CBD as it is the most probable malignant tumor of the CBD. A thoraco-abdomino-pelvic computed tomography scan was ordered to evaluate the extent of local invasion and distant metastasis. In addition to previously located tumor, there was a 30 × 38 mm low attenuated mass like lesion at antero-posterior aspect of pancreatic tail with normal splenic vasculatures and no regional adenopathy. The study was negative for liver or other organ metastasis.

Fig. 1.

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography images of common bile duct (CBD). Dilated proximal CBD measuring 12 millimetr is evident. The arrow shows filling defect in mid CBD.

At the time these evaluations were running, she became symptom free and tolerated food. This case was discussed in tumor board and it was decided to surgically resect the lesion after 6 weeks in order to decrease post pancreatitis complications. She was admitted at the scheduled time and underwent resection of the mid portion of the CBD with Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy, cholecystectomy, portahepatis lymph node dissection and excisional biopsy of the distal pancreas mass. The postoperative session was uneventful and she was discharged seven days after surgery. The pathology report indicated that CBD lesion was well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumor grade II with perineural and lympho-vascular invasion (Fig. 2). The immunohistochemistry study was positive for Synaptophysin and Chromogranin A. Ki67 index was positive in 8% of tumoral nuclei. One out of seven dissected lymph nodes was involved by tumor. The pancreatic lesion was fibroadipose tissue accompanied by dense histiocytic inflammation and no malignant lesion was seen. Also gallbladder specimen was negative for malignancy and manifested chronic cholecystitis and cholesterolosis. The patient was referred to oncologist for further adjuvant therapy based on cisplatin and etoposide. She underwent surgery on September 2017 and at the time of writing this article on October 2020 she was alive. This study has been reported in line with the SCARE 2018 criteria [5].

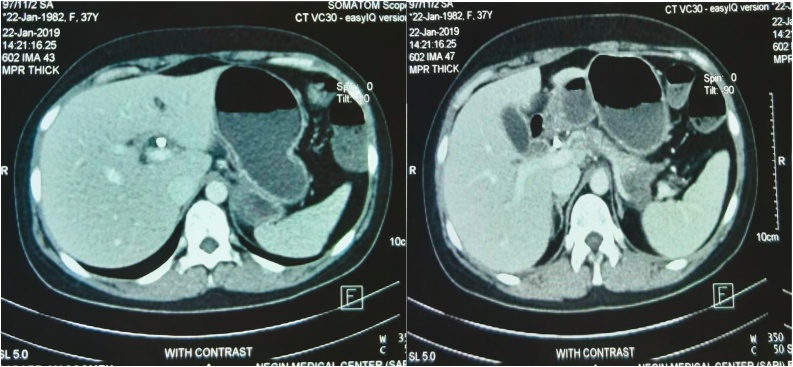

Fig. 2.

Computed Tomography scan images of the common bile duct.

Histologic features of well differentiated neuroendocrine tumor of CBD: A, B: Bile duct wall is infiltrated by tumor (H&E, 100×, 100×). C: Tumor cells show mild cytologic atypia, round to oval nuclei, stippled chromatin and eosinphilic to clear cytoplasm (H&E, 400×).

Immunohistochemical study of well differentiated neuroendocrine tumor of CBD: D,E: Immunohistochemical staining with Synaptophysin and Chromogranin is diffusely positive (IHC, 400×, 400×). F: KI-67 is positive in about 8 percent of tumoral nuclei (IHC, 100×).

3. Discussion

World Health Organization (WHO) classification [4] categorized neuroendocrine neoplasms of digestive tract into three subtypes: well differentiated neuroendocrine tumor (NET), poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma (NEC) and mixed adenoneuroendocrine carcinoma (MANEC) [6]. These neoplasms are different in histologic features and proliferation fraction. Well differentiated NETs are arranged in nests, clusters, trabeculae and acini and are composed of cells with uniform round nuclei, stippled chromatin and eosinophilic to clear cytoplasm. They are divided into three groups, including grade 1 (<2 mitoses/2mm2, Ki-67 < 3%), grade 2 (2–20 mitoses/2mm2, Ki-67:3% to 20%), grade 3 (>20 mitoses/2mm2, Ki-67 > 20%). A NEC is a poorly differentiated, high grade malignant neuroendocrine neoplasm composed of either small or intermediate to large cells with marked nuclear atypia and a high proliferation fraction (>20 mitoses per 10 high-power fields or > 20% Ki67 index) [7]. MANEC has histological features of both gland-forming epithelial and neuroendocrine carcinomas [8].

NETs are extremely rare accounting for 0.2–2% of all digestive tract tumors [9]. Recent years have witnessed an increase in the incidence of NETs (3.65 /100.000/year) which may be due to either actual increase in incidence or improved diagnostic tools [10]. The most common primary sites for extrahepatic bile duct NET are hepatic duct and distal CBD (19.2%) following by the middle of the CBD (17.9%), the cystic gall duct (16.7%) and the proximal of the CBD (11.5%) [3]. Michalopoulos et al. [11] reported approximately 38 cases of NET from 1961 to 2013. Also Liu et al. [12] found other 10 including their case and reported 48 cases of NET in 2018. It is not clear how NET develops in bile duct tissues but the most accepted theory is that cholelithiasis and congenital malformation of the biliary tract cause chronic inflammation with subsequent metaplasia of bile duct epithelial cells, and then metaplasia transforms into NET [13]. The definite diagnosis relies on postoperative pathology which utilized immunohistochemistry study on many biomarkers to diagnosis the histological subtypes of neuroendocrine neoplasms, such as Chromogranin A, Synaptophysin, Neuron specific enolase, and etc.

The NET, as it is named, has the potential to secrete numerous hormonal substances such as serotonin, gastrin, somatostatin, vasoactive intestinal peptide, glucagon and insulin but usually these substances are not measured through preoperative diagnosis course because of the absence of detectable serum markers and the usual lack of hormonal symptoms [11]. In Little et al. [14] case, urinary 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA) was measured preoperatively and lead to diagnosis. Also, gastrin serum level was found to be increased in Martignoni et al. study [15] [58, 92]. However our case did not show any symptoms rather than obstructive jaundice and abdominal discomfort.

Today, the technological advances has facilitated diagnosis of many tumors even in the sites of complex anatomy, however many cases of the NET cannot be diagnosed operative specimen is reviewed. Noronha et al. [16] suggested that brush cytology specimen obtained using ERCP, percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC) or endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration can provide preoperative histological result of malignancy. These techniques might have false negative results because the tumor is located submucosaly. We used ERCP to obtain histological confirmation of malignancy but the exact pathology was postponed until operative specimen was reviewed.

The principle differential diagnosis of NET is cholangiocarcinoma. NETs of the CBD are almost non-functioning thus initial presentation is jaundice and fever and abdominal discomfort may take time to develop [17,18]. Considering the fact that enhancement degree of CT in the arterial phase for cholangiocarcinoma is lower than for the liver and exophytic growth pattern of NET might be helpful separating these two entities [19].

Surgical resection is the mainstay of the treatment and the surgical extent is directed by the tumor location [20]. Lymph node dissection has been introduced to be a part of the surgery by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines, however the exact extent of dissection is not clearly defined [12]. As these tumors are not usually diagnosed prior to surgical removal, there is no neoadjuvant treatment proposed. Postoperative chemotherapy using cisplatin and etoposide showed promising results, however prognosis is mainly related to histological grade of the tumor [21].

4. Conclusion

Although current knowledge about NETs of the CBD is limited but it seems that combination of radical surgical resection and lymph node dissection followed by chemotherapy provides substantial prognosis.

Declaration of Competing Interest

All authors declare that there is no conflict of interest to disclose.

Funding

This study was not funded nor granted.

Ethical approval

Ethic committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences approved this study.

Consent

The patient gave written consent about her willingness to participate in the study after she was completely informed about study.

Author contribution

Seyed Rouhollah Miri M. D.: Conception and Design of the study

Ehsanollah Rahimi Movaghar. M. D.: Data collection and/or processing, Writing the paper

Masoomeh Safaei. M. D.: Analysis and/or interpretation

Amirsina Sharifi. M. D.: Critical review, Writing the paper, Supervision

Registration of research studies

N/A.

Guarantor

Ehsanollah Rahimi Movaghar. M. D.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned, externally peer-reviewed.

Acknowledgment

None.

References

- 1.Takahashi K. Well-differentiated endocrine carcinoma originating from the bile duct in association with a congenital choledochal cyst. Int. Surg. 2013;97(4):315–320. doi: 10.9738/CC152.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhalla P. Neuroendocrine tumor of common hepatic duct. Indian J. Gastroenterol. 2012;31(3):144–146. doi: 10.1007/s12664-012-0197-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hosoda K. Neuroendocrine tumor of the common bile duct. Surgery. 2016;160(2):525. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2016.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maitra A. Carcinoid tumors of the extrahepatic bile ducts: a study of seven cases. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2000;24(11):1501–1510. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200011000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Agha R.A. The SCARE 2018 statement: updating consensus Surgical CAse REport (SCARE) guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2018;60:132–136. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2018.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Komminoth P. International Agency for Research on Cancer; Lyon: 2010. Neuroendocrine Neoplasms of the Gallbladder and Extrahepatic Bile Ducts. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Digestive System; pp. 274–276. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klimstra D.S. The pathologic classification of neuroendocrine tumors: a review of nomenclature, grading, and staging systems. Pancreas. 2010;39(6):707–712. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181ec124e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abe T. Neuroendocrine tumor of the extrahepatic bile duct: a case report. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2017;40:6–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2017.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Modlin I.M., Sandor A. An analysis of 8305 cases of carcinoid tumors. Cancer. 1997;79(4):813–829. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19970215)79:4<813::aid-cncr19>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lawrence B. The epidemiology of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. North Am. 2011;40(1):1–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2010.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Michalopoulos N. Neuroendocrine tumors of extrahepatic biliary tract. Pathol. Oncol. Res. 2014;20(4):765–775. doi: 10.1007/s12253-014-9808-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu Z. Neuroendocrine tumor of the common bile duct: a case report and review of the literature. Onco. Ther. 2018;11:2295. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S162934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sasatomi E., Nalesnik M.A., Marsh J.W. Neuroendocrine carcinoma of the extrahepatic bile duct: case report and literature review. World J. Gastroenterol. 2013;19(28):4616. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i28.4616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Little J.M. Primary common bile-duct carcinoid. Br. J. Surg. 1968;55:147–149. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800550221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martignoni M.E. Study of a primary gastrinoma in the common hepatic duct–a case report. Digestion. 1999;60(2):187–190. doi: 10.1159/000007645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Noronha Y.S., Raza A.S. Well-differentiated neuroendocrine (carcinoid) tumors of the extrahepatic biliary ducts. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2010;134(7):1075–1079. doi: 10.5858/2008-0764-RS.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khan F.A. Extrahepatic biliary obstrution secondary to neuroendocrine tumor of the common hepatic duct. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2017;30:46–49. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2016.11.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoepfner L., White J.A. Primary extrahepatic bile duct neuroendocrine tumor with obstructive jaundice masquerading as a Klatskin tumor. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2017;2017(6):rjx104. doi: 10.1093/jscr/rjx104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hong N. Neuroendocrine neoplasms of the extrahepatic bile duct: radiologic and clinical characteristics. Abdom. Imaging. 2015;40(1):181–191. doi: 10.1007/s00261-014-0191-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yalav O. A rare cause of bile duct obstruction in adolescence: neuroendocrine tumor. Turk. J. Gastroenterol. 2014;25(Suppl 1):S311–S312. doi: 10.5152/tjg.2014.3565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iwasa S. Cisplatin and etoposide as first-line chemotherapy for poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma of the hepatobiliary tract and pancreas. Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010;40(4):313–318. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyp173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]