Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 has caused more than 10 million infections in the United States, and its associated disease, coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19), has unfortunately led to more than 240,000 deaths.1 There is growing recognition of significant racial disparities with COVID-19, and concern that Black and Hispanic individuals have a higher risk of infection and mortality from COVID-19.2

Chronic liver diseases (CLDs) are a major public health burden, and substantial racial disparities exist both in the prevalence and mortality from CLD in the United States.3 Recent studies have shown that patients with CLD in general, and especially those with decompensated cirrhosis and alcohol liver disease, are at higher risk COVID-19–related mortality.4 , 5 But the impact of race/ethnicity on COVID-19 among patients with CLD is not understood. Here, we present results from our multicenter US study, evaluating the social determinants of racial disparities in patients with CLD and COVID-19.

Methods

Study Design

This is a observational cohort study of adult patients with CLD and laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 from 21 centers across the United States after institutional review board approval. The inclusion and exclusion criteria have been previously published and more details including missing data analysis are presented in the supplementary section.5 , 6 We used the residential zip code to derive data on median income, poverty, and overcrowding from the US census. All analyses were performed using SPSS 26.0 (IBM Corp, Chicago, IL).

Results

Racial and Ethnic Distribution in Patients With CLD and COVID-19

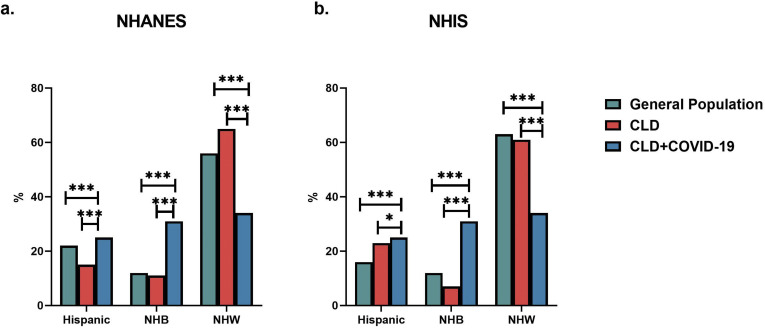

The study cohort included 909 patients with CLD and COVID-19, from 21 US centers. Information on race and ethnicity was available for 879 (96.7%) patients. The following is the race/ethnicity distribution in the cohort: Hispanic (n = 224 [25.5%]), non-Hispanic White (NHW, n = 297 [33.8%]), non-Hispanic Black (NHB, n = 276 [31.4%]), non-Hispanic Asian (NHA, n = 44 [5.0%]) and non-Hispanic American Indian (NHAI, n = 11 [1.2%]). Compared with the general population or patients with CLD, in 2 large national cohorts, NHB individuals (P < .0001 for both National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey7 and National Health Interview Survey8) and Hispanic individuals (P < .0001 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey and P = .05 National Health Interview Survey) are disproportionately overrepresented in the cohort of patients with CLD with COVID-19 (Supplementary Figure 1).

Supplementary Figure 1.

Comparison of racial and ethnic distribution of patients with CLD in national database cohorts with patients with CLD and COVID-19. ∗P < .05, ∗∗∗P < .0001. NHANES, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Data from 2013–2016; NHIS, National Health Interview Survey. Data from 2018.

We stratified demographic/clinical features of patients with CLD and COVID-19 by race/ethnicity (Table 1 ). Hispanic patients with CLD were younger (P < .001) and more likely to be female (P = .01). Diabetes was more prevalent in Hispanic individuals (odds ratio [OR] 1.5 [1.1–2.1]), and in addition, hypertension in NHB individuals (OR 2.1 [1.5–2.9]). Hispanic patients did have a higher rate of hospitalization compared with NHW individuals (OR 1.7 [1.2–2.4]); however, we did not observe differences in oxygen requirement, intensive care unit admission, mechanical ventilation, or mortality between NHW individuals and other race/ethnicities.

Table 1.

Comparison of Demographic, Clinical and Socioeconomic Factors in Patients With CLD and COVID-19 Stratified by Race and Ethnicity

| Variable | Class | NHW (n = 297, 33.8%) | NHB (n = 276, 31.4%) | Hispanic (n = 224, 25.5%) | NHW vs NHB | NHW vs Hispanic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Median (IQR) | 59.5 (50.0–66.0) | 60.0 (51.0–68.0) | 53.5 (41.0– 64.0) | .48 | < .001 |

| Age (>65 y) | 97 (32.7) | 101 (36.6) | 51 (22.8) | .32 | .01 | |

| Gender | Male | 179 (60.5) | 144 (52.2) | 111 (49.6) | .045 | .01 |

| Female | 117 (39.5) | 132 (47.8) | 113 (50.4) | |||

| Comorbidities | Diabetes mellitus | 111(37.4) | 133 (48.2) | 106 (47.3) | .009 | .02 |

| Hypertension | 159 (53.5) | 195 (70.7) | 109 (48.7) | < .001 | .27 | |

| Hyperlipidemia | 135 (45.5) | 115 (41.7) | 75 (33.5) | .36 | .006 | |

| Obesity | 141 (47.5) | 117 (42.4) | 97 (43.3) | .22 | .34 | |

| CAD | 35 (11.8) | 28 (10.1) | 23 (10.3) | .53 | .59 | |

| CHF | 29 (9.8) | 37 (13.4) | 8 (3.6) | .17 | .006 | |

| COPD | 34 (11.4) | 27 (9.8) | 7 (3.1) | .52 | < .001 | |

| Cancer | 27 (9.1) | 20 (7.2) | 14 (6.3) | .42 | .23 | |

| Tobacco use | Never smoker | 145 (48.8) | 151 (54.7) | 141 (62.9) | .24 | .001 |

| Former/Current smoker | 144 (48.5) | 121 (43.8) | 74 (33.0) | |||

| Missing | 8 (2.7) | 4 (1.4) | 9 (4.0) | |||

| Alcohol use | No | 170 (57.2) | 173 (62.7) | 149 (66.5) | .21 | .04 |

| Yes | 108 (36.4) | 87 (31.5) | 62 (27.7) | |||

| Missing | 19 (6.4) | 16 (5.8) | 13 (5.8) | |||

| CLD stage | No cirrhosis | 206 (71.5) | 205 (74.8) | 159 (72.6) | .38 | .79 |

| Compensated cirrhosis | 40 (13.9) | 47 (17.2) | 38 (17.4) | .29 | .28 | |

| Decompensated cirrhosis | 42 (14.6) | 22 (8.0) | 22 (10.0) | .01 | .13 | |

| CLD etiology | Alcohol liver disease | 33 (11.1) | 19 (6.9) | 32 (14.3) | .11 | .95 |

| Chronic hepatitis B | 8 (2.7) | 28 (10.1) | 6 (2.7) | .001 | .88 | |

| Chronic hepatitis C | 55 (18.5) | 97 (35.1) | 24 (10.7) | < .001 | < .001 | |

| NAFLD | 181 (60.9) | 109 (39.5) | 144 (64.3) | < .001 | .85 | |

| Other | 20 (6.7) | 23 (8.3) | 18 (8.0) | .47 | .57 | |

| HCC | Yes | 10 (3.4) | 4 (1.4) | 6 (2.7) | .18 | .65 |

| Outcomes | Hospitalization | 159 (53.5) | 153 (55.4) | 147 (65.6) | .64 | .005 |

| Supplemental oxygen | 140 (47.1) | 130 (47.1) | 118 (52.7) | .93 | .13 | |

| ICU admission | 62 (20.9) | 62 (22.5) | 52 (23.2) | .68 | .50 | |

| Vasopressor use | 37 (12.5) | 42 (15.2) | 35 (15.6) | .31 | .28 | |

| Mechanical ventilation | 46 (15.5) | 51 (18.5) | 37 (16.5) | .35 | .73 | |

| COVID-19 mortality | 44 (15.0) | 35 (12.9) | 28 (12.7) | .47 | .46 | |

| All-cause mortality | 52 (17.7) | 41 (15.1) | 28 (12.7) | .40 | .12 | |

| 30-day survival | 84% | 89% | 89% | .39 | .30 | |

| Telehealth visit | Yes | 149 (51.2) | 116 (42.3) | 92 (41.3) | .03 | .03 |

| Insurancea | Medicare/Medicaid | 151 (50.8) | 171 (62.0) | 126 (56.3) | .007 | .22 |

| Private insurance | 139 (46.8) | 89 (32.2) | 66 (29.5) | < .001 | < .001 | |

| Uninsured | 8 (2.7) | 12 (4.3) | 20 (8.9) | .28 | .002 | |

| Missing | 3 (1.0) | 5 (1.8) | 8 (3.6) | .49 | .06 | |

| Type of housing | Single-family home | 174 (58.6) | 131 (47.5) | 106 (47.3) | .008 | .01 |

| Multifamily housing | 57 (19.2) | 97 (35.1) | 89 (39.7) | < .001 | < .001 | |

| Skilled nursing facility | 27 (9.1) | 12 (4.3) | 13 (5.8) | .02 | .16 | |

| Homeless/Shelter | 12 (4.0) | 10 (3.6) | 3 (1.3) | .99 | .07 | |

| Long-term care facility | 15 (5.1) | 4 (1.4) | 7 (3.1) | .03 | .38 | |

| Missing | 12 (4.0) | 22 (8.0) | 6 (2.7) | .047 | .40 | |

| Number of people at home | 1–2 | 107 (74.8) | 64 (68.1) | 70 (46.1) | .26 | < .001 |

| 3–4 | 34 (23.8) | 23 (24.5) | 59 (38.8) | .90 | .005 | |

| 5 or more | 2 (1.4) | 7 (7.4) | 23 (15.1) | .03 | < .001 | |

| Missing | 154 (51.9) | 182 (65.9) | 72 (32.1) | .001 | < .001 | |

| Risk factor for COVID-19 | Contact with sick person | 86 (29.0) | 64 (23.2) | 92 (41.1) | .12 | .004 |

| Recent travel | 10(3.4) | 4 (1.4) | 5 (2.2) | .18 | .60 | |

| Recent hospitalization | 38 (12.8) | 30 (10.9) | 17 (7.6) | .48 | .06 | |

| Nursing home stay | 37 (12.5) | 19 (6.9) | 15 (6.7) | .03 | .03 | |

| Household income ($) | Median (IQR) | 70,039 (56250–95187) | 59,807 (50756–72850) | 56,250 (40866–75173) | < .001 | < .001 |

| Poverty (%) | Median (IQR) | 10.5 (6.55–16.4) | 18.3 (14.4–27.1) | 19.0 (12.2–27.7) | < .001 | < .001 |

| Overcrowding (%) | Median (IQR) | 1.9 (1.0–3.1) | 2.4 (1.6–3.9) | 9.6% (4.3–14.1) | < .001 | < .001 |

NOTE. Statistically significant P values are in bold.

CAD, coronary artery disease; CHF, congestive heart failure; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ICU, intensive care unit; IQR, interquartile range; NAFLD, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease.

Some patients had both Medicare/Medicaid and private insurance.

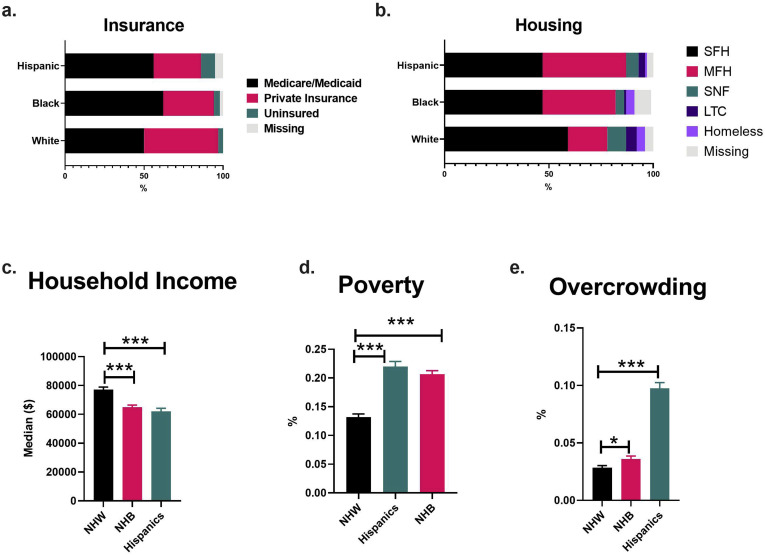

Socioeconomic Disparities Based on Race/Ethnicity

To understand the socioeconomic disparities, we compared medical insurance status, housing, and median household income between the different races/ethnicities. We found that patients with private insurance were less likely to be NHB or Hispanic compared with NHW (OR 0.5 [0.4–0.8] and OR 0.5 [0.3–0.7], respectively), whereas NHB and Hispanic individuals had a higher odds of having Medicare/Medicaid (OR 1.6 [1.1–2.2]) or being uninsured (OR 3.5 [1.5–8.2]), respectively.

On comparison of housing status, individuals in multifamily housing were more likely to be NHB (OR 2.3 [1.6–3.3]) or Hispanic (OR 2.8 [1.9–4.1]). NHW individuals were more likely to reside in single-family housing or nursing homes at the time of COVID-19 diagnosis. Furthermore, Hispanic and NHB individuals were more likely to reside with 5 or more members at home, but data were only partially available for this variable. However, Hispanic individuals did have higher odds of acquiring COVID-19 from a sick contact (P = .004).

To further expand our analysis, we derived social metrics from census data based on residential zip code. We found that both NHB and Hispanic individuals lived in neighborhoods with a lower median household income ($60K [$50–$72K] and $56K [$41–$75K] vs $70K [$56–$95K]; P < .001); and higher rates of poverty (P < .0001 both) and overcrowding (P < .0001 both) than NHWs. Thus, our data show that NHB and Hispanic patients with CLD and COVID-19 face significant socioeconomic disparities (Supplementary Figure 2).

Supplementary Figure 2.

Comparison of socioeconomic factors between patients with CLD and COVID-19 stratified by race and ethnicity. Household income, rate of poverty, and overcrowding derived from American Community Survey zip code data. LTC, long-term care housing; MFH, multifamily housing; SFH, single family house; SNF, skilled nursing facility.

Discussion

In this large multicenter US cohort, we show that NHB and Hispanic individuals are disproportionately represented in patients with CLD who acquire COVID-19, similar to what has been shown in the general population. Inequities in social determinants of health, like type of housing, median household income, and access to health care have been posited to drive the observed disparities. However, data quantifying these disparities have been scarce. In this study, we describe the social and economic inequities in racial and ethnic minorities with CLD and COVID-19. Both NHB and Hispanic individuals had lower household income and lower rates of private insurance, and Hispanic individuals had higher rates of being uninsured. In addition, we show that both NHB and Hispanic individuals had higher likelihood of living in multifamily housing and in neighborhoods with higher rates of poverty and overcrowding than NHW individuals. Thus, our study sheds light on important socioeconomic factors potentially contributing to the higher risk of COVID-19 in Black and Hispanic individuals.

Although other studies have suggested that race and ethnicity predict poor outcomes with COVID-19, we have shown they are not independent predictors of survival in patients with CLD, after adjusting for age, medical comorbidities, and liver-related factors.5 Compared with NHW individuals, Hispanic individuals had a higher prevalence of comorbidities like diabetes, hypertension, and obesity, but, conversely, were younger and had lower rates of known risk factors for COVID-19–related mortality like decompensated cirrhosis or alcohol use,4 which likely mitigated the adverse outcomes.

Our study has limitations, including selection bias and missing data. However, we provide valuable multicenter data on the stark socioeconomic disparities that exist in NHB and Hispanic communities and increase their risk for acquiring COVID-19. A deeper understanding of these disparities in social determinants of health will be helpful to prevent the spread of COVID-19 in patients with CLD belonging to these vulnerable communities.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge all of the members of the COLD consortium who made this work possible, including Nyann Latt, Sonal Kumar, Patricia P. Bloom, Ponni Perumalswami, Marina Roytman, Michael Li, Alexander S. Vogel, Costica Aloman, Vincent Chen, Atoosa Rabiee, Brett Sadowski, Veronica Nguyen, Winston Dunn, Kenneth Chavin, Kali Zhou, Blanca Lizaola-Mayo, Akshata Moghe, José Debes, Tzu-Hao Lee, Andrea Branch, Kathleen Viveiros, Walter Chan, David Chascsa, Paul Kwo, Zoe Reinus, Michael Daidone, Julia Sjoquist, Faruq Pradhan, Mohanad Al-Qaisi, Nael Haddad, Nicholas Blackstone, Marx, Katherine, McDermott,Susan, Alyson Kaplan, Mallori Ianelli, Julia Speiser, Angela Wong, Dhuha Alhankawi, Sunny Sandhu, Sameeha Khalid, Aalam Sohal, and Christina Gainey.

We also thank all first responders, who continue to be our heroes in this pandemic.

CRediT Authorship Contributions

Nia Adeniji, MEng (Conceptualization: Lead; Formal analysis: Lead; Writing andemic.So draft: Lead)

Rotonya Carr, MD (Conceptualization: Supporting; Data curation: Equal; Writing m review & editing: Supporting)

Elizabeth Aby, MD (Data curation: Equal; Methodology: Supporting; Writing ting mic.S editing: Supporting)

Andreaa Catana, MD (Data curation: Equal; Methodology: Supporting; Writing i review & editing: Supporting)

Kara Wegermann, MD (Data curation: Equal; Methodology: Supporting; Writing W review & editing: Supporting)

Renumathy Dhanasekaran, MD (Conceptualization: Lead; Formal analysis: Supporting; Writing ion: Lead; Formal analysi

Footnotes

Conflict of interest The authors disclose no conflicts.

Funding None.

Note: To access the supplementary material accompanying this article, visit the online version of Gastroenterology at www.gastrojournal.org, and at https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2020.11.035.

Supplementary Methods

Study Design

This is a multicenter observational cohort study. A consortium of investigators from 21 centers across the United States to study COVID-19 in CLD was formed on April 14, 2020 (registered Clinicaltrials.gov NCT04439084). The study was approved by the institutional review board of each participating center. The study inclusion criteria were as follows: age older than 18 years, laboratory-confirmed diagnosis of COVID-19, and presence of preexisting CLD (identified using International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision codes and confirmed by manual chart review). Patients who had undergone liver transplantation were excluded. The study retrospectively identified cases diagnosed between March 1 and April 14, 2020, and subsequent cases diagnosed with COVID-19 between April 15 and May 30, 2020, were identified prospectively. All data were collected until death or date of last follow-up. Death was attributed to COVID-19 if it was clinically related to COVID-19 illness and there were no other unrelated causes of death. The mean follow-up of the study was 69.5 days (range 192 days).

Data Collection

The diagnosis of cirrhosis was confirmed by documentation of fibrosis either by magnetic resonance elastography, FibroScan, fibrosis-4 index for liver fibrosis, or biopsy, which was available in 75% of patients. Diagnosis of cirrhosis was ascertained in other patients by detailed chart review for clinical, radiological, or biochemical evidence of liver cirrhosis.

To analyze the racial and ethnic distribution in patients with CLD, we used 2 large national database cohorts. The first one is the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, a survey that assesses the health and nutritional status of adults in the United States (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes). The second one is the National Health Interview Survey, which is a data collection program conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to monitor the health of the US population (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis).

Next, chart review was performed to collect data on race/ethnicity, type of medical insurance, type of residence, and number of household members at the time of COVID-19 diagnosis. Hispanic was defined to include both white and nonwhite Hispanic individuals. We had zip code data available on 90.5% of the cohort. We used the zip code of residence to derive the inflation-adjusted median household income from the US census data.12 To define the socioeconomic factors, poverty and crowding, we used the methods described in the “Public Health Disparities Geocoding Project” (https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/thegeocodingproject/covid-19-resources/) and the American Community Survey for 2018 (https://www.census.gov/data.html). Poverty status is determined by comparing annual income with the poverty thresholds defined based on family size, number of children, and the age of the householder. Crowding is defined by using the threshold of >1 person per room.

Statistical Analysis

We have presented continuous variables as medians and interquartile ranges or mean and standard deviation, as appropriate. We have summarized categorical variables as counts and percentages. We evaluated the statistical significance of differences between groups using the independent t-test or the Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables, and the χ2 test for categorical variables. For survival data, we performed Kaplan-Meier analysis for all-cause mortality. We performed sensitivity analysis using only patients for whom complete socioeconomic data were available (n = 795, 90.4%). In addition, to avoid case deletion in primary adjusted analysis due to missing data on baseline covariates, missing data were imputed by multiple imputations (m = 5) using linear regression for continuous variables and logistic regression model for binary variables. We then performed statistical analyses on this completed data set. Both analyses confirmed our primary findings that NHB and Hispanic individuals had lower household income, lower rates of private insurance, higher likelihood of living in multifamily housing and in neighborhoods with lower median household income, higher rates of poverty, and higher rates of overcrowding than NHW individuals (Supplementary Table 1).

Supplementary Table 1.

Sensitivity Analysis for Missing Socioeconomic Data in CLD and COVID-19

| Variable | Class | Complete data analysis |

Multiple imputation analysis |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NHW vs NHB | NHW vs Hispanic | NHW vs NHB | NHW vs Hispanic | ||

| Insurance∗ | Medicare/Medicaid | .032 | .449 | .009 | .224 |

| Private Insurance | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | |

| Uninsured | .027 | <.001 | .363 | .003 | |

| Type of housing | SFH | .004 | .015 | .034 | .004 |

| MFH | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | |

| SNF | .212 | .595 | .299 | .121 | |

| Homeless/Shelter | .824 | .109 | .838 | .109 | |

| LTC facility | .080 | .232 | .019 | .186 | |

| Household income ($) | Median (IQR) | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| Poverty (%) | Median (IQR) | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| Overcrowding (%) | Median (IQR) | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 |

NOTE. Statistically significant P values are in bold.

IQR, interquartile range; LTC, long-term care housing; MFH, multifamily housing; SFH, single family house; SNF, skilled nursing facility.

References

- 1.CDC 2020. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/ Available at:

- 2.Moore J.T. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1122–1126. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6933e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nguyen G.C. Hepatology. 2008;47:1058–1066. doi: 10.1002/hep.22223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marjot T. J Hepatol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2020.09.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim D. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.09.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rabiee A. Hepatology. 2020 doi: 10.1002/hep.31574. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Younossi Z.M. Gut. 2020;69:564–568. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-318813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) 2020. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/shs.htm.