Key Points

Question

What is the association between low-dose aspirin use and risk of colorectal cancer (CRC) in an East Asian population?

Findings

In this nested case-control study among 4 710 504 participants in Taiwan, low-dose aspirin use was associated with 11% lower risk of CRC among those aged 40 years or older, regardless of duration and recency of drug use. A 30% lower CRC risk was observed when low-dose aspirin was initiated between age 40 and 59 years.

Meaning

In this study, low-dose aspirin use was associated with lower CRC risk, and this association was larger when use started before age 60 years.

This nested case-control study evaluates the association between duration and recency of low-dose aspirin use and colorectal cancer risk in an East Asian population.

Abstract

Importance

Population-based East Asian data have corroborated reports from non-Asian settings on the association between low-dose aspirin and a lower risk of colorectal cancer (CRC).

Objective

To evaluate the association between duration and recency of low-dose aspirin use and CRC risk.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This nested case-control study included individuals who initiated aspirin use and matched individuals who did not use aspirin. Data were collected from Taiwan National Health Insurance and Taiwan Cancer Registry from 2000 through 2015. CRC cases were age- and sex-matched in a 1:4 ratio with individuals in a control group, identified from a cohort of individuals who used and did not use aspirin through risk-set sampling. Data analysis was conducted from June 2018 to July 2019.

Exposures

Low-dose aspirin use was defined as receiving less than 150 mg per day, whereas 100 mg/d was most commonly used. Based on duration and recency of low-dose aspirin use between cohort entry (initiation date of low-dose aspirin for aspirin use group or randomly assigned date for those who did not use aspirin) and index date (CRC diagnosis date for individuals in the case group and the diagnosis date for the 4 corresponding matched individuals in the control group), the 3 following mutually exclusive exposure groups served as the basis for analysis: (1) long-term current low-dose aspirin use, (2) episodic low-dose aspirin use, and (3) no low-dose aspirin use (the reference group).

Main Outcomes and Measures

CRC risk among the 3 exposure groups.

Results

Among 4 710 504 individuals (2 747 830 [51.7%] men; median [interquartile range] age at cohort entry in initiator group, 61 [52-71] years; median [interquartile range] age at cohort entry in nonuse group, 59 [51-68] years), 79 095 CRC cases (1.7% of study cohort) were identified. Compared with no low-dose aspirin use, the adjusted odds ratio (OR) for long-term current low-dose aspirin use and CRC risk was 0.89 (95% CI, 0.85-0.93); for episodic use, 0.88 (95% CI, 0.86-0.89). Adjusted ORs of 0.69 (95% CI, 0.63-0.76) and 0.64 (95% CI, 0.61-0.67) were observed for long-term current use and episodic low-dose aspirin use within the subcohort of individuals who initiated low-dose aspirin between age 40 and 59 years.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this study, low-dose aspirin use was associated with 11% lower CRC risk in an East Asian population, and this association was larger when low-dose aspirin use started before age 60 years.

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) incidence in Asia has increased in recent years.1 While the effects of low-dose aspirin use in reducing CRC risk have been studied extensively in Western populations,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12 evidence from East Asia has been limited, with 3 moderate-sized studies reported from Taiwan.13,14,15 Studies from Western countries reported 13% to 42% lower CRC risk associated with low-dose aspirin use, and some findings suggested larger risk reduction associated with longer duration of aspirin use.3,8,16 Furthermore, low-dose aspirin use was associated with lower risk of advanced stage CRC.12 The association between low-dose aspirin use and different stages of CRC has not been evaluated in an East Asian population. With the need for more robust evidence on low-dose aspirin use and cancer risk in East Asia, we conducted a nested case-control study to evaluate the association between duration and recency of low-dose aspirin use and CRC risk overall and by CRC stages.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

This is a nested case-control study using the Taiwan National Health Insurance (NHI),17,18 Taiwan Cancer Registry (TCR),19,20 and mortality data from 2000 through 2015. The NHI is a publicly funded single-payer health insurance program for all Taiwan residents and captures reimbursement records for outpatient and emergency department visits, hospitalizations, prescription drugs, and procedures. The TCR is a registry of all incident cancer cases diagnosed in hospitals with at least 50 beds and has information on date of diagnosis as well as pathology cell type and cancer stage according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer definitions.20 The study was approved by the National Taiwan University Hospital Research Ethics Committee with a waiver of informed consent because deidentified data were used. The report was prepared according to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline for cohort and case-control studies.21

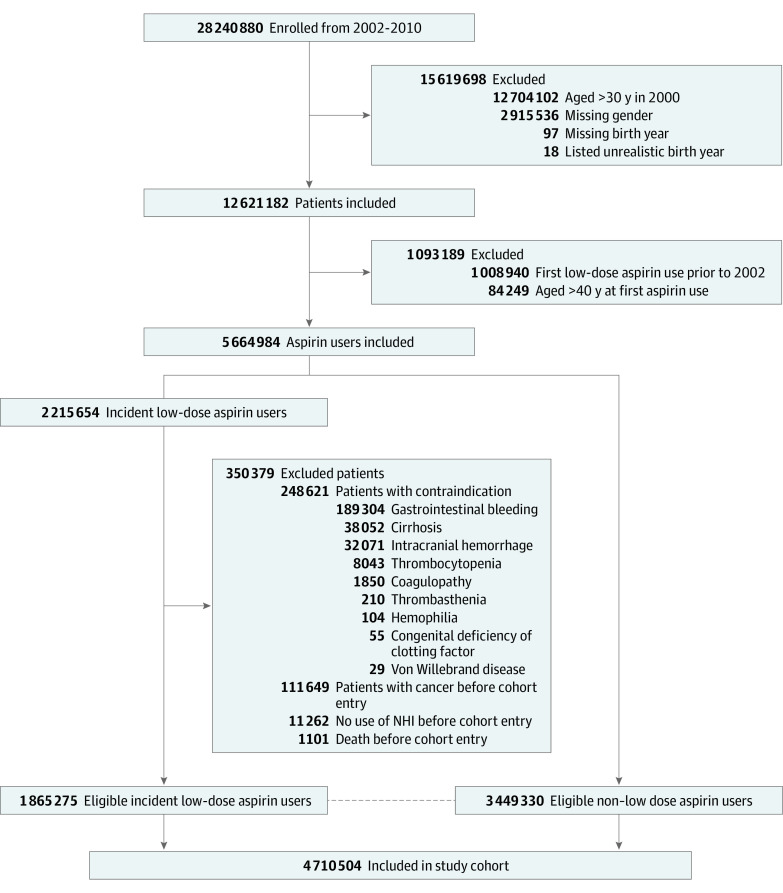

The study cohort included individuals aged 40 years or older who initiated low-dose aspirin and individuals who did not use aspirin who were age (by 10-year groups) and sex frequency matched in a 2:1 ratio annually from 2002 to 2010. In Taiwan, low-dose aspirin is a prescription drug indicated for cardiovascular disease prevention and is not available over the counter; its prescriptions are captured in the NHI. Cohort entry date was the first low-dose aspirin prescription for the initiator group and random dates within the same year for the nonuse group. Participants who died, had no NHI claims, had cancer, or had aspirin contraindications before cohort entry date were not eligible for frequency matching. Participants with history of aspirin use before 2002 were also excluded (Figure). Participants who were identified and matched in the nonuse group in an earlier calendar year and subsequently initiated low-dose aspirin would cross over to the aspirin cohort.

Figure. Flowchart of Study Cohort .

NHI indicates National Health Insurance.

CRC Cases and Risk-Set Sampling for Controls

CRC cases from 2002 through 2015 were ascertained through TCR. Risk-set sampling was used to identify individuals for the control group for each CRC case, and potential members of the control group were cohort members at risk of developing CRC at the time when the CRC case was diagnosed. A total of 4 individuals with the same sex and age (±1 year) as an individual in the case group were randomly selected from the risk set and included in the control group. For the 1 individual in the case group and the 4 individuals in the control group in each case/control quintet, the index date was the date of CRC diagnosis.

Aspirin Use and Covariates

A number of aspirin dosage forms are available in Taiwan, and we operationally defined low-dose aspirin use as receiving less than 150 mg per day. The 100 mg formulation given once a day was used most frequently. According to aspirin exposure before the index date, 3 mutually exclusive exposure groups were formed: (1) long-term current use of low-dose aspirin (ie, most recent use within 1 year before index date, ≥3 years of low-dose aspirin use, and >70% drug-day coverage during a 3-year look-back period from index date); (2) episodic uses of low-dose aspirin (ie, last use of aspirin >1 year from index date or <70% drug-day coverage during 3-year look-back time from index date); and (3) nonuse (ie, no low-dose aspirin use before index date). In addition, low-dose aspirin use for extended periods was evaluated regarding whether the 70% drug-day coverage threshold was reached within the specific duration prior to the index date; for instance, low-dose aspirin drug-day should exceed 70% of the 5-year period prior to index date to be considered having at least 5 years of low-dose aspirin exposure. The 70% threshold was adopted after descriptive assessment of low-dose aspirin use in NHI during study protocol development. The association of low-dose aspirin discontinuation and CRC risk was evaluated among patients whose last low-dose aspirin prescription was at least 1 year prior to index date, with individuals in the long-term current use group used as reference.

Baseline characteristics for the study cohort included age, sex, comorbidities, concomitant medications, health care utilization (number of hospitalizations and outpatient and emergency visits), aspirin indications (study cohort), and CRC stages (for patients with CRC). Potential confounders were evaluated 1 year before the index date, and they included single point exposure of higher-dose aspirin formulations (used as analgesic or antipyretic), gastrointestinal bleeding, peptic ulcer, ulcerative colitis, Crohn disease, familial adenomatous polyposis, and colonoscopy. Prior use of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitors, nonsteroid anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), statins, antidiabetic agents, antihypertensive agents, antacids, gastrointestinal cholinergic antagonists, and health care utilization during the previous year were also evaluated.

Statistical Analysis

We described baseline characteristics during a 1-year look-back period before cohort entry date among study cohort members and before index date for individuals in the case and control groups. Continuous variables were described with mean and SD or median and interquartile range (IQR). Conditional logistic regression was used to evaluate the association between CRC and groups of low-dose aspirin use, with nonuse as the reference group, while controlling for the covariates mentioned earlier. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% CIs were estimated. CRC stage–specific analyses were carried out for participants whose staging information was available. All analyses were performed using SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute). No statistical testing was conducted, so no prespecified level of significance was set.

After the study protocol was finalized and on review of recently published reports, we repeated the analyses in a subcohort of participants who initiated low-dose aspirin between age 40 to 59 years. Sensitivity analysis was performed among individuals in the case and control groups without NSAID or COX-2 inhibitors use 3 years prior to index date to minimize confounding effects of anti-inflammation agents on CRC risk.

Results

Participants

The study cohort comprised 4 710 504 individuals, 2 747 830 (51.7%) were men, and the median (IQR) age was 61 (52-71) years among those in the low-dose aspirin initiator group and 59 (51-68) years in the nonuse group (Table 1). Among the 3 449 330 individuals in the nonuse group, 604 101 (17.5%) subsequently initiated low aspirin. More than 75% of low-dose aspirin use (1 468 352 of 1 865 275 [78.7%]) was initiated in ambulatory care clinics, and 1 647 042 patients (88.3%) had no cardiovascular indications recorded in health insurance claims before the initiation of aspirin. Among those in the low-dose aspirin initiator group with an apparent indication, the most common prior diagnoses were angina, ischemic stroke, and peripheral vascular disease. In comparison with the nonuse group, the low-dose aspirin initiator group had a higher prevalence of heart failure, hypertension, diabetes, and liver failure, and the differences were also reflected in concomitant medications and number of visits to health care facilities.

Table 1. Study Cohort Baseline Characteristics, 1 Year Prior to Cohort Entry Date.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full study cohort | Subcohort of individuals aged 40-59 y | |||

| Low-dose aspirin initiator group (n = 1 865 275) | Nonuse group (n = 3 449 330) | Low-dose aspirin initiator group (n = 547 068) | Nonuse group (n = 1 094 136) | |

| Men | 962 103 (51.6) | 1 785 717 (51.8) | 286 165 (52.3) | 572 330 (52.3) |

| Age | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 62 (12.3) | 59 (11.6) | 51 (5.3) | 50 (5.3) |

| Median (IQR) | 61 (52-71) | 59 (51-68) | 51 (46-55) | 51 (45-54) |

| Cardiovascular indications at any time prior to cohort entry date | ||||

| Ischemic stroke | 49 126 (2.6) | 33 810 (1.0) | 7059 (1.3) | 3998 (0.4) |

| Transient ischemic attack | 11 778 (0.6) | 7707 (0.2) | 1878 (0.3) | 982 (0.1) |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 7570 (0.4) | 3942 (0.1) | 1361 (0.3) | 405 (0.0) |

| Angina | 108 713 (5.8) | 66 958 (1.9) | 20 643 (3.8) | 10 012 (0.9) |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 57 864 (3.1) | 44 702 (1.3) | 9286 (1.7) | 6269 (0.6) |

| Revascularization | 3465 (0.2) | 2258 (0.1) | 568 (0.1) | 335 (0.6) |

| Stent | 1691 (0.1) | 362 (0.0) | 421 (0.1) | 29 (0.0) |

| Angioplasty | 2100 (0.1) | 682 (0.0) | 244 (0.0) | 69 (0.0) |

| Secondary prevention | 218 233 (11.7) | NA | 38 590 (7.1) | NA |

| Primary preventiona | 1 647 042 (88.3) | NA | 508 478 (92.9) | NA |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Congestive heart failure | 59 711 (3.2) | 30 729 (0.9) | 939 (0.2) | 3182 (0.3) |

| Hypertension | 774 363 (41.5) | 589 600 (17.1) | 185 146 (33.8) | 97 624 (8.9) |

| Diabetes | 347 769 (18.6) | 257 957 (7.5) | 86 320 (16.0) | 47 706 (4.4) |

| Kidney failure | 33 846 (1.8) | 21 194 (0.6) | 7264 (1.3) | 3383 (0.3) |

| Mild liver disease | 127 940 (6.9) | 145 211 (4.2) | 45 704 (8.4) | 46 977 (4.3) |

| Moderate or severe liver disease | 312 (0.0) | 271 (0.0) | 93 (0.0) | 69 (0.0) |

| Concomitant medications | ||||

| NSAID | 1 320 149 (70.8) | 1 981 676 (57.5) | 399 491 (73.0) | 637 033 (58.2) |

| Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor | 109 255 (5.9) | 116 482 (3.4) | 10 403 (1.9) | 10 057 (0.9) |

| Diuretics | 110 069 (5.9) | 82 726 (2.4) | 23 816 (4.4) | 14 620 (1.3) |

| β blocker | 562 675 (30.2) | 422 771 (12.3) | 165 160 (30.2) | 99 407 (9.1) |

| Calcium channel blocker | 689 995 (37.0) | 484 919 (14.1) | 161 410 (29.5) | 78 019 (7.1) |

| ACEI | 323 946 (17.4) | 214 744 (6.2) | 85 419 (15.6) | 39 014 (3.6) |

| ARB | 244 197 (13.1) | 152 546 (4.4) | 50 829 (9.3) | 23 021 (2.1) |

| Statin | 194 973 (10.5) | 143 263 (4.2) | 47 871 (8.8) | 26 071 (2.4) |

| Insulin | 65 232 (3.5) | 32 230 (0.9) | 15 304 (2.8) | 5557 (0.5) |

| Metformin | 258 452 (13.9) | 182 368 (5.3) | 65 237 (11.9) | 33 954 (3.1) |

| Sulfonylurea | 288 704 (15.5) | 210 248 (6.1) | 75 612 (13.8) | 40 329 (3.7) |

| Thiazolindinedione | 51 313 (2.8) | 32 085 (0.9) | 13 574 (2.5) | 6225 (0.6) |

| DPP-4 inhibitor | 3048 (0.2) | 1696 (0.1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| GLP-1 analogue | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| PPI, oral | 59 858 (3.2) | 74 582 (2.2) | 14 450 (2.6) | 18 217 (1.7) |

| H2 blocker, oral | 435 570 (23.4) | 586 866 (17.0) | 128 248 (23.4) | 179 711 (16.4) |

| Outpatient visits | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 20 (17.4) | 12 (13.8) | 17 (15.4) | 10 (11.1) |

| Median (IQR) | 15 (8-27) | 8 (3-17) | 13 (7-23) | 6 (2-14) |

| Hospitalization episodes | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 0.17 (0.54) | 0.08 (0.36) | 0.13 (0.47) | 0.06 (0.3) |

| Median (IQR) | 0 (0-0) | 0 (0-0) | 0 (0-0) | 0 (0-0) |

| Total admission days | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 12 (30.7) | 13 (63.2) | 12 (45.3) | 14 (79.1) |

| Median (IQR) | 6 (3-11) | 5 (3-10) | 5 (3-10) | 4 (3-8) |

| Emergency department visits | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 0.36 (0.98) | 0.17 (0.57) | 0.33 (0.96) | 0.15 (0.54) |

| Median (IQR) | 0 (0-0) | 0 (0-0) | 0 (0-0) | 0 (0-0) |

Abbreviations: ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; DPP-4, dipeptidyl peptidase-4; GLP-1, glucagon-like peptide-1; H2, histamine 2 receptor; IQR, interquartile range; NA, not applicable; NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; PPI, proton pump inhibitor.

Low-dose aspirin prescriptions were considered for primary prevention if there were no cardiovascular-related disease diagnoses prior to cohort entry date.

Among the study cohort, 547 068 patients (11.6%) initiated low-dose aspirin at the age of 40 to 59 years, and 1 094 136 age-sex frequency-matched individuals who did not use aspirin were identified; 145 131 (13.3%) in the nonuse group subsequently initiated low-dose aspirin, resulting in study size of 1 496 073. Among them, median (IQR) age for the low-dose aspirin initiator group and the nonuse group was 51 (46-55) years and 50 (45-54) years, respectively. Angina and peripheral vascular diseases were the most likely reasons for the subcohort patients to initiate low-dose aspirin; 508 478 (92.9%) of the low-dose aspirin initiator group from the subcohort had no cardiovascular indications before initiating low-dose aspirin. Baseline characteristics of the subcohort were generally similar to the full study cohort study but with a lower proportion of the low-dose aspirin initiator group having hypertension in the subcohort vs the full cohort (185 146 [33.8%] vs 774 363 [41.5%]).

CRC Case and Control Groups

From the study cohort, 79 095 CRC cases (1.7% of total) and 316 380 individuals in the control group were identified. In both groups, the median (IQR) age was 71 (63-78) at the time of diagnosis, and 233 820 (59.1%) were men. Cancer stage information was available for 57 675 patients (72.9%) in the CRC group through TCR; 13 305 (16.8%), 16 365 (20.7%), and 12 100 (15.3%) were diagnosed at stage II, III, and IV, respectively. Prevalence of gastrointestinal diseases, gastrointestinal medications, and health care facility visits were higher in the CRC group. There were 18 349 individuals in the CRC group and 73 396 individuals in the control group in the subcohort aged 40 to 59 years; median (IQR) age at time of diagnosis was 60 (55-63) years, and 56 210 (61.3%) were men. The CRC group of the subcohort had similar proportions of patients with hypertension and diabetes but a slightly higher proportion with mild liver disease (Table 2).

Table 2. Baseline Characteristics of CRC Case and Control Groups, 1 Year Prior to Case-Control Index Date.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full study cohort | Subcohort of individuals aged 40-59 y | |||

| CRC case group (n = 79 095) | Control group (n = 316 380) | CRC case group (n = 18 349) | Control group (n = 73 396) | |

| Long-term current aspirin use | 3294 (4.2) | 12 747 (4.0) | 689 (3.8) | 2786 (3.8) |

| Episodic aspirin use | 30 224 (38.2) | 113 154 (35.7) | 6192 (33.7) | 27 142 (37.0) |

| Nonuse | 45 577 (57.6) | 190 479 (60.2) | 11 468 (62.5) | 43 468 (59.2) |

| Men | 46 764 (59.1) | 187 056 (59.1) | 11 242 (61.3) | 44 968 (61.3) |

| Age | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 71 (10.6) | 71 (10.6) | 59 (5.7) | 59 (5.7) |

| Median (IQR) | 71 (63-78) | 71 (63-78) | 60 (55-63) | 60 (55-63) |

| CRC stage | ||||

| Unknowna | 6447 (8.2) | NA | 1678 (9.1) | NA |

| 0 | 5964 (7.5) | NA | 2054 (11.2) | NA |

| I | 9941 (12.6) | NA | 2789 (15.2) | NA |

| II | 13 305 (16.8) | NA | 2648 (14.4) | NA |

| III | 16 365 (20.7) | NA | 3917 (21.3) | NA |

| IV | 12 100 (15.3) | NA | 2483 (13.5) | NA |

| Missingb | 14 973 (18.9) | NA | 2780 (15.2) | NA |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Congestive heart failure | 4866 (6.2) | 13 640 (4.3) | 634 (3.5) | 1561 (2.1) |

| Hypertension | 37 663 (47.6) | 136 350 (43.1) | 7420 (40.4) | 25 763 (35.1) |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 9270 (11.7) | 32 863 (10.4) | 1191 (6.5) | 4009 (5.5) |

| Diabetes | 18 811 (23.8) | 59 606 (18.8) | 4326 (23.6) | 13 237 (18.0) |

| Kidney failure | 3839 (4.9) | 10 075 (3.2) | 694 (3.8) | 1691 (2.3) |

| Mild liver disease | 6586 (8.3) | 18 878 (6.0) | 1867 (10.2) | 5340 (7.3) |

| Moderate or severe liver disease | 210 (0.3) | 334 (0.1) | 56 (0.3) | 73 (0.1) |

| Risk factors | ||||

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | 10 397 (13.1) | 8168 (2.6) | 1945 (10.6) | 1383 (1.9) |

| Peptic ulcer disease exclude bleeding | 10 941 (13.8) | 23 518 (7.4) | 1970 (10.7) | 4291 (5.8) |

| Familial adenomatous polyposis | 3314 (4.2) | 1632 (0.5) | 897 (4.9) | 402 (0.5) |

| Ulcerative colitis | 61 (0.1) | 127 (0.0) | 15 (0.1) | 30 (0.0) |

| Crohn disease | 571 (0.7) | 583 (0.2) | 91 (0.5) | 109 (0.1) |

| Concomitant medications | ||||

| NSAID | 49 174 (62.2) | 187 996 (59.4) | 11 800 (64.3) | 45 180 (61.6) |

| Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor | 7361 (9.3) | 29 788 (9.4) | 901 (4.9) | 3413 (4.7) |

| Diuretics | 4065 (5.1) | 13 933 (4.4) | 584 (3.2) | 1826 (2.5) |

| β blocker | 20 863 (26.4) | 74 078 (23.4) | 4702 (25.6) | 16 312 (22.2) |

| Calcium channel blocker | 31 287 (39.6) | 108 790 (34.4) | 5813 (31.7) | 19 359 (26.4) |

| ACEI | 10 141 (12.8) | 34 795 (11.0) | 1840 (10.0) | 6086 (8.3) |

| ARB | 19 903 (25.2) | 70 639 (22.3) | 4181 (22.8) | 14 207 (19.4) |

| Statin | 13 316 (16.8) | 49 942 (15.8) | 3426 (18.7) | 12 222 (16.7) |

| Insulin | 7297 (9.2) | 12 583 (4.0) | 1271 (6.9) | 2491 (3.4) |

| Metformin | 12 648 (16.0) | 40 732 (12.9) | 3115 (17.0) | 9719 (13.2) |

| Sulfonylurea | 12 121 (15.3) | 38 781 (12.3) | 2817 (15.4) | 8560 (11.7) |

| Thiazolindinedione | 2268 (2.9) | 7690 (2.4) | 617 (3.4) | 2078 (2.8) |

| DPP-4 inhibitor | 3385 (4.3) | 10 255 (3.2) | 951 (5.2) | 2766 (3.8) |

| GLP-1 analogue | 11 (0.0) | 27 (0.0) | 9 (0.0) | 18 (0.0) |

| PPI, oral | 14 112 (17.8) | 20 178 (6.4) | 2562 (14.0) | 4303 (5.9) |

| H2 blocker, oral | 28 111 (35.5) | 77 790 (24.6) | 5985 (32.6) | 17 193 (23.4) |

| Anticholinergic agents | 58 468 (73.9) | 153 493 (48.5) | 12 427 (67.7) | 33 187 (45.2) |

| Outpatient visits | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 23 (17.9) | 19 (17.7) | 19 (15.6) | 16 (15.4) |

| Median (IQR) | 18 (10-30) | 15 (7-26) | 15 (8-25) | 12 (5-21) |

| Hospitalization episodes | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 0.52 (0.99) | 0.24 (0.74) | 0.34 (0.83) | 0.15 (0.6) |

| Median (IQR) | 0 (0-1) | 0 (0-0) | 0 (0-0) | 0 (0-0) |

| Total admission days | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 21 (41.3) | 18 (63.2) | 16 (26.9) | 15 (50.1) |

| Median (IQR) | 12 (5-24) | 7 (4-15) | 8 (4-18) | 5 (3-11) |

| Emergency department visits | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 0.7 (1.42) | 0.37 (1.08) | 0.5 (1.19) | 0.26 (0.85) |

| Median (IQR) | 0 (0-1) | 0 (0-0) | 0 (0-1) | 0 (0-0) |

Abbreviations: ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; CRC, colorectal cancer; DPP-4, dipeptidyl peptidase-4; GLP-1, glucagon-like peptide-1; H2 blocker, histamine 2 receptor; IQR, interquartile range; NA, not applicable; NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; PPI, proton pump inhibitor.

Unknown, staging variable coded as 999, 888, 998, BBB, X, or XXX are considered unknown stage in the long-form database.

Missing, incident cancer cases not reported to long-form database in the cancer registry and thus available information on staging provided.

Aspirin Use and CRC Risk

More than half of individuals in the case group (45 577 [57.6%]) and control group (190 479 [60.2%]) did not use low-dose aspirin before the index date; a small proportion of the case group used low-dose aspirin regularly (3294 [4.2%]) (Table 3). More than one-third of individuals in the case group (30 224 [38.2%]) and control group (113 154 [35.7%]) were exposed to low-dose aspirin episodically. Comparing long-term current low-dose aspirin use vs nonuse for CRC risk, the crude OR was 1.08 (95% CI, 1.04-1.13), and the adjusted OR was 0.89 (95% CI, 0.85-0.93) after adjusting for clinical attributes and health care utilization. A similar magnitude of association with lower CRC risk was observed among the episodic low-dose aspirin use group (adjusted OR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.86-0.89). Adjusted ORs were within the range of 0.87 to 0.92 with at least 1 to 10 years of low-dose aspirin use. Comparing those who discontinued low-dose aspirin use 1 year or longer before index date and those who had current long-term low-dose aspirin use, the adjusted OR was 0.97 (95% CI, 0.93-1.02) (Table 3). Among the CRC case and control groups in the subcohort of patients initiating low-dose aspirin at a younger age, long-term current low-dose aspirin use was associated with 31% lower CRC risk (adjusted OR, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.63-0.76), and episodic low-dose aspirin use was associated with 36% lower risk (adjusted OR, 0.64; 95% CI, 0.61-0.67). At least 1 year to 5 years of low-dose aspirin use showed similar levels of association with CRC risk (adjusted ORs ranged from 0.66 to 0.71), and a smaller strength of association was observed for those with at least 10 years of use (adjusted OR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.68-0.95). Similar to the full study cohort, discontinuation of low-dose aspirin 1 year or longer before index date was not associated with CRC risk compared with long-term current aspirin use (adjusted OR, 0.96; 95% CI, 0.87-1.10) (Table 3).

Table 3. Association Between Low Dose Aspirin Use and CRC .

| Characteristic | No. (%) | Odds ratio (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRC case group | Control group | Crude | Adjusteda | Adjustedb | |

| Full study cohort | |||||

| No. | 79 095 | 316 380 | NA | NA | NA |

| Main analysis | |||||

| Long-term current aspirin use | 3294 (4.2) | 12 747 (4.0) | 1.08 (1.04-1.13) | 0.93 (0.89-0.97) | 0.89 (0.85-0.93) |

| Episodic aspirin use | 30 224 (38.2) | 113 154 (35.7) | 1.12 (1.10-1.14) | 0.91 (0.90-0.93) | 0.88 (0.86-0.89) |

| Nonuse | 45 577 (57.6) | 190 479 (60.2) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Duration, y | |||||

| ≥1 | 4394 (5.6) | 17 120 (5.4) | 1.08 (1.04-1.11) | 0.93 (0.89-0.96) | 0.87 (0.84-0.90) |

| ≥2 | 3797 (4.8) | 14 714 (4.7) | 1.08 (1.04-1.12) | 0.93 (0.89-0.97) | 0.89 (0.85-0.93) |

| ≥5 | 2352 (3.0) | 9156 (2.9) | 1.08 (1.03-1.13) | 0.93 (0.88-0.97) | 0.89 (0.85-0.94) |

| ≥10 | 715 (0.9) | 2659 (0.8) | 1.13 (1.04-1.23) | 0.95 (0.87-1.04) | 0.92 (0.84-1.01) |

| 0 | 45 577 (57.6) | 190 479 (60.2) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Discontinuation period, yc | |||||

| ≥1 | 16 965 (21.4) | 67 238 (21.3) | 0.98 (0.94-1.02) | 0.91 (0.87-0.95) | 0.97 (0.93-1.02) |

| ≥2 | 13 544 (17.1) | 54 307 (17.2) | 0.96 (0.92-1.01) | 0.91 (0.87-0.95) | 0.97 (0.93-1.02) |

| ≥3 | 10 844 (13.7) | 43 890 (13.9) | 0.96 (0.91-1.00) | 0.90 (0.86-0.94) | 0.97 (0.93-1.02) |

| Long-term current aspirin use | 3294 (4.2) | 12 747 (4.0) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Subcohort of participants aged 40-59 y | |||||

| No. | 18 349 | 73 396 | NA | NA | NA |

| Main analysis | |||||

| Long-term current aspirin use | 689 (3.8) | 2786 (3.8) | 0.93 (0.86-1.02) | 0.72 (0.66-0.79) | 0.69 (0.63-0.76) |

| Episodic aspirin use | 6192 (33.7) | 27 142 (37.0) | 0.86 (0.83-0.89) | 0.66 (0.64-0.69) | 0.64 (0.61-0.67) |

| Nonuse | 11 468 (62.5) | 43 468 (59.2) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Duration, y | |||||

| ≥1 | 860 (4.7) | 3578 (4.9) | 0.91 (0.84-0.98) | 0.70 (0.64-0.76) | 0.66 (0.60-0.72) |

| ≥2 | 778 (4.2) | 3147 (4.3) | 0.93 (0.86-1.01) | 0.72 (0.66-0.79) | 0.69 (0.63-0.76) |

| ≥5 | 536 (2.9) | 2135 (2.9) | 0.95 (0.86-1.05) | 0.73 (0.66-0.81) | 0.71 (0.64-0.78) |

| ≥10 | 216 (1.2) | 766 (1.0) | 1.07 (0.92-1.25) | 0.83 (0.71-0.98) | 0.81 (0.68-0.95) |

| 0 | 11 468 (62.5) | 43 468 (59.2) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Discontinuation period, yc | |||||

| ≥1 | 4074 (22.2) | 18 217 (24.8) | 0.91 (0.83-0.99) | 0.91 (0.83-0.998) | 0.96 (0.87-1.05) |

| ≥2 | 3562 (19.4) | 15 731 (21.4) | 0.92 (0.84-1.00) | 0.93 (0.85-1.02) | 0.98 (0.89-1.08) |

| ≥3 | 3105 (16.9) | 13 555 (18.5) | 0.93 (0.85-1.02) | 0.95 (0.86-1.05) | 1.01 (0.91-1.11) |

| Long-term current aspirin use | 689 (3.8) | 2786 (3.8) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

Abbreviations: CRC, colorectal cancer; NA, not applicable.

Adjusted for cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors, nonsteroid anti-inflammatory drugs, proton pump inhibitor, histamine 2 blocker, antidiabetic agents, statin, antihypertensive agents, gastrointestinal cholinergic antagonist, gastrointestinal bleeding, peptic ulcer, ulcerative colitis, Crohn disease, colonoscopy, and familial adenomatous polyposis.

Adjusted for cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors, nonsteroid anti-inflammatory drugs, proton pump inhibitor, histamine 2 blocker, antidiabetic agents, statin, antihypertensive agents, gastrointestinal cholinergic antagonist, gastrointestinal bleeding, peptic ulcer, ulcerative colitis, Crohn disease, colonoscopy, familial adenomatous polyposis, high-dose aspirin, intravenous aspirin, and health care utilization in the previous year.

Discontinuation period was measured for individuals in episodic use group who had stopped using aspirin at least 1 year before index date.

Aspirin Use and Different CRC Stages

For all study participants, low-dose aspirin use was associated with lower risk of stage II, III, and IV CRC, and no association was observed for stage 0 or I CRC (Table 4). Among patients who initiated aspirin use before age 60 years, a range of 25% to 40% lower CRC risk was observed across all stages of CRC in both long-term current and episodic low-dose aspirin use groups (Table 4).

Table 4. Association Between Low Dose Aspirin Use and Staging of CRC.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | Odds ratio (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRC case group | Control group | Crude | Adjusteda | Adjustedb | |

| Full study cohort | |||||

| Stage 0 | 5964 | 23 856 | NA | NA | NA |

| Long-term current aspirin use | 287 (4.8) | 1034 (4.3) | 1.24 (1.08-1.42) | 0.97 (0.83-1.12) | 0.94 (0.80-1.09) |

| Episodic aspirin use | 2369 (39.7) | 8077 (33.9) | 1.31 (1.24-1.39) | 0.98 (0.91-1.05) | 0.97 (0.90-1.04) |

| Nonuse | 3308 (55.5) | 14 745 (61.8) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Stage I | 9941 | 39 764 | |||

| Long-term current aspirin use | 537 (5.4) | 1698 (4.3) | 1.39 (1.26-1.54) | 1.05 (0.94-1.17) | 1 (0.90-1.12) |

| Episodic aspirin use | 3918 (39.4) | 13 951 (35.1) | 1.24 (1.18-1.30) | 0.94 (0.89-0.99) | 0.91 (0.86-0.96) |

| Nonuse | 5486 (55.2) | 24 115 (60.6) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Stage II | 13 305 | 53 220 | |||

| Long-term current aspirin use | 544 (4.1) | 2304 (4.3) | 0.94 (0.86-1.04) | 0.86 (0.78-0.95) | 0.82 (0.74-0.92) |

| Episodic aspirin use | 4883 (36.7) | 19 406 (36.5) | 1.01 (0.97-1.05) | 0.85 (0.81-0.89) | 0.81 (0.78-0.85) |

| Nonuse | 7878 (59.2) | 31 510 (59.2) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Stage III | 16 365 | 65 460 | |||

| Long-term current aspirin use | 674 (4.1) | 2736 (4.2) | 1 (0.91-1.09) | 0.91 (0.83-1.00) | 0.88 (0.80-0.97) |

| Episodic aspirin use | 5986 (36.6) | 23 476 (35.9) | 1.03 (0.99-1.07) | 0.88 (0.85-0.92) | 0.86 (0.82-0.89) |

| Nonuse | 9705 (59.3) | 39 248 (60.0) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Stage IV | 12 100 | 48 400 | |||

| Long-term current aspirin use | 443 (3.7) | 2091 (4.3) | 0.83 (0.74-0.92) | 0.75 (0.67-0.84) | 0.72 (0.64-0.81) |

| Episodic aspirin use | 4310 (35.6) | 17 541 (36.2) | 0.96 (0.92-1.00) | 0.83 (0.79-0.87) | 0.80 (0.76-0.84) |

| Nonuse | 7347 (60.7) | 28 768 (59.4) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Subcohort with individuals aged 40-59 y | |||||

| Stage 0 | 2054 | 8216 | |||

| Long-term current aspirin use | 80 (3.9) | 357 (4.3) | 0.86 (0.67-1.11) | 0.63 (0.48-0.83) | 0.60 (0.46-0.79) |

| Episodic aspirin use | 719 (35.0) | 3031 (36.9) | 0.91 (0.82-1.01) | 0.64 (0.57-0.73) | 0.65 (0.57-0.73) |

| Nonuse | 1255 (61.1) | 4828 (58.8) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Stage I | 2789 | 11 156 | |||

| Long-term current aspirin use | 129 (4.6) | 448 (4.0) | 1.14 (0.93-1.40) | 0.80 (0.64-1.00) | 0.75 (0.60-0.93) |

| Episodic aspirin use | 1008 (36.1) | 4176 (37.4) | 0.95 (0.87-1.04) | 0.67 (0.60-0.74) | 0.64 (0.58-0.71) |

| Nonuse | 1652 (59.2) | 6532 (58.6) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Stage II | 2648 | 10 592 | |||

| Long-term current aspirin use | 94 (3.5) | 419 (4.0) | 0.83 (0.66-1.04) | 0.67 (0.53-0.86) | 0.63 (0.49-0.81) |

| Episodic aspirin use | 845 (31.9) | 3855 (36.4) | 0.81 (0.74-0.89) | 0.66 (0.60-0.74) | 0.63 (0.56-0.70) |

| Nonuse | 1709 (64.5) | 6318 (59.6) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Stage III | 3917 | 15 668 | |||

| Long-term current aspirin use | 140 (3.6) | 605 (3.9) | 0.83 (0.68-1.00) | 0.69 (0.56-0.84) | 0.7 (0.57-0.86) |

| Episodic aspirin use | 1213 (31.0) | 5837 (37.3) | 0.74 (0.69-0.80) | 0.61 (0.56-0.67) | 0.6 (0.55-0.65) |

| Nonuse | 2564 (65.5) | 9226 (58.9) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Stage IV | 2483 | 9932 | |||

| Long-term current aspirin use | 78 (3.1) | 363 (3.7) | 0.78 (0.61-1.00) | 0.63 (0.48-0.83) | 0.63 (0.48-0.84) |

| Episodic aspirin use | 795 (32.0) | 3696 (37.2) | 0.78 (0.71-0.86) | 0.65 (0.58-0.73) | 0.65 (0.58-0.72) |

| Nonuse | 1610 (64.8) | 5873 (59.1) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

Abbreviations: CRC, colorectal cancer; NA, not applicable.

Adjusted for cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors, nonsteroid anti-inflammatory drugs, proton pump inhibitor, histamine 2 blocker, antidiabetic agents, statin, antihypertensive agents, gastrointestinal cholinergic antagonist, gastrointestinal bleeding, peptic ulcer, ulcerative colitis, Crohn disease, colonoscopy, and familial adenomatous polyposis.

Adjusted for cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors, nonsteroid anti-inflammatory drugs, proton pump inhibitor, histamine 2 blocker, antidiabetic agents, statin, antihypertensive agents, gastrointestinal cholinergic antagonist, gastrointestinal bleeding, peptic ulcer, ulcerative colitis, Crohn disease, colonoscopy, familial adenomatous polyposis, high-dose aspirin, intravenous aspirin, and health care utilization in the previous year.

Sensitivity Analysis

Excluding those who were exposed to NSAIDs or COX-2 inhibitors 3 years prior to index date resulted in 10 124 individuals in the CRC case group and 40 496 individuals in the control group. A similar association between long-term current and episodic low-dose aspirin use and lower CRC risk as the full study cohort were observed (long-term current: adjusted OR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.78-1.02; episodic: adjusted OR, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.74-0.84). Lower CRC risk was associated with long-term current low-dose aspirin use in CRC stage II and higher, with the lowest risk observed for stage IV (adjusted OR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.52-1.00). Strengths of association between episodic low-dose aspirin use and CRC risk were similar to what was observed in the main analysis (eTable in the Supplement).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the largest study to date, with 79 095 individuals with CRC, to evaluate the association between low-dose aspirin use and CRC risk at population level. Long-term current and episodic low-dose aspirin use was associated with 11% and 12% lower CRC risk, respectively. Among patients initiating low-dose aspirin at the age of 40 to 59 years, long-term current and episodic low-dose aspirin use were associated with a 31% and 36% lower CRC risk, respectively. For different CRC stages, long-term current and episodic low-dose aspirin use were associated with lower risks of CRC among those who initiated low-dose aspirin between age 40 to 59 years.

Aspirin use and CRC has been evaluated in randomized clinical trials with extended follow-up of more than 10 years. Among women aged 45 years or older who were randomized to 100 mg aspirin every other day, a 20% CRC risk reduction after 18 years was observed.9,11 Such risk reduction effect was not observed in men, who were randomized to 325 mg every other day for 5 years2; however, decreasing CRC risk was implied in the 5-year and 12-year follow up.2,5

On the other hand, aspirin use and lower CRC risk has been shown consistently in observational studies. Reported strengths of association stratified by aspirin recency, duration, and dose strengths are not consistent. In the Nurses’ Health Study (NHS), registered nurses aged 30 to 55 years who took 2 tablets of 325 mg aspirin or equivalent doses per week experienced a greater than 30% lower CRC risk after 20 years of follow-up3,8; smaller relative risks were observed in the 8-year follow up in NHS and the 10-year follow up from Cancer Prevention Study II Nutrition Cohort in an older population.10 A 32-year follow-up report incorporating data from the Health Professionals Follow-up Study and NHS indicated that regular aspirin use was associated with approximately 20% lower CRC risk.16 The studies demonstrated that the magnitude of the association between aspirin use and lower CRC risk increased with longer duration and larger doses.3,8,16 However, our findings did not support a correlation between longer low-dose aspirin use and lower CRC risk (Table 3).

A nested case-control study using UK Clinical Practice Research Data Link did not show an association between CRC risk in individuals who currently or formerly used aspirin when compared with those who did not; however, 40% lower CRC risk was observed in the 300-mg tablet group.7 Recent nested case-control studies using The Health Improvement Network (THIN) from the UK and electronic health records from Spain demonstrated a 20% or greater lower CRC risk associated with low-dose aspirin use.12,22 In the THIN study, the magnitude of lower CRC risk appeared to be more prominent among recent and past users than among current users, and the risk of lower stage CRC (ie, Dukes A) was not found to be associated with aspirin, which are similar to our findings.12 The observation that episodic aspirin use was associated with the same level of lower CRC risk as that for long-term aspirin use was intriguing, and it could be due to the stringent operational definition of long-term current use in this study, resulting in substantial number of individuals with a level of aspirin use that would be associated with lower CRC risk included in the episodic use group. A meta-analysis demonstrated a 27% lower CRC risk from 45 observational studies and a 14% lower risk from 11 nested case-control studies; low-dose aspirin (ie, 75 to 100 mg per day) was associated with a 10% lower CRC risk, which is similar to our finding.23 Whether discontinuation of low-dose aspirin would immediately obviate any association with CRC incidence has not been adequately addressed in the literature, and our findings on the length of low-dose aspirin discontinuation before CRC were inconclusive.

Capturing aspirin use in health insurance claims is a unique strength of the study. In 2 cohort studies using sampled NHI data from Taiwan, low-dose aspirin use was found to be associated with approximately 50% lower CRC risk among the general population13 and among a population with diabetes.14 A nested case-control study that used sampled NHI data demonstrated similar findings (adjusted OR, 0.94) for lower CRC risk as reported in our study.15 The major strengths of our study compared with previous studies from Taiwan included the much larger study size, derived from the full population; longer follow-up; use of TCR for cancer ascertainment; CRC stage–specific analysis; and a range of sensitivity analyses to evaluate the robustness of the findings. We identified all eligible individuals with low-dose aspirin use from 2002 through 2010 in Taiwan and all CRC cases among them through 2015. Optimal methods were used to identify appropriate comparators. Working with the full NHI data necessitated a sampling scheme to identify individuals who were unexposed rather than individually matching members of the unexposed group to individuals with aspirin use. The nested case-control analysis allowed for efficient evaluation of the role of recency and duration of prior aspirin use.

A biologic basis for decreased tumor formation with aspirin initiation at younger age has been proposed.24 Although a modest level of lower CRC risk was observed in our study cohort, we found that in the subcohort in which low-dose aspirin was initiated among patients at age 40 to 59 years, the magnitude of the association with lower CRC risk was larger. This would be consistent with the US Preventive Service Task Force recommendation of added benefit for CRC risk reduction in a younger population.25

Limitations

This study has limitations. Given that the NHI data are insurance claims, we were unable to ascertain smoking and alcohol consumption as well as body mass index of participants, all of which are potential confounders that have been evaluated in other studies.3,8,10,12,16,22 The CRC screening program in Taiwan only offers fecal occult blood tests for those aged 50 to 75 years, and the test results are not linked to NHI for research. Despite the high prevalence of low-dose aspirin use in Taiwan, adherence has been low, with only 4.2% of those who initiate low-dose aspirin having long-term use.

Conclusions

In this study, low-dose aspirin use was associated with an 11% lower CRC risk in an East Asian population, and this association was larger when low-dose aspirin use started before age 60 years. At least 3 years of low-dose aspirin use was associated with a 30% lower CRC risk.

eTable. Sensitivity Analysis in Study Cohort

Reference

- 1.Onyoh EF, Hsu WF, Chang LC, Lee YC, Wu MS, Chiu HM. The rise of colorectal cancer in Asia: epidemiology, screening, and management. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2019;21(8):36. doi: 10.1007/s11894-019-0703-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gann PH, Manson JE, Glynn RJ, Buring JE, Hennekens CH. Low-dose aspirin and incidence of colorectal tumors in a randomized trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85(15):1220-1224. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.15.1220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Giovannucci E, Egan KM, Hunter DJ, et al. Aspirin and the risk of colorectal cancer in women. N Engl J Med. 1995;333(10):609-614. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199509073331001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burn J, Chapman PD, Bishop DT, Mathers J. Diet and cancer prevention: the Concerted Action Polyp Prevention (CAPP) studies. Proc Nutr Soc. 1998;57(2):183-186. doi: 10.1079/PNS19980030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stürmer T, Glynn RJ, Lee IM, Manson JE, Buring JE, Hennekens CH. Aspirin use and colorectal cancer: post-trial follow-up data from the Physicians’ Health Study. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128(9):713-720. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-128-9-199805010-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.García Rodríguez LA, Huerta-Alvarez C. Reduced incidence of colorectal adenoma among long-term users of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs: a pooled analysis of published studies and a new population-based study. Epidemiology. 2000;11(4):376-381. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200007000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.García-Rodríguez LA, Huerta-Alvarez C. Reduced risk of colorectal cancer among long-term users of aspirin and nonaspirin nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. Epidemiology. 2001;12(1):88-93. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200101000-00015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chan AT, Giovannucci EL, Meyerhardt JA, Schernhammer ES, Curhan GC, Fuchs CS. Long-term use of aspirin and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and risk of colorectal cancer. JAMA. 2005;294(8):914-923. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.8.914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cook NR, Lee IM, Gaziano JM, et al. Low-dose aspirin in the primary prevention of cancer: the Women’s Health Study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;294(1):47-55. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.1.47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jacobs EJ, Thun MJ, Bain EB, Rodriguez C, Henley SJ, Calle EE. A large cohort study of long-term daily use of adult-strength aspirin and cancer incidence. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99(8):608-615. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djk132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cook NR, Lee IM, Zhang SM, Moorthy MV, Buring JE. Alternate-day, low-dose aspirin and cancer risk: long-term observational follow-up of a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159(2):77-85. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-159-2-201307160-00002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.García Rodríguez LA, Soriano-Gabarró M, Bromley S, Lanas A, Cea Soriano L. New use of low-dose aspirin and risk of colorectal cancer by stage at diagnosis: a nested case-control study in UK general practice. BMC Cancer. 2017;17(1):637. doi: 10.1186/s12885-017-3594-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang WK, Chiou MJ, Yu KH, et al. The association between low-dose aspirin use and the incidence of colorectal cancer: a nationwide cohort study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;38(4):432-439. doi: 10.1111/apt.12388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin CC, Lai MS, Shau WY. Can aspirin reduce the risk of colorectal cancer in people with diabetes? a population-based cohort study. Diabet Med. 2015;32(3):324-331. doi: 10.1111/dme.12596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuo CN, Pan JJ, Huang YW, Tsai HJ, Chang WC. Association between nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and colorectal cancer: a population-based case-control study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2018;27(7):737-745. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-17-0876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cao Y, Nishihara R, Wu K, et al. Population-wide impact of long-term use of aspirin and the risk for cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2(6):762-769. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.6396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hsiao F-Y, Yang C-L, Huang Y-T, Huang W-F. Using Taiwan's National Health Insurance Research Databases for pharmacoepidemiology research. Journal of Food and Drug Analysis. 2007;15(2):99-108. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lin L-Y, Warren-Gash C, Smeeth L, Chen P-C. Data resource profile: the National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD). Epidemiol Health. 2018;40(0):e2018062-e2018060. doi: 10.4178/epih.e2018062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chiang CJ, You SL, Chen CJ, Yang YW, Lo WC, Lai MS. Quality assessment and improvement of nationwide cancer registration system in Taiwan: a review. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2015;45(3):291-296. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyu211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chiang C-J. National Cancer Registry Database in Taiwan. Published May 26, 2017. Accessed September 14, 202. http://hcrdc.tmu.edu.tw/uploads/bulletin_file/file/5927dbb94f4d127fc9003d64/Introduction_and_Application_of_Taiwan_Cancer_Registry_Database_20170526.pdf

- 21.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP; STROBE Initiative . The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Epidemiology. 2007;18(6):800-804. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181577654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rodríguez-Miguel A, García-Rodríguez LA, Gil M, Montoya H, Rodríguez-Martín S, de Abajo FJ. Clopidogrel and low-dose aspirin, alone or together, reduce risk of colorectal cancer. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17(10):2024-2033.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bosetti C, Santucci C, Gallus S, Martinetti M, La Vecchia C. Aspirin and the risk of colorectal and other digestive tract cancers: an updated meta-analysis through 2019. Ann Oncol. 2020;31(5):558-568. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chan AT, McNeil J. Aspirin and cancer prevention in the elderly: where do we go from here? Gastroenterology. 2019;156(3):534-538. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.11.063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.US Preventive Services Task Force . Aspirin use to prevent cardiovascular disease and colorectal cancer: preventive medication. Published April 11, 2016. Accessed July 15, 2020. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/aspirin-to-prevent-cardiovascular-disease-and-cancer

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable. Sensitivity Analysis in Study Cohort