Abstract

Background

Cardiovascular outcomes in clinical trials with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) patients have shown that glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist can have a beneficial effect on the kidney. This trial aimed to assess the effects of exenatide on renal outcomes in patients with T2DM and diabetic kidney disease (DKD).

Methods

We performed a randomized parallel study encompassing 4 general hospitals. T2DM patients with an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) ≥30 mL/min/1.73 m<sup>2</sup> and macroalbuminuria, defined as 24-h urinary albumin excretion rate (UAER) >0.3 g/24 h were randomized 1:1 to receive exenatide twice daily plus insulin glargine (intervention group) or insulin lispro plus glargine (control group) for 24 weeks. The primary outcome was the UAER percentage change from the baseline after 24 weeks of intervention. The rates of hypoglycemia, adverse events (AEs), and change in eGFR during the follow-up were measured as safety outcomes.

Results

Between March 2016 and April 2019, 92 patients were randomized and took at least 1 dose of the study drug. The mean age of the participants was 56 years. At baseline, the median UAER was 1,512.0 mg/24 h and mean eGFR was 70.4 mL/min/1.73 m<sup>2</sup>. After 24 weeks of treatment, the UAER percentage change was significantly lower in the intervention group than in the control group (p = 0.0255). Moreover, the body weight declined by 1.3 kg in the intervention group (the difference between the 2 groups was 2.7 kg, p = 0.0001). Compared to the control group, a lower frequency of hypoglycemia and more gastrointestinal AEs were observed in the intervention group.

Conclusion

Exenatide plus insulin glargine treatment for 24 weeks resulted in a reduction of albuminuria in T2DM patients with DKD.

Keywords: Diabetic kidney disease, Albuminuria, Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists, Exenatide, Type 2 diabetes

Introduction

Diabetic kidney disease (DKD) is a common microvascular complication in diabetic patients. About 40% of these patients will develop DKD [1]. Since 2011, the percentage of hospitalized patients with CKD related to diabetes mellitus exceeded that of patients with CKD related to glomerulonephritis in China [2]. As the leading cause of ESRD, DKD can shorten life span by 16 years in patients with early kidney damage [3]. Therefore, the initiation of therapy with a hypoglycemic agent, which can also protect renal function, is of great importance.

Prospective studies have shown that proteinuria is an independent predictor of renal insufficiency in type 2 diabetic patients [4, 5]. Compared to patients with a baseline urinary albumin-to-Cr ratio (UACR) ≤1.0 g/g and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) >45 mL/min/1.73 m2, the incidence rate ratio of ESRD or cardiovascular (CV) death events was 12.87 in patients with an initial UACR >2.0 g/g and eGFR ≤30 mL/min/1.73 m2 after a mean follow-up of 2.8 years [6]. As a surrogate end point of DKD progression, the regression of albuminuria can reduce the incidence of ESRD irrespective of the therapeutic regimen [7]. Therefore, albuminuria is a valid substitute for ESRD in a short-term intervention.

Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RAs) have emerged as a new class of antihyperglycemic agent that can also lead to weight loss [8]. GLP-1RAs can be used to control the blood glucose level, with a low incident of hypoglycemia, by stimulating glucose-dependent insulin secretion [9]. The meta-analysis of several CV outcome trials showed that GLP-1RAs might have a beneficial effect on kidney outcomes [10]. As the chemical structures or pharmacokinetics vary in each GLP-1RA, whether exenatide twice daily (a short-acting exendin-4 structure) has a renal protective function remains inconclusive. Data from animal experiments have suggested that exendin-4 notably decreases 24-h urinary protein levels in mice within an 8-week treatment period [11]. Furthermore, a previous pilot study revealed that after 16 weeks of therapy with exenatide application, 24-h urinary protein excretion decreased in patients with type 2 diabetes and microalbuminuria compared with patients undergoing glimepiride treatment [12]. A systematic review and meta-analysis indicated that a combination of GLP-1RA and insulin was as effective as insulin alone in lowering the hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) level, as well as significant weight loss, a lower risk of hypoglycemia, and a use of less insulin dose [13]. However, the relative effects of exenatide plus insulin on renal function in patients with macroalbuminuria remain uncertain.

This study evaluated the effects of exenatide plus insulin glargine on DKD progression (the primary outcome) in type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) patients by using percentage change in the urinary albumin excretion rate (UAER). The safety and tolerability of exenatide plus insulin glargine were also assessed during the 24-week follow-up period.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Participants

A randomized, open-label, parallel study was conducted at 4 general hospitals in China, involving T2DM patients with DKD. Participants ≥18 years of age with an eGFR ≥30 mL/min/1.73 m2 and macroalbuminuria (UAER >0.3 g/24 h) were randomized 1:1 to receive exenatide twice daily plus insulin glargine or insulin lispro plus glargine and followed up for 24 weeks (see online suppl. Table 1; for all online suppl. material, see www.karger.com/doi/10.1159/000510255). This study was approved by the institutional research ethics committee of Nanfang Hospital, Guangdong Second Traditional Chinese Medicine Hospital, Guangdong Provincial Hospital of Chinese Medicine, and Guangdong Second Provincial General Hospital. All individuals provided informed consent prior to their inclusion in the study. This trial was performed in compliance with the Helsinki Declaration and registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02690883).

Interventions

Before randomization, patients were subjected to the 3-day screening phase and the 2-week run-in phase. At the end of the screening phase, patients fulfilling all the eligibility criteria entered the 2-week run-in phase. During the 2 weeks of the run-in phase, basal insulin was titrated in every patient twice a week based on the results of the fasting self-monitored blood glucose levels. After the run-in period, patients were randomly assigned to 1 of the 2 groups to undergo antihyperglycemic therapies for a total duration of 24 weeks − exenatide plus insulin glargine (intervention group) and insulin lispro plus glargine (controlled group). The treatment of exenatide was initiated at 5 μg twice a day (b.i.d), titrated up to 10 μg b.i.d. after 4 weeks, and then maintained at 10 μg b.i.d. until the completion of the study. Insulin lispro was initially administered according to the insulin dose used in previous antihyperglycemic therapies and further titrated at 4-week intervals to match the target fasting plasma glucose (FPG) level. Starting from the run-in period, all blood glucose-lowering drugs except for exenatide or insulin were excluded. Whereas, the decision on other background therapy for hypertension, hyperlipidemia, or CV-related risk factors were taken based on the latest guidelines during the follow-up [14] (online suppl. Fig. 1)

Outcomes

The primary outcome of the study was the percentage change in the UAER from the baseline at 24 weeks. Secondary outcomes included the percentage change in the UACR from the baseline at 24 weeks, as well as changes in the UAER, UACR, HbA1c, FPG, weight, and blood pressure (BP) from their respective baseline levels. Safety outcomes included the progression of renal function, as defined by eGFR, rates of hypoglycemia, and adverse events (AEs). Blood and urine samples for determination of clinical chemistry, hematology, and urinalysis were taken at 12 and 24 weeks through in-person visits at each site. Telephone or web-based follow-up was scheduled every month to gather information on AEs including hypoglycemic events.

Sample Size

Statistical tests were performed at a significance level of α = 0.05 (2-sided). Based on the results of previous studies, the corresponding percentage change in the UAER would be 40% [7, 12] in the exenatide group and 20% [15] in the control group. The sample size per group was calculated to achieve 80% power with a standard deviation of 30% (hypothesis: superiority). Enrollment of at least 90 patients in total (45 per group) was needed to allow a 20% drop out rate.

Randomization

Based on randomized (1:1), open-label, parallel-group, controlled study design, a block randomization method was applied in this study. To prevent selection bias, we developed an allocation concealment mechanism, whereby the allocation sequence was maintained by a researcher who did not participate in the clinical work. The physician referred patients fulfilling the eligibility criteria to the research nurse. After obtaining informed consent, the research nurse assigned patients to the researcher, based on the allocation sequence to retrieve the result of randomization.

Statistical Methods

The full analysis set (FAS) included all randomized subjects who took at least 1 investigational product (IP) and had at least 1 non-missing baseline and 1 post-baseline efficacy data assessment. The FAS was the primary set for efficacy analysis in this study, and subjects were analyzed according to the allocated randomized group. The per protocol set (PPS) was a subset of the FAS that included patients who finished the final visit and excluded those subjects who had significant protocol deviations. The safety analysis included subjects who took at least 1 dose of IP. AEs including hypoglycemia were collected throughout the treatment period.

The primary end point was analyzed utilizing a mixed-model repeated measure (MMRM) on the FAS. The MMRM analysis contained terms for the treatment group, time from baseline, baseline measurements, and time of the treatment group interactions. Unstructured (UN) covariance was used for the analysis of repeated measures in all subjects. Within the framework of MMRM, point estimations ± standard errors were presented at each visit to measure the mean change within each treatment group as well as the differences and 2-sided 95% CI of the mean change between the treatment groups. A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. The sensitivity analysis for the primary end point was based on the FAS and utilized multiple imputations with 25 imputed data sets to account for missing data. In addition, a prespecified sensitivity analysis on PPS was performed. Secondary end points were analyzed using a similar MMRM analysis used for the primary end point. Data were analyzed with SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Recruitment and Follow-Up

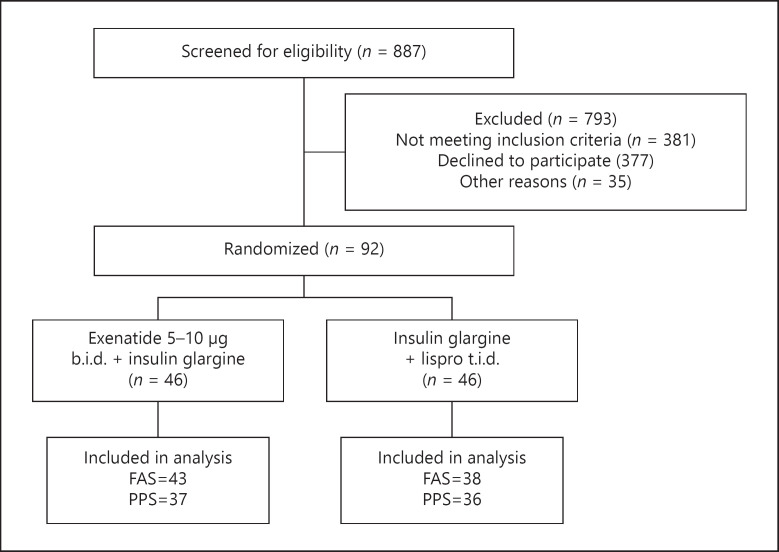

Between March 2016 and April 2019, 887 individuals were screened and 92 individuals were randomized and allocated to 2 groups (46 individuals per group). Eleven patients were excluded from the effective analysis due to missing follow-up data after randomization. Eight patients discontinued IP: premature intervention discontinued due to AE (N = 6), withdrawal of consent (N = 1), and lost to follow-up (N = 1). These 8 patients were included in the FAS analysis but not in the PPS analysis. Eighty-one (88.0%) patients (43 in the intervention group, 38 in the control group) in total were included for the FAS analysis and 73 (79.3%) (37 patients in the intervention group, 36 patients in the control group) patients were included in the PPS (shown in Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

A flowchart depicting the enrollment of participants in the trial. FAS, full analysis set; PPS, per protocol set.

Patient Characteristics

The baseline characteristics of the study participants were similar in the 2 groups (details are shown in Table 1). More than half of the patients were male (N = 64, 69.7%). At baseline, the mean (±SD) age of the participants was 56.0 ± 8.4 years and the average time from the diagnosis of diabetes to enrollment in this study was 11.2 ± 6.6 years. The mean BMI was 24.8 ± 3.5 kg/m2 and the mean HbA1c was 9.0 ± 1.4%. The median [IQR] UACR and UAER were 1,245.0 [667.1, 2,875.2] mg/g and 1,512.0 [782.5, 2,818.0] mg/24 h, respectively, while the mean eGFR was 70.4 ± 23.4 mL/min/1.73 m2

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of randomized participants

| Variablea | Control (n = 46) | Intervention (n = 46) | Total (n = 92) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 56.2 (8.0) | 55.9 (8.9) | 56.0 (8.4) |

| Male, n (%) | 29 (63.0) | 35 (76.1) | 64 (69.7) |

| Duration of diabetes, years | 11.4 (7.0) | 10.9 (6.2) | 11.2 (6.6) |

| HbA1c (%) | 9.0 (1.3) | 9.1 (1.4) | 9.0 (1.4) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 23.5 (3.1) | 26.1 (3.4) | 24.8 (3.5) |

| Systolic BP, mm Hg | 140.3 (14.6) | 139.1 (16.7) | 139.7 (15.6) |

| Diastolic BP, mm Hg | 79.1 (7.5) | 78.3 (8.3) | 78.7 (7.9) |

| Triglycerides, mmol/L | 1.8 (1.1) | 1.8 (0.9) | 1.8 (1.0) |

| Total cholesterol, mmol/L | 5.1 (1.4) | 5.1 (1.6) | 5.1 (1.5) |

| HDL, mmol/L | 1.2 (0.3) | 1.0 (0.4) | 1.1 (0.3) |

| LDL, mmol/L | 3.2 (1.2) | 3.0 (1.3) | 3.1 (1.2) |

| eGFR,b mL/min/1.73 m2 | 69.2 (24.6) | 71.5 (22.5) | 70.4 (23.4) |

| UACR, mg/g | 1,380.9 (601.8, 2,951.5) | 1,146.2 (709.4, 2,488.2) | 1,245.0 (667.1, 2,875.2) |

| UAER, mg/24 h | 1,438.0 (531.0, 2,852.0) | 1,721.0 (982.0, 2,816.0) | 1,512.0 (782.5, 2,818.0) |

| Current smoker, n (%) | 18 (39.1) | 23 (50.0) | 41 (44.6) |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 36 (78.4) | 39 (84.8) | 75 (81.5) |

| Hyperlipidemia, n (%) | 35 (76.1) | 35 (76.1) | 70 (76.1) |

| CV disease, n (%) | 13 (28.3) | 12 (26.1) | 25 (27.2) |

| Sulfonylurea, n (%) | 8 (17.4) | 6 (13.0) | 14 (15.2) |

| Metformin, n (%) | 17 (37.0) | 18 (39.1) | 35 (38.0) |

| AG inhibitors, n (%) | 11 (23.9) | 13 (28.3) | 24 (26.1) |

| Insulin, n (%) | 33 (71.7) | 36 (78.3) | 69 (75.0) |

| Diuretic, n (%) | 7 (15.2) | 6 (13.0) | 13 (14.1) |

| Calcium-channel blocker, n (%) | 28 (60.9) | 28 (60.9) | 56 (60.9) |

| ACEI/ARB | 40 (87.0) | 40 (87.0) | 80 (87.0) |

| Beta blocker, n (%) | 4 (8.7) | 9 (19.6) | 13 (14.1) |

| Any anti-hypertensive, n (%) | 41 (89.1) | 42 (91.3) | 83 (90.2) |

| Statin, n (%) | 39 (84.8) | 41 (89.1) | 80 (87.0) |

| Any lipid-lowering drug, n (%) | 40 (87.0) | 42 (91.3) | 82 (89.1) |

| Aspirin, n (%) | 10 (21.7) | 19 (41.3) | 29 (31.5) |

| Any anti-platelets, n (%) | 13 (28.3) | 24 (52.2) | 37 (40.2) |

CV, cardiovascular; HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c; BP, blood pressure; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; UACR, urinary albumin-to-Cr ratio; UAER, urinary albumin excretion rate; AG, aminoglycosides; ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ARB, angiotensin II, receptor blocker; CKD-EPI, Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration.

Numeric variables are presented as mean (SD) if normally distributed. Categorical variables are presented as frequency (%). UAER and UACR are presented as median [IQR].

eGFR is calculated with the CKD-EPI equation.

Before the run-in period, 35 (38.0%), 14 (15.2%), and 69 (75.0%) participants were using metformin, sulphonylurea, and insulin, respectively. A total of 75/70 randomized patients had hypertension/hyperlipidemia. The majority (N = 80, 87.0%) of these patients were using angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor blocker, and the majority of participants (N = 80, 87.0%) were prescribed statin. Twenty-five (27.2%) patients had a history of CV disease.

Primary Outcome

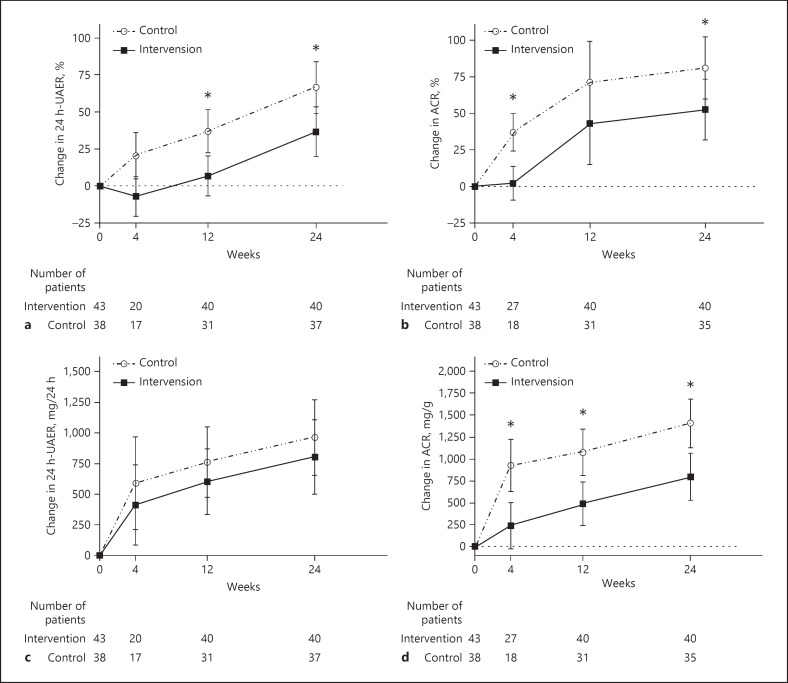

In the FAS analysis, the percentage change in the UAER was significantly lower in the intervention group (−29.71%; 95% CI: −55.27 to −4.15%; p = 0.0255) than in the control group (percentage change in UAER: intervention group = 36.69 ± 16.88% and control group = 66.40 ± 17.42%). A similar result was obtained in the PPS analysis (percentage change in the UAER: intervention group was 30.07 ± 18.03%, control group was 58.89 ± 18.03%, the mean difference was −28.81% with a 95% CI of −55.90 to −1.72% and p = 0.0407) (shown in Fig. 2a; Table 2). Using multiple imputations to account for the missing data, the mean difference between the intervention group and the control group was −16.11% with a 95% CI of −30.93 to −1.295% and p = 0.0363.

Fig. 2.

Mean changes from baseline in albuminuria patients according to the analysis of MMRM on FAS. Percentage change in the UAER (%) (a); percentage change in the ACR (%) (b); change in the UAER (mg/24 h) (c); change in the ACR (mg/g) (d). * for p < 0.05. I bar indicates standard error. MMRM, mixed-model repeated measure; FAS, full analysis set; UAER, urinary albumin excretion rate; ACR, albumin-to-Cr ratio.

Table 2.

Changes after 24 weeks of follow-up!

| Outcomes | FAS analysis |

PPS analysis |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| control | intervention | differencea (95% CI) | p value | control | intervention | differencea (95% CI) | p value | |

| Primary outcome | ||||||||

| UAER, % | 66.40±17.42 | 36.69±16.88 | −29.71 (−55.27, −4.15) | 0.0255 | 58.89±18.03 | 30.07±18.03 | −28.81 (−55.90, −1.72) | 0.0407 |

| Secondary outcomes | ||||||||

| UAER, mg/24 h | 963.79±307.95 | 804.12±305.01 | −159.60 (−696.24, 376.90) | 0.5614 | 970.82±274.51 | 651.97±283.26 | −318.85 (−846.99, 209.29) | 0.2407 |

| UACR, % | 80.93±21.13 | 52.53±20.80 | −28.40 (−56.88, −1.92) | 0.0395 | 70.56±15.40 | 34.82±15.47 | −35.75 (−62.12, −9.36) | 0.0100 |

| UACR, mg/g | 1405.93±276.87 | 798.12±269.05 | −607.80 (−1,112.38, −103.22) | 0.0209 | 1337.65±233.98 | 625.37±235.07 | −712.27 (−1,188.24, 236.30) | 0.0046 |

| HbA1c, % | −1.78±0.24 | −1.56±0.23 | 0.21 (−0.40, 0.82) | 0.4928 | −1.75±0.25 | −1.52±0.24 | 0.23 (−0.86, 0.40) | 0.4810 |

| FPG, μmol/L. | −0.06±0.59 | −1.05±0.55 | −0.99 (02.46, 0.48) | 0.1886 | −0.19±0.62 | −0.95±0.60 | −0.76 (−2.31, 0.79) | 0.3385 |

| Weight, kg | 1.30±0.66 | −1.38±0.63 | −2.68 (−3.97, −1.39) | 0.0001 | 0.74±0.63 | −1.76±0.62 | −2.51 (−4.04, −0.98) | 0.0019 |

| Systolic BP, mm Hg | −4.63±3.20 | −4.31±3.04 | 0.32 (−7.44, 8.08) | 0.9351 | −4.79±3.01 | −5.23±2.95 | −0.44 (−8.03, 7.15) | 0.9099 |

| Other outcomes | ||||||||

| eGFR, % | −11.74±3.40 | −5.91±3.23 | 5.83 (−2.68, 14.34) | 0.1832 | −11.64±3.30 | −2.74±3.22 | 8.90 (0.59, 17.21) | 0.0393 |

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73 m2 | −9.19±2.47 | −4.64±2.34 | 4.55 (−1.62, 10.72) | 0.1523 | −9.19±2.41 | −2.55±2.36 | 6.64 (0.52, 12.76) | 0.0369 |

FAS, full analysis set; PPS, per protocol set; CI, confidence interval; UAER, urinary albumin excretion rate; UACR, urinary albumin-to-Cr ratio; HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; BP, blood pressure; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate.

Absolute mean difference between groups. All values expressed in mean ± standard error.

Secondary Outcomes

The percentage change in the UACR (intervention group = 80.93 ± 21.13% and control group = 52.53 ± 20.80%) was equivalent to the level of the percentage change in the UAER, leading to an absolute mean difference of −28.40% (95% CI: −56.88 to −1.92%, p = 0.0395). Although there was no significant difference in the UAER change at 24 weeks between the 2 groups, the UACR change was greater in the intervention group than in the control group (change in UACR: intervention group = 1,405.93 ± 276.87 mg/g and control group = 798.12 ± 269.05 mg/g; the mean difference was −607.80 mg/g with a 95% CI: of −1,112.38 to −103.22 mg/g and p = 0.0209) (shown in Fig. 2b–d; Table 2).

Both treatments reduced HbA1c level, FPG, and systolic BP at 24 weeks, but there were no significant differences between the 2 groups. Among patients receiving exenatide plus insulin glargine, the mean body weight decreased by 1.38 ± 0.63 kg, while the mean body weight increased by 1.30 ± 0.66 kg in those patients receiving insulin lispro plus glargine, for a reduction of 2.68 kg (p = 0.0001) at 24 weeks (Table 2).

Tolerability and Safety

The eGFR increased by 0.98 ± 3.59 mL/min/1.73 m2 in the control group and by 1.05 ± 3.13 mL/min/1.73 m2 in the intervention group at the first visit (4 weeks), then decreased by 9.19 ± 2.47 mL/min/1.73 m2 in the control group and by 4.64 ± 2.34 mL/min/1.73 m2 in the intervention group during the entire follow-up, with an absolute difference of 4.55 mL/min/1.73 m2 (95% CI: −1.62 to 10.72; p = 0.1523).

In total, 22 AEs were recorded during the follow-up − 6 (13.04%) events in the control group, and 16 (34.78%) events in the intervention group (p = 0.015). AEs that led to discontinuation of the treatment occurred in 6 (13.04%) patients in the control group and in 5 (10.87%) patients in the intervention group (p = 0.726). Serious AEs were reported in 4 (8.70%) patients in control group and in 1 (2.17%) patient in intervention group (p = 0.361). Most AEs were gastrointestinal events and all 15 (32.61%) patients with gastrointestinal events were in the intervention group (p < 0.001). However, none of the gastrointestinal events had been considered as a severe adverse event. Twenty (43.5%) patients in the control group and 10 (21.7%) patients in the intervention group experienced hypoglycemia during the follow-up (p = 0.026) period. Furthermore, 2 patients in the control group experienced severe hypoglycemia and discontinued their participation in the study (online suppl. Table 2)

Discussion/Conclusion

In this randomized controlled trial, we found that exenatide plus insulin glargine treatment for 24 weeks can reduce the percentage change in the UAER in T2DM patients with macroalbuminuria compared with patients treated with insulin lispro plus glargine. This difference was robust in the sensitivity analysis. Moreover, we also found that exenatide plus insulin glargine can lead to additional weight loss and a lower occurrence of hypoglycemia than insulin lispro plus glargine. Although gastrointestinal events were common after initiating treatment with exenatide, most of these events were mild to moderate and none was severe.

During the median follow-up of 6.8 years, 9.6% of individuals with DKD experienced ESRD [16]. The kidney-related benefits of GLP-1RAs administration, compared with placebo treatments, have been reported in several exploratory analyses of CV outcome studies covering many T2DM patients [17, 18, 19]. A secondary analysis of the Liraglutide Effect and Action in Diabetes: Evaluation of Cardiovascular Outcome Results study showed that adding liraglutide, a GLP-1RA, to the routine care of patients can reduce the incidence of composite kidney end point [17]. Whereas, only a small number of randomized controlled trials have reported the effects of exenatide on renal outcomes [12, 20]. The results of Exenatide Study of Cardiovascular Event Lowering study (EXCEL) suggested that once-weekly exenatide application had no effect on renal outcomes, as the application neither changed the eGFR slope nor the ratio of microalbuminuria to macroalbuminuria [20]. Nonetheless, the primary outcome of EXCEL was CV disease, and most of the participants were in the early DKD stage at baseline. This bias might attenuate the renal effects of exenatide. Although different GLP-1RAs have different structures or mechanisms of action, the effects of short-acting exenatide on diabetic microvascular complications are not clear.

Our head-to-head design with positive control was superior to the placebo-controlled randomized trial as it could identify glucose-independent effects on real outcomes. A similarly designed 16-week study comparing the effects of exenatide and glimepiride showed a significant decrease in 24-h urinary albumin levels in T2DM patients with microalbuminuria [12]. Considering the poor prognostic outcomes and a lack of effective drugs in patients with DKD [6], we emphasized on those patients with macroalbuminuria and poor blood glucose control. In contrast to glimepiride or other oral antidiabetic drugs, insulin is commonly used in DKD patients as it does not require discontinuation with a corresponding decrease in eGFR [21]. Moreover, using an injection as the control group for exenatide could decrease this difference in medicine administration. To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the effects of exenatide plus insulin glargine on the UAER in patients with DKD.

Albuminuria is considered as a surrogate outcome of DKD progression and meta-analysis showed that the regression of albuminuria can reduce the incidence of ESRD irrespective of treatment bias [7]. However, most of the trials in this meta-analysis, involving T2DM patients with DKD, focused on anti-hypertensive drugs [22, 23, 24, 25, 26] and none included GLP-1RA. Various renal risk factors might impact the effect of exenatide on renal outcomes. A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials and observational studies assessed the benefits of weight loss showed that short-term interventions leading to nonsurgical weight loss in patients with CKD can also reduce proteinuria and BP [27]. Although differences between the intervention and control groups in systolic BP were not significant in our study, we should not ignore the impact of weight change or BP change on albuminuria. Thus, future studies with a larger cohort and a longer follow-up duration to monitor the incidence of ESRD may demonstrate the effects of exenatide on renal function.

Studies on hypoglycemic drugs should monitor the incidence of hypoglycemic episodes. The Action in Diabetes and Vascular Disease: Preterax and Diamicron Modified Release Controlled Evaluation trial and the Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes study have shown that intensive blood glucose control can lead to an increase in mortality or CV events and hypoglycemia was the main reason contributing to such events [28, 29]. Several risk factors, including age, the duration of diabetes and insulin therapy, polypharmacy, a previous history of hypoglycemia, and the presence of macroalbuminuria, were found to be associated with hypoglycemia [30, 31, 32]. In this study, the incidence of hypoglycemia was significantly lower in patients treated with exenatide plus insulin glargine than in patients treated with insulin lispro plus glargine. Therefore, a decrease in hypoglycemia may reduce the incidence of CV events, as confirmed in previous studies [10, 33, 34].

The study protocol has a certain limitation as we did not perform a blinding procedure during the follow-up, which might have led to bias during the intervention. However, to avoid a selection bias, physicians, or nurses were blinded to the treatment assignment until the randomization was allocated [35]. In addition, we did not collect all the information we had originally planned due to the discontinuation of follow-ups. Nonetheless, the MMRM on the FAS, which included at least 2 different follow-up dates, was sufficiently robust to detect differences in the percentage change of the UAER between the 2 groups.

In conclusion, this multi-center randomized parallel study indicated that exenatide plus insulin glargine for 24 weeks achieved a reduction in albuminuria in T2DM patients with DKD. Results from this study provide evidence for the use of short-acting exenatide, in addition to insulin, to improve kidney function in patients with macroalbuminuria.

Statement of Ethics

This study was approved by the institutional research ethics committee of Nanfang Hospital, Guangdong Second Traditional Chinese Medicine Hospital, Guangdong Provincial Hospital of Chinese Medicine, and Guangdong second provincial general hospital. All individuals provided informed consent prior to their inclusion in the study. This trial was performed in compliance with the Helsinki Declaration and registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02690883).

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Sources

We thank AstraZeneca China and 3SBio Inc. for covering the study fees and providing drugs and examination items during the follow-up.

Author Contributions

X.Y.W., Q.Z., and H.J.Z. performed data analysis, interpreted the results, and wrote the manuscript. Y.M.X. and M.P.G. contributed to the design of the study, as well as reviewed and edited the manuscript. S.Y.S., W.M., M.C.Z., J.M.L., J.L.B., X.Y.T., H.Y.Z., J.L.H., G.G.X., and P.L. conducted patients' enrollment and follow-ups. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge all patients and investigators who were involved in this study.

References

- 1.Afkarian M, Zelnick LR, Hall YN, Heagerty PJ, Tuttle K, Weiss NS, et al. Clinical manifestations of kidney disease among US adults with diabetes, 1988–2014. JAMA. 2016 Aug;316((6)):602–10. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.10924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang L, Long J, Jiang W, Shi Y, He X, Zhou Z, et al. Trends in chronic kidney disease in China. N Engl J Med. 2016 Sep;375((9)):905–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1602469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wen CP, Chang CH, Tsai MK, Lee JH, Lu PJ, Tsai SP, et al. Diabetes with early kidney involvement may shorten life expectancy by 16 years. Kidney Int. 2017 Aug;92((2)):388–96. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2017.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yamanouchi M, Furuichi K, Hoshino J, Toyama T, Hara A, Shimizu M, et al. Nonproteinuric versus proteinuric phenotypes in diabetic kidney disease: a propensity score-matched analysis of a nationwide, biopsy-based cohort study. Diabetes Care. 2019 May;42((5)):891–902. doi: 10.2337/dc18-1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang JK, Wang YY, Liu C, Shi TT, Lu J, Cao X, et al. Urine proteome specific for eye damage can predict kidney damage in patients with type 2 diabetes: a case-control and a 5.3-year prospective cohort study. Diabetes Care. 2017 Feb;40((2)):253–60. doi: 10.2337/dc16-1529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Packham DK, Alves TP, Dwyer JP, Atkins R, de Zeeuw D, Cooper M, et al. Relative incidence of ESRD versus cardiovascular mortality in proteinuric type 2 diabetes and nephropathy: results from the DIAMETRIC (diabetes mellitus treatment for renal insufficiency consortium) database. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012 Jan;59((1)):75–3. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heerspink HJ, Kröpelin TF, Hoekman J, de Zeeuw D. Drug-induced reduction in albuminuria is associated with subsequent renoprotection: a meta-analysis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015 Aug;26((8)):2055–64. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2014070688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aroda VR. A review of GLP-1 receptor agonists: evolution and advancement, through the lens of randomised controlled trials. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2018 Feb;20((Suppl 1)):22–33. doi: 10.1111/dom.13162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andersen A, Lund A, Knop FK, Vilsboll T. Glucagon-like peptide 1 in health and disease. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2018 May;14((3)):390–3. doi: 10.1038/s41574-018-0016-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kristensen SL, Rørth R, Jhund PS, Docherty KF, Sattar N, Preiss D, et al. Cardiovascular, mortality, and kidney outcomes with GLP-1 receptor agonists in patients with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cardiovascular outcome trials. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019 Oct;7((10)):776–85. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(19)30249-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park CW, Kim HW, Ko SH, Lim JH, Ryu GR, Chung HW, et al. Long-term treatment of glucagon-like peptide-1 analog exendin-4 ameliorates diabetic nephropathy through improving metabolic anomalies in db/db mice. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007 Apr;18((4)):1227–38. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006070778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang H, Zhang X, Hu C, Lu W. Exenatide reduces urinary transforming growth factor-β1 and type IV collagen excretion in patients with type 2 diabetes and microalbuminuria. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2012 Jun;35((6)):483–8. doi: 10.1159/000337929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Castellana M, Cignarelli A, Brescia F, Laviola L, Giorgino F. GLP-1 receptor agonist added to insulin versus basal-plus or basal-bolus insulin therapy in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2019 Jan;35((1)):e3082. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.3082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.American Diabetes Association 10. Cardiovascular disease and risk management: standards of medical care in diabetes-2019. Diabetes Care. 2019 Jan;42((Suppl 1)):S103–23. doi: 10.2337/dc19-S010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yanagisawa K, Ashihara J, Obara S, Wada N, Takeuchi M, Nishino Y, et al. Switching to multiple daily injection therapy with glulisine improves glycaemic control, vascular damage and treatment satisfaction in basal insulin glargine-injected diabetic patients. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2014 Nov;30((8)):693–700. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.2537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Denker M, Boyle S, Anderson AH, Appel LJ, Chen J, Fink JC, et al. Chronic renal insufficiency cohort study (CRIC): overview and summary of selected findings. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015 Nov;10((11)):2073–83. doi: 10.2215/CJN.04260415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mann JFE, Ørsted DD, Brown-Frandsen K, Marso SP, Poulter NR, Rasmussen S, et al. Liraglutide and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2017;377((9)):839–2198. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1616011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Muskiet MHA, Tonneijck L, Huang Y, Liu M, Saremi A, Heerspink HJL, et al. Lixisenatide and renal outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and acute coronary syndrome: an exploratory analysis of the ELIXA randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018 Nov;6((11)):859–69. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(18)30268-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gerstein HC, Colhoun HM, Dagenais GR, Diaz R, Lakshmanan M, Pais P, et al. Dulaglutide and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes: an exploratory analysis of the REWIND randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2019 Jul;394((10193)):131–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31150-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bethel MA, Mentz RJ, Merrill P, Buse JB, Chan JC, Goodman SG, et al. Microvascular and cardiovascular outcomes according to renal function in patients treated with once-weekly exenatide: insights from the EXSCEL Trial. Diabetes Care. 2020 Feb;43((2)):446–52. doi: 10.2337/dc19-1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.American Diabetes Association Addendum. 9. pharmacologic approaches to glycemic treatment. Diabetes Care. 2020 Jan;43:S98–110. doi: 10.2337/dc20-S009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lewis EJ, Hunsicker LG, Clarke WR, Berl T, Pohl MA, Lewis JB, et al. Renoprotective effect of the angiotensin-receptor antagonist irbesartan in patients with nephropathy due to type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2001 Sep;345((12)):851–60. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brenner BM, Cooper ME, de Zeeuw D, Keane WF, Mitch WE, Parving HH, et al. Effects of losartan on renal and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2001 Sep;345((12)):861–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Imai E, Chan JC, Ito S, Yamasaki T, Kobayashi F, Haneda M, et al. Effects of olmesartan on renal and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes with overt nephropathy: a multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled study. Diabetologia. 2011 Dec;54((12)):2978–86. doi: 10.1007/s00125-011-2325-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fried LF, Emanuele N, Zhang JH, Brophy M, Conner TA, Duckworth W, et al. Combined angiotensin inhibition for the treatment of diabetic nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2013 Nov;369((20)):1892–903. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1303154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Packham DK, Wolfe R, Reutens AT, Berl T, Heerspink HL, Rohde R, et al. Sulodexide fails to demonstrate renoprotection in overt type 2 diabetic nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012 Jan;23((1)):123–30. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2011040378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Navaneethan SD, Yehnert H, Moustarah F, Schreiber MJ, Schauer PR, Beddhu S. Weight loss interventions in chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009 Oct;4((10)):1565–74. doi: 10.2215/CJN.02250409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Patel A, MacMahon S, Chalmers J, Neal B, Billot L, Woodward M, et al. Intensive blood glucose control and vascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2008 Jan;358((24)):2560–72. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gerstein HC, Miller ME, Byington RP, Goff DC, Bigger JT, Buse JB, et al. Effects of intensive glucose lowering in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2008 Jan;358((24)):2545–59. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Donnelly LA, Morris AD, Frier BM, Ellis JD, Donnan PT, Durrant R, et al. Frequency and predictors of hypoglycaemia in Type 1 and insulin-treated Type 2 diabetes: a population-based study. Diabet Med. 2005 Jun;22((6)):749–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2005.01501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cariou B, Fontaine P, Eschwege E, Lièvre M, Gouet D, Huet D, et al. Frequency and predictors of confirmed hypoglycaemia in type 1 and insulin-treated type 2 diabetes mellitus patients in a real-life setting: results from the DIALOG study. Diabetes Metab. 2015 Apr;41((2)):116–25. doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2014.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yun JS, Ko SH, Ko SH, Song KH, Ahn YB, Yoon KH, et al. Presence of macroalbuminuria predicts severe hypoglycemia in patients with type 2 diabetes: a 10-year follow-up study. Diabetes Care. 2013 May;36((5)):1283–9. doi: 10.2337/dc12-1408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Holman RR, Bethel MA, Mentz RJ, Thompson VP, Lokhnygina Y, Buse JB, et al. Effects of once-weekly exenatide on cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2017 Sep;377((13)):1228–39. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1612917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gerstein HC, Colhoun HM, Dagenais GR, Diaz R, Lakshmanan M, Pais P, et al. Dulaglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes (REWIND): a double-blind, randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2019 Jul;394((10193)):121–30. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31149-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moher D, Hopewell S, Schulz KF, Montori V, Gøtzsche PC, Devereaux PJ, et al. CONSORT 2010 explanation and elaboration: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ. 2010;340:c869. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary data