Abstract

Background:

Given the emergent aging population, the identification of effective treatments for Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is critical.

Objective:

We investigated the therapeutic efficacy of JHU-083, a brain-penetrable glutamine antagonist, in treating AD using the humanized APOE4 knock-in mouse model.

Methods:

Cell culture studies were performed using BV2 cells and primary microglia isolated from hippocampi of adult APOE4 knock-in mice to evaluate the effect of JHU-083 treatment on LPS-induced glutaminase (GLS) activity and inflammatory markers. Six-month-old APOE4 knock-in mice were administered JHU-083 or vehicle via oral gavage 3x/week for 4–5 months and cognitive performance was assessed using the Barnes maze. Target engagement in the brain was confirmed using a radiolabeled GLS enzymatic activity assay, and electrophysiology, gastrointestinal histology, blood chemistry, and CBC analyses were conducted to evaluate the tolerability of JHU-083.

Results:

JHU-083 inhibited the LPS-mediated increases in GLS activity, nitic oxide release, and pro-inflammatory cytokine production in cultured BV2 cells and primary microglia isolated from APOE4 knock-in AD mice. Chronic treatment with JHU-083 in APOE4 mice improved hippocampal-dependent Barnes maze performance. Consistent with the cell culture findings, postmortem analyses of APOE4 mice showed increased GLS activity in hippocampal CD11b+ enriched cells versus age-matched controls, which was completely normalized by JHU-083 treatment. JHU-083 was well-tolerated, showing no weight loss effect or overt behavioral changes. Peripheral nerve function, gastrointestinal histopathology, and CBC/clinical chemistry parameters were all unaffected by chronic JHU-083 treatment.

Conclusion:

These results suggest that the attenuation of upregulated hippocampal glutaminase by JHU-083 represents a new therapeutic strategy for AD.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, APOE, glutamate, glutaminase, microglia

INTRODUCTION

The number of individuals living with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and related dementias in the United States is expected to double to over 12 million within the next 30 years [1]. AD is thought to be caused by a combination of environmental, hormonal, genetic, and lifestyle factors that trigger an inflammatory and neurotoxic cascade in the brain [2]. Current pharmacological and behavioral treatment approaches yield only minimal improvements, making the identification of new therapeutic strategies essential.

Glutamate is essential for normal brain development and cognitive function, but excess production leads to excitotoxic neurodegeneration. The enzyme glutaminase (GLS), which deaminates glutamine into glutamate, is a primary generator of the excitatory neurotransmitter glutamate in the central nervous system (CNS). Microglial GLS activity levels increase under conditions of neuroinflammation, resulting in increased CNS glutamate production [3–5]. Glutamine antagonists, such as 6-diazo-5-oxo-L-norleucine (DON), rescue neurotoxicity and behavioral deficits in disease models where excess glutamate is thought to be pathogenic, including HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders [6], multiple sclerosis [7], Rett syndrome [8], viral infection [9], and cerebral malaria [10]. DON is not clinically viable, however, due to dose-limiting toxic gastrointestinal-related side effects [11, 12]. Given the clinical potential of glutamine inhibition in the brain, our laboratory recently synthesized a prodrug of DON, termed JHU-083, that penetrates and is cleaved to DON in the brain leading to less peripheral exposure and enhanced tolerability [10, 13, 14].

Although excess CNS glutamate production has long been implicated in AD pathogenesis [15, 16] and numerous studies show that microglial GLS is a critical mediator of glutamate-mediated neuronal damage under neuroinflammatory conditions [13, 17, 18], the role of microglial GLS in AD pathogenesis remains relatively unexplored. To date, only neuronal or whole brain GLS levels have been evaluated in AD [19–21]. Here we measure the effects of JHU-083 on GLS activity and markers of inflammation in stimulated BV2 cells and primary microglia (CD11b+ enriched cells, a population made up of >95% microglia [22]) isolated from hippocampi of apolipoprotein E4 (APOE4) knock-in mice. We then evaluate the effects of chronic GLS inhibition via daily oral administration of JHU-083 in APOE4 knock-in mice, which experience accelerated neuroinflammation, amyloid-β (Aβ) brain deposition, and cognitive impairment similar to human APOE4 carriers with AD [23, 24].

MATERIALS AND METHODS

BV2 microglial studies

BV2 microglial cells were cultured, stimulated with 300 EU/mL LPS (Sigma Aldrich L5024), and treated with 1 or 10 μM JHU-083. Following 24 h of treatment, supernatants were collected and cells were snap-frozen for GLS activity measurement as detailed below. Nitric oxide was also measured in the supernatant according to manufacturer’s instructions, with the more stable metabolite nitrite serving as the metric (Promega G2930). For viability analyses, BV2 cells were stimulated with 300 EU/mL LPS and treated with 1 or 10 μM JHU-083 for 24 h. Subsequently, 5 mg/mL MTT solution was added for 4 h and 85 μL was removed and added to 150 μL DMSO. Samples were then analyzed at 540 nM.

Hippocampal CD11b+ cell isolations

Animals were deeply anesthetized with isoflurane, and cardiac perfusions were performed. Hippocampi, defined by landmarks and neuroanatomical nomenclature in the atlas of Franklin and Paxinos (anteroposterior: −0.95 – −4.03 mm, mediolateral: ±3.75 mm from bregma, dorsoventral: −1.75 – −5.1 mm from the dura) [25], were rapidly and bilaterally dissected on an ice-cold plate. CD11b+ cells were isolated from hippocampi as previously described [13]. Briefly, brain tissue was minced in HBSS (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and dissociated with neural tissue dissociation kits (MACS Militenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA). After passing through a 70 μm cell strainer, homogenates were centrifuged at 300 g for 10 min. Supernatants were removed, cell pellets were resuspended, and myelin was removed by Myelin Removal Beads II (MACS Militenyi Biotec). Myelin-removed cell pellets were resuspended and incubated with CD11b MicroBeads (MACS Militenyi Biotec) for 15 min, loaded on LS columns and separated on a quadroMACS magnet. CD11b+ cells were flushed out, washed, and resuspended in sterile HBSS (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Viable cells were counted with a hemacytometer and 0.1% trypan blue staining. Each brain extraction yielded approximately 5 × 105 viable CD11b+ cells. Cells for in vitro studies were cultured immediately. Cells from mice in the treatment and behavior studies were stored at −80°C until GLS activity assays were performed.

APOE4 primary microglia culture studies

CD11b+ cells isolated from the brains of 4-month-old APOE4 knock-in mice were cultured in a 96-well plate at 15,000 cells/well in complete phenol-free media made up of DMEM/F12(Gibco, Thermofisher) +1% Pen/Strep(Gibco) +10% FBS(Gibco) +10 ng/ml M-CSF (R & D Systems). After 5 days in culture, media was changed to phenol-free and glutamine-free media made up of DMEM(Gibco) +1% Pen/Strep, and cells were stimulated with 300EU/mL LPS (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis MO) and treated with 1 or 10 μM JHU-083. Following 24 h of treatment, supernatants were collected for cytokine multi-plex analyses (V-Plex Mouse Proinflammatory Cytokine Panel 1, Mesoscale Discovery) and cells were snap-frozen for GLS activity measurement as detailed below. Cell viability was measured using Cell Counting Kit-8 according to manufacturer’s instructions (Dojindo Molecular Technologies, Inc).

GLS enzymatic activity assay

GLS activity was measured in cells or tissue samples (n = 4–13) as previously described [26]. Briefly, cells were pelleted by centrifugation at 300 g for 5 min, and samples were resuspended in ice-cold potassium phosphate buffer (45 mM, pH 8.2) containing protease inhibitors (Roche) and sonicated using Kontes’ Micro Ultrasonic Cell Disrupter. Homogenates were incubated with [3H]-glutamine (0.09 μM, 2.73 μCi) for 180 min at room temperature in 50 μL volumes in a 96-well microplate. The assay was terminated with imidazole buffer (20 mM, pH 7). 96-well spin columns packed with 200–400 mesh anion ion-exchange resin (Bio-Rad) separated the substrate and reaction product. Unreacted [3H]-glutamine was removed by washing with imidazole buffer and [3H]-glutamate was eluted with 0.1 N HCl and analyzed for radioactivity using Perkin Elmer’s TopCount instrument in conjunction with 96-well LumaPlates. Total protein was measured using BioRad’s Detergent Compatible Protein Assay kit.

Animals and housing

Female APOE4 knock-in mice with targeted replacement of the mouse APOE gene with the human APOE4 isoform (Taconic, Germantown, NY, model #1549) and C57BL/6 wild type mice (Taconic) were housed in the Miller Research Building Johns Hopkins animal facility. Females were selected due to the reported enhanced susceptibility to APOE4-driven deficits in cognitive function in both female humans [27, 28] and female mice [29, 30]. Animals were housed in a reverse light-dark cycle to allow for daytime behavior testing during the animals’ dark (awake) cycle. All experimental procedures were approved by the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Animal Care and Use Committee.

JHU-083 drug treatment

Beginning at 6 months of age, animals were administered 1.83 mg/kg JHU-083 (equivalent to 1 mg/kg DON) or vehicle (5% ethanol and 95% 50 mM HEPES) via oral gavage 3×/week (n =13/group). This dosing regimen was chosen based on past pharmacokinetic and chronic CNS efficacy studies [13, 14]. Body weight was monitored 3X per week throughout the experiment, and no changes were observed due to JHU-083 treatment. Mice underwent behavioral testing, detailed below, then 10–11-month-old mice were sacrificed and hippocampal microglial enriched cells were collected for GLS activity determination. An age-matched wildtype cohort was also included to evaluate AD-related changes in GLS activity.

Behavioral tests

From 6 months of age, a time of known cognitive impairment in APOE4 mice [31], mice (n =13) received 4 months of three times per week oral dosing of vehicle or JHU-083, and then underwent Barnes maze testing as described with minor modifications [32]. Briefly, mice were trained to locate a target box and learning and memory were assessed in 2 trials per day over 4 consecutive days. If the animal did not find the target box in 3 min, a maximum latency time of 180 s was recorded, the test ended, and the mouse was gently guided to the box. Animals were tracked using ANYmaze software (Stoelting, Wood Dale, IL). Data were blindly collected from two separate experiments performed in the Johns Hopkins Miller Research Building Behavioral Core Facility.

Toxicity evaluation

A separate cohort of WT mice were administered 1.83mg/kg JHU-083 (equivalent to 1mg/kg DON) or vehicle (5% ethanol and 95% 50 mM HEPES) via oral gavage 3 ×/week (n = 12/group) for one month. At two- and four-weeks post JHU-083 administration, mice were subjected to sciatic nerve electrophysiology recordings followed a standard protocol using an Evidence 3102evo EMG system (Neurosoft; Ivanovo, Russia) as previously described [33, 34]. Compound muscle action potentials (CMAPs) generated were recorded and analyzed using Neuro-MEP software (Neurosoft). Sensory nerve action potentials (SNAPs) were collected using a methodology modified from previously described methods [35]. CMAP amplitudes were defined as the “peak-to-peak” amplitude. SNAP amplitudes were defined using the negative peak amplitudes. Latencies were defined as the time from the stimulus start to the onset of the CMAP/SNAP trace. Nerve conduction velocities were defined as the latency/distance between recording and stimulating anodes. Following 4 weeks of dosing, mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and blood was collected via cardiac puncture and processed for CBC and clinical chemistry by the JHU Mouse Phenotyping Core Facility. Gastrointestinal tissue was dissected, snap frozen, and sent to IDEXX Laboratories (Westbrook, ME) for pathological analyses by a blinded observer.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were completed using GraphPad Prism 6. Comparisons on behavior tests were made with repeated measures two-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparison post-hoc test. Comparisons of GLS activity and NO levels were made with one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison post-hoc test. p values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

JHU-083 inhibits LPS-induced increases in GLS activity and nitric oxide release in BV2 cells

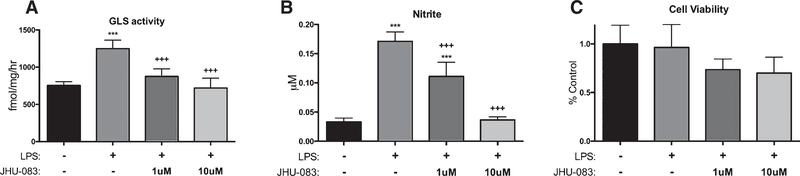

Cultured BV2 microglial cells stimulated with LPS exhibited a significant upregulation in GLS activity and in nitric oxide release; these increases were significantly and dose-dependently inhibited by JHU-083 (Fig. 1A, B, p <0.001). No changes in cell viability were observed with JHU-083 (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

JHU-083 inhibits LPS-mediated increase in glutaminase activity and nitrite release in cultured BV2 microglia. BV2 microglia were cultured, stimulated with LPS and treated with vehicle or JHU-083 for 24 h. GLS activity (A) and NO levels (B) released into the supernatant were significant increased by LPS treatment, and JHU-083 dose-dependently inhibited the increases. C) JHU-083 did not influence viability of BV2 cells. Significantly different from vehicle control at p < 0.001(***), significantly different from LPS control at p < 0.001(+++). Data are plotted as mean ± SD, n = 6–12/group.

JHU-083 inhibits LPS-induced increases in GLS activity and pro-inflammatory cytokine production in primary hippocampal microglia isolated from APOE4 mice

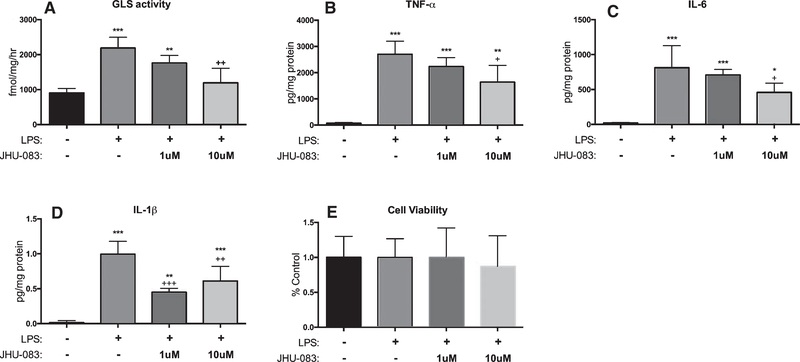

CD11b+ microglial cells isolated from the hippocampi of APOE4-TR mice exhibited significant upregulations in GLS activity and production of the pro-inflammatory cytokines TNFα, IL-6, IL-1β, IL-2, CXCL1, and IFNγ following LPS stimulation. Treatment with JHU-083 significantly decreased the LPS stimulation of both GLS activity and cytokine production in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2A–D and Supplementary Figure 1, p < 0.05). There were no LPS- or JHU-083-mediated changes in levels of IL-5 observed and JHU-083 had no effect on IL-12p70 or IL-10 levels (Supplementary Figure 1). Neither LPS stimulation nor JHU-083 impacted cell viability (Fig. 2E).

Fig. 2.

JHU-083 inhibits LPS-mediated increase in glutaminase activity and markers of inflammation in cultured primary microglia. CD11b+ cells isolated from hippocampi of APOE4 mice were cultured, stimulated with LPS and treated with vehicle or JHU-083 for 24 h. JHU-083 significantly reversed LPS-mediated elevations in (A) GLS activity, along with (B) TNF-α, (C) IL-6, and (D) IL-1β levels released into the supernatant, with no impact on (E) cell viability. Significantly different from vehicle control at p <0.05, p <0.01, p <0.001(***), significantly different from LPS control at p < 0.05(+), p < 0.01(++), p < 0.001(+++). Data are plotted as mean ± SD, n = 4–12/group.

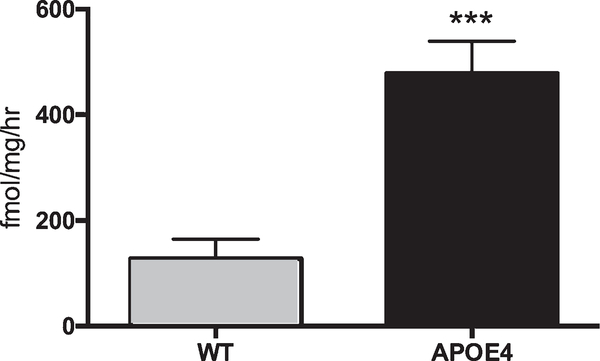

APOE4 genotype causes elevated GLS activity in hippocampal CD11b+ cells

A significant upregulation in GLS activity was observed in CD11b+ old APOE4 knock-in mice versus age-matched WT controls (Fig. 3, p < 0.001).

Fig. 3.

Glutaminase activity is upregulated in hippocampal CD11b+ cells of APOE4 mice. CD11b+ cells were isolated from hippocampi of untreated 11-month-old mice, and GLS activity levels were measured. Significantly different from WT at p < 0.001(***). Data are plotted as mean ± SD, n = 4–6.

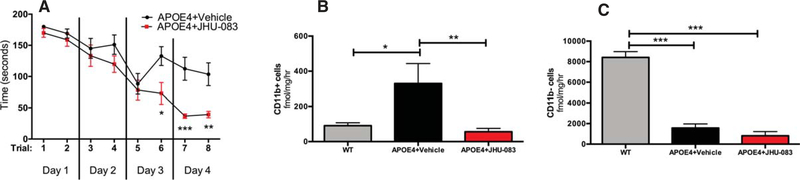

Chronic oral JHU-083 therapy improves cognition in APOE4 mice

APOE4 knock-in mice treated with chronic oral JHU-083 had significantly enhanced cognition as compared to APOE4 vehicle-treated mice as assessed by Barnes maze performance (Fig. 4A). A clear separation in performance was observed in trials 6–8, with JHU-083-treated APOE4 mice finding the maze significantly faster than vehicle-treated APOE4 (p <0.05). Two-way ANOVA revealed a significant JHU-083 treatment effect over time (p <0.01, F(1, 24) = 7.91).

Fig. 4.

Chronic oral JHU-083 therapy enhances Barnes maze performance and attenuates the rise of glutaminase (GLS) activity in hippocampal CD11b+ enriched cells in APOE4 mice. A) Following 3×/week treatment with vehicle or JHU083 for 3–4 months starting at 6 months of age, APOE4 mice were subjected to Barnes maze testing. Mice were trained and tested in 2 trials per day over 4 consecutive days. Two-way ANOVA revealed a significant JHU-083 treatment effect over time (p < 0.01), and Sidak’s multiple comparison post-hoc test revealed significant differences from vehicle on trials 6–8. B) CD11b+ cells were isolated from hippocampi of 10–11-month-old APOE4 and WT mice. GLS activity was significantly increased in APOE4 mice versus WT controls, while JHU-083 treatment significantly decreased GLS activity levels to those observed in WT mice. C) GLS activity was measured in cells remaining after CD11b+ cell enrichment. APOE4 mice treated with vehicle or JHU-083 had significantly lower GLS activity versus WT mice. Although JHU-083 treatment caused a trend decrease in GLS activity in APOE4 mice versus APOE4 + Vehicle, the effect did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.08). Significantly different at p < 0.05(*), p < 0.01(**), and p < 0.001(***). Data are plotted as mean ± SEM.

Chronic oral JHU-083 therapy normalizes elevated GLS activity in CD11b+ cells inAPOE4 mice

APOE4 knock-in mice had significantly increased GLS activity in microglial enriched CD11b+ cells versus WT mice, which was completely normalized by chronic JHU-083 treatment (Fig. 4B, p <0.05). GLS activity in CD11b− cells (mostly neurons and astrocytes) showed a significant decrease in GLS activity in both vehicle and JHU-083 treated APOE4 mice versus WT mice (Fig. 4C, p <0.001). A trend reduction was observed in GLS activity of CD11b− in APOE4+JHU-083 mice versus APOE4 + Vehicle mice, but this effect did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.08).

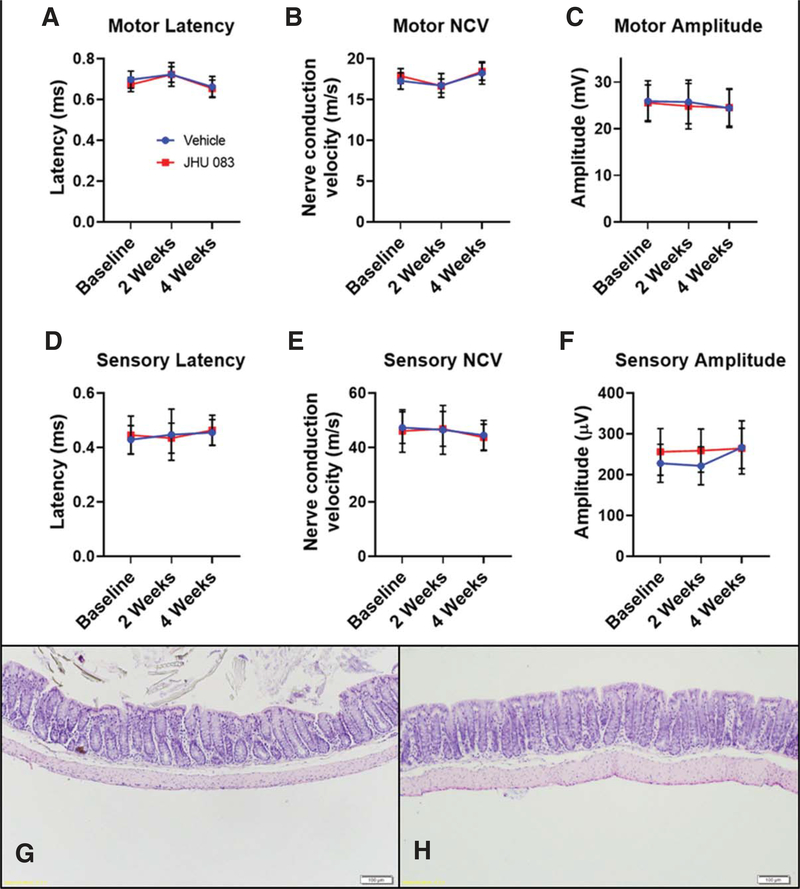

Chronic oral JHU-083 therapy is well-tolerated

To evaluate the tolerability of chronic JHU-083 treatment, a separate cohort of WT mice were treated with oral JHU-083 for one month. Electrophysiology tests conducted after 2 and 4 weeks of treatment showed no changes in motor and sensory peripheral nerve function as compared to vehicle-treated controls (Fig. 5A–F). CBC and clinical chemistry analyses from mice treated with JHU-083 were all within the normal range (Mouse Phenome Database at The Jackson Laboratory). GI histopathological analyses revealed no changes in colon tissue integrity due to JHU-083 treatment (Fig. 5G, H).

Fig. 5.

Chronic oral JHU-083 treatment does not induce sensory or motor neuropathies or gastrointestinal toxicity. A–C) 4 weeks of daily JHU-083 treatment (1.83 mg/kg) in WT mice did not alter motor electrophysiological function in the sciatic nerve as assessed by a lack of change in latency (A), nerve conduction velocity (NCV) (B), and amplitude (C). D, E) 4 weeks of daily JHU-083 treatment in WT mice did not alter sensory electrophysiological function in the sciatic nerve as assessed by a lack of change in latency (D), NCV (E), and amplitude(F). Data are plotted as mean ± SD. n = 12/group. G-H) 4 weeks of daily vehicle (G) or JHU-083 (H) treatment in WT mice did not cause any histological abnormalities in colon tissue. Showing representative figure from 5/group.

DISCUSSION

Microglia are critical regulators of glutamate release under inflammatory conditions, and their activation is a well-established contributor to AD pathogenesis [36, 37]. With activation, microglia undergo a shift from anti-inflammatory with Aβ plaque phagocytosis to pro-inflammatory with limited ability to clear Aβ plaques [38]. Microglial GLS is upregulated under inflammatory conditions [3–5]. Given the importance of microglial GLS in regulating inflammation and CNS glutamate levels [13, 17, 18] and the excitotoxic role of excess glutamate in AD and its underlying role in contributing to neurodegeneration and cognitive impairment [16], here we sought to examine the role of microglial GLS in regulating cognitive function in an AD-related mouse model.

The APOE4 genotype is the most prominent genetic risk factor for late-onset AD. Homozygous APOE4 allele status confers an odds ratio of developing AD of up to 14.9 versus APOE3/3 allele status [39]. In the humanized knock-in APOE4 mouse model of AD, mouse APOE exons are replaced with the human APOE4 isoform. Using this model, we observed a 3- to 4-fold upregulation in GLS activity of hippocampal CD11b+ enriched cells, a population made up of >95% microglia [22], in aged APOE4 mice versus wild type controls. These novel finding are consistent with the fact that the APOE4 genotype increases microglial reactivity [40]. E4-expressing microglia have heightened immune responses [41] and impaired ability to phagocytose Aβ [42] as compared to E2 and E3 microglia. It is therefore likely that that during disease progression, increased Aβ deposition causes elevated neuroinflammation [43], which in turn upregulates microglial GLS activity [3–5].

To examine the effect of microglial GLS inhibition, we evaluated JHU-083, a prodrug of the GLS1 and GLS2 inhibitor DON [3, 44], in BV2 microglial cells and primary microglia cultured from the hippocampi of APOE4 knock-in mice. In BV2 studies, we report that JHU-083 dose-dependently blocked the LPS-mediated increases in GLS activity. Additionally, JHU-083 attenuated nitric oxide formation and release in BV2 cells, which was also upregulated following LPS stimulation. Because JHU-083 inhibits glutamine-utilizing reactions, including arginine formation, it is likely that NO production is decreased due to decreased arginine availability. In primary microglia isolated from APOE4 mice, LPS induced a significant upregulation in GLS activity as well as robust increases in pro-inflammatory cytokines implicated in the pathogenesis of AD, including TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β [45]. Consistent with the findings in BV2 cells, JHU-083 significantly and dose-dependently inhibited the LPS-induce increase in GLS activity in the APOE4 primary microglia and concomitantly decreased the level of several pro-inflammatory cytokines. These data are in line with previous studies showing that LPS activation of microglia causes increases in both GLS activity and pro-inflammatory cytokines that can be reversed by GLS inhibition [46], but this is the first study to record these observations in APOE4+/+ microglial cells.

To examine the effects of chronic microglial GLS inhibition on cognition in AD, we treated APOE4 knock-in mice for 4 months with JHU-083, utilizing a dosing paradigm that we previously showed was well-tolerated and sufficient to inhibit microglial GLS activity [13]. Similar to human carriers, APOE4 mice experience learning and memory difficulties, accelerated development of Aβ plaques, and impaired Aβ clearance [23, 24]. Cognitive impairment, specifically in the hippocampal-dependent Barnes maze test utilized in the present study [31], and pathological damage have been detected in APOE4 mice as early as 3–4 months [47, 48]. In the current studies, treatment of APOE4 knock-in mice began at 6 months of age to determine if JHU-083 treatment could impact progression of already developing cognitive impairment. We report a significant improvement in cognitive function following chronic JHU-083 treatment as assessed by Barnes maze performance. In tandem, we observed a robust 3- to 4-fold upregulation of GLS enzymatic activity in hippocampal microglial-enriched cells in APOE4 hippocampi versus WT controls, which was completely attenuated by JHU-083. Analysis of GLS activity in the remaining CD11b- cell population showed significant reductions in enzymatic activity in both untreated and JHU-083 treated AD mouse groups.

Several studies have examined GLS levels in various brain regions of AD patients, but results are conflicting. Reduced GLS levels were reported in cortical [20] and hippocampal [21] neurons of AD patients, while increased levels were found in the prefrontal cortex of AD patients [19]. The methodological differences of these papers, specifically the brain regions studied, AD patient population included, tissue preparation, and quantification methods, complicates data comparison. To our knowledge, only two previous studies have examined GLS activity in a mouse model of AD. Increases in GLS levels were observed in cortical homogenates from APP/PS1 mice [49], while a decrease in GLS activity levels was reported in whole brains from APOE4 mice [50]. Technical differences and age of the mice make direct comparisons between studies impossible, but the present study additionally highlights the importance of characterizing cell populations in order to interpret GLS activity data. Here, increased GLS activity was observed in AD mice in isolated CD11b+ cells, while GLS activity in the remaining non-CD11b+ cell population, comprised of mostly neurons and astroctyes, was decreased in AD mice versus WT controls. We speculate that the overall decrease in GLS activity observed in both drug and vehicle treated AD mice may be due to altered neuronal morphology and decreased neuronal spine density [50, 51]. The APOE4 genotype causes signs of AD-related neuronal pathology in the mouse hippocampus as early as 1 month of age [48]. Further studies are required to explore this possibility. All of the above studies, however, measured GLS in neuronal or mixed cell populations, making the present study the first to specifically measure the role of microglial-enriched GLS in AD.

The present study was designed to evaluate the impact of microglial GLS on AD progression using the newly discovered orally bioavailable, brain penetrable glutamine antagonist JHU-083. Toxicity studies conducted here show that unlike DON [11, 12], JHU-083 is well-tolerated, causing neither peripheral neuropathy nor measurable CBC changes or disruption of GI tissue integrity. Although these data suggest that upregulation of microglial GLS activity is contributory to cognitive decline in AD, there are several limitations to this work. First, although we observe statistically significant inhibition of GLS activity in CD11b+ cells made up of >95% microglia [22], near-significant inhibition was observed in CD11b− cells, so follow-up studies are required to more extensively tease apart the therapeutic role of GLS inhibition in CD11b+ versus CD11b− cells. The omission of wild type mice treated with vehicle or JHU-083 in the present cognitive studies is an additional limitation. Cognitive impairment is very well-documented in APOE4 knock-in mice at or before the 10–11-month age tested in this study [31, 52], but WT mice are required in future studies to determine if JHU-083 restores cognitive function in APOE4 mice back to WT baseline function. Additionally, previous research has reported no behavioral or cognitive effects of JHU-083 in WT mice [13, 53], but future studies will include WT mice treated JHU-083 to confirm these findings. Follow-up studies are also needed to determine the optimal timing and duration of drug administration and the interplay of APOE4 genotype and sex in microglial GLS activity, as only female APOE4 mice were utilized in this study given their more severe cognition deficit phenotype [27–30]. Previous studies have shown a reduction of HIV-induced elevated cerebrospinal fluid glutamate levels due to JHU-083 treatment [54], and future studies will determine if this normalization also occurs in AD mice. Finally, additional studies are required in order to examine how JHU-083 treatment impacts other glutamine-utilizing enzymes. Nonetheless the present studies provide a novel and critical connection between elevated microglial GLS activity and disruptions in cognitive function in AD.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Under a license agreement between Dracen Pharmaceuticals, Inc. and the Johns Hopkins University, the University, Dr. Slusher is entitled to royalty distributions related to technology used in the research described in this publication. In addition, Dr. Slusher holds equity in Dracen Pharmaceuticals, Inc. This arrangement has been reviewed and approved by the Johns Hopkins University in accordance with its conflict of interest policies.

This project was supported by NIH/NIMH P30 MH075673-S1, NIH/NCCIH K01 AT010984, NIH/NIA R01 AG065168, NIH/NIDA R01 DA041208, and NIH/NINDS R01 NS113140.

Footnotes

Authors’ disclosures available online (https://www.j-alz.com/manuscript-disclosures/19-0588r2).

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

The supplementary material is available in the electronic version of this article: https://dx.doi.org/10.3233/JAD-190588.

REFERENCES

- [1].Matthews KA, Xu W, Gaglioti AH, Holt JB, Croft JB, Mack D, McGuire LC (2019) Racial and ethnic estimates of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias in the United States (2015–2060) in adults aged>/=65 years. Alzheimers Dement 15, 17–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Eid A, Mhatre I, Richardson JR (2019) Gene-environment interactions in Alzheimer’s disease: A potential path to precision medicine. Pharmacol Ther 199, 173–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Thomas AG, O’Driscoll CM, Bressler J, Kaufmann W, Rojas CJ, Slusher BS (2014) Small molecule glutaminase inhibitors block glutamate release from stimulated microglia. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 443, 32–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Huang Y, Zhao L, Jia B, Wu L, Li Y, Curthoys N, Zheng JC (2011) Glutaminase dysregulation in HIV-1-infected human microglia mediates neurotoxicity: Relevant to HIV-1-associated neurocognitive disorders. J Neurosci 31, 15195–15204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Takeuchi H, Jin S, Wang J, Zhang G, Kawanokuchi J, Kuno R, Sonobe Y, Mizuno T, Suzumura A (2006) Tumor necrosis factor-alpha induces neurotoxicity via glutamate release from hemichannels of activated microglia in an autocrine manner. J Biol Chem 281, 21362–21368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Erdmann N, Zhao J, Lopez AL, Herek S, Curthoys N, Hexum TD, Tsukamoto T, Ferraris D, Zheng J (2007) Glutamate production by HIV-1 infected human macrophage is blocked by the inhibition of glutaminase. J Neurochem 102, 539–549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Shijie J, Takeuchi H, Yawata I, Harada Y, Sonobe Y, Doi Y, Liang J, Hua L, Yasuoka S, Zhou Y, Noda M, Kawanokuchi J, Mizuno T, Suzumura A (2009) Blockade of glutamate release from microglia attenuates experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis in mice. Tohoku J Exp Med 217, 87–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Maezawa I, Jin LW (2010) Rett syndrome microglia damage dendrites and synapses by the elevated release of glutamate. J Neurosci 30, 5346–5356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Manivannan S, Baxter VK, Schultz KL, Slusher BS, Griffin DE (2016) Protective effects of glutamine antagonist 6-diazo-5-oxo-l-norleucine in mice with alphavirus encephalomyelitis. J Virol 90, 9251–9262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Gordon EB, Hart GT, Tran TM, Waisberg M, Akkaya M, Kim AS, Hamilton SE, Pena M, Yazew T, Qi CF, Lee CF, Lo YC, Miller LH, Powell JD, Pierce SK (2015) Targeting glutamine metabolism rescues mice from late-stage cerebral malaria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112, 13075–13080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Magill GB, Myers WP, Reilly HC, Putnam RC, Magill JW, Sykes MP, Escher GC, Karnofsky DA, Burchenal JH (1957) Pharmacological and initial therapeutic observations on 6-diazo-5-oxo-1-norleucine (DON) in human neoplastic disease. Cancer 10, 1138–1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Earhart RH, Amato DJ, Chang AY, Borden EC, Shiraki M, Dowd ME, Comis RL, Davis TE, Smith TJ (1990) Phase II trial of 6-diazo-5-oxo-L-norleucine versus aclacinomycin-A in advanced sarcomas and mesotheliomas. Invest New Drugs 8, 113–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Zhu X, Nedelcovych MT, Thomas AG, Hasegawa Y, Moreno-Megui A, Coomer W, Vohra V, Saito A, Perez G, Wu Y, Alt J, Prchalova E, Tenora L, Majer P, Rais R, Rojas C, Slusher BS, Kamiya A (2019) JHU-083 selectively blocks glutaminase activity in brain CD11b(+) cells and prevents depression-associated behaviors induced by chronic social defeat stress. Neuropsychopharmacology 44, 683–694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Riggle BA, Sinharay S, Schreiber-Stainthorp W, Munasinghe JP, Maric D, Prchalova E, Slusher BS, Powell JD, Miller LH, Pierce SK, Hammoud DA (2018) MRI demonstrates glutamine antagonist-mediated reversal of cerebral malaria pathology in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 115, E12024–E12033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Zadori D, Veres G, Szalardy L, Klivenyi P, Vecsei L (2018) Alzheimer’s disease: Recent concepts on the relation of mitochondrial disturbances, excitotoxicity, neuroinflammation, and kynurenines. J Alzheimers Dis 62, 523–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Wang R, Reddy PH (2017) Role of glutamate and NMDA receptors in Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis 57, 1041–1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Pais TF, Figueiredo C, Peixoto R, Braz MH, Chatterjee S (2008) Necrotic neurons enhance microglial neurotoxicity through induction of glutaminase by a MyD88-dependent pathway. J Neuroinflammation 5, 43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Wu B, Huang Y, Braun AL, Tong Z, Zhao R, Li Y, Liu F, Zheng JC (2015) Glutaminase-containing microvesicles from HIV-1-infected macrophages and immune-activated microglia induce neurotoxicity. Mol Neurodegener 10, 61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Burbaeva G, Boksha IS, Tereshkina EB, Savushkina OK, Starodubtseva LI, Turishcheva MS (2005) Glutamate metabolizing enzymes in prefrontal cortex of Alzheimer’s disease patients. Neurochem Res 30, 1443–1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Akiyama H, McGeer PL, Itagaki S, McGeer EG, Kaneko T (1989) Loss of glutaminase-positive cortical neurons in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurochem Res 14, 353–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Kowall NW, Beal MF (1991) Glutamate-, glutaminase-, and taurine-immunoreactive neurons develop neurofibrillary tangles in Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Neurol 29,162–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Sharma K, Schmitt S, Bergner CG, Tyanova S, Kannaiyan N, Manrique-Hoyos N, Kongi K, Cantuti L, Hanisch UK, Philips MA, Rossner MJ, Mann M, Simons M (2015) Cell type- and brain region-resolved mouse brain proteome. Nat Neurosci 18, 1819–1831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Holtzman DM, Herz J, Bu G (2012) Apolipoprotein E and apolipoprotein E receptors: Normal biology and roles in Alzheimer disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2, a006312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Schmechel DE, Saunders AM, Strittmatter WJ, Crain BJ, Hulette CM, Joo SH, Pericak-Vance MA, Goldgaber D, Roses AD (1993) Increased amyloid beta-peptide deposition in cerebral cortex as a consequence of apolipoprotein E genotype in late-onset Alzheimer disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 90, 9649–9653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Paxinos G, Franklin KBJ (2013) Paxinos and Franklin’s the mouse brain in stereotaxic coordinates. Elsevier/Academic Press, Amsterdam. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Engler JA, Gottesman JM, Harkins JC, Urazaev AK, Lieber- man EM, Grossfeld RM (2002) Properties of glutaminase of crayfish CNS: Implications for axon-glia signaling. Neuroscience 114, 699–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Beydoun MA, Boueiz A, Abougergi MS, Kitner-Triolo MH, Beydoun HA, Resnick SM, O’Brien R, Zonderman AB (2012) Sex differences in the association of the apolipopro- tein E epsilon 4 allele with incidence of dementia, cognitive impairment, and decline. Neurobiol Aging 33, 720–731.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Mortensen EL, Hogh P (2001) A gender difference in the association between APOE genotype and age-related cognitive decline. Neurology 57, 89–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Raber J, Wong D, Buttini M, Orth M, Bellosta S, Pitas RE, Mahley RW, Mucke L (1998) Isoform-specific effects of human apolipoprotein E on brain function revealed in ApoE knockout mice: Increased susceptibility of females. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95, 10914–10919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Leung L, Andrews-Zwilling Y, Yoon SY, Jain S, Ring K, Dai J, Wang MM, Tong L, Walker D, Huang Y (2012) Apolipoprotein E4 causes age- and sex-dependent impairments of hilar GABAergic interneurons and learning and memory deficits in mice. PLoS One 7, e53569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Rodriguez GA, Burns MP, Weeber EJ, Rebeck GW (2013) Young APOE4 targeted replacement mice exhibit poor spatial learning and memory, with reduced dendritic spine density in the medial entorhinal cortex. Learn Mem 20, 256–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Rahn KA, Watkins CC, Alt J, Rais R, Stathis M, Grishkan I, Crainiceau CM, Pomper MG, Rojas C, Pletnikov MV, Calabresi PA, Brandt J, Barker PB, Slusher BS, Kaplin AI (2012) Inhibition of glutamate carboxypeptidase II (GCPII) activity as a treatment for cognitive impairment in multiple sclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109, 20101–20106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Tallon C, Rockenstein E, Masliah E, Farah MH (2017) Increased BACE1 activity inhibits peripheral nerve regeneration after injury. Neurobiol Dis 106, 147–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Tallon C, Russell KA, Sakhalkar S, Andrapallayal N, Farah MH (2016) Length-dependent axo-terminal degeneration at the neuromuscular synapses of type II muscle in SOD1 mice. Neuroscience 312, 179–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Liu Y, Sebastian B, Liu B, Zhang Y, Fissel JA, Pan B, Polydefkis M, Farah MH (2017) Sensory and autonomic function and structure in footpads of a diabetic mouse model. Sci Rep 7, 41401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Nordengen K, Kirsebom BE, Henjum K, Selnes P, Gisladottir B, Wettergreen M, Torsetnes SB, Grontvedt GR, Waterloo KK, Aarsland D, Nilsson LNG, Fladby T (2019) Glial activation and inflammation along the Alzheimer’s disease continuum. J Neuroinflammation 16, 46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Ransohoff RM (2016) How neuroinflammation contributes to neurodegeneration. Science 353, 777–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Shen Z, Bao X, Wang R (2018) Clinical PET imaging of microglial activation: Implications for microglial therapeutics in Alzheimer’s disease. Front Aging Neurosci 10, 314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Farrer LA, Cupples LA, Haines JL, Hyman B, Kukull WA, Mayeux R, Myers RH, Pericak-Vance MA, Risch N, van Duijn CM (1997) Effects of age, sex, and ethnicity on the association between apolipoprotein E genotype and Alzheimer disease. A meta-analysis. APOE and Alzheimer disease meta analysis consortium. JAMA 278, 1349–1356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Rodriguez GA, Tai LM, LaDu MJ, Rebeck GW (2014) Human APOE4 increases microglia reactivity at Abeta plaques in a mouse model of Abeta deposition. J Neuroinflammation 11, 111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Shi Y, Yamada K, Liddelow SA, Smith ST, Zhao L, Luo W, Tsai RM, Spina S, Grinberg LT, Rojas JC, Gallardo G, Wang K, Roh J, Robinson G, Finn MB, Jiang H, Sullivan PM, Baufeld C, Wood MW, Sutphen C, McCue L, Xiong C, Del-Aguila JL, Morris JC, Cruchaga C; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative, Fagan AM, Miller BL, Boxer AL, Seeley WW, Butovsky O, Barres BA, Paul SM, Holtz- man DM (2017) ApoE4 markedly exacerbates tau-mediated neurodegeneration in a mouse model of tauopathy. Nature 549,523–527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Lin YT, Seo J, Gao F, Feldman HM, Wen HL, Penney J, Cam HP, Gjoneska E, Raja WK, Cheng J, Rueda R, Kritskiy O, Abdurrob F, Peng Z, Milo B, Yu CJ, Elmsaouri S, Dey D, Ko T, Yankner BA, Tsai LH (2018) APOE4 causes widespread molecular and cellular alterations associated with Alzheimer’s disease phenotypes in human iPSC-derived brain cell types. Neuron 98, 1294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Craft JM, Watterson DM, Van Eldik LJ (2006) Human amyloid beta-induced neuroinflammation is an early event in neurodegeneration. Glia 53, 484–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Smith EM, Watford M (1988) Rat hepatic glutaminase: Purification and immunochemical characterization. Arch Biochem Biophys 260, 740–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Zhang H, Wu LM, Wu J (2011) Cross-talk between apolipoprotein E and cytokines. Mediators Inflamm 2011, 949072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Gao G, Zhao S, Xia X, Li C, Li C, Ji C, Sheng S, Tang Y, Zhu J, Wang Y, Huang Y, Zheng JC (2019) Glutaminase C regulates microglial activation and pro-inflammatory exosome release: Relevance to the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Front Cell Neurosci 13, 264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Liu CC, Zhao N, Fu Y, Wang N, Linares C, Tsai CW, Bu G (2017) ApoE4 accelerates early seeding of amyloid pathology. Neuron 96, 1024–1032.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Liraz O, Boehm-Cagan A, Michaelson DM (2013) ApoE4 induces Abeta42, tau, and neuronal pathology in the hippocampus of young targeted replacement apoE4 mice. Mol Neurodegener 8, 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Fuchsberger T, Martinez-Bellver S, Giraldo E, Teruel-Marti V, Lloret A, Vina J (2016) Abeta induces excitotoxicity mediated by APC/C-Cdh1 depletion that can be prevented by glutaminase inhibition promoting neuronal survival. Sci Rep 6, 31158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Dumanis SB, DiBattista AM, Miessau M, Moussa CE, Rebeck GW (2013) APOE genotype affects the pre-synaptic compartment of glutamatergic nerve terminals. J Neurochem 124, 4–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].DiBattista AM, Dumanis SB, Newman J, Rebeck GW (2016) Identification and modification of amyloidindependent phenotypes of APOE4 mice. Exp Neurol 280, 97–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Peris-Sampedro F, Basaure P, Reverte I, Cabre M, Domingo JL, Colomina MT (2015) Chronic exposure to chlorpyrifos triggered body weight increase and memory impairment depending on human apoE polymorphisms in a targeted replacement mouse model. Physiol Behav 144, 37–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Nedelcovych MT, Tenora L, Kim BH, Kelschenbach J, Chao W, Hadas E, Jancarik A, Prchalova E, Zimmermann SC, Dash RP, Gadiano AJ, Garrett C, Furtmuller G, Oh B, Brandacher G, Alt J, Majer P, Volsky DJ, Rais R, Slusher BS (2017) N-(Pivaloyloxy)alkoxy-carbonyl prodrugs of the glutamine antagonist 6-diazo-5-oxo-l-norleucine (DON) as a potential treatment for HIV associated neurocognitive disorders. J Med Chem 60, 7186–7198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Nedelcovych MT, Kim BH, Zhu X, Lovell LE, Manning AA, Kelschenbach J, Hadas E, Chao W, Prchalova E, Dash RP, Wu Y, Alt J, Thomas AG, Rais R, Kamiya A, Volsky DJ, Slusher BS (2019) Glutamine antagonist JHU083 normalizes aberrant glutamate production and cognitive deficits in the EcoHIV murine model of HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol 14, 391–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.