Abstract

Background

The global threat of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is a One Health problem impacted by antimicrobial use (AMU) for human and livestock applications. Extensive Iberian swine production is based on a more sustainable and eco-friendly management system, providing an excellent opportunity to evaluate how sustained differences in AMU impact the resistome, not only in the animals but also on the farm environment. Here, we evaluate the resistome footprint of an extensive pig farming system, maintained for decades, as compared to that of industrialized intensive pig farming by analyzing 105 fecal, environmental and slurry metagenomes from 38 farms.

Results

Our results evidence a significantly higher abundance of antimicrobial resistance genes (ARGs) on intensive farms and a link between AMU and AMR to certain antimicrobial classes. We observed differences in the resistome across sample types, with a higher richness and dispersion of ARGs within environmental samples than on those from feces or slurry. Indeed, a deeper analysis revealed that differences among the three sample types were defined by taxa-ARGs associations. Interestingly, mobilome analyses revealed that the observed AMR differences between intensive and extensive farms could be linked to differences in the abundance of mobile genetic elements (MGEs). Thus, while there were no differences in the abundance of chromosomal-associated ARGs between intensive and extensive herds, a significantly higher abundance of integrons in the environment and plasmids, regardless of the sample type, was detected on intensive farms.

Conclusions

Overall, this study shows how AMU, production system, and sample type influence, mainly through MGEs, the profile and dispersion of ARGs in pig production.

Video Abstract

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s40168-020-00941-7.

Keywords: Antimicrobial resistance, Feces, Farm environment, Mobilome, One health, Sustainable farming, Swine

Background

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is one of the largest threats to global health and food security [1, 2]. Antimicrobial use (AMU) in human medicine is an important factor, but it is also widely recognized that the use of antimicrobials in food-producing animals contributes to the burden of AMR in human health [3]. The frequent AMU to treat or prevent infections in livestock, mainly through prophylactic and metaphylactic administration in feed or water, together with the misuse of antimicrobials as growth promoters in certain countries, have facilitated the selection and spread of AMR bacteria [4–6].

The pig industry is the most extensive agricultural user of antimicrobials in the European Union [7, 8]. Monitoring of indicator and zoonotic bacteria on pig farms reveals a frequent detection of AMR [9] and the presence of certain antimicrobial resistance genes (ARGs) of critical importance, such as blaCTX-M, mecA, or mcr [10–12]. Metagenomic approaches complement traditional AMR surveillance systems by characterizing the total pool of ARGs, including those on mobile genetic elements (MGEs), in the whole microbial community [13–15].

Recent studies describing the fecal resistome in pigs have suggested a direct link between the resistome (the collection of all resistance genes in a microbiome) and AMU or the country in which the farm was located [16, 17]. Associations between animal genetics, age or diet with microbiome composition and, therefore, with its resistome, have also been uncovered [16]. So far, pig resistome studies have been performed in industrialized intensive swine herds [18, 19]. The traditional extensive system, mainly associated with the Iberian pig breed (Sus scrofa domesticus) in Spain, is defined by eco-friendly and sustainable husbandry practices, including the constrained use of antimicrobials [20], which has been maintained for decades. Thus, this extensive production system offers an ideal means to study how sustained differences in AMU have impacted the resistome of animals and the farm environment.

To address these knowledge gaps, this study uses a metagenomic approach to characterize structural, qualitative, and quantitative differences in the resistome, and its associated mobilome, from 467 pooled fecal, environmental, and slurry samples from 38 pig farms.

Results

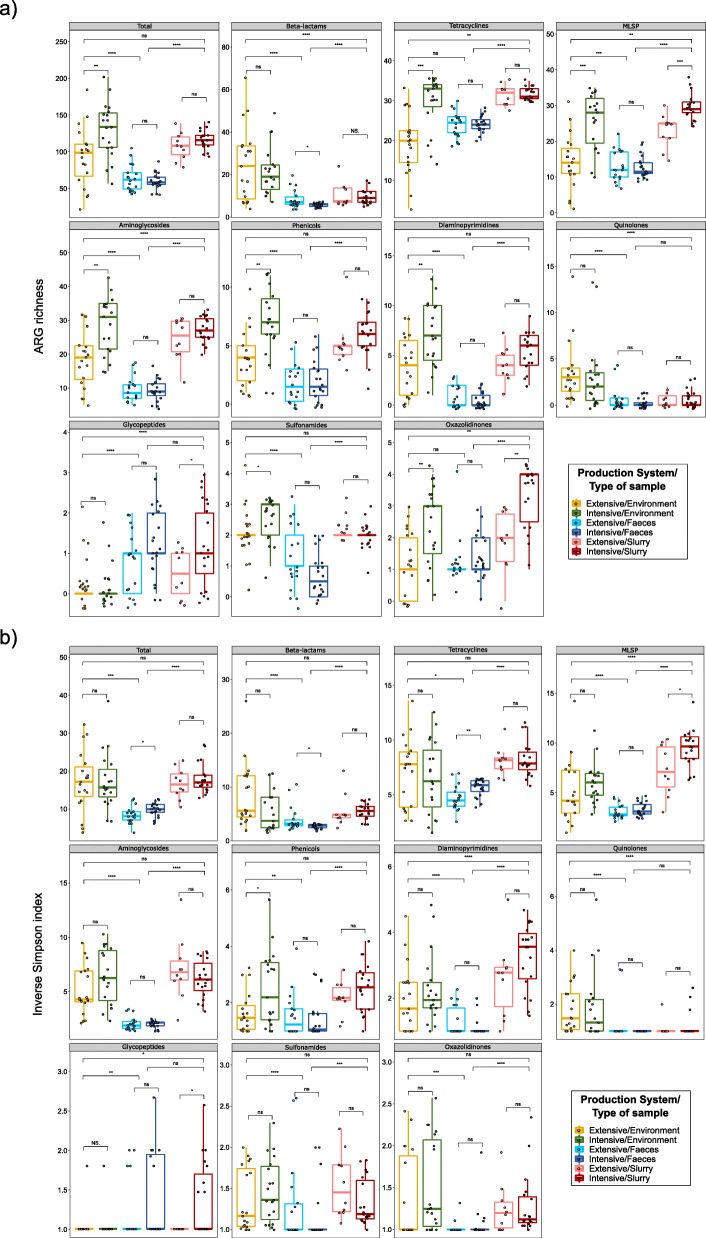

Resistome alpha diversity and richness of ARGs

One hundred five metagenomes from 467 pooled fecal, environmental, and slurry samples from 19 intensive pig farms and 19 extensive swine farms were sequenced. The average number of reads obtained per sample was 8.1 million (range 5.3 million–9.8 million). An average of 0.1% of these reads were assigned to ARGs (range 0.004–0.35%). The alpha diversity of the resistome was calculated for each sample (Fig. 1; see Additional file 1: Figure S1). Inverse Simpson and ARG richness indexes showed that the total ARGs diversity was significantly lower in feces, both from intensive and extensive farms, than in farm environments and slurry samples. A similar result was observed for almost all AMR classes, when analyzed individually (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Alpha diversity of different antimicrobial resistance (AMR) classes measured by antimicrobial resistance genes richness (ARGs) (a) and Inverse Simpson (b) indexes. These indexes were calculated from the counts per million matrix and represented as boxplots. Each sample is represented by a dot with horizontal jitter for visibility. The horizontal box lines represent the first quartile, the median, and the third quartile. Whiskers include the range of points within the 1.5 interquartile range. The differences per sample type and per production system within each sample type were evaluated with the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. n = 105 metagenomes from 38 independent farms. Nineteen metagenomes per sample type per production system were used, with the exception of extensive-slurry (n = 9). MLSP refers to the macrolides-lincosamides-streptogramins-pleuromutilins AMR class

More importantly, analyses by production system revealed a significantly higher ARG richness on the environmental samples from intensive farms than in those from extensive herds. This applied to both total ARGs (p < 0.01) and for most AMR classes (Fig. 1a). Furthermore, the Inverse Simpson index showed a significantly higher diversity for tetracycline ARGs within the fecal microbiomes from intensive farms as compared to those from extensive herds (p < 0.01) (Fig. 1b).

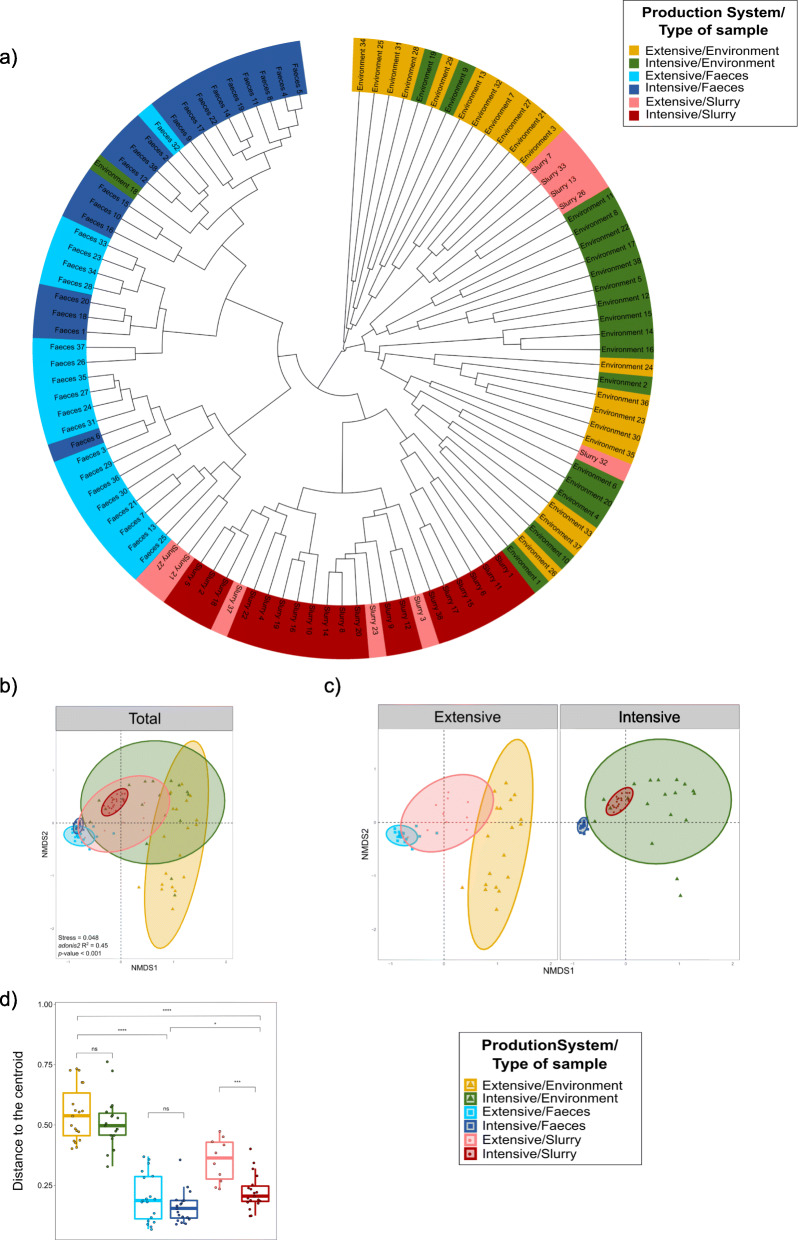

Resistome beta diversity analysis

A comparison of the beta diversity of ARGs using the Bray-Curtis dissimilarity index revealed the combined influence of sample type and production system (adonis2, p < 0.001) in the clustering and ordination of samples (Fig. 2a; Fig. 2b). However, while the type of sample explained 37.9% of the variation, the production system was of lesser importance (5.7%).

Fig. 2.

Resistome structure in samples from three sample types on intensive and extensive farms. a Dendrogram showing the complete linkage clustering of Bray-Curtis dissimilarities among intensive and extensive pig farms per sample type. b Two-dimension non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) based on Bray-Curtis dissimilarities. Subsampling was carried out by the three types of samples within each production system prior to performing ordination analysis and PERMANOVA. The centroid of each ellipse represents the group mean, and the shape was defined by the covariance within each group. c NMDS resulting from the division of the previous analysis by the two production systems to observe clearer differences. d Distance to the centroid for the evaluation of homogeneity of variances within each group. n = 105 metagenomes from 38 independent farms. Nineteen metagenomes per production system per sample type were used, with the exception of extensive-slurry (n = 9).

On intensive farms, the ordination showed that slurry samples represented a tightly clustered group of samples located within a more heterogeneous cluster of environmental samples, with fecal samples grouped closely nearby. In extensive herds, the slurry resistome was more highly dispersed, and was located between clusters representing farm environment and pig feces samples (Fig. 2c). The effect of the production system (adonis2, p < 0.001) explained 36.9% of the variation in feces, 17.8% in slurry and 8.8% in the environment. Beta dispersion varied significantly among sample types, with higher dispersion being observed in environmental samples; while between production systems there were only significant differences in the dispersal of slurry samples (p < 0.001) (Fig. 2d).

Specific ordination effects among ARGs associated with resistance to beta-lactams, tetracyclines, aminoglycosides, and macrolides-lincosamides-streptogramins-pleuromutilins (MLSP) were identified (see Additional file 2: Figure S2 and Additional file 3). We observed that ordination patterns were similar to those described for the total resistome, with a strong effect of the production system on the fecal resistome (i.e., 41.2% of the variation (adonis2, p < 0.001) in ARGs related to tetracycline resistance).

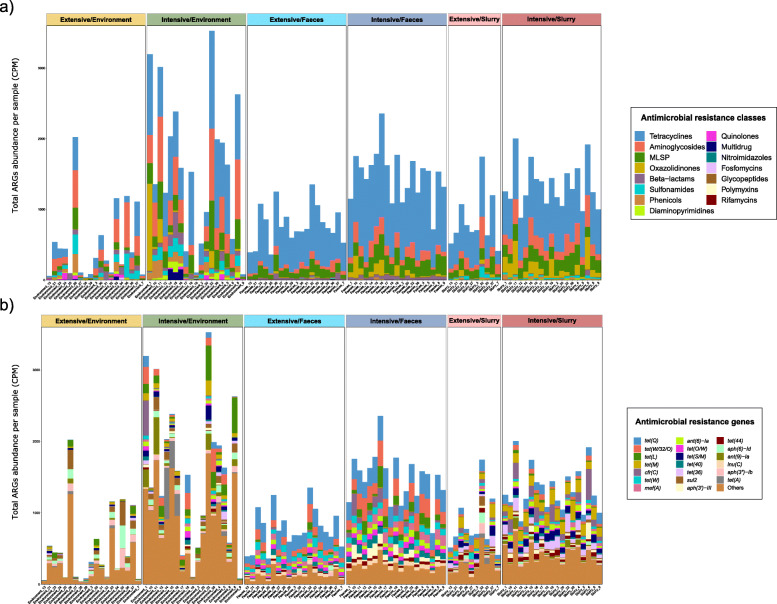

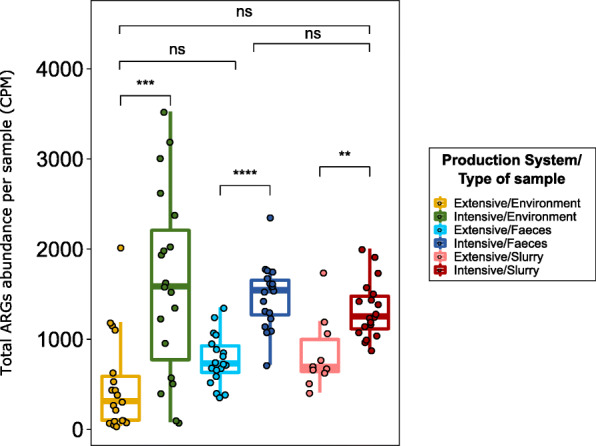

Characterization of the acquired resistome

Total ARGs abundance varied significantly (p < 0.01) by production system regardless of the sample type (Fig. 3). This was also evident when the abundance of ARGs from the aminoglycosides, MLSP, oxazolidinones, and tetracyclines AMR classes was analyzed (see Additional file 4: Figure S3). We ranked samples by ARG abundance and observed that seven intensive farm environments were among the top 10 samples, all showing over 2000 counts per million (CPM) of total ARG abundance. In contrast, ARG abundances on extensive farm environments were among the lowest observed, with seven of these samples showing under 200 CPM (Fig. 3). While ARGs linked to beta-lactam resistance were significantly more abundant (p < 0.01) in feces recovered from intensive farms than in those from extensive farms (see Additional file 4: Figure S3), their diversity was significantly lower in fecal samples from intensive farms (p < 0.05) (Fig. 1a), indicating a larger number of more homogeneous beta-lactam ARGs in feces from intensive farms.

Fig. 3.

Overview of total antimicrobial resistance genes (ARGs) abundance per sample. Boxplots of the total ARGs in counts per million per sample, stratified by production system and sample type. Each sample is represented by a dot with horizontal jitter for visibility. The horizontal box lines represent the first quartile, the median, and the third quartile. Whiskers include the range of points within the 1.5 interquartile range. The differences per sample type and per production system within each sample type were evaluated with the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. n = 105 metagenomes from 38 independent farms. Nineteen metagenomes per sample type per production system were used, with the exception of extensive-slurry (n = 9)

The abundance of ARGs linked to 15 different AMR classes was stacked to identify trends across production systems and sample types (Fig. 4a). Analyses by production system showed similar patterns of AMR class distribution for slurry and feces, but with lower ARG abundance on extensive farms, as described previously. The environmental samples showed less consistent patterns, with a higher heterogeneity of AMR classes found, both on intensive and extensive farms. The tetracycline class was predominant, particularly in feces and slurry, followed by the aminoglycosides, MLSP, and oxazolidinones classes. The sulfonamide class was significantly more abundant in slurry than in fecal samples (p < 0.001), while the opposite trend was found for the beta-lactam class (p < 0.001).

Fig. 4.

Distribution of antimicrobial resistance genes (ARGs) abundance and composition. a Stacked bar plot of total ARGs abundance per antimicrobial class (colors), per sample (x axis). b Stacked bar plot of 20 most abundant ARGs (colors), per sample (x axis); the less abundant ARGs were grouped into “Others”. n = 105 metagenomes from 38 independent farms. Nineteen metagenomes per sample type per production system were used, with the exception of extensive-slurry (n = 9). ARGs abundance was expressed as counts per million. MLSP refers to the macrolides-lincosamides-streptogramins-pleuromutilins AMR class

The 20 most abundant ARGs were represented to characterize AMR abundance at gene level (Fig. 4b). This ARG distribution was impacted by the type of sample. The tetracycline ARGs tet(Q) and tet(W/32/O) were predominant in feces (p < 0.001), while tet(M) and tet(36) were the most abundant tetracycline ARGs in slurry (p < 0.001). Again, the environmental samples showed a higher ARGs heterogenicity, especially on intensive farms. The high abundance of the oxazolidinone cfr(C) gene on samples from certain intensive farms was remarkable and was significantly less abundant among extensive herds (p < 0.001). All significant differences (p < 0.05) across production systems and sample types are shown at AMR class and ARGs level in an additional file (see Additional file 5).

Bacterial microbiome composition and its association with the resistome

To evaluate the degree to which the bacterial composition determined the resistome, Procrustes analyses were performed. We observed a significant correlation between the resistome and the bacterial microbiome composition (p < 0.001; correlation = 0.71), demonstrating that similar taxonomic compositions tended to have a similar antimicrobial resistance profile (see Additional file 6: Figure S4). Interestingly, sample type and production system impacted significantly (p < 0.001) on this association, with stronger association on intensive farms (correlation = 0.81) than in extensive herds (correlation = 0.72) and in slurry (correlation = 0.70) than environmental (correlation = 0.64) and fecal (correlation = 0.53) samples. Further details in bacterial microbiome data can be accessed in additional files (see Additional file 7: Supplementary information and Additional file 8: Figure S5).

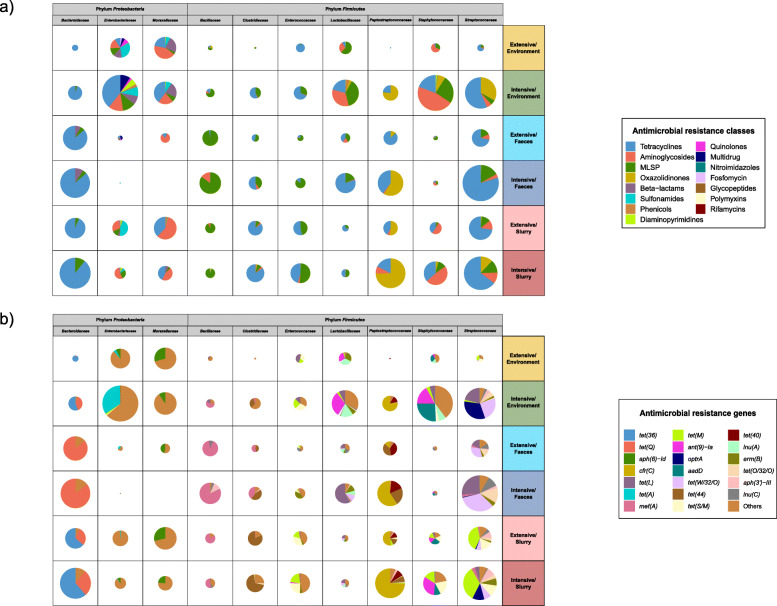

Taxonomic assignment of ARGs

Ninety-four percent of the obtained ARG-reads were assigned to ARG-containing contigs. These ARG-containing contigs were predicted to belong to 120 different bacterial families, with Streptococcaceae, Bacteriodaceae, Peptostreptococcaceae, Staphylococcaceae, Enterobacteriaceae, Moraxellaceae, Lactobacillaceae, Bacillaceae, Enterococcaceae, and Clostridiaceae accounting for 58.5% of the total ARGs abundance and 75.8% of all assigned ARGs. Most of these families were among the most abundant taxa on these farms, with exemptions such as Peptostreptococcaceae and Enterococcaceae, whose proportion in the total bacterial microbiome was much smaller. In contrast, despite their high abundance, Pseudomonadaceae, Prevotellaceae, or Flavobacteriaceae families did not contribute remarkably to the resistome composition.

We further investigated the 10 most abundant families with assigned ARGs from the main AMR classes (Fig. 5a). The distribution of AMR-encoding taxa at family level varied across and within families by production system and type of sample. Thus, in Bacteroidaceae and Streptococcaceae, ARGs from the tetracycline AMR class were predominant, while those from the MLSP and oxazolidinone AMR classes were the most abundant in Bacillaceae and Peptostreptococcaceae, respectively. The impact of the production systems (p < 0.05) on the abundance of ARGs assigned to Enterobacteriaceae, Staphylococcaceae, and Streptococcaceae was remarkable, with a higher abundance on intensive farms, particularly in environmental samples.

Fig. 5.

Taxonomical assignment of the resistome at family level. The abundance of antimicrobial resistance genes (ARGs) taxonomically assigned was expressed in counts per million, selecting the 10 most abundant taxonomical families harboring ARGs. a Pie chart distribution of total AMR abundance per antimicrobial class (colors), per taxonomical family, production system and sample type; the size of each pie chart is proportional to the ARGs abundance within each group. b Pie chart distribution of the 20 most abundant ARGs in the 10 most abundant taxonomical families harboring ARGs (colors), per taxonomical family, production system and sample type; the less abundant ARGs were grouped into “others”. n = 105 metagenomes from 38 independent farms. Nineteen metagenomes per sample type per production system were used, with the exception of extensive-slurry (n = 9). MLSP refers to the macrolides-lincosamides-streptogramins-pleuromutilins AMR class

Similar analyses by the 20 most abundant ARGs assigned to these 10 taxonomical families (Fig. 5b) revealed a gene-specific taxonomical association of tet ARGs, a result which helps to explain their heterogeneous distribution among sample types shown in Fig. 4b. More specifically, the tet(Q) gene was associated with members of the Bacteroidaceae family, particularly in feces, while other tetracycline ARGs, such as tet(L) and tet(M), were mainly linked to families belonging to the Firmicutes phylum, such as Streptococcaceae, Staphylococcaceae, Lactobacillaceae, or Enterococcaceae. The oxazolidinone ARG cfr(C) was predominantly associated with the Peptostreptococcaceae, while optr(A) was most abundant in Streptococcaceae, both showing a significantly higher abundance on intensive farms (p < 0.001). Further details of differences by production system and sample type in taxonomical assignation of ARGs, both at AMR class level and individual ARG level, are summarized in an additional file (see Additional file 9).

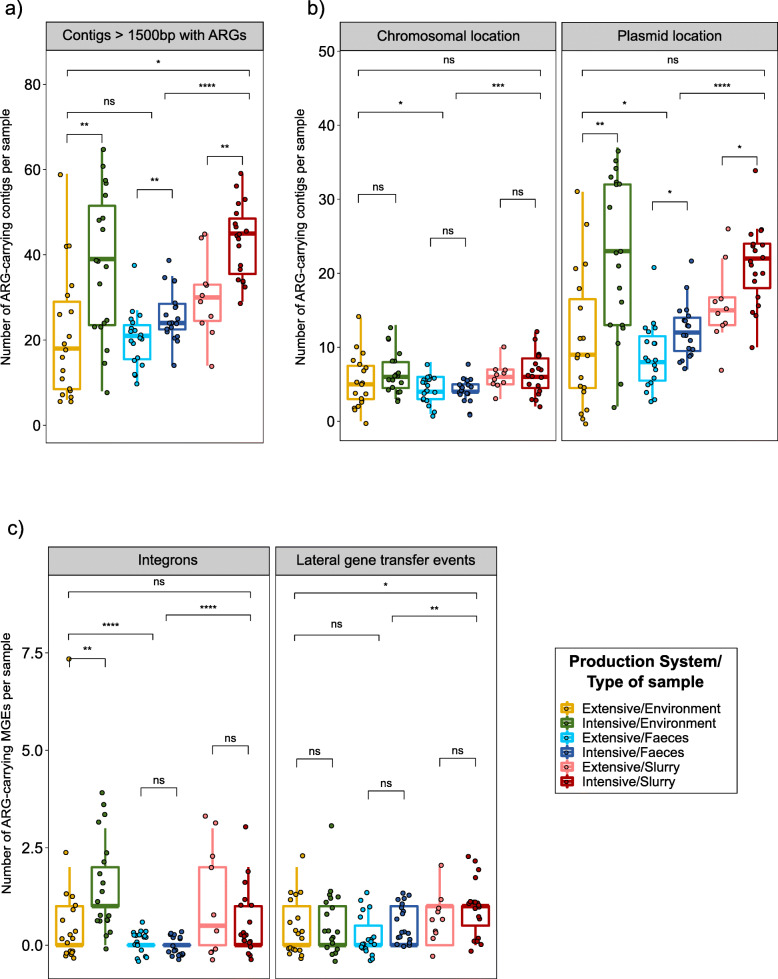

Characterization of the AMR mobilome

We evaluated the presence of ARGs on 678,111 contigs that contain MGEs in all samples after metagenomics assembly. Thereof, we identified 3130 contigs (0.5%) larger than 1500 base pairs (bp) that contained ARGs. The number of these ARG-containing contigs was significantly higher on samples from intensive farms than on those from extensive herds (p < 0.01), regardless of the sample type (Fig. 6a). These ARG-containing contigs were predicted to be mainly, but not exclusively, regions of plasmids (Fig. 6b). Notably, while a significantly higher number of ARGs were located in plasmids on samples from intensive farms (p < 0.05), no significant differences were observed between production systems in the abundance of ARGs of chromosomal location (Fig. 6b). Correlation analyses revealed a significant association (p < 0.05) between the abundance of plasmids carrying ARGs and tetracycline use (rs = 0.41) and total AMU (rs = 0.51), suggesting that the resistome is associated with AMU. This pattern was also apparent for environmental and fecal samples (rs ≥ 0.47), but not for slurry samples.

Fig. 6.

Antimicrobial resistance mobilome characterization. a Boxplot of contigs with more than 1500bp carrying antimicrobial resistance genes (ARGs). b Boxplots of chromosomal or plasmid location of ARGs containing contigs with PlasFlow. c Boxplots of integrons and lateral gene transfer events involving ARGs detected in contigs with Integron_Finder and WAAFLE, respectively. Each sample is represented by a dot with horizontal jitter for visibility. The horizontal box lines represent the first quartile, the median, and the third quartile. Whiskers include the range of points within the 1.5 interquartile range. The differences per sample type and per production system within each sample type were evaluated with the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. n = 105 metagenomes from 38 independent farms. Nineteen metagenomes per sample type per production system were used, with the exception of extensive-slurry (n = 9)

The abundance of integrons was significantly higher within environments from intensive than on extensive farms (p < 0.01), while integrons were relatively uncommon in fecal samples (Fig. 6c). A total of 68 integrons were characterized carrying 144 ARGs, which clustered in 39 different groups, 2 of which contained 23.9% of the identified integrons. The aminoglycoside ARGs aadA (representing 61.1% of the ARGs found in integrons), the trimethoprim ARGs dfrA (19.4%), or both (31.3% of the integrons) were frequently contained within these regions. Lateral gene transfer (LGT) events were significantly more frequent in slurry than in fecal or environmental samples (p < 0.05), but no differences were observed between the two production systems (Figure 6c). We detected 57 LGT events involving 59 ARGs, among which tetracycline ARGs were the most abundant (59.6% of the LGT events), with bacteria from the class Clostridia as the main donor, particularly for the tet(W/32/O) gene. ARGs linked to resistance to MLSP were detected in 21.1% of the LGT events with the Bacteroidia class being the main donor bacteria in this instance. Further information on the LGT events and integrons identified, including the ARGs involved and their clustering, are available in an additional file (see Additional file 10).

The resistome is associated with AMU

Correlation of global ARGs abundance data and total AMU revealed a significant association (p < 0.05) between AMU and the abundance of ARGs from the aminoglycoside (rs = 0.52), tetracycline (rs = 0.55), MLSP (rs = 0.58), and oxazolidinone (rs = 0.68) AMR classes (see Additional file 11: Figure S6A). Analysis on AMU from the perspective of antimicrobial class level yielded significant correlations between the abundance of ARGs from the oxazolidinone AMR class and the use of phenicols (rs = 0.45), macrolides-lincosamides-pleuromutilins (MLP) (rs = 0.60), or tetracyclines (rs = 0.45).

Similar association patterns were observed for fecal and environmental resistomes when analyzed individually (rs ≥ 0.43, see Additional file 11: Figure S6B and Figure S6C)). Indeed, the impact of AMU on the abundance of ARGs was even more marked (rs ≥ 0.58) in fecal samples. In both sample types, MLP and phenicols consumption was positively associated (rs ≥ 0.43) with the abundance of ARGs from most AMR classes. Although only a few positive correlations were observed for slurry samples, the general patterns were consistent with the results obtained for fecal and environmental samples (see Additional file 11: Figure S6D). No remarkable associations were observed for other antimicrobial classes, including the beta-lactams, despite their high use on these farms.

Discussion

The characterization of farm metagenomes provided an integral overview of differences in the resistome of animals and of the farm environment across two swine production systems. The farm resistomes were defined by a combination of three factors: production system, sample type, and antimicrobial consumption at farm level.

Extensive Iberian pig production generates high quality cured products within a particular rearing system, which includes differentiating factors such as outdoor farming in oak fields, lower animal density, and/or the compulsory slaughter at age 14 months [21], instead of at age 6–8 months in the case of pigs reared on intensive farms. This extensive approach translates to greater health and thus a lower AMU [20]. The lower ARG abundance detected in samples collected from these extensive farms, regardless of the sample type (i.e., environments, feces or slurry), is likely primarily linked to the significantly lower AMU on these farms, which is the main factor driving the rise and spread of ARGs in animal fecal microbiomes [16, 17, 22–24]. As noted, additional factors, such as feeding regime, husbandry practices, or farm environments, which have been previously suggested as having an influence on the resistome composition in cattle [25, 26], might also contribute to the differences observed in this study.

Slurry and farm environments may play an important role in the spread and on farm re-circulation of ARGs and AMR bacteria. We disclosed structural differences between the resistome of these two sample types and that of pig feces. Indeed, both slurry and environmental samples exhibited a higher ARG richness and beta dispersion when compared to the resistome of fecal samples, regardless of the AMR class and even on intensive farms, where feces and farm environments are in closer and continuous contact. This agrees with results from previous studies in cattle [27] and reflects that within farm environments there are different micro-ecosystems with a wide range of microbes, including indigenous microbiota [28], and ARGs present. In addition, the strong effect shown by sample type in the resistome was also observed for the bacterial microbiome composition, with, for instance, the dominance of Proteobacteria in environmental samples, in contrast with a more diverse taxonomy in feces and slurry, with the predominance of members of the Firmicutes phylum. These findings suggested an association between the resistome and the microbiome, which was further supported by Procrustes analyses, evidencing that changes in the environment and slurry resistomes were linked to shifts in the microbial populations dominating these niches, as it has been recently reported on pig farms [29].

Some major differences between the resistome of feces and farm environments were found, for instance, in the abundance of ARGs assigned to Enterobacteriaceae. This family, which includes bacteria of relevance for public health [30], was a sub-dominant taxa in feces due to the relatively small proportion of members of the Proteobacteria phylum in fattening pig feces [31, 32], but represented a major group in environmental samples. In the farm environment, this family, together with certain families from the Firmicutes phylum, becomes the dominant taxonomic groups carrying ARGs, probably due to their aerotolerance, which would provide them a competitive advantage over other fecal-associated strict anaerobic taxa. Thus, the resistome structure on the farm environment, regardless of the production system, was determined by the high abundance of a combination of soil-associated bacteria, such as members of the Moraxellaceae or Staphylococcaceae families, together with fecal-associated facultative anaerobic bacteria, such as Enterobacteriaceae, Streptococcocaeae, or Lactobacillaceae.

The fecal and slurry resistomes had a similar qualitative composition at AMR class level, but clear differences were observed with respect to the specific ARGs, suggesting that the composition of the bacterial community dominating each sample type shapes the associated resistome, as previously proposed [33, 34]. Through the taxonomic assignment of ARGs to bacterial families, we confirmed that such differences by sample type were linked to a differential abundance of ARG-containing taxa. For instance, the tetracycline ARG tet(Q), the most abundant gene within the most common AMR class, was almost exclusively assigned to the Bacteroidaceae family, which agrees with previous reports [35]. While this ARG was predominant in fecal Bacteroidaceae, slurry and, to a lesser extent, environmental Bacteroidaceae frequently carried also the tet(36) ARG.

We also found that the oxazolidinone-resistance genes cfr(C) and optrA were mainly associated with members of the Peptostreptococcaceae and Streptococcacae families, respectively. This agrees with previous studies describing that the cfr(C) gene was mainly confined to Clostridioides difficile [36, 37], and that the optrA gene was previously described in Streptococcus of swine origin [38–40]. In our study, both genes were mainly identified in samples from intensive herds and were associated with high consumption of phenicols and MLP at farm level. Despite the fact that oxazolidinones are not currently used in food-producing animals [41], these two ARGs confer resistance to other antimicrobial families which have been widely used on swine farms, such as phenicols in cfr(C), and phenicols, lincosamides, pleuromutilins, and streptogramins A in optrA [42]. Altogether, these facts demonstrate that the cross-selection for AMR to last resort antimicrobials can occur on swine farms.

In our study, the most consistent associations between abundance of ARGs and AMU were observed for ARGs from the tetracyclines or MLSP AMR classes with the application of antimicrobials from these respective groups, which are frequently administered during the fattening period, in agreement with a recent study carried out by Van Gompel et al. [43]. Although we did not collect AMU data corresponding to the early stages of production, this previous study reported the absence of an association between AMU during these early stages and the resistome at the end of the fattening period. Interestingly, despite beta-lactams were one of the most frequently used antimicrobials on these farms, particularly in intensive herds, its use was not significantly associated with the abundance of ARGs. When compared to other antimicrobial classes which exhibited positive resistome-AMU correlations, we observed lower abundance of beta-lactam ARGs in MGEs. Further research is needed to establish the possible link between short-term AMU data and AMR spread through MGEs depicted in this study. Furthermore, associations observed between AMU and resistance to antimicrobials of different AMR classes suggests that ARGs are selected and enriched in the absence of exposure to the AMR class they confer resistance to. This arises through their co-selection due to the use of other antimicrobials or the enrichment of certain components of the microbiome [14].

MGEs promote the mobilization and dissemination of ARGs in bacterial communities [44–46]. A large proportion of the resistome in the present study was not only associated with MGEs, and mainly with plasmids, but also with integrons. The majority of integrons that contained ARGs carried the aminoglycoside aadA and trimethoprim dfrA ARGs, a phenomenon that was highlighted in previous surveys conducted on zoonotic and indicator bacteria on Spanish swine farms [47, 48]. Remarkably, plasmid-associated ARGs were predominantly found on intensive farms and linked to a high tetracycline consumption and total AMU. Integrons were also more abundant in samples from intensive farm environments, with a potential association with members of the Enterobacteriaceae family [49]. Altogether, these results demonstrate that the significant differences in ARG abundance observed between intensive and extensive production systems were mainly associated with a higher abundance of MGEs on intensive farms, probably favored by a higher AMU. The high abundance of ARGs and MGEs-associated ARGs on farm environments and slurry evidences the risk of their transmission and spread.

The metagenomic approach followed in our study could be adopted to characterize the resistome in food-producing animals in future AMR surveillance schemes through an integral analysis of the whole microbial community [50]. Using a combination of read-mapping techniques and metagenomic assembly pipelines, we could observe the actual association existing between the microbiome, mobilome, and resistome of pig farms. However, the sequencing depth can represent a limiting factor, and low abundant genes could be easily underreported [51]. Besides, the presence of particular ARGs does not necessarily mean that they will be expressed, and, therefore, discrepancies could occur with the results of phenotypic susceptibility testing. That is why Forslund et al. [24] introduced the concept “antibiotic-resistance potential”, to account for differences in gene expression and regulation that could affect phenotypic resistance.

Conclusions

To the best of our knowledge, the current study provides the first integral analysis of the resistome on swine farms that compares two different production systems, extensive and intensive, exploring the animals, the farm environments, and slurry. A higher ARG abundance was observed in samples recovered from intensive swine farms, with higher AMU, relative to those from extensive herds. A differential distribution of ARGs was also observed among different types of samples, likely due to the dominance of different bacterial taxa in different sample types, as clearly shown by the distribution of tetracycline ARGs. Finally, the majority of identified ARGs were located on plasmids and differences in ARGs abundance among production systems were linked to a higher abundance of plasmids on intensive farms, highlighting the importance of the mobilome in the spread of ARGs on swine farms. Overall, these results show that sustainable farming practices can help reduce AMR pressure in the food chain.

Methods

Farms selection and sample collection

The final number of farms included in the study was 38, distributed all over Spain (see Additional file 12: Figure S7). These farms were divided into intensive (19 herds) and extensive (19 herds) farms based on their production system. Farm and sampling characteristics, including sampling season, and antimicrobial consumption of each farm are included in an additional table (see Additional file 13). Sampling was carried out between 2017 and 2018 in feedlots with pigs between 6 and 8 months old. No antimicrobial treatment was administered in the immediate month prior to the sampling.

On each farm, feces, environmental swabs, and slurry were collected. Five fresh fecal samples were obtained from the rectum of fattening pigs. Five samples were swabbed in the environment of the fattening unit (feeders, drinkers, floors, walls, and windows) using swabs soaked in phosphate buffer saline (PBS) 1×. On those farms with slurry pits, three samples were collected from different points of the pit. Nine extensive farms did not provide slurry samples due to the lack of slurry pits in their facilities. The samplings were carried out by trained veterinarians and the samples were sent to our laboratory under cooling conditions (2–8 °C) in less than 24 h.

Antimicrobial use (AMU)

The veterinary practitioner responsible for each farm recorded the antimicrobial consumption of the pigs of the fattening unit sampled over the immediate 4-month period prior to sampling. AMU was categorized into 10 classes: (i) total, (ii) aminoglycosides, (iii) beta-lactams, (iv) diaminopyrimidines, (v) MLP, (vi) phenicols, (vii) polymyxins, (viii) quinolones, (ix) sulfonamides, and (x) tetracyclines. For each antimicrobial class, consumption per farm was expressed in annual mg/PCU, following the European Surveillance of Veterinary Antimicrobial Consumption (ESVAC) protocol [52].

Sample processing, DNA extraction, library preparation, and sequencing

From each farm, a single DNA sample was obtained from fecal, environmental and, if available, slurry samples. A total of 105 DNA samples were sequenced from these 38 independent herds, including three DNA extraction negative controls. The samples were divided into environment (38), feces (38), and slurry (29). Prior to DNA extraction, fecal samples from each farm were pooled by stirring thoroughly with a sterile tongue depressor using 3 g per individual sample, obtaining a final composite sample of 15 g. After its homogenization, 2 g were soaked in 18 ml of PBS 1× and vigorously mixed for 5 min using a Stomacher Laboratory Blender (Seward, Worthing, UK). For the environmental and slurry samples, 2 ml were recovered from each individual sample and added to a 15-ml sterile Falcon tube (BD, Erembodegem, Belgium), obtaining a final volume of 10 ml and 6 ml, respectively. These tubes were centrifuged at 4500×g for 10 min at 4 °C, discharging the supernatant. Sample handling was performed on ice.

DNA was extracted using the Stool DNA Purification Kit (EURX, Gdańsk, Poland) following the manufacturer’s instructions with minor modifications. As starting material for DNA extractions, 500 μl were used for the three different samples. The final DNA was eluted in 200 μl of 10 mM Tris HCl buffer (pH 8) after its incubation for 5 min for maximum elution efficiency and stored at – 80 °C until its use. Negative controls were prepared with 500 μl of sterile distilled water as starting material and included in DNA extraction batches to confirm that no contamination occurred in the samples during DNA extraction and sequencing.

Prior to sequencing, a Qubit High Sensitivity DNA assay (BioSciences, Dublin, Ireland) was used to determine the total DNA concentration, being its purity assessed by the 260/280 and 260/230 absorbance ratios using a spectrophotometer NanoDrop ND-1000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Wilmintong, Delaware). Paired-end sequencing libraries were prepared from the extracted DNA using the Illumina Nextera XTLibrary Preparation Kit (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) followed by sequencing on the Illumina NextSeq 500, with a NextSeq 500/550 High Output Reagent kit v2 (300 cycles), in accordance with the standard Illumina sequencing protocols.

Reads quality filtering

Pre-processing of raw reads by sequence quality and length was performed with PRINSEQ-Lite v0.20.4 [53]. A mean quality lower than Q25 in a 10 base pair sliding window was the criteria utilized for trimming low quality reads at the 3′-end. Moreover, a minimum length of 150 base pairs was ensured for all reads. The Illumina sequences clean were screened against the pig reference genome (Sus scrofa UCSC) downloaded from Illumina iGenomes (https://support.illumina.com/sequencing/sequencing_software/igenome.html, 2019) to remove host reads using BMTagger v3.101 (ftp://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pub/agarwala/bmtagger/, 2011). Read duplicates were removed using the Picard MarkDuplicates tool v2.18.1 (https://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/, 2016) to create fastq files with unique reads only. Afterwards, reads were subjected to a further quality filtering step. In brief, sequences were trimmed for low quality score using a modified version of the script trimBWAstyle.pl that works directly from BAM files (TrimBWAstyle.usingBam.pl, 2010; https://github.com/genome/genome/blob/master/lib/perl/Genome/Site/TGI/Hmp/HmpSraProcess/trimBWAstyle.usingBam.pl). The script was used to trim off bases with a quality value of 3 or lower. This threshold was chosen to delete all the bases with an uncertain quality as defined by Illumina’s EAMMS (End Anchored Max Scoring Segments) filter. Additionally, reads trimmed to less than 200bp were also removed.

Assembly into contigs and taxonomic annotation of reads and contigs

Filtered reads were assembled using IDBA_UD v1.1.3 (kmers 20–120) [54], keeping those contigs with length above 500 bp. Contigs and filtered reads were taxonomically assigned by using Kraken2 software v2.0.8-beta [55] and kraken2-microbial database (2018-09-03) (https://lomanlab.github.io/mockcommunity/mc_databases.html). Only those taxa belonging to the kingdom Bacteria were used for further analyses. The same procedure and database were employed for the taxonomical assignment of both reads and contigs in order to avoid biases caused by the use of different approaches. The relative abundance matrix of filtered reads at family level was used for bacterial microbiome characterization analyses.

ARGs annotation

Reads from each sample were mapped against the ResFinder database (2019-08-28) [56] using Bowtie2 v2.3.4.1 [57, 58]. The “.trimmed_pairs” fastq files generated by Bowtie2 were transformed into a fasta file where forward and reverse reads were concatenated. This new fasta file was employed to perform a BLAST v2.6.0 [59] against the ResFinder database [56] using a 70% identity cut-off and taking 100 hits (max_target_seqs) in order to avoid problems associated to BLAST use in local [60]. Only the first hit per sequence was kept for further analyses.

The document “phenotypes.txt” was downloaded from the ResFinder repository (2019-10-01) (https://bitbucket.org/genomicepidemiology/resfinder_db/src/master/) and manually curated in order to modify the “class” variable, gathering genes that confer resistance to macrolides, lincosamides, streptogramins, and pleuromutilins into the MLSP class, and those that confer resistance to oxazolidinones, as the oxazolidinone class. This last group included cfr genes, which confer resistance to phenicols, lincosamides, oxazolidinones, pleuromutilins and streptogramins A, the optrA gene, which confers resistance to phenicols and oxazolidinones, and the poxtA gene, which confers resistance to phenicols, oxazolidinones, and tetracyclines.

The manually curated version of phenotypes.txt file (see Additional file 14) was used to create two different matrices from BLASTn-firsthit file: (a) gene abundance, (b) antimicrobial resistance class abundance. Abundance matrices were transformed to CPM matrices, defined as a normalization which consists of scaling the counts by the total number of filtered reads, for further analyses.

Taxonomical assignment of ARGs

The “.trimmed_pairs” fastq files generated by mapping the reads on the ResFinder database [56] by Bowtie2 [57, 58] were re-mapped against contigs using the same approach, in order to know which ARG-read belonged to each contig.

Taxonomic assignment for each contig was exported to the contained ARG-read, prior to the final quantification of ARG gene and AMR class per taxonomic group at family level. Abundance matrices were transformed to CPM matrices for further analyses.

AMR mobilome characterization

BLASTn comparison [59] against the ResFinder database [56] was carried out for contigs longer than 1500bp, keeping only those contigs containing ARG for their mobilome analysis. Plasmid location was predicted by PlasFlow v1.1 [61], LGT events were detected by WAAFLE (https://huttenhower.sph.harvard.edu/waafle) and integrons were predicted by Integron_Finder v2 [62], using the assembled contig files as query files.

The coding sequences (CDS) within LGT events and integron regions were extracted by using their coordinates in the contig from WAAFLE and Integron_Finder output files, and bedtools utilities v2.29.0 (https://bedtools.readthedocs.io/en/latest/) to extract this CDS fasta files from contig fasta files. CDS fasta files were used for BLASTn comparison [59] against the ResFinder database [56] to determine which LGT events and integrons contained ARGs. Additionally, complete integron sequences were extracted from contig fasta files and clustered using VSEARCH v2.7.1 [63] with “--cluster_fast” option, to evaluate which integrons were shared between samples.

An in-house ruby script was developed to summarize AMR mobilome outputs in a contig-count per sample matrix, gathering ARGs with chromosomal, plasmid or unknown location, together with LGT events and integron location data. ARGs with unknown location were excluded from further mobilome analyses.

Statistical analyses and figures visualization

Along the study, analyses were carried out initially for the whole sample collection and later among the two production systems (extensive and intensive) and the three different sample types (environment, feces, and slurry), individually and nested. Besides, the analyses were split into the 16 antimicrobial classes provided by the curated ResFinder database: (i) total, (ii) aminoglycosides, (iii) beta-lactams, (iv) diaminopyrimidines, (v) fosfomycin, (vi) glycopeptides, (vii) MLSP, (viii) multidrug, (ix) nitroimidazoles, (x) phenicols, (xi) oxazolidinones, (xii) polymyxins, (xiii) quinolones, (xiv) rifamycins, (xv) sulfonamides, and (xvi) tetracyclines. All analyses were carried out using R v3.6.2 [64].

The within-herd resistome diversity was computed at the gene-level CPM matrix using the R package vegan v2.5.6 [65]. Alpha diversity was estimated by the Inverse Simpson Diversity (1/D), Simpson (1-D), Shannon and ARGs richness indexes. Comparisons in alpha diversity estimates were carried out with the Wilcoxon signed-rank test through the ggpubr package v0.4.0 [66]. Beta diversity was estimated by Bray-Curtis dissimilarities and analyzed by non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) using the “metaMDS” function in vegan. Within-group dispersion was evaluated through the “betadisper” function. Finally, the effect of the type of sample and the production system on sample dissimilarities was determined by permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) using distance matrices with “adonis2” function (pairwise adonis). These analyses were also computed for bacterial microbiome characterization at the family-level relative abundance matrix.

Associations among the variables under study (production system and sample type) with the CPM matrices for ARGs and AMR classes, as those taxonomically assigned, the contig-counts matrix for AMR mobilome and the relative abundance matrix for microbiome characterization, were performed with the Kruskal Wallis test and the post hoc Wilcoxon signed-rank test. All p values were adjusted by following the Benjamini and Hochberg method [67] and significance was established at p < 0.05.

Procrustes analyses were used to determine the association between the resistome and the bacterial microbiome composition. Bray-Curtis dissimilarities from each matrix were ordinated using NMDS. The symmetric Procrustes correlation coefficients between the resistome and the microbiome ordinations, p values and plots were obtained using the “protest” function in vegan.

As AMU data were strongly skewed, they were log10 transformed. In addition, a pseudocount of 1 was added before the log10 transformation to deal with an excess of zeros in the data [43]. To reveal the association between AMU and AMR, as the link between AMU and AMR mobilome, the pairwise Spearman’s rank correlation was calculated for CPM matrices for AMR classes and the contig-count AMR mobilome matrix, respectively. Correlations were removed if the Spearman correlation coefficient, rs, was lower than 0.4 and the p value > 0.05, adjusting this p value to avoid false positives using the Benjamini and Hochberg method [67]. The correlations were carried out with the R package Hmisc v4.4.0 [68].

The circular Bray-Curtis resistome dendrogram was constructed by exporting the dendrogram in Newick format using the R package ape v5.4 [69] and further annotating it using the Interactive Tree of Life tool (https://itol.embl.de/). Other plots were produced using the ggplot2 package v3.3.2 [70], and further modified using the software Inkscape v0.92.4 (https://inkscape.org/). The level of statistical significance was represented with asterisks: four asterisks (****) indicated a p value less than 0.0001; three asterisks (***) indicated a p value between 0.0001 and 0.001; two asterisks (**) indicated a p value between 0.001 and 0.01; one asterisk (*) indicated a p-value between 0.01 and 0.05; non-significance (ns) indicated a p value higher than 0.05.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Figure S1. Alpha diversity of different antimicrobial resistance (AMR) classes measured by A) Simpson and B) Shannon indexes. These indexes were calculated from the counts per million matrix and represented as boxplots. Each sample is represented by a dot with horizontal jitter for visibility. The horizontal box lines represent the first quartile, the median, and the third quartile. Whiskers include the range of points within the 1.5 interquartile range. The differences per sample type and per production system within each sample type were evaluated with the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. n = 105 metagenomes from 38 independent farms. Nineteen metagenomes per sample type per production system were used, with the exception of extensive-slurry (n = 9). MLSP refers to the macrolides-lincosamides-streptogramins-pleuromutilins AMR class.

Additional file 2: Figure S2. Resistome variation among different types of production system and samples at antimicrobial resistance (AMR) class level. Two-dimension non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) based on Bray-Curtis dissimilarities was calculated for A) Beta-lactams, B) Tetracyclines, C) MLSP and D) Aminoglycosides. Subsampling was carried out by the three types of samples within each production system prior to performing ordination analysis and PERMANOVA. The centroid of each ellipse represents the group mean, and the shape was defined by the covariance within each group. Each NMDS was divided by the two production systems to observe clearer differences. n = 105 metagenomes from 38 independent farms. Nineteen metagenomes per production system per sample type were used, with the exception of extensive-slurry (n = 9). MLSP refers to the macrolides-lincosamides-streptogramins-pleuromutilins AMR class.

Additional file 3: Table S1. Resistome variation among different production systems and samples at AMR class level.

Additional file 4: Figure S3. Overview of antimicrobial resistance genes (ARGs) abundance within antimicrobial resistance (AMR) classes per sample. Boxplots of the ARGs in counts per million within each AMR class per sample, were stratified by production system and sample type. Each sample is represented by a dot with horizontal jitter for visibility. The horizontal box lines represent the first quartile, the median, and the third quartile. Whiskers include the range of points within the 1.5 interquartile range. The differences per sample type and per production system within each sample type were evaluated with the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. n = 105 metagenomes from 38 independent farms. Nineteen metagenomes per production system per sample type were used, with the exception of extensive-slurry (n = 9). MLSP refers to the macrolides-lincosamides-streptogramins-pleuromutilins AMR class.

Additional file 5: Tables S2-S11. Significant associations at antimicrobial resistance class and antimicrobial resistance genes level (p < 0.05) across production systems and sample types.

Additional file 6: Figure S4. Association between the resistome and the bacterial microbiome composition. A) Correlation between antimicrobial resistance genes and bacterial abundance at family level using Procrustes analyses. The lines show the Procrustes residuals; the change in the ordination position when using the resistome (dotted ends) compared to the bacterial microbiome (non-dotted ends) is displayed. The correlation coefficient and significance were determined using the “protest” function in R package vegan. B) Residual error plot for Procrustes residual size comparison showing the difference in the resistome-microbiome association across production systems and sample types. Horizontal lines denote the median (solid), 25% and 75% quantiles (dashed). n = 105 metagenomes from 38 independent farms. Nineteen metagenomes per production system per sample type were used, with the exception of extensive-slurry (n = 9).

Additional file 7:. Supplementary information. Supplementary text with additional information.

Additional file 8: Figure S5. Bacterial microbiome composition at family level. A) Alpha diversity of bacterial composition measured by family richness, Inverse Simpson, Shannon and Simpson indexes. These indexes were calculated from the relative abundance matrix and represented as boxplots. Each sample is represented by a dot with horizontal jitter for visibility. The horizontal box lines represent the first quartile, the median, and the third quartile. Whiskers include the range of points within the 1.5 interquartile range. The differences per sample type and per production system within each sample type were evaluated with the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. B) Two-dimension non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) based on Bray-Curtis dissimilarities. Subsampling was carried out by the three types of samples within each production system prior to performing ordination analysis and PERMANOVA. The centroid of each ellipse represents the group mean, and the shape was defined by the covariance within each group. C) Stacked bar plot of the relative abundance of the 20 most abundant bacterial families (colors), per sample (x axis); the less abundant families were grouped into “Others”. n = 105 metagenomes from 38 independent farms. Nineteen metagenomes per production system per sample type were used, with the exception of extensive-slurry (n = 9).

Additional file 9: Tables S12-S26. Significant associations at antimicrobial resistance class and antimicrobial resistance genes (ARGs) level (p < 0.05) across production systems and sample types in taxonomically assigned ARGs.

Additional file 10: Tables S27-S28. Summary of integrons and lateral gene transfer events detected on contigs with more than 1,500bp.

Additional file 11: Figure S6. Association between antimicrobial use (AMU) and antimicrobial resistance (AMR). To reveal the association between AMU and AMR, the pairwise Spearman’s rank correlation was calculated for the counts per million matrices at AMR class level. These correlations were carried out for A) all the samples, B) environmental samples, C) faecal samples and D) slurry samples. Correlations were removed if the Spearman correlation coefficient, rs, was lower than 0.4 and the p-value > 0.05, adjusting this p-value to avoid false positives using the Benjamini & Hochberg method. n = 105 metagenomes from 38 independent farms. Nineteen metagenomes per sample type per production system were used, with the exception of extensive-slurry (n = 9). MLSP refers to the macrolides-lincosamides-streptogramins-pleuromutilins AMR class. MLP refers to macrolides-lincosamides-pleuromutilins.

Additional file 12: Figure S7. Distribution of the 38 Spanish pig farms sampled throughout Spain grouped by their production system into intensive and extensive.

Additional file 13: Table S29. Characteristics of 38 independent Spanish pig farms included in the study.

Additional file 14: Table S30. Manually curated "phenotypes.txt" from the ResFinder repository.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the excellent technical assistance provided by Diana Molina and the contribution in some parts of the research by Sandra González from Aquilón CyL S.L, as well as the help provided by Laura Finnegan in the sequencing library preparation. We would like to thank also the veterinary practitioners and farmers willingness, and in particular Álvaro Fernández-Blanco for his support on contacting the farms.

Abbreviations

- AMR

Antimicrobial resistance

- AMU

Antimicrobial use

- ARG

Antimicrobial resistance gene

- CDS

Coding sequences

- CPM

Counts per million

- LGT

Lateral gene transfer

- MGE

Mobile genetic element

- MLSP

Macrolides-lincosamides-streptogramins-pleuromutilins

- MLP

Macrolides-lincosamides-pleuromutilins

- NMDS

Non-metric multidimensional scaling

- PERMANOVA

Permutational multivariate analysis of variance

Authors’ contributions

Study design was performed by AC, PR, and AAO. Sample preparation was performed by OMA, MGG, and HP. OMA and FC performed the metagenomic sequencing. RCR and JFCD performed the computational analyses. Statistical analyses were performed by OMA with contribution from RCR and JFCD. PC, HA, and AAO provided technical and scientific support on the analysis. OMA, HA, AC, AAO, and PC participated in the manuscript writing or contributed to its revision. All authors revised the manuscript and approved the final version.

Funding

Oscar Mencía-Ares and Héctor Puente hold a grant from the Spanish Government (Ministerio de Educación y Formación Profesional) FPU 16/03485 and FPU 17/00466. Manuel Gómez-García hold a grant from Junta de Castilla y León co-financed by the European Social Fund (LE131-18). Hector Argüello is financially supported by the “Beatriz Galindo” Programme from the Spanish Government (Ministerio de Educación y Formación Profesional) BEAGAL-18-106. Research in the laboratory of Avelino Alvarez-Ordóñez is funded by the European Commission under European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under grant agreement no. 818368 and the Ministry of Science and Innovation of the Spanish Government (AGL2016-78085-P).

Availability of data and materials

DNA sequences from the 105 metagenomic samples from 38 herds and 3 DNA extraction controls are publicly available at the Sequence Read Archive database—NCBI (PRJNA628671).

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . Antibiotic resistance. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 2.EMA, EFSA EMA and EFSA Joint Scientific Opinion on measures to reduce the need to use antimicrobial agents in animal husbandry in the European Union, and the resulting impacts on food safety (RONAFA) EFSA J. 2017;15:1–245. doi: 10.2903/j.efsa.2017.4666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoelzer K, Wong N, Thomas J, Talkington K, Jungman E, Coukell A. Antimicrobial drug use in food-producing animals and associated human health risks: What, and how strong, is the evidence? BMC Vet Res. 2017;13:1–38. doi: 10.1186/s12917-017-1131-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aarestrup FM, Seyfarth AM, Emborg HD, Pedersen K, Hendriksen RS, Bager F. Effect of abolishment of the use of antimicrobial agents for growth promotion on occurrence of antimicrobial resistance in fecal enterococci from food animals in Denmark. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001;45:2054–2059. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.7.2054-2059.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wegener HC. Antibiotics in animal feed and their role in resistance development. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2003;6:439–445. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2003.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosengren LB, Waldner CL, Reid-Smith RJ, Dowling PM, Harding JCS. Associations between feed and water antimicrobial use in farrow-to-finish swine herds and antimicrobial resistance of fecal Escherichia coli from grow-finish pigs. Microb Drug Resist. 2007;13:261–269. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2007.781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.UK-VARSS. UK Veterinary Antibiotic Resistance and Sales Surveillance Report (UK-VARSS 2018), vol. 2019. New Haw, Addlestone. https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/veterinary-antimicrobial-resistance-and-sales-surveillance. Accessed 29 Apr 2020.

- 8.AEMPS . Informe JIACRA España. Primer análisis del integrado del consumo de antibióticos y su relación con la aparición de resistencia. Madrid. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 9.EFSA, ECDC The European Union summary report on antimicrobial resistance in zoonotic and indicator bacteria from humans, animals and food in 2017. EFSA J. 2019;17:1–278. doi: 10.2903/j.efsa.2019.5598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fournier C, Aires-de-Sousa M, Nordmann P, Poirel L. Occurrence of CTX-M-15 and MCR-1-producing Enterobacterales in pigs in Portugal: Evidence of direct links with antibiotic selective pressure. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020;55:105802. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2019.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lucas P, Jouy E, Le Devendec L, de Boisséson C, Perrin-Guyomard A, Jové T, et al. Characterization of plasmids harboring blaCTX-M genes in Escherichia coli from French pigs. Vet Microbiol. 2018;224:100–106. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2018.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fischer J, Hille K, Ruddat I, Mellmann A, Köck R, Kreienbrock L. Simultaneous occurrence of MRSA and ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae on pig farms and in nasal and stool samples from farmers. Vet Microbiol. 2017;200:107–113. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2016.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.He LY, He LK, Liu YS, Zhang M, Zhao JL, Zhang QQ, et al. Microbial diversity and antibiotic resistome in swine farm environments. Sci Total Environ. 2019;685:197–207. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.05.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rovira P, McAllister T, Lakin SM, Cook SR, Doster E, Noyes NR, et al. Characterization of the microbial resistome in conventional and “Raised Without Antibiotics” beef and dairy production systems. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:1980. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martínez JL, Coque TM, Lanza VF, de la Cruz F, Baquero F. Genomic and metagenomic technologies to explore the antibiotic resistance mobilome. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2017;1388:26–41. doi: 10.1111/nyas.13282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xiao L, Estellé J, Kiilerich P, Ramayo-Caldas Y, Xia Z, Feng Q, et al. A reference gene catalogue of the pig gut microbiome. Nat Microbiol. 2016;1:16161. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Munk P, Knudsen BE, Lukjacenko O, Duarte ASR, Van Gompel L, Luiken REC, et al. Abundance and diversity of the faecal resistome in slaughter pigs and broilers in nine European countries. Nat Microbiol. 2018;3:898–908. doi: 10.1038/s41564-018-0192-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Joyce A, McCarthy CGP, Murphy S, Walsh F. Antibiotic resistomes of healthy pig faecal metagenomes. Microb Genomics. 2019;5. 10.1099/mgen.0.000272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Wang C, Li P, Yan Q, Chen L, Li T, Zhang W, et al. Characterization of the pig gut microbiome and antibiotic resistome in industrialized feedlots in China. mSystems. 2019;4:206–2019. doi: 10.1128/msystems.00206-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Briyne N. Possible measures to reduce antimicrobial use in animals: a veterinary perspective: Federation of Veterinarias of Europe; 2016. https://www.aemps.gob.es/laAEMPS/eventos/AEMPS/2016/docs/J-dia-europeo-uso-prudente-antibioticos-2016/4-Jornada-antibioticos-N-Briyne.pdf?x53593.

- 21.Ministerio de Agricultura Alimentación y Medio Ambiente . Real Decreto 4/2014, de 10 de enero, por el que se aprueba la norma de calidad para la carne, el jamón, la paleta y la caña de lomo ibérico. BOE. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gerzova L, Babak V, Sedlar K, Faldynova M, Videnska P, Cejkova D, et al. Characterization of antibiotic resistance gene abundance and microbiota composition in feces of organic and conventional pigs from four EU countries. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0132892. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0132892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ghanbari M, Klose V, Crispie F, Cotter PD. The dynamics of the antibiotic resistome in the feces of freshly weaned pigs following therapeutic administration of oxytetracycline. Sci Rep. 2019;9:1–11. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-40496-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Forslund K, Sunagawa S, Kultima JR, Mende DR, Arumugam M, Typas A, et al. Country-specific antibiotic use practices impact the human gut resistome. Genome Res. 2013;23:1163–1169. doi: 10.1101/gr.155465.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Auffret MD, Dewhurst RJ, Duthie CA, Rooke JA, John Wallace R, Freeman TC, et al. The rumen microbiome as a reservoir of antimicrobial resistance and pathogenicity genes is directly affected by diet in beef cattle. Microbiome. 2017;5:159. doi: 10.1186/s40168-017-0378-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Doster E, Rovira P, Noyes NR, Burgess BA, Yang X, Weinroth MD, et al. Investigating effects of tulathromycin metaphylaxis on the fecal resistome and microbiome of commercial feedlot cattle early in the feeding period. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:1715. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Noyes NR, Yang X, Linke LM, Magnuson RJ, Cook SR, Zaheer R, et al. Characterization of the resistome in manure, soil and wastewater from dairy and beef production systems. Sci Rep. 2016;6:1–12. doi: 10.1038/srep24645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhu YG, Zhao Y, Zhu D, Gillings M, Penuelas J, Ok YS, et al. Soil biota, antimicrobial resistance and planetary health. Environ Int. 2019;131:105059. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2019.105059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luiken REC, Van Gompel L, Bossers A, Munk P, Joosten P, Hansen RB, et al. Farm dust resistomes and bacterial microbiomes in European poultry and pig farms. Environ Int. 2020;143:105971. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2020.105971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smet A, Martel A, Persoons D, Dewulf J, Heyndrickx M, Herman L, et al. Broad-spectrum β-lactamases among Enterobacteriaceae of animal origin: Molecular aspects, mobility and impact on public health. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2010;34:295–316. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2009.00198.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang X, Tsai T, Deng F, Wei X, Chai J, Knapp J, et al. Longitudinal investigation of the swine gut microbiome from birth to market reveals stage and growth performance associated bacteria. Microbiome. 2019;7:109. doi: 10.1186/s40168-019-0721-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Crespo-Piazuelo D, Estellé J, Revilla M, Criado-Mesas L, Ramayo-Caldas Y, Óvilo C, et al. Characterization of bacterial microbiota compositions along the intestinal tract in pigs and their interactions and functions. Sci Rep. 2018;8:1–12. doi: 10.1186/s40168-019-0721-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Forsberg KJ, Patel S, Gibson MK, Lauber CL, Knight R, Fierer N, et al. Bacterial phylogeny structures soil resistomes across habitats. Nature. 2014;509:612–616. doi: 10.1038/nature13377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pehrsson EC, Tsukayama P, Patel S, Mejía-Bautista M, Sosa-Soto G, Navarrete KM, et al. Interconnected microbiomes and resistomes in low-income human habitats. Nature. 2016;533:212–216. doi: 10.1038/nature17672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu J, Taft DH, Maldonado-Gomez MX, Johnson D, Treiber ML, Lemay DG, et al. The fecal resistome of dairy cattle is associated with diet during nursing. Nat Commun. 2019;10:1–15. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-12111-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Candela T, Marvaud JC, Nguyen TK, Lambert T. A cfr-like gene cfr(C) conferring linezolid resistance is common in Clostridium difficile. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2017;50:496–500. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2017.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Vester B. The cfr and cfr-like multiple resistance genes. Res Microbiol. 2018;169:61–66. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2017.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huang J, Sun J, Wu Y, Chen L, Duan D, Lv X, et al. Identification and pathogenicity of an XDR Streptococcus suis isolate that harbours the phenicol-oxazolidinone resistance genes optrA and cfr, and the bacitracin resistance locus bcrABDR. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2019;54:43–48. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2019.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huang J, Chen L, Wu Z, Wang L. Retrospective analysis of genome sequences revealed the wide dissemination of optrA in Gram-positive bacteria. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2017;72:614–616. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkw488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Du F, Lv X, Duan D, Wang L, Huang J. Characterization of a linezolid- and vancomycin-resistant Streptococcus suis isolate that harbors optrA and vanG operons. Front Microbiol. 2019;10. 10.3389/fmicb.2019.02026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.WHO Guidelines on use of medically important antimicrobials in food-producing animals. Geneva; 2017. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/258970/9789241550130-eng.pdf. Accessed 18 Apr 2020.

- 42.Bender JK, Cattoir V, Hegstad K, Sadowy E, Coque TM, Westh H, et al. Update on prevalence and mechanisms of resistance to linezolid, tigecycline and daptomycin in enterococci in Europe: Towards a common nomenclature. Drug Resist Updat. 2018;40:25–39. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2018.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Van Gompel L, Luiken REC, Sarrazin S, Munk P, Knudsen BE, Hansen RB, et al. The antimicrobial resistome in relation to antimicrobial use and biosecurity in pig farming, a metagenome-wide association study in nine European countries. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2019;74:865–876. doi: 10.1093/jac/dky518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Perry JA, Wright GD. The antibiotic resistance “mobilome”: searching for the link between environment and clinic. Front Microbiol. 2013;4:138. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2013.00138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Looft T, Johnson TA, Allen HK, Bayles DO, Alt DP, Stedtfeld RD, et al. In-feed antibiotic effects on the swine intestinal microbiome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:1691–1696. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1120238109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gillings MR. Evolutionary consequences of antibiotic use for the resistome, mobilome, and microbial pangenome. Front Microbiol. 2013;4. 10.3389/fmicb.2013.0000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Marchant M, Vinué L, Torres C, Moreno MA. Change of integrons over time in Escherichia coli isolates recovered from healthy pigs and chickens. Vet Microbiol. 2013;163:124–132. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2012.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Argüello H, Guerra B, Rodríguez I, Rubio P, Carvajal A. Characterization of antimicrobial resistance determinants and Class 1 and Class 2 Integrons in Salmonella enterica spp., multidrug-resistant isolates from pigs. Genes (Basel) 2018;9:256. doi: 10.3390/genes9050256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gillings MR. Integrons: past, present, and future. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2014;78:257–77. 10.1128/MMBR.00056-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Hendriksen RS, Munk P, Njage P, van Bunnik B, McNally L, Lukjancenko O, et al. Global monitoring of antimicrobial resistance based on metagenomics analyses of urban sewage. Nat Commun. 2019;10:1124. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-08853-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Burcham ZM, Schmidt CJ, Pechal JL, Brooks CP, Rosch JW, Benbow ME, et al. Detection of critical antibiotic resistance genes through routine microbiome surveillance. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0213280. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0213280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.EMA . European Surveillance of Veterinary Antimicrobial Consumption (ESVAC) Sales Data and Antimal Population Data Collection Protocol (version 3) 2019. pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schmieder R, Edwards R. Quality control and preprocessing of metagenomic datasets. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:863–864. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Peng Y, Leung HCM, Yiu SM, Chin FYL. IDBA-UD: A de novo assembler for single-cell and metagenomic sequencing data with highly uneven depth. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:1420–1428. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wood DE, Lu J, Langmead B. Improved metagenomic analysis with Kraken 2. Genome Biol. 2019;20:257. doi: 10.1186/s13059-019-1891-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zankari E, Hasman H, Cosentino S, Vestergaard M, Rasmussen S, Lund O, et al. Identification of acquired antimicrobial resistance genes. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67:2644. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Langmead B, Salzberg SL. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods. 2012;9:357–359. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Langmead B, Wilks C, Antonescu V, Charles R. Scaling read aligners to hundreds of threads on general-purpose processors. Bioinformatics. 2019;35:421–432. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shah N, Nute MG, Warnow T, Pop M. Misunderstood parameter of NCBI BLAST impacts the correctness of bioinformatics workflows. Bioinformatics. 2019;35:1613–1614. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Krawczyk PS, Lipinski L, Dziembowski A. PlasFlow: predicting plasmid sequences in metagenomic data using genome signatures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 62.Cury J, Jové T, Touchon M, Néron B, Rocha EP. Identification and analysis of integrons and cassette arrays in bacterial genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:4359–4550. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rognes T, Flouri T, Nichols B, Quince C, Mahé F. VSEARCH: A versatile open source tool for metagenomics. PeerJ. 2016:e2584. 10.7717/peerj.2584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 64.R Core Team . R: A language and environment for statistical computing. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Oksanen JF, Blanchet G, Friendly M, Kindt R, Legendre P, McGlinn D, et al. vegan: Community Ecology Package. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kassambara A. ggpubr: ggplot2 Based Publication Ready Plots. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc Ser B. 1995;57:289–300. doi: 10.1111/j.2517-6161.1995.tb02031.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Harrell FE. Hmisc: Harrell Miscellaneous. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Paradis E, Schliep K. ape 5.0: an environment for modern phylogenetics and evolutionary analyses in R. Bioinformatics. 2019;35:526–528. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wickham H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. 2016. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Figure S1. Alpha diversity of different antimicrobial resistance (AMR) classes measured by A) Simpson and B) Shannon indexes. These indexes were calculated from the counts per million matrix and represented as boxplots. Each sample is represented by a dot with horizontal jitter for visibility. The horizontal box lines represent the first quartile, the median, and the third quartile. Whiskers include the range of points within the 1.5 interquartile range. The differences per sample type and per production system within each sample type were evaluated with the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. n = 105 metagenomes from 38 independent farms. Nineteen metagenomes per sample type per production system were used, with the exception of extensive-slurry (n = 9). MLSP refers to the macrolides-lincosamides-streptogramins-pleuromutilins AMR class.

Additional file 2: Figure S2. Resistome variation among different types of production system and samples at antimicrobial resistance (AMR) class level. Two-dimension non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) based on Bray-Curtis dissimilarities was calculated for A) Beta-lactams, B) Tetracyclines, C) MLSP and D) Aminoglycosides. Subsampling was carried out by the three types of samples within each production system prior to performing ordination analysis and PERMANOVA. The centroid of each ellipse represents the group mean, and the shape was defined by the covariance within each group. Each NMDS was divided by the two production systems to observe clearer differences. n = 105 metagenomes from 38 independent farms. Nineteen metagenomes per production system per sample type were used, with the exception of extensive-slurry (n = 9). MLSP refers to the macrolides-lincosamides-streptogramins-pleuromutilins AMR class.

Additional file 3: Table S1. Resistome variation among different production systems and samples at AMR class level.

Additional file 4: Figure S3. Overview of antimicrobial resistance genes (ARGs) abundance within antimicrobial resistance (AMR) classes per sample. Boxplots of the ARGs in counts per million within each AMR class per sample, were stratified by production system and sample type. Each sample is represented by a dot with horizontal jitter for visibility. The horizontal box lines represent the first quartile, the median, and the third quartile. Whiskers include the range of points within the 1.5 interquartile range. The differences per sample type and per production system within each sample type were evaluated with the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. n = 105 metagenomes from 38 independent farms. Nineteen metagenomes per production system per sample type were used, with the exception of extensive-slurry (n = 9). MLSP refers to the macrolides-lincosamides-streptogramins-pleuromutilins AMR class.

Additional file 5: Tables S2-S11. Significant associations at antimicrobial resistance class and antimicrobial resistance genes level (p < 0.05) across production systems and sample types.

Additional file 6: Figure S4. Association between the resistome and the bacterial microbiome composition. A) Correlation between antimicrobial resistance genes and bacterial abundance at family level using Procrustes analyses. The lines show the Procrustes residuals; the change in the ordination position when using the resistome (dotted ends) compared to the bacterial microbiome (non-dotted ends) is displayed. The correlation coefficient and significance were determined using the “protest” function in R package vegan. B) Residual error plot for Procrustes residual size comparison showing the difference in the resistome-microbiome association across production systems and sample types. Horizontal lines denote the median (solid), 25% and 75% quantiles (dashed). n = 105 metagenomes from 38 independent farms. Nineteen metagenomes per production system per sample type were used, with the exception of extensive-slurry (n = 9).

Additional file 7:. Supplementary information. Supplementary text with additional information.