Abstract

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a global pandemic impacting 213 countries/territories and more than 5,934,936 patients worldwide. Cardiac injury has been reported to occur in severe and death cases. This meta-analysis was done to summarize available findings on the association between cardiac injury and severity of COVID-19 infection. Online databases including Scopus, PubMed, Web of Science, Cochrane Library and Google Scholar were searched to detect relevant publications up to 20 May 2020, using relevant keywords. To pool data, a fixed- or random-effects model was used depending on the heterogeneity between studies. In total, 22 studies with 3684 COVID-19 infected patients (severe cases=1095 and death cases=365) were included in this study. Higher serum levels of lactate dehydrogenase (weighted mean difference (WMD) =108.86 U/L, 95% confidence interval (CI)=75.93–141.79, p<0.001) and creatine kinase-MB (WMD=2.60 U/L, 95% CI=1.32–3.88, p<0.001) were associated with a significant increase in the severity of COVID-19 infection. Furthermore, higher serum levels of lactate dehydrogenase (WMD=213.44 U/L, 95% CI=129.97–296.92, p<0.001), cardiac troponin I (WMD=26.35 pg/mL, 95% CI=14.54–38.15, p<0.001), creatine kinase (WMD=48.10 U/L, 95% CI=0.27–95.94, p = 0.049) and myoglobin (WMD=159.77 ng/mL, 95% CI=99.54–220.01, p<0.001) were associated with a significant increase in the mortality of COVID-19 infection. Cardiac injury, as assessed by serum analysis (lactate dehydrogenase, cardiac troponin I, creatine kinase (-MB) and myoglobin), was associated with severe outcome and death from COVID-19 infection.

Keywords: COVID-19, heart injury, meta-analysis, systematic review

Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a global pandemic impacting 213 countries and territories around the world. As of 31 May 2020, a total of 5,934,936 COVID-19 confirmed cases and 367,166 deaths have been reported worldwide.1 Full-genome sequencing indicated that the novel coronavirus belongs to the β genus of coronavirus, which also includes severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS).2

COVID-19 infection is caused by binding of the viral spike protein to the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor following activation of the viral spike protein by transmembrane protease serine 2.3 ACE2 is highly expressed in the lung, vascular endothelium, intestinal epithelium, liver and the kidneys, providing a mechanism for the multi-organ failure that can be seen with COVID-19 infection.4,5 ACE2 is also expressed in the heart, counteracting the effects of angiotensin II in states with intense activation of the renin–angiotensin system such as congestive heart failure, hypertension and atherosclerosis.4

Several studies have reported the clinical and laboratory findings associated with cardiovascular disease in patients with COVID-19 infection.6–27 We are aware of no systematic review and meta-analysis that summarized available findings in this regard. Thus, in the present study, the laboratory findings and mechanism of cardiac dysfunction caused by COVID-19 infection were summarized.

Methods

Study protocol

A systematic literature search and a quantitative meta-analysis were conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines.28

Search strategy

We conducted a literature search using the online databases of Scopus, PubMed, Web of Science, Cochrane Library and Google Scholar for relevant publications up to 20 May 2020. The following medical subject headings (MeSH) and non-MeSH keywords were used: (‘Severe acute respiratory syndrome Coronavirus 2’ OR ‘SARS-CoV-2’ OR ‘COVID-19’ OR ‘Novel Coronavirus’ OR ‘2019-nCoV’) AND (‘Cardiovascular Disease’ OR ‘Heart’ OR ‘Troponin I’ OR ‘Creatine Kinase’ OR ‘Creatine Kinase, MB Form’ OR ‘Myoglobin’ OR ‘Lactate Dehydrogenase’). The literature search was performed by two independent researchers (MP and AS). We also searched the reference lists of the relevant articles to identify missed studies. No restriction was applied to language and time of publication. To facilitate the screening process of articles, all search results were downloaded into an EndNote library (version X8, Thomson Reuters, Philadelphia, USA). The search strategies and keywords are presented in detail in Supplementary Material Table 1 online.

Eligibility criteria

Studies were included in this review if they met the following inclusion criteria: (1) observational studies with retrospective or prospective design; (2) all articles assessing the association between serum levels of cardiac troponin I, creatine kinase, creatine kinase-MB, myoglobin, lactate dehydrogenase and severe outcome or death from COVID-19 infection as the major outcomes of interest and reported median (interquartile range; IQR) or mean (SD) for serum levels of these biomarkers. Review studies, books, expert opinion articles and theses were excluded.

Data extraction and assessment for study quality

Two independent researchers (MP and SY) extracted the following data from the studies: time of publication, first author’s name, age and gender of patients, sample size, study design, serum levels of cardiac troponin I, creatine kinase, creatine kinase-MB, myoglobin and lactate dehydrogenase and outcome assessment methods.

The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale was used for quality assessment of included articles.29 Based on these criteria, a maximum of nine points can be awarded to each study. In this systematic review and meta-analysis, studies with the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale score of ⩾ 5 were considered as high quality studies.

Statistical analysis

Median (IQR) or mean (SD) for serum levels of cardiac troponin I, creatine kinase, creatine kinase-MB, myoglobin and lactate dehydrogenase were used to estimate the effect size. The fixed- or random-effect model was used based on the heterogeneity between studies. Heterogeneity of the studies was assessed using the Cochrane Q test and I2 statistics.30 The publication bias was evaluated by the Egger’s regression tests and visual inspection of funnel plot.31 The sensitivity analysis was performed to evaluate the effect of each study on the pooled effect size. All statistical analyses were done using the Stata 14 software package (Stata Corp., College Station, Texas, USA).

Results

Search results

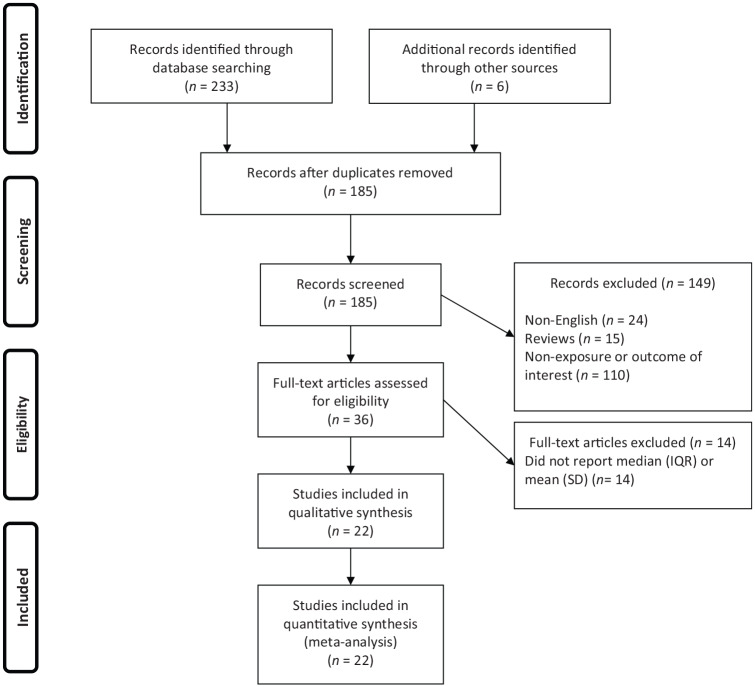

Overall, 239 publications were identified in our literature search. Of these, 54 duplicates, 24 non-English, 15 reviews and 110 publications that did not fulfill our eligibility criteria were excluded, leaving 36 articles for further assessment. Out of remaining 36 articles, 14 were excluded because of the following reason: did not report median (IQR) or mean (SD). Finally, we included 22 articles in the present systematic review and meta-analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of study selection.

IQR: interquartile range

Study characteristics

All studies were conducted in China. Twenty studies used retrospective design6,7,9–18,20–27 and two studies used prospective design.8,19 The sample size of studies ranged from 10 to 645 patients (mean age in severe patients: 60.95 years, mean age in non-severe patients: 46.95 years). All studies used real-time reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction to confirm COVID-19 infection. The characteristics of the included studies are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies included in the meta-analysis.

| Authors (year) | Design of study | Country | Mean age, years | Sample size | Sex | Pre-existing CVDs, n (%) | COVID-19 detection | Disease severity criteria | Serum levels in severe cases, mean±SD | Serum levels in mild cases, mean±SD | The time interval between laboratory tests and disease severity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chen G et al. (2020) | Retrospective | China | 56.5 | 21 Severe cases: 11 Mild cases: 10 | F/M | Not reported | Real-time RT-PCR | The guidelines for diagnosis and management of COVID-19 (6th edition, in Chinese) by the National Health Commission of China | LDH: 537.0±202.1 CK: 214.0±177.1 | LDH: 224.0±38.1 CK: 64.0±19.2 | Laboratory tests and disease severity were assessed at the same time on admission |

| Chen T et al. (2020) | Retrospective | China | 59.5 | 274 Severe cases: 113 Mild cases: 161 | F/M | Death cases: 16 (14%) Recovered cases: 7 (4%) | Real-time RT-PCR | The guidelines for diagnosis and management of COVID-19 (6th edition, in Chinese) by the National Health Commission of China | LDH: 564.5±210.9 cTnI: 40.8±106 CK: 189±207.4 | LDH: 268.0±75.7 cTnI: 3.3±3.8 CK: 84.0±66.3 | Laboratory tests and disease severity were assessed at the same time on admission |

| Du RH et al. (2020) (a) | Retrospective | China | 70.7 | 109 Severe cases: 51 Mild cases: 58 | F/M | Severe cases: 15 (29.4%) Mild cases: 22 (37.9) | Real-time RT-PCR | The patients were diagnosed according to the World Health Organization interim guidance for COVID-19 | Myo: 71.4±86.4 | Myo: 68.1±72.7 | Laboratory tests and disease severity were assessed at the same time on admission |

| Du RH et al. (2020) (b) | Prospective | China | 57.6 | 179 Death cases: 21 Recovered cases: 158 | F/M | Death cases: 12 (57.1%) Recovered cases: 17 (10.8%) | Real-time RT-PCR | The patients were diagnosed according to the World Health Organization interim guidance for COVID-19 | Myo: 162.0±218.0 | Myo: 32.3±33.2 | Laboratory tests and disease severity were assessed at the same time on admission |

| Han H et al. (2020) | Retrospective | China | 213 Severe cases: 15 Mild cases: 198 | F/M | Not reported | Real-time RT-PCR | The patients were diagnosed according to the World Health Organization interim guidance for COVID-19 | cTnI: 10.0±14.8 Myo: 75.3±66.1 | cTnI: 10.0±7.4 Myo: 34.7±20.8 | Laboratory tests and disease severity were assessed at the same time on admission | |

| Huang C et al. (2020) | Prospective | China | 49.0 | 41 Severe cases: 13 Mild cases: 28 | F/M | Severe cases: 3 (23%) Mild cases: 3 (11%) | Real-time RT-PCR | The diagnosis of pneumonia was based on clinical characteristics, chest imaging, and the ruling out of common bacterial and viral pathogens that cause pneumonia | LDH: 400.0±188.9 cTnI: 3.3±118.5 CK: 132.0±304.4 | LDH: 281.0±91.8 cTnI: 3.5±3.4 CK: 133.0±94.8 | Laboratory tests and disease severity were assessed at the same time on admission |

| Ji D et al. (2020) | Retrospective | China | 44.0 | 208 Severe cases: 40 Mild cases: 168 | F/M | Not reported | Real-time RT-PCR | The guidelines for diagnosis and management of COVID-19 by the National Health Commission of China and the World Health Organization interim guidance for COVID-19 | LDH: 304.0±105.2 | LDH: 224.0±48.9 | Laboratory tests and disease severity were assessed at the same time on admission |

| Lo IL et al. (2020) | Retrospective | China | 54.0 | 10 Severe cases: 4 Mild cases: 6 | F/M | Not reported | Real-time RT-PCR | The guidelines for diagnosis and management of COVID-19 (6th edition, in Chinese) by the National Health Commission of China | LDH: 238.0±52.0 | LDH: 183.0±61.0 | Laboratory tests and disease severity were assessed at the same time on admission |

| Mo P et al. (2020) | Retrospective | China | 53.5 | 155 Severe cases: 85 Mild cases: 70 | F/M | Severe cases: 14 (16.5%) Mild cases: 0 | Real-time RT-PCR | The diagnosis of pneumonia was based on clinical characteristics and chest imaging | LDH: 293.0±178.5 CK: 89.0±59.2 | LDH: 241.0±103.7 CK: 100.0±63.7 | Laboratory tests and disease severity were assessed at the same time on admission |

| Qu R et al. (2020) | Retrospective | China | 54.7 | 30 Severe cases: 3 Mild cases: 27 | F/M | Not reported | Real-time RT-PCR | The guidelines for diagnosis and management of COVID-19 (6th edition, in Chinese) by the National Health Commission of China | LDH: 772.3±292.3 | LDH: 528.1±188.6 | Laboratory tests and disease severity were assessed at the same time on admission |

| Ruan Q et al. (2020) | Retrospective | China | 58.5 | 150 Severe cases: 68 Mild cases: 82 | F/M | Death cases: 13 (19%) Recovered cases: 0 | Real-time RT-PCR | The diagnosis of pneumonia was based on clinical characteristics and chest imaging | cTnI: 30.3±151.0 Myo: 258.9±307.6 | cTnI: 3.5±6.2 Myo: 77.7±136.1 | Not reported |

| Wan S et al. (2020) | Retrospective | China | 50.0 | 135 Severe cases: 40 Mild cases: 95 | F/M | Severe cases: 6 (15%) Mild cases: 1 (1 %) | Real-time RT-PCR | The patients were diagnosed according to the World Health Organization interim guidance for COVID-19 | LDH: 309.0±114.4 CK: 82.0±66.6 | LDH: 212.0±58.9 CK: 57.0±37.0 | Laboratory tests and disease severity were assessed at the same time on admission |

| Wang D et al. (2020) | Retrospective | China | 58.5 | 138 Severe cases: 36 Mild cases: 102 | F/M | Severe cases: 9 (25%) Mild cases: 11 (10.8%) | Real-time RT-PCR | The patients were diagnosed according to the World Health Organization interim guidance for COVID-19 | LDH: 435.0±217.8 cTnI: 11.0±15.4 CK: 102.0±140.7 CKMB: 18.0±17.0 | LDH: 212.0±89.6 cTnI: 5.1±5.7 CK: 87.0±49.6 CKMB: 13.0±2.9 | Laboratory tests were done on admission. The median time from admission to developing severe outcome was one day (IQR, 0–3 days) |

| Wang L et al. (2020) | Retrospective | China | 69.0 | 339 Death cases: 65 Recovered cases: 274 | F/M | Death cases: 21 (32.8%) Recovered cases: 32 (11.7%) | Real-time RT-PCR | The guidelines for diagnosis and management of COVID-19 (6th edition, in Chinese) by the National Health Commission of China and the World Health Organization interim guidance for COVID-19 | LDH: 439.0±209.6 CK: 84.0±127.4 | LDH: 286.0±100.0 CK: 60.0±42.2 | Laboratory tests and disease severity were assessed at the same time on admission |

| Wang Z et al. (2020) | Retrospective | China | 53.7 | 69 Severe cases: 14 Mild cases: 55 | F/M | Severe cases: 5 (36%) Mild cases: 3 (5%) | Real-time RT-PCR | The guidelines for diagnosis and management of COVID-19 (3rd edition, in Chinese) by the National Health Commission of China | LDH: 517.5±208.9 | LDH: 207.0±68.9 | Laboratory tests were done on admission. The median timefrom admission to developing severe outcome was one day (IQR, 0–2 days). |

| Wu C et al. (2020) | Retrospective | China | 53.2 | 201 Severe cases: 84 Mild cases: 117 | F/M | Severe cases: 5 (6%) Mild cases: 3 (2.6%) Death cases: 4 (9.1%) Recovered cases: 4 (10%) | Real-time RT-PCR | The patients were diagnosed according to the World Health Organization interim guidance for COVID-19 | LDH: 396.0±148.9 CKMB: 17.0±5.5 Death cases: LDH: 484.0±161.1 CKMB: 17.0±5.2 | LDH: 257.0±81.1 CKMB: 15.0±5.2 Recovered cases: LDH: 349.5±90.7 CKMB: 16.0±5.7 | Laboratory tests were done on admission. The median time from admission to developing severe outcome was two days (IQR, 1–4 days) |

| Wu J et al. (2020) | Retrospective | China | 43.1 | 280 Severe cases: 83 Mild cases: 197 | F/M | Severe cases: 43 (51.8%) Mild cases: 14 (7.1%) | Real-time RT-PCR | The patients were diagnosed according to the World Health Organization interim guidance for COVID-19 | LDH: 235.0±137.0 CK: 76.0±168.1 CKMB: 13.0±12.5 | LDH: 184.0±79.2 CK: 67.0±38.5 CKMB: 9.0±5.2 | Laboratory tests and disease severity were assessed at the same time on admission |

| Zhang X et al. (2020) | Retrospective | China | 40.7 | 645 Severe cases: 573 Mild cases: 72 | F/M | Severe cases: 5 (1%) Mild cases: 0 | Real-time RT-PCR | The guidelines for diagnosis and management of COVID-19 (5th edition, in Chinese) by the National Health Commission of China and the World Health Organization interim guidance for COVID-19 | LDH: 213.0±70.4 CK: 73.0±46.7 | LDH: 174.5±64.8 CK: 62.5±27.2 | laboratory tests were done on admission. The time from onset to COVID-19 infection confirmation was 5.0 (2.5–7.0) days among patients with severe outcome |

| Zheng F et al. (2020) | Retrospective | China | 45.0 | 161 Severe cases: 30 Mild cases: 131 | F/M | Severe cases: 2 (6.7%) Mild cases: 2 (1.5%) | Real-time RT-PCR | The guidelines for diagnosis and management of COVID-19 (5th edition, in Chinese) by the National Health Commission of China | LDH: 226.2±90.1 CK: 100.3±249.8 | LDH: 162.0±55.4 CK: 68.7±50.4 | Laboratory tests and disease severity were assessed at the same time on admission |

| Zhou B et al. (2020) | Retrospective | China | 65 | 34 Severe cases: 8 Mild cases: 26 | F/M | Not reported | Real-time RT-PCR | The guidelines for diagnosis and management of COVID-19 (4th edition, in Chinese) by the National Health Commission of China | LDH: 513.0±168.1 cTnI: 46.8±196.7 CK: 199.0±154.1 CKMB: 13.0±11.1 Myo: 101.7±113.3 | LDH: 287.0±62.9 cTnI: 4.8±4.4 CK: 88.0±59.2 CKMB: 10.0±2.9 Myo: 62.8±40.5 | Laboratory tests and disease severity were assessed at the same time on admission |

| Zhou F et al. (2020) | Retrospective | China | 60.5 | 191 Severe cases: 54 Mild cases: 137 | F/M | Death cases: 13 (24%) Recovered cases: 2 (1%) | Real-time RT-PCR | The guidelines for diagnosis and management of COVID-19 (6th edition, in Chinese) by the National Health Commission of China and the World Health Organization interim guidance for COVID-19 | LDH: 521.0±226.7 cTnI: 22.2±57.4 CK: 39.0±97.4 | LDH: 253.5±73.3 cTnI: 3.0±3.2 CK: 18.0±29.3 | Laboratory tests and disease severity were assessed at the same time on admission |

| Zhou Y et al. (2020) | Retrospective | China | 41.8 | 17 Severe cases: 5 Mild cases: 12 | F/M | Not reported | Real-time RT-PCR | The guidelines for diagnosis and management of COVID-19 (5th edition, in Chinese) by the National Health Commission of China | LDH: 157.0±72.6 | LDH: 180.0±135.5 | Laboratory tests and disease severity were assessed at the same time on admission |

COVID-19: coronavirus disease 2019; F: female; M: male; CVD: cardiovascular disease; RT-PCR: reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction; LDH: lactate dehydrogenase; CK: creatine kinase; cTnI: cardiac troponin I; Myo: myoglobin; CKMB: creatine kinase-MB; IQR: interquartile range

Serum levels of lactate dehydrogenase, creatine kinase-MB, creatine kinase, cardiac troponin I, myoglobin and severity of COVID-19 infection

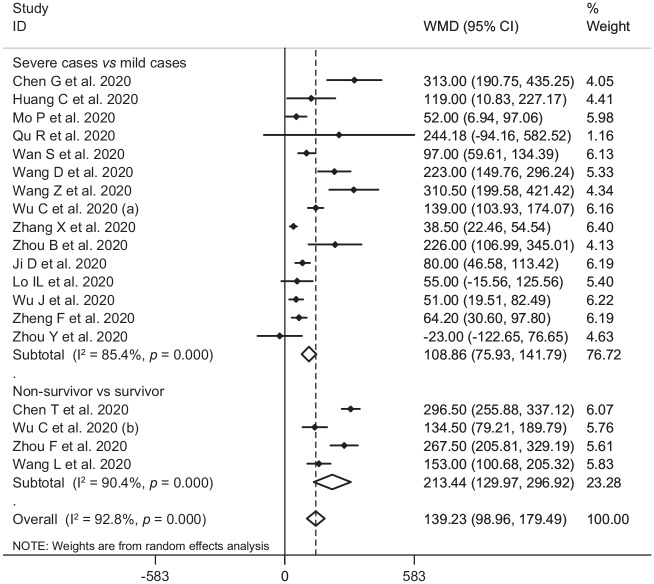

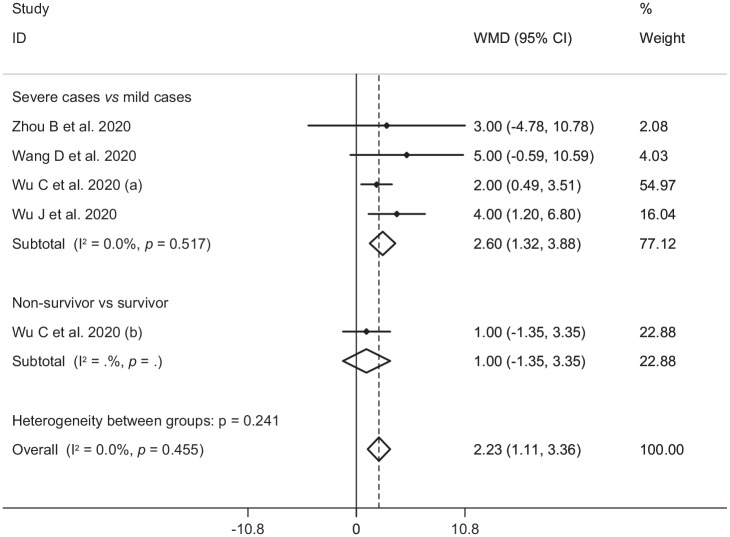

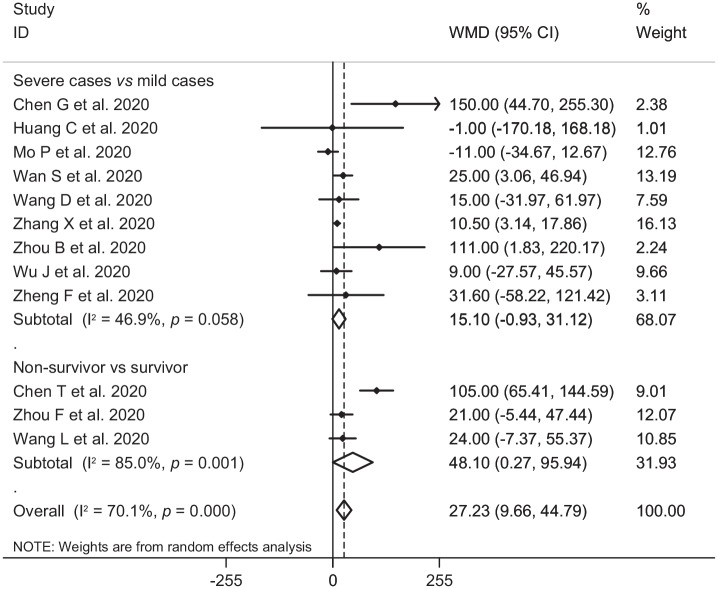

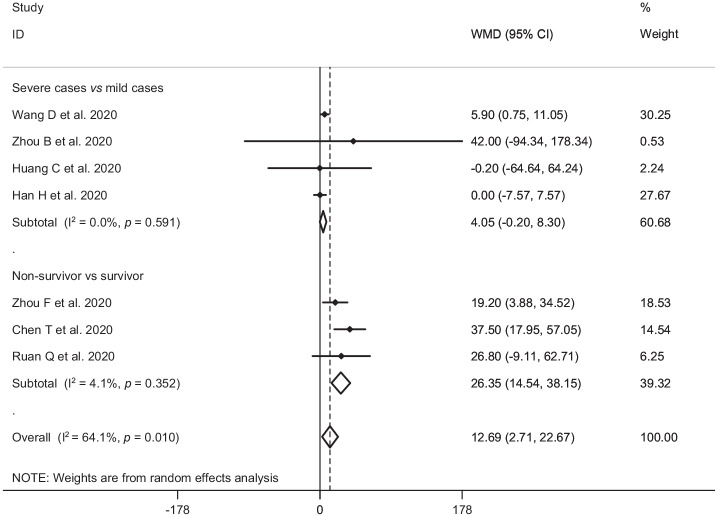

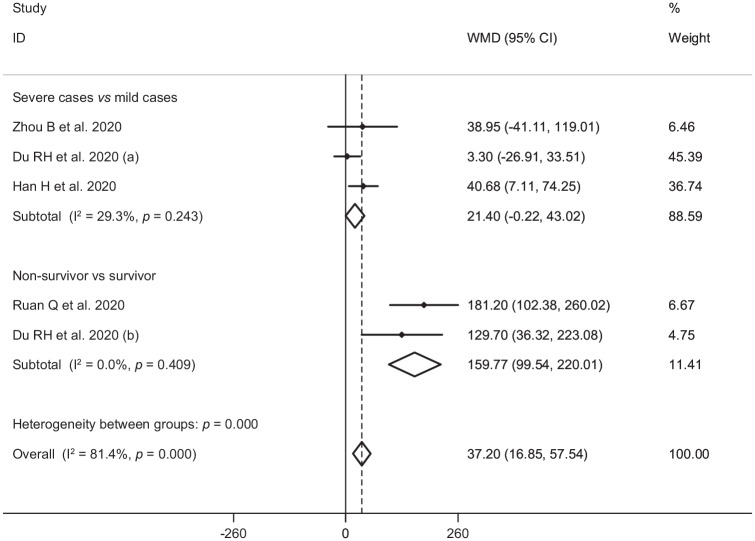

In the pooled estimate of 17 studies6,8–16,18,20–22,24–26 with 2467 COVID-19 infected patients (severe patients = 1095 and non-severe patients = 1372), it was shown that higher serum levels of lactate dehydrogenase (weighted mean difference = 108.86 U/L, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 75.93 to 141.79, p<0.001, I2 = 85.4%, pheterogeneity <0.001) (Figure 2) and creatine kinase-MB (weighted mean difference = 2.60 U/L, 95% CI = 1.32 to 3.88, p<0.001, I2 = 0.0%, pheterogeneity = 0.517) (Figure 3) were associated with a significant increase in the severity of COVID-19 infection. Combined results showed that serum levels of creatine kinase (weighted mean difference = 15.10 U/L, 95% CI = ‒0.93 to 31.12, p = 0.065, I2 = 46.9%, pheterogeneity = 0.058) (Figure 4), cardiac troponin I (weighted mean difference = 4.05 pg/mL, 95% CI = ‒0.20 to 8.30, p = 0.062, I2 = 0.0%, pheterogeneity = 0.591) (Figure 5) and myoglobin (weighted mean difference = 21.40 ng/mL, 95% CI = ‒0.22 to 43.02, p = 0.052, I2 = 29.3%, pheterogeneity = 0.243) (Figure 6) had no significant association with severity of the disease.

Figure 2.

Forest plot for the association between serum levels of lactate dehydrogenase and severe outcome or death from COVID-19 infection using random-effects model.

WMD: weighted mean difference; CI: confidence interval

Figure 3.

Forest plot for the association between serum levels of creatine kinase-MB and severe outcome or death from COVID-19 infection using fixed-effects model.

WMD: weighted mean difference; CI: confidence interval

Figure 4.

Forest plot for the association between serum levels of creatine kinase and severe outcome or death from COVID-19 infection using random-effects model.

WMD: weighted mean difference; CI: confidence interval

Figure 5.

Forest plot for the association between serum levels of cardiac troponin I and severe outcome or death from COVID-19 infection using random-effects model.

WMD: weighted mean difference; CI: confidence interval

Figure 6.

Forest plot for the association between serum levels of myoglobin and severe outcome or death from COVID-19 infection using fixed-effects model.

WMD: weighted mean difference; CI: confidence interval

Serum levels of lactate dehydrogenase, creatine kinase-MB, creatine kinase, cardiac troponin I, myoglobin and mortality from COVID-19 infection

Six studies7,14,17,19,23,27 including a total of 1217 patients with COVID-19 infection (non-survivor = 365 and survivor = 852) reported mortality as an outcome measure. Combined results showed that higher serum levels of lactate dehydrogenase (weighted mean difference = 213.44 U/L, 95% CI = 129.97 to 296.92, p<0.001, I2 = 90.4%, pheterogeneity <0.001) (Figure 2), creatine kinase (weighted mean difference = 48.10 U/L, 95% CI = 0.27 to 95.94, p = 0.049, I2 = 85.0%, pheterogeneity = 0.001) (Figure 4), cardiac troponin I (weighted mean difference = 26.35 pg/mL, 95% CI = 14.54 to 38.15, p<0.001, I2 = 4.1%, pheterogeneity = 0.352) (Figure 5) and myoglobin (weighted mean difference = 159.77 ng/mL, 95% CI = 99.54 to 220.01, p<0.001, I2 = 0.0%, pheterogeneity = 0.409) (Figure 6) were associated with a significant increase in the mortality of COVID-19 infection.

Publication bias and sensitivity analysis

Based on the results of Egger’s test, we found no evidence of publication bias for lactate dehydrogenase (p=0.454), creatine kinase-MB (p=0.367), creatine kinase (p=0.220), cardiac troponin I (p=0.961) and myoglobin (p=0.748). Furthermore, findings from sensitivity analysis indicated that overall estimates did not depend on a single publication (Supplementary Figures 1–5).

Discussion

Findings from this review supported the hypothesis that heart injury is associated with severe outcome and death in patients with COVID-19 infection. To our knowledge, this study is the first meta-analysis to assess the association between serum levels of cardiac biomarkers and severity of COVID-19 infection.

Our results are partially in line with previous narrative reviews.32–36 Previously, cardiac lesion has been reported as a risk factor for severe outcome and death in SARS and MERS.37–40

Older age (⩾65 years), male gender and presence of comorbidities such as hypertension, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and cancer are known to be the major risk factors for COVID-19 mortality.41 Presence of myocarditis and cardiac injury (defined by elevated cardiac troponin I levels greater than the 99th percentile upper limit) are other independent risk factors associated with mortality.27,42

COVID-19 may either exacerbate underlying cardiovascular diseases and/or induce new cardiac pathologies. Previous studies have shown that the incidence of acute cardiac injury in severe COVID-19 patients and death cases ranged from 5% to 31% and 59% to 77%, respectively.7,8,11,17 Contributory mechanisms include hemodynamic changes, induction of pro-coagulant factors and systemic inflammatory responses that are mediators of atherosclerosis directly contributing to plaque rupture through local inflammation, which predispose to thrombosis and ischemia.43–45

In addition, ACE2, the receptor for COVID-19, is expressed on vascular endothelial cells and myocytes,46,47 so there is at least theoretical potential possibility of direct cardiovascular involvement by the virus. In theory this could have a potential impact on patients taking angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, resulting in greater risk of acquiring COVID-19 infection and increased severity of the disease.33

Other suggested mechanisms of COVID-19 related heart injury include cytokine storm, mediated by increased pro-inflammatory cytokine production by innate immunity after COVID-19 infection, and hypoxia induced excessive intracellular calcium leading to myocyte apoptosis.17,36

COVID-19 appears to affect the myocardium and cause myocarditis.48 Interstitial mononuclear inflammatory infiltrates in myocardium has been documented in death cases of COVID-19.48 Furthermore, cases of myocarditis with reduced systolic function have been reported after COVID-19 infection.32 Cardiac injury is likely associated with ischemia and/or infection-related myocarditis and is an important prognostic factor in patients with COVID-19 infection.

Cardiac biomarker studies suggest a high prevalence of heart injury in death cases of COVID-19 infection.48,42 Mortality was significantly higher in patients with high serum levels of lactate dehydrogenase, cardiac troponin I, creatine kinase and myoglobin. The mechanism of cardiac biomarker elevation in COVID-19 infection is not fully understood. The underlying pathophysiology is suggestive of a cardio-inflammatory response as many severe COVID-19 infected patients demonstrate concomitant elevations in cardiac biomarkers and acute phase reactants such as C-reactive protein.33 The rise in cardiac biomarkers with other inflammatory biomarkers raises the possibility that this reflects cytokine storm and may present clinically as fulminant myocarditis.33

Until effective and specific antiviral therapies against COVID-19 become available, the treatment of COVID-19 infection will be primarily based on the treatment of complications and supportive care. Treatment of cardiovascular complications should be based on optimal use of guideline-based therapies. As with other triggers for cardiovascular events, the use of β-blockers, statins and antiplatelet agents are recommended per practice guidelines.

The present study has some limitations. First, interpretation of findings might be limited by the small sample size. Second, this study did not include data such as body weight, body mass index and smoking history, which are potential risk factors for disease severity.

Conclusion

In this meta-analysis of 3534 patients with confirmed COVID-19, cardiac injury as assessed by serum analysis (lactate dehydrogenase, cardiac troponin I, creatine kinase (-MB) and myoglobin) was associated with severe outcome and death from COVID-19 infection. With the fast-moving development of COVID-19 across the globe and with better understanding of the mechanisms of cardiac involvement in patients with COVID-19 infection, cardiac biomarkers can be utilized as an indicator of improving response due to cardioprotective intervention or as a metric of a worsening clinical scenario.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Author contribution: MP and SY had the idea for the article, MP, SY and AS performed the literature search and data analysis, and MP and SY drafted and critically revised the work. Availability of data and materials: all data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this manuscript. Supplemental material: supplemental material for this article is available online.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease 2019. (COVID-19): Situation report-132. 31May2020. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200531-covid-19-sitrep-132.pdf?sfvrsn=d9c2eaef_2, (accessed 1 June 2020).

- 2. Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med 2020; 382: 727-733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hoffmann M, Kleine-Weber H, Schroeder S, et al. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell 2020; 181: 271-280.e278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tikellis C, Thomas MC. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) is a key modulator of the renin angiotensin system in health and disease. Int J Pept 2012; 2012: 256294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zhang H, Penninger JM, Li Y, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) as a SARS-CoV-2 receptor: Molecular mechanisms and potential therapeutic target. Intensive Care Med 2020; 46: 586-590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chen G, Wu D, Guo W, et al. Clinical and immunological features of severe and moderate coronavirus disease 2019. J Clin Invest 2020; 130: 2620-2629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chen T, Wu D, Chen H, et al. Clinical characteristics of 113 deceased patients with coronavirus disease 2019: Retrospective study. BMJ 2020; 368: m1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 2020; 395: 497-506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mo P, Xing Y, Xiao Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of refractory COVID-19 pneumonia in Wuhan, China. Clin Infect Dis 2020. 2020/03/17. DOI: 10.1093/cid/ciaa270. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Qu R, Ling Y, Zhang YH, et al. Platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio is associated with prognosis in patients with coronavirus disease-19. J Med Virol 2020. 2020/03/18. DOI: 10.1002/jmv.25767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wan S, Xiang Y, Fang W, et al. Clinical features and treatment of COVID-19 patients in northeast Chongqing. J Med Virol 2020; 92: 797-806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA 2020; 323: 1061-1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wang Z, Yang B, Li Q, et al. Clinical features of 69 cases with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. Clin Infect Dis 2020. Epub ahead of print 17March2020. DOI: 10.1093/cid/ciaa272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wu C, Chen X, Cai Y, et al. Risk factors associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome and death in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA Intern Med. Epub ahead of print 14March2020. DOI: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zhang X, Cai H, Hu J, et al. Epidemiological, clinical characteristics of cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection with abnormal imaging findings. Int J Infect Dis 2020; 94: 81-87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zhou B, She J, Wang Y, et al. The clinical characteristics of myocardial injury in severe and very severe patients with 2019 novel coronavirus disease. J Infect 2020; 81: 147-178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: A retrospective cohort study. Lancet 2020; 395: 1054-1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Du RH, Liu LM, Yin W, et al. Hospitalization and critical care of 109 decedents with COVID-19 pneumonia in Wuhan, China. Ann Am Thorac Soc. Epub ahead of print 08April2020. DOI: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202003-225OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Du RH, Liang LR, Yang CQ, et al. Predictors of mortality for patients with COVID-19 pneumonia caused by SARSCoV-2: A prospective cohort study. Eur Respir J 2020; 55: 2000524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Han H, Xie L, Liu R, et al. Analysis of heart injury laboratory parameters in 273 COVID-19 patients in one hospital in Wuhan, China. J Med Virol 2020; 92: 819-823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ji D, Zhang D, Xu J, et al. Prediction for progression risk in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia: The CALL Score. Clin Infect Dis. Epub ahead of print 10April2020. DOI: 10.1093/cid/ciaa414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lo IL, Lio CF, Cheong HH, et al. Evaluation of SARS-CoV-2 RNA shedding in clinical specimens and clinical characteristics of 10 patients with COVID-19 in Macau. Int J Biol Sci 2020; 16: 1698-1707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wang L, He W, Yu X, et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 in elderly patients: Characteristics and prognostic factors based on 4-week follow-up. J Infect 2020; 80: 639-645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wu J, Li W, Shi X, et al. Early antiviral treatment contributes to alleviate the severity and improve the prognosis of patients with novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19). J Intern Med. Epub ahead of print 29March2020. DOI: 10.1111/joim.13063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zheng F, Tang W, Li H, et al. Clinical characteristics of 161 cases of corona virus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Changsha. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2020; 24: 3404-3410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zhou Y, Zhang Z, Tian J, et al. Risk factors associated with disease progression in a cohort of patients infected with the 2019 novel coronavirus. Ann Palliat Med 2020; 9: 428-436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ruan Q, Yang K, Wang W, et al. Clinical predictors of mortality due to COVID-19 based on an analysis of data of 150 patients from Wuhan, China. Intensive Care Med 2020; 46: 1294-1297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med 2009; 151: 264-269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Stang A Critical evaluation of the Newcastle–Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol 2010; 25: 603-605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, et al. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003; 327: 557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Egger M, Smith GD, Schneider M, et al. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997; 315: 629-634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Madjid M, Safavi-Naeini P, Solomon SD, et al. Potential effects of coronaviruses on the cardiovascular system: A review. JAMA Cardiol. Epub ahead of print 29March2020. DOI: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gaze DC Clinical utility of cardiac troponin measurement in COVID-19 infection. Ann Clin Biochem 2020; 57: 202-205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Clerkin KJ, Fried JA, Raikhelkar J, et al. COVID-19 and cardiovascular disease. Circulation 2020; 141: 1648-1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chen L, Li X, Chen M, et al. The ACE2 expression in human heart indicates new potential mechanism of heart injury among patients infected with SARS-CoV-2. Cardiovasc Res 2020; 116: 1097-1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zheng YY, Ma YT, Zhang JY, et al. COVID-19 and the cardiovascular system. Nat Rev Cardiol 2020; 17: 259-260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Chang HL, Chen KT, Lai SK, et al. Hematological and biochemical factors predicting SARS fatality in Taiwan. J Formos Med Assoc 2006; 105: 439-450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Assiri A, Al-Tawfiq JA, Al-Rabeeah AA, et al. Epidemiological, demographic, and clinical characteristics of 47 cases of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus disease from Saudi Arabia: A descriptive study. Lancet Infect Dis 2013; 13: 752-761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ksiazek TG, Erdman D, Goldsmith CS, et al. A novel coronavirus associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N Engl J Med 2003; 348: 1953-1966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Cauchemez S, Fraser C, van Kerkhove MD, et al. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus: Quantification of the extent of the epidemic, surveillance biases, and transmissibility. Lancet Infect Dis 2014; 14: 50-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Fauci AS, Lane HC, Redfield RR. Covid-19 – navigating the uncharted. N Engl J Med 2020; 382: 1268-1269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Shi S, Qin M, Shen B, et al. Association of cardiac injury with mortality in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Cardiol. Epub ahead of print 27March2020. DOI: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.0950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Smeeth L, Thomas SL, Hall AJ, et al. Risk of myocardial infarction and stroke after acute infection or vaccination. N Engl J Med 2004; 351: 2611-2618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Corrales-Medina VF, Musher DM, Wells GA, et al. Cardiac complications in patients with community-acquired pneumonia: Incidence, timing, risk factors, and association with short-term mortality. Circulation 2012; 125: 773-781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Davidson JA, Warren-Gash C. Cardiovascular complications of acute respiratory infections: Current research and future directions. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2019; 17: 939-942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Gallagher PE, Ferrario CM, Tallant EA. Regulation of ACE2 in cardiac myocytes and fibroblasts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2008; 295: H2373-H2379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Mendoza-Torres E, Oyarzún A, Mondaca-Ruff D, et al. ACE2 and vasoactive peptides: Novel players in cardiovascular/renal remodeling and hypertension. Ther Adv Cardiovasc Dis 2015; 9: 217-237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Xu Z, Shi L, Wang Y, et al. Pathological findings of COVID-19 associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Lancet Respir Med 2020; 8: 420-422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.