Abstract

Introduction

Antibiotics are essential to treat infections during pregnancy and to reduce both maternal and infant mortality. Overall use, but especially non-indicated use, and misuse of antibiotics are drivers of antibiotic resistance (ABR). High non-indicated use of antibiotics for uncomplicated vaginal deliveries is widespread in many parts of the world. Similarly, irrational use of antibiotics is reported for children. There is scarcity of evidence regarding antibiotic use and ABR in Lao PDR (Laos). The overarching aim of this project is to fill those knowledge gaps and to evaluate a quality improvement intervention. The primary objective is to estimate the proportion of uncomplicated vaginal deliveries where antibiotics are used and to compare its trend before and after the intervention.

Methods and analysis

This 3-year, prospective, quasiexperimental study without comparison group includes a formative and interventional phase. Data on antibiotic use during delivery will be collected from medical records. Knowledge, attitudes and reported practices on antibiotic use in pregnancy, during delivery and for children, will be collected from women through questionnaires. Healthcare providers’ knowledge, attitudes and practices of antibiotics administration for pregnant women, during delivery and for children, will be collected via adapted questionnaires. Perceptions regarding antibiotics will be explored through focus group discussions with women and individual interviews with key stakeholders. Faecal samples for culturing of Escherichia coli and Klebsiella spp. and antibiotic susceptibility testing will be taken before, during and 6 months after delivery to determine colonisation of resistant strains. The planned intervention will comprise training workshops, educational materials and social media campaign and will be evaluated using interrupted time series analysis.

Ethics and dissemination

The project received ethical approval from the National Ethics Committee for Health Research, Ministry of Health, Laos. The results will be disseminated via scientific publications, conference presentations and communication with stakeholders.

Trail registration number

ISRCTN16217522; Pre-results.

Keywords: public health, obstetrics, gynaecology, microbiology

Strength and limitations of this study.

This is the first study that addresses perceptions, knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding antibiotic use and antibiotic resistance (ABR) among pregnant women and mothers of children under 2 and healthcare providers (HCPs) in Lao PDR, using interviews and records reviews.

This study is also the first to collect data on ABR carriage patterns of Escherichia coli and Klebsiella spp. among healthy pregnant women and their children in these settings.

We will generate evidence on knowledge of HCPs and community, and possibly decrease unnecessary use of antibiotics (especially for uncomplicated vaginal delivery), therefore contribute to containing the spread of ABR.

The broad range of stakeholders such as researchers, HCPs, local authorities and policy-makers involved in the study may contribute to the effective implementation of the intervention and development of national and local prescribing guidelines.

The study participants, both pregnant women and HCPs may tend to answer the questions about their practices in a way they think it is expected, therefore social desirability bias cannot be overruled.

Introduction

Antibiotics are life-saving medicines and important interventions in health systems.1 Misuse and overuse of antibiotics contribute to development and spread of antibiotic resistance (ABR)—one of the most pressing global health threats.2 3 ABR contributes to increased morbidity, mortality and healthcare costs, and disproportionately impacts poorer countries where access to, and use of, antibiotics is frequently coupled with a high prevalence of infectious disease, exacerbating global economic inequalities.4 ABR is a complex process driven by many interrelated factors.5–7 To effectively mitigate the emergence and dissemination of ABR, pragmatic and collaborative actions are required including behavioural change interventions and infections prevention and control measures.

Antibiotics are essential to treat common infections during pregnancy, to prevent maternal and neonatal infections during delivery, and to treat infections arising from surgical wounds after caesarean sections.8 9 Reports from Canada and The Netherlands showed that approximately 20%–25% of women received antibiotics during pregnancy.10 11 However, during pregnancy, the use of any medicines and specifically antibiotics is a risk-versus-benefit decision and needs to be carefully considered.

The use of antibiotics during the pregnancy delays final infant’s gut colonisation and during that time the infants are more susceptible to infections and to immune-mediated diseases.12 13 This might result in increased antibiotic consumption in childhood and ultimately leads to increased ABR.

Use of antibiotics for uncomplicated vaginal delivery is generally not recommended14; however, some reports show alarmingly high use in these situations. For instance, data from India showed that 87% of women who had vaginal delivery received antibiotics and 28% were discharged from the hospital with prescribed antibiotics regardless the mode of the delivery.15

Therefore, the use of antibiotics by the vulnerable groups, for example children and pregnant women, has to be carefully monitored and evaluated bearing in mind side effects such as nausea, diarrhoea or quinolone toxicity to the developing skeletal system.

The faecal microbiota serves as a reservoir for ABR genes. Exposure of commensals such as Escherichia coli to antibiotics may increase the carriage levels of resistance genes and facilitate their spread to pathogenic strains of bacteria.16 So far, a few studies have looked at ABR in bacteria isolated from humans in Lao PDR (Laos), mainly in the capital city Vientiane or province. One study from 2011 showed colonisation of Enterobacteriaceae producing extended spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBLs) among 23% of healthy pre-school children.17 Another study from one of the major hospitals in Vientiane shows increasing occurrence of ESBLs in bloodstream E. coli isolates.18 In contrast, case reports of colistin resistance (the last antibiotic option for multidrug resistant Gram-negative bacteria) showed a potentially severe situation relating to ABR in the country; however, a structured study to support these results is needed.19

While there is some evidence of irrational antibiotic use, studies on antibiotic use among children in Laos have, to our knowledge, not been conducted. Also, data regarding antibiotic use during pregnancy and childbirth in Laos are scarce. Data from 200820 showed that from 300 women with normal vaginal deliveries, 79% delivered at home, of those 25% used antibiotics and among women who delivered in hospitals 79% received antibiotics. Since then, the quality of antenatal care (ANC) has improved, is free of charge and attendance to ANC has increased. Data from Lao Social Indicators survey from 2017 show that 65% of women delivered at health facilities and more than 80% attended ANC at least once.

In this study protocol, we present the scheme of data collection, plan for data analysis and implementation and evaluation of the intervention targeted to healthcare providers (HCPs) and community.

The project Containment of Antibiotic REsistance—measures to improve antibiotic use in pregnancy, childbirth and young children (CAREChild) is an international project between partner institutions in Laos and Sweden that aims to understand and improve antibiotic use in relation to pregnancy, childbirth and early childhood in Laos with the long-term aim to contain ABR.

The specific objectives are to:

Estimate the proportion of uncomplicated vaginal deliveries where antibiotics are used and to compare its trend before and after the intervention.

Explore and assess perceptions, knowledge, attitudes and reported practice of pregnant women, and mothers of children under 2 regarding antibiotic use and resistance in relation to pregnancy, childbirth and children under 2 years of age.

Explore and assess perceptions, knowledge, attitudes, reported practice, as well as actual practice of HCPs regarding antibiotic use and resistance in relation to pregnancy, childbirth and children under 2 years of age.

Estimate the ABR situation with focus on ESBLs producing and multi-drug resistant E. coli and Klebsiella spp. carriage in faecal samples among women and children.

Develop and test interventions aimed at HCPs and community members to improve use of antibiotics.

We hypothesise that the use of antibiotics for uncomplicated vaginal deliveries is high and that the educational intervention will reduce the proportion of antibiotics administered and lead to an improvement in knowledge regarding antibiotic use and ABR of both community and HCPs.

Methods and analysis: study design and data collection

Study design

This is a 3-year, prospective, quasiexperimental, interventional study with both continuous and repeated data collection. The study will start with an extensive formative phase leading to the development of an intervention, which will be evaluated through time series analysis. In the formative phase potential barriers and facilitators for implementing the intervention will be identified. Collected data will inform about the context, adaptations and response to change of HCPs and the community behaviours in relation to antibiotic use. Quantitative and qualitative data will be collected before (formative phase) and after the intervention at all health facilities and in the community.

Study settings

The study will be conducted in Laos, a lower middle-income country in Southeast Asian with approximately 7 million inhabitants and relatively low population density.21 Laos has 17 provinces, 1 capital city, 148 districts and 8459 villages. Around two-thirds of the population lives in rural areas and relies on agricultural work, specifically rice farming. Individual villages in Laos tend to be home to a particular ethnic group.22 Feuang and Vang Vieng districts in Vientiane province in the central part of the country will be selected as study areas based on variations in background characteristics, representing different ethnic minority population and for feasibility reasons. In order to better understand the current situation of antibiotic use and ABR, all levels of healthcare facilities, that is Vientiane provincial hospital, two district hospitals and six health centres in each of the two study districts, will be purposively selected as the study sites. To avoid contamination, the qualitative part of the study before the intervention will be conducted in Thulakhom district (Vientiane province), which is outside the study area. For the same reason the pilot study will take place in Phonehong (Vientiane province) and Santhong districts (Vientiane capital). List of the study sites can be obtained on request from the local principal investigator.

Inclusion criteria for women

All pregnant women in the third trimester, who after the enrolment plan to stay in the area for the next 24 months, who are willing to participate in the study, and whose infants are born during the study period.

Inclusion criteria for HCPs

All medical doctors, assistant doctors, midwives, nurses, pharmacists, assistant pharmacists at the Vientiane provincial hospital, district hospitals or health centres in Feuang or Vang Vieng as well as drug sellers (only pharmacists and assistant pharmacists) at private pharmacies in these districts.

For individual qualitative interviews: private providers (in private clinics and pharmacies) in the study area, representatives from central level such as Ministry of Health, university and professional organisations in addition to providers from the public healthcare facilities, HCPs and policy-makers from the Maternal and New-born Hospital in Vientiane capital, where women from different parts of the country come for ANC and consultation.

Data collection: pilot study

Building on the research team’s experiences15 23 and expertise of the local team, the data collection instruments were developed in English, adapted for different target groups and translated into Lao. In March 2019, a pilot study was conducted to field test the data collection instruments and procedures to train data collectors. In total, 30 questionnaires on knowledge, attitudes and reported practices were pilot tested with 10 HCPs, 10 pregnant women and 10 mothers of a child under 2. In parallel, to capture perceptions, focus group discussion (FGD) and qualitative interview guides were tested during one FGD with mothers and one FGD with pregnant women and four interviews with HCPs. Preliminary results from the pilot test have guided the final version of data collection instruments and shed light on possible components and acceptability of the intervention. A summary of the data collection instruments that will be used in the study is presented in table 1.

Table 1.

Data collection instruments used in the Containment of Antibiotic REsistance—measures to improve antibiotic use in pregnancy, childbirth and young children project

| Data collection instrument | Target data source/participant | Timepoint and place of data collection | Outcome variable |

| Structured interview |

|

|

Knowledge, attitudes and self-reported practices regarding antibiotic use and resistance |

| Self-reported practice form |

|

|

|

| Medical examination and prescribing form |

|

|

|

| Records review form | Pregnant women | Records review in the included health facilities, 12 months pre- and 12 months post- intervention | Antibiotic administration during delivery |

| Key stakeholders qualitative interviews | All relevant HCPs (doctors, nurses, midwifes, private providers), drug sellers and policy-makers (Ministry of Health, members of professional association, university) | At pre- and post- intervention phase, interviews at the workplace of key stakeholder | Perceptions of HCPs and policy-makers towards antibiotic administration to pregnant women, during delivery and for children under 2 |

| Focus group discussion |

|

|

Perceptions of pregnant women and mothers regarding antibiotic use and resistance during pregnancy, delivery and for children under 2 |

ANC, antenatal care; HCPs, healthcare providers.

Quantitative data collection

Repeated structured interviews on knowledge, attitude and reported practice regarding antibiotic use, ABR and antibiotic side effects will be performed with women at three timepoints, that is before the intervention (during pregnancy and 6 months after delivery) and after the intervention.

HCPs will be interviewed about their knowledge, attitudes and reported practice regarding antibiotic use for pregnant women, delivery and for children before and after the intervention. Simultaneously, data on antibiotic use during delivery will be continuously collected from patient records in all included health facilities.

The baseline interviews with expecting mothers and HCPs will be performed at ANC visit. The follow-up questionnaires with the women after delivery will be performed during the routine vaccination scheme visit or if not possible in the household. HCPs are interviewed at their workplace.

To capture additional information on self-reported use of antibiotics, several forms will be attached to the ANC booklet—a booklet that women receive at the beginning of pregnancy and where all pregnancy related information are recorded by HCP (table 1). Pregnant women will be asked to report all medicines taken regularly to improve overall health status, prevent disease or treat chronic condition (eg, folic acid, iron, herbs) or occasionally for any episode of illness (eg, antibiotic, paracetamol, herbs). Similarly, a regular and occasional use will be reported by mothers for their children. Additionally, we will collect data on the last clinical examination of pregnant woman and/or a child. The forms will be filled by an HCP at each occasion when a pregnant woman and/or child seeks for healthcare with symptoms of illness. The forms will be collected monthly from the ANC booklet by a designated person at each healthcare facility, stored in a secure place and then collected by the study team.

Qualitative data collection

FGDs will be organised to discuss women’s perceptions of antibiotic use, ABR and side effects during pregnancy, childbirth and for children. A range of stakeholders (HCPs and policy-makers) will be individually interviewed to explore their views on antibiotic use, ABR, side effects of antibiotic use during pregnancy, childbirth and for children as well as infection prevention and control measures.

Before the intervention 6 FGDs (3 groups with 29 pregnant women and 3 groups with 26 mothers with children under 2 years of age) will be organised in Thulakhom district, and approximately 30 HCPs will participate in the individual qualitative interviews (approximately 9 at central and provincial level, and 12 at district level). After the intervention the FGDs and individual interviews will be conducted with similar number of participants until data saturation is reached. The FGDs and individual interview guides themes are presented in online supplemental appendix 1.

bmjopen-2020-040334supp001.pdf (72.5KB, pdf)

Recruitment

The pregnant women will be identified via the local health registry of ANC, and invited to participate during their ANC visit. All HCPs working in the study sites will be invited to participate and will be notified about the study via local health staff name list. Women who will participate in FGDs before the intervention will be identified during postpartum visit and/or child vaccination visit and approached by local health staff. Stakeholders for individual qualitative interviews will be identified and recruited via local health staff name list.

Data collection performance

The data collection team comprises: 4 Master’s students from Lao Tropical and Public Health Institute, 4 staff members from the same Institute and 4 staff members from the University of Health Science in Vientiane who speak the local language. All data collectors will participate in a 1-week long training shortly before the initiation of data collection. The training will consist of lectures on qualitative and quantitative methodology, practical sections on using electronic platform for data collection with tablets, practical session on qualitative interviews, standard operating procedures for each question, microbiology samples collection and field management. Data collectors will conduct both quantitative and qualitative interviews and act as moderators and note takers during FGDs.

Methods and analysis: intervention

Educational intervention

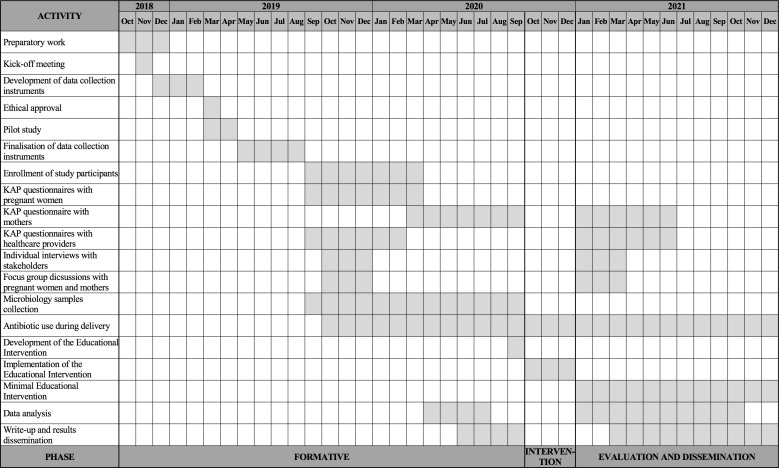

The results from the pilot study and formative phase, combined with the experience in educational interventions of the research team24 25 will feed in the development of a contextual educational intervention. The educational package aims to decrease unnecessary antibiotic use for uncomplicated vaginal deliveries and during pregnancy, increased knowledge and indirectly limit the spread of ABR. The educational intervention will be conducted in Feuang district due to feasibility reason and faster availability of baseline data, will start immediately after follow-up data collection and will last 3 months. After completion of the intervention the research team aims to sustain some of the intervention activities, for example, posters display. The project timeline is presented in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Timeline of the project. KAP, knowledge, attitude and practice.

The intervention will consist of several components tailored to HCPs and community:

(1) A participatory, iterative process-based model for improvement will be used as a conceptual framework for developing, testing and implementing changes in the proposed intervention. The Plan–Do–Study–Act cycle allows to test out changes on a small scale, building on the learning from these cycles in a structured way before the full-scale implementation.26

Results from the formative phase (started in September 2019) showed that almost all HCPs have access to a mobile phone and would accept an intervention provided via online platforms or social media. Although there are several treatment guidelines in place at the national level, there are no specific guidelines regarding intrapartum antibiotic use. Therefore, several interventional components will be targeted to HCPs: (a) Educational workshops with a key content on selection of antibiotics per indication, use of broad versus narrow spectrum antibiotics and feedback on qualitative and quantitative findings. Workshops will be delivered by a facilitator using power point, case studies, presentation of support tools (eg, alcohol-based hand rub) and role playing. These workshops will take place at several occasions during 3-month intervention period and the facilitator will use Train the Trainers approach. (b) Educational tools (leaflets, handouts) regarding antibiotic use during pregnancy, childbirth and for children, ABR, infection prevention and control will be developed and provided by the study team to each HCPs via both traditional (at healthcare facilities) and online channels. (c) Short, acceptable messages will be developed and sent regularly from a trusted source (i.e. Lao Tropical and Public Health Institute) via WhatsApp to all HCPs who participated in the workshops.

In addition, a revision of existing curricula for HCPs educational tracks and if needed initiation of recurrent training regarding intrapartum antibiotic use will take place. A collaboration with national Obstetrics and Gynaecology Association will be initiated to work on the development of local prescribing guidelines.

(2) Women are usually the main caregivers of the children and often the main decision-makers regarding healthcare seeking behaviour, and have a great impact on the use of antibiotics among pregnant women and children. Simple and inexpensive interventions using short text messages have been widely used in low-income and middle-income countries and some of them showed to be a potent tool for behavioural change.27–30 The results from the formative phase showed that initially planned mHealth intervention will not be feasible to target community members. Mobile phone ownership is as low as 30% among the rural population and the male, head of household, often is in charge of the phone. Therefore, the following intervention components will be used: (a) Educational workshops that will cover broad range of topics for example, antibiotic use during pregnancy, hygiene and self-care during pregnancy and delivery (in case of home deliveries) and after delivery, breastfeeding and other feeding practices, vaccinations, caring for a sick child, antibiotic use for children. The workshops will be organised in the villages at several occasion during the intervention period, delivered by a facilitator and supported by local health staff. We also aim to ask local Lao Women’s Union to support and endorse the activities.

(b) Several well-accepted communication channels such as posters and radio campaigns to convey the key message on prudent antibiotic use during pregnancy and for children will be used. Posters will be displayed in villages, for example, around intersections or by residents’ gathering places, such as the door of the supermarket or village clinic or pharmacy, or outer wall of a house located on the main road. Radio campaigns will be designed and delivered as a short role-playing scenarios, for example, newly delivered women and HCPs talking about need for antibiotics after delivery in decided broadcasting time.

Evaluation of the intervention

Primary outcome

The primary outcome of the study is the proportion of uncomplicated normal deliveries for which antibiotics were used. Data on antibiotic use for each delivery will be collected from patient records at included health facilities continuously for 12 months before, during and 12 months after the intervention. The impact of the intervention will be evaluated through time series analysis.

Secondary outcomes

Knowledge, attitudes and reported practices regarding antibiotic use during pregnancy and for children and ABR of pregnant women and mothers.

Knowledge, attitudes and reported practices regarding antibiotic use for pregnant women, during delivery and for children and ABR of HCPs.

Proportion of samples with ESBL or multidrug resistant producing bacteria and other relevant resistances pattern to tested antibiotics (only pre intervention phase).

Proportion of children under 2 years of age where antibiotics have been used.

Proportion of caesarean section deliveries where antibiotics are given.

Following the completion of the intervention phase, mothers and HCPs will be interviewed again using the same questionnaires as at the pre-intervention to evaluate the change in their knowledge, attitudes and practices. To evaluate if the intervention was carried out as planned and detect the strengths and weaknesses of the programme, several process indicators data will be collected. We will monitor number of participants, number of booklets, handouts and posters printed and distributed. A local research team will use a process evaluation form to monitor the intervention with local partners. After the workshops, both HCPs and community members will be given a questionnaire to collect their reflections on the provided content.

Methods and analysis: microbiology analysis and methods

Microbiology samples collection and analysis

We aim to estimate the prevalence of faecal carriage of ESBL producing and multidrug resistant E. coli and Klebsiella spp. Rectal swabs will be collected from all pregnant women before delivery, during delivery from women and their newborn children (meconium) and 6 months after delivery from mothers and their children. Should taking samples during delivery not be possible, they will be taken at home within 7 days after delivery. Rectal swabs will be collected at each health facility in Feuang district by either HCP or mother herself and transported to the district hospital in a cold box with icepack to keep temperature around 2°C–4°C. After collecting samples in the district hospital, they will be transported to the microbiology laboratory of the Mahosot hospital in Vientiane capital, maintaining the cold chain as appropriate. After arrival, samples will be stored at 4°C until processing. All samples will be processed within 14 days after sampling.

Rectal swabs will be used for culturing on Brilliance UTI Agar (bioMerieux), where E. coli will appear as red or pink colonies and Klebsiella spp. as dark blue colonies. Species identification will be performed biochemically. Those confirmed as E. coli or Klebsiella spp. will be screened for ESBL using cefpodoxime. The suspected ESBL strains will be further tested using ceftazidime with and without clavulanic acid and cefotaxime with and without clavulanic acid. In the next step, all positive ESBL-producing strains will be tested against common antibiotics using disk diffusion susceptibility test: ampicillin, amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, ceftriaxone, meropenem, gentamicin, amikacin, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, cefpodoxime, chloramphenicol, ciprofloxacin and tetracycline. Antibiotic susceptibility testing will be performed by standardised disk diffusion method (Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, 2018). In parallel, swabs will be cultured on CHROMID CARBA (bioMerieux) for detection of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. ESBL-producing/CARBA medium isolates of E. coli and Klebsiella spp. will be stored at −80°C for future analysis.

Methods and analysis: data management and analysis

Electronic data collection, data management and data quality control

All quantitative data will be collected and managed electronically using Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap)31 tool hosted at Karolinska Institutet. REDCap is a secure, web-based application designed to support data capture for research studies, providing audit trails for tracking data manipulation and export procedures. Data collection instruments will be developed in REDCap and, where appropriate, consisted predetermined checks and range validations. For in-the-field data collection purpose, instruments will be exported onto Samsung tablets (Samsung Galaxy Tab. 3.V, Seoul, South Korea) equipped with mobile internet access. Data collected via tablets will be cross-checked before synchronisation with the REDCap server. Data collected via paper forms will be cross-checked for completeness and entered directly to REDCap server by a data key entry person. Data quality checks will be run weekly by a data manager who tracks information such as form completion, internal consistency, data range and eligibility criteria. Feedback will be regularly communicated with data collectors and study team to assure consistent, high quality data collection.

Qualitative data will be audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim and checked with recorder version.

Sample size

Considering an estimated 79% for the main outcome measure of the study (proportion of uncomplicated deliveries in the hospital where antibiotics are given) 20, with a 95% CI, a sample size of 450 deliveries would allow us to have a CI with a width equal to 4%. Therefore, to allow a loss to follow-up of 25%, 600 women are included.

Data analysis

Statistical analysis will be performed using STATA V.15.1 (College Station, Texas, USA). Descriptive analyses will include frequencies for categorical variables, mean and standard deviation or median and inter-quartile range for continuous variables. Chi-square test will be used to compare two categorical variables, t-test or Mann-Whitney U test will be used to compare a numerical variable in two groups, while when comparing a numerical variable among three or more groups Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) or Kruskal-Wallis test will be used. Interrupted time series analysis will be used to compare the trend in the proportion of the primary outcome of interest the 12 months before the planned intervention and 12 months after it.32 Moreover, in order to compare knowledge and attitudes of mothers and HCPs (pre–post intervention) we will use multilevel mixed effects generalised linear models (Stata command meglm) with different family distributions according to the outcome distribution (Stata option family). Results will be presented as effect estimates with 95% CIs and will primarily be done both together and separately for each healthcare facility. Interaction test will be performed if relevant. P values less than 0.05 will be considered significant in the final analysis.

Manifest and latent qualitative content analysis will be applied for the qualitative data analysis.33

Study status

Data collection started in September 2019 is ongoing and will continue until the end of 2021 followed by data analysis and dissemination of results. Preliminary results obtained from the formative phase supported development of the intervention components and are described in the methods section.

Due to COVID-19 pandemic, CHROMID CARBA (bioMerieux) cannot be continuously delivered to Laos and that results in adjustments in the microbiological procedures. After arrival to the microbiology laboratory of the Mahosot hospital in Vientiane capital, samples are stored at −80°C until processing.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethics

The project received ethical approval from the National Ethics Committee for Health Research, Ministry of Health of Laos (031/NECHR dated 27 March 2019). All study participants will receive information about the aim of the study and their role as participants and they will be asked for a written consent. They will be informed that participation is voluntary and that they are free to withdraw from the study at any time without experiencing any repercussions.

The research team will take several measures to assure participants’ confidentiality throughout the study. During structured interviews, no information that may compromise participant’s identity will be collected. A unique participant’s ID code will be generated for each participant and will be used for data collection and analysis. The unique identifier will be stored separately and accessible only to a data manager. Moreover, all participants of the FGDs and qualitative interviews will be asked to refrain from sharing information about what was said during the FDGs and interviews. Although we are aware that this cannot be guaranteed from all participants, it will be guaranteed from the research team side. The participants will be informed that the qualitative interviews and FGDs are recorder. All data will be stored in cloud-based repositories. Data safety, sharing and protection will be agreed on during consultative meetings in line with national legislation.

Risk and benefits for the study participants have been carefully considered. During the data collection process, we will interview pregnant women and mothers of young children about their knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding antibiotic use and ABR. There is a risk that some questions may be perceived as intimidating and cause stress, since women may be afraid that investigators are questioning their knowledge and practices. For HCPs, participation in the study may cause additional workload related to answering interview questions and filling up additional forms.

However, we believe that the short-term and long-term outcomes of the study overcome the possible risks attributable to this study. All researchers involved in the study will work together to minimise potential risks and stress factors for the study participants at the same time assuring them of the benefits.

Dissemination plan

Findings from this project will be disseminated to a range of stakeholders in addition to traditional peer-reviewed international or national journal articles, conference presentations (Lao National Health Research Forum), consortium meetings, symposia and networking events. As part of the project implementation process, we will feedback results to local stakeholders, authorities, policy-makers and community members via various recognised communication channels. The local consortium partners will be responsible to assure the successful communication with relevant stakeholders. In addition, if feasible and appropriate dissemination through mass media will be done.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors were involved in conception, planning and design of the study. AM, AS, JE, VS, CH, SK and CSL were involved in development of data collection instruments. AM, AS, MV, VS and SK provided training for data collectors. AS, VS and SK recruited participants, led data collection and liaised with various stakeholders. MV, AB and MM planned for data collection and analysis of microbiological part of the study. AS and CH provided expertise in the area of obstetrics and gynaecology. GM planned for statistical analysis. JE and BK led intervention planning. AM wrote the first draft of the manuscript and made all necessary amendments after review. All co-authors (AS, JE, MV, GM, VS, CH, BK, AB, MM, SK and CSL) read the manuscript and provided critical comments and approved the final version of the manuscript. SK and CSL are principal investigators of the project.

Funding: This study is supported by funding from Southeast Asia Europe Joint Funding Scheme on Research and Innovation through Swedish Research Council, Grant number: 2018-01027. The project is also supported by Karolinska Institutet internal funds grants (2018-01993, 2020-02146).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

References

- 1.Sengupta S, Chattopadhyay MK, Grossart H-P. The multifaceted roles of antibiotics and antibiotic resistance in nature. Front Microbiol 2013;4:47. 10.3389/fmicb.2013.00047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization Global action plan on antimicrobial resistance, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O'Neill J. Antimicrobial resistance: tackling a crisis for the health and wealth of nations, the review on antimicrobial resistance, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mvd H. When the Drugs Don’t Work Antibiotic Resistance as a Global Development Problem, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization Antimicrobial resistance: global report on surveillance, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stålsby Lundborg C, Tamhankar AJ. Understanding and changing human behaviour--antibiotic mainstreaming as an approach to facilitate modification of provider and consumer behaviour. Ups J Med Sci 2014;119:125–33. 10.3109/03009734.2014.905664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization The evolving threat of antimicrobial resistance: options for action. World Health Organization, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martinez de Tejada B. Antibiotic use and misuse during pregnancy and delivery: benefits and risks. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2014;11:7993–8009. 10.3390/ijerph110807993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mylonas I. Antibiotic chemotherapy during pregnancy and lactation period: aspects for consideration. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2011;283:7–18. 10.1007/s00404-010-1646-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Santos F, Oraichi D, Bérard A. Prevalence and predictors of anti-infective use during pregnancy. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2010;19:418–27. 10.1002/pds.1915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Jonge L, Bos HJ, van Langen IM, et al. Antibiotics prescribed before, during and after pregnancy in the Netherlands: a drug utilization study. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2014;23:60–8. 10.1002/pds.3492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walker WA. The importance of appropriate initial bacterial colonization of the intestine in newborn, child, and adult health. Pediatr Res 2017;82:387–95. 10.1038/pr.2017.111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mackie RI, Sghir A, Gaskins HR. Developmental microbial ecology of the neonatal gastrointestinal tract. Am J Clin Nutr 1999;69:1035s–45. 10.1093/ajcn/69.5.1035s [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization WHO recommendatin for prevention and treatment of maternal Peripartum infections, 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sharma M, Sanneving L, Mahadik K, et al. Antibiotic prescribing in women during and after delivery in a non-teaching, tertiary care hospital in Ujjain, India: a prospective cross-sectional study. J Pharm Policy Pract 2013;6:9. 10.1186/2052-3211-6-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tenover FC, McGowan JE. Reasons for the emergence of antibiotic resistance. Am J Med Sci 1996;311:9–16. 10.1016/S0002-9629(15)41625-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stoesser N, Xayaheuang S, Vongsouvath M, et al. Colonization with Enterobacteriaceae producing ESBLs in children attending pre-school childcare facilities in the Lao people's Democratic Republic. J Antimicrob Chemother 2015;70:1893–7. 10.1093/jac/dkv021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stoesser N, Crook DW, Moore CE, et al. Characteristics of CTX-M ESBL-producing Escherichia coli isolates from the Lao people's Democratic Republic, 2004-09. J Antimicrob Chemother 2012;67:240–2. 10.1093/jac/dkr434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Olaitan AO, Thongmalayvong B, Akkhavong K, et al. Clonal transmission of a colistin-resistant Escherichia coli from a domesticated pig to a human in Laos. J Antimicrob Chemother 2015;70:3402–4. 10.1093/jac/dkv252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keohavong B, Sihavong A, Soukhaseum T, et al. Use of antibiotics among mothers after normal delivery in two provinces in Lao PDR. Third International Conference on Improving Use of Medicines; 14-18 November 2011, Antalya, Turkey, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 21.World bank The world bank data. Available: https://data.worldbank.org/country/lao-pdr

- 22.The World Bank Lao PDR civil registration and vital statistics project Lao PDR civil registration and vital statistics project. Available: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/408371561720719822/pdf/Concept-Project-Information-Document-Integrated-Safeguards-Data-Sheet-Lao-People-s-Democratic-Republic-Civil-Registration-and-Vital-Statistics-Project-P167601.pdf

- 23.Hoan LT, Chuc NTK, Ottosson E, et al. Drug use among children under 5 with respiratory illness and/or diarrhoea in a rural district of Vietnam. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2009;18:448–53. 10.1002/pds.1730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chalker J, Ratanawijitrasin S, Chuc NTK, et al. Effectiveness of a multi-component intervention on dispensing practices at private pharmacies in Vietnam and Thailand--a randomized controlled trial. Soc Sci Med 2005;60:131–41. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.04.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hoa NQ, Thi Lan P, Phuc HD, et al. Antibiotic prescribing and dispensing for acute respiratory infections in children: effectiveness of a multi-faceted intervention for health-care providers in Vietnam. Glob Health Action 2017;10:1327638. 10.1080/16549716.2017.1327638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Improvement N Plan, do, study, act (PDSA) cycles and the model for improvement. Available: https://improvement.nhs.uk/documents/2142/plan-do-study-act.pdf

- 27.Lester RT, Ritvo P, Mills EJ, et al. Effects of a mobile phone short message service on antiretroviral treatment adherence in Kenya (WelTel Kenya1): a randomised trial. Lancet 2010;376:1838–45. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61997-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sabin LL, Bachman DeSilva M, Gill CJ, et al. Improving adherence to antiretroviral therapy with triggered real-time text message reminders: the China adherence through technology study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2015;69:551–9. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Free C, Phillips G, Galli L, et al. The effectiveness of mobile-health technology-based health behaviour change or disease management interventions for health care consumers: a systematic review. PLoS Med 2013;10:e1001362. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Coleman J, Bohlin KC, Thorson A, et al. Effectiveness of an SMS-based maternal mHealth intervention to improve clinical outcomes of HIV-positive pregnant women. AIDS Care 2017;29:890–7. 10.1080/09540121.2017.1280126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.REDCap Research electronic data capture. Available: https://projectredcap.org/software/

- 32.Liu W, Ye S, Barton BA, et al. Simulation-Based power and sample size calculation for designing interrupted time series analyses of count outcomes in evaluation of health policy interventions. Contemp Clin Trials Commun 2020;17:100474. 10.1016/j.conctc.2019.100474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today 2004;24:105–12. 10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2020-040334supp001.pdf (72.5KB, pdf)