Abstract

Significant fatigue is reported by two-thirds of patients with SLE and severe fatigue by one-third. The assessment and treatment of fatigue remains a major challenge in SLE, especially in patients with no disease activity. Here, we suggest a practical algorithm for the management of fatigue in SLE. First, common but non–SLE-related causes of fatigue should be ruled out based on medical history, clinical and laboratory examinations. Then, presence of SLE-related disease activity or organ damage should be assessed. In patients with active disease, remission is the most appropriate therapeutic target while symptomatic support is needed in case of damage. Both anxiety and depression are major independent predictors of fatigue in SLE and require dedicated assessment and care with psychological counselling and pharmacological intervention if needed. This practical algorithm will help in improving the management of one the most common and complex patient complaints in SLE.

Keywords: lupus erythematosus, systemic, autoimmunity, quality of life

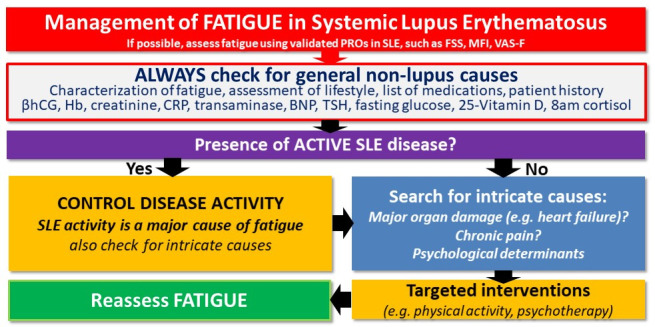

SLE is a chronic autoimmune disease which may cause a broad spectrum of clinical manifestations as well as subjective symptoms1 2 such as fatigue. In SLE, fatigue is reported by 67% to 90% of patients1 3 4 and is rated as severe in up to one-third of patients using validated fatigue instruments, as shown in the recent multicentre FATILUP study.1 Also, fatigue is often reported as the most debilitating symptom of the disease by patients5 6 and leads to both altered health-related quality of life4 7–9 and significant work disability with tremendous indirect costs.3 The rational assessment and treatment of fatigue remains a major challenge in SLE,5 especially in patients without active disease. Noteworthy, fatigue is a highly multifactorial concept10 which, in the context of SLE, may be due either to lupus-related or non–lupus-related general causes. Importantly, those causes can also be intricate with significant psychobehavioural determinants. Here, we suggest a practical step-by-step algorithm for the general assessment and management of fatigue in SLE (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Practical algorithm for the management of fatigue in patients with SLE.

Step 1: search for a general (non–lupus-related) cause of fatigue

In the primary care setting, a medical or psychiatric diagnosis can be found in at least two-thirds of patients presenting with acute fatigue. The most frequent causes of fatigue are summarised in table 1. It is crucial to understand the patient’s perspective, the detailed history of fatigue and the impact on the patient’s mood as well as on daily activities such as work, household chores, physical activity and leisure. Box 1 summarises the main questions to be asked when confronted with a patient with fatigue. A review of current medications is suggested, as some drugs may induce fatigue (eg, antihypertensive drugs such as beta blockers or sedatives). Lifestyle assessment is also essential: a significant association between smoking and fatigue has been reported in SLE.11–14 Also, obesity has been associated with increased fatigue both in the general population and SLE.15

Table 1.

Frequent causes of fatigue and suggested first-line assessment

| Common causes of fatigue | First-line assessment | |

| Drug-induced fatigue | Steroids, anti-arrhythmic, anti-hypertensive, benzodiazepines or other antidepressant and sedative agents, anti-histaminic, diuretics | Medication review |

| Pregnancy | β-HCG | |

| Anaemia | Iron or vitamin deficiencies | C-reactive protein, haemoglobin, Coombs test, ferritin, B9 and B12 vitamins |

| Metabolic disorders | Hypothyroidism, adrenal insufficiency, panhypopituitarism | TSH, fasting glucose… |

| Vitamin D insufficiency | Vitamin D levels | |

| Infection | Chronic bacterial (mycobacterial) or viral (HIV, hepatitis B and C, EBV) infections | C reactive protein Hepatitis B/C, EBV and HIV serology Quantiferon |

| Organ failure | Cardiac insufficiency Respiratory insufficiency Liver insufficiency Kidney insufficiency |

BNP, chest X-ray, echocardiography creatinine, full hepatic tests |

| Sleep disorders | Obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome Jet lag syndrome in frequent travellers |

Polysomnography |

b-HCG, b-human chorionic gonadotropin hormone; BNP, brain natriuretic peptide; EBV, Epstein-Barr virus; TSH, thyroid-stimulating hormone.

Box 1. Checklist for the initial assessment of fatigue in SLE.

-

Characterisation of fatigue:

Onset: acute or insidious

Evolution: recent (<1 month), persistent (<6 months) or chronic (>6 months)

Presence of fatigue-free periods

Is fatigue ameliorated by rest?

Physical and mental impact of fatigue

Assessment of lifestyle (work, restrictive diet or obesity, physical activity), habitus (smoking, drinking) and sleep quality

-

Presence of concurrent manifestations

Lupus flare?

Any other (non–SLE-related) disorder?

List of medications

List of previous or current associated medical conditions

A full clinical examination of the heart, lung, thyroid and nervous system16 is crucial. For women, a gynaecological examination is also recommended, especially in case of anaemia.17 18 Laboratory tests should rule out most common causes of fatigue (box 1) such as inflammation and infection, anaemia, renal or hepatic failure, viral hepatitis or HIV infection, and major endocrine or metabolic complications such as abnormal calcemia, hypothyroidism, diabetes or adrenal insufficiency (especially in patients who recently stopped glucocorticoids). Cancer screening should be updated, according to current guidelines, and indirect signs of malignancy (anorexia, weight loss and lymphadenopathy) should be carefully searched for. Although controversial,19 vitamin D deficiency has been associated with fatigue in SLE.20 In an observational study of 80 patients with SLE, vitamin D supplementation improved fatigue in participants.21 Also, vitamin D supplementation was associated with a decrease in fatigue scores in a randomised controlled trial in juvenile-onset SLE.22

Step 2: objective assessment of fatigue using validated PROs

Because fatigue is a highly subjective symptom, the standardised assessment of fatigue using validated patient-reported outcomes (PROs) is an important step. The use of validated PROs also allows for an individual follow-up of fatigue intensity and symptoms over time, and may help in underlining the benefit of a therapeutic intervention at the patient level. It is also a way to show that the physician is genuinely interested in understanding and treating the cause of fatigue, which is important from the patient’s perspective, and helps in establishing a trusting physician–patient relationship. Among a total of 16 different fatigue PROs which have been used in SLE, the FSS (Fatigue Severity Scale) and the short-FSS are the most used ones, but the MFI (Multi-dimensional Fatigue Inventory) and the Fatigue-VAS have also been used, although less commonly16 (see table 2). The FACIT-Fatigue score is commonly used in clinical trials but has been infrequently used in routine clinical practice.1

Table 2.

Most frequently used fatigue patient-reported outcomes (PROs) in SLE

| Fatigue PROs | Description |

| Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS) | 9-item scale covering the general aspects of fatigue Originally derived for people with multiple sclerosis and SLE |

| Multi-dimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI) | 20-item scale divided into five domains: general fatigue, physical fatigue, mental fatigue, reduced motivation and reduced activity The threshold for significant fatigue depends on age and gender |

| Visual analogue scale to evaluate fatigue severity (VAS-F) | The scale consists of 18 items related to the subjective experience of fatigue, using fatigue and energy subscales |

| Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy–Fatigue (FACIT-Fatigue) | 13-item self-reported questionnaire assessing aspects of physical and mental fatigue, and their effects on function and daily living |

Step 3: identifying a lupus-related cause of fatigue

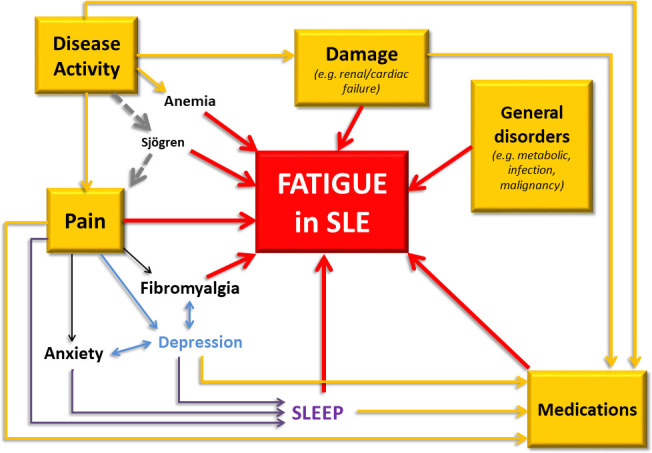

Fatigue can be a manifestation of active SLE but can also be related to organ damage (figure 2). The relationship between disease activity and fatigue remains controversial in SLE and has been shown to be less strong than with other factors such as anxiety or depression.1 23 24 Its association with serological markers (C3, anti-dsDNA antibodies) is also controversial.11

Figure 2.

Main determinants of fatigue in patients with SLE.

Fatigue has been associated with several SLE-specific organ manifestations:

Several studies found an association between neurological involvement,11 25 including white matter hyperintensities,26 and fatigue.

Renal failure can be an important cause of fatigue. It is crucial to assess whether it is related to active kidney disease or to chronic lesions (damage).27 28

Cardiac failure is an obvious cause of fatigue.

Hepatic failure and cirrhosis can (rarely) be due to lupus hepatitis, and overlap with autoimmune hepatitis or less frequently sclerosing cholangitis.29 30

Other clinical manifestations of SLE have been associated with fatigue: in the FATILUP study,1 we found arthritis and oral ulcers to be individual SLE Disease Activity Index score components associated with severe fatigue. This may underline a more specific role for painful disease manifestations in SLE.11 23

Finally, the prevalence of fibromyalgia is estimated to range between 6.2% and 22% of patients with SLE31 32 and has been strongly associated with fatigue.33 Sjögren’s syndrome should also be thought of in patients with sicca syndrome and has been associated with significant fatigue across several studies.34 35

Step 4: looking for intricate psychological determinants

Emotional and functional well-beings as well as abnormal illness-related behaviours strongly correlate with depression and fatigue in SLE.1 36 37 Pain, stress and depression have been shown to be the most important predictors of fatigue in patients with SLE38 and their intensity and consequences should be assessed, with the help of a psychologist or psychiatrist if needed. Mood disorders are reported in up to 13% of patients with SLE and attributed to SLE in about 40% of cases.39 Sleep disorders are also common in the general population as well as in SLE, and have been associated with fatigue40–42 and depression.41

Towards a practical management of fatigue in patients with SLE

In patients with significant disease activity, the main therapeutic target is remission (or alternatively low-disease activity) and reaching these goals can be sufficient to improve fatigue.43 44 However, a common situation is the presence of significant fatigue contrasting with the absence of disease activity or any underlying organic cause. In these patients, immunosuppressive treatment escalation is not indicated and other non-pharmacological interventions such as psychological and behavioural assessment or physical activity workshops should be favoured.45 Importantly, lack of optimal physical activity as well as sedentary behaviour have been associated with fatigue in SLE.44 46 47 Physical exercise is recommended for the management of pain and fatigue in patients with inflammatory arthritis in the last European League Against Rheumatism recommendations.48 Physical activity has been shown to improve fatigue in patients with SLE,44 49 with more time spent in moderate or high physical activity associated with less fatigue.50 Patients with SLE with otherwise unexplained fatigue should undergo dedicated psychological assessment, and behavioural issues should be specifically taken care of using appropriate psychological counselling51–55 and pharmacological intervention, when needed. The exact benefit of antidepressants on fatigue is difficult to assess in SLE because there is no specific trial, but there is no reason to believe that those treatments would not be appropriate, keeping in mind the potential interaction with hydroxychloroquine, which may lead to QT prolongation. Tobacco smoking cessation should be encouraged as it significantly reduces therapeutic efficacy of many drugs and could promote flares.14 Last but not least, hydroxychloroquine observance should be evaluated and if needed, non-scheduled hydroxychloroquine serum concentrations should be measured to verify therapeutic adherence and adjust daily posology.56 57

Conclusion

Significant fatigue is reported by two-thirds of patients with SLE and severe fatigue by one-third.1 As in the general population, general non–SLE-related causes of fatigue should be ruled out. Then, it is important to assess whether fatigue may be related to disease activity or damage. In the former situation, disease remission is the most appropriate therapeutic target, with an emphasis on painful manifestations. Importantly, both anxiety and depression are major independent predictors of fatigue in several studies. These manifestations should be thoroughly assessed and taken care of using appropriate psychological counselling and pharmacological intervention, when needed. We believe this practical algorithm will help in improving the management of one of the most common and complex patient complaints in SLE.

Footnotes

Twitter: @Lupusreference

Contributors: All authors have equally contributed to this work.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Arnaud L, Gavand PE, Voll R, et al. Predictors of fatigue and severe fatigue in a large international cohort of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus and a systematic review of the literature. Rheumatology 2019;58:987–96. 10.1093/rheumatology/key398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cleanthous S, Tyagi M, Isenberg DA, et al. What do we know about self-reported fatigue in systemic lupus erythematosus? Lupus 2012;21:465–76. 10.1177/0961203312436863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baker K, Pope J. Employment and work disability in systemic lupus erythematosus: a systematic review. Rheumatology 2009;48:281–4. 10.1093/rheumatology/ken477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fonseca R, Bernardes M, Terroso G, et al. Silent burdens in disease: fatigue and depression in SLE. Autoimmune Dis 2014;2014:1–9. 10.1155/2014/790724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Felten R, Sagez F, Gavand P-E, et al. 10 most important contemporary challenges in the management of SLE. Lupus Sci Med 2019;6:e000303. 10.1136/lupus-2018-000303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schneider M. Pitfalls in lupus. Autoimmun Rev 2016;15:1089–93. 10.1016/j.autrev.2016.07.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Devilliers H, Amoura Z, Besancenot J-F, et al. Responsiveness of the 36-item short form health survey and the lupus quality of life questionnaire in SLE. Rheumatology 2015;54:940–9. 10.1093/rheumatology/keu410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jolly M, Annapureddy N, Arnaud L, et al. Changes in quality of life in relation to disease activity in systemic lupus erythematosus: post-hoc analysis of the BLISS-52 trial. Lupus 2019;28:1628–39. 10.1177/0961203319886065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sutanto B, Singh-Grewal D, McNeil HP, et al. Experiences and perspectives of adults living with systemic lupus erythematosus: thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. Arthritis Care Res 2013;65:1752–65. 10.1002/acr.22032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nikolaus S, Bode C, Taal E, et al. Which dimensions of fatigue should be measured in patients with rheumatoid arthritis? A Delphi study. Musculoskeletal Care 2012;10:13–17. 10.1002/msc.222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burgos PI, Alarcón GS, McGwin G, et al. Disease activity and damage are not associated with increased levels of fatigue in systemic lupus erythematosus patients from a multiethnic cohort: LXVII. Arthritis Rheum 2009;61:1179–86. 10.1002/art.24649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yilmaz-Oner S, Ilhan B, Can M, et al. Fatigue in systemic lupus erythematosus: association with disease activity, quality of life and psychosocial factors. Z Rheumatol 2017;76:913–9. 10.1007/s00393-016-0185-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pettersson S, Boström C, Eriksson K, et al. Lifestyle habits and fatigue among people with systemic lupus erythematosus and matched population controls. Lupus 2015;24:955–65. 10.1177/0961203315572716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parisis D, Bernier C, Chasset F, et al. Impact of tobacco smoking upon disease risk, activity and therapeutic response in systemic lupus erythematosus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Autoimmun Rev 2019;18:102393. 10.1016/j.autrev.2019.102393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Patterson SL, Schmajuk G, Jafri K, et al. Obesity is independently associated with worse patient‐reported outcomes in women with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Care Res 2019;71:126–33. 10.1002/acr.23576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pettersson S, Lundberg IE, Liang MH, et al. Determination of the minimal clinically important difference for seven measures of fatigue in Swedish patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Scand J Rheumatol 2015;44:206–10. 10.3109/03009742.2014.988173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zard E, Arnaud L, Mathian A, et al. Increased risk of high grade cervical squamous intraepithelial lesions in systemic lupus erythematosus: a meta-analysis of the literature. Autoimmun Rev 2014;13:730–5. 10.1016/j.autrev.2014.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wincup C, Parnell C, Cleanthous S, et al. Red cell distribution width correlates with fatigue levels in a diverse group of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus irrespective of anaemia status. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2019;37:852–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ruiz-Irastorza G, Egurbide MV, Olivares N, et al. Vitamin D deficiency in systemic lupus erythematosus: prevalence, predictors and clinical consequences. Rheumatology 2008;47:920–3. 10.1093/rheumatology/ken121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stockton KA, Kandiah DA, Paratz JD, et al. Fatigue, muscle strength and vitamin D status in women with systemic lupus erythematosus compared with healthy controls. Lupus 2012;21:271–8. 10.1177/0961203311425530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ruiz-Irastorza G, Gordo S, Olivares N, et al. Changes in vitamin D levels in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: effects on fatigue, disease activity, and damage. Arthritis Care Res 2010;62:1160–5. 10.1002/acr.20186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lima GL, Paupitz J, Aikawa NE, et al. Vitamin D supplementation in adolescents and young adults with juvenile systemic lupus erythematosus for improvement in disease activity and fatigue scores: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Care Res 2016;68:91–8. 10.1002/acr.22621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moldovan I, Cooray D, Carr F, et al. Pain and depression predict self-reported fatigue/energy in lupus. Lupus 2013;22:684–9. 10.1177/0961203313486948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Da Costa D, Dritsa M, Bernatsky S, et al. Dimensions of fatigue in systemic lupus erythematosus: relationship to disease status and behavioral and psychosocial factors. J Rheumatol 2006;33:1282–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zonana-Nacach A, Roseman JM, McGwin G, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus in three ethnic groups. VI: Factors associated with fatigue within 5 years of criteria diagnosis. Lupus 2000;9:101–9. 10.1191/096120300678828046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harboe E, Greve OJ, Beyer M, et al. Fatigue is associated with cerebral white matter hyperintensities in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2008;79:199–201. 10.1136/jnnp.2007.120626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gregg LP, Jain N, Carmody T, et al. Fatigue in nondialysis chronic kidney disease: correlates and association with kidney outcomes. Am J Nephrol 2019;50:37–47. 10.1159/000500668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Artom M, Moss-Morris R, Caskey F, et al. Fatigue in advanced kidney disease. Kidney Int 2014;86:497–505. 10.1038/ki.2014.86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adiga A, Nugent K. Lupus hepatitis and autoimmune hepatitis (lupoid hepatitis). Am J Med Sci 2017;353:329–35. 10.1016/j.amjms.2016.10.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kadokawa Y, Omagari K, Matsuo I, et al. Primary sclerosing cholangitis associated with lupus nephritis: a rare association. Dig Dis Sci 2003;48:911–4. 10.1023/A:1023095428321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Torrente-Segarra V, Salman-Monte TC, Rúa-Figueroa Íñigo, et al. Fibromyalgia prevalence and related factors in a large registry of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2016;34:S40–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wolfe F, Petri M, Alarcón GS, et al. Fibromyalgia, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), and evaluation of SLE activity. J Rheumatol 2009;36:82–8. 10.3899/jrheum.080212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Macfarlane GJ, Kronisch C, Dean LE, et al. EULAR revised recommendations for the management of fibromyalgia. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:318–28. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gilboe IM, Kvien TK, Uhlig T, et al. Sicca symptoms and secondary Sjögren’s syndrome in systemic lupus erythematosus: comparison with rheumatoid arthritis and correlation with disease variables. Ann Rheum Dis 2001;60:1103–9. 10.1136/ard.60.12.1103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carsons SE, Vivino FB, Parke A, et al. Treatment guidelines for rheumatologic manifestations of Sjögren’s syndrome: use of biologic agents, management of fatigue, and inflammatory musculoskeletal pain. Arthritis Care Res 2017;69:517–27. 10.1002/acr.22968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Branco JC, Rodrigues AM, Gouveia N, et al. Prevalence of rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases and their impact on health-related quality of life, physical function and mental health in Portugal: results from EpiReumaPt – a national health survey. RMD Open 2016;2:e000166. 10.1136/rmdopen-2015-000166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Choi ST, Kang JI, Park I-H, et al. Subscale analysis of quality of life in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: association with depression, fatigue, disease activity and damage. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2012;30:665–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Azizoddin DR, Gandhi N, Weinberg S, et al. Fatigue in systemic lupus: the role of disease activity and its correlates. Lupus 2019;28:163–73. 10.1177/0961203318817826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hanly JG, Su L, Urowitz MB, et al. Mood disorders in systemic lupus erythematosus: results from an international inception cohort study. Arthritis Rheumatol 2015;67:1837–47. 10.1002/art.39111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Da Costa D, Bernatsky S, Dritsa M, et al. Determinants of sleep quality in women with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 2005;53:272–8. 10.1002/art.21069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Iaboni A, Ibanez D, Gladman DD, et al. Fatigue in systemic lupus erythematosus: contributions of disordered sleep, sleepiness, and depression. J Rheumatol 2006;33:2453–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McKinley PS, Ouellette SC, Winkel GH. The contributions of disease activity, sleep patterns, and depression to fatigue in systemic lupus erythematosus. A proposed model. Arthritis Rheum 1995;38:826–34. 10.1002/art.1780380617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van Vollenhoven R, Voskuyl A, Bertsias G, et al. A framework for remission in SLE: consensus findings from a large international task force on definitions of remission in SLE (DORIS). Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:554–61. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tench CM, McCarthy J, McCurdie I, et al. Fatigue in systemic lupus erythematosus: a randomized controlled trial of exercise. Rheumatology 2003;42:1050–4. 10.1093/rheumatology/keg289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Arnaud L, Mertz P, Amoura Z, et al. Patterns of fatigue and association with disease activity and clinical manifestations in systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatology 2020. 10.1093/rheumatology/keaa671. [Epub ahead of print: 11 Nov 2020]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Keyser RE, Rus V, Cade WT, et al. Evidence for aerobic insufficiency in women with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 2003;49:16–22. 10.1002/art.10926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Margiotta DPE, Basta F, Dolcini G, et al. Physical activity and sedentary behavior in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. PLoS One 2018;13:e0193728. 10.1371/journal.pone.0193728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Geenen R, Overman CL, Christensen R, et al. EULAR recommendations for the health professional’s approach to pain management in inflammatory arthritis and osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2018;77:797–807. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-212662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Balsamo S, Santos-Neto LD. Fatigue in systemic lupus erythematosus: an association with reduced physical fitness. Autoimmun Rev 2011;10:514–8. 10.1016/j.autrev.2011.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mahieu MA, Ahn GE, Chmiel JS, et al. Fatigue, patient reported outcomes, and objective measurement of physical activity in systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus 2016;25:1190–9. 10.1177/0961203316631632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yuen HK, Cunningham MA. Optimal management of fatigue in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: a systematic review. Ther Clin Risk Manag 2014;10:775–86. 10.2147/TCRM.S56063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fangtham M, Kasturi S, Bannuru RR, et al. Non-pharmacologic therapies for systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus 2019;28:703–12. 10.1177/0961203319841435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bisung E, Elliott SJ, Clarke AE. Non-pharmacological interventions for enhancing the working life of patients with lupus: a systematic review. Lupus 2018;27:1755–6. 10.1177/0961203318777119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Conceição CTM, Meinão IM, Bombana JA, et al. Psychoanalytic psychotherapy improves quality of life, depression, anxiety and coping in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: a controlled randomized clinical trial. Adv Rheumatol 2019;59:4. 10.1186/s42358-019-0047-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Neill J, Belan I, Ried K. Effectiveness of non-pharmacological interventions for fatigue in adults with multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, or systemic lupus erythematosus: a systematic review. J Adv Nurs 2006;56:617–35. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.04054.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Arnaud L, Zahr N, Costedoat-Chalumeau N, et al. The importance of assessing medication exposure to the definition of refractory disease in systemic lupus erythematosus. Autoimmun Rev 2011;10:674–8. 10.1016/j.autrev.2011.04.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Costedoat-Chalumeau N, Amoura Z, Hulot J-S, et al. Very low blood hydroxychloroquine concentration as an objective marker of poor adherence to treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis 2007;66:821–4. 10.1136/ard.2006.067835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]