Abstract

IMPORTANCE

Traditional in-person fellowship interviews require great time and financial commitments. Here, we studied the response of program directors (PDs) and applicants to virtual interviews. Virtual interviews could decrease both financial and time commitments.

OBJECTIVE

To determine if most applicants and PDs believed that virtual interviews should be used more widely in the future.

DESIGN

After the 2020 cardiothoracic fellowship match, an e-mail survey was sent to 66 program directors and 107 applicants using the Qualtrics platform.

SETTING

During the 2020 cardiothoracic fellowship interview cycle, the COVID-19 pandemic shut down travel for in-person interviews. This forced a transition to virtual interviews.

PARTICIPANTS

Of 107 applicants emailed, 46 (44%) participated with a completion rate of 87%. sixty-six PDs were contacted and of those, 36 (55%) participated with a 92% survey completion rate.

EXPOSURE

All survey participants were participants in the 2020 cardiothoracic match.

MAIN OUTCOME(S) AND MEASURE(S)

(1) The percent of participants who agree that virtual interviews should be continued in the future and the percent of participants who agree that virtual interviews could be replacements for in person interviews. (2) Were virtual interviews perceived to have a negative impact on one's ultimate match? (3) What is the current cost of an in-person interview in travel and lodging for an applicant?

RESULTS

Fourty-six applicants (44% participation rate) and 36 PDs (55% participation rate) participated in the survey. Seventy-nine percent of program directors and 55% of applicants either agreed or strongly agreed that virtual interviews should be offered in the future. However, just 15% of PDs and 20% of applicants either agreed or strongly agreed that virtual interviews should be offered without the option of an in-person interview. Twenty-five percent of PDs and applicants agreed or strongly agreed that virtual interviews negatively impacted their chance of matching one of their top applicants/programs. The median cost of an in-person interview was $600 (interquatile range 500-725).

CONCLUSIONS AND RELEVANCE

Most applicants and PDs agree that virtual interviews should be offered in the future. Twenty-five percent of participants reported that they believed virtual interviews negatively impacted their match. Given the overall acceptance of virtual interviews and the cost of in-person interviews, virtual interviews could be useful to incorporate into future interview seasons.

Key Words: virtual interviews, in-person interviews, COVID-19, residency, fellowship, applicants

Key Points.

Question: Do virtual interviews have a place in the traditional fellowship interview cycle, or were they just a bailout in the setting of the COVID-19 Pandemic?

Finding: Seventy-nine percent of program directors and 55% of applicants either agreed or strongly agreed that virtual interviews should be offered in the future. However, just 15% of PDs and 20% of applicants either agreed or strongly agreed that virtual interviews should be offered without the option of an in-person interview.

Meaning: Virtual interviews can play a useful role in fellowship interviews and help decrease the resources and time used for fellowship interviews.

Alt-text: Unlabelled box

Introduction

Fellowship1 match is the culmination of dedication and hard work throughout medical school and general surgery residency. However, interviews are time-intensive for residents, with an average of 7 clinical days lost to interviews, with up to 21 to 23 days for specialties such as pediatric surgery.1 , 2 Due to ACGME case minimum and annual clinical time requirements, residents may be forced to use vacation time to attend interviews or simply artificially truncate the number of programs they visit. The process is also costly, with almost a third of general surgery residents borrowing money to pay for the expenses related to the fellowship match process.3

Nevertheless, there is considerable value to applicants in attending interviews; in pediatric surgery, for example, candidates move an average of 5 positions on the rank list as a result of an in-person interview.4 Additionally, applicants have opportunities to see the area that they will likely live and work. It is unclear how advantages seen with in-person interviews translate to virtual or web-based interviews.5, 6, 7 For the urology match, a single site cross-over study demonstrated that applicants perceived a virtual interview to be less effective than a traditional on-site interview.5 In pediatric surgery, virtual interviews were reported to be an inadequate substitute for an on-site interview over 80% of the time.2 Conversely, for orthopedic reconstructive fellowship, a program offered in-person or video-conference interviews over 3 years with 85% reporting that the video-conference interviews gave them a satisfactory understanding of the fellowship.6 Likewise, in family medicine, virtual interviews were thought to be an effective screening tool for both applicants and programs alike.7

The COVID-19 pandemic shut down the United States in the middle of the cardiothoracic fellowship interview season which began when applications opened on December 1, 2019 and ended with rank list certification on April 29, 2020. This timing forced a transition to virtual interviews (utilizing a web-based videoconferencing platform) for the latter half of this time period, creating an ideal scenario in which to study the strengths and limitations of virtual as compared to in-person interviews from the perspective of both applicants and fellowship programs. With this study we sought to synthesize these opinions in order to provide guidance in transforming the way interviews might be completed in future years when travel presumably resumes.

Methods

This study was approved by the BIDMC IRB as exempt. Program directors of participating 2020 CT fellowship programs were identified using the publicly available ACGME list.8 Applicants were identified from e-mail list serves used throughout the interview process. In total, 67 program directors (PDs) for 67 programs were identified and 109 applicants were identified. One program director and two applicants were excluded from these lists due to being authors on this manuscript. The remaining individuals, 66 PDs and 107 applicants, were invited to participate in a survey using Qualtrics after the release of the match results.9 The initial survey was distributed via e-mail on May 13th with follow-up reminders on May 15th and May 17th. Surveys are available as supplemental documents in the appendix.

Questions were broken down into categories with both surveys determining what percent of interviews were in-person and virtual and how many interviews were completed. Using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5), applicants and program directors were asked to report their interest in and acceptance of virtual interviews, their perception of the effect virtual interviews had on their ability to match at one of their top choices, and their assessment of how well they could establish rapport with the interviewer/interviewee virtually versus in-person. Other questions identified whether the top ranks were from virtual or in-person interviews and whether virtual interviews allowed interviewing at more programs/of more applicants. Ultimately, study participants were asked if they matched from a virtual or in-person interview. For applicants, additional questions were asked about preferred style of virtual interviews, availability and usefulness of a virtual tours, program overviews and time to meet current fellows. An open text question with suggestions to improve virtual interviews was offered at the end of the survey.

Analysis was carried out using STATA 15.1.10 Likert scales were converted to numerical scores (1-5) and graphically displayed in Excel.11 Descriptive statistics were utilized including mean, median and interquartile range for continuous variables. Frequencies and percentages were used to summarize categorical variables. All p values were 2-sided. t-Test was used to compare means of in-person interviews and virtual interviews.

Results

Of 107 applicants emailed, 46 (44%) participated with a completion rate of 87%. 66 program directors were contacted and of those, 36 (55%) participated with a 92% survey completion rate. Demographics of applicants who volunteered their information are presented in Table 1 . Applicants completed 63.8 % of their interviews in-person and programs directors completed 69.5% in-person. There were only 2 applicants who completed all of their interviews in-person; compared to 13 programs who finished all of their interviews in-person. Applicants reported completing a mean of 15.3 interviews, and programs interviewed a mean of 22.3 applicants per ACGME fellowship position. Twelve applicants did not report if they matched. Of applicants and programs who used virtual interviews, only 5% of programs reported adding interviews, while 47% of applicants reported completing additional interviews to the number they had originally planned to attend due to the wide usage of virtual interviews (average of 2.5 additional interviews). Median cost of travel and lodging for one in-person interview was reported as $600 (interquartile range 500-725) for applicants.

Table 1.

Demographics of Applicants Who Completed the Survey

| Gender | |

| Male | 28 (72%) |

| Female | 11 (28%) |

| Race and ethnicity | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 27 (69%) |

| Black or African American | 1 (3%) |

| Asian | 6 (15%) |

| Hispanic or Latino | 3 (8%) |

| Other/ Prefer not to answer | 2 (5%) |

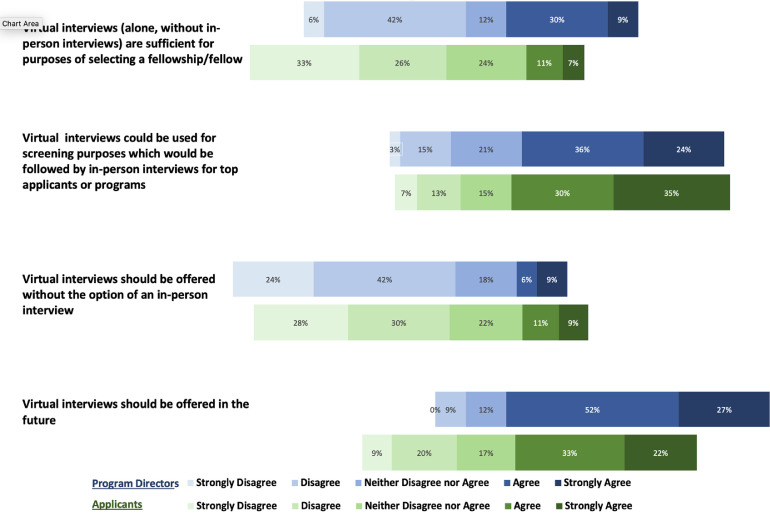

Seventy-nine percent of program directors and 55% of applicants either agreed or strongly agreed that virtual interviews should be offered in the future. However, just 15% of PDs and 20% of applicants either agreed or strongly agreed that virtual interviews should be offered without the option of an in-person interview. Thirty-nine percent of PDs agreed or strongly agreed that virtual interviews without in-person interviews are sufficient to select a fellow while only 18% of applicants felt the same way about selecting a fellowship. Details in Figure 1 .

FIGURE 1.

General acceptance of virtual interviews. Green represents applicants. Blue represents Program Directors.

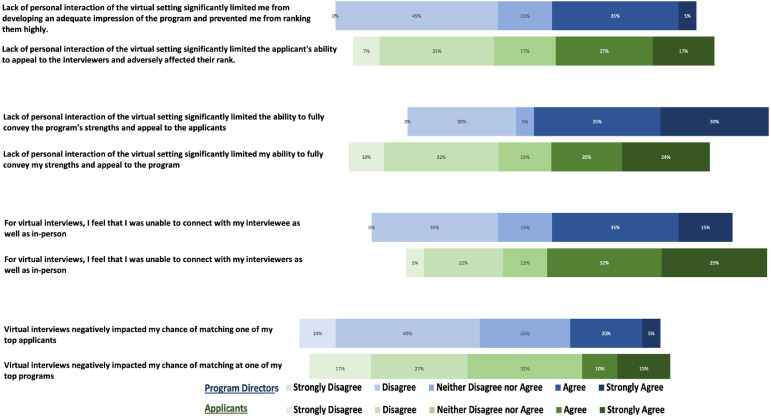

For applicants and programs who completed at least one virtual interview, questions regarding the impact of virtual interviews were completed. While only 25% of programs agreed or strongly agreed that virtual interviews negatively impacted their chance of matching one of their top applicants, 65% agreed or strongly agreed that the lack of personal interaction of the virtual setting significantly limited the ability to fully convey the program's strengths and appeal to the applicants. Twenty-five percent of applicants also either agreed or strongly agreed that virtual interviews negatively impacted their chance of matching at one of their top programs, and 44% either agreed or strongly agreed that the lack of personal interaction of the virtual setting significantly limited their ability to fully convey their strengths and appeal to the program. Interestingly, 50% of PDs agreed or strongly agreed that they were unable to connect with their interviewees as well virtually as in-person. Similarly, 61% of applicants agreed or strongly agreed that they were unable to connect with their interviewers as well as in-person (Figure 2 ).

FIGURE 2.

Perception of virtual interviews. Green represents applicants. Blue represents Program Directors.

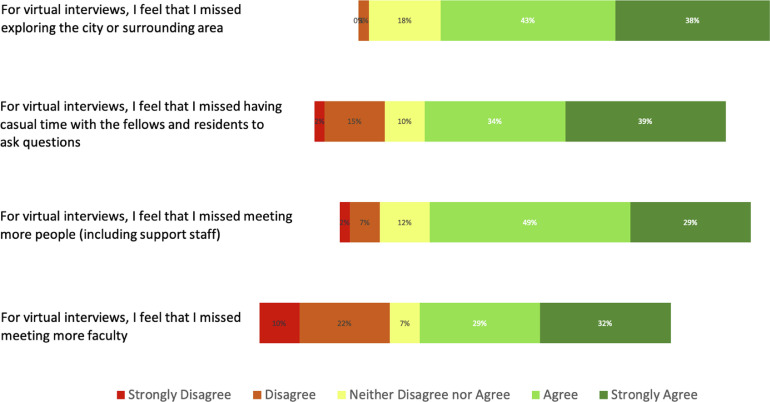

Most applicants agreed or strongly agreed that for virtual interviews they missed exploring the surrounding city, having casual time with fellows and residents, meeting more people and faculty (Figure 3 ). Eighty-five percent of applicants agreed or strongly agreed that talking to the fellows was an important component to their overall program impression during virtual interviews. Eighty-five percent of programs had a scheduled time to meet with current fellows and residents and 26% of programs offered virtual tours. Interestingly, 61% of applicants who did not experience a virtual tour agreed or strongly agreed that they missed having a hospital tour. For those applicants who experienced a virtual tour, only 20% agreed or strongly agreed that virtual tours were helpful.

FIGURE 3.

Components of virtual interviews that applicants missed.

As for the structure of virtual interviews, the majority of applicants (73%) preferred a single interviewer at a time and 53% of program directors reported structuring virtual interviews in that manner. The majority of interviewees (87.5%) preferred 4 or more virtual interview sessions and 53% of programs used 4 or more interviews.

Overall, of applicants that reported their match status and interviewed both in-person and virtually, 56% reported matching at a fellowship program that they interviewed at in-person. Ten applicants who interviewed both in-person and virtually did not report their match status. For those who matched at a program that they interviewed at in-person compared to those who matched at a program where they interviewed at virtually, there was no statistical difference between the percent of interviews completed in-person (62.8% vs 60.7%, p = 0.641). Of programs who interviewed applicants both in-person and virtually, 13 programs, representing 18 fellowship positions, reported if their matches were from virtual or in-person interviews, 55% of fellowship positions were filled by an applicant from an in-person interview. For these same fellowship positions, 62.9% of the interviews occurred in-person. Programs that matched in-person applicants did complete a statistically significantly greater percent of interviews in person (72.0% vs 51.8%, p = 0.026).

There were 37 applicants who interviewed both in-person and virtually and reported whether their first and second rank preferences resulted from an in-person interview, virtual interview (without previous in-person exposure) or virtual interview (with previous in-person exposure). On average, 38% of these applicants’ interviews were completed virtually, and their first and second ranked program preferences were solely from virtual interviews (without previously spending time at the program) 30% and 22% of the time, respectively.

With respect to the fellowship programs, there were 17 ACGME fellowship positions for which a program utilized both in-person and virtual interviews and the program directors revealed whether their first and second choice applicants were chosen after an in-person interview, virtual interview (without previously meeting the applicant) or virtual interview (previously knew/worked with the applicant). On average, 36% of these program interviews were virtual, and their first and second choice applicants were chosen from virtual interviews (without previously meeting the applicant) 35% and 41% of the time, respectively.

Discussion/Conclusion

This study evaluated the perceptions regarding virtual fellowship interviews amidst a pandemic in which programs and applicants were forced to make sudden adjustments to the traditional ACGME surgical fellowship match process. We believe that the lessons learned from this experience would be valuable in providing guidance to the planning process for virtual interviews that will be conducted in the near future as the COVID-19 pandemic necessitates. We also think these results will help shape the protocols for fellowship interviews even after social distancing and travel restrictions resolve in a postpandemic phase. While the majority of applicants and PDs felt that virtual interviews should be continued in the future, most did not think that virtual interviews should be a complete replacement for in-person interviews.

Other important observations were gleaned from this study. Most applicants and PDs did not feel that virtual interviews negatively impacted their chance of matching at the top of their rank list. Likewise, given the percent of virtual interviews completed, a similar percent of both applicants and program directors made their top-ranked choices from interviews that were conducted virtually. We feel that in the long run this may help counterbalance the perceived disadvantages of virtual interviews that are held by many applicants and programs. In addition, from the applicants’ standpoint, a significant financial advantage could be realized by moving towards a preponderance of virtual interviews. For example, given a median cost of $600 per in-person interview and an average of 15.3 interviews, applicants would spend $9,180 if all interviews were completed in person. This is almost 15% of the average salary of a PGY-4 resident in general surgery.12

Applicants provided specific information on several areas in which they thought virtual interviews were lacking or were the “missed” components of traditional interviews which could provide program directors opportunities to improve the structure and quality of future virtual interviews. For example, a virtual interview day could be constructed to include open interaction or private sessions with current trainees in the program. Likewise, applicants preferred more robust virtual interview days consisting of 4 or more interview sessions and this could easily be incorporated in a virtual interview schedule. This is an important theme that also emerged from comments as applicants responded that virtual interviews should be as thorough and have as much exposure to faculty as they would during a classic in-person interview.

There are several limitations to this current study including that the interviews were not randomized, but rather sequential to the progression of the COVID-19 pandemic, as earlier interviews were in-person followed by virtual interviews towards the end of the interview season. The universal appreciation of needing adaptability to this cataclysmic event likely influenced impressions about the virtual interviews that took place. Also, despite a robust response rate of 44 and 54% with high completion rates for an e-mail survey we did not capture entirety of participants in the interview cycle. This certainly leaves open the possibility of response bias. For example, while we know that 12 candidates in this study did not report their match status, it is unclear whether these were part of the 40 candidates who remained unmatched in the 2020 cycle though there could be a reasonable assumption that is the case. If there was a disproportionate response rate from matched candidates, the data presented here may not fully represent the experience of virtual interviewing for all candidates. While we had a complete list of program directors, we were unable to obtain a complete list of the applicants secondary to the policies prohibiting applicants’ e-mails being released from the AAMC. Therefore, e-mail list serves in circulation throughout the interview cycle were utilized and successfully identified 109 applicants. The program director and two applicants working on this project were also excluded from the pool of potential participants. As with all surveys, there is the potential of recall bias. By sending the survey immediately after the match, we attempted to eliminate, or at least decrease the recall bias.

Over the last several years, the cardiothoracic match has become more competitive with many applicants failing to match into a cardiothoracic surgery fellowship. On average, applicants interviewed at 15.3 programs while programs interviewed 22.3 applicants per ACGME position. This further demonstrates the competitiveness of cardiothoracic fellowship and potentially demonstrates that programs should interview fewer applicants. In pediatric surgery, Gadepalli et al. reported that programs interviewed excessive numbers of applicants, yet never matched below their 12th rank.13 As a surgical specialty becomes more competitive, virtual interviews may be an effective way to alleviate the heavy costs of clinical time and money for the applicants while also allotting more flexibility of time and organization for the programs. The fact that 47% of applicants accepted additional interviews once they were offered virtually might speak to the convenience factor for applicants, and possibly also their concerns that the virtual format may not afford them the same chance at matching highly once this became mandatory due to the pandemic. Even if not a complete replacement, most participants did feel that virtual interviews could be used as a screening method for in-person interviews. Others have advocated that there be a unified location for interviews, such as the Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) meeting, which is typically held during the interview season. While the process of conversion to virtual interviews affected multiple specialties in 2020, it is not clear how transferable the findings of this study are to more or less competitive matches, or matches that involve applicants at earlier stages of training, e.g. final year of medical school, than those represented in our survey data.

While we look forward to the time when the COVID-19 pandemic has passed, this forced adoption of new interview protocols does suggest some concrete best practices for future interview seasons. Reform of the interview process to allow equitable access for applicants and optimized evaluation by programs is an ongoing goal. The lessons learned from ad hoc adaptation in this extraordinary time should help with improvement of the interview process going forward.

Acknowledgments

The authors include one program director and two applicants. They were excluded from participation in the study.

Footnotes

Fellowship here is being used to describe specialty training after residency as defined by the National Resident Matching Program (NRMP).14

References

- 1.Little DC, Yoder SM, Grikscheit TC. Cost considerations and applicant characteristics for the Pediatric Surgery Match. J Pediatr Surg. 2005;40:69–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2004.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chandler NM, Litz CN, Chang HL, Danielson PD. Efficacy of videoconference interviews in the pediatric surgery match. J Surg Educ. 2019;76:420–426. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2018.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Watson SL, Hollis RH, Oladeji L, Xu S, Porterfield JR, Ponce BA. The burden of the fellowship interview process on general surgery residents and programs. J Surg Educ. 2017;74:167–172. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2016.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Downard CD, Goldin A, Garrison MM, Waldhausen J, Langham M, Hirschl R. Utility of onsite interviews in the pediatric surgery match. J Pediatr Surg. 2015;50:1042–1045. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2015.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shah SK, Arora S, Skipper B, Kalishman S, Timm TC, Smith AY. Randomized evaluation of a web based interview process for urology resident selection. J Urol. 2012;187:1380–1384. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.11.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Healy WL, Bedair H. Videoconference interviews for an adult reconstruction fellowship: lessons learned. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2017;99:e114. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.17.00322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Edje L, Miller C, Kiefer J, Oram D. Using skype as an alternative for residency selection interviews. J Grad Med Educ. 2013;5:503–505. doi: 10.4300/jgme-d-12-00152.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME). List of programs by specialty. https://apps.acgme.org/ads/Public/Reports/Report/1. Published 2020. Accessed January 5, 2020.

- 9.Qualtrics. Qualtrics. 2019. https://www.qualtrics.com.

- 10.StataCorp. Stata statistical software: release 15. 2017. https://www.stata.com.

- 11.Microsoft Corporation. Microsoft Excel. 2020. https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/microsoft-365/excel/?rtc=1.

- 12.Martin K. Medscape residents salary & debt report 2019; 2019. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2019-residents-salary-debt-report-6011735#4.

- 13.Gadepalli SK, Downard CD, Thatch KA. The effort and outcomes of the pediatric surgery match process: are we interviewing too many? J Pediatr Surg. 2015;50:1954–1957. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2015.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Residency Matching Program. Intro to fellowship matches. https://www.nrmp.org/intro-fellowship-matches/. Published 2020. Accessed June 1, 2020.